Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 outbreak severely affected long-term care (LTC) service provision. This study aimed to quantitatively evaluate its impact on the utilization of LTC services by older home-dwelling adults and identify its associated factors.

Design

A retrospective repeated cross-sectional study.

Setting and Participants

Data from a nationwide LTC Insurance Comprehensive Database comprising monthly claims from January 2019 to September 2020.

Methods

Interrupted time series analyses and segmented negative binomial regression were employed to examine changes in use for each of the 15 LTC services. Results of the analyses were synthesized using random effects meta-analysis in 3 service types (home visit, commuting, and short-stay services).

Results

LTC service use declined in April 2020 when the state of emergency (SOE) was declared, followed by a gradual recovery in June after the SOE was lifted. There was a significant association between decline in LTC service use and SOE, whereas the association between LTC service use and the status of the infection spread was limited. Service type was associated with changes in service utilization, with a more precipitous decline in commuting and short-stay services than in home visiting services during the SOE. Service use by those with dementia was higher than that by those without dementia, particularly in commuting and short-stay services, partially canceling out the decline in service use that occurred during the SOE.

Conclusions and Implications

There was a significant decline in LTC service utilization during the SOE. The decline varied depending on service types and the dementia severity of service users. These findings would help LTC professionals identify vulnerable groups and guide future plans geared toward effective infection prevention while alleviating unfavorable impacts by infection prevention measures. Future studies are required to examine the effects of the LTC service decline on older adults.

Keywords: COVID-19, long-term care service, dementia

Although all people have been greatly affected by the acute coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, older adults are among the groups most severely affected. Increasing age, along with comorbidities including dementia, have been reported as risk factors for higher mortality from COVID-19.1, 2, 3 Furthermore, this population is vulnerable to negative impacts of social restrictions related to infection prevention.4 The negative impacts include disruption to the daily routine, decrease in physical activity,5 , 6 increased social isolation,7 decreased well-being,5 and worsening neuropsychiatric symptoms, including increased anxiety and depression among those with dementia.4 , 8, 9, 10 A further concern is that social isolation and reduced social participation during the pandemic may accelerate cognitive deterioration.11 , 12

Most older adults with cognitive decline and dementia live at home and rely on long-term care (LTC) services to support their daily lives.13 During the COVID-19 outbreak, the provision of LTC services has been severely affected. Some care service providers were forced to temporarily close or reduce their provision of services.14 Furthermore, some service users chose to discontinue services because of fear of infection.15, 16, 17 The interruption of services may negatively affect the physical and mental conditions of older adults.14

In addition, there has been a concern that older adults, particularly those with dementia, may have limited access to care because of social isolation, their difficulty implementing infection prevention measures, and presumed unfavorable prognosis.18, 19, 20

However, to our knowledge, there have been few quantitative studies on the influence on LTC services under the circumstances of COVID-19.

In the current study, we aimed to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on the utilization of LTC services by older adults living at home and investigate whether the impact was associated with factors such as service types and cognitive decline during COVID-19.

Methods

Data Source

This study is a retrospective analysis of data from the Japanese LTC Insurance Comprehensive Database. The database comprises monthly records of nationwide LTC insurance claims data and certification data of long-term care under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) of Japan. This study was planned by the corresponding author and conducted as one of the projects in the Division of the Health for the Elderly of the MHLW, Japan. The preprocessed and anonymized certification data of long-term care and long-term care insurance claim data, stored in the LTC Insurance Comprehensive Database from January 2019 to September 2020, was provided by the MHLW to the authors and used for analysis.

LTC Insurance System

LTC insurance is compulsory for all adults aged 40 years or older. People aged 65 years or older, and those aged 40-64 years with disability due to specified diseases are eligible for its benefits. The LTC users are assessed for the presence of physical disability (classified by 9 levels of daily function impairment: Independent, J1, J2, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2) (Supplementary Table 1) and cognitive decline (classified by 8 levels: Independent, I, IIa, IIb, IIIa, IIIb, IV, and M) (Supplementary Table 2), and a certification of care level is determined (divided into 7 categories, “Support required 1-2” and “Care levels 1-5,” in the order of dependence for daily needs) (Supplementary Table 3). For simplicity, we reclassified the 8 levels of cognitive decline into 4 dementia categories (Independent and I into “Normal,” IIa and IIb into “Mild dementia,” IIIa and IIIb into “Moderate dementia,” and IV or M into “Severe dementia”).21

LTC services for older adults who are not institutionalized or hospitalized (ie, living at their home) can be roughly categorized into 3 service types according to the place of service provided, as follows: “home visit” services, which provide home care, nursing, or rehabilitation in the home of the recipient; “commuting” services, wherein recipients commute from their home to service centers to receive day services for care (“day care”) or rehabilitation (“day service”); “short-stay” services, in which services are offered in some LTC facilities for short-term or respite care. Recipients stay there for several days away from their home. The services analyzed in this study are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Name of Services Analyzed and the Corresponding Service Types

| Type | Name of Services |

|---|---|

| Home visit | Home visit long-term care |

| Home visit bathing service | |

| Home visit nursing care | |

| Home visit rehabilitation | |

| Management guidance for in-home care | |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care∗ | |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care∗ | |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care∗ | |

| Commuting | Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | |

| Short-stay | Short-term admission for daily life long-term care |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care∗ |

Services whose names include “for preventive long-term care” are provided to prevent deterioration of health and support the independence of older adults and are collectively called “prevention services.”

COVID Outbreak in Japan

The first case of COVID-19 in Japan was diagnosed on January 15, 2020. In late March, the number of infected cases increased rapidly, and on April 7, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency in 7 prefectures and expanded the scope to the entire nation on April 16. In the prefectures under the state of emergency, several infection prevention measures were implemented, including a request for refraining from leaving home and holding events and gatherings (mild lockdown), restrictions on the use of facilities, a request for reduction in commuting to work, and the introduction of teleworking.22 The number of infected cases declined thereafter, and the state of emergency was gradually lifted in late May 2020. A similar pattern (the second wave) was observed in July and August and no state of emergency was declared (Supplementary Table 4).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted to answer the following 3 interrelated research questions:

-

1.

How did the utilization of LTC services for older adults living at home change after the start of the COVID-19 outbreak?

-

2.

Were changes in the utilization of LTC services affected by factors such as service types and declaration of a state of emergency?

-

3.

What specific changes were observed in LTC services provided to older adults with dementia living at home?

Total monthly times services availed was used to quantify utilization of LTC services. For services with too few users during the period of interest (≤10,000 unique users in total from January 2019 to September 2020), comprehensive payment services, and facility services were excluded from the analysis. All adults who used any of these LTC services from January 2019 to September 2020 were included in the analysis.

Interrupted time series analysis was conducted to assess the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the utilization of LTC services.23 The analysis was conducted separately for each LTC service shown in Table 1. Preliminary analyses based on Poisson distribution showed the presence of overdispersion, and we adopted a segmented negative binomial regression with indicator variables for long-term time trend (January 2019–September 2020) and change in trend under COVID-19 influence (April 2020–September 2020).

For state of emergency, we assumed a temporary-level change and included indicator variables for the state of emergency (coded 1 for April to May 2020) and post state of emergency (coded 1 for June to September 2020) in the models. We hypothesized that the temporary-level change associated with the state of emergency may vary depending on the underlying dementia category and included the interaction terms between indicator variables and dementia category.

LTC service utilization is heterogeneous across prefectures, and we employed a mixed effects model with random intercepts and slope over time for the prefecture. The commitment to dementia varies considerably across prefectures, and dementia category was assigned a random effect at the prefecture level. Changes in the level at the start and end of the state of emergency were considered heterogeneous across prefectures because of differences in infection prevention policies and demographic factors and were allowed to vary across prefectures as random effects. Harmonic terms were introduced to adjust for seasonal variation of LTC service utilization.24

The negative binomial model equation estimating monthly utilization at the prefecture level is expressed as follows:

In the equation, Y t,p denotes the total monthly times services used in prefecture p at time t. T t represents months elapsed since January 2019, the start of the study. T j represents months elapsed since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, April 2020. SOE and postSOE are indicator variables for the state of emergency and post state of emergency, respectively. Cases t,p denotes the number of incident COVID-19 infection cases in prefecture p at time t.

β0p represents the model intercept and β1p represents the underlying long term trends, both of which are modeled with a fixed effect and prefecture-level random effects. β2 represents the change in the trend under COVID-19 influence. β3p and β4p represent changes in level at the start and end of the state of emergency, respectively, both of which are modeled with a fixed effect and prefecture-level random effects.

We employed fixed-effects models to analyze the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on LTC service utilization. The differences between the mean fitted values under the full model and the expected (counterfactual) values if the COVID-19 outbreak did not occur were considered loss of LTC services utilization. We used bootstrapping to derive 95% prediction intervals around these differences. Randomized quartile residuals were examined to detect model misspecification such as outliers, autocorrelation, overdispersion, and heteroscedasticity.25 , 26

The coefficients separately obtained from the analysis of each LTC service were synthesized using a random effects meta-analysis model in each service type (“home visit,” “commuting,” “short-stay”), and were converted to the incidence rate ratio.

We additionally conducted a sensitivity analysis with change in the number of service users as an outcome, which may be able to capture the influence of the COVID-19 outbreak on older adults with relatively low service utilization.

P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted by using R, version 4.1.2, and its packages.

Results

Characteristics of Service Users

In the period between January 2019 and September 2020, there were 5,040,158 unique service users. They were predominantly women (64.3%), and their median age was 85.8 years with an interquartile range of 79.7-90.5 years (Supplementary Table 5). There were no missing values in LTC service use and demographic variables.

Change in the Use of Each LTC Service During the COVID-19 Outbreak

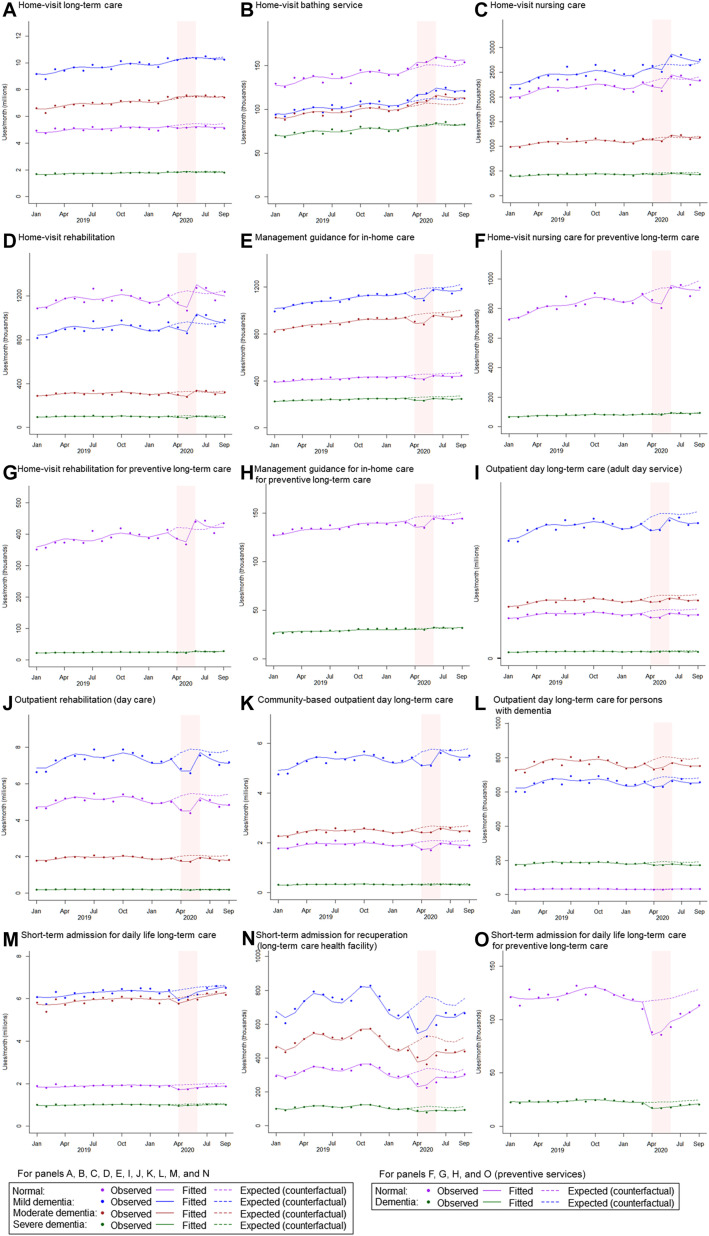

Serial nationwide changes in the use of LTC services by service over 18 months are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 6. We observed that the use of many services declined significantly in April 2020 when the nationwide state of emergency was declared. Gradual recovery of many services was observed in June right after the state of emergency was lifted. The recovery of some services, mainly commuting and short-stay services, was not sufficient to offset the reduction during the state of emergency, even in September.

Fig. 1.

Monthly uses of long-term care service from January 2019 to December 2020. In each panel, monthly uses of long-term care service (total sum of service use by all service users) are shown. The dots show observed total monthly times of service used, the solid line indicates the model-fitted monthly times of service use, and the dashed line represents the model-based expected (or counterfactual level if the COVID-19 had not occurred) times of service use. Pink rectangular shades indicate the period during which the Japanese government declared the state of emergency (from April 7 to May 25, 2020).

Heterogeneity in Changes Across Service Types and Dementia Severity

Figure 2 describes the monthly uses of each LTC service stratified by dementia severity, and Figure 3 summarizes the incidence rate ratio, model-fitted level vs expected (counterfactual) level if the COVID-19 outbreak did not occur, of service use in April 2020. The difference between those with and without dementia was not apparent in home visit services. However, for commuting services, only those without dementia experienced statistically significant loss in service use except for “Outpatient day long-term care for persons with dementia,” which only 1147 persons without dementia (vs 47,256 persons with dementia) used in April 2020. A statistically significant loss in service use was observed in all dementia categories in 2 of short-stay services, namely, “Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility)” and “Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care.”

Fig. 2.

Monthly uses of long-term care service stratified by dementia severity from January 2019 to December 2020. In each panel, monthly uses of long-term care service (total sum of service use by all service users) are shown. The dots show observed total monthly times of service used, the solid line indicates the model-fitted monthly times of service use, and the dashed line represents the model-based expected (or counterfactual level if the COVID-19 had not occurred) times of service use. The colors purple, blue, brown, and dark green represent normal, mild dementia, moderate dementia, and severe dementia, respectively. For prevention services (panels F, G, H, and O), because very few persons with moderate or severe dementia use prevention services, 3 dementia categories (mild, moderate, and severe) were combined into 1 category (dementia). Pink rectangular shades indicate the period during which the Japanese government declared the state of emergency (from April 7 to May 25, 2020).

Fig. 3.

Change in use of long-term care service from expected level [the incidence rate ratio of model-fitted level and expected (counterfactual) level] in April 2020. The dots show point estimates of incidence rate ratio, model-fitted level vs expected (counterfactual) level if the COVID-19 outbreak did not occur, in April 2020. The lines indicate 95% CI of the estimates. The colors purple, blue, brown, and dark green represent normal, mild dementia, moderate dementia, and severe dementia, respectively. For prevention services [Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care, Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care, Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care, Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care (short stay)], because very few persons with moderate or severe dementia use prevention services, 3 dementia categories (mild, moderate, and severe) were combined into 1 category (dementia).

The heterogeneity in changes in service utilization due to service types and dementia severity was more obvious after the results from the analysis of each service were synthesized using random effects meta-analysis (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). A significant reduction in service use was observed for all 3 service types at the start of the state of emergency, but the decline was more precipitous in commuting services and short-stay services (10.9%, 95% CI 10.1%-11.6%, and 24.7%, 95% CI 10.0%-37.0%, respectively) than in home visit services (4.2%, 95% CI 2.6%-5.8%). Service use by those with mild dementia was higher than that by those without dementia in all 3 service types at the start of the state of emergency. Higher service use by those with dementia was observed in commuting and short-stay services for moderate dementia and in short-stay services for severe dementia.

Table 2.

Summary of Meta-analyses Synthesizing Coefficients of Interrupted Time-Series Analysis on Service Uses of Each Service in 3 Service Types

| Variables | Service Type | IRR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in level at the start of the SOE | Home visit services | 0.958 | 0.942, 0.974 | <.001 |

| Commuting services | 0.891 | 0.884, 0.899 | <.001 | |

| Short-stay services | 0.753 | 0.630, 0.900 | .002 | |

| Loge (incident COVID-19 cases) | Home visit services | 1.001 | 0.999, 1.003 | .23 |

| Commuting services | 0.998 | 0.997, 0.999 | <.001 | |

| Short-stay services | 1.003 | 0.995, 1.010 | .46 | |

| Mild dementia × Change in level at the start of the SOE | Home visit services | 1.035 | 1.024, 1.046 | <.001 |

| Commuting services | 1.045 | 1.030, 1,060 | <.001 | |

| Short-stay services | 1.044 | 1.021, 1.067 | <.001 | |

| Moderate dementia × Change in level at the start of the SOE | Home visit services | 1.013 | 0.986, 1.042 | .34 |

| Commuting services | 1.054 | 1.027, 1.081 | <.001 | |

| Short-stay services | 1.064 | 1.019, 1.111 | .01 | |

| Severe dementia × Change in level at the start of the SOE | Home visit services | 0.984 | 0.955, 1.015 | .31 |

| Commuting services | 1.035 | 0.998, 1.073 | .06 | |

| Short-stay services | 1.061 | 1.043, 1.080 | <.001 |

IRR, incidence rate ratio; SOE, state of emergency.

The reference of dementia categories (mild, moderate, and severe dementia) is normal.

Detailed results of the meta-analyses are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Results of random effects meta-analyses synthesizing coefficients of interrupted times series analysis on service uses of each service in 3 service types. (A) Change in level at the start of state of emergency. (B) Log (incident COVID-19 cases). (C) Interaction between change in level at the start of state of emergency and mild dementia. (D) Interaction between change in level at the start of state of emergency and moderate dementia. (E) Interaction between change in level at the start of state of emergency and severe dementia.

The effect of incident COVID-19 cases was relatively limited and statistically significant in commuting service only, with a reduction of 0.2% per loge-transformed increase (95% CI 0.1%-0.3%).

Analyses of Number of Service Users

The results from analyses with the change in service users as an outcome are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 5 to Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Tables 7 and 8. Overall, the results replicated those obtained in the main analyses with the change in the amount of service use as an outcome.

Supplementary Fig. 2.

Monthly users of long-term care service from January 2019 to December 2020. In each panel, monthly users of long-term care service are shown. The dots show observed total monthly number of users, the solid line indicates the model-fitted monthly number of users, and the dashed line represents the model-based expected (or counterfactual level if the COVID-19 had not occurred) monthly number of service users. Pink rectangular shades indicate the period during which the Japanese government declared the state of emergency (from April 7 to May 25, 2020).

Supplementary Fig. 3.

Monthly users of long-term care service stratified by dementia severity from January 2019 to December 2020. In each panel, monthly users of long-term care service are shown. The dots show observed total monthly number of users, the solid line indicates the model-fitted monthly number of users, and the dashed line represents the model-based expected (or counterfactual level if the COVID-19 had not occurred) monthly number of users. The colors purple, blue, brown, and dark green represent normal, mild dementia, moderate dementia, and severe dementia, respectively. For prevention services (panels F, G, H, and O), because very few persons with moderate or severe dementia use prevention services, 3 dementia categories (mild, moderate, and severe) were combined into 1 category (dementia). Pink rectangular shades indicate the period during which the Japanese government declared the state of emergency (from April 7 to May 25, 2020).

Supplementary Fig. 4.

Change in number of long-term care service users from expected level [the ratio of model-fitted level and expected (counterfactual) level] in April 2020. The dots show point estimates of incidence rate ratio, model-fitted level vs expected (counterfactual) level if the COVID-19 outbreak did not occur, in April 2020. The lines indicate 95% CI of the estimates. The colors purple, blue, brown, and dark green represent normal, mild dementia, moderate dementia, and severe dementia, respectively. For prevention services (Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care, Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care, Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care, Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care [short stay]), because very few persons with moderate or severe dementia use prevention services, 3 dementia categories (mild, moderate, and severe) were combined into 1 category (dementia).

Supplementary Fig. 5.

Results of random effects meta-analyses synthesizing coefficients of interrupted times series analysis on service users of each service in 3 service types. (A) Change in level at the start of state of emergency. (B) Log (incident COVID-19 cases). (C) Interaction between change in level at the start of state of emergency and mild dementia. (D) Interaction between change in level at the start of state of emergency and moderate dementia. (E) Interaction between change in level at the start of state of emergency and severe dementia.

Discussion

In the analysis of comprehensive nationwide claims data, we observed a substantial decline in LTC service use in April 2020, when the state of emergency was declared. During the state of emergency, some prefectural governor requested temporal closure of care service as an element of infection prevention, and many care service providers suspended service provision responding to the request or voluntarily, leading to widespread decline in care services. The decline continued to May, followed by gradual recovery after the state of emergency was lifted. We demonstrated that the association of the state of emergency with decline in service use was significant, whereas the association of the status of the infection spread with service use was quite limited. This finding has an important implication in that policy regarding the implementation of large-scale infection prevention measures such as the state of emergency could have a profound impact disproportionate to the magnitude of infection spread, and therefore its consequences should be carefully considered, balancing its negative impacts on the vulnerable population against its effects of infection prevention.

We demonstrated that the effects of the state of emergency on LTC service use varied depending on service types. The degree of decline in LTC service use was more marked in commuting and short-stay services, both of which are provided at service facilities, compared with home visit services provided at user's homes. This may be because of people's avoidance of crowded places and their decision to discontinue service voluntarily, either for fear of infection or in compliance with social distancing recommendations to reduce the risk of contracting the coronavirus. Measures taken by the MHLW to enable the continued provision of LTC services under the influence of COVID-19 also played a role. For example, LTC service providers were allowed to receive reimbursement when they provided home visit services instead of commuting services, which were originally approved. This could lead to increased use of home visit services as a substitute for commuting services. Another explanation may be that home visit services provide essential daily care such as assistance with meals, bathing, and excretion, and the interruption of these services can bring about immediate and devastating consequences.

Another finding of our study is that dementia severity of service users was further associated with the degree of decline in service use. Dementia was associated with increased use of LTC services, particularly in commuting and short-stay services, partially canceling out the decline in service use that occurred during the state of emergency. This might be because of a precipitous decline in the physical and mental functions of persons with dementia, resulting in increased need for LTC services. However, it is highly unlikely considering the short time span from the emergence of COVID-19 and declaration of the state of emergency to a decline in service use. A more plausible explanation is that this reflects an effort of family members and service providers to maintain, as usual as possible, the use and provision of LTC services for older adults with dementia to prevent the disruption of daily care and consequent deterioration of physical and mental conditions.

Strengths and Limitations

One of the major strengths of our study is its use of the LTC Insurance Comprehensive Database in Japan, which allowed us to conduct analyses using individual person-level data, including more than 5 million older adults, without fear of introducing selection bias. Our analyses covered all prefectures in Japan and incorporated the regional heterogeneity in dementia policy, the incidence of COVID-19, and infection prevention measures. One previous study in Japan analyzed the data of LTC services collected via a data platform owned by a private company and reported that the change in the use of LTC services may differ depending on the type of services.27 Generally, their findings were consistent with ours; however, the representativeness of the collected data is questionable because of its small sample size and data collection method, which relied on a specific system supported by a private company.

This study has certain limitations. First, data on important characteristics, such as comorbidities and socioeconomic status, were not available in the data set and, therefore, not included in the analysis. Second, the data analyzed in this study did not include data prior to 2018, and we cannot exclude the possibility that long-term trends over several years confound the study findings. Future studies should investigate longer time periods and adopt an analytic method to incorporate long-term trends. Finally, although the study described the change in LTC service use and found some associated factors, it did not provide suggestions regarding how the change in LTC service was produced. This may be because of service users refraining from using services for fear of COVID-19 or service providers shutting down or reducing services because of the spread of infection or staff shortages.

Conclusions and Implications

In an analysis of comprehensive nationwide LTC claims data, we delineated the change in LTC service use for older adults living at home during the COVID-19 outbreak. LTC service use in Japan declined considerably during the state of emergency and then gradually recovered. The decline was mostly attributable to the state of emergency rather than COVID-19 infection, which had limited association with service use. Therefore, the state of emergency targeted at prefectures with increasing infection cases needs to be considered to minimize loss in LTC service utilization. Our finding that there was heterogeneity in changes in service utilization due to service types and dementia severity would help LTC professionals identify vulnerable groups and guide future plans geared toward effective infection prevention while alleviating unfavorable impacts by infection prevention measures. Future research is needed to evaluate the effects of changes in service use on the mental and physical conditions of older adults during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as one of the projects in the Health and Welfare Bureau for the Elderly of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, and did not receive any funding.

Footnotes

Funding: This research did not receive any funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

Physical Disability Classification in the Long-Term Care Insurance System in Japan

| Physical Disability Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Independent | Person who has no physical disability |

| J | A person who has a physical disability (because of sickness after-effects) but is almost independent in his or her daily life and can go out alone J1: Go out using transportation J2: Go out to the neighborhood |

| A | A person who can do his or her daily routine indoors by themselves and needs help from a caregiver when going out to the neighborhood A1: Go out with assistance and live mostly out of bed during the day A2: Rarely go out and sleep or wake up during the day |

| B | A person who needs help performing his or her daily routine indoors from a caregiver and spends most of his or her day in bed but is able to maintain a sitting position B1: Transfer to a wheelchair and eat and excrete away from bed B2: Transfer to a wheelchair with assistance |

| C | A person who spends his or her day in bed and needs help from a caregiver for eating, toileting, and changing clothes C1: Roll over by themselves C2: Unable to turn over by themselves |

Supplementary Table 2.

Cognitive Decline Classification in the Long-Term Care Insurance System in Japan

| Cognitive Decline Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Independent | Person who has no cognitive decline |

| I | A person who has some cognitive symptoms but is almost independent in his or her daily life both at home and socially |

| II | A person who has some behavioral and communication difficulties that interfere with his or her daily life but is independent if someone pays attention to them IIa: The above condition is observed outdoors IIb: The above condition is observed both at home and outdoors |

| III | A person who requires care because of behavioral and communication difficulties that interfere with his or her daily life IIIa: The above condition is observed mainly during the daytime IIIb: The above condition is observed mainly at night |

| IV | A person who requires constant care because of frequent behavioral and communication difficulties that interfere with his or her daily life |

| M | A person who has significant medical symptoms, problematic behaviors, or severe physical diseases requiring specialized medical care |

Supplementary Table 3.

Certification Levels in Long-Term Care Insurance System in Japan

| Certification Level | Description |

|---|---|

| Independent | A person who can perform ADL∗ and IADL† independently and needs neither support nor care |

| Support required 1 | A person who can perform most ADL independently, but needs some support for IADL |

| Support required 2 | A person whose ability to perform IADL is slightly lower than that of persons in the Support required 1 level and needs more support |

| Care level 1 | A person whose ability to perform IADL declined further from that of persons in the Support required category and needs care |

| Care level 2 | A person who needs support for ADL in addition to support for IADL |

| Care level 3 | A person whose abilities to perform ADL and IADL declined significantly and needs constant care |

| Care level 4 | A person whose ability to perform ADL declined further from that of persons in Care level 3 and has difficulty living his or her daily life without care |

| Care level 5 | A person whose ability to perform ADL declined further from that of persons in Care level 4, and it is almost impossible to live his or her daily lives without care |

ADL (the Activities of Daily Living) are basic skills required to independently care for oneself, such as eating, bathing, and walking.

IADL (the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living) are skills required to live independently in a community, such as cooking, cleaning, and transportation.

Supplementary Table 4.

Monthly Number of Incident COVID-19 Cases in January to September 2020 by Prefectures in Japan

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 12 | 193 | 1930 | 12,089 | 2511 | 1747 | 17,373 | 31,981 | 15,045 |

| Hokkaido | 1 | 69 | 107 | 590 | 324 | 172 | 165 | 353 | 326 |

| Aomori | 0 | 0 | 8 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Iwate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 4 |

| Miyagi | 0 | 1 | 6 | 81 | 0 | 6 | 66 | 47 | 199 |

| Akita | 0 | 0 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 31 | 4 |

| Yamagata | 0 | 0 | 1 | 67 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Fukushima | 0 | 0 | 4 | 69 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 72 | 92 |

| Ibaraki | 0 | 0 | 24 | 139 | 5 | 6 | 120 | 251 | 112 |

| Tochigi | 0 | 1 | 12 | 41 | 12 | 14 | 116 | 108 | 127 |

| Gunma | 0 | 0 | 18 | 122 | 9 | 4 | 37 | 250 | 261 |

| Saitama | 0 | 0 | 100 | 750 | 156 | 131 | 1184 | 1614 | 726 |

| Chiba | 1 | 13 | 159 | 665 | 67 | 60 | 690 | 1396 | 845 |

| Tokyo | 3 | 18 | 489 | 3747 | 958 | 994 | 6464 | 8125 | 4918 |

| Kanagawa | 1 | 23 | 119 | 882 | 344 | 133 | 982 | 2475 | 1936 |

| Niigata | 0 | 1 | 30 | 45 | 7 | 1 | 28 | 32 | 28 |

| Toyama | 0 | 0 | 2 | 195 | 30 | 0 | 11 | 149 | 31 |

| Ishikawa | 0 | 6 | 7 | 238 | 47 | 2 | 21 | 305 | 150 |

| Fukui | 0 | 0 | 20 | 102 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 89 | 16 |

| Yamanashi | 0 | 0 | 5 | 47 | 13 | 10 | 23 | 76 | 17 |

| Nagano | 0 | 2 | 6 | 59 | 10 | 1 | 28 | 151 | 53 |

| Gifu | 0 | 2 | 23 | 124 | 1 | 6 | 175 | 224 | 71 |

| Shizuoka | 0 | 1 | 7 | 62 | 5 | 6 | 188 | 214 | 63 |

| Aichi | 2 | 27 | 149 | 309 | 24 | 17 | 1305 | 2767 | 830 |

| Mie | 1 | 0 | 10 | 34 | 0 | 1 | 55 | 279 | 129 |

| Shiga | 0 | 0 | 7 | 89 | 7 | 1 | 70 | 282 | 52 |

| Kyoto | 1 | 1 | 67 | 251 | 40 | 23 | 408 | 666 | 310 |

| Osaka | 1 | 3 | 240 | 1377 | 186 | 53 | 2224 | 4502 | 2065 |

| Hyogo | 0 | 0 | 148 | 498 | 61 | 7 | 514 | 1057 | 443 |

| Nara | 1 | 0 | 10 | 73 | 8 | 0 | 143 | 284 | 52 |

| Wakayama | 0 | 13 | 5 | 44 | 2 | 1 | 86 | 80 | 12 |

| Tottori | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 7 | 13 |

| Shimane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 108 | 3 |

| Okayama | 0 | 0 | 4 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 53 | 66 | 12 |

| Hiroshima | 0 | 0 | 6 | 149 | 12 | 1 | 161 | 129 | 119 |

| Yamaguchi | 0 | 0 | 6 | 26 | 5 | 0 | 16 | 115 | 33 |

| Tokushima | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 19 | 105 | 18 |

| Kagawa | 0 | 0 | 2 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 32 | 16 |

| Ehime | 0 | 0 | 9 | 38 | 35 | 0 | 7 | 25 | 0 |

| Kochi | 0 | 1 | 16 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 45 | 13 |

| Fukuoka | 0 | 2 | 44 | 596 | 117 | 92 | 1074 | 2671 | 444 |

| Saga | 0 | 0 | 2 | 38 | 7 | 0 | 35 | 155 | 8 |

| Nagasaki | 0 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 57 | 157 | 5 |

| Kumamoto | 0 | 5 | 9 | 33 | 1 | 1 | 142 | 329 | 55 |

| Oita | 0 | 0 | 29 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 79 | 13 |

| Miyazaki | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 124 | 217 | 7 |

| Kagoshima | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 241 | 110 | 55 |

| Okinawa | 0 | 3 | 6 | 134 | 4 | 0 | 253 | 1731 | 358 |

Unit: cases.

Data were drawn from the website “Domestic Outbreak Status” managed by Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare, Japan. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/covid-19/kokunainohasseijoukyou.html

Supplementary Table 5.

Characteristics of Adults Who Used Long-Term Care Services Between January 2019 and September 2020 (N = 5,040,158)

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 85.8 (79.7, 90.5) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 35.7 |

| Women | 64.3 |

| Certification level | |

| Support required 1 | 5.1 |

| Support required 2 | 7.2 |

| Care level 1 | 32.0 |

| Care level 2 | 24.2 |

| Care level 3 | 14.6 |

| Care level 4 | 10.7 |

| Care level 5 | 6.3 |

| Dementia severity | |

| Normal | 36.3 |

| Mild | 44.8 |

| Moderate | 16.3 |

| Severe | 2.7 |

The median and interquartile range is shown for age. The other values are percentages.

Supplementary Table 6.

Number of Long-Term Care Services Used Between January 2019 and September 2020

| 2019 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Change Rate | Mar | Change Rate | Apr | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 22,434,096 | 21,355,950 | −4.81 | 23,158,788 | 8.44 | 22,813,756 | −1.49 |

| Home visit bathing service | 384,417 | 374,032 | −2.70 | 404,006 | 8.01 | 403,743 | −0.07 |

| Home visit nursing care | 5,569,902 | 5,523,302 | −0.84 | 5,877,088 | 6.41 | 6,064,023 | 3.18 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 2,287,152 | 2,313,064 | 1.13 | 2,455,638 | 6.16 | 2,490,663 | 1.43 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 2,429,890 | 2,478,868 | 2.02 | 2,547,636 | 2.77 | 2,580,473 | 1.29 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 793,185 | 804,045 | 1.37 | 846,697 | 5.30 | 876,391 | 3.51 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 373,784 | 380,694 | 1.85 | 397,902 | 4.52 | 397,841 | −0.02 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 153,404 | 155,971 | 1.67 | 160,574 | 2.95 | 162,240 | 1.04 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 36,965,025 | 36,599,534 | −0.99 | 40,185,263 | 9.80 | 40,578,806 | 0.98 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 13,292,318 | 13,276,384 | −0.12 | 14,528,862 | 9.43 | 14,791,623 | 1.81 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 9,113,922 | 9,130,304 | 0.18 | 9,905,212 | 8.49 | 10,042,396 | 1.38 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 1,532,296 | 1,512,540 | −1.29 | 1,643,969 | 8.69 | 1,642,581 | −0.08 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 14,798,743 | 13,855,181 | −6.38 | 15,288,895 | 10.35 | 14,613,077 | −4.42 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 1,500,876 | 1,412,403 | −5.89 | 1,601,273 | 13.37 | 1,683,394 | 5.13 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 143,335 | 134,674 | −6.04 | 151,902 | 12.79 | 143,347 | −5.63 |

| 2019 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May | Change Rate | Jun | Change Rate | Jul | Change Rate | Aug | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 23,397,329 | 2.56 | 22,851,289 | −2.33 | 23,850,244 | 4.37 | 23,407,605 | −1.86 |

| Home visit bathing service | 412,438 | 2.15 | 392,268 | −4.89 | 422,380 | 7.68 | 411,389 | −2.60 |

| Home visit nursing care | 6,158,287 | 1.55 | 5,949,926 | −3.38 | 6,568,169 | 10.39 | 6,182,750 | −5.87 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 2,499,220 | 0.34 | 2,427,361 | −2.88 | 2,681,332 | 10.46 | 2,459,226 | −8.28 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 2,575,821 | −0.18 | 2,617,295 | 1.61 | 2,688,230 | 2.71 | 2,602,455 | −3.19 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 892,541 | 1.84 | 869,107 | −2.63 | 965,642 | 11.11 | 897,413 | −7.07 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 406,216 | 2.11 | 395,668 | −2.60 | 437,343 | 10.53 | 402,220 | −8.03 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 162,002 | −0.15 | 162,670 | 0.41 | 166,531 | 2.37 | 161,813 | −2.83 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 41,922,195 | 3.31 | 40,192,210 | −4.13 | 43,146,677 | 7.35 | 41,762,526 | −3.21 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 14,990,179 | 1.34 | 14,583,593 | −2.71 | 15,635,670 | 7.21 | 14,741,528 | −5.72 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 10,329,919 | 2.86 | 9,883,130 | −4.33 | 10,678,165 | 8.04 | 10,131,499 | −5.12 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 1,688,548 | 2.80 | 1,613,854 | −4.42 | 1,722,541 | 6.73 | 1,672,858 | −2.88 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 15,112,014 | 3.41 | 14,733,331 | −2.51 | 15,224,389 | 3.33 | 15,418,671 | 1.28 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 1,812,172 | 7.65 | 1,778,778 | −1.84 | 1,727,863 | −2.86 | 1,707,434 | −1.18 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 147,106 | 2.62 | 141,174 | −4.03 | 148,038 | 4.86 | 156,776 | 5.90 |

| 2019 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sep | Change Rate | Oct | Change Rate | Nov | Change Rate | Dec | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 23,103,746 | −1.30 | 24,347,355 | 5.38 | 23,910,584 | −1.79 | 24,266,180 | 1.49 |

| Home visit bathing service | 391,853 | −4.75 | 438,198 | 11.83 | 430,001 | −1.87 | 435,192 | 1.21 |

| Home visit nursing care | 6,087,374 | −1.54 | 6,607,474 | 8.54 | 6,306,461 | −4.56 | 6,305,615 | −0.01 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 2,447,754 | −0.47 | 2,662,555 | 8.78 | 2,547,051 | −4.34 | 2,516,008 | −1.22 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 2,658,048 | 2.14 | 2,732,856 | 2.81 | 2,732,737 | 0.00 | 2,761,469 | 1.05 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 907,121 | 1.08 | 990,760 | 9.22 | 945,006 | −4.62 | 946,671 | 0.18 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 413,945 | 2.92 | 444,974 | 7.50 | 428,474 | −3.71 | 424,731 | −0.87 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 164,768 | 1.83 | 169,410 | 2.82 | 168,828 | −0.34 | 171,132 | 1.36 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 40,775,877 | −2.36 | 43,572,625 | 6.86 | 42,651,439 | −2.11 | 41,838,015 | −1.91 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 14,414,750 | −2.22 | 15,570,156 | 8.02 | 15,212,790 | −2.30 | 14,875,158 | −2.22 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 10,055,083 | −0.75 | 10,687,104 | 6.29 | 10,447,095 | −2.25 | 10,214,108 | −2.23 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 1,629,089 | −2.62 | 1,721,609 | 5.68 | 1,687,632 | −1.97 | 1,652,476 | −2.08 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 15,028,970 | −2.53 | 15,523,555 | 3.29 | 15,247,753 | −1.78 | 15,574,772 | 2.14 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 1,693,561 | −0.81 | 1,870,029 | 10.42 | 1,889,020 | 1.02 | 1,756,315 | −7.03 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 146,748 | −6.40 | 155,810 | 6.18 | 153,548 | −1.45 | 146,989 | −4.27 |

| 2020 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Change Rate | Feb | Change Rate | Mar | Change Rate | Apr | Change Rate | May | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 23,924,789 | −1.41 | 23,304,782 | −2.59 | 24,867,488 | 6.71 | 24,501,792 | −1.47 | 24,938,353 | 1.78 |

| Home visit bathing service | 415,505 | −4.52 | 417,803 | 0.55 | 440,308 | 5.39 | 455,329 | 3.41 | 465,629 | 2.26 |

| Home visit nursing care | 6,124,555 | −2.87 | 5,977,013 | −2.41 | 6,538,980 | 9.40 | 6,431,887 | −1.64 | 6,160,953 | −4.21 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 2,415,460 | −4.00 | 2,394,354 | −0.87 | 2,583,048 | 7.88 | 2,443,935 | −5.39 | 2,292,398 | −6.20 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 2,740,090 | −0.77 | 2,747,000 | 0.25 | 2,768,520 | 0.78 | 2,682,056 | −3.12 | 2,609,711 | −2.70 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 924,221 | −2.37 | 916,609 | −0.82 | 985,271 | 7.49 | 943,006 | −4.29 | 883,867 | −6.27 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 411,697 | −3.07 | 411,701 | 0.00 | 440,737 | 7.05 | 410,253 | −6.92 | 389,637 | −5.03 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 169,382 | −1.02 | 168,446 | −0.55 | 171,745 | 1.96 | 168,315 | −2.00 | 164,852 | −2.06 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 40,302,937 | −3.67 | 40,738,893 | 1.08 | 41,840,931 | 2.71 | 39,770,797 | −4.95 | 39,808,479 | 0.09 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 14,116,928 | −5.10 | 14,215,078 | 0.70 | 14,487,218 | 1.91 | 13,352,460 | −7.83 | 12,858,425 | −3.70 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 9,848,379 | −3.58 | 9,949,679 | 1.03 | 10,197,811 | 2.49 | 9,611,520 | −5.75 | 9,561,594 | −0.52 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 1,584,624 | −4.11 | 1,597,944 | 0.84 | 1,643,270 | 2.84 | 1,558,012 | −5.19 | 1,562,694 | 0.30 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 15,431,079 | −0.92 | 14,858,449 | −3.71 | 15,411,464 | 3.72 | 14,388,267 | −6.64 | 14,785,753 | 2.76 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 1,564,197 | −10.94 | 1,490,749 | −4.70 | 1,477,840 | −0.87 | 1,313,730 | −11.10 | 1,193,371 | −9.16 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 146,253 | −0.50 | 141,950 | −2.94 | 130,987 | −7.72 | 105,420 | −19.52 | 102,673 | −2.61 |

| 2020 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jun | Change Rate | Jul | Change Rate | Aug | Change Rate | Sep | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 24,805,683 | −0.53 | 25,182,374 | 1.52 | 24,704,468 | −1.90 | 24,553,867 | −0.61 |

| Home visit bathing service | 478,913 | 2.85 | 488,459 | 1.99 | 467,739 | −4.24 | 469,965 | 0.48 |

| Home visit nursing care | 6,903,839 | 12.06 | 6,969,255 | 0.95 | 6,456,078 | −7.36 | 6,707,039 | 3.89 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 2,733,759 | 19.25 | 2,736,672 | 0.11 | 2,477,708 | −9.46 | 2,632,932 | 6.26 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 2,815,443 | 7.88 | 2,844,802 | 1.04 | 2,742,110 | −3.61 | 2,833,909 | 3.35 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 1,032,128 | 16.77 | 1,054,695 | 2.19 | 972,305 | −7.81 | 1,033,949 | 6.34 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 468,162 | 20.15 | 471,334 | 0.68 | 429,156 | −8.95 | 463,916 | 8.10 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 176,258 | 6.92 | 176,597 | 0.19 | 171,058 | −3.14 | 175,988 | 2.88 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 42,617,965 | 7.06 | 43,487,707 | 2.04 | 41,170,146 | −5.33 | 41,659,813 | 1.19 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 14,750,118 | 14.71 | 14,831,001 | 0.55 | 13,735,827 | −7.38 | 14,013,611 | 2.02 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 10,486,658 | 9.67 | 10,676,968 | 1.81 | 9,934,005 | −6.96 | 10,198,478 | 2.66 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 1,640,029 | 4.95 | 1,669,780 | 1.81 | 1,601,474 | −4.09 | 1,610,482 | 0.56 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 14,924,358 | 0.94 | 15,674,082 | 5.02 | 15,849,852 | 1.12 | 15,563,588 | −1.81 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 1,358,368 | 13.83 | 1,495,925 | 10.13 | 1,468,201 | −1.85 | 1,499,462 | 2.13 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 110,881 | 7.99 | 125,577 | 13.25 | 127,149 | 1.25 | 133,882 | 5.30 |

Change rate is the unadjusted change in number of times service used compared to the previous month.

Supplementary Table 7.

Number of Long-Term Care Service Users Between January 2019 and September 2020

| 2019 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Change Rate | Mar | Change Rate | Apr | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 923,024 | 919,747 | −0.36 | 928,683 | 0.97 | 929,732 | 0.11 |

| Home visit bathing service | 58,177 | 57,909 | −0.46 | 58,939 | 1.78 | 58,736 | −0.34 |

| Home visit nursing care | 418,668 | 418,464 | −0.05 | 425,472 | 1.67 | 429,420 | 0.93 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 87,682 | 87,757 | 0.09 | 88,695 | 1.07 | 88,880 | 0.21 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 650,690 | 656,108 | 0.83 | 667,613 | 1.75 | 672,653 | 0.75 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 71,151 | 71,650 | 0.70 | 72,660 | 1.41 | 73,148 | 0.67 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 17,521 | 17,629 | 0.62 | 17,678 | 0.28 | 17,700 | 0.12 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 47,644 | 47,930 | 0.60 | 48,833 | 1.88 | 49,056 | 0.46 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 1,069,807 | 1,064,888 | −0.46 | 1,080,244 | 1.44 | 1,089,336 | 0.84 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 406,467 | 403,341 | −0.77 | 409,979 | 1.65 | 416,963 | 1.70 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 378,493 | 377,441 | −0.28 | 382,792 | 1.42 | 384,975 | 0.57 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 51,634 | 51,289 | −0.67 | 51,640 | 0.68 | 51,654 | 0.03 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 292,793 | 284,082 | −2.98 | 299,220 | 5.33 | 298,283 | −0.31 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 39,683 | 38,089 | −4.02 | 41,949 | 10.13 | 44,648 | 6.43 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 9045 | 8501 | −6.01 | 9609 | 13.03 | 9439 | −1.77 |

| 2019 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May | Change Rate | Jun | Change Rate | Jul | Change Rate | Aug | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 932,764 | 0.33 | 936,483 | 0.40 | 942,225 | 0.61 | 934,693 | −0.80 |

| Home visit bathing service | 58,723 | −0.02 | 58,376 | −0.59 | 58,494 | 0.20 | 57,402 | −1.87 |

| Home visit nursing care | 433,177 | 0.87 | 437,920 | 1.09 | 444,208 | 1.44 | 443,037 | −0.26 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 89,437 | 0.63 | 90,252 | 0.91 | 91,479 | 1.36 | 90,580 | −0.98 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 675,888 | 0.48 | 683,488 | 1.12 | 692,427 | 1.31 | 687,909 | −0.65 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 74,040 | 1.22 | 75,158 | 1.51 | 76,684 | 2.03 | 76,648 | −0.05 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 18,005 | 1.72 | 18,242 | 1.32 | 18,573 | 1.81 | 18,650 | 0.41 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 49,439 | 0.78 | 49,685 | 0.50 | 50,282 | 1.20 | 49,873 | −0.81 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 1,095,248 | 0.54 | 1,102,039 | 0.62 | 1,107,943 | 0.54 | 1,099,048 | −0.80 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 419,511 | 0.61 | 422,097 | 0.62 | 424,113 | 0.48 | 419,494 | −1.09 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 387,678 | 0.70 | 390,214 | 0.65 | 392,992 | 0.71 | 388,826 | −1.06 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 51,862 | 0.40 | 52,051 | 0.36 | 52,255 | 0.39 | 51,752 | −0.96 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 303,721 | 1.82 | 298,650 | −1.67 | 302,213 | 1.19 | 306,148 | 1.30 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 46,757 | 4.72 | 45,990 | −1.64 | 45,445 | −1.19 | 44,774 | −1.48 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 9719 | 2.97 | 9236 | −4.97 | 9658 | 4.57 | 10,088 | 4.45 |

| 2019 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sep | Change Rate | Oct | Change Rate | Nov | Change Rate | Dec | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 941,606 | 0.74 | 945,105 | 0.37 | 948,878 | 0.40 | 948,917 | 0.00 |

| Home visit bathing service | 57,284 | −0.21 | 57,607 | 0.56 | 57,902 | 0.51 | 58,982 | 1.87 |

| Home visit nursing care | 448,534 | 1.24 | 454,124 | 1.25 | 456,885 | 0.61 | 460,080 | 0.70 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 91,575 | 1.10 | 92,676 | 1.20 | 93,159 | 0.52 | 93,717 | 0.60 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 696,010 | 1.18 | 704,899 | 1.28 | 708,602 | 0.53 | 715,129 | 0.92 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 78,067 | 1.85 | 79,037 | 1.24 | 80,071 | 1.31 | 81,154 | 1.35 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 19,130 | 2.57 | 19,250 | 0.63 | 19,542 | 1.52 | 19,702 | 0.82 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 50,562 | 1.38 | 51,262 | 1.38 | 51,416 | 0.30 | 51,992 | 1.12 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 1,110,145 | 1.01 | 1,117,937 | 0.70 | 1,122,351 | 0.39 | 1,120,390 | −0.17 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 423,762 | 1.02 | 427,376 | 0.85 | 428,826 | 0.34 | 427,208 | −0.38 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 392,672 | 0.99 | 394,277 | 0.41 | 397,374 | 0.79 | 396,815 | −0.14 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 52,225 | 0.91 | 51,976 | −0.48 | 52,207 | 0.44 | 51,914 | −0.56 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 303,359 | −0.91 | 305,640 | 0.75 | 306,708 | 0.35 | 305,927 | −0.25 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 44,648 | −0.28 | 47,407 | 6.18 | 47,804 | 0.84 | 45,305 | −5.23 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 9653 | −4.31 | 9896 | 2.52 | 9858 | −0.38 | 9242 | −6.25 |

| 2020 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Change Rate | Feb | Change Rate | Mar | Change Rate | Apr | Change Rate | May | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 939,500 | −0.99 | 936,495 | −0.32 | 941,687 | 0.55 | 933,992 | −0.82 | 922,925 | −1.18 |

| Home visit bathing service | 57,864 | −1.9 | 57,627 | −0.41 | 58,403 | 1.35 | 59,426 | 1.75 | 59,987 | 0.94 |

| Home visit nursing care | 456,716 | −0.73 | 457,310 | 0.13 | 461,124 | 0.83 | 460,461 | −0.14 | 456,042 | −0.96 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 92,420 | −1.38 | 92,661 | 0.26 | 91,792 | −0.94 | 89,995 | −1.96 | 85,543 | −4.95 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 713,750 | −0.19 | 716,734 | 0.42 | 722,254 | 0.77 | 719,959 | −0.32 | 717,417 | −0.35 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 80,924 | −0.28 | 81,701 | 0.96 | 81,532 | −0.21 | 80,074 | −1.79 | 78,128 | −2.43 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 19,542 | −0.81 | 19,743 | 1.03 | 19,511 | −1.18 | 18,837 | −3.45 | 18,129 | −3.76 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 51,970 | −0.04 | 51,710 | −0.5 | 52,115 | 0.78 | 51,951 | −0.31 | 52,001 | 0.1 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 1,107,887 | −1.12 | 1,105,297 | −0.23 | 1,074,922 | −2.75 | 1,037,918 | −3.44 | 1,000,953 | −3.56 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 420,415 | −1.59 | 418,312 | −0.5 | 403,562 | −3.53 | 386,459 | −4.24 | 364,173 | −5.77 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 391,690 | −1.29 | 391,259 | −0.11 | 376,541 | −3.76 | 358,953 | −4.67 | 344,386 | −4.06 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 50,986 | −1.79 | 50,937 | −0.1 | 49,797 | −2.24 | 48,215 | −3.18 | 46,580 | −3.39 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 298,056 | −2.57 | −2.76 | 280,293 | −3.29 | 252,196 | −10.02 | 242,210 | −3.96 | |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 40,888 | −9.75 | −4.61 | 37,152 | −4.75 | 32,224 | −13.26 | 28,181 | −12.55 | |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 8913 | −3.56 | −4.27 | 7654 | −10.29 | 5824 | −23.91 | 5521 | −5.2 | |

| 2020 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jun | Change Rate | Jul | Change Rate | Aug | Change Rate | Sep | Change Rate | |

| Home visit long-term care | 937,708 | 1.6 | 932,789 | −0.52 | 921,199 | −1.24 | 925,286 | 0.44 |

| Home visit bathing service | 60,680 | 1.16 | 60,372 | −0.51 | 59,268 | −1.83 | 59,507 | 0.4 |

| Home visit nursing care | 471,164 | 3.32 | 473,927 | 0.59 | 469,127 | −1.01 | 474,684 | 1.18 |

| Home visit rehabilitation | 92,485 | 8.12 | 93,853 | 1.48 | 92,094 | −1.87 | 93,794 | 1.85 |

| Management guidance for in-home care | 736,110 | 2.61 | 737,163 | 0.14 | 728,524 | −1.17 | 737,634 | 1.25 |

| Home visit nursing care for preventive long-term care | 82,627 | 5.76 | 83,768 | 1.38 | 83,410 | −0.43 | 85,061 | 1.98 |

| Home visit rehabilitation for preventive long-term care | 19,759 | 8.99 | 20,068 | 1.56 | 19,953 | −0.57 | 20,516 | 2.82 |

| Management guidance for in-home care for preventive long-term care | 53,531 | 2.94 | 53,545 | 0.03 | 53,013 | −0.99 | 53,555 | 1.02 |

| Outpatient day long-term care (adult day service) | 1,065,258 | 6.42 | 1,068,834 | 0.34 | 1,044,261 | −2.3 | 1,048,981 | 0.45 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation | 397,984 | 9.28 | 399,912 | 0.48 | 388,433 | −2.87 | 390,297 | 0.48 |

| Community-based outpatient day long-term care | 372,871 | 8.27 | 374,558 | 0.45 | 364,851 | −2.59 | 366,720 | 0.51 |

| Outpatient day long-term care for patients with dementia | 48,625 | 4.39 | 48,816 | 0.39 | 48,072 | −1.52 | 48,276 | 0.42 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care | 256,491 | 5.9 | 266,772 | 4.01 | 266,343 | −0.16 | 268,958 | 0.98 |

| Short-term admission for recuperation (long-term care health facility) | 33,007 | 17.13 | 36,008 | 9.09 | 34,780 | −3.41 | 36,330 | 4.46 |

| Short-term admission for daily life long-term care for preventive long-term care | 6275 | 13.66 | 7281 | 16.03 | 7299 | 0.25 | 7834 | 7.33 |

Change rate is the unadjusted change in number of times service used compared to the previous month.

Supplementary Table 8.

Summary of Meta-analyses Synthesizing Coefficients of Interrupted Time-Series Analysis on Service Users of Each Service in 3 Service Types

| Variables | Service Type | IRR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in level at the start of the SOE | Home visit services | 0.967 | 0.959, 0.976 | <.001 |

| Commuting services | 0.912 | 0.903, 0.922 | <.001 | |

| Short-stay services | 0.679 | 0.577, 0.799 | <.001 | |

| Loge (incident COVID-19 cases) | Home visit services | 0.998 | 0.998, 0.999 | <.001 |

| Commuting services | 0.997 | 0.996, 0.998 | <.001 | |

| Short-stay services | 0.996 | 0.991, 1.001 | .16 | |

| Mild dementia × Change in level at the start of the SOE | Home visit services | 1.038 | 1.032, 1.045 | <.001 |

| Commuting services | 1.050 | 1.028, 1,073 | <.001 | |

| Short-stay services | 1.066 | 1.055, 1.078 | <.001 | |

| Moderate dementia × Change in level at the start of the SOE | Home visit services | 1.021 | 1.005, 1.037 | .01 |

| Commuting services | 1.058 | 1.018, 1.099 | .004 | |

| Short-stay services | 1.123 | 1.081, 1.166 | <.001 | |

| Severe dementia × Change in level at the start of the SOE | Home visit services | 0.993 | 0.974, 1.012 | .46 |

| Commuting services | 1.040 | 0.995, 1.086 | .09 | |

| Short-stay services | 1.126 | 1.109, 1.144 | <.001 |

IRR, incidence rate ratio; SOE, state of emergency.

The reference of dementia categories (mild, moderate, and severe dementia) is normal.

The detailed results of meta-analyses are shown in Supplementary Figure 5.

References

- 1.Gallo Marin B., Aghagoli G., Lavine K., et al. Predictors of COVID-19 severity: a literature review. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31:1–10. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkins J.L., Masoli J.A.H., Delgado J., et al. Preexisting comorbidities predicting COVID-19 and mortality in the UK biobank community cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75:2224–2230. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sepúlveda-Loyola W., Rodríguez-Sánchez I., Pérez-Rodríguez P., et al. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on Health in older people: mental and physical effects and recommendations. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:938–947. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1500-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki Y., Maeda N., Hirado D., et al. Physical activity changes and its risk factors among community-dwelling Japanese older adults during the COVID-19 epidemic: Associations with subjective well-being and health-related quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:6591. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salman D., Beaney T., C E.R., et al. Impact of social restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic on the physical activity levels of adults aged 50-92 years: a baseline survey of the CHARIOT COVID-19 Rapid Response prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e050680. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugaya N., Yamamoto T., Suzuki N., et al. Social isolation and its psychosocial factors in mild lockdown for the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of the Japanese population. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e048380. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manca R., De Marco M., Venneri A. The impact of COVID-19 infection and enforced prolonged social isolation on neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with and without dementia: a review. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:585540. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.585540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simonetti A., Pais C., Jones M., et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in elderly with dementia during COVID-19 pandemic: definition, treatment, and future directions. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:579842. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azevedo L., Calandri I.L., Slachevsky A., et al. Impact of social isolation on people with dementia and their family caregivers. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2021;81:607–617. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noguchi T., Kubo Y., Hayashi T., et al. Social isolation and self-reported cognitive decline among older adults in Japan: a longitudinal study in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22:1352–1356.e1352. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim N., Son S., Kim S., et al. Association between dementia development and COVID-19 among individuals who tested negative for COVID-19 in South Korea: a Nationwide Cohort Study. Am J Alzheimer's Dis other Dement. 2022;37 doi: 10.1177/15333175211072387. 15333175211072387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Long-Term Care Insurance Business Status Report [in Japanese] 2019. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/kaigo/osirase/jigyo/19/index.html

- 14.Giebel C., Lord K., Cooper C., et al. A UK survey of COVID-19 related social support closures and their effects on older people, people with dementia, and carers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36:393–402. doi: 10.1002/gps.5434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giebel C., Hanna K., Cannon J., et al. Decision-making for receiving paid home care for dementia in the time of COVID-19: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:333. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01719-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merrilees J., Robinson-Teran J., Allawala M., et al. Responding to the needs of persons living with dementia and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from the care ecosystem. Innov Aging. 2022;6:igac007. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igac007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierce M. The impact of COVID-19 on people who use and provide Long-Term Care in Ireland and mitigating measures. 2020. https://ltccovid.org/2020/04/15/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-people-who-use-and-provide-long-term-care-in-ireland-and-mitigating-measures/

- 18.Cipriani G., Fiorino M.D. Access to Care for Dementia Patients Suffering From COVID-19. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:796–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bianchetti A., Rozzini R., Bianchetti L., et al. Dementia Clinical Care in Relation to COVID-19. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2022;24(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11940-022-00706-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization Global report on ageism. 2021. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/demographic-change-and-healthy-ageing/combatting-ageism/global-report-on-ageism

- 21.Imai Y. Development of scales measuring dependence on care in certification of care-levels of persons with dementia [in Japanese] 2011. https://www.jcsw.ac.jp/research/kenkyujigyo/roken/h23.html#h23_01

- 22.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Government's Efforts [in Japanese] 2022. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/covid-19/seifunotorikumi.html

- 23.Bernal J.L., Cummins S., Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:348–355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhaskaran K., Gasparrini A., Hajat S., et al. Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1187–1195. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng C., Li L., Sadeghpour A. A comparison of residual diagnosis tools for diagnosing regression models for count data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20:175. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn K.P., Smyth G.K. Randomized quantile residuals. J Comput Graph Stat. 1996;5:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ito T., Hirata-Mogi S., Watanabe T., et al. Change of use in community services among disabled older adults during COVID-19 in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1148. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]