Abstract

Blood vessels are crucial for tissue development, functionality, and homeostasis and are typically a determinant in the progression of healing and regeneration. The tissue microenvironment provides physicochemical cues that affect cellular function, and the study of the microenvironment can be accelerated by engineering approaches capable of mimicking different aspects of the microenvironment. In this review, we introduce the major components of the vascular niche and focus on the roles of oxygen and the extracellular matrix. We demonstrate how vascular engineering approaches enhance our understanding of the microenvironment impact on the vasculature towards vascular regeneration and describe the current limitations and future directions toward clinical utilization.

Keywords: vascular engineering, regeneration, extracellular matrix, hypoxia

Vascular Microenvironment: Using Engineering Approaches to Enhance Vascular Regeneration

Vasculature serves as a conduit to provide oxygen and nutrients to tissues throughout the body and clear away waste generated by the tissues. Blood vessels comprising the vascular system come in many sizes and provide various functions to support the body. The function of a given blood vessel influences the composition of each layer in the blood vessel, including the endothelial cells (ECs) in the tunica intima, vascular smooth muscle cells (vSMCs), and elastin fibers in the tunica media, connective tissue in the tunica adventitia, and pericytes throughout the vessel[1]. Arteries transport oxygen-rich blood from the heart, dealing with high pressures and shear stresses. Therefore, arteries have a smaller lumen with vSMCs and elastin fibers to handle high pressures[1, 2]. Arterioles are smaller vessels branching off arteries to help deliver blood to tissues. Capillaries are tiny vessels with thin walls comprised of ECs, allowing for the rapid exchange of oxygen and nutrients. Following blood flow through capillary beds, blood enters venules and then transitions to the veins. Veins transport deoxygenated blood to the heart in large volumes and possess valves that facilitate the unidirectional, low-pressure blood flow. To accommodate low-pressure flow, vein walls are thinner than arteries, lacking the elastic lamina[1]. The variations in vessel characteristics and morphologies create a complex and diverse vascular microenvironment comprised of multiple vascular cell types and tissue cells, biochemical cues, and mechanical forces resulting from blood flow and the extracellular matrix (ECM). The composition and functions of the ECM in the microenvironment greatly influence biological processes and cellular behavior. Additionally, the levels of oxygen present in the microenvironment influence cellular behavior. Specifically, hypoxia, low oxygen levels below 5%, occurs in various biological processes, such as development and ischemia, regulating cellular responses. Disruption of the vascular microenvironment can lead to damaged vasculature, thus severely impeding tissue homeostasis and regeneration. Therefore, it is essential to deepen the understanding of the influence each component of the microenvironment has on vascular function and regeneration.

In recent years, advances in engineering and biomolecular approaches have allowed to develop research strategies to elucidate the microenvironment’s role in vascular development, homeostasis, and regeneration. For example, the miniaturization of the vasculature system with recent developments in microfluidics and organ-on-a-chip technology has augmented the understanding of how shear stress exposure and oxygen gradients affect the vascular microenvironment[3, 4]. Additionally, endothelialized microfluidic devices and advanced ECM-mimicking biomaterials have been synthesized to create artificial environments in vitro, which recapitulate the native environment and allow an improved understanding of functional mechanisms[5–7]. This review introduces the roles of ECM and hypoxia in the microenvironment. It then discusses how engineering approaches have enhanced our understanding of the influence of hypoxia and ECM by engineering in vitro microenvironments and how these can be harnessed to regulate vascular morphogenesis and regeneration.

The Extracellular Matrix and the Vascular Microenvironment

The ECM is a complex, three-dimensional (3D) assembly comprised of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), proteoglycans, and fibrous proteins such as collagens, elastin, and fibronectin[8, 9]. The major types of GAGs in the ECM are hyaluronic acid, chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate, keratin sulfate, heparan sulfate, and heparin[10]. GAGs provide structure and assist cell hydration, growth, proliferation, and migration[10]. Proteoglycans are glycosylated proteins with GAG side chains[11]. Aggrecan, perlecan, decorin, and syndecans are examples of proteoglycans, and they predominately aid structural support and cell adhesion[11]. For fibrous proteins, collagen is a triple helix glycoprotein made of α-chains that also provide structure to tissues[12]. There are numerous types of collagens important in vascular homeostasis. Collagens I and III are significant components of the interstitial matrix in the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia, providing tensile strength to support large vessel integrity and stability[13–15]. Collagens IV, XV, and XVIII are found in the basement membrane, facilitating filtration and resistance within blood vessels[13, 16]. Elastin, a hydrophobic protein produced by vSMCs in the tunica media and fibroblasts in the tunica adventitia, makes up elastic fiber networks responsible for large artery elasticity and is primarily found in the tunica media as well as the internal and external elastic membrane[17, 18]. Additionally, fibronectin is a dimer glycoprotein bonded by a disulfide bridge, and it mediates vascular cell adhesion, regulates vessel remodeling, and is predominately found in the tunica adventitia[19, 20].

Within the vascular microenvironment, there are two predominant types of ECM, basement membranes and interstitial matrix[21]. In the vasculature, the basement membrane is predominately comprised of nidogens, collagen IV, and laminins. The interstitial matrix contains various collagens, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans[21]. Properties of the vascular ECM principally depend on ECM composition and variations in matrix fiber density. Furthermore, the ECM generates forces that impact vascular cell morphology and function. vSMCs need to adjust the production of ECM proteins in response to changes in ECM tensional forces to maintain the necessary stiffness for blood flow[22]. Moreover, ECs and vSMCs experience stress and strain from the surrounding ECM. The physical forces experienced through the ECM drive mechanical signaling in the microenvironment, such as microvascular network formation responding to matrix compression[23]. In addition to mechanical signaling, signaling stemming from cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion, often facilitated by integrins, influences vascular cell growth, behavior, morphology, and functionality[24, 25]. Furthermore, signaling that results in ECM degradation through cell-derived matrix metalloproteinases enhances angiogenesis[26, 27]. In summary, the ECM within the vascular microenvironment influences vascular cell growth, function, and regeneration, highlighting the need to elucidate the various mechanisms underlying those influences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of ECM and Hypoxia studies for Vascular Regeneration

| ECM/Hypoxia | Modeling Tools | Cell Type/Animal Model | Conclusions for Vascular Regeneration | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECM & Hypoxia | 3D on-chip device with hypoxia-inducing buffer | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) & human lung fibroblasts (hLFs) | Short-term hypoxia facilitated angiogenic characteristics, while long-term hypoxia led to disruption of formed lumens | 3 |

| Hypoxia | Microfluidic device with oxygen scavenger in adjacent channel | Endothelial colony forming cell-derived endothelial cells (ECFC-ECs) & Normal hLFs | Spatial and temporal control of oxygen in microfluidic devices can model vascular behavior | 4 |

| ECM | Stiffening hydrogel | Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells (hiPSC-ECs) | ECM stiffening resulted in activation of FAK and dissociation of β-catenin from VECad-mediated adherens junctions | 7 |

| ECM | Hydrogel undergoing mechanical loading | Microvascular fragments from rats | Immediate loading inhibited angiogenesis while delayed loading enhanced networks | 23 |

| ECM | Dynamic and nondynamic crosslinks in hydrogels | Human ECFCs (hECFCs) | Dynamic hydrogels lead to the activation of FAK and metalloproteinase expression in ECFCs | 28 |

| ECM | Electrospinning and enzymatic crosslinking of gelatin-hydroxyphenylpropionic acid hydrogel | HUVECs | Fibrous hydrogel supported cell adhesion, proliferation, and spreading along with demonstrating biodegradability | 29 |

| ECM | Multifunctional hydrogel | HUVECs & db/db congenital diabetic mice | Engineered hydrogel accelerated wound healing, down-regulated TNF-α, and up-regulated CD31 and α-SMA in vivo | 32 |

| ECM | Gel-MA hydrogel with photografting | HUVECs & Human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs) | Photo-grafted patterns facilitated hASC alignment and migration along the pattern | 33 |

| ECM | Gel-MA hydrogel with microcavities inside | Human bone marrow stromal cells (hMSCs) & HUVECs | Co-cultures displayed improved vascularization, and hMSCs were suggested to differentiate towards pericytes | 34 |

| ECM | Electrospinning of a collagen and hyaluronic acid-based poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) hydrogel | HUVECs & Adipose tissue-derived MSCs | Xenogeneic-free scaffold with small pore size and high water uptake supported angiogenesis and cellular proliferation | 35 |

| ECM | Collagen hydrogel with FGF-2, platelet-derived growth factor-BB, or VEGF added | Laminin+ cells from brain slices | FGF-2 facilitated the migration and proliferation of laminin+ cells in collagen hydrogel | 37 |

| ECM | Hydrogels with RGD gradients and elastic modulus gradients | HUVECs & Human umbilical arterial smooth muscle cells (HUASMCs) | Gradients present in hydrogels influence cellular behavior | 40 |

| ECM | PEG hydrogel supplemented with protease-sensitive and cell-adhesive peptides | Human umbilical cord blood-endothelial progenitor cells (hCB-EPCs) | PEG-based hydrogels can support microvessel formation when modified with peptides that facilitate degradation and adhesion | 41 |

| ECM | Fibronectin hydrogel with VEGF and BMP2 added | HUVECs & HDFs | The hydrogel can release and uptake GFs to aid in angiogenesis | 42 |

| ECM | 3D printed hydrogel with interconnected channels and macro pores | HUVECs, fibroblasts, & balb/c female mice | Interconnected channels and macro pores have the potential to promote wound healing | 46 |

| ECM | 3D printed, gradient-structured hydrogel with various pore sizes | BMSC & male New Zealand white rabbits | Cartilage repair and blood vessel ingrowth are mediated by HIF1α/FAK axis activation and influences by pore size | 47 |

| ECM | Micropatterned surface on hydrogel | ECs, SMCs, & New Zealand white rabbits | Micropatterns influence cellular distribution and can assist with vascularization | 48 |

| ECM | Micropatterned surface | vSMCs | Micropatterns influence vSMC behavior and morphology | 50 |

| ECM | Patterned fibronectin surface | hEPCs | Patterning influenced chains and tubular structure formations to enhance formation of vascular structures | 52 |

| ECM | Heparin-like polymers added to silicone surfaces | HUVECs & HUVSMCs | Surface polymers and patterning can enhance or restrict cell responses to the surface | 57 |

| ECM | 3D printed cell-fibrin strips anchored to PCL frame | HUVECs & HNDFs | YAP activity played a regulatory role in vessel formation with no branches | 58 |

| Hypoxia | Hypoxia incubator | OBs & OECs | Short-term hypoxia promotes vascularization through balancing angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors | 72 |

| ECM & Hypoxia | Fibrinogen hydrogel with varied HA, uniform oxygen, and oxygen gradients in microfluidics | HUVECs | Provides 3D system to study various oxygen conditions and demonstrating EC networks align along gradients while adding HA to the system can help network formation | 90 |

| Hypoxia | Microfluidic device with oxygen gradient | HUVECs | Oxygen gradients guide EC migration | 91 |

| ECM & Hypoxia | Oxygen gradient in hydrogel | ECFCs | Clustering is controlled through cell-cell interaction regulators such as vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | 95 |

| ECM & Hypoxia | Hypoxic hydrogels | ECFCs | Cluster-based vasculogenesis is regulated by genes associated with oxidative stress and cAMP signaling in hypoxia | 96 |

| Hypoxia | Hypoxic chambers | hiPSC-ECs, human retinal endothelial cells, and OIR mouse model | SDF1a/CXCR4 axis in hiPSC-ECs supports revascularization of ischemic retina | 97 |

Hydrogels to Mimic the Extracellular Matrix to Recapitulate the Vascular Microenvironment

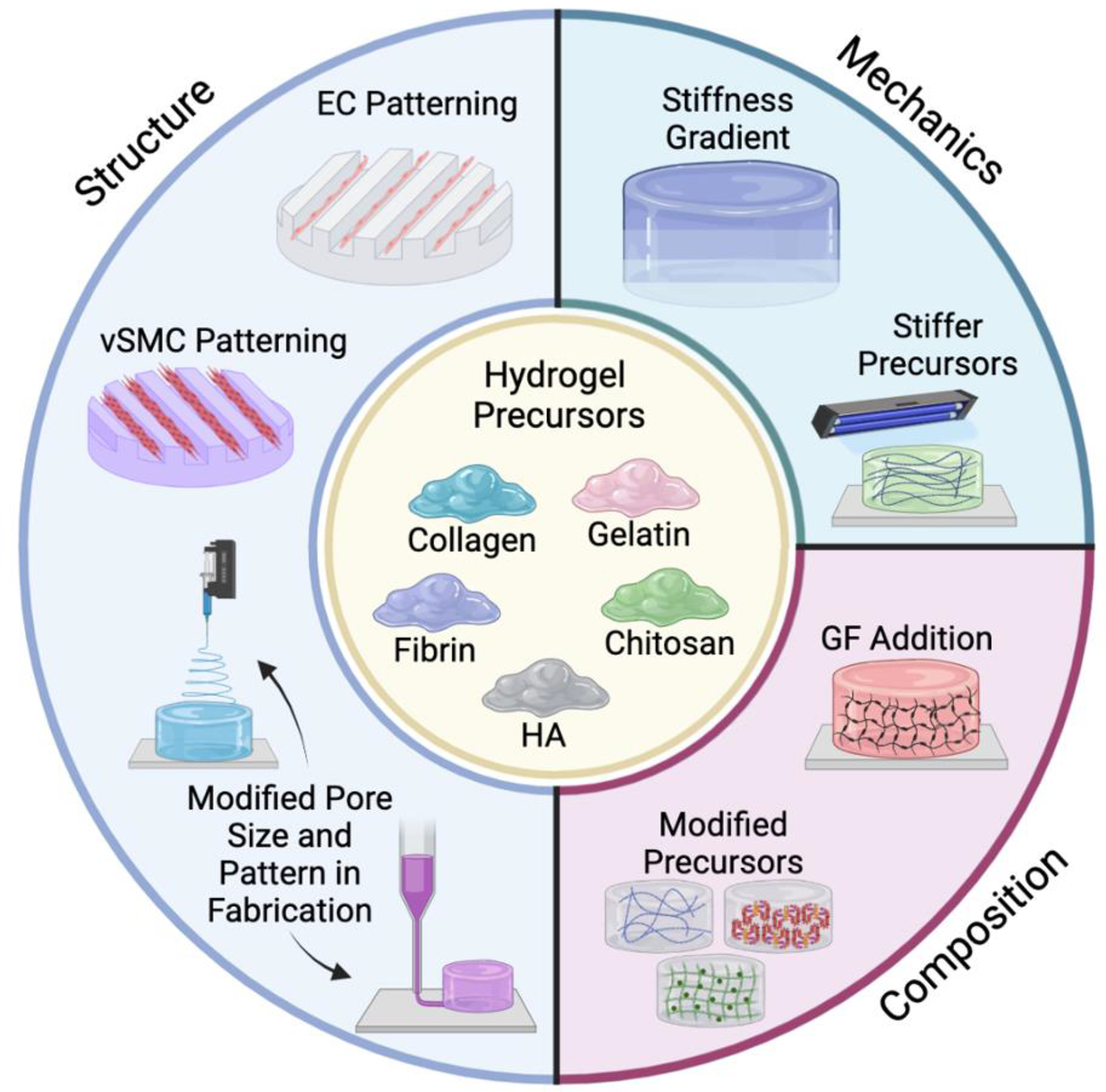

Extracellular Matrix Composition

There is much to be discovered about the functions and influence of growth factors, proteins, and proteoglycans within the complex composition of the ECM in the vascular environment. While 2D monolayer cell cultures provide insight into the behaviors and function of vascular cells, they do not faithfully recapitulate the complexity found in vivo. Cell culture in 3D allows for more complex and accurate modeling of the vascular niche. Synthetic polymers and chemical modifications to natural polymers are common tools to engineer the ECM in vitro, as they have many tunable characteristics to mimic the natural ECM. When constructing ECM-mimicking hydrogel biomaterials to study the vascular system, collagen, fibrin, gelatin, hyaluronic acid (HA), and chitosan are commonly used for hydrogel fabrication through nucleation, electrospinning, enzymatic or light-based crosslinking methods (Figure 1) [28–31]. Modeling vascularization in vitro has been accomplished by modifying collagen, gelatin, and other hydrogels backbones by adding functional groups to the chemical structure, such as collagen or gelatin with methacrylic anhydride, gelatin with adipic acid dihydrazide, and gelatin with hydroxyphenyl propionic acid [7, 28, 29, 32–35]. Additionally, ECM-mimicking hydrogels have been modified to incorporate components of the microenvironment. For example, growth factors (GF) and adhesion/degradation peptides have been included in hydrogel fabrication to study the impact of each component in vitro and more closely model the native tissue. GFs are molecules within the body that elicit various cell responses such as proliferation[36, 37]. When modeling the vascular niche in vitro using hydrogels and engineering approaches, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been incorporated into hydrogels to modulate and influence EC behavior when the cells are encapsulated in the hydrogel[38]. EC migration was facilitated by fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) when encapsulated within a collagen hydrogel that served as an ECM-mimic, demonstrating that FGF-2 functions as an angiogenic factor[37]. In wound healing models, methacryloyl grafted gelatin (Gel-MA) mixed with chitosan-catechol and further modified with polypyrrole-based nanoparticles and histatin-1 reduced inflammatory tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) as well as promoted transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and accelerated wound healing [32]. HA-based hydrogels with TGF-β1 incorporated during cell encapsulation promoted cell proliferation and vascular-like network formation modulated by CD105 and TGF-β receptor 2 co-activity[39]. Another aspect of the ECM impacting the vasculature is adhesion and degradation sites. When exposed to a gradient of the immobilized, fibronectin-derived cell adhesion peptide RGD in poly(ethylene) glycol monoacrylate macromer, vascular sprouting from spheroids comprised of human umbilical vein ECs and human umbilical arterial smooth muscle cells was observed with longer sprouts directed toward the higher concentration of RGD[40]. Degradation sites added to hydrogels to facilitate matrix remodeling by vascular cells, such as matrix metalloproteinase-sensitive peptides incorporated into hydrogel synthesis, have been shown to support microvessel formation along with evidence of lumen formation[41]. Furthermore, glycoprotein-based hydrogels such as fibronectin- and fibrin-containing biomaterials have been developed to model vascular morphogenesis due to their structural features binding to GFs, support of EC growth, promoting microvessel formation, and regulation of coagulation protein[42–45]. Engineering biomimetic hydrogels to recapitulate the complexity of the ECM composition of the ECM demonstrates the impact it has on facilitating vascular assembly and regeneration (see Clinician’s Corner).

Figure 1. Engineering Hydrogels to Model ECM for Vascular Regeneration.

Schematic illustration of the various engineering approaches utilized to create ECM-mimicking hydrogels for modeling and facilitating vascular regeneration. While a given technique is depicted as influencing one aspect of ECM modeling, such as structure, mechanics, or composition, a given approach often influences more than one aspect of ECM modeling. Created using Biorender.com.

Clinician’s Corner.

Given the central role of blood vessels in organ function, an improved understanding of the microenvironment’s role in regulating vascular growth and morphogenesis is necessary to advance regenerative medicine.

Mimicking the microenvironment for in vitro studies can aid in understanding the mechanisms governing vascular behavior. This, in turn, can be harnessed to develop targeted therapeutics because advances in biomaterials and biofabrication allow for the precise engineering of various vascular microenvironment features to recapitulate complex interactions.

The extracellular matrix greatly influences cell behaviors in diseased and healthy states, and it can provide insight into the mechanisms responsible for the behaviors and what drives them.

The role of hypoxia must be considered during therapeutic approaches, and it is necessary to balance the various oxygen levels necessary to facilitate appropriate treatments.

Engineering-modified biomaterials and vascular tissue constructs can be incorporated into treatments to improve wound healing.

Extracellular Matrix Structure

The structures and topography of the ECM within the vascular microenvironment influence vascular cell behavior and orientation. When designing hydrogels to mimic the ECM, the ultrastructure, including pores, connecting pores, fibrillar structures, and fibrillar orientation, are essential when guiding cellular responses in the intact hydrogel. 3D bioprinting has been used to print gradients in pore sizes and interconnected microchannels, with the former being shown to facilitate vascularization in a cartilage regeneration model[46, 47]. In addition to pore size, patterning is important to recapitulate vascular structure or the ECM’s micro- and nano-scale features. Patterning can be accomplished through techniques such as physical patterning or chemical patterning. Physical patterning through micropatterning creates intricate and tunable surfaces upon which vascular cells can grow[48]. Patterning channels for EC growth in vascular tissue models have been accomplished through sacrificial templates, which create network-like patterns cast in a hydrogel. The patterned channels can be lined with ECs and perfused with culture media[49]. Micropatterning has been shown to influence vascular cell orientation and spatial organization[50–52]. Micropatterning resulted in increased elongation and cell alignment in vSMCs, which indicated the vSMCs are of the healthy, contractile phenotype like vSMCs found in vivo[50, 53]. EC morphology also responds to micropatterning, aligning in the direction of contact-guidance patterns in a concave shape resulting from micropatterned cylinders[51]. Micropatterning techniques have also provided insight into the mechanisms driving vSMC behavior. vSMCs exposed to micropatterning expressed more smooth muscle myosin heavy chain and α-actin at low passage number, and vSMCs were less responsive to transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) regardless of passage number due to a decrease in TGFβ receptor 1, implicating a possible mechanism responsible for the contractile phenotype in vSMCs[50]. Engineering vascular tissue with vSMCs with the contractile phenotype would provide the correct phenotype necessary to support vascular regeneration because the generation of synthetic vSMCs characteristic of pathological conditions is undesirable. Additionally, micropatterning and spatial patterning within vessel constructs can result in biomimetic small pulmonary arteries and ECs, vSMCs, and fibroblasts which attain an anatomically correct patterning in vitro[54, 55]. Chemical patterning in hydrogels creates patterned surfaces with various chemistries to assess how cells and proteins interact with the different surface chemistries[56]. For example, heparin-like homopolymers modified to express sulfonate-containing sodium 4-vinylbenzenesulfonate supported EC adhesion to the polymer surface with higher rates of VEGF absorption, while homopolymers modified to display glycol-containing 2-(methacrylamido)glucopyranose demonstrated decrease EC attachment and lower VEGF uptake[57]. ECM structure significantly affects vascular cell morphology and function within the vascular microenvironment and can be engineered to deepen the understanding of the mechanisms driving successful vascular regeneration (Table 1).

Extracellular Matrix Mechanics

Polymer composition and crosslinking affect ECM mechanical properties and guide vascular cell behavior. Synthesizing hydrogels of varying stiffness can be accomplished through various methods, such as 3D printing, chemically crosslinking hydrogel precursors, and photo crosslinking polymer precursors. For example, 3D printing of a fibrin-EC-fibroblast mixture in a confined area resulted in tensile loading. As a result, Yes-associated protein (YAP), an essential mechanotransducer, activity was shown to play a role in the subsequent vessel formation[58]. Hydrogel stiffness is also adjustable through covalently crosslinking of the polymer precursors [59]. Modifying the hydrogel polymer precursors before crosslinking can be harnessed to modulate hydrogel stiffness and mechanical properties[28, 59]. Hydrogel precursors can be modified to support vascularization by reducing undesirable reactions between the added functional groups and the cells encapsulated within the hydrogels, such as with elastin-like proteins crossed with strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition, and increase stiffness[59]. Vascular cells have responded to changes in hydrogel mechanical properties in vitro. With hydrogels stiffening, as the vascular ECM would through aging, EC contractility increased, and β-catenin dissociated from vascular endothelial cadherin-mediated cell junctions, ultimately disrupting vascular networks[7]. Additionally, ECM stiffening was demonstrated to regulate EC barrier integrity through focal adhesion kinase (FAK) activity, and heterogeneous ECM stiffening also disrupted barrier integrity[60, 61]. Another example of vascular cells responding to changes in ECM mechanics can be observed in durotaxis, the migration of cells toward a stiffer substrate, which was observed in vSMCs when cultured on a mechanical gradient surface coated with fibronectin but not on a gradient coated with laminin[62]. Furthermore, the release of vSMC podosomes can be stimulated by cellular contact with a physical barrier[63]. Viscoelastic hydrogels promote EC contractility-mediated integrin clustering leading to matrix remodeling, thereby enabling EC morphogenesis[28]. ECM mechanics are an important consideration when investigating vascular diseased states and regeneration, for they are influenced by ECM composition and significantly impact vascular cell behavior in the vascular microenvironment. The vascular ECM is balanced through mechanical cues, biochemical cues, ECM degradation, ECM protein deposition, microstructure, and ultrastructure (Table 1). Unraveling the nuances responsible for that balance will provide greater insight into creating therapeutics for vascular regeneration.

Oxygen and the Vascular Microenvironment

Oxygen is essential for the growth and function of every tissue within the body, and the vasculature is no exception. Oxygen’s role in and influence on the vascular microenvironment depends on the needs and state of the tissue. For example, during human embryogenesis, the early stages of vasculogenesis occur in a hypoxic environment, with oxygen levels below 5%, because maternal blood is unavailable to the fetus[64]. As oxygen tension rises over the next few weeks during development, branching angiogenesis occurs and later gives rise to nonbranching angiogenesis[64]. In adulthood, blood oxygen saturation levels are typically between 95% and 100%. Additionally, oxygen levels within each adult tissue will depend on the tissue vascularization and metabolic activity, yet tissue oxygen levels range from 1% to 11%[65]. Following development, hypoxia is often associated with diseased and injured states, such as ischemic tissue resulting from myocardial infarctions and the development of tumor environments[66, 67]. In certain cancers, hypoxia is a common characteristic, resulting in signaling that enhances endothelial permeation into tumors, tumor growth, and metastasis[68–71]. However, decreasing oxygen levels for a short time can augment blood vessel formation during vascular regeneration in wound healing following injury [72]. Yet, tissue regeneration requires balance, and facilitating oxygen delivery following ischemia can also improve angiogenesis[73]. Oxygen signaling in the vascular microenvironment is regulated by transcription factors, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), and reactive oxygen species (ROS). HIFs are comprised of α- and β-subunits, and the α-subunits respond to decreases in oxygen levels and bind to β-subunits[74, 75]. HIFs then stimulate the expression of genes responsible for the proliferation, apoptosis, anaerobic metabolism, vascular tone, inflammation, and angiogenesis through TIMP-1, Tie-2, EGF, and VEGF expression, primarily through HIF-1α[76–83]. ROS, by-products of cellular metabolism, help maintain cellular function. For example, H2O2, an endogenous ROS, is necessary for EC function at low oxygen levels in the body[84]. Hypoxia and oxygen gradients are critical players in the vascular microenvironment. Understanding the nuances of the signaling pathways in the vascular microenvironment influenced by hypoxia and oxygen gradients is essential to enhance vascular regeneration further (see Clinician’s Corner).

Controlling Hypoxia to Recapitulate the Vascular Microenvironment

Oxygen and Vascular Regeneration in Microfluidic and Organ-on-Chip Devices

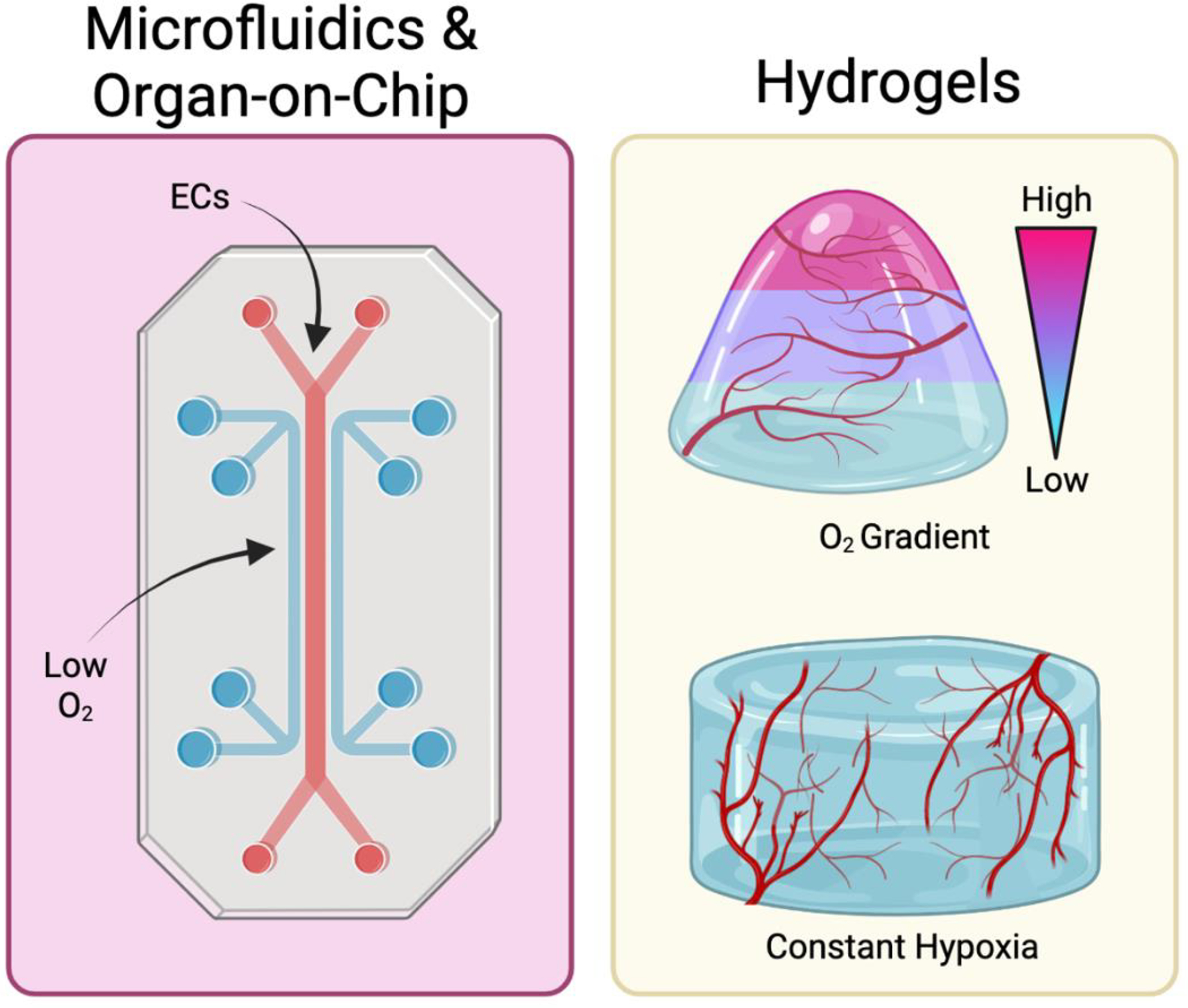

Modeling hypoxia to understand its impact on vascular processes requires tools that recreate the levels of oxygen tissues experience in vivo (Figure 2). To accomplish this, hypobaric chambers and incubators, along with inhibiting/stimulating hypoxia-induced signaling pathways, have been utilized[85, 86]. While these methodologies mimic hypoxia, there is a lack of control over the perinuclear oxygen levels and gradients. Control over and measure of pericellular oxygen levels drives the need to engineer more tunable and controllable culture conditions to study the impact of hypoxia[87]. Microfluidic and organ-on-chip devices provide highly tunable systems to model hypoxia in vitro. Microfluidic devices are small chips or platforms with chambers and channels allowing for precise control of liquids at the microscale. The miniaturization of physiologically-relevant cell culture systems in microfluidic devices helps model aspects of the vasculature microenvironment, such as oxygen gradients and shear stress in 2D and 3D. Modeling native vasculature through microfluidics begins during the device fabrication stage, as the material to fabricate the microfluidics influences oxygen availability inside the device[88]. Consideration of the oxygen permeability of material permits the regulation and monitoring of oxygen supply to cells within microfluidic devices[88]. Other important considerations highlighted through microfluidic modeling of the vasculature are cell density and cell type composition within devices. Given the miniaturized nature, high cell densities lead to rapid consumption of available oxygen, where various cell types consume oxygen at different rates, with larger cells often consuming oxygen quicker[88, 89]. Recent microfluidics models utilize 3D culture systems to recapitulate the vasculature microenvironment by incorporating shear stress and supporting cell types into the model. To accomplish this, gels supporting 3D cell culture have been incorporated into microfluidic devices[3, 4]. Following the shift to 3D culture, spatial and temporal control of oxygen was accomplished through sodium sulfate flow in a microfluidic device channel adjacent to a chamber supporting EC and fibroblast growth to demonstrate how averaged physiological levels of oxygen, around 5%, better support vessel sprouting and angiogenesis than hypoxic conditions, <5% oxygen[4]. Additionally, oxygen levels can be uniform or form an oxygen gradient within the microfluidic platform[90, 91]. When cultured under an oxygen gradient, EC networks are more prevalent in 5% oxygen gradients, and ECs migrate parallel to the gradients toward the low oxygen condition[90, 91]. Microfluidic devices have also been utilized to mimic the tumor microenvironment and suggest increased EC permeability in hypoxic conditions[92]. When considering vascular regeneration, microfluidic and organ-on-chip devices are engineered to create repeatable injury in vitro to study EC behavior during wound healing[93, 94]. Interestingly, in devices where only ECs are present, ECs can migrate to close the wound, yet when fibroblasts are present at an equal to or greater number, fibroblasts preferentially migrate into the open wound while ECs are left on the wound periphery[93, 94]. While microfluidic and organ-on-chip devices do not fully capture all the nuances of the vascular microenvironment, they provide a physiologically relevant model of the vascular microenvironment by incorporating hypoxia, shear stress, and multiple cell types in 3D, permitting a greater understanding of vascular cell behavior during regeneration.

Figure 2. Engineering Approaches to Recapitulate Hypoxia.

(left) Microfluidic devices have been utilized to incorporate hypoxic conditions in studying vascular regeneration. (right) Hydrogels with oxygen gradients and constant hypoxia have also been employed for studying the effects of varying oxygen levels during vascularization. Created using Biorender.com.

Oxygen in Hydrogels

When considering hypoxia in 3D hydrogels, monitoring oxygen levels and gradients inside the ECM-mimicking hydrogels allows for cell culture conditions that further recapitulate the native tissue environment and provide insight into the mechanisms driving cell behavior (Figure 2) [95–97]. For example, by culturing hydrogels containing retinal ECs or ECs derived from human pluripotent stem cells in hypoxic conditions (1% O2), it was discovered that revascularization of the ischemic retina is supported through the stromal cell-derived factor-1a/CXCR4 axis[97]. Controlling oxygen to model the vascular microenvironment can occur by fabricating hydrogels that consume oxygen during polymerization resulting in hypoxic gradients inside the gels[95, 96, 98]. Previously, hypoxic conditions in hydrogels have been controlled via laccase-mediated reaction converting oxygen into dihydrogen monoxide[98]. In these hypoxia-inducible hydrogels, endothelial progenitors formed vascular networks through stabilizing HIFs, which did not occur in nonhypoxic hydrogels[98]. Building upon these tunable oxygen gradients in hydrogels, materials can be layered to create discretized oxygen gradients, allowing for a more advanced cell culture system to recapitulate the vascular microenvironment[95]. Such tight oxygen regulation allows for mechanistic investigations of the cellular and biochemical processes underlying vascular homeostasis and regeneration. For example, hypoxic hydrogel culture systems enabled the modeling and subsequent characterization of the mechanisms underlying endothelial progenitor cell clustering in vitro[95, 96]. More specifically, endothelial progenitor cells cultured in hypoxic conditions demonstrated clustering regulated by genes that respond to oxidative stress, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling and clustering were also promoted by ROS produced independently of HIF[95, 96]. Each component of the vascular microenvironment influences the behavior and function of the others. So, while it is challenging to engineer systems that decouple one microenvironmental aspect from another, engineering 3D tissue constructs allow us to investigate how a change in one microenvironmental component influences another. Using the 3D hypoxic hydrogel system, it was found that hypoxia induces matrix metalloprotease-mediated hydrogel degradation required for endothelial progenitor clustering[96] and network formation[98]. Hypoxic levels and gradients greatly influence the mechanisms governing the functions within the vascular microenvironment. Engineering systems in the lab to mimic biologically relevant conditions permits further exploration and understanding of that environment to enhance vascular regeneration.

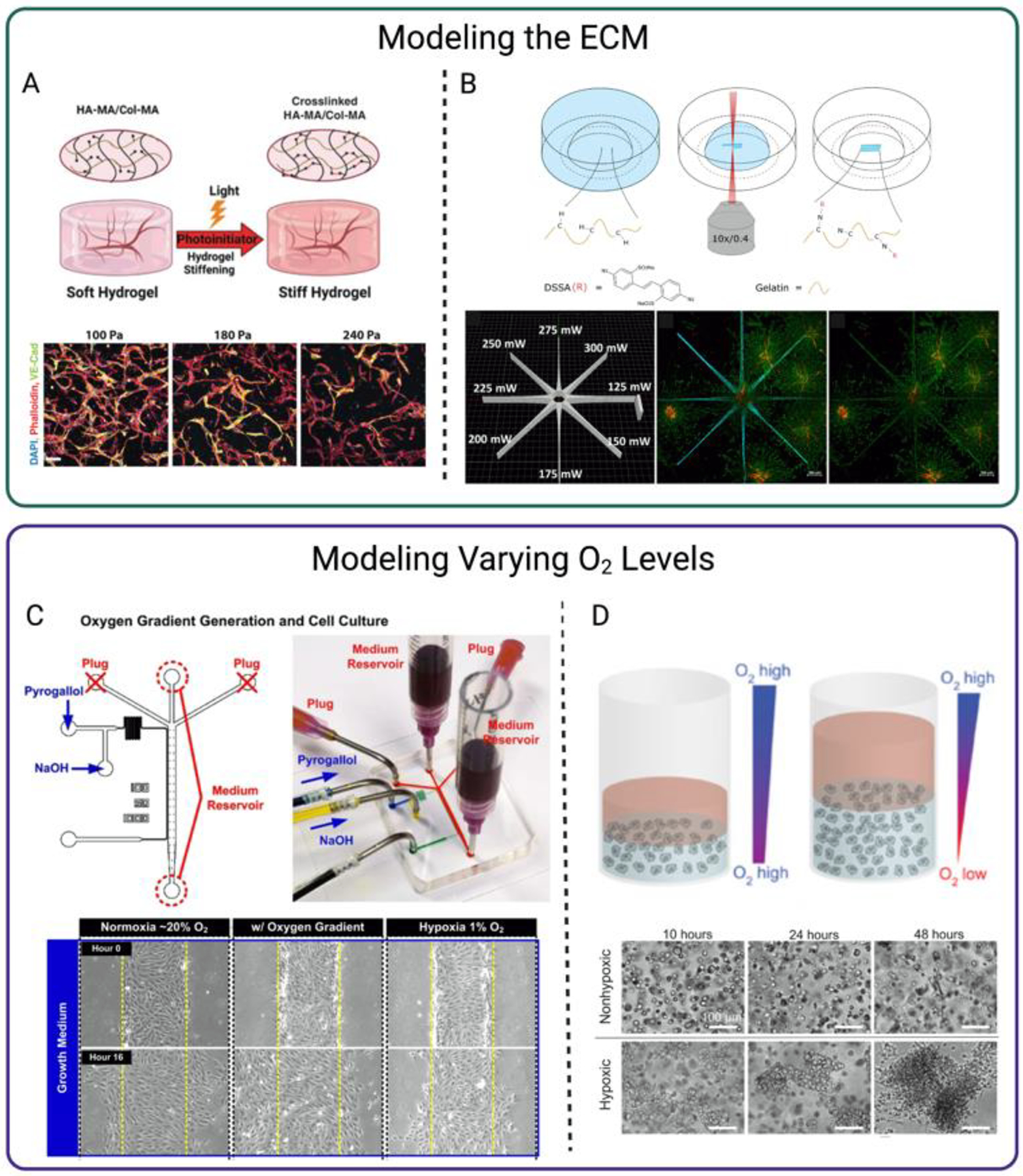

Concluding Remarks

Engineering approaches have enhanced our understanding of the vascular microenvironment’s roles in health and disease (Figure 3), yet there is much to consider moving forward (see Outstanding Questions). Current limitations include creating in vitro systems that support the inclusion of immune components and tissue-specific cells without conceding too much control over the microenvironment, thus further increasing the complexity of the systems. Increasing the complexity of in vitro systems may permit a better understanding of the microenvironment but compromise the translatability to the clinic with the loss of control over the overall system. Future research directions include creating tailored systems for studying specific diseases and sex-linked differences. Engineering tissue-specific vasculature to allow for the different functions of the vasculature in the brain, eye, heart, liver, and other organs within the body is an additional future direction.

Figure 3. Examples of ECM and Oxygen Level Modeling.

Schematic and data from A. Schnellmann et al. modeling ECM stiffening that lead to compromised microvascular phenotype. B. Sayer et al. modeling ECM patterning with high-resolution photographing, modulating endothelial sprout migration, C. Shih et al. demonstrating endothelial cell migration and proliferation under an oxygen gradient using microfluidics, and D. Blatchley et al. illustrating how low oxygen environments mediate endothelial cell cluster formation. Schematics and results were slightly modified for formatting and clarity. Schematics Created using Biorender.com.

Outstanding Questions.

How can ECM-mimicking biomaterials be used to create and investigate tissue-specific vascular constructs in vitro?

How can the complexity of vascular tissue constructs be increased in vitro in a controllable manner?

How can future therapeutics treating vascular diseases be more efficacious following an improved understanding of the disease mechanisms?

Highlights.

The vascular microenvironment is a complex environment of numerous components, with the extracellular matrix and oxygen playing critical roles in regulating cellular processes.

Advances in engineering and biomolecular approaches have allowed to develop research strategies to delineate the role of the microenvironment in vascular development, growth, and regeneration.

Biomaterials enable a deeper understanding of the biological mechanisms at play in health and disease states, and the enhanced knowledge can be used to develop therapeutic approaches to diseases.

Controlling and understanding the oxygen levels in diseased and healthy tissues can drive forward therapeutics by enhancing the knowledge of the mechanisms driving vascular cell behavior to support vascular regeneration.

Acknowledgments

Taylor Chavez is supported by 1T32GM144291 and is a 2022 recipient of the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program. Studies of hypoxia and ECM engineering in our lab are partially funded by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9550-20- 1-0356). The figures were created with Biorender.com.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.dela Paz NG and D’Amore PA, Arterial versus venous endothelial cells. Cell Tissue Res, 2009. 335(1): p. 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberts BJ, Alexander; Lewis Julian; Raff Martin; Roberts Keith; Walter Peter, Blood Vessels and Endothelial Cells, in Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th edition. 2002, Garland Science: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olmedo-Suárez M, et al. , Integrated On-Chip 3D Vascular Network Culture under Hypoxia. Micromachines (Basel), 2020. 11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam SF, et al. , Microfluidic device to attain high spatial and temporal control of oxygen. PLOS ONE, 2018. 13(12): p. e0209574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vazquez-Portalatin N, et al. , Physical, Biomechanical, and Optical Characterization of Collagen and Elastin Blend Hydrogels. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 2020. 48(12): p. 2924–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonmez UM, et al. , Endothelial cell polarization and orientation to flow in a novel microfluidic multimodal shear stress generator. Lab on a Chip, 2020. 20(23): p. 4373–4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnellmann R, et al. , Stiffening Matrix Induces Age-Mediated Microvascular Phenotype Through Increased Cell Contractility and Destabilization of Adherens Junctions. Adv Sci (Weinh), 2022: p. e2201483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karamanos NK, et al. , A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. The FEBS Journal, 2021. 288(24): p. 6850–6912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frantz C, Stewart KM, and Weaver VM, The extracellular matrix at a glance. Journal of Cell Science, 2010. 123(24): p. 4195–4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casale JC, Jonathan, Biochemistry, Glycosaminoglycans. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walimbe T and Panitch A, Proteoglycans in Biomedicine: Resurgence of an Underexploited Class of ECM Molecules. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 2020. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuivaniemi H and Tromp G, Type III collagen (COL3A1): Gene and protein structure, tissue distribution, and associated diseases. Gene, 2019. 707: p. 151–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard P and Macarak E, Localization of collagen types in regional segments of the fetal bovine aorta. Laboratory Investigation; a Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology, 1989. 61(5): p. 548–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bashey RI, Martinez-Hernandez A, and Jimenez SA, Isolation, characterization, and localization of cardiac collagen type VI. Associations with other extracellular matrix components. Circulation research, 1992. 70(5): p. 1006–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manon-Jensen T, Kjeld NG, and Karsdal MA, Collagen-mediated hemostasis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 2016. 14(3): p. 438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shekhonin BV, et al. , Distribution of type I, III, IV and V collagen in normal and atherosclerotic human arterial wall: immunomorphological characteristics. Collagen and related research, 1985. 5(4): p. 355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang K, Meng X, and Guo Z, Elastin Structure, Synthesis, Regulatory Mechanism and Relationship With Cardiovascular Diseases. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2021. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J and Shi GP, Vascular wall extracellular matrix proteins and vascular diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2014. 1842(11): p. 2106–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benito-Jardón M, et al. , The fibronectin synergy site re-enforces cell adhesion and mediates a crosstalk between integrin classes. eLife, 2017. 6: p. e22264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiang H-Y, et al. , Fibronectin Is an Important Regulator of Flow-Induced Vascular Remodeling. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 2009. 29(7): p. 1074–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hallmann R, et al. , The regulation of immune cell trafficking by the extracellular matrix. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2015. 36: p. 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagenseil JE and Mecham RP, Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol Rev, 2009. 89(3): p. 957–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruehle MA, et al. , Extracellular matrix compression temporally regulates microvascular angiogenesis. Science Advances, 2020. 6(34): p. eabb6351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu C, et al. , In vitro evaluation of vascular endothelial cell behaviors on biomimetic vascular basement membranes. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2019. 182: p. 110381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irons L, et al. , Switching behaviour in vascular smooth muscle cell-matrix adhesion during oscillatory loading. J Theor Biol, 2020. 502: p. 110387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, et al. , MMP-2 and MMP-9 contribute to the angiogenic effect produced by hypoxia/15-HETE in pulmonary endothelial cells. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 2018. 121: p. 36–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quintero-Fabián S, et al. , Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Angiogenesis and Cancer. Front Oncol, 2019. 9: p. 1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei Z, et al. , Hydrogel Network Dynamics Regulate Vascular Morphogenesis. Cell Stem Cell, 2020. 27(5): p. 798–812.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nie K, et al. , Enzyme-Crosslinked Electrospun Fibrous Gelatin Hydrogel for Potential Soft Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel), 2020. 12(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdul Sisak MA, Louis F, and Matsusaki M, In vitro fabrication and application of engineered vascular hydrogels. Polymer Journal, 2020. 52(8): p. 871–881. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngo MT and Harley BAC, Angiogenic biomaterials to promote therapeutic regeneration and investigate disease progression. Biomaterials, 2020. 255: p. 120207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu S, et al. , Histatin-1 loaded multifunctional, adhesive and conductive biomolecular hydrogel to treat diabetic wound. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2022. 209: p. 1020–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sayer S, et al. , Guiding cell migration in 3D with high-resolution photografting. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12(1): p. 8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J, et al. , Co-culture of human umbilical vein endothelial cells and human bone marrow stromal cells into a micro-cavitary gelatin-methacrylate hydrogel system to enhance angiogenesis. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2019. 102: p. 906–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kenar H, et al. , Microfibrous scaffolds from poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) blended with xeno-free collagen/hyaluronic acid for improvement of vascularization in tissue engineering applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 2019. 97: p. 31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren X, et al. , Growth Factor Engineering Strategies for Regenerative Medicine Applications. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2020. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ucar B, Yusufogullari S, and Humpel C, Collagen hydrogels loaded with fibroblast growth factor-2 as a bridge to repair brain vessels in organotypic brain slices. Experimental Brain Research, 2020. 238(11): p. 2521–2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen D, et al. , Injectable temperature-sensitive hydrogel with VEGF loaded microspheres for vascularization and bone regeneration of femoral head necrosis. Materials Letters, 2018. 229: p. 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Browne S, et al. , TGF-β1/CD105 signaling controls vascular network formation within growth factor sequestering hyaluronic acid hydrogels. PLOS ONE, 2018. 13(3): p. e0194679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He YJ, et al. , Cell-Laden Gradient Hydrogel Scaffolds for Neovascularization of Engineered Tissues. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2021. 10(7): p. 2001706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peters EB, et al. , Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogel Scaffolds Containing Cell-Adhesive and Protease-Sensitive Peptides Support Microvessel Formation by Endothelial Progenitor Cells. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering, 2016. 9(1): p. 38–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trujillo S, et al. , Engineered 3D hydrogels with full-length fibronectin that sequester and present growth factors. Biomaterials, 2020. 252: p. 120104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hielscher A, et al. , Fibronectin Deposition Participates in Extracellular Matrix Assembly and Vascular Morphogenesis. PLOS ONE, 2016. 11(1): p. e0147600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doolittle RF, Fibrinogen and fibrin. Annual review of biochemistry, 1984. 53(1): p. 195–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bayer IS, Advances in Fibrin-Based Materials in Wound Repair: A Review. Molecules, 2022. 27(14): p. 4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luo Y, Zhang T, and Lin X, 3D printed hydrogel scaffolds with macro pores and interconnected microchannel networks for tissue engineering vascularization. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2022. 430: p. 132926. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Y, et al. , 3D-bioprinted gradient-structured scaffold generates anisotropic cartilage with vascularization by pore-size-dependent activation of HIF1α/FAK signaling axis. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine, 2021. 37: p. 102426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gong T, et al. , A Dynamically Tunable, Bioinspired Micropatterned Surface Regulates Vascular Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells Growth at Vascularization. Small, 2016. 12(41): p. 5769–5778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinstlinger IS, et al. , Generation of model tissues with dendritic vascular networks via sacrificial laser-sintered carbohydrate templates. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 2020. 4(9): p. 916–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams C, et al. , The use of micropatterning to control smooth muscle myosin heavy chain expression and limit the response to transforming growth factor β1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biomaterials, 2011. 32(2): p. 410–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Putten C, et al. , Protein Micropatterning in 2.5D: An Approach to Investigate Cellular Responses in Multi-Cue Environments. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2021. 13(22): p. 25589–25598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dickinson LE, Moura ME, and Gerecht S, Guiding endothelial progenitor cell tube formation using patterned fibronectin surfaces. Soft Matter, 2010. 6(20): p. 5109–5119. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta P, Moses JC, and Mandal BB, Surface Patterning and Innate Physicochemical Attributes of Silk Films Concomitantly Govern Vascular Cell Dynamics. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering, 2019. 5(2): p. 933–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dicker KT, et al. , Spatial Patterning of Molecular Cues and Vascular Cells in Fully Integrated Hydrogel Channels via Interfacial Bioorthogonal Cross-Linking. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2019. 11(18): p. 16402–16411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin Q, et al. , Biomimetic human small muscular pulmonary arteries. Science Advances, 2020. 6(13): p. eaaz2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ogaki R, Alexander M, and Kingshott P, Chemical patterning in biointerface science. Materials Today, 2010. 13(4): p. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun W, et al. , Vascular cell responses to silicone surfaces grafted with heparin-like polymers: surface chemical composition vs. topographic patterning. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 2020. 8(39): p. 9151–9161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang G, et al. , Mechano-regulation of vascular network formation without branches in 3D bioprinted cell-laden hydrogel constructs. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2021. 118(10): p. 3787–3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Madl CM, Katz LM, and Heilshorn SC, Bio-Orthogonally Crosslinked, Engineered Protein Hydrogels with Tunable Mechanics and Biochemistry for Cell Encapsulation. Adv Funct Mater, 2016. 26(21): p. 3612–3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang W, et al. , Matrix stiffness regulates vascular integrity through focal adhesion kinase activity. The FASEB Journal, 2019. 33(1): p. 1199–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.VanderBurgh JA, et al. , Substrate stiffness heterogeneities disrupt endothelial barrier integrity in a micropillar model of heterogeneous vascular stiffening. Integrative Biology, 2018. 10(12): p. 734–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hartman CD, et al. , Vascular smooth muscle cell durotaxis depends on extracellular matrix composition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2016. 113(40): p. 11190–11195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim NY, et al. , Biophysical Induction of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Podosomes. PLOS ONE, 2015. 10(3): p. e0119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kingdom JC and Kaufmann P, Oxygen and placental vascular development. Adv Exp Med Biol, 1999. 474: p. 259–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carreau A, et al. , Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 2011. 15(6): p. 1239–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tao J, et al. , Targeting hypoxic tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 2021. 14(1): p. 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee S-J, et al. , Angiopoietin-2 exacerbates cardiac hypoxia and inflammation after myocardial infarction. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2018. 128(11): p. 5018–5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Horst B, et al. , Hypoxia-induced inhibin promotes tumor growth and vascular permeability in ovarian cancers. Communications Biology, 2022. 5(1): p. 536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shih H-J, et al. , Differential expression of hypoxia-inducible factors related to the invasiveness of epithelial ovarian cancer. Scientific Reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 22925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhao Q, et al. , PTPS Facilitates Compartmentalized LTBP1 S-Nitrosylation and Promotes Tumor Growth under Hypoxia. Molecular Cell, 2020. 77(1): p. 95–107.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.López-Cortés A, et al. , The close interaction between hypoxia-related proteins and metastasis in pancarcinomas. Scientific Reports, 2022. 12(1): p. 11100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ma B, et al. , Short‐term hypoxia promotes vascularization in co‐culture system consisting of primary human osteoblasts and outgrowth endothelial cells. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2020. 108(1): p. 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guan Y, et al. , Oxygen-release microspheres capable of releasing oxygen in response to environmental oxygen level to improve stem cell survival and tissue regeneration in ischemic hindlimbs. J Control Release, 2021. 331: p. 376–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schofield CJ and Ratcliffe PJ, Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 2004. 5(5): p. 343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hu CJ, et al. , Differential regulation of the transcriptional activities of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in stem cells. Mol Cell Biol, 2006. 26(9): p. 3514–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Semenza GL, HIF-1 and human disease: one highly involved factor. Genes & development, 2000. 14(16): p. 1983–1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Forsythe JA, et al. , Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia inducible factor 1. Molecular and cellular biology, 1996. 16(9): p. 4604–4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu Y, et al. , Hypoxia regulates vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in endothelial cells: identification of a 5′ enhancer. Circulation research, 1995. 77(3): p. 638–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hubbi ME and Semenza GL, Regulation of cell proliferation by hypoxia-inducible factors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2015. 309(12): p. C775–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao X, et al. , Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-α (HIF-1α) Induces Apoptosis of Human Uterosacral Ligament Fibroblasts Through the Death Receptor and Mitochondrial Pathways. Med Sci Monit, 2018. 24: p. 8722–8733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Greijer AE and van der Wall E, The role of hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) in hypoxia induced apoptosis. J Clin Pathol, 2004. 57(10): p. 1009–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lum JJ, et al. , The transcription factor HIF-1alpha plays a critical role in the growth factor-dependent regulation of both aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis. Genes Dev, 2007. 21(9): p. 1037–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rey S and Semenza GL, Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent mechanisms of vascularization and vascular remodelling. Cardiovasc Res, 2010. 86(2): p. 236–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sies H and Jones DP, Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2020. 21(7): p. 363–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Souvannakitti D, Peerapen P, and Thongboonkerd V, Hypobaric hypoxia down-regulated junctional protein complex: Implications to vascular leakage. Cell Adhesion & Migration, 2017. 11(4): p. 360–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Warnecke C, et al. , Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor pathway and stimulation of angiogenesis by application of prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors. The FASEB Journal, 2003. 17(9): p. 1186–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pavlacky J and Polak J, Technical Feasibility and Physiological Relevance of Hypoxic Cell Culture Models. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2020. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zirath H, et al. , Every Breath You Take: Non-invasive Real-Time Oxygen Biosensing in Two- and Three-Dimensional Microfluidic Cell Models. Frontiers in Physiology, 2018. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wagner BA, Venkataraman S, and Buettner GR, The rate of oxygen utilization by cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2011. 51(3): p. 700–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hsu H-H, et al. , Study 3D Endothelial Cell Network Formation under Various Oxygen Microenvironment and Hydrogel Composition Combinations Using Upside-Down Microfluidic Devices. Small, 2021. 17(15): p. 2006091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shih H-C, et al. , Microfluidic Collective Cell Migration Assay for Study of Endothelial Cell Proliferation and Migration under Combinations of Oxygen Gradients, Tensions, and Drug Treatments. Scientific Reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 8234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoshino D and Funamoto K, Oxygen-dependent contraction and degradation of the extracellular matrix mediated by interaction between tumor and endothelial cells. AIP Advances, 2019. 9(4): p. 045215. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sticker D, et al. , Microfluidic Migration and Wound Healing Assay Based on Mechanically Induced Injuries of Defined and Highly Reproducible Areas. Analytical Chemistry, 2017. 89(4): p. 2326–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tefft JB, Chen CS, and Eyckmans J, Reconstituting the dynamics of endothelial cells and fibroblasts in wound closure. APL Bioengineering, 2021. 5(1): p. 016102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Blatchley MR, et al. , Discretizing Three-Dimensional Oxygen Gradients to Modulate and Investigate Cellular Processes. Adv Sci (Weinh), 2021. 8(14): p. e2100190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Blatchley MR, et al. , Hypoxia and matrix viscoelasticity sequentially regulate endothelial progenitor cluster-based vasculogenesis. Sci Adv, 2019. 5(3): p. eaau7518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cho H, et al. , iPSC-derived endothelial cell response to hypoxia via SDF1a/CXCR4 axis facilitates incorporation to revascularize ischemic retina. JCI Insight, 2020. 5(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Park KM and Gerecht S, Hypoxia-inducible hydrogels. Nature Communications, 2014. 5(1): p. 4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]