Abstract

Background:

Low back pain is a leading cause of disability and is frequently associated with whole-body vibration exposure in industrial workers and military personnel. While the pathophysiological mechanisms by which whole-body vibration causes low back pain have been studied in vivo, there is little data to inform low back pain diagnosis. Using a rat model of repetitive whole-body vibration followed by recovery, our objective was to determine the effects of vibration frequency on hind paw withdrawal threshold, circulating nerve growth factor concentration, and intervertebral disc degeneration.

Methods:

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were vibrated for 30 minutes at an 8 Hz or 11 Hz frequency every other day for two weeks and then recovered (no vibration) for one week. Von Frey was used to determine hind paw mechanical sensitivity every two days. Serum nerve growth factor concentration was determined every four days. At the three-week endpoint, intervertebral discs were graded histologically for degeneration.

Findings:

The nerve growth factor concentration increased threefold in the 8 Hz group and twofold in the 11 Hz group. The nerve growth factor concentration did not return to baseline by the end of the one-week recovery period for the 8 Hz group. Nerve growth factor serum concentration did not coincide with intervertebral disc degeneration, as no differences in degeneration were observed among groups. Mechanical sensitivity generally decreased over time for all groups, suggesting a habituation (desensitization) effect.

Interpretation:

This study demonstrates the potential of nerve growth factor as a diagnostic biomarker for low back pain due to whole-body vibration.

Keywords: Whole-body vibration, pain, intervertebral disc, nerve growth factor, spine

1. Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the second leading cause of disability globally (Izzo et al., 2015), with a mean prevalence between 1.4–15.6% in North America and western Europe (Fatoye et al., 2019). Epidemiological evidence suggests a connection between whole-body vibration (WBV) exposure and LBP among occupational (Bovenzi et al., 2017; Burström et al., 2015; Milosavljevic et al., 2012) and military populations (Kollock et al., 2015, 2016). Among Active Duty personnel in the United States Armed Forces, 34.7% were diagnosed with musculoskeletal LBP for the first time in 2017–2018 (Gun et al., 2022). Helicopter pilots are at increased risk for back muscle fatigue (Kollock et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022), LBP (Yang et al., 2022), and degenerative changes to the spine (Byeon et al., 2013; Knox et al., 2018; Kollock et al., 2015). Other studies have shown an increased risk of LBP is associated with increased cumulative vibration exposure for heavy machine operators (Bovenzi and Schust, 2021).

Injury from WBV is most likely to occur at the resonant frequency, which is 4–6 Hz for humans (Baig et al., 2014; Pope et al., 1998), and 8–9 Hz for rats (Zeeman et al., 2016). WBV has been shown to increase degeneration of the intervertebral disc (IVD) from both in vivo and ex vivo/in vitro models. Following four or eight weeks of repeated WBV in mice, there was a reduction in the disc height index, more significant degeneration, and greater expression of genes coding for matrix degradation enzymes in the IVD (McCann et al., 2017, 2015). Ex vivo cyclic compression of porcine spinal motion segments also resulted in reduced IVD height (Barrett et al., 2016). The vibration of the whole disc reduced cell viability in the annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus (Illien-Junger et al., 2010), and vibration of isolated nucleus pulposus cells decreased aggrecan, collagen type III, and matrix metalloproteinase 3 gene expression (Yamazaki et al., 2002). A comprehensive review of these and similar studies can be found in (Patterson et al., 2021).

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is a neurotrophin that mediates neuronal growth and death and is associated with increased pain (Denk et al., 2017; Khan and Smith, 2015; Minnone et al., 2017). Expression of the NGF gene promotes IVD innervation (Zhang et al., 2021), is elevated in the herniated IVD (Aoki et al., 2014), and is thought to play a significant role in pain originating from the degenerated IVD (Ohtori et al., 2015). NGF gene and protein expression have been shown to increase in the IVD following painful WBV exposure in rats, as determined using von Frey (Kartha et al., 2014). Finally, there is an increasing interest in the use of serum biomarkers to improve LBP diagnosis (Khan et al., 2017; van den Berg et al., 2018), and based on its role in IVD degeneration and LBP, NGF may be a good candidate for such a biomarker.

No prior work has examined the potential utility of serum NGF as a diagnostic biomarker for LBP, despite its role in LBP pathology. Most in vivo studies of LBP from WBV focus on elucidating the pathophysiology thereof, with little emphasis on improving LBP diagnosis. In light of this fact, the objective of this study was to the effect of repeated WBV at 8 Hz or 11 Hz on serum NGF concentration, IVD degeneration, and mechanical sensitivity using a rat model. The resonant frequency of the rat spine was found to be 8–9 Hz, which resulted in greater mechanical sensitivity than WBV at other frequencies (Zeeman et al., 2015, 2016). Further, the resonant frequency is the frequency at which the greatest extent of injury is expected to occur (Zeeman et al., 2016, 2015). Therefore, we hypothesized that NGF concentration would increase over time in the vibration groups, 8 Hz would result in greater pain-like behavior and NGF response than 11 Hz or Control, IVD degeneration would be greater at 8 Hz than Control or 11 Hz, and pain-like behavior and NGF concentration would not recover within one week after WBV ceased.

2. Methods

2.1. Animal Care and Experimental Design

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Mississippi State University, protocol 17–715. Thirty-six outbred male Sprague-Dawley rats, 66–70 days old and weighing 285.0 ± 1.1 g, were used (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN). The rats were housed in an AAALAC-accredited animal research facility, with three animals per cage, a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and access to food and water ad libitum. Rats from the same group were housed together. Cages were alternated by group on the cage rack to minimize any effect of cage location. Housing conditions were checked daily by a veterinary technician. Prior to the beginning of the studies, rats were acclimated to the vibrations chamber and von Frey enclosure for ten minutes per day for five days. Rats were randomly assigned to a Control group (n = 12), an 8 Hz frequency group (n = 12), or an 11 Hz frequency group (n = 12). The Control group underwent identical procedures, but the vibration device was not turned on. Animals were weighed every two days to monitor potential weight loss. Humane endpoints that were considered for removal or euthanasia were loss of 10% or 15% of starting body weight (respectively), unconsciousness, lethargy, diarrhea, and anorexia for multiple days. However, these effects were not anticipated as results from a previous pilot experiment established the safety of the procedures (data not shown). At the conclusion of the study, animals were euthanized via carbon dioxide asphyxiation. A timeline of procedures can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental outcome measures and timeline.

| Day | Whole-Body Vibration | Von Frey | Blood Draws | Euthanasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | X | X | ||

| 0 | X | X | ||

| 2 | X | X | ||

| 4 | X | X | X | |

| 6 | X | X | ||

| 8 | X | X | X | |

| 10 | X | X | ||

| 12 | X | X | X | |

| 14 | X | |||

| 16 | X | X | ||

| 18 | X | |||

| 20 | X | X | ||

| 21/22 | X |

2.2. Vibration Exposure

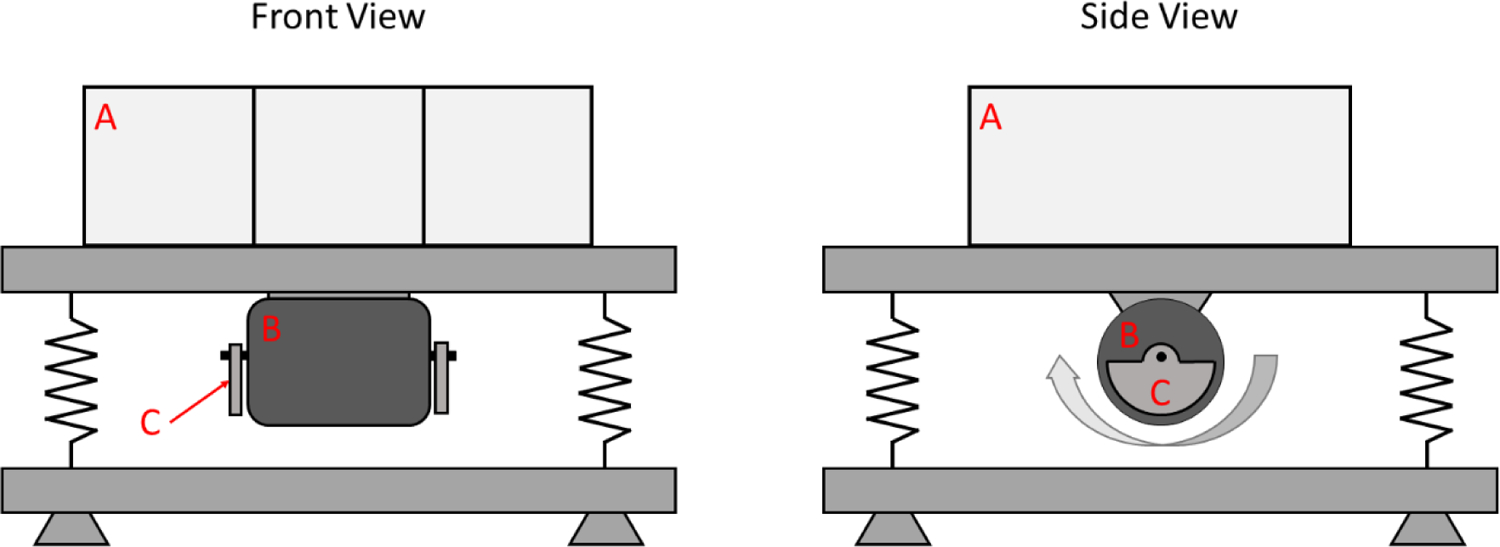

The vibration platform was composed of a commercially available oscillatory vibration exercise plate (model VT003F; Vibration Therapeutic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with an eccentric mass motor located between two plates separated by springs. The device was modified so that the motor speed could be tuned with a separate DC motor controller (model KBWM-120; KB Electronics, Inc., Coral Springs, FL, USA). The eccentric mass could be altered by adding or removing metal plates from the motor. Acceleration magnitude was measured using a triple-axis accelerometer (model 2809; Adafruit, New York, NY, USA). A closed, three-part polycarbonate chamber was attached to the top plate by high-strength hook-and-loop fasteners (Fig. 1). The vibration acceleration was in the fore-aft direction, along the long axis of the rat spine. The peak-to-peak fore-aft acceleration magnitude was 0.292 ± 0.003 g and the frequency was 8.784 ± 0.022 Hz for the 8 Hz group. These values were 0.450 ± 0.006 g and 11.216 ± 0.033 Hz for the 11 Hz group.

Fig. 1.

Front and side views of the vibration device and rat enclosure. A: Sectioned polycarbonate chamber for rats. B: Motor for generating vibrations. C: Eccentric mass on the motor. The curved arrow indicates the rotational direction of the motor.

All animals were acclimated to the vibration device (with no vibration) for 10 minutes per day for five days immediately prior to the start of the study. Conscious rats were exposed to WBV for 30 minutes per day, every other day for 14 days, followed by seven days of recovery. Rats were monitored during vibrations for signs of distress that would require removal from the vibration device using the rat grimace scale (Turner et al., 2019). The experimental groups were alternated throughout the day to minimize any effect of time of day (e.g., Control at 8:30 AM, 8 Hz at 9:00 AM, 11 Hz at 9:30 AM, Control at 10:00 AM, etc.).

2.3. Mechanical Sensitivity

Immediately following vibrations, or at the same time of day during the recovery period, rats were assessed for mechanical allodynia by measuring the withdrawal threshold of the hind paws using a von Frey anesthesiometer (model I-2392; IITC Life Science Inc., Woodland Hills, CA, USA) (Deuis et al., 2017). Each rat was placed into a separate acrylic chamber on a table with a wire mesh surface. Once the rat settled in the chamber (i.e., stopped walking about and rearing), nylon filaments of increasing stiffness were applied to the bottom of one hind paw until a withdrawal reflex was observed. If the rat reared or walked immediately after the filament application, the measurement was considered a false positive (Deuis et al., 2017). Immediately following observation of hind paw withdrawal, the filament with the next lowest stiffness was applied to confirm that the minimum force to prompt a withdrawal response was found. The procedure was repeated for the other paw, and the reaction in grams-force of both hind paws was averaged for each rat. Three rats at a time were analyzed. Mechanical sensitivity was determined every other day for the entire study.

2.4. Serum Analysis of Nerve Growth Factor

Following the determination of hind paw mechanical sensitivity, rats were restrained in a plastic cone, and blood was taken from the lateral tail vein and collected into additive-free tubes (model 365963; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Personnel were trained to draw blood on a dummy rat prior to the experiment or had previous experience with the procedure. After collection, blood samples were allowed to clot at room temperature for 40 minutes before being placed on ice until further processing. The blood was centrifuged at 2,000g for 15 minutes, and the serum was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until analysis. The serum concentration of NGF was determined using a commercially available double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, catalog no. MBS2701224; MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA). Blood was collected the day before vibration and every four days thereafter.

2.5. Histological Analysis of Intervertebral Disc

Immediately following euthanasia, the lumbar spines (three spines [n = 3] per group, two IVDs per spine averaged) were excised and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for two weeks at 2–8 °C, then decalcified in Kristensen’s solution at 22–25 °C for one day. The spines were then routinely processed, embedded in paraffin, cut at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Scoring parameters were adapted from a mouse IVD scoring system by Tam et al., 2018 (Tam et al., 2018). The adapted scoring system assessed nucleus pulposus (NP) structure, NP clefts/fissures, annulus fibrosus (AF) structure, and the AF-NP boundary. The AF clefts/fissures as defined in the original scoring system were not scored in this modified scoring system, as there was a mild artifact within the tissue sections that precluded evaluation. Therefore, each IVD had a total potential score of 12 points: NP structure (4 points), NP clefts/fissures (2 points), AF structure (4 points), and AF-NP boundary (2 points). IVD were imaged at 20X. IVD images were blinded and independently scored by two individuals (one boarded veterinary pathologist and one second-year veterinary pathology resident) who had reviewed the scoring system. Scores for each parameter were averaged between the two observers and are reported both as a summation of scores for all four parameters and separately for each parameter.

2.6. Statistics

The sample size was determined a priori assuming a Cohen’s effect size of 0.8, 90% power to detect a difference, and 99% significance level. NGF serum concentration was used as the basis of power analysis, as its utility as a biomarker for LBP was the main focus of this study. The total sample size required would be n = 11 for three groups and five measurements over time of NGF serum concentration; this value was increased to n = 12 to account for potential adverse events necessitating the removal of animals from the study.

For NGF serum concentration and withdrawal threshold, a repeated-measures mixed-effects model was used to compare groups, with simulation-based multiple comparisons following Edwards and Berry, 1987 (Edwards and Berry, 1987). Timepoint was treated as a discrete factor. Assumptions of linearity, normality, and homoscedasticity were assessed with residual plots. Withdrawal threshold and NGF concentration analyses were carried out using SAS V9.4. Histological scores were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons in GraphPad Prism V9.0.0. All data are shown as average + 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

No adverse events occurred, and all animals survived until the end of the experiment. No animals experienced weight loss during the study or were excluded from analyses.

3.1. Mechanical Sensitivity

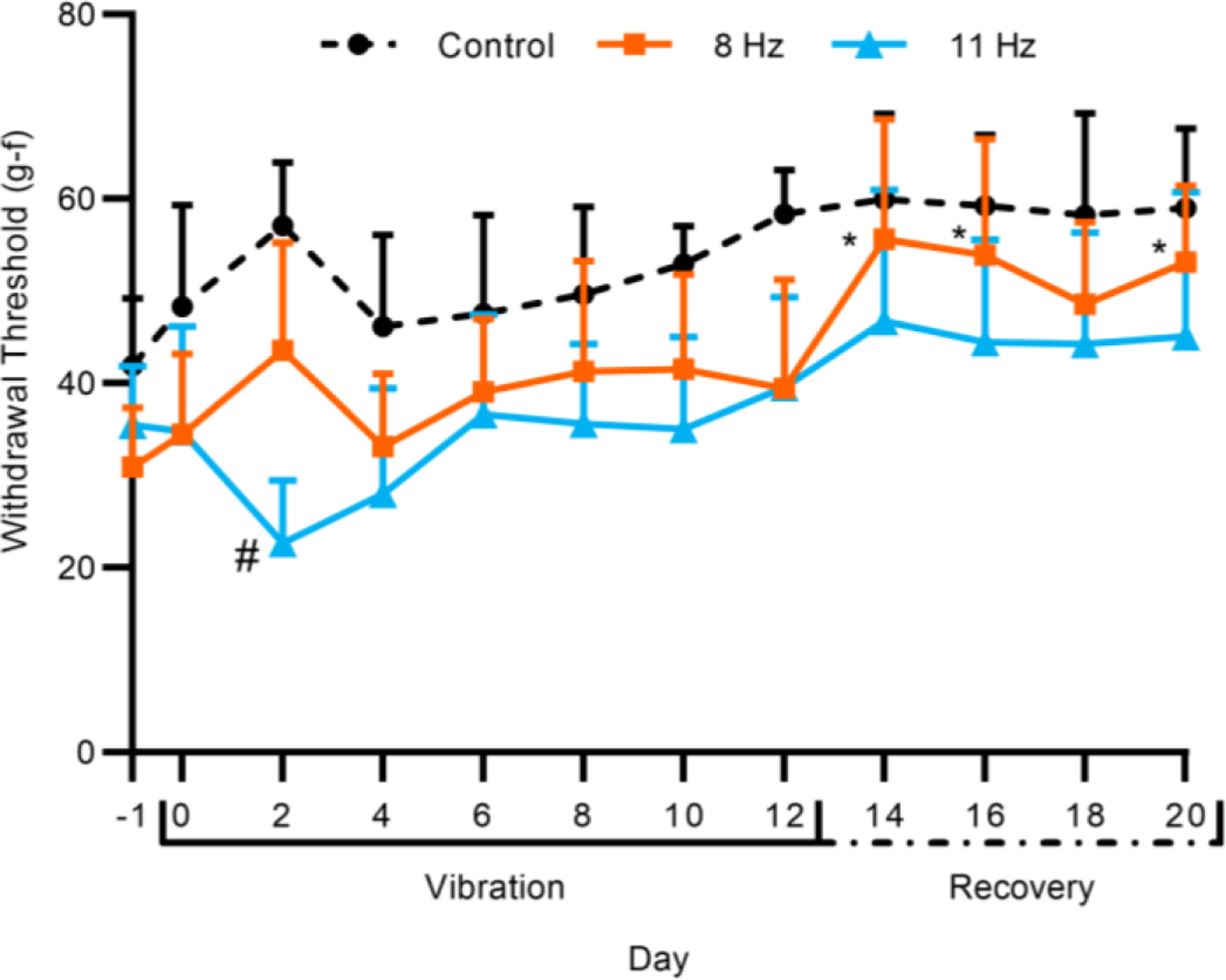

The mechanical sensitivity was determined by the hind paw withdrawal threshold every other day, and comparisons were made to day −1 for each group and between groups on each day. A decrease in the withdrawal threshold corresponds with an increase in mechanical sensitivity. The withdrawal threshold of the 8 Hz group increased from day −1 on days 14, 16, and 20 (P<0.05) (Fig. 2). The 8 Hz group did not differ from the Control (non-vibrated) group on any day. For the 11 Hz group, the withdrawal threshold was lower than Control only on day 2 (P<0.05).

Fig. 2.

Hind paw withdrawal threshold for Control, 8 Hz, and 11 Hz groups over the vibration and recovery periods. Error bars indicate 95% confidience interval. Statistical analysis was performed using a linear mixed-effects model. (n = 12; *P<0.05, compared to baseline; #P<0.05, compared to Control)

3.2. Serum Analysis of Nerve Growth Factor

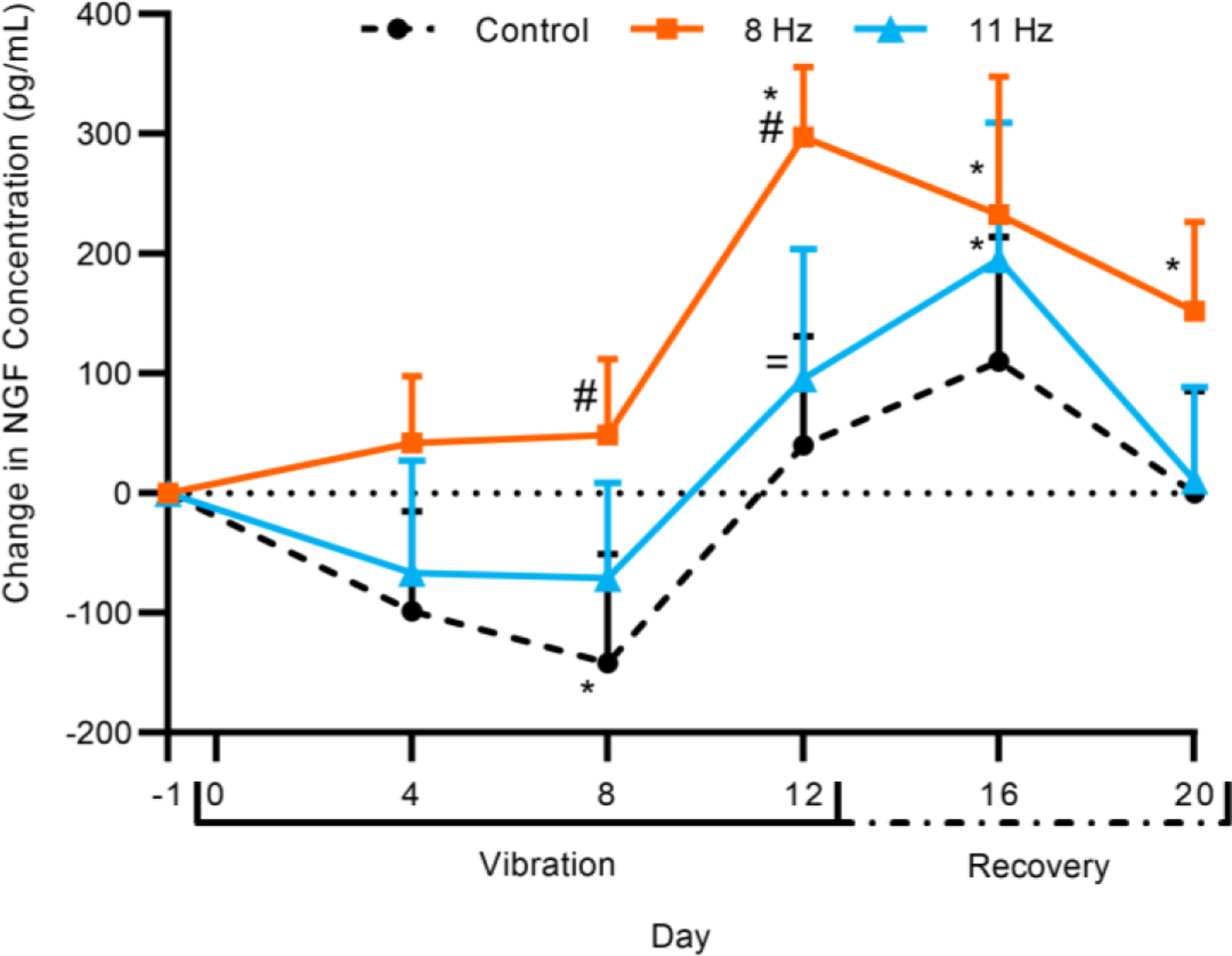

The change (from pre-vibration level) in NGF concentration in serum of the 8 Hz group was greater than that of the Control group on days 8 and 12 (P<0.05) (Fig. 3). The Control group NGF serum concentration decreased from baseline on day 8 (P<0.05). The concentration change in the 8 Hz group was greater than baseline on days 12, 16, and 20, while the 11 Hz group was greater than baseline on day 16 only (P<0.05). The NGF concentration in the 11 Hz group recovered to baseline by day 20. The 11 Hz group did not differ from the Control group on any day and was less than the 8 Hz group on day 12 (P<0.05). Further, the NGF concentration change peaked in the 8 Hz group on day 12 but did not peak in the 11 Hz group until day 16. The mixed-effects model showed that there was a statistically significant interaction between the “day” and “group” factors (P<0.05).

Fig. 3.

Change in nerve growth factor (NGF) serum concentration (pg/mL) for Control, 8 Hz, and 11 Hz groups over the vibration and recovery periods. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval. Statistical analysis was performed using a linear mixed-effects model. (n = 8–12; *P<0.05, compared to baseline; #P<0.05, compared to Control; =P<0.05, compared to 8 Hz)

3.3. Histological Analysis of Intervertebral Disc

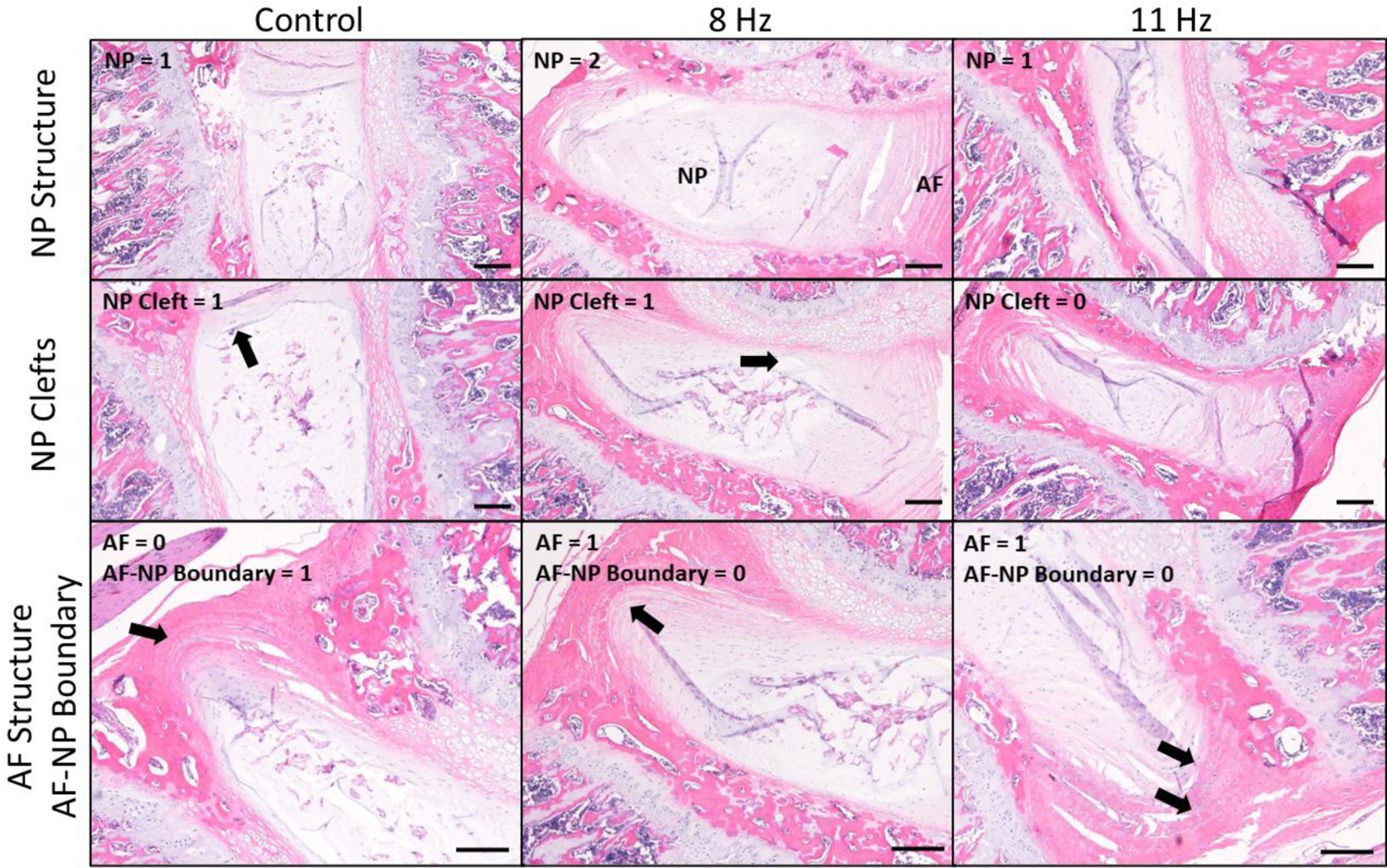

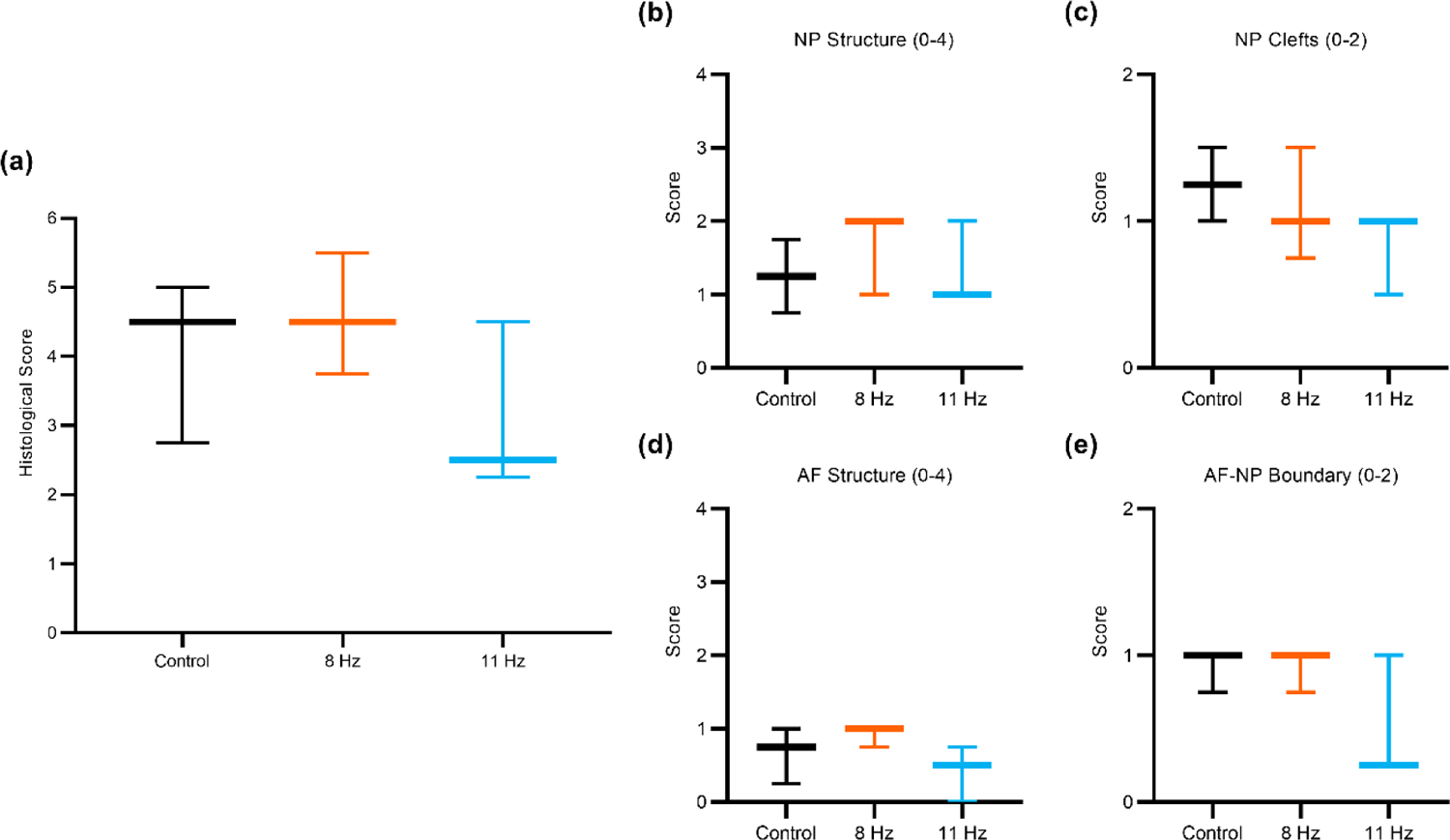

The extent of IVD degeneration observed using the modified histological scoring system was similar among the three groups (Fig. 4). For the NP structure, discs had a single mass of NP cells with little segregation (score 0), cell cluster formation with loss of <50% of cells (score 1), or cell cluster formation with >50% cell loss (score 2). For the NP cleft/fissure, discs had no clefts (score 0), mild clefts with the length of the cleft <50% of the NP compartment (score 1), or severe clefts with the length of the longest cleft >50% of the NP compartment (score 2). For the AF structure, discs had a concentric lamellar structure (score 0) or more serpentine lamellae with rounding of the cells lining the lamellae (score 1). For the AF-NP boundary, discs had a clearly distinguishable boundary (score 0) or discontinuity of the boundary with or without round chondrocyte-like cells (score 1). The total disc degeneration score was not different between groups (Fig. 5a). The scores for each parameter of IVD degeneration (NP structure, NP clefts/fissures, AF structure, and AF-NP boundary) did not differ between groups (Fig. 5b–e).

Fig. 4.

Representative histological images of intervertebral discs (IVDs). The extent of IVD degeneration observed using the modified histological scoring system was similar among the three groups. Arrows indicate NP clefts (second row, left and middle), serpentine lamellae of AF (third row, middle and right), and discontinuity of AF-NP boundary (third row, left). H&E, bar = 200 μm. NP = nucleus pulposus; AF = annulus fibrosus.

Fig. 5.

Boxplots of the IVD histological scoring parameters. (a) Summation of histological scores for all four IVD scoring parameters. Histological scores for each parameter: (b) NP structure, (c) NP clefts/fissures, (d) AF structure, and (e) AF-NP boundary. Error bars indicate the 10th-90th percentiles. No differences were noted for the total average score or any individual parameter. (n = 3)

4. Discussion

In this study, the effects of repeated WBV at 8 Hz or 11 Hz on hind paw mechanical sensitivity, serum NGF, and IVDD were assessed in a rat model. As 8–9 Hz is the resonant frequency of the unconscious rat’s spine (Zeeman et al., 2016, 2015), it was hypothesized that 8 Hz would result in more significant pain-like behavior and an increase in NGF serum concentration than 11 Hz, which is outside the resonant frequency range. Indeed, the concentration of NGF in the 8 Hz group increased more after two weeks of WBV exposure than in the 11 Hz group. The mechanical sensitivity results from von Frey testing, however, were inconclusive in determining nociceptive response. It was expected that WBV at 8 Hz would result in greater IVD degeneration than at 11 Hz, but no differences were observed among groups. Hence, a change in the concentration of NGF in the serum did not result in IVDD within the timeframe of the present study.

Our choice of 8 Hz for the vibrational load frequency was based on prior evidence identifying 8 Hz as the resonant frequency of the (unconscious) rat spine (Zeeman et al., 2016). In that study, a decrease in withdrawal threshold (i.e., increase in pain-like behavior) from a single or repeated exposure to vibration at resonance was observed using von Frey (Holsgrove et al., 2020; Zeeman et al., 2016). In contrast, our von Frey mechanical sensitivity results showed an increase in sensitivity only on day 3 for the 11 Hz group, and no increase in sensitivity for the 8 Hz group on any day. This difference could be attributed to the rodents being unconscious in the prior work (Zeeman et al., 2015, 2016), while the present study used conscious rats. Spinal muscle activity increases to stabilize the spine during vibration exposure (Dong and Guo, 2017), but this response is absent in anesthetized individuals. The difference in spine resonant frequencies between unconscious and conscious rats due to changes in muscle stiffness needs further investigation, as the utility of comparing the current results to others’ findings with unconscious rats is limited. Nonetheless, modeling LBP from WBV using conscious (as opposed to anesthetized) animals is necessarily more clinically relevant. The Control group differed slightly (generally increasing) over time during the vibration period but was constant during the recovery period, suggesting habituation (i.e., desensitization) to the von Frey procedure over time (Fig. 2). The 8 Hz group withdrawal threshold increased following cessation of WBV starting on day 14 but did not differ from Control on any day.

Previous work showed that NGF protein and gene expression was increased in the IVD following vibration exposure (Kartha et al., 2014). The concentration of NGF in serum following WBV has not been reported previously. In this study, the concentration of NGF increased in the serum after two weeks of WBV exposure, more so in the 8 Hz group than the 11 Hz group, though the groups did not differ from each other. Like other neurotrophic factors, NGF has a short half-life and is cleared from the plasma within one day following sustained delivery (Tria et al., 1994). Interestingly, rats that received five days of sustained, systemic delivery of NGF had undetectable NGF concentration in the plasma, yet experienced continued hind paw mechanical sensitivity (Eskander et al., 2015). From this data, the 8 Hz frequency evoked an earlier, longer-lasting response to WBV than the 11 Hz frequency, suggesting that the two frequencies invoke different time-dependent responses to WBV. Because local NGF concentrations were not measured in the IVD or other tissues, and NGF has both neurotrophic and apoptotic functions in the body (Denk et al., 2017; Ioannou and Fahnestock, 2017), further study is warranted to determine the potential pathways involved. Of particular interest are the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) and tyrosine kinase receptor A, whose signaling with neurotrophins impacts afferent nerve survival and growth (Bradshaw et al., 2015; Meeker and Williams, 2015).

NGF concentration change peaked on the last day of WBV (day 12) for the 8 Hz group, and on the first time point in the recovery phase (day 16) for the 11 Hz and Control groups, so it is unclear if NGF would have continued to increase, level off, or even decrease if WBV exposure had continued. Compared to levels produced from resonant (8–9 Hz) frequency, at alternative frequencies such as 11 Hz, NGF may be produced at lower levels and would thus be expected to clear more rapidly during removal of the WBV stimulus. Regarding recovery, NGF concentration returned to baseline by the end of the recovery period in the 11 Hz group but not in the 8 Hz group, indicating that one week of recovery following two weeks of WBV at 8 Hz was not sufficient for NGF serum concentration to return to baseline values. If the recovery period had been extended past the one-week endpoint, recovery in the 8 Hz group may have been detectable.

Previous work examining the effect of vibration on peripheral nerves has used frequencies over 30 Hz, which is relevant to power tool usage and hand-arm vibration syndrome. In rat tail and hind limb models of hand-arm vibration syndrome, a consistent finding is that vibration disrupts the myelin sheath of axons, including myelin thickening and disorganization (Davis et al., 2014; Loffredo et al., 2009; Matloub et al., 2005). However, it is unclear how these findings would translate to the lower frequencies used in the present study.

Neither WBV group had significantly greater disc degeneration scores than the Control group, though the AF-NP boundary and AF structure scores were slightly lower in the 11 Hz group compared to Control or 8 Hz (Fig. 5). A low sample size of only three rats per group and two discs per rat (n = 3) were analyzed, which reduced statistical power for this outcome measure. Previous ex vivo studies of the IVD under cyclic loading conditions revealed AF delamination (Wade et al., 2016), reduced NP cell viability (Chan et al., 2013; Illien-Junger et al., 2010), and reduced glycosaminoglycan content compared to controls (LePage et al., 2020). Interestingly, the scores for NP clefts and AF-NP boundary were both slightly lower in the 11 Hz compared to Control and 8 Hz, but the 8 Hz group was similar or identical to the Control group. In previous WBV experiments in mice, NP clefts were not noted upon IVD degeneration scoring, but a distinct AF-NP boundary was lost (McCann et al., 2017, 2015). Unfortunately, processing artifacts prevented scoring of the AF clefts, which may have provided additional information regarding degenerative changes in the IVD. Further study is needed to assess frequency-dependent IVD degeneration with additional histological outcome measures such as aggrecan loss and innervation.

Notably, this study performed WBV over a relatively short period of two weeks and only considered a recovery period of one week. Previous work found increased NGF gene expression in the IVD following daily 15 Hz WBV for seven days (Kartha et al., 2014), but longer WBV exposure and/or extended recovery time may be necessary to induce microstructural changes associated with IVD degeneration. The vibration device was unable to maintain the same acceleration magnitude at different frequencies, adding a confounding factor to determining the effect of frequency on recovery from WBV. The von Frey method did not provide a conclusive determination of nociceptive response in this study because the Control group also exhibited an increase in withdrawal threshold over time. Another measure of pain-like behavior, such as the tail-flick test, may provide a better measure of nociception (Deuis et al., 2017). Further, using a non-evoked measure such as the rat grimace scale and observation of cage behavior would coincide more with the disabling aspects of LBP in humans (Turner et al., 2019). NGF concentration did not peak until the last day of WBV, so it is not clear if NGF would continue to increase past this point, level off, or even decrease if WBV exposure continued. NGF concentration also did not recover in the 8 Hz group by the end of the study, so the time for NGF to recover to baseline after 8 Hz of WBV could not be determined. Additionally, the use of a quadrupedal species raises the question of translation of these findings to humans, as one would assume that there would be greater force on the spine in bipeds than in quadrupeds. However, spinal ligaments and muscles exert additional forces on the IVDs of quadrupeds for stability and posture control which results in similar intradiscal pressure between rodents and humans (Alini et al., 2008). Finally, only young male animals were used given that approximately 83% of Active Duty military personnel are men and 66% are 30 years of age or younger (D.O.D., 2020). Given that the number of women in Active Duty is increasing (D.O.D., 2020), future work should include female animals to examine sex differences in pain-like behavior from WBV (D.O.D., 2020).

The objective of this study was to determine the effect of repeated WBV at 8 Hz or 11 Hz on serum NGF concentration, IVDD, and mechanical sensitivity using a rat model. NGF concentration increased more in the 8 Hz group compared to the 11 Hz group, coinciding with previous results demonstrating resonance at 8 Hz (Zeeman et al., 2015). Notably, NGF concentration did not decrease to baseline values in the 8 Hz group after one week of recovery, while NGF values returned to baseline in the 11 Hz group. However, increased NGF concentration in the serum did not coincide with IVDD or a decrease in hind paw withdrawal threshold, as neither of these were altered by WBV. These findings indicate the potential diagnostic utility of NGF and the therapeutic potential of anti-NGF-based treatments for LBP. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine NGF serum concentration following WBV exposure. Because LBP continues to be a major concern in industrial and military populations, continued study of its mechanisms is imperative.

Highlights.

Rats were subjected to repeated whole-body vibration at 8 Hz or 11 Hz.

Serum nerve growth factor concentration increased more following vibration at 8 Hz.

Increased nerve growth factor did not result in intervertebral disc degeneration.

Nerve growth factor could be used to diagnose low back pain from whole-body vibration.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Center for Advanced Vehicular Systems for financial support, and the College of Veterinary Medicine at Mississippi State University for providing animal housing and care. The authors thank Michael Murphy, Kali Sebastian, Anna Marie Clay, Ashley Varley, Alex Smith, Matthew Register, Andy Li, and Ryan Yingling for assisting with the animal study. The authors thank Filip To for providing technical support in the vibration device design.

Funding

This material is based upon work performed under US Army ERDC Contract No. W912HZ-17-C-0021. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s). Public release; distribution unlimited. F. Patterson received additional funding from The Graduate School and The Office of the Provost and the Executive Vice President at Mississippi State University. L. Priddy is supported in part by NIH grant P20GM103646.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- D.O.D., U.S., 2020. 2020 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community.

- Alini M, Eisenstein SM, Ito K, Little C, Kettler AA, Masuda K, Melrose J, Ralphs J, Stokes I, Wilke HJ, 2008. European Spine Journal 17, 2–19. 10.1007/s00586-007-0414-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki Y, Nakajima A, Ohtori S, Takahashi H, Watanabe F, Sonobe M, Terajima F, Saito M, Takahashi K, Toyone T, Watanabe A, Nakajima T, Takazawa M, Nakagawa K, 2014. Increase of nerve growth factor levels in the human herniated intervertebral disc: can annular rupture trigger discogenic back pain? Arthritis Research and Therapy 16, R159. 10.1186/ar4674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig HA, Dorman DB, Bulka BA, Shivers BL, Chancey VC, Winkelstein BA, 2014. Characterization of the frequency and muscle responses of the lumbar and thoracic spines of seated volunteers during sinusoidal whole body vibration. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 136, 1–7. 10.1115/1.4027998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JM, Gooyers CE, Karakolis T, Callaghan JP, 2016. The impact of posture on the mechanical properties of a functional spinal unit during cyclic compressive loading. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 138, 081007. 10.1115/1.4033916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovenzi M, Schust M, 2021. A prospective cohort study of low-back outcomes and alternative measures of cumulative external and internal vibration load on the lumbar spine of professional drivers. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 47, 277–286. 10.5271/sjweh.3947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovenzi M, Schust M, Mauro M, 2017. An overview of low back pain and occupational exposures to whole-body vibration and mechanical shocks. Medicina del Lavoro 108, 419–433. 10.23749/mdl.v108i6.6639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw RA, Pundavela J, Biarc J, Chalkley RJ, Burlingame AL, Hondermarck H, 2015. NGF and ProNGF: Regulation of neuronal and neoplastic responses through receptor signaling. Advances in Biological Regulation 58, 16–27. 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burström L, Nilsson T, Wahlström J, 2015. Whole-body vibration and the risk of low back pain and sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 88, 403–418. 10.1007/s00420-014-0971-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon JH, Kim JW, Jeong HJ, Sim YJ, Kim DK, Choi JK, Im HJ, Kim GC, 2013. Degenerative changes of spine in helicopter pilots. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine 37, 706–712. 10.5535/arm.2013.37.5.706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SCW, Walser J, Käppeli P, Shamsollahi MJ, Ferguson SJ, Gantenbein-Ritter B, 2013. Region specific response of intervertebral disc cells to complex dynamic loading: An organ culture study using a dynamic torsion-compression bioreactor. PLoS ONE 8, e72489. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Wang Z, Zhang LL, Agresti M, Matloub HS, Yan JG, 2014. A quantitative study of vibration injury to peripheral nerves – introducing a new longitudinal section analysis. HAND 9, 413–418. 10.1007/s11552-014-9668-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk F, Bennett DL, Mcmahon SB, 2017. Nerve growth factor and pain mechanisms. Annual Review of Neuroscience 40, 307–325. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-072116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuis JR, Dvorakova LS, Vetter I, 2017. Methods used to evaluate pain behaviors in rodents. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 10, 1–17. 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong RC, Guo LX, 2017. Effect of muscle soft tissue on biomechanics of lumbar spine under whole body vibration. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 18, 1599–1608. 10.1007/s12541-017-0189-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards D, Berry JJ, 1987. The efficiency of simulation-based multiple comparisons. Biometrics 43, 913–928. 10.2307/2531545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskander MA, Shivani R, Green DP, Chen PB, Por ED, Jeske NA, Gao X, Flores ER, Hargreaves KM, 2015. Persistent nociception triggered by nerve growth factor (NGF) is mediated by TRPV1 and oxidative mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience 35, 8593–8603. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3993-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatoye F, Gebrye T, Odeyemi I, 2019. Real-world incidence and prevalence of low back pain using routinely collected data. Rheumatology International 39, 619–626. 10.1007/s00296-019-04273-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gun BK, Banaag A, Khan M, Koehlmoos TP, 2022. Prevalence and risk factors for musculoskeletal back injury among U.S. Army personnel. Military Medicine 187, e814–e820. 10.1093/milmed/usab217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsgrove TP, Zeeman ME, Welch WC, Winkelstein BA, 2020. Pain after whole-body vibration exposure is frequency dependent and independent of the resonant frequency: Lessons from an in vivo rat model. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 142, 061005. 10.1115/1.4044547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illien-Junger S, Gantenbein-Ritter B, Grad S, Lezuo P, Ing D, Ferguson SJ, Alini M, Ito K, 2010. The combined effects of limited nutrition and high-frequency loading on intervertebral discs with endplates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 35, 1744–1752. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c48019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou MS, Fahnestock M, 2017. ProNGF, but not NGF, switches from neurotrophic to apoptotic activity in response to reductions in TrkA receptor levels. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, 599–611. 10.3390/ijms18030599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo R, Popolizio T, Aprile PD, Muto M, 2015. Spinal pain. European Journal of Radiology 84, 746–756. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartha S, Zeeman ME, Baig HA, Guarino BB, Winkelstein BA, 2014. Upregulation of BDNF and NGF in cervical intervertebral discs exposed to painful whole body vibration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39, 1542–1548. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AN, Jacobsen HE, Khan J, Filippi CG, Levine M, Lehman R, Riew KD, Lenke L, Chahine NO, 2017. Inflammatory biomarkers of low back pain and disc degeneration: A review. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 1410, 68–84. 10.1111/nyas.13551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Smith MT, 2015. Neurotrophins and neuropathic pain: Role in pathobiology. Molecules 20, 10657–10688. 10.3390/molecules200610657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox JB, Deal JB Jr., Knox JA, 2018. Lumbar disc herniation in military helicopter pilots vs. matched controls. Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance 89, 442–445. 10.3357/AMHP.4935.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollock R, Games K, Wilson AE, Sefton JM, 2015. Effects of vehicle-ride exposure on cervical pathology: a meta-analysis. Industrial Health 53, 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollock RO, Games KE, Wilson AE, Sefton JM, 2016. Vehicle exposure and spinal musculature fatigue in military warfighters: A meta-analysis. Journal of Athletic Training 51, 981–990. 10.4085/1062-6050-51.9.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LePage EC, Stoker AM, Kuroki K, Cook JL, 2020. Effects of cyclic compression on intervertebral disc metabolism using a whole-organ rat tail model. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 39, 1945–1954. 10.1002/jor.24886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffredo MA, Yan JG, Kao D, Zhang LL, Matloub HS, Riley DA Persistent reduction of conduction velocity and myelinated axon damage in vibrated rat tail nerves. Muscle and Nerve 39, 770–775. 10.1002/mus.21235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloub HS, Yan JG, Kolachalam RB, Zhang LL, Sanger JR, Riley DA Neuropathological changes in vibration injury: An experimental study. Microsurgery 25, 71–75. 10.1002/micr.20081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann MR, Patel P, Pest MA, Ratneswaran A, Lalli G, Beaucage KL, Backler GB, Kamphuis MP, Esmail Z, Lee J, Barbalinardo M, Mort JS, Holdsworth DW, Beier F, Jeffrey Dixon S, Séguin CA, 2015. Repeated exposure to high-frequency low-amplitude vibration induces degeneration of murine intervertebral discs and knee joints. Arthritis and Rheumatology 67, 2164–2175. 10.1002/art.39154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann MR, Veras MA, Yeung C, Lalli G, Patel P, Leitch KM, Holdsworth DW, Dixon SJ, Séguin CA, 2017. Whole-body vibration of mice induces progressive degeneration of intervertebral discs associated with increased expression of Il-1β and multiple matrix degrading enzymes. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 25, 779–789. 10.1016/j.joca.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker R, Williams R, 2015. The p75 neurotrophin receptor: At the crossroad of neural repair and death. Neural Regeneration Research 10, 721–725. 10.4103/1673-5374.156967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosavljevic S, Bagheri N, Vasiljev RM, McBride DI, Rehn B, 2012. Does daily exposure to whole-body vibration and mechanical shock relate to the prevalence of low back and neck pain in a rural workforce? Annals of Occupational Hygiene 56, 10–17. 10.1093/annhyg/mer068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnone G, Benedetti F. de, Bracci-Laudiero L, 2017. NGF and its receptors in the regulation of inflammatory response. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, 1028–1228. 10.3390/ijms18051028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtori S, Inoue G, Miyagi M, 2015. Pathomechanisms of discogenic low back pain in humans and animal models. The Spine Journal 15, 1347–1355. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.07.490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson F, Miralami R, Tansey KE, Prabhu RK, Priddy LB, 2021. Deleterious effects of whole-body vibration on the spine: A review of in vivo, ex vivo, and in vitro models. Animal Models and Experimental Medicine 4, 77–86. 10.1002/ame2.12163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope MH, Wilder DG, Magnusson M, 1998. Possible mechanisms of low back pain due to whole-body vibration. Journal of Sound and Vibration 215, 687–697. 10.1006/jsvi.1998.1698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tam V, Chan WCW, Leung VYL, Cheah KSE, Cheung KMC, Sakai D, McCann MR, Bedore J, Séguin CA, Chan D, 2018. Histological and reference system for the analysis of mouse intervertebral disc. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 36, 233–243. 10.1002/jor.23637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodorczyk-Injeyan JA, Triano JJ, Injeyan SH, 2019. Nonspecific low back pain inflammatory profiles of patients with acute and chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain 35, 818–825. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tria MA, Fusco M, Vantini G, Mariot R, 1994. Pharmacokinetics of nerve growth factor (NGF) following different routes of administration to adult rats. Experimental Neurology 127, 178–183. 10.1006/exnr.1994.1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner P. v., Pang DSJ, Lofgren J, 2019. A review of pain assessment methods in laboratory rodents. Comparative Medicine 69, 451–467. 10.30802/AALAS-CM-19-000042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg R, Jongbloed EM, de Schepper EIT, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Koes BW, Luijsterburg PAJ, 2018. The association between pro-inflammatory biomarkers and nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. The Spine Journal 18, 2140–2151. 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.06.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade KR, Schollum ML, Robertson PA, Thambyah A, Broom ND, 2016. ISSLS prize winner: Vibration really does disrupt the disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 41, 1185–1198. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Dai J, Wang C, Gao Z, Liu Y, Dai M, Zhao Z, Yang L, Tan G, 2022. Assessment of low back pain in helicopter pilots using electrical bio-impedance technique: A feasibility study. Frontiers in Neuroscience 16, 883348. 10.3389/fnins.2022.883348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki S, Banes AJ, Weinhold PS, Tsuzaki M, Kawakami M, Minchew JT, 2002. Vibratory loading decreases extracellular matrix and matrix metalloproteinase gene expression in rabbit annulus cells. The Spine Journal 2, 415–420. 10.1016/S1529-9430(02)00427-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Liu S, Ling M, Ye C, 2022. Prevalence and potential risk factors for occupational low back pain among male military pilots: A study based on questionnaire and physical function assessment. Frontiers in Public Health 9, 744601. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.744601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeman ME, Kartha S, Jaumard N. v, Baig HA, Stablow AM, Lee J, Guarino BB, Winkelstein BA, 2015. Whole-body vibration at thoracic resonance induces sustained pain and widespread cervical neuroinflammation in the rat. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 473, 2936–2947. 10.1007/s11999-015-4315-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeman ME, Kartha S, Winkelstein BA, 2016. Whole-body vibration induces pain and lumbar spinal inflammation responses in the rat that vary with the vibration profile. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 34, 1439–1446. 10.1002/jor.23243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Hu B, Liu W, Wang P, Lv X, Chen S, Shao Z, 2021. The role of structure and function changes of sensory nervous system in intervertebral disc-related low back pain. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 29, 17–27. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]