Abstract

Bioresorbable stents (BRS) hold great promise for the treatment of many life-threatening luminal diseases. Tracking and monitoring of stents in vivo are critical for avoiding their malposition and inadequate expansion, which often leads to complications and stent failure. However, obtaining high X-ray visibility of polymeric BRS has been challenging because of their intrinsic radiolucency. This study demonstrated the use of photopolymerization-based 3D printing technique to fabricate radiopaque BRS by incorporating iodixanol, a clinical contrast agent, into a bioresorbable citrate-based polymer ink. The successful volumetric dispersion of the iodixanol through the 3D-printing process conferred strong X-ray visibility of the produced BRS. Following in vitro degradation, the 3D-pritned BRS embedded in chicken muscle maintained high X-ray visibility for at least 4 weeks. Importantly, the 3D-printed radiopaque BRS demonstrated good cytocompatibility and strong mechanically competence in crimping and expansion, which is essential for their minimally invasive deployment. In addition, it was found that higher loading concentrations of iodixanol, e.g. 10 wt% would result in more strut fractures in stent crimping and expansion. To conclude, this study introduces a facile strategy to fabricate radiopaque BRS through the incorporation of iodixanol in 3D printing process, which could potentially increase the clinical success of BRS.

Keywords: Bioresorbable stents, X-ray visibility, radiopacity, iodixanol

Graphical Abstract

A radiopaque bioresorbable stent (BRS) is developed through the incorporation of a US F.D.A.-approved contrast agent, i.e. iodixanol, into a 3D-printable, citrate-based polymer ink. The 3D-printed BRS confers strong X-ray visibility in chicken muscle tissues, mechanical competence during stent crimping and expansion procedures, and excellent in vitro biocompatibility.

1. Introduction

Luminal diseases, including vascular and nonvascular diseases have become a significant burden to the public health. For instance, vascular diseases, such as atherosclerotic coronary artery disease and peripheral artery disease, caused by the narrowing or clogging of blood vessels from plaque build-up, affect over 274 million people globally and are responsible for significant mortality rates[1]. On the other hand, nonvascular diseases, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease affects approximately 40% of adults and esophageal strictures occur in 1.1 per 10,000 person-years[2]. The placement of stents has been a widely used clinically to treat luminal diseases by re-opening the narrowed or occluded lumen and allowing the diseased lumen to regain its original healthy conditions. Currently used stents consists of a tubular metallic mesh structure that provides mechanical support to a dilated vessel. Despite many successes, there are growing concerns about the permanent presence of metallic stents, including long-term complications such as late thrombosis for vascular stents, the prevention of future intervention at the same site, and the impaired biomechanics of the permanently caged lumen[3].

Bioresorbable stents (BRS) can address these issues as they are intended to provide temporary mechanical support while allowing the tissue to remodel and restore biological function[3b]. The majority BRS are made by synthetic polymers, poly(l-lactic acid) (PLLA) being the most commonly used polymer[4]. However, most polymers exhibit the following shortcomings that can limit their use: 1) the oxidative tissue damage and subsequent exacerbated inflammation caused by their degradation products; 2) suboptimal mechanical properties; and 3) the lack of radiopacity, leading to poor X-ray visibility during stent deployment. To address these limitations, we have been developing BRS using bioresorbable citrate-based biomaterials (CBBs). In addition to their antioxidant properties and excellent biocompatibility, CBBs have been demonstrated to be compatible with high-resolution 3D printing process to rapidly fabricate polymeric BRS with customized anatomical geometry and size[5]. Notably, CBBs have been used for implantable orthopedic device granted clearance from US Food and Drug Administration (F.D.A.)[6]. Recently, the mechanical properties of CBBs were significantly improved by the incorporation of PLLA nanophase, leading to the successful production of low-profile bioresorbable vascular scaffolds with strut thickness less than 100 μm, which is 33% thinner than PLLA-based Absorb GT1 scaffold (Abbott Vascular) (150 μm), while sustaining physiologically relevant vessel loading (unpublished data). However, the radiopacity of CBB-based BRS has not been investigated.

The clinical success of vascular stents is critically relying on its X-ray visibility as their malposition and inadequate expansion are the major predisposing factors to acute thrombosis and an acute myocardial infarction, i.e. heart attack[7]. Unfortunately, the BRS made of polymer materials have intrinsically low X-ray visibility. The most commonly used method to make polymeric BRS visible under X-ray is to attach radiopaque metallic markers.[8] Currently used radiopaque markers made of metals with higher atomic weight, such as gold, platinum and tantalum are not bioresorbable, leading to potential concerns of leaving such millimeter-sized metal piece inside the body after the full resorption of BRS polymer. Moreover, the common practice of placing radiopaque makers only at the distal and proximal ends does not provide sufficient structural details of BRS upon expansion. Thus, it is desirable to introduce the X-ray contrast to the bulk of the BRS so the whole structure can be visible under the fluoroscope. To address this issue, the addition of a radiocontrast agent into the polymer matrix has been utilized to make radiopaque polymer composites. Iodine-based contrast agents, such as iodine and 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid have been chemically conjugated or blended into a polymer matrix to confer radiopacity[9]. Alternatively, barium sulfate has been used as a radiopaque agent for PLA or PLLA-based BRS[10]. However, the clinical application of these radiopaque agents has been hindered due to concerns with their biocompatibility[10d]. By contrast, iodixanol (Visipaque, GE Healthcare), a US F.D.A.-approved-X-ray contrast agent, has been in wide clinical use because of its low binding to biological receptors, low toxicity, and high biotolerability[11]. For example, a large body of clinical data show that iodixanol was associated with a low risk of contrast-induced nephropathy, which commonly occurs in patients undergoing angiography[12]. Therefore, iodixanol is a promising candidate filler material to confer radiopacity properties to polymeric BRS. Furthermore, we have previously reported the method to 3D print BRS using micro-Continuous Liquid Production (μCLIP) from a vat of liquid resin[5], which opens the opportunity to maximize the volumetric loading of iodixanol in the 3D-printed BRS and to confer strong X-ray visibility of the resulting polymeric BRS.

In this study we demonstrated the feasibility of incorporating iodixanol into novel light-curable CBBs, i.e. methacrylated poly(1,12 dodecamethylene citrate) (mPDC), to produce a radiopaque and biocompatible BRS via 3D-printing. The impacts of iodixanol incorporation on the radiopacity, mechanical properties, and biocompatibility of the devices were evaluated and analyzed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. mPDC containing iodixanol enables the successful fabrication of radiopaque BRS

The radiopaque polymeric ink was prepared by the addition of iodixanol in powder form at different concentrations (3, 5, and 10 wt%) into the mPDC (Figure 1A). The addition of 1 wt% stearic acid was used to facilitate the dispersion of iodixanol power within the polymeric ink and prevent their sedimentation during the 3D printing process[10c, 13]. The radiopaque polymeric ink was successfully photopolymerized during the 3D printing process to produce the bioresorbable vascular stent and esophageal stent (Figure 1B). BRS with strut sizes of 107, 206 and 456 μm were produced and their strut sizes were measured on scanning electron microscope (SEM) images (Figure 1C). Strut shrinkage (~10-20 %) following post-printing heat treatment (120°C, 12 hours) was observed for 3D-printed BRS due to the solvent evaporation and thermal curing via polycondensation reaction. The shrinkage of 3D-printed parts has been commonly observed in various 3D printing techniques and ink compositions, which can be easily compensated by the increase of designed values in the CAD model. The shrinkage can be also leveraged to improve the printing resolution[14]. The successful incorporation of iodixanol was validated by the presence of iodine in the polymer matrix of the BRS as shown in the energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) mapping and spectrum (Figure 2). The cross-sectional EM images revealed a rougher surface of mPDC/iodixanol BRS than pure mPDC BRS due to the presence of iodixanol particles with particle size varied from 8 to 50 μm (Figure 2A). No visible difference in surface morphology between mPDC and mPDC/iodixanol BRS was observed (Figure S2). The aligned textures on BRS surfaces were due to intrinsic surface structures of Teflon membrane used in the 3D printing system and subsequent rough boundary of the oxygen dead-zone, as discussed in our previous study[15]. In addition, there were no visible stair-casing features in our 3D-printed BRS due to the adoption of μCLIP in our 3D-printing process, which enables a layerless and monolithic fabrication of 3D parts[16]. Therefore, we would expect isotropic mechanical properties and radiopacity of our 3D-printed BRS.

Figure 1.

3D-printing of radiopaque BRS. (A) Schematic of preparation and 3D-printing of radiopaque ink. (B) CAD models and photos of 3D-printed bioresorbable vascular stent and esophageal stent. (C) Representative cross-sectional scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of 3D-printed BRS1, BRS2, and BRS3 containing 5 wt% iodixanol with increased strut thickness as well as their measured dimensions, including strut thickness and inner diameter (n = 4). The designed values of strut thickness were 137 μm for BRS1, 255 μm for BRS2, and 510 μm for BRS3.

Figure 2.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) elemental analysis validates the presence of iodixanol within BRS. (A) Cross-sectional electron microscope (EM) images and EDS mapping data. The magenta signal indicates the localization of elemental iodine. (B) Typical EDS spectrum of BRS that are prepared from mPDC and mPDC/iodixanol composite with 5 wt% iodixanol and molecular structure of iodixanol with highlighted iodine. The Au and Pd peaks are resulted from the conductive coating layer to avoid charging problem in SEM.

Suboptimal sizing of stents has been a long-standing issue in treating luminal disease, due to the higher incidence of stent migration, in-stent restenosis, and ultimately device failure of stents with suboptimal sizes[17]. A stent manufactured with dimension designed to specifically fit to a patient’s anatomy could address this issue. However, the manufacturing of a stent with unique design using the traditional method, i.e. selective laser cutting of a hollow tube, can be costly and time consuming. The 3D printing method presented in this study, i.e. μCLIP, represents a viable solution by significantly shortening the design-to-product cycle and reducing the cost. For example, an 8 mm long BRS could be printed in 7 min or less. The estimated material and manufacturing cost for each BRS is less than $1. These advantages offer the possibility of affordable and urgent treatment of patients who need stent placement.

BRS with different dimensions were scanned using micro-computed tomography (CT) to evaluate their radiopacity. The CT images showed that the pure mPDC BRS (control) are almost radiolucent and barely visible even for the thickest BRS3 under micro-CT imaging. The addition of iodixanol conferred radiopacity to the BRS (Figure 3A). The radiopacity value of the BRS was increased by increasing the amount of iodixanol that was loaded into the BRS, which could be controlled by the iodixanol concentration in the mPDC ink (Supporting Information Figure S1A) and/or the strut thickness of the BRS. The uniform radiopacity along the length of the BRS (i.e. printing direction) suggests the homogeneous distribution of iodixanol within the BRS, which is ascribed to the presence of stearic acid in the ink and the μCLIP-enabled high-speed, layerless fabrication process.

Figure 3.

Micro-CT and fluoroscopy images of BRS reveal their radiopacity in air and chicken thigh. (A) Representative radiographic images of BRS, including Ctrl and radiopaque BRS with 5 wt% iodixanol, were acquired by placing them in air or inside a chicken thigh in the presence of bone and micro-CT scanning. (B) The radiopacity of BRS was quantified by mean Hounsfield unit (relative to their control), which was increased with strut thickness (n = 3). (C) The fluoroscopic images of BRS were acquired in vitro. All the radiopaque BRS here contain 5 wt% iodixanol.

The radiopacity was further evaluated by embedding the BRS into the chicken thigh muscle to more closely imitate in vivo conditions. All BRS showed lower visibility when they were embedded within the muscle relative to air because of the elevated background radiopacity resulting from muscle tissues and bones. Only the BRS3 with 450 μm strut thickness was clearly visible under micro-CT imaging. BRS with thinner struts (i.e. BRS1 and BRS2) or without iodixanol (control) are barely visible. In line with the visual contrast as shown in the radiograph, the quantified relative mean values of Hounsfield Unit showed the highest value for BRS3 (Figure 3B). The reduced visibility of BRS embedded in chicken thigh muscle confirms the importance of evaluating the radiopacity in the presence of muscle tissues and bone in order to more closely replicate the in vivo conditions. This finding is important as most studies in the literature only assess the radiopacity of the device in air before moving to animal work. In addition, the visibility of BRS was also successfully verified under fluoroscopy, which is used to track and guide stent placement during surgery (Figure 3C).

2.2. 3D-printed radiopaque BRS is mechanically competent for minimally invasive deployment

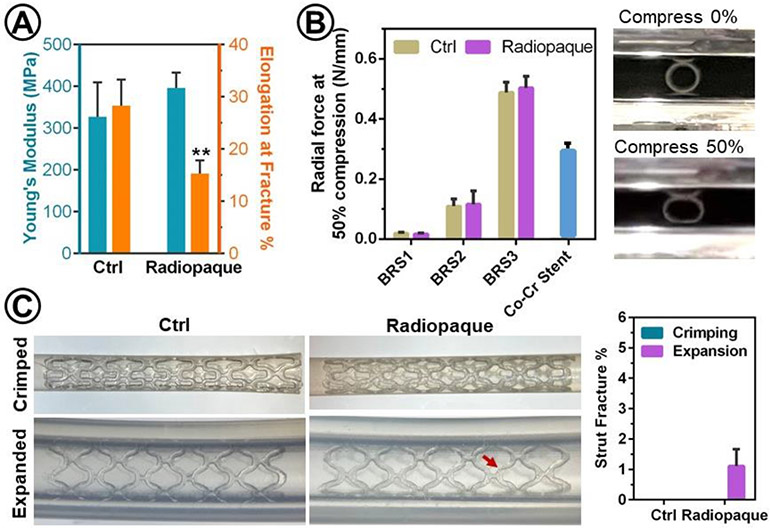

The mechanical properties of BRS are critical for their minimally invasive deployment and capacity to prevent the collapse of a lumen that has undergone surgical treatment. The tensile stress-strain curves of polymers were acquired using 3D-printed dog-bone-shaped samples. In comparison to pure mPDC, the mPDC-iodixanol composite showed statistically similar Young’s modulus (396 ± 36 MPa vs. 327 ± 82 MPa for mPDC) and significantly lower elongation at fracture (15.3 ± 2.5 % vs. 28.3 ± 5.0 % for mPDC) (Figure 4A), suggesting that the addition of iodixanol reduced the polymer ductility. The radial force was measured by compressing the 3D-printed stents under two-parallel plates (Figure 4B). The results showed that all 3D-printed BRS can survive the 50% compression without fracture. The radial forces at 50% compression were similar between radiopaque BRS and control while being dramatically increased by the strut thickness. Specifically, the BRS2 and BRS3 showed 3-fold and 11-fold increase in radial forces compared to the BRS1. Given the inherent mechanical weakness of polymers, the radial forces of BRS1 and BRS2 are much lower than that of cobalt chromium (Co-Cr) alloy stents (XIENCE® Sierra stents from Abbott Vascular), which are widely used for the treatment of coronary artery lesions in clinic. It is worth noting that the radial force of BRS2 (0.12 N/mm) at 50% compression is similar or superior to the contrast agent-doped PLLA BRS with comparable strut thickness, which has radial force between 0.06 to 0.12 N/mm[10d]. Notably, the radial force of BRS3 (0.50 N/mm) surpassed the Co-Cr stent (0.3 N/mm) and could be beneficial for the treatment of lesions in tissue structures with large-sized lumens such as the esophagus or intestine.

Figure 4.

The impacts of iodixanol on mechanical properties of BRS. (A) Young’s moduli and elongation at fracture were measured by tensile test using 3D-printed dog-bone samples. Significant difference is marked as ** for p < 0.01 (n=4) as compared to Ctrl. (B) Radial forces of BRS and a Co-Cr stent (XIENCE Sierra™ metal stent for coronary artery disease from Abbott Vascular) as measured by two-parallel plate compression test and representative photographs of BRS1 before and after compression by 50% of its initial diameter (n=4). (C) Representative photographs of BRS and quantification of their strut facture (%, n = 3) after crimping (crimped) and deployment (expanded) into an artificial lumen, i.e. silicone tube with inner dimeter of 2.5 mm using balloon dilation catheter. Arrows indicate struct fractures. Control (Ctrl): mPDC; Radiopaque: mPDC/iodixanol composite. All the radiopaque BRS here contain 5 wt% iodixanol.

The procedures for crimping and expansion of the BRS are essential to their successful minimally invasive deployment in tissues with diseased lumen. The mPDC (ctrl) and mPDC/iodixanol (radiopaque, containing 3 and 5 wt% iodixanol) BRS were successfully crimped from their original diameter of 2.2 mm down to 1.1 mm without any strut fracture occurred (Figure 4C and Supporting Information Figure S1B, C). The radiopaque BRS containing 10 wt% iodixanol showed some struct fracture during crimping process because of the reduction of stent ductility (Supporting Information Figure S1B, C). Moreover, we demonstrated that the crimped BRS could be successfully deployed within an artificial lumen (i.e. silicon tube) using a balloon expansion catheter (Figure 4C). Following expansion, no strut fracture was observed on mPDC BRS (ctrl). However, radiopaque mPDC/iodixanol BRS did show some strut fractures as indicated by arrows in the digital images of expanded BRS (Figure 4C and Supporting Information Figure S1B, C). The percentages of strut fractures per stent were increased with increasing the loading concentrations of iodixanol. Specifically, less than 1 % struts of BRS with 3 and 5 wt% iodixanol were fractured while strut fracture was increased to 4.4% of BRS with 10 wt% iodixanol. Therefore, we chose the loading concentration of 5 wt% iodixanol for additional evaluation in this study.

Although the mechanical performance during crimping and expansion of the BRS is essential to their minimally invasive deployment, it has been rarely evaluated upon the addition of contrast agents into BRS in previous reports. Numerical simulation suggested the strut fracture of PLLA stent containing contrast agent of BaSO4 due to the reduced ductility of the materials upon the addition of BaSO4[10c]. Chausse et al. expanded PLLA-based stents with contrast agents by applying a 16 atm pressure using balloon to test the expansion capability of stents[10d]. They found the strut detachment at fused junctions of expanded stent due to some intrinsic features of the fabrication process, including sequential deposition of polymers and poorly controlled solvent evaporation. Such spatial heterogeneity of mechanical properties, such as mechanically weak junctions could be eliminated using our 3D-printing method, where an entire cross-sectional layer of the part was photopolymerized at one time. Our results show that the addition of iodixanol reduces the ductility of the BRS and increases the likelihood of strut fracture during the expansion of crimped device. This finding suggests that iodixanol might have poor interactions with mPDC polymer matrix and likely hinders the mobility of the polymer chains. Similar observation has been reported in several polymeric composite systems, especially for fillers with poor adhesion to the matrix or a high filler loading[10c, 18]. It has been suggested that filler materials dispersed in a polymer matrix may interfere the local deformation with poor or no stress transfer, leading to impaired ductility[19]. Matrix deformation and stress transfer are influenced by both interfacial interactions and dispersion state of the fillers. Therefore, a lack of active interactions between iodixanol and mPDC polymer matrix and the presence of iodixanol agglomeration (as revealed in Figure 2A) could result in the decrease in ductility and strut fractures during device crimping and expansion. To address this issue, an appropriate surface modification of iodixanol, such as using stearic acid[10c, 13] or organo-silanes[20], may be utilized to improve their dispersion states and/or interactions with polymer matrix, potentially enabling a high loading concentration of iodixanol without compromising mechanical functions of the device. Indeed, we introduced a 1 wt% stearic acid as a surfactant in the mPDC/iodixanol composite ink, which prevented the quick sedimentation of iodixanol during 3D-printing process and achieved a uniform radiopacity over the entire BRS. However, this method did not effectively inhibit iodixanol agglomeration to improve the ductility of BRS. The incorporation of stearic acid through chemical conjunction[10c] or intensive physical mixing[13] with iodixanol prior to the blending with mPDC polymer should be pursued in future studies.

2.3. Iodixanol release and BRS degradation

It is important to be able to visualize the stent while the degradation process takes place. To assess the release of iodixanol and the X-ray visibility of BRS over time, the BRS were incubated in PBS at 37°C under dynamic conditions (shaking at 150 rpm) (Figure 5). At pre-determined time points, the amount of released iodixanol in PBS was first detected by its absorbance at 244 nm (Figure 5A). BRS showed sustained release of iodixanol for at least 12 weeks. For example, considering the nominal loading amount of iodixanol per stent, i.e. 0.7 mg for BRS3, there were 32 % and 48 % iodixanol were released from the BRS3 in first 6 hours and 12 weeks, respectively. The surface absorbed iodixanol likely contributes to the relatively fast release in the first 6 hours while the release afterwards is largely mediated by the degradation of mPDC polymer, which can take up to 6-18 months[5a].

Figure 5.

Iodixanol release and BRS degradation in their radiopacity, weight, and radial strength over time. (A) The cumulative release of iodixanol from BRS were evaluated by incubating BRS in PBS at 37°C under agitation and measuring absorbance at 244 nm (n = 6). (B) BRS3 radiographs and (C) the quantified mean Hounsfield unit (n = 3) were accessed by micro-CT scanning of BRS embedded in chicken thigh muscle after releasing for 2, 4, and 12 weeks. (D) Mass loss and (E) decrease of radial force at 50% compression of BRS over 12-week degradation (n = 4).

To assess the long-term X-ray visibility of BRS, the radiopacity of BRS was measured by micro-CT scan after incubation in PBS for 2, 4, and 12 weeks (Figure 5B and 5C). It was found that the radiopacity decreased over time due to the loss of iodixanol. BRS3 remained visible under micro-CT scans after 2 and 4 weeks while its visibility was significantly reduced at 12 weeks, which was consistent with the drop of the mean values of Hounsfield Unit. The long-term X-ray visibility of our radiopaque BRS is superior to the radiopaque hydrogels containing iodixanol in a previous report, which associates a great drop of their radiopacity after immersion in saline for 1 day because of the rapid release of iodixanol[21]. In addition, BRS degradation was evaluated by the change of the weight and radial forces over 12 weeks (Figure 5D and 5E). The mass loss of BRS was under 12.5%. The decrease of radial strength was highly dependent on the initial strut thickness. Specifically, there were 50%, 30%, and 10% decrease in radial strength of BRS1, BRS2, and BRS3, respectively. A slightly larger mechanical drop was observed for radiopaque BRS than the control due to the release of iodixanol. Notably, larger amount of iodixanol release (~ 48%) was found than the weight loss (~ 13%) of BRS3 over 12 weeks, which can be attributed to the degradation of the mPDC polymer. Like other polyesters, the degradation of mPDC polymer relies on water diffusion into the polymer network and the subsequent hydrolytic breakdown of ester bonds[22]. Thus, the high solubility of the iodixanol in the water along with the degradation of the polymer network collectively accelerate the diffusion of the encapsulated iodixanol from the BRS. Interestingly, a previous study reported that an iodine-containing PLLA stent did not show an apparent drop in radiopacity and radial forcewas after immersion in PBS for 3 months due to the low degradation rate of PLLA, which can take more than 2-3 years for full resorption and may hinder the tissue recovery[23].

2.4. Radiopaque BRS are cytocompatible

The cytocompatibility was evaluated by incubating human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with leached extracts from the 3D-printed radiopaque BRS (Figure 6). Vascular endothelial cells were used as a clinically relevant primary cell type that has close interactions with BRS in the vasculature when stents were used to re-open arterial blockages. The number of viable HUVECs that were incubated in leachable extracts of radiopaque BRS for 1 day was not significantly different from the group with growth medium (control), indicating that the high cell viability was maintained by the radiopaque BRS. HUVECs from all groups exhibited similar and typical cobblestone morphology. Thus, the radiopaque BRS showed good cytocompatibility.

Figure 6.

Cytocompatibility of Radiopaque BRS. HUVECs were seeded on tissue culture polystyrene and incubated in extracts from the radiopaque BRS and growth medium as control. BRS extracts showed high cell viability (MTT assay) and healthy cell morphology (light microscope), which were comparable to cells incubated in growth medium. n = 4. All the radiopaque BRS here contains 5 wt% iodixanol.

Despite US F.D.A.-approved clinical use of iodixanol, previous studies have showed the toxic and/or activating effects of iodixanol on mammalian cells, which highly dependent on iodixanol dosage[21, 24]. For instance, iodixanol at concentration of 10 mg iodine/mL or higher induced decreased viability, increased oxidative status, and elevated secretion of pro-inflammatory products of vascular endothelial cells[24]. These adverse effects were significantly dampened when the iodixanol concentration was lower than 1-5 mg iodine/mL. In addition, the burst release of iodixanol within 24 hours from radiopaque hydrogels resulted in decreased viability of fibroblast cells[21]. In this study, the nominal loading amounts of iodixanol were 0.15 mg (BRS1), 0.3 mg (BRS2), and 0.7 mg (BRS3) per stent. Moreover, such small amount of iodixanol is slowly released from the BRS over several months, e.g. less than 50% iodixanol is released in 12 weeks (Figure 5A). Therefore, no in vitro cytotoxicity of radiopaque BRS is observed on HUVEC in this study. It is worth noting that the highest iodixanol concentration in peripheral circulation is in the range of 0.97-11 mg/mL with a median of 4.7 mg/mL after its intravascular injection at clinically allowable doses[25]. Considering further dilution of slowly released iodixanol from our BRS under blood circulation, we expect thousand-fold reductions in iodixanol concentration in blood flow being resulted from BRS as compared to angiography in current clinical practice. Therefore, we do not anticipate any issue with the in vivo biocompatibility of our radiopaque BRS.

3. Conclusion

This study describes a clinically relevant strategy to fabricate a radiopaque polymeric BRS with strong X-ray visibility that enables device visualization during minimally invasive deployment and follow-up monitoring. Iodixanol, a US F.D.A.-approved contrast agent, was introduced into a photo-curable and bioresorbable citrate-based pre-polymer to make a radiopaque ink, which was used to produce a radiopaque BRS via a 3D printing technique. The 3D-printed BRS, which contains a relatively small amount of iodixanol (e.g. 0.7 mg per stent), showed strong X-ray visibility when imaged in air or embedded in chicken thigh muscle. X-ray visibility of the BRS is maintained for at least 4 weeks due to the slow release of incorporated iodixanol, enabling the non-invasive monitoring of the BRS in vivo. Moreover, the 3D-printed BRS showed strong mechanical competence during stent crimping and expansion procedures in vitro. We found that the addition of iodixanol compromised ductility of the stent and led to more strut factures during crimping and expansion process, which were augmented when a high concentration of iodixanol, i.e. 10 wt% was incorporated into BRS. The trade-off between radiopacity and mechanical functions needs to be considered for different applications of BRS. The 3D-printed BRS showed good in vitro cytocompatibility to vascular endothelial cells. In the future, the prepared radiopaque BRS will be evaluated in vivo, such as in esophagitis rat model, in term of their deployment, early-stage monitoring, and biocompatibility.

4. Experimental Section

Materials:

All chemicals were obtained from Millipore Sigma unless otherwise noted.

Ink preparation:

Methacrylated poly(1,12 dodecamethylene citrate) (mPDC) was synthesized by following the protocol as reported in our previous study[5a]. Briefly, citric acid and 1,12-dodecanediol were melted (165°C, 22 min) in a 2:1 molar ratio, co-polymerized (140 °C, 60 min), purified and freeze-dried to yield PDC pre-polymer. Every 22 g PDC pre-polymer was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (180 mL) with imidazole (816 mg) and glycidyl methacrylate (17.8 mL), reacted (60°C, 6 hours), purified, and freeze-dried to yield mPDC pre-polymer. Visipaque (GE Heathcare, Princeton, NJ) was freeze-dried and grinded to yield fine powder of iodixanol. To formulate mPDC ink (control), 75 wt% mPDC was mixed with 2.2 wt% Irgacure 819 acting as a primary photoinitiator and 3.0 wt% Ethyl 4-dimethylamino benzoate (EDAB) being a co-photoinitiator, in a solvent of pure ethanol. To formulate mPDC/iodixanol composite ink, 5 wt% of iodixanol and 1 wt% stearic acid was mixed with prepared mPDC control ink with the aid of a probe sonicator (Branson Sonifier 150, Branson Ultrasonics Corporation, Brookfield, CT).

3D printing:

3D printing was performed using a homemade micro-continuous liquid production process (μCLIP) based printer. An oxygen-permeable window made of Teflon AF-2400 (Biogeneral Inc., San Diego, CA) was attached to the bottom of the resin vat. A digital micromirror device (DMD, Texas Instruments Inc., Plano, TX) was utilized as the dynamic mask generator to pattern the UV light (365 nm). Projection optics of the printer were optimized to have a pixel resolution of 7.1 μm x 7.1 μm at the focal plane. CAD files of the print part were designed in SolidWorks (Dassault Systèmes, Waltham, MA). The resulting STL files were sliced for a 2D file output by MATLAB (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA) code developed in-house using a slicing thickness of 5 μm. Full-screen images were projected onto the vat window for photopolymerization. The printed layer thickness was 5 μm with printing time of 0.365 s for each layer. After printing, the parts were rinsed in ethanol to remove the unpolymerized ink and moved into a heating oven and cured at 120°C for 12 hours.

Structural and elemental analysis by scanning electron microscope (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS):

The samples were freeze-fractured to reveal the cross-section and sputter-coated with gold and platinum before SEM and EDS examination. The structure and morphology of 3D-printed BRS was examined using SEM (Hitachi SU8030, Japan). The SEM images were analyzed by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) to measure the strut thickness and diameter of stents. The elemental analysis was performed by EDS detector (Oxford AZtech X-max 80 SDD). The iodine was examined to identify the presence and distribution of iodixanol in stents.

Measurement of radiopacity by micro-computed tomography (CT) imaging:

BRS were scanned in a micro-CT scanner (nanoScan PET/CT, Mediso-USA, Boston, MA). Data were acquired under the following parameters: X-ray tube voltage of 50 kVp, 1 x 1 binning, 720 projection views over a full circle, and 300 ms exposure time. The projection data was reconstructed with a voxel size of 34 μm (in all directions) and using filtered (Butterworth filter) back-projection software from Mediso. Amira 2021.2 (FEI Co, Hilsboro, OR) was used to segment the stents, followed by 3D rendering. The radiopacity of the specimens was quantified using the mean intensity of segmented stents in Hounsfield Units for statistical analysis.

Measurement of mechanical properties:

To measure the Young’s modulus and elongation at fracture, the dog-bone shaped samples was prepared in the same 3D-printing and post-processing conditions to BRS. A tensile test was performed using Instron universal tester (Model 5940, Instron, High Wycombe, UK) equipped with a 2 kN load cell at a crosshead displacement speed of 1 mm/min, which conformed to ISO 527:2012.

To measure the radial force of the BRS, a stent was placed between two parallel plates of Instron universal tester (Model 5940, Instron) and measuring its resistance force while compressing it down to 50% of its original diameter at a crosshead displacement speed of 1 mm/min, which conformed to ISO 25539-2. Radial force was measured and normalized by the respective stent length and given in N/mm.

To access the crimping and deployment performances of the BRS, stents were crimped onto a metal wire (1.3 mm in diameter) and put into a PTFE sheath to prevent the elastic recovery of the stents. The stent within a PTFE sheath was loaded onto an over-the-wire balloon dilatation catheter with 2.25 mm in balloon diameter and 15 mm in balloon length (Sprinter™, Medtronic). The stents were deployed into a silicon tube with an inner diameter of 2.5 mm as an artificial artery by pushing out the stents out of PTFE sheath and then inflating the balloon at a rate of 1 atm per 10 seconds up to 6 atm. The balloon catheter was retracted from the silicon tube by deflating the balloon and the stent was left inside the silicon tube. The crimped and deployed stents were observed and imaged under optical microscope to assess the strut fracture.

Iodixanol release:

Each BRS was placed in a release medium of 1 mL PBS under 150 rpm agitation at 37°C. The release media were collected and refreshed at the pre-determined time points (6 hours, 12 hours, 1 day, 3 days, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 weeks). The amount of iodixanol in the release medium was measured by the absorbance at 244 nm using a microplate reader Cytation 5 (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT). At 2, 4 and 12 weeks, three stents from each group were dried under vacuum at room temperature and then imaged using micro-CT scanner to reveal the change of their radiopacity over time. At 12 weeks, radial forces (hydrated) and weight (dried) were measured to evaluate their degradation.

Cytotoxicity test:

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; ATCC, Manassas, VA) were expanded in growth media consisting of Endothelial Cell Growth Kit-VEGF (ATCC® PCS-100-041) in Vascular Cell Basal Medium (ATCC® PCS-100-030) under the standard culture condition (37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humid environment) to 80% confluency before passaging. HUVECs at passages 5-7 were used.

The effect of the iodixanol introduction on the cytotoxicity of BRS was evaluated by means of an indirect cytotoxicity assay following ISO 10993-5: 2009. Specifically, the BRS were first sterilized by Ethylene Oxide and 0.5 mL of growth media was incubated with BRS for 24 hours at 37 °C with agitation. Next, the liquid extracts of different BRS were collected and added to HUVECs at sub-confluence in 24-well pates. After incubation for 24 hours, cells were incubated with growth media containing 0.5 mg/mL MTT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) for 3 hours. After replacing the MTT solution with DMSO, the plate was shaken for 15 min to solubilize the formazan crystals, and the absorbance of each well was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader Cytation 5 (BioTek Instruments). The number of viable cells per well was calculated against a standard curve prepared by plating various concentrations of isolated cells, as determined by hemocytometer, in triplicate in the culture plates.

Statistical analysis:

Unless otherwise specified, data presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). For each experiment, at least three samples were analyzed. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test was used to analyze statistical significance. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health, United States (Grant: R01HL141933). Y. Ding was supported in part by American Heart Association Career Development Award (AHA, Grant: 852772). Micro-CT imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Molecular Imaging generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Yonghui Ding, Center for Advanced Regenerative Engineering (CARE), Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA; Department of Biomedical Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 60208, USA.

Rao Fu, Center for Advanced Regenerative Engineering (CARE), Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA; Department of Mechanical Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA.

Caralyn Paige Collins, Center for Advanced Regenerative Engineering (CARE), Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA; Department of Mechanical Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA.

Cheng Sun, Center for Advanced Regenerative Engineering (CARE), Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA; Department of Mechanical Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA.

Guillermo A. Ameer, Center for Advanced Regenerative Engineering (CARE), Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA; Department of Biomedical Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 60208, USA; Department of Surgery, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, 60611, USA

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].Bauersachs R, Zeymer U, Brière J-B, Marre C, Bowrin K, Huelsebeck M, Cardiovasc. Ther 2019, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Desai JP, Moustarah F, StatPearls [Internet] 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Hoare D, Bussooa A, Neale S, Mirzai N, Mercer J, Advanced Science 2019, 6, 1900856; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jinnouchi H, Torii S, Sakamoto A, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Finn AV, Nature Reviews Cardiology 2019, 16, 286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhu Y, Yang K, Cheng R, Xiang Y, Yuan T, Cheng Y, Sarmento B, Cui W, Mater. Today 2017, 20, 516. [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Van Lith R, Baker E, Ware H, Yang J, Farsheed AC, Sun C, Ameer G, Advanced Materials Technologies 2016, 1; [Google Scholar]; b) Ware HOT, Farsheed AC, Akar B, Duan C, Chen X, Ameer G, Sun C, Materials Today Chemistry 2018, 7, 25. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bradley D, Mater. Today 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Im E, Kim B-K, Ko Y-G, Shin D-H, Kim J-S, Choi D, Jang Y, Hong M-K, Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv 2014, 7, 88; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nakano M, Yahagi K, Otsuka F, Sakakura K, Finn AV, Kutys R, Ladich E, Fowler DR, Joner M, Virmani R, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2014, 63, 2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Nef HM, Wiebe J, Foin N, Blachutzik F, Dörr O, Toyloy S, Hamm CW, Int. J. Cardiol 2017, 227, 127; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Werner M, Micari A, Cioppa A, Vadalà G, Schmidt A, Sievert H, Rubino P, Angelini A, Scheinert D, Biamino G, JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 305; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Park J-S, Yim KH, Jeong S, Lee DH, Kim DG, Gut and liver 2019, 13, 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Nottelet B, Coudane J, Vert M, Biomaterials 2006, 27, 4948; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Singhana B, Chen A, Slattery P, Yazdi IK, Qiao Y, Tasciotti E, Wallace M, Huang S, Eggers M, Melancon MP, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 2015, 26, 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Lämsä T, Jin H, Mikkonen J, Laukkarinen J, Sand J, Nordback I, Pancreatology 2006, 6, 301; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Laukkarinen J, Nordback I, Mikkonen J, Kärkkäinen P, Sand J, Gastrointest. Endosc 2007, 65, 1063; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ang HY, Toong D, Chow WS, Seisilya W, Wu W, Wong P, Venkatraman SS, Foin N, Huang Y, Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chausse V, Schieber R, Raymond Y, Ségry B, Sabaté R, Kolandaivelu K, Ginebra M-P, Pegueroles M, Additive Manufacturing 2021, 48, 102392. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lusic H, Grinstaff MW, Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Jo S-H, Youn T-J, Koo B-K, Park J-S, Kang H-J, Cho Y-S, Chung W-Y, Joo G-W, Chae I-H, Choi D-J, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 2006, 48, 924; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) From AM, Al Badarin FJ, McDonald FS, Bartholmai BJ, Cha SS, Rihal CS, Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv 2010, 3, 351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hernandez Y, Lozano T, Morales AB, Navarro-Pardo F, Lafleur PG, Sanchez-Valdes S, Martinez-Colunga G, Morales-Zamudio L, de Lira-Gomez P, J. Compos. Mater 2017, 51, 373. [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Chia HN, Wu BM, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2015, 103, 1415; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gong J, Schuurmans CC, Genderen A. M. v., Cao X, Li W, Cheng F, He JJ, López A, Huerta V, Manríquez J, Nature communications 2020, 11, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shao G, Hai R, Sun C, Advanced Optical Materials 2020, 8, 1901646. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Janusziewicz R, Tumbleston JR, Quintanilla AL, Mecham SJ, DeSimone JM, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 201605271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Garbey M, Salmon R, Fikfak V, Clerc CO, Computers in Biology and Medicine 2016, 79, 259; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen HY, Koo B-K, Bhatt DL, Kassab GS, J. Appl. Physiol 2013, 115, 285; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gutiérrez-Chico JL, Regar E, Nüesch E, Okamura T, Wykrzykowska J, di Mario C, Windecker S, van Es G-A, Gobbens P, Jüni P, Circulation 2011, 124, 612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu X, Wang T, Chow LC, Yang M, Mitchell JW, International journal of polymer science 2014, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fu S-Y, Feng X-Q, Lauke B, Mai Y-W, Composites Part B: Engineering 2008, 39, 933. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lee S-Y, Kang I-A, Doh G-H, Yoon H-G, Park B-D, Wu Q, J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater 2008, 21, 209. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fatimi A, Zehtabi F, Lerouge S, Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2016, 104, 1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Woodard LN, Grunlan MA, ACS Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bergsma JE, Rozema F, Bos R, Boering G, De Bruijn W, Pennings A, Biomaterials 1995, 16, 267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Ronda N, Potì F, Palmisano A, Gatti R, Orlandini G, Maggiore U, Cabassi A, Regolisti G, Fiaccadori E, Vascul. Pharmacol 2013, 58, 39; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ren L, Wang P, Wang Z, Liu Y, Lv S, Mol. Med. Report 2017, 16, 4334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Johnson W Jr, Lloyd T, Victorica B, Zales V, Epstein M, Leff R, Ardinger R Jr, Slovis T, Johnson J, Marsters P, Pediatr. Cardiol 2001, 22, 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.