Abstract

Our objective was to determine if suckling neonatal piglets are susceptible to enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) O157:H7 disease. Surprisingly, EHEC O157:H7 caused more-rapid and more-severe neurological disease in suckling neonates than in those fed an artificial diet. Shiga toxin-negative O157:H7 did not cause neurological disease but colonized and caused attaching-and-effacing intestinal lesions.

Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains belong to a family of pathogenic E. coli (enterohemorrhagic E. coli [EHEC]) strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis, bloody or nonbloody diarrhea, and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome in humans (14). EHEC strains can be food-borne pathogens, and cattle are important reservoirs of EHEC O157:H7 strains (14).

All EHEC strains produce cytotoxins called Shiga toxins (Stx1 and Stx2), previously called Shiga-like toxins and alternately named verotoxins. These toxins are considered essential for EHEC virulence in humans (1). Many EHEC strains, including O157:H7 strains, can attach intimately to host cell membranes and efface microvilli and cytoplasm in a pattern referred to as an attaching-and-effacing (A/E) lesion (17). Intimin, an outer membrane protein encoded by the eae gene of EHEC (15), is required for intestinal colonization and for A/E activity of EHEC O157:H7 in piglets (7, 9, 12, 18, 19) and neonatal calves (7). We have hypothesized that vaccines directed against intimin may reduce transmission of EHEC O157:H7 and other A/E E. coli strains in food animals and in humans.

Although pigs have not been identified as a reservoir of EHEC O157:H7 strains, colostrum-deprived (CD), artificially reared piglets are useful models for studying the role of intimin in EHEC infections (7, 9, 18). The objective of this study was to determine if suckling neonatal piglets, like CD neonatal piglets, are susceptible to EHEC O157:H7 colonization and disease. If so, we plan to use suckling piglets in passive-immunization studies to determine if intimin-based vaccines can protect against experimental EHEC O157:H7 disease. A second objective was to determine if Stx is required for pathogenicity in suckling piglets, as it is in CD piglets (10–12).

Thirty-eight suckling piglets (>0.9 kg) naturally farrowed by four crossbred swine (gilts) at the National Animal Disease Center were allowed to suckle colostrum before inoculation. At 2 to 11 h after birth (after the youngest piglet had suckled colostrum), piglets were inoculated via a stomach tube with 1010 CFU of either a streptomycin-resistant mutant of Stx2-positive EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24 (30 piglets from three litters), or Stx-negative E. coli O157:H7 strain 87-23 (7, 16, 18, 21). Inocula were prepared and stored as described previously (6). Piglets were returned to the sow immediately after inoculation and observed clinically every 4 to 8 h. At necropsy, sections from the terminal ileum and cecum were collected and frozen at −80°C for bacteriological analysis. Sections of ileum, cecum, spiral colon, and distal colon were collected for histology. Brain and spinal cord (first 6 to 8 cm) were also collected for histology. Tissues were fixed in neutral buffered 10% formalin, processed by routine methods, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS) was used to detect microvascular damage in selected tissues. O157:H7 bacteria were identified by indirect immunoperoxidase staining (6). Sorbitol-negative O157:H7 bacteria were quantitated on sorbitol-MacConkey agar containing 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (strain 86-24) or no antibiotics (strain 87-23). Selected sorbitol-negative colonies were tested for O157:H7 antigens by a latex agglutination assay (6). Stx2 titers in blood from inoculated piglets were kindly determined by Nancy Cornick, as described previously (4). Blood samples were considered positive if the titer was >1:8 and if the cytotoxicity was neutralized by polyclonal antibody against Stx2.

Only 2 of the 30 suckling piglets inoculated with EHEC strain 86-24 had diarrhea at 22 h postinoculation. However, by 24 h after inoculation, 2 of the 30 piglets had died and 11 were in extremis with signs of central nervous system (CNS) disease and had to be euthanatized (Table 1). The condition of the remaining 17 piglets deteriorated rapidly. Two died and the remaining 15 had to be euthanatized by 36 h after inoculation. Signs of neurological disease included shivering and severe tremors, hind-leg weakness with signs of splayleg, paralysis of all legs, lateral recumbency, sternal or dorsal recumbency, paddling, squealing, and convulsions. Surprisingly, the incidence and severity of EHEC-induced clinical neurological signs were greater and these signs appeared earlier in suckling piglets than they do in CD piglets (6, 10, 13, 18). Diarrhea occurred less frequently in suckling piglets than it does in juvenile rabbits (20), mice (16), and CD calves or piglets (6, 7, 11, 12, 18, 22) inoculated with EHEC O157:H7 or Stx2 only. The presence of CNS signs in suckling piglets before they developed diarrhea may be evidence that Stx2 was absorbed before extensive intestinal damage occurred. None of eight suckling piglets inoculated with the Stx-negative O157:H7 strain 87-23 showed any neurological signs during the 48-h (four piglets) or 72-h (four piglets) duration of the experiment.

TABLE 1.

Findings in neonatal suckling piglets inoculated with 1010 CFU of E. coli O157:H7 strain 86-24 (Stx2 positive) or E. coli O157:H7 strain 87-23 (Stx negative)

| Strain | Duration (h) | No. tested | No. dead at:

|

No. euthanatized in extremis at:

|

No. with A/E bacteriaa in:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤24 h | 25–36 h | ≤24 h | 25–36 h | Ileum | Cecum | Spiral colon | Distal colon | |||

| 86-24 | 22–36 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 15 | 14 | 17 | 15 | 10 |

| 87-23 | 48–72 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2b | 7b | 8 | 5 |

A/E bacteria strained with E. coli O157:H7 antibody by immunoperoxidase technique.

Ileal and cecal tissues were collected from only seven piglets.

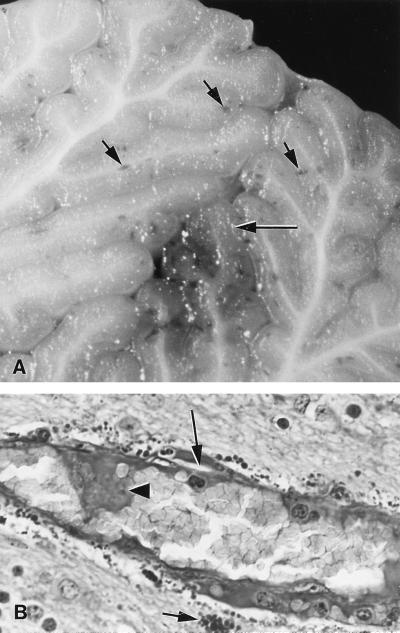

Lesions were seen in all suckling piglets inoculated with EHEC strain 86-24. These included subcutaneous edema, especially in the eyelids and conjunctiva, the forehead, and the prelumbar fossa (mild in 3 piglets, moderate in 5, and severe in 13); increased abdominal fluid and colonic edema (mild in 2, moderate in 10, and severe in 10); hyperemia in the ileum (3 piglets) or throughout the small intestine (1 piglet); hemorrhages in the gray and/or white matter of the cerebellum (5 piglets [Fig. 1A]) or on the meninges and in the white matter of the spinal cord; and focal symmetrical malacia of the dorsal columns (1 piglet). No such lesions were found in any of the piglets that received the nontoxigenic E. coli strain 87-23.

FIG. 1.

Photomicrographs of sections of cerebellum from a suckling piglet necropsied 24 h after inoculation with EHEC strain 86-24. (A) Unstained section showing macroscopic multifocal hemorrhages (short arrows) and necrosis (long arrow) in the medulla and granular layer. (B) PAS section showing endothelial swelling and endothelial necrosis (arrowhead) with subintimal protein insudation (long arrow) in an arteriole and severe perivascular droplet accumulations (short arrow).

The most striking histologic lesions in suckling piglets inoculated with EHEC strain 86-24 were found in the CNS. There was no inflammatory response, but hemorrhages were obvious in hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissues. Hemorrhages were most frequent and severe in the cerebellum. As shown in Table 2, the cerebellum was affected in all 25 suckling piglets from which CNS tissues were collected. Hemorrhages extended into the white matter and the cortex of some folia. Red blood cells and plasma penetrated into the granule layer and surrounded Purkinje cells, which were swollen and degenerate. Perivascular edema and focal malacia in association with perivascular accumulations of protein droplets were seen around arterioles, capillaries, or venules. The other four CNS sites were similarly affected in a majority of the piglets. Microvascular CNS lesions were more obvious when the PAS reaction was employed (Fig. 1B). Some capillaries were occluded by microthrombi or were collapsed and surrounded by PAS-positive droplets. None of the piglets inoculated with E. coli strain 87-23 had CNS lesions.

TABLE 2.

Histologic lesions in the CNSs of suckling neonatal piglets at 22 to 36 h after intragastric inoculation with 1010 CFU of EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24

| Tissue | No. examined | No. with histologic lesion score

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Medulla oblongata | 26 | 8 | 13 | 5 | 0 |

| Brain stem | 26 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 0 |

| Cerebrum | 25 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 2 |

| Cerebellum | 25 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 19 |

| Spinal cord | 22 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 0 |

All suckling piglets inoculated with either EHEC strain 86-24 or nontoxigenic strain 87-23 had A/E lesions containing O157:H7 bacteria and O157:H7 bacterial counts that were similar to those described for CD piglets (6). A/E lesions occurred more often in the cecum and spiral colon than in the ileum or distal colon (Table 1), and more inoculated bacteria were recovered from the cecum than from the ileum (geometric mean viable counts of 108 and 105 CFU/g of tissue, respectively). This clearly demonstrated that intestinal colonization and the A/E activity of EHEC O157:H7 in suckling piglets are independent of Stx production, as they are in mice (16) and neonatal calves (5).

Consistent with earlier evidence that Stx binds to erythrocytes (2–4), Stx2 was detected in the red cell fractions from the blood of 9 of 19 suckling piglets inoculated with EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24. The Stx2 titers ranged from 16 to 64. Stx was not detected in the blood from any of the piglets inoculated with the nontoxigenic strain 87-23.

Surprisingly, ingestion of colostrum did not protect neonatal suckling piglets from experimental EHEC infection but seemed to enhance the severity of EHEC-mediated systemic disease. Like piglets deprived of colostrum, piglets nursing the sow were colonized and developed A/E lesions and systemic disease after they were inoculated intragastrically with EHEC strain 86-24 (6, 10, 18). We cannot explain why EHEC strain 86-24 caused more-rapid and more-severe systemic disease in suckling piglets than it does in CD piglets (6, 8, 18). These discrepancies in the development of neurological lesions in piglets kept under different conditions deserve further attention.

This study showed that naturally farrowed suckling piglets, like CD piglets, can be used to study EHEC infection. The ability to use suckling piglets instead of CD piglets simplifies the porcine EHEC infection model and will facilitate passive-immunization studies. This study also established that (for humane purposes) the less virulent Stx-negative E. coli O157:H7 strain 87-23 can be used as the challenge strain for intimin vaccine studies.

(A preliminary account of this work was presented at the Virulence Mechanisms in Bacterial Pathogens meeting, Ames, Iowa, 12 to 15 September 1999, and at the Research Workers in Animal Disease Conference, Chicago, Ill., 7 to 10 December 1999.)

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by grant 97-35201-4578 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to Alison D. O'Brien and by grant R01A141328 from the National Institutes of Health to Harley W. Moon.

We thank Nancy Cornick and Sheridan Booher for measuring Stx in blood samples and S. A. Cooklin, M. I. Inbody, N. C. Lyon, R. W. Morgan, R. A. Schneider, and R. J. Spaete for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbus G S. Association of verotoxin-producing E. coli and verotoxin with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 1997;51:S-91–S-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bitzan M, Richardson S, Huang C, Boyd B, Petric M, Karmali M A. Evidence that verotoxins (Shiga-like toxins) from Escherichia coli bind to P blood group antigens of human erythrocytes in vitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3337–3347. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3337-3347.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd B, Tyrrell G, Maloney M, Gyles C, Brunton J, Lingwood C. Alteration of the glycolipid binding specificity of the pig edema toxin from globotetraosyl to globotriaosyl ceramide alters in vivo tissue targetting and results in a verotoxin 1-like disease in pigs. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1745–1753. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornick N A, Matise I, Samuel J E, Bosworth B T, Moon H W. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection: temporal and quantitative relationships among colonization, toxin production, and systemic disease. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:242–251. doi: 10.1086/315172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean-Nystrom E A, Bosworth B T, O'Brien A D, Moon H W. Bovine infection with Escherichia coli O157:H7. In: Stewart C S, Flint H J, editors. Escherichia coli O157 in farm animals. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1999. pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean-Nystrom E A, Bosworth B T, Cray W C, Jr, Moon H W. Pathogenicity of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the intestines of neonatal calves. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1842–1848. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1842-1848.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean-Nystrom E A, Bosworth B T, Moon H W, O'Brien A D. Escherichia coli O157:H7 requires intimin for enteropathogenicity in calves. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4560–4563. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4560-4563.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnenberg M S, Tacket C O, James S P, Losonsky G, Nataro J P, Wasserman S S, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Role of the eaeA gene in experimental enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:1412–1417. doi: 10.1172/JCI116717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnenberg M S, Tzipori S, McKee M L, O'Brien A D, Alroy J, Kaper J B. The role of the eae gene of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in intimate attachment in vitro and in a porcine model. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:1418–1424. doi: 10.1172/JCI116718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donohue-Rolfe A, Kondova I, Mukherjee J, Chios K, Hutto D, Tzipori S. Antibody-based protection of gnotobiotic piglets infected with Escherichia coli O157:H7 against systemic complications associated with Shiga toxin 2. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3645–3648. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3645-3648.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dykstra S A, Moxley R A, Janke B H, Nelson E A, Francis D H. Clinical signs and lesions in gnotobiotic pigs inoculated with Shiga-like toxin I from Escherichia coli. Vet Pathol. 1993;30:410–417. doi: 10.1177/030098589303000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis D H, Moxley R A, Andraos C Y. Edema disease-like brain lesions in gnotobiotic piglets infected with Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1339–1342. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1339-1342.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis D H, Collins J E, Duimstra J R. Infection of gnotobiotic pigs with an Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain associated with an outbreak of hemorrhagic colitis. Infect Immun. 1986;51:953–956. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.3.953-956.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. The epidemiology of infections caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7, other enterohemorrhagic E. coli and the associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 1991;13:60–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaper J B, Gansheroff L J, Wachtel M R, O'Brien A D. Intimin-mediated adherence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and attaching-and-effacing pathogens. In: Kaper J B, O'Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1998. pp. 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karpman D, Connell H, Svensson M, Scheutz F, Alm P, Svandborg C. The role of lipopolysaccharide and Shiga-like toxin in a mouse model of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:611–620. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knutton S. Attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. In: Gyles C L, editor. Escherichia coli in domestic animals and humans. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1994. pp. 567–591. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKee M L, Melton-Celsa A R, Moxley R A, Francis D H, O'Brien A D. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 requires intimin to colonize the gnotobiotic pig intestine and to adhere to HEp-2 cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3739–3744. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3739-3744.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKee M L, O'Brien A D. Investigation of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence characteristics and invasion potential reveals a new attachment pattern shared by intestinal E. coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2070–2074. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2070-2074.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizuguchi M, Tanaka S, Fujii I, Tanizawa H, Suzuki Y, Igarashi T, Yamanaka T, Takeda T, Miwa M. Neuronal and vascular pathology produced by verocytotoxin 2 in the rabbit central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;91:254–262. doi: 10.1007/s004010050423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarr P I, Neill M A, Clausen C R, Newland J W, Neill R J, Moseley S L. Genotypic variation in pathogenic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolated from patients in Washington, 1984–1987. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:344–347. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tzipori S, Chow C W, Powell H R. Cerebral infection with Escherichia coli O157:H7 in humans and gnotobiotic piglets. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:1099–1103. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.10.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]