Abstract

Adapting to the remote working environment has been one of the most visible challenges for many organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic. As employee creativity helps organizations’ survival and resilience during times of crisis, this study aims to examine the role of leadership communication, family-supportive leadership communication in particular, in fostering creativity among work-from-home employees. The current study specifically focuses on the mediating processes in this relationship and the moderating role of employees’ work-life segmentation preferences, using a survey of 449 employees who have worked from home during the COVID-19 outbreak. The results showed that employee-organization relationship (EOR) quality, positive affect, and work-life enrichment mediate the relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and employee creativity. The effects of family-supportive leadership communication on employees’ positive affect and work-life enrichment were more prominent for those who prefer to segment their work and lives. This paper concludes with a discussion of the theoretical and practical implications of these findings for leadership in organizational communication.

Keywords: COVID-19, creativity, family-supportive leadership, segmentation preference, employee-organization relationship, work-life enrichment, positive affect

As a result of the unprecedented coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, which began in 2020, more employees have been working from home than ever before. A nationwide survey showed that approximately 66% of employees had to work from home in 2020 at least part of the week due to the pandemic (Herhold, 2020). Such working conditions have challenged organizations, yielding various problems such as employees’ digital fatigue, mental health issues caused by social isolation, and work-life conflict problems (Sen et al., 2021). In particular, due to the lack of physical compartmentalization between work and family space, COVID-19 has brought additional work-life boundary-blurring for these employees (Sahay & Wei, 2021), and family distractions presented by the new work-from-home reality have become one of the most pressing management issues (Gratton, 2020). To address these issues, creative and novel approaches and solutions that help organizations to adapt and manage the new working environment effectively are particularly required (Tang et al., 2020). Research has suggested that employees’ creative ideas are valuable for enhancing organizations’ abilities to both adapt resiliently to difficult situations and grow and compete by responding to opportunities—abilities that enable organizations to maintain their competitive advantages (Amabile, 1988; Oldham & Cummings, 1996). Creating conditions that foster employees’ creativity during challenging times thus has become a key challenge for organizational leaders.

This study argues that leaders’ family-supportive communication plays an important role in facilitating creativity among work-from-home employees during the coronavirus crisis. Family-supportive leadership, referring to supervisory behaviors that enable employees to achieve a balance between their responsibilities at home and work (Thomas & Ganster, 1995), is a powerful form of interaction that fosters positive workplace outcomes such as enhanced job satisfaction, well-being, and work-life balance (Jang, 2009; Li & Bagger, 2011; McCarthy et al., 2013). It can thus be a viable and unique interpersonal resource that leaders can use to engender greater desire, particularly among work-from-home employees, to think creatively in crises by helping them manage work-life boundaries effectively. Although previous studies (e.g., Bagger & Li, 2014; Straub, 2012) have examined the implications of such leadership, they have mainly focused on its effects on employees’ attitudinal, behavioral, and health-related outcomes, and research investigating its impacts on creativity remains scarce. Thus, to enrich our understanding of the outcomes of family-supportive leadership communication, especially for working-from-home employees during the pandemic, we examine the link between family-supportive leadership and creativity. Grounded in the social exchange theory (SET), this study focuses specifically on the processes underlying this relationship including relationship building, positive affect, and work-life enrichment (WLE).

Additionally, given that the pandemic has blurred the boundaries between work and family, this study tests how individuals’ work-home segmentation preferences (i.e., desire to segment or integrate work and family domains) moderate the effects of family-supportive leadership on employees’ perceived quality of relationship with their organizations, positive affect, and WLE. It has been shown that the negative effects of unexpected work-life conflicts on employee outcomes depend on individual differences (Derks et al., 2016), and thus, it is likely that work-from-home employees’ experiences and needs may vary according to their segmentation preferences.

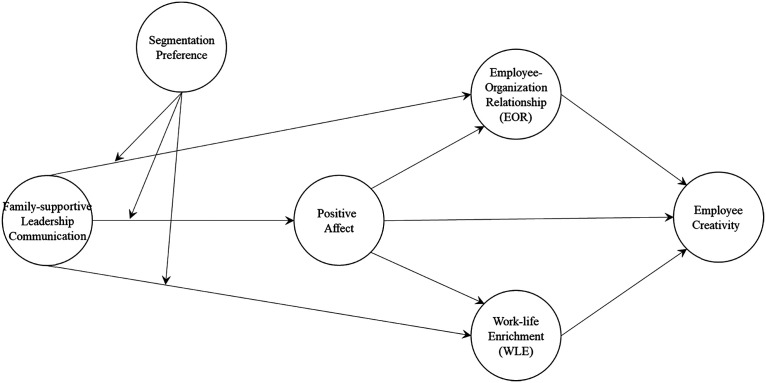

In sum, this study proposes an integrative model that investigates the effects of supervisors’ support for families on working-from-home employees’ creativity during the COVID-19 pandemic via three mechanisms (i.e., improving employee-organization relationship quality, fostering positive affect, and enriching work-life) and the moderating role of individuals’ segmentation preferences (Figure 1). This study provides much-needed theoretical insights on social exchange mechanisms regarding leaders’ communication roles in fostering creativity among work-from-home employees. The study also provides strategic guidelines that organizational leaders and communication practitioners can follow to manage employees’ work-life issues and enhance their creativity in remote work environments.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Literature Review

Employee Creativity

Defined as the generation of novel and useful ideas by employees, employee creativity is critical for employees’ performance as well as organizational effectiveness, success, and survival (Amabile, 1988). Although its relative importance may vary depending on the industry, the importance of creativity is not limited to particular occupations (Shalley et al., 2000). Prior studies have identified diverse factors at the individual and organizational levels that enhance employee creativity (Shalley & Gilson, 2004), and particularly highlighted the role of supportive behaviors by supervisors (Lee & Kim, 2021; Oldham & Cummings, 1996).

Fostering creativity among employees is especially important in crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. To remain competitive in crisis situations, organizations must adjust to new environments (e.g., holding virtual conferencing or establishing a remote reporting system) that may require new norms for work. Employees’ creative ideas and solutions can help organizations to be resilient by simultaneously managing new work systems effectively and continuing to achieve their goals during turbulent times.

Prior research has primarily focused on employees from certain industries that require high levels of creativity in their jobs or tasks (e.g., Ogbeibu et al., 2018). However, employees in almost every industry can supply creative ideas that improve the productivity and efficiency of their jobs (Shalley et al., 2000), and it is even more critical during a crisis where new approaches are valued for organizations to be resilient and adapt the new environment rapidly (Tang et al., 2020). An examination of the creativity of employees from a wide range of industries is thus vital, and effective communication intervention strategies can be critical to this process in times of crisis. Due to the high levels of uncertainty that accompany crises, employees may feel hesitant to share creative solutions or ideas as they have limited psychological resources to deal with the anxiety and strain associated with different outcome- and crisis-related risks (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000). Given that managerial support can provide employees with significant psychological resources (Shin & Zhou, 2003), which help facilitate creative performance (Ford, 1996), leaders or managers must take proactive approaches during crises to promote employee creativity.

Family-Supportive Leadership Communication

We suggest leadership communication as a key intervention that helps employees to be creative during a coronavirus crisis. Believing that communication is a core constitutive element of leadership (Fairhurst & Connaughton, 2014), communication scholars have espoused the communication-centered view of leadership and defined leadership communication as the process through which organizational leaders connect with and influence stakeholders (Harrison & Mühlberg, 2014). Public relations researchers have also theorized leadership communication as it plays a critical role in organizations’ internal communication (Lee & Kim, 2021). Given the context of the current study, we argue that, among various leadership communication behaviors, family-supportive leadership is of particular value for employees working from home due to COVID-19 since the pandemic has presumably increased the work and family life demands they experience (Larson et al., 2020).

Scholars have coined the term, supervisory family support, which refers to leadership behaviors that allow the employees to achieve a balance between their responsibilities at home and work (Thomas & Ganster, 1995). As one type of social support, family-supportive behaviors of supervisors are driven by their goodwill-based intentions to help employees balance work-family demands (Thompson et al., 1999), enabling them to adopt flexible work schedules that accommodate their family needs (Lapierre & Allen, 2006). Supervisors can serve as role models regarding the integration of work and family life by exhibiting family-supportive behaviors and assuaging employees’ concerns about possible negative career consequences (Thompson et al., 1999). Family-supportive supervisors frequently ask about employees’ family needs and express concerns and encouragement to subordinates who are strained by competition for resources from family and work (Bagger & Li, 2014). Drawing on previous studies, this study conceptualized family-supportive leadership communication as the level of support that employees believe they receive from their supervisors in terms of balancing their work-family demands.

Such leadership communication that blurs the line between employees’ work and life domains has been discussed in organizational communication literature. Scholars have highlighted leaders’ creative responses to employees’ diverse work-life needs in every action to create progressive work-life culture (Tracy & Rivera, 2010). Studies have also examined leaders’ role in identifying and changing work practices that negatively affect employees’ personal lives and work outcomes through collaboration with employees (Golden, 2009; Hoeven et al., 2017). Family-supportive leadership communication is particularly important for employees during the COVID-19 pandemic, regardless of their diverse family situations. It was found that one of the biggest challenges people experience while working from home were distractions from family and other household members and balancing work with other family duties (Gratton, 2020). Their family distractions during the pandemic include not only care demands for the children and spouses but also dependent and elder care for both married and unmarried individuals (Crain & Stevens, 2018). Leaders’ behaviors of supporting and caring for these diverse family issues that become more salient while working-from-home due to the pandemic are thus critical aspects of leadership communication practices.

It has been supported by empirical research that family support from supervisors reduces employees’ work-family conflicts (Hammer et al., 2009) and generates positive employee outcomes such as increased job satisfaction and low turnover intentions (Anderson et al., 2002; Li & Bagger, 2011). It also improves employees’ well-being and work-life balance (Jang, 2009; McCarthy et al., 2013). Limited research, however, examined whether and how family-supportive leadership communication increases employee creativity. In building a linkage between the two, the current study draws upon social exchange theory (SET: Blau, 1964). SET suggested that when employees receive socioemotional resources from their organizations, they build social exchange relationships, which are based on trust, interpersonal attachment, and long-term interactions (Shore et al., 2004). This social exchange relationship, in turn, triggers employees’ engagement in extra-role and pro-organizational behaviors as they feel obligated to return the benefits they receive. Previous studies have suggested that leaders’ actions are critical for developing social exchange relationships and determining their quality (e.g., Lee, 2021).

In this study’s context, we propose that family-supportive leadership communication provides employees with socioemotional resources—the quality of employee-organization relationship, employees’ positive affect at work, and work-life enrichment—which have been associated with employee creativity (Ong & Jeyaraj, 2014; Spreitzer et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2018). These may serve as critical mediators that encourage employees to reciprocate positively by being creative in their work while working remotely during the pandemic. Therefore, the next section of this paper delineates three social exchange mechanisms that may translate family-supportive leadership into employee creativity. Then, the moderating role of individuals’ segmentation preference is discussed.

The Mediating Role of Employee-Organization Relationship (EOR)

First, this study expects that family-supportive leadership communication facilitates employee creativity by building high-quality relationships between organizations and their employees. Scholars across various disciplines including business, human resource management, and public relations have studied employee-organization relationships (EOR)—“an overarching term to describe the relationship between the employee and the organization” (Shore et al., 2004, p. 29). Among its many conceptualizations, one widely adopted definition of EOR describes it as a relational quality between organizations and their employees, characterized by “the degree to which an organization and its employees trust one another, agree on who has the rightful power to influence, experience satisfaction with each other, and commit oneself to the other” (Men & Stacks, 2014, p. 307), which includes the four major components: trust, control mutuality, commitment, and satisfaction (Hon & Grunig, 1999).

Recognizing that, as representatives of organizations, leaders’ treatment of their subordinates influences how employees feel about their organizations, scholars have identified diverse types of leadership behaviors (e.g., authentic, empowering leadership) as critical antecedents of EOR (e.g., Lee et al., 2018; Men & Stacks, 2014). Employees often regard support from their supervisors as part of broader organizational efforts. Similarly, family-supportive leadership communication can elicit quality EORs because such behaviors demonstrate leaders’ supportiveness for and desire to enhance the work-life balance and well-being of their subordinates (Thompson et al., 1999). Due to its relationship-building function, family-supportive leadership thus enhances the quality of employee-organization relationships; when employees believe that their supervisors genuinely care about their well-being and allow them to meet their family needs without sacrificing their careers, employees will have positive perceptions of their organizations’ overall work environments and high-quality EORs may emerge (Bagger & Li, 2014).

EOR facilitates organizational effectiveness by helping organizations effectively achieve their goals (Hon & Grunig, 1999). As high-quality EORs develop, employees may feel obligated to reciprocate the relationship-building efforts they receive from their organizations. According to SET, employees who trust their organizations are more willing to work hard, expend energy (Yu et al., 2018), and engage in positive behaviors that benefit their organizations (Lee, 2021). One important way for employees to fulfill the sense of obligation they feel toward their organizations is to exhibit their creativity at work (Pan et al., 2020). Creativity, the production of new ideas or solutions, is relevant to the type of bond that individuals have with the organizations they belong to (Amabile, 1988). Previous studies provide evidence that high-quality EORs can promote innovative behavior and creativity among employees (e.g., Yu et al., 2018). Employees exert effort to fulfill their organizational obligations and responsibilities by generating and implementing ideas when their organizations invest substantially in them (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Thus, because favorable EORs motivate employees to reciprocate and maintain balanced exchanges with their organizations, they may play key roles in fostering employees’ creative behaviors during crises. Based on this line of reasoning, we predicted that family-supportive leadership communication would operate through EOR in facilitating creativity:

H1

The quality of EOR mediates the positive relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and employee creativity.

The Mediating Role of Work-Life Enrichment (WLE)

The fact that family-supportive leaders help employees achieve WLE may also help explain the effect of family-supportive leadership communication on creativity. Work and family life cannot be totally separated from each other. The resources earned from either area (i.e., work, life) can influence the quality of the other (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Defined as “the extent to which experiences in one role improve the quality of life in the other role” (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006, p. 72), WLE generally represents positive experiences’ transcendence between work and family life. According to Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012), positive experiences formed in one dimension of life develop as personal resources, whether physical, intellectual, or psychological, and spill over the boundary between work and family life. Carlson et al. (2006) identified three dimensions of WLE: development (i.e., gains of instrumental resources such as knowledge, skills, capabilities, and perspectives in employees’ work domains), affect (i.e., gains of positive emotional states that benefits employees’ non-work lives), and capital (i.e., gains of psychosocial resources such as confidence, accomplishment, self-fulfillment, security, and self-esteem that help employees better fulfill their life roles).

Previous research has shown that positive experiences at work influence self-efficacy (Chan et al., 2016), which further affects work-life balance and job and family satisfaction with heightened levels of work-to-family enrichment (Carlson et al., 2006). Working from home blurs the boundaries between family life and work and, as previously mentioned, supervisors’ family supportive behaviors can help employees better deal with family issues. The positive experiences employees obtain from supervisory family support in the work domain can accumulate as psychological resources in their lives and transfer back to their family life, enabling them to improve the quality of their family lives and achieve higher levels of WLE. Research has shown that the opportunity to discuss scheduling flexibility with their supervisor because of their non-work personal activities helps employees achieve higher levels of WLE (Carlson et al., 2006). Other scholars have also demonstrated that support from supervisors results in work-family enrichment because it helps employees feel satisfied with their job roles and improve their personal life experiences (Siu et al., 2015).

When enhanced by supervisors’ family support, WLE can foster employees’ creativity at work. Consistent with the main assumption of SET, prior research has suggested that the psychological resources gained from family-supportive leaders should transfer to employees’ maintenance of quality family lives and that the resources gleaned from such family lives are also expected to spill over to the workplace by helping employees translate their ideas into creative performance (Ford, 1996; Tang et al., 2017). Sonnentag (2003) showed that family-to-work enrichment enables employees to deal with different work more actively, energetically, and with greater levels of motivation, which results in better performance at work (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). As an important psychological resource that spills over from life, WLE can enhance employees’ energy levels and problem-solving abilities in their workplaces (Sonnentag et al., 2008), which in turn helps employees persist in their creative efforts (Atwater & Carmeli, 2009). Indeed, work-life harmony, a pleasant, harmonious arrangement of work and life roles, has been found to have a facilitative impact on employees’ creative performance at work (Ong & Jeyaraj, 2014). In sum, positive socioemotional resources—work and family life enrichment—employees obtain via family-supportive leadership communication motivate employees to reciprocate by being creative in their work. Based on this social exchange mechanism generated by family-supportive leaders, thus, we predicted that WLE would serve as a mediator that explains supervisory family support’s effect on employee creativity.

H2

Work-life enrichment mediates the positive relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and employee creativity.

The Mediating Role of Positive Affect

Family-supportive leadership communication also influences employee creativity by contributing to employees’ positive affect (“a pleasant feeling state or good mood”; Estrada et al., 1994, p. 286). Leadership communication has been believed to affect employees’ positive emotions at work (Men & Yue, 2019). Family supportive leaders reduce employees’ concerns about their work that could potentially sap their energy (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000) and their concerns about making unfavorable impressions on their supervisors due to family-related obligations (Regan, 1994). Thus, family-supportive leadership communication may elicit positive affective reactions from employees. Supporting this viewpoint, Lapierre and Allen (2006) showed that family-supportive supervision helps protect employees’ affective well-being at work.

Researchers have contended that positive affect stimulates creativity by influencing individuals’ cognitive activity (Clore et al., 1994). Positive emotions such as joy or love broaden individuals’ repertoires of cognitions and actions (Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005)—particularly, the scope of their attention by increasing the number of cognitive elements available for associations and the scope of their cognition by increasing the breadth of those elements that they can treat as relevant to a given problem. As a result, this mental activity leads to greater variation and prompts individuals to pursue novel, creative, and unscripted paths of thought and action. Miller (1997) provided a physiological explanation for the relationship between positive affect and creativity. Chemicals such as endorphins, epinephrine, and adrenalin released in the body when individuals are having fun increase their sense of well-being and energy, which elicits creative thinking accompanied by higher self-esteem. Positive affect also enhances social bonds and connectivity among employees, which makes them experience expansive emotional states that open possibilities for creativity, leading them to try new things (Spreitzer et al., 2005). More importantly, serving as a key job resource that helps employees to stay in a positive mood while working-from-home, family-supportive leaders fulfill the emotional and affective needs of employees in the workplace. As argued by SET, employees who receive emotional resources from family-supportive leaders are likely to commit themselves to organizations by being creative in their works. Based on this idea, we posed the following hypothesis:

H3

Positive affect mediates the positive relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and employee creativity.

In addition, positive emotions help individuals build high-quality relationships with others. In organizational settings, experiencing positive emotions broadens one’s awareness and thought-action repertoires by activating outward orientations, which in turn help build social resources such as relationships with coworkers or managers (Sekerka et al., 2012). Scholars have shown that employees’ affective experiences play crucial roles in developing and maintaining quality leader-member exchange relationships (Cropanzano et al., 2017). Similarly, positive affect may improve the quality of EORs, namely, employees’ feelings of trust, satisfaction, mutual control, and commitment toward their organizations. Men and Robinson (2018) empirically demonstrated that positive feelings at work such as joy, happiness, excitement, companionate love, affection, and warmth contribute to facilitating a favorable EOR. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H4

Positive affect mediates the positive relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and EOR.

Positive affect also serves as a pathway between positive experiences in one life domain and experiences of enrichment in other life domains (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Researchers have noted that employees’ experiences of positive affect at work are not limited to the work domain but generalize into overall higher levels of positive affect across life domains (Heller et al., 2004). This general positive affect helps employees to feel energized and to engage in other life domains outside work such as home (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). Positive emotions and affect experienced in one role (i.e., work) can be transferred to family (Wayne et al., 2006) as it enriches employees’ experiences in other roles (i.e., family) (Hanson et al., 2006). Therefore, we expected that high levels of positive affect at work would make employees function well in their family lives, leading us to propose the following hypothesis:

H5

Positive affect mediates the positive relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and work-life enrichment.

Segmentation Preference as a Moderator

In a modern society where work-related demands can easily encroach upon the family domain, individual employees have different preferences for managing their work-home lives. While some employees prefer to integrate their work and family domains, others prefer to segment the two domains as much as possible (Kossek & Lambert, 2004). This boundary management preference to either integrate or separate work and private roles, which is a psychological state that is rather stable over time (Rothbard et al., 2005), has been considered an active coping strategy that individuals can use to balance their work and family lives (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000). It has been shown that permeability and flexibility determine one’s role integration-segmentation (Ashforth et al., 2000). In other words, employees who prefer to create and maintain permeable and integrated boundaries are more likely to experience spillover across the work and family domains, while those who prefer impermeable and segmented boundaries seek to prevent the two domains from influencing each other by keeping them separate. Individuals with high work-home segmentation preference levels (hereafter referred to as segmenters) tend to suffer less from the negative work-family spillover caused by job stress or mistreatment in work at home because they can effectively sever affective and behavioral connections across the domains (Liu et al., 2013) and suppress work-related feelings at home (Xin et al., 2018). Individuals with low work-home segmentation preference levels (hereinafter referred to as integrators) appreciate interactions across the domains (Derks et al., 2016).

The current study proposes that the effects of family-supportive leadership communication on positive affect, EOR, and WLE described above will vary depending on individuals’ segmentation preferences. While facing unexpected and sudden changes in working environment, segmenters who began working from home due to the pandemic may likely experience more boundary violations between work and life than the integrators. Remote working causes work to intrude into family life and vice versa, and such boundary violations can especially lead to increased work-family conflicts and higher levels of stress and burnout particularly for employees who prefer to keep their work and family domains as separate as possible (Kreiner et al., 2009). Moreover, segmenters tend to perceive more failure to fulfill their roles in both domains when work-family conflicts occur unexpectedly (Zhang et al., 2019).

Hence, we assume that family-supportive leadership communication may be particularly effective for segmenters during the COVID-19, compared to integrators, by helping them to simultaneously accommodate their increased responsibilities and demands in both the work and family domains. Leaders’ genuine care and concern for such employees’ family demands and needs can provide them with the flexibility and permeability to fulfill the demands they face in both domains. The fulfillment of such demands is associated with WLE, which facilitates the approaches they take to working from home. Moreover, family-supportive leadership communication can help segmenters perceive their EORs as high quality and promote higher levels of positive affect while working-from-home. Segmenters are generally expected to feel more burnout than integrators because they experience unexpected and sudden difficulties in managing both their work and home roles at home. Active communication supervisors accommodate, listen to, and show concerns for such employees’ family-related obligations may elicit more positive reactions by ameliorating their burnout states and helping them feel satisfied with their companies. This is because such communication helps reduce employees’ work-related concerns and fully participate in family-activities without feeling guilty and concerned about making unfavorable impressions by attending to family matters (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Regan, 1994). The positive consequences of family-supportive leadership communication may thus be particularly strengthened for those who prefer to segment life and work. Based on this line of reasoning, we proposed the following hypotheses regarding the moderating effects of individuals’ segmentation preferences:

H6

Segmentation preference moderates the relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and EOR such that the relationship is stronger when the work-home segmentation preference level is high than when it is low.

H7

Segmentation preference moderates the relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and positive affect such that the relationship is stronger when the work-home segmentation preference level is high than when it is low.

H8

Segmentation preference moderates the relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and work-life enrichment such that the relationship is stronger when the work-home segmentation preference level is high than when it is low.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

An online survey with full-time employees across various industrial sectors 1 and organizational sizes in the United States was conducted using Qualtrics panels. The data were collected for a week in June 2020, during which most states had implemented stay-at-home orders, beginning with California in mid-March (Mervosh et al., 2020), and there were about 1.9 million confirmed cases (Elflein, 2020). Given the purpose of the study, the sample included only those who started working from home due to COVID-19, meaning that workers who had been working from home (i.e., teleworkers) before the COVID-19 outbreak were screened before the survey. To achieve a representative sample of U.S. employees according to the most recent U.S. census data, Qualtrics used quota when recruiting the participants in terms of gender, age, and race/ethnicity.

Of the 449 total participants (mean age = 35.82; SD = 10.14), 55.7% were male and the majority were White (65.9%). Most of the participants (94.4%) held bachelor’s degrees or higher. The income levels of the largest number of participants were between US$40,000 and US$59,999 (35.2%), followed by the US$60,000 to US$79,999 range (24.1%). A majority of the participants (64.6%) held management positions, followed by non-management positions (28.5%), and senior management positions (6.9%). The participants worked for organizations that varied in size from small- (4.2%), medium- (46.8%) to large-sized (27.2%) companies. About 39.4% of participants reported having worked for their current employers for 4–6 years, 29% for 1–3 years, and 15.1% for 6–8 years. The employers’ industries included information and telecommunications (21.8%), manufacturing (18.3%), finance and insurance (16.5%), construction (6.7%), professional, scientific, and technical services (5.8%), healthcare and social assistance (5.1%), and management of companies and enterprises (4.7%). Furthermore, 71.2% of participants responded that they had been working-from-home due to COVID-19 for more than 2 months. A total of 87% of them were currently married and 80.8% of them responded that they had at least one child in their household.

Measures

All the items used in the current study were adopted from previous literature adjusted to the current study’s context. Given the context of the current study, participants were asked to answer the questions for the items regarding their time working from home due to the COVID-19 outbreak, except for the measure of segmentation preference.

Employee Creativity

Five items adapted from Zhou and George (2001) were used to measure employee creativity. Items began with “While working-from-home, how often have you” and ended with each statement (e.g., suggested new and better ways of performing work tasks, came up with new and practical ideas to improve work performance, developed adequate plans and schedules for the implementation of new ideas, considered yourself as a good source of creative ideas, had a fresh approach to work-related problems). 7-point Likert scale was used, ranging from “1 = Never” to “7 = Always” (α = .80, M = 5.18, SD = 0.96).

Family-Supportive Leadership Communication

Family-supportive leadership communication was measured with six items adapted from previous studies (Clark, 2001; Thompson & Prottas, 2006). Participants were asked whether their direct supervisor/leader (1) listens when I talk about family issues, (2) understand my family needs, (3) acknowledges that I have obligations as a family member, (4) cares about the effects of work on family life, (5) supports my need to balance work and family issues, and (6) shows concerns for my family. They were measured with seven-point Likert scales ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree.” (α = .81, M = 5.38, SD = 0.93).

EOR

Measures for the quality of employee-organization relationship were adopted from Hon and Grunig (1999), comprised four second-level factors including trust (4 items; α = .76) (e.g., “My company treats employees like me fairly and justly”), control mutuality (3 items; α = .72) (e.g., “My company and an employee like me are attentive to what each other say”), commitment (3 items; α = .74) (e.g., “I feel that my company is trying to maintain a long-term commitment to employees like me”), and satisfaction (3 items; α = .71) (e.g., “I am happy with my company”). Seven-point Likert scale from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree” was used (α = .92, M = 5.38, SD = 0.88).

WLE

Work-life enrichment measures were adopted from Carlson et al. (2006) and a total of 16 items was used with 7-point Likert scale from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree” (α = .92, M = 5.31, SD = 0.83). It comprised three factors including development resources (6 items; α = .85) (e.g., “My involvement at work helps to develop my abilities and this helps me be a better family member”), affect resources (5 items; α = .81) (e.g., “My involvement at work helps to be in a good mood, and this helps me be a better family member”), and capital resources (5 items; α = .79) (e.g., “My involvement at work instills confidence in me, and this helps me be a better family member”).

Positive Affect

A total of 13 items was adopted from Van Katwyk et al. (2000) to measure positive affect. Items also began with “While working-from-home, how often have you felt” and ended with each emotion (e.g., satisfied, excited, energetic). This construct was also measured with 7-point Likert scales from “1 = Never” to “7 = Always” (α = .91, M = 5.23, SD = 0.96).

Segmentation preference

Individuals’ general segmentation preferences were measured with four items adopted from Kreiner (2006) with seven-point Likert scales ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “7 = strongly agree.” (α = .76, M = 5.32, SD = 0.95). Sample items include “In general, I prefer to keep work life at work.”

Controls

Based on the results of a series of ANOVA, t-tests, and regression analyses, participants’ gender, industry sectors, marital status, and the number of children were controlled.

Analysis

A two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis, including a test of the measurement model using CFA followed by an assessment of the structural model, was performed using Mplus program. Hu and Bentlers’ (1999) joint-criteria, either CFI ≥.95 and SRMR ≤.10 or RMSEA ≤.06 and SRMR ≤.10, was used to assess the model fits.

Results

Testing the Measurement Model

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and zero-order Pearson correlations of all of the main variables. The CFA results showed that the measurement model fit the data well: χ2 (1462) = 3689.981, RMSEA = .058 [.056, .061], CFI = .954, TLI = .945, SRMR = .044. All factor loading values were significant and higher than the threshold value of 0.6 (p < .001). The composite reliabilities (CR) for all variables ranged from .83 to .93, demonstrating good internal consistency. In addition, as the values of the average of variance extracted (AVE) were greater than .5 and the square root values of AVE were greater than the construct correlations, convergent and discriminant validity of the measures were shown to be satisfactory. We thus proceeded with the structural model testing.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables.

| M (SD) | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Employee creativity | 5.18 (0.96) | .80 | — | |||||

| 2. Family supportive leadership communication | 5.38 (0.93) | .81 | .51* | — | ||||

| 3. Employee-organization relationship | 5.38 (0.88) | .92 | .55* | .68* | — | |||

| 4. Work-life enrichment | 5.31 (0.83) | .92 | .56* | .53* | .59* | — | ||

| 5. Positive affect | 5.23 (0.96) | .91 | .57* | .48* | .51* | .64* | — | |

| 6. Segmentation preference | 5.32 (0.95) | .76 | .35* | .48* | .53* | .46* | .41* | — |

| *P < .01 | ||||||||

Structural and Alternative Model Testing

The hypothesized model fits the data well: χ2 (1307) = 3266.541, RMSEA = .058 [.055, .060], CFI = .954, TLI = .946, SRMR = .044. To assess the theoretical validity of the conceptual model, we compared the baseline model with other alternative models that include different flows of theoretical hierarchy among latent variables (Hair et al., 2006). Given that relationship and work-life enrichment lead to positive affect at work (Wepfer et al., 2018), the first alternative model included the direct effects from EOR and WLE on positive affect. It performed significantly worse than the proposed model (χ2 (1307) = 3435.939, RMSEA = .070 [.067, .074], CFI = .926, TLI = .920, SRMR = .089) (Δχ2 = 169.40, p < .001). Similarly, the second alternative model that reverse the sequence of the variables (the effect of creativity on family-supportive leadership communication via EOR, WLE, and positive affect) did not show a significantly better model fit than the baseline model (χ2 (1308) = 3627.357, RMSEA = .089 [.076, .091], CFI = .900, TLI = .891, SRMR = .112) (Δχ2 = 360.82, p < .001). In the third alternative model, we added a direct path from leadership communication to creativity that has been demonstrated in previous studies. The alternative model (χ2 (1306) = 3435.928, RMSEA = .065 [.054, .071], CFI = .933, TLI = .923, SRMR = .061) was not significantly better than the baseline model (Δχ2 = 169.39, p < .001). The distinctiveness and theoretical foundation of the hypothesized model was supported, and thus, was selected as the final model. We then interpreted the path coefficients (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Results of the hypothesized model.

Hypotheses Testing

In H1, we predicted that EOR would play a mediating role in the relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and employee creativity. Family-supportive leadership communication had a significant direct effect on EOR (.892, p < .001), and EOR significantly increased employee creativity (.147, p = .014). The results of a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure (N = 5,000) with 95% confidence interval suggested that the indirect effect was also significant (.131, p = .014, 95% CI [.102, .276]). Thus, H1 was supported.

H2 tested the mediation effect of WLE. Family-supportive leadership communication positively and significantly influenced WLE (.591, p < .001), and WLE significantly increased employee creativity (.323, p < .001), with a significant mediating effect (.191, p < .001, 95% CI [.092, .288]). Therefore, H2 was supported. H3 examined the indirect effect of family-supportive leadership communication on employee creativity through positive affect. The analysis showed positive and significant direct effects between family-supportive leadership communication and positive affect (.589, p < .001) and between positive affect and employee creativity (.483, p < .001). The indirect effect was also significant (.285, p < .001, 95% CI [.214, .364]). Thus, H3 was supported. Regarding H4-H5, positive affect did not have a significant direct effect on EOR (.047, p = .296), but it had a significant direct effect on WLE (.356, p < .001). In line with this, the path from family-supportive leadership communication to EOR via positive affect was insignificant (.028, p = .285, 95% CI [-.030, .136]), meaning H4 was not supported. Meanwhile, the analysis showed a significant indirect effect in the path from family-supportive leadership communication to WLE through positive affect (.210, p < .001, 95% CI [.135, .259]), supporting H5.

H6–H8 concerned the moderating effects of employees’ segmentation preference. The results showed that the interaction term (work-home segmentation preference x family-supportive leadership communication) in the model was positively and significantly related to positive affect (.131, p = .002) and WLE (.108, p = .001), while it was not related to EOR (−.041, p = .186). Following Aiken et al.’s (1991) suggestion, the interaction pattern was further estimated by testing the nexuses between family-supportive leadership and positive affect and between family-supportive leadership and WLE at high and low (one SD above and below the mean respectively) segmentation preference levels. As Figure 3 shows, family-supportive leadership communication increased positive affect to a greater degree when segmentation preferences were high (simple slope = 0.519, p < .001) than when they were low (simple slope = 0.319, p < .001). Family-supportive leadership communication also increased WLE (see Figure 4) to a greater degree when segmentation preferences were high (simple slope = 0.588, p < .001) than when they were low (simple slope = 0.414, p < .001). Thus, H6 was rejected, while H7 and H8 were supported.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of segmentation preference in the relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and positive affect.

Figure 4.

Moderating effect of segmentation preference in the relationship between family-supportive leadership communication and work-life enrichment.

Discussion

Grounded in SET, the current study examined the mechanisms through which family-supportive leadership communication influences the creativity of work-from-home employees in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of the analysis suggest that family-supportive leadership communication leads to better EOR quality, WLE, and positive affect, which in turn increases employees’ creativity. Family-supportive leadership communication and employees’ segmentation preferences had a positive joint effect on positive affect at work and WLE. These findings have significant theoretical and practical implications in organizational communication.

This study is among the first to empirically investigate the link between family-supportive leadership communication and creativity. Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of various types of leadership in fostering employee creativity (e.g., Lee & Kim, 2021), but research examining family-supportive leadership behaviors remains scarce. In the context of COVID-19, the results of the current study demonstrate that leaders’ supportiveness for subordinates’ family issues is a crucial element in potentially improving employees’ creativity, which is a key asset for organizational resilience during a crisis. The fact that employee creativity improves organizations’ resilience and helps them effectively solve unexpected problems, address issues, and eventually build competitive advantage (Oldham & Cummings, 1996) demonstrates the importance of family-supportive leadership communication, especially for work-from-home employees during the pandemic who may face unexpected work-life conflicts and demands due in crises.

This study’s examination of three mechanisms—the quality of EOR, employees’ positive affect, and WLE revealed the positive effect of family-supportive leadership communication on creativity. From a social exchange perspective, this study viewed family-supportive leadership communication as an essential socioemotional resource that can foster employees’ trusting and nurturing relationships with their organizations, balanced and enriching work and family life, as well as their positive emotions. This study identified positive emotion as a key proximate outcome of family-supportive leadership communication and delineates the subsequent social exchange mechanisms, in the form of EOR and WLE, which translated leadership communication into creativity during the COVID-19 crisis period. Family-supportive leadership communication fulfills the emotional, relational, and family needs in the workplace. To reciprocate these benefits they receive from the leaders, employees are motivated to pay back to their organization by exhibiting creativity in their work. This study thus enhances the theoretical proposition of SET to understand the motivations of creativity during the pandemic and contributes to the scholarly understanding of the dynamics of the leader support-creativity link by answering the question of how supervisors’ family support leads to creativity.

The role of positive affect was notable in this study. The effect of family-supportive leadership communication on WLE was partially mediated by positive affect. In other words, family-supportive leadership communication evokes positive emotions in employees positive at work, which in turn spillover into their families. However, this positive affect does not necessarily relate to how much they trust, are satisfied with, or committed to their companies. This result may partially derive from the COVID-19 context of the study. The ways organizations or leaders effectively handle this crisis and the extent to which individuals are satisfied with their actions may exert a stronger influence on employees’ perceptions of their relationships with their companies.

Our findings are particularly valuable given that this study only focused on “newly” remote employees whom the pandemic had partially forced to work from home. A rich body of literature has examined the importance of leadership communication and teleworkers’ productivity and engagement (e.g., Gibson et al., 2002). Teleworkers oftentimes volunteer to work at home to meet their own needs or because of their job characteristics (Golden et al., 2006). Admittedly, teleworkers who had been working at home before the pandemic could also likely be impacted by the stay-at-home work orders, causing work-home boundaries to be violated. Our study is among the first empirical attempts to test the effectiveness of leadership communication, focusing only on newly emerged remote workers in the midst of COVID-19 whose organizations asked them to work from home. These employees may have faced unexpected work- and family-related demands, which could have reduced their levels of productivity and their morale. With their experiences of the benefits and challenges of working-from-home, they may have altered their perceptions of the new norm of the workplace environment. This could be another issue that organizations should manage to meet their new expectations (e.g., hybrid work format) and improve the effectiveness and productivity of employees during and after the pandemic. By building a comprehensive model focusing on such employees, the current study explicates the implications of family-supportive leadership communication as an interpersonal and socio-emotional resource for these emerging types of workers and provides insights regarding ways to effectively manage work-from-home employees’ work-life issues during crises and boost their creativity in remote working environments.

Finally, this study also showed that people’s boundary management preferences, which reflect how they regard their work and family roles, can also impact their positive affect and WLE in response to family-supportive leadership communication. Specifically, family-supportive leadership communication turned out to be more effective in enhancing positive affect and enriching work-life boundaries for segmenters who prefer to segment their work from their lives than for integrators. The analysis showed no significant difference between the two in terms of EOR. These findings suggest that segmenters are especially vulnerable to newly remote working environments caused by the pandemic because they are more likely to perceive the situation as a threat to their family-related roles and identities and to experience high levels of work-to-family guilt when work-to-family conflicts inevitably occur (Zhang et al., 2019). Likewise, their work identities and boundaries may have been impacted, which could threaten their family roles. By providing empirical evidence that supervisory support for such employees’ family concerns is even more critical for enriching their work-life boundaries and eliciting positive affect, the current study highlights the importance of individuals’ boundary preferences in managing work-from-home employees effectively. Moreover, it sheds light on organizational communication scholarship (e.g., Golden, 2009; Hoeven et al., 2017; Tracy & Rivera, 2010) by showing when and why domain-crossing leadership communication between work and home lives matter based on individuals’ predisposition.

This study’s findings are valuable in practice as well. The blurred boundaries between work and family may cause employees to experience high demands in both domains while working from home. To mitigate increasing needs and potentially encourage employees to share creative ideas that may help organizations effectively overcome crises, organizational leaders and managers should exhibit their supportiveness, especially for the employees’ families. For example, leaders should respect and understand employees’ different family situations and needs through active interactions and discussion, using family-friendly language, and showing genuine care and concerns for family issues. Work-to-family conflicts may be inevitable during such times, and such efforts will help employees not only feel positive while working and trust their companies, but also perceive work demands as less of a threat to their family roles, which will enrich their family lives. These positive states toward both work and home will eventually enable them to exhibit creativity at work, which may prove critical for their organizations’ resilience in crises. This study’s analysis showed that family-supportive leadership communication is particularly effective for people with high segmentation preference levels in increasing positive affect and WLE, which in turn boosts creativity. Taking this into account, managerial training regarding the benefits of family support of employees may be a key intervention. Training should highlight the importance of identifying employees who prefer to segment their work and life and of frequently and proactively communicating and listening to the family-related concerns, needs, and interests of these employees when they are working from home.

Limitations and Future Studies

This study had several limitations that future research should seek to address. First, the demographics of the study participants varied; the study analyzed data of employees who were both married and unmarried and who had and did not have children. Although we controlled the variables in the model, individuals’ family demographic variables may significantly affect their work-life demands and the effectiveness of family-supportive leadership communication. Similarly, gender differences also exist. Given that women, especially women with children, are more likely to suffer emotionally than men during pandemics (Lyttelton et al., 2020), future studies could focus on specific groups of remote workers (e.g., working moms) to enrich our understanding of the dynamics of the work-from-home environment after the pandemic. Furthermore, our participants included workers in the U.S. from different organizations and industries, and most were White and highly educated. Thus, it was hard to identify the differences between types of workers (e.g., white-collar vs blue-collar workers) and the perspectives of minorities (e.g., people of color) may be underrepresented. Caution thus should be exercised in generalizing from our study samples. Finally, during the data collection period, participants’ levels of familiarity with remote working environments may have varied due to differing lengths of their working-from-home experiences. One possible issue is that family-supportive leadership communication may have been particularly important in the early stages of the pandemic when individuals’ unexpected family demands were high. Other research methods such as experimental or longitudinal designs could thus be employed in future studies to provide larger implications for the effectiveness of such leadership communication in the working-from-home environment going forward.

Author Biographies

Yeunjae Lee (PhD, Purdue University) is an assistant professor in the Department of Strategic Communication at University of Miami. Her main research interests include employee communication, internal issue/crisis management, and organizational diversity and justice.

Jarim Kim (PhD, University of Maryland, 2014) is an associate professor in the department of communication at Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea. Her research interests include public segmentation, activism, and crisis communication.

Notes

The current study did not particularly focus on the “creative” industries such as art, music, and architecture because employee creativity can exhibit in almost any occupation (Shalley et al., 2000) and creativity in their jobs and tasks is particularly important during the pandemic to help organizations to adapt to the new working environment (Tang et al., 2020).

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Yonsei University Research Grant of 2022 (2022-22-0180).

ORCID iDs

Yeunjae Lee https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2482-435X

Jarim Kim https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2973-9656

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G., Reno R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 123–167. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. E., Coffey B. S., Byerly R. T. (2002). Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: Links to work-family conflict and job-related outcomes. Journal of Management, 28(6), 787–810. 10.1177/014920630202800605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth B. E., Kreiner G. E., Fugate M. (2000). All in a day's work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. 10.5465/amr.2000.3363315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atwater L., Carmeli A. (2009). Leader–member exchange, feelings of energy, and involvement in creative work. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 264–275. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.07.00 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagger J., Li A. (2014). How does supervisory family support influence employees’ attitudes and behaviors? A social exchange perspective. Journal of Management, 40(4), 1123–1150. 10.1177/0149206311413922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blau P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson D. S., Kacmar K. M., Wayne J. H., Grzywacz J. G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work-family interface: Development and validation of a work–family enrichment scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(1), 131–164. 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan X. W., Kalliath T., Brough P., Siu O. L., O’Driscoll M. P., Timms C. (2016). Work-family enrichment and satisfaction: The mediating role of self-efficacy and work-life balance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(15), 1755–1776. 10.1080/09585192.2015.1075574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S. C. (2001). Work cultures and work/family balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(3), 348–365. 10.1006/jvbe.2000.1759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clore G. L., Schwarz N., Conway M. (1994). Affective causes and consequences of social information processing. In Wyer R. S., Srull T. K. (Eds), Handbook of social cognition: Basic processes; Applications (pp. 323–417). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Crain T. L., Stevens S. C. (2018). Family‐supportive supervisor behaviors: A review and recommendations for research and practice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 869–888. 10.1002/job.2320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano R., Dasborough M. T., Weiss H. M. (2017). Affective events and the development of leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Review, 42(2), 233–258. 10.5465/amr.2014.0384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano R., Mitchell M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. 10.1177/0149206305279602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derks D., Bakker A. B., Peters P., van Wingerden P. (2016). Work-related smartphone use, work–family conflict and family role performance: The role of segmentation preference. Human Relations, 69(5), 1045–1068. 10.1177/0018726715601890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. R., Rothbard N. P. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 178–199. 10.5465/amr.2000.2791609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elflein J. (2020). Number of cumulative cases of coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States from January 22 to August 17, 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103185/cumulative-coronavirus-covid19-cases-number-us-by-day/ [Google Scholar]

- Estrada C. A., Isen A. M., Young M. J. (1994). Positive affect improves creative problem solving and influences reported source of practice satisfaction in physicians. Motivation and Emotion, 18(4), 285–299. 10.1007/BF02856470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairhurst G. T., Connaughton S. L. (2014). Leadership: A communicative perspective. Leadership, 10(1), 7–35. 10.1177/1742715013509396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S., Moskowitz J. T. (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist, 55(6), 647–654. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. M. (1996). A theory of individual creative action in multiple social domains. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 1112–1142. 10.5465/amr.1996.9704071865 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. L., Branigan C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19(3), 313–332. 10.1080/02699930441000238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J. W., Blackwell C. W., Dominicis P., Demerath N. (2002). Telecommuting in the 21st century: Benefits, issues, and a leadership model which will work. Journal of Leadership Studies, 8(4), 75–86. 10.1177/107179190200800407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golden A. G. (2009). Employee families and organizations as mutually enacted environments: A sensemaking approach to work—life interrelationships. Management Communication Quarterly, 22(3), 385–415. 10.1177/0893318908327160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golden T. D., Veiga J. F., Simsek Z. (2006). Telecommuting's differential impact on work-family conflict: Is there no place like home? Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1340. 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton L. (2020). How to help employees work from home with kids. MIT sloan management review. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-to-help-employees-work-from-home-with-kids/ [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus J. H., Powell G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. 10.5465/amr.2006.19379625 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J. F., Black W.C., Babin B. J., Anderson R.E., Tatham R. L. (Eds), (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer L. B., Kossek E. E., Yragui N. L., Bodner T. E., Hanson G. C. (2009). Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). Journal of Management, 35(4), 837–856. 10.1177/0149206308328510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson G. C., Hammer L. B., Colton C. L. (2006). Development and validation of a multidimensional scale of perceived work-family positive spillover. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(3), 249. 10.1037/1076-8998.11.3.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison E. B., Mühlberg J. (2014). Leadership communication: How leaders communicate and how communicators lead in the today's global enterprise. Business Expert Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heller D., Watson D., Ilies R. (2004). The role of person versus situation in life satisfaction: A critical examination. Psychological Bulletin, 130(4), 574. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herhold K. (2020). Working from home during the coronavirus pandemic: The state of remote work. Clutch. https://clutch.co/real-estate/resources/state-of-remote-work-during-coronavirus-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- Hoeven C. L., Miller V. D., Peper B., Dulk L. (2017). The work must go on”: The role of employee and managerial communication in the use of work-life policies. Management Communication Quarterly, 31(2), 194–229. 10.1177/0893318916684980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon L. C., Grunig J. E. (1999). Guidelines for measuring relationships in public relations. Gainesville, FL: Institute for Public Relations, Commission on PR Measurement and Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S. J. (2009). The relationships of flexible work schedules, workplace support, supervisory support, work-life balance, and the well-being of working parents. Journal of Social Service Research, 35(2), 93–104. 10.1080/01488370802678561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kossek E. E., Lambert S. J. (Eds), (2004). Work and life integration: Organizational, cultural, and individual perspectives. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner G. E. (2006). Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27(4), 485–507. 10.1002/job.386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner G. E., Hollensbe E. C., Sheep M. L. (2009). Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work-home interface via boundary work tactics. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 704–730. 10.5465/amj.2009.43669916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre L. M., Allen T. D. (2006). Work-supportive family, family-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: Implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(2), 169–181. 10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson B. Z., Vroman S. R., Makarius E. E. (2020). A guide to managing your (newly) remote workers. In Harvard business review. https://hbr.org/2020/03/a-guide-to-managing-your-newly-remote-workers [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. (2021). Linking internal CSR with the positive communicative behaviors of employees: The role of social exchange relationships and employee engagement. Social Responsibility Journal, 18(2), 348–367. 10.1108/SRJ-04-2020-0121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Kim J. (2021). Cultivating employee creativity through strategic internal communication: The role of leadership, symmetry, and feedback seeking behaviors. Public Relations Review, 47(1), 101998. 10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101998 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Mazzei A., Kim J. N. (2018). Looking for motivational routes for employee-generated innovation: Employees’ scouting behavior. Journal of Business Research, 91, 286–294. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.06.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Bagger J. (2011). Walking in your shoes: Interactive effects of child care responsibility difference and gender similarity on supervisory family support and work-related outcomes. Group & Organization Management, 36(6), 659–691. 10.1177/1059601111416234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Kwan H. K., Lee C., Hui C. (2013). Work-to-family spillover effects of workplace ostracism: The role of work-home segmentation preferences. Human Resource Management, 52(1), 75–93. 10.1002/hrm.21513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyttelton T., Zang E., Musick K. (2020). Gender differences in telecommuting and implications for inequality at home and work. 10.31235/osf.io/tdf8c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy A., Cleveland J. N., Hunter S., Darcy C., Grady G. (2013). Employee work-life balance outcomes in Ireland: A multilevel investigation of supervisory support and perceived organizational support. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(6), 1257–1276. 10.1080/09585192.2012.709189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Men L. R., Robinson K. L. (2018). It’s about how employees feel! examining the impact of emotional culture on employee–organization relationships. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 23(4), 470–491. 10.1108/CCIJ-05-2018-0065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Men L. R., Stacks D. (2014). The effects of authentic leadership on strategic internal communication and employee-organization relationships. Journal of Public Relations Research, 26(4), 301–324. 10.1080/1062726X.2014.908720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Men L. R., Yue C. A. (2019). Creating a positive emotional culture: Effect of internal communication and impact on employee supportive behaviors. Public Relations Review, 45(3), 101764. 10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mervosh S., Lu D., Swales V. (2020). See which states and cities have told residents to stay at home. The New York times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-stay-at-home-order.html [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. (1997). All work and no play may be harming your business. Management Development Review, 10(6/7), 254–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbeibu S., Senadjki A., Gaskin J. (2018). The moderating effect of benevolence on the impact of organisational culture on employee creativity. Journal of Business Research, 90, 334–346. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.05.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham G. R., Cummings A. (1996). Employee creativity: Personal and contextual factors at work. Academy of Management Journal, 39(3), 607–634. 10.5465/256657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ong H. L. C., Jeyaraj S. (2014). Work-life interventions: Differences between work-life balance and work-life harmony and its impact on creativity at work. Sage Open, 4(3), 2158244014544289. 10.1177/2158244014544289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W., Sun L. Y., Lam L. W. (2020). Employee–organization exchange and employee creativity: A motivational perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(3), 385–407. 10.1080/09585192.2017.1331368 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regan M. (1994). Beware the work/family culture shock. Personnel Journal, 73(1), 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard N. P., Phillips K. W., Dumas T. L. (2005). Managing multiple roles: Work-family policies and individuals’ desires for segmentation. Organization Science, 16(3), 243–258. 10.1287/orsc.1050.0124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay S., Wei W. (2021). Work-family balance and managing spillover effects communicatively during COVID-19: Nurses’ perspectives (pp. 1–10). Health Communication. 10.1080/10410236.2021.1923155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekerka L. E., Vacharkulksemsuk T., Fredrickson B. L. (2012). Positive emotions: Broadening and building upward spirals of sustainable development. In The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 168–177). 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734610.013.0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sen P., Deb P., Kumar N. (2021). The challenges of work from home for organizational design. California Review Management. https://cmr.berkeley.edu/2021/07/the-challenges-of-work-from-home-for-organizational-design/ [Google Scholar]

- Shalley C. E., Gilson L. L. (2004). What leaders need to know: A review of social and contextual factors that can foster or hinder creativity. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 33–53. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalley C. E., Gilson L. L., Blum T. C. (2000). Matching creativity requirements and the work environment: Effects on satisfaction and intentions to leave. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 215–223. 10.5465/1556378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. J., Zhou J. (2003). Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 703–714. 10.5465/30040662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shore L. M., Tetrick L. E., Taylor M. S., Coyle-Shapiro J., Liden R. C., McLean-Parks J. (2004). The employee-organization relationship: A timely concept in a period of transition. In Martocchio J. J. (Ed), Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management (pp. 291–370). Amsterdam: Elsevier. 10.1016/S0742-7301(04)23007-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siu O. L., Bakker A. B., Brough P., Lu C. Q., Wang H., Kalliath T., Timms C. (2015). A three-wave study of antecedents of work-family enrichment: The roles of social resources and affect. Stress and Health, 31(4), 306–314. 10.1002/smi.2556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 518–528. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag S., Binnewies C., Mojza E. J. (2008). Did you have a nice evening?” A day-level study on recovery experiences, sleep, and affect. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 674. 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer G., Sutcliffe K., Dutton J., Sonenshein S., Grant A. M. (2005). A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science, 16(5), 537–549. 10.1287/orsc.1050.0153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straub C. (2012). Antecedents and organizational consequences of family supportive supervisor behavior: A multilevel conceptual framework for research. Human Resource Management Review, 22(1), 15–26. 10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C., Ma H., Naumann S. E., Xing Z. (2020). Perceived work uncertainty and creativity during the covid-19 pandemic: The roles of Zhongyong and creative self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3008. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.596232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Huang X., Wang Y. (2017). Good marriage at home, creativity at work: Family-work enrichment effect on workplace creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(5), 749–766. 10.1002/job.2175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Brummelhuis L. L., Bakker A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work-home interface: The work-home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556. 10.1037/a0027974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas L. T., Ganster D. C. (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(1), 6–15. 10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. A., Beauvais L. L., Lyness K. S. (1999). When work-family benefits are not enough: The influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(3), 392–415. 10.1006/jvbe.1998.1681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. A., Prottas D. J. (2006). Relationships among organizational family support, job autonomy, perceived control, and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(1), 100–118. 10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy S. J., Rivera K. D. (2010). Endorsing equity and applauding stay-at-home moms: How male voices on work-life reveal aversive sexism and flickers of transformation. Management Communication Quarterly, 24(1), 3–43. 10.1177/0893318909352248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Katwyk P. T., Fox S., Spector P. E., Kelloway E. K. (2000). Using the Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale (JAWS) to investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 219–230. 10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne J. H., Randel A. E., Stevens J. (2006). The role of identity and work-family support in work-family enrichment and its work-related consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(3), 445–461. 10.1016/j.jvb.2006.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wepfer A. G., Allen T. D., Brauchli R., Jenny G. J., Bauer G. F. (2018). Work-life boundaries and well-being: Does work-to-life integration impair well-being through lack of recovery? Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(6), 727–740. 10.1007/s10869-017-9520-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xin J., Chen S., Kwan H. K., Chiu R. K., Yim F. H. K. (2018). Work-family spillover and crossover effects of sexual harassment: The moderating role of work-home segmentation preference. Journal of Business Ethics, 147(3), 619–629. 10.1007/s10551-015-2966-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M. C., Mai Q., Tsai S. B., Dai Y. (2018). An empirical study on the organizational trust, employee-organization relationship and innovative behavior from the integrated perspective of social exchange and organizational sustainability. Sustainability, 10(3), 864. 10.3390/su10030864 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Zhao K., Korabik K. (2019). Does work-to-family guilt mediate the relationship between work-to-family conflict and job satisfaction? Testing the moderating roles of segmentation preference and family collectivism orientation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103321. 10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., George J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 682–696. 10.5465/3069410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]