Abstract

Our previous study reported that chronic exposure to sublethal levels of estrogen induces DNA damage and endocrine dysfunction in sea bass. In this study, we extended our hypothesis to test changes in genotoxicity and biotransformation induced by Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) that may regulate endocrine disorders in the estuarine fish. Therapon jarbua an euryhaline fish was exposed to BaP at two different ambient concentrations for 21 days. Biomarkers such as ethoxyresorufin-O-deethlylase (EROD) and DNA damages were assessed in the gill and liver, while neuroendocrine markers such as serotonin (5-HT) and acetyl cholinesterase (AChE) were studied in the brain. The findings showed that longer the exposure, higher the levels of biotransformation enzymes and DNA damage were produced. In both gill and the liver, BaP exposure generated dose-dependent EROD induction and DNA damages, with such a response being more linear in the case of liver than gill. BaP toxicity exacerbated the neurotoxicity by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity and serotonin levels in the brain and this response was dose-dependent. Neuroendocrine system and biotransformation enzyme have a negative correlation. Results of the correlation and regression data suggest the reduction of endocrine marker might be attributed to the activation of biotransformation enzymes. These findings showed that BaP exposure can harm the gills and liver by inducing the biotransfomation enzyme and causing DNA damage, and so inhibiting neurotransmitters in the brain. These findings are predicted to give fresh insight on the research of the ecotoxicology effect of PAHs on estuarine fish.

Keywords: BaP, Biotransformation enzymes, DNA damage, Neurotransmitters, Therapon jarbua

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Biotransformation occurs in estuarine fish after a 21-day exposure to BaP.

-

•

The method relies on the use of the commercial fish Terapon jarbua.

-

•

In fish, BaP causes neurotransmitter modulation and DNA damage.

-

•

The correlation analysis of the responses revealed that they were extremely significant.

-

•

The first research to demonstrate that BaP-induced biotransformation affects neurotransmitters in fish.

1. Introduction

A number of natural and xenobiotic substances are credited with endangering the aquatic ecology worldwide. Several compounds have been outlawed, and these include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), but they are still prevalent in aquatic environments, causing adverse affects to the health of living organisms, including human. PAHs are a group of chemicals found in the aquatic environment that are mostly acquired from anthropogenic sources such as fossil fuel spills, atmospheric deposition, and run-off from land, as well as household and industrial waste discharges. Organic pollutants, notably PAHs, which are suspected carcinogens, are a danger to individuals and the environment [1].

Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) is a five-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) produced mostly by burning of organic matter. This xenobiotic can be found in large quantities in the air, water, and sediment [2]. Since this compound can cause damage to both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, it is classed as one of the most toxic carcinogens belongs to PAH family [3] and classified as a Group I carcinogen [4]. Biomarkers, or biological responses to stress and pollutant exposure and impacts, are increasingly being used as pollution monitoring indicators, allowing for the early detection of cause-and-effect relationships.

Due to recent industrial developments, the PAH content in the aquatic environment is increasing. Estuary ecosystems are most affected by pollutants, since they connect both freshwater and marine waters [5]. Fish are found almost everywhere in an aquatic environment and ecologically important as they are part of aquatic food webs that transport energy from lower trophic levels to higher trophic levels [6]. Despite certain limitations such as higher mobility in fishes they are very sensitive and suitable biomonitoring agents for aquatic pollution. Terapon jarbua has been used in toxicity studies as an environment bio-indicator, since these euryhaline fish can exist in different habitats from exclusive marine areas to coastal waters, estuaries and freshwater, semi-pelagic, susceptibility to contaminants, year-round availability and also its ease of acclimatisation to laboratory conditions [7].

The main objective of the present study was to develop and validate an ecotoxicological strategy for assessing contamination in an estuarine area based on the detection of biomarker in the sentinel species mentioned above. More specifically this study looked into the neuroendocrine disruption caused by BaP exposure. The cytochrome P450 biomarker, which belongs to a large family of mixed hepatic oxidase enzymes involved in phase I xenobiotic bioconversion, has been the most studied and one of the first biomarkers of fish for PAHs both in the laboratory and in the field and this phase I biotransformation systems are thought to respond selectively to PAHs in fish [8]. Induction of cytochrome P450 1 A (CYP1A) upon exposure to organics is measured by the activity of 7-ethoxyresorupinodeethylase (EROD) [10], [9], [11].

Marine biomonitoring programmes have traditionally used genotoxic endpoints as pollution indicators [12]. Presence of high levels of BaP has been linked to DNA damage in fish [13], [14]. The formation of semiquinones and quinones as a result of BaP metabolism results in the establishment of a redox cycle that generates free radicals. Free radicals have the potential to harm biological macromolecules and hence DNA oxidation in the tissues of marine organisms might be one of the most important early markers of such damage [15].

Acetylcholine esterase (AChE) and monoamines (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) are important neurotransmitters that are affected by xenobiotics [16], [11]. The serotogenic system of the brain is essential for neuroendocrine function in maintaining homeostasis in the face of physiological or environmental disturbances. It has been reported that xenobiotics from the environment affect the biogenic amines in the brains of fish [17]. Due to the monoaminergic system linking behavior and physiology, toxic substances that target these neurotransmitters can have negative effects on a group of vertebrates [16]. Although various research on the effects of BaP on marine species have been conducted, the relationship and mechanisms involving BaP toxicity on biotransformation, DNA damage, and endocrine disruption in estuarine fish have yet to be established. The current work investigated the long term impact of BaP on these indicators in the estuarine fish T. jarbua, as well as the association between BaP toxicity and neuroendocrine disturbance.

2. Materials and methods

T. jarbua specimens measuring 9 ± 3 cm in length (juvenile stage) and weighing 20 ± 4 g were collected and transferred to the laboratory from the creek in Kovalam, Chennai, India. The water temperature, salinity, and pH were all kept at 28 ± 1 °C, 25 parts per thousand, and 8.1, respectively. Prior to the toxicological studies, the animals were acclimatized for a week to the laboratory conditions. Water, waste feed, and faeces were removed daily, and the fish were fed fresh prawn flesh ad libitum (3% body weight).

2.1. Toxicity test for biomarkers

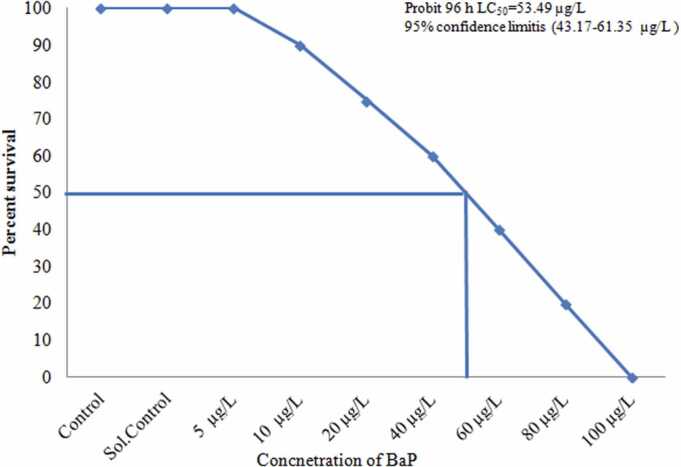

All toxicity tests were done as per the guidelines of Environmental Protection Agency EPA (540/9–85–009) [18]. Briefly, stock solution of BaP was prepared at 1 mg L−1 using Acetone (HPLC grade). To determine the LC50 value of BaP a preliminary study of 96-hour bioassay test was conducted using the EPA's method to assess the lethal (LC100), median lethal (LC50), and sublethal (LC0) levels of BaP for T. jarbua. BaP exposure was done in 100-L glass tanks under semistatic conditions, with the solutions replaced once a day. BaP doses of 5, 60 and 100 µg/L were found to be sublethal (LC0), median lethal (LC50), and lethal (LC100) concentration to T. jarbua, respectively (Fig. 1). Healthy control (blank control) and solvent control (Vacetone/Vseawater = 1/20 000) were also maintained. Using a Hitachi Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (F-4600), the BaP concentrations employed in the experiment were environmentally realistic and measured during the exposure time following the method of Wang et al., [19] with ex/em = 380/430 as the test condition.

Fig. 1.

Percentage survival of T. jarbua in different B(a)P concentrations for 96 h and its median lethal concentration (LC50 with 95% upper and lower confidence limits) calculated by probit analysis.

2.2. Sub acute exposure of BaP

For this the fish were randomly divided into 4 groups and each experimental group had 40 fishes and each group was divided into duplicates with 20 fishes in each tank. Group I: normal seawater; group II: solvent control (95% acetone); group III: 1 μg/L BaP and IV: 4 μg/L BaP. Test solution was renewed daily and fish fed once a day. After exposure for 7, 14 and 21 days six fishes from each group were used to analyse the biomarkers. All experiments were as per the Animal Use Committee of India guidelines. Since the results obtained with solvent and blank were similar, data for only solvent control is depicted in the figures and tables.

2.3. Determination of 7-ethoxyresorufin O-deethylase (EROD) activity

EROD was measured in T. jarbua gills and liver tissues. Liver EROD activity was assessed in microsomal pellets, as described by Thilagam et al. [20] following Burke and Mayer [21]. Gill filament EROD activity was carried out as per Jonsson et al. [22]. A microplate reader was used to detect EROD activity at 535/585 nm excitation/emission wavelengths. Cytosolic and microsomal protein content was determined using the method of Bradford [23].

2.4. Evaluation of DNA strand breaks

The alkaline unwinding technique of Shugart [24] was used to assess DNA strand breakage by alkaline unwinding assay, in which strand separation is obtained under controlled conditions and the quantities of double and single-stranded DNA after alkaline unwinding was measured using fluorescence at 360 nm excitation and 450 nm emission wavelengths.

2.5. Determination of neuroendocrine disruption in brain

A modified methodology from Gagne and Blaise [25] was adopted to determine serotonin levels in the brain. Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold butanol + HCl and glutathione, centrifuged (700 x g 4 °C), and supernatant mixed with heptane. The aqueous phase of the centrifuged sample was removed and stored in a glass tube. A mixture of butanol was used to make the serotonin standard. An ortho-phthalaldehyde solution was used to administer to both standard and samples and was heated at 70 °C for 15 min in dark. After the incubation period, all samples were measured using 96-well black bottom microtiter plates in a fluorescence spectrophotometer. The protein content was determined using the Bradford method as mentioned above. 5-HT concentrations were calculated using the mean fluorescence of each sample and then converted to g 5-HT/mg protein.

The acetylthiocholine substrate was used to assess acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity [26]. Homogenates were centrifuged (3000 x g) and supernatant was used to determine acetylcholinesterase activity by mixing with 0.5 mM acetylthiocholine and Ellman's reagents (5,5′-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) at pH 7.2 in a 100 mM Tris-acetate buffer. The process was monitored spectrophotometrically at 412 nm for three minutes at room temperature.

2.6. Statistical analyses

SPSS software (20.0) was used to calculate the statistical analysis. Significance of the results was determined by calculating the mean and standard deviation of 6 samples per group. To detect statistical differences among specific treatment groups, the data were subjected to a two-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey's multiple-comparison post-hoc test. The interrelationships between the parameters were evaluated using principal component analysis (PCA) and a correlation matrix. The PCA's extraction and derivation factors were done using "Varimax Rotation," and the correlation matrix was made using the Pearson correlation coefficient.

3. Results

3.1. EROD activity in gill and liver

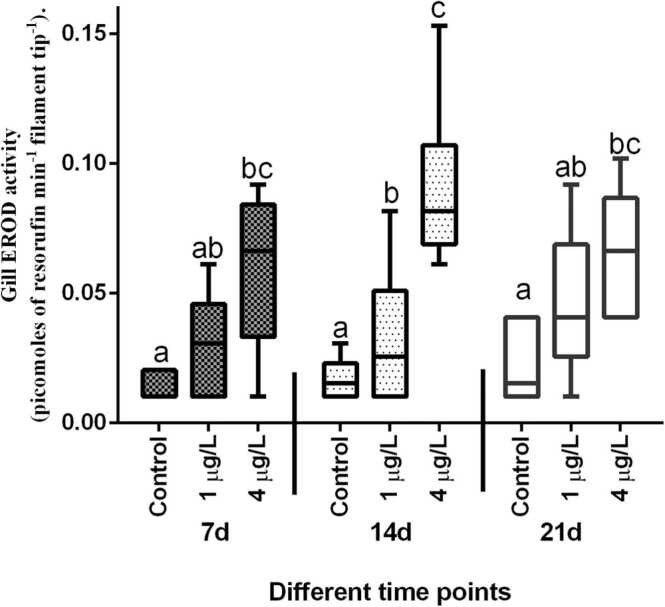

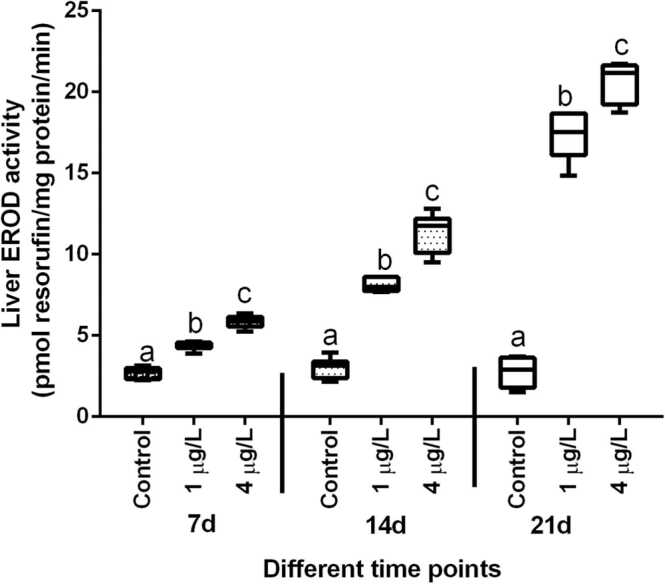

EROD activity in the gills of fish exposed to BaP was greater when compared to the respective control group (Fig. 2), however the higher concentration of BaP (4 µg/L) produced a significant increase in EROD activity at all the time points. After 14 d of exposure of fish to BaP, fourfold increase in gill EROD activity was observed when the fish exposed to 4 µg/L of BaP and such increase in EROD activity was statistically significant (p < 0.001) with the respective control group. A similar trend was also observed after 3 weeks of BaP exposure but such increase was only upto 2 folds. EROD activity in the liver of T. jarbua exposed to different concentrations of BaP is shown in Fig. 3. Liver EROD activity after normalisation with microsomal protein was significantly (p < 0.001) elevated after 7 d of BaP exposure to both the concentrations. After 14 d of exposure of BaP, T. jarbua showed three-fold increase in EROD activity at the environmentally relevant concentration (1 µg/L) with respective control group and the same showed 5-fold increase after 21 d exposure. Similar increasing trend was observed when fish exposed to the higher concentration (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of BaP on gill EROD activity of T. jarbua. The line in each box represent median and whiskers represents the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test was performed. The same letters (a, b, c, d) indicate no significant difference between the exposure groups, while distinct letters imply statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between distinct groups.

Fig. 3.

Effect of BaP on Hepatic EROD activity of T. jarbua. The line in each box represent median and whiskers represents the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test was performed. The same letters (a, b, c, d) indicate no significant difference between the exposure groups, while distinct letters imply statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between distinct groups.

3.2. DNA integrity in gill and liver

Integrity of DNA in the gill tissues observed when fish were exposed to BaP (Fig. 4). After 7 d of exposure of fish to 4 µg/L BaP, there was a significant reduction (p < 0.001) in the DNA integrity in the gill. Similarly after 14 and 21 d of exposure, both BaP concentrations had a greater effect on gill DNA integrity compared to the corresponding controls. A similar trend was observed for DNA integrity in livers of T. jarbua when exposed to BaP (Fig. 5). However, the liver had a greater impact at both test concentrations even after 7 d exposure and all these changes observed were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Effect of BaP on DNA damage in the gills of T. jarbua. The line in each box represent median and whiskers represents the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test was computed. The same letters (a, b, c, d) indicate no significant difference between the exposure groups, while distinct letters imply statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between distinct groups.

Fig. 5.

Effect of BaP on DNA damage in the liver of T. jarbua. The line in each box represent median and whiskers represents the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used. The same letters (a, b, c, d) indicate no significant difference between the exposure groups, while distinct letters imply statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between distinct groups.

3.3. Neuroendocrine disruption in brain Serotonin level

T. jarbua treated to BaP revealed a strong dose-dependent drop in 5-HT levels in the brain (Fig. 6). Throughout the exposure period, the decreases in 5-HT levels were highly significant (p < 0.001). When fish were exposed to the highest concentration (4 µg/L) of BaP for 21 d, their serotonin levels declined up to threefold when compared to the corresponding control group.

Fig. 6.

Effect of BaP on 5-HT concentration in the brain of T. jarbua. The line in each box represent median and whiskers represents the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test was performed. The same letters (a, b, c, d) indicate no significant difference between the exposure groups, while distinct letters imply statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between distinct groups.

3.4. Acetylcholine esterase activity

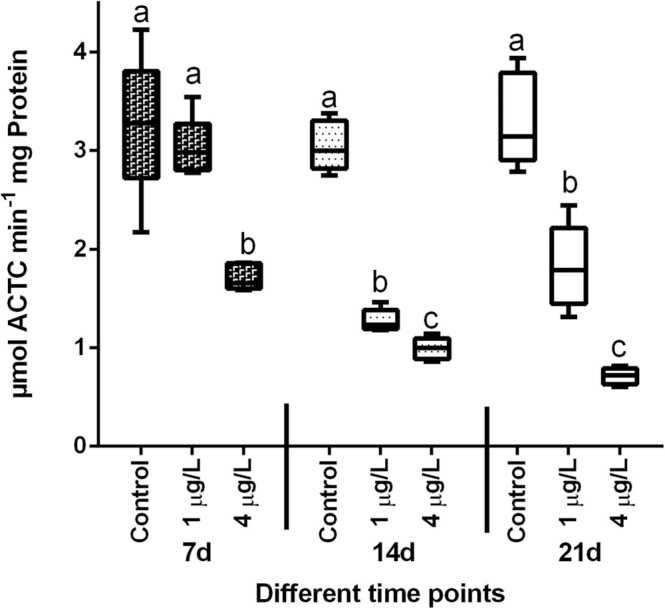

When fish were exposed to BaP, the activity of the enzyme AChE in the brain was inhibited (Fig. 7). When compared to the respective control, AChE activity in T. jarbua brain exposed to low concentration after 7 days was statistically insignificant. However, following 14 and 21 d of exposure, AChE activity was shown to be dramatically reduced. AChE activity in the brain was dramatically suppressed after 21 d of exposure, showing that BaP has a stronger impact and adverse effect.

Fig. 7.

Effect of BaP on AChE activity in the brain of T. jarbua. The line in each box represent median and whiskers represents the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals of the mean. Two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used. The same letters (a, b, c, d) indicate no significant difference between the exposure groups, while distinct letters imply statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between distinct groups.

The Pearson correlation matrix between the parameters studied is shown in Table 1. Individual parameter correlation produced findings equivalent to PCA and revealed a substantial link between the investigated parameters. Most of the time, the correlation coefficient between EROD activity and the neuroendocrine system was more than 0.593 for the gills and 0.742 for the liver. In BaP-exposed T. jarbua, there was a positive association between DNA integrity and brain 5-HT (R2 = liver 0.697, gill 0.626), and R2 values were determined to be statistically significant in both organs (Table 1). The levels of 5-HT and AChE in the brain correlated similarly (R2 = 0.872), and the R-squared value was statistically significant (R2 = 0.788, R2 = 0.593). T. jarbua EROD activity was shown to be inversely linked with serotonin levels and the R-squared values were statistically significant. Similarly, R2 values of gill and liver EROD activity (0.596 and 0.742) were negatively linked with brain AChE. Furthermore, the current study found a link between DNA damage and EROD activity in T. jarbua's gills and liver. The negative relationship discovered between biotransformation enzymes and DNA damage was mild yet substantial.

Table 1.

Pearson Correlations matrix for the biotransformation, DNA integrity and neuroendocrine hormone in T. jarbua exposed to different concentration of BaP.

| Serotonin | AchE | Gill EROD | Liver EROD | DNA LIVER | DNA GILL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serotonin | 1.00 | .872** | -.593** | -.788** | .697** | .626** |

| AchE | 1.00 | -.596** | -.742** | .662** | .615** | |

| Gill EROD | 1.00 | .498** | -.475** | -.471** | ||

| Liver EROD | 1.00 | -.537** | -.382** | |||

| DNA LIVER | 1.00 | .578** | ||||

| DNA GILL | 1.00 |

* *. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

In order to evaluate the association between biotransformation enzymes and the neuroendocrine system, a linear regression analysis was done in this study using SPSS 20.0. Neurotransmitter components were classified as dependent factors, whereas biotransformation enzymes and DNA integrity were classified as independent variables (Table 2a,Table 2b and Table 3a,Table 3b, Fig. 8). Simultaneously, ANOVA was computed to assess the significance of the variables, and the results are shown in Table 3a,Table 3b. R2 alterations show that biotransformation enzymes and DNA damage were responsible for around 70% of AChE modifications. Similarly, the efficiency of serotonin rose by up to 75%. Table 3a,Table 3b displays the change in R square value as a function of biotransformation enzyme and DNA damage.

Table 2a.

Anova for the biotransformation, DNA integrity and AchE hormone inT. jarbuaexposed to different concentration of BaP.

| ANOVAa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| 1 | Regression | 34.885 | 4 | 8.721 | 26.506 | .000b |

| Residual | 15.135 | 46 | .329 | |||

| Total | 50.021 | 50 | ||||

Table 2b.

Anova for the biotransformation, DNA integrity and serotonin hormone in T. jarbua exposed to different concentration of BaP.

| ANOVAa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| 1 | Regression | 344.374 | 4 | 86.093 | 35.956 | .000b |

| Residual | 110.142 | 46 | 2.394 | |||

| Total | 454.516 | 50 | ||||

a. Dependent Variable: Serotonin

b. Predictors: (Constant), DNAGILL, DNA LIVER, Liver EROD, Gill EROD,

Table 3a.

Predicted linear regression for the biotransformation, DNA integrity and AchE hormone in T. jarbua exposed to different concentration of BaP.

| Model Summaryb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Change Statistics |

||||

| R Square Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change | |||||

| 1 | .835a | .697 | .671 | .57361 | .697 | 26.506 | 4 | 46 | .000 |

Table 3b.

Predicted linear regression for the biotransformation, DNA integrity and serotonin hormone in T. jarbua exposed to different concentration of BaP.

| Model Summaryb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Change Statistics |

||||

| R Square Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change | |||||

| 1 | .870a | .758 | .737 | 1.54738 | .758 | 35.956 | 4 | 46 | .000 |

a. Predictors: (Constant), DNA GILL, DNA LIVER, Liver EROD, Gill EROD

b. Dependent Variable: Serotonin

Fig. 8.

Regression analysis between Neurotransmitters and biotransformation enzyme in T. jarbua exposed to BaP.

4. Discussion

Biomarkers are valuable at the molecular level because they respond quickly to chemical stimuli and tend to be highly specific [27]. However, because of the frequently confusing link between biochemical reactions and endpoints such as physiological, reproductive, and behavioural responses, their relevance is restricted when seeking to analyse the effect of exposures on the whole organism [28]. Contamination of aquatic environment by PAH is a global environmental concern due to its ubiquitous and harmful nature. EROD is considered highly sensitive biomarker for pollutant exposure in fish, showing that xenobiotics induce cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase through receptor-mediated induction [29]. The purpose of this study was to determine whether EROD activity can be used as a PAH biomarker in estuarine fish and is dose-dependent.

Although several studies have shown CYP1A activity as an indicator of the effect of PAH on marine fish [30], [31], no data are available for euryhaline fish T. jarbua. The effect of BaP on CYP1A activity was found to be significant in this study. Similar administration of BaP to red sea bream elevated gill EROD activities, and the current work lends further evidence that EROD activity can be produced by organic pollutants [33], [20], [32]. Nevertheless, this kind of a phase I detoxification system responds very selectively to BaP in fish in a concentration-dependent manner [34]. After prolonged exposure (21 d), EROD activity was higher in T. jarbua exposed at 4 μg/L BaP compared to the lower exposure concentration and corresponding controls exhibiting a dose-dependent response to CYP1A induction (Bo et al., 2010).

Abrahamson et al., [35] reported that gill EROD activity is more susceptible to the pollutants than liver EROD activity. On contrary the results of the present study demonstrated that liver EROD activity was more sensitive to BaP than gill EROD activity, and liver EROD activity increased considerably in T. jarbua in both the exposed concentration of BaP from 7 to 21 d. Liver EROD activity was roughly 100-fold greater than gill EROD activity throughout the exposure period, and liver EROD activity was also considerably stimulated during the exposure period. As a result, liver EROD activity was shown to be more responsive to BaP exposure than gill EROD activity. The greatest induction of EROD activities in gill filaments (4-fold) after 14 d of exposure and a 6-fold rise in liver microsomes after 21 d of BaP exposure are similar to earlier findings [22], [32].

PAHs' genotoxic effects are typically related to their biotransformation inside the host, notably preliminary oxidative metabolism of PAH by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases, rather than the amounts of their parent component in cells. These reactions can result in reactive metabolites that are potentially more dangerous than the original molecule, that can lead to DNA adduct as well. The current findings showed that BaP exposure may cause oxidative DNA damage in the gills and liver of estuarine fish, and that this damage was time-dependent, even at low concentrations. After 21 d of exposure, we discovered DNA damage in the estuarine fish T. jarbua, which was tissue specific, with the liver displaying greater damage than the gills, may be due to the more metabolites of BaP have been generated in liver than gill and need to be analysed and also highlighting the necessity of studying the liver for DNA damage quantification. Despite the fact that the gills are an exterior organ that is more easily exposed to dissolved toxins than the inner organ liver, the gills' ability to accumulate, biotransform, and metabolise pollutants into reactive chemicals may be less than that of the liver. Variations in phase I BaP metabolism rate might potentially be linked to variances in the liver and gill tissues [36]. The stimulation of EROD activity is also connected to an increase in DNA damage, according to our findings. A substantial negative correlation (R2 =−0.537) was observed between DNA damage and liver EROD activity in T. jarbua. In the gill, a negative correlation was found between these two measures, showing that EROD activation and DNA damage may be associated with BaP metabolism in the liver, and that metabolites may be related to DNA damage in both gill and the liver.

PAH has been shown to non-specifically affect and turnover of the serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenergic systems in brain tissues [37]. In addition, increased levels of metabolites, usually accompanied by higher metabolite/monoamine ratios, may enhance the effects of stress in the monoamine system of the fish brain [38], [39]. Experiments have shown that effects of PAHs on the content of neurotransmitters in response to stress stimuli differed by hydrocarbon type, brain region, and type of stress stimulus. In this study, BaP showed an inhibitory effect on brain monoamines in fish exposed for prolonged period, indicating that even the lowest dose studied was inhibitory and did not allow monoamine levels to return to normal levels in fish.

AChE activity inhibition in marine organisms has routinely been used as a marker for pollution-induced neurotoxicity [41], [40]. Exposure to BaP inhibits AChE activity in the brain significantly in the current study. Reduced AChE activity may restrict AChE hydrolysis [42], thus affecting the nervous system and rendering gill tissue susceptible to external stressor [43] and these studies demonstrated that BaP induces neurotoxicity in fish, just as it does in other higher vertebrates, and that the AChE index may be utilised to detect BaP contamination.

The correlation analysis demonstrates a substantial relation between 5-HT and AChE and EROD activity and DNA damage. The correlation between EROD activity and neuroendocrine enzymes, on the other hand, was negative but significant. These findings imply that the complicated stress response may be influenced by interactions across numerous signalling systems, making it difficult to discern between causes and effects. Although there is no evidence of a link between EROD activity and neuroendocrine function, the present findings suggest that BaP metabolites produced during the Phase I enzyme transition may cause changes in brain physiological activity, leading to BaP-induced stress and endocrine dysfunction in the brain as measured by serotonin and AChE levels.

Once a relation between P450 enzyme function and/or regulation and other molecular processes are established, the overall relevance of these enzymes in hazardous pathways will be revealed. Interconnections occur between P450 system, DNA damage, and other endocrine pathways. These complex interactions demonstrate how difficult it is to assess and analyse the toxicological consequences of biotransformation systems that have been affected by environmental pollutants. Chronically intoxicated fish can develop morphological barriers to toxicants and activate detoxification mechanisms, making them more resistant to them [44].

5. Conclusions

Although evidence points to the fact that certain biomarker responses serve as early warning indicators of adverse changes in the health or fitness of specific species, it remains difficult to correlate these changes with impacts on populations, communities, or ecosystems. Due to the susceptibility of populations and communities' responses to naturally changing environmental factors, in most cases the observed field responses to stressors cannot be safely attributed to the primary action of the stressor itself, even when most carefully selected for comparison of reference and polluted sites. Therefore, this study concluded that ambient BaP concentrations could have significant effects on biotransformation enzymes and neuroendocrine systems, which could alter the physiology and other biological activities of fish populations in estuarine environments. Further the current work will give critical information on neuroendocrine disturbances caused by BaP-induced biotransformation in T. jarbua. Moreover, the knowledge gathered from this work will aid future research and assessment of possible roles of neurotransmitter regulation in a polluted environment. A longer-term research is anticipated to shed additional light on the chronic impact of pollution on marine species and how they may adapt to xenobiotics and so survive in complex environmental systems.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Ethical approval

For the care and use of animals, all applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines were followed.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Head, Research department of Zoology and also the Principal Pachaiyappa’s College for Men, Chennai- 600 030, and Head, Research department of Zoology and also the Principal Government Arts College for men (Autonomous), Chennai-600 035 India for extending their support through the experiment.

Contributor Information

R. Krishnamurthy, Email: professorkrishnamurthy@gmail.com.

H. Thilagam, Email: thilagampachaiyappas@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hussein I., Mona Abdel-Shafy, Mansour S.M. A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016;25(1):107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawal A.T. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. A review. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2017;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pavanello S., Dioni L., Hoxha M., Fedeli U., Mielzynska-Svach D., Baccarelli A.A. Mitochondrial DNA copy number and exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 2013;22(10):1722–1729. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jameson C.W. In: Tumour Site Concordance and Mechanisms of Carcinogenesis. Lyon (FR) Baan R.A., Stewart B.W., Straif K., editors. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2019. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and associated occupational exposures. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray A.K., Tripathy S.C., Patra S., Sarma V.V. Assessment of Godavari estuarine mangrove ecosystem through trace metal studies. Environ. Int. 2006;32(2):219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donald R.S., Kenneth T.F. Human involvement in food webs. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010;35(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnakumari L., Gajbhiye S.N., Govindan K., Nair V.R. Toxicity of some metals on the fish therapon jarbua (Forsskal, 1775) Indian J. Mar. Sci. 1983;12(1):64–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arukwe A., Forlin L., Goksoyr A. Xenobiotic and steroid biotransformation enzymes in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) liver treated with an estrogenic compound, 4-nonylphenol. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1997;16:2576–2583. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bo J., Gopalakrishnan S., Fan D.Q., Thilagam H., Qu H.D., Zhang N., Chen F.Y., Wang K.J. Benzo[a]pyrene modulation of acute immunologic responses in red Sea bream pretreated with lipopolysaccharide. Environ. Toxicol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/tox.21777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrera E.P., Garcia-Lopez A., del Rio M.D.M., Martinez-Rodriguez G., Sole M., Mancera J.M. Effects of 17 beta-estradiol and 4-nonylphenol on osmoregulation and hepatic enzymes in gilthead sea bream (Sparus auratus) Comp. Biochem Physiol. Part C. 2007;145:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thilagam H., Gopalakrishnan S., Bo J., Wang K.J. Comparative study of 17 β-estradiol on endocrine disruption and biotransformation in fingerlings and juveniles of Japanese sea bass Lateolabrax japonicus. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 30. 2014;85(2):332–337. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lionetto M., Caricato R., Giordano M. Pollution biomarkers in environmental and human biomonitoring. the open biomarkers. Journal. 2019;9:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung D., Cho Y., Collins L.B., Swenberg J.A., Di Giulio R.T. Effects of benzo[a]pyrene on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage in Atlantic killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus) from a creosote-contaminated and reference site. Aquat. Toxicol. 2009;95(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meier S., Karlsen Ø., Le Goff J., Sørensen L., Sørhus E., et al. DNA damage and health effects in juvenile haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) exposed to PAHs associated with oil-polluted sediment or produced water. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marrocco I., Altieri F., Peluso I. Measurement and clinical significance of biomarkers of oxidative stress in humans. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017;2017:6501046. doi: 10.1155/2017/6501046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sloman K.A., Lepage O., Rogers J.T., Wood C.M., Winberg S. Socially mediated differences in brain monoamines in rainbow trout: effects of trace metal contaminants. Aquat. Toxicol. 2005;71:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan I.A., Mathews S., Okuzawa K., Kagawa H., Thomas P. Alterations in the GnRH–LH system in relation to gonadal stage and Aroclor 1254 exposure in Atlantic croaker. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 2001;129:251–259. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.EPA-540/9–85-009. Acute Toxicity Test for Estuarine and Marine Organisms (Estuarine Fish 96-Hour Acute Toxicity Test).

- 19.Wang K.J., Bo J., Yang M., Hong H.S., Wang X.H., Chen F.Y., Yuan J.J. Hepcidin gene expression induced in the developmental stages of fish upon exposure to Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) Mar. Environ. Res. 2009;67:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thilagam H., Gopalakrishnan S., Qu H.D., Bo J., Wang K.J. 17b estradiol induced ROS generation, DNA damage and enzymatic responses in the hepatic tissue of Japanese sea bass. Ecotoxicology. 2010;19:1258–1267. doi: 10.1007/s10646-010-0510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke M.D., Mayer R.T. Ethoxyresorufin: direct fluorimetric assay of a microsomal O-dealkylation which is preferentially inducible by 3-methylcholanthrene. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1974;2:583–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonsson E.M., Brandt I., Brunstrom B. Gill filament-based EROD assay for monitoring waterborne dioxin-like pollutants in fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002;36:3340–3344. doi: 10.1021/es015859a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shugart L.R. Quantitation of chemically induced damage to DNA of aquatic organisms by alkaline unwinding assay. Aquat. Toxicol. 1988;13:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gagne F., Blaise C. Effects of municipal effluents on serotonin and dopamine levels in the freshwater mussel Elliptio complanata. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C. 136. 2003:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0456(03)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellman G.L., Courtney K.D., Andres V., Feather-Stone R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Oost R., Beyer J., Vermeulen N.P. Fish bioaccumulation and biomarkers in environmental risk assessment: a review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharm. 2003;13(2):57–149. doi: 10.1016/s1382-6689(02)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vandenberg L.N., Colborn T., Hayes T.B., Heindel J.J., Jacobs D.R., Jr., Lee D.H., Shioda T., Soto A.M., vom Saal F.S., Welshons W.V., Zoeller R.T., Myers J.P. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocr. Rev. 2012;33(3):378–455. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whyte J., Jung R., Schmitt C., Tillitt D. Ethoxyresorufin- O -deethylase (EROD) activity in fish as a biomarker of chemical exposure. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2000;30:347–570. doi: 10.1080/10408440091159239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jönsson E.M., Abrahamson A., Brunström B., Brandt I. Cytochrome P4501A induction in rainbow trout gills and liver following exposure to waterborne indigo, benzo[a]pyrene and 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006;79:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee R.F., Anderson J.W. Significance of cytochrome P450 system responses and levels of bile fluorescent aromatic compounds in marine wildlife following oil spills. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005;50(7):705–723. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bo J., Gopalakrishnan S., Chen F.Y., Wang K.J. Benzo[a]pyrene modulates the biotransformation, DNA damage and cortisol level of red sea bream challenged with lipopolysaccharide. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 30. 2014;85(2):463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.05.023. Epub 2014 May 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navas J.M., Segner H. Estrogen-mediated suppression of cytochrome P4501A (CYP1A) expression in rainbow trout hepatocytes: role of estrogen receptor. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2001;138:285–298. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(01)00280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mdegela R., Braathen M., Correia D., Mosha R., Skaare J., Sandvik M. Influence of 17α-ethynylestradiol on CYP1A, GST and biliary FACs responses in male African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) exposed to waterborne Benzo[a]Pyrene. Ecotoxicology. 2006;15:629–637. doi: 10.1007/s10646-006-0098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abrahamson A., Andersson C., Jonsson M.E., Fogelberg O., Orberg J., Brunstrom B., Brandt I. Gill EROD in monitoring of CYP1A inducers in fish: a study in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) caged in Stockholm and Uppsala waters. Aquat. Toxicol. 2007;85:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zanger U.M., Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharm. Ther. Apr. 2013;138(1):103–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gesto M., Soengas J.L., Miguez J.M. Acute and prolonged stress responses of brain monoaminergic activity and plasma cortisol levels in rainbow trout are modified by PAHs (naphthalene, beta-naphthoflavone and benzo(a)pyrene) treatment. Aquat. Toxicol. 2008;86:341–351. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Øverli Ø., Pottinger T.G., Carrick T.R., Øverli E., Winberg S. Brain monoaminergic activity in rainbow trout selected for high and low stress responsiveness. Brain Behav. Evol. Apr. 2001;57(4):214–224. doi: 10.1159/000047238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribera Joan M., Marzia Tindara V., Winfried O., Ronald B.M., Tom G., Alexander R., Ulrike G. Time-dependent effects of acute handling on the brain monoamine system of the salmonid coregonus maraena. Front. Neurosci. 2020;14:1293. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.591738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bainy A.C.D., Medeiros M.H.G., Mascio P.D., Almeida E.A. In vivo effects of metals on the acetylcholinesterase activity of the Perna perna mussel’s digestive gland. Biotemas. 2006;19(35–39):2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monserrat J.M., Bianchini A., Bainy A.C.D. Kinetic and toxicological characteristics of acetylcholinesterase from the gills of oysters (Crassostrea rhizophorae) and other aquatic species. Mar. Environ. Res. 2002;54:781–785. doi: 10.1016/s0141-1136(02)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi W., Han Y., Guan X., Rong J., Du X., Zha S., Tang Y., Liu G. Anthropogenic noise aggravates the toxicity of cadmium on some physiological characteristics of the blood clam tegillarca granosa. Front Physiol. 3;10:377. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cong M., Wu H., Yang H., Zhao J., Lv J. Gill damage and neurotoxicity of ammonia nitrogen on the clam Ruditapes philippinarum. Ecotoxicology. 2017;26:459–469. doi: 10.1007/s10646-017-1777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lushchak V.I., Matviishyn T.M., Husak V.V., Storey J.M., Storey K.B. Pesticide toxicity: a mechanistic approach. EXCLI J. 2018;17:1101–1136. doi: 10.17179/excli2018-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]