Abstract

A method capable of identifying drug-induced arteritis is highly desirable because no specific and sensitive biomarkers have yet been defined. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to find a biomarker candidate for drug-induced arteritis, there are no reports on the evaluation of drug-induced arteritis by MRI. The present study was conducted to clarify whether Fenoldopam mesylate (FM)-induced arteritis in rats can be detected by MRI. FM, a dopamine (D1 receptor) agonist, is known to induce arteritis in rats. FM was administered subcutaneously to each rat once daily for 2 days at a dose of 100 mg/kg/day. These arteries were examined with ex vivo high-resolution MRI or postmortem MRI after euthanasia. These arteries were also examined using in vivo MRI on the day after final dosing or 3 days after administration of the final dose. These arteries were examined histopathologically in all experiments. The ex vivo MRI showed low-intensity areas and a high signal intensity region around the artery, and these findings were considered to be erythrocytes infiltrating the arterial wall and perivascular edema, respectively. In the in vivo study, the MRI of the FM-administered group showed a high signal intensity region around the artery. The perivascular edema observed histopathologically was recognized as a high signal intensity region around the artery on the image of MRI. In conclusion, detection of the high signal intensity region around the artery by MRI is considered to be a useful method for identifying arteritis. Although further investigation is needed to be a reliable biomarker, it is suggested that it could be a biomarker candidate.

Abbreviations: FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; FM, fenoldopam mesylate; FLASH, fast low-angle shot; TR, repetition time; TE, echo time; FA, flip angle; FOV, field of view; RARE, rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement; HE, hematoxylin and eosin

Keywords: Arteritis, Biomarker, Drug, Fenoldopam mesylate, Magnetic resonance imaging, Perivascular edema

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

The changes of the fenoldopam-induced arteritis were detected by ex vivo MRI.

-

•

Ex vivo MRI showed low-intensity spots and high signal intensity region.

-

•

Arteritis in rats could be detected by in vivo MRI by suppressing peristalsis.

-

•

In vivo MRI showed high signal intensity region around the artery.

-

•

Perivascular edema was recognized as the high signal intensity in the image of MRI.

1. Introduction

Even if a candidate drug is expected to be effective, development may have to be terminated if serious side effects occur. Toxicological findings in nonclinical toxicological studies of candidate drugs were the main cause of discontinuation of drug development, accounting for 40 % of drug development failures [21]. The occurrence of drug-induced arteritis in nonclinical toxicity studies is one of the causes for the pre-clinical attrition of candidate drugs [15].

In humans, vasculitis is known to be induced by several drug classes including antimicrobials and antithyroid medications [4]. The predominant site of drug-induced vasculitis is the skin, and lesions are sometimes found in the kidneys and lungs [4]. In humans, drug-induced vasculitis is complex and several mechanisms may be involved [5]. In nonclinical toxicological studies of several drugs, arteritis has been observed [12]. The mechanisms of arteritis have not been elucidated and they are not necessarily mutually exclusive; however, it is considered that three major mechanisms may be involved. One of the mechanisms is shear and/or hoop stress, another is the direct pharmacological effect of chemicals and the third is related to immunological and inflammatory response [11].

Drug-induced arteritis is difficult to monitor in clinical trials of candidate drugs because the underlying mechanism has not been elucidated and no specific and sensitive biomarkers have yet been defined in humans [13], [15]. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been working on various biomarkers of drug-induced arteritis in collaboration with a number of pharmaceutical companies and other research institutes and the search for biomarkers of arteritis has also been undertaken by the Vascular Injury Working Group [11], [15]. However, it is difficult to narrow these down to specific biomarkers that could become the gold standard [11], [15]. In the absence of noninvasive methods to monitor the onset of drug-induced arteritis, its occurrence in nonclinical toxicity studies can become an obstacle to the development of candidate drugs, even if a drug is predicted to be safe and efficacious in humans [15]. Therefore, a noninvasive method capable of identifying drug-induced arteritis is highly desirable.

In humans, diagnostic imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are used effectively for vasculitis syndrome affecting large- or medium-sized arteries (e.g. Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis, Buerger's disease and polyarteritis nodosa) [7], [18]. Although MRA is the most frequently used method among magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques in the diagnosis of vascular lesion, MRA is mainly employed to detect abnormalities in vascular lumen morphology, such as occlusion and stenosis, by visualizing the vessel lumen, and not to detect abnormalities of the blood vessel itself, because MRA is an angiographic method. On the other hand, it has been reported that contrast-enhanced (late gadolinium enhancement) MRI (1.5-T) could be useful for detecting blood vessel abnormalities [10]. In this report, the distribution of inflammation in the vessel wall of a large artery was visualized by contrast-enhanced MRI, with the potential to identify pathologic changes in the arterial wall, independent of luminal change. However, there are no reports on the application of MRI to drug-induced arteritis.

In rats, although it has been reported that arteritis in large arteries induced by mechanical stimulation can be detected by MRI (7-T) with gadolinium-labeled perfluorocarbon-exposed sonicated dextrose albumin microbubbles [1], there are no reports of drug-induced arteritis being detected by MRI. Further, in the above report, large arteries were assessed; however, drug-induced arteritis is more likely to develop in medium and small arteries rather than large arteries in rats. Detection of drug-induced arteritis in medium and small arteries by MRI is important, especially in rodents.

MRI is non-invasive and widely used in humans, and evaluation of the organs of rodents requires higher resolution due to their small size. Therefore, research into MRI in rodents has not progressed to the same degree as that in humans. However, in vivo imaging techniques, including MRI in rodents, have made remarkable advances in recent years, and their application to pharmacological evaluation of the central nervous system is progressing [16]. Also in the safety assessment of candidate drugs, methods using in vivo imaging technology have attracted a great deal of attention, and demand for these methods is increasing.

Fenoldopam mesylate (FM) is an antihypertensive drug and used for hypertension and hypertension crisis. FM is a dopamine (D1 receptor) agonist, and causes arteritis in rats due to its vasodilatory effect ([3], [20]). Although FM-induced arteritis is not observed in mice, dogs and humans, it is also observed in a monkey [20]. In rats, the mesenteric artery, which is a small- to medium-sized vessel, is mainly affected [2], [8]. In a monkey, arteritis was observed in arterioles of the gastric and submucosa and a renal arterial branch. The lesion was similar between rats and a monkey [20]. These drug-induced arteritis in medium and small arteries were only evaluated histologically, and there are no reports of in vivo evaluation including MRI.

The present study was conducted to clarify whether FM-induced arteritis in rats can be detected by in vivo MRI. Before in vivo evaluation using live animals, ex vivo MRI and postmortem MRI using euthanized animals were performed. First, ex vivo MRI was performed to evaluate whether the changes caused by FM can be detected by MRI under ideal condition (no movement with high resolution). Second, postmortem MRI was performed to evaluate whether the changes can be detected in the situation where both respiration and peristalsis were absent but the other conditions are the same as those in in vivo MRI. And finally, in vivo MRI was performed in the imaging condition determined from the results of ex vivo MRI and postmortem MRI.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Compound

FM (the purity is 95 % or more) was purchased from Cayman Chemical (MI, USA). FM was dissolved in saline to reach a concentration of 20 mg/ml. Chlorpromazine hydrochloride (the purity is 99 % or more), which was used to suppress peristalsis of the intestinal tract, was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Chlorpromazine hydrochloride was dissolved in 0.5 w/v% methyl cellulose solution to reach a concentration of 5 mg/ml.

2.2. Animal husbandry

All animal studies were approved by the Committee for the Ethical Usage of Experimental Animals of Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd (current name is Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd.) and the Animal Welfare Committee of Osaka University.

Female Sprague-Dawley (Crl:CD) rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc. (current name is The Jackson Laboratory Japan, Inc.; Kanagawa, Japan) and had an acclimation period of more than 1 week. The animals were housed individually in a barrier-sustained room at a controlled temperature of 24 °C ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 55 % ± 10 %, and a 12-h light (8 a.m. to 8 p.m.)/dark cycle.

The rats were fed a commercial pellet diet (CE-2, CLEA Japan, Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan) and tap water ad libitum.

2.3. Animal model

FM was administered subcutaneously to each rat (6 weeks of age at the start of administration) once daily for 2 days at dose of 100 mg/kg/day in saline (5 ml/kg). The dose was selected based on earlier reports [2], [6]. As vehicle control, saline only was administered to animals in the same way described above.

2.4. Experimental design

2.4.1. Experiment 1 (ex vivo high-resolution MRI and histopathology)

Animals weighing close to 170 g at the start of FM or saline administration were assigned to the FM group or the saline group (N = 3, each group). Mesenteric, pancreatic, gastrointestinal, and renal arteries were collected from animals necropsied on the day after final dosing. The mesenteric arteries were cut into two; one section was evaluated by MRI (ex vivo) and the other was evaluated by histopathological examination. In the histopathological examination, pancreatic, gastrointestinal, and renal arteries were also evaluated. In addition, the lumen diameter of mesenteric arteries was measured on both the images of MRI and histopathology.

2.4.2. Experiment 2 (MRI after euthanasia and histopathology)

Animals weighing close to 170 g at the start of FM or saline administration were assigned to the FM group or the saline group (N = 4, each group). One animal in the saline group and two animals in the FM group were evaluated by MRI after being euthanized by isoflurane anesthesia or CO2 inhalation on the day after final dosing. Surviving animals, which were not evaluated by MRI, were euthanized by exsanguination. All animals were necropsied and the mesenteric, pancreatic, gastrointestinal, and renal arteries were collected. These arteries were evaluated by histopathological examination.

2.4.3. Experiment 3 (in vivo MRI the day after final dosing and histopathology)

Animals weighing close to 170 g at the start of FM or saline administration were assigned to the FM group (N = 5) or the saline group (N = 6). These animals were fasted for more than 12 h and orally administered chlorpromazine hydrochloride (25 mg/kg, 5 ml/kg) to suppress intestinal peristalsis before MRI. All animals of both groups were evaluated by MRI (in vivo) and imaging was performed on the day after final dosing. After the completion of MRI, these animals were euthanized on the same day by exsanguination and necropsied. Mesenteric and pancreatic arteries were collected and evaluated by histopathological examination.

2.4.4. Experiment 4 (in vivo MRI 3 days after final dosing and histopathology)

Animals weighing close to 170 g at the start of FM dosing were assigned to the FM group (N = 8). These animals were fasted for more than 12 h and orally administered chlorpromazine hydrochloride (25 mg/kg, 5 ml/kg) to suppress intestinal peristalsis before MRI. All animals were evaluated by MRI (in vivo) and imaging was performed 3 days after administration of the final dose. After the completion of MRI, these animals were euthanized on the same day by exsanguination and necropsied. Mesenteric and pancreatic arteries were collected and evaluated by histopathological examination.

2.5. MRI

All MRI was performed using an 11.7 T vertical-bore Bruker Avance II imaging system (Bruker BioSpin, Ettlingen, Germany) and the diameter of the volume radiofrequency coil for transmission and reception (Bruker BioSpin) was 10 mm or 33 mm for ex vivo samples and 33 mm for in vivo samples.

For ex vivo MRI, a mesenteric artery sample was immersed in gadolinium (5 mM)-containing phosphate buffered saline for 2 days or longer. Images were acquired using 3D fast low-angle shot (FLASH) with the following scanning parameters: repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) 40 msec/6 msec, flip angle (FA) 90°, 16 × 16 × 8 mm3 field of view (FOV), matrix of 400 × 400 pixels, 200 slices with thickness = 0.04 mm, and 1 NEX or TR/TE 40/6 msec, FA 70°, 20 × 20 × 12.8 mm3 FOV, matrix of 512 × 512 pixels, 256 slices with thickness = 0.05 mm, and 12 NEX. Fat suppression was used to reduce the signal intensity of fat on the images.

For euthanized animals and live animals (in vivo imaging), anatomical images acquired with IntraGate FLASH (Bruker BioSpin) were used for slice positioning with the following scanning parameters: TR/TE 62 msec/1.5 msec, FA 15°, 60 mm FOV, matrix of 256 × 256 pixels, and 5 slices with thickness = 1.1 mm. Images for evaluation of arteritis were acquired using rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) with the following scanning parameters: Rare Factor 8, TR/TE 5000 msec/24.8 msec, 35 × 35 mm2 FOV, matrix of 256 × 256 pixels, 20 slices with thickness = 0.5 mm, and 1 NEX. Fat suppression was used to reduce the signal intensity on the images. During in vivo MRI, rats were given a general anesthetic using 0.5–3 % isoflurane (Wako) administered via a mask covering the nose and mouth. Respiratory signals were monitored using a physiological monitoring system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY), and body temperature was continuously maintained at 36.0 ± 0.5 °C by circulating water through heating pads throughout all experiments. In addition, in in vivo MRI using live animals, a respiratory gating technique was used to minimize the effects of respiration on the images.

2.6. Histopathology

Collected arteries were fixed in 10 % neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), and examined by light microscopy.

2.7. Image analysis

2.7.1. Evaluation of lumen diameter of mesenteric artery in Experiment 1

In the samples of Experiment 1, lumen diameter was measured on the image of MRI using ImageJ (NIH, MD, USA) and on the histopathological image using Imagescope (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) to assess the vasodilatory effects of FM. For each animal, 10 artery sites were analyzed on the images of MRI and 20 artery sites were analyzed on histopathological images.

2.7.2. Quantitative evaluation of signal intensity around the arteries on the images of MRI in Experiment 3

In the samples of Experiment 3, signal intensity around the arteries on the images of MRI was measured using ImageJ. Signal intensity around the arteries was defined as a value derived from the formula shown in parentheses (signal intensity = intensity around the arteries / intensity of the skeletal muscle around the spinal cord). For each animal, 5 arteries were analyzed and the mean value for 5 arteries was defined as the signal intensity of each animal.

2.8. Statistics

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The numerical data were analyzed with two-tailed non-paired t-test to compare the difference between two groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical signs and necropsy

Throughout the dosing period, no animal died or showed clinical signs. At necropsy, no abnormality was observed in any animal.

3.2. Histopathology

3.2.1. Experiment 1 (ex vivo high-resolution MRI and histopathology) and Experiment 2 (MRI after euthanasia and histopathology)

In the FM-administered group, segmental degeneration/necrosis of medial smooth muscle cells accompanied by intramural hemorrhage, infiltration of inflammatory cells into the media and/or perivascular infiltration of inflammatory cells, proliferation of fibroblasts and edema were observed in the mesenteric, pancreatic, and gastrointestinal arteries. In the pancreas, an increase in single cell necrosis was observed in acinar cells around the artery in which arteritis was induced. On the other hand, in the renal arteries, no abnormality was observed. In the vehicle control group, no abnormality was observed in any animal. Table 1 provides a description of the histopathology of the arteries in Experiments 1–4.

Table 1.

Histopathological findings of the arteries in Experiments 1–4.

|

3.2.2. Experiment 3 (in vivo MRI the day after final dosing and histopathology)

In the FM-administered group, segmental degeneration/necrosis of medial smooth muscle cells accompanied by intramural hemorrhage, infiltration of inflammatory cells into the media and/or perivascular infiltration of inflammatory cells, proliferation of fibroblasts and edema were observed in the mesenteric and pancreatic arteries. Perivascular edema was observed in all animals. In the vehicle control group, no abnormality was observed in any animal. The lesions observed in the mesenteric arteries are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Representative histopathological images of the mesenteric arteries with hematoxylin and eosin staining in Experiment 3 (in vivo MRI on the day after final dosing and histopathology). (A and C) Histopathological image of the mesenteric artery in the vehicle control group. Bar, 2 mm in A and 200 µm in C. (B and D) Histopathological image of the mesenteric artery in the FM group. Bar, 2 mm in B and 200 µm in D. (B) In the perivascular area, infiltration of inflammatory cells and proliferation of fibroblasts and edema can be seen. (D) Degeneration/necrosis of medial smooth muscle cells accompanied by intramural hemorrhage and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the media were observed.

3.2.3. Experiment 4 (in vivo MRI 3 days after final dosing and histopathology)

In the FM-administered group, segmental degeneration/necrosis of medial smooth muscle cells accompanied by intramural hemorrhage, infiltration of inflammatory cells into the media and/or perivascular infiltration of inflammatory cells, proliferation of fibroblasts and edema were observed in the mesenteric and pancreatic arteries. Perivascular edema was observed in 4 of 8 animals necropsied 3 days after administration of the final dose and no perivascular edema was observed in the other 4 animals. In the vehicle control group, no abnormality was observed in any animal.

3.3. MRI

3.3.1. Experiment 1 (ex vivo high-resolution MRI and histopathology)

In the vehicle control group, the arterial wall of the mesenteric artery showed uniform and moderate signal intensity, with minor regions of lowered signal intensity observed on the luminal side (Fig. 2, A and C). This low signal was attributed to adhesion of erythrocytes to the vascular endothelium. Conversely, in the FM-administered group, low-intensity areas were observed in the arterial walls (Fig. 2, B and D). These were attributed to infiltration of erythrocytes into the arterial walls, which was observed in histopathological examination (Fig. 2, E and F).

Fig. 2.

Typical images of MRI of mesenteric arteries and histopathological images correspond to the image of MRI in Experiment 1 (ex vivo high-resolution MRI and histopathology). (A and C) Images of MRI of the mesenteric artery in the vehicle control group. Inserts show higher magnification of a cross section of aorta in A and a longitudinal section in C. Bar in insert, 200 µm. (B and D) Image of MRI of the mesenteric artery in the FM group. Inserts show higher magnification of a cross section of aorta in B and a longitudinal section in D. Bar in insert, 200 µm. Low-intensity areas in the arterial wall are indicated by arrowheads. The high signal intensity regions around the artery are indicated with asterisks. (E and F) High magnification of histopathological images of the mesenteric artery in the FM group. Bar, 60 µm in E and 200 µm in F. Erythrocytes infiltrating the arterial wall are indicated with arrowheads. Perivascular edema is indicated with asterisks.

In addition, in the vehicle control group, signal intensity around the artery was low and this was attributed to the presence of fat tissue, which is observed as a low signal in the situation of fat suppression. On the other hand, in the FM-administered group, the signal intensity around the artery was higher than that in the control group (Fig. 2, B and D). The high intensity area was attributed to perivascular edema observed in histopathological examination.

3.3.2. Experiment 2 (MRI after euthanasia and histopathology)

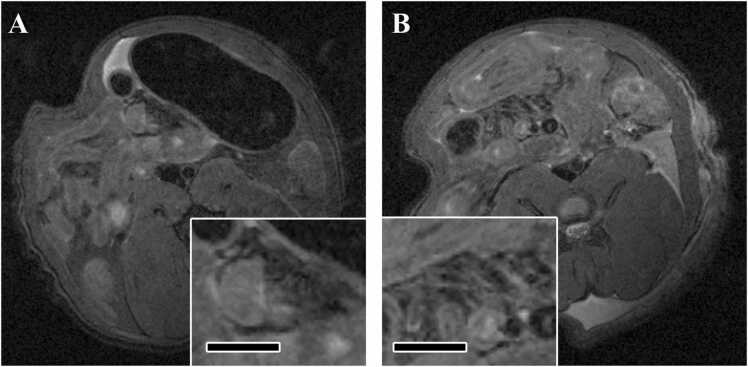

In the euthanized animals, some mesenteric arteries with low signal intensity were observed in the vehicle control group. On the other hand, in the FM-administered group, arteries were clearly visualized and the signal intensity around the artery was higher than that in the control group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Typical images of MRI of mesenteric arteries in euthanized animals in Experiment 2 (MRI after euthanasia and histopathology). (A) Axial image of MRI of the mesenteric artery in the vehicle control group. Inserts show higher magnification of the mesenteric artery. Bar in insert, 3 mm. (B) Axial image of MRI of the mesenteric artery in the FM group. Inserts show higher magnification of the mesenteric artery. Bar in insert, 3 mm. In the FM group, arteries were clearly visualized and the signal intensity around the artery was higher than that in the control group. Arteries are indicated by arrows.

3.3.3. Experiment 3 (in vivo MRI on the day after final dosing and histopathology)

In animals administered chlorpromazine hydrochloride as a peristalsis inhibitor, some mesenteric arteries with low signal intensity were observed in the vehicle control group as also seen in the euthanized animals from Experiment 2. In the mesenteric artery of live animals administered chlorpromazine hydrochloride evaluated on the day after final dosing, a higher signal intensity region around the artery was observed in all animals in the FM-administered group (Fig. 4). However, during the time when peristalsis was not suppressed, arteries were not observed clearly and no change in signal intensity was detected.

Fig. 4.

Typical images of MRI of mesenteric arteries in live animals administered a peristalsis inhibitor and evaluated on the day after final dosing. (A) Axial image of MRI of the mesenteric artery in the vehicle control group. Inserts show higher magnification of the mesenteric artery. Bar in insert, 3 mm. (B) Axial image of MRI of the mesenteric artery in the FM group. Inserts show higher magnification of the mesenteric artery. Bar in insert, 3 mm. In the FM-administered group, arteries were clearly visualized and the signal intensity around the artery was higher than that in the control group. Arteries are indicated by arrows.

3.3.4. Experiment 4 (in vivo MRI 3 days after final dosing and histopathology)

In the mesenteric artery of live animals administered chlorpromazine hydrochloride on the day after final dosing, a high signal intensity region around the artery was observed in 4 of 8 FM-administered animals. Four animals which showed high signal intensity region around the artery were accompanied with perivascular edema confirmed by histopathology. In contrast, in the other 4 animals which did not show the high signal intensity were not accompanied perivascular edema (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Typical images of MRI of mesenteric arteries in live animals administered a peristalsis inhibitor and evaluated 3 days after administration of the final dose. (A) Axial image of MRI of the mesenteric artery in the FM-administered animal without perivascular edema. Inserts show higher magnification of the mesenteric artery. Bar in insert, 3 mm. (B) Axial image of MRI of the mesenteric artery in the FM-administered animal with perivascular edema confirmed by histopathology. Inserts show higher magnification of the mesenteric artery. Bar in insert, 3 mm. A high signal intensity region around the artery was observed only in the animals with perivascular edema. Arteries are indicated by arrows.

3.4. Image analysis

3.4.1. Evaluation of lumen diameter of mesenteric artery in Experiment 1

Based on analysis of the histopathological image, the mean diameter of the vascular lumen in the control group was 66.8 ± 17.7 µm and that of the FM-administered group was 123.6 ± 13.3 µm, revealing that the diameter of the vascular lumen was larger in the FM-administered group than in the control group. In addition, analysis of the image of MRI returned a similar result (the mean diameter of the vascular lumen of the control group was 65.7 ± 12.6 µm and that of the FM-administered group was 111.1 ± 10.7 µm). The bar plots are shown in Fig. 6. The pattern of the bar plot based on analysis of the image of ex vivo MRI was similar to that obtained on analysis of the histopathological image.

Fig. 6.

Bar plots of inner diameter of vascular lumen measured from the images of MRI and histopathological images. In the FM group, dilation of the blood vessel cavity was observed. The results from images of MRI were consistent with those from histopathological images.

3.4.2. Quantitative evaluation of signal intensity around the arteries on the images of MRI in Experiment 3

The mean value of the control group was 0.91 ± 0.11 and the mean value of the FM-administered group was 1.57 ± 0.20, and there was a statistically significant difference between the values of both groups. The maximum value in the control group was 1.05, whereas the minimum value in the FM-administered group was 1.34, which revealed that the signal intensity was clearly higher in the FM-administered group.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the assessment of arteritis in small to medium arteries in rats using MRI. In addition, this is the first time an evaluation of drug-induced arteritis by MRI has been reported.

FM-induced arteritis was detected by histopathological examination following administration of FM at a dose of 100 mg/kg/day for two days. In the mesenteric arterial wall, we observed segmental degeneration/necrosis of medial smooth muscle cells accompanied by intramural hemorrhage and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the media and, in the perivascular area, infiltration of inflammatory cells and proliferation of fibroblasts and edema. These lesions were also observed in the pancreatic and gastrointestinal arteries. The extent and/or frequency of segmental degeneration/necrosis of medial smooth muscle cells accompanied by intramural hemorrhage and infiltration of inflammatory cells into the media in the mesenteric artery were highest among these arteries. On the other hand, in histopathological examination, no lesions in the renal artery were found. In addition, it has been reported that exudation of fibrin and clear evidence of rupture of the internal elastic lamina could not be observed by special stains in rats with the initial 24-hour infusion and 2-week intravenous administration of FM [22].

In the ex vivo MRI study, the MRI showed low-intensity areas and a high signal intensity region around the artery, and these findings were considered to be the result of infiltrating the arterial wall and perivascular edema, respectively. These findings suggest that intramural hemorrhage and perivascular edema induced by fenoldopam can be clearly detected by ex vivo MRI. On the other hand, low-intensity areas observed in the ex vivo MRI, attributed to erythrocytes infiltrating the arterial wall, were not observed in the in vivo MRI. This is probably due to the fact that the resolution of the in vivo MRI is lower than that of the ex vivo MRI. The resolution was not high enough to clearly show the arterial wall in the in vivo MRI, and we therefore assume that the erythrocytes in the arterial wall could not be detected in the in vivo MRI.

From the samples of Experiment 1, an analysis of the histopathological images using Imagescope showed that the diameter of the vascular lumen of the FM-administered group was larger than that of the control group and this is thought to be a change caused by the vasodilatory effect of FM. The results obtained from the images of ex vivo MRI were similar to those obtained with the histopathological images. It can therefore be concluded that, in terms of detecting vasodilatory effects, the accuracy of analysis using images of ex vivo MRI is similar to that using histopathological images.

In the in vivo study, on the images of MRI, the FM-administered group showed a higher signal intensity region around the artery than the control group. High signal intensity was observed not only in euthanized animals but also in live animals administered the peristalsis inhibitor. In addition, high signal intensity was observed in all animals evaluated on the day after final dosing in the FM-administered group. This suggests that arteritis could also be detected by in vivo MRI. Regarding the change in signal intensity around the artery, the signal intensity of the FM-administered group showed a quantitatively significant difference compared to the control group. Therefore, the high signal intensity region around the artery on the image of MRI may serve as a reliable indicator of the presence of arteritis.

In animals examined 3 days after administration of the final dose, a high signal intensity region around the artery was seen in the all of the animals with perivascular edema. On the other hand, high signal intensity was not observed in the animals where perivascular edema was absent. These findings suggest that the perivascular edema observed on histopathology corresponds to the high signal intensity region around the artery on the image of MRI. In addition, we believe that exudation of serous fluid from arteries due to increased vessel wall permeability is identified as perivascular edema on the image of MRI and, as long as the vessel wall remains in a damaged state, arteritis will be accompanied by perivascular edema. These data and consideration also support that detection of the high signal intensity region around the artery by MRI is a reliable indicator of the presence of arteritis.

In contrast, during the period when peristalsis was not suppressed, the arteries could not be observed clearly and no change in signal intensity was observed. As the mesenteric artery is easily moved by peristalsis, it is essential to suppress peristalsis when evaluating arteritis by MRI.

While the mesenteric artery is the predominant site for drug-induced arteritis in rats [17], it was difficult to obtain a clear image because the mesenteric artery is free to move within the abdominal cavity and is strongly affected by respiratory and peristaltic movements. However, as shown in this report, by using a respiratory gating technique and suppressing peristalsis, arteritis in the mesenteric artery can be detected by MRI. Since it was possible to detect arteritis in the mesenteric artery, which is a small- to medium-sized artery, evaluation of arteritis in other small- to medium-sized arteries affected by drug-induced arteritis should be possible.

There are no known specific and sensitive biomarkers of arteritis [13], [15]; however, the high signal intensity region around the artery seen on the images of MRI can be regarded as a translational biomarker candidate because it can be evaluated in in vivo. Peristaltic inhibitors and the respiratory gating technique are also used during intraperitoneal MRI in humans, and humans can consciously pause their own respiration [14], [19]. Therefore, it is possible to perform intraperitoneal MRI in humans under the same conditions used in this study. Our results show that, in the rat, which is a small animal, it is possible to detect arteritis in the mesenteric artery, which is difficult because this artery is not fixed to the retroperitoneum in the abdominal cavity. In addition, a human study on detecting the distribution of arteritis in a large artery (abdominal aorta) by contrast-enhanced MRI has been conducted [10] and delayed contrast-enhanced MRI in Takayasu arteritis can show a high intensity signal in the vessel wall that indicates edema [9]. Therefore, arteritis in small- to medium-sized arteries may be diagnosed even in humans by detecting a high signal intensity region around the artery in the image of MRI.

Although the high signal intensity region around the artery seen on the image of MRI could be a biomarker candidate for drug-induced arteritis, further investigation is needed to verify that the high signal intensity is a reliable biomarker (addition of substances, animals etc.). As part of that, we are currently investigating another example using this method to confirm whether the high signal intensity region around the artery can be detected in arteritis induced by other mechanisms.

Funding

This work was supported by Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd, Japan.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Yumi Tateishi for her histotechnical work.

Handling Editor: Lawrence Lash

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2022.07.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

References

- 1.Anderson D.R., Duryee M.J., Garvin R.P., Boska M.D., Thiele G.M., Klassen L.W. A method for the making and utility of gadolinium-labeled albumin microbubbles. Magn. Reson Imaging. 2012;30:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalmas D.A., Scicchitano M.S., Chen Y., Kane J., Mirabile R., Schwartz L.W., Thomas H.C., Boyce R.W. Transcriptional profiling of laser capture microdissected rat arterial elements: fenoldopam-induced vascular toxicity as a model system. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008;36:496–519. doi: 10.1177/0192623307311400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalmas D.A., Scicchitano M.S., Mullins D., Hughes-Earle A., Tatsuoka K., Magid-Slav M., Frazier K.S., Thomas H.C. Potential candidate genomic biomarkers of drug induced vascular injury in the rat. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2011;257:284–300. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle M.K., Cuellar M.L. Drug-induced vasculitis. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2003;2:401–409. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Y., Zhao M.H. Review article: drug-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrol. (Carlton) 2009;14:33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2009.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez R.J., Lin S.A., Bednar B., Connolly B., LaFranco-Scheuch L., Mesfin G.M., Philip T., Patel S., Johnson T., Sistare F.D., Glaab W.E. Vascular imaging of matrix metalloproteinase activity as an informative preclinical biomarker of drug-induced vascular injury. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017;45:633–648. doi: 10.1177/0192623317720731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Group J.C.S.J.W. Guideline for management of vasculitis syndrome (JCS 2008) Jpn. Circ. Soc. Circ. J. 2011;75:474–503. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-88-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikegami H., Shishido T., Ishida K., Hanada T., Nakayama H., Doi K. Histopathological and immunohistochemical studies on arteritis induced by fenoldopam, a vasodilator, in rats. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2001;53:25–30. doi: 10.1078/0940-2993-00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang L., Li D., Yan F., Dai X., Li Y., Ma L. Evaluation of Takayasu arteritis activity by delayed contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Int J. Cardiol. 2012;155:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato Y., Terashima M., Ohigashi H., Tezuka D., Ashikaga T., Hirao K., Isobe M. Vessel wall inflammation of Takayasu arteritis detected by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: association with disease distribution and activity. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerns W., Schwartz L., Blanchard K., Burchiel S., Essayan D., Fung E., Johnson R., Lawton M., Louden C., MacGregor J., Miller F., Nagarkatti P., Robertson D., Snyder P., Thomas H., Wagner B., Ward A., Zhang J., Expert Working Group on Drug-Induced Vascular I. Drug-induced vascular injury--a quest for biomarkers. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2005;(203):62–87. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louden C., Brott D., Amuzie C.J., Bennet B., Chamanza R. In: Toxicologic pathology: Nonclinical Safety Assessment. second ed. Sahota P.S., Popp J.A., Hardisty J.F., Gopinath C., Bouchard P.R., editors. CRC Press; Florida: 2019. The Cardiovascular System; pp. 743–825. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louden C., Brott D., Katein A., Kelly T., Gould S., Jones H., Betton G., Valetin J.P., Richardson R.J. Biomarkers and mechanisms of drug-induced vascular injury in non-rodents. Toxicol. Pathol. 2006;34:19–26. doi: 10.1080/01926230500512076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu J., Zhou Z., Morelli J.N., Yu H., Luo Y., Hu X., Li Z., Hu D., Shen Y. A systematic review of technical parameters for MR of the small bowel in non-IBD conditions over the last ten years. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:14100. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50501-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mikaelian I., Cameron M., Dalmas D.A., Enerson B.E., Gonzalez R.J., Guionaud S., Hoffmann P.K., King N.M., Lawton M.P., Scicchitano M.S., Smith H.W., Thomas R.A., Weaver J.L., Zabka T.S., Vascular Injury Working Group of the Predictive Safety C. Nonclinical safety biomarkers of drug-induced vascular injury: current status and blueprint for the future. Toxicol. Pathol. 2014;42:635–657. doi: 10.1177/0192623314525686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ni R. Magnetic resonance imaging in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease amyloidosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021:22. doi: 10.3390/ijms222312768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira Bacares M.E. Sampling the rat mesenteric artery. Toxicol. Pathol. 2016;44:1166–1169. doi: 10.1177/0192623316667245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt W.A., Blockmans D. Investigations in systemic vasculitis - the role of imaging. Best. Pr. Res Clin. Rheuma. 2018;32:63–82. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokoro H., Yamada A., Suzuki T., Kito Y., Adachi Y., Hayashihara H., Nickel M.D., Maruyama K., Fujinaga Y. Usefulness of breath-hold compressed sensing accelerated three-dimensional magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) added to respiratory-gating conventional MRCP. Eur. J. Radiol. 2020;122 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.108765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2022 Drug Approval Package: CORLOPAM (fenoldopam mesylate). Drugs@FDA. Silver Spring, MD. Available from: 〈https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=019922〉.

- 21.Waring M.J., Arrowsmith J., Leach A.R., Leeson P.D., Mandrell S., Owen R.M., Pairaudeau G., Pennie W.D., Pickett S.D., Wang J., Wallace O., Weir A. An analysis of the attrition of drug candidates from four major pharmaceutical companies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;(14):475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrd4609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuhas E.M., Morgan D.G., Arena E., Kupp R.P., Saunders L.Z., Lewis H.B. Arterial medial necrosis and hemorrhage induced in rats by intravenous infusion of fenoldopam mesylate, a dopaminergic vasodilator. Am. J. Pathol. 1985;119:83–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.