Abstract

Pueraria candollei var. mirifica (Fabaceae) root (PMR) has recently been developed as a potential selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) in menopausal women. Nowadays, many premenopausal women also take dietary PMR supplements, however, the exact biological effects of PMR have not been evaluated. This study included the application of the OECD guideline 407 for the assessment of 28-day oral exposure to PMR on pituitary-ovarian (PO) axis function and metabolic parameters in the premenopausal rat model. Ovary-intact adult rats were orally administrated with 10, 100, 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg body weight (BW)/day of PMR powder. The positive estrogenic group was given 2 mg 17β-estradiol (E2)/kg BW/day. Serum levels of reproductive hormones, lipid and thyroid parameters, estrous cycle determination, and histomorphometric and histopathological evaluations of the anterior pituitary, ovary, uterus, vagina, mammary gland, and liver were investigated. PMR displayed neutral effects on uterine, vaginal, and body weights, and circulating E2 and prolactin levels. PMR exerted E2-like effects by i) reducing ovarian and increasing hepatic weights, ii) decreasing serum gonadotropins, iii) lowering serum lipids without altering thyroid parameters, iv) increasing the prevalence of abnormal estrous cycles with prolonged estrus, v) increasing nuclear diameter of anterior pituitary cells, vi) decreasing ovarian size and follicular numbers and increasing follicular degeneration, vii) thickening of uterine myometrium and luminal epithelium, and vaginal epithelium, and viii) induction of mammary alveolar hyperplasia and ductal secretion. Unlike E2, the appearance of very small numbers of focal microvesicular steatosis in hepatocytes demonstrated mild toxicity at high PMR doses. This is the first report that high-dose PMR exerted actions exactly like E2 on gonadotrope-ovarian axis function and histology, lipid, and thyroid parameters without affecting uterine and vaginal growth in ovary-intact rats according to OECD guidelines.

Keywords: Pituitary-ovarian axis, Lipid and thyroid, Mammary gland, Liver, Histomorphometric analysis, Endocrine Disruptor

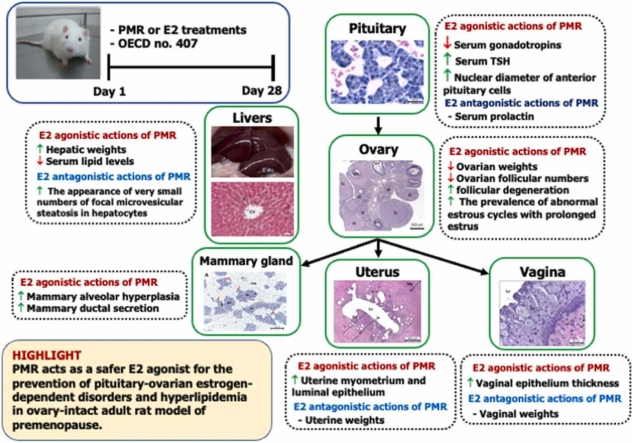

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Pueraria mirifica root exerts E2-antagonistic effects on vaginal size, uterine growth and histomorphology, and plasma E2.

-

•

Pueraria mirifica root possesses E2-agonistic actions on pituitary histomorphology, gonadotropic function, estrous cycle phase and length.

-

•

Pueraria mirifica root exhibits E2-like effects on ovarian size, follicular development, and degeneration.

-

•

Pueraria mirifica root plays an estrogen agonistic role on lipid and thyroid parameters.

-

•

Pueraria mirifica root induces mild hepatic steatosis without changing plasma ALP levels.

1. Introduction

Pueraria candollei Wall. Ex Benth. var. mirifica (Airy Shaw & Suvat.) Niyomdham, an endemic Thai medicinal plant of the family Fabaceae, is considered a phytoestrogen-rich plant [1]. P. mirifica root (PMR) has been widely used for over 100 years in Thai folk medicine as a rejuvenating drug for aged people [1]. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis revealed that the major phytoestrogens found in PMR are puerarin, daidzin, daidzein, genistin, genistein, and miroestrol [2], [3]. In vitro studies revealed that PMR exerts stimulatory ER-agonistic actions on the growth and proliferation of the human mammary carcinoma cell line (MCF-7 cell) [2], [4]. In addition, PMR also inhibits the proliferation of estradiol-induced mesenchymal stem cells [5]. Previous studies in ovariectomized (ovx) rat models demonstrated that PMR stimulates the growth of estrogen-dependent organs, i.e., uterus, vagina, and mammary gland [3], [6], [7]. In addition, PMR also decreases luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels in ovx rats [3]. However, most previous research lacks a positive estrogenic control group and focuses mainly on the effects of PMR on reproductive function in ovx animal models.

Nowadays, many premenopausal women also use commercial dietary PMR supplements and products. Data from rodent models revealed that phytoestrogens influence metabolic parameters, i.e., lipid parameters [(total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglyceride (TG)], thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and thyroid hormones (triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4)) [8], [9], [10]. However, until now, none of the studies has investigated the mechanisms of PMR actions on lipid and thyroid metabolic parameters. In addition, there is no evaluation of the biological mechanisms of PMR action on overall health status. This especially applies to the biological effects of PMR on the pituitary-ovarian (PO) axis function and metabolic parameters in ovary-intact female individuals. The present study is, therefore, aimed at investigating the exact biological effects of PMR on PO axis function and histology, lipid, and thyroid parameters in the ovary-intact adult rat model of premenopause. To clarify the exact estrogen agonistic or antagonistic properties of PMR, the positive E2 control group was included, and a soy-free rat diet was used in this study. According to the international standard methodology of the “Enhanced OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) Test Guideline No. 407”, a 28-day treatment period was employed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Test chemicals

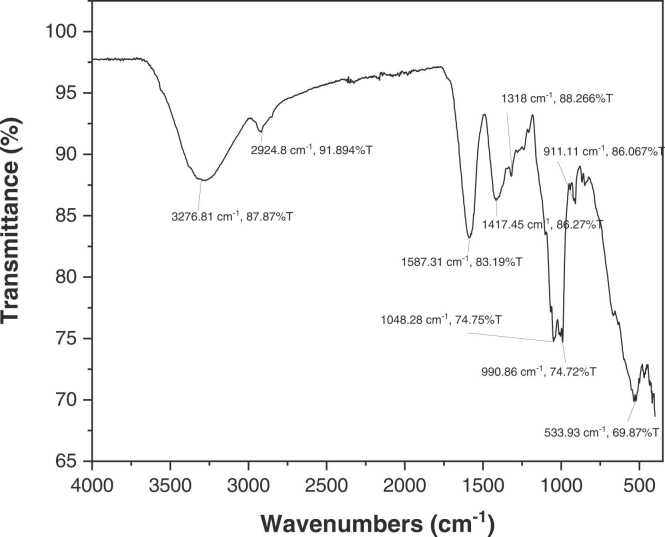

17β-estradiol (C18H24O2; CAS no. 50-28-2) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Extra virgin olive oil was purchased from Sos Cuetara SA (Madrid, Spain). PMR powder was kindly supplied by Associate Professor Dr. Wichai Cherdshewasart from the Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. The infrared spectra of PMR powder samples were recorded on a Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) equipped with the universal ATR (UATR) accessory (Perkin Elmer, USA) and a Diamond/KRS-5 crystal composite (1 bounce). The UATR-FT-IR of a PMR sample was recorded from 32 replicate measurements in the range between 4000 and 400 cm-1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm-1 by using the diamond ATR sampling technique. The PMR sample was measured by using a 0.5 mm UATR shoe and a force gauge of 120 units. A background spectrum was recorded and automatically subtracted by the FT-IR Perkin Elmer spectrum quant software provided by Perkin Elmer (USA). The absorption bands at 3276.81, 2924.8, 1048.28, and 533.93 cm-1 corresponded to the stretching vibrations of O–H [12], C–H [13], C O [13], [14], –C–C–O– [15], respectively. The absorption peaks at 1587.31 and 990.86 cm-1 were attributed to the C C stretching vibration [13], [14]. The bands at 1417.45 and 1318 cm-1 corresponded to –CO stretching vibration [14]. The absorption peak at 911.11 cm-1 was due to the –C–O–C group [14]. FT-IR spectra revealed that PMR powder possessed typical absorption peaks of functional groups found in puerarin [16], daidzin, daidzein [17], genistin, and genistein [18] (Fig. 1). Total isoflavonoid contents in PMR samples were analyzed by HPLC-UV detection and performed on a symmetry C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm) connected with a sensory C18 guard column (Waters Corporation, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [11]. Eluent A was 0.1 % acetic acid, whereas eluent B was acetonitrile (100 %). The flow rate was 1 mL/min with a linear gradient starting with t = 0 min, A 86 %, B 14 %; t = 5 min, A 86 %, B 14 %; t = 9 min, A 76 %, B 24 %; t = 22 min, A 68 %, B 32 %; t = 40 min, A 86 %, B 14 %. The signal was analyzed with a spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, USA) at a wavelength of 254 nm. One kg of PMR powder contained 1708.75 mg of total isoflavonoids content with 960.15 mg as puerarin, 381.05 mg as daidzin, 113.90 mg as genistein, 167.30 mg as genistin, and 86.35 mg as daidzein at the molar ratio of 22.39: 5.87: 1: 4.82: 3.50, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of PMR powder.

2.2. Animals and maintenance

2-month-old ovary-intact Sprague-Dawley female rats (200–300 g) from the National Laboratory Animal Center, Thailand were housed and maintained under standardized conditions (23–25 °C, 12-h dark-light cycle, 50–55 % relative humidity, 16 air change per hour). Animals were allowed free access to a special soy-free rat diet (Ssniff special diet, Germany) and distilled water. Animal experimental design and protocol were conducted in accordance with the OECD No. 407 Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals and the Endocrine Disruptor Screening and Testing Advisory Committee and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Mahasarakham University, Thailand (No. 2558/0014).

2.3. Experimental design

At 3 months old, only virgin rats showing all phases of 4–5 consecutive estrous cycles were weighed (mean BW = 275.98 ± 2.02 g) and randomly divided into eight groups (n = 12/group). Groups I and II were vehicle control groups that received olive oil (CTL-Oil) and double distilled water (CTL-DDW), respectively. Groups III, IV, V, VI, and VII PMR were given PMR powder at doses of 10 (PMR10), 100 (PMR100), 750 (PMR750), 1000 (PMR1000), and 1500 (PMR1500) mg/kg BW/day, respectively. Group VIII was the positive estrogenic control group that received 2 mg E2/kg BW/day. The doses of 10, 100, and 1000 mg PMR/kg BW/day were chosen due to the stimulation of uterine weight in ovx rats [3]. PMR 750 and 1500 mg/kg BW/day have been set between 100 and 1000 mg/kg BW/day, which are less than a range of values based on the maximum tolerated doses, i.e., 2000–16,000 mg/kg BW/day and did not cause adverse effects. Since ingestion is a typical route of human consumption, PMR was administered via oral gavage, and DDW was used as the vehicle. The 2 mg E2/kg BW/day (s.c.) was selected based on our previous studies [6].

2.4. Euthanasia and necropsy

Each animal was anesthetized with a high concentration of carbon dioxide and decapitated with a guillotine. Blood was collected from the trunk and serum samples were acquired by centrifugation at 3000 g for 20 min and immediately stored at − 20 °C for serum analysis. The ovary, uterus, vagina, liver, and pituitary were carefully dissected and trimmed free of fat tissue, and immediately weighed.

2.5. Analysis of serum hormones and lipid parameters

LH, FSH, TSH, and PRL levels were performed by an immunometric immunoassay using immunodiagnostic products reagent packs on the VITROS 3600 Immunodiagnostic System (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, USA). Serum E2 was measured by a competitive immunoassay using immunodiagnostic products reagent packs on the VITROS 3600 Immunodiagnostic System (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, USA). FT3 and FT4 levels were determined by a competitive immunoassay using immunodiagnostic products reagent packs on the VITROS 3600 Immunodiagnostic System (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, USA). TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, and TG levels were determined by an enzymatic colorimetric assay. Serum ALP was measured by a multiple-point rate test. TC and LDL-C concentrations were analyzed using the cholesterol reagent kit and the MULTIGENT direct LDL reagent kit, respectively, on the ARCHITECT c16000 System (Abbott Diagnostics, USA). The VITROS 5,1 FS Chemistry System (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, USA) was used to quantify HDL-C, TG, and ALP concentrations using VITROS chemistry products dHDL, TRIG, and AKLP slides, respectively.

2.6. Determination of estrous cycle status

The determination of estrous cycle status was carried out following the OECD standard protocol [19]. The estrous cycle stage was monitored daily with vaginal cytology. The following are the stages of the rat estrous cycle as determined by the proportions of three major cell types found in the vaginal smear: (a) During proestrus, the vaginal smear was primarily composed of clusters or individuals of rounded-shape, small nucleated epithelial cells with a minor population of large irregular-shaped, flat, anucleated keratinized (cornified) epithelial cells; (b) During estrus, large anucleated cornified epithelial cells were the majority cell population; (c) During diestrus 1 (metestrus), vaginal smear contained similar proportions of very small nucleated leukocytes, large anucleated cornified cells, and small nucleated epithelial cells; and (d) During diestrus 2 (diestrus), vaginal secretion primarily consisted of a leukocyte population [19], [20].

2.7. Histological procedures of the pituitary, ovarian, uterine, vaginal, mammary glands, and hepatic tissues

Tissue samples were fixed in a 10 % neutral buffered formalin pH 7.2 solution for 24–48 h. The tissues were then dehydrated through a concentration series of ethanol, cleared with xylene, and infiltrated with liquid paraffin according to the standard protocols [21], [22]. Tissue samples were cut into transverse sections before being embedded with paraffin in molds. The tissue blocks were trimmed before obtaining the first section of at least 200 µm and subsequently sectioned serially with a rotary microtome (Microm HM315R, MICROM International GmbH, Walldorf, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) at a 5-μm thickness. Afterward, the tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) following established methods [21], [22]. The examinations of histological, histomorphometric, and histopathological structures of target tissues of six randomly selected rats from each group were performed by two people who were uninformed of the treatment groups of tissue sections or the results of each other. At 40x and 100x magnification, the histopathological assessments were observed using a Zeiss Axioscope 7 light microscope coupled with an Axiocam 506 color camera (Carl Zeiss, Germany) and a Leica DM750 light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Switzerland), and photographed using ZEN 2.3 software (Carl Zeiss, Germany) and Leica Application Suite LAS, version 4.5.0 software (Leica Microsystems, Switzerland).

2.8. Anterior pituitary nuclear histomorphometry, ovarian follicular counts, and histopathological analysis

The nuclear area of anterior pituitary cells was measured and performed on three slides per animal. At least 300 measurements were acquired in a randomly selected area at 100x magnification [23]. In each animal, the numbers of ovarian follicles at each stage of development and corpora lutea were counted from three serial sections with the largest diameter for each ovary [22]. The criteria for counting and classification of ovarian follicles and corpus luteum were as defined in the OECD protocol [19] and a previous report [24]. Histopathological evaluation of ovarian tissue was carried out by the standard differential diagnosis of the female rat ovary [25]. The ovarian histopathological endpoints included: 1) the presence of a follicular cyst, which had a thin wall lined by 1–4 layers of flattened or cuboidal granulosa cells with an increased amount of fluid and a lack of an oocyte; 2) the appearance of cytoplasmic vacuolation in theca cells; 3) the occurrence of angiectasis, which could be characterized by the local cystic dilation of pre-existing ovarian blood vessels within the interstitium, especially near the hilus or within developing follicles or corpora lutea; and 4) the observation of polyovular or multiple-oocyte follicles, where two or more oocytes were contained within follicles. The changes in each histopathological endpoint were recorded based on the frequency ranging from minimal to marked, and symbolized as follows: + minimal; ++ mild; +++ moderate; and ++++ marked [26].

2.9. Analysis of uterine histomorphometry and histopathology

In each animal, the uterine histomorphological parameters were assessed, including the height of luminal epithelium (400 ×), the thickness of myometrium, endometrium, and uterine wall (40 ×), and the number of uterine glands (40 ×). These parameters were measured on three slides per rat [27] and evaluated for ten measurements in randomly chosen areas in the middle transversal section [28]. Histopathological diagnosis and evaluation of the uterus were carried out following the standard differential diagnosis of the female rat uterus [25], [27]. The uterine histopathological endpoints included: 1) the presence of squamous metaplasia, which was characterized by the replacement of uterine columnar epithelium with squamous epithelium; and 2) pyometra, which was moderate or severe dilation of the uterine lumen by the accumulation of viscous, purulent, or hemopurulent exudate [25], [27]. The histopathological changes were graded: + was considered minimal; ++, mild; +++, moderate; and ++++, marked [26].

2.10. Analysis of vaginal histomorphometry and histopathology

The epithelial thickness of the vaginal wall was assessed in each rat on three slides [27]. Ten measurements were acquired in randomly selected areas in the middle transversal section (100 ×) [28]. Histopathological evaluations of the vagina were carried out using the standard differential diagnosis of the rat vagina [25]. The presence of keratinization and mucification in the epithelium was the primary criterion. The histopathological alterations were scored on a scale according to the following: +, minimal; ++, mild; +++, moderate; and ++++, marked [26].

2.11. Histopathological evaluation of mammary gland

Histopathological investigations were guided by the standard differential diagnosis of the rat mammary gland [19], [29]. The mammary gland histopathological endpoints included: 1) alveolar hyperplasia, which was defined as an increase in several alveoli with hyperplastic epithelium forming small lobules around ducts; 2) increased secretory material, which was typified by the presence of increased proteinaceous secretory fluid within the alveoli and/or ducts; and 3) ductal ectasia, which could be characterized by dilation of ducts containing proteinaceous secretory fluid (galactoceles). The histopathological changes were graded on a scale according to the following: +, minimal; ++, mild; +++, moderate; and ++++, marked [26].

2.12. Histopathological evaluation of liver

In each animal, three serial sections were taken with the largest diameter obtainable for each liver. The endpoint parameters for hepatic histopathological evaluation were: 1) infiltration of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages in the portal triad; 2) the appearance of bridging/confluent necrosis, focal necrosis, and apoptotic hepatocytes; 3) the appearance of microvesicular and macrovesicular fatty changes, and 4) the presence of hepatocytes in mitosis [21]. The changes in each parameter were assessed using a grading score based upon the severity, ranging from normal to severe, and symbolized as follows: (+) very small amount (1–2 foci); (++) small amount (3–6 foci); (+++) medium amount (7–12 foci); (++++) large amount (> 12 foci); and (+++++) very large amount (diffuse). According to the formal description, a focal lesion was referred to one specific area, or focus, whereas multifocal points were referred to several foci [30].

2.13. Statistical analysis

The data were presented as mean ± S.E.M. Bartlett’s test was performed for the normality and homogeneity of variance, and when not significant, the group mean differences between vehicle control and all treatment groups were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons with the Prism software version 6 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). p-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of PMR on body weight, food consumption, and the relative weights of ovary, uterus, vagina, and liver

Both PMR and E2 significantly reduced food intake, and E2 significantly decreased body weight. PMR 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2 significantly attenuated ovarian weight and increased hepatic weight. Only E2 significantly increased uterine and vaginal weights (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body weights, food intakes, relative organ weights, and serum levels of reproductive hormones in ovary-intact rats administered with vehicle, PMR, or E2 for 28 days.

| Parameters | CTL-Oil | CTL-DDW | PMR10 | PMR100 | PMR750 | PMR1000 | PMR1500 | E2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | ||||||||

| Initial | 273.6 ± 7.3 | 277.3 ± 4.8 | 274.9 ± 7.8 | 274.1 ± 5.6 | 276.0 ± 5.5 | 277.1 ± 6.5 | 277.6 ± 5.5 | 277.0 ± 4.1 |

| Final | 297.5 ± 6.7 | 287.8 ± 5.4 | 285.4 ± 7.7 | 275.8 ± 6.4 | 282.0 ± 8.2 | 284.0 ± 9.4 | 283.3 ± 5.5 | 271.2 ± 5.5* |

| Food intake (gram/animal/day) | 13.16 ± 0.19 | 13.48 ± 0.14# | 13.00 ± 0.14## | 11.65 ± 0.21## | 11.98 ± 0.23## | 12.07 ± 0.17## | 11.88 ± 0.31## | 11.42 ± 0.28** |

| Organ weights (g/g BW × 100 g) | ||||||||

| Ovary | 0.038 ± 0.002 | 0.041 ± 0.001 | 0.038 ± 0.001 | 0.039 ± 0.003 | 0.030 ± 0.001# | 0.029 ± 0.001# | 0.029 ± 0.002# | 0.029 ± 0.002** |

| Uterus | 0.201 ± 0.021 | 0.220 ± 0.023 | 0.210 ± 0.034 | 0.268 ± 0.045 | 0.245 ± 0.011 | 0.280 ± 0.026 | 0.261 ± 0.012 | 0.655 ± 0.038** |

| Vagina | 0.042 ± 0.003 | 0.046 ± 0.004 | 0.046 ± 0.002 | 0.049 ± 0.003 | 0.049 ± 0.004 | 0.045 ± 0.005 | 0.047 ± 0.004 | 0.060 ± 0.003** |

| Liver | 3.125 ± 0.047 | 3.176 ± 0.063 | 3.189 ± 0.067 | 3.249 ± 0.094 | 3.810 ± 0.127## | 4.101 ± 0.156## | 4.197 ± 0.108## | 4.102 ± 0.086** |

| Serum hormone levels | ||||||||

| LH (mIU/mL) | 2.40 ± 0.37 | 2.42 ± 0.24 | 2.65 ± 0.29 | 2.93 ± 0.32 | 1.61 ± 0.27# | 1.60 ± 0.26# | 1.46 ± 0.32# | 0.49 ± 0.15** |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 2.12 ± 0.29 | 2.25 ± 0.24 | 2.44 ± 0.26 | 2.51 ± 0.30 | 1.89 ± 0.26 | 1.32 ± 0.25# | 1.30 ± 0.25# | 1.00 ± 0.10** |

| Estradiol (ng/mL) | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.09 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 1.24 ± 0.07** |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 63.83 ± 10.23 | 64.93 ± 9.53 | 64.60 ± 10.12 | 65.48 ± 9.98 | 65.65 ± 10.17 | 65.15 ± 9.38 | 64.65 ± 10.05 | 189.10 ± 11.74** |

Notes: – Values are mean ± S.E.M. (n = 12 rats/group).

– *p < 0.05 vs. CTL-Oil, **p < 0.01 vs. CTL-Oil, #p < 0.05 vs. CTL-DDW, ##p < 0.01 vs. CTL-DDW determined by a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc multiple comparison test.

3.2. Effects of PMR on reproductive hormone levels

PMR 750, 1000, 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2 significantly reduced circulating LH concentrations. Rats treated with PMR 1000, 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2 had significantly lowered serum FSH levels. Only E2 significantly elevated plasma estradiol and PRL levels (Table 1).

3.3. Effects of PMR on serum ALP, lipid, and thyroid parameters

PMR doses of 100, 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day, as well as E2, significantly reduced levels of TC, HDL-C, LDL-C, and the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio. PMR 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2 significantly elevated TG levels. PMR 1500 mg/kg BW/day and E2 significantly increased TSH levels. PMR and E2 did not significantly affect ALP, FT3, and FT4 levels, as well as the FT3/FT4 ratio (Table 2).

Table 2.

Serum levels of lipid parameters, ALP, TSH, T3, and T4 in ovary-intact rats subacutely administered with vehicle, PMR, or E2 for 28 days.

| Parameters | CTL-Oil | CTL-DDW | PMR10 | PMR100 | PMR750 | PMR1000 | PMR1500 | E2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (mg/dL) | 83.33 ± 7.99 | 76.50 ± 6.40 | 69.33 ± 7.89 | 58.00 ± 5.18# | 41.67 ± 8.73## | 36.67 ± 9.31## | 33.83 ± 7.99## | 23.83 ± 8.69** |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 87.50 ± 7.89 | 85.67 ± 6.98 | 74.17 ± 8.45 | 58.50 ± 6.41# | 51.50 ± 6.97## | 47.83 ± 6.43## | 46.33 ± 7.42## | 49.17 ± 7.95** |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 18.50 ± 2.75 | 15.67 ± 2.11 | 12.83 ± 2.01 | 9.67 ± 1.33# | 7.67 ± 1.61# | 6.33 ± 1.20## | 6.00 ± 1.67## | 4.50 ± 1.61** |

| TG (mg/dL) | 119.30 ± 11.66 | 90.17 ± 6.37 | 96.50 ± 8.42 | 103.00 ± 6.93 | 110.00 ± 6.04# | 121.00 ± 8.45# | 125.00 ± 6.79## | 192.00 ± 12.61** |

| LDL-C/HDL-C ratio | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01# | 0.13 ± 0.01## | 0.13 ± 0.01## | 0.12 ± 0.02## | 0.08 ± 0.02** |

| ALP (U/L) | 113.9 ± 9.7 | 116.7 ± 9.0 | 119.1 ± 9.0 | 122.1 ± 8.6 | 125.7 ± 9.3 | 129.5 ± 9.0 | 131.4 ± 9.5 | 128.8 ± 9.4 |

| TSH (mIU/mL) | 0.0625 ± 0.0197 | 0.0707 ± 0.0138 | 0.0672 ± 0.0151 | 0.0998 ± 0.0140 | 0.1112 ± 0.0223 | 0.1237 ± 0.0243 | 0.1713 ± 0.0267## | 0.2925 ± 0.0491** |

| Free T3 (ng/mL) | 0.0053 ± 0.0010 | 0.0048 ± 0.0006 | 0.0051 ± 0.0006 | 0.0043 ± 0.0006 | 0.0045 ± 0.0006 | 0.0048 ± 0.0005 | 0.0055 ± 0.0010 | 0.0050 ± 0.0009 |

| Free T4 (ng/mL) | 0.0286 ± 0.0056 | 0.0260 ± 0.0045 | 0.0326 ± 0.0043 | 0.0347 ± 0.0043 | 0.0331 ± 0.0056 | 0.0395 ± 0.0067 | 0.0359 ± 0.0079 | 0.0261 ± 0.0062 |

| Free T3/free T4 ratio | 0.1800 ± 0.0251 | 0.1987 ± 0.0324 | 0.1791 ± 0.0403 | 0.1795 ± 0.0435 | 0.1882 ± 0.0211 | 0.1746 ± 0.0223 | 0.1642 ± 0.0244 | 0.2492 ± 0.0370 |

Notes: – Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M.

– **p < 0.01 vs. CTL-Oil, #p < 0.05 vs. CTL-DDW, ##p < 0.01 vs. CTL-DDW determined by a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc multiple comparison test.

3.4. Effects of PMR on estrous cycle phase and length

The number of days in proestrus was significantly decreased in PMR750-, PMR1000-, PMR1500-, and E2-treated animals. The number of days in estrus was significantly increased in rats treated with PMR 1000, 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2. The number of days in diestrus was significantly decreased in rats treated with PMR 100, 750, 1000, 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2. The number of estrous cycles was significantly decreased, and the estrous cycle length was significantly increased in rats treated with PMR 100, 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2. None of the rats treated with PMR 1000, 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2 cycled normally. On the day of necropsy, 22 % of oil-treated controls were in estrus, whereas 78 % of the others were in diestrus. DDW-treated controls were in diestrus (80 %), estrus (10 %), and proestrus (10 %). 30 %, 33 %, 33%, 44 %, and 50 % of rats treated with PMR 10, 100, 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day, respectively, were in estrus, whereas 70 % of PMR10-treated rats, 67 % of PMR100-treated rats, 67 % of PMR750-treated rats, 56% of PMR1000-treated rats, and 50 % of PM1500-treated rats were in diestrus. In contrast, 100 % of E2-treated rats were in estrus (Table 3).

Table 3.

The duration of estrous cycle phase of ovary-intact rats exposed to either vehicle, PMR, or E2 for 28 consecutive days.

| Treatments | Days in proestrus | Days in estrus | Days in diestrus | Number of cycles | Cycle lengtha | Rats cycling normallyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL-Oil | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 6.8 ± 0.3 | 16.7 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 12/12 |

| CTL-DDW | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 16.9 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 12/12 |

| PMR10 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 16.3 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 8/12 |

| PMR100 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 17.9 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.3## | 8.6 ± 0.9## | 3/12 |

| PMR750 | 3.2 ± 0.5## | 9.2 ± 1.1 | 16.6 ± 1.3 | 2.7 ± 0.4## | 11.6 ± 1.9## | 1/12 |

| PMR1000 | 2.7 ± 0.4## | 12.6 ± 1.3## | 13.8 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2## | 13.8 ± 2.0## | 0/12 |

| PMR1500 | 3.4 ± 0.6# | 14.3 ± 1.0## | 11.4 ± 1.2## | 2.3 ± 0.3## | 11.8 ± 1.9## | 0/12 |

| E2 | 3.0 ± 0.3** | 14.8 ± 1.2** | 11.2 ± 1.3** | 1.8 ± 0.2** | 16.1 ± 2.5** | 0/12 |

Notes: – Values are mean ± S.E.M. (n = 12 rats/group).

– **p < 0.01 vs. CTL-Oil, #p < 0.05 vs. CTL-DDW, ##p < 0.01 vs. CTL-DDW defined by a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc multiple comparison test.

A cycle length is identified as the number of days from one estrus to the next estrus [40].

An intact normally cycling rat is defined as having a mean of cycle length between 4 and 6 days. Data represents as incidence rate [40].

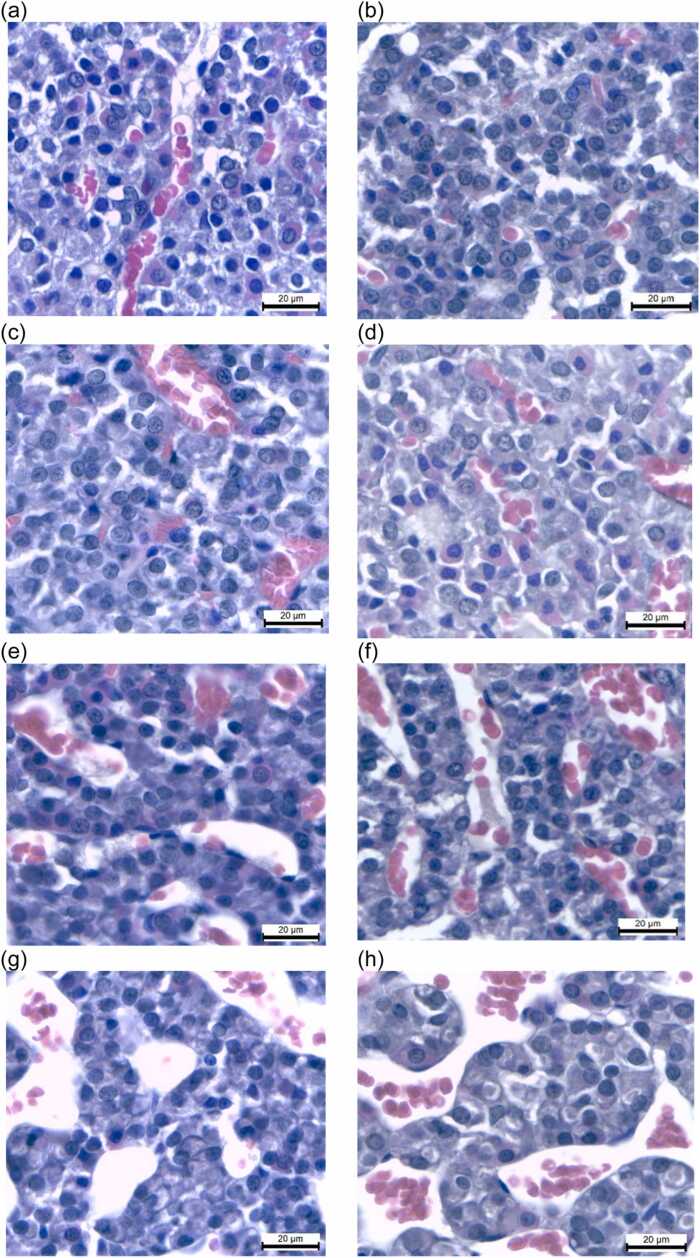

3.5. Effects of PMR on anterior pituitary histology and histomorphometry

The anterior pituitary histological characteristics of vehicle controls showed normal structures comprised of tight, highly branching cords of cells with a thin basal lamina separated by sinusoids and a network of capillaries (Fig. 2). Treatments with E2 and PMR at 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day increased vascularity and sinusoid dilation (Fig. 2e–h). The mean nuclear area was significantly increased in rats receiving PMR 100, 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day and E2 (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Histomicrographs (H&E) of anterior pituitary tissues of ovary-intact rats treated with (a) CTL-Oil, (b) CTL-DDW, (c) PMR10, (d) PMR100, (e) PMR750, (f) PMR1000, (g) PMR1500, and (h) E2 for 28 days. The scale bar corresponds to 20 µm.

Table 4.

Histomorphometric parameters of pituitary, uterus, and vagina in ovary-intact rats subacutely treated with vehicle, PMR, or E2 for 28 days.

| Parameters | CTL-Oil | CTL-DDW | PMR10 | PMR100 | PMR750 | PMR1000 | PMR1500 | E2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pituitary | ||||||||

| Nuclear area (μm2) | 21.18 ± 0.45 | 19.49 ± 0.36 | 20.49 ± 0.36 | 21.72 ± 0.64## | 22.74 ± 0.69## | 22.09 ± 0.65## | 22.02 ± 0.46## | 24.57 ± 0.59** |

| Uterus | ||||||||

| Total uterine wall thickness (μm) | 1304.27 ± 54.70 | 1435.31 ± 60.36 | 1344.10 ± 52.95 | 1333.73 ± 36.58 | 1504.36 ± 25.18 | 1601.73 ± 38.43# | 1647.68 ± 56.17# | 1097.73 ± 17.30** |

| Myometrial thickness (μm) | 447.49 ± 32.87 | 428.36 ± 17.31 | 478.98 ± 18.81 | 548.77 ± 13.55## | 687.55 ± 35.12## | 740.92 ± 22.06## | 731.98 ± 33.16## | 574.94 ± 15.05** |

| Endometrial thickness (μm) | 866.17 ± 41.49 | 909.40 ± 56.27 | 917.51 ± 33.28 | 782.42 ± 27.89 | 807.49 ± 48.81 | 916.43 ± 62.36 | 927.74 ± 26.06 | 563.43 ± 19.23** |

| Luminal epithelial cell height (μm) | 19.19 ± 1.94 | 19.98 ± 1.53 | 23.35 ± 1.45 | 19.25 ± 1.00 | 25.37 ± 1.16## | 27.10 ± 1.83## | 27.29 ± 1.67## | 28.54 ± 2.18* |

| Area of uterine lumen (× 105 μm2) | 7.54 ± 9.30 | 6.33 ± 1.26 | 8.16 ± 1.47 | 9.25 ± 2.05 | 5.20 ± 0.52 | 9.40 ± 1.88 | 9.01 ± 0.63 | 21.69 ± 3.92** |

| Number of uterine gland | 51.82 ± 5.54 | 43.60 ± 6.43 | 54.08 ± 7.72 | 28.69 ± 3.61 | 39.13 ± 3.63 | 42.08 ± 4.17 | 41.58 ± 2.38 | 18.75 ± 2.58** |

| Vagina | ||||||||

| Epithelial cell height (μm) | 80.02 ± 5.74 | 97.10 ± 6.15 | 85.70 ± 3.89 | 99.77 ± 9.35 | 172.40 ± 15.75## | 137.20 ± 14.12# | 141.00 ± 16.15# | 116.00 ± 5.01** |

Notes: – Values are mean ± S.E.M.

– *p < 0.05 vs. CTL-Oil, **p < 0.01 vs. CTL-Oil, #p < 0.05 vs. CTL-DDW, ##p < 0.01 vs. CTL-DDW determined by a One-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc multiple comparison test.

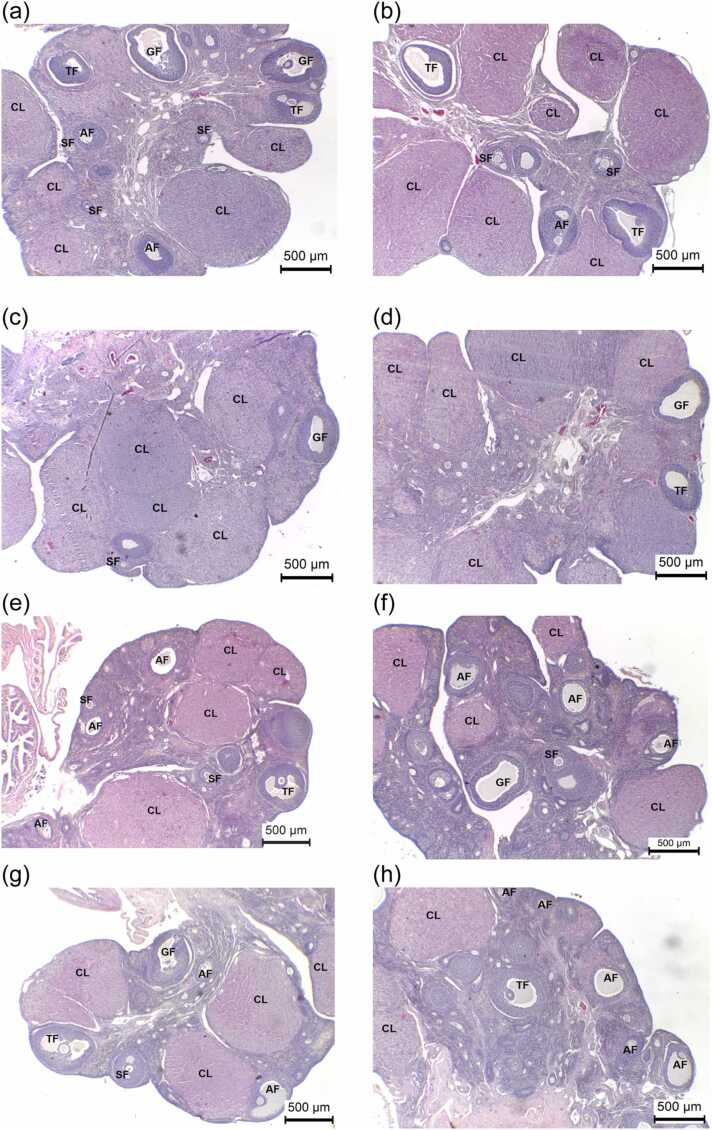

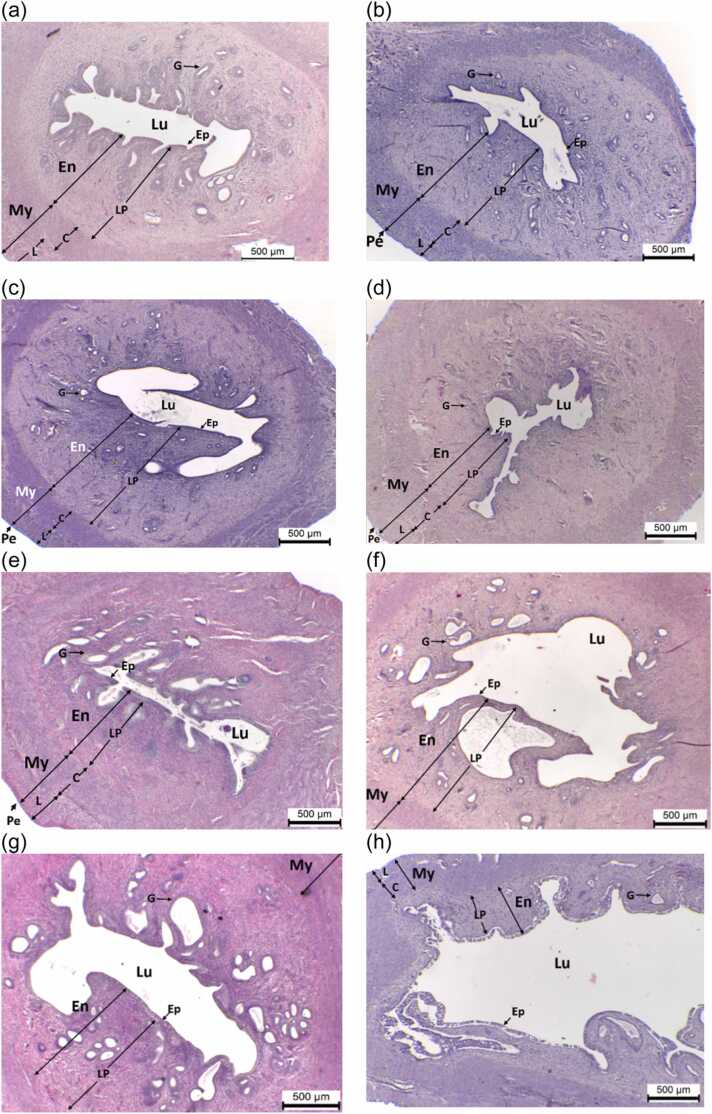

3.6. Effects of PMR on ovarian histology, histomorphometry, and histopathology

The E2 group had a lower number of primary follicles. PMR1000-, PMR1500-, and E2-exposed rats exhibited significantly decreased numbers of tertiary follicles. The average numbers of Graafian follicles in PMR750-, PMR1000-, PMR1500-, and E2-treated animals were significantly reduced. The numbers of corpora lutea significantly declined in rats treated with PM 750, 1000, 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2. Rats treated with PMR 750, 1000, 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2 revealed a significant increase in the average number of atretic follicles (Fig. 3e–h). The primordial follicle and secondary follicle counts did not differ significantly between the treatment and control groups (Table 5). Histopathological investigation of the ovarian tissues of rats exposed to PMR and E2 did not detect follicular cysts, cytoplasmic vacuolation in theca cells, angiectasis, or polyovular follicles (Table 6).

Fig. 3.

Representative ovarian tissues (H&E) of rats treated with (a) CTL-Oil, (b) CTL-DDW, (c) PMR10, (d) PMR100, (e) PMR750, (f) PMR1000, (g) PMR1500, and (h) E2 for 28 days. Secondary follicle (SF); tertiary follicle (TF); Graafian follicle (GF); Corpora lutea (CL); and Atretic follicle (AF). The scale bar represents 500 µm.

Table 5.

Ovarian follicle counts of adult female rats exposed to vehicle, PMR, or E2 for 28 days.

| Numbers and stages of follicles | CTL-Oil | CTL-DDW | PMR10 | PMR100 | PMR750 | PMR1000 | PMR1500 | E2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primordial follicle | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| Primary follicle | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.1** |

| Secondary follicle | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.3 |

| Tertiary follicle | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2## | 1.2 ± 0.1## | 1.6 ± 0.3* |

| Graafian follicle | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.1# | 1.2 ± 0.1# | 1.3 ± 0.2# | 1.1 ± 0.1** |

| Corpora lutea | 8.9 ± 0.4 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 0.6# | 5.9 ± 0.6## | 4.5 ± 0.2## | 3.8 ± 0.3** |

| Atretic follicle | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.3## | 2.6 ± 0.1## | 2.3 ± 0.2## | 2.6 ± 0.3## |

Notes: – Values are mean ± S.E.M. (n = 12 rats/group).

– *p < 0.05 vs. CTL-Oil, **p < 0.01 vs. CTL-Oil, #p < 0.05 vs. CTL-DDW, ##p < 0.01 vs. CTL-DDW determined by a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc multiple comparison test.

Table 6.

Types and incidences of histopathological changes found in the ovary, uterus, vagina, and mammary gland of rats treated either with vehicle, PMR, or E2 for 28 days.

| Histopathological changes | Treatments |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL-Oil | CTL-DDW | PMR10 | PMR 100 | PMR750 | PMR1000 | PMR1500 | E2 | |

| Ovaries | ||||||||

| Follicular cysts | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

| Vacuolation in the theca cells | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

| Angiectasis | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

| Polyovular follicles | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

| Uterus | ||||||||

| Squamous metaplasia | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

| Pyometra | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

| Glandular dilation | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 3/6 (+) | 4/6 (+) | 4/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) |

| Vagina | ||||||||

| Mucification in epithelium | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 2/6 (+++) | 5/6 (++++) | 6/6 (++++) | 6/6 (++++) | 0/6 (-) |

| Keratinization in epithelium | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 6/6 (++++) |

| Mammary gland | ||||||||

| Alveolar hyperplasia | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 2/6 (++) | 4/6 (+++) | 5/6 (+++) | 6/6 (+++) | 6/6 (+++) |

| Increased secretory material | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 2/6 (+) | 4/6 (+) | 5/6 (++) | 6/6 (++) | 6/6 (+++) |

| Ductal ectasia | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

Remarks: - Data represent the number of animals affected, evaluated, and severity grade, respectively. - None; + Minimal; ++ Mild; +++ Moderate; and ++++ Marked.

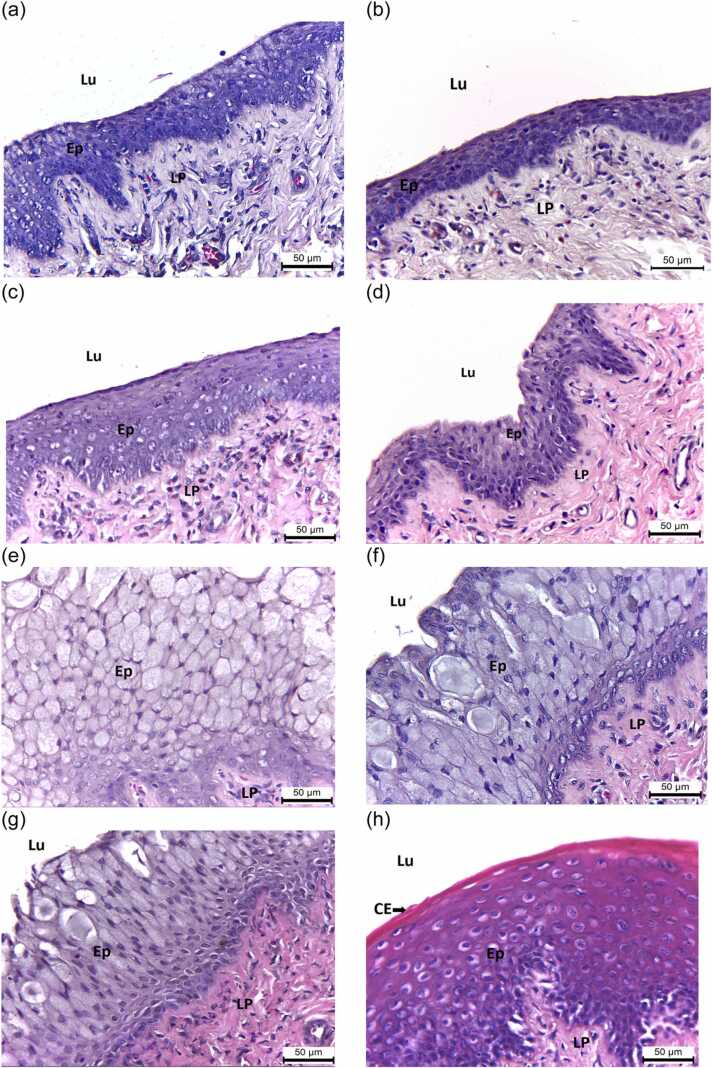

3.7. Effects of PMR on uterine histology, histomorphometry, and histopathology

Histological study of the uterus in all groups showed the typical characteristics of three layers, i.e., endometrium, myometrium, and perimetrium (Fig. 4a–h). While PMR 1000 and 1500 mg/kg BW/day significantly increased, E2 significantly decreased the mean total wall thickness (Table 4). PMR doses of 100, 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day, as well as E2, dramatically increased myometrial thickness (Table 4). Only E2 significantly reduced endometrial thickness (Table 4). PMR 750, 1000, 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2 significantly increased the luminal epithelial height (Table 4). Only E2 significantly increased the luminal area and decreased the number of uterine glands (Table 4). No squamous metaplasiaor pyometra was found in any group (Table 6). In addition, uterine glandular dilation was observed in rats treated with PMR 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day, and E2, but in very small amounts (Table 6).

Fig. 4.

Representative uterine tissues (H&E) of ovary-intact rats administered with (A) CTL-Oil, (B) CTL-DDW, (C) PMR10, (D) PMR100, (E) PMR750, (F) PMR1000, (G) PMR1500, and (H) E2 for 28 days. Endometrium (En); Myometrium (My); Perimetrium (PE); lumen (Lu); Epithelium (Ep); Lamima propria (LP); Gland (G); Circular muscle layer (C); and Longitudinal muscle layer (L). Scale bar = 500 µm.

3.8. Effects of PMR on vaginal histology, histomorphometry, and histopathology

The vaginal epithelium was lined by stratified squamous epithelium with no keratinization or mucification (Fig. 5a, b). The epithelium appeared to have more layers in the PMR750, PMR1000, and PMR1500 groups (Fig. 5e–g). The vaginal epithelium of the E2 group displayed a typical squamous multilayered epithelium with cornification in the upper layers (Fig. 5h). Only the E2 group had a significant increase in vaginal keratinization without mucification (Fig. 5h, Table 6). No keratinization was found in PMR-treated rats (Fig. 5c–g). Vaginal mucification was observed in rats treated with PMR 100, 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day (Fig. 5e–g, Table 6). PMR 750, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg BW/day and E2 significantly increased the mean thickness of vaginal epithelium (Table 4).

Fig. 5.

Representative histomicrographs (H&E) of vaginal tissues of ovary-intact rats administered with (a) CTL-Oil, (b) CTL-DDW, (c) PMR10, (d) PMR100, (e) PMR750, (f) PMR1000, (g) PMR1500, and (h) E2 for 28 days. Lu, lumen; Ep, epithelium; CE, cornified epithelium; and LP, lamina propria. Scale bar = 50 µm. Note for the presence of mucification in PMR-treated rats (f) and keratinization in E2-treated rats (h).

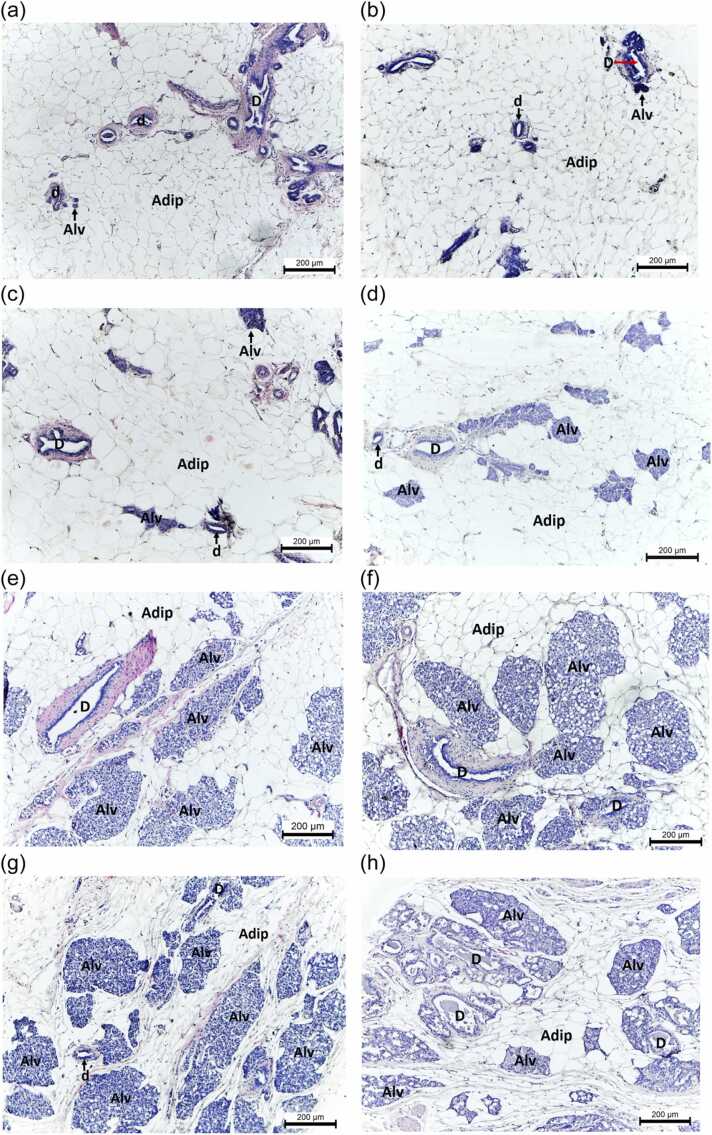

3.9. Effects of PMR on mammary gland histology and histopathology

The mammary gland consisted of scattered tubular branching ducts and glandular alveoli (Fig. 6a, b). Both ducts and alveoli were lined with one or two layers of the cuboidal epithelium (Fig. 6a, b). The glandular tissue of the mammary gland was surrounded by connective tissue and embedded in adipose tissue (Fig. 6a, b). Alveolar hyperplasia was seen in a small number of PMR100-treated rats and a moderate number of PMR750, PMR1000, PMR1500, and E2-treated rats (Fig. 6e–h, Table 6). The incidence of secretory material in the alveoli and ducts was dose-dependently increased in rats given PMR and was highest in rats that received E2 (Fig. 6h, Table 6). There was no ductal ectasia in any group.

Fig. 6.

Histomicrographs (H&E) of mammary gland tissues from ovary-intact rats given (a) CTL-Oil, (b) CTL-DDW, (c) PMR10, (d) PMR100, (e) PMR750, (f) PMR1000, (g) PMR1500, and (h) E2 for 28 days. Alv, alveoli; D, duct; d, ductule; and Adip, adipocytes. The scale bar represents 200 µm. Take note of the presence of alveolar hyperplasia in the PMR (f-g) and E2-treated rats (h).

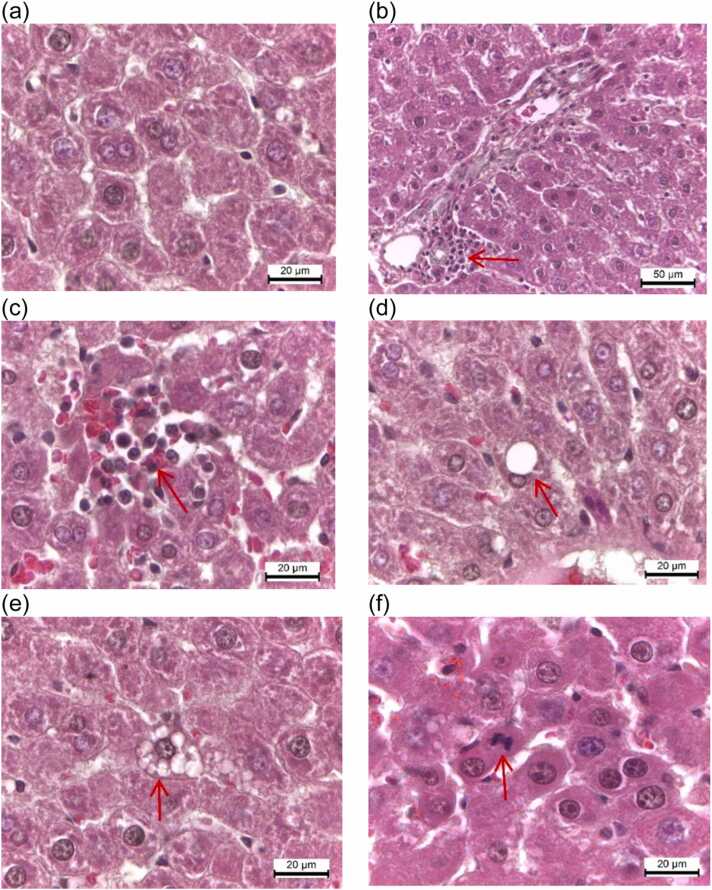

3.10. Effects of PMR on hepatic histology and histopathology

In all groups, the liver sections revealed normal histoarchitecture, with polyhedral-shaped hepatocytes, central veins, sinusoids, and portal triads (Fig. 7a). All groups showed very small numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages infiltrating the portal triads without bridging or confluent necrosis and apoptotic hepatocytes (Fig. 7b, Table 7). A very small amount (1–2 foci) of focal necrosis was presented in rats treated with PMR and E2 (Fig. 7c). Macrovesicular fatty changes occurred in the periportal zone of all groups, but with a very small amount (1–2 foci) (Fig. 7d). Only a slight microvesicular fatty change was observed in the periportal zone of PMR100-, PMR750-, PMR1000-, and PMR1500-treated rats (Fig. 7e). In addition, the presence of hepatocytes in mitosis was noted in PMR- and E2-treated groups (Fig. 7f).

Fig. 7.

Light photomicrographs (H&E) of hepatic tissues of vehicle control and treatment groups. (a) The vehicle control group shows normal liver parenchyma. (b) All groups reveal the very small numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages infiltrating the portal triads. (c) A very small amount of focal necrosis is present in rats treated with PMR and E2. (d) Macrovesicular steatosis occurs in the periportal zone of all groups, but with a very small amount. (e) Microvesicular steatosis in the periportal zone is observed to be very low in PMR100-, PMR750-, PMR1000-, and PMR1500-treated rats. (f) The presence of hepatocytes in mitosis is noted in PMR and E2-treated groups. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Table 7.

Histopathological findings of liver tissues of vehicle control-, PMR-, and E2-treated rats in a 28-day assay.

| Histopathological changes | Treatments |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL-Oil | CTL-DDW | PMR 10 | PMR 100 | PMR 750 | PMR 1000 | PMR 1500 | E2 | |

| Portal triad | ||||||||

| Infiltrate of neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages | 3/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) | 5/6 (+) | 5/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) | 5/6 (+) | 6/6 (+) | 4/6 (+) |

| Liver lobules | ||||||||

| Bridging/confluent necrosis | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

| Focal necrosis | 1/6 (+) | 2/6 (+) | 5/6 (+) | 5/6 (+) | 6/6 (+) | 6/6 (+) | 6/6 (+) | 4/6 (+) |

| Apoptotic hepatocyte | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) |

| Microvesicular fatty change | 2/6 (+) | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 3/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) | 2/6 (+) | 2/6 (+) |

| Macrovesicular fatty change | 3/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) | 1/6 (+) | 2/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) | 4/6 (+) | 2/6 (+) |

| Hepatocytes in mitosis | 0/6 (-) | 0/6 (-) | 1/6 (+) | 2/6 (+) | 4/6 (+) | 2/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) | 3/6 (+) |

Notes:- Data represent the number of animals affected, evaluated, and severity grade, respectively. - None; + Very small amount (1–2 foci); ++ Small amount (3–6 foci); +++ Medium amount (7–12 foci); ++++ Large amount (> 12 foci); and +++++ Very large amount (Diffuse).

4. Discussion

The strengths of this study include the application of the OECD guideline protocol for a 28-day investigation of PO axis function and histology in ovary-intact adult rats upon PMR exposure using the assessment of PO axis and thyroid hormones, plasma reproductive and lipid profiles, estrous cycle phase and length, histomorphometric and histopathological alterations of the anterior pituitary, ovary, uterus, vagina, mammary gland, and liver. To clarify the exact estrogen agonistic or antagonistic properties of PMR, the positive E2 control group was included, and a soy-free rat diet was used in this study. E2 reduced food intake and body weight, whereas PMR decreased food intake but did not affect body weight. In female rats, the reasons for the reduction in food consumption involve both peripheral and central estrogen agonistic mechanisms [31], [32]. PMR had a similar peripheral mechanism to E2 in modulating lipid and thyroid parameters. E2 exerts a potent central ERα-agonistic mechanism on suppressing the activity of the preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus, resulting in a marked decrease in food intake, leading to the significant weight loss of E2-treated rats [31]. Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that PMR exerted a weak central anorectic E2-like effect on hypophagia in adult female rats.

PMR did not affect, but E2 stimulated uterine and vaginal growth. In addition, the ovarian weights were reduced in rats treated with PMR and E2. Hence, this is the first study revealing the exact E2-antagonistic actions of high PMR dosages on the size of the uterus and vagina and E2-like actions on the ovarian weight. The high PMR doses exerted E2-like actions on the stimulation of uterine luminal epithelial and myometrial thickness. PMR increased the total uterine wall thickness without affecting endometrial thickness, luminal area, or uterine gland number. In comparison, E2 significantly decreased the mean total uterine wall, endometrial thickness, and the number of uterine glands, and increased the mean luminal area. Upon E2 exposure, the uterine horns become dilated with the increased accumulation of fluid, causing the enlargement of the lumen and subsequent thinned uterine wall [25], [33]. These data revealed that PMR did not exert estrogenic actions on endometrial growth, the total thickness of uterine wall and lumen, or uterine gland number, resulting in an unaltered uterine weight in PMR-treated rats. High PMR doses exerted an E2-like action on the increments of vaginal epithelial cell height. Histopathological findings showed a significant increase in vaginal mucification in rats treated with PMR, and this was typically found in association with persistent diestrus (see discussion below) [34]. On the contrary, E2 led to an increase in vaginal keratinization. The occurrence of increased vaginal epithelial thickness along with keratinization following estrogen exposure was due to the elevation of circulating estrogens [34], and this was predominantly found only in the E2-treated rat (see discussion below).

LH and FSH levels were significantly decreased in rats treated with PMR, as well as with E2. PMR did not alter, whereas E2 dramatically elevated PRL levels. Therefore, high-dose PMR exerted an E2-like action on the function of gonadotrophs, and PMR had an E2-antagonistic effect on lactotrophs in ovary-intact rats. The current results for high-dose PMR represent new findings of its potent E2-like actions on the developed changes in LH and FSH levels, leading to the abnormal estrous cycle phase (i.e., shortened proestrus and diestrus, and extended estrus), decreasing the number of estrous cycles, and increasing the estrous cycle length. As previously noted, ovarian follicular toxicity in rodents is an adverse consequence of the significant LH/FSH reductions upon estrogen exposure [35]. Therefore, high-dose PMR exerted an E2-like action on the induction of ovarian follicular degeneration, reduction of folliculogenesis, and luteinization process. Notably, high PMR doses and E2 induced shortened vaginal proestrus and extended estrus. The above events indicate the potential of PMR to delay LH surge, impair ovulation and follicular maturity, and decrease subsequent fertility, as previously noted for E2 administration [19], [36], [37]. Despite the profound E2-like effects of high-dose PMR on LH/FSH suppression and ovarian follicular disruption, circulating estradiol levels remained unchanged. The cytoplasmic vacuolation in the sex steroid-producing theca interna cells was not observed in PMR exposure groups, demonstrating unaltered endogenous steroidogenesis [19], [25]. These data demonstrated that PMR did not directly modulate the synthesis of ovarian estrogens or their metabolism. In addition, the absence of follicular cysts and angiectasis was noted, indicating that PMR was not associated with the induction of polycystic ovarian syndrome symptoms in ovary-intact females [25], [38].

Estrogens have potent pituitary mitogenic activity as well as transcriptomic effects on LHβ, FSHβ, and PRL mRNA expression [31], [39]. In the current study, there was a significant effect of PMR and E2 on LH, FSH, and PRL secretion, and this could be associated with the occurrence of the increase in anterior pituitary cell nuclear size. Exposure to estrogens can result in alveolar hyperplasia and increased secretory material in the mammary gland [19], [27], [29], [40]. The alveolar hyperplasia and elevated secretory material were increased dose-dependently in rats treated with PMR as well as E2. Thus, this is the first evidence suggesting the additional E2-like effects of PMR on increasing pituitary cell nuclear size and elevation of alveolar hyperplasia and secretory material in the mammary gland of intact rats.

PMR displayed the exact E2-like favorable effects on lowering plasma levels of TC, lipoproteins, and LDL-C/HDL-C ratio. PMR caused a significant elevation in serum TG levels, but the effect was nearly two-fold lower than that of E2. Previous studies demonstrated that E2, at concentrations that exert a potent effect on PRL stimulation, had significant lowering effects on the adipose tissue TG lipase activity, which contributes to the higher TG concentrations in plasma [41]. In this study, E2 caused a significant elevation of PRL levels, whereas PMR showed no effect. The hepatic histopathological analysis revealed that E2 and PMR did not affect the intrahepatic TG synthesis and accumulation (see discussion below). Therefore, PMR displayed a weak E2-like action on increased TG biosynthesis through the decreased extrahepatic TG lipase activity.

Both PMR and E2 exerted mild effects on the induction of mitotic activity in hepatocytes. Previous research has shown that exposure to E2 can cause mitotic stimulation of hepatocytes, thus enhancing liver regeneration and growth [42], [43]. These data indicated the implications of PMR and E2 on the increased liver weights in this study. The hepatic fatty change, or steatosis, reflects impaired TG synthesis and elimination and can be induced by estrogen exposure [44], [45]. The focal microvesicular fatty change was seen but at very low levels in the periportal zone of hepatic tissues of high-dose PMR-treated rats, indicating the mild hepatic toxicity of high-dose PMR. However, PMR induction of microvesicular steatosis did not affect hepatic apoptotic cell death. Additionally, focal macrovesicular fatty change was observed in very small amounts in all groups, demonstrating that neither PMR nor E2 increased hepatic TG synthesis and accumulation. Moreover, no significant change in serum ALP levels in any group was noted. The typical histopathological features of toxic hepatitis in rats include the appearance of portal area inflammation, apoptotic hepatocytes, focal necrosis, and bridge/confluent necrosis [21], [46]. PMR and E2 caused a very small amount of focal necrosis similar to that found in the vehicle control treatment, but no bridging or confluent necrosis and apoptotic hepatocytes were observed. Therefore, subacute PMR and E2 treatment did not cause toxic hepatitis in ovary-intact females. In addition, this study revealed that the high-dose PMR exerted an E2-like action on thyrotrophs via stimulating TSH release but did not affect thyroid toxicity due to the lack of the typical pattern of thyroid toxicant, i.e., elevated TSH levels along with reduced T3 and/or T4 levels [47].

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our findings strongly supported the conclusion that in the ovary-intact rat model of premenopause, PMR did not exhibit estrogen agonistic effects on the growth and histology of the uterus and vagina, or endogenous estradiol levels, which are amongst the desired SERM properties used for adult women with intact uteri in estrogen replacement therapy (ERT). In addition, PMR exhibited profound PO axis E2-agonistic actions on anterior pituitary histomorphology and gonadotropic function, ovarian size, follicular development, and degeneration, estrous cycle stage and length, and mammary gland histology. The findings of marked anti-hyperlipidemic E2-like activity and mild hepatic toxicity of high-dose PMR without altering thyroid parameters indicate a safer therapeutic agent for the prevention of hyperlipidemia. Renewed emphasis on PMR as the desired SERM for ERT as well as a dietary antioxidant for the prevention of pituitary-ovarian estrogen-dependent disorders or cancers and hyperlipidemia led to the consideration of whether the chronic E2-agonistic actions of PMR may present remarkable clinical advantages for young women with intact uteri and ovaries, and this warrants further investigations.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

All authors have contributed to the experimental conception and design and writing. Mallika SRASRI and Panida LOUTCHANWOOT performed animal treatments, experiments, euthanasia, and necropsy. Mallika SRASRI and Panida LOUTCHANWOOT carried out the serum, histopathological, and histomorphometric analyses, and data collection. Mallika SRASRI and Prayook SRIVILAI conducted structural, statistical, and genetic analyses. Panida LOUTCHANWOOT and Prayook SRIVILAI contributed to data analysis and interpretation, review and editing, and supervision. All authors have contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

In this research, the animal experimental design and procedures were conducted in accordance with the OECD No. 407 Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals and the Endocrine Disruptor Screening and Testing Advisory Committee. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Mahasarakham University, Thailand (No. 2558/0014).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (Grant number: 88/2562/2) and Mahasarakham University (Grant number: 6105031/1/2561). The authors would like to extend grateful thanks to Dr. Adrian Roderick Plant for English language support, and the editors and the reviewers for their invaluable comments and constructive guidance.

Handling Editor: Dr. L.H. Lash

Data Availability

The data will be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1.Malaivijitnond S. Medical applications of phytoestrogens from the Thai herb Pueraria mirifica. Front. Med. 2012;6:8–21. doi: 10.1007/s11684-012-0184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chansakaow S., Ishikawa T., Sekine K., Okada M., Higuchi Y., Kudo M., Chaichantipyuth C. Isoflavonoids from Pueraria mirifica and their estrogenic activity. Planta Med. 2000;66:572–575. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malaivijitnond S., Kiatthaipipat P., Cherdshewasart W., Watanabe G., Taya K. Different effects of Pueraria mirifica, a herb containing phytoestrogens, on LH and FSH secretion in gonadectomized female and male rats. J. Pharm. Sci. 2004;96:428–435. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj04029x. 〈http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15599108〉 (Accessed 13 October 2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherdshewasart W., Cheewasopit W., Picha P. The differential anti-proliferation effect of white (Pueraria mirifica), red (Butea superba), and black (Mucuna collettii) Kwao Krua plants on the growth of MCF-7 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin T.C., Wang K.H., Kao A.P., Chuang K.H., Kuo T.C. Pueraria mirifica inhibits 17beta-estradiol-induced cell proliferation of human endometrial mesenchymal stem cells. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;56:765–769. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherdshewasart W., Kitsamai Y., Malaivijitnond S. Evaluation of the estrogenic activity of the wild Pueraria mirifica by vaginal cornification assay. J. Reprod. Dev. 2007;53:385–393. doi: 10.1262/jrd.18065. 〈http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17229996〉 (Accessed 16 October 2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kakehashi A., Yoshida M., Tago Y., Ishii N., Okuno T., Gi M., Wanibuchi H. Pueraria mirifica exerts estrogenic effects in the mammary gland and uterus and promotes mammary carcinogenesis in Donryu rats. Toxins. 2016;8 doi: 10.3390/toxins8110275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Böttner M., Christoffel J., Rimoldi G., Wuttke W. Effects of long-term treatment with resveratrol and subcutaneous and oral estradiol administration on the pituitary-thyroid-axis. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2006;114:82–90. doi: 10.1055/S-2006-923888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Böttner M., Christoffel J., Wuttke W. Effects of long-term treatment with 8-prenylnaringenin and oral estradiol on the GH-IGF-1 axis and lipid metabolism in rats. J. Endocrinol. 2008;198:395–401. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loutchanwoot P., Srivilai P., Jarry H. The influence of equol on the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and hepatic lipid metabolic parameters in adult male rats. Life Sci. 2015;128:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherdshewasart W., Panriansaen R., Picha P. Pretreatment with phytoestrogen-rich plant decreases breast tumor incidence and exhibits lower profile of mammary ERalpha and ERbeta. Maturitas. 2007;58:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng W., Shi J., Zhang X., Lian H., Wang Q., Peng Y. Effects of peanut shell and skin extracts on the antioxidant ability, physical and structure properties of starch-chitosan active packaging films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;152:137–146. doi: 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2020.02.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szycher M. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Fla: 2013. Szycher’s Handbook of Polyurethanes (Online) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prusty K., Barik S., Swain S.K. Functionalized Graphene Nanocomposites and Their Derivatives: Synthesis, Processing and Applications. 2019. A corelation between the graphene surface area, functional groups, defects, and porosity on the performance of the nanocomposites; pp. 265–283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang S., Liu Z., Liu Y., Jiao Y. Effect of molecular weight on conformational changes of PEO: an infrared spectroscopic analysis. J. Mater. Sci. 2015;50:1544–1552. doi: 10.1007/S10853-014-8714-1/FIGURES/8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tao H.Q., Meng Q., Li M.H., Yu H., Liu M.F., Du D., Sun S.L., Yang H.C., Wang Y.M., Ye W., Yang L.Z., Zhu D.L., Jiang C.L., Peng H.S. HP-β-CD-PLGA nanoparticles improve the penetration and bioavailability of puerarin and enhance the therapeutic effects on brain ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Naunyn Schmiede Arch. Pharm. 2013;386:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s00210-012-0804-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhalla Y., Chadha K., Chadha R., Karan M. Daidzein cocrystals: an opportunity to improve its biopharmaceutical parameters. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/J.HELIYON.2019.E02669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannavà C., Crupi V., Ficarra P., Guardo M., Majolino D., Mazzaglia A., Stancanelli R., Venuti V. Physico-chemical characterization of an amphiphilic cyclodextrin/genistein complex. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010;51:1064–1068. doi: 10.1016/J.JPBA.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Part 3: FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM, Series on Testing and Assessment. OECD Publishing; Paris: 2009. Guidance document for histologic evaluation of endocrine and reproductive tests in rodents.〈https://www.oecd.org/chemicalsafety/testing/series-testing-assessment-publications-number.htmhttps://www.oecd.org/chemicalsafety/testing/series-testing-assessment-publications-number.htm〉 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcondes F.K., Bianchi F.J., Tanno A.P. Determination of the estrous cycle phases of rats: some helpful considerations. Braz. J. Biol. 2002;62:609–614. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842002000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zlatkovic J., Todorovic N., Tomanovic N., Boskovic M., Djordjevic S., Lazarevic-Pasti T., Bernardi R.E., Djurdjevic A., Filipovic D. Chronic administration of fluoxetine or clozapine induces oxidative stress in rat liver: a histopathological study. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014;59:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcondes R.R., Carvalho K.C., Duarte D.C., Garcia N., Amaral V.C., Simões M.J., lo Turco E.G., Soares J.M., Baracat E.C., Maciel G.A.R. Differences in neonatal exposure to estradiol or testosterone on ovarian function and hormonal levels. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2015;212:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeng Y.-J., Kochukov M., Nauduri D., Kaphalia B.S., Watson C.S. Subchronic exposure to phytoestrogens alone and in combination with diethylstilbestrol – pituitary tumor induction in Fischer 344 rats. Nutr. Metab. 2010;7:40. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruz G., Barra R., González D., Sotomayor-Zárate R., Lara H.E. Temporal window in which exposure to estradiol permanently modifies ovarian function causing polycystic ovary morphology in rats. Fertil. Steril. 2012;98:1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dixon D., Alison R., Bach U., Colman K., Foley G.L., Harleman J.H., Haworth R., Herbert R., Heuser A., Long G., Mirsky M., Regan K., van Esch E., Westwood F.R., Vidal J., Yoshida M. Nonproliferative and proliferative lesions of the rat and mouse female reproductive system. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 2014;27:1S–107S. doi: 10.1293/tox.27.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirsky M.L., Sivaraman L., Houle C., Potter D.M., Chapin R.E., Cappon G.D. Histologic and cytologic detection of endocrine and reproductive tract effects of exemestane in female rats treated for up to twenty-eight days. Toxicol. Pathol. 2011;39:589–605. doi: 10.1177/0192623311402220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimoldi G., Christoffel J., Seidlova-Wuttke D., Jarry H., Wuttke W. Effects of chronic genistein treatment in mammary gland, uterus, and vagina. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115 Suppl.:S62–S68. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rachoń D., Vortherms T., Seidlová-Wuttke D., Menche A., Wuttke W. Uterotropic effects of dietary equol administration in ovariectomized Sprague-Dawley rats. Climacteric. 2007;10:416–426. doi: 10.1080/13697130701624757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudmann D., Cardiff R., Chouinard L., Goodman D., Küttler K., Marxfeld H., Molinolo A., Treumann S., Yoshizawa K. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse mammary, Zymbal’s, preputial, and clitoral glands. Toxicol. Pathol. 2012;40:7S–39S. doi: 10.1177/0192623312454242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thoolen B., Maronpot R.R., Harada T., Nyska A., Rousseaux C., Nolte T., Malarkey D.E., Kaufmann W., Küttler K., Deschl U., Nakae D., Gregson R., Vinlove M.P., Brix A.E., Singh B., Belpoggi F., Ward J.M. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse hepatobiliary system. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010;38:5S–81S. doi: 10.1177/0192623310386499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loutchanwoot P., Vortherms T. Effects of puerarin on estrogen-regulated gene expression in gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator of ovariectomized rats. Steroids. 2018;135:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pantaleao T.U., Mousovich F., Rosenthal D., Padron A.S., Carvalho D.P., da Costa V.M. Effect of serum estradiol and leptin levels on thyroid function, food intake and body weight gain in female Wistar rats. Steroids. 2010;75:638–642. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’connor J.C., Cook J.C., Craven S.C., van Pelt C.S., Obourn J.D. An in vivo battery for identifying endocrine modulators that are estrogenic or dopamine regulators. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1996;33:182–195. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinbach T.J., Patrick D.J., Cosenza M.E. Humana Press; New York, United States: 2019. Toxicologic Pathology for Non-Pathologists. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medigovic I.M., Zivanovic J.B., Ajdzanovic V.Z., Nikolic-Kokic A.L., Stankovic S.D., Trifunovic S.L., Milosevic Vl, Nestorovic N.M. Effects of soy phytoestrogens on pituitary-ovarian function in middle-aged female rats. Endocrine. 2015;50:764–776. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0691-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe J.M., Burack E., Wright A.W. The estrous cycle and associated phenomena in a strain of rats characterized by a high incidence of mammary tumors together with observations on the effects of advancing age on these phenomena. Am. J. Cancer Res. 1940;38:383–398. doi: 10.1158/ajc.1940.383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bridges G.A., Mussard M.L., Burke C.R., Day M.L. Influence of the length of proestrus on fertility and endocrine function in female cattle. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2010;117:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chapman J.C., Min S.H., Freeh S.M., Michael S.D. The estrogen-injected female mouse: new insight into the etiology of PCOS. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2009;7:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw N.D., Histed S.N., Srouji S.S., Yang J., Lee H., Hall J.E. Estrogen negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion: evidence for a direct pituitary effect in women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95:1955–1961. doi: 10.1210/JC.2009-2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biegel L.B., Flaws J.A., Hirshfield A.N., O’Connor J.C., Elliott G.S., Ladies G.S., Silbergeld E.K., van Pelt C.S., Hurtt M.E., Cook J.C., Frame S.R. 90-day feeding and one-generation reproduction study in Crl:CD BR rats with 17β-estradiol. Toxicol. Sci. 1998;44:116–142. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamosh M., Hamosh P. The effect of estrogen on the lipoprotein lipase activity of rat adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 1975;55:1132–1135. doi: 10.1172/JCI108015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher B., Gunduz N., Saffer E.A., Zheng S. Relation of estrogen and its receptor to rat liver growth and regeneration. Cancer Res. 1984;44:2410–2415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Biondo-Simoes Mde L., Erdmann T.R., Ioshii S.O., Matias J.E., Calixto H.L., Schebelski D.J. The influence of estrogen on liver regeneration: an experimental study in rats. Acta Cir. Bras. 2009;24:3–6. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502009000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Begriche K., Massart J., Robin M.A., Borgne-Sanchez A., Fromenty B. Drug-induced toxicity on mitochondria and lipid metabolism: mechanistic diversity and deleterious consequences for the liver. J. Hepatol. 2011;54:773–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang X., Schnackenberg L.K., Shi Q., Salminen W.F. In: R.C.B.T.-B. Gupta T., editor. Academic Press; Boston: 2014. Chapter 13 – hepatic toxicity biomarkers; pp. 241–259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishak K., Baptista A., Bianchi L., Callea F., De Groote J., Gudat F., Denk H., Desmet V., Korb G., MacSween R.N., et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Connor J.C., Frame S.R., Ladics G.S. Evaluation of a 15-day screening assay using intact male rats for identifying antiandrogens. Toxicol. Sci. 2002;69:92–108. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/69.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available from the corresponding author upon request.