Highlights

-

•

Metabolite profiling of cyanobacterial biofilms revealed dynamic changes.

-

•

An-Tr biofilm recorded increased sugars, reduced amino acids compared to An.

-

•

Heat map analyses showed a unique clustering of An-Tr.

-

•

Distinct modulation of fatty acids, sugars, and amino acids in An-PW5.

-

•

C—N metabolism of biofilms regulated significantly over individual partners.

Keywords: Amino acids, Biofilms, Cyanobacterium, Metabolism, Regulation, Sugars

Abstract

Cyanobacteria and their biofilms are used as biofertilizing options to improve plant growth, soil fertility, and grain quality in various crops, however, the nature of metabolites involved in such interactions is less explored. The present investigation compared the metabolite profiles of cyanobacterial biofilms: Anabaena torulosa- Trichoderma viride (An-Tr) and A. torulosa- Providencia sp. (An-PW5) against the individual culture of A. torulosa (An) using untargeted gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy. Metabolites were identified using the NIST mass spectral library and the relative peak area of cultures analysed, after normalization with an internal standard, ribitol. An-Tr biofilm recorded approximately 66.85% sugars, with increased quantity and numbers of sugars and their conjugates, which included maltose, lactose, and d-mannitol, but decreased amino acids concentrations, attributable to the effect of Tr as partner. Heat map and cluster analysis illustrated that An-Tr biofilm possessed a unique cluster of metabolites. Partial least square-discriminate analysis (PLS-DA) and pathway analyses showed distinct modulation in terms of metabolites and underlying biochemical routes in the biofilms, with both the partners- PW5 and Tr eliciting a marked influence on the metabolite profiles of An, leading to novel cyanobacterial biofilms. In the An-PW5 biofilm, the ratios of sugars, lactose, mannitol, maltose, mannose, and amino acids serine, ornithine, leucine and 5‑hydroxy indole acetic acid were significantly higher than An culture. Such metabolites are known to play an important role as chemoattractants, facilitating robust plant -microbe interactions. This represents a first-time study on the metabolite profiles of cyanobacterial biofilms, which provides valuable information related to their significance as inoculants in agriculture.

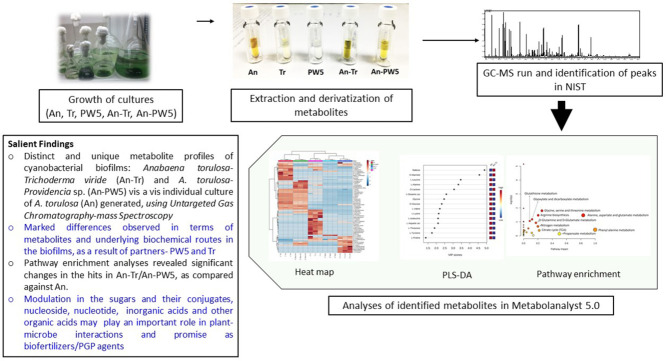

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- PCC

The Pasteur Culture Collection of Cyanobacteria

- UV

Ultra Violet light

- EPS

Extracellular polysaccharides

- ITCC

Indian Type Culture Collection

- TMS

Trimethylsilyl

- MSTFA

N-methyl N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide

- PLSDA

Partial least square discriminate analysis

- VIP

Variable importance in projection

1. Introduction

Cyanobacteria are oxygenic photoautotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can photosynthesize and assimilate CO2 into a variety of biochemical compounds through a wide range of metabolic pathways (Fogg, 1956; Garcia-Pichel, 1998; Do Nascimento et al., 2019). Most of the metabolites produced by cyanobacteria are required for purposes other than growth and reproduction such as sensing, defense, and combating biotic and abiotic stresses (Alawiye and Babalola, 2021, Rastogi and Sinha, 2009). Light and carbon dioxide are two crucial abiotic factors for photosynthetic prokaryotes like cyanobacteria to thrive normally, any small change in these factors alters the intracellular metabolites instantaneously (Tomitani et al., 2006; Maruyama et al., 2019).

Metabolomics is a powerful tool to ascertain variations in metabolite levels in response to various environmental cues (Schwarz et al., 2013). It is well established that metabolites bridge the gap between genotype and phenotype of an organism (Schrimpe-Rutledge et al., 2016) and metabolite profiles mirror the cellular activities, hence, they can provide useful information regarding the beneficial effects of inoculants on soil and plant-related activities. Both intracellular and extracellular metabolomes have been investigated in several cyanobacteria, including Anabaena variabilis PCC 7937 (Singh et al., 2008), Nostoc commune (Ehling-Schulz et al., 1997), Calothrix sp. (Hartmann et al., 2015), Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Werner et al., 2019), Leptolyngbya sp. PCC 7376 (Baran et al., 2013), and Chlorogloeopsis fritschii PCC 6912 (Portwich et al., 2000). The metabolome of C. fritschii has been studied in detail as it is of industrial significance (Balasundaram et al., 2012; Kultschar, 2020), particularly, C. fritschii PCC 6912 exposed to ultraviolet radiation (UV-A and UV-B) (Kultschar et al., 2019; 2021).

Cyanobacteria are known to produce sugars, amino acids, auxins, vitamins, and phytohormones, which helps in stimulating plant growth (Karthikeyan et al., 2007, Misra and Kaushik, 1989, Obana et al., 2007, Rastogi and Sinha, 2009). In agriculture, cyanobacteria and cyanobacteria- based formulations are known to have several benefits as they improve soil stability (Peng and Bruns, 2019; Prasanna et al., 2021a), fix atmospheric nitrogen (Pereira et al., 2009, Singh, 1961, Venkataraman, 1972), provide protection against pests and diseases (Bao et al., 2021, Mahawar et al., 2020, Wiegand and Pflugmacher, 2005) , play an important role in the alleviation of salinity and drought (Sneha et al., 2021) and biofortification of plant parts, including produce (Nishanth et al., 2021a; Rana et al., 2012; Shivay et al., 2022). As biofertilizers, they play a critical role in improving the availability of macro- and micronutrients, besides enriching soil carbon through photosynthesis. Cyanobacteria are excellent biofilm formers, being extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) producers (Rossi and Phillips, 2016; Bharti et al., 2017; Periera et al. 2019; Nishanth et al., 2021b). This facet stimulated the development of biofilms with cyanobacteria and compatible beneficial bacteria and/or fungi (Prasanna et al., 2011, 2021a), which brought about significant enhancement in the yield of several crops, and fortification of soil and produce (Prasanna et al., 2014; Shahane et al., 2020a, 2020b; Sharma et al., 2021). These biofilms were found to perform much better, as compared to monocultures, illustrating, perhaps a synergy or additive effects among the functional attributes of the partners. Therefore, in order to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of nutrient enrichment in soil, and improving their availability, the differences in the metabolite profiles of the biofilm (An-Tr, An-PW5) and An were investigated using untargeted gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy. The regulation of different components in the profiles of cyanobacterial biofilms, An-Tr and An-PW5 compared to individual partners, using untargeted gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy was expected to gain more insights into the benefits of their use as inoculants in agriculture.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Microbial cultures and growth conditions

To study the differences in metabolites of laboratory-developed cyanobacterium-based biofilms, we selected An-Tr (Anabaena torulosa - Trichoderma viride ITCC2211) and An-PW5 (A. torulosa - Providencia sp.) that have plant growth-promoting activities, including nutrient biofortification in several crop plants (Adak et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2021). The cultures used in this include Anabaena torulosa (An), Trichoderma viride ITCC2211 (Tr), and Providencia sp. (PW5). A. torulosa (GenBank Accession no. GU396091) and Providencia sp. (GenBank Accession no. FJ866760) which were procured from the Division of Microbiology, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi, India; they are deposited as NAIMCC—C-00345 and NAIMCC—C-00557 (National Agriculturally Important Culture Collection -NAIMCC, ICAR-National Bureau of Agriculturally Microorganisms-NBAIM, India) respectively. Tr was obtained from Indian Type Culture Collection (ITCC), Division of Pathology, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi, India. A. torulosa was grown in N-free BG-11 medium (Stanier et al., 1971) statically at 27 ± 2 °C under white light (50–55 μmol photons m−2 s−1) with light and dark cycles of 16:8 h for 3 weeks at 10% inoculation rate. T. viride ITCC 2211 (Tr) was grown in potato dextrose broth at 30 ± 2 °C for 1 week under static conditions. Providencia sp. (PW5) was firstly grown at 30 ± 2 °C for 24 h in a mechanical shaker (100 rpm) at 107 cfu ml−1. The biofilms An-Tr and An-PW5 were developed as previously optimized by Prasanna et al. (2011) where Tr and PW5 were inoculated into one week actively grown An culture, such that 104 cfu ml−1 and 107 cfu ml−1 were obtained for An-Tr and An-PW5 biofilm preparation respectively, and grown under same conditions for 2 weeks after the inoculation of partners.

2.2. Experimental design and harvesting of cultures

The cultures were grown in triplicate in completely randomized design (CRD). The cyanobacterium, A. torulosa, An-Tr, and An-PW5 were harvested at 3 weeks after inoculation for An, and 2 weeks after inoculation of partners for biofilms respectively. The fungus- Trichoderma viride ITCC2211 was grown in Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB), harvested after 7 days, and Providencia sp. was grown in Nutrient Broth (NB) and harvested after 24 h, corresponding to their respective log phase of growth. The harvested cultures were then flash frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.3. Chemical reagents

Methanol, water, and chloroform are of LC-MS grade from Honeywell; Internal standard ribitol (adonitol), methoxamine HCl, and pyridine bought from Sigma, and N-methyl N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) from SRL.

2.4. Sample preparation for GC–MS analysis

Preparation of microbial samples for Gas Chromatography- Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis was performed as described previously by Kundu et al. (2018). About, 250 mg of liquid nitrogen frozen sample was taken in a 2 mL centrifuge tube and extracted with 480 µL pure methanol and 20 µL ribitol (adonitol – 0.2 mg mL−1) was added as an internal standard. The contents were shaken vigorously for 2 min and then heated at 70 °C for 15 min followed by adding an equal volume of LC-MS grade water and mixed thoroughly. Chloroform (250 µL) was added to and mixed vigorously. The mixture was then centrifuged at 2200 xg for 10 min at room temperature (appx. 25 °C). After centrifugation, the upper phase was transferred to a new 2 mL centrifuge tube and dried in a speed vacuum rotator at 35 °C. The dried pellet was then redissolved in 40 µL methoxamine hydrochloride in pyridine (20 mg mL−1) and incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. Derivatization of the sample was carried out by the addition of 60 µL N-methyl N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The derivatized sample of metabolites (100 µL) was then transferred to an insert containing a GC–MS glass vial and stored at 4 °C until GC–MS analysis.

2.5. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of metabolites

The metabolite sample analysis was performed in Shimadzu GC–MS-QP2010™ coupled with an autosampler-auto injector (AOC-20si) and an SH-Rxi.5Sil MS capillary column (30 m x 0.25 µm film thickness x 0.25 µm internal diameter; Restek Corporation, USA). A derivatized sample of 2 µL volume was injected into the inlet at 250 °C with a split ratio of 1:5. Purging of the standard septum was performed after sample injection at 3 mL min−1 and carrier gas helium at 1 mL min−1 attained a constant flow rate. Initially, the oven temperature was programmed at 80 °C for 2 min, ramped up to 250 °C at 5 °C min−1, withheld for 2 min and further ramped to 300 °C at 10 °C min−1, and withheld for 24 min. Ionization was done at 70 eV in an electron impact mode and the masses were scanned for full spectra from 40 to 600 m/z with a scan speed of 2000. The solvent cut time was at 4 min.

2.6. Processing of GC–MS data and statistical analysis

All the compounds were identified based on retention time and different metabolites were differentiated after derivatization with different numbers of TMS (trimethylsilyl). Mass spectral analysis was performed through GC–MS solution software (Shimadzu®) and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) mass spectral search program (version 14 s). Normalization of peak area was done by dividing the peak area of a metabolite by the peak area of internal standard (ribitol) and this unit less values were used for statistical analyses. The fold change of compounds was calculated using the normalized peak area. The standardized data was used for partial least square-discriminate analysis (PLS-DA); VIP >1 (variable importance in projection), and p < 0.05 was considered as significant. Pathway analysis of the metabolites was compared with the KEGG library of the nearest related member- Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 for An, An-Tr, and An-PW5, Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Tr, and Bacillus subtilis for PW5 respectively. All the statistical analyses were carried out in Metaboanalyst 5.0 software (Xia and Wishart, 2011).

3. Results

3.1. Metabolite identification and variations

The intracellular metabolite profiling of cyanobacterial biofilms, An-Tr, and An-PW5 was undertaken using 3 weeks old cultures, and compared with A. torulosa as individual culture. Tr and PW5 were also analyzed for cross-analysis with biofilms. A total of 124 and 141 peaks were detected in An-Tr and An-PW5 biofilms respectively, and these peaks were identified to 84 and 92 metabolites respectively in the NIST library (Fig. 1A). Significant changes in concentrations of metabolites were recorded in all cultures, An, Tr, PW5, An-Tr, and An-PW5. The metabolites identified were categorized under five major chemical classes as: sugars and their conjugates, amino acids, peptides, and their derivatives; fatty acids and their conjugates; nucleoside, nucleotide, and analogs; inorganic acids; and other organic acids. Sugars and their conjugates were found to be higher in An-Tr biofilm (66.85%), with a 1.55- and 1.03- fold increase compared to An (26.20%), and Tr (32.99%) respectively. Similarly, fatty acids and their conjugates were higher in An-Tr (4.34%), with values which were 1.09- and 1.97- fold greater; while nucleotide, nucleoside and analogues were higher by 0.62- and 2.72- fold over An, and Tr respectively. Albeit, amino acids, peptides and their derivatives were lower in An-Tr biofilm by 3.93- and 0.30- fold compared to An, and Tr respectively. An-PW5 biofilm showed lower values in terms of sugar and their conjugates (1.49- and 0.05- fold), amino acids, peptides, and their derivatives (3.32- and 0.11- fold), over An and PW5 respectively. A fold change of 0.36 increase over An, and 3.32 decrease over PW5 was observed in fatty acids and their conjugates of An-PW5. With respect to nucleotide, nucleoside, and analogues, An-PW5 recorded highest values of 3.55% which was 0.19- and 9.88- fold higher than An and PW5 respectively. The percent distribution and the number of metabolites in each of the chemical classes have been given for each culture and the biofilms in Fig. 1B, C, Supplementary Table 1, and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A. Venn diagram illustrating the number of metabolites for cyanobacterial biofilms and their partners. Percentage of metabolite chemical classes of biofilms B. An-Tr, and C. An-PW5, as compared to An culture.

3.2. Tr and PW5 induced changes in metabolites in the cyanobacterial biofilms

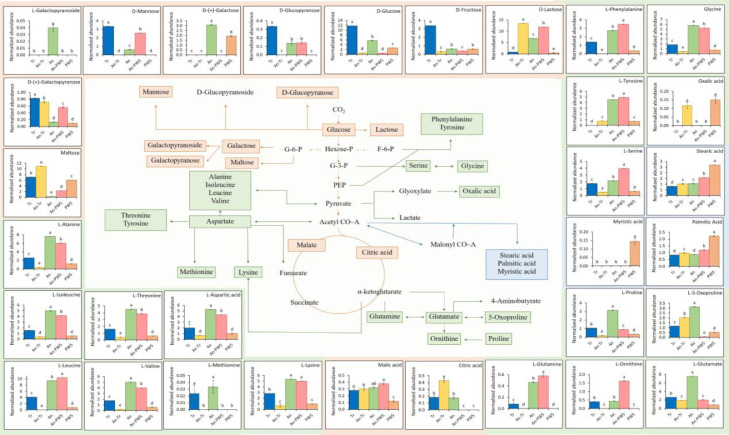

Among the 27 metabolites involved in the carbon and nitrogen cycle in cyanobacteria, changes in ten major pathways were selected and compared with individual cultures and biofilms (Fig. 2). Changes in the metabolite levels were found by comparing the cyanobacterial biofilms and their respective partners. In An-Tr biofilm, the addition of Tr increased maltose, lactose, and citric acid significantly (p ≤ 0.05), while glucose and fructose were reduced. All amino acids including alanine, isoleucine, threonine, aspartate, methionine, glutamate, glutamine, and proline were reduced significantly except 5-oxoproline, which increased significantly by Tr inoculation. Stearic and palmitic acid also increased significantly in the An-Tr biofilm. Whereas in An-PW5 biofilm, sugars (mannose and lactose), amino acids (leucine, glutamine, and ornithine) increased significantly (p ≤ 0.05), while fatty acids, stearic, palmitic, and myristic acids were lowered as a result of PW5 inoculation. Oxalic acid was distinctly present in An-Tr and PW5.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of generalised reduced carbon metabolism showing glycolysis (orange), citric acid cycle (orange), amino acid (green), and fatty acid (blue) biosynthesis in a cyanobacterium, A. torulosa. Metabolite changes in the cultures are represented by the normalized abundance (metabolite area normalised with internal standard, ribitol) ± SE with a significance level of 0.05 (p ≤ 0.05).

The metabolites having the greater variable importance in the projection value (VIP > 1) were considered as relevant for further analyses. Based on VIP > 1 and fold change (FC = 2), 114 metabolites in An-Tr and 79 in An-PW5 were found, accompanied by significant changes (p ≤ 0.05, student's T-test) after coculturing with Tr and PW5 partners respectively. Sugars, amino acids, and organic acids were identified as the most influenced metabolites and were tabulated (Table 1). Compared to An alone, 37 metabolites increased, 77 decreased, and 20 showed no change in the levels of An-Tr biofilm after co-culturing with Tr. In An-PW5, 36 increased, 43 decreased, and 43 showed no change in the levels of the metabolites after co-culturing with PW5.

Table 1.

Modulation in the metabolite profiles (in terms of sugars, amino acids, and organic acids) of the biofilms- An-Tr and An-PW5, as compared to A. torulosa (An).

| An-Tr | An-PW5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIP | log2(An-Tr/An)a | VIP | log2(An-PW5/An)b | |

| Sugars | ||||

| D-(+)-Galactopyranose | 1.10 | 2.50 | 1.09 | 2.14 |

| D-(+)-Galactose | 1.10 | −2.37 | 1.10 | −2.37 |

| D-Glucose | 1.10 | −3.14 | 1.10 | −3.38 |

| D-Mannitol | 1.10 | 5.84 | 1.10 | 3.66 |

| D-Mannose | 1.09 | −2.46 | 1.10 | 2.08 |

| D-Trehalose | 1.04 | −2.69 | 1.03 | −2.69 |

| Maltose | 1.10 | 5.03 | 1.10 | 2.81 |

| Sucrose | 1.10 | −5.58 | 1.10 | −4.31 |

| Amino acids | ||||

| Ala-beta-Ala | 1.10 | −2.39 | c | d |

| Glycine | 1.10 | −3.73 | c | d |

| Homoserine | 1.10 | −2.34 | c | d |

| L-5-Oxoproline | 1.10 | d | 1.10 | −5.35 |

| L-Alanine | 1.10 | −4.27 | c | d |

| L-Aspartic acid | 1.10 | −2.93 | c | d |

| L-Glutamic acid | 1.10 | −1.98 | c | −1.90 |

| L-Glutamine | 1.10 | −2.40 | c | d |

| L-Isoleucine | 1.10 | −3.59 | c | d |

| L-Leucine | 1.10 | −2.33 | c | d |

| L-Lysine | 1.09 | −2.98 | c | d |

| L-Ornithine | 1.10 | −2.40 | c | 1.90 |

| L-Phenylalanine | 1.10 | −2.35 | c | d |

| L-Proline | 1.10 | −4.26 | c | −1.83 |

| L-Serine | 1.10 | −2.15 | c | d |

| L-Threonine | 1.10 | −3.45 | c | d |

| L-Tryptophan | 1.10 | −2.40 | c | d |

| L-Tyrosine | 1.10 | −2.59 | c | d |

| L-Valine | 1.10 | −4.49 | c | d |

| Organic acids | ||||

| 2-Butanedioic acid | 1.04 | 2.70 | 1.08 | −1.84 |

| 2-Ketoisocaproic acid | 1.10 | −2.89 | c | 1.36 |

| 2-Pentanedioic acid | 1.10 | −2.43 | 1.10 | −2.43 |

| 3-Hydroxybutyric acid | 1.09 | −2.32 | 1.10 | 1.03 |

| 4-Aminobutanoic acid | 1.08 | −2.52 | 1.10 | 1.45 |

| 5-Aminovaleric acid | 1.08 | −1.59 | c | d |

| 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid | 1.08 | −1.83 | 1.10 | 1.37 |

| D-Gluconic acid | 1.07 | 2.59 | 1.08 | d |

| Oxalic acid | 1.10 | 2.20 | c | d |

a,b Fold changes in the metabolite concentration of An-Tr and An-PW5 against A. torulosa.(An).

c VIP (Variable Importance in the Projection) score less than 1.

d Fold change threshold value less than 2.

3.3. Partial least squares- discriminant analyses (PLS-DA) of cyanobacterial biofilms

Analyses of the data used for quantification of all cultures was performed by comparing with the internal standard ribitol and represented as relative peak areas (normalized values). The PLS-DA, heat map and cluster analyses of metabolite illustrating the differences between A. torulosa and their biofilms An-Tr and An-PW5 as shown, are based on these normalized values. In PLS-DA, the top 15 metabolite hits having a VIP score greater than 1 for both An-Tr and An-PW5 biofilms is also given (Fig. 3A, B). In An-Tr biofilm, only 3 sugars (maltose, d-mannitol, lactose) were found to be higher than An culture, whereas 1 sugar (D-glucose) and 11 amino acids such as l-leucine, l-alanine, l-glutamic acid, glycine, l-valine, l-lysine, l-isoleucine, l-aspartic acid, l- threonine, l-tyrosine and l-proline were higher in An culture alone, with 15 top hit metabolites. The metabolites hits in An-PW5 were found to be different than An-Tr biofilm, with one additional sugar- mannose, besides the common ones- d-lactose, d-mannitol, maltose, and 4 amino acids (L‑serine, l-ornithine, l-leucine, 5‑hydroxyl indoleacetic acid) being higher in An-PW5 biofilm, and 3 sugars (D-glucose, d-galactose, sucrose) and 4 amino acids (L-glutamic acid, l-5-oxoproline, l-alanine) were higher in An culture alone. The heatmap of all the cultures is given with only the metabolites exhibiting significant changes and of importance in the cyanobacterial metabolism (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Partial least square- discriminate analysis (PLS-DA) showing top 15 hits for A. An-Tr, and B. An-PW5 biofilms respectively. C Heat map and cluster analysis of all cultures, An, Tr, PW5, An-Tr, and An-PW5.

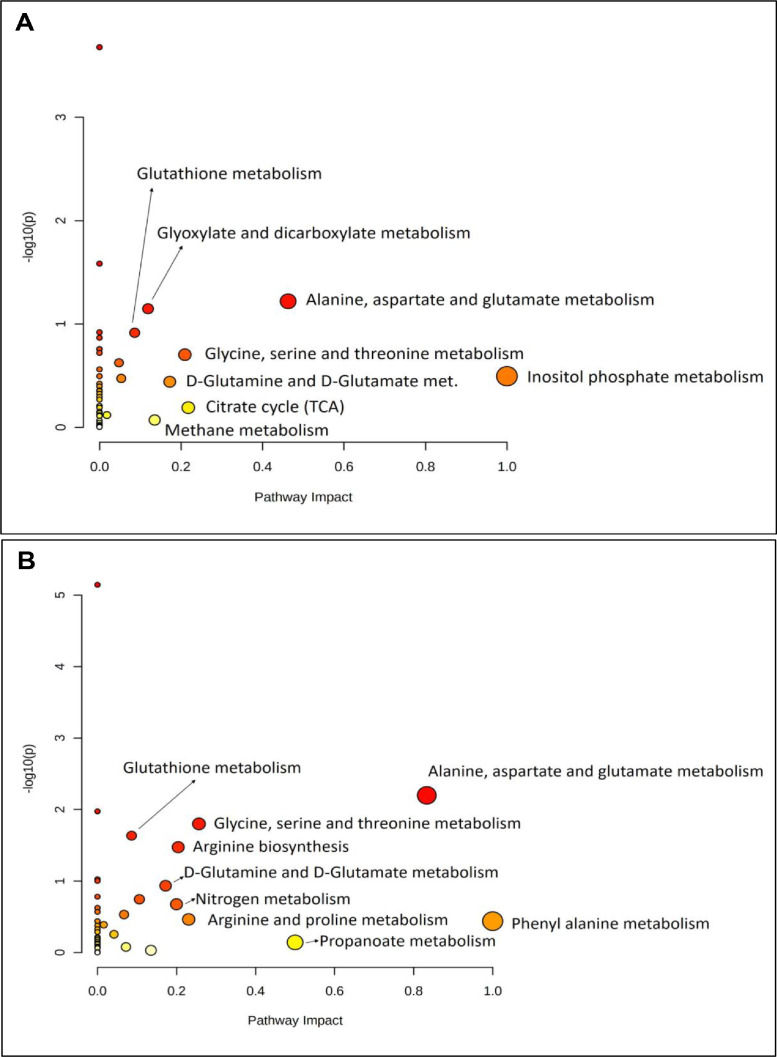

3.4. Pathway analysis

Based on the specific hypergeometric test, the pathway enrichment and metabolite topology analyses of cyanobacterial biofilms and their partners were performed and mapped into the biological pathways using the KEGG database. The database was assigned to the number of pathways for each culture, An (41), Tr (40), PW5 (41), An-Tr (39), and An-PW5 (42) respectively. Comparing An and cyanobacterial biofilms, An-Tr and An-PW5, the difference in metabolites enriched in several metabolic pathways were tabulated, and statistically significant and most enriched 15 pathways of An, An-Tr, and An-PW5 compared (Fig. 4). Among the enriched pathways, An-Tr biofilm showed reduced hits over An in all pathways including aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation, glycine, serine and threonine metabolism, arginine biosynthesis, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, and glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism. Glutathione metabolism showed a down regulation vis-à-vis both the partners-An and Tr, while nitrogen metabolism was represented minimally (as compared to An) in the biofilm. Methane metabolism was a new introduction in the An-Tr biofilm (Table 2). Albeit, An-PW5 showed an equal number of enriched pathways hits for most of the pathways over An, and also specifically enriched in 5 pathways including alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, glutathione metabolism, cyanoamino acid metabolism, glycolysis/ gluconeogenesis, and amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Pathway enrichment analyses of cyanobacterial biofilms- A. An-Tr B. An-PW5, and C. An culture alone.

Table 2.

Pathway analysis illustrating the differences in the enriched metabolites in the profiles of An, An-Tr and An-PW5.

| Pathway | An-Tr | An | An-PW5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | Hits | 10 | 14 | 14 |

| Adj. p value | 0.00021 | 7.18E-06 | 7.18E-06 | |

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | Hits | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Adj. p value | 0.02608 | 0.01059 | 0.01059 | |

| Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | Hits | 3 | 6 | 6 |

| Adj. p value | 0.19816 | 0.01585 | 0.01585 | |

| Arginine biosynthesis | Hits | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Adj. p value | 0.23732 | 0.03359 | 0.03359 | |

| Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | Hits | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Adj. p value | 0.06031 | 0.03359 | 0.00632 | |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | Hits | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Adj. p value | 0.07121 | 0.06542 | 0.17981 | |

| Glutathione metabolism | Hits | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Adj. p value | 0.12163 | 0.08585 | 0.02318 | |

| D-Glutamine and d-glutamate metabolism | Hits | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Adj. p value | 0.36241 | 0.11634 | 0.11634 | |

| Nitrogen metabolism | Hits | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Adj. p value | 0.47490 | 0.21118 | 0.21118 | |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | Hits | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Adj. p value | 0.64464 | 0.40892 | 0.76761 | |

| Cyanoamino acid metabolism | Hits | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Adj. p value | 0.37874 | 0.55508 | 0.26958 | |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | Hits | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Adj. p value | 0.70799 | 0.82384 | 0.82384 | |

| Glycolysis / Gluconeogenesis | Hits | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Adj. p value | 0.77552 | 0.87844 | 0.60615 | |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | Hits | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Adj. p value | 0.85878 | 0.93679 | 0.75033 | |

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | Hits | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Adj. p value | 0.94845 | 0.98475 | 0.98475 |

4. Discussion

Biofilms represent conglomerations or assemblages of either known or mixed species and their interactions can often result in differential regulation of metabolites, as compared to each of these species growing alone (Beveridge et al., 1997, Flemming et al., 2016). Phototrophic biofilms are considered of immense significance both in agriculture and environmental management, due to their ecological roles in nutrient sequestration, mobilization and remediation (Roeselers et al., 2008; Bharti et al., 2017). Metabolites are the ‘response factors’ that bring about phenotypic changes to counteract the genetic and environmental perturbations, either biotic or abiotic (Hu et al., 2018). In this present study, untargeted metabolite profiling using gas chromatography- mass spectroscopy showed significant metabolite changes in the An versus cyanobacterial biofilms, An-Tr and An-PW5.which was supported by heat map and cluster analysis, delineating a separate group based on the known metabolites identified. An-Tr showed highest concentrations in terms of sugars and their conjugates of 66.85%, compared to An (26.20%), and Tr (32.99%), however, the number of sugars decreased from 41 (Tr) to 31 (An-Tr). Even though, An-PW5 exhibited lower percent sugars, the numbers were almost same in all three, An (25), PW5 (22), An-PW5 (24).

Untargeted comparative metabolite profiling was preferred over targeted metabolomics to identify multiple pathways in the targeted organism (this study- A. torulosa) that are affected by inoculation and coculturing with fungal -Tr, and bacterial -PW5 partners, as against other abiotic/biotic stresses reported in earlier studies (Jin et al., 2022). Varous studies have been undertaken to understand the influence of microbial metabolites in improving plant growth. Combes-Meynet et al. (2011) showed that 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG), a secondary metabolite produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens F114 strain shows phytostimulatory effects on wheat, as supported by the upregulationof the phytostimulation genes (ppdC, flgE, nirK, and nifX-nifB) of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245-Rif on wheat rhizoplane. The metabolites released by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria, Azospirillum, Alcaligenes, Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Streptomyces, and Rhizobium also help the plant to withstand adverse environmental conditions, including salinity by improving water potential, and maintaining ionic equilibrium (Bharti et al., 2016, Liu et al., 2017).

In this study, based on the enrichment pathway analysis, it is evident that the inoculation of Tr and PW5 to the cyanobacterial biofilms altered the metabolic pathways, including those involved in amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism. These can facilitate better translocation, uptake of nutrients and help to improve plant vigor, and prove better in terms of their biofertilization and plant growth promotion potential as inoculants. It is well established that in phototrophic partner is involved in intercellular signaling, aggregation, carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism (Bharti et al., 2017), and studies on cyanobacterial metabolome have gained attention because of their biotechnological applications in discovering unknown novel compounds (Ferreira et al., 2021; Shahid et al., 2022), and dissecting metabolic fluxes in such biofilms. Development of biofilms is known to lead to several orchestrated changes in gene expression, regulation in the metabolic pathways, leading to the production of metabolites differentially in both space and time (Velmourougane et al., 2017a).

Cyanobacteria release several metabolites rich in carbon, and nitrogen which stimulate the growth of plants and modulate the C—N status of soil, as documented across several crops (Prasanna et al., 2014; Bharti et al., 2021, 2021b; Kokila et al., 2022). Their application as cyanobacterial biofilms based biofertilizers in agriculture has been evaluated in various crops such as rice, wheat, maize, flowers and vegetables towards improving soil fertility and macro- and micronutrient enrichment in produce, particularly biofortification to improve iron and zinc content in grains/produce (Abuye and Achamo, 2016; Shahane et al., 2020a; Sharma et al., 2021).

Metabolomic studies in cyanobacteria illustrating the total metabolite pool and its change, by co-culturing helps in the greater understanding of cellular metabolite functions (Kultschar et al., 2019; Kato et al., 2022). A. torulosa (An) used in this study is a promising cyanobacterium which can utilize sugars, amino acids such as ribose, citrate, phenylalanine and development of biofilms with agriculturally useful bacteria such as Azotobacter chroococcum, Mesorhizobium ciceri and Pseudomomas striata led to utilization of new saccharides (Prasanna et al., 2011).This study showed lower d-glucose, d-mannose, galactose, glucopyranose and fructose concentration in An-Tr biofilm indicating reduction in the main CO2 fixation and perhaps use of alternate pathways, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate pathway for the synthesis of ATP and NADPH2 for sustained metabolism. The glyoxylate shunt is well known for serving as an alternate route within TCA in aerobic bacteria, which bypasses the NADH producing steps, with the primary function to circumvent the carbon dioxide (CO2) production step within the TCA cycle. This helps to drive the metabolism of fatty-acids or two carbon- compounds, e.g. acetate towards the production of oxaloacetate, and thereby serve as a precursor for gluconeogenesis. This is also evidenced with significantly high production of oxalic acid, which is a product of the glyoxalate shunt, in An-Tr biofilm. Interestingly, Koedooder et al. (2018) were able to show that the regulation of glyoxylate shunt, being of ubiquitous nature, can serve as an important acclimation strategy in bacteria growing under Fe-limitation. This aspect needs more in-depth analyses to decipher their significance in our previous study on Fe biofortification in maize kernels (Nishanth et al., 2021a, Sharma et al., 2021). In addition, oxalic acid also known to play an important role in the regulation of bacterial-fungal interactions as reported by Deveau et al. (2018). Previous studies on An-Tr biofilm showed an increase in chlorophyll content (4.62 µg ml−1 culture) after 4 weeks of coculturing, and other parameters including indole acetic acid, exopolysaccharides, and glomalin related proteins, by 25%, 26%, and 62% respectively over An alone (Sharma et al., 2020). Similarly, An-PW5 also showed an improvement on growth related parameters compared to An alone (data unpublished).

T. viride (Tr) is a free-living fungus, with application as a source of enzymes, besides use in crop protection and disease management strategies globally (Harman et al., 2004). Their beneficial role in plant growth and development is attributed to their ability to elicit resistance through induction of defense responses, thereby improving crop productivity. Plant colonization is often mediated through small effector molecules, including proteins, secondary metabolites, and small RNAs, and transcriptomic profiling of biofilm formation with Azotobacter sp. illustrated significant changes in the CHO metabolism, particularly, upregulation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Velmourougane et al., 2019). In the present investigation, An-Tr recorded higher maltose, lactose, galactopyranose and citric acid, as compared to An alone; additionally changes in the carbohydrate, protein, uronic acid, acetyl levels in the EPS, as observed during biofilm formation are known to influence its biological activity (Velmourougane et al., 2017b).

Providencia sp. (PW5) is a bacterial strain with multifarious PGP traits, including catalase activity, indole utilization, phosphate solubilization, nitrogen fixation, IAA production and biocontrol-related attributes (Rana et al., 2011). It is known to exhibit citrate utilization, hydrolysis of gelatin, casein and starch, besides nitrate reduction and in the present study, stearic and myristic acid were significantly higher in PW5. The An-PW5 biofilm exhibited increased d-mannose, d-glucopyranose, lactose, d-galactopyranose, oxalic acid and malic acid which suggests that in association with An, increased carbon fixation through alternative pathways (such as the glyoxylate shunt) were utilized to generate ATP and NADPH2, as d-glucose and d-fructose were lower. The modulation in the metabolite profiles towards amino acids, as compared to PW5 revealed greater influence of An, while in terms of fatty acids such as stearic and palmitic acids along with malic acid depicts the influence of PW5; overall, a beneficial balance among the partners’ functional attributes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that deals with the modulation of metabolites in cyanobacteria by the introduction of an agriculturally beneficial bacterium or fungus as partner during biofilm formation. This study can serve as a foundation for focused metabolomics of cyanobacterial biofilm research towards their wider industrial applications (Almendinger et al., 2021) and utilization as an inoculant, across crops and ecologies (Alvarez et al., 2021).

5. Conclusion

In summary, an untargeted GC–MS workflow demonstrated the dynamic metabolite changes in laboratory developed cyanobacterial biofilms-An-Tr and An-PW5, which are potential biofertilizers and plant-growth promoting agents. Addition of Tr and PW5 to the cyanobacterial partner showed a significant reduction in sugars like d-glucose, d- fructose in both the biofilms. An-Tr biofilm decreased the concentration of most amino acids, except 5-oxoproline. Whereas An-PW5 improved in three amino acids such as serine, ornithine and leucine. Heat map and cluster analysis also showed clear-cut changes in metabolites among cyanobacterial biofilms and their individual partners. The enrichment pathway analysis demonstrated only a few significant changes in the pathway hits in An-Tr against An, illustrative of mutual distinction of functions among the partners. An-PW5 showed a change in pathways including alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, glutathione metabolism, cyanoamino acid metabolism, glycolysis/ gluconeogenesis, and amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism. Novel information regarding the metabolic machinery of biofilms vis a vis partners was generated which can help to undertake further analyses using targeted approaches and developing function-based inoculants.

Declarations

Funding

Department of Science and Technology (DST), New Delhi for providing the DST-INSPIRE Fellowship (IF180455) to SN, and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) for funds through the Network Project on Microorganisms “Application of Microorganisms in Agricultural and Allied Sectors” (AMAAS) to RP.

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

The authors report no commercial or proprietary interest in any product or concept discussed in this article.

Availability of data and material

Metabolite profiles and corresponding metadata are available from the Metabolights repository (Haug et al., 2020) under the accession number MTBLS3528 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS3528)

Code availability

None

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sekar Nishanth: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Radha Prasanna: Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Radha Prasanna reports financial support provided by Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) through the Network Project on Microorganisms “Application of Microorganisms in Agricultural and Allied Sectors” (AMAAS).

Department of Science and Technology (DST), New Delhi for providing the DST-INSPIRE Fellowship (IF180455) to the first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Division of Microbiology, ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi for the necessary facilities, and the Department of Science and Technology (DST), New Delhi for providing the DST-INSPIRE Fellowship (IF180455) to SN. The authors also acknowledge the Metabolomics Facility, NIPGR, and DBT grant (no. BT/INF/22/SP28268/2018) for funds towards the maintenance of GC/MS facility. The authors are also thankful for receiving financial support from Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) through the Network Project on Microorganisms “Application of Microorganisms in Agricultural and Allied Sectors” (AMAAS).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2022.100174.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Comparison of metabolite chemical classes of A. An-Tr, and B. An-PW5 against Tr and PW5 respectively.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Enrichment pathway impact of A.T. viride ITCC2211, and B.Providencia sp.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abuye F., Achamo B. Potential use of cyanobacterial bio-fertilizer on growth of tomato yield components and nutritional quality on grown soils contrasting pH. J. Biol. 2016;6:54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Adak A., Prasanna R., Babu S., Bidyarani N., Verma S., Pal M., Shivay Y.S., Nain L. Micronutrient enrichment mediated by plant-microbe interactions and rice cultivation practices. J. Plant Nutr. 2016;39:1216–1232. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2016.1148723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alawiye T.T., Babalola O.O. Metabolomics: current application and prospects in crop production. Biologia. 2021;76:227–239. doi: 10.2478/s11756-020-00574-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almendinger M., Saalfrank F., Rohn S., Kurth E., Pleissner D. Characterization of selected microalgae and cyanobacteria as sources of compounds with antioxidant capacity. Algal Res. 2021;53 [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez A.L., Weyers S.L., Goemann H.M., Peyton B.M., Gardner R.D. Microalgae, soil and plants: a critical review of microalgae as renewable resources for agriculture. Algal Res. 2021;54 [Google Scholar]

- Balasundaram B., Skill S.C., Llewellyn C.A. A low energy process for the recovery of bioproducts from cyanobacteria using a ball mill. Biochem. Eng. J. 2012;69:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2012.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J., Zhuo C., Zhang D., Li Y., Hu F., Li H., Su Z., Liang Y., He H. Potential applicability of a cyanobacterium as a biofertilizer and biopesticide in rice fields. Plant Soil. 2021;463:97–112. doi: 10.1007/s11104-021-04899-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baran R., Ivanova N.N., Jose N., Garcia-Pichel F., Kyrpides N.C., Gugger M., Northen T.R. Functional genomics of novel secondary metabolites from diverse cyanobacteria using untargeted metabolomics. Mar. Drugs. 2013;11:3617–3631. doi: 10.3390/md11103617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti A., Prasanna R., Kumar G., Nain L., Rana A., Ramakrishnan B., Shivay Y.S. Cyanobacterial amendment boosts plant growth and flower quality in Chrysanthemum through improved nutrient availability. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021;162 doi: 10.1007/s00374-020-01494-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti A., Velmourougane K., Prasanna R. Phototrophic biofilms: diversity, ecology and applications. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017;29:2729–2744. doi: 10.1007/s10811-017-1172-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge T.J., Makin S.A., Kadurugamuwa J.L., Li Z. Interactions between biofilms and the environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1997;20:291–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti N., Pandey S.S., Barnawal D., Patel V.K., Kalra A. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria Dietzia natronolimnaea modulates the expression of stress responsive genes providing protection of wheat from salinity stress. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34768. doi: 10.1038/srep34768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes-Meynet E., Pothier J.F., Moënne-Loccoz Y., Prigent-Combaret C. The Pseudomonas secondary metabolite 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol is a signal inducing rhizoplane expression of Azospirillum genes involved in plant-growth promotion. MPMI. 2011;24(2):271–284. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-10-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau A., Bonito G., Uehling J., Paoletti M., Becker M., Bindschedler S., et al. Bacterial-fungal interactions: ecology, mechanisms and challenges. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018;42:335–352. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuy008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Nascimento M., Battaglia M.E., Rizza L.S., Ambrosio R., Di Palma A.A., Curatti L. Prospects of using biomass of N2-fixing cyanobacteria as an organic fertilizer and soil conditioner. Algal Res. 2019;43 doi: 10.1016/j.algal.2019.101652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehling-Schulz M., Bilger W., Scherer S. UV-B-induced synthesis of photoprotective pigments and extracellular polysaccharides in the terrestrial cyanobacterium nostoc commune. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:1940–1945. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1940-1945.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira L., Morais J., Preto M., Silva R., Urbatzka R., Vasconcelos V., Reis M. Uncovering the bioactive potential of a cyanobacterial natural products library aided by untargeted metabolomics. Mar. Drugs. 2021;19:633. doi: 10.3390/md19110633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg G.E. The comparative physiology and biochemistry of the blue-green algae. Bacteriol. Rev. 1956;20(3):148–165. doi: 10.1128/br.20.3.148-165.1956. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming H.C., Wingender J., Szewzyk U., Steinberg P., Rice S.A., Kjelleberg S. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14(9):563–575. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pichel F. Solar ultraviolet and the evolutionary history of cyanobacteria. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 1998;28(3):321–347. doi: 10.1023/a:1006545303412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman G., Howell C., Viterbo A., Chet I., Lorito M. Trichoderma species — opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A., Albert A., Ganzera M. Effects of elevated ultraviolet radiation on primary metabolites in selected alpine algae and cyanobacteria. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2015;149:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug K., Cochrane K., Nainala V.C., Williams M., Chang J., Jayaseelan K.V., Donovan C.O. MetaboLights: a resource evolving in response to the needs of its scientific community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D440–D444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T., Oksanen K., Zhang W., Randell E., Furey A., Zhai G., Castelli M., Sekanina L., Zhang M., Cagnoni S. In: European Conference on Genetic Programming. García-Sánchez P., editor. Springer; Cham: 2018. Analyzing feature importance for metabolomics using genetic programming; pp. 68–83. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H., Ma H., Gan N., Wang H., Li Y., Wang L., Song L. Non-targeted metabolomic profiling of filamentous cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon flos-aquae exposed to a concentrated culture filtrate of Microcystis aeruginosa. Harmful Algae. 2022;111 doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2021.102170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan N., Prasanna R., Nain L., Kaushik B.D. Evaluating the potential of plant growth promoting cyanobacteria as inoculants for wheat. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2007;43(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2006.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y., Inabe K., Hidese R., Kondo A., Hasunuma T. Metabolomics-based engineering for biofuel and bio-based chemical production in microalgae and cyanobacteria: a review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022;344 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koedooder C., Gueneugues A., Van Geersdaële R., Vergé V., Bouget F.Y., Labreuche Y., Obernosterer I., Blain S. The role of the glyoxylate shunt in the acclimation to iron limitation in marine heterotrophic bacteria. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018;5:435. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kokila V., Prasanna R., Kumar A., Nishanth S., Shukla J., Gulia U., Nain L., Shivay Y.S., Singh A.K. Cyanobacterial inoculation in elevated CO2 environment stimulates soil C enrichment and plant growth of tomato. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022;26 doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2021.102234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kultschar, B., 2020. Metabolite Profiling of a robust cyanobacterium for industrial biotechnology (Doctoral dissertation, Swansea University). https://doi.org/10.23889/SUthesis.57241.

- Kultschar B., Dudley E., Wilson S., Llewellyn C.A. Intracellular and extracellular metabolites from the cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis fritschii, PCC 6912, during 48 hours of UV-B exposure. Metabolites. 2019;9:74. doi: 10.3390/metabo9040074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kultschar B., Dudley E., Wilson S., Llewellyn C.A. Response of key metabolites during a UV-A exposure time-series in the cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis fritschii PCC 6912. Microorganisms. 2021;9:910. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9050910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu A., Mishra S., Vadassery J. Spodoptera litura-mediated chemical defense is differentially modulated in older and younger systemic leaves of Solanum lycopersicum. Planta. 2018;248:981–997. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-2953-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Hao H., Lu X., Zhao X., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Xie Z., Wang R. Transcriptome profiling of genes involved in induced systemic salt tolerance conferred by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10795. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11308-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahawar H., Prasanna R., Gogoi R., Singh A.K. Differential modes of disease suppression elicited by silver nanoparticles alone and augmented with Calothrix elenkinii against leaf blight in tomato. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020;157:663–678. doi: 10.1007/s10658-020-02021-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama M., Nishiguchi H., Toyoshima M., Okahashi N., Matsuda F., Shimizu H. Time-resolved analysis of short-term metabolic adaptation at dark transition in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2019;128:424–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishanth S., Prasanna R., Hossain F., Muthusamy V., Shivay Y.S., Nain L. Interactions of microbial inoculants with soil and plant attributes for enhancing Fe and Zn biofortification in maize genotypes. Rhizosphere. 2021;19 doi: 10.1016/j.rhisph.2021.100421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S., Kaushik B.D. Growth promoting substances of cyanobacteria. I: Vitamins and their influence on rice plant. Proc. Indian Natl Sci. Acad. B. 1989;55:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Nishanth S., Bharti A., Gupta H., Gupta K., Gulia U., Prasanna R. In: Microbial and Natural Macromolecules. Das S., Dash H.R., editors. Academic Press; 2021. Cyanobacterial extracellular polymeric substances (EPS): biosynthesis and their potential applications; pp. 349–369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obana S., Miyamoto K., Morita S., Ohmori M., Inubushi K. Effect of Nostoc sp. on soil characteristics, plant growth and nutrient uptake. J. Appl. Phycol. 2007;19:641–646. doi: 10.1007/s10811-007-9193-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X., Bruns M.A. Development of a nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterial consortium for surface stabilization of agricultural soils. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019;31:1047–1056. doi: 10.1007/s10811-018-1597-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira I., Ortega R., Barrientos L., Moya M., Reyes G., Kramm V. Development of a biofertilizer based on filamentous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria for rice crops in Chile. J. Appl. Phycol. 2009;21:135–144. doi: 10.1007/s10811-008-9342-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira S.B., Sousa A., Santos M., Araújo M., Serôdio F., Granja P., Tamagnini P. Strategies to obtain designer polymers based on cyanobacterial extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20(22):5693. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portwich A., Garcia-Pichel F. A novel prokaryotic UVB photoreceptor in the cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis PCC 6912. Photochem. Photobiol. 2000;71:493–498. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)071<0493:anpupi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna R., Hossain F., Saxena G., Singh B., Kanchan A., Simranjit K., Ramakrishnan B., Ranjan K., Muthusamy V., Shivay Y.S. Analyses of genetic variability and genotype x cyanobacteria interactions in biofortified maize (Zea mays L.) for their responses to plant growth and physiological attributes. Eur. J. Agron. 2021;130 doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2021.126343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna R., Pattnaik S., Sugitha T.C., Nain L., Saxena A.K. Development of cyanobacterium-based biofilms and their in vitro evaluation for agriculturally useful traits. Folia Microbiol. 2011;56:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s12223-011-0013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna R., Renuka N., Nain L., Ramakrishnan B. In: Role of Microbial Communities For Sustainability. Seneviratne G., Zavahir J.S., editors. Springer; Singapore: 2021. Natural and constructed cyanobacteria-based consortia for enhancing crop growth and soil fertility; pp. 333–362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna R., Triveni S., Bidyarani N., Babu S., Yadav K., Adak A., Khetarpal S., Pal M., Shivay Y.S., Saxena A.K. Evaluating the efficacy of cyanobacterial formulations and biofilmed inoculants for leguminous crops. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2014;60:349–366. doi: 10.1080/03650340.2013.792407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A., Joshi M., Prasanna R., Shivay Y.S., Nain L. Biofortification of wheat through inoculation of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and cyanobacteria. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2012;50:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2012.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A., Saharan B., Joshi M., Prasanna R., Kumar K., Nain L. Identification of multi-trait PGPR isolates and evaluating their potential as inoculants for wheat. Ann. Microbiol. 2011;63:893–900. doi: 10.1007/s13213-011-0211-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi R.P., Sinha R.P. Biotechnological and industrial significance of cyanobacterial secondary metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009;27(4):521–539. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeselers G., Loosdrecht M.C., Muyzer G. Phototrophic biofilms and their potential applications. J. Appl. Phycol. 2008;20:227–235. doi: 10.1007/s10811-007-9223-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi F., De Philippis R. In: The Physiology of Microalgae. Borowitzka MA, Beardall J, Raven JA, editors. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2016. Exocellular polysaccharides in microalgae and cyanobacteria: chemical features, role and enzymes and genes involved in their biosynthesis; pp. 565–590. [Google Scholar]

- Schrimpe-Rutledge A.C., Codreanu S.G., Sherrod S.D., McLean J.A. Untargeted metabolomics strategies—challenges and emerging directions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2016;27:1897–1905. doi: 10.1007/s13361-016-1469-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz D., Orf I., Kopka J., Hagemann M. Recent applications of metabolomics toward cyanobacteria. Metabolites. 2013;3:72–100. doi: 10.3390/metabo3010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahane A.A., Shivay Y.S., Prasanna R. Enhancing phosphorus and iron nutrition of wheat through crop establishment techniques and microbial inoculations in conjunction with fertilization. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020;66:763–771. doi: 10.1080/00380768.2020.1799692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahane A.A., Shivay Y.S., Prasanna R., Kumar D. Nutrient removal by rice–wheat cropping system as influenced by crop establishment techniques and fertilization options in conjunction with microbial inoculation. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:21944. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78729-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid A., Siddiqui A.J., Musharraf S.G., Liu C.G., Malik S., Syafiuddin A., Boopathy R., Tarbiah N.I., Gull M., Mehmood M.A. Untargeted metabolomics of the alkaliphilic cyanobacterium Plectonema terebrans elucidated novel stress-responsive metabolic modulations. J. Proteom. 2022;252 doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Prasanna R., Hossain F., Muthusamy V., Nain L., Das S., Shivay Y.S., Kumar A. Priming maize seeds with cyanobacteria enhances seed vigour and plant growth in elite maize inbreds. 3 Biotech. 2020;10:154. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-2141-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Prasanna R., Hossain F., Muthusamy V., Nain L., Shivay Y.S., Kumar S. Cyanobacterial inoculation as resource conserving options for improving the soil nutrient availability and growth of maize genotypes. Arch. Microbiol. 2021;203:2393–2409. doi: 10.1007/s00203-021-02223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivay Y.S., Prasanna R., Mandi S., Kanchan A., Simranjit K., Nayak S., Baral K., Sirohi M.P., Nain L. Cyanobacterial inoculation enhances nutrient use efficiency and grain quality of Basmati rice in the system of rice intensification (SRI) ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022;2(4):742–753. doi: 10.1021/acsagscitech.2c00030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.N. Indian Council of Agricultural Research; New Delhi: 1961. Role of blue-green algae in nitrogen economy of Indian agriculture; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.P., Klisch M., Sinha R.P., Hader D.P. Effects of abiotic stressors on synthesis of the mycosporine-like amino acid shinorine in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis PCC 7937. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008;84:1500–1505. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneha G.R., Yadav R.K., Chatrath A., Gerard M., Tripathi K., Govindsamy V., Abraham G. Perspectives on the potential application of cyanobacteria in the alleviation of drought and salinity stress in crop plants. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021;33:3361–3778. doi: 10.1007/s10811-021-02570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanier R.Y., Kunnisawa R., Mandel M., Cohen-Bazire G. Purification and properties of unicellular blue green algae (Order: Chroococcales) Bacteriol. Rev. 1971;35:171–305. doi: 10.1128/br.35.2.171-205.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomitani A., Knoll A.H., Cavanaugh C.M., Ohno T. The evolutionary diversification of cyanobacteria: molecular-phylogenetic and paleontological perspectives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:5442–5447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600999103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velmourougane K., Prasanna R., Saxena A.K., Singh S.B., Chawla G., Kaushik R., Ramakrishnan B., Nain L. Modulation of growth media influences aggregation and biofilm formation between Azotobacter chroococcum and Trichoderma viride. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2017;53:546–556. doi: 10.1134/S0003683817050179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velmourougane K., Prasanna R., Singh S.B., Kumar R., Saha S. Sequence of inoculation influences the nature of exopolymeric substances and biofilm formation in Azotobacter chroococcum and Trichoderma viride. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017;93:fix066. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velmourougane K., Prasanna R., Supriya P., Ramakrishnan B., Thapa S., Chawla G., Kumar A., Saxena A.K. Transcriptome profiling provides insights into regulatory factors involved in Trichoderma viride-Azotobacter chroococcum biofilm formation. Microbiol. Res. 2019;204:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman G.S. Algal biofertilizers and rice cultivation. Today & Tomorrow’s Printers & Publishers; New Delhi: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Werner A., Broeckling C.D., Prasad A., Peebles C.A. A comprehensive time-course metabolite profiling of the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 under diurnal light: dark cycles. Plant J. 2019;99:379–388. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand C., Pflugmacher S. Ecotoxicological effects of selected cyanobacterial secondary metabolites: a short review. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005;203:201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J., Wishart D.S. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:743e760. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Comparison of metabolite chemical classes of A. An-Tr, and B. An-PW5 against Tr and PW5 respectively.

Supplementary Fig. 2. Enrichment pathway impact of A.T. viride ITCC2211, and B.Providencia sp.

Data Availability Statement

Metabolite profiles and corresponding metadata are available from the Metabolights repository (Haug et al., 2020) under the accession number MTBLS3528 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS3528)

Data will be made available on request.