Highlights

-

•

The mechanism of ternary interaction in potato starch-based food system was studied.

-

•

The ternary interaction system was an emulsion-filled gel.

-

•

The protein exhibited a thinning effect on starch gel.

-

•

Oil droplets stabilized by protein and amylose-lipid complex dispersed in the gel.

-

•

Chemical bonds in the system were hydrogen, hydrophobic, and electrostatic bonds.

Abbreviations: ALC, amylose-lipid complex; APTS, 8-amino-1,3,6-pyrenetrisulfonic acid; CA, casein; CA-SBO, casein-soybean oil; K, consistency coefficient; G′, elastic modulus; n, flow behavior index; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I; FTIR, Fourier transform infrared; FWHM, full width at half-maximum; GPS, gelatinized potato starch; GPS-CA, gelatinized potato starch-casein; GPS-CA-SBO, gelatinized potato starch-casein-soybean oil; GPS-SBO, gelatinized potato starch – soybean oil; GPS-WP, gelatinized potato starch – whey protein; GPS-WP-SBO, gelatinized potato starch – whey protein – soybean oil; PSBF, potato starch-based foods; LVR, linear viscoelastic region; tan δ, MP, loss tangent; KBr, potassium bromide; PS, potato starch; RC, relative crystallinity; SBO, soybean oil; G′′, viscous modulus; WP, whey protein; WP-SBO, whey protein-soybean oil; τ0, yield stress

Keywords: Gelatinization, Ternary interaction, Chemical bonding, Rheology, Emulsion-filled gel

Abstract

Physico-chemical properties of potato starch-based foods (PSBF) interacted with milk protein (MP), and soybean oil (SBO) were investigated. Microstructures, rheological properties, and chemical bonding among those ingredients were determined. An emulsion-filled gel, in which oil droplets stabilized by MP and/or amylose-lipid complex (ALC) dispersed in a starch gel structure of PSBF was revealed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Starch-starch, protein-oil, and protein-protein played the dominant interactions while ALC and starch-protein interaction were subordinates. Rheological data showed that MP induced a thinning effect on starch gel, while SBO seemed to reinforce the solid-like properties of the gel. The chemical interactions analyzed by FTIR, Raman, and X-ray diffraction suggested that these foods were lack in non-covalent crosslinks and were dominated by diverse physical interactions. However, the different preparation of such foods could induce chemical binding in a different way and MP and SBO could affect the properties of PSBF in this study.

1. Introduction

Starch, protein, and lipids are the main components of staple foods. During food processing, these components interact with each other extensively even forming diverse complexes, which ultimately affect the nutritional quality, textural perception, flavor sensation, as well as the safety of the involved food products. The previous studies have confirmed that the interactions of starch-lipid, lipid-protein, and starch-protein are always involved in such systems (McPherson & Gaonkar, 2006). As widely evidenced, the interaction of starch and lipid naturally existed in starch granules or occurred in many foods comprising them. This was confirmed in different starch-lipid couples (Huang, Chen, Wang, & Zhu, 2020). The consequences attested that the lipid complexing considerably altered the physicochemical properties and nutritional nature of starch, such as reducing swelling power and solubility, improving gelatinization stability, delaying retrogradation, and inhibiting digestibility (Wang, Chao, Cai, Niu, Copeland, & Wang, 2020). As known to all, lipid is preferential to complex with amylose over amylopectin, owing to the high ability of the helix structures in amylose molecules to accommodate lipid guests (Huang, Chen, Wang, & Zhu, 2020). Regarding starch-protein interaction, Sjoo and Nilsson (2017) reported that it can be categorized into three models including compatibility, thermodynamic incompatibility, and complex coacervation (or complexation) (Sjoo & Nilsson, 2017). Such interactions could be found in colloidal and emulsion food products such as ice cream mix and rice pudding which composed of polysaccharide, milk protein, and oil (Pracham and Thaiudom, 2016, Thaiudom and Pracham, 2018, Thaiwong and Thaiudom, 2021). For lipid-protein interactions, it is often observed in protein-stabilized emulsions, where extensive interactions of lipid-protein occurred at the O/W interface. Obviously, these interactions are of extreme importance in forming and maintaining well-defined structure and stability of certain foods (Dapueto, Troncoso, Mella, & Zúñiga, 2019).

With the great progresses in those binary interactions, the research on this point recently forwards to ternary interactions, which is much closer to the situation in virtual foods. On this point, the teams led by Dr. Bruce R Hamaker from Purdue University and Dr. Shujun Wang from Tianjin University of Science & Technology contributed greatly. By mainly using sorghum/maize starch, whey protein isolate, and free fatty acids as model components, the former team provided evidenced for the presence of starch-protein-lipid ternary complex, explored the arrangements and roles of each component, and tested the significance of this complexation on the functionality of the starch and the system, such as pasting behavior, rheological properties, and iodine binding capacity (Zhang and Hamaker, 2003, Zhang et al., 2010). For the latter team, most of their work concentrated on the ternary systems consisting of maize starch, β-lactoglobulin, and free fatty acids or monoacylglycerides, contributing a lot to the dose-effect and structure-effect of lipid component on the structural order and functionality of starch-protein-oil systems (Chao et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2017). In addition, other starch-protein-oil systems including corn starch-corn oil-soy protein (Chen, He, Zhang, Fu, Jane, & Huang, 2017) and maize starch-maize oil-zein protein (Chen, He, Zhang, Fu, Li, & Huang, 2018) were explored. However, the potato starch (PS) used in these studies was in ungelatinized form and was mixed with milk protein (MP) and oil before being heated.

In the food industry, the ternary interactions of PS, plant oil, and MP and the products consist of PS with MP and plant oils have been less investigated and still needed to explore. Mashed potato, potato puree, and potato cream for being the filling in bakery products are several typical virtual food consisting of fresh cooked potatoes with milk and butter or plant oils (Álvarez et al., 2013, Dankar et al., 2018, Dankar et al., 2019). Based on the abovementioned knowledge, it was hypothesized that the ternary interactions of PS, MP, and plant oil would affect the microstructure, rheological properties, and chemical bonding of such potato starch-based foods (PSBF). Thus, in this study, gelatinized potato starch (GPS), MP (casein, CA or whey protein, WP), and soybean oil (SBO) were used to create a model of binary and ternary interaction systems mimicking PSBF product containing PS. In order to understand the development of microstructure, rheological properties, and chemical bonds of these systems, this study was investigated with the aid of a confocal microscope, rheometer, FTIR, Raman spectrometer, and X-ray diffraction, respectively.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

PS was purchased from Bangkok Inter Food Co., Ltd. (Bangkok, Thailand). CA was received from Vicchi Enterprise Co., Ltd. (Bangkok, Thailand). WP was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). SBO was from a local market (Bangkok, Thailand). 8-amino-1,3,6-pyrenetrisulfonic acid (APTS), Fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I (FITC), and Nile Red were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade. The crude fat, total protein, ash, and moisture of applied starch, protein and oil were determined by using AOAC methods (AOAC 2000) and the proximate composition results were shown in Supplementary Material 1.

2.2. Sample preparation

The binary and ternary complexes were prepared according to the method reported by Chen et al., 2017, Chen et al., 2018 with modifications. The diagram of sample preparation was illustrated in Fig. 1. In brief, PS slurry (6.0 g in 40 g deionized water) was completely gelatinized in a 95 °C water bath for 30 min and MP was dispersed in hot deionized water (95 °C) in advance. As designed, the four primary systems, five binary systems, and two ternary systems were prepared by using hot starch paste, hot WP solution and SBO solely or in intended combinations. Then, the hot mixtures at 60 °C were homogenized at 10,000 rpm for 3 min with the aid of a T25 homogenizer (IKA, Staufen, German). In all systems, PS, WP and SBO presented at the constant concentrations of 10.0 g/100 g wb, 1.0 g/100 g wb and 1.5 g/100 g wb, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of samples preparation.

In the subsequent analysis, freeze-dried samples were obtained by first freezing the corresponding fresh samples at −80 °C in a freezer (Haier, Qingdao, China) and then drying them in a vacuum freeze dryer (Seientz-10ND, Ningbo Xinzhi Biotechnology Co., ltd, Ningbo, China) at −20 °C, 4.2 Pa. Prior to the measurements, the freeze-dried samples were ground to pass through a 60-mesh sieve. The resulting powder was hermetically packaged in a plastic bag and stored at room temperature until further study.

2.3. Characterization of the microstructure of starch-protein-oil systems

The microstructures of resultant systems were revealed by using a Nikon A1R confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), following the method by Thaiudom and Pracham (2018). The microscopy was equipped with 405 nm, 488 nm, and 561 nm lasers. The starch, protein, and oil components in the systems were stained with an aqueous solution of APTS, an acetone solution of FITC, and an ethyl alcohol solution of Nile red (0.1 % w/w), respectively. After being stained, the starch, protein, and lipid components were colored in blue, green, and red color, respectively. Fluorescence was excited at 405 nm for the blue channel (425–475 nm), at 488 nm for the green channel (500–550 nm), and at 561 nm for the red channel (570–620 nm). In a specific observation, an aliquot of sample (approximately 0.2 mL, at room temperature) was placed in a tube, then a drop of APTS solution (approximately 10 μL) was added and the tube was fiercely vortexed to achieve a homogeneous mixture. Then, the mixture was kept at room temperature for 10 min. After that, the mixture was further successively stained with FITC and Nile red by repeating the operations of APTS. After that, the stained sample was loaded between two slides and observed at a magnification of 40×. For each sample, at least six images were taken.

2.4. Rheological measurement

The rheological properties of abovementioned systems were also checked by using rheometer (An MCR302 rotary rheometer, Anton-Paar, Graz, Austria) equipped with a cone-plate probe (cone angle of 1° and a plate radius of 60 mm). The sample was maintained at 37 °C and a 2-min balance was applied upon the loading of the samples (Gao, Ye, Wang, Lu, Yuan, & Zhao, 2019). In steady shear measurements, the rate was gradually increased from 0.01 s−1 to 100 s−1. The data of shear stress (τ) and shear rate () were fitted to the Herschel-Bulkley model (Equation (1)) to characterize the rheological behavior in terms of yield stress (τ0, Pa), consistency coefficient (K, Pa sn), and flow behavior index (n, dimensionless).

| (1) |

where, τ was the shear stress (Pa) and was the shear rate (s−1).

In dynamic oscillatory shear measurements, the frequency varied from 0.01 Hz to 10 Hz. An amplitude strain of 0.1 % was applied, within the linear viscoelastic region (LVR). To determine the LVR, a strain sweep was performed at a constant frequency of 0.5 Hz over the strain range of 0.01 % to 100 %. For dynamic oscillatory shear measurements, the elastic modulus (G′) and viscous modulus (G′′) over a frequency range of 0.01–10 Hz were recorded. The corresponding loss tangent (tanδ = G′′/G′) was calculated accordingly. The tracks of both moduli were fitted to the Power law models (Equations (2), (3)).

| (2) |

| (3) |

where, k′ and k″ were consistency coefficients (Pa sn), n′ and n″ were behavior indices (Gao, Ye, Wang, Lu, Yuan, & Zhao, 2019).

2.5. Chemical bonding of the interactions involved in PS-MP-SBO systems

The interactions of GPS, MP, and SBO in the present systems were revealed with the aid of FT-IR, Raman spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction. To perform FT-IR, freeze-dried samples were applied, and a potassium bromide (KBr) tablet method was performed. The spectrum of the freeze-dried samples was recorded by a Spectrum 100 FT-IR spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, MA) at a room temperature with a resolution of 4 cm−1 over a wavelength range of 400–4000 cm−1. The spectrum of pure SBO was recorded by an FT-IR spectrometer (Bruker Tensor 27, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with an ATR platinum accessory at the same experimental condition. To resolve the peaks located in the fingerprint region (approximately from 900 cm−1 to 1200 cm−1), the obtained spectrum was subjected to a baseline correction and then deconvoluted with the aid of PeakFit software (version 4.12, Chicago, IL, USA).

The measurements of Raman spectroscopy were also conducted with freeze-dried samples, using a DXR2 Raman spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) at 15 mW laser power. With the aid of 20× magnification microscope, the excitation laser beam (785 nm excitation line of Ar-laser in Spectra-Physics) was focused on a sample loaded on a glass slide. An exposure time of 5 s and a slit width of 50 μm were applied. The spectrum, averaged from 40 scans, was acquired over the wavelength range of 200 cm−1 to 3100 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1. The baseline correction, smoothing, and standardization of the obtained spectra were atomically handled with the assistance of Omnic software (version 9, Thermo Nicolet, MA, USA).

To perform X-ray diffraction, the freeze-dried samples were equilibrated over a saturated NaCl solution for one week prior to the measurements. An X-ray 700 diffractometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) with copper tubes (λ = 1.5418 Å) was operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. The sample powders were tightly packed in a glass cell and were scanned over a 2θ range of 4° to 40° at a rate of 2°/min and a step time of 0.95 s. The relative crystallinity of starch component was calculated by using Jade 6.5 software (Materials Data, CA, USA).

2.6. Statistical analysis

For each sample, the measurements of rheology, FTIR, and Raman spectrum were carried out in triplicate and the X-ray experiment was conducted in duplicate. Rheological parameters, FT-IR, Raman, and XRD data were analyzed for mean difference test expressing as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was conducted using a software of SPSS 23.0 (IBM Crop. Amonk, NY, USA). In all statistical analysis, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results and discussion

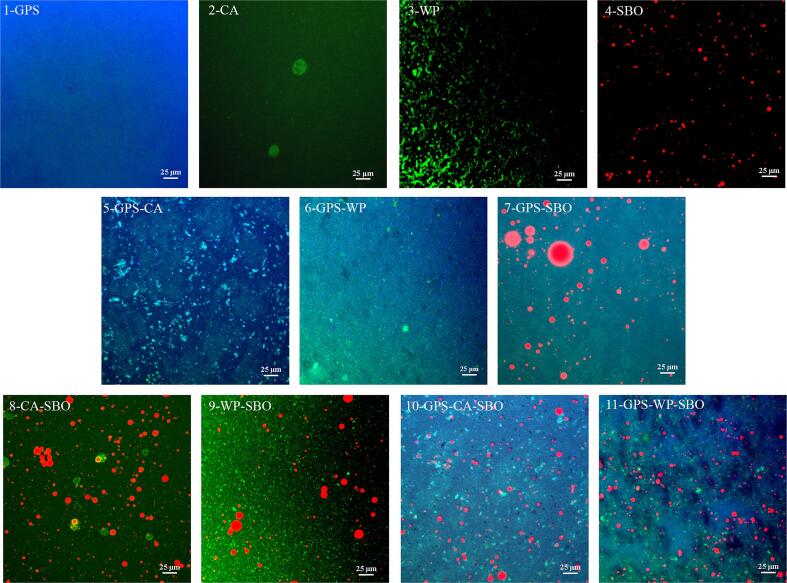

3.1. Microstructures of GPS-MP-SBO systems

The microstructures of various systems observed by CLSM are illustrated in Fig. 2. In primary systems, GPS, as expected, was uniformly stained by APTS, giving a blue color. No granule residues were visibly found in GPS, indicating the complete gelatinization of PS. This was certainly contributed to the fact that starch slurry experienced an intensive heating regime (at 95 °C for 30 min) together with furious homogenization, which completely destroyed PS granules and formed a continuous matrix. As for pure CA and WP systems, they were stained with FITC giving a brighter green color. Obviously, CA existed in larger particles than WP in their pure systems. This aligned well with the previous results that indicated that WP is much more water soluble than CA and CA is always present in micelles in an aqueous matrix in neutral conditions (Horne, 2017). As observed in other studies, SBO was stained by Nile Red, giving a red color. It must be noted that even though GPS contained some proteins and lipids (Supplementary Material 1), no significant green or red color was visible in a pure GPS system, which can be ascribed to the extreme low levels of these components (0.13 g/100 g and 0.22 g/100 g). In this scenario, the extensive blue color shaded the other colors and made them imperceptible.

Fig. 2.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images of the fresh samples. Sample code: 1-GPS (Gelatinized potato starch), Potato starch paste; 2-CA, Casein solution; 3-WP, Whey protein solution; 4-SBO, Soybean oil; 5-GPS-CA, Gelatinized potato starch – Casein; 6-GPS-WP, Gelatinized potato starch – Whey protein, 7-GPS-SBO, Gelatinized potato starch – Soybean oil; 8 – CA-SBO, Casein – Soybean oil; 9 – WP-SBO, Whey protein – Soybean oil; 10 – GPS-CA-SBO, Gelatinized potato starch – Casein – Soybean oil; 11 – GPS-WP-SBO, Gelatinized potato starch – Whey protein – Soybean oil.

In binary systems, the results were rather different from those observed in primary ones. In gelatinized potato starch-casein (GPS-CA) and gelatinized potato starch-whey protein (GPS-WP) systems, protein components in small particles were scattered in continuous 3D-networks formed by GPS (Fig. 2 GPS-CA and GPS-WP). This was similar to the situations which were evidenced in MP/rice starch gels with the aggregated protein particles sandwiched in a 3D starch network (Noisuwan, Hemar, Wilkinson, & Bronlund, 2009). It is widely acknowledged that polysaccharides such as PS and MP are thermodynamically incompatible, therefore, they may cause phase separation in a mixture (Thaiwong and Thaiudom, 2021, Kumar et al., 2022). The phase separation of MP particulates from a starch matrix was explained by a depletion-flocculation mechanism (Noisuwan, Hemar, Wilkinson, & Bronlund, 2009). In contrast, WP distributed more evenly than CA in PS pastes, which may be attributed to its higher water solubility, less aggregating tendency, and a stronger affinity to starch than CA. In a view of the phosphate ester groups in GPS, the starch component in the present system was negatively charged from the MP components. However, in contrast to WP, CA was charged more intensively and constituted higher repulsive forces to negatively charged GPS, which finally resulted in a less immense distribution in a starch gel matrix. As reported by Yang, Zhong, Goff, and Li (2019), the intermolecular hydrogen bonding between starch and protein increased with the hydrophilicity of protein. Interestingly, unlike the global shape in its pure system, the CA in a GPS-CA system was in an irregular shape, and it tended to stay at the domains with a higher starch concentration (indicated by a darker blue color). This may be caused by the impedance of the starch network from the rebuild of the CA micelles previously broken by homogenization. Certainly, this was ultimately a consequence of the starch-protein interaction, in which hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and van der Waals forces may be involved (Wang et al., 2021).

For the binary system of gelatinized potato starch – soybean oil (GPS-SBO), the oil component was distributed in a 3D starch network as well-defined spherical droplets (Fig. 2 GPS-SBO). Unexpectedly, this binary system was rather stable and did not undergo phase separation, even after prolonged standing, despite the fact that starch has an inactive surface and no exogenous surfactants were used in this study. Similar results had been reported for the aqueous binary system of SBO and unmodified food grade corn starch prepared by steam jet cooking. The excellent stabilization of SBO droplets was interpreted as a result of the formation of a thin starch film at O/W interface, which formed spontaneously during the preparation of the system and was not removed by water washing (Fanta, Felker, Eskins, & Baker, 1999). A further investigation on the binary system made of starch and paraffin wax revealed that the film at the O/W interface was not solely composed of starch, instead it consisted of a mixture of starch (mainly amylose), its intrinsic proteins, and the complexes of amylose to native lipids existing in starch (Fanta, Felker, Shogren, & Knutson, 2001). According to this, the formation of helical inclusion ALCes occurred in present systems containing starch and oil components. This was accordingly verified by the pink color (in contrast to the red color in the pure SBO system) of oil droplets, especially their boundaries, in the GPS-SBO system (Fig. 2 GPS-SBO). As conceived, the formation of a thin starch film at the O/W interface underwent three steps: first, amylose interacted with lipids resulting in amphiphilic inclusion complexes; second, the complexes spontaneously adsorbed onto O/W interfaces and oriented their hydrophobic moieties which penetrated into the oil phase and the hydrophilic parts located at the surface of the oil droplets; finally, the hydrophilic parts aligned together and even recrystallized to form a starch gel film, especially when the system was cooled. In these processes, interactions such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces were involved.

As for the binary systems of casein-soybean oil (CA-SBO) and whey protein-soybean oil (WP-SBO), clearly, the SBO component in round droplets dispersed in the MP matrix, where both MP particles and solubilized MP molecules existed. In these systems, the average size and span of oil droplets were much less than that in the GPS-SBO system. This should be attributed to the higher capacities of MP than PS or ALCes in stabilizing SBO droplets. Essentially, the amphiphilic nature of MP and its native binding tendencies towards SBO droplets were a response to this stabilizing effect (De Kruif, Huppertz, Urban, & Petukhov, 2012). Ultimately, this was often designated as the emulsifying capacity of food proteins, which often made emulsions rather perfect in terms of thermodynamic stability. In Fig. 2, in either CA-SBO or WP-SBO system, it was observed that SBO droplets were decorated with an orange to yellow corona and even small SBO droplets completely turned into orange rather than red as it did in pure SBO system. This was interpreted as a consequence of the events that CA or WP adsorbed at O/W interface. In comparison, the color changes of SBO droplets in the CA-SBO system, especially these smaller ones, were more extensive and greater than that in the WP-SBO system. In addition, SBO droplets in CA-SBO presented a somewhat smaller average size and a narrower span than those in WP-SBO. All of these were in agreement with the established common knowledge that CA demonstrates a stronger emulsifying capacity than WP (Braun, Hanewald, & Vilgis, 2019). Apparently, as did in the pure CA system, CA micelles were observed in the CA-SBO system. This again affirmed that the presence of GPS promoted the disintegration of CA micelles or restrained the rebuilt of CA micelles as they were broken by homogenization. Basically, the adsorption of CA or WP onto O/W interface was mainly driven by the hydrophobic interactions between the lipophilic moieties of proteins and lipid molecules.

For the ternary systems, the image of any system could be largely regarded as an integration of abovementioned two relevant binary systems, i.e., gelatinized potato starch-casein-soybean oil (GPS-CA-SBO) from GPS-SBO and CA-SBO and gelatinized potato starch-whey protein-soybean oil (GPS-WP-SBO) from GPS-SBO and WP-SBO (Fig. 2). In these two ternary systems, irregular protein particles and protein-decorated oil droplets dispersed in a 3D starch network, and no CA micelles existed in GPS-CA-SBO as did in GPS-CA. In contrast to the binary systems of GPS-SBO, CA-SBO, and WP-SBO, both ternary systems, GPS-CA-SBO and GPS-WP-SBO, presented a smaller average size and a narrower span of oil droplets together with more evenly distributed proteins. These not only again supported that GPS could prevent the rebuild of CA micelles as they were broken by homogenization but also asserted that: 1) GPS can improve the stability of homogenization-induced oil droplets and restrain the coalescence of protein-stabilized oil droplets; 2) the presence of oil and protein in starch matrix can benefit their distribution within each other. As observed, the emulsified oil droplets in GPS-WP-SBO were more likely to undergo flocculation than those in GPS-CA-SBO. This was mainly ascribed to the difference in the isoelectric points of CA (∼4.6) and WP (∼5.0) and hence there was the higher net negative charge of CA than WP in a neutral environment (Liu, Jæger, Nielsen, Ray, & Ipsen, 2017). Thus, a reduction in the flocculation of oil droplets in GPS-CA-SBO resulted from a higher repulsion amongst the droplets.

Based on microstructure analysis, it was proposed that an ordered structure was established in present ternary systems, which was fundamentally driven and maintained by the interactions between three components. In this sense, the present ternary systems can be looked at as filled composite gels in which emulsion droplets and aggregated protein particles acted as fillers, while the continuous phase was a 3D hybrid network made of GPS and well dispersed MP. Apparently, the roles of the three components were different and they contributed to the structure and texture of ternary systems in different ways. Specifically, the MP component mainly acted as the emulsifier while the GPS component, the most prominent component, constructed a 3D network, owing to its higher concentration and viscous nature. In this scenario, on one hand, starch facilitated the dispersion of protein especially restraining the rebuilt CA micelles, which finally improved the emulsifying performance of the MP component. On the other hand, GPS inhibited the coalescence of emulsified SBO droplets mainly by physical entrapment. In addition, a minor portion of GPS was likely to anchor at the O/W interface via amylose-lipid interactions, which certainly benefited the stabilization of SBO droplets in the GPS matrix. As speculated, diverse intermolecular interactions were present in the ternary systems, such as hydrophobic interactions (protein-lipid, protein-protein), hydrogen bonding (starch-protein, starch-starch, protein-protein), electrostatic repulsion (protein-protein), and the Van der Waals force (starch-lipid) (Wang, Chao, Cai, Niu, Copeland, & Wang, 2020). Among these, the interactions of the starch-starch (hydrogen bonding into 3D network) and protein-lipid (hydrophobic interactions at O/W interface), as well as protein-protein (self-assembly into particles) were the dominant interactions and the amylose-lipid (complex formation), and starch-protein (molecule-particle or molecule-molecule interactions) interactions were the subordinates. Theoretically, food proteins contain many hydrophilic groups such as amide, hydroxyl, carboxyl and thiol in the alkyl side chains, which are capable of forming links with starch molecules. Actually, weak starch-protein interactions were present in the systems, which were aligned with the results from the study of oat starch-caseinate interaction system (Kumar, Brennan, Brennan, & Zheng, 2022).

3.2. Rheological properties

3.2.1. Flow behavior from steady shear measurements

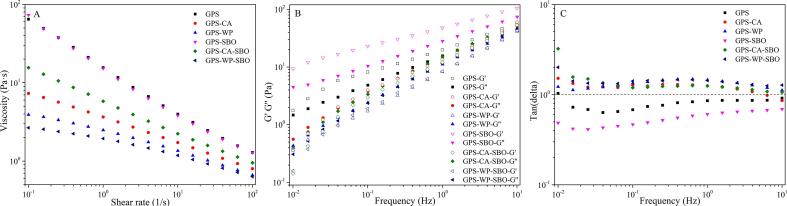

In steady shear measurements, the primary systems of CA and WP as well as the binary systems of CA-SBO and WP-SBO presented very low values in viscosity (∼1.0 mPa s) (Supplementary Material 2). This aligned well with the lower concentration of the MP in the systems and in these cases, no 3D network was constructed, and only thin protein suspensions and emulsions formed. For a pure SBO system, it was characterized as a Newtonian fluid as determined elsewhere, whose viscosity was independent of the shear rate. In view of these facts, the rheological results are mainly discussed with other binary and ternary systems and their flow curves are shown in Fig. 3. In addition, the rheological properties of these systems were quantified by fitting them to the Power law model and the results are summarized in Table 1. The high values in R2 (0.9949–1.0000) showed a good fit with the Power law model to experimental data. Newtonian fluids have a flow behavior index (n) of 1.0, while pseudoplastic fluids present n values lower than 1.0 and the degree of pseudoplastic behavior is negatively related to the n value. For these systems, without any exception, their viscosities gradually decreased as increase in shear rate and their n values were significantly below 1.0 (Table 1), interpreting their pseudoplastic nature and shear-thinning behaviors (Li et al., 2019, Wang et al., 2018). This substantiated the presence of a 3D network in these systems as discussed above, which underwent a breakdown at a certain level of applied stress. Together with the extreme low viscosities observed for CA, WP, CA-SBO, and WP-SBO systems, it was proposed that there was no 3D network in these systems resulted from the GPS component. However, starch pastes always exhibit pseudoplastic nature and shear-thinning behavior (Li et al., 2019, Wang et al., 2018). For the present study, the shear-thinning nature may be explained by the shear-induced breakdown of the 3D GPS network and the subsequent alignment of broken gel pieces and oil droplets in the shear direction. The systems having virtual values in τ0, especially those of GPS and GPS-SBO, demonstrated higher resistance to flow than those with zero or minimal τ0 values when a low shear stress was applied. However, with a sufficiently high shear stress, the 3D structures of these systems were disrupted, resulting in significant decreases in viscosity.

Fig. 3.

(A)Flow curves of the pastes (37 °C) from GPS, GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-SBO, GPS-CA-SBO and GPS-WP-SBO. Frequency sweeps (B, C) of the pastes (37 °C) from GPS, GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-SBO, GPS-CA-SBO and GPS-WP-SBO. Frequency-dependence of storage modulus (G′, open symbols) and loss modulus (G′′, closed symbols) were recorded at 0.1 % strain and then the loss tangent (tan δ) was derived.

Table 1.

Parameters of the Herschel-Bulkley functions describing dependence on shear stress and shear rate of the pastes and data of dynamic oscillatory shear measurements fitting to G′ = k′ωn′, G″ = k”ωn”, respectively.

| Paste samples | (Pa) | K (Pa sn) | n | R2 | k' | n' | R2 | k'' | n'' | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPS | 5.66 ± 1.57a | 9.43 ± 1.47a | 0.55 ± 0.03e | 0.9995 | 20.15 ± 11.32b | 0.47 ± 0.10ab | 0.9854 | 15.25 ± 3.92b | 0.48 ± 0.03b | 0.9995 |

| GPS-CA | 0.04 ± 0.07b | 3.46 ± 0.16bc | 0.67 ± 0.00 cd | 1 | 13.04 ± 8.68b | 0.70 ± 0.16a | 0.9978 | 14.38 ± 3.67b | 0.56 ± 0.03a | 0.9987 |

| GPS-WP | 0 ± 0c | 2.72 ± 0.22c | 0.69 ± 0.01c | 0.9949 | 8.08 ± 2.62b | 0.72 ± 0.14a | 0.9985 | 10.96 ± 0.92b | 0.59 ± 0.01a | 0.9991 |

| GPS-SBO | 6.43 ± 1.29a | 8.60 ± 1.12a | 0.58 ± 0.01e | 0.9995 | 48.07 ± 19.58a | 0.35 ± 0.06b | 0.9941 | 27.76 ± 8.84a | 0.43 ± 0.02b | 0.9995 |

| GPS-CA-SBO | 0.53 ± 0.36b | 4.75 ± 0.29b | 0.64 ± 0.01d | 0.9998 | 11.57 ± 3.81b | 0.68 ± 0.19a | 0.9925 | 14.52 ± 3.06b | 0.57 ± 0.02a | 0.9988 |

| GPS-WP-SBO | 0 ± 0c | 2.18 ± 0.18c | 0.73 ± 0.00a | 0.9999 | 8.21 ± 2.06b | 0.69 ± 0.10a | 0.9907 | 11.27 ± 0.80b | 0.60 ± 0.02a | 0.9988 |

The rheological parameters of steady shear including yield stress (τ0), consistency coefficient (K), and flow behavior index (n), which were obtained by fitting the shear stress (τ) and shear rate () data from the steady shear rheological curves across the specific fitting range to Herschel- Bulkley model of . The rheological parameters of dynamic oscillatory shear measurements include k′ and k″ refer to the consistency coefficients (Pa.sn), while n′, n″ are the behavior indexes. a−eData bearing different superscript lowercase letters in the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05).

In contrast, the pure GPS system, the binary systems of GPS-CA and GPS-WP displayed higher values in n but lower values in τ0 and K (Table 1), indicating a weakening of their shear-thinning behaviors. This gave evidence that the incorporation of CA and WP made the GPS system more Newtonian, and the WP was weaker than CA in this aspect. Thinning effects (indicated by decreased viscosity, τ0 or K) were always observed with food proteins and starch gels such as in the food system composed of sodium caseinate and PS (Bertolini, Creamer, Eppink, & Boland, 2005). However, there were some conflicting results (Zhang and Hamaker, 2003, Bertolini et al., 2005, Wang et al., 2017). For example, thickening effects which took place with some food proteins with starch pastes (indicated by increased viscosity, τ0 or K) were also found in sodium caseinate with rice, wheat, cassava, waxy corn, and normal corn starches. Hence, it is tempting to consider that the starch-protein interaction as a multifactorial event and a specific system depended on 1) type and concentration of starch and protein and 2) the processing history of this system (Kumar, Brennan, Mason, Zheng, & Brennan, 2017). For the present study, the decreased viscosity of GPS gels induced by MP can be interpreted as follows: first, MP seemed to work as a plasticizer to prevent the rearrangement of starch molecules in a GPS gel matrix; second, MP may lower or interfere with the recrystallization of starch molecules upon retrogradation (Kumar, Brennan, Mason, Zheng, & Brennan, 2017); finally and most importantly, MP may act as inert fillers or physical barriers restricting the hydrogen bonding between starch molecules in a GPS gel matrix.

As for the binary system of GPS-SBO, it produced comparable n, τ0, and K values to pure GPS system (Table 1), which indicated that the dispersed SBO droplets did not drastically affect the viscosity-shear rate function of GPS gels. A similar trend was observed for the binary system of rice starch (8 %, w/v) and SBO (5 %, w/w), which demonstrated a comparable viscosity (0.323 Pa·s) to the pure starch system (0.345 Pa·s) (Dun, Liang, Zhan, Wei, Chen, Wan, et al., 2020). Unfortunately, these phenomena have not been well interpreted in previous literatures. It was noteworthy that the study of Dun et al. (2020) concluded that oil droplets were capable of preventing the interactions between starch molecules in a gel matrix. This indicated that oil droplets could weaken the 3D starch network and ultimately resulted in a different flow behavior, usually less Newtonian in pure starch system. However, this phenomenon was absent from the present GPS-SBO system as compared to the pure GPS system. As is commonly known, the viscosity of a system usually increases as the shear-induced particle–particle collisions are enhanced. In this context, the identical flow behaviors of GPS-SBO and GPS could be interpreted by the balance between the thinning and thickening effects of SBO droplets on the GPS gel, i.e., their structure disrupting capacity (thinning effect) and their shear-induced collisions (thickening effects). It is widely acknowledged that, in such emulsion-filled gels, the effects of oil droplets on the rheological properties of a system predominately depend on the nature of the interactions between oil droplets and the gel network, which is ultimately dictated by the type of emulsifier adsorbed to the surface of the oil droplets (Farjami & Madadlou, 2019). Based on this and the results observed from CLSM, it can be proposed that for GPS-SBO, where 1) ALCes formed and they spontaneously adsorbed onto O/W interfaces to cover and stabilize the SBO droplets in an emulsion form; 2) the interaction intensity or chemical affinity between SBO droplets and GPS gel networks, mainly dominated by hydrogen bonding between ALCes at O/W interfaces and starch molecules in gel matrixes, was almost in the same scale to the hydrogen bonding between starch molecules in gel networks; 3) in terms of physical or mechanical nature, SBO droplets stabilized by ALCes were highly similar to broken GPS gel particles resulting from shear.

Regarding the ternary systems of GPS-CA-SBO and GPS-WP-SBO, their values in n, τ0, and K were not significantly different from their corresponding oil-absent systems, i.e., GPS-CA and GPS-WP, respectively (Table 1). Together with the abovementioned results, it was concluded that SBO droplets did not substantially affect the steady shear behaviors of primary (GPS, CA, and WP) and binary (GPS-CA and GPS-WP) systems. This inert effect of SBO droplets can be further explained from the viewpoint of lubrication. As reported, the apparent viscosities of emulsion-filled gels were known to be related to their lubrication behaviors and higher viscosity values usually corresponded to lower friction coefficients (Chojnicka, Sala, De Kruif, & Van de Velde, 2009). However, as pointed out by de Vicente et al. (2006), oil droplets as a dispersed phase having a viscosity at least 4 times higher than that of continuous phase could enter the contact zone and dominate the lubrication properties in emulsion, otherwise the friction behavior of the system was controlled by only the dispersion medium (De Vicente, Spikes, & Stokes, 2006). In this context, lubrication dominated by SBO droplets did not apply in the present study due to the much lower viscosity of SBO than that of GPS gel, approximately 33 m·Ps and 64645 m·Ps at a shear rate of 100 s−1, respectively. In most cases, emulsion-filled gels demonstrated lower values in viscosity than the gels without any addition of emulsion (Dun, et al., 2020). This was true for the present study when comparing GPS-WP-SBO with GPS-WP (Fig. 3). However, a conflicting result took place in GPS-CA-SBO and GPS-CA. The curve of GPS-CA was located above that of GPS-CA-SBO, although they insignificantly differed in terms of n, τ0 and K (Fig. 3). The reason underlying this result remains unknown and deserves further investigation. With the current knowledge, it may be attributed to the fact that CA demonstrated a higher affinity to oil droplets than WP. In this scenario, a considerable amount of CA can be seized by SBO droplets from a GPS gel matrix, which highly alleviates the interference of proteins to the formation of a continuous 3D GPS gel network, thus resulting in an increased viscosity to a minor degree. In actual food, the addition of MP and/or vegetable oil can influence the viscosity of the food. Steady shear measurements provide guidance on the addition of MP and vegetable oils to actual foods.

3.2.2. Dynamic oscillatory shear measurements of binary and ternary interaction systems

The mechanical spectra obtained from a frequency sweep are illustrated in Fig. 3 and their quantitative parameters are summarized in Table 1. The Power law model achieved a good fit with the experimental data obtained (R2 = 0.9988–0.9995). In these experiments, the strain applied was so small that no irreversible changes were induced, which allowed for the perception of structure and molecular interactions within the system (Zhang, Mu, & Sun, 2017). In terms of G′ and G′′, the six systems were divided into two groups: 1) for GPS and GPS-SBO, in which G′ was always higher than G′′, attesting to their gel-like nature but to a weak degree, and it should be considering that the differences between the two moduli was less than one decade (Noisuwan, Hemar, Wilkinson, & Bronlund, 2009); 2) for GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-CA-SBO, and GPS-WP-SBO, in which G′ was lower than G′′, demonstrating their liquid-like nature. In the magnitude of either G′ or G′′, the six abovementioned systems were arranged in the same sequence of GPS-SBO > GPS > GPS-CA > GPS-CA-SBO > GPS-WP ≈ GPS-WP-SBO, especially at lower shear frequency. Again, the lower values in tanδ and the weaker frequency dependence of both moduli (higher values in k′ and k′′ and lower values in n′ and n′′) demonstrated the higher solid-like nature of GPS-SBO and GPS than for the others. In comparison, the binary systems of GPS-CA and GPS-WP displayed lower values in G′ and G′′ than for the pure GPS system, which further suggested that MP restrained the formation of a 3D GPS network, mainly by interfering with the hydrogen bonding among starch molecules. In this aspect, WP had higher capacity than CA due to its better dispersity in the GPS gel matrix.

In discussing the differences in the viscoelastic behaviors of GPS and GPS-SBO, GPS-CA and GPA-CA-SBO, as well as GPS-WP and GPS-WP-SBO, the SBO incorporated systems (GPS-SBO, GPA-CA-SBO, and GPS-WP-SBO) can be regarded as emulsion-filled gels, in which emulsion droplets dispersed in a gel made of starch (Farjami & Madadlou, 2019). Depending on their effects on the gel modulus, SBO droplets in emulsion-filled gels were classified as active or inactive fillers, i.e., active fillers increased the gel modulus while inactive fillers decreased or did not affect the gel modulus (Farjami & Madadlou, 2019). Fundamentally, active fillers are believed to connect to gel networks via chemical or physical interactions (so-called bound fillers), while inactive ones display low affinity to gel matrices and behave like small holes in the gel network (unbound fillers) (Sala, Van Aken, Stuart, & Van De Velde, 2007). In this context, oil droplets stabilized by ALCes were active and bound fillers while those stabilized by CA and WP were inactive and unbound fillers. This supported the results mentioned above that, in the present ternary systems, strong starch-starch interactions with weak starch-protein interactions governed the filler-gel network interactions in GPS-SBO and GPA-CA-SBO/GPS-WP-SBO systems, respectively.

The quantitative results of the rheological properties certainly provided useful information on the component interactions involved in these systems. According to the previous explanation, the six abovementioned systems herein were physical gels considering their positive values in n′, which suggested that physical interactions or non-covalent crosslinks (mainly contain hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic interactions) dominated their structures. In contrast to GPS, GPS-SBO exhibited higher values for k′ and k″, while GPS-CA and GPS-WP gave those lower values (although insignificant). This indicated that SBO incorporation made the GPS system more viscoelastic, but it made GPS-CA and GPS-WP a little more viscous. As commonly interpreted, a higher k′ value always indicates stronger molecular interactions within a system (Zhang, Mu, & Sun, 2017). In this context, the SBO enhanced the overall non-covalent crosslinks in the present systems while MP went in the opposite direction. This suggested that the component interactions involved in the present systems are in an intensity order of starch-lipid > starch-starch > starch-protein. Moreover, oil incorporation into binary systems of GPS-CA and GPS-WP did not result in any significant changes in k′, which may declare that: 1) MP was preferential to ALCes in absorbing at O/W interface; or 2) MP and amylose–lipid complexes were concurrently adsorbed to O/W interface in ternary systems. However, GPS-CA-SBO demonstrated slightly higher (although insignificant) k′ values than the GPS-WP-SBO, which was in agreement with the results described above that CA displayed a higher affinity to oil than WP. The addition of milk proteins and/or vegetable oils can influence the viscoelasticity of PSBF. This showed that the results of dynamic oscillatory shear measurements could guide the proper addition of milk proteins and vegetable oils into PSBF with a specifically desired structure.

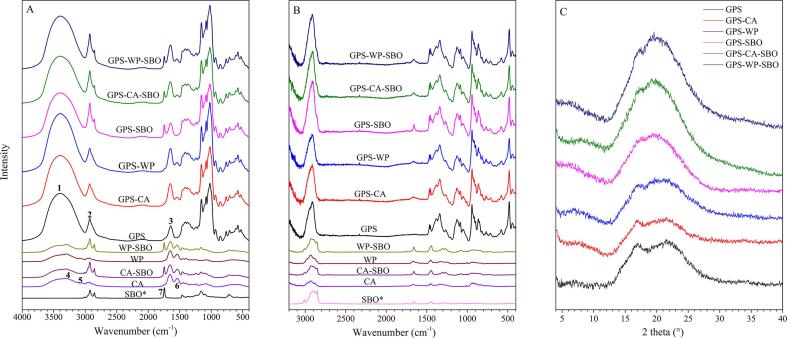

3.3. Chemical bonding involved in GPS-MP-SBO systems

FT-IR, Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction are informative approaches to discern the complex interactions involved in the present systems, which can be inferred from the band dissimilarities between certain systems including sharpening, intensity changes, and shifts of certain bands. In this study, the results of FT-IR, Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction had good reproducibility. Prior to these comparisons, the spectra of FT-IR and Raman should be subjected to normalization to balance the discrepancies in sample size. The bands that were exclusive to the components and inert to the interactions were selected as internal standards. For the present study, the bands at 933 cm−1, 3010 cm−1, and 1544 cm−1 in FT-IR as well as those at 577 cm−1,1003 cm−1, and 1267 cm−1 in Raman were selected for GPS, MP, and SBO, respectively (Mutungi, Passauer, Onyango, Jaros, & Rohm, 2012). The vector normalization was performed against the maximum height of the selected band, and in the present study, it was first done with GPS, then with MP, and finally with SBO. The normalization results showed that the starch containing systems displayed the strongest overall intensities, followed by the binary systems of protein and oil (CA-SBO and WP-SBO), leaving the pure SBO and MP systems with lowest intensities, which were in agreement with the sample size of the PS (6.0 g), SBO (0.9 g) and MP (0.6 g) in the specimens (Fig. 4A and B). Notably, the normalization was of crucial significance in comparing these spectra, but, unfortunately, it has not received enough attention in previous literature.

Fig. 4.

(A) FTIR spectra of freeze- dried powders including GPS, GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-SBO, GPS-CA-SBO, GPS-WP-SBO, CA, WP, CA-SBO, WP-SBO and pure SBO (SBO*). (B) Raman spectra of freeze-dried powder including GPS, GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-SBO, GPS-CA-SBO, GPS-WP-SBO, CA, WP, CA-SBO, WP-SBO and pure SBO (SBO*). (C)X-ray diffraction of freeze-dried powder including GPS, GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-SBO, GPS-CA-SBO, GPS-WP-SBO.

3.3.1. Evidence from FT-IR

The FT-IR spectra of primary, binary, and ternary systems can be observed in Fig. 4A. The big and broad absorbance band ranging from 3600 cm−1 to 3000 cm−1 (1) can be attributed to the free and bound O—H and N—H groups. The intensity and width of this band indicated the O—H and N—H groups in GPS and MP components as well as the O—H groups from absorbed water by these components (Zhang, Mu, & Sun, 2017). Clearly, this band was much more intensive in GPS-containing systems than in those free of GPS. This supports the abovementioned fact that the continuous 3D gel networks in these systems were made of GPS. For the GPS component, the band at 2928 cm−1 (2) can be attributed to C—H stretching and CH2 deformation, while the one at 1641 cm−1 (3) resulted from water being adsorbed in the amorphous regions of starch (Kizil, Irudayaraj, & Seetharaman, 2002). The peaks at 3287 cm−1 (4) and 3073 cm−1 (5) referred to the N—H stretching of protein, which disappeared from GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-CA-SBO, and GPS-WP-SBO, but remained with CA-SBO and WP-SBO (Zeng et al., 2019). In addition, the intensities of bands at 1544 cm−1 (6, the N—H blending (amide II) of protein) decreased in GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-CA-SBO, and GPS-WP-SBO but held in CA-SBO and WP-SBO, in contrast to pure MP systems (Ghaderi, Hosseini, Keyvani, & Gómez-Guillén, 2019). These changes supported the formation of hydrogen bonding between the hydroxyl groups of GPS and the amino groups of MP. The peak at 1746 cm−1 (7) was designated to the C O stretching of oil, which presented a higher intensity in WP-SBO than in CA-SBO (Yuzhen et al., 2014). Similarly, the intensity of this band in GPS-WP-SBO was higher than that in GPS-CA-SBO. This highlighted that CA produced stronger interactions with SBO than WP. It is noteworthy that, in contrast to primary systems (solely GPS, MP, or SBO), binary and ternary systems did not generate any new bands, which again provided evidence that they were physical gels dominated by non-covalent crosslinks. Unlike Wang's study that the formation of starch-oil complexes was detected in their FT-IR results, our FT-IR results did not find a corresponding peak shift (Wang, Zheng, Yu, Wang, & Copeland, 2017). This may be due to the different preparation methods could induce chemical bindings in a different way.

Furthermore, the abovementioned starch-involved interactions were ultimately reflected by the amorphous order or crystallinity of starch in systems. To confirm this, the FT-IR spectra of starch-involved systems were subjected to deconvolution over the wavenumber range of 1200 cm−1 to 900 cm−1, considering the absorbance at 995 cm−1 and 1049 cm−1 which were sensitive to the molecular order or crystalline structure while the band at 1022 cm−1 was linked to the amorphous structure of starch (Zhao et al., 2019). The deconvoluted spectra and their quantitative results are shown in Supplementary Material 3 and Table 2. The area ratios of bands at 995/1022 cm−1 and 1049/1022 cm−1 were capable of quantifying the degrees of short-range (double helix content) and long-range (overall crystallinity) molecular orders of starch, respectively. Clearly, the data in Table 2 revealed that WP restrained the short-rang and long-range molecular orders, while CA did not substantially affect both. Basically, the cooling-induced one-way transitions from coils to single helix, to double helix, and to starch crystallites (the bundle of double helices) were mainly driven by the intra-molecular and inter-molecular hydrogen bonding of starch molecules. In this context, the results of CA and WP in Table 2 show their relatively weak and strong interactions with the starch component, respectively. When SBO is considered, it was ineffective for long-range molecular order or short-range molecular order. Interestingly, the comparison between GPS-WP and GPS-WP-SBO notified that SBO counteracted with the restraints of WP to short molecular orders, which was again attributed to the seizure of WP by SBO droplets from GPS matrix, thus receding its negative result on both molecular orders.

Table 2.

The absorption area ratio of 995 cm−1/1022 cm−1, 1049 cm−1/1022 cm−1 performed by FTIR, FWHM of the band at 480 cm−1 performed by Raman, and crystallinity values of GPS, GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-SBO, GPS-CA-SBO and GPS-WP-SBO.

| 995/1022 | 1049/1022 | FWHM at 480 cm−1 | Crystallinity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPS | 0.81 ± 0.01a | 0.84 ± 0.01a | 19.06 ± 0.36b | 4.48 ± 0.23a |

| GPS-CA | 0.84 ± 0.01a | 0.83 ± 0.01ab | 20.57 ± 0.85a | 2.74 ± 0.50b |

| GPS-WP | 0.73 ± 0.02b | 0.81 ± 0.02b | 20.50 ± 0.06a | 2.71 ± 0.59b |

| GPS-SBO | 0.84 ± 0.01a | 0.83 ± 0.01ab | 19.41 ± 0.18b | 1.2 ± 0.11c |

| GPS-CA-SBO | 0.83 ± 0.02a | 0.82 ± 0.02ab | 19.21 ± 0.03b | 1.73 ± 0.35c |

| GPS-WP-SBO | 0.80 ± 0.01ab | 0.81 ± 0.01b | 19.34 ± 0.24b | 1.75 ± 0.33c |

a−cValues are means ± SD. Means with similar letters in a column do not differ significantly (p > 0.05).

3.3.2. Evidence from Raman spectroscopy

The normalized Raman spectra of the present studied systems are shown in Fig. 4B. The bands observed with three components in ternary systems are summarized in Supplementary Material 4. Regarding MP components, CA and WP produced similar spectra profiles but CA was present in a lesser intensity than WP, which may result from a higher aggregating nature and the state of the micelles of CA. Obviously, the typical bands from oil at 3013 cm−1 (=C—H stretch) and 2856 cm−1 (CH2 stretch) significantly weakened in its binary systems with protein (CA-SBO and WP-SBO), and these bands sharply receded even diminished in systems concurrently containing starch, suggesting the involvement of Van der Waals forces and hydrophobic interactions in the interactions of SBO with GPS and MP. In the binary systems of GPS and MP, the protein-specific band at 1671 cm−1 (amide I) broadened, which possibly resulted from the hydrogen bonding among the two components. As SBO was blended with GPS, its specific band at 1655 cm−1 (C O stretch) sharply intensified, indicating their interactions. As this band was compared, its intensity in CA-SBO was weaker than that found in WP-SBO, which can be interpreted by stronger SBO interactions and the higher emulsifying capacity of CA than WP.

Besides the direct evaluation from spectrum profile, the interactions involved in these systems can be explored with Raman spectroscopy by using the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the band at 480 cm−1, proven to be a good indicator of the short-range molecular order of starch and it certainly varied in its interactions with oil and protein (Wang et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2017). Generally, a smaller FWHM value of the band at 480 cm−1 indicates a greater degree of short-range ordered structures (Chao, Cai, Yu, Copeland, Wang, & Wang, 2018). As shown in Table 2, the binary systems of GPS-CA and GPS-WP demonstrated higher FWHM values, in contrast to pure GPS system, while the one with GPS-SBO as well as the two ternary systems (GPS-CA-SBO and GPS-WP-SBO) displayed comparable FWHM values. More directly, both CA and WP restrained the short-range molecular order of GPS. This was comparable to the results obtained in FT-IR for WP but more notable for CA. However, opposite effects were concluded for SBO in terms of its effect on the short-range molecular order of GPS. Unfortunately, the reason underlying this paradox remains unknown. As with in FT-IR, SBO was found to counteract MP and eliminate its restraining effects in ternary systems. However, the data presented by Chao et al. (2018) indicated that both oil (lauric acid) and protein (β-lactoglobulin) incorporations resulted in significant increases in the short-range molecular order of gelatinized maize starch. These discrepancies may be attributed to the differences in the physicochemical properties of the involved components.

3.3.3. Evidence from X-ray diffraction

The XRD patterns and relative crystallinity of the freeze-dried samples are shown in Fig. 4C. A notability analysis of the crystallinity values is illustrated in Table 2. All samples showed only slight reflection peaks at 17.0 2θ angles. Reflection peaks at 17.0 corresponded to the amorphous starch formed by the decrease of crystallinity of PS after processing. The RC of the other samples was lower than that for the GPS. This might possibly be because the GPS had lost its crystalline structure completely by the process of gelatinization, but some crystalline structure could be detected because of the retrogradation of the samples during cooling and freeze-drying process. However, the RC of the other samples (GPS-CA, GPS-WP, GPS-SBO, GPS-CA-SBO, GPS-WP-SBO) was lower than that of GPS because of the addition of MP, SBO, and both MP and SBO which could retard the retrogradation of GPS (Ji, Liu, Zhang, Yu, Xiong, & Sun, 2017). This may be because the crystalline structure of the GPS was seriously damaged in the process of gelatinization and homogenization. From the RCs for all test samples, the addition of MP, SBO, and both MP and SBO could enhance the damage to the crystalline structure of GPS in this situation. Fig. 2(5–11) shows that MP and/or SBO were dispersed into the 3D GPS networks.

4. Conclusions

Most foods are complicated systems containing various soft materials such as starch, protein, and lipids. In such systems, interactions among these food components play important roles in establishing food quality, particularly on the microstructure, rheological properties, and chemical bonding within those food products. The present study revealed these interactions with a simplified binary and ternary model systems consisting of potato starch, milk protein (CA and WP), and soybean oil. The obtained results showed that the ternary system of three components was an emulsion-filled gel with milk protein and ALCes. The ternary system includes emulsifiers and a starch dominated gel matrix. Diverse non-covalent interactions were found to participate in the formation of ordered structures in this model system. This study disclosed the underlying mechanism in the quality formation of gelatinized potato starch gel network from a component interaction view and benefited the design of food products containing potato starch, milk protein, and soybean oil with desired attributes. However, due to the extreme complexity of such systems, the present study certainly has some limitations. Future investigations on this ternary system can address the following aspects: 1) the details on the formation of ALCes and the roles of the three components as well as the processing conditions; 2) the contributions of milk protein and ALCes on the formation of an O/W interface film; and 3) the scales of the non-covalent interactions founded herein.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Youth Science and Technology Fund of Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences ([2020]03) and Guizhou Province Science and Technology Foundation ([2020]1Y158). The grateful thanks to Suranaree University of Technology and Southwest University for the chemicals and equipment of this study were also expressed here.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100495.

Contributor Information

Guohua Zhao, Email: zhaogh@swu.edu.cn.

Siwatt. Thaiudom, Email: thaiudom@g.sut.ac.th.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary figure 1.

Supplementary figure 2.

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- Álvarez M.D., Fernández C., Olivares M.D., Jiménez M.J., Canet W. Sensory and texture properties of mashed potato incorporated with inulin and olive oil blends. International Journal of Food Properties. 2013;16(8):1839–1859. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2011.610211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini A.C., Creamer L.K., Eppink M., Boland M. Some rheological properties of sodium caseinate− starch gels. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2005;53(6):2248–2254. doi: 10.1021/jf048656p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun K., Hanewald A., Vilgis T.A. Milk emulsions: Structure and stability. Foods. 2019;8(10):483. doi: 10.3390/foods8100483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao C., Cai J., Yu J., Copeland L., Wang S., Wang S. Toward a better understanding of starch–monoglyceride–protein interactions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2018;66(50):13253–13259. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, He, X., Zhang, B., Fu, X., Li, L., & Huang, Q. (2018). Structure, physicochemical and in vitro digestion properties of ternary blends containing swollen maize starch, maize oil and zein protein. Food Hydrocolloids, 76, 88-95. 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.04.025.

- Chen X., He X., Zhang B., Fu X., Jane J., Huang Q. Effects of adding corn oil and soy protein to corn starch on the physicochemical and digestive properties of the starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2017;104:481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chojnicka A., Sala G., De Kruif C.G., Van de Velde F. The interactions between oil droplets and gel matrix affect the lubrication properties of sheared emulsion-filled gels. Food hydrocolloids. 2009;23(3):1038–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2008.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dankar I., Haddarah A., Sepulcre F., Pujolà M. Assessing mechanical and rheological properties of potato puree: Effect of different ingredient combinations and cooking methods on the feasibility of 3D printing. Foods. 2019;9(1):21. doi: 10.3390/foods9010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankar, I., Pujolà, M., El Omar, F., Sepulcre, F., & Haddarah, A. (2018). Impact of mechanical and microstructural properties of potato puree-food additive complexes on extrusion-based 3D printing. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 11(11), 2021-2031. 10.1007/s11947-018-2159-5.

- Dapueto N., Troncoso E., Mella C., Zúñiga R.N. The effect of denaturation degree of protein on the microstructure, rheology and physical stability of oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions stabilized by whey protein isolate. Journal of Food Engineering. 2019;263:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Kruif C.G., Huppertz T., Urban V.S., Petukhov A.V. Casein micelles and their internal structure. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2012;171:36–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vicente J., Spikes H., Stokes J. Viscosity ratio effect in the emulsion lubrication of soft EHL contact. 2006 doi: 10.1115/1.2345400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dun H., Liang H., Zhan F., Wei X., Chen Y., Wan J.…Li B. Influence of O/W emulsion on gelatinization and retrogradation properties of rice starch. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;103 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fanta G., Felker F., Eskins K., Baker F. Aqueous starch–oil dispersions prepared by steam jet cooking. Starch films at the oil–water interface. Carbohydrate Polymers. 1999;39(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(98)00158-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fanta G., Felker F., Shogren R., Knutson C. Starch–paraffin wax compositions prepared by steam jet cooking. Examination of starch adsorbed at the paraffin–water interface. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2001;46(1):29–38. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(00)00279-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farjami T., Madadlou A. An overview on preparation of emulsion-filled gels and emulsion particulate gels. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2019;86:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.02.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R., Ye F., Wang Y., Lu Z., Yuan M., Zhao G. The spatial-temporal working pattern of cold ultrasound treatment in improving the sensory, nutritional and safe quality of unpasteurized raw tomato juice. Ultrasonics sonochemistry. 2019;56:240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi J., Hosseini S.F., Keyvani N., Gómez-Guillén M.C. Polymer blending effects on the physicochemical and structural features of the chitosan/poly (vinyl alcohol)/fish gelatin ternary biodegradable films. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;95:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Chen X., Wang S., Zhu J. In: Starch Structure, Functionality and Application in Foods. Wang S., editor. Springer; 2020. Amylose–lipid complex; pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ji N., Liu C., Zhang S., Yu J., Xiong L., Sun Q. Effects of chitin nano-whiskers on the gelatinization and retrogradation of maize and potato starches. Food Chemistry. 2017;214:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizil R., Irudayaraj J., Seetharaman K. Characterization of irradiated starches by using FT-Raman and FTIR spectroscopy. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(14):3912–3918. doi: 10.1021/jf011652p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar L., Brennan M., Brennan C., Zheng H. Thermal, pasting and structural studies of oat starch-caseinate interactions. Food Chemistry. 2022;373 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar L., Brennan M.A., Mason S.L., Zheng H., Brennan C.S. Rheological, pasting and microstructural studies of dairy protein–starch interactions and their application in extrusion-based products: A review. Starch-Stärke. 2017;69(1–2):1600273. doi: 10.1002/star.201600273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Ye F., Zhou Y., Lei L., Zhao G. Rheological and textural insights into the blending of sweet potato and cassava starches: In hot and cooled pastes as well as in fresh and dried gels. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;89:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.11.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Jæger T.C., Nielsen S.B., Ray C.A., Ipsen R. Interactions in heated milk model systems with different ratios of nanoparticulated whey protein at varying pH. International Dairy Journal. 2017;74:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2016.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson A., Gaonkar A.G. In: Interactions of Ingredients in Food Systems: An Introduction. (5th ed.). Kilara A., editor. CRC Taylor & Francis; 2006. Ingredient interactions: Effects on food quality; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mutungi C., Passauer L., Onyango C., Jaros D., Rohm H. Debranched cassava starch crystallinity determination by Raman spectroscopy: Correlation of features in Raman spectra with X-ray diffraction and 13C CP/MAS NMR spectroscopy. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2012;87(1):598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noisuwan A., Hemar Y., Wilkinson B., Bronlund J.E. Dynamic rheological and microstructural properties of normal and waxy rice starch gels containing milk protein ingredients. Starch-Stärke. 2009;61(3–4):214–227. doi: 10.1002/star.200800049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pracham S., Thaiudom S. The effect of protein content in jasmine rice flour on textural and rheological properties of jasmine rice pudding. International Food Research Journal. 2016;23:1379–1388. http://ifrj.upm.edu.my/23%20(04)%202016/(5).pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sala G., Van Aken G.A., Stuart M.A.C., Van De Velde F. Effect of droplet–matrix interactions on large deformation properties of emulsion-filled gels. Journal of Texture Studies. 2007;38(4):511–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4603.2007.00110.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thaiwong N., Thaiudom S. Stability of oil-in-water emulsion influenced by the interaction of modified tapioca starch and milk protein. International Journal of Dairy Technology. 2021;74:307–315. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thaiudom S., Pracham S. The influence of rice protein content and mixed stabilizers on textural and rheological properties of jasmine rice pudding. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018;76:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.11.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Zhao S., Min G., Qiao D., Zhang B., Niu M.…Lin Q. Starch-protein interplay varies the multi-scale structures of starch undergoing thermal processing. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021;175:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Chao C., Cai J., Niu B., Copeland L., Wang S. Starch–lipid and starch–lipid–protein complexes: A comprehensive review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2020;19(3):1056–1079. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zheng M., Yu J., Wang S., Copeland L. Insights into the Formation and Structures of Starch–Protein–Lipid Complexes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2017;65(9):1960–1966. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Ye F., Liu J., Zhou Y., Lei L., Zhao G. Rheological nature and dropping performance of sweet potato starch dough as influenced by the binder pastes. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018;85:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Zhong F., Goff H.D., Li Y. Study on starch-protein interactions and their effects on physicochemical and digestible properties of the blends. Food Chemistry. 2019;280:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzhen, L., Changwen, D., Yanqiu, S., & Jianmin, Z. (2014). Characterization of rapeseed oil using FTIR-ATR spectroscopy. Journal of Food Science and Engineering, 4, 244-249. https://doi: 10.17265/2159-5828/2014.05.004.

- Zeng P., Chen X., Qin Y.-R., Zhang Y.H., Wang X.P., Wang J.Y.…Zhang Y.S. Preparation and characterization of a novel colorimetric indicator film based on gelatin/polyvinyl alcohol incorporating mulberry anthocyanin extracts for monitoring fish freshness. Food Research International. 2019;126 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Mu T., Sun H. Calorimetric, rheological, and structural properties of potato protein and potato starch composites and gels. Starch-Stärke. 2017;69(7–8):1600329. doi: 10.1002/star.201600329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Hamaker B.R. A three component interaction among starch, protein, and free fatty acids revealed by pasting profiles. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(9):2797–2800. doi: 10.1021/jf0300341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Maladen M., Campanella O.H., Hamaker B.R. Free fatty acids electronically bridge the self-assembly of a three-component nanocomplex consisting of amylose, protein, and free fatty acids. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(16):9164–9170. doi: 10.1021/jf1010319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T., Li X., Zhu R., Ma Z., Liu L., Wang X., Hu X. Effect of natural fermentation on the structure and physicochemical properties of wheat starch. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2019;218:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.