Abstract

Child Advocacy Centers (CACs) are well-positioned to identify children with mental health needs and facilitate access to evidence-based treatment. However, use of evidence-based screening tools and referral protocols varies across CACs. Understanding barriers and facilitators can inform efforts to implement mental health screening and referral protocols in CACs. We describe statewide efforts implementing a standardized screening and referral protocol, the Care Process Model for Pediatric Traumatic Stress (CPM-PTS), in CACs. Twenty-three CACs were invited to implement the CPM-PTS. We used mixed methods to evaluate the first two years of implementation. We quantitatively assessed adoption, reach, and acceptability; qualitatively assessed facilitators and barriers; and integrated quantitative and qualitative data to understand implementation of mental health screening in CACs. Eighteen CACs adopted the CPM-PTS. Across CACs, screening rates ranged from 10% to 100%. Caregiver ratings indicated high acceptability. Facilitators and barriers were identified within domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Qualitative findings provided insight into adoption, reach, and caregivers’ responses. Our findings suggest screening for traumatic stress and suicidality in CACs is valued, acceptable, and feasible. Implementation of mental health screening and referral protocols in CACs may improve identification of children with mental health needs and support treatment engagement.

Keywords: Child Advocacy Center, implementation, mental health screening, child traumatic stress

Child Advocacy Centers (CACs) use multidisciplinary teams (e.g., law enforcement, child welfare, prosecution, medicine, mental health, victim advocacy) to coordinate interagency responses to allegations of sexual abuse, physical abuse and other forms of maltreatment (Elmquist et al., 2015; Herbert & Bromfield, 2019). Because CACs are often families’ first link to services following maltreatment allegations, they are well-positioned to identify children with mental health needs and facilitate access to evidence-based treatment within a high risk population (Elmquist et al., 2015; Herbert & Bromfield, 2016, 2017; Jackson, 2004; Jones et al., 2007; National Children’s Alliance, 2017). CACs have made excellent progress in increasing opportunities for access to evidence-based treatment for the children they serve; in 2018, 94% of CACs reported providing access to at least one evidence-based treatment (e.g., Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Cohen & Mannarino, 2015) (National Children’s Alliance, 2019). However, 39% of CACs do not offer any onsite mental health screening to evaluate the urgency or specify specific type of mental health needs (National Children’s Alliance, 2019), and the extent to which CACs facilitate referrals to and engagement in services varies.

Evidence-based screening tools and facilitated referrals may improve CAC capacity to identify children with mental health needs and to support engagement with appropriate treatment, as has been found in other settings such as primary care (Siu & US Preventative Services Task Force, 2016; Wissow et al., 2013). The Care Process Model for Pediatric Traumatic Stress (CPM-PTS) is a standardized approach to pediatric mental health screening and referral in the context of a potentially traumatic experience (Intermountain Healthcare, 2020). It provides structured pathways and technology-guided decision support to assist frontline CAC staff in screening for and responding to symptoms of posttraumatic stress and suicidality (Intermountain Healthcare, 2020).

Implementation of structured screening and referral protocols such as the CPM-PTS may improve recognition of suicidality and mental health needs, reduce variability and inefficient use of resources, and facilitate engagement in treatment (Conners-Burrow et al., 2012; NCTSN Child Welfare Collaborative Group, 2017). Implementation of new practices is often challenging, and little is known about barriers to and facilitators of structured mental health screening in Child Advocacy Centers. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) provides a framework for understanding determinants (i.e., barriers and facilitators) of implementation in diverse settings (Damschroder et al., 2009). Using CFIR to identify and characterize facilitators and barriers to implementation can advance our understanding of implementation in CACs.

There are five CFIR domains: Intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and the process of implementation. Relevant intervention characteristics include the advantages of the intervention relative to others, the extent to which it can be adapted to local needs, complexity, and cost. For example, screener length and the time needed to complete screening are intervention characteristics that may affect implementation of mental health screening in CACs (Conners-Burrow et al., 2012). The outer setting includes factors external to the organization, such as public policies, funding, and client needs, while the inner setting includes characteristics, culture, and climate of the organization. In the CAC context, outer setting factors include requirements or priorities set by accrediting organizations (i.e., National Children’s Alliance) and funders, while the inner setting includes CAC characteristics such as location, team climate and culture, and leadership. Individual characteristics of staff, such as knowledge and self-efficacy, also affect implementation (Damschroder et al., 2009). For example, CAC staff with clinical training are likely to differ from staff without clinical training in self-efficacy for discussing mental health issues with families. Lastly, implementation is an active process with dynamic changes over time. Identifying relevant determinants and improving our understanding of implementation in CACs can provide ideas for how to reduce barriers and leverage facilitators to improve outcomes in future implementation efforts.

In this paper, we examine implementation of the CPM-PTS in CACs across the state of Utah. We used simultaneous mixed methods to evaluate the first two years (April 2018 to March 2020) of a statewide effort to implement the CPM-PTS in CACs. Our study had three goals: 1) use quantitative data to evaluate implementation outcomes, 2) use qualitative data to identify facilitators and barriers to implementation, and 3) integrate quantitative and qualitative data to better understand the implementation of the CPM-PTS in CACs.

Methods

The Care Process Model for Pediatric Traumatic Stress (CPM-PTS)

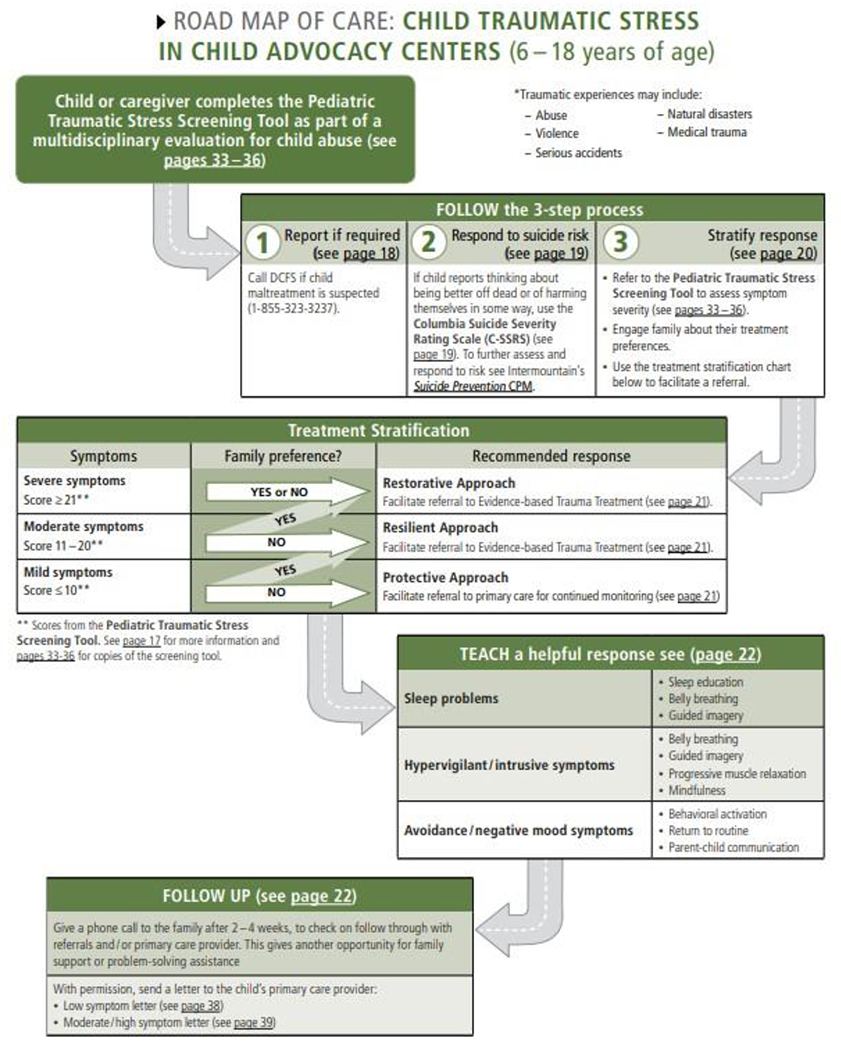

The CPM-PTS road map of care is shown in Figure 1, and the CPM-PTS is available at https://intermountainhealthcare.org/ckr-ext/Dcmnt?ncid=529796906. The implementation team built two instruments aligned with the CPM-PTS screening and decision support processes into REDCap (Harris et al., 2009, 2019): the Pediatric Traumatic Stress Screening Tool and a Pediatric Traumatic Stress Decision Support Tool.

Figure 1.

CPM-PTS Road Map of Care

Pediatric Traumatic Stress Screening Tool.

The Pediatric Traumatic Stress Screening Tool is a client-facing screening tool. It uses caregiver-report for children 5-10 years of age and self-report for adolescents 11-18 years of age. The screening tool includes a demographic questionnaire, two yes/no questions about experiencing potentially traumatic events followed by a prompt to describe the event, the 11-item UCLA PTSD Reaction Index Brief Form to assess traumatic stress symptoms (Rolon-Arroyo et al., 2020), and a question assessing risk for suicide and/or self-harm (i.e., “thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way”) (Patient Health Questionnaire-Adolescent; Richardson et al., 2010).

Pediatric Traumatic Stress Decision Support Tool.

After the Pediatric Traumatic Stress Screening Tool is completed, the staff-facing Decision Support Tool in REDCap guides CAC staff through a three-step process: 1) report newly identified concerns for maltreatment, 2) evaluate and respond to suicide risk, and 3) provide brief interventions and/or mental health referrals to meet identified needs (Intermountain Healthcare, 2020). First, if a potentially traumatic event is endorsed, staff review the free-text description to determine whether there are concerns for safety or maltreatment (beyond those bringing the child to the CAC) that warrant child welfare referral. Second, when there is a positive response to the question about thoughts of suicide or self-harm, staff are prompted to administer the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Mundt et al., 2013; Posner et al., 2011). The C-SSRS classifies suicide risk as low, moderate, or high, and staff are prompted to take appropriate actions based on the child’s risk level (e.g., safety planning, crisis evaluation). Finally, the Decision Support Tool classifies traumatic stress symptom level as low, moderate, or high, and staff assess functional impairment by asking about the child’s functioning at home, school, and with friends. Based on symptom level and functional impairment, the tool suggests appropriate treatment options for the staff to discuss with the family, ranging from follow-up with the child’s primary care provider in a child with minimal symptoms to referral to evidence-based trauma treatment when symptoms are elevated. The tool also suggests options for brief interventions (e.g., belly breathing for elevated hyperarousal symptoms) and additional resources (e.g., mental health apps). Although the tool recommends appropriate actions at each step, staff remain free to take other actions in place of or in addition to those suggested. Staff are prompted to record the actions taken in REDCap.

Setting for Implementation

All 24 Utah CACs were invited to implement the CPM-PTS. Two CACs in the same county shared staff and record-keeping and are counted as one CAC in this study, resulting in a total of 23 CACs. The 23 CACs varied in the number of clients served annually (18-1127 in 2019), staff size (1-17), and rurality (5 urban, 10 rural, 8 frontier; Utah Department of Health, Office of Primary Care & Rural Health, 2018). CACs were categorized as clinical or non-clinical based on the education and training of the individual(s) responsible for administering the CPM-PTS. CACs were labeled “clinical” if any staff administering the CPM-PTS had a clinical degree and/or license in a mental health field (e.g., Bachelors or Masters in Social Work, Certified Mental Health Clinician, Licensed Clinical Social Work) and “non-clinical” if no involved staff members had a clinical degree or license. All implementation and data collection efforts were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Pre-Implementation

Prior to implementation, all CAC directors and medical staff representatives attended at least one presentation on the background and rationale for the CPM-PTS. The Utah Office for Victims of Crime released a specific Request for Applications to support CACs in implementing the CPM-PTS and contracting with therapists to receive referrals for evidence-based trauma treatment. Initially, 10 CACs applied for the funding, and 9 grants were awarded. A subsequent round of funding the following year increased the number of funded CACs to 17 out of 23 CACs, at which point all CACs who applied for funding had been awarded. Grant funds were used to hire or dedicate existing staff to administer the CPM-PTS, to hire and/or contract with a mental health provider to provide trauma-focused treatment, and/or to support staff attendance at trainings and conferences. CACs without funding were still invited to participate in training and implementation efforts.

Training, Consultation, and Technical Assistance

The implementation team (Pediatric Integrated Post-Trauma [PIPS] team) began CPM-PTS training for CACs in February 2018, and CPM-PTS use began in April 2018. Close to half of the CACs (n = 11) participated in the first training opportunity in February 2018. Trainings for additional CACs were completed between August 2018 and September 2019. Trainers used the same PowerPoint slide deck for each training. All trainings were offered in-person at individual CACs or at shared training sites, incorporating didactic instruction and role playing, with a duration of 1 ½ to 2 hours. The trainings offered an overview of the CPM-PTS, a brief rationale for using the CPM-PTS in the CAC setting, and clear guidance on implementing the CPM-PTS in their CAC. The last training segment was a discussion with participants regarding crisis response and trauma-informed services in their respective communities and troubleshooting areas for improvement.

The PIPS team provided monthly consultation calls during the first six months and ongoing technical assistance for two years. Consultation calls began with training on one component of trauma-informed care (e.g., suicide prevention, responding to screening results), followed by open question and answer, and demonstration of how to teach a coping skill to a family. The PIPS team regularly contacted CACs to offer assistance and provided help to individual staff as needed to address technical problems, workflows, challenging cases, and any questions or concerns. Finally, the PIPS team distributed infographics at least every other month with descriptive information on CPM-PTS use.

Participants and Measures

Quantitative Measures of Implementation Outcomes

Adoption.

We constructed two measures of adoption (Proctor et al., 2011) for each CAC based on data from the PIPS team. First, we used a dichotomous (Yes/No) variable to indicate whether anyone affiliated with the CAC completed training to use the CPM-PTS. Second, we used a dichotomous (Yes/No) variable to indicate whether anyone affiliated with the CAC ever administered the CPM-PTS via the electronic screening system developed for this project (i.e., any screening record in REDCap).

Reach.

We assessed reach of the CPM-PTS by calculating screening rates (i.e., completed screenings / eligible children) in CACs that adopted the CPM-PTS. Children between 5 and 18 years old seen at participating CACs for an initial forensic interview were eligible to receive the CPM-PTS. The Utah Attorney General’s office, responsible for statewide coordination of CAC services, provided reports of the number of children served monthly by each CAC, and we used these data to calculate the number of eligible children served by each CAC. Data from the CPM-PTS (Pediatric Traumatic Stress Screening Tool; Pediatric Traumatic Stress Decision Support Tool) were collected through REDCap as staff administered the CPM-PTS. We excluded records of children seen solely for therapy or follow-up, those with a primary language other than English or Spanish, and records lacking a date or site of administration from analyses. We used the number of screening records as the numerator for calculating reach. Two CACs were excluded from analyses of reach because they completed screenings on paper rather than electronically.

We used quarterly screening rates (i.e., 3-month periods) to minimize monthly fluctuations, especially for CACs serving only a small number of children. All CACs included in these analyses have at least two quarters of screening data. Because the timing of implementation varied by CAC, we consider quarterly rates relative to time since training (first quarter since training, second quarter since training, etc.).

Acceptability.

We assessed caregivers’ perceptions of the acceptability of the CPM-PTS with three items from a routine, anonymous, caregiver satisfaction survey (Rehnborg et al., 2009). CAC staff administered the caregiver satisfaction survey at the end of each family’s visit to the center. The Attorney General’s office provided data from caregiver satisfaction surveys collected from CACs during the 2-year period. Caregivers of 5–18-year-old children rated the following statements on a 4-point scale (1 ‘Strongly Disagree’ to 4 ‘Strongly Agree’): “I was comfortable filling out or comfortable with my child filling out the questionnaire;” “I learned something from the questionnaire;” and “Talking with staff about the questionnaire helped me understand how my child might behave.”

Qualitative Interviews: Implementation Barriers and Facilitators

Approximately six months after the initial training, we invited at least one staff member from CACs that had adopted the CPM-PTS to participate in a semi-structured qualitative interview. Participants were staff who administered the CPM-PTS, some of whom were also responsible for overseeing CPM-PTS implementation in their CAC. A single interviewer (KAB) interviewed each staff member to explore facilitators and barriers to CPM-PTS implementation in CACs. Interviews were completed with 20 staff at 10 CACs.

Analyses

Quantitative Analyses: Adoption, Reach, and Acceptability

We examined descriptive statistics for adoption and acceptability. For reach, we plotted quarterly screening rates for each CAC to examine variability in reach over the two-year period. We calculated the average screening rate across quarters for each CAC (i.e., overall reach for each CAC). In addition, we calculated the average screening rate for each quarter across CACs to look for trends in reach over time.

Qualitative Analyses: Implementation Barriers and Facilitators

We audio-recorded the qualitative interviews, transcribed recordings verbatim, and uploaded transcriptions to Dedoose, a secure web-based application supporting collaborative qualitative research analysis (Dedoose, 2021). We utilized a combined deductive and inductive approach to coding (Bingham & Witkowsky, 2021; Thomas, 2006). Three researchers completed initial coding. Coding began with the three researchers analyzing the same excerpt of transcription, and then meeting shortly after that to reach consensus on codes throughout. This inter-rater coding process was replicated three times until reasonable consensus on codes and process was met. Two of the initial three researchers (KB and BT) refined codes and inductively developed themes. Then, we organized themes into CFIR domains (Intervention Characteristics, Outer Setting, Inner Setting, Characteristics of Individuals, Process) to support integration of the findings with the broader implementation science literature. We achieved thematic saturation for staff perspectives on facilitators and barriers.

Mixed Methods Integration

After analyzing quantitative and qualitative data separately, we merged these data with the goal of expansion (Creswell & Clark, 2011; Palinkas et al., 2011). These analyses explored the extent to which qualitative data provide insight into and deeper understanding of the results of our quantitative analyses.

Results

Quantitative Results: Implementation Outcomes

Adoption.

All CACs within the state were offered training in the CPM-PTS. Our first measure of adoption was based on participation in training. Twenty-one of 23 CACs (91%) had at least one staff who completed training. Our second measure of adoption was based on use of the CPM-PTS as indicated by completion of the screening tool in REDCap at least once. Using this measure, 18 CACs adopted the CPM-PTS – 78% of all CACs in the state and 86% of the CACs that completed training. The CPM-PTS was adopted by 80% of urban CACs (4 of 5), 90% of rural CACs (9 of 10), and 63% of frontier CACs (5 of 8). The three frontier CACs that did not adopt the CPM-PTS after training were overseen by a shared director. The CPM-PTS was administered by staff with formal clinical training in 5 CACs and by staff without formal clinical training in 13 CACs (72% of adopting CACs).

Reach.

Data on reach (i.e., screening rates) were available for 16 of 18 adopting CACs. During the 2-year period, these 16 CACs introduced the CPM-PTS to 2569 children. Across CACs, the average screening rates for the 2-year period ranged from 10% to 100%, with an average of 53% across CACs (SD = 24%). Four CACs had screening rates >75%, 4 CACs had screening rates of 50-74%, 7 CACs had screening rates 25-49%, and 1 CAC had a screening rate <25%. There were no differences in screening rates between CACs with and without clinically trained staff (M = 42% vs. M = 56%, t = 1.05, ns). Similarly, there were no differences in screening rates between urban, rural, and frontier CACs (F = 1.48, ns). There was a trend for CACs who served fewer children to have higher screening rates (r = −.43, p < .10).

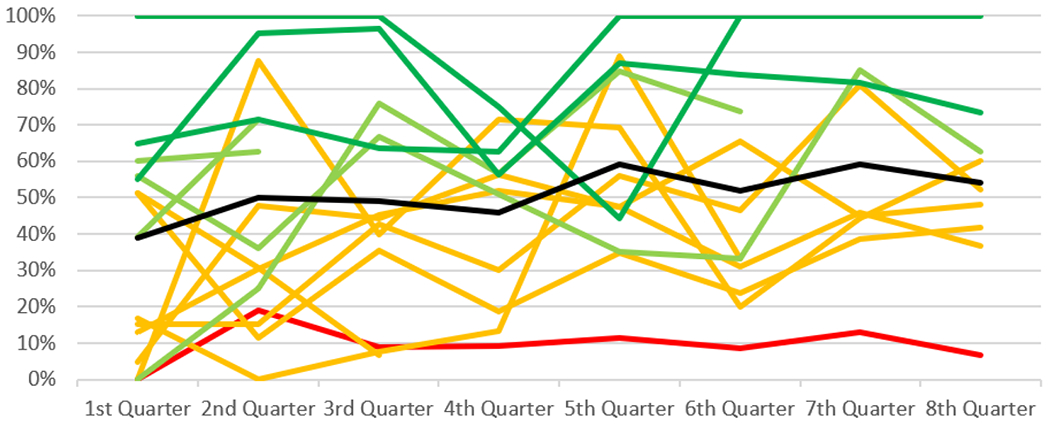

The black line in Figure 2 shows the average screening rate by quarter since training. The first quarter after training had the lowest average screening rate across CACs (39%); average screening rates for later quarters were relatively stable (range 46-59%). However, there was considerable variability both within and across CACs. Colored lines in Figure 2 show screening rates over time for each CAC.

Figure 2.

Screening Rates Over Time by Child Advocacy Center

Note: The black line shows the average screening rate across all CACs. Each colored line shows screening rates for an individual CAC. Dark green: average screening rate >75%. Light green: average screening rate 50-74%. Orange: average screening rate 25-49%. Red: average screening rate <25%.

Acceptability.

During the two-year period for this study, caregivers at 16 CACs that adopted the CPM-PTS answered 3 items about it on end-of-visit satisfaction surveys (n = 439-519 across items). On a scale from 1-4, caregivers generally agreed they felt comfortable completing (or having their child complete) the questionnaire (M = 3.72, SD = 0.54), learned something from the CPM-PTS (M = 3.34, SD = 0.84), and that the CPM-PTS helped their understanding of how their child might behave (M = 3.49, SD = 0.79).

Qualitative Results: Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation by CFIR Domains

Example quotes organized by theme and CFIR domain are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Qualitative Results: Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation Organized by CFIR Domains

| Intervention Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Advantages of CPM-PTS | ID_17: I think it’s great. I think it’s an awesome tool and I think that it asks questions that are very thorough and ones that need to be asked. ID_20: We all need to be a little more proactive with helping out these kids. 100% I would advocate that we all should be doing it. ID_13: We’re leaving them with not just referrals for further services, but actual tools. So, they’re walking out of here with the belly breathing, the yoga, the guided imagery, whatever it is we are able to teach to them, they are able to…carry that with them. |

| Challenges to Administering | ID_14: They went ahead and did the survey and somehow, we don’t know if it’s a glitch on our side, a glitch on the child’s side, or a glitch on the iPad, it didn’t record the answers. We couldn’t get to the decision tool. ID_04: I know there has been a few issues of Redcap crashing, which is frustrating for the family. |

| Outer Setting | |

| External Funding | ID_09: We had a specific grant for me to be there to administer [the CPM-PTS], so we have that resource so that I could do that. ID_08: [The PIPS team] worked out [funding] with VOCA before coming to us and saying hey we want you to implement this at your centers…and still to this day being able to tweak our grant and being able to call [the PIPS team]. |

| Relationships with Mental Health Providers | ID_19: We’ve worked a pretty good relationship with our mental health, so we can call them right away and get them scheduled when the children are still here. ID_13: We had the therapist come down. They were able to…observe the kids, see how they were interacting, and better help them better prepare for receiving therapy services. |

| Appreciative Families | ID_09: The feedback I have been getting when I talk to the parents has been very positive, they are so glad they know. …They’ve all been very grateful to know the information that I give them. ID_15: For the parents, the majority of them are very grateful to have additional information about their child and to know where their child stands in regard to those circumstance. Not very often has a family been talking to a child, especially with suicidal ideation, about that. I think it is kind of a relief to hear what exactly is going on and to receive some guidance on how to address it. ID_02: His score is really high and it was terrifying for them obviously, you know…’what does a high score mean?’…But we explained it and then we were able to get them into our therapist really quickly…otherwise they would not have known.’ |

| Overwhelmed Caregivers | ID_01: It seems to me that they’re pretty put off by having to spend another minute at our center after learning some of the allegations that happened to their child. ID_04: It was difficult for them to…do the survey about their child, because they themselves were in such crisis that it wasn’t really conducive to have them sit down, read, and answer the questions. |

| Inner Setting | |

| Leadership and Team Support | ID_03: [What has made uptake possible?] Just cooperation from all the different agencies involved, being patient while it’s done and stuff like that. ID_20: Our executive director thinking it would be a positive thing for our community, knowing that Utah has a very high rate of suicide. All that…I think just being a little more proactive. Our executive director is an advocate of those things. |

| Fit with Workflows | ID_19: The most natural ones are with the teenager, done right after the interview. It seems to flow. ID_03: I would recommend it [the CPM-PTS] but I would warn them that it does take a little extra time. So, you know, if we are not really busy then we feel like we have the time to do it. But if they’re really busy, letting them know ahead of time that they need to spread out, add ten extra few minutes in when you’re scheduling interviews.” |

| Available Resources | ID_05: We have a couple of new hires, as I mentioned, so we are getting more help to manage everything that needs to be done. ID_07: Now that we’ve got a person on board that mainly does it it’s flowing better. ID_14: We try to make sure that child is in a private comfortable place. We have a small area, and often we have a lot people in that area, so once in a while we have the child either go back to the interview room or into another place where is some privacy and the child can take the survey. |

| Characteristics of Individuals | |

| Self-Efficacy and Comfort with Suicidality | ID_14: There are times that it’s been a little frightening to use when the result comes back and we have to tell a family that there’s some suicidal ideation…That part makes it very difficult for me. ID_06: I just feel like the people giving it need to be more educated…I don’t really feel like I am qualified to give therapy…to the parents if the children rank high in suicide. It’s a good program but it is a lot on my part. |

| Process | |

| Increasing Self-Efficacy | ID_15: It was difficult at first then I got into a really good rhythm. It became second nature and it felt very comfortable. My level of discomfort in talking about suicide definitely decreased. It is something I feel very open and more ready to discuss, armed with resources to help protect those youth in our area and to support them if that’s something they are struggling with. ID_20: The more you do it, the more you see it, the more you study it, get training on it, the more comfortable you are. |

| Ongoing Training | ID_13: We were able to get…the training that we needed. It helped us build our confidence in the staff administering the tool to really help us know that we can do this and that we do have the skills, and acquired more skills, to get even more comfortable and build our confidence. ID_12: I suppose what made it possible is the training we received. ID_05: Over the last couple of months, we have given ourselves the opportunity to get quite a bit of training on suicide and crisis safety planning. You guys have helped us with some of that because we didn’t really know. We felt like we weren’t trained in that. None of us are therapists so we just didn’t really know. We’re feeling more confident now than we were when we started. |

Intervention characteristics.

CAC staff generally had positive views of the CPM-PTS. One participant stated, “I think it’s awesome. We’ve been identifying their symptoms early and they are getting the treatment.” Another highlighted the benefits of sharing objective results with parents. “Most kids here need therapy, and most [parents] won’t take their kids. So, I love having a concrete thing to show them…it’s nice to not have just our opinion.” Some staff reported concerns about the wording, describing it as “too descriptive…it feels clunky.” Some staff reported technological issues that hindered administration at times. Overall, participants described the CPM-PTS as a helpful, easy to use tool that improved outcomes for families.

Outer setting.

External grant funding was a key facilitator in multiple sites. One participant stated, “For sure it was the VOCA [Victims of Crime Act] grant, and the funding for it. …it’s the whole CPM, the whole process altogether, because without the funding, we wouldn’t even be able to do any of this.” Additional facilitators were the availability of mental health services and relationships with mental health providers. In one CAC, staff reported, “We have a lot of onsite therapy and a lot of therapy options where I’m at. If a child does score high or needs some extra help, I feel very comfortable that we can help them find that.”

The fit of the CPM-PTS with families’ needs and capacity was a critical consideration for CAC staff. In general, staff described families as “appreciative” of the CPM-PTS. “I think most families have embraced it, have been grateful to have used the tool, and to have a little glimpse inside of their child.” Another stated, “it helped mom know where/whether to focus her concerns.” Some families, however, felt overwhelmed or were impatient to leave the CAC. “They’re just in information overload. They are already upset that their child was abused…it’s kind of overwhelming to parents.” One participant described a time when “the mom refused to let me talk with her. She just wanted her kids and to go.” Lastly, some CACs served youth living in nearby residential treatment facilities and using the CPM-PTS with these children required inter-agency collaboration that was not yet established. “I have treatment facilities…they refuse [to let] any of their children to take the CPM survey. They say it’s a confidentiality thing.”

Inner setting.

Inner setting determinants were leadership and team support, fit with existing workflows, and available resources. Many staff described strong leadership support for the CPM-PTS. “We have a director that is pretty open-minded and saw that there was a need. … he was very supportive of it.” Some also described support from other members of the multidisciplinary team. One participant stated, “We had great buy-in with our team, they haven’t even second guessed it. The more success we have the more they are sold on it.”

Integrating the CPM-PTS into existing workflows was described as both a facilitator and barrier to implementation. One participant stated, “I think it improves our workflow, and as far as it taking more time, it hasn’t taken us anymore time when they’re here for that initial interview… It just totally integrated really smoothly into what were already doing.” In contrast, another participant described more challenges. “It doesn’t fit into our normal workflow. We had to create a situation for this to work and that has taken some time to get everybody on board. …it’s been difficult to find something that works for everybody.” CAC staff also discussed adjusting their workflow to support integration, for example, by scheduling their forensic interviews and family meetings to allow for more time with families.

The availability of resources within CACs was a key determinant. One participant described having both designated and back-up staff to administer the CPM-PTS.

We have one person designated to actually give the CPM, but we have three others that are able to if that person is not here…It definitely has been easier now that we got the position filled. Now we have someone where this is their specific job.

Space was sometimes a challenge for smaller CACs. “Space…we don’t have a lot of rooms, so it’s sort of hard to say, ‘Okay officers. Get out while we do this’… because there aren’t a whole lot of places for us to go.” Staff described juggling existing rooms to find a place where families could privately complete the screener questions and staff could review responses with the family.

Characteristics of individuals.

The primary theme in this domain was staff self-efficacy and comfort using the CPM-PTS. Many staff without clinical training described feeling under-qualified to screen for and respond to traumatic stress symptoms and suicidality. “I feel like we’re qualified to give the survey, but…if those suicide questions come up and we have to ask those…we’re not trained, you know, in the appropriate words to use or what the next thing to do is.” A clinical staff member described concerns about liability, stating “I think it’s good, it has some benefit. I still am worried about the liability of the kids leaving our center, just because I’m a licensed person.” Training was critical to improving staff comfort and self-efficacy. One participant reported, “We haven’t had great suicide training in the past, so when we have done any suicide training, just going over the material, reassuring it’s okay to talk about, that’s really good.” Training and consultation reassured staff that they can ask and respond effectively.

Process.

CAC staff reported increasing self-efficacy and comfort over time. One participant stated, “We are just still learning…as we learn we are getting more comfortable with it.” Staff ability to implement the CPM-PTS improved as they gained more experience and became more comfortable with the tool. Additional facilitators of CPM-PTS implementation over time included ongoing training and an organizational climate that encouraged learning, specifically recognizing staff’s existing skills and knowledge while welcoming additional training opportunities. One CAC director shared, “I think it would be helpful to have a once-a-year refresher. Let’s make sure we’re filling it out consistently and reading it consistently.”

Mixed Methods Integration

We merged quantitative and qualitative data to provide additional depth of understanding (Table 2). Almost all CACs in the state participated in CPM-PTS training, and most used the CPM-PTS with families in their CAC. Outer and inner setting determinants (external funding, leadership and team support) were most relevant to adoption. External funding was a critical facilitator of adoption. The 2 CACs that did not complete training and the 3 CACs that did not adopt the CPM-PTS after training did not apply for VOCA funding. The remaining CAC without VOCA funding adopted the CPM-PTS but discontinued its use less than a year later. CACs who received funding used it in a variety of ways, including hiring additional CAC staff, creating new positions (e.g., mental health coordinator), and contracting with external mental health therapists. Leadership and team support were also described as facilitators of adoption and continued use.

Table 2.

Mixed Method Results Demonstrating Expansion of Findings

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |

|---|---|---|

| Question | How many CACs adopted the CPM-PTS? | What supports CPM-PTS adoption? |

| Answer | 21/23 (91.3%) CACs completed training, and 18 (78.3%) used the CPM-PTS with families. | External funding was critical to initial adoption. Ongoing consultation and technical assistance supported use after training. Support from leadership and team members facilitated participation in training and use of the CPM-PTS. |

|

| ||

| Question | How many eligible children were screened with the CPM-PTS? | What explains variability in screening rates? |

| Answer | Screening rates ranged from 10% to 100% across CACs. Screening rates were lowest in the quarter immediately after training. |

Integration of the CPM-PTS into workflows and availability of a dedicated staff member facilitated consistent use, while technology problems and space constraints contributed to inconsistent use in some CACs. Some staff felt under-qualified and uncomfortable asking about trauma and suicidality; comfort increased as staff received additional training. |

|

| ||

| Question | Was the CPM-PTS acceptable to caregivers? | How do CAC staff view families’ responses to the CPM-PTS? |

| Answer | Yes, ratings indicate caregivers were comfortable with, learned from, and benefited from the CPM-PTS. | Staff believed the CPM-PTS met families’ needs and was appreciated by most families. Caregivers who felt overwhelmed and legal guardians with confidentiality concerns sometimes refused to complete the screening. |

Quantitative analyses found considerable variability in the proportion of eligible children who received the CPM-PTS across CACs. Qualitative analyses provide additional insight into barriers and facilitators of consistent use. Within the inner setting, facilitators of consistent use included the availability of dedicated staff and integration of the CPM-PTS into workflows, while space constraints were a barrier in some CACs. Individual characteristics, specifically staff discomfort with suicidality, and intervention characteristics, specifically technology problems, were barriers contributing to inconsistent use. Lastly, families’ responses were key outer setting determinants of CPM-PTS use and shaped staff’s views of the CPM-PTS. Quantitative results from caregiver surveys indicate overall high acceptability of the CPM-PTS by caregivers. In some instances, caregivers were reluctant or unwilling to complete the CPM-PTS. However, consistent with the quantitative results, CAC staff reported that most families appreciated the CPM-PTS and found it helpful in understanding their children’s needs.

Discussion

CACs are uniquely positioned to identify children with mental health needs following maltreatment allegations and connect them with effective treatment. The CPM-PTS provides evidence-based screening tools and decision support for frontline staff in CACs to identify and respond to traumatic stress symptoms and suicidality in children. Our evaluation of its statewide implementation informs efforts to improve mental health screening and referral processes in CACs and improve engagement in mental health services for children served by CACs.

We found high rates of CPM-PTS adoption, supported by external funding and leadership support. CACs that received external funding to support their efforts were more likely to successfully adopt the CPM-PTS. Although CACs used the funding in a variety of ways, external funding is likely to directly support adoption by increasing available resources. Funding may also reflect greater interest and motivation for change, advanced planning, and increased accountability, all of which improve the likelihood of successful adoption. Similarly, leaders’ skill and support for grant-writing may relate to their capacity to lead implementation of new practices. Given that all CACs that applied for funding received it, it is difficult to disentangle the effects of receiving funding from factors that drove CACs to apply for funding.

In CACs that adopted the CPM-PTS, there was considerable variation in reach. Across CACs, we found that approximately 50% of eligible children received the screening. This finding is similar to results from another statewide effort; Conners-Burrow and colleagues (2012) found that 46.3% of families were screened for mental health needs across 12 CACs. Our analysis of screening rates within individual CACs shows that examining screening rates across CACs obscures meaningful variation between CACs. One-quarter of CACs (4 of 16) screened more than 75% of eligible children, and 2 of these CACs screened more than 90% of children. In contrast, one CAC screened only 10% of children across 2 years, with quarterly screening rates ranging from 0 to 19%. There was a trend for smaller CACs to have higher screening rates. In addition, there was considerable variability within CACs over time.

Staff identified facilitators and barriers related to intervention characteristics, inner setting, and characteristics of individuals. Although the CPM-PTS was generally viewed positively by CAC staff, some expressed concerns about using technology, fitting the CPM-PTS into their workflow, and discussing suicidality that likely contributed to low screening rates in some CACs. Buy-in and support from leadership and multidisciplinary team members facilitated more consistent use. Themes related to the implementation process included the importance of ongoing training in increasing staff self-efficacy and comfort administering the CPM-PTS.

CAC staff described identifying traumatic stress symptoms and suicidality as critically important for the children they serve and overwhelmingly recommended use of the CPM-PTS to their CAC colleagues. Unsurprisingly, given that the CPM-PTS was administered by staff without clinical training in most CACs (72%), some staff were uncertain or uncomfortable talking about mental health and suicidality with children and parents. This finding is consistent with prior research demonstrating the importance of self-efficacy in implementation (e.g., Lau et al., 2020). Encouragingly, there were no differences in screening rates between CACs with and without clinically trained staff. Staff described training as effective in building their skills and confidence and reported increasing self-efficacy over time. Efforts to implement mental health screening should provide ongoing training and opportunities to learn from others.

Caregivers generally agreed that they felt comfortable completing, or having their child complete, the screener. Similarly, caregivers agreed they learned something from the CPM-PTS and that use of the CPM-PTS helped their understanding of how their child may behave following trauma exposure. Staff described most caregivers as appreciative of the information provided. Acceptability to caregivers and fit with families’ needs is a key outer setting determinant of implementation. Although some caregivers were reportedly unwilling to complete the screening, near universal screening rates in some CACs suggest that caregiver willingness to complete the screening may depend at least in part on how it is presented by staff. Staff reported that their skills in introducing the CPM-PTS to families and communicating its relevance as a tool to guide family decision-making improved over time with training and experience.

It is important to acknowledge the study’s limitations. We are not able to link qualitative findings to implementation outcomes for specific CACs, which limits our ability to explain site-specific outcomes. Our results reflect themes and patterns across CACs and may not accurately describe the experience within specific CACs. We assessed adoption at the CAC level and cannot report how many of the staff trained to administer the CPM-PTS did so. Finally, our understanding of families’ experiences with mental health screening in CACs is limited by our use of qualitative data from staff, and we do not examine the impact of the CPM-PTS on children’s outcomes. Families’ experiences in CACs is an important area for future research.

Overall, our findings suggest that screening for child traumatic stress and suicidality in CACs is valued, acceptable, and feasible. Most CACs adopted and regularly used the CPM-PTS. Both mental health clinicians and staff without clinical training were able to administer the screening tool, provide guidance to families in making important decisions to keep their children safe, and teach basic coping mechanisms to deal with traumatic stress symptoms. Individuals without clinical training play critical roles in CACs and other settings serving at-risk children, and our findings indicate that, given appropriate supports, they are willing and capable of playing a vital role in linking high-risk children to evidence-based trauma-informed practices.

Acknowledgments:

The authors were funded by federal grant monies allocated by the National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative (NCTSI), which is part of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) for their project, Pediatric Integrated Post-Trauma Services (PIPS), to develop a care process model for pediatric traumatic stress (CPM-PTS); Grant Number 1U79SM080000-01. The REDCap platform at the University of Utah is supported by 8UL1TR000105 from the National Institutes of Health. Thank you to participating Children’s Justice Centers and the Utah Office of the Attorney General for their support.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative to Brooks Keeshin, Principal Investigator.

Kara Byrne, Ph.D., M.S.W., is a Senior Research Associate at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute at University of Utah in Salt Lake City, UT. Elizabeth McGuier, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, PA. Kristine Campbell, M.D., M.S.C., is a Professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Child Protection and Family Health of the University of Utah. She provides general pediatric care with University of Utah Health and child abuse pediatrics consultation through the Center for Safe and Health Families. Lindsay D. Shepard, Ph.D., M.S.W., holds a staff position in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah. She is program manager for the Pediatric Integrated Post-Trauma Services project funded by the National Child Traumatic Stress Institute. David Kolko, Ph.D., is a Professor of Psychiatry, Pediatrics, Psychology, and Clinical and Translational Science in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, PA. Brian Thorn is a Clinical Associate Professor at the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah. He is also a clinical psychologist at the Center for Safe and Healthy Families. Brooks Keeshin, M.D., is an Associate Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah. He is a child abuse pediatrician and child psychiatrist. He is also the Principal Investigator of the Pediatric Integrated Post-Trauma Services project, funded by the National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative (Grant Number 1U79SM080000-01).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [University of Utah Institutional Review Board] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Contributor Information

Kara A. Byrne, University of Utah, College of Social Work, Salt Lake City, UT

Elizabeth A. McGuier, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Psychiatry, Pittsburgh, PA

Kristine A. Campbell, University of Utah, Department of Pediatrics, Salt Lake City, UT

Lindsay D. Shepard, University of Utah, Department of Pediatrics, Salt Lake City, UT

David J. Kolko, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Psychiatry, Pittsburgh, PA

Brian Thorn, University of Utah, Department of Pediatrics, Salt Lake City, UT.

Brooks Keeshin, University of Utah, Department of Pediatrics, Salt Lake City, UT.

References

- Bingham AJ, & Witkowsky P (2021). Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. In Vanover C, Mihas P, & Saldana J (Eds.), Analyzing and interpreting qualitative research: After the interview (pp. 133–148). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, & Mannarino AP (2015). Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy for traumatized children and families. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(3), 557–570. 10.1016/j.chc.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners-Burrow NA, Tempel AB, Sigel BA, Church JK, Kramer TL, & Worley KB (2012). The development of a systematic approach to mental health screening in Child Advocacy Centers. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(9), 1675–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Clark VLP (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (Second edition). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose. (2021). Dedoose Version 9.0.17: Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research. SocioCultural Research Consultants. [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist J, Shorey RC, Febres J, Zapor H, Klostermann K, Schratter A, & Stuart GL (2015). A review of Children’s Advocacy Centers’ (CACs) response to cases of child maltreatment in the United States. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 25, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, & Duda SN (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert JL, & Bromfield L (2016). Evidence for the efficacy of the Child Advocacy Center model: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(3), 341–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert JL, & Bromfield L (2017). Better together? A review of evidence for multidisciplinary teams responding to physical and sexual child abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838017697268. 10.1177/1524838017697268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert JL, & Bromfield L (2019). Multi-disciplinary teams responding to child abuse: Common features and assumptions. Children and Youth Services Review, 106, 104467. [Google Scholar]

- Intermountain Healthcare. (2020). Care Process Model: Diagnosis and management of traumatic stress in pediatric patients. https://intermountainhealthcare.org/ckr-ext/Dcmnt?ncid=529796906

- Jackson SL (2004). A USA national survey of program services provided by child advocacy centers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(4), 411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LM, Cross TP, Walsh WA, & Simone M (2007). Do Children’s Advocacy Centers improve families’ experiences of child sexual abuse investigations? Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(10), 1069–1085. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, Lind T, Crawley M, Rodriguez A, Smith A, & Brookman-Frazee L (2020). When do therapists stop using evidence-based practices? Findings from a mixed method study on system-driven implementation of multiple EBPs for children. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(2), 323–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JC, Greist JH, Jefferson JW, Federico MA, Mann JJ, & Posner KL (2013). Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(9), 887–893. 10.4088/JCP.13m08398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Children’s Alliance. (2017). Standards for accredited members. National Children’s Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- National Children’s Alliance. (2019). 2018 NCA Member Census Report—Mental Health Section Only. National Children’s Alliance. [Google Scholar]

- NCTSN Child Welfare Collaborative Group. (2017). Screening for mental health needs in the CAC. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/fact-sheet/cac_screening_for_mental_health_needs_in_the_cac.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, & Landsverk J (2011). Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(1), 44–53. 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, & Mann JJ (2011). The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, & Hensley M (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehnborg SJ, Carpluk W, French V, Lin S, Repp D, Seals C, Shrestha RKC, & Zahid R (2009). Outcome Measurement System: Final report for the Children’s Advocacy Centers of Texas, Inc. The University of Texas at Austin. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, McCarty CA, Richards J, Russo JE, Rockhill C, & Katon W (2010). Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics, 126(6), 1117–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolon-Arroyo B, Oosterhoff B, Layne CM, Steinberg AM, Pynoos RS, & Kaplow JB (2020). The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 Brief Form: A screening tool for trauma-exposed youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(3), 434–443. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu AL & US Preventative Services Task Force. (2016). Screening for depression in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(5), 360–366. 10.7326/M15-2957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Utah Department of Health, Office of Primary Care & Rural Health. (2018). County classifications map. https://ruralhealth.health.utah.gov/portal/county-classifications-map/

- Wissow LS, Brown J, Fothergill KE, Gadomski A, Hacker K, Salmon P, & Zelkowitz R (2013). Universal mental health screening in pediatric primary care: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 1134–1147. e23. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]