Graphical abstract

Keywords: Adsorption, DFT, SERS detection, Pymetrozine, Pesticide residue

Highlights

-

•

SERS signals for different molecule forms of pymetrozine in solution were studied.

-

•

Adsorption behavior of pymetrozine was studied by calculation and experiment.

-

•

Adsorption orientation of different forms of pymetrozine varies with environment.

-

•

SERS method of pymetrozine residues in apple based on Au@AgNPs is established.

Abstract

Pymetrozine is widely used in agriculture to control pests, and its residue may pose a threat to humans. In this study, the adsorption behavior of pymetrozine on Au@AgNPs surfaces in different solutions was investigated by calculation of ACD/Labs, density functional theory, UV–vis spectra, zeta potential and surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Then, a SERS method for detection of pymetrozine residues in apples was established based on the adsorption study. The results showed that pymetrozine was adsorbed on Au@AgNPs surface in different forms in various solutions and high SERS sensitivity of pymetrozine was obtained by the synergistic effect of pymetrozine, Au@AgNPs and NaOH. A simple SERS method has been established to detect pymetrozine in apples with a LOD of 0.038 mg/kg, linear range of 0.05–1.00 mg/kg, recovery of 71.93–117.49 % and RSD low than 11.70 %. This study provides a reference for rapid detection of pymetrozine in agricultural products.

Introduction

Pesticides are important chemicals for improving the yields of agricultural products by controlling pest infestations and diseases in crops. However, it has been reported that less than 0.1 % of applied pesticides are effective in damaging the target pest, while the remaining portion pollutes the environment and food via water, soil, and so on (Arias-Estevez et al., 2008). Thus, the potential risks of food residues and environmental pollution caused by pesticides have caused widespread concern (Pu, Huang, Xu, & Sun, 2021). Pymetrozine is a broad-spectrum insecticide that exhibits high activity against insects by affecting the insects’ feeding behavior, widely combating plant-sucking insects such as the aphid and whitefly in fruits, vegetables, cotton, and field crops (Kang et al., 2018). It is also categorized as a contaminant by the European Union (EU) with an MRL of 0.02–5.00 mg/kg in different samples (European Commission, 2015). Thus, detection and analysis pymetrozine residues in agricultural products and food is necessary to ensure food safety. The conventional analytical methods for pymetrozine detection include liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) and UV–vis spectroscopy (Gao et al., 2016, Jang et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2007, Zhang et al., 2015, Jia et al., 2015, Kang et al., 2018). Although these methods showed good sensitivity for detection of pymetrozine, they still exhibited numerous disadvantages in applications such as laborious sample preparation, a lengthy detection time and expensive laboratory equipment. Thus, developing a simple, rapid and low-cost detection method for trace residues of pymetrozine is essential for food safety and human health.

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is a molecular vibrational spectroscopic technique that can detect trace concentrations of the target analyte to the single-molecule level due to its unique signal enhancement mechanism (Kneipp et al., 1998). It is generally accepted that two enhancement mechanisms including electromagnetic enhancement (EM) and chemical enhancement (CM) operate simultaneously to result in signal enhancement (Seth & Jensen, 2009). The EM mechanism is based on the amplified electromagnetic field generated by the excitation of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of metal nanomaterials (NPs), while the CM mechanism is related to charge transfer between the metal NPs and target molecule (Xie et al., 2020). The EM enhancement mechanism is related to the shape, size, and surrounding environment of metal NPs (Guo et al., 2015). In recent years, the influence of the surrounding environment on SERS performance has also attracted the attention of researchers compared to more detailed reports on shape and size of metal NPs (Wu, Zhang, Huang, Ji, Dai, & Wu, 2020). (Yaseen, Pu, & Sun, 2019) reported that SERS signal of phosalone was easily affected by the solution environment during SERS detection of phosalone residues in peaches, and (Zhang et al., 2018) found that SERS signal of ethion was significantly different in various pH solutions during the process of its residue detection. In addition, (Tzeng & Lin, 2020) reported that the change in SERS signal of adenine was due to the concentrations of H+ and OH− in the test solution altering the coupling mechanism between adenine and silver, and (Yoshimoto, Seki, Okabe, Matsuda, Wu, & Futamata, 2022) further proposed that the variation of adenine was attributed to the disturbance of the acid-base balance of adenine by pH value of the solution. These results indicated that the SERS signal of acid-base equilibrium molecule was more susceptible to the experimental environment.

Pymetrozine ((E)-4,5-dihydro-6-methyl-4-(3-pyridylmethyleneamino)-1,2,4-triazin-3(2H)-one) is a pyridine azomethine compound, which has four pKa values (pKa1 = 12.90, pKa2 = 3.71, pKa3 = 1.82, and pKa4 = −3.92) controlling the relative population of deprotonated, neutral and protonated forms in solution based on the pH value. Recently, multitudinous studies have been reported on the SERS detection of pymetrozine residues, which focused on complex solid SERS substrates and dry-prepared pymetrozine samples (Shen et al., 2021, Xu et al., 2021, Xu et al., 2020). However, few test methods are available for pymetrozine detection by samples with wet preparation, and up to now the adsorption behavior of pymetrozine on SERS substrate surface has not been studied. In our previous study, the pymetrozine signal was significantly changed by adding different cleaning agents to the solution during the sample purification process, but the reason for the unstable SERS signal of pymetrozine has not been further explored (Pan, Guo, Guo, Lu, & Hu, 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to systematically explore the reason for the sensitive SERS signal of pymetrozine with the pH value of solution, which will provide guidance for establishment of a sensitive SERS method for pymetrozine residues detection.

In this research, Au@AgNPs were used as active substrates for detection of pymetrozine residues in apples. In detail, both theoretical calculations and experiments were applied to explore the adsorption of pymetrozine on the surface of Au@AgNPs and its application for residue detection of pymetrozine in apples. First, ACD/Labs was used to predict different molecular forms of pymetrozine adsorbed on Au@AgNPs surface. Then, theoretical Raman spectra of different forms of pymetrozine were calculated by DFT, and SERS selection rule was applied to explore the influence of different types of electrolyte solutions on the orientation of pymetrozine on Au@AgNPs surfaces. Subsequently, adsorption model was simulated based on the SERS intensity of pymetrozine, and adsorption mechanism of pymetrozine on the Au@AgNPs surface was further verified by zeta potential and SERS intensity. Finally, a SERS method was established for detection of pymetrozine residues in apples according to the results of the adsorption study. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic study illustrating the SERS signal of pymetrozine adsorbed on the surface of Au@AgNPs and its application in pymetrozine residues detection. This study provides a reference for improving the sensitivity of the SERS method in the quantitative analysis of acid-base equilibrium target analytes based on colloidal substrates, which promotes the application of SERS method in pesticide residue detection.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Pymetrozine standard (98.5% purity), chloroauric acid (HAuCl4·3H2O), trisodium citrate (Na3C6H5O7, 98%), silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99.9%), ascorbic acid, hydrochloric acid (HCl), nitric acid (HNO3), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), potassium chloride (KCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium hydroxide (KOH), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), anhydrous magnesium sulfate, anhydrous methanol, acetonitrile, and ammonia were purchased from Aladdin Reagent Co., ltd. (Shanghai, China). C18 sorbent cartridges were obtained from Agela Technologies (Tianjin, China). The glass apparatus and magnetic stir bars were soaked in aqua regia [HCl: HNO3 = 3:1 (V/V)] for at least 24 h and washed several times with ultrapure water before use. All of the chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

Preparation and characterization of AuNPs and Au@AgNPs

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were synthesized according to the method described by (Pan, Guo, Lu, & Hu, 2020) with some modifications. Briefly, 60 mL of deionized water and 500 μL of 10 g/L HAuCl4·3H2O were added to a 150 mL round bottom flask under continuous vigorous magnetic stirring at 120 ℃. After boiling for 1 min, 800 μL of trisodium citrate solution (1%, m/v) was quickly dropped into the solution and kept stirring and boiling for 20 min. The mixture changed color from purple to wine-red, indicating the AuNPs were successfully prepared. The synthesized AuNPs were placed in a brown reagent bottle, cooled to room temperature, and stored in a refrigerator at 4 ℃ for further use.

The Au@AgNPs were prepared by a seed-mediated growth method. In detail, 9 mL of the prepared AuNPs seeds and 450 μL of 10 mM ascorbic acid were added to a 25 mL round bottom flask with vigorous stirring for 2 min, then 360 μL of 10 mM AgNO3 solution was added dropwise to the above solution and stirred vigorously at 25 ℃ for 20 min. When the solution changed color from wine-red to orange-yellow Au@AgNPs were successfully prepared.

UV–vis spectra of AuNPs and Au@AgNPs were recorded using a dual-beam UV–vis spectrophotometer (TU-1901, Beijing Purkinje General Instrument Co., ltd., Beijing, China) with a wavelength range of 300–800 nm. The Au@AgNPs and AuNPs colloids were diluted with ultrapure water before measurements. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of Au@AgNPs and AuNPs were acquired from a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1400 Plus, JEOL ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Zeta potential of Au@AgNPs was obtained by a zeta potential distribution analyzer (DelsaNanoZ, Beckman Coulter Co., ltd., Fullerton, California, USA).

Study on the adsorption behavior of pymetrozine on the Au@AgNPs surface

Theoretical method

The pKa values of pymetrozine molecules and the distribution of pymetrozine molecules at various pH were calculated by ACD/Labs PhysChem suite (V6, Advanced Chemistry Development Inc. Toronto, Canada). Gaussian 16 package (Gaussian, Inc. USA) was applied for density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Zhang, Zhou, Jiang, & Li, 2011). The optimal geometries and vibrational frequencies of pymetrozine were calculated by using the B3LYP/6–31++G (d, p) method.

Proportions of pymetrozine forms in different solutions

First, pH values of pymetrozine in different solutions were measured. Subsequently, the forms of pymetrozine adsorbed on Au@AgNPs were predicted based on the ACD/Labs calculation results.

Adsorption orientation of pymetrozine on Au@AgNPs surface

Adsorption orientation of pymetrozine on Au@AgNPs surface in different electrolyte solutions was explored by the results of SERS detection. Briefly, 200 μL of 0.75 mg/L pymetrozine standard solution and 200 μL of Au@AgNPs were added to a 2 mL centrifuge tube and vortexed for 5 s. Then, 10 μL of different electrolyte solution (1 M), including KOH, NaOH, NaNO3, NaCl, KCl, HCl and HNO3 solutions, was added to the tube and vortexed for 20 s each. Finally, the above solution was drawn into a capillary and analyzed by a laser confocal microscopic Raman system (LabRAM HR, Horiba France SAS, Villeneuve, France) equipped with a 633 nm laser and a grating of 600 grooves/mm. The exposure time for each spectrum was 30 s with 2 accumulations. Each sample was measured in five replicates, and the average value was taken for analysis. Two preprocessing methods (baseline correction and denoising) were applied to minimize the interference of fluorescence and improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Detecting pymetrozine standard solutions and evaluation of Au@AgNPs substrate detection performance

Pymetrozine stock solution with a concentration of 100 mg/L was prepared by dissolving pymetrozine standard in anhydrous methanol, and a series of pymetrozine working solutions with concentrations of 0.75, 0.50, 0.25, 0.10, 0.05, and 0.025 mg/L were prepared by diluting the stock solution with anhydrous methanol. Methanol solvent was a blank control. Before measurement, 200 μL of pymetrozine working solution and 200 μL of Au@AgNPs were added to a 2 mL centrifuge tube, and the mixed solution was vortexed for 5 s. Then, 10 μL of NaOH solution (1 M) was finally added to the tube and vortexed for 20 s. The SERS detection conditions were the same as in 2.3.3. Based on the Au@AgNPs substrate, SERS spectra of different solutions were collected and used to evaluate the detection performance of Au@AgNPs. The homogeneity of Au@AgNPs was studied by collecting SERS spectra of pymetrozine solution (1 mg/L) at different locations of capillary, and the reproducibility was evaluated by detecting the same pymetrozine solution (0.5 mg/L) based on the different batches of Au@AgNPs. In addition, the stabilization was investigated by comparison of the SERS signals of pymetrozine (0.5 mg/L) obtained by the freshly prepared Au@AgNPs substrate and the substrate stored in a refrigerator for 1, 5, and 7 days. Besides, the specificity of SERS method for pymetrozine determination was investigated by introducing five interfering pesticides.

Detection of pymetrozine in apple samples

Fresh apples (Malus pumila Mill.) were purchased from a market in Guiyang, Guizhou, China, as real samples to verify the feasibility of the SERS method for detection of pymetrozine residues in fruit samples. 7.5 g of homogenized fresh apple sample was transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube, and 3.8 mL of pymetrozine working solutions with concentrations of 0.10, 0.25, 0.50, 1.00, 1.60, and 2.00 mg/L was added to the tube and vortexed for 1 min. To reduce the influence of the matrix effect, the above samples were extracted and purified according to the QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe) method described by (Lehotay et al., 2010), with some modifications. In detail, 7.5 g of NaCl and 30 mL of ammonia-acetonitrile (30 %, v/v) were added to the centrifuge tube and mixed by an oscillator (SHA-C, Shanghai LNB Instrument Co. ltd, Shanghai, China) for 20 min, then the mixed solution was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 min by a high-speed centrifuge (JW-3024HR, Anhui Jiaven Equipment Industry Co. ltd, Hefei, China). Subsequently, 20 mL of supernatant was transferred to a heart-shaped flask, evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure, and 5 mL of anhydrous methanol was added to dissolve the residue. The dissolved residue was added to a centrifuge tube containing 280 mg of C18 and 310 mg of anhydrous magnesium sulfate for purification. Finally, the mixture was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 min, and 4 mL of the supernatant was passed through a 0.22 μm filter for SERS detection. The SERS detection conditions were the same as in 2.3.3.

For recovery experiment, the contaminated samples with spiked levels of 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mg/kg were obtained by adding pymetrozine working solution (the concentration of 0.25, 0.50, and 1.00 mg/L, respectively) to the homogeneous samples. The extraction, purification and detection processes were described above, and each test was repeated four times for each spiked level.

Data analysis

Langmuir isotherm was used to quantify the observed SERS signal as reported by (Guicheteau et al., 2013), and adsorption curve was expressed by the Langmuir isothermal adsorption formula. Adsorption model was established by fitting the relationship between the SERS intensity and the concentration of pymetrozine according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where I and IMax is the SERS intensity and the maximum SERS intensity, respectively. K is the adsorption constant, and c is the analytical concentration.

All Raman spectra were collected and analyzed using LabSpec 6 software suite (Horiba France SAS, Villeneuve, France). Limit of detection (LOD) was determined based on the following equation.

| (2) |

where S is the standard deviation of the SERS intensity at the characteristic peak and b is the slope of the drawn calibration curve.

Results and discussion

Characterization of AuNPs and Au@AgNPs

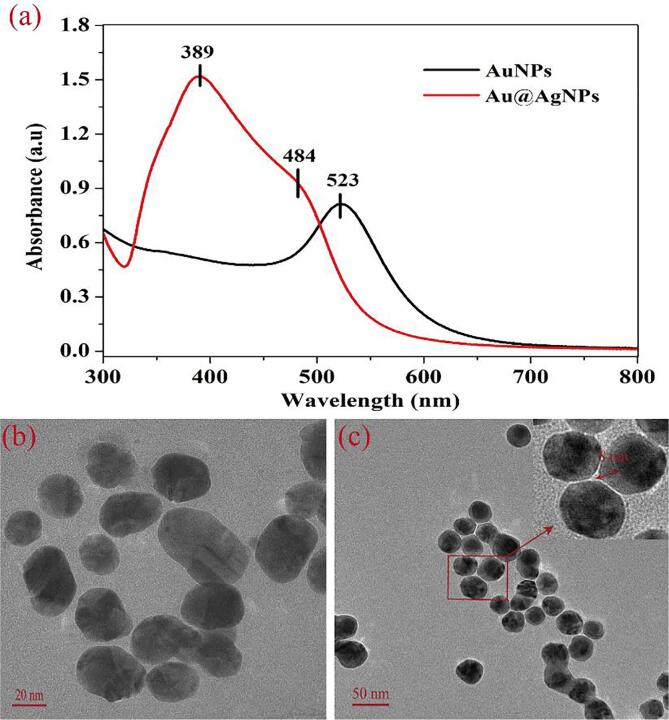

Au@AgNPs were prepared in two steps by a seed-mediated hydrothermal method. Firstly, AuNPs were synthesized and used as a gold-seed solution. Then, AgNO3 was reduced by ascorbic acid on the gold-seed surface, resulting in a silver shell layer being continuously deposited on the gold surface and forming a core–shell structure of Au@AgNPs. The UV–vis spectra of AuNPs and Au@AgNPs were given in Fig. 1a. A narrow band at 523 nm was observed in the spectrum of AuNPs (black) due to the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of AuNPs. In the spectrum of Au@AgNPs (red), two bands were observed at 484 nm and 389 nm, which resulted from the SPR of gold and silver, respectively. TEM images of AuNPs and Au@AgNPs were displayed in Fig. 1b and 1c. It was shown that the average diameter of AuNPs was approximately 30 nm, and Au@AgNPs had a clear color distinction. The dark area of the center was the gold core, and the bright color outside represented the Ag shells with an average thickness of 8 nm. These results were consistent with our previous research (Pan et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

(a) UV–vis spectra and (b and c) TEM images of AuNPs and Au@AgNPs.

Adsorption of pymetrozine on the surface of Au@AgNPs

Forms of pymetrozine molecular at different pH values

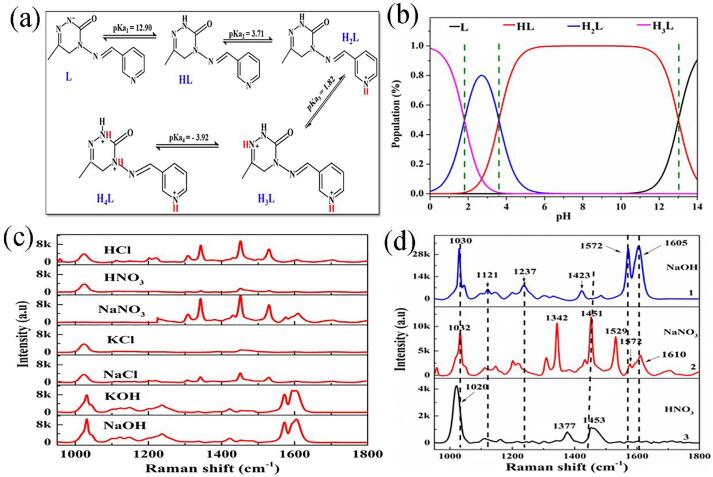

The forms (cationic, neutral and anionic) of pymetrozine molecules and the distribution of different forms at different pH values were shown in Fig. 2a and Fig. 2b. As shown in Fig. 2b, in the pH range of 0–1.8, the forms of pymetrozine existed as H2L (cationic) and H3L (cationic), and when the pH was 1.8, the proportions of H2L and H3L were equal. In the pH range of 1.8–3.6, the proportion of H2L first increased and then decreased, while the proportion of HL (neutral) generally increased. In the pH range of 3.6–6.0, the proportion of HL gradually increased to 100%, while H2L gradually decreased and disappeared. In the pH range of 6.0–11.0, the pymetrozine molecule was present in the form of HL. In the pH range of 11.0–14.0, the proportion of HL gradually decreased, while the proportion of L (anionic) increased monotonically with increasing pH, and the proportions of HL and L were equal at a pH of 13.0. The possible reason for pymetrozine can exist as cation, neutral molecule, and anion in different pH medium solutions is that the N atom in azinone and pyridine structures can gain or lose protons (Chandra, Chowdhury, Ghosh, & Talapatra, 2013).

Fig. 2.

(a) The formulas and (b) distribution of pymetrozine molecules at various pH values, (c) SERS spectra of pymetrozine mixed with HCl, HNO3, NaNO3, NaCl, KCl, KOH and NaOH, and (d) SERS spectra of pymetrozine mixed with NaOH, NaNO3 and HNO3.

The proportions of pymetrozine forms in different solutions were presented in Table S1. As can be observed from Table S1, the pymetrozine molecule existed in the form of HL when the pH value of pymetrozine solution alone was 8.0. However, when pymetrozine was mixed with an equal volume of Au@AgNPs, the pH value of the solution became 4.7, and pymetrozine was present in the forms of HL and H2L. When NaNO3 solution was added to the above-mixed solution, the pH of the mixed solution was 4.6, and pymetrozine still existed in the forms of HL and H2L. The pymetrozine molecule was present in the forms of H2L and H3L in the mixture of pymetrozine, Au@AgNPs and HNO3 (pH = 1.3). In the mixture of pymetrozine, Au@AgNPs and NaOH, pH value was 11.7, and pymetrozine existed as HL and L forms. The results indicate that Au@AgNPs interacted with pymetrozine in neutral and anionic forms in NaOH solution, and in cationic and neutral forms in HNO3 and NaNO3 solutions.

Vibrational mode and adsorption orientation of pymetrozine in different solutions

The calculated theoretical Raman vibrational modes of pymetrozine were listed in Table 1, and the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) of pymetrozine in different forms was given in Fig. S1. The calculated frequencies of the HL form were observed at 1035.09, 1060.74, 1113.15, 1133.36, 1191.67, 1212.39, 1254.86, 1302.27, 1412.57, 1447.96, 1575.64, and 1599.55 cm−1. These calculated frequencies were consistent with the results reported by (Zhang et al., 2011). The peak at 1035.09 and 1060.74 cm−1 was related to the torsion and bending vibration of ring I (pyridyl ring), respectively, and the peaks at 1113.15 and 1133.36 cm−1 were consistent with stretching vibrations of N6N7. The peak at 1191.67 cm−1 corresponded to the bending vibration of ring II (azinone ring), the peak at 1212.39 cm−1 was consistent with CH in-plane bending vibrations of ring I, the peak at 1254.86 cm−1 was assigned to bending vibration of C8C17, the peak at 1412.57 cm−1 belonged to the bending modes of the methyl group, the peak at 1575.64 cm−1 was attributed to stretching vibration of CH in ring II, and the peak at 1599.55 cm−1 was associated with in-plane bending vibrations of N7C8, C9H11 and ring I. The frequencies of pymetrozine with different forms were different but had similar vibrational models, and the vibration models of the remaining three forms were also presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Assignments of calculated and experimental Raman vibrations of pymetrozine.

| Calculated (cm-1) |

Experimental (cm-1) |

Assignments | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3L | H2L | HL | L | Solution of HCl and HNO3 | Solution of NaCl and KCl | Solution of NaNO3 | Solution of NaOH and KOH | |

| 947.22 | 960.91 | / | / | 951.16 | / | / | / | γ C8H25, γ C9H11 |

| / | / | 1035.09 | 1029.63 | / | / | 1028.68 | 1027.55 | τ ring | |

| / | / | 1060.74 | 1056.19 | / | / | / | / | vs ring | |

| 1114.08 | 1116.51 | 1113.15 | 1082.01 | 1106.17 | 1115.13 | 1119.59 | 1120.71 | vs N6N7 |

| / | 1137.30 | 1133.36 | / | 1141.89 | / | / | / | σs N6N7 |

| 1161.11 | / | / | / | 1161.90 | 1154.07 | / | / | δ ring || |

| / | 1199.67 | 1191.67 | 1153.94 | 1195.12 | 1196.10 | 1197.78 | 1198.31 | δ ring || |

| 1208.18 | 1206.02 | 1212.39 | 1202.96 | 1213.87 | 1202.71 | 1236.78 | 1234.58 | δ C12H15, C10H13 |

| / | / | 1254.86 | 1231.64 | / | / | / | / | δ C8C17 |

| 1306.53 | 1305.44 | 1302.27 | / | 1304.07 | 1303.31 | / | / | δ C14H16, δ ring || |

| / | / | 1412.57 | 1405.76 | / | / | 1425.91 | 1423 | δ methyl |

| 1430.79 | 1425.29 | / | / | 1427.51 | / | / | / | δ C8H25, δ C3N6 |

| / | / | 1447.96 | 1437.52 | / | 1448.25 | 1448.26 | 1448.26 | δ ring ||, δ C14H16, δ C10H13 |

| 1482.77 | 1493.78 | / | / | 14934.43 | / | / | / | δ C3H5, δ C1H25 |

| / | / | 1575.64 | 1571.95 | / | / | 1570.34 | 1572.25 | δ ring || |

| / | / | 1599.55 | 1601.37 | / | / | 1606.73 | 1606.55 | δ ring |, vs N7C8 |

| / | 1604.48 | / | / | 1604.14 | / | / | / | δ N7C8, δ C9H11 |

*δ: in-plane bending,v: stretching,γ: out-of-plane bending,τ: torsion, ring: pyridyl ring; ring: nitrogen heterocycle.

SERS surface selection rules can be applied for adsorption orientation analysis (Kaemmer, Olschewski, Roesch, Weber, Cialla-May, & Popp, 2016). Based on SERS selection rule, the vibrational modes of molecules adsorbed perpendicular to the metal NPs surface were more and stronger, and the vibrational modes of molecules adsorbed parallel to the metal surface were less and weaker (Keeler & Russell, 2019). To determine the orientation behavior of pymetrozine absorbed on Au@AgNPs surface, SERS spectra of pymetrozine in seven electrolyte solutions with different pH values were collected (Fig. 2c), and the collected SERS spectra were compared with the four forms of theoretical Raman spectra (Table 1). The results indicated that SERS spectra of pymetrozine in HCl, HNO3, NaCl and KCl solutions were similar, and pymetrozine was adsorbed on Au@AgNPs surface in the H2L form. Likewise, the spectra of pymetrozine in NaNO3, NaOH and KOH were also similar, and pymetrozine was adsorbed on Au@AgNPs surface in the HL form. However, SERS intensity of the same form of pymetrozine was different in different solutions, such as the presence of pymetrozine in the HL form in NaNO3, NaOH and KOH solutions (Fig. 2c). For the vibrational modes of ring I, the peak positions at 1035.09 and 1213.39 cm−1 were redshift and blueshift by approximately 5 and 22 cm−1 compared to the theoretical calculation for HL. For the vibrational modes of ring II, the peak position at 1191.67 and 1570.34 cm−1 was blueshift and redshift by about 7 and 5 cm−1, respectively, compared to the theoretical calculation for HL. In addition, the δCH vibration of ring II was stronger than that of ring I, and the redshift and blueshift of ring II were not obvious in KOH, NaOH and NaNO3 solutions. Thus, variation of the δCH vibration intensity on ring II and the shift of the vibration frequency in ring II indicated that the HL form adsorbed on the Au@AgNPs surface in a perpendicular orientation with ring II, which was consistent with the previous study (Mary et al., 2014a). Moreover, compared with the two alkaline solutions, the SERS intensity of pymetrozine in the NaNO3 solution was weaker (Fig. 2d), which indicated that the HL form adsorbed on Au@AgNPs surface in a sloped manner in the NaNO3 solution (Gamberini, Mary, Mary, Kratky, Vinsova, & Baraldi, 2021). In the remaining four electrolyte solutions (HCl, HNO3, NaCl, and KCl), weak peaks (1199.67 and 1305.44 cm−1) of the ring I vibrational model were observed, and the peaks of the ring II vibrational model were hardly observed (Fig. 2c). In addition, the redshift of the peak position of ring I was less than 5 cm−1 compared with the theoretical calculation. The results indicated that the H2L form was vertically adsorbed on Au@AgNPs surface with ring I in the above four solutions, which were consistent with previous studies (Mary et al., 2014a, Mary et al., 2014b).

Adsorption mechanism of pymetrozine on Au@AgNPs surface

Fig. 3a showed the UV–vis spectra of Au@AgNPs in three solutions. The plasmon resonance peak of the Au@AgNPs was shifted from 392 nm to 394 nm after adding pymetrozine. This shifted plasmon band of Au@AgNPs was attributed to the adsorption of pymetrozine on Au@AgNPs surface. In the NaOH solution, a further shifted absorption (from 392 nm to 402 nm) and a broader bandwidth were observed, which can be explained as a result of the plasmon coupling induced by NaOH (Park, Jin, Park, Guo, Chang, & Jung, 2022). In addition, the role of NaOH during the adsorption was further investigated by changing the mixing order of pymetrozine, Au@AgNPs and NaOH. SERS spectra of the mixed solutions were shown in Fig. 3b. The weak SERS signal of pymetrozine (as shown in Fig. 3b-1) may be attributed to the rapid aggregation of Au@AgNPs and the subsequent formation of aggregates with a small specific surface area, limiting the number of HL form of the pymetrozine molecule on Au@AgNPs surface. The moderate SERS signal in Fig. 3b-2 was caused by competing adsorption of large sterically hindered HL and small sterically hindered OH−. OH− rapidly occupied some adsorption sites on the surface of Au@AgNPs, which reduced the adsorption capacity of pymetrozine (Stewart, Murray, & Bell, 2015). The strongest SERS signal (Fig. 3b-3) was due to pymetrozine molecules in the gap Au@AgNPs losing protons and transforming into HL and L molecules under the action of NaOH (Lu et al., 2019). In other words, the strongest signal originated from the synergistic effect of NaOH, pymetrozine and Au@AgNPs. The adsorption curve of pymetrozine SERS intensity with its concentrations was shown in Fig. 3c, which was further to explain the adsorption of pymetrozine on Au@AgNPs surface. These data fitted well with Langmuir model, indicating that the adsorption procedure of pymetrozine in the HL form on Au@AgNPs matched the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. Thus, the adsorption of pymetrozine on the surface of Au@AgNPs was most likely monolayer adsorption behavior.

Fig. 3.

(a) UV–vis spectra of Au@AgNPs, Au@AgNPs mixed with pymetrozine, and Au@AgNPs mixed with pymetrozine and NaOH, (b) SERS spectra of the mixed solution of Au@AgNPs, pymetrozine and NaOH in different addition orders, (c) Langmuir adsorption curve of pymetrozine on the surface of Au@AgNPs, and (d) zeta potential of different solutions (1: Au@AgNPs; 2: Au@AgNPs mixed with NaOH; 3: Au@AgNPs mixed with pymetrozine; 4: Au@AgNPs mixed with pymetrozine and NaOH).

The monolayer adsorption behavior of pymetrozine was further characterized by zeta potentials of the mixed solutions. As shown in Fig. 3d-1, zeta potential of Au@AgNPs was −31.55 V. For the negatively charged Au@AgNPs, the negative electric charge originates from the adsorbed ascorbate ions (C6H7O6−) and citrate ions (C6H5O73−). Zeta potential of the mixture of Au@AgNPs and NaOH was −30.38 V (Fig. 3d-2), which indicates that the addition of NaOH did not change the electron distribution on Au@AgNPs surface (Gao et al., 2019). Zeta potential of the mixed solution of Au@AgNPs and pymetrozine and the mixture of Au@AgNPs, pymetrozine and NaOH was 3.32 V, and 7.57 V, suggesting that the binding of pymetrozine molecules around Au@AgNPs shifted zeta potential to a positive value (Fathima, Paul, Thirunavukkuarasu, & Thomas, 2020). However, the difference between the above two solutions was because the as-prepared Au@AgNPs surfaces were covered with bulky C6H7O6− and C6H5O73−, which likely sterically hindered the adsorption of pymetrozine (Yajima, Yu, & Futamata, 2011). In the NaOH solution, the positively charged Na+ could induce the aggregation of Au@AgNPs by destroying the double-layer structure of negatively charged Au@AgNPs. At the same time, the electrostatic interaction between pymetrozine and the negatively charged OH− promoted the falling of the HL form on the Au@AgNPs surface and finally formed a monomolecular adsorption layer (Xie et al., 2020). The monolayer adsorption layer complex generates abundant hot spots under laser irradiation and realizes susceptible detection.

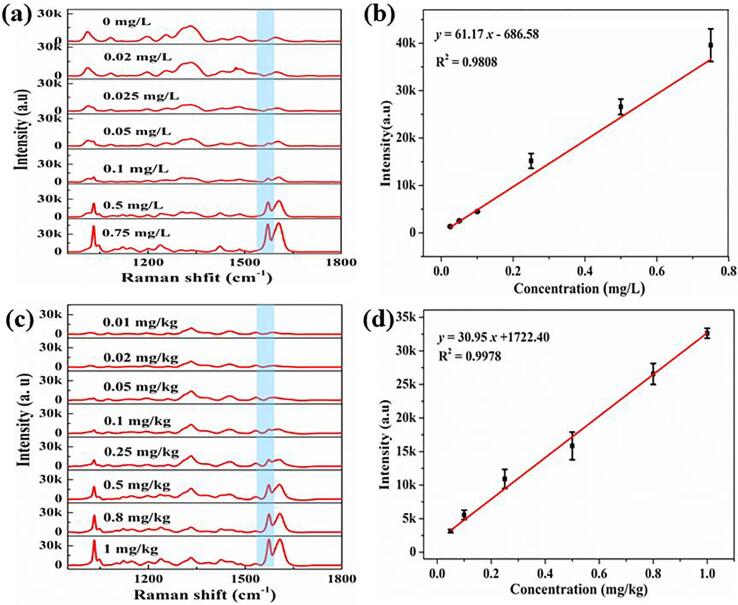

Sensitivity, homogeneity, reproducibility, stabilization and specificity of Au@AgNPs

Pymetrozine was used to evaluate the sensitivity, homogeneity, reproducibility and stabilization of Au@AgNPs. SERS spectra of pymetrozine solution with different concentrations (0, 0.02, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, and 0.75 mg/L) were shown in Fig. 4a, and Fig. 4b showed the calibration curve of concentration-dependent SERS intensity of the peak at 1572 cm−1. The intensity of pymetrozine increased with increasing concentration, and SERS intensity was linearly correlated with the concentration range of 0.025–0.750 mg/L. The linear relationship was , with a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.9808, showing high sensitivity of SERS method for determination of pymetrozine. The homogeneity of Au@AgNPs substrate was investigated by 10 parallel positions in a capillary using Au@AgNPs with the pymetrozine sample solution (1 mg/L) independently, and the results were shown in Fig. S2a. The results indicated Au@AgNPs have good homogeneity with relative standard deviation (RSD) of the peak intensity at 1572 cm−1 was 8.98 %. Five batches of Au@AgNPs were prepared to investigate the reproducibility of Au@AgNPs, a total of five SERS spectra of pymetrozine solution (0.5 mg/L) were collected for each batch, and finally 10 spectra were randomly selected for analysis. Fig. S2b showed the peak intensity distribution of the pymetrozine with RSD of 10.52 %, representing satisfactory repeatability. Moreover, the results of stability experiment were presented in Fig. S2c. It can be observed that SERS intensity of the peak at 1572 cm−1 remained unchanged within 1 day, and the peak intensity decreased to 50 % on the 5th day and 10 % on the 7th day. Thus, Au@AgNPs had good stability for SERS measurements within 1 day, which was consistent with the previous study (Zheng et al., 2014).

Fig. 4.

(a) SERS spectra of pymetrozine standard solutions at different concentrations, (b) the relationship between the SERS intensity at 1572 cm−1 and concentration, (c) SERS spectra of pymetrozine in apple extract, and (d) the relationship between the SERS intensity at 1572 cm−1 and the extract concentration.

To investigate the specificity of the SERS method, Raman spectra of five other interfering pesticides including imidacloprid, acetamiprid, sulfluramid, pyridaben and thiamethoxam were collected under the same condition (shown in Fig. S4a). The concentration of these five pesticides was 10 mg/L, while the concentration of pymetrozine was 1 mg/L. SERS intensity of the peak at 1572 cm−1 was extracted for quantification of pymetrozine, it was also utilized and plotted for interfering assay. Fig. S4b revealed that the peak intensities of all the interfering pesticides were much lower than that of pymetrozine, which indicated that the Au@AgNPs substrates exhibited excellent specificity for sensing pymetrozine.

SERS detection of pymetrozine residues in apples

Apple samples were used to evaluate the feasibility and practicality of the proposed method for analysis of pymetrozine residues. Fig. 4c showed SERS spectra of pymetrozine in apple extract with concentrations in the range of 0.01 mg/kg to 1.00 mg/kg. The relationship between the intensity of the peak at 1572 cm−1 and the concentration of apple extract was presented in Fig. 4d. A good linear relationship can be acquired in the range of 0.05–1.00 mg/kg, and the linear relationship was , with an R2 of 0.9978. The LOD was calculated as 0.038 mg/kg for pymetrozine in the apple extract. The spiked apples were chosen for the recovery test, and the results were presented in Table 2. It can be noticed from Table 2, the recovery range of apples was 71.93–117.49 %, and the average recoveries for the three spiked levels were higher than 78.20 %. Moreover, the RSD of the four replicates for each spiked level was in the range of 4.73–11.70 %. In addition, a comparison of the current method with other methods for the determination of pymetrozine residues in apples was listed in Table S2. Among these mentioned methods, the SERS method based on Au@AgNPs has the advantages of simple steps, short detection time, small solvent consumption, and high sensitivity detection result. Therefore, SERS method based on Au@AgNPs has great potential in the determination of pymetrozine residues in fruit samples.

Table 2.

Detection results of pymetrozine in spiked apple samples.

| Spiked level (mg/kg) | Recovery (%) |

RSD (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | AVG | ||

| 0.10 | 71.93–84.18 | 78.20 | 4.73 |

| 0.25 | 113.09–117.49 | 112.52 | 4.91 |

| 0.50 | 74.73–101.80 | 91.38 | 11.70 |

Conclusions

In this study, different forms of pymetrozine molecule adsorbed on Au@AgNPs surface were first calculated by ACD/Labs and DFT, which was further explored by UV–vis spectrum, Langmuir adsorption model, zeta potential, and SERS spectrum. Then, SERS method for detection of pymetrozine residues in apples was successfully established based on the results of the adsorption study. It was found that the neutral pymetrozine molecule was predominantly adsorbed on Au@AgNPs surface in alkaline solution, and the strongest SERS intensity of pymetrozine was obtained by the synergistic effect of pymetrozine, Au@AgNPs and NaOH. A rapid and sensitive method for detection of pymetrozine residues in apples was established, and the linear range of the method was 0.05–1.00 mg/kg, with a LOD of 0.038 mg/kg. The recovery was in the range of 71.93–117.49 %, with an RSD low than 11.70 %. This study confirmed the ability of SERS platforms to achieve multiple acid-base equilibrium pesticide residue analyses by changing the solution environment, which is expected to provide a reference for SERS detection of pesticides, especially for acid-base equilibrium pesticides.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Meiting Guo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Fang Wang: Visualization, Investigation. Wang Guo: Visualization, Investigation. Run Tian: Visualization, Investigation. Tingtiao Pan: Writing – review & editing. Ping Lu: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the financial support from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M663570), Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Project (ZK [2022] ZD-013 and [2020]4Y100), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (32260695). The authors also thank Dr. Y.J. Ruan for the equipment support and Cloud Computing Platform of Guizhou University.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100487.

Contributor Information

Tingtiao Pan, Email: pantingtiaos@163.com.

Ping Lu, Email: plu@gzu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- Arias-Estevez M., Lopez-Periago E., Martinez-Carballo E., Simal-Gandara J., Mejuto J.C., Garcia-Rio L. The mobility and degradation of pesticides in soils and the pollution of groundwater resources. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2008;123(4):247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S., Chowdhury J., Ghosh M., Talapatra G.B. Exploring the pH dependent SERS spectra of 2-mercaptoimidazole molecule adsorbed on silver nanocolloids in the light of Albrecht's “A” term and Herzberg-Teller charge transfer contribution. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2013;399:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/401. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2015. L 71/114. Available online: https: //eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32015R0401&qid=1610337784804 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Fathima H., Paul L., Thirunavukkuarasu S., Thomas K.G. Mesoporous silica-capped silver nanoparticles for sieving and surface-enhanced Raman scattering-based sensing. Acs Applied Nano Materials. 2020;3(7):6376–6384. [Google Scholar]

- Gamberini M.C., Mary Y.S., Mary Y.S., Kratky M., Vinsova J., Baraldi C. Spectroscopic investigations, concentration dependent SERS, and molecular docking studies of a benzoic acid derivative. Spectrochimica Acta Part a-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2021;248 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2020.119265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M., Li Y., Yang H., Gu Y. Sorption and desorption of pymetrozine on six Chinese soils. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering. 2016;10(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Hu Z., Wu J., Ning Z., Jian J., Zhao T.…Zhou H. Size-tunable Au@Ag nanoparticles for colorimetric and SERS dual-mode sensing of palmatine in traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2019;174:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guicheteau J.A., Farrell M.E., Christesen S.D., Fountain A.W., 3rd, Pellegrino P.M., Emmons E.D.…Emge D. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) evaluation protocol for nanometallic surfaces. Applied Spectroscopy. 2013;67(4):396–403. doi: 10.1366/12-06846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P.Z., Sikdar D., Huang X.Q., Si K.J., Xiong W., Gong S.…Cheng W. Plasmonic core-shell nanoparticles for SERS detection of the pesticide thiram: Size- and shape-dependent Raman enhancement. Nanoscale. 2015;7(7):2862–2869. doi: 10.1039/c4nr06429a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J., Rahman M.M., Ko A.Y., Abd El-Aty A.M., Park J.H., Cho S.K., Shim J.H. A matrix sensitive gas chromatography method for the analysis of pymetrozine in red pepper: Application to dissipation pattern and PHRL. Food Chemistry. 2014;146:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D., Gao J., Wang L., Gao Y., Ye B. Electrochemical behavior of the insecticide pymetrozine at an electrochemically pretreated glassy carbon electrode and its analytical application. Analytical Methods. 2015;7(21):9100–9107. doi: 10.1039/c5ay01987g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaemmer E., Olschewski K., Roesch P., Weber K., Cialla-May D., Popp J. High-throughput screening of measuring conditions for an optimized SERS detection. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 2016;47(9):1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Kang J., Zhang Y., Li X., Dong C., Liu H., Miao L.…Wu A. Rapid and sensitive colorimetric sensing of the insecticide pymetrozine using melamine-modified gold nanoparticles. Analytical Methods. 2018;10(4):417–421. [Google Scholar]

- Kneipp K., Kneipp H., Kartha V., Manoharan R., Deinum G., Itzkan I.…Feld M. Detection and identification of a single DNA base molecule using surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) Physical Review E. 1998;57(6):6281–6284. [Google Scholar]

- Keeler A.J., Russell A.E. Potential dependent orientation of sulfanylbenzonitrile monolayers monitored by SERS. Electrochimica Acta. 2019;305:378–387. [Google Scholar]

- Lehotay S.J., Son K.A., Kwon H., Koesukwiwat U., Fu W., Mastovska K.…Leepipatpiboon N. Comparison of QuEChERS sample preparation methods for the analysis of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables. Journal of Chromatography A. 2010;1217(16):2548–2560. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Cai Z., Zou Y., Wu D., Wang A., Chang J.…Liu G. Silver nanoparticle-based surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for the rapid and selective detection of trace tropane alkaloids in food. ACS Applied Nano Materials. 2019;2(10):6592–6601. [Google Scholar]

- Mary Y.S., Jojo P.J., Van Alsenoy C., Kaur M., Siddegowda M.S., Yathirajan H.S.…Cruz S.M. Vibrational spectroscopic studies (FT-IR, FT-Raman, SERS) and quantum chemical calculations on cyclobenzaprinium salicylate. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2014;120:340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary Y.S., Jojo P.J., Van Alsenoy C., Kaur M., Siddegowda M.S., Yathirajan H.S.…Cruz S.M. Vibrational spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, SERS) and quantum chemical calculations of 3-(10,10-dimethyl-anthracen-9-ylidene)-N, N, N-trimethylpropanaminiium chloride (Melitracenium chloride) Spectrochimica Acta Part A-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2014;120:370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T.T., Guo M.T., Guo W., Lu P., Hu D.Y. A sensitive SERS method for determination of pymetrozine in apple and cabbage based on an easily prepared substrate. Foods. 2021;10(8):1874. doi: 10.3390/foods10081874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T.T., Guo W., Lu P., Hu D. In situ and rapid determination of acetamiprid residue on cabbage leaf using surface enhanced Raman scattering. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2020;101:3595–3604. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E., Jin S., Park Y., Guo S., Chang H., Jung Y.M. Trapping analytes into dynamic hot spots using tyramine-medicated crosslinking chemistry for designing versatile sensor. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2022;607:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu H., Huang Z., Xu F., Sun D.W. Two-dimensional self-assembled Au-Ag core-shell nanorods nanoarray for sensitive detection of thiram in apple using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Food Chemistry. 2021;343 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth M.M., Jensen L. Understanding the molecule-surface chemical coupling in SERS. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131(11):4090–4098. doi: 10.1021/ja809143c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z., Fan Q., Yu Q., Wang R., Wang H., Kong X. Facile detection of carbendazim in food using TLC-SERS on diatomite thin layer chromatography. Spectrochimica Acta Part A-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2021;247 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2020.119037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A., Murray S., Bell S.E.J. Simple preparation of positively charged silver nanoparticles for detection of anions by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Analyst. 2015;140(9):2988–2994. doi: 10.1039/c4an02305f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng Y., Lin B.Y. Silver-based SERS pico-molar adenine sensor. Biosensors-Basel. 2020;10(9):122. doi: 10.3390/bios10090122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Zhang L., Huang F., Ji X., Dai H., Wu W. Surface enhanced Raman scattering substrate for the detection of explosives: Construction strategy and dimensional effect. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2020;387 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Lu J., Liu T., Chen G., Liu G., Ren B., Tian Z. Key role of direct adsorption on SERS sensitivity: Synergistic effect among target, aggregating agent, and surface with Au or Ag colloid as surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy substrate. Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2020;11(3):1022–1029. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b03724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Hassan M.M., Ali S., Li H., Ouyang Q., Chen Q. Self-cleaning-mediated SERS chip coupled chemometric algorithms for detection and photocatalytic degradation of pesticides in food. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2021;69(5):1667–1674. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Kutsanedzie F.Y.H., Hassan M., Zhu J., Ahmad W., Li H., Chen Q. Mesoporous silica supported orderly-spaced gold nanoparticles SERS-based sensor for pesticides detection in food. Food Chemistry. 2020;315 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yajima T., Yu Y., Futamata M. Closely adjacent gold nanoparticles linked by chemisorption of neutral rhodamine 123 molecules providing enormous SERS intensity. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2011;13(27):12454–12462. doi: 10.1039/c1cp00046b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen T., Pu H., Sun D.W. Effects of ions on core-shell bimetallic Au@AgNPs for rapid detection of phosalone residues in peach by SERS. Food Analytical Methods. 2019;12(9):2094–2105. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto T., Seki M., Okabe H., Matsuda N., Wu D.Y., Futamata M. Three distinct adsorbed states of adenine on gold nanoparticles depending on pH in aqueous solutions. Chemical Physics Letters. 2022;786 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Liang P., Yu Z., Huang J., Ni D., Shu H., Dong Q.M. The effect of solvent environment toward optimization of SERS sensors for pesticides detection from chemical enhancement aspects. Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical. 2018;256:721–728. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Cheng X., Wang C., Xi Z., Li Q. Efficient high-performance liquid chromatography with liquid-liquid partition cleanup method for the determination of pymetrozine in tobacco. Annali Di Chimica. 2007;97(5–6):295–301. doi: 10.1002/adic.200790015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang L., Xu P., Li J., Wang H. Dissipation and residue of pymetrozine in rice field ecosystem. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2015;187(3):78. doi: 10.1007/s10661-014-4256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhou H., Jiang Z.J., Li R.Q. Experimental and DFT studies on the vibrational and electronic spectra of 4,5dihydro-6-methyl-4-[(E)-(3-pyridinylmethylene)amino]-1,2,4-triazin-3(2H)-one. Spectrochimica Acta Part A-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2011;83(1):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2011.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Mao H., Zhang L., Jin Y., Zhou Y., Peng Y., Du S. Aminopyrine Raman spectral features characterised by experimental and theoretical methods: Toward rapid SERS detection of synthetic antipyretic-analgesic drug in traditional Chinese medicine. Analytical Methods. 2014;6(15):5925–5933. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.