To the Editor:

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity hypoventilation are highly prevalent in obesity and have no effective pharmacotherapy (1). Leptin is a powerful stimulant of ventilatory control and upper airway patency during sleep (2). Individuals with obesity have high circulating leptin concentrations but are resistant to its beneficial metabolic and respiratory effects. One of the key mechanisms of leptin resistance is the limited permeability of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) to leptin (3). Leptin resistance has been implicated in the pathogenesis of SDB (4).

Mice with diet-induced obesity (DIO) have SDB, similar to patients with obesity (5). SDB in mice can be treated by intranasal leptin delivery, which allows leptin to circumvent the BBB (2). However, this route may not be practical in humans because of differences in the olfactory bulb anatomy between species.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are nanoparticles with an important role in intracellular communication and in a variety of pathophysiological processes (6). Allogenic EVs loaded with polypeptides are a promising strategy for targeted drug delivery to the brain (7, 8), and peripherally administered EVs are effectively distributed throughout the brain (7, 9). Macrophage-derived EVs have low immunogenicity and can target sites of inflammation, improving the BBB penetration for therapeutics (10).

We hypothesize that leptin-loaded EVs will treat SDB in DIO. First, we determined the efficacy of EV delivery to the brain in DIO and control lean mice. Second, we measured the effect of leptin-loaded EVs compared with free leptin and placebo on sleep and breathing in DIO and lean rodents.

All procedures complied with the Guidelines for Animal Studies from the American Physiological Society and were approved by the Johns Hopkins University and the University of North Carolina Animal Use and Care Committees. Methods are described in detail in the data supplement.

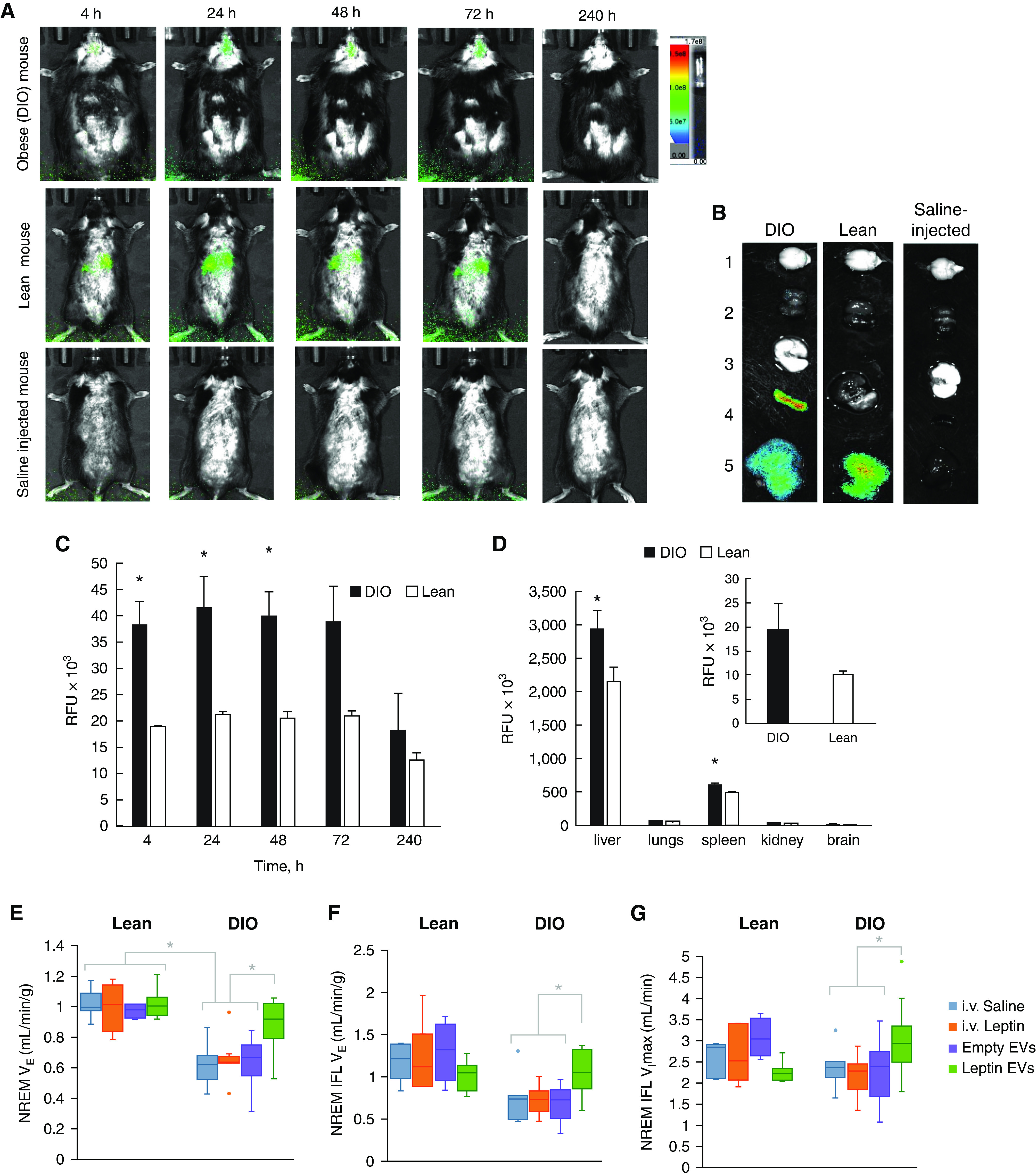

Leptin was loaded into macrophage-derived EVs by probe sonication technique (Table E1 and Figures E1–E4 in the data supplement). EVs were labeled with near-infrared lipophilic fluorescent dye DiR and intravenously administered into the tail vein to DIO and lean mice (Figures 1 and E5). Fluorescent and light images of dorsal planes of the injected animals taken over 10 days showed a significant accumulation of EVs in the brain area, especially in DIO animals at 24–72 hours after injection time (Figure 1A). Quantitative analysis indicated that EVs were retained in the brain of DIO animals at significantly greater concentrations compared with the lean mice (Figures 1C and 1D).

Figure 1.

Biodistribution of DIR-labeled extracellular vesicles (EVs) in diet-induced obesity (DIO) and lean mice by (A–D) in vivo imaging system (IVIS) and (E–G) ventilation during nonrapid eye movement sleep. (A) EVs labeled with fluorescent hydrophobic dye DIR were intravenously injected into mice with DIO or lean mice (2 mo of age, 3 × 1011 particles/200 μl/mouse) and imaged by IVIS for 240 hours. Control lean mice were injected with saline. Prone representative images (n = 4) show a considerable amount of DIR-EVs in the brain of DIO mice, especially at 24–72 hours. (B) At the endpoint, mice were killed, perfused, and main organs (i.e., brain [1], kidney [2], lungs [3], spleen [4], and liver [5]) were imaged by IVIS and quantified using ADL Aura software. (C) Fluorescence intensity in the brain area on IVIS images was assessed for DIO mice (black bars) and lean mice (white bars). Quantitative analysis revealed a considerably greater accumulation of EVs in the brain of DIO mice compared with lean control animals. (D) The high accumulation of EVs was also recorded in peripheral organs; however, DIO animals showed higher retention of EVs in the brain than lean mice (insert). (E) Shows normalized minute ventilation (VE) in nonflow limited breathing; (F) shows normalized VE in inspiratory flow limited breathing (IFL); and (G) shows maximal inspiratory flow (VImax) in IFL breaths. In DIO mice, leptin EVs increased VE in flow-limited and nonflow-limited breaths and improved upper airway function with an increase in VImax during IFL breaths. Leptin EVs restored all parameters to the same concentrations as in lean mice. *P < 0.05. i.v. = intravenous; NREM = nonrapid eye movement; RFU = relative fluorescence units.

We demonstrated earlier that macrophage-derived EVs target inflamed brain tissues (7, 10). The uptake of EVs to the brain is mediated by ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1) in brain endothelial cells that interact with an LFA-1 (lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1) in macrophage EVs (9). More efficient BBB penetration by EVs in DIO mice may be a consequence of brain inflammation associated with obesity and a high-fat diet (11, 12).

Sleep studies were performed in a randomized crossover manner in lean (n = 8) and DIO mice (n = 10) (Figure E6). Mice received saline, leptin, empty EVs, or leptin-loaded EVs intravenously and were placed in plethysmography chambers for recording of sleep, airflow, and respiratory effort from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Inspiratory flow-limited (IFL) and nonflow-limited breathing were scored separately. IFL indicates upper airway obstruction during sleep, similar to human obstructive sleep apnea (5, 11). In contrast, nonflow-limited breathing depends on CO2 concentrations and is determined by CO2 production (i.e., metabolic rate and CO2 sensitivity [control of breathing]).

Lean mice showed higher sleep efficiency and more rapid eye movement (REM) sleep than DIO mice, but no effect of intervention was observed (Table 1). We have previously shown that DIO mice hypoventilate (5), mimicking human obesity hypoventilation syndrome (1), and have IFL during sleep, which is similar to human obstructive sleep apnea. The present study revealed that DIO mice treated with saline, leptin, or empty EVs had depressed nonflow-limited breathing compared with lean mice after the same treatment (P ⩽ 0.001) (Figure 1E). Leptin-loaded EVs induced a 30–40% increase in minute ventilation in obese animals (P < 0.001) to the same concentrations as in lean mice. Leptin-loaded EVs had no effect in lean mice, whereas intravenous leptin had no effect in both groups. In DIO mice, leptin-loaded EVs also augmented IFL breathing (Figures 1F and 1G) and increased minute ventilation and VImax (maximal inspiratory flow) during REM sleep (Figure E7).

Table 1.

General Characteristics of Mice Studied, Sleep Architecture, and Prevalence of Obstructed Breaths

| IV Saline | IV Leptin | Empty EVs | Leptin EVs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (wk) | Lean | 20.5 ± 0.2 | 20.5 ± 0.2 | 20.7 ± 0.2 | 20.5 ± 0.2 |

| DIO | 21.1 ± 0.4 | 20.9 ± 0.3 | 20.6 ± 0.2 | 20.7 ± 0.2 | |

| Weight (g) | Lean | 31.4 ± 0.5 | 31.5 ± 0.5 | 31.2 ± 0.7 | 32.0 ± 0.6 |

| DIO | 41.0 ± 1.2 | 40.3 ± 1.0 | 39.8 ± 0.8 | 41.1 ± 1.1 | |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | Lean* | 61 ± 4 | 70 ± 3 | 71 ± 4 | 68 ± 4 |

| DIO | 54 ± 4 | 48 ± 5 | 65 ± 6 | 55 ± 5 | |

| REM sleep (% of TST) | Lean* | 8 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 |

| DIO | 6 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 | 5 ± 1 | |

| REM sleep bouts, n | Lean | 11 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 | 13 ± 2 | 16 ± 2 |

| DIO | 10 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | 12 ± 3 | 6 ± 1 | |

| Duration REM bouts (min) | Lean | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| DIO | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | |

| NREM sleep (% of TST) | Lean* | 92 ± 1 | 91 ± 1 | 91 ± 1 | 91 ± 1 |

| DIO | 94 ± 1 | 94 ± 1 | 93 ± 1 | 95 ± 1 | |

| NREM sleep bouts, n | Lean* | 36 ± 4 | 44 ± 5 | 31 ± 4 | 37 ± 4 |

| DIO | 58 ± 10 | 48 ± 8 | 71 ± 14 | 55 ± 9 | |

| Duration NREM bouts (min) | Lean | 6 ± 1 | 6 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 7 ± 1 |

| DIO | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | |

| IFL prevalence NREM (%) | Lean* | 5 ± 2 | 7 ± 3 | 5 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 |

| DIO | 9 ± 3 | 10 ± 5 | 13 ± 6 | 4 ± 2 | |

| IFL prevalence REM (%) | Lean | 21 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | 23 ± 3 | 21 ± 3 |

| DIO | 30 ± 6 | 26 ± 4 | 28 ± 4 | 21 ± 3 |

Definition of abbreviations: DIO = diet-induced obesity; EV = extracellular vesicle; IFL = inspiratory flow limitation; IV = intravenous; NREM = nonrapid eye movement; REM = rapid eye movement; TST = total sleep time.

Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Significant difference from DIO condition independent of intervention (P < 0.05).

There was no difference in O2 consumption, CO2 production, or respiratory quotient between groups (Figure E8), suggesting that the differences in ventilation were not influenced by the metabolic rate.

Our data indicate that leptin EVs stimulated both control of breathing and upper airway function. The effects of leptin on the upper airway may be mediated by increased sensitivity to CO2, which is known to increase the activity of hypoglossal motoneurons and the genioglossus muscle, the main upper airway dilator, and by direct stimulation of hypoglossal motoneurons (12). Collectively, our previous and current data suggest that leptin stimulates breathing acting centrally and that stimulatory effects of leptin-loaded EVs on SDB may be related to more efficient penetration of the BBB.

Our study had several limitations. First, the effect of leptin-loaded EVs was reduced during REM sleep, but REM sleep constitutes less than 10% of total sleep time in mice. Second, we tested the efficacy of leptin EVs only in male DIO mice. Third, our study was limited to the acute effects of intravenous leptin EVs, and more studies are necessary to examine the safety and efficacy of chronic treatment with leptin-loaded EVs as well as other more practical routes of administration, such as subcutaneous. Fourth, mechanism(s) of leptin EV penetration of the BBB and biodistribution of leptin in the brain were not examined. Finally, EVs may induce adverse effects. We observed the accumulation of EVs in several organs. Unloaded leptin may increase plasma concentrations of the hormone and induce hypertension (13).

In conclusion, leptin-loaded EVs increase ventilation in our mouse model of SDB. Delivery of leptin and other therapeutics with limited penetration of the BBB with macrophage-derived EVs can be considered for the treatment of SDB and other conditions induced by impaired neural control of breathing.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute grants: NIH/NHLBI R01HL128970 (V.Y.P.), R01HL133100 (V.Y.P.), R01HL138932 (V.Y.P.), R61HL156240 (V.Y.P.), NIDA U18DA052301 (V.Y.P.), NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke 1R01NS112019 (E.V.B.); São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) grant 2018/08758-3 (C.F.); American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award #827943 (C.F.); Eshelman Institute for innovation grant UNC RX03812420 (A.V.K.); and the Carolina Partnership, a strategic partnership between the University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy and The University Cancer Research Fund (A.V.K.).

Author Contributions: C.F.: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, visualization, and writing; J.D.R.: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing; H.P.: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, and validation; R.K.: investigation and methodology; Y.Z.: data curation and investigation; L.K.: formal analysis and investigation; F.A.-D.: investigation and methodology; S.B.: conceptualization and investigation; R.S.A.: methodology, supervision, and writing; E.V.B.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision, visualization, writing-original draft, and writing; A.V.K.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, supervision, and writing; and V.Y.P.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, supervision, and writing.

This letter has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Mokhlesi B. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a state-of-the-art review. Respir Care . 2010;55:1347–1362, discussion 1363–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berger S, Pho H, Fleury-Curado T, Bevans-Fonti S, Younas H, Shin M-K, et al. Intranasal leptin relieves sleep-disordered breathing in mice with diet-induced obesity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;199:773–783. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201805-0879OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banks WA, DiPalma CR, Farrell CL. Impaired transport of leptin across the blood-brain barrier in obesity. Peptides . 1999;20:1341–1345. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berger S, Polotsky VY. Leptin and leptin resistance in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea: a possible link to oxidative stress and cardiovascular complications. Oxid Med Cell Longev . 2018;2018:5137947–5137947. doi: 10.1155/2018/5137947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fleury Curado T, Pho H, Berger S, Caballero-Eraso C, Shin M-K, Sennes LU, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in C57BL/6J mice with diet-induced obesity. Sleep (Basel) . 2018;41:zsy089. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herrmann IK, Wood MJA, Fuhrmann G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat Nanotechnol . 2021;16:748–759. doi: 10.1038/s41565-021-00931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haney MJ, Klyachko NL, Zhao Y, Gupta R, Plotnikova EG, He Z, et al. Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for Parkinson’s disease therapy. J Control Release . 2015;207:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim MS, Haney MJ, Zhao Y, Yuan D, Deygen I, Klyachko NL, et al. Engineering macrophage-derived exosomes for targeted paclitaxel delivery to pulmonary metastases: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Nanomedicine (Lond) . 2018;14:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haney MJ, Klyachko NL, Harrison EB, Zhao Y, Kabanov AV, Batrakova EV. TPP1 delivery to lysosomes with extracellular vesicles and their enhanced brain distribution in the animal model of batten disease. Adv Healthc Mater . 2019;8:e1801271. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yuan D, Zhao Y, Banks WA, Bullock KM, Haney M, Batrakova E, et al. Macrophage exosomes as natural nanocarriers for protein delivery to inflamed brain. Biomaterials . 2017;142:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Condos R, Norman RG, Krishnasamy I, Peduzzi N, Goldring RM, Rapoport DM. Flow limitation as a noninvasive assessment of residual upper-airway resistance during continuous positive airway pressure therapy of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 1994;150:475–480. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.2.8049832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freire C, Pho H, Kim LJ, Wang X, Dyavanapalli J, Streeter SR, et al. Intranasal leptin prevents opioid-induced sleep-disordered breathing in obese mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2020;63:502–509. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0117OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shin MK, Eraso CC, Mu Y-P, Gu C, Yeung BHY, Kim LJ, et al. Leptin induces hypertension acting on transient receptor potential melastatin 7 channel in the carotid body. Circ Res . 2019;125:989–1002. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.315338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]