Abstract

Background

Absorb bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS)-related events have been reported between 1 and 3 years - the period of active scaffold bioresorption. Data on the performance of the Absorb BVS in daily clinical practice beyond this time point are scarce.

Aims

This report aimed to provide the final five-year clinical follow-up of the Absorb BVS in comparison with the XIENCE everolimus-eluting stent (EES). In addition, we evaluated the effect of prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) administration on events in the scaffold group.

Methods

AIDA was a multicentre, investigator-initiated, non-inferiority trial, in which 1,845 unselected patients with coronary artery disease were randomly assigned to either the Absorb BVS (n=924) or the XIENCE EES (n=921). Target vessel failure (TVF), a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction or target vessel revascularisation, was the primary endpoint. Scaffold thrombosis cases were matched with controls and tested for the effect of prolonged DAPT.

Results

Up to five-year follow-up, there was no difference in TVF between the Absorb BVS (17.7%) and the XIENCE EES (16.1%) (hazard ratio [HR] 1.31, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.90-1.41; p=0.302). Definite or probable device thrombosis (DT) occurred in 43 patients (4.8%) in the scaffold group compared to 13 patients (1.5%) in the stent group (HR 3.32, 95% CI: 1.78-6.17; p<0.001). DT between 3 and 4 years occurred six times in the Absorb arm versus three times in the XIENCE arm. Between 4 and 5 years, the incidence was three versus two, respectively. Of those three DT in the scaffold group, two occurred in XIENCE EES-treated lesions. The odds ratio of scaffold thrombosis in patients on DAPT compared to off DAPT throughout five-year follow-up was 0.36 (95% CI: 0.15-0.86).

Conclusions

The excess risk of the Absorb BVS on late adverse events, in particular device thrombosis, in routine PCI continues up to 4 years and seems to plateau afterwards. Clinical Trial Registration ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01858077.

Introduction

Drug-eluting stents have an ongoing risk of device-related adverse events long after implantation1. The pathogenesis of this ongoing annual hazard is thought to be the permanent presence of a metallic implant. To liberate the coronary artery from its permanent metallic cage, and therefore remove the potential cause of restenosis and stent thrombosis, bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) were developed. Theoretically, the function of the BVS is to scaffold the arterial wall after balloon dilatation to prevent acute vessel closure and late constrictive remodelling. Afterwards, it should dissolve over approximately three years to restore the native structure of the coronary artery. The most widely studied coronary scaffold is the Absorb BVS (Abbott Vascular), which, in a porcine model, completely resorbs and integrates in approximately three years2. However, in clinical practice, the Absorb BVS was found to be associated with an increased risk of target vessel myocardial infarction (TV-MI) and device thrombosis (DT) during the time of reabsorption compared to the everolimus-eluting metallic XIENCE stent (Abbott Vascular)3,4,5. Beyond the three-year time-point, data on the safety and efficacy of the Absorb BVS are scarce6. In addition, it is unknown whether prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) benefits patients treated with the Absorb BVS. Therefore, long-term outcomes are of interest. The Amsterdam Investigator-initiateD Absorb strategy (AIDA) randomised clinical trial compared the Absorb BVS with the everolimus-eluting metallic XIENCE EES stent (Abbott Vascular) in daily clinical practice7. We report the final five-year clinical outcomes of the Absorb BVS in comparison with the XIENCE EES. In addition, we evaluate whether prolonged DAPT regimes mitigate the occurrence of scaffold thrombosis (ScT).

Methods

The study design, endpoint definitions, and results up to three years have been described in detail previously3,7,8,9. Briefly, the AIDA trial was an all-comer, multicentre, investigator-initiated, randomised controlled trial. Between August 2013 and December 2015, 1,845 consecutive patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of one or more target lesions suitable for drug-eluting stent implantation were enrolled. Follow-up was performed at regular intervals up to five years. Quantitative coronary angiographic analyses were performed at a core laboratory. An independent clinical events committee adjudicated all major adverse cardiac events (MACE) according to either the Third Universal Myocardial Infarction definitions10, or the Academic Research Consortium definitions11. The primary study endpoint was target vessel failure (TVF), powered for non-inferiority at two years. TVF is a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (TV-MI), or target vessel revascularisation. Secondary endpoints included TVF, its components, and DT at each follow-up period.

The protocol mandated use of DAPT for at least one year post-PCI. In January 2017, the data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) noted a higher rate of early and late ScT and recommended considering prolonged DAPT in all patients treated with the Absorb BVS. Subsequently, this recommendation was implemented and referring cardiologists were advised to prescribe DAPT up to three years in all patients treated with the Absorb BVS.

The study design was in concordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research ethics committee of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam, approved the study protocol for all participating centres. All enrolled patients provided written informed consent.

Effect of DAPT

To assess the effect of DAPT on the occurrence of ScT, every case with definite ScT was matched with one or two control case(s) based on age, sex, presentation with acute coronary syndrome, total number of stents, total stent length and enrolment date before 1 October 2014. At the time of ScT, use of DAPT was recorded as yes or no for the cases and their controls.

Statistical analysis

The current paper reports the prespecified major outcomes at five-year follow-up. All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Time-to-event curves were constructed by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with log-rank test. Hazard ratios were calculated using Cox regression. Landmark analyses were performed at three and four years after the index procedure. All ScT cases were matched fuzzy (1:2). Fuzz of 10 for age, 14 for days, 0.8 for total number of stents and 19 for total stent length were allowed. The effect of DAPT on the occurrence of ScT was assessed by calculating the odds ratio, using multivariable logistic regression adjusting for age, total number of stents and total stent length. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, Version 26.0 (IBM Corp.).

Results

From August 2013 until December 2015, 1,845 patients were enrolled at five sites throughout the Netherlands. In total, 924 patients were randomised to the Absorb BVS and 921 patients were randomised to the XIENCE EES. Baseline patient, procedural and lesion characteristics have been described in detail in previous reports1,5, and are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2. Briefly, baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups. A total of 54% of patients presented with acute coronary syndrome at baseline; 25.2% ST-segment myocardial infarction, 20.4% non-ST-segment myocardial infarction, and 8.5% unstable angina. SYNTAX score was available for 1,661 patients (90.0%), with a median of 11 (IQR 7-18). In total, 2,446 lesions were treated.

Clinical endpoints

Complete five-year follow-up was obtained in 95.1% of patients. A study flow chart is provided in Supplementary Figure 1. Clinical outcomes up to five-year follow-up are shown in Table 1. Throughout five years, no significant difference in the rate of TVF was found between patients treated with the Absorb BVS (17.7%) versus the XIENCE EES (16.1%) (HR 1.13, 95% CI: 0.90-1.41; p=0.302) (Central illustration). The rates of TV-MI and target lesions revascularisation (TLR) remained significantly higher in the Absorb arm compared to the XIENCE arm, with five-year follow-up rates of TV-MI of 7.7% versus 5.0% (HR 1.57, 95% CI: 1.08-2.30; p=0.018) and TLR 10.1% versus 7.3% (HR 1.41, 95% CI: 1.02-1.94; p=0.034), respectively.

Table 1. Clinical outcomes up to 5-year follow-up.

| At 5 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorb BVS (n=924) | XIENCE EES (n=921) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value¶ | |

| All-cause death | 76 (8.4%) | 88 (9.8%) | 0.85 (0.63-1.16) | 0.314 |

| Cardiac death | 34 (3.8%) | 41 (4.7%) | 0.82 (0.52-1.29) | 0.396 |

| Cardiovascular death | 43 (4.8%) | 47 (5.4%) | 0.91 (0.60-1.37) | 0.641 |

| All myocardial infarction | 96 (10.7%) | 62 (7.1%) | 1.56 (1.13-2.15) | 0.006 |

| Target vessel MI | 69 (7.7%) | 44 (5.0%) | 1.57 (1.08-2.30) | 0.018 |

| Non-target vessel MI | 27 (3.1%) | 19 (2.2%) | 1.41 (0.79-2.54) | 0.246 |

| Any revascularisation | 179 (20.1%) | 152 (17.3%) | 1.18 (0.95-1.47) | 0.127 |

| Target vessel revascularisation | 119 (13.4%) | 94 (10.7%) | 1.27 (0.97-1.66) | 0.084 |

| Target lesion revascularisation | 90 (10.1%) | 64 (7.3%) | 1.41 (1.02-1.94) | 0.034 |

| Device thrombosis related | 37 (4.1%) | 9 (1.0%) | 4.12 (1.99-8.54) | <0.001 |

| Device stenosis related | 58 (6.6%) | 56 (6.4%) | 1.02 (0.71-1.48) | 0.896 |

| Composite endpoints | ||||

| Target vessel failure | 160 (17.7%) | 143 (16.1%) | 1.13 (0.90-1.41) | 0.302 |

| Target lesion failure§ | 135 (14.9%) | 121 (13.7%) | 1.12 (0.88-1.43) | 0.356 |

| Patient-oriented composite endpoint‡ | 259 (28.4%) | 241 (26.6%) | 1.09 (0.91-1.29) | 0.351 |

| ¶p-values were calculated by the log-rank test. §Composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction and target lesion revascularisation. ‡Composite of death, myocardial infarction or any revascularisation. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; MI: myocardial infarction | ||||

Central illustration. Kaplan-Meier curves for target vessel failure up to five-year follow-up per study arm.

Landmark analyses of clinical outcomes between 3- and 4-year, and 4- and 5-year follow-up are shown in Table 2. Clinical outcomes at four-year follow-up are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Between 3 and 4 years, the rates of TV-MI were numerically higher in the Absorb BVS compared to the XIENCE EES, 1.1% versus 0.4%, respectively (HR 3.01, 95% CI: 0.82-5.76; p=0.082). The rates of TLR were significantly higher in the Absorb BVS arm compared to the XIENCE EES arm, 1.6% versus 0.5%, respectively (HR 3.27, 95% CI: 1.07-10.02; p=0.028). This difference was mainly driven by TLR due to restenosis, 1.4% versus 0.4%, respectively (HR 3.61, 95% CI: 1.01-12.93; p=0.035).

Table 2. Landmark analysis for clinical outcomes between 3- and 5-year follow-up.

| Between 3 and 4 years | Between 4 and 5 years | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorb BVS (n=924) | XIENCE EES (n=921) |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

p-value¶ | Absorb BVS (n=924) | XIENCE EES (n=921) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value¶ | |

| All-cause death | 14 (1.6%) | 18 (2.1%) | 0.77 (0.38-1.54) | 0.453 | 16 (2.0%) | 17 (2.2%) | 0.93 (0.47-1.83) | 0.828 |

| Cardiac death | 4 (0.5%) | 7 (0.8%) | 0.56 (0.16-1.92) | 0.354 | 6 (0.7%) | 8 (1.1%) | 0.74 (0.26-2.13) | 0.574 |

| Cardiovascular death | 5 (0.6%) | 9 (1.1%) | 0.55 (0.18-1.64) | 0.274 | 9 (1.1%) | 10 (1.3%) | 0.89 (0.36-2.18) | 0.793 |

| All myocardial infarction | 13 (1.6%) | 6 (0.8%) | 2.19 (0.83-5.76) | 0.103 | 8 (1.1%) | 7 (0.9%) | 1.15 (0.42-3.18) | 0.780 |

| Target vessel MI | 9 (1.1%) | 3 (0.4%) | 3.01 (0.82-11.13) | 0.082 | 5 (0.7%) | 6 (0.8%) | 0.83 (0.25-2.73) | 0.763 |

| Non-target vessel MI | 3 (0.4%) | 3 (0.4%) | 0.99 (0.20-4.91) | 0.991 | 3 (0.4%) | 2 (0.3%) | 1.49 (0.25-8.90) | 0.661 |

| Any revascularisation | 26 (3.6%) | 14 (1.9%) | 1.88 (0.98-3.60) | 0.053 | 13 (2.0%) | 18 (2.7%) | 0.74 (0.36-1.50) | 0.399 |

| Target vessel revascularisation | 20 (2.6%) | 5 (0.7%) | 4.01 (1.50-10.68) | 0.003 | 9 (1.3%) | 12 (1.7%) | 0.76 (0.32-1.80) | 0.526 |

| Target lesion revascularisation | 13 (1.6%) | 4 (0.5%) | 3.27 (1.07-10.02) | 0.028 | 6 (0.8%) | 8 (1.1%) | 0.75 (0.26-2.18) | 0.602 |

| Device thrombosis related | 5 (0.6%) | 2 (0.2%) | 2.51 (0.49-12.96) | 0.254 | 3 (0.4%) | 2 (0.3%) | 1.51 (0.25-9.02) | 0.651 |

| Device stenosis related | 11 (1.4%) | 3 (0.4%) | 3.61 (1.01-12.93) | 0.035 | 4 (0.5%) | 6 (0.8%) | 0.66 (0.19-2.33) | 0.514 |

| Composite endpoints | ||||||||

| Target vessel failure | 22 (2.9%) | 12 (1.6%) | 1.85 (0.91-3.73) | 0.082 | 13 (1.8%) | 21 (3.0%) | 0.63 (0.31-1.25) | 0.181 |

| Target lesion failure§ | 16 (2.1%) | 11 (1.4%) | 1.47 (0.68-3.16) | 0.324 | 10 (1.4%) | 18 (2.5%) | 0.56 (0.26-1.21) | 0.136 |

| Patient-oriented composite endpoint‡ | 35 (4.9%) | 30 (4.2%) | 1.19 (0.73-1.94) | 0.481 | 26 (4.0%) | 33 (5.0%) | 0.81 (0.48-1.35) | 0.415 |

| ¶p-values were calculated by the log-rank test. §Composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction and target lesion revascularisation. ‡Composite of death, myocardial infarction or any revascularisation. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; EES: everolimus-eluting stent; MI: myocardial infarction | ||||||||

In contrast, between 4 and 5 years, the rates of TV-MI did not differ between the Absorb BVS (0.7%) and the XIENCE EES (0.8%) arms (HR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.25-2.73; p=0.763). Also, the incidence of TLR did not differ between the Absorb BVS and the XIENCE EES arms, 0.8% versus 1.1%, respectively (HR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.26-9.02; p=0.602).

Device thrombosis

DT rates are shown in Table 3. At five years, 38 Absorb BVS-treated patients suffered from definite DT compared to 9 XIENCE EES-treated patients (HR 4.24, 95% CI: 2.05-8.77; p<0.001). Descriptive characteristics of the definite DT cases throughout the five-year follow-up period are presented in Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Table 5. The rate of definite/probable DT was significantly increased in the Absorb BVS arm compared with the XIENCE EES arm, with a five-year rate of 4.8% (43 cases) versus 1.5% (13 cases), respectively (HR 3.32, 95% CI: 1.78-6.17; p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 3. Incidence of device thrombosis up to 5-year follow-up.

| Absorb BVS (n=924) | XIENCE EES (n=921) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value¶ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definite | 38 (4.3%) | 9 (1.0%) | 4.24 (2.05-8.77) | <0.001 |

| Probable | 5 (0.5%) | 4 (0.5%) | 1.24 (0.33-4.62) | 0.747 |

| Possible | 16 (1.8%) | 25 (3.0%) | 0.63 (0.34-1.18) | 0.150 |

| Definite/probable | 43 (4.8%) | 13 (1.5%) | 3.32 (1.78-6.17) | <0.001 |

| ≤24 hours (acute) | 3 | 3 | ||

| >24 hours to 30 days (subacute) | 10 | 2 | ||

| 31 days to 1 year (late) | 8 | 1 | ||

| 1-2 years (very late) | 9 | 2 | ||

| 2-3 years (very late) | 4 | 0 | ||

| 3-4 years (very late) | 6 | 3 | ||

| 4-5 years (very late) | 3 | 2 | ||

| Any device thrombosis | 58 (6.5%) | 38 (4.4%) | 1.53 (1.02-2.31) | 0.039 |

| ¶p-values were calculated by the log-rank test. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; EES: everolimus-eluting stent | ||||

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves for definite/probable device thrombosis up to five-year follow-up per study arm.

Between 3 and 4 years, 5 definite DT and 1 probable DT were noted in the Absorb BVS arm compared to 3 definite DT in the XIENCE EES arm. Of the 5 definite ScT cases, 1 case was treated with a two-stent technique in a bifurcation lesion and the DT occurred at 1,277 days post index PCI. The second very late scaffold thrombosis (VLST) was described as thrombosis on severe restenosis by the clinical events committee. The other 3 VLST cases had target lesion revascularisation with a drug-eluting stent (DES) prior to the occurrence of DT. Between 4 and 5 years, 3 definite DT in the Absorb arm versus two in the XIENCE arm were noted. Two of these 3 DT cases were randomised at baseline to the Absorb BVS arm but were treated with the XIENCE EES during the index procedure. Temporal patterns of DT are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Temporal patterns of device failure in BVS treated lesions.

The upper panel depicts a pattern of early scaffold thrombosis, procedure-related edge dissection (A). Malapposition and DAPT cessation patterns are not visualised. The lower panel depicts patterns observed in very late scaffold thrombosis in the same patient, scaffold discontinuation (B) and acquired malapposition (C).

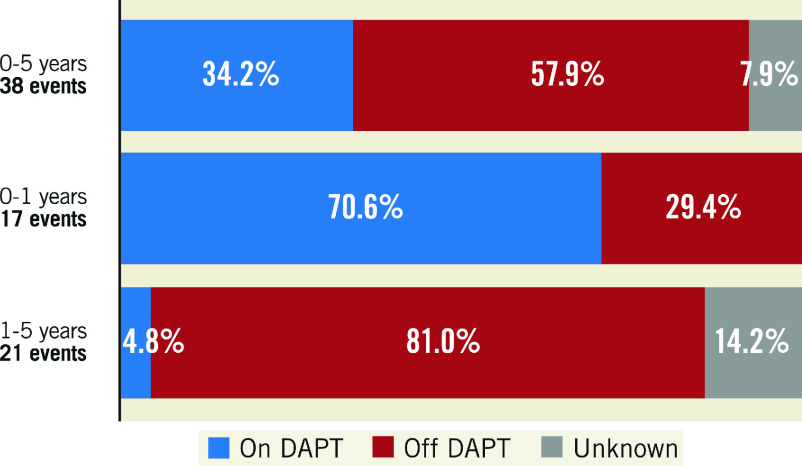

Effect of DAPT on scaffold thrombosis

During five-year follow-up, 21 very late definite scaffold thrombosis occurred in the Absorb arm. Only 1 of these 21 VLST (4.8%) was on DAPT at the time of the event. This is in stark contrast to early DT, where 12 of the 17 patients (70.6%) used DAPT at the time of the event (Figure 3). Patients were advised to prolong DAPT up to three years. Supplementary Figure 2 shows data on aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitors, direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) and DAPT use at all follow-up points. All VLST between 3 and 4 years occurred in patients without use of DAPT regimens. These patients discontinued DAPT 331 days (range 119-632) prior to the event. Detailed information on DAPT status at the time of ScT can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 3. Relationship between definite device thrombosis and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) status at the time of the event during five-year follow-up.

To make the effect of DAPT more transparent, the definite ScT cases were matched with control cases. Four of 38 ScT cases were not eligible; in 2 ScT cases the SYNTAX score was not available and DAPT status was unknown in another 2 ScT cases. DAPT status was also missing in 3 matched controls. Therefore, 34 ScT cases with 65 matched controls were included for analysis. Of those who suffered ScT, 13 patients were on DAPT and 21 patients off DAPT. Of those who did not develop ScT, 41 used DAPT and 24 did not. The odds ratio of ScT with the use of DAPT throughout five-year follow-up was 0.36 (95% CI: 0.15-0.86). Within the first year, the OR of ScT was 0.14 (95% CI: 0.02-0.85) and between 1- and 5-year follow-up the OR was 0.17 (95% CI: 0.02-1.63) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of DAPT on occurrence of scaffold thrombosis.

Discussion

The main findings of this final five-year report on clinical outcomes of the Absorb BVS in comparison with the XIENCE EES from the AIDA trial are as follows: 1) the Absorb BVS was associated with a significantly increased risk of target vessel myocardial infarction and DT compared to the XIENCE EES as tested in daily clinical practice; 2) landmark analysis has shown a plateauing of this excess risk with the Absorb BVS starting at four years; and 3) retrospective analysis indicates a reduced odds ratio of ScT in patients using a DAPT regimen.

The excess risk of Absorb BVS thrombosis

Randomised clinical trials comparing the Absorb BVS with the XIENCE EES have identified an increased risk with the Absorb BVS on TV-MI and DT up to three years after implantation. In a pooled analysis of the Absorb trials, Stone et al12 demonstrated that this excess risk with the Absorb BVS was no longer apparent beyond three years. Compared to the first three years, the hazard ratios of target lesion failure dropped from 1.42 to 0.92, and the hazard ratio of DT dropped from 3.86 to 0.44 between 3 and 5 years12. Our results, however, show a continued excess risk up to four years. Between 3 and 4 years, the hazard ratio of target lesion failure increased from 1.133 to 1.22 at four years, and the increased risk of DT diminished but did not disappear (HR dropped from 6.023 to 2.52). It was only after four years that the excess risk with the Absorb BVS was no longer apparent. The hazard ratio of target lesion failure dropped to 0.56, and for DT it dropped to 1.51. However, 2 of the 3 DT cases between 4 and 5 years occurred in XIENCE EES-treated lesions instead of the randomised device scaffold. Therefore, the hazard ratio is overestimated.

The difference in outcomes between the ABSORB trials and AIDA might be partly explained by the difference in study populations. The study populations of the ABSORB trials mainly consisted of patients with simple lesions and low risk of restenosis. In comparison, the AIDA trial represented daily clinical practice and included patients with complex lesions and patients who had presented with acute coronary syndrome, including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. It might be that the resorption of the Absorb BVS is prolonged in these complex and severely diseased lesions, thereby creating a longer lasting risk of device-related events13. A better understanding of this resorption process and the factors that influence it could help us to improve next-generation bioresorbable scaffold (BRS) devices.

Effect of DAPT

Device thrombosis is a serious complication with high morbidity and mortality14. DAPT significantly reduces the risk of stent thrombosis in DES15,16. The introduction of bioresorbable scaffolds led to the question on whether current DAPT recommendations after DES implantation are also applicable to this different technology. A prolonged ischaemic risk period could be expected due to its larger footprint (strut thickness 157 μm) compared with contemporary second-generation DES (60 to 90 μm), which may lead to greater platelet activation and delayed endothelialisation17,18. In addition, intraluminal dismantling of the Absorb BVS at sites without complete endothelialisation during the resorption process has been suggested as a new mechanism of DT19. Well-apposed and embedded struts at baseline can still protrude into the lumen later on during the reabsorption process20. It is also plausible that good apposition at baseline would not prevent the occurrence of acquired malapposition, as large plaque burden continues to exert an inner force on the progressively weaker resorbing device. Therefore, a cause of ScT may occur at any time during the reabsorption process, rather than being present continuously and cause thrombosis after DAPT discontinuation.

Our results demonstrated an increased ischaemic risk period of four years with the Absorb BVS compared to the XIENCE EES. In particular, highly complex PCI, such as bifurcation stenting, long lesions or double layer stents, led to ischaemic events long after the index procedure. Our retrospective analysis generates a hypothesis of a potentially positive effect of DAPT on the odds ratio of ScT. In addition, there was no temporal relationship between DAPT discontinuation and VLST. For example, all ScT between 3- and 4-year follow-up occurred on average 331 days after DAPT cessation. To test whether prolonged DAPT truly outweighs the drawbacks in all patients treated with BVS or only in patients with highly complex PCI using BVS, prospective randomised studies using future-generation BVS should be carried out.

Causes of scaffold thrombosis

As previously reported, early ScT seems to be related to DAPT adherence and to procedural factors because optimisation in implantation techniques (predilatation, sizing and post-dilatation [PSP]) reduces the early stent thrombosis (ST) rate21,22. In contrast, the causes of VLST are not yet fully understood and are thought to be multifactorial. Figure 2 depicts temporal patterns of ScT. Delayed scaffold resorption causing scaffold discontinuation may lead to acquired malappostion, scaffold dismantling and neoatherosclerosis. These seem to be the leading mechanisms for VLST23,24. Also, the current data uncovered another possible mechanism of ScT. Three VLST occurred in lesions previously treated for restenosis with the XIENCE EES. Lack of optical coherence tomography (OCT) images precludes us from making a more definitive conclusion about the mechanisms of these particular cases and allows us only to speculate. It is possible that the DES itself caused DT. However, it cannot be excluded that resorption of the underlying BVS caused DT due to protrusion of the thrombogenic material or that it caused acquired malapposition of the DES. As new generations of scaffolds are being developed, it is important to investigate further whether it is safe to implant a metallic stent over the scaffold.

Overcoming very late device-related events

Bioresorbable scaffolds were designed to overcome very late device-related events often caused by neoatherosclerosis25. However, neoatherosclerosis did also appear in Absorb BVS-treated lesions26 and led to at least one ScT. Neoatherosclerosis will eventually occur within any device if sufficiently potent risk factors remain active and the Absorb BVS is not immune to the progression of neoatherosclerosis. In addition, the incidence of patient-oriented and device-related adverse events in the XIENCE EES group reported in the current article are not negligible. The rate of target lesion failure within the first year was 5.2%, with an annual change of ±2.2% thereafter, and a total target lesion failure rate of 16.1% at five-year follow-up. The patient-oriented composite endpoint in the XIENCE arm within first year was 10.6%. Afterwards, there was an annual change of ±4.0%, reaching 26.6% at five-year follow-up. Therefore, regardless of the stent platform, more effort on secondary prevention is needed.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, the AIDA trial was powered for the primary endpoint of TVF at two years. All secondary analyses on individual components of the primary endpoint, such as ScT, should be considered as hypothesis-generating. Second, the lack of systematic intravascular imaging in patients with clinical events, precludes more definite conclusions about the mechanisms related to BVS failure at different time points. Third, restarting or prolonging DAPT to three years after scaffold implantation was recommended at the request of the DSMB. This recommendation might have influenced the occurrence of thrombosis-related outcomes in patients on prolonged or restarted DAPT compared to patients who were treated according to the applicable guidelines and instructions for use. In addition, due to this change in recommendation and the retrospective character of the DAPT analysis, selection bias cannot be ruled out. Fourth, patients and clinicians were unblinded to treatment assignment after the report of concerns about the safety of the Absorb BVS upon the recommendation of the DSMB. Fifth, bleeding events were not monitored or adjudicated by a clinical events committee which precludes us from assessing the net benefit of prolonged DAPT.

Conclusions

In addition to previous reports, the increased risk of device-related myocardial infarction and revascularisation in patients treated with the Absorb bioresorbable vascular scaffold continues up to four years after index PCI and seems to plateau afterwards. Retrospective analyses implicate a reduction of the odds for scaffold thrombosis with the use of prolonged DAPT. The latter, however, is only hypothesis-generating and should be investigated further.

Impact on daily clinical practice

The current DAPT recommendations after DES implantation cannot simply be applied to scaffolds since the Absorb BVS is known to have a prolonged ischaemic risk: during the reabsorption process, it is associated with higher rates of device thrombosis. Our analysis hypothesises a reduction of this excessive risk by prolonging DAPT after BVS implantation. However, further research on DAPT duration after future-generation BVS implantation is warranted.

Supplementary data

Patient characteristics at baseline.

Procedural characteristics at baseline.

Clinical outcomes per study arm at four-year follow-up.

Descriptive characteristics of cases of definite scaffold thrombosis.

Descriptive characteristics of cases of definite stent thrombosis.

Study flow chart.

Antiplatelet therapy per follow-up in the Absorb BVS group.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors greatly acknowledge all the patients for their participation.

Funding

The AIDA trial was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Vascular. The Amsterdam UMC Heart Center received an unrestricted educational research grant from Abbott Vascular for the AIDA trial. The Research Department of the Cardiology Division of the Medical Center Leeuwarden received non-study-related unrestricted educational research grants from Abbott Vascular.

Conflict of interest statement

H.M. Garcia-Garcia was a member of the clinical events committee of the trial. J. Piek is a member of the Medical Advisory Board of Abbott Vascular. MedStar Washington Hospital Center receives research grants for clinical research from Abbott Vascular. J. Tijssen has served on the DSMB of the early ABSORB trials, including ABSORB II. J. Henriques has received research grants from Abbott Vascular. J. Wykrzykowska had received consultancy fees and research grants from Abbott Vascular. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

- BVS

bioresorbable vascular scaffold

- DAPT

dual antiplatelet therapy

- DES

drug-eluting stent

- DSMB

data and safety monitoring board

- DT

device thrombosis

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- ScT

scaffold thrombosis

- TLR

target lesion revascularisation

- TVF

target vessel failure

- TV-MI

target vessel myocardial infarction

- VLST

very late scaffold thrombosis

Contributor Information

Laura S.M. Kerkmeijer, Amsterdam UMC, Heart Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Mick P.L. Renkens, Amsterdam UMC, Heart Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Ruben Y.G. Tijssen, Amsterdam UMC, Heart Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Sjoerd H. Hofma, Department of Cardiology, Medical Center Leeuwarden, Leeuwarden, the Netherlands.

Rene J. van der Schaaf, Department of Cardiology, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

E. Karin Arkenbout, Department of Cardiology, Tergooi Hospital, Blaricum, the Netherlands.

Auke P.J.D. Weevers, Department of Cardiology, Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Dordrecht, the Netherlands.

Hector M. Garcia-Garcia, Cardiology, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC, USA.

Robin Kraak, Department of Cardiology, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Jan J. Piek, Amsterdam UMC, Heart Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Jan G.P. Tijssen, Amsterdam UMC, Heart Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Jose P.S. Henriques, Amsterdam UMC, Heart Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Robbert J. de Winter, Amsterdam UMC, Heart Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Joanna J. Wykrzykowska, UMC Groningen, Thorax Center, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands.

References

- Kufner S, Ernst M, Cassese S, Joner M, Mayer K, Colleran R, Koppara T, Xhepa E, Koch T, Wiebe J, Ibrahim T, Fusaro M, Laugwitz KL, Schunkert H, Kastrati A, Byrne RA ISAR-TEST-5 Investigators. 10-Year Outcomes From a Randomized Trial of Polymer-Free Versus Durable Polymer Drug-Eluting Coronary Stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:146–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka F, Pacheco E, Perkins LE, Lane JP, Wang Q, Kamberi M, Frie M, Wang J, Sakakura K, Yahagi K, Ladich E, Rapoza RJ, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Long-term safety of an everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold and the cobalt-chromium XIENCE V stent in a porcine coronary artery model. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:330–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.113.000990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkmeijer LSM, Tijssen RYG, Hofma SH, van der, Arkenbout KE, Kraak RP, Weevers A, Piek JJ, de Winter, Tijssen JGP, Henriques JPS, Wykrzykowska JJ, Collaborators Comparison of an everolimus-eluting bioresorbable scaffold with an everolimus-eluting metallic stent in routine PCI: three-year clinical outcomes from the AIDA trial. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:603–6. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali ZA, Gao R, Kimura T, Onuma Y, Kereiakes DJ, Ellis SG, Chevalier B, Vu MT, Zhang Z, Simonton CA, Serruys PW, Stone GW. Three-Year Outcomes With the Absorb Bioresorbable Scaffold: Individual-Patient-Data Meta-Analysis From the ABSORB Randomized Trials. Circulation. 2018;137:464–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kereiakes DJ, Ellis SG, Metzger C, Caputo RP, Rizik DG, Teirstein PS, Litt MR, Kini A, Kabour A, Marx SO, Popma JJ, McGreevy R, Zhang Z, Simonton C, Stone GW ABSORB III Investigators. 3-Year Clinical Outcomes With Everolimus-Eluting Bioresorbable Coronary Scaffolds: The ABSORB III Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2852–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kereiakes DJ, Ellis SG, Metzger DC, Caputo RP, Rizik DG, Teirstein PS, Litt MR, Kini A, Kabour A, Marx SO, Popma JJ, Tan SH, Ediebah DE, Simonton C, Stone GW ABSORB III Investigators. Clinical Outcomes Before and After Complete Everolimus-Eluting Bioresorbable Scaffold Resorption: Five-Year Follow-Up From the ABSORB III Trial. Circulation. 2019;140:1895–903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woudstra P, Grundeken MJ, Kraak RP, Hassell ME, Arkenbout EK, Baan J, Vis MM, Koch KT, Tijssen JG, Piek JJ, de Winter, Henriques JP, Wykrzykowska JJ. Amsterdam Investigator-initiateD Absorb strategy all-comers trial (AIDA trial): a clinical evaluation comparing the efficacy and performance of ABSORB everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold strategy vs the XIENCE family (XIENCE PRIME or XIENCE Xpedition) everolimus-eluting coronary stent strategy in the treatment of coronary lesions in consecutive all-comers: rationale and study design. Am Heart J. 2014;167:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykrzykowska JJ, Kraak RP, Hofma SH, van der, Arkenbout EK, IJsselmuiden AJ, Elias J, van Dongen, Tijssen RYG, Koch KT, Baan J, Vis MM, de Winter, Piek JJ, Tijssen JGP, Henriques JPS AIDA Investigators. Bioresorbable Scaffolds versus Metallic Stents in Routine PCI. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2319–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijssen RYG, Kraak RP, Hofma SH, van der, Arkenbout K, Weevers A, Elias J, van Dongen, Koch KT, Baan J, Vis M, de Winter, Piek JJ, Tijssen JGP, Henriques JPS, Wykrzykowska JJ. Complete two-year follow-up with formal non-inferiority testing on primary outcomes of the AIDA trial comparing the Absorb bioresorbable scaffold with the XIENCE drug-eluting metallic stent in routine PCI. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e426–33. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, Katus HA, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasché P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:2020–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es, Steg PG, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, McFadden E, Lansky A, Hamon M, Krucoff MW, Serruys PW Academic Research Consortium. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone GW, Kimura T, Gao R, Kereiakes DJ, Ellis SG, Onuma Y, Chevalier B, Simonton C, Dressler O, Crowley A, Ali ZA, Serruys PW. Time-Varying Outcomes With the Absorb Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold During 5-Year Follow-up: A Systematic Meta-analysis and Individual Patient Data Pooled Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:1261–9. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Räber L, Brugaletta S, Yamaji K, O'Sullivan CJ, Otsuki S, Koppara T, Taniwaki M, Onuma Y, Freixa X, Eberli FR, Serruys PW, Joner M, Sabaté M, Windecker S. Very Late Scaffold Thrombosis: Intracoronary Imaging and Histopathological and Spectroscopic Findings. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1901–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangas GD, Claessen BE, Mehran R, Brener S, Brodie BR, Dudek D, Witzenbichler B, Peruga JZ, Guagliumi G, Moses JW, Lansky AJ, Xu K, Stone GW. Clinical outcomes following stent thrombosis occurring in-hospital versus out-of-hospital: results from the HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1752–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonamici P, Marcucci R, Migliorini A, Gensini GF, Santini A, Paniccia R, Moschi G, Gori AM, Abbate R, Antoniucci D. Impact of platelet reactivity after clopidogrel administration on drug-eluting stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2312–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Driscoll-Shempp P, Cutlip DE, Steg PG, Normand SL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Cohen DJ, Holmes DR, Krucoff MW, Hermiller J, Dauerman HL, Simon DI, Kandzari DE, Garratt KN, Lee DP, Pow TK, Ver Lee, Rinaldi MJ, Massaro JM DAPT Study Investigators. Twelve or 30 Months of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after Drug-Eluting Stents. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2155–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SH, Chae IH, Park JJ, Lee HS, Kang DY, Hwang SS, Youn TJ, Kim HS. Stent Thrombosis With Drug-Eluting Stents and Bioresorbable Scaffolds: Evidence From a Network Meta-Analysis of 147 Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:1203–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh RW, Kereiakes DJ, Steg PG, Cutlip DE, Croce KJ, Massaro JM, Mauri L DAPT Study Investigators. Lesion Complexity and Outcomes of Extended Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2213–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotomi Y, Suwannasom P, Serruys PW, Onuma Y. Possible mechanical causes of scaffold thrombosis: insights from case reports with intracoronary imaging. EuroIntervention. 2017;12:1747–56. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-16-00471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuma Y, Honda Y, Asano T, Shiomi H, Kozuma K, Ozaki Y, Namiki A, Yasuda S, Ueno T, Ando K, Furuya J, Hanaoka KI, Tanabe K, Okada K, Kitahara H, Ono M, Kusano H, Rapoza R, Simonton C, Popma JJ, Stone GW, Fitzgerald PJ, Serruys PW, Kimura T. Randomized Comparison Between Everolimus-Eluting Bioresorbable Scaffold and Metallic Stent: Multimodality Imaging Through 3 Years. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Paz L, Capodanno D, Gori T, Nef H, Latib A, Caramanno G, Di Mario, Naber C, Lesiak M, Capranzano P, Wiebe J, Mehilli J, Araszkiewicz A, Pyxaras S, Mattesini A, Geraci S, Naganuma T, Colombo A, Münzel T, Sabaté M, Tamburino C, Brugaletta S. Predilation, sizing and post-dilation scoring in patients undergoing everolimus-eluting bioresorbable scaffold implantation for prediction of cardiac adverse events: development and internal validation of the PSP score. EuroIntervention. 2017;12:2110–7. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-16-00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijssen RYG, Kraak RP, Elias J, van Dongen, Kalkman DN, Nassif M, Sotomi Y, Asano T, Katagiri Y, Collet C, Piek JJ, Henriques JPS, de Winter, Tijssen JGP, Onuma Y, Serruys PW, Wykrzykowska JJ. Implantation techniques (predilatation, sizing, and post-dilatation) and the incidence of scaffold thrombosis and revascularisation in lesions treated with an everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold: insights from the AIDA trial. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e434–42. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-17-01152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji K, Ueki Y, Souteyrand G, Daemen J, Wiebe J, Nef H, Adriaenssens T, Loh JP, Lattuca B, Wykrzykowska JJ, Gomez-Lara J, Timmers L, Motreff P, Hoppmann P, Abdel-Wahab M, Byrne RA, Meincke F, Boeder N, Honton B, O'Sullivan CJ, Ielasi A, Delarche N, Christ G, Lee JKT, Lee M, Amabile N, Karagiannis A, Windecker S, Räber L. Mechanisms of Very Late Bioresorbable Scaffold Thrombosis: The INVEST Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2330–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinnouchi H, Torii S, Sakamoto A, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Finn AV. Fully bioresorbable vascular scaffolds: lessons learned and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:286–304. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumino Y, Yonetsu T, Ueno H, Nogami K, Misawa T, Hada M, Yamaguchi M, Hoshino M, Kanaji Y, Sugiyama T, Sasano T, Kakuta T. Clinical significance of neoatherosclerosis observed at very late phase between 3 and 7 years after coronary stent implantation. J Cardiol. 2021;78:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Ferrone M, Wang Q, Perkins LEL, McGregor J, Redfors B, Zhou Z, Rapoza R, Conditt GB, Finn A, Virmani R, Kaluza GL, Granada JF. Impact of Coronary Atherosclerosis on Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold Resorption and Vessel Wall Integration. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5:619–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Patient characteristics at baseline.

Procedural characteristics at baseline.

Clinical outcomes per study arm at four-year follow-up.

Descriptive characteristics of cases of definite scaffold thrombosis.

Descriptive characteristics of cases of definite stent thrombosis.

Study flow chart.

Antiplatelet therapy per follow-up in the Absorb BVS group.