Highlights

-

•

Rooibos exhibits the strongest MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities.

-

•

Aspalathin, orientin and isoorientin trap MGO to form the corresponding adducts.

-

•

Fortification of rooibos reduces dicarbonyls and AGEs formation in the cookie.

Chemical compounds studied in this article: Methylglyoxal (PubChem CID: 880), Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine (PubChem CID: 123800), Orientin (PubChem CID: 5281675), Isoorientin (PubChem CID: 114776), Vitexin (PubChem CID: 5280441), Isovitexin (PubChem CID: 162350), Aspalathin (PubChem CID: 11282394)

Keywords: Advanced glycation end products, Cookies, Herbal tea, Methylglyoxal, Reactive carbonyl species

Abstract

In thermally processed foods, several heat-induced toxicants are potentially formed due to the Maillard reaction, such as α-dicarbonyls and advanced glycation end products (AGEs). In the present work, we found that the methylglyoxal (MGO)-trapping and antiglycative activities of the herbal tea samples correlated strongly with their total phenolic and flavonoid contents. Among the tested herbal tea samples, rooibos exhibited the strongest MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities against AGEs formation. Aspalathin, orientin and isoorientin were further identified as the major bioactive compounds of rooibos that scavenged MGO to form the corresponding mono-MGO adducts. Moreover, the contents of dicarbonyls and AGEs in the cookie were remarkably reduced by fortification with rooibos. Altogether, our current findings suggested that rooibos might serve as a functional ingredient to reduce intake of dietary reactive carbonyl species (RCS) and AGEs from thermally processed foods, especially bakery products.

Introduction

The Maillard reaction (MR) is a non-enzymatic browning reaction that provides desirable and unique flavor and color to the thermally processed foods. However, thermal treatment may also result in the formation of potentially harmful compounds through the MR, such as α-dicarbonyls, acrylamide, heterocyclic amines and advanced glycation end products (AGEs). In the MR, the carbonyl groups of reducing sugars react with amino groups of amino acids to form Schiff bases that further undergo the rearrangement reactions to generate Amadori or Heyns compounds in the case of aldoses or ketoses, respectively (Q. Z. Zhang, Wang, & Fu, 2020). Through enolization and elimination reactions, these products can generate various reactive carbonyl species (RCS), such as deoxyosones, methyglyoxal (MGO) and glyoxal (GO) (Chaudhuri, et al., 2018). A recent study comprehensively analyzed several α-dicarbonyls, including MGO, GO and 3-deoxyglucosone (3-DG), in a wide range of foods and drinks and the results showed that dried fruits, snacks, cookies and bakery products had high concentrations of total α-dicarbonyls (Maasen, et al., 2021). Also, high levels of MGO and GO were found in honey, cheese and soft drinks (Hellwig, Gensberger-Reigl, Henle, & Pischetsrieder, 2018). Given high reactivity of carbonyl groups, RCS can cause protein modifications, cellular apoptosis, inflammation and tissue injury (Ramasamy, Yan, & Schmidt, 2006). Increased exposure to dietary RCS significantly elevates accumulation of MGO, GO and 3-DG in the plasma, liver and kidney (van Dongen, et al., 2021). Therefore, dicarbonyl stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of aging, obesity and several chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular diseases (Hellwig, et al., 2018).

AGEs are a heterogenous group of compounds generated through the non-enzymatic glycation of proteins, lipids and nucleotides (Zhu, Snooks, & Sang, 2018). As potent glycating agents, MGO and GO can react with amino acids, especially lysine and arginine, to generate so-called AGEs. Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine (CML) and Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine (CEL) are the two common AGEs ubiquitously present in foodstuffs. Meanwhile, arginine residues present in proteins can be modified by MGO and GO to form methylglyoxal-hydroimidazolone 1 (MG-H1) and glyoxal-hydroimidazolone 1 (G-H1), respectively. These two AGEs are also commonly present in thermally processed foods such as roasted meats and bakery products. High contents of AGEs can be found in biscuits, chocolate, crackers, cakes, breads and grilled pork, while fruits and vegetables have low contents of AGEs (Q. Z. Zhang, et al., 2020). Research has shown that increased accumulation of AGEs is linked with several chronic diseases, particularly diabetes (Chaudhuri, et al., 2018).

Due to the fact that both dietary RCS and AGEs are potential harmful compounds for human health, control of their contents in processed foods may serve as a potential approach to decrease intake of RCS and AGEs. It has been reported that some natural occurring antioxidants possess excellent antiglycative activities against AGEs formation, especially flavonoids (Zhou, Cheng, Xiao, & Wang, 2020). Besides flavonoids, chalcones and anthocyanins also remarkably inhibited fluorescent AGEs formation in chemical models. Since RCS are the precursors of AGEs formation, the antiglycative effects of phytochemicals against AGEs formation are, at least in part, originated from their RCS-trapping activities. Herbal tea is the mixture made from leaves, flowers and/or roots of various plant species. Previously, the health beneficial activities of longan flowers, mint, butterfly pea flower, chrysanthemum, roselle, guava leaves, Houttuynia cordata (dokudami) and rooibos have been reported, especially antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (Bramati, Aquilano, & Pietta, 2003; H. Y. Chen and Yen, 2007, Hsieh et al., 2008, Jeyaraj et al., 2021; Y. F. Li et al., 2019, Padmini et al., 2008, Tian et al., 2012, Wu et al., 2018). The biological activities of these herbal teas are mainly originated from their bioactive compounds, particularly flavonoids. Therefore, this study attempts to compare the MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities of these herbal tea samples. Meanwhile, total contents of polyphenols and flavonoids of herbal tea samples were also evaluated to discuss their RCS-trapping and antiglycative mechanisms. Finally, the bioactive compounds of the most effective sample were quantified and its RCS-trapping and antiglycative activities were also evaluated in a cookie model.

Methods and materials

Chemicals and reagents

Herbal teas samples were purchased from a local market (Taipei, Taiwan). Glyoxal (40 % in aqueous solution), diacetyl (DA), quercetin and o-phenylenediamine were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Great Britain, UK). Methylglyoxal (40 % in aqueous solution), sodium azide, BSA, glucose, sodium hydroxide, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, sodium bicarbonate and lanthionine (LAN) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Aspalathin and 3-DG were purchased from Biosynth Carbosynth (St. Gallen, Switzerland). Glucosone, 3-deoxygalactosone (3-DGal), orientin, isoorientin, vitexin, isovitexin, isoquercetin and rutin were purchased from Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Nothofagin was purchased from Aobious (Gloucester, MA, USA). CML, CEL, MG-H1, G-H1, methylglyoxal-lysine dimer (MOLD), glyoxal-lysine dimer (GOLD) and furosine were purchased form Iris Biotech (Marktredwitz, Germany). Salts, sugar, canola oil, white flour and baking powder were purchased from a local supermarket (Taipei, Taiwan). All solvents used in this study are analytical or LC-MS grade and sourced from Sigma.

Preparation of herbal tea extracts

Ten grams of dried herbal tea leaves or flowers were pulverized and then extracted with 100 mL methanol by ultrasonication for 30 min at room temperature. The supernatant was filtered through a No.4 Whatman filter paper (Maidstone, UK). The residue was ultrasonically extracted with 100 mL methanol again and then the filtered supernatants were combined. The solvent of the combined supernatant was removed using a rotary evaporator. The dried extract of herbal tea samples was stored at −20 °C until analysis.

Determination of total phenolic content and total flavonoids

The total phenolic contents of herbal teas samples were determined using a Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method (Hsieh, et al., 2008). In brief, 100 μL of the dried extract dissolved in methanol was mixed with 2 mL water and 1 mL Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, and then 5 mL 20 % sodium bicarbonate was added. After 20 min, the absorbance at 735 nm wavelength was measured. Meanwhile, various concentrations of gallic acid were also measured to prepare a standard curve. The total phenolic content of herbal teas samples are expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per 1 g of sample. Determination of total flavonoids was performed as according to the method described previously (Quettier-Deleu, et al., 2000). In brief, 1 mL of the dried extract dissolved in methanol was mixed with 1 mL AlCl3·6H2O. After incubation for 10 min, the absorbance at 430 nm wavelength was measured. Various concentrations of quercetin standard solution were also measured to prepare a standard curve and the results are expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalents (QE) per 1 g of sample.

Determination of RCS-trapping activity

The RCS-trapping activities of the herbal samples were carried out as described previously, with slight modifications (X. M. Li, Zheng, Sang, & Lv, 2014). Briefly, 500 μL herbal tea extract (2500, 5000, 10,000 and 20000 ppm, dissolved in methanol) was mixed with 500 μL 0.5 mM MGO dissolved in 10 × PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was terminated by addition of 10 μL acetic acid. To evaluate the MGO-trapping activity of polyphenols of rooibos, 500 μL 2 mM polyphenol standards were incubated with 500 μL 0.5 mM MGO in 10 × PBS at 37 °C for 1 h. For derivatization of MGO, an aliquot of the sample was mixed with 30 mM OPD and then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Unreacted MGO was derivatized into 2-methylquinoxaline, which was detected using an UPLC system (Acquity H-class, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a Waters photodiode-array detector. Chromatographic separations were achieved using an Acquity C18 column (BEH C18, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1 % formic acid in water as mobile phase A and 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile as mobile phase B. The separation gradient program was set as follows: 0–4 min, 5–95 % B; 4–7 min, 95 % B. The flow rate and injection volume were set at 0.2 mL/min and 5 μL, respectively. The wavelength absorbance was set at 312 nm. The MGO-trapping capacity was calculated by the following equation.

| MGO-trapping capacity (%) = (amount of MGO in the control sample - amount of MGO in the herbal tea sample)/amount of MGO in the control group × 100 |

Antiglycative activity in a glucose-BSA model

Inhibitory effects of herbal tea samples against AGEs formation were carried out as previously described, with some modifications (Gao, Sun, Li, Zhou, & Wang, 2020). Fifty microliters of the herbal sample (1500, 3000 and 6000 ppm, dissolved in methanol), 950 μL of 10 × PBS solution containing 0.8 M glucose, 50 mg/mL BSA and 20 μL of sodium azide (10.2 mg/mL, dissolved in 10 × PBS) were mixed and then incubated at 37 °C for 7 days. In the control group, 50 μL methanol was used instead of the herbal tea sample. For evaluating the antiglycative activities of polyphenols of rooibos, 50 μL of 1 mM polyphenol standards were mixed with 950 μL 10 × PBS solution containing 0.8 M glucose, 50 mg/mL BSA and 20 μL sodium azide and then incubated at 37 °C for 7 days. At the end the experiment, 200 μL of the solution were transferred into a black 96-well plate and the fluorescent intensity was measured with excitation/emission wavelength at 340/420 nm on behalf of the formation of fluorescent AGEs. The inhibitory effect of the herbal sample was calculated by the following equation:

| AGE inhibitory capacity (%) = (fluorescent intensity of the control group – fluorescent intensity of the herbal tea sample)/fluorescent intensity of the control group × 100 |

Quantification of bioactive compounds in herbal tea samples

The bioactive compounds in rooibos were quantified using an UPLC system (Acquity H-class, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to an Acquity QDa single-quadrapole mass detector with electrospray ionization source (Acquity QDa, Waters). Chromatographic separations were achieved using an Acquity C18 column (BEH C18, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters). The flow rate and injection volume were set at 0.2 mL/min and 5 μL, respectively. The temperature of column oven was set at 30 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1 % formic acid in water as mobile phase A and 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile as mobile phase B. The separation gradient program was set as follows: 0 – 25 min, 5–20 % B; 25–26 min, 20 – 95 % B; 26–30 min, 95 % B. Selected ion recording (SIR) channels were acquired on the QDa to quantify the bioactive compounds in rooibos. The negative ions for quantification of aspalathin, nothofagin, vitexin/isovitexin, orientin/isoorientin, isoquercetin and rutin were set at m/z 451.4, m/z 435.4, m/z 431.4, m/z 447.3, m/z 463.3 and m/z 609.5, respectively. The capillary voltage was 0.8 kV, the probe temperature was 600 °C, the cone voltage was 15 V and the target sampling rate was 14.3 pts/sec. Data processing were performed using the Empower 3 software (Waters).

Identification of polyphenol-MGO adducts

To prepare the polyphenol-MGO adducts, 500 μL of aspalathin, vitexin, isovitexin, orientin, isoorientin (1 mM) were mixed with 500 μL of MGO (10 mM) in 10 × PBS and then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Meanwhile, 500 μL of 5000 ppm methanol extract of rooibos were mixed with 500 μL of MGO (10 mM) in 10 × PBS and then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. At the end of the experiment, the reaction was terminated by addition of 10 μL acetic acid. An UPLC system (Acquity UPLC system, Waters) equipped with a quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Xevo G2-XS qTOF, Waters) was performed to identify the polyphenol-MGO adducts in rooibos. Chromatographic separations were achieved using an Acquity HSS T3 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm, Waters). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1 % formic acid in water (A) and 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile (B). The gradient program was set as follows: 0 – 38 min, 10 – 15 % B; 38 – 38.1 min, 15 – 95 % B; 38.1 – 41 min, 95 % B. The injection volume and oven temperature were set at 2 μL and 40 °C, respectively. The global MS parameters were set as follows: capillary voltage, 2.8 kV; sampling cone voltage, 30 V; extraction cone voltage, 4 V; source temperature, 120 °C; desolvation gas flow rate, 800 L/h; desolvation temperature, 400 °C. Data acquisition and processing were performed using MassLynx software.

Cookie model

The ingredients of cookies consisted of water (1.5 mL), salt (0.1 g), baking powder (0.12 g), sugar (3.5 g), canola oil (1.5 mL), and white flour (7.5 g) (X. C. Zhang, Chen, & Wang, 2014). These ingredients and 0.5 or 1 % (w/w) of the dried extract of rooibos were mixed thoroughly to develop dough and then baked at 200 °C for 16 min in an oven. Finally, the cookie sample was cooled to room temperature prior to storage at −20 °C.

Determination of moisture, color and pH of cookies

The weight of the cookie sample was measured and then dried at 110 °C until a constant weight was achieved. The moisture content was calculated according to its weight loss. For measurement of pH value, an aliquot of 0.4 g of ground cookie was added to 20 mL of water and shaken for 1 min. The mixture was allowed to stand for 1 h at room temperature and the supernatant was collected for measurement of the pH value (FiveEasy, Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland). The color profile of lightness (L*), redness (a*), and yellowness (b*) was measured on the cookie using a colorimeter (Flu, Shenzhen, China).

Determination of dicarbonyls in cookie samples

Extraction of dicarbonyls in cookie samples was performed as previously described, with slight modifications (Maasen, et al., 2021). In brief, 30 mg of the ground cookie were mixed with 180 μL water and 720 μL OPD (1 mg/mL 1.6 M perchloric acid). The mixture was allowed to stand for 20 h at room temperature. After centrifugation at 10,000g for 20 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected for UPLC analysis. Determination of dicarbonyls in the cookie was performed using an UPLC system (Acquity UPLC, Waters) equipped with a triple-quadrupole electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometer (Xevo TQD, Waters). Chromatographic separations were achieved using an Acquity C18 column (BEH C18, 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters). The mobile phase contained 0.1 % formic acid in water (A) and 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile (B). The gradient program was set as follows: 0 – 12 min, 2 – 15 % B; 12 – 16 min, 15 – 95 % B; 16 – 18 min, 95 % B. The injection volume and oven temperature were set at 2 μL and 30 °C, respectively. The global MS parameters were set as follows: capillary voltage, 3900 V; desolvation temperature, 600 °C; desolvation gas flow rate, 800L/h; source temperature, 150 °C. The multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions of dicarbonyls are given in Table S1.

Determination of AGEs in cookie samples

Extraction of AGEs from the cookie sample was carried out as previously described, with some modifications (G. J. Chen & Smith, 2015). In brief, 150 mg of the cookie sample was defatted with dichloromethane/methanol (8:2, v/v) and then reduced with 2 mL of 1 M sodium borohydride and 1 mL sodium boric buffer for 4 h at room temperature. The reduced sample was mixed with 1.5 mL 12 M HCl and then flushed under a stream of nitrogen gas before hydrolysis at 110 °C for 20 h. Determination of AGEs in the cookie was performed using an UPLC system (Acquity UPLC, Waters) equipped with a triple-quadrupole electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometer (Xevo TQD, Waters). Chromatographic separations were achieved using an Acquity BEH Amide column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters). The mobile phase consisted of 5 mM ammonium formate in 98 % acetonitrile aqueous solution containing 0.1 % formic acid (A) and 5 mM ammonium formate in 90 % acetonitrile containing 0.1 % formic acid (B). The gradient program was set as follows: 0 – 15 min, 100 – 30 % B; 15 – 20 min, 30 % B. The injection volume and oven temperature were set at 2 μL and 60 °C, respectively. The global MS parameters were set as follows: capillary voltage, 3900 V; desolvation temperature, 600 °C; desolvation gas flow, 800L/h; source temperature, 150 °C. The multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions and chromatograms of AGEs, furosine, and LAN are given in Figure S1 and Table S2.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations from triplicate experiments. Significant differences were statistically detected by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were performed using the SPSS software (IBM, Armonk, USA) to assess the relationships between the MGO-trapping activities, antiglycative activities and other variables including total phenol and flavonoid contents.

Results

Total phenolic and flavonoid contents of herbal tea samples

To characterize the RCS trapping and antiglycative effects of herbal tea samples, their total phenolic contents and flavonoids were analyzed in this study. Among the herbal tea samples, longan flower and rooibos had the highest total phenolic contents (150.11 ± 2.50 and 110.81 ± 4.37 mg/g GAE, respectively), followed by guava leaves, mint leaves and dokudami (89.81 ± 6.70, 80.36 ± 3.38 and 51.73 mg/g GAE, respectively)(Table 1). Roselle, chrysanthemum and butterfly pea flower had the lowest total phenolic contents (28.94 ± 2.10, 27.56 ± 0.63 and 22.75 ± 0.58 mg/g GAE, respectively). Meanwhile, rooibos and guava leaves had the highest total flavonoid contents among the herbal tea samples (23.31 ± 0.72 and 20.35 ± 2.01 mg/g QE, respectively), followed by dokudami and mint (11.63 ± 0.33 and 7.06 ± 0.21 mg/g QE, respectively). Longan flower, chrysanthemum, butterfly pea flower and roselle had the lowest total flavonoid contents (5.20 ± 0.13, 5.01 ± 0.30, 4.95 ± 0.18 and 1.80 ± 0.56 mg/g QE, respectively).

Table 1.

Total phenolic and flavonoid contents, MGO-trapping and antiglycative effects of herbal tea samples.

| Total phenol (mg GAE/g) | Total flavonoid (mg QE/g) | MGO-trapping (%) |

BSA-glucose (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5000 ppm | 10000 ppm | 20000 ppm | 1500 ppm | 3000 ppm | 6000 ppm | |||

| Longan flower | 150.11 ± 2.50a | 5.20 ± 0.13d | 29.66 ± 2.38Ab | 39.53 ± 1.21Bb | 43.45 ± 1.25Bc | 21.80 ± 2.01Aa | 27.21 ± 1.34Bb | 32.51 ± 0.58Cc |

| Mint | 80.36 ± 3.38c | 7.06 ± 0.21d | 16.91 ± 0.57Ac | 26.51 ± 1.90Bc | 40.47 ± 1.87Cc | −0.37 ± 5.61Ac | 10.36 ± 1.93Bd | 30.88 ± 3.92Cc |

| Butterfly pea flower | 22.75 ± 0.58d | 4.95 ± 0.18d | 1.85 ± 1.02Ad | 6.01 ± 1.57Bd | 14.61 ± 1.72Ce | −6.66 ± 1.30Ac | −5.43 ± 3.82Ae | 1.89 ± 1.39Be |

| Chrysanthemum | 27.56 ± 0.63d | 5.01 ± 0.30d | −10.53 ± 0.83Ae | −18.85 ± 1.88Be | 4.07 ± 0.58Cf | −1.22 ± 4.36Ac | −0.42 ± 0.99Ae | 7.64 ± 2.70Be |

| Roselle | 28.94 ± 2.10d | 1.80 ± 0.56e | 2.67 ± 0.43Ad | 2.67 ± 2.47Ad | 2.75 ± 1.37Af | 6.78 ± 4.47Abc | 11.99 ± 1.59ABd | 17.37 ± 0.77Bd |

| Guava leaves | 89.81 ± 6.70c | 20.35 ± 2.01b | 31.31 ± 1.57Ab | 44.67 ± 2.51Bb | 57.84 ± 3.26Cb | 14.95 ± 2.58Aab | 27.31 ± 0.83Bb | 41.72 ± 0.46Cb |

| Dokudami | 51.73 ± 3.98e | 11.63 ± 0.33c | 13.67 ± 1.18Ac | 24.30 ± 2.54Bc | 35.47 ± 0.91Cd | −2.42 ± 1.85Ac | 18.67 ± 1.87Bc | 31.09 ± 1.66Cc |

| Rooibos | 110.81 ± 4.37b | 23.31 ± 0.72a | 51.20 ± 0.96Aa | 73.74 ± 1.24Ba | 77.27 ± 0.69Ca | 17.80 ± 4.48Aab | 37.76 ± 2.54Ba | 54.94 ± 1.61Ca |

Data are expressed as means ± SD from triplicates. Different uppercase letters in the same row represent statistical differences among the herbal tea samples with the different treatment concentrations. Different lowercase letters in the same column represent statistical differences among herbal tea samples (p < 0.05).

Methylglyoxal-trapping and antiglycative activities of herbal tea samples

In this study, MGO-trapping activities were investigated with various concentrations of herbal tea samples and the results showed that most of herbal tea samples can scavenge MGO in a dose-dependent manner except chrysanthemum and roselle (Table 1). When the treatment concentration was 20000 ppm, rooibos and guava leaves had the highest MGO-trapping activities (77.27 ± 0.69 and 57.84 ± 3.26 %, respectively), followed by longan flower, mint and dokudami (43.45 ± 1.25, 40.47 ± 1.87 and 35.47 ± 0.91 %, respectively). Meanwhile, the BSA-glucose model was carried out to evaluate antiglycative activities of herbal tea samples. At the concentration of 1500 ppm, only longan flower, roselle, guava leaves and rooibos exhibited antiglycative effects against fluorescent AGEs formation (Table 1). When the concentrations of herbal tea samples raised to 6000 ppm, rooibos, guava leaves and longan flowers exerted the highest antiglycative activities (54.91 ± 1.61, 41.72 ± 0.46 and 32.51 ± 0.58 %, respectively), while antiglycative activities of butterfly pea flower and chrysanthemum were the lowest (1.89 ± 1.39 and 7.64 ± 2.70 %, respectively). To characterize the possible factors that contribute the MGO-trapping and antiglycative effects of rooibos, the correlations between the MGO-trapping and antiglycative effects of herbal tea samples and their total polyphenols and flavonoids were evaluated. Both MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities of herbal tea samples correlated strongly with their total polyphenolic contents and flavonoids (p < 0.05)(Figure S2). These results suggest that the polyphenols, especially flavonoids, present in herbal tea samples potentially contribute their MGO-trapping and antiglycative effects.

Since rooibos exhibited the highest antiglycative activities among the herbal tea samples, its concentrations of aspalathin, nothofagin, vitexin, isovitexin, orientin, isoorientin, isoquercetin and rutin were also quantified (Table 2). The most abundant polyphenol found in the methanol extract of rooibos was isoorientin (137.97 ± 11.14 μM), followed by aspalathin, orientin, isovitexin and vitexin (95.51 ± 1.95, 88.47 ± 6.15, 45.56 ± 1.98 and 39.03 ± 3.86 μM, respectively). The concentrations of nothofagin, isoquercetin and rutin in the methanol extract of rooibos were relatively low. Among these polyphenol compounds, O-glycosyl flavonols, including isoquercetin and rutin, exhibited the highest MGO-trapping activities (45.74 ± 1.92 and 46.99 ± 0.99 %, respectively), followed by aspalathin, and vitexin (38.15 ± 1.24 and 35.75 ± 1.02 %)(Table 2). After incubation for 7 days, isoquercitrin had the strongest antiglycative activity (52.09 ± 0.35 %), followed by rutin, orientin, isoorientin, isovitexin and vitexin (49.33 ± 0.81, 47.78 ± 0.72, 46.12 ± 1.88, 45.72 ± 1.67 and 42.03 ± 0.73 %, respectively). C-glucosyl dihydrochalcones, including aspalathin and nothofagin, exhibited the lowest antiglycative activities.

Table 2.

Polyphenol contents of rooibos and their MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities.

| Concentration (μM) | MGO-trapping (%) | BSA-glucose (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspalathin | 95.51 ± 1.95 | 38.15 ± 1.24b | 35.07 ± 6.72 cd |

| Nothofagin | 10.49 ± 0.29 | 32.47 ± 2.34 cd | 33.76 ± 0.45d |

| Vitexin | 39.03 ± 3.86 | 35.75 ± 1.02bd | 42.03 ± 0.73bc |

| Isovitexin | 45.56 ± 1.98 | 33.66 ± 0.74c | 45.72 ± 1.67ab |

| Orientin | 88.47 ± 6.15 | 31.71 ± 1.08c | 47.78 ± 0.72ab |

| Isoorientin | 137.97 ± 11.14 | 32.30 ± 0.68c | 46.12 ± 1.88ab |

| Isoquercitrin | 18.57 ± 1.49 | 45.74 ± 1.92a | 52.09 ± 0.35a |

| Rutin | 11.65 ± 0.87 | 46.98 ± 0.99a | 49.33 ± 0.81ab |

Data are expressed as means ± SD from triplicates. Different letters in the same column represent statistical differences among polyphenol compounds (p < 0.05).

Characterization of methylglyoxal-polyphenol adducts in rooibos

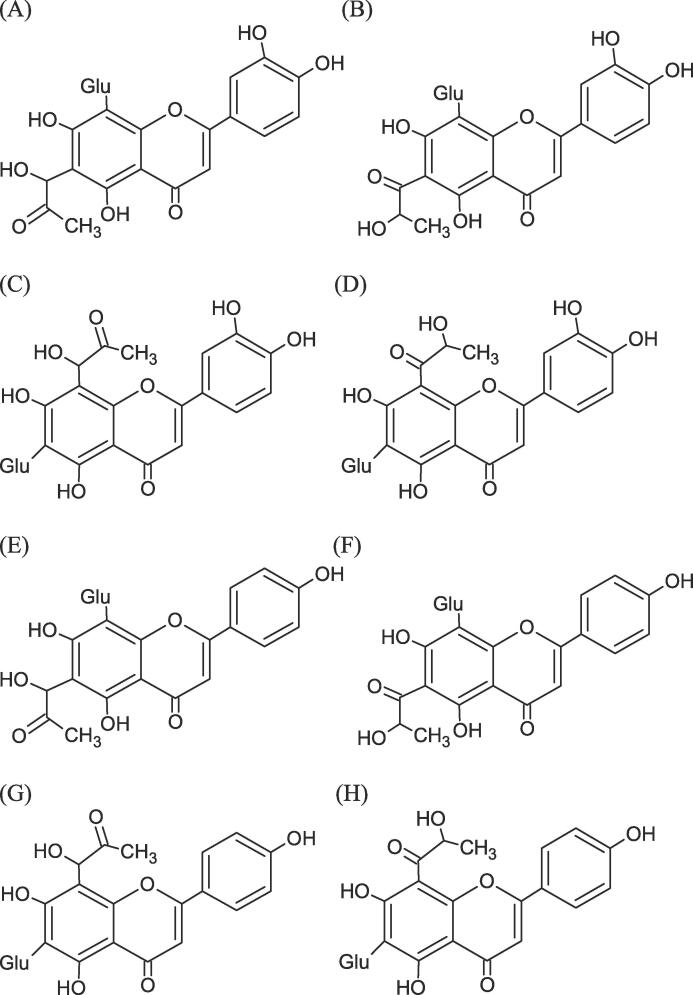

The most abundant polyphenol compounds present in the methanol extract of rooibos, including aspalathin, orientin, isoorientin, vitexin and isovitexin (1 mM), were incubated with 10 mM MGO in 10 × PBS at 37 °C for 1 h to study whether their corresponding MGO adducts could be formed. When orientin was incubated with MGO, two major peaks were detected at 13.82 and 15.99 min, respectively, with an accurate protonated ion at m/z 521.1295 [M + H]+ (elemental composition of C24H24O13)(Fig. 1 and Table 3). Similar results were also found when isoorientin was incubated with MGO. The fragment ions of these four peaks were identical (Table 3, Figure S3 and S4), of which m/z 449 was 72 mass units lower than that of orientin and isoorientin. These results suggest these four peaks were the mono-MGO adducts of orientin and isoorientin. Similarly, when vitexin or isovitexin was incubated with MGO, two major peaks of m/z 505.1346 (elemental composition of C24H24O12) were detected and their fragment ions were identical (Table 3, Figure S5 and S6). The fragment ion of m/z 433 was 72 mass units lower than that of vitexin and isovitexin, suggesting that they were the mono-MGO adducts of vitexin and isovitexin. Previous studies have shown that the A-ring of the flavonoids is the major active site to scavenge MGO and B-ring of flavonoids might be able to scavenge MGO only when the positions of their A-ring were occupied by MGO (X. M. Li, et al., 2014; G. M. Liu et al., 2017, Sang et al., 2007). Thus, the proposed chemical structures of mono-MGO adducts of aspalathin, orientin, isoorientin, vitexin and isovitexin are given in Fig. 2. When aspalathin was incubated with MGO, a major peak was detected at 15.83 min with an accurate deprotonated ion at 523.1452 [M−H]− (elemental composition of C24H28O13) (Fig. 1 and Table 3). The MS/MS spectrum of this peak had a fragment ion m/z 451 [M−72−H]−, which was 72 mass units lower than that of aspalathin. Importantly, the fragment ions of this compound, including m/z 361, m/z 331, m/z 209 and m/z 167, were identical with the fragment ions of aspalathin (Table 3 and Figure S7) (Kreuz et al., 2008, van der Merwe et al., 2010). Altogether, this compound was identified as a mono-MGO adduct of aspalathin. In addition, this mono-MGO adduct of aspalathin underwent a typical loss of a glucose unit, a B ring unit (m/z 122) and a water unit to generate the fragment ion m/z 221 [M−162−18−122−H]−, indicating that MGO conjugated at the C-5 position of the A-ring of aspalathin (Figure S8). Moreover, when the methanol extract of rooibos was incubated with 10 mM MGO at 37 °C for 1 h, the MS/MS spectra results showed that the mono-MGO adducts of aspalathin, orientin and isoorientin were generated, while only trace amounts of the mono-MGO adducts of vitexin and isovitexin were formed (Fig. 1). These results suggest that aspalathin, orientin and isoorientin were the major polyphenol compounds of rooibos responsible for its MGO-trapping activities.

Fig. 1.

LC-MS/MS daughter ion-scan chromatograms of (A) m/z 521.1+ (B) m/z 505.1+ and (C) m/z 523.1− for detection of mono-MGO adducts of orientin, isoorientin, vitexin, isovitexin and aspalathin.

Table 3.

Identification of MGO-polyphenol adducts by UPLC-qTOF-MS.

| RT (min) | Molecular formula | Polarity | Theoretical mass | Observed mass | Error (ppm) | MS/MS fragments | Rooibos + MGO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orientin-MGO adduct-1 | 13.82 | C24H24O13 | Positive | 521.1295 | 521.1292 | −0.57 | 503, 485, 467, 449, 437, 407, 383,355, 337, 325 | + |

| Orientin-MGO adduct-2 | 15.99 | C24H24O13 | Positive | 521.1295 | 521.1293 | −0.38 | 503, 485, 467, 449, 437, 407, 383,355, 337, 325 | + |

| Isoorientin-MGO adduct-1 | 14.00 | C24H24O13 | Positive | 521.1295 | 521.1292 | −0.57 | 503, 485, 467, 449, 437, 407, 383,355, 337, 325 | + |

| Isoorientin-MGO adduct-2 | 17.09 | C24H24O13 | Positive | 521.1295 | 521.1293 | −0.38 | 503, 485, 467, 449, 437, 407, 383,355, 337, 325 | + |

| Vitexin-MGO adduct-1 | 18.92 | C24H24O12 | Positive | 505.1346 | 505.1342 | −0.79 | 487, 469, 451, 433, 421, 391, 367, 399, 321, 309 | tr |

| Vitexin-MGO adduct-2 | 20.93 | C24H24O12 | Positive | 505.1346 | 505.1340 | −1.18 | 487, 469, 451, 433, 421, 391, 367, 399, 321, 309 | tr |

| Isovitexin-MGO adduct-1 | 20.32 | C24H24O12 | Positive | 505.1346 | 505.1344 | −0.40 | 487, 469, 451, 433, 421, 391, 367, 399, 321, 309 | tr |

| Isovitexin-MGO adduct-2 | 24.60 | C24H24O12 | Positive | 505.1346 | 505.1345 | −0.20 | 487, 469, 451, 433, 421, 391, 367, 399, 321, 309 | tr |

| Aspalathin-MGO adduct | 15.83 | C24H28O13 | Negative | 523.1452 | 523.1452 | 0.00 | 505, 451, 433, 403, 385, 361, 331, 263, 235, 221, 209, 167 | + |

“+”, detected; “tr”, trace amount.

Fig. 2.

Structures of mono-MGO adducts of rooibos polyphenols. (A) and (B), MGO-orientin adducts; (C) and (D), MGO-isoorientin adducts; (E) and (F), MGO-vitexin adducts, (G) and (H), MGO-isovitexin adducts.

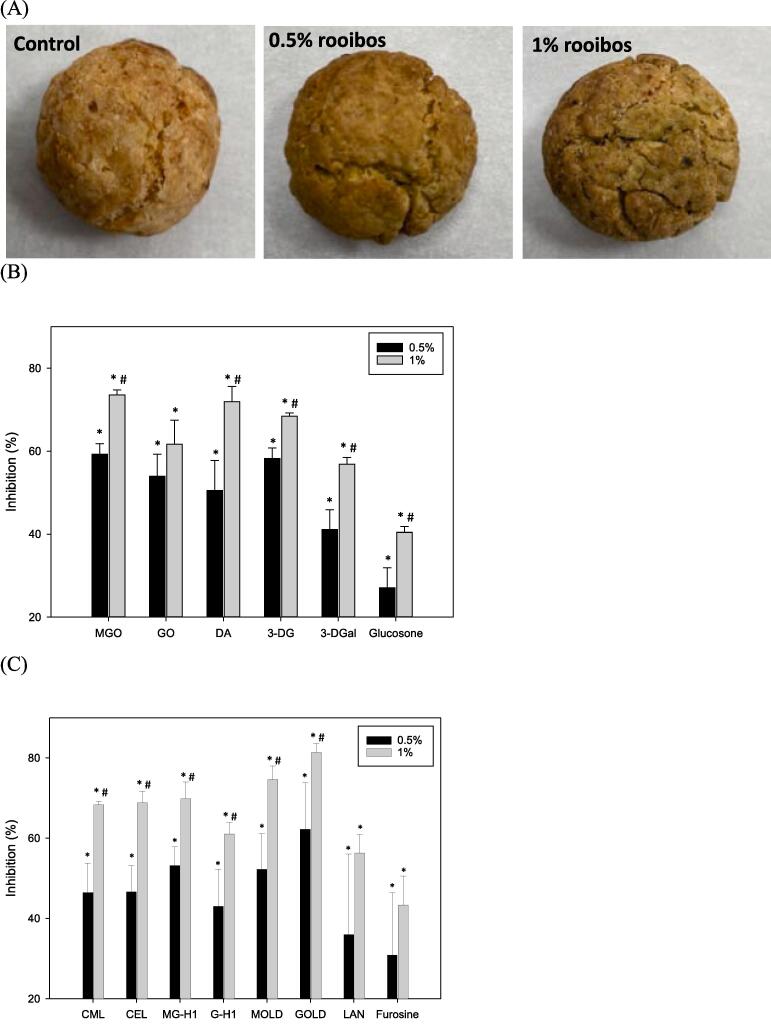

RCS-trapping and antiglycative activities of rooibos in cookies

As the methanol extract of rooibos exerted the highest antiglycative activity in the BSA-glucose model, a cookie model was further conducted to evaluate if rooibos could reduce RCS and AGEs formation in bakery products. When 0.5 % rooibos was added, the values of L*, a*, b* and pH and moisture contents of the cookies did not significantly affected, while the L* value of the cookie was significantly lower than that of the control cookies when fortified with 1 % rooibos (Table S3 and Fig. 3A). Importantly, the contents of RCS in cookies, including methylglyoxal, diacetyl, 3-DG, 3DGal and glucosone, were significantly reduced in a dose-dependent manner when 0.5 % and 1 % rooibos were added (Fig. 3B). Since RCS were the major precursors of AGEs, especially MGO and GO, their corresponding AGEs were also determined in cookies. The results showed that addition of 0.5 and 1 % rooibos significantly reduced both MGO-derived AGEs (CEL, MOLD and MG-H1) and GO-derived AGEs (CML, GOLD and G-H1) with a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). In addition, the indicators of Amadori products (furosine), and heat-induced protein modifications (LAN) were also remarkably reduced regardless of addition of 0.5 or 1 % rooibos. Interestingly, aspalathin, vitexin, isovitexin, orientin, isoorientin, isoquercitrin and rutin were also found in rooibos-fortified cookies and their concentrations are given in Table S4.

Fig. 3.

(A) Representative photo of cookies and contents of (B) RCS and (C) AGEs in rooibos-fortified cookies (n = 3). * p < 0.05 v.s control; # p < 0.05 v.s 0.5 % rooibos-fortified cookies.

Discussion

In this present work, we show that the MGO-trapping activities and antiglycative activities of herbal tea samples were positively associated with their total phenol and flavonoid contents. A similar study indicates that the antiglycative activities of some herbal tea infusions against fluorescent AGEs formation were positively associated with their total polyphenol contents and DPPH scavenging capacities (Gao et al., 2020, Ho et al., 2014). Moreover, inhibitory effects of the extracts of mung bean, black bean, soybean and cowpea against fluorescent AGEs formation were positively associated with their total phenolic contents (Peng, et al., 2008). Taken together, we show that the polyphenol compounds present in herbal tea samples, especially flavonoids, are the important contributors responsible for their RCS-trapping and antiglycative activities.

Our results showed that rooibos exhibited the strongest MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities among the herbal tea samples; therefore, its polyphenol contents were quantified. Isoorientin, aspalathin, and orientin were the most abundant polyphenolic components present in the methanol extract of rooibos, followed by vitexin and isovitexin (Table 2). Previous studies have identified the polyphenol composition of the aqueous extract and the methanol extract of rooibos in which the most abundant polyphenol compounds were aspalathin, orientin and isoorientin (Bramati et al., 2003, Bramati et al., 2002).

In the MGO-trapping experiment, our results showed that O-glycosyl flavonoids present in rooibos, including rutin and isoquercetin, exhibited excellent MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities. The MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities of rutin and isoquercitrin have been reported previously. When MGO was incubated with the major bioactive compounds of Houttuynia cordata, rutin exhibited higher MGO-trapping activity than chlorogenic acid and quercitrin (Yoon & Shim, 2015). Rutin was able to trap MGO at the C-6 and C-8 positions of its A-ring and thereby the corresponding di-MGO adduct of rutin was formed. In addition, isoquercitrin profoundly attenuated fructose-induced glycation of ovalbumin by altering the reactive activities of some glycated sites of ovalbumin (L. Zhang, et al., 2020). Meanwhile, C-glucosyl-flavones of rooibos, including vitexin, isovitexin, orientin and isoorientin, also exhibited MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities. Previously, vitexin and isovitexin identified as the bioactive flavonoids of mung bean also exhibited excellent MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities against fluorescent AGEs formation (Peng, et al., 2008). Moreover, orientin, isoorientin, vitexin and isovitexin are also the bioactive flavonoids present in bamboo leaves and their antiglycative mechanisms have been discussed (Lan, et al., 2020). It is interesting to note that the MGO-trapping activity of isoquercitrin was higher than that of orientin and isoorientin, indicating that the sugar unit located at the A-ring of flavonoids may reduce its MGO-trapping activities. A previous study has shown that the A-ring is the major active site of flavonoids contributing their MGO-trapping efficacy, particularly its 6C- and 8C-positions (Shao, et al., 2014).

In addition to flavonoids, the two major dihydrochalcones present rooibos, aspalathin and nothofagin, were also able to trap MGO. Similar to the chemical structures of aspalathin and nothofagin, phloridzin, a major dihydrochalcone found in apple, and its aglycone, phloretin, were also possessed both excellent MGO- and GO-trapping activities (Shao, et al., 2008). Meanwhile, both phloridzin and sieboldin also exhibited excellent antiglycative activities against fluorescent AGEs formation in a BSA-ribose model (de Bernonville, et al., 2010). When the human umbilical vein endothelial cells were co-treated with phloretin and MGO, phloretin was able to trap MGO in the cell medium to form the corresponding di-MGO adduct and thereby the intracellular level of MGO and AGEs were significantly reduced (Zhou, Gong, & Wang, 2019). Taken together, the excellent MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities of rooibos found in this study were, at least in part, originated from its C-glycosyl dihydroxychalcones, and C- and O-glycosyl flavonoids.

To further discuss the RCS-trapping and antiglycative mechanisms of rooibos, a high resolution qTOF mass spectrometer was used to confirm the molecular formula of the MGO adducts of rooibos polyphenols and characterize their corresponding fragment ions. When the flavonoid of rooibos (orientin, isoorientin, vitexin or isovitexin) was incubated with MGO for 1 h, two corresponding mono-MGO adducts were formed (Fig. 2 and Table 3). These adducts all contain the fragment ion of [M−72−H]−, which indicate that they are the MGO-flavonoid adducts. Previous studies have reported that several flavonoid compounds exhibited excellent MGO-trapping activities and the 6C- and 8C-positions of their A-ring was the primary reactive site to bind MGO (X. M. Li et al., 2014, Shao et al., 2014, Wang and Ho, 2012). Also, it is important to note that the B-ring of flavonoids was able to trap MGO only when the positions of their A-ring were occupied by MGO (G. M. Liu, et al., 2017). In a lysine-glucose model system, quercetin was able to trap MGO to form two tautomers of 8C-MGO conjugates of quercetin and later their chemical structures have also been confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry and mass spectrometry (G. M. Liu, et al., 2017; P. Z. Liu, et al., 2021). According to our current data and these previous findings, proposed chemical structures of the 6C-MGO conjugates of orientin and vitexin and 8C-MGO conjugates of isoorientin and isovitexin are given in Fig. 2.

When aspalathin was incubated with MGO for 1 h, a mono-MGO adduct of aspalathin was found. The fragment ion of m/z 221 [M−162−122−18−H]− of this adduct suggest that MGO was conjugated on the A ring of aspalathin (Figure S8). Similar to the structure of aspalathin, phloridzin, a dihydroxychalcone primarily found in apples, were also able to trap MGO at the 3C– and 5C-positions of its A-ring and thereby the corresponding mono-MGO and di-MGO adducts of phloridzin were generated (Shao et al., 2008, Zhou et al., 2019). Importantly, our current data showed that mono-MGO adducts of orientin, isoorientin and aspalathin were formed when the methanol extract of rooibos was incubated with MGO, while only trace amounts of the mono-MGO adducts of vitexin and isovitexin were found. Since the MGO-trapping activities of vitexin and isovitexin were similar to that from orientin, isoorientin and aspalathin and the concentrations of vitexin and isovitexin in the methanol extract of rooibos were lower than orientin, isoorientin and aspalathin (Table 1), levels of mono-MGO adducts of vitexin and isovitexin might be lower than mono-MGO adducts of orientin, isoorientin and aspalathin when rooibos was incubated with MGO. Altogether, the excellent MGO-trapping and antiglycative activity of rooibos found in this present work are, at least in part, due to its polyphenol compounds, particularly aspalathin, orientin and isoorientin.

Given that a variety of heat-induced toxicants is formed in bakery products due to high temperature processing such as hydroxymethylfurfural, acrylamide, dicarbonyls and AGEs (Hellwig & Henle, 2014), the cookie model was used to evaluate whether fortification of the methanol extract of rooibos could reduce RCS and AGEs formation. It should be noted that the levels of AGEs in bakery products are usually much higher than other food products (Q. Z. Zhang, et al., 2020). Addition of 0.5 or 1 % rooibos significantly reduced the levels of several dicarbonyls in the cookies including MGO, GO, 3-DG, 3-DGal, glucosone and diacetyl. Since MGO and GO are the major precursors of CML, CEL, MG-H1, G-H1, MOLD and GOLD, inhibition of these AGEs were also observed in the rooibos-fortified cookies (Fig. 3). Previously, the GO-trapping and antiglycative activities of different polyphenols were compared in a cookie model. Quercetin possessed the strongest inhibitory capacity against fluorescent AGEs formation in the cookies, followed by naringenin, rosmarinic acid and epicatechin (X. C. Zhang, et al., 2014). Moreover, formation of MGO and fluorescent AGEs in the apple flower-fortified cookies was profoundly reduced in comparison to the control cookies and phlorizin was identified as the major bioactive compound of the apple flower extract responsible for its antiglycative activity (Gao, et al., 2020). These studies measured the fluorescent intensity of ex. 355 nm/em. 405 nm to represent the total AGEs in cookies; however, the major dietary AGEs formed in food products are non-fluorescent, including CML, CEL, MG-H1 and G-H1(Q. Z. Zhang, et al., 2020). As a result, we used LC-MS/MS to quantify these non-fluorescent AGEs instead of measurement of the fluorescent intensity of the cookie samples.

During high temperature processing, dicarbonyls formed from the MR reaction might be trapped by the polyphenols in the rooibos-fortified cookies and thereby formation of AGEs were inhibited. A recent study has successfully identified the mono- and di-MGO adducts of quercetin in the cookies after incorporation of 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1 % quercetin in the dough suggesting that polyphenols were still able to trap RCS during thermal processing (P. Z. Liu, et al., 2021). Although our current study has successfully identified the occurrence of the mono-MGO adducts of orientin, isoorientin and aspalathin in the PBS solution when the methanol extract of rooibos was incubated with MGO, these mono-MGO adducts failed to be detected in the rooibos-fortified cookies (data not shown). At the same mass-based fortification level, formation of the polyphenol-MGO adducts in the rooibos-fortified cookie might be much lower than that from the cookie fortified with the pure compounds of polyphenols. Also, other components present in the extract of rooibos may also interfere or participate the reactions between polyphenols and RCS to form new adducts during thermal processing. Meanwhile, pH values, moisture contents and color of the cookies were also measured to evaluate the quality of cookies. Fortification of rooibos did not significantly affect pH values and moisture contents of the cookies, while the L* value of the 1 % rooibos-fortified cookies was significantly lower than that of the control cookies (Table S3). These results suggest that the cookies became darker when fortified with 1 % rooibos. Similar to our results, L*, a* and b* values of the cookies were significantly affected when 1, 2.5 and 5 % of the apple flower extract were incorporated in the dough (Gao, et al., 2020). Besides the edible flowers, fortification of 0.25 % quercetin, chlorogenic acid, and rosmarinic acid significantly decreased redness of the cookies, while their yellowness increased. The new colorants might be formed from thermal transformation of polyphenols or from the reactions between polyphenols and nutritional components in cookies (X. C. Zhang, et al., 2014). Collectively, our data suggest that fortification of 0.5 % rooibos might be a promising approach to reduce the levels of dicarbonyls and AGEs in the cookies without adversely affecting its quality. However, future research is still warranted to confirm the sensory attributes and consumer acceptance of these rooibos-fortified cookies.

Conclusions

In the present study, our data showed that the MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities of herbal tea samples were positively associated with their total phenolic and flavonoid contents. Among the herbal tea samples, rooibos exhibited the strongest MGO-trapping and antiglycative activities. Several MGO-polyphenol adducts were successfully identified when the methanol extract of rooibos was incubated with MGO, indicating that aspalathin, orientin and isoorientin were the major bioactive compounds responsible its MGO-trapping activities. Moreover, when fortified with rooibos, both dicarbonyls and non-fluorescent AGEs in the cookie were significantly reduced without adversely affecting its quality. Altogether, our current findings suggest that fortification of rooibos may serve as a promising processing approach to inhibit formation of dicarbonyls and AGEs in thermally processed foods, particularly bakery products.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (109–2314-B-038–063, 110–2320-B-038–045, 111–2314-B-038–041-MY3, 110–2813-C-038–007-B), the Ministry of Education, Taiwan (DP2-111–21121-01-O-08–02) and Taipei Medical University, Taiwan (TMU107-AE1-B14).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yen-Tung Chen: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft. You-Yu Lin: Investigation, Software. Min-Hsiung Pan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Chi-Tang Ho: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Wei-Lun Hung: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Yi-Ju Chen (Core facility, Taipei Medical University) for her excellent technical support of LC-qTOF-MS.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100515.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bramati L., Aquilano F., Pietta P. Unfermented rooibos tea: Quantitative characterization of flavonoids by HPLC-UV and determination of the total antioxidant activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(25):7472–7474. doi: 10.1021/jf0347721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramati L., Minoggio M., Gardana C., Simonetti P., Mauri P., Pietta P. Quantitative characterization of flavonoid compounds in Rooibos tea (Aspalathus linearis) by LC-UV/DAD. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(20):5513–5519. doi: 10.1021/jf025697h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri J., Bains Y., Guha S., Kahn A., Hall D., Bose N.…Kapahi P. The role of advanced glycation end products in aging and metabolic diseases: Bridging association and causality. Cell Metabolism. 2018;28(3):337–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.J., Smith J.S. Determination of advanced glycation endproducts in cooked meat products. Food Chemistry. 2015;168:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.Y., Yen G.C. Antioxidant activity and free radical-scavenging capacity of extracts from guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves. Food Chemistry. 2007;101(2):686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Bernonville T.D., Guyot S., Paulin J.P., Gaucher M., Loufrani L., Henrion D.…Brisset M.N. Dihydrochalcones: Implication in resistance to oxidative stress and bioactivities against advanced glycation end-products and vasoconstriction. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(4):443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.Y., Sun Y., Li L., Zhou Q., Wang M.F. The antiglycative effect of apple flowers in fructose/glucose-BSA models and cookies. Food Chemistry. 2020;330 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig M., Gensberger-Reigl S., Henle T., Pischetsrieder M. Food-derived 1,2-dicarbonyl compounds and their role in diseases. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2018;49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig M., Henle T. Baking, Ageing, Diabetes: A Short History of the Maillard Reaction. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2014;53(39):10316–10329. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S.C., Chang P.W., Tong H.T., Yu P.Y. Inhibition of fluorescent advanced glycation end-products and N-carboxymethyllysine formation by several floral herbal infusions. International Journal of Food Properties. 2014;17(3):617–628. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2012.654566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh M.C., Shen Y.J., Kuo Y.H., Hwang L.S. Antioxidative activity and active components of longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) flower extracts. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008;56(16):7010–7016. doi: 10.1021/jf801155j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaraj E.J., Lim Y.Y., Choo W.S. Extraction methods of butterfly pea (Clitoria ternatea) flower and biological activities of its phytochemicals. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2021;58(6):2054–2067. doi: 10.1007/s13197-020-04745-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuz S., Joubert E., Waldmann K.H., Ternes W. Aspalathin, a flavonoid in Aspalathus linearis (rooibos), is absorbed by pig intestine as a C-glycoside. Nutrition Research. 2008;28(10):690–701. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan M.Y., Li H.M., Tao G., Lin J., Lu M.W., Yan R.A., Huang J.Q. Effects of four bamboo derived flavonoids on advanced glycation end products formation in vitro. Journal of Functional Foods. 2020;71 doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.M., Zheng T.S., Sang S.M., Lv L.S. Quercetin inhibits advanced glycation end product formation by trapping methylglyoxal and glyoxal. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2014;62(50):12152–12158. doi: 10.1021/jf504132x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.F., Yang P.Y., Luo Y.H., Gao B.Y., Sun J.H., Lu W.Y.…Yu L.L.L. Chemical compositions of chrysanthemum teas and their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Food Chemistry. 2019;286:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.M., Xia Q.Q., Lu Y.L., Zheng T.S., Sang S.M., Lv L.S. Influence of quercetin and its methylglyoxal adducts on the formation of alpha-dicarbonyl compounds in a lysine/glucose model system. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2017;65(10):2233–2239. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b05811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.Z., Yin Z., Chen M., Huang C.H., Wu Z.H., Huang J.Q.…Zheng J. Cytotoxicity of adducts formed between quercetin and methylglyoxal in PC-12 cells. Food Chemistry. 2021;352 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maasen K., Scheijen J.L.J.M., Opperhuizen A., Stehouwer C.D.A., Van Greevenbroek M.M., Schalkwijk C.G. Quantification of dicarbonyl compounds in commonly consumed foods and drinks; presentation of a food composition database for dicarbonyls. Food Chemistry. 2021;339 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmini E., Prema K., Geetha B.V., Rani M.U. Comparative study on composition and antioxidant properties of mint and black tea extract. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2008;43(10):1887–1895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2008.01782.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X.F., Zheng Z.P., Cheng K.W., Shan F., Ren G.X., Chen F., Wang M.F. Inhibitory effect of mung bean extract and its constituents vitexin and isovitexin on the formation of advanced glycation endproducts. Food Chemistry. 2008;106(2):475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quettier-Deleu C., Gressier B., Vasseur J., Dine T., Brunet C., Luyckx M.…Trotin F. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) hulls and flour. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2000;72(1–2):35–42. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy R., Yan S.F., Schmidt A.M. Methylglyoxal comes of AGE. Cell. 2006;124(2):258–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang S., Shao X., Bai N., Lo C.Y., Yang C.S., Ho C.T. Tea Polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate: A new trapping agent of reactive dicarbonyl species. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2007;20(12):1862–1870. doi: 10.1021/tx700190s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao X., Bai N.S., He K., Ho C.T., Yang C.S., Sang S.M. Apple polyphenols, phloretin and phloridzin: New trapping agents of reactive dicarbonyl species. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2008;21(10):2042–2050. doi: 10.1021/tx800227v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao X., Chen H.D., Zhu Y.D., Sedighi R., Ho C.T., Sang S.M. Essential structural requirements and additive effects for flavonoids to scavenge methylglyoxal. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2014;62(14):3202–3210. doi: 10.1021/jf500204s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L.M., Shi X.L., Yu L.H., Zhu J., Ma R., Yang X.B. Chemical composition and hepatoprotective effects of polyphenol-rich extract from Houttuynia cordata tea. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2012;60(18):4641–4648. doi: 10.1021/jf3008376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe J.D., Joubert E., Manley M., de Beer D., Malherbe C.J., Gelderblom W.C.A. In vitro hepatic biotransformation of aspalathin and nothofagin, dihydrochalcones of rooibos (Aspalathus linearis), and assessment of metabolite antioxidant activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(4):2214–2220. doi: 10.1021/jf903917a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen K.C.W., Linkens A.M.A., Wetzels S.M.W., Wouters K., Vanmierlo T., van de Waarenburg M.P.H.…Schalkwijk C.G. Dietary advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) increase their concentration in plasma and tissues, result in inflammation and modulate gut microbial composition in mice; evidence for reversibility. Food Research International. 2021;147 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Ho C.T. Flavour chemistry of methylglyoxal and glyoxal. Chemical Society Reviews. 2012;41(11):4140–4149. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35025d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.Y., Yang K.M., Chiang P.Y. Roselle anthocyanins: Antioxidant properties and stability to heat and pH. Molecules. 2018;23(6) doi: 10.3390/molecules23061357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.R., Shim S.M. Inhibitory effect of polyphenols in Houttuynia cordata on advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) by trapping methylglyoxal. Lwt-Food Science and Technology. 2015;61(1):158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Xu L., Tu Z.C., Wang H.G., Luo J., Ma T.X. Mechanisms of isoquercitrin attenuates ovalbumin glycation: Investigation by spectroscopy, spectrometry and molecular docking. Food Chemistry. 2020;309 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.Z., Wang Y.B., Fu L.L. Dietary advanced glycation end-products: Perspectives linking food processing with health implications. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2020;19(5):2559–2587. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.C., Chen F., Wang M.F. Antioxidant and Antiglycation Activity of Selected Dietary Polyphenols in a Cookie Model. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2014;62(7) doi: 10.1021/jf4045827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q., Cheng K.W., Xiao J.B., Wang M.F. The multifunctional roles of flavonoids against the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and AGEs-induced harmful effects. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2020;103:333–347. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q., Gong J., Wang M.F. Phloretin and its methylglyoxal adduct: Implications against advanced glycation end products-induced inflammation in endothelial cells. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2019;129:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.D., Snooks H., Sang S.M. Complexity of advanced glycation end products in foods: Where are we now? Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2018;66(6):1325–1329. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.