Abstract

The harmful effects of pesticide misuse on human health and the environment have become evident; so, this study aimed to monitor pesticide residues in soils of vegetable fields collected from the Eastern Nile Delta region, Egypt and to assess the potential health risks associated with them. Pesticide residues were determined using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Obtained results revealed that 100% of collected samples were contaminated with pesticides; residues of 33 compounds were detected in analyzed samples belonging to different chemical groups. Most detected pesticides (44%) were non-persistent and 40% were moderately persistent. While 1313% and 3% were persistent and very persistent compounds, respectively. Also, 36.7% and 30% of samples have two and three pesticides. Chlorpyrifos and propamocarb were the most dominant compounds that had widespread use across the study area. The number of detected pesticides per crop ranged from 1 to 16 (potato soil), followed by cucumber and tomato (13 pesticides), while one compound was detected in sweet potato soil. Soil organic matter content had a positive correlation with the total concentration of pesticide residues; however, no correlations were found with soil clay, pH and electrical conductivity contents. The human health risks of pesticides in the study soils were within acceptable levels. However, more attention should be paid in the future to decreasing the pesticide load and take place pesticide residue monitoring on vegetable soils.

Keywords: Contamination, Health risk, Pesticide residues, Survey, Vegetable field soil

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Insecticides and fungicides were the most detected pesticides in vegetable soils.

-

•

The most widely detected pesticide in vegetable soils was Chlorpyrifos.

-

•

Potato and cucumber and tomato fields had a high number of pesticide residues.

-

•

Soil organic matter was correlated with the total content of pesticides in soils.

-

•

Human health risk of pesticides in vegetable soils was within the acceptable limit.

1. Introduction

Pesticide use is increasing as agricultural productivity expands each year to meet population growth. Like many developing countries, pesticides are applied extensively in Egypt to increase the crop yield per hectare [1]. In Egypt, around 11 000 tons of pesticide active ingredients had been utilized in 2018 as indicated by Agricultural Pesticides Council [2]. Egyptian farmers apply pesticides with greater numbers of applications, higher application rates, and shorter application intervals [3]. Despite the high benefits of pesticides, their excessive use leads to contamination of the environment as well as foods, which may create potential risks to human health [4], [5].

Although large amounts of pesticides are used every year and a greater part enters the agricultural soil to form short- or long-term residues, there is a scarcity of soil monitoring for pesticides currently in use. Pesticide application rates are currently exceeding what is required for efficient crop protection globally [6]. This may increase soil pollution.

The fate and behavior of pesticides in soil depend on the physicochemical properties of the pesticide, the soil properties, and the surrounding environmental conditions [7], [8]. Moreover, the rate, frequency and pathway of pesticide application could determine the formation of residues in the soil [9]. Some recent data revealed that high pesticide residues may remain in the agricultural soils after their application [8], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14].

Agricultural soils might be polluted with pesticide residues through direct exposure by applying pesticides to soils or indirectly by runoff from treated plant surfaces or air transportation and disposal [15]. Also, pesticides may reach the soil through artificial irrigation wastewaters [16]. Pesticide residues have become a major soil threat, they cause land degradation potential [17]. These residues undergo a variety of transformations that may yield toxic metabolites [18]. Moreover, they could hinder the absorption of certain minerals by plants, affect soil microbial activity, migrate into the surface, and ground waters, or enter the food chain directly through absorption into plants, thus resulting in serious environmental and human health risks [19], [20]. Therefore, the monitoring of pesticide residues in the environment is very important because it provides very worthy information on the actual level of soil contamination and environmental risk resulting from their application [21].

Also, the assessment of human health risks for pesticides aims to explain if the pesticide will pose an adverse health risk to humans and describe specific types and forms of toxic risks such as neurotoxicity and carcinogenicity [22]. A high level of pesticide pollution was found in vegetable soils cultivated with tomato, cucumber, eggplant and zucchini in the Jordan Valley [23], [24]. In Egypt, many studies have investigated the pesticide residues in the edible parts of vegetables, but few have studied the pesticide residues in the soils used for vegetable production [1], [3], [25].

Unfortunately, very little information is available on the contamination and human health risks of pesticides in agricultural soils, especially in vegetable soils at the national and international levels. Egyptian exports of vegetables have achieved reasonable growth last few years. Egypt is self-sufficient in vegetable production, and it has managed to open new markets for Egyptian crops, especially in the European Union, China and East Asian countries. Therefore, this study was providing the first evidence of the degree of pesticide pollution in vegetable fields in Egypt. The findings can be useful to support the practices of pesticide pollution management and to prevent further deterioration of the vegetable fields.

The objectives of this study were: (1) survey and characterize the pesticide residues in the soil of vegetable fields in the Eastern Nile Delta region as a representative of Egypt; (2) determine the relationship between pesticide residues and soil properties, and (3) assess the potential health risks for humans related with the exposure to pesticides in the soil of vegetable fields.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

The Eastern Nile Delta region is one of the most promising regions of sustainable development in Egypt. The study area extends between latitudes 30 °35 ´ and 31 °29 ´ N and longitudes 31 °18 ´and 32 °04 ´E (Fig. 1). It includes Damietta, Dakahlia and El-Sharkia Governorates. It has a warm and dry summer and little rainy winter with all-out yearly precipitation is around 167 mm each year that falls principally between October and March. The average yearly temperature is around 24–35 °C in summer and 8–20 °C in winter. The Eastern Nile Delta region is described by abundant water resources. However, a few parts had moderate-to-low water availability during the summer months. Most rural soils are irrigated with fresh water from the Damietta Branch of the Nile River. Most of the new area is supplied by surface water, but there are also a few areas based on wastewater reuse [26], [27]. The main crops in this area are rice, wheat, vegetables (such as tomato, potato, eggplant, pepper and cucurbits), citrus, grape and mango. About 134 473 ha of land in the Eastern Nile Delta was used to produce vegetables in 2017, this equivalent to 17.7% of all the absolute area used for vegetable production in Egypt. The vegetables grown under high tunnels in the Eastern Nile Delta were depended on areas planted in Dakahlia (32 534 tunnels), where cucumber is the main vegetable followed by pepper and tomato [28].

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area and sampling sites of pesticides in vegetable soil in the Eastern Nile Delta.

2.2. Soil sample collection

Soil samples were randomly collected from 60 different sites that covered fifteen districts namely New Salhia, Qasasin Alsharq, Fakoos, Abu Kabir, Awlad Saqr, Bani Ebeid, Al-Sembelawaan, Sherbin, Elzarka, Fariskur, Talkha, Belkas, Kafr El-Batteikh, Kafr Saad, Mansoura (Table S1). These districts are the major vegetable-growing areas across the study region during the autumn and winter seasons. The site of the sample was determined with the help of the Global Positioning System (GPS) on the spot (Fig. 1). Soil samples were collected from selected vegetable fields (55 sites) and greenhouses (5 sites) from the upper layer (0–25 cm), which is the layer generally related to the presence of pesticides [10]. Samples were taken in late October and early November 2020. Soil samples were collected using an auger and a stainless-steel scoop. Five samples from each sampling field were collected and well mixed after removing extraneous objects such as stones, leaves, pebbles, gravel, and roots to form a composite sample. Each sample was kept in a labeled plastic bag and transported to the laboratory in iceboxes. Each sample was divided into two parts: 1st for analysis of pesticide residues that were kept in the refrigerator at − 20 °C until analysis; 2nd for soil physical and chemical analyses that were dried, homogenized, slowly sieved samples (2 mm) and stored in the dark at 4 °C before analysis.

2.3. Physicochemical properties of soils

The physicochemical characteristics of soils (clay content, organic matter (OM) content, pH, and electrical conductivity (EC)) were analyzed following the standard methods [29], [30]. The soil texture varied from clay to sandy soils, the soil pH was in the 7.10–8.70 range, the organic matter (OM) contents were between 0.42% and 2.94%, and the soil EC was in the 0.98–5.02dS m−1 range. These findings indicate a diverse range of physical-chemical characteristics of the sampling sites. The descriptive statistics analyses of soil parameters (clay, OM, pH and EC) are presented in Table S1 (Supplementary material).

2.4. Analysis of pesticides residues in soil samples

2.4.1. Extraction and clean-up

The pesticides belonging to different classes were extracted and clean-up by using the QuEChERS method (ILNAS-EN 15 662) [31]. All used chemicals were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (USA). QuEChERS kits were purchased from Agilent Technologies (USA). Deionized water was supplied by the Millipore water purification system (Milli-Q). About 10 g of each soil sample was weighed into 50 ml centrifuge tube; 10 ml of acetic acid 1% was added and shaken for 2 min then ultrasonic for 1 min. Ten ml of acetonitrile was added to the tube and shaken vigorously for 2 min, then centrifuged for 5 min at 4000 rpm. An aliquot of 6 ml of the acetonitrile phase was moved into 10 ml centrifuge tube containing 1 g magnesium sulfate and 200 mg PSA, shaken energetically for 30 s and centrifuged (3000 rpm) for 2 min. The supernatant was evaporated to dryness then reconstituted in 2 ml acetone: n-hexane (1:9 v/v) then the mixture was subjected to ultra-sonication for 30 s then filtered into a glass vial. The extract is analyzed using LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS.

2.4.2. Quality assurance

The analytical methods and instruments were fully validated as part of a lab-quality assurance system and were audited and qualified by the Centre for Metrology and Accreditation, Finnish Accreditation Service (FINAS), Helsinki, Finland. This system is accredited to as ISO/IEC 17 025:2017 standards. The mean recoveries of the selected pesticides in soil samples differed between 70% and 120%. The repeatability communicated as relative standard deviation (RSD) was < 20%, while the limits of quantification (LOQ) were from 0.01 to 0.05 mg kg−1 for soil.

2.5. GC-MS/MS analysis

Samples analyses were carried out using an Agilent 7890 A gas chromatography system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a Model 7000B triple quadrupole Agilent mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The column was DB-35MS Ultra inert capillary column (35% Phenyl-65% dimethylpolysiloxane, 30 m length × 0.18 mm i.d. × 0.25 µm film thicknesses, Agilent Technologies). The oven temperature was initially held at 70 °C for 1.3 min, and then ramped at 70 °C /min up to 150 °C, then at 12 °C /min up to 270 °C, and finally at 18 °C /min up to 310 °C that was held for 6.3 min, leading to a total run time of 21 min [32]. The inlet temperature was 250 °C and the injection volume was 1 µL injected in splitless mode. Nitrogen was used as the collision gas and helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 0.7 ml/min. Electron impact mode was used and the ionization energy was 70 eV, the ion source temperature was 320 °C, the GC–MS/MS interface temperature was 320 °C and the Quadrapole temperature was 180 °C. Mass Hunter software (Version: B.07.01/Build 7.1.524.0) was used for instrument control and data acquisition/processing. Both the retention times and ion ratios of the quantify to qualifiers were performed as the acceptance criteria for correct peak identification.

2.6. LC-MS/MS analysis

The LC-MS/MS system that consisted of an Agilent 1200 Series HPLC linked to an API 4000 Qtrap MS/MS from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA) was used. The separation was achieved on an Agilent C18 column ZORBAX Eclipse XDB with 150 mm length, 4.6 mm i.d. and 5.0 µm particle sizes. The column temperature was 40 °C and the injection volume was 5 µL. The separation was performed using gradient elution between two components, A: 10 mM ammonium format solution in methanol: water (1:9 v/v) at pH = 4 and B: LC-MS grade Methanol. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min starting with 100% of component A and gradually changing to 5% A (95% B) over 6 min that was kept constant for 17 min at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. After 23 min run time, 2 min of post-time followed using the initial 100% of A at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The MS/MS analysis was conducted using electrospray ionization (ESI) in the positive ion mode with multiple reactions monitoring mode (MRM). One MRM was used for quantification, while the other was used for verification. According to the manufacturer's specifications, nitrogen was used as a nebulizer, heater, curtain and collision gas. Settings were as follows: temperature, 450 °C; curtain gas, 25 psi; ion spray voltage, 5000 V; collision gas, medium; ion source gas 2, 40 psi, and ion source gas 1, 40 psi. Analyst software 1.6 was used for control, data acquisition and data processing.

2.7. Health risk assessment

The non-carcinogenic health risks of pesticide residues in soils were estimated according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency [33]. Since the slope factors of detected pesticides are not accessible in the method; the carcinogenic risk is negligible in this study. These health risks of adults and children were calculated through ingestion (ing), dermal (derm) and inhalation (inh) routes. The average daily intakes (ADIs) for each pesticide were estimated using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Where Cs is the concentration of pesticide in the soil (mg kg−1). The other exposure parameters and their values, symbols and units are provided in Table S2 in the supplementary material.

The non-carcinogenic risks were evaluated using hazard quotient (HQ), and hazard index (HI). The HQ value of each pesticide for different exposure pathways is defined as Eq. (4):

| (4) |

Where RfD (mg kg−1 day−1) is the reference dose of a pesticide that is listed in Table S3 in the supplementary material.

The HI is the summation of multiple exposure pathways of HQ for each pesticide:

| (5) |

If the obtained HQ or HI values are less than 1, there is no non-carcinogenic health risk. If these values exceed1, there may be a significant risk to human health.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The concentration of pesticides equal to or above the respective limit of detection (LOD) was considered in the data analysis. The concentrations below LOD were set as zero. Descriptive statistics, namely, minimum (Min), mean, maximum (Max), median (Me), total, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV) related to the concentrations of pesticides were studied to discover the data. The relationships between the concentration of pesticides and soil properties (clay, pH, OM, and EC) were calculated using Pearson correlation. Multiple linear regression models were used to correlate the pesticides concentrations and soil properties. MSTAT-C, Microsoft Excel®(2013), and Number Cruncher Statistical System (NCSS) statistical software were used for the data analyses. Maps were prepared with ArcGIS (version 10).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Classification of detected pesticides

Out of thirty-three pesticides that were identified in the study soils 39.39% of detected pesticides (13 out of 33) belonged to insecticides (e.g., chlorpyrifos, acetamiprid and methomyl), 36.36% (12 out of 33) represented fungicides (e.g., azoxystrobin, propamocarb and penconazole), 15.15% belonged to herbicides (e.g., pendimethalin and thiobencarb) and 6.06% represented Acaricides (abamectin and propargite), while the nematicide carbofuran was found in 3.03% of detected pesticides (Fig. S1 and Table S4). The outcomes showed a wide scope of pesticides for various groups. The insecticides and fungicides were the most generally used in vegetable protection since they are applied more frequently depending on weather conditions and crop needs throughout the growth period. Similar findings were stated by Hathout et al. [34] who reported 28 pesticides in Egyptian agricultural soil, 14 of which were insecticides, 11 fungicides, and 3 herbicides. Moreover, Silva et al. [12] found that the fungicide residues were common in agricultural soil of European Union countries.

The identified pesticides were grouped under various toxicity classes by the World Health Organization (WHO)[35] (Fig. S1 and Table S4). About 12.12% (4 out of 33) of detected pesticides were considered highly hazardous (Ib) to human health, 27.27% belonged to class II (moderately hazardous) and 21.21% belonged to class III (slightly hazardous), while 39.39% of pesticides under toxicity class U (unlikely to pose an acute hazard in normal use). Therefore, attention is needed to promote safe pesticide use among farmers, and the sale and use of highly hazardous pesticides should be limited.

The majority of the detected pesticides (44%) were non-persistent (DT50 < 30 days), while 40% were moderately persistent compounds (DT50: 30–100 days); persistent (DT50:100 –365 days), and very persistent compounds (DT50 > 365 days) represented 13% and 3% of detected compounds, respectively (Fig. S1 and Table S4). Similarly, in EU agricultural soils, the majority of detected pesticide residues were non-persistent (DT50 < 30 days) or moderately persistent (DT50: 30–100 days) compounds, while 16% and 23% of the residues were persistent (DT50: 100–365 days) and highly persistent (DT50 > 365 days) compounds, respectively [12].

3.2. Assessment of pesticide residues in soil samples

3.2.1. Number of pesticide residues

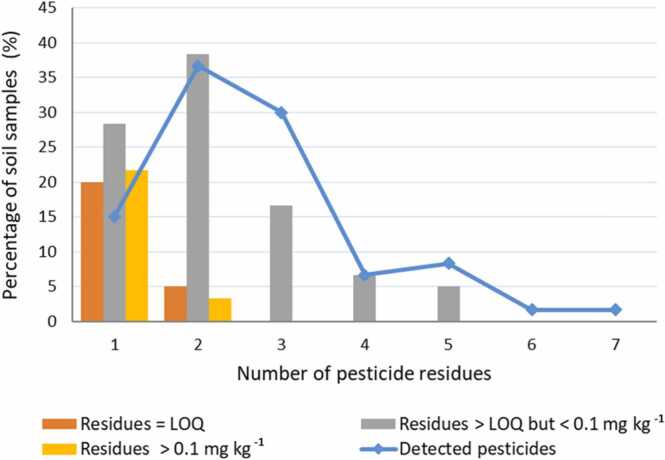

The appraisal of pesticide residues in collected soil samples revealed the presence of a variety of pesticide combinations (Fig. 2). The number of detected pesticides per soil sample varied from 1 to 7. In 15% of the collected samples, a single pesticide residue was quantified, while most of the studied soils contained mixtures of more than two pesticides. 36.7% and 30% of samples have two and three compounds, respectively. Also, results show a predominance of mixtures of moderate residues in soil (4−5) relative to mixtures of large numbers of residues (6−7). Nearly 6.7% and 8.3% of samples were contaminated with four and five pesticide residues, respectively. Residues of 6 and 7 compounds were found in one sample (1.7%), which was lower than that previously reported for soils collected in arable lands [10], [36], [37]. The use of the threshold values (0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 mg kg–1) can offer a more important explanation of the pesticide pollution in agricultural soil [10]. About two-thirds of samples (66.7%) contained at least two pesticides at levels exceeding LOQ but ˂ 0.1 mg kg–1. In 22.3% of samples, at least one pesticide was present at ≥ 0.1 mg kg–1 (Table 1). The number of detected compounds varied significantly with vegetable fields, farming practices, and soil depths [13]. The accumulation of pesticide residue mixtures in agricultural soil constitutes mostly toxic chemicals, which is a global environmental issue that must be considered in the assessment of agricultural production sustainability. Multiple pesticide residues could be due to long-persistence pesticides in the soil (Table S4) or cross-contamination during crop processing. Moreover, pesticide levels in the soil are influenced by pesticide levels in irrigation water. The pesticide levels in River Nile water vary depending on the kind of irrigation water and the level of pollution [38].

Fig. 2.

Abundances of pesticides detected and exceeding the threshold 0.1 mg kg−1 in the analyzed soil samples.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistical data of individual pesticide concentrations (mg kg−1) in study soils.

| Pesticides | Min | Mean | Median | Max | Total | SDa | CVb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abamectin | LOQ | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.038 | 0.008 | 118.9 |

| Acetamiprid | LOQ | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.020 | 0.113 | 0.005 | 46.1 |

| Atrazine | 0.01 | 0.016 | 0.018 | 0.020 | 0.078 | 0.005 | 33.2 |

| Azoxystrobin | LOQ | 0.018 | 0.015 | 0.040 | 0.144 | 0.012 | 68.2 |

| Benalaxy | LOQ | 0.010 | 0.01 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 0.014 | 141.4 |

| Carbendazim | LOQ | 0.018 | 0.02 | 0.030 | 0.090 | 0.013 | 72.4 |

| Carbofuran | 0.018 | 0.021 | 0.02 | 0.030 | 0.107 | 0.005 | 22.8 |

| Chlorpyrifos | LOQ | 0.122 | 0.11 | 0.240 | 1.944 | 0.072 | 59.1 |

| Chlorpyrifos‐methyl | 0.01 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.020 | 0.030 | 0.007 | 47.1 |

| Cypermethrin | 0.020 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.040 | 0.11 | 0.010 | 34.8 |

| Difenoconazole | 0.028 | 0.043 | 0.04 | 0.060 | 0.128 | 0.016 | 37.9 |

| Dimethoate | LOQ | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.086 | 0.008 | 48.4 |

| Dimethomorph | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.01 | 0.020 | 0.050 | 0.005 | 40.0 |

| Emamectin benzoate | 0.01 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.020 | 0.030 | 0.007 | 47.1 |

| Fluopicolide | 0.086 | 0.098 | 0.098 | 0.110 | 0.294 | 0.012 | 12.3 |

| Imidacloprid | LOQ | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.030 | 0.072 | 0.011 | 74.4 |

| Lambda‐cyhalothrin | 0.04 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.048 | 0.088 | 0.006 | 12.9 |

| Linuron | 0.016 | 0.027 | 0.03 | 0.034 | 0.080 | 0.009 | 35.4 |

| Lufenuron | LOQ | 0.007 | 0.01 | 0.010 | 0.020 | 0.006 | 86.6 |

| Malathion | LOQ | 0.009 | 0.0085 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 141.4 |

| Mandipropamid | LOQ | 0.050 | 0.05 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.071 | 141.4 |

| Metalaxyl | 0.018 | 0.030 | 0.0265 | 0.050 | 0.181 | 0.012 | 41.2 |

| Methamidophos | LOQ | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.048 | 0.008 | 66.7 |

| Methomyl | 0.046 | 0.073 | 0.065 | 0.130 | 0.731 | 0.029 | 39.7 |

| Oxyfluorfen | LOQ | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.034 | 141.4 |

| Penconazole | LOQ | 0.012 | 0.01 | 0.030 | 0.086 | 0.011 | 87.9 |

| Pendimethalin | LOQ | 0.067 | 0.05 | 0.180 | 0.606 | 0.048 | 71.5 |

| Propamocarb | 0.010 | 0.152 | 0.2 | 0.300 | 1.216 | 0.116 | 76.2 |

| Propargite | 0.066 | 0.072 | 0.072 | 0.078 | 0.144 | 0.009 | 11.8 |

| Pyraclostrobin | LOQ | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.021 | 141.4 |

| Thiamethoxam | LOQ | 0.022 | 0.02 | 0.030 | 0.108 | 0.006 | 25.7 |

| Thiram | LOQ | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 141.4 |

| Thiobencarb | LOQ | 0.025 | 0.02 | 0.048 | 0.196 | 0.012 | 49.7 |

LOQ: the limits of quantification.

SD: standard deviation.

CV: coefficient of variation.

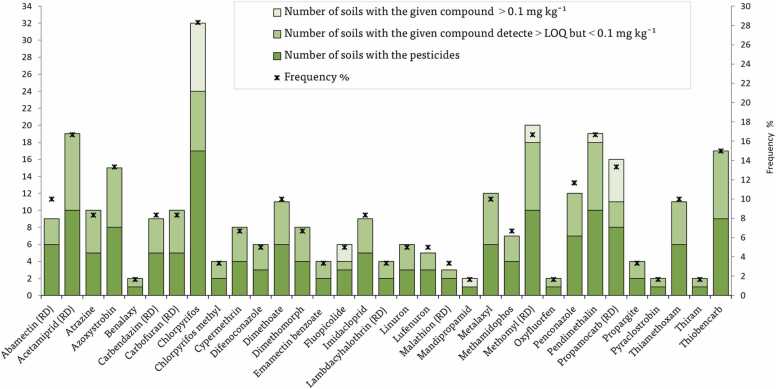

3.3. Abundances of individual pesticides in soils

The entireties of vegetable soil samples gathered from across the Eastern Nile Delta were observed to be polluted with pesticide residues at different levels (Fig. 3). The banned pesticides in the Egyptian market at the time of samplings such as atrazine, carbendazim, carbofuran, methamidophos and propargite were found in 5, 5, 5, 4 and 2 of the analyzed samples, respectively, covering a total of 8.33%, 8.33%, 8.33%, 6.67% and 3.33%. Their presence in the soils of the examined region is because of unlawful recent use. The most widely detect pesticides in soil samples (shown in >10% of samples) were chlorpyrifos (28.33%), acetamiprid (16.67%), methomyl (16.67%), pendimethalin (16.67%), thiobencarb (15%), azoxystrobin (13.33%), propamocarb (13.33%) and penconazole (11.67%). Chlorpyrifos residues were detected in 17 samples at a high recurrence in vegetable soils. The data clearly demonstrated that the frequency of chlorpyrifos in soil samples was higher than that found by Hathout et al. [34], who found chlorpyrifos in 7.5% of samples collected from Egyptian agricultural soils. The significant occurrence of chlorpyrifos could be attributed to its high annual use and relevance for the crops grown on the sites, as chlorpyrifos is a non-soluble, very lipophilic chemical that is strongly sorbing in soils [16], [33]. Likewise, chlorpyrifos followed by propamocarb had a high number of soil samples at levels ≥ 0.1 mg kg–1 (8 and 5, respectively). The low frequency of detection of acetamiprid, methomyl, pendimethalin and thiobencarb may partially be explained by their higher samples with LOQ (less than 0.01 mg kg–1) hampering the detection of concentrations below this limit.

Fig. 3.

Abundances of individual pesticides detected in analyzed samples.

3.4. Descriptive statistical analyses of pesticide residues

Descriptive statistical data of the pesticide residues detected in the soil samples collected from the Eastern Nile Delta are summarized in Table 1. Among all pesticides, the highest average and median concentrations were determined for propamocarb (0.152 mg kg−1; 0.20 mg kg−1, respectively) and Chlorpyrifos (0.122 mg kg−1; 0.11 mg kg−1, respectively), while thiram, abamectin, lufenuron and malathion have the lowest mean values of 0.005, 0.006, 0.007 and 0.009 mg kg−1, respectively, with a median concentration of 0.005, 0.005, 0.010 and 0.009 mg kg−1, respectively. Moreover, chlorpyrifos and propamocarb contributed the most to the total pesticide contents in soils 1.944 and 1.216 mg kg−1, respectively, with a maximum content of 0.240 and 0.300 mg kg−1, respectively. Although high concentrations of propamocarb were detected, it is known that it has a short half-life in soil, with half-lives of 1–30 days [2], the high concentration could be attributed to recent pesticide spraying in the vegetable fields.

According to the detection frequencies and concentrations, chlorpyrifos and propamocarb were the most dominant pesticides that had widespread use across the study area. Chlorpyrifos is one of the most generally utilized organophosphorus insecticides in Egypt; it was prescribed to control a wide scope of insects (belonging to Coleoptera, Diptera, Homoptera, and Lepidoptera) in soil or foliage in over 100 crops [39]. It is a very persistent compound (DT50 > 386 days) and has a high soil absorption coefficient (average Koc = 8498 ml g−1), low water solubility (1.4 mg L−1), and medium vapor pressure (2.7 × 10−3 Pa at 25 °C) [40]. The undeniable degree of chlorpyrifos could be ascribed to high application and recurrence as this active substance forms a major component of many pesticide formulations. These results were consistent with a wide survey of vegetable soils in the North of Delta, which has discovered that chlorpyrifos buildups were distinguished at significant levels and frequencies [41]. In a similar line, the predominant chlorpyrifos was seen in vegetable soils in China [37] and in agricultural soils in Nepal [13], [42]. The value of SD was high with propamocarb (0.116) this may be due to its concentration having quite high heterogeneous distribution in the studied area.

The levels of pesticide residues varied greatly in soils across the Eastern Nile Delta with CV ranging from 11.8 to 141.4. The highest CV values (141.4) were recorded for benalaxy, malathion, mandipropamid, oxyfluorfen and pyraclostrobin. The high CV value confirms that these pesticides have a wide concentration range. In general, the variation of pesticide levels in soils may be returned to many factors that play a vital role in pesticide persistence and degradation such as pesticide type, soil properties, soil processes and pesticide levels in irrigation [8], [24], [43].

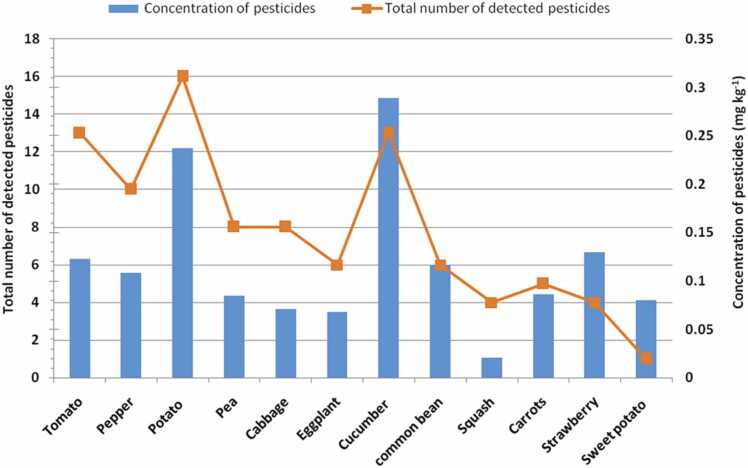

3.5. Pesticide residues by cultivated crops

The analysis of pesticide residues revealed the presence of many types of pesticides in soil samples with different levels according to the type of vegetable (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). The number of detected pesticides per crop ranged from 1 to 16. A high number of pesticide residues (16 pesticides) was detected in potato fields, followed by cucumber and tomato (13 pesticides), while one pesticide was detected in sweet potato fields. The residues of pesticide occurrence as a mixture of multiple compounds in the soil according to their application rates under different patterns of land use [8].

Fig. 4.

Total number of detected pesticides (line) and the average of pesticide residues (bars) in soils of vegetable crops.

Fig. 5.

Amount of detected pesticide residues in collected soil samples in the study area.

The mean concentration of total pesticides in the soil of vegetable crops decreases in the following order cucumber (0.289 mg kg–1) > potato (0.237 mg kg–1) > strawberry (0.130 mg kg–1) > tomato (0.123 mg kg–1)> common bean (0.117 mg kg–1) > pepper(0.108 mg kg–1) > carrot (0.086 mg kg–1) > pea (0.085 mg kg–1) > sweet potato (0.080 mg kg–1)> cabbage (0.071 mg kg–1) > eggplant (0.068 mg kg–1) > squash (0.021 mg kg−1). These data revealed that soil samples collected from greenhouses of cucumber had more pesticide residues in comparison with other open field crops. In this respect, Mokhtar et al. [43] reported that the closed environment of greenhouses encourages the growth and proliferation of pests and diseases that force farmers to spray plants with pesticides for short periods. In Egypt, most growers apply pesticides more than once per week in greenhouses producing vegetables [44]. On the other hand, the high concentration of pesticide residues in the tested soils from potatoes was noticed in line with the reported intensive pesticide use in root crops [12].

The most widely detected pesticide residues were chlorpyrifos and propamocarb. Chlorpyrifos, as an organophosphate insecticide, was detected in soils of seven vegetables (cabbage, common bean, eggplant, pepper, potato, sweet potato and tomato), and the highest level was recorded in potato (0.2 mg kg−1 soil). This might be because these vegetables are more susceptible to insects or due to easy degradation of chlorpyrifos that’s why these are applied frequently and there can be a possibility that insects have developed a low level of resistance towards this pesticide. These findings are similar to those found in a study conducted in vegetable fields where chlorpyrifos was found to be the most common pesticide residue in the vegetable soils [37], [41]. Propamocarb, as a systemic fungicide was detected in soils of four vegetables and the highest level, was recorded in pea (0.26 mg kg–1soil) followed by cucumber (0.23 mg kg–1soil).

3.6. Pesticide residues in relation to soil properties

Correlations have been examined between the total concentration of pesticides in soils and various soil parameters (Fig. 6). Soil organic matter (OM %) was observed to be positively connected with the total concentration of pesticides (r = 0.225), demonstrating that the adsorption of pesticides could be upgraded by soil organic matter. This correlation was also found in previous studies of agricultural soil [14], [37], [45], [46], [47]. Soil organic matter is a vital factor affecting pesticide behavior in soils [7]. Pesticides tend to bind with the organic matter of soil because of their hydrophobic nature [48]. Consequently, the bioavailability of pesticides will be reduced in ecological systems [49]. Farina et al. [50] reported that the organic matter of soil reduced the mobility of most pesticides in the soil of vegetables as it has an effect on the biodegradability, leachability, volatility, persistence and bioactivity of pesticides. On the other hand, the high organic matter content in the soil may provide more carbon to facilitate microbial degradation of pesticides [47], [51]. The poor correlation between soil organic matter and pesticides in vegetable farmland may be because fields of vegetables are subject to more frequent changes in cultivated crops, which results in different manure and pesticide usage [45], [52]. Moreover, vegetable soils in the study area have a very little amount of organic matter (average 1.21% and maximum 2.21%). Therefore, there is low retention of pesticides in these soils.

Fig. 6.

Linear regression analysis of pesticides and soil properties. * indicates significance at p < 0.05.

Soil properties influence the reactivity and mobility of pesticides in soil, e.g., pesticides tend to stay longer in agricultural soils with high organic matter and clay content [36], [53]. However, soil clay, pH and EC contents had no significant correlation with the total concentration of pesticides in this study. This may be clarified that the relatively narrow pH and EC ranges of studied soils, vegetable types, and physicochemical qualities of pesticides can make an inadequate gradient to show any significant relationship. Some studies have reported that the residual pesticides in soils had no significant correlation with the percentage of clay or soil pH [10], [37]. In fact, Positive correlations between the concentration of total pesticides and clay or silt content have been observed in some studies [11], [14]. The clay's role as sorbents of pesticides is of minor importance where the contents of soil organic matter are relatively high [54]. In this regard, when the content of organic matter was < 2% in 70% of the soil samples, it was very low for facilitating adsorption, and when the content of clay/silt was > 45% in 50% of soil samples, it was insufficient to facilitate the adsorption of pesticides [55].

3.7. Human health risk assessment

The health risk of contaminants in agricultural soils could be estimated in dietary and non-dietary exposure pathways [56]. Referred to the doses of pesticides as recommended by the U.S. EPA, the non-cancer risks were calculated through ingestion (ing), dermal (derm) and inhalation (inh) routes. According to Table 2, the HQ values of studied pesticides through three pathways decreased in the order of ingestion > dermal > inhalation. This result implies that the ingestion exposure had the highest risk for both adults and children. Previous studies have reported similar results [57], [58]. The HI values of all pesticides fell in the range of 10−7 to 10−3, but did not exceed the target risk level of1.0 for both children and adults, demonstrating that the non-cancer risks in study soils were negligible. These findings are partially in line with the outcomes of previous studies carried out on vegetable soils [13], [46], [59]. The non-cancer risks for children were much higher than those for adults. The possible reason for higher risks for children might be due to their higher exposure to given doses of pesticides. These risks are due to the ingestion route. Children are more vulnerable to ingestion route due to the sucking of a hand or finger inadvertently during their playing with contaminated soil [46], [59]. Among the individual pesticides, the highest non-cancer risk was observed for methamidophos in both studied age groups (HI = 4.10E-03for children and 4.40E-04for adults) followed by chlorpyrifos (HI = 1.67E-03 for children and 1.79E-04for adults). For the health risks of the most detected pesticides in the studied soils, chlorpyrifos is an organophosphate pesticide that has a wide range of applications, it has been identified to inhibit an enzyme that causes neurotoxicity and has been linked to potential neurological consequences in children. Propamocarb was classified as slightly dangerous for oral, dermal, and eye irritation, and basically non-toxic for acute inhalation and skin irritation [33].

Table 2.

Health risks of pesticides in vegetable soils from the Eastern Nile Delta.

| Pesticide |

HQ ing |

HQ derm |

HQ inh |

HI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Children | Adults | Children | Adults | Children | Adults | Children | |

| Atrazine | 6.11E-07 | 5.7E-06 | 2.58E-09 | 1.35E-08 | 6.5E-11 | 1.57E-10 | 6.13E-07 | 5.71E-06 |

| Carbofuran (RD) | 6.03E-06 | 5.63E-05 | 2.55E-08 | 1.33E-07 | 6.4E-10 | 1.55E-09 | 6.05E-06 | 5.64E-05 |

| Chlorpyrifos | 0.178 | 0.1 666 | 7.54E-07 | 3.95E-06 | 1.9E-08 | 4.59E-08 | 1.79E-04 | 1.67E-03 |

| Chlorpyrifos methyl | 2.05E-06 | 1.92E-05 | 8.68E-09 | 4.55E-08 | 2.19E-10 | 5.29E-10 | 2.06E-06 | 1.92E-05 |

| Cypermethrin | 6.28E-07 | 5.86E-06 | 2.65E-09 | 1.39E-08 | 6.69E-11 | 1.62E-10 | 6.31E-07 | 5.87E-06 |

| Dimethoate | 1.18E-05 | 0.11 | 5E-08 | 2.62E-07 | 1.26E-09 | 3.04E-09 | 1.19E-05 | 1.11E-04 |

| Linuron | 4.74E-06 | 4.43E-05 | 2E-08 | 1.05E-07 | 5.06E-10 | 1.22E-09 | 4.76E-06 | 4.44E-05 |

| Malathion (RD) | 1.16E-06 | 1.09E-05 | 4.92E-09 | 2.58E-08 | 1.24E-10 | 3E-10 | 1.17E-06 | 1.09E-05 |

| Metalaxyl | 6.89E-07 | 6.43E-06 | 2.91E-09 | 1.53E-08 | 7.34E-11 | 1.77E-10 | 6.92E-07 | 6.44E-06 |

| Methamidophos | 0.438 | 0.4 091 | 1.85E-06 | 9.71E-06 | 4.67E-08 | 1.13E-07 | 4.40E-04 | 4.10E-03 |

| Methomyl (RD) | 4.01E-06 | 3.74E-05 | 1.69E-08 | 8.87E-08 | 4.27E-10 | 1.03E-09 | 4.02E-06 | 3.75E-05 |

| Oxyfluorfen | 2.19E-06 | 2.05E-05 | 9.25E-09 | 4.85E-08 | 2.34E-10 | 5.64E-10 | 2.20E-06 | 2.05E-05 |

| Pendimethalin | 3.34E-07 | 3.12E-06 | 1.41E-09 | 7.41E-09 | 3.57E-11 | 8.61E-11 | 3.36E-07 | 3.13E-06 |

| Thiobencarb | 3.48E-06 | 3.25E-05 | 1.47E-08 | 7.71E-08 | 3.71E-10 | 8.96E-10 | 3.50E-06 | 3.26E-05 |

4. Conclusions

This study was directed to investigate the status and human health risks of pesticide residues in vegetable soils in the Eastern Nile Delta area as a representative of Egypt. The findings as the first systematic data can be valuable to support the practices of soil pollution management and to prevent further deterioration of the soils of the vegetable fields by pesticides. Most soil samples have two (36.7%) and three (30%) pesticide residues. The most detected pesticide was chlorpyrifos with detection rates of 28.33%. The highest concentrations of pesticide residues were determined for propamocarb (0.152 mg kg−1) and chlorpyrifos (0.122 mg kg−1). The hazard of the noticed pesticides in vegetable soils was within the acceptable limit for human health, where the hazard index was < 1 for non-carcinogenic risk. Although the current risks are acceptable, efforts should be made to provide awareness among local farmers to control the load of pesticides. Moreover, more attention should be paid in the future to pesticide load reduction and pesticide residue monitoring on vegetable field soils. Future studies should investigate the toxicity of pesticide residue mixtures in vegetable field soil, specifically the possibility of combined effects of different pesticide residues on different taxa.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ehab A. Ibrahim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing − original draft preparation, Visualization, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing − review & editing. Shehata E.M. Shalaby: Methodology, Data curation, Writing − original draft preparation, Visualization, Validation, Writing − review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was fully supported by the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF), Ministry of Scientific Research, Egypt, through project ID 41 539, therefore we thank the STDF for the financial support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2022.06.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Sh E.M., Shalaby G.Y., Abdou I.M., El-Metwally G.M. Abou-ellela, Health risk assessment of pesticide residues in vegetables collected from Dakahlia, Egypt. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2021;61:254–264. [Google Scholar]

- 2.APC, Agricultural Pesticides Committee, Egypt, 2019. 〈http://www.apc.gov.eg/AR/〉.

- 3.Mansour S.A. Environmental impact of pesticides in Egypt. Rev. Environ. Contam. 2008;196:1–51. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78444-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FAO ITPS, Global Assessment of the Impact of Plant Protection Products on Soil Functions and Soil Ecosystems, FAO, Rome, 2017: pp: 40.

- 5.Jiao C., Chen L., Sun C., Jiang Y., Zhai L., Liu H., Shen Z. Evaluating national ecological risk of agricultural pesticides from 2004 to 2017 in China. Environ. Pollut. 2020;259:11378. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lechenet M., Dessaint F., Py G., Makowski D., Munier-Jolain N. Reducing pesticide use while preserving crop productivity and profitability on arable farms. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:1–6. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Delgado C., Marin-Benito J.M., Sanchez-Martin M.J., Rodriguez-Cruz M.S. Organic carbon nature determines the capacity of organic amendments to adsorb pesticides in soil. J. Hazard Mater. 2020;390 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar B., Mukhopadhyay R., Mandal A., Mandal S., Vithanage M., Biswas J.K. In: Agrochemicals Detection, Treatment and Remediation. Prasad M.N.V., editor. Butterworth-Heinemann; 2020. Sorption and desorption of agro-pesticides in soils; pp. 189–205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damalas C.A., Eleftherohorinos I.G. Pesticide exposure, safety issues, and risk assessment indicators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2011;8:1402–1419. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8051402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hvězdová M., Kosubová P., Košíková M., Scherr K.E., Šimek Z., Brodský L., Šudoma M., Škulcová L., Sáňka M., Svobodová M., Krkošková L., Vašíčková J., Neuwirthová N., Bielská L., Hofman J. Currently and recently used pesticides in Central European arable soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;613–614:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pose-Juan E., Sanchez-Martin M.J., Soledad Andrades M., Sonia Rodriguez-Cruz M., Herrero-Hernandez E. Pesticide residues in vineyard soils from Spain: spatial and temporal distributions. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;514:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva V., Mol H.G.J., Zomer P., Tienstra M., Ritsema C.J., Geissen V. Pesticide residues in European agricultural soils – A hidden reality unfolded. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;653:1532–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhandari G., Atreya K., Scheepers P.T., Geissen V., V Concentration and distribution of pesticide residues in soil: Non-dietary human health risk assessment. Chemosphere. 2020;253 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manjarres-López D.P., Andrades M.S., Sánchez-González S., Rodríguez-Cruz M.S., Sánchez-Martín M.J., Herrero-Hernández E. Assessment of pesticide residues in waters and soils of a vineyard region and its temporal evolution. Environ. Pollut. 2021;284 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sultana J., Syed J.H., Mahmood A., Ali U., Rehman M.Y.A., Malik R.N., Li J., Zhang G. Investigation of organochlorine pesticides from the Indus Basin, Pakistan: sources, air–soil exchange fluxes and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;497:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pena A., Delgado-Moreno L., Rodriguez-Liebana J.A. A review of the impact of wastewater on the fate of pesticides in soils: effect of some soil and solution properties. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;718 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joko T., Anggoro S., Sunoko H.R., Rachmawati S. Pesticides usage in the soil quality degradation potential in Wanasari Subdistrict, Brebes, Indonesia. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2017;2017 7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafique N., Tariq S.R., Ahmed D. Monitoring and distribution patterns of pesticide residues in soil from cotton/wheat fields of Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016;188:695. doi: 10.1007/s10661-016-5668-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Close M.E., Humphries B., Northcott G. Outcomes of the first combined national survey of pesticides and emerging organic contaminants (EOCs) in groundwater in New Zealand 2018. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.FAO. Agricultural pollution: pesticides. Retrieved on: 12 January, 2020, pp. 6. 〈http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/689281521218090562/pdf/124345-BRI-p153343-PUBLIC-march-22–9-pm-WB-Knowledge-Pesticides.pdf〉.

- 21.Ukalska-Jaruga A., Smreczak B., Siebielec G. Assessment of pesticide residue content in polish agricultural soils. Molecules. 2020;25:587. doi: 10.3390/molecules25030587.(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z., Jennings A. Worldwide regulations of standard values of pesticides for human health risk control: a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14:826. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kailani M.H., Al-Antary T.M., Alawi M.A. Monitoring of pesticides residues in soil samples from the southern districts of Jordan in 2016/2017. Toxin. Rev.. 2019:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Nasir F., Al-Nasir Farh M., Jiries A.G., Al-Rabadi G.J., Alu’datt M.H., Tranchant C.C., Al-Dalain S.A., Alrabadi N., Madanat O.Y., Al-Dmour R.S. Determination of pesticide residues in selected citrus fruits and vegetables cultivated in the Jordan Valley. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2020;123 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.109005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salem S., Abd-El Fatah S., Abdel-Rahman G., Fouzy A., Marrez D. Screening for pesticide residues in soil and crop samples in Egypt. Egypt J. Chem. 2021;64:2525–2532. doi: 10.21608/ejchem.2021.64117.3374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnous M.O., El-Rayes A.E., Green D.R. Hydrosalinity and environmental land degradation assessment of the East Nile Delta region, Egypt. J. Coast Conserv. 2015;19:491–513. doi: 10.1007/s11852-015-0402-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allam A., Tawfik A., Yoshimura C., Fleifle A. Simulation-based optimization framework for reuse of agricultural drainage water in irrigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2016;172:82e96. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.EMARS. Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture Reclamation of Soils. Agricultural Statistics Second Part. Economic Affairs Sector, Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation, Giza, ARE, 2017.

- 29.Jackson M.L. Soil Chemical Analysis. 1s tedn., Prentice Hall of India Pvt. Ltd.,; New Delhi, India: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 30.I.I. Bashour, A.H. Sayegh, Methods of Analysis for Soils of Arid and Semi-Arid Region (American University of Beirut, Lebanon FAO, Rome, 2007).

- 31.ILNAS-EN 15662. Foods and plant origin – Multimethod for the determination of pesticide residues using GC- and LC-based analysis following acetonitrile extraction/partitioning and clean-up by dispersive SPE – Modular QuEChERS method. European Committee for Standardization, Brussels, 2018.

- 32.Soliman M., Khorshid M.A., El-Marsafy A.M., Abo-Aly M.M., Khedr T. Determination of 10 pesticides, newly registered in Egypt, using modified QuEChERS method in combination with gas and liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometric detection. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019;99:224–242. doi: 10.1080/03067319.2019.1588263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.USEPA. United State Environmental Protection Agency. Risk-Based Screening Table, 2015. Retrieved on: 〈http://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-table〉.

- 34.Hathout A.S., Amer M.M., Mossa A.H., Hussain O.A., Yassen A.A., Elgohary M.R., Fouzy A.S.M. Estimation of the most widespread pesticides in agricultural soils collected from some Egyptian Governorates. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022;65:35–44. doi: 10.21608/ejchem.2021.72087.3591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO, The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guideline to Classification 2019 (2020) 6.

- 36.Chiaia-Hernandez A.C., Keller A., Wächter D., Steinlin C., Camenzuli L., Hollender J., Krauss M. Long-term persistence of pesticides and TPs in archived agricultural soil samples and comparison with pesticide application. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2017;51:10642–10651. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b02529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan H., Li Q., Zhang H., Wu C., Zhao S., Deng X., Li Y. Pesticide residues in agricultural topsoil from the Hainan tropical riverside basin: Determination, distribution, and relationships with planting patterns and surface water. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;722 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malhat F., Nasr I. Monitoring of organophosphorous pesticides residues in water from the Nile River Tributaries, Egypt. Am. J. Water Resour. 2013;1:1–4. doi: 10.12691/ajwr-1-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anonymous . The Pesticide Manual. 16th ed.., BCPC Publications, British Crop Protection Council,; Alton, Hampshire: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cink J.H. Iowa State University,; Ames, Iowa, USA: 1995. Degradation of Chlorpyrifos in Soil: Effect of Concentration, Soil Moisture, and Temperature. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbassy M.M.S. Farmer’s knowledge, attitudes and practices, and their exposure to pesticide residues after application on the vegetable and fruit crops. case study: North of Delta, Egypt. J. Environ. Anal. Toxicol. 2017;7:510. doi: 10.4172/2161-0525.100051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhandari G., Atreya K., Vašíčková J., Yang X., Geissen V. Ecological risk assessment of pesticide residues in soils from vegetable production areas: A case study in S-Nepal. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;788 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mokhtar S., El Agroudy N., Shafiq F.A., Abdel Fatah H.Y. The effects of the environmental pollution in Egypt. Int. J. Environ. 2015;4:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parker B.L., Abd-Rabou S., Skinner M. Pest management practices in greenhouses producing vegetables in Egypt. Egypt J. Plant Prot. Res. Inst. 2021;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qu C., Qi S., Yang D., Huang H., Zhang J., Chen W., Yohannes H.K., Sandy E.H., Yang J., Xing X. Risk assessment and influence factors of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in agricultural soils of the hill region: a case study from Ningde, southeast China. J. Geochem. Explor. 2015;149:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gexplo.2014.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niu L., Xu C., Zhu S., Liu W. Residue patterns of currently, historically and never-used organochlorine pesticides in agricultural soils across China and associated health risks. Environ. Pollut. 2016;219:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yadav I.C., Devi N.L., Li J., Zhang G., Shakya P.R. Occurrence, profile and spatial distribution of organochlorines pesticides in soil of Nepal: implication for source apportionment and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;573:1598–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Devi N.L., Yadav I.C., Raha P., Shihua Q., Dan Y. Spatial distribution, source apportionment and ecological risk assessment of residual organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in the Himalayas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015;22:20154–20166. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zehra A., Eqani S.A.M.A.S., Katsoyiannis A., Schuster J.K., Moeckel C., Jones K.C., Malik R.N. Environmental monitoring of organo-halogenated contaminants (OHCs) in surface soils from Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;506–507:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farina Y., Abdullah Md.P., Bibi N., Afiq W.M., Khalik W.M. Pesticides residues in agricultural soils and its health assessment for humans in Cameron Highlands, Malaysia. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2016;20:1346–1358. doi: 10.17576/mjas-2016-2006-13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai D.W. Understand the role of chemical pesticides and prevent misuse of pesticides. Bull. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2008;1:36e38. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koli P., Bhardwaj N.R., Mahawer S.K. In: Climate Change and Agricultural Ecosystems. Choudhary K.K., Kuar A., Singh K.A., editors. Woodhead Publishing; Sawton, Cambridge: 2019. Agrochemicals: harmful and beneficial effects of climate changing scenarios; pp. 65–94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma A., Kumar V., Shahzad B., Tanveer M., Sidhu G.P.S., Handa N., Kohli S.K., Yadav P., Bali A.S., Parihar R.D., Dar O.I., Singh K., Jasrotia S., Bakshi P., Ramakrishnan M., Kumar S., Bhardwaj R., Thukral A.K. Worldwide pesticide usage and its impacts on ecosystem. SN Appl. Sci. 2019;1:1446. doi: 10.1007/s42452-019-1485-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baskaran S., Bolan N.S., Rahman A., Tillman R.W. Pesticide sorption by allophonic and non-allophanic soils of New Zealand. NZ J. Agric. Res. 1996;39:297–310. doi: 10.1080/00288233.1996.9513189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andrades M.S., Sánchez-Martín M.J., Sánchez-Camazano M. Significance of soil properties in the adsorption and mobility of the fungicide metalaxyl in vineyard soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:2363–2369. doi: 10.1021/jf001233c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niu L., Xu C., Yao Y., Liu K., Yang F., Tang M., Liu W. Status, influences and risk assessment of hexachlorocyclohexanes in agricultural soils across China. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2013;47:12140–12147. doi: 10.1021/es401630w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ma J., Pan L., Yang X., Liu X., Tao S., Zhao L., Qin X., Sun Z., Hou H., Zhou Y. DDT, DDD, and DDE in soil of Xiangfen County, China: residues, sources, spatial distribution, and health risks. Chemosphere. 2016;163:578e583. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kafaei R., Arfaeinia H., Savari A., Mahmoodi M., Rezaei M., Rayani M., Sorial G.A., Fattahi N., Ramavandi B. Organochlorine pesticides contamination in agricultural soils of southern Iran. Chemosphere. 2020;240 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Z., Sun J., Zhu L. Organophosphorus pesticides in greenhouse and open-field soils acrossChina: Distribution characteristic, polluted pathway and health risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;765 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material