Abstract

We evaluated the effect of multiple exposures to electronic cigarettes on human oral mucosa structure and proinflammatory cytokine secretion. A 3D air-liquid interface human gingival mucosa was produced and exposed 10 min twice a day for 2 and 4 days for a total of 4 or 8 exposure times to e-cigarette aerosol. The vaped e-liquid contained 18 mg/ml of nicotine. Results show that 4 and 8 exposures to the e-cigarettes with and without nicotine-induced structural tissue damage, decreased Laminin and type IV collagen production but increased the secretions of several metalloproteinases (MMPs), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The e-cigarette reduced the number of proliferative epithelial cells, as ascertained by the low number of Ki-67+ cells. Exposure to e-cigarette aerosol increased proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, MCI-1, and TNFα. However, the e-cigarette aerosol effects were lower than combustible cigarette smoke (CS). Although e-cigarette aerosols produced less tissue damage than CS, they still induce critical damage to the engineered human gingival mucosa. E-cigarette users and oral health professionals should be aware of the potential adverse effects of e-cigarettes.

Keywords: E-cigarettes, Oral mucosa, Cigarette smoke, Tissue structure, MMPs, Cytokines

1. Introduction

It is well known that smoking causes significant health problems for smokers and results in millions of deaths worldwide yearly [37]. It is estimated that by 2050, close to 400 million adults will suffer smoke-related illnesses causing their death [12]. Different initiatives have been introduced to encourage smokers to reduce cigarette consumption and even quit smoking altogether to prevent and mitigate the adverse effects of tobacco smoke. Among the proposed methods to limit the damaging impact of cigarette smoke is electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes). These devices are heat non-burned nicotine delivery systems [9]. The e-cigarette contains a cartridge to hold the e-liquid for vaping. Vaping is generated by a heating element known as an atomizer, with the generated vapor consisting of an aerosol. The produced aerosol reaches the upper and lower airways through a mouthpiece tubing; the generated aerosol thus enters the body through the mouth. The e-cigarette contains a battery that can be recharged to heat the e-liquid generating the aerosol [9].

Upon entering the mouth, the aerosol reaches all tissues and liquids in the oral cavity, including the teeth and the gingival mucosa. Due to its structure, this mucosa serves as a mechanical and immunological barrier [24]. Indeed, gingival mucosa consists of an epithelium tightly linked to a connective tissue known as the lamina propria.

The gingival epithelium is a multilayered structure consisting of basal, spinous, granular, and stratum corneum layers [21]. The basal and spinous layers are formed mostly of proliferative cells that express the Ki67 marker. This marker is highly expressed in cycling cells but is strongly downregulated in resting G0-cells [7].

Basal epithelial cells interact with gingival fibroblasts in the lamina propria to secrete and deposit laminin and type IV collagen to form a cell-adherent extracellular matrix known as the basement membrane (BM). This BM is essential for epithelial cell-fibroblast communication and tissue integrity [25]. With its multilayered structure, the epithelium’s mechanical barrier protects from the invasion of oral microorganisms into the body. The epithelial structure also has an immune role by secreting different pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines to prevent oral infections.

Unfortunately, the gingival epithelium is exposed to various damaging agents, including tobacco smoke. In cigarette smokers, the gingival mucosa structure is deregulated [18]. These structural, soft-tissue changes include basement membrane protein and connective tissue deregulations. This has been shown with nasal tissues [36]. This epithelium damage could be due to a direct effect of cigarette smoke on epithelial cell behaviors. Its ability to produce multiple mediators also plays a role in local innate immunity [30]. Connective tissue degradation involved multiple proteolytic enzymes named metalloproteinases (MMPs). These are specialized, zinc-dependent proteases playing essential functions in physiological processes, such as growth, development, and tissue remodeling and maintenance, but also in pathological conditions [33], [35]. Previous studies demonstrated increased levels of MMP following exposure to cigarette smoke which could explain pulmonary hypertension [38], periodontal health ([14].), etc.

Because e-cigarettes generate different harmful chemicals, such as those found in regular cigarette smoke [17], [6], e-cigarette vapor could thus adversely affect gingival mucosa tissue structure and cytokine secretion. Indeed, recent studies using monolayer cultures have shown e-cigarettes to decrease epithelial cell growth and increase cell apoptosis [19], [28]. We, therefore, sought to evaluate the effect of nicotine-free and nicotine-rich e-cigarette aerosol on gingival mucosa tissue structure, the secretions of LDH and MMPs, the expression of cell proliferation marker (Ki-67), and the secretion of various cytokines. To reach this goal, we used an engineered human gingival mucosa to mimic probable occurrences in the gingival mucosa of e-cigarette users.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Engineered human oral mucosa (EHOM)

Oral mucosa tissues were generated using primary human gingival epithelial cells and fibroblasts extracted from gingival tissue. The tissues were collected from systemically and periodontally healthy non‐smoking donors (18–25 years of age) after obtaining their informed consent and the approval of the University Laval ethics committee (No. 2012–062). The donors were not users of other tobacco forms (chewable, snuff, etc.). Gingival fibroblasts and epithelial cells were extracted and cultured as previously described [26]. To engineer the oral mucosa tissues, gingival fibroblasts were mixed with bovine skin collagen (Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd., Oakville, ON, Canada) to produce the connective tissues. These were grown for 4 days in Dulbecco-Vogt modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum. At the end of this culture period, gingival epithelial cells were seeded onto the connective tissues and were grown in a 3:1 mixture of the Dulbecco-Vogt modification of Eagle’s medium and Ham’s F12 medium (DMEH; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Burlington, ON, Canada) supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum, 24.3 μg/ml of adenine, 10 μg/ml of human epidermal growth factor, 0.4 μg/ml of hydrocortisone, 5 μg/ml of bovine insulin, 5 μg/ml of human transferrin, and 2 × 10−9 M of 3,3′,5′-triiodo-L-thyronine. Once the epithelial cells reached confluence, the engineered human oral mucosa (EHOM) was raised to an air-liquid interface for 6 days to allow for the epithelium to stratify [26]. The EHOMs were then ready to be exposed or not to e-cigarette aerosol.

2.2. Electronic cigarettes

Electronic cigarette devices were obtained from local retailers (eGo ONE CT, Québec City, QC, Canada). The e-cigarette devices were used in the CW mode, referring to 25 W/15 W/7.5 W, with an 1100 mAh battery. We used Smooth Canadian tobacco-flavored e-liquid that contained 50 % PG/50 % VG with and without nicotine at 18 mg/ml. The selected e-cigarette devices and e-liquids were chosen because of their availability to users. 3R4F cigarettes purchased from the Kentucky Tobacco Research & Development Center (Orlando, FL, USA) served as the combustible cigarette models.

2.3. Exposure of EHOM to e-cigarette aerosol

Engineered tissues were exposed or not to nicotine-rich (NR) or nicotine-free (NF) e-cigarette aerosol in specific chambers, as previously described [27]. To prevent cross-contamination between the nicotine and the chemicals, different e-cigarette devices and different exposure chambers were used. The exposure regime to the e-cigarettes was reached by drawing the aerosol into the exposure chamber (2 puffs every 60 s; a 5–s puff followed by a 25–s pause), as described previously [13], [27], with some modifications. The exposure time consisted of 10 min twice a day for 2 and 4 days. After each exposure time, the EHOMs were placed on the air-liquid interface culture plate, fed fresh medium, and placed in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere at 37ºC. Different analyses were performed after each exposure period (2 and 4 days). The control EHOMs were exposed or not to CS for 10 min twice a day, as with the e-cigarette exposures. The 2-day (4 exposures) and 4-day (8 exposures) exposures to e-cigarette aerosol were selected to mimic low and mid-e-cigarette users.

2.4. Tissue structure after exposure to e-cigarette aerosol

Following exposure for 2 days (4 exposures) and 4 days (8 exposures), biopsies were collected randomly from each EHOM for structural analysis. The biopsy specimens were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde solution for 24 h, then embedded in paraffin. Five-μm sections were deparaffinized, stained with Masson’s trichrome, mounted with 50 % glycerol mounting medium, observed under an optical microscope, and photographed. The experiment was repeated four independent times, in duplicate, for each condition (non-exposed, NF-, NR-, and CS-exposed EHOM).

2.5. LDH levels

Engineered gingival mucosa tissues were exposed 2 times a day for 24 and 48 h, as described above. Following each culture period (24 and 48 h), tissue injury was assessed by measuring the LDH levels in the culture medium. Briefly, aliquots of the culture supernatant were collected and subjected to an LDH cytotoxicity assay (Promega, Madison, WI). The supernatant (50 μl) of each condition was transferred to a 96-well flat-bottom plate. Each well was supplemented with 50 μl reconstituted substrate mix, and the plate was incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. To stop the reaction, 50 μl of an acid solution was added to each well. After mixing, a volume of 120 μl was transferred from each well to another 96-well flat-bottom plate. The absorbance was read at 490 nm with an X-Mark microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Positive and negative controls were included in each experiment. This positive control (PC) refers to cells being cultured in the presence of 1 % of Triton X-100 to have total cell lysis. The negative control refers to the cell being cultured without exposure to cigarette smoke.

The percentages of toxicity were calculated as follows:

The LDH measurement was done 4 different times in triplicate. The results were reported as means ± SD.

2.6. Production and deposition of basement membrane proteins (laminin-5 and Type IV collagen)

Tissue samples were taken from each EHOM exposed or not to e-cigarette aerosol/cigarette smoke and paraffin-embedded, with thin (5 µm) sections prepared from each biopsy. The tissue sections were then overlaid with either mouse anti-laminin 5 (1:200) or rabbit anti-type IV collagen (1:1000) and incubated at 4 C overnight. The next day, the tissue sections were washed 3 × 5 min with PBS, then overlaid with either HRP anti‐mouse or anti‐rabbit (Cell Signaling, Whitby, ON, Canada) secondary antibodies for 45 min at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Cell Signaling) for 1–2 min, washed twice thereafter with PBS, and counterstained with hematoxylin (Dako, Burlington, ON, Canada) at room temperature. Lastly, the sections were mounted with mounting media (Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada), covered with a coverslip, and subjected to imaging analyses under a Leitz Aristoplan microscope (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany), and photographed.

2.7. Expression of Ki-67

Tissue sections were prepared from each EHOM, subjected to immunohistochemistry using purified rabbit polyclonal anti-Ki-67 antibody (Cat#AB9260; EMD Millipore, Montréal, QC, Canada) diluted to 1/100, and were then incubated overnight at 4 C. The next day; tissue sections were washed three times with PBS, and overlaid with HRP goat anti-rabbit polyclonal secondary antibody (BD Bioscience, Mississauga, ON, Canada), diluted to 1/200, for 60 min at room temperature. The sections were washed three times with PBS and overlaid with 30 μl of DAB for 2 min at room temperature. Following the PBS washes, the tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 6 min at room temperature, washed three times with PBS, dehydrated, mounted, observed under an optical microscope, and photographed. The stained cells were then counted under an optical microscope (at least 10-field for each slide, with three slides from each experiment). Results were presented as mean + SD (n = 4).

2.8. Cytokine array

The EHOM were generated and exposed to e-cigarette aerosol with and without nicotine for 10 min each, with a 6-h interval between the first and second exposure. Following the second exposure, they were cultured overnight at 37 ºC in a 5 % C02 incubator. The next day, the supernatants were collected and subjected to cytokine and MMP array assays. The supernatants' cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and MMPs were detected using a Milliplex Human Cytokine/Chemokine plex kit (Millipore, St. Charles, MO, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The multiplexing analysis was performed using the Luminex™ 100 system (Eve Technologies Corp., Calgary, AB, Canada). According to the manufacturer, assay sensitivities range from 0.1 to 9.5 pg/ml. Each experiment was repeated four times and the means ± SD were calculated and plotted.

2.9. Statistical analyses

Each experiment was performed at least four times, with experimental values expressed as means ± SD. The statistical significance of the differences between the control (non-exposed) and test (exposed to either e-cigarette aerosol or cigarette smoke) values were determined by means of a one-way ANOVA. Posteriori comparisons were made using Tukey’s method. Normality and variance assumptions were verified by means of the Shapiro-Wilk and the Brown and Forsythe tests. All of the assumptions were fulfilled. P values were declared significant at ≤ 0.05. The data were analyzed using the SAS version 8.2 statistical package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. The contract with e-cigarette aerosol deregulates the tissue structure

In normal gingival mucosa, the differentiation of epithelial cells involves several morphological and biochemical modifications that lead to the multilayer organization of the epithelium [10]. Our results demonstrate that the epithelial cells in the non-exposed EHOM were organized in a multilayered epithelial structure with a basal cell layer that consisted of interconnected epithelial cells (Fig. 1, a, and e). The epithelial structure also consisted of at least two subsequent layers, including a stratum corneum-like layer (Fig. 1a, and e). In the EHOM exposed to e-cigarette aerosol for 2 days, morphological changes were observed in the epithelial structure (Fig. 1b, and c). The tissues exposed to NR e-cigarette aerosol showed a rupture of the interconnection between basal cells. Also observed in the basal layer were large-sized cells and a thicker stratum corneum (Fig. 1c). The tissue changes were less evident in the NF aerosol exposure (Fig. 1b) than in the NR aerosol exposure. The tissues exposed to e-cigarette aerosol with or without nicotine nevertheless showed less structural damage than those exposed to CS (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Gingival tissue structure after e-cigarette aerosol and combustible cigarette smoke exposures. Engineered human gingival mucosa was produced using primary human fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Tissues were exposed 10 min twice a day for 2 and 4 days, then subjected to Masson’s trichome staining. Photos are representative of 4 separate experiments, with each condition performed in duplicate. (a, b, c, and d) refer to 4 exposures, (e, f, g, and h) refer to 8 exposures. (Crtl) = control (non-exposed tissues), (NF) = nicotine-free aerosol, (NR) = nicotine-rich aerosol, (CS) = combustible cigarette smoke.

Structural changes were more readily observed with higher exposure frequency (8 times) (Fig. 1e to h). The non-exposed control tissues showed more than 4 layers forming the epithelium. The basal layer contained small cuboidal epithelial cells, followed by the supra-basal layer, with small-sized cells. The basal and supra-basal layers were interconnected cells (Fig. 1e). In contrast, in the NF e-cigarette-exposed EHOM, the epithelium showed structural changes, as the basal layer contained bigger cells that were detached from each other. The supra-basal layer was not easily observed, and the stratum corneum was dominant. In the NR e-cigarette-exposed EHOM, an obvious disorganized basal layer containing large-sized cells overlaid with a thick stratum corneum (Fig. 1g). The EHOM exposed to CS displayed greater structural damage (Fig. 1d) than what was observed in the tissues exposed to e-cigarette aerosol. Indeed, the tissues exposed to CS showed a reduced epithelium thickness containing a disorganized basal cell layer consisting of detached cells. In light of these results, one may think that the NR cigarette-exposed tissue was healthier than the tissue exposed to CS. However, it should be noted that the epithelial cells in the basal layer of the NR e-cigarette-exposed tissue were disconnected, as evidenced by the space separating the neighbor cells (Fig. 1c, and g). The structural changes observed in the epithelium thus suggest a potentially harmful effect of e-cigarette aerosol on gingival tissue structure. The structure damage could be through increased levels of MMPs (Table 1). We demonstrated that the level of MMP-1 ranged from 23.2 ± 1 ng/ml with the control to 30.9 ± 0.7 ng/ml with NF to 33.9 ± 1.5 ng/ml with NR aerosols. There was also a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the levels of MMP-2, MM-3, and MMP-9 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Levels of MMPs secreted by engineered gingival mucosa being exposed or not to e-cigarette aerosols.

| Control (pg/ml) | Nicotine-free aerosol (pg/ml) | Nicotine-rich aerosol (pg/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP-1 | 23,248 ± 1051 | 30,935 ± 774 P < 0.01 |

33,924 ± 1599 P < 0.001 |

| MMP-2 | 35,892 ± 710 | 39,705 ± 756 P < 0.001 |

47,001 ± 1924 P < 0.001 |

| MMP-3 | 13,028 ± 350 | 34,955 ± 640 P < 0.001 |

40,794 ± 300 P < 0.001 |

| MMP-9 | 2,517 ± 150 | 2739 ± 240 P < 0.05 |

4552 ± 300 P < 0001 |

(P) refers to the significance when comparing aerosol exposed to non-exposed tissues.

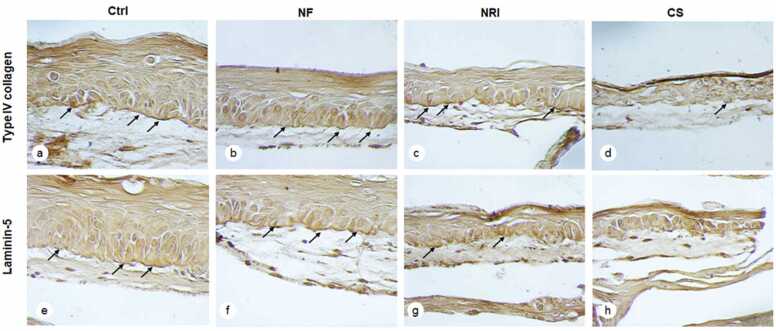

3.2. E-cigarette exposure decreased type IV collagen and laminin-5 presence in the basement membrane.

Because of the observed structural change in the epithelium following the exposure of EHOM to e-cigarette aerosol, we analyzed the presence /deposition of basement membrane proteins. As shown in Fig. 2, the EHOM exposed to e-cigarette aerosol for four days (8 exposures) showed definite changes in the deposition of type IV collagen in the basement membrane. In the non-exposed tissues, a dense and continuous protein line formed between the epithelial and connective tissue structures (Fig. 2a, arrow). However, a faint, discontinuous line of type IV collagen was evidenced in the tissues exposed to both NF (Fig. 2b) and NR (Fig. 2c) e-cigarette aerosol. This suggests that e-cigarette aerosol had a negative impact on type IV collagen presence, which can dysregulate the interaction of epithelial cells and fibroblasts through the basement membrane structure. In contrast, the effect of CS on type IV collagen presence was too harmful, resulting in almost no such protein presence (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

E-cigarette exposure reduced laminin-5 and type IV collagen production in the gingival mucosa tissues. Following 8 exposures to either e-cigarette aerosol or CS, the tissues were subjected to laminin-5 and type-IV collagen immunostaining, as described in the M&M. (a, b, c, and d) show collagen Type IV staining, and (e, f, g, and h) show laminin-5 staining. Arrows indicate the deposition of laminin-5 and Type IV collagen in the basement membrane. (Crtl) = control (non-exposed tissues), (NF) = nicotine-free aerosol, (NR) = nicotine-rich aerosol, (CS) = combustible cigarette smoke.

E-cigarette aerosol also negatively affected Laminin 5 presence. As shown in Fig. 2e, in the non-exposed control EHOM, continuous deposition of laminin-5 protein was observed. This deposition between the epithelium and the connective tissue was also noticeable in the EHOM exposed to either NF or NR e-cigarette aerosol (Fig. 2f and g), although this deposition was lower (as confirmed by the staining intensity and irregular/broken line) than that observed in the non-exposed controls (Fig. 2e to g, arrows). Exposure to CS led to a very low deposition of laminin-5 if any (Fig. 2h). Because the exposure to e-cigarette aerosol dysregulated the EHOM structure and the presence of BM proteins, the observed changes could lead to cell damage.

3.3. Exposure to e-cigarette aerosol increased the levels of LDH

To investigate the effect of e-cigarette aerosol on gingival tissue damage, the level of LDH in the culture medium was measured. As shown in Fig. 3, there was a significant (p < 0.01) increase in the levels of LDH following the tissue exposure to NF, NR aerosols, and CS compared to the control (non-exposed tissues). This increase was noticed after 2 and 4 exposures to e-cigarette aerosols. After 24 (2 exposures) h, the levels of LDH increased from 8 ± 1 % in control, 26 ± 2 % with NF, 34 ± 4 % with NR, to 76 ± 5 % with CS. The LDH increase was also noticed after 48 h (4 exposures) to the e-cigarette aerosols. This increase was 7 ± 1 % with the control, 30 ± 1.5 % with NF, 50 ± 2 % with NR, to 80 ± 8 % with CS. It is interesting to note that the levels of LDH at 48 h were higher than those at 24 h, suggesting increased tissue damage with the exposure time to e-cigarette aerosols. These LDH results confirm that e-cigarette aerosols led to gingival tissue damage. Because exposure to e-cigarette aerosols increased the secretion of LDH, this could decrease the number of proliferative cells in the gingival epithelium.

Fig. 3.

e-cigarette aerosol-exposed gingival mucosa displayed high lactate dehydrogenase levels (LDH). Tissues were exposed or not for 10 min twice daily to NF, NR, or CS for 24 h or 48 h. The culture supernatants were collected and used to measure LDH release as described in the Materials and Methods section. Results are the means ± SD of 4 separate experiments. Statistical significance was obtained by comparing the exposed and non-exposed (control) cells. *** P < 0.001.

3.4. Exposure to e-cigarette aerosol decreased the number of Ki67-positive cells

As shown in Fig. 4, the control tissues exhibited a high density of Ki67-positive cells at the basal and supra-basal levels (Fig. 4a, arrows). The repeated exposures of the EHOM tissues to either e-cigarette aerosol or CS for 2 days (data not shown) or 4 days (Fig. 4) showed fewer Ki67-positive cells. The microscopic observations revealed that the decrease in Ki67-positive cell density was more obvious with CS (Fig. 4d), followed by NR (Fig. 4c) and NF e-cigarette aerosol (Fig. 4b), respectively. These observations were confirmed by cell counting. After 4 exposures to CS, a significant (p < 0.01) reduction in the number of Ki67-positive cells was observed, ranging from 115 ± 20 in control to 61 ± 14 with CS. The decrease of Ki67 was also noticed with 4 exposures to NF and NR e-cigarette aerosol, ranging from 115 ± 20 in control to 99 ± 22 with the NF and 87 ± 13 with the NR e-cigarettes. The exposure 8 times led to a decrease in the number of proliferative cells. As shown in Fig. 4B, the number of Ki67-positive cells decreased from 149 ± 20 in control to 65 ± 16 with the NF and 43 ± 28 with the NR e-cigarettes, and 13 ± 5 with the CS. Overall results demonstrate that both e-cigarette aerosol and CS significantly reduced the number of Ki-67 + cells. This reduction was more evident after 8 exposures than after 4 exposures to e-cigarette aerosol.

Fig. 4.

Multiple exposures to e-cigarette aerosol decreased the number of Ki67+ cells in the gingival epithelium. After exposure to either e-cigarette aerosol or CS, the tissues were stained with anti-Ki67 antibody. Stained cells were counted and plotted. Panel A: distribution of Ki67+ cells in the different tissues. Panel B: quantitative measurement of Ki67 cells in each condition. The experiment was repeated 4 separate times. (a) = Ctrl, (b) = NF aerosol, (c) = NR aerosol, (d) = CS. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, * ** P < 0.001. Free asterisks refer to the statistical difference when comparing the exposed and non-exposed (Ctrl) tissues. Bars with asterisks indicate a comparison of the different conditions.

3.5. Exposure to e-cigarette aerosol increased proinflammatory cytokine secretion by gingival tissues

Engineered oral mucosa tissues were exposed or not to either e-cigarette aerosol or CS and subjected thereafter to cytokine analyses, which revealed a significant increase in the levels of different mediators (Fig. 5). The non-exposed controls showed a low basal level of secreted IL-6. After 2 exposures to NR e-cigarette aerosol, the levels of IL-6 increased significantly (P < 0.05), ranging from 1.7 ± 0.3 ng/ml in the control to 2.9 ± 0.8 ng/ml with the NR e-cigarettes. Increased secretion of IL-8 was also evidenced following exposure to e-cigarette aerosol, increasing from 8.1 ± 0.3 ng/ml in the control to 8.7 ± 0.4 ng/ml with the NF and 11.5 ± 3.6 ng/ml with the NR e-cigarettes. E-cigarette aerosol exposure also led to a significant (P < 0.01) increase in the levels of TNFα and MCP-1. Indeed, TNFα increased from 55 ± 14 pg/ml in the control to 98 ± 11 pg/ml with the NF and 130 ± 0.4 pg/ml with the NR e-cigarettes. As for MCP-1, the increase ranged from 1.7 ± 0.09 ng/ml in the control to 2.1 ± 0.08 ng/ml with the NF and 2.7 ± 0.3 ng/ml with the NR e-cigarettes. Finally, GM-CSF slightly yet significantly (P < 0.01) increased after exposure to NR e-cigarette aerosol. As expected, exposure to CS led to increased secretion of all measured proinflammatory cytokines. Other cytokines, including IL-1β, and IFNγ were measured, but their levels were too low, with no differences with the controls (data not shown). Overall results indicate that the nicotine-rich and nicotine-free e-cigarette aerosols promoted proinflammatory secretion by the gingival tissues at certain levels.

Fig. 5.

E-cigarette aerosol increased proinflammatory cytokine secretion by the gingival mucosa cells. Engineered gingival mucosa was exposed for 10 min, twice a day for one day; then culture medium was collected and subjected to a cytokine array, as described in the M&M section. The experiment was repeated three separate times. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Free asterisks refer to the statistical difference when comparing the exposed and non-exposed (Ctrl) tissues. Bars with asterisks indicate a comparison of the different conditions.

4. Discussion

Because of the heat and chemicals involved, e-cigarettes could damage oral cavity tissues, including the gingival mucosa. As an initial coverage and protection shield, the oral mucosa is the primary tissue to meet e-cigarette aerosols. To investigate the effect of these aerosols on human gingival mucosa tissue, we engineered a human gingival mucosa model that included fibroblast-populated collagen connective tissue. This connective tissue was seeded with normal human gingival epithelial cells to generate a stratified multilayered epithelium, following culture on an air-liquid interface system. This engineered oral mucosa model mimics native human gingival mucosa because it contains cell-populated connective tissue that interacts with multilayered and stratified gingival epithelium (Rouabhia et al. [26]).

Using these tissues, we demonstrated that e-cigarette aerosols could deregulate the epithelium's structure. These results support other findings with monolayer cell cultures [11], [27] and those generated with engineered tissue models using either cell lines or stratified epithelium without cell-populated connective tissue [23], [3].

The presence of a cell-populated connective tissue and its interaction with stratified epithelium are important stimulators of fibroblast/epithelial cell interactions in native human tissue. By demonstrating certain adverse effects of e-cigarettes on this engineered human oral mucosa, we showed that e-cigarette aerosols could negatively impact the oral epithelium of e-cigarette users. Indeed, the different epithelial layers in engineered human oral mucosa showed structural damage as the basal layer was disorganized with bigger cells. Compared to the control, these observations were noticed with the nicotine-rich and nicotine-free e-cigarettes. The effects of e-cigarette aerosol demonstrated in this study support those described previously, showing that chronic e-cigarette vapor aberrantly alters the physiology of lung epithelial cells and resident immune cells and promotes poor response to infectious challenges [15]. Furthermore, nasal mucosa tissue exposed to e-cigarette aerosol displayed structural deregulation, with more large-sized cells [28]. With such structure tissue damage following exposure to e-cigarette aerosol, e-cigarette use should thus be cautioned to minimize its adverse effects on the oral cavity, not to mention other tissues and organs in the body.

As demonstrated in this study, the non-structured tissue observed after e-cigarette aerosol exposure could be due to the decrease of laminin-5 and type IV collagen in the basal membrane (BM). Laminin and collagen type IV are crucial proteins in the BM, because they ensure interaction between the epithelium and the connective tissue [22]. Our analysis of Laminin and collagen type IV production following the exposure of EHOM to e-cigarette aerosol was revelatory as it showed a decrease in both proteins. This is the first study reporting such an effect with gingival mucosa tissue. It is supportive of that study showing diffuse alveolar hemorrhage into the alveolar spaces of the lung secondary to disruption of the alveolar-capillary basement membrane of a patient having used e-cigarettes [1]. The decreased production and deposition of laminin and collagen type IV could explain the deregulation of the gingival mucosa structure after exposure to the e-cigarettes. This could be due to increased MMPs being known to promote extracellular matrix degradation [5]. Our study demonstrated a significant increase in proteolytic enzymes, including MMP-1, MM-2, MMP-3 MMP-9. The increase of these MMPs could explain the gingival tissue and BMP degradation following exposure to e-cigarette aerosols. This study confirmed that cigarette and e-cigarette users have high amounts of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities and protein levels in their bronchoalveolar lavage compared to non-smokers [8]. Also, it has been reported that cigarette smoke directly induced MMP-1 mRNA and protein expression and increased the collagenolytic activity of human airway cells [16]. Altogether, our study and those reported previously confirmed the possible tissue damage through MMPs following exposures to e-cigarette aerosols which may lead to various protein degradation, including those of the basement membrane [5].

Among the key cells producing BM proteins are epithelial cells at the basal and supra-basal layers of the epithelium. With their high dividing capacity, these cells contribute to epithelium renewal through cell proliferation and differentiation. Proliferating cells express specific markers, including Ki67 [20]. In our study, Ki67 production decreased following the exposure of the engineered gingival mucosa to e-cigarette aerosol. This reduction supports the aforementioned structural damage. These results are the first to link e-cigarette aerosols and gingival mucosa tissue damage with an observed reduction in the number of proliferating cells. A similar effect was reported, with nasal mucosa tissue being exposed to e-cigarettes showing a significant decrease of Ki67 positive cells [28]. An increased level of LDH supported the reduction of the Ki67 positive cell number. This enzyme is released into the cell culture medium when the plasma membrane is damaged [32]. The high levels of LDH we demonstrated with this study support the low capacity of the cell to proliferate, as previously reported with nasal epithelial cells [28]. Overall results suggest that e-cigarettes could decrease the local immune defense of epithelial cells.

The effect of the e-cigarette on tissue could induce structural impairment and exacerbate tissue inflammation [29], [39]. These studies are supported by our results demonstrating that e-cigarette aerosol with or without nicotine promoted proinflammatory cytokine (IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, MCP-1, and GM-CSF) secretions. Specifically, the increase of IL-6 we showed with this gingival mucosa model is supportive to those findings showing an increase in IL-6 secretion following the exposure of a respiratory epithelial model to e-cigarettes [4]. The increased secretion of IL-8 following the exposure of oral mucosa tissue to e-cigarette aerosol supports the results of another study in which the in vitro exposure of human nasal airway epithelium to e-cigarette aerosol increased IL-8 levels [28]. The observed increased TNFα level agrees with other studies showing an increased TNFα concentration in peri-implant sulcular fluid when comparing non-users and e-cigarette users [2]. Furthermore, the increased level of MCP-1 following gingival mucosa tissue exposure to e-cigarette aerosol supports other reported findings with nasal ([28].) and alveolar [31] cells exposed to aerosol. E-cigarette aerosol also increased the secretion of GM-CSF. Cigarette smoke was indeed found to increase GM-CSF levels in a mouse model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [34], which agrees with our results with CS and e-cigarette aerosol. Thus, exposure to e-cigarette aerosol induced a proinflammatory response through proinflammatory cytokine secretion. For e-cigarette users, this increased pro-inflammation could promote oral infections, periodontal disease, and caries.

5. Conclusion

Using an engineered human gingival mucosa model consisting of stratified epithelium and fibroblast-populated connective tissue, we demonstrated that the aerosol of e-cigarettes deregulated tissue structure and increased the production of MMPs. E-cigarette aerosol decreased Ki67+ epithelial cells number and basement membrane proteins (laminin 5 and type-IV collagen). The e-cigarette aerosols increased the levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Overall, this study showed that e-cigarette use could significantly damage the oral mucosa tissues.

Funding source

This study was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (Grant No. RGPIN-2019–04475) and the Fonds Émile-Beaulieu - La Fondation de l'Université Lava (Grant No. FO123458).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

All authors participated in the design and interpretation of this study, analysis of the data, and review of the manuscript.

Handling Editor: Lawrence Lash

Data Availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Agustin M., Yamamoto M., Cabrera F., Eusebio R. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage induced by vaping. Case Rep. Pulmonol. 2018;2018:9724530. doi: 10.1155/2018/9724530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AlQahtani M.A., Alayad A.S., Alshihri A., Correa F.O.B., Akram Z. Clinical peri-implant parameters and inflammatory cytokine profile among smokers of cigarette, e-cigarette, and waterpipe. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2018;20(6):1016–1021. doi: 10.1111/cid.12664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao X., Wang Y., Xiong R., Muskhelishvili L., Davis K., Richter P.A., Heflich R.H. Cigarette whole smoke solutions disturb mucin homeostasis in a human in vitro airway tissue model. Toxicology. 2018;409:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czekala L., Simms L., Stevenson M., Tschierske N., Maione A.G., Walele T. Toxicological comparison of cigarette smoke and e-cigarette aerosol using a 3D in vitro human respiratory model. Regul. Toxicol. Pharm. 2019;103:314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vega R.G., Sanchez M.L.F., Eiro N., Vizoso F.J., Sperling M., Karst U., Medel A.S. Multimodal laser ablation/desorption imaging analysis of Zn and MMP-11 in breast tissues. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018;410(3):913–922. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0537-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebersole J., Samburova V., Son Y., Cappelli D., Demopoulos C., Capurro A., Pinto A., Chrzan B., Kingsley K., Howard K., Clark N., Khlystov A. Harmful chemicals emitted from electronic cigarettes and potential deleterious effects in the oral cavity. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020;18(41) doi: 10.18332/tid/116988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerdes J., Lemke H., Baisch H., Wacker H.H., Schwab U., Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J. Immunol. 1984;133(4):1710–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh A., Coakley R.D., Ghio A.J., Muhlebach M.S., Esther C.R., Jr, Alexis N.E., Tarran R. Chronic e-cigarette use increases neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloprotease levels in the lung. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019;200(11):1392–1401. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0615OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon T., Karey E., Rebuli M.E., Escobar Y.H., Jaspers I., Chen L.C. E-cigarette toxicology. Annu Rev. Pharm. Toxicol. 2022;62:301–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-042921-084202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gusterson B.A., Monaghan P. Keratinocyte differentiation of human buccal mucosa in vitro. Invest Cell Pathol. 1979;2(3):171–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabba S.V., Diaz A.N., Erythropel H.C., Zimmerman J.B., Jordt S.E. Chemical adducts of reactive flavor aldehydes formed in e-cigarette liquids are cytotoxic and inhibit mitochondrial function in respiratory epithelial cells. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22(Suppl 1):S25–S34. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jha P. Avoidable deaths from smoking: a global perspective. Public Health Rev. 2011;33:569–600. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lerner C.A., Rutagarama P., Ahmad T., Sundar I.K., Elder A., Rahman I. Electronic cigarette aerosols and copper nanoparticles induce mitochondrial stress and promote DNA fragmentation in lung fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;477(4):620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liede K.E., Haukka J.K., Hietanen J.H., Mattila M.H., Rönkä H., Sorsa T. The association between smoking cessation and periodontal status and salivary proteinase levels. J. Periodontol. 1999;70(11):1361–1368. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.11.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madison M.C., Landers C.T., Gu B.H., et al. Electronic cigarettes disrupt lung lipid homeostasis and innate immunity independent of nicotine. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129(10):4290–4304. doi: 10.1172/JCI128531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercer B.A., Kolesnikova N., Sonett J., D'Armiento J. Extracellular regulated kinase/mitogen activated protein kinase is up-regulated in pulmonary emphysema and mediates matrix metalloproteinase-1 induction by cigarette smoke. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(17):17690–17696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikheev V.B., Brinkman M.C., Granville C.A., Gordon S.M., Clark P.I. Real-time measurement of electronic cigarette aerosol size distribution and metals content analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016;18(9):1895–1902. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molnár E., Lohinai Z., Demeter A., Mikecs B., Tóth Z., Vág J. Assessment of heat provocation tests on the human gingiva: the effect of periodontal disease and smoking. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2015;102(2):176–188. doi: 10.1556/036.102.2015.2.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris A.M., Leonard S.S., Fowles J.R., Boots T.E., Mnatsakanova A., Attfield K.R. Effects of e-cigarette flavoring chemicals on human macrophages and bronchial epithelial cells. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11107. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naheed S., Holden C., Tanno L., Pattini L., Pearce N.W., Green B., Jaynes E., Cave J., Ottensmeier C.H., Pelosi G. Utility of KI-67 as a prognostic biomarker in pulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niessen C.M. Tight junctions/adherens junctions: basic structure and function. J. Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(11):2525–2532. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishiyama T., Amano S., Tsunenaga M., Kadoya K., Takeda A., Adachi E., Burgeson R.E. The importance of laminin 5 in the dermal-epidermal basement membrane. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2000;24(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(00)00142-0. S51-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Farrell H.E., Brown R., Brown Z., Milijevic B., Ristovski Z.D., Bowman R.V., Fong K.M., Vaughan A., Yang I.A. E-cigarettes induce toxicity comparable to tobacco cigarettes in airway epithelium from patients with COPD. Toxicol. Vitr. 2021;75 doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2021.105204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pelaez-Prestel H.F., Sanchez-Trincado J.L., Lafuente E.M., Reche P.A. Immune tolerance in the oral mucosa. Int J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(22):12149. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pozzi A., Yurchenco P.D., Iozzo R.V. The nature and biology of basement membranes. Matrix Biol. 2017;57–58:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouabhia M., Allaire P. Gingival mucosa regeneration in athymic mice using in vitro engineered human oral mucosa. Biomaterials. 2010;31(22):5798–5804. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouabhia M., Park H.J., Semlali A., Zakrzewski A., Chmielewski W., Chakir J. E-cigarette vapor induces an apoptotic response in human gingival epithelial cells through the caspase-3 pathway. J. Cell Physiol. 2017;232(6):1539–1547. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25677. Epub 2016 Nov 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouabhia M., Piché M., Corriveau M.N., Chakir J. Effect of e-cigarettes on nasal epithelial cell growth, Ki67 expression, and proinflammatory cytokine secretion. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020;41(6) doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaunaman N., Crue T., Cervantes D., Schweitzer K., Robbins H., Day B.J., Numata M., Petrache I., Chu H.W. Electronic cigarette vapor exposure exaggerates the proinflammatory response during influenza A viral infection in human distal airway epithelium. Arch. Toxicol. 2022;7:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00204-022-03305-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semlali A., Witoled C., Alanazi H., Rouabhia M. Whole cigarette smoke increased the expression of TLRs, HBDs, and proinflammory cytokines by human gingival epithelial cells through different signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh D.P., Begum R., Kaur G., Bagam P., Kambiranda D., Singh R., Batra S. E-cig vapor condensate alters proteome and lipid profiles of membrane rafts: impact on inflammatory responses in A549 cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2021;37(5):773–793. doi: 10.1007/s10565-020-09573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sreenivasan P.K., Kakarla V.V.P., Sharda S., Setty Y. The effects of a novel herbal toothpaste on salivary lactate dehydrogenase as a measure of cellular integrity. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2021;25(5):3021–3030. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stöcker W., Bode W. Structural features of a superfamily of zinc-endopeptidases: the metzincins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1995;5:383–390. doi: 10.1016/0959-440X(95)80101-4. doi: 10.1016/0959-440X(95)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanabe N., Hoshino Y., Marumo S., Kiyokawa H., Sato S., Kinose D., Uno K., Muro S., Hirai T., Yodoi J., Mishima M. Thioredoxin-1 protects against neutrophilic inflammation and emphysema progression in a mouse model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. PLoS One. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tokito A., Jougasaki M. Matrix metalloproteinases in non-neoplastic disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1178. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ueha R., Ueha S., Sakamoto T., Kanaya K., Suzukawa K., Nishijima H., Kikuta S., Kondo K., Matsushima K., Yamasoba T. Cigarette smoke delays regeneration of the olfactory epithelium in mice. Neurotox. Res. 2016;30(2):213–224. doi: 10.1007/s12640-016-9617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Tobacco. 2020. May 27, Accessed November 20, 2020. Accessed March 5th, 2022.

- 38.Wright J.L., Tai H., Wang R., Wang X., Churg A. Cigarette smoke upregulates pulmonary vascular matrix metalloproteinases via TNF-alpha signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007;292(1):L125–L133. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00539.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ye D., Gajendra S., Lawyer G., Jadeja N., Pishey D., Pathagunti S., Lyons J., Veazie P., Watson G., McIntosh S., Rahman I. Inflammatory biomarkers and growth factors in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid of e-cigarette users, cigarette smokers, and dual smokers: a pilot study. J. Periodontol. 2020;91(10):1274–1283. doi: 10.1002/JPER.19-0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.