Highlights

-

•

Sourdough fermentation both hydrolyzes GMP and SDS soluble proteins.

-

•

Sourdough fermentation significantly increased the specific volume of WBDF-steamed bread.

-

•

The addition of WBDF brings good antioxidant activity to steamed bread.

-

•

2-Pentylfuran was the most dominant volatile compound.

Keywords: Dietary fiber, Sourdough, SDS-PAGE, MRI, GC–MS

Abstract

This investigation used the sourdough fermentation technique to ferment dough at different WBDF addition levels (0 %, 3 %, 6 %, 9 % & 12 %) and to evaluate the quality of the finished steamed breads. The results show that WBDF addition promotes the hydrolytic behaviour of both GMP and SDS soluble proteins; especially for high molecular weight protein subunits (Mw = 120–80 kDa). MRI images clearly showed the water migration and escape behaviour in the fermented dough at different WBDF levels. Further, it was found that the specific volume of steamed breads increased from 3.75 mL/g to 6.97 mL/g (p < 0.05); the DPPH· scavenging capacity of steamed breads increased from 4.46 % to 9.68 % (p < 0.05). Finally, the GC–MS results demonstrated that the addition of WBDF significantly increased the 2-pentylfuran content in the steamed breads from 0.9 to 182.9 (p < 0.05, in terms of relative peak area).

1. Introduction

There is a worldwide consensus that increasing dietary fiber intake in the diet can help prevent diseases that are common in modern society, such as type 2 diabetes, chronic cardiovascular disease, intestinal inflammation and obesity (Hu et al., 2020, Reynolds et al., 2020). It is well known that the reason for the lack of dietary fiber in commercially available flour is that wheat bran is discarded during the wheat milling process. In recent years, a great deal of work has been done by cereal scientists to reuse the bran. The extraction of wheat bran dietary fiber (WBDF) and its enrichment into flour and flour products is considered one of the most promising methods until the challenge of “wheat bran stabilization” is completely overcome (Ma et al., 2022). However, previous research has shown that the addition of WBDF causes deterioration in the quality of dough and flour products; this is because the most important component of WBDF is insoluble dietary fiber (Liu et al., 2019).

To improve the quality of wholemeal products, sourdough fermentation is considered one of the most effective methods (Gobbetti & Gänzle, 2012). Firstly, the fermentation of sourdough produces a variety of organic acids that lower the pH in the fermentation system and activate some enzymes (Gong et al., 2020); secondly, the macromolecules in whole wheat flour are hydrolyzed or modified by the combination of the acidic environment and enzymes; such as bran proteins, non-starch polysaccharides and cell wall polysaccharides (Gong et al., 2020, Montemurro et al., 2019); whole wheat products will benefit significantly from this improvement in textural properties as well as processing quality (Heiniö et al., 2016, Pei et al., 2020). As WBDF is the most important component of wheat bran, the influence of the fermentation process on the behaviour of WBDF will play a decisive role in the quality of whole wheat products. On this basis, it is necessary to further discuss the specific effects of sourdough fermentation on the quality of WBDF-rich flour products. On the other hand, it is well known that gluten proteins hydrolyze during sourdough fermentation (Thiele et al., 2004); gluten proteins are the main determinants of the rheological properties of wheat dough and the texture of the flour products obtained through direct dough processing. For example, studies have found a high correlation between wheat gluten subunits and wheat glutenin macropolymer (GMP) content in gluten proteins and the quality of flour products (Wang et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2016). After sourdough fermentation, the hydrolysis of gluten proteins, especially GMP, causes changes in the rheological properties of the dough, mainly related to elasticity and viscosity (Arendt et al., 2007, Huang et al., 2021, Scarnato et al., 2017); and has an impact on the specific volume of products such as bread. In addition, the increase in free amino acids after gluten hydrolysis and the production of flavor precursors are thought to contribute to the flavor enhancement of the product (Gänzle et al., 2008).

Steamed bread, as a traditional fermented flour product originating from China, have a high acceptance within East Asia and are a good target product for dietary fiber enrichment. The sourdough technique can also be used for steamed bread systems (Kim et al., 2009); although there has been a gradual increase in research on traditional fermented steamed breads in recent years, in terms of the quality of traditional fermented steamed bread, little is known about the effects of dietary fiber enrichment. In this study, a sourdough fermentation system was constructed using Lactobacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The aim of this study was to assess the effect of WBDF on the quality of sourdough fermented dough and sourdough steamed breads and to provide some new data for the production of high dietary fiber sourdough steamed breads.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

The wheat bran was provided by Henan Jiaqi Co. (Zhengzhou, China), the moisture content of the bran was 14.68 %, the protein content 16.51 %, the starch content 12.04 % and the ash content 5.89 %. Wheat flour was purchased from a local market (Zhengzhou Jinyuan Co. Ltd., Zhengzhou, China). The extraction process of WBDF is referred to Liu et al. (2019); total dietary fiber, moisture, protein, starch and ash content in the WBDF was 85.90 %, 5.24 %, 2.72 %, 3.22 %,1.75 %, respectively. Finally, Shanghai Biology Collection Center (Shanghai, China) provided L. plantarum ATCC 8014 and S. cerevisiae ATCC 9763. All reagents were analytically pure unless otherwise specified.

2.2. Preparation of WBDF-flour samples

For the WBDF-flour samples (Control-0 %, 3 %, 6 %, 9 %, and 12 %), WBDF was mixed with flour at 0 %, 3 %, 6 %, 9 %, and 12 % (w/w) concentrations in a mixer (JF-300 Rotary Mixer, Worcestershire Industrial Instruments Ltd., Guangzhou, China) at 100 rpm for 5 min.

2.3. Preparation of sourdough system

The sourdough was prepared according to a previous study (Wang et al., 2021). Briefly, Lactobacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae were cultured to log9.0 CFU/mL and log7.0 CFU/mL, respectively, and equal volumes of medium were maintained; the two microbial cells were then mixed, centrifuged and washed, and an equal volume of sterile water was added. The prepared sourdough is considered a type II sourdough.

2.4. Preparation of fermented dough and steamed bread

Initially, 400.00 g WBDF-flour samples with different WBDF levels were taken; the prepared sourdough was added to the weighed mixes at 75 % water absorption of the mixes (according to the results in Table S1), separately. Next, the dough samples were formed by mixing the dough in a dough mixing machine (Hauswirt-M6, Hanshang Electric Appliance Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China) at 80 rpm for 6 min and dividing the dough into four equal portions. The dough samples were then numbered in the original order and placed in a rising oven, set at 30 °C and 80 % humidity. After fermentation, take one dough sample at each WBDF level, freeze dry it for 48 h, and then grind it to powder that can pass the 100-mesh sieve. Finally, the remaining fermented dough was steamed for 20 min to obtain sourdough steamed breads at different WBDF levels.

2.5. Determination of glutenin macropolymer content

Weigh 4.00 g each of the dough lyophilized powder samples and suspend them in 100 mL of 1.5 % (m/v) SDS solution, stirring magnetically for 30 min at room temperature to ensure complete dispersion. The supernatant was discarded and the gel layer (GMP gel) above the starch precipitate was scraped off and transferred to a test tube for freeze-drying. The nitrogen content of the gel was determined using a fully automated Kjeldahl nitrogen tester, where the protein content was used as an approximation of the glutenin macropolymer content (Mueller et al., 2016).

2.6. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis experiment

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) electrophoresis experiments were performed using the method of Si et al. (2021), with slight modifications. Briefly, 5 mg of each dough lyophilized powder sample was accurately weighed and dissolved in 1 mL of pre-prepared loading buffer (pH = 6.8, 0.125 M Tris-HCl; the buffer contained 2 % SDS (w/v), 10 % glycerol (v/v) and 0.1 % bromophenol blue (w/v)), mixed well and left at 25 °C for 3 h. The suspension was then boiled for 5 min and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 20 min. For the determination of reducing samples, 1 % dithiothreitol (DTT, w/v) was added to the extraction buffer and the rest of the conditions were the same.

2.7. Magnetic resonance imaging

Water distribution and migration processes were observed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). During the tests, fresh dough samples of uniform size were taken and sealed in PET/PE bags to avoid contact with air and water dissipation. The parameters used to perform the MRI experiments were set as follows: repetition time TR = 800 ms, echo time TE = 14 ms, layer thickness 10 mm, number of scans NS = 3, total scan time 313 s, image resolution 256 × 256. The proton density images of the samples were processed using Osiris software.

2.8. Determination of specific volume of sourdough steamed breads

Refer to Chinese National Standards GB/T 35991-2018.

2.9. Determination of the color of sourdough steamed breads

The color of the steamed breads was determined using a SMY-2000 colorimeter (Shanghai Leao Test Instrument Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). Three color data can be quantized, including L* (- black to +white), a* (- green to +red), and b* (- blue to +yellow).

2.10. Determination of antioxidant activity of sourdough steamed breads

Characterization of the antioxidant activity of WBDF sourdough steamed breads using a 1,1-diphenyl-2-nitrophenylhydrazine (DPPH·) scavenging assay (Zhu et al., 2010). The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a UV–vis spectrophotometer and zeroed with anhydrous ethanol; 2 mL of DPPH· standard solution was mixed with 2 mL of anhydrous ethanol and the absorbance was measured as A0; 2 mL of sample solution + 2 mL of anhydrous ethanol was mixed and the absorbance was measured as An; 2 mL of DPPH· standard solution + 2 mL of sample solution was mixed and left to stand for 30 min protected from light. The absorbance was measured as Am for 30 min. Antioxidant activity was calculated as follows:

| DPPH• radical scavenging activity (%) = [1 − (Am − An)/A0] × 100 | (1) |

2.11. Determination of volatile compounds in sourdough steamed breads

Headspace-solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME): 3.00 g of the steamed bread core was weighed and placed in an extraction vial at 60 °C in a constant water bath. The extraction head (50/30 µm DVB/Carboxen/PDMS) was simultaneously inserted into the gas chromatograph (GC) inlet for 30 min. After aging, the extraction head was inserted into the headspace vial and maintained in a constant temperature water bath at 60 °C for 60 min. The extraction head was then removed and quickly inserted into the GC inlet for manual injection and the volatile components were resolved at 250 °C for 5 min.

GC conditions: column temperature 40 °C, hold for 4 min, ramp up to 230 °C at a programmed setting of 6 °C/min, hold for 12 min, inlet temperature 250 °C. A flow rate of 1.0 mL/min of high purity helium was used as a carrier gas. The injection mode was non-split. Mass spectrometry (MS) conditions: ion source temperature set to 230 °C, transmission line temperature to 280 °C, ionisation mode EI, electron energy 70 eV, mass spectrometry scan range (m/z): 33–500 amu. Data acquisition mode was full scan mode.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All procedures were repeated three times. Analysis of variance was used to detect significant differences (p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance was performed using Tukey’s method in SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Changes in GMP content

Gluten is the main component of wheat protein, accounting for 80 % to 85 % of wheat protein, and it is composed of glutenin in polymer form and gliadin in monomer form. Among them, glutenin is composed of high molecular weight glutenin subunit (HMW-GS) and low molecular weight glutenin subunit (LMW-GS). According to the solubility in SDS, gluten can be divided into two parts, and the insoluble gel layer formed in SDS is called GMP. The molecular weight of GMP is 80–120 kDa, and it is composed of HMW-GS and LMW-GS, which are connected by disulfide bonds to form an elastic particle gel with a diameter of 5–50 μm. It is believed that the content of GMP is directly related to the quality of steamed bread (Wang, Guo et al., 2016).

As mentioned above, protein hydrolysis is one of the key actions during sourdough fermentation that has an impact on the overall sourdough food quality (Thiele et al., 2004). As can be seen in Fig. 1, the GMP content in the samples with added WBDF was significantly lower (p < 0.05) compared to the control samples, and the dough samples with 9 % and 12 % WBDF added had the lowest GMP content. That is, WBDF did promote the depolymerization of GMP in the dough after fermentation. Previous studies have shown that the main cause of proteolysis in fermented sourdough is pH-dependent activation of grain enzymes (especially proteinase) through changes in proteolytic activity (Yin et al., 2015). Among them, the protease that degrades gluten has the best activity at pH = 4.0, and the hydrolysis of gluten is not controlled by lactobacillus-specific protease (Bleukx & Delcour, 2000). The ability of WBDF to promote the reduction of pH and the growth and reproduction of microorganisms in the fermentation system may be the reason for the depolymerization of GMP in dough samples (Wang et al., 2022).

Fig. 1.

The effect of different WBDF contents on the GMP content in the fermented doughs.

3.2. Changes of protein molecular weight in SDS-PAGE

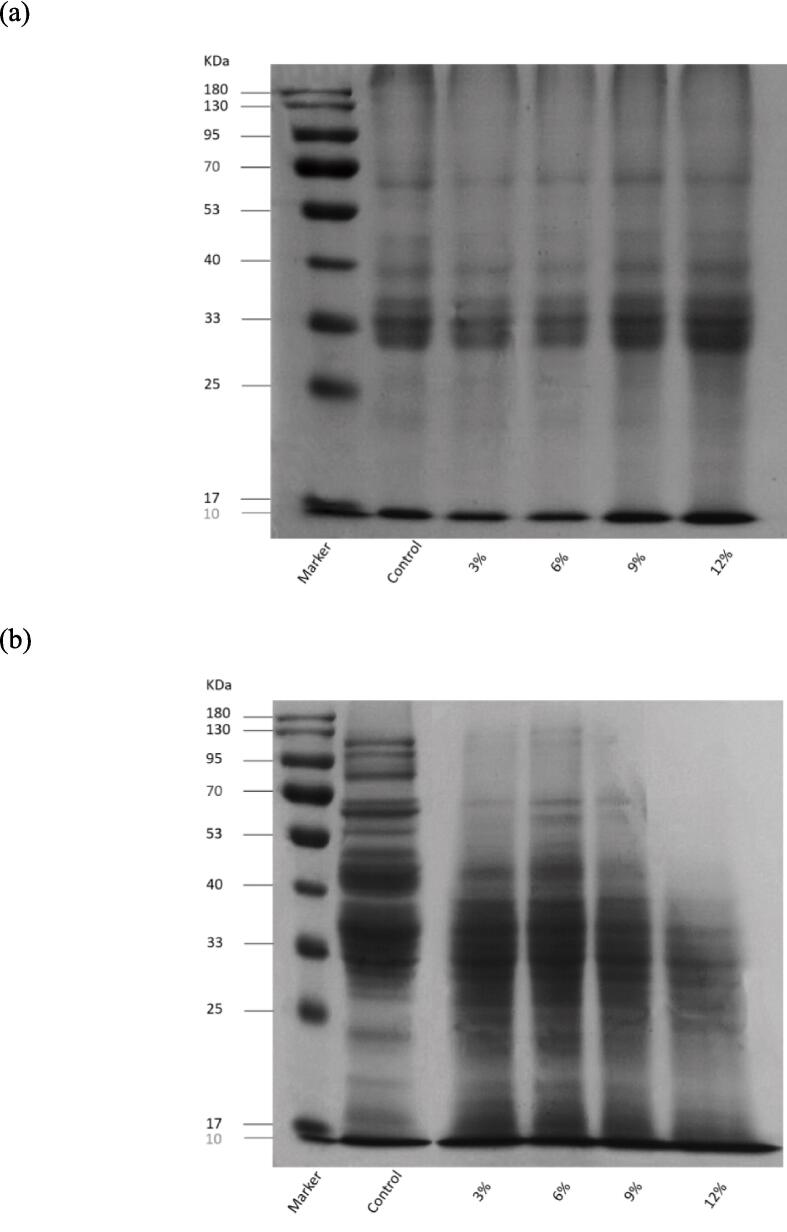

To determine whether WBDF has any effect on the protein composition of the fermented dough via sourdough, the SDS soluble proteins in the dough were analysed by SDS-PAGE technique. Fig. 2 shows SDS-PAGE electropherograms of fermented doughs with different WBDF contents under non-reducing conditions (a) and reducing conditions (b), respectively.

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE electrophoresis images of fermented doughs with different WBDF contents.

As can be seen in Fig. 2a, under non-reducing conditions, the differences in protein molecular weight between all samples were not significant and were all concentrated around 33 kDa, with small amounts of protein subunits present at 40 kDa, ∼45 kDa and ∼70 kDa, and no significant protein bands were present in any of the lanes below 33 kDa.

In contrast, significant differences in protein hydrolysis were observed between samples with different WBDF contents in the presence of reducing conditions (Fig. 2b). According to research theory, glutenin monomer subunits are soluble in alcohol-water mixtures when the disulfide bonds between subunits are treated with reducing agents; based on their mobility in SDS-PAGE, glutenin subunits are divided into four groups A (HMW-GS 120–80 kDa), B (LMW-GS 52–43 kDa), C (LME-GS 43–29 kDa) and D (LMW-GS 72–56 kDa) groups (Ruiz & Giraldo, 2021). Comparison of LMW-GS sequences at the protein and gene levels showed that group C was associated with α- and γ-gliadins, group D with ω-gliadins, and group B with a typical LMW-GS structure (Shewry et al., 2003). In the control samples, protein subunits from all four groups A-D were present, while group A was absent in the samples containing WBDF; in particular, both groups A and D were absent at 12 % WBDF addition. It can therefore be concluded that the addition of WBDF did result in the intermolecular disulfide bonds between protein subunits becoming more susceptible to reduction by reducing agents. In contrast, group A, HMW-GS, was present in the control samples but not in the samples containing WBDF; no distinct bands were observed on the high molecular weight regions, which could mean that the WBDF-containing gluten proteins are more inclined to polymerize during hydration through inter- or intra-chain disulfide bonds, forming protein aggregates. However, further experiments are needed to find evidence for this conjecture. On the other hand, during sourdough fermentation, some subunits of gluten proteins are degraded to peptides of smaller molecular weight (<25 kDa). These peptides are mainly used by microorganisms to meet their amino acid requirements; during the fermentation of sourdough, oligopeptide translocation is thought to be the main route for nitrogen to enter the microbial cells, which may provide nutrition for the growth of Lactobacillus with a variety of amino acids (Kunji et al., 1996). Our findings provide new evidence as to why high levels of insoluble dietary fiber cause deterioration in the quality of pasta products. Specifically, increased levels of insoluble dietary fiber would alter the hydrolytic behaviour of gluten proteins during dough fermentation, and the complex interactions between the different components would destabilize the macromolecular protein aggregates; the altered protein behaviour may become more favorable for microbial growth and reproduction.

3.3. The moisture migration behavior of dough fermentation

Many factors play a key role in the processing, storage and transport of food products. For fermented flour products, the main ones include the recrystallisation of amylopectin, changes in the amorphous structural domains and interactions between other macromolecular components (e.g. proteins and lipids), the equilibrium between stomatal generation and gas escape and so on (Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). The key to these changes is the initial distribution and redistribution of water. MRI techniques allow the full range of flour products to be imaged and analysed in a non-invasive and non-destructive manner. MRI has been used extensively to detect macroscopic water distribution and migration in grains; in recent years MRI techniques have been used to show the internal structure of flour products, which can simplify complex and time-consuming sensory and visual instrumental evaluation processes, such as Calculating the number and porosity of air chambers in fermented doughs.

As shown in Fig. 3, a large number of orange and red pixels are clearly observed in the image of the control sample and are concentrated in the center of the fermented dough; indicating a high level of free water in this local area. After the addition of 3 % WBDF, the images show a decrease in the number of red and orange pixels; the distribution trend shows that the free water in this region begins to spread in all directions. As the level of WBDF continued to increase (6 %, 9 %, 12 %), the number of red and orange pixels decreased further and showed a positive correlation with the level of WBDF, accompanied by a tendency for water to migrate further towards the surface of the dough.

Fig. 3.

MRI images of sourdough fermented doughs with different levels of WBDF.

For the control samples, the dense matrix, which consisted only of starch granules and gluten proteins, was able to retain a large amount of free water before and after fermentation without allowing it to escape. The pattern of water escape in the control samples was that the closer to the surface of the dough, the more water escaped, with water escaping from the outside to the inside. On the other hand, according to previous studies, after adding WBDF to the dough, more of the free water in the dough was adsorbed by WBDF. In other words, the areas where the red and orange pixels gather at this time are also the areas where WBDF gather.

Therefore, two presumptions are based on this conclusion: (1) The addition of WBDF disrupts the dense, homogeneous dough matrix and free water becomes more likely to escape and its distribution is disrupted. The amount of free water retained in the dough was negatively correlated with the level of WBDF. This is clearly detrimental to the subsequent maturing of the dough, especially the pasting of the starch granules in the dough. The quality of the final flour product is inevitably reduced. (2) When macromolecules are incorporated into the dough, they are enriched towards the dough surface as the dough develops/ferments; that is, the closer to the dough surface, the higher the concentration of macromolecules. However, there are very few explanations for the mechanism of this phenomenon. In particular, where does the underlying driving force for this phenomenon come from? The discussion of this mechanism is necessarily complex, and this study suggests that the escape of free water is one of the key drivers of the WBDF to the surface.

3.4. Specific volume and color of sourdough steamed breads

The sensory evaluation of a food product by consumers directly determines its acceptability. The color and specific volume data for sourdough steamed breads with different WBDF contents are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Color and specific volume of the steamed bread with WBDF levels.

| WBDF levels | Specific volume (mL/g) | Color |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | ||

| Control | 3.75 ± 0.03a | 92.43 ± 0.72a | 0.39 ± 0.02f | 18.55 ± 0.05e |

| 3 % | 5.27 ± 0.02b | 84.19 ± 0.21b | 2.26 ± 0.06e | 24.17 ± 0.09d |

| 6 % | 6.97 ± 0.03e | 75.15 ± 0.09c | 2.99 ± 0.08d | 27.15 ± 0.14c |

| 9 % | 6.63 ± 0.01c | 62.77 ± 0.14d | 3.82 ± 0.08c | 29.22 ± 0.12b |

| 12 % | 6.44 ± 0.02d | 56.73 ± 0.76e | 4.20 ± 0.11b | 28.76 ± 0.10a |

Different letters in the superscript indicate significant differences in the same column (p < 0.05).

First, the addition of WBDF improved the specific volume of sourdough steamed bread; This is just the opposite of our previous results under dry yeast fermentation conditions (Ma, Wang, Liu et al., 2021). And when the content of WBDF was 6 %, the specific volume of steamed bread had the maximum of 6.97 (p < 0.05); This may be related to the content of GMP (Fig. 1). When dry yeast is used for dough fermentation, the volume of dough containing WBDF will be significantly smaller than that without WBDF, and the specific volume of dough is negatively correlated with the content of WBDF, which is directly reflected in the small volume, solid texture and low elasticity of steamed bread (Ma, Wang, Liu et al., 2021). Sourdough fermentation just overcomes the deficiency of dry yeast fermentation, so that the volume of steamed bread is not affected by the addition of WBDF. The results of this study proved that sourdough fermentation technology can overcome the problem of low specific volume of high fiber fermented flour products caused by dry yeast fermentation. On the other hand, in terms of color, the L* value of the steamed breads containing WBDF decreased with increasing amounts of WBDF added. This result was also expected as the fermentation of sourdough did not decolorize WBDF. Therefore, the decolorization of WBDF should also be investigated in depth for the early application of WBDF in flour products.

3.5. Antioxidant activity of sourdough steamed breads

The antioxidant active substances in wheat bran have long been of interest to cereal scientists. It has been suggested that wheat bran contains phenolics as its primary bioactive ingredient (Martínez-Tomé et al., 2004), consisting mainly of ferulic acid, coumaric acid and p-coumaric acid. It is generally accepted that the antioxidant activity of wheat bran is mainly related to the antioxidant compounds associated with ferulic acid (Adom et al., 2003). On the other hand, dietary fiber has long been considered as a functional substance with antioxidant activity, and previous studies have focused on dietary fiber from fruits and vegetables, with less assessment of the antioxidant role of dietary fiber from cereals.

In this experiment, the DPPH· radical scavenging ability of the sourdough steamed breads was assessed at different WBDF levels and the results are shown in Fig. 4. As can be seen from the figure, the sample DPPH· radical scavenging ability of the steamed breads showed a significant positive correlation with the WBDF content (p < 0.05). It is generally accepted that the scavenging of DPPH· radicals by antioxidants is due to the hydrogen donor capacity of the compounds (Kikuzaki et al., 2002, Mao et al., 2023). In addition, WBDF with complex chemical side chains also has good hydrogen donor capacity (Lin et al., 2019). Therefore, the addition of WBDF to sourdough steamed breads can confer good antioxidant activity and enhance the nutritional quality of the steamed breads.

Fig. 4.

DPPH· inhibition ability (%) of samples with different WBDF contents.

3.6. Changes in volatile compounds

The search for and identification of flavor substances in wholemeal foods has been one of the most interesting aspects for cereal chemists. Flavour substances in foods are usually divided into volatile and non-volatile compounds; volatile compounds are thought to be associated with olfaction and non-volatile compounds are thought to be associated with taste (Cong et al., 2021). A number of investigations on wholemeal foods have identified a number of major volatile compounds, mainly including acetaldehyde, phenylethylaldehyde, butyraldehyde, isobutyraldehyde, pentanal, isovaleraldehyde, hexanal, heptanal, octanal, crotonaldehyde, butanone, 3-methyl-2-butanone, cyclopentanone, 2,2-dimethyl-3-pentanone, diacetyl, ethyl acetate, pentanol and isoamyl alcohol, etc. (Li et al., 2020, Mcwilliams and Mackey, 1969, Shogren et al., 2003).

In this experiment, volatile compounds were collected using the HS-SPME method and flavor substances were analysed using the GC–MS technique, the database for comparison was NISTLibrary and the results of the assay are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Volatile compounds in the steamed breads with different WBDF content.

| Number | Retention time (min) | Volatile compounds | Relative peak area × 104 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3 % | 6 % | 9 % | 12 % | |||

| 1 | 1.3 | n-pentanol | 9.1 | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | 1.4 | isoamyl alcohol | 11.9 | 32.3 | 5.0 | 10.1 | 10.6 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 2-methylbutanol | 8.2 | 4.3 | 10.0 | 7.6 | - |

| 4 | 1.7 | octane | 100.2 | 176.0 | 183.8 | 192.4 | 197.1 |

| 5 | 4.0 | methyl ether | 0.1 | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | 4.9 | ethanol | 253.1 | 310.8 | 304.9 | 326.3 | 315.7 |

| 7 | 9.5 | n-hexanol | 6.0 | 93.7 | 101.2 | 106.1 | 96.6 |

| 8 | 10.5 | acrolein | 0.1 | - | 0.3 | - | - |

| 9 | 15.1 | 2-Pentylfuran | 0.9 | 94.4 | 172.9 | 154.7 | 182.9 |

| 10 | 15.8 | Ethyl octanoate | 33.3 | 8.6 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| 11 | 16.5 | Acetic acid | 56.8 | 300.5 | 302.8 | 305.2 | 311.4 |

| 12 | 17.0 | benzaldehyde | 20.7 | 35.1 | 29.8 | 27.3 | 27.9 |

| 13 | 17.2 | Limonene | - | 3.5 | - | - | |

| 14 | 17.7 | 2-Methylpropionic acid | 9.1 | - | - | - | - |

| 15 | 18.4 | Phenylacetaldehyde | - | - | 17.1 | 19.4 | 21.0 |

| 16 | 18.9 | Acetophenone | - | - | - | 0.4 | - |

| 17 | 19.0 | 3-Methylbutyric acid | 0.2 | - | 0.5 | - | |

| 18 | 19.6 | 2-Chloro-2-nitroethane | - | - | 0.1 | - | - |

| 19 | 20.1 | caproic acid | 60.2 | 64.1 | 67.4 | 69.0 | 71.6 |

| 20 | 21.0 | 1,2-dioxane-2-methanol | - | 0.3 | - | - | - |

| 21 | 22.5 | oreglan | - | - | - | 0.7 | - |

| 22 | 23.6 | Hexyl isovalerate | - | 1.2 | 3.4 | 2.2 | - |

| 23 | 27.0 | 2-iodopentane | - | - | - | 0.3 | - |

| 24 | 29.0 | 2,2,4-Trimethyl-1,3-pentanediol diisobutyrate | 2.7 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 2.5 | 2.7 |

“-” means not detected.

The results showed that the number of flavor substances obtained from samples with WBDF levels of Control, 3 %, 6 %, 9 % and 12 % were 16, 14, 16, 16 and 11, respectively. The flavor composition of the control samples was very close to what has been reported (Li et al., 2020, Mcwilliams and Mackey, 1969, Shogren et al., 2003), while the samples containing WBDF varied. More specifically, for example, 1,3,4-oxadiazole appeared in 6 %-WBDF of the samples; 2-iodopentane in 9 %-WBDF; and 1,2,4,5-tetrazine in 12 %-WBDF of the samples. And from the finished steamed breads, the flavor of each steamed bread was complex except for the control sample, which had a distinctly sweet taste of steamed breads. Interestingly, the addition of WBDF increased the amount of 2-pentylfuran (in terms of relative peak area) from 0.9 to 182.9 (p < 0.05). 2-Pentylfuran is a volatile compound with a “green”, “fruity” and “bean-like” flavor, and is also an important component of the “wheat flavor”. It is also an important component of the “wheat flavor”. The addition of WBDF may therefore be able to add flavor to the steamed breads. However, it should be noted that the complex sample results reflect complex reaction processes and the related underlying mechanisms need to be further analysed.

4. Conclusions

Traditional fermented steamed breads are good target carriers for WBDF enrichment and the results show that the hydrolytic behaviour of the proteins results from the activation of proteases caused by the decrease in pH during fermentation. And water migration and escape were observed in the fermented dough due to changes in the gluten network and the water holding capacity of WBDF. Furthermore, it was found that sourdough fermentation was able to overcome the decrease in specific volume of the steamed breads caused by the addition of WBDF, but did not significantly enhance the color (Lightness) of the steamed breads. Therefore, the color treatment of WBDF would be a separate issue to be considered. The addition of WBDF also increased the benefits of the sourdough steamed breads in terms of antioxidant activity, as expected. Finally, the results of the investigation showed that the addition of WBDF caused a significant increase in the 2-pentylfuran content of the sourdough steamed breads, but the mechanisms are unclear. The increase of insoluble dietary fiber level will change the hydrolysis behavior of gluten protein during dough fermentation, but whether this process is achieved by stimulating microbial growth and reproduction or by chemical synergy between macromolecules still needs further discussion.

Ethical guidelines

Ethics approval was not required for this research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhen Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. Sen Ma: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Li Li: Methodology, Software, Visualization. Jihong Huang: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32272249), Scientific and Technological Innovation Talents Project of Henan Universities (No. 23HASTIT033), the Key Technology Research, Development and Demonstration Applications for Integrated Development of The Whole Wheat Industry Chain (No. 221100110700), Zhongyuan Scholars in Henan Province (No. 192101510004), Major Science and Technology Projects for Public Welfare of Henan Province (No. 201300110300), National Key Research and development Program of China (No. 2021YFD21009003), Innovation Fund Supported Project from Henan University of Technology (No. 2020ZKCJ11).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100528.

Contributor Information

Sen Ma, Email: masen@haut.edu.cn.

Jihong Huang, Email: huangjh@henu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Adom K.K., Sorrells M.E., Liu R.H. Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activity of wheat varieties. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(26):7825–7834. doi: 10.1021/jf030404l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt E.K., Ryan L.A., Dal Bello F. Impact of sourdough on the texture of bread. Food Microbiology. 2007;24(2):165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleukx W., Delcour J.A. A second aspartic proteinase associated with wheat gluten. Journal of Cereal Science. 2000;32(1):31–42. doi: 10.1006/jcrs.2000.0300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cong W., Schwartz E., Tello E., Simons C.T., Peterson D.G. Identification of non-volatile compounds that negatively impact whole wheat bread flavor liking. Food Chemistry. 2021;364 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gänzle M.G., Loponen J., Gobbetti M. Proteolysis in sourdough fermentations: Mechanisms and potential for improved bread quality. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2008;19(10):513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2008.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbetti M., Gänzle M. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. Handbook on Sourdough biotechnology. [Google Scholar]

- Gong L., Wen T., Wang J. Role of the microbiome in mediating health effects of dietary components. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2020;68(46):12820–12835. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b08231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiniö R.L., Noort M.W.J., Katina K., Alam S.A., Sozer N., de Kock H.L., Hersleth M., Poutanen K. Sensory characteristics of wholegrain and bran-rich cereal foods – A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2016;47:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Ding M., Sampson L., Willett W.C., Manson J.E., Wang M.…Sun Q. Intake of whole grain foods and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from three prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Mao Y., Li H., Yang H. Kappa-carrageenan enhances the gelation and structural changes of egg yolk via electrostatic interactions with yolk protein. Food Chemistry. 2021;360 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Theng A.H.P., Yang D., Yang H. Influence of κ-carrageenan on the rheological behaviour of a model cake flour system. LWT. 2021;136 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Zhao X., Mao Y., Chen L., Yang H. Metabolite release and rheological properties of sponge cake after in vitro digestion and the influence of a flour replacer rich in dietary fibre. Food Research International. 2021;144 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuzaki H., Hisamoto M., Hirose K., Akiyama K., Taniguchi H. Antioxidant properties of ferulic acid and its related compounds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2002;50(7):2161–2168. doi: 10.1021/jf011348w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Huang W., Zhu H., Rayas-Duarte P. Spontaneous sourdough processing of Chinese Northern-style steamed breads and their volatile compounds. Food Chemistry. 2009;114(2):685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunji E.R., Mierau I., Hagting A., Poolman B., Konings W.N. The proteotytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70(2):187–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00395933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Sun H., Zhang M., Wu T. Characterization of the flavor compounds in wheat bran and biochemical conversion for application in food. Journal of Food Science. 2020;85(5):1427–1437. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Chen K., Tu D., Yu X., Dai Z., Shen Q. Characterization of dietary fiber from wheat bran (Triticum aestivum L.) and its effect on the digestion of surimi protein. LWT. 2019;102:106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Ma S., Li L., Wang X. Study on the effect of wheat bran dietary fiber on the rheological properties of dough. Grain & Oil Science and Technology. 2019;2(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gaost.2019.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Wang Z., Liu N., Zhou P., Bao Q., Wang X. Effect of wheat bran dietary fiber on the rheological properties of dough during fermentation and Chinese steamed bread quality. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 2021;56(4):1623–1630. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Wang Z., Liu H., Li L., Zheng X., Tian X., Sun B., Wang X. Supplementation of wheat flour products with wheat bran dietary fiber: Purpose, mechanisms, and challenges. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2022;123:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., Huang M., Bi J., Sun D., Li H., Yang H. Effects of kappa-carrageenan on egg white ovalbumin for enhancing the gelation and rheological properties via electrostatic interactions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;134 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.108031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Tomé M., Murcia M.A., Frega N., Ruggieri S., Jiménez A.M., Roses F., Parras P. Evaluation of antioxidant capacity of cereal brans. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2004;52(15):4690–4699. doi: 10.1021/jf049621s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcwilliams M., Mackey A.C. Wheat flavor components. Journal of Food Science. 1969;34(6):493–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1969.tb12068.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montemurro M., Pontonio E., Gobbetti M., Rizzello C.G. Investigation of the nutritional, functional and technological effects of the sourdough fermentation of sprouted flours. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2019;302:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller E., Wieser H., Koehler P. Preparation and chemical characterisation of glutenin macropolymer (GMP) gel. Journal of Cereal Science. 2016;70:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2016.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pei F., Sun L., Fang Y., Yang W., Ma G., Ma N., Hu Q. Behavioral changes in glutenin macropolymer fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum LB-1 to promote the rheological and gas production properties of dough. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2020;68(11):3585–3593. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b08104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A.N., Akerman A.P., Mann J. Dietary fiber and whole grains in diabetes management: Systematic review and meta-analyzes. PLoS Medicine. 2020;17(3):e1003053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz M., Giraldo P. The influence of allelic variability of prolamins on gluten quality in durum wheat: An overview. Journal of Cereal Science. 2021;101 doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2021.103304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scarnato L., Montanari C., Serrazanetti D.I., Aloisi I., Balestra F., Del Duca S., Lanciotti R. New bread formulation with improved rheological properties and longer shelf-life by the combined use of transglutaminase and sourdough. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2017;81:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.03.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shewry P.R., Halford N.G., Lafiandra D. Genetics of wheat gluten proteins. Advances in Genetics. 2003;49:111–184. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(03)01003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shogren R.L., Mohamed A.A., Carriere C.J. Sensory analysis of whole wheat/soy flour breads. Journal of Food Science. 2003;68(6):2141–2145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb07033.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Si X., Li T., Zhang Y., Zhang W., Qian H., Li Y., Wang L. Interactions between gluten and water-unextractable arabinoxylan during the thermal treatment. Food Chemistry. 2021;345:128785. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele C., Grassl S., Gänzle M. Gluten hydrolysis and depolymerization during sourdough fermentation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2004;52(5):1307–1314. doi: 10.1021/jf034470z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.Y., Guo X.N., Zhu K.X. Polymerization of wheat gluten and the changes of glutenin macropolymer (GMP) during the production of Chinese steamed bread. Food Chemistry. 2016;201:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Lee T.C., Xu X., Jin Z. The contribution of glutenin macropolymer depolymerization to the deterioration of frozen steamed bread dough quality. Food Chemistry. 2016;211:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Ma S., Huang J., Li L., Sun B., Tian X., Wang X. Biochemical properties of type I sourdough affected by wheat bran dietary fiber during fermentation. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 2022;57(4):1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.15327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Yan J., Ma S., Tian X., Sun B., Huang J.…Bao Q. Effect of wheat bran dietary fiber on structural properties of wheat starch after synergistic fermentation of Lactobacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021;190:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Wang J., Yang S., Feng J., Jia F., Zhang C. Protein degradation in wheat sourdough fermentation with Lactobacillus plantarum M616. Interdisciplinary Sciences: Computational Life Sciences. 2015;7(2):205–210. doi: 10.1007/s12539-015-0262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu K., Huang S., Peng W., Qian H., Zhou H. Effect of ultrafine grinding on hydration and antioxidant properties of wheat bran dietary fiber. Food Research International. 2010;43(4):943–948. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2010.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.