Abstract

Background

Apoptosis is a common pathology in malaria and most antimalarial drugs induce apoptosis during chemotherapy. Globimetula braunii is an African mistletoe used for the treatment of malaria but its effect on mitochondria-mediated apoptosis is not known.

Methods

Malarial infection was induced by the intraperitoneal injection of NK 65 strain Plasmodium berghei-infected erythrocytes into mice which were treated with graded doses (100–400 mg/kg) of methanol extract (ME), and fractions of n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethylacetate and methanol (HF, DF, EF and MF) for 9 days after the confirmation of parasitemia. Artequine (10 mg/kg) was used as control drug. The fraction with the highest antiplasmodial activity was used (same dose) to treat mice infected with chloroquine-resistant (ANKA) strain for 5 consecutive days after the confirmation of parasitemia. P-alaxin (10 mg/kg) was used as control drug. On the last day of the treatment, liver mitochondria were isolated and mitochondrial Permeability Transition (mPT) pore opening, mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase (mATPase) activity, lipid peroxidation (mLPO) and liver deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragmentation were assessed spectrophotometrically. Caspases 3 and 9 were determined by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) technique. Cytochrome c, P53, Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), and B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl2) were determined via immunohistochemistry. Phytochemical constituents of the crude methanol extract of Globimetula braunii were determined via the Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis

Results

There was large amplitude mPT induction by malaria parasites, extract and fractions of Globimetula braunii. At 400 mg/kg, HF significantly (p < 0.01) downregulated mATPase activity, and mLPO in both (susceptible and resistant) models, caused DNA fragmentation (P < 0.0001), induced caspases activation, P53, bax and cytochrome c release but downregulated Bcl2 in both models. The GC-MS analysis of methanol extract of Globimetula braunii showed that α-amyrin is the most abundant phytochemical.

Conclusion

The n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii induced mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis through the opening of the mitochondrial pore, fragmentation of genomic DNA, increase in the levels of P53, bax, caspase 3 and 9 activation and cytochrome c release with concomitant decrease in the level of Bcl2. α-Amyrin is a triterpene with apoptotic effects.

Keywords: Globimetula braunii, Malaria, Caspases, Cytochrome c, Apoptosis

Abbreviations: ANOVA, Analysis of variance; ATP, Adenosine triphosphate; Bax, Bcl2-Associated X protein; Bcl2, B cell lymphoma 2; BSA, Bovine serum albumin; CaCl2, Calcium chloride; CuSO4, Copper (II) tetraoxo sulfate (VI); DMSO, Dimethylsulfoxide; DNA, Deoxyribonucleic acid; EDTA, Ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid; EGTA, ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; ELISA, Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FID, Flame ionization detector; GC-MS, Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry; HEPES, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid; HFGB, Hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii; KOH, Potassium hydroxide; mLPO, Mitochondrial lipid peroxidation; mPT, Mitochondrial permeability transition; Na2CO3, Sodium trioxocarbonate (IV); SDS, Sodium dodecysulfate; Tris-HCl, Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane-hydrochloric acid

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

α-Amyrin is the most abundant phytochemical in the methanol extract of the plant, discovered for the first time.

-

•

It causes mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice discovered for the first time.

-

•

It causes DNA fragmentation and opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore.

1. Introduction

It is estimated that worldwide, about 200 million people suffer from Plasmodium infection which causes 619,000 deaths annually. A greater percentage of this malaria-related deaths are pregnant women and children below the age of 5 [1]. During infection, sporozoites inoculated into the skin from anopheles mosquito are transported into the liver where hepatocytes are infected. This is a critical stage where merozoites are released into the blood and clinical symptoms of malaria manifest thereafter [2]. Some scientific studies have focused on the mechanism of action of antimalarial drugs at the erythrocytic stage of parasite development with respect to heme breakdown to hemozoin. For example, chloroquine and other quinolone antimalarials are thought to have an antimalarialeffect via inhibition of heme catabolism by the parasite [3]. The re-orientation of the morphology of liver cells and constituents by the parasite for host’s susceptibility to restrict infection is not fully understood. Given that the liver stage of malarial infection is a critical step in malarial pathogenesis, we focused mainly on this aspect in this study. Furthermore, the emergence of drug -resistant strains of Plasmodium has made treatment of malarial infection difficult and has resulted to high incidences of fatality. In view of this, complimentary medicine has engaged the potentials of certified medicinal herbs to fight this disease and the effects of these drug candidates on the liver stage of malarial infection is not fully understood. Antimalarial properties of different genera of African mistletoe, especially Agelanthus dodoneifolius Pohl and Wiens [4] have been reported. We have provided evidence that the n-hexane fraction Globimetula braunii (Engl van Tieng) has antimalarial properties against susceptible and resistant strains of Plasmodium berghei in vivo and that its active component, friedelan-3-one is the major antimalarial compound as justified by other studies [5], [6]. However, the possible mechanism of action of this medicinal herb and its effects on mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis have not been reported. Host cell death and survival have been implicated in malarial infection [7], [8]. Plasmodium escapes death from the host machinery by subduing hepatocyte apoptosis which the host uses to control infection [9].

Host cell apoptosis protects the host by destroying the reproductive machinery of the invading pathogens. It follows therefore, that for malarial parasites to survive, it must evade host cell apoptosis. Eryptosis is an apoptotic cell death version in erythrocytes and it is an antimalarial mechanism by which mefloquine performs its antimalarial function [10]. Apoptosis in hepatocytes and other cells can occur via cell death receptor or mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. In the latter, there is activation of caspases 3 and 9, caspase-initiated activation of bax, cytochrome c release and mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening [11].

In this study, we investigated the apoptotic mechanism of action of this antimalarial herb via mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis using the n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materia: collection, extraction and partitioning of the crude extract

Globimetula braunii twigs on cocoa were harvested from a cocoa farmland at Igbo-Oloyin area, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria in May, 2018 and dried for four weeks in the laboratory. The leaves were plucked from the twigs, blended and soaked in methanol for 3 days after which the slurry was sieved using a muslin bag and further filtered over a cotton plug in a funnel. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure at 40 °C in a rotary evaporator (Stuat, UK). The remaining solvent in the concentrated methanol extract (ME) was evaporated in a water bath at 40 °C to obtain a solvent-free extract. This was adsorbed on a thin layer chromatography gel and partitioned in order of increasing polarity using n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethylacetate and methanol by vacuum liquid chromatography to obtain their respective fractions (HF, DF, EF and MF). These fractions were concentrated using a rotary evaporator while the remaining solvent residues were evaporated on a water bath at 40 °C to obtain solvent-free fractions that were kept in the refrigerator.

2.2. Swiss mice infection, their grouping and treatment

Eighty-five male Swiss mice (15 ± 3 g) were purchased from the animal house unit of Malaria Research Section of the Institute of Advanced Medical Research and Training, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria, and were fed and kept in the laboratory before the commencement of the experiment for two weeks and were thereafter, intraperitoneally infected with erythrocytes infected with susceptible (NK 65) Plasmodium berghei obtained from a donor mouse (107 inoculum). The volume of infected erythrocytes obtained from the infected mouse, that was used to infect experimental Swiss mice in this study was determined using a hemocytometer. Erythrocyte infection in the experimental mice was confirmed after 3 days by microscopy. The grouped, infected mice (n = 5) were treated orally and once daily for 9 days based on the number of extract and fractions of Globimetula braunii (100,200,400 mg/kg). Infected control was treated similarly with 10 mL/kg (5% (v/v) dimethylsulfoxide, (DMSO)) of the vehicle and P-alaxin (10 mg/kg) was used as the drug control. The fraction that had the highest potency in terms of parasite clearance and the least percentage parasitmia in the susceptible model was used to treat infected mice in the resistant model. Mice infected with the ANKA strain of Plasmodium berghei were treated with the most potent fraction obtained from the susceptible study once daily and orally for five consecutive days after the confirmation of parasitemia and Artequine (10 mg/kg) was used as the standard drug [12].

2.3. Mitochondria isolation from mouse liver

Low ionic strength mitochondria used for mitochondria permeability transition pore assay were isolated using an established protocol [13]. After the mouse was terminated, it was dissected and the liver was removed, rinsed sufficiently with isolation buffer containing 210 mM Mannitol, 70 mM Sucrose, 5 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)− 1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), adjusted to pH 7.4 using potassium hydroxide (HEPES-KOH) and 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), to remove blood stain. The liver was weighed, cut into bits and a cold 10% suspension was homogenized in isolation buffer. The homogenate was poured into centrifuge tubes, loaded into a pre-cooled rotor of a centrifuge (Sigma, 300 K, Germany) at 4 °C and spun twice at 2, 300 rpm for 5 min each time. The sediment containing cell debris and unbroken cells was discarded and the supernatant was spun again once at 13,000 rpm for 10 min to pellet mitochondria. The sedimented mitochondria obtained were re-suspended in sufficient washing buffer containing 210 mM Mannitol, 70 mM Sucrose, 5 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4) and 0.5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), washed twice at 12.000 rpm for 10 min each time and the supernatant discarded. The isolated low ionic strength mitochondria were suspended in the appropriate volume of suspension buffer containing 210 mM Mannitol, 70 mM Sucrose and 5 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4) depending on mitochondrial volume, dispensed into Eppendorff tubes and kept on ice. A similar procedure of isolation was adopted to isolate mitochondria that were used for mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase analysis but 0.25 M sucrose was used as buffer.

2.4. Determination of mitochondrial protein content

The method described by Lowry et al. [14] was employed to determined total mitochondrial protein content. Mitochondria (10 µl) were added to freshly prepared alkaline copper solution (a mixture of 2% sodium trioxocarbonate (iv) (Na2CO3) in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH), 2% Na-K-Tartrate, and 1% copper (II) tetraoxosulfate (vi) pentahydrate (CuSO4.5 H2O) in 100:1:1 proportion, respectively). The assay volume in each test tube was uniformly made up with distilled water and the test tube contents were incubated at room temperature (30 °C) for 10 min. Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (0.3 mL of a five-fold dilution of a 2 N stock) was added and the mixture was then vortexed. The mixture was left for another 30 min and the absorbance was read at 750 nm using a spectrophotometer. Mitochondrial protein content was estimated from a protein standard curve using bovine serum albumin.

2.5. Mitochondria permeability transition assay

2.5.1. Assessment of mitochondrial integrity

This procedure involved the establishment of mitochondrial integrity, viability of isolated mitochondria and their suitability for mPT assay and was determined as follows: mitochondrial protein (0.4 mg/mL) from healthy untreated mouse was pre-incubated in suspension buffer and 8 µM rotenone for 3.5 min after which 5 mM succinate was added and the absorbance read for 12 min at 30 s interval. Similarly, in another experiment, the same mitochondrial protein was pre-incubated in suspension buffer in the presence of rotenone for 3 min after which 3 µM calcium chloride (CaCl2) was added. Sodium succinate was added, thirty seconds later, and the absorbance read. To determine the reversal effect of spermine on calcium-induced mPT opening of the pore, mitochondrial protein was pre-incubated in suspension buffer, rotenone and 4 mM spermine for 3 min after which 3 µM CaCl2 was added. Thirty seconds later, the medium was energized with succinate and the absorbance read at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer. Mitochondria isolates, with negligible changes in absorbance in the absence of calcium, that had large amplitude swelling in the presence of calcium and which was reversed to near normal by spermine were considered intact and could therefore, be used for mPT and other assays [15].

2.5.2. Measurement of mouse liver mitochondria permeability transition pore opening

The mitochondrial protein of mouse liver mitochondria isolated from the Plasmodium-infected but treated mice equivalent to that of the normal control mouse was subjected to the same procedure of mPT determination and the extent of mPT pore opening was quantified under similar condition as stated above. Profile representation of four similar determinations of changes in the absorbance of mitochondria were used for mPT assays.

2.6. Determination of mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase activity at physiological pH

Mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase activity was assessed according to a previously described method [16]. Theprocedure could be described as follows: sucrose (25 mM), Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, with pH adjusted to 7.4 using hydrochloric acid (Tris-HCl, 65 mM, pH 7.4) and potassium hydroxide (KCl, 0.5 mM) were added to test tubes arranged in triplicates and the reaction volume was made up to 1 mL. Mitochondrial protein (0.5 mg/mL protein) was added to the designated tubes followed by the addition of 1 mM adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Tubes were thereafter incubated at 27 ºC, 2, 4-dinitrophenol (25 µM) was added to the test tubes so labelled immediately after ATP was added and 1 mL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) was added to stop the reaction. Reactions in other tubes were stopped by the addition of SDS after the mitochondria containing the enzyme was incubated with the substrate (ATP) in the buffered medium for 30 min. One mL mixture from each tube was separately diluted with water (4 mL) in another set of tubes. Ammonium molybdate (1.0 mL, 1.25%) and 1 mL of 9% ascorbic acid were added, respectively, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, vortexed and the absorbance read at 660 nm in a spectrophotometer. Inorganic phosphate released was quantified using a phosphate standard curve.

2.7. Mitochondrial lipid peroxidation assay

The extent of oxidative damage done to mitochondrial membrane lipids was quantified as follows: mitochondrial protein (0.4 mg/mL) was added to Tris-KCl (1.6 mL) and 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA, 0.5 mL) in test tubes and thereafter, 0.75% thiobarbituric acid (TBA, 0.5 mL) added after which the test tubes were boiled at 80 ºC for 45 min. The boiled test tubes were cooled under a running tap and their contents spun at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was carefully aspirated using a Pasteur pipette into a cuvette and the absorbance read at 532 nm [17]. The malondialdehyde (MDA) level was calculated using its extinction co-efficient [18] of 0.156 µM-1cm-1.

2.8. The DNA fragmentation assay

The extent of genomic DNA fragmentation in the liver was carried out as follows: the 1 g liver sample was homogenized in 20 mL Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Tris-EDTA) buffer and the homogenate was spun for 20 min at 23, 000 rpm. The supernatant was aspirated from the pellet and 3 mL of diphenylamine was added to it while 2 mL of the buffer was added to the pellet. The mixtures in each case were incubated at 37 oC for 24 h and the absorbance was measured at 620 nm [19]. The percentage fragmentation of the genomic DNA was calculated as follows:

2.9. Determination of caspase − 9 and caspase 3 concentrations

The concentrations of the initiator (caspase 9) and executioner (caspase 3) caspases were estimated using liver homogenate as tissue sample and ELISA kit (Elabscience, USA) according to the protocol designed by the manufacturer. Concentrations of caspase-9 and caspase-3 were determined using end point readings in a plate reader and were calculated using a standard curve.

2.10. Determination of Bax translocation, P53, cytochrome c release and Bcl2 levels

Bcl2-associated X protein (Bax), P53, cytochrome c release and B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) levels were determined using an immunohistochemical technique by following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quantitation of Bax, P53, cytochrome c release and Bcl2 proteins assayed using immunohistochemistry was done using image J software.

2.11. Phytochemical profile of the methanol extract of Globimetula braunii using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

The phytochemical profile of the methanol extract of Globimetula braunii using Gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was carried out using an Agilent 7890 n gas chromatograph coupled with mass detector triple Quad 7000 Å with an ion source temperature of 250 oC and an Agilent ChemStation data system. The GC column was equipped with an HP-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) and injector heated at 200 oC and a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) at 230 oC. Initial temperature of the oven was set at 40 oC for 5 min, increased 5 oC/minute to 180 oC for 6 min and then 10 oC/minute to 280 oC for 12 min. Helium was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/minute and the split ratio was 1:20. The GC-MS QP 2010 Plus was used for analysis of the methanol extract with Ion source and interface temperature at 250 oC; solvent cut time 2.5 min with relative detector gain mode and threshold 3000; scan MS ACQ mode; detector FTD; mass range of m/z 40400. Essential components were detected based on their retention indices along with comparison of their mass spectral fragmentation patterns by computer matching with in-built libraries.

2.12. Ethical statement

Animal handling, care and use in this study is in accordance with the care for experimental animals as stated by the National Academy of Sciences in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [20]. The University of Ibadan Animal Care and Use Research Ethics Committee (UI-ACUREC) approved the study and approval number (UI-ACUREC/17/0089) was assigned to the study.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Analysis of data was done using one-way ANOVA and multiple comparison among columns was done using Tukey’s post hoc test. Statistical significance was set at P values less than or equal to 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Extract and fractions of Globimetula braunii elicit different effects on the opening of mitochondrial pore

After 9 and 5 days, respectively, n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii (HF) has the least percentage parasitemia in the resistant and susceptible models of Plasmodium berghei infection. This justifies the use of this fraction for possible apoptotic effects via different mechanisms as presented in this study. The rat liver mitochondrial response via permeability transition pore opening to malarial infection and intervention with solvent fractions of Globimetula braunii is reported in Fig. 1.which shows that liver mitochondria isolated from infected control were susceptible to pore opening with large amplitude swelling as indicated by noticeable decrease in absorbance measured at 540 nm. Comparing the liver mitochondrial response of infected mice to permeability transition pore opening after intervention with the graded dose of extract and solvent fractions of Globimetula braunii, it was discovered that the crude methanol extract (ME) at 100 mg has the highest pore opening effect in the susceptible model. The EF and DF opened the mitochondrial pore with effects similar to that by ME. P-alaxin, the standard drug control, also has pore opening effects at the therapeutic dose administered. HF and MF had the least pore opening effects of all the fractions used (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial pore opening effects of graded doses of extract and fractions of Globimetula braunii at 100 (a), 200 (b) and 400 mg/kg (c) in mice infected with susceptible (NK 65) and resistant (d) (ANKA) strains of Plasmodium berghei. NTA= pore opening in the absence of triggering agent, TA= Pore opening in the presence of triggering agent; (calcium in this case). ME, HF, DF, EF and MF are methanol extract, n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethylacetate and methanol fractions, respectively. Spermine is a standard inhibitor to reverse calcium-induced mitochondrial pore opening. Positive control drugs are P-alaxin and artequine for susceptible and resistant models, respectively while negative (negative control) stands for the infected controls (both susceptible (NK65) and resistant (ANKA).

At 200 mg/kg dose, only ME had a pore opening effect while at 400 mg/kg, DF and MF opened the mitochondrial pore (Fig. 1b and c). The permeability transition pore opening induction at all doses of HF was minimal (100, 200, 400 mg/kg). Similarly, a corresponding increase in the pore opening effects based on the parasite load in the resistant and susceptible models of parasite infection was observed. The pore opening effects of artequine used as drug control in the resistant model was highly negligible (Fig. 1d).

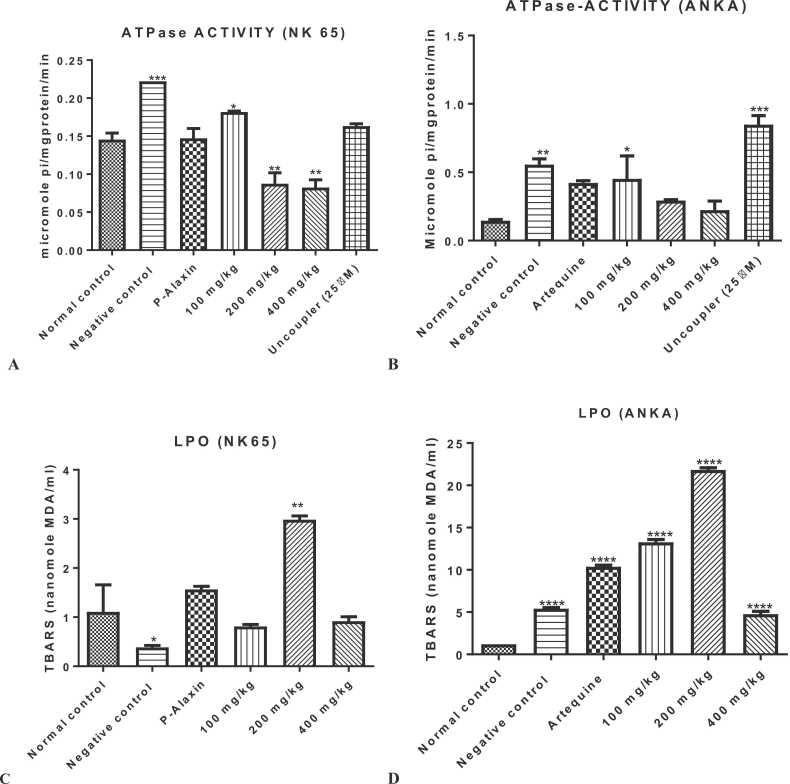

3.2. n-Hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii modulates mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase activity and lipid peroxidation

The influence of n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii (HFGB) on mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase and lipid peroxidation of mice infected with chloroquine susceptible and resistant strains of Plasmodium berghei is presented in Fig. 2. In both susceptible and resistant models, the enhancement of mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase activity decreased dose dependently (P < 0.01 for 200 and 400 mg/kg) in the susceptible model when compared with the normal control. However, 100 mg/kg dose significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced mitochondrial ATPase activity relative to the normal control (Fig. 2a). In the resistant model, similar results were obtained; 100 mg/kg dose significantly (P < 0.05) enhanced ATPase activity while 200 and 400 mg/kg doses reversed the enhancement of the activity of the enzyme caused by Plasmodium infection albeit insignificantly (Fig. 2b). In both models, infection caused by Plasmodium parasites significantly (P < 0.001 for susceptible and P < 0.01 for the resistant) enhanced F0F1 ATPase activity when compared with the normal control. Effects of the hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii (HFGB) on mitochondrial lipid peroxidation in both models of malarial infection are presented in Fig. 2c and d. Interestingly, HFGB caused significant increases in mitochondrial lipid peroxidation in chloroquine susceptible (maximally at 200 mg/kg, Fig. 2c) and resistant (all doses, Fig. 2d) models.

Fig. 2.

Influence of n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii on mitochondrial ATPase activity in chloroquine susceptible (Fig. 2a) and resistant (Fig. 2b) models of malaria as well as the extent of mitochondrial lipid peroxidation in same models of mouse malaria. Enhancement of mitochondrial ATPase activity significantly decreased in both models. N-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii significantly increased mitochondrial lipid peroxidation in both models when compared with the normal control (Fig. 2c and d). * =P< 0.05, * *= P < 0.01, * ** =P< 0.001 and * ** *= P < 0.0001 test groups vs normal control.

3.3. n-Hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii causes DNA fragmentation

When malarial infection was treated with HFGB, there was significant DNA fragmentation in both models (Fig. 3). Specifically in the susceptible model, a dose dependent increase (P < 0.0001) in DNA fragmentation of the test groups relative to the normal control was observed (Fig. 3a) while there was no difference between the fragmentation of genomic DNA in the negative control and treated groups. It is interesting to note also that the antimalarial standard drug also caused significant DNA fragmentation. Similar results were obtained in the resistant model (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Fragmentation of genomic DNA by n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii in the treatment of malaria caused by susceptible (Fig. 3a) and resistant (Fig. 3b) models of malarial infection. * ** *=P< 0.0001 test groups vs normal control.

3.4. n-Hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii enhances caspases 3 and 9 activation in mouse infected with malaria

To fully understand the apoptotic mechanism of HFGB, and to determine whether caspase activation is dose dependent, we assayed for caspases 3 and 9 activation in Plasmodium- infected mice treated with 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg of HFGB in both susceptible and resistant models of Plasmodium infection. At all doses, HFGB enhanced caspase 3 activation more than negative and drug controls. There was no significant difference between caspase 3 activation in the susceptible (Fig. 4a) and the resistant models (Fig. 4b). Similar activation was noticed in caspase 9 both in the susceptible (Fig. 4c) and resistant models (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Caspases 3 and 9 activation by n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii in mice infected with susceptible (NK 65) and resistant (ANKA) strains of Plasmodium berghei. *=P<0.05; * ** *=P<0.0001 test groups vs normal control.

3.5. n-Hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii enhances expression of pro-apoptotic proteins

To further understand the expression of proteins that complement caspase-initiated apoptosis, upregulation of apoptotic P53, bax and cytochrome c release and downregulation of anti-apoptotic bcl2 at low (100 mg/kg) and high (400 mg/kg) dose of HFGB were determined. When compared with the negative control, the release of P53 protein in animals infected with resistant strain of Plasmodium berghei but treated with 400 mg/kg of HF increased than the susceptible model though insignificantly (P>0.05) (Fig. 5a). For cytochrome c release and bax however, the group treated with HF did not have significant (P>0.05) expression when compared with the infected control (Fig. 5b and c, respectively). Anti-apoptotic protein bcl2 was least expressed in the infected control, susceptible and resistant models treated with 400 mg/kg of HF but significantly (P<0.05) expressed in the group treated with 100 mg/kg of HF (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Assessment of P53, cytochrome c, bax and bcl2 release (Fig. 5a-d, respectively) in Plasmodium-infected mice treated with 100 and 400 mg/kg of n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii (mg X400). HF= hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii, R400 and S400 are resistant and susceptible infected mice treated with 400 mg/kg of HF. * =P< 0.05; * *= P < 0.01, * ** =P< 0.001; * ** *= P < 0.0001 test groups vs negative control.

3.6. Phytochemical constituents of Globimetula braunii

The GC-MS analysis of the methanol extract of Globimetula braunii revealed the presence of the following phytochemicals and their respective percentage abundance: α-amyrin (35.63), friedelan-3-one (11.12), Cholesta-4,6-dien-3-one (4.26) and its alcohol derivative; cholesta-4,6-dien-3-ol while the percentage relative abundance of olean-18-ene was 2.44 (Fig. 6). Alpha amyrin derivative; alpha amyrenyl acetate appears at retention times (rT) 30.597 corresponding to peak 89.

Fig. 6.

The GC-MS analysis of the methanol extract of Globimetula braunii showing its major phytochemical constituents.

4. Discussion

Globimetula braunii is used for the treatment of malaria in traditional medicine, but the mechanism of action of its solvent extracts on cell death has not been reported. Here, we evaluated different markers of apoptosis to provide evidence that the antimalarial activity of Globimetula braunii is mediated via apoptotic pathway. Eryptotic cell death is believed to be beneficial in the treatment of malaria since infected erythrocytes are commuted to death. Many eryptotic inducers plausibly have beneficial effects in the treatment of malaria [21] but the effects of unselective cell death induction by these drugs have not been fully documented.

Mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening is one of the mechanisms of apoptosis in nucleated cells. Our previous study [8] and others [7] have shown that mPT induction occurs in Plasmodium infection. Interestingly, we have previously shown that some antimalarial drugs open the mitochondrial pore [22] which may imply one of the mechanisms of action of these drugs. There was pore opening at all doses of HFGB, however, the magnitude was not as pronounced as it was observed with the infected or drug controls. This observation may be the reason for a significant decrease in the enhancement of liver mitochondrial F0F1 ATPase by HFGB since inorganic phosphate release is one of the inducers of mPT [23]. The drugs-induced mPT pore opening represents an onset of apoptosis which may suggest decreased parasite burden and decreased parasite survival [24].

Lipid peroxidation is the hallmark of oxidative stress that is frequently observed in Plasmodium infection as a result of imbalance between pro-oxidants and antioxidant molecules in favour of the former. The host and the parasite are capable of producing both. Indeed, some antimalarial drugs such as chloroquine, primaquine and artemisinin derivatives generate free radicals [25], [26] which may be their mechanism of antimalarial action. Similarly, HFGB elicits its antimalarial effect via this mechanism because of the significant lipid peroxidation observed in this study. Lipid peroxidation plays an important role in the onset and execution of apoptosis via both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Lipid peroxides can interact with membrane receptors to induce signaling for apoptosis and at the same time they can activate the intrinsic pathway [27], [28].

Furthermore, lipid peroxidation can also indirectly lead to apoptosis by crosslinking DNA and causing its fragmentation. Antimalarial action of artesunate for example involves DNA damage initiated by reactive oxygen species [29]. It appears therefore, that apoptosis is a major mechanism of action of some antimalarial drugs. The observed significant DNA fragmentation caused by HFGB prompted us to infer that its antimalarial action may be linked with DNA fragmentation or secondary side effects. The cleavage of chromosomal DNA into oligonucleosomal fragments is an integral part of apoptosis. Although the DNA fragmentation factor is a major endonuclease through which DNA fragmentation can take place, there are other multiple ways, including DNA crosslinking damage and DNA damage caused by lipid peroxidation products [30], [31].

Caspase activation, a hallmark of apoptosis, has been reported in both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways in the infection and treatment of malaria [32], [33], [34]. For instance, the activation of caspase 3-like proteases depicts the execution of apoptosis previously observed in infected hepatocytes [7]. In this study also, HFGB caused activation of caspases 3 and 9 in both susceptible and resistant models of Plasmodium infection. Further, we sought to understand the involvement of apoptosis in this study by evaluating the levels of selected pro-apoptotic markers such as P53, bax and cytochrome c release, and found that they were all upregulated by HFGB. It is interesting to note also that similar trend was noticed when standard antimalarial drug was used. Previous reports showed that hepatic dysfunction is involved in malarial infection which may be responsible for the upregulation of these pro-apoptotic proteins [7]. Indeed, antimalarial drugs such as chloroquine act as apoptotic inducer in the ookinete stage of the parasite. Our study further shows that apoptosis is involved in parasite clearance in the host as proposed by previous authors [24], [29], [35]. However, the reasons for further cell death in uninfected cells in attempt to clear malarial parasite remains a paradox; cell death for host survival, decrease in parasite burden and unfortunately, tissue wastage via death of uninfected cells. It has been discovered that inhibition of B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2), a critical anti-apoptotic protein in hepatocytes, decreased liver stage parasites in infected Hepa 1–6 cell cultures [35]. At the same time, antimalarial drugs cannot be excluded from malarial anemia because they induce apoptosis in nucleated cells [36].

It is interesting that the most abundant phytochemicals in the methanol extract of Globimetula braunii are mostly terpenes which have been previously reported to have antiplasmodial potentials coupled with apoptotic effects. Specifically, triterpenes such as α-amyrin and friedelan-3-one have apoptotic effects [37], [38]. This implies that in addition to their antimalarial property, they also elicit apoptotic effects. Although, malarial parasites induce cell death in its own infected erythrocytes, Plasmodium infection induced eryptosis in bystander, un-infected cells [39]. A similar form of cell death is observed in the liver through mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. Thus, the death of uninfected cells during malarial chemotherapy remains a paradox and demand further studies so that normal cells are spared being commuted to death during malarial treatment to minimize tissue wastage.

5. Conclusion

Apoptosis in malarial treatment, as observed in this study, also occurred when orthodox drugs are used for malarial treatment. Although, regulated apoptosis reduced parasite load in malaria treatment by commuting infected cells to death, excessive apoptosis is deleterious to cells and it may lead to neurodegenerative diseases or tissue damage. The role of apoptosis in malaria is still very important to reduce parasite burden, but death of normal cells should be minimized. Increase in mPT pore opening in liver mitochondria accompanies parasite clearance and in some cases, such swelling in mitochondria isolated from parasite-free liver is higher in amplitude than in infected cells leading to tissue wastage. It is therefore recommended that the actual dose of n-hexane fraction of Globimetula braunii with therapeutic antimalarial, but minimal apoptotic effects should be used for treatment.

Funding

This study did not receive any financial assistance from any organization.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

OJO designed the study, performed the assays, wrote the draft manuscript and wrote the protocol. MTE feed the animals, perform assays and took part in writing the manuscript. NAK read the manuscript and is the major financier of the article processing charges. OOO supplied equipment and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Professor Olusegun George Ademowo; the Director, Malarial Section, Institute of Advanced Medical Research and Training, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. The authors also acknowledge Mr. F.O. Omotayo of Plant Herbarium Unit, Ekiti State University for the identification of the plant used in this study.

References

- 1.Weiss D.J., Lucas T.C.D., Nguyen M., Nandi A.K., Bisanzio D., Battle K.E., et al. Mapping the global prevalence, incidence, and mortality of Plasmodium falciparum, 2000-17: a spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2019;394:322–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaughan A.M., Kappe S.H.I. Malaria parasite liver infection and exoerythrocytic biology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017;7 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a025486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herraiz T., Guillén H., González-Peña D., Arán V.J. Antimalarial quinoline drugs inhibit β-hematin and increase free hemin catalyzing peroxidative reactions and inhibition of cysteine proteases. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:15398. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51604-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Builders M.I., Uguru M.O., Aguiyi C. Antiplasmodial potentials of the African Mistletoe: agelanthus dodoneifolius Pohl and Wiens. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2012;74(3):223–229. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.106064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bero J., Frederich M., Quetin-Leclercq J. Antimalarial compounds isolated from plants used in traditional medicine. J. Pharm. Pharm. 2009;61:1401–1433. doi: 10.1211/jpp/61.11.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olanlokun J.O., Ekundayo M.T., Olorunsogo O.O. Antimalarial and erythrocyte membrane stability properties of Globimetula braunii (Engle Van Tiegh) growing on cocoa in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021;14:3795–3808. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S317732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guha M., Kumar S., Choubey V., Maity P., Bandyopadhyay U. Apoptosis in liver during malaria: role of oxidative stress and implication of mitochondrial pathway. FASEB J. 2006;20:1224–1226. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5338fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olanlokun J.O., Balogun A.A., Olorunsogo O.O. Regulated rutin co-administration reverses mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. Biochem Biophys. Res Comm. 2020;522:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yatim N., Albert M.L. Dying to replicate: the orchestration of the viral life cycle, cell death pathways, and immunity. Immunity. 2011;35:478–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bissinger R., Barking S., Alzoubi K., Liu G., Liu G., Lang F. Stimulation of suicidal erythrocyte death by the antimalarial drug mefloquine. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015;36 doi: 10.1159/000430305. 1395–05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C., Youle R.J. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Ann. Rev. Genet. 2009;43 doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134850. 95-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryley J.F., Peters W. The antimalarial activity of some quinolone esters. Ann. Trop. Med Parasitol. 1970;84:209–222. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1970.11686683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson D., Lardy H. Isolation of liver or kidney mitochondria. Methods Enzym. 1967;10:94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowry O.H., Rosebrough N.J., Farr A.L., Randall R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Bio Chem. 1951;193:262–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapidus R.G., Sokolove P.M. Spermine inhibition of the permeability transition of isolated rat liver mitochondria: an investigation of mechanism. Arch. Biochem Biophys. 1993;306:246–253. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lardy H.A., Wellman H. The catalytic effect of 2,4-dinitrophenol on adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis by cell particles and soluble enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 1953;201:357–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ádám-Vizi V., Seregi A. Receptor independent stimulatory effect of nor-adrenaline on Na, K-ATPase in rat brain homogenate. Role of lipid peroxidation. Biochem. Pharm. 1982;34:2231–2236. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varshney R., Kale R.K. Effects of calmodulin antagonists on radiation-induced lipid peroxidation in microsomes. Int. J. Rad. Biol. 1990;58:733–743. doi: 10.1080/09553009014552121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu B., Ootani A., Iwakiri R., Sakata Y., Fujise T., Amemori S., et al. T cell deficiency leads to liver carcinogenesis in azoxymethane-treated rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2005;231(1):91–98. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark J.D., Gebhart G.F., Gonder J.C., Keeling M.E., Kohn D.F. The 1996 guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. ILAR J. 1997;38(1):41–48. doi: 10.1093/ilar.38.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulet C., Doerig C.D., Carvalho T.G. Manipulating eryptosis of human red blood cells: a novel antimalarial strategy? Front. Cell Infect. Biol. 2018;8:419. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olanlokun J.O., Balogun F.A., Olorunsogo O.O. Chemotherapeutic and prophylactic antimalarial drugs induce cell death through mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in murine models. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2018 doi: 10.1080/01480545.2018.1536139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauer T.M., Murphy E. Role of mitochondrial calcium and the permeability transition pore in regulating cell death. Circ. Res. 2020;126:280–293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaushansky A., Metzger P.G., Douglass A.N., Mikolajczak S.A., Lakshmanan V., Kain H.S., et al. Malaria parasite liver stages render host hepatocytes susceptible to mitochondria-initiated apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolchoz L.J., Gelasco A.K., Jollow D.J., McMillan D.C. Primaquine-induced hemolytic anemia: Formation of free radicals in rat erythrocytes exposed to 6-methoxy-8-hydroxylaminoquinoline. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 2002;303:1121–1129. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haynes R.K., Krishna S. Artemisinins: activities and actions. Microbes Infect. 2004;6 doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.09.002. 1339–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elkin E.R., Harris S.M., Loch-Caruso R. Trichloroethylene metabolite S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-l-cysteine induces lipid peroxidation-associated apoptosis via the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways in a first-trimester placental cell line. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2018;338:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhary P., Sharma R., Sharma A., et al. Mechanisms of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal induced pro- and anti-apoptotic signaling. Biochemistry. 2010;49(29):6263–6275. doi: 10.1021/bi100517x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gopalakrishnan A.M., Kumar N. Antimalarial action of artesunate involves DNA damage mediated by reactive oxygen species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59 doi: 10.1128/AAC.03663-14. 317–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hua Z.J., Xu M. DNA fragmentation in apoptosis. Cell Res. 2000;10:205–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentile F., Arcaro A., Pizzimenti S., Daga M., Cetrangolo G.P., Dianzani C., et al. DNA damage by lipid peroxidation products: implications in cancer, inflammation and autoimmunity. AIMS Genet. 2017;4(2):103–137. doi: 10.3934/genet.2017.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pino P., Vouldoukis I., Koib J.P., Mahmoudi N., Desportes-Livage I., Bricaire F., et al. Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocyte adhesion induces caspase activation and apoptosis in human endothelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187(8):1283–1290. doi: 10.1086/373992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alkahtani S. Different apoptotic responses to Plasmodium chabaudi malaria in spleen and liver. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9(45):7611–7616. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebert G., Lopaticki S., O’Neill M.T., Steel R.W.J., Doerflinger M., Rajasekaran P., et al. Targeting the extrinsic pathway of hepatocyte apoptosis promotes clearance of plasmodium liver infection. Cell Rep. 2020;30(13):4343–4354e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matthews H., Ali M., Carter V., Underhill A., Hunt J., Szor H., et al. Variation in apoptosis mechanisms employed by malaria parasites: the roles of inducers, dose dependence and parasite stages. Malar. J. 2012;11:297. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Totino P.R.R., Daniel-Ribeiro C.D., Ferreira-da-Cruz M.F. Pro-apoptotic effects of antimalarial drugs do not affect mature human erythrocytes. Acta Trop. 2009;112:236–238. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Safe S.H., Pranther P.L., Brents L.K., Chadalapaka G., Jutooru I. Unifying mehanisms of action of the anticancer activities of triterpenoids and synthetic analogs. Antiancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012;12(10):1211–1220. doi: 10.2174/187152012803833099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poofery J., Sripanidkulchai B., Banjerdponghai R. Extracts of Bridelia ovata and Croton oblongifolius induce apoptosis in human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells via oxidative stress and mitochondrial pathways. Int J. Oncol. 2020;56(1):881–889. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.4973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Totino P.R.R., Pinna R.A., De-Oliveira A.C.A.X., Banic D.M., Daniel-Ribeiro C.T., Ferreira-da-Cruz Mde F. Apoptosis of non-parasitised red blood cells in Plasmodium yoelii malaria. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:686–690. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276108062013003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]