Abstract

Rationale

A low respiratory arousal threshold is a key endotype responsible for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) pathogenesis. Pimavanserin is an antiserotoninergic capable of suppressing CO2-mediated arousals without affecting the respiratory motor response in animal models, and thus it holds potential for increasing the arousal threshold in OSA and subsequently reducing OSA severity.

Objectives

We measured the effect of pimavanserin on arousal threshold (primary outcome), OSA severity, arousal index, and other OSA endotypes (secondary outcomes).

Methods

A total of 18 OSA participants were studied in a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Patients received a single dose of placebo or pimavanserin 34 mg 4 hours before in-lab polysomnography. Airflow was measured with an oronasal mask attached to a pneumotachograph, and ventilatory drive was recorded with an intraesophageal electromyography catheter. Results are presented as mean or median changes (Δ) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Pimavanserin did not increase the arousal threshold, nor did it decrease OSA severity or arousal index. It, however, prolonged total sleep time (Δ[confidence interval (CI)], 39.5 [95%CI, −1.2 to 80.1] min). In an exploratory analysis, a subgroup of seven patients who had a 10% or more increase in arousal threshold on pimavanserin exhibited a decrease in AHI4 (hypopneas associated with 4% desaturation) (Δ[CI], 5.6 [95%CI, 3.6–11.1] events/h) and hypoxic burden (Δ[CI], 22.3 [95%CI, 6.6–32.3] %min/h).

Conclusions

A single dose of pimavanserin did not have a significant effect on arousal threshold or OSA severity. However, in a post hoc analysis, a subset of patients who exhibited an increase in arousal threshold on pimavanserin showed a small decrease in OSA severity. Thus, if the arousal threshold could be increased with pimavanserin, perhaps with longer dosing to reach higher drug blood concentrations, then the desired effect on OSA severity might be achievable.

Clinical trial registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04538755).

Keywords: OSA pharmacotherapy, CO2-mediated arousals, hypnotics

Arousal mechanisms play a critical role in the development of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Although considered protective for many patients with OSA (1), arousals have been shown to not be essential for an adequate flow response to a respiratory event in some patients (2). Now, a low arousal threshold, namely the degree of ventilatory drive required to wake up an individual in response to upper airway narrowing and subsequent CO2 and/or drive accumulation, is thought to contribute to OSA for several reasons: 1) it does not provide sufficient time for pharyngeal stimuli to be recruited and to restore airflow (3); 2) frequent ventilatory overshoots after arousal could perpetuate underlying respiratory instability (4); and 3) enhanced sleep fragmentation could prevent the development of deep sleep, which is generally protective against OSA (5).

Recent data (6) suggest that antagonism of a class of serotonin receptors, 5HT2A, present in the dorsal raphe, could suppress CO2-mediated arousals without affecting the respiratory motor response seen after accumulation of CO2 and/or drive. Specifically, when the dorsal raphe of mice was stimulated with CO2-induced arousal from sleep, genetic deletion of serotonin caused the absence of arousals but preserved ventilatory response (7). Thus, an antagonist of 5HT2A receptors would theoretically have the ability to increase the arousal threshold without shutting down the entire response to CO2 as, for example, hypnotics with an affinity for GABA receptors can do (8, 9), with potentially harmful consequences for sleep apnea.

In a previous study, we found that atomoxetine, a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, plus the antimuscarinic oxybutynin significantly lowered the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI), raising the possibility of a potential pharmacologic treatment for OSA (10). These drugs were chosen on the basis of animal research showing that 1) central withdrawal of endogenous norepinephrine is a cause of non-REM (rapid eye movement) sleep-related pharyngeal muscle hypotonia (11); and 2) muscarinic inhibition causes further reductions in pharyngeal muscle tone during REM sleep (12). However, subsequent analyses suggested that atomoxetine may have been the drug primarily responsible for activating the pharyngeal muscles and that oxybutynin acted mostly as a sedative to counteract the wake-promoting effects of atomoxetine (13). Therefore, we hypothesized that a more selective sedative (i.e., one that acts specifically on CO2-mediated arousal mechanisms rather than GABA-ergic mechanisms) and with fewer side effects than oxybutynin could be chosen, and we identified pimavanserin as such a potential drug.

Accordingly, we designed a small randomized trial to test the effect of pimavanserin on the respiratory arousal threshold (primary outcome) measured with gold-standard techniques (i.e., esophageal catheter insertion for the recording of diaphragm electromyography [EMGDI]). We also measured the effect of the drug on OSA severity, arousal index, and other OSA endotypes (described below) as secondary outcomes. Additional comparisons in the sleep parameters between the study nights were considered exploratory.

Methods

Patients

Participants aged 21–70 with a previous diagnosis of moderate-to-severe OSA (AHI ⩾ 15 events/h) were recruited. Exclusion criteria were: any major organ system disease or unstable medical condition, any other sleep-disordered breathing or respiratory disorder, use of medications expected to stimulate or depress breathing (e.g., opioids, acetazolamide, etc.), use of serotonin and/or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, use of medications that lengthen the QT interval, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and severe claustrophobia. This study was designed to be exploratory in nature with the goal of addressing a simple physiological question: does pimavanserin increase the arousal threshold in patients with OSA? Thus, we decided not to preselect participants on the basis of their baseline arousal threshold.

The study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee (2020p002760–1), and it was prospectively registered on clinicaltrails.gov (NCT04538755). All participants provided written informed consent before enrolment. Participants were studied at the Center for Clinical Investigation at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. This investigation was conducted in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Protocol

Patient medications and comorbidities were reviewed in a screening visit that also included an electrocardiogram (EKG) to measure the QTc interval and blood tests to measure magnesium and calcium concentrations. Subsequently, two overnight in-laboratory polysomnograms were performed approximately 1 week apart. Patients received pimavanserin 34 mg or placebo 4 hours before bedtime in a double-blind, randomized, crossover study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram that shows recruitment, randomization, and analysis procedures for the trial.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale was assessed before each night, and a Visual Analog Scale for sleep quality was administered in the morning after each overnight. Potential side effects (e.g., confusion, nausea, etc.) were also investigated in the morning after each visit. Vital signs (i.e., systemic blood pressure and heart rate) were measured before and after (30 minutes after awakening) each overnight.

Study medications were prepared by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Investigational Drug Service and were placed in identical capsules that could not be identified by study personnel or participants. Randomization of the order of active treatment versus placebo was performed by the Investigational Drug Service using a pseudorandom number generator with two randomly permuted blocks of two.

Equipment and Measurements

In addition to standard polysomnography equipment, patients were fitted with an oronasal mask attached to a pneumotachograph (Hans‐Rudolph). Mask pressure (Validyne) was measured via sensors attached to ports in the nasal mask. The ventilatory drive was measured with an intraesophageal catheter (Yinghui Medical Equipment EMG Catheter and 12-GL Amplifier, 1.6 mm diameter) inserted into a decongested and anesthetized nostril and advanced such that the center of its electrode array lay at the level of the crural diaphragm. Nose–ear–xyphoid distances were measured in each individual to facilitate catheter placement. The catheter was advanced to approximately nose–ear–xyphoid + 5 cm initially and then withdrawn slowly to obtain an optimal position on the basis of feedback from the relevant biological signals (assessed when the participant was supine). Catheter position was interpreted by investigators (during preliminary real-time processing) as the pair with the largest respiratory signal (of the five available); the position was adjusted such that the third pair was the strongest, followed by pairs two and four, then pairs one and five. Raw EMG was root-mean–squared and smoothed to provide an integrated diaphragm EMG signal for analysis.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted blinded to the study interventions. Respiratory events and arousals were scored using standard American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2020 criteria (14). Hypopneas were defined as a reduction in flow of 30% or more from baseline, lasting at least 10 seconds, and were associated with arousal from sleep or an oxyhemoglobin desaturation of 3% or greater. In addition, to provide the AHI4, hypopneas were defined when there was an associated 4% or greater oxyhemoglobin desaturation. The hypoxic burden was also computed as the respiratory event-related oxygen desaturation area under the baseline curve before the event (15). We also estimated stable sleep time (i.e., minutes of sleep free of respiratory events), subtracting from total sleep time the number of events per hour multiplied by their average duration.

EMG data were processed by our automated algorithm and manually reviewed to remove cardiac artifacts and to provide a breath-by-breath ventilatory drive signal in liters per minute as previously published (16). In brief, to reveal the underlying ventilatory drive signal to the diaphragm (i.e., free from EKG artifacts), raw EMG signals were first high-pass filtered (40 Hz cut off), processed to remove EKG artifact (template subtraction), and root-mean–squared (25 ms). Breath-by-breath ventilatory drive measures were taken as peak phasic minus tonic (i.e., value at the beginning of inspiration) EMGDI. EMGDI values were then calibrated to provide a ventilatory drive signal with the same unit of ventilation (L/min) using the mean ratio of ventilation and EMGDI during wakefulness breaths to which sleeping values were compared.

Several OSA endotypes, including the respiratory arousal threshold, were calculated using the EMGDI data as follows: arousal threshold was the maximum ventilatory drive during sleep immediately before respiratory-induced arousals (i.e., from hypopneas and/or apneas). VPASSIVE was defined as the ventilation during sleep at the eupneic degree ventilatory drive. Vpassive is a measure of pharyngeal collapsibility when the upper airway muscles are relatively passive. VACTIVE was defined as the degree of ventilation at maximum ventilatory drive (i.e., just before arousal), and it is a measure of pharyngeal collapsibility when the upper airway muscles are activated during sleep. To further characterize the passive pharyngeal collapsibility, VMIN (the ventilation at the lowest decile of ventilatory drive) was also measured. These endotypic traits were expressed as a percentage of VEUPNEA, namely baseline ventilation obtained from periods of resting wakefulness. The endotypes were plotted on a graph of ventilation versus ventilatory drive (Figure 2) (17). Finally, loop gain was calculated as the response to one cycle/minute disturbance (18).

Figure 2.

Endograms of placebo versus pimavanserin nights (subgroup of seven patients that had increased arousal threshold on pimavanserin) illustrate breath-by-breath values of ventilation at different degrees of ventilatory drive (per diaphragm electromyography). Solid lines show the group median values for each degree of ventilatory drive: color varies to illustrate the increased likelihood of a respiratory event at lower ventilation and ventilatory drive (see color bar). Shading denotes the interquartile range on placebo (blue) and pimavanserin (red). The solid purple dots illustrate ventilation near eupneic drive (i.e., VPASSIVE, higher values reflect reduced collapsibility). The solid red dots represent ventilation at degrees of drive preceding arousal (i.e., VACTIVE). VMIN is ventilation at the lowest deciles of the drive. Note that on pimavanserin, VMIN corresponds to VPASSIVE (i.e., pimavanserin prevented dips in the ventilatory drive). Ventilation and drive data are expressed as a percentage of eupneic ventilation during non-rapid eye movement sleep (VEUPNEA; original units: L/min). VEUPNEA = baseline ventilation obtained from periods of resting wakefulness.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the effect of pimavanserin on the respiratory arousal threshold. Secondary outcomes were the effect of pimavanserin on OSA severity, nadir oxygen saturation, arousal index, and the endotypes described above.

The study was powered to detect a physiologically meaningful 20% change in arousal threshold. Assuming a 15% standard deviation (SD), 18 patients were required to allow for 81% power to detect the above difference (α = 0.05); additional patients were enrolled in the study to account for potential dropouts. This many individuals also had enough power to detect meaningful changes in the OSA endotypes on the basis of modeling experiments (19) and previous studies (20, 21).

Primary analysis

The primary and secondary outcome measures were compared between the 2 nights using the Student’s t test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test according to the normality of distribution. Data were expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range [IQR]).

Secondary analyses

In addition to the primary analysis, several secondary analyses were performed. The arousal threshold and AHI differences between the nights were regressed over sex, age, body mass index (BMI) and order of study nights using a linear mixed-model analysis with a random intercept for study participants. In another secondary analysis, adjustments were also performed for supine sleep time, and analysis was repeated for AHI in different sleep stages. Effects of treatment on VMIN, VPASSIVE, and VACTIVE were modeled using a custom nonlinear function (sigmoidal “link” function [13]) designed to handle the known floor and ceiling effects of the collapsibility measures (i.e., improvements in collapsibility cannot be seen above ventilation = 100%, and deficits in collapsibility cannot be seen below ventilation = 0%). Effects on loop gain and hypoxic burden were modeled using simple linear models after square root transformation (data were back-transformed in figures and tables).

Exploratory Analysis

In an exploratory analysis, patients who had a higher arousal threshold on the drug night (~10% or more) were labeled responders, and the same above comparisons were run separately in this subgroup as an exploratory analysis.

Statistical significance was inferred for the primary outcome at P < 0.05. Results of secondary and additional outcomes with P < 0.05 were highlighted; such findings were not adjusted for multiple comparisons and were considered exploratory or explanatory in nature.

Analyses were performed using Matlab (Mathwork), Graph Pad Prism 6.0 (Graph Pad Software), and SPSS 23.00 (IBM).

Results

Twenty patients were enrolled and consented in anticipation of potential dropouts. However, the study ended after the first 18 patients completed both study nights; the 2 extra individuals were not studied. Baseline characteristics and medications are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and medications

| Characteristic | N = 18 |

|---|---|

| Population factors | |

| Age, yr | 53 ± 14 |

| Sex, n | |

| Male | 12 |

| Female | 6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32 ± 7 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 40 ± 5 |

| Race, n | |

| White | 11 |

| Black | 4 |

| Asian | 2 |

| Other | 1 |

| Ethnicity, n | |

| Hispanic | 1 |

| Non-Hispanic | 17 |

| Medications, n | |

| Antihypertensives | 5 |

| Asthma or Allergies | 2 |

| Anxiety or Depression | 1 |

| Sleep aids | 0 |

Definition of abbreviation: BMI = body mass index.

Data are mean ± SD.

Effect of Pimavanserin on OSA Endotypes

Pimavanserin did not change the arousal threshold (primary outcome variable) compared with placebo (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Table 2.

Obstructive sleep apnea endotypes

| Characteristic | Placebo | Pimavanserin | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loop gain* | 0.59 (0.52–0.65) | 0.57 (0.45–0.69) | 0.570 |

| Ventilatory response to arousal, %VEUPNEA* | 17.9 (13.3–22.7) | 16.5 (7.3–25.7) | 0.514 |

| Arousal threshold, %VEUPNEA† | 148.7 (115.5–181.8) | 158.6 (102.8–214.5) | 0.379 |

| VPASSIVE, %VEUPNEA† | 104.3 (85.9–122.7) | 90.6 (54.8–126.4) | 0.120 |

| VMIN, %VEUPNEA† | 82.0 (69.0–94.9) | 89.5 (61.1–118.0) | 0.329 |

| VACTIVE, %VEUPNEA† | 114.5 (94.2–134.8) | 93.6 (55.0–132.2) | 0.026 |

Definition of abbreviations: VACTIVE = ventilation when the pharyngeal muscles are relatively active; VEUPNEA = baseline ventilation obtained from periods of resting wakefulness; VMIN = ventilation at the lowest drive levels; VPASSIVE = ventilation when the pharyngeal muscles are passive.

Data are expressed as mean (confidence interval). Data for VPASSIVE, VMIN, and VACTIVE were derived from the sigmoidal transformation function to handle known floor and ceiling effects. Of note, the difference in arousal threshold between the nights was the primary outcome of the study, whereas the difference in the other endotypes between the study nights was classified as secondary outcomes in our prespecified statistical analysis plan. Values are the percent of stable breathing during sleep (VEUPNEA).

Paired data were not available for two patients (i.e., ventilatory response quantification was possible for only one out of the two nights in two different participants).

Paired data were not available for one patient (i.e., pharyngeal physiology and arousal threshold quantification was possible for only one out of the two nights).

Figure 3.

Arousal threshold (primary outcome) was not different between placebo and pimavanserin nights. Individual data show a highly variable response after pimavanserin administration. Values are means (confidence interval). %VEUPNEA = baseline ventilation obtained from periods of resting wakefulness.

Analysis of the remaining four trait variables (VPASSIVE, VMIN, VACTIVE, and loop gain; secondary outcomes) revealed an unexpected reduction in VACTIVE (mean reduction [confidence interval (CI)], −20.9 [95%CI, −39.2 to −2.7] %VEUPNEA) (Table 2); we emphasize that this reduction would not meet criteria for significance when considering multiple testing. There was no other effect on the remaining OSA endotypes.

Effect of Pimavanserin on OSA Severity and Sleep Parameters

Secondary outcomes

Pimavanserin did not change OSA severity (Table 3 and Figure 4). AHI was unchanged between the nights regardless of sleep stage or sleeping position. Alternative use of 4% desaturation criteria did not change these findings (Table 3). Results were also similar after adjusting for treatment sequence (“order”) and patient characteristics (sex, BMI, and race) per mixed models. Other measures of OSA severity, including hypoxic burden, nadir oxygen desaturation, and oxygen desaturation index were also unchanged (Table 3).

Table 3.

Obstructive sleep apnea parameters—exploratory comparisons

| Characteristic | Placebo | Pimavanserin | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHI, events/h | 30.5 (28.6) | 17.9 (39.5) | 0.284 |

| AHI4, events/h | 8.8 (23.8) | 6.5 (18.7) | 0.119 |

| AHI supine, events/h | 27.4 (42.4) | 31 (32.0) | 0.963 |

| Supine sleep, % total sleep time | 72.9 (46.1) | 81.1 (41.1) | 0.339 |

| NREM AHI supine, events/h | 29.5 (27.3) | 17.6 (40.5) | 0.325 |

| REM AHI supine, events/h* | 32.2 (38.5) | 43.4 (34.6) | 0.893 |

| Total sleep time, min | 285.5 ± 94.4 | 325.0 ± 73.5 | 0.007 |

| Sleep efficiency | 75.1 (13.3) | 83.8 (17.7) | 0.108 |

| N1, % total sleep time | 34.1 ± 19.4 | 29.0 ± 17.6 | 0.179 |

| N2, % total sleep time | 48.1 ± 15.8 | 49.7 ± 14.6 | 0.652 |

| N3, % total sleep time | 5.1 (8.3) | 10.4 (16.6) | 0.120 |

| REM sleep, % total sleep time | 10.5 (14.2) | 7.2 (9.0) | 0.551 |

| Arousal index, events/h | 41.0 ± 21.5 | 37.9 ± 21.9 | 0.524 |

| Respiratory event duration, s | 29.2 ± 7.5 | 30.1 ± 6.7 | 0.565 |

| O2 desaturation index, events/h | 18.7 (31.1) | 11.3 (12.8) | 0.142 |

| Mean O2 saturation during sleep, % | 93.9 ± 2.3 | 93.9 ± 2.5 | 0.552 |

| Nadir O2 saturation, % | 86 (11) | 82 (13) | 0.073 |

| Hypoxic burden, %min/h | 51.4 (63.2) | 38.1 (56.1) | 0.130 |

| Sleep time spent <90% SpO2, % total | 0.7 (4.1) | 1.9 (6.2) | 0.678 |

| Estimated stable sleep time, min | 202.5 ± 97.1 | 243.9 ± 88.2 | 0.040 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130.7 ± 16.2 | 131.4 ± 14.5 | 0.825 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 72.2 ± 11.2 | 74.7 ± 10.7 | 0.255 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 67.8 ± 11.1 | 82.4 ± 18.3 | 0.085 |

| Visual Analog Scale for sleep quality | 6 (2) | 5 (1) | 0.013 |

Definition of abbreviations: AHI = apnea–hypopnea index; AHI4 = number of events per hour associated with 4% oxygen desaturation; NREM = non-REM; REM = rapid eye movements.

Data are mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) when appropriate and were compared with a two-tailed paired Student’s t test or a Wilcoxon signed-rank test according to statistical distribution. Blood pressure, heart rate, and Visual Analog Scale for Sleep Quality measurements refer to next-day values. Stable sleep time was estimated by subtracting from total sleep time the number of events per hour multiplied by their average duration.

Values were not available for four patients on placebo (three patients did not have REM) and two on pimavanserin (both without REM).

Figure 4.

There was no difference in AHI between the study nights. Individual data illustrate a wide range of AHI values on the placebo night and an inconsistent response after pimavanserin administration. Values are medians (interquartile range). AHI = apnea–hypopnea index.

Additional outcomes

We observed no increase in sleep efficiency with pimavanserin. Notably, we observed a greater total sleep time with pimavanserin versus placebo (mean increase [CI], 39.5 [95%CI, −1.2 to 80.1] min) (Table 3). There were no changes in sleep architecture detected.

Safety

Pimavanserin did not change next-morning systemic blood pressure or heart rate compared with placebo, although there was a large but statistically insignificant increase in heart rate on pimavanserin. In addition, pimavanserin reduced next-morning subjective sleep quality (per Visual Analog Scale) (Table 2). There were no adverse events or complaints related to pimavanserin (one patient reported dry eyes on the placebo night).

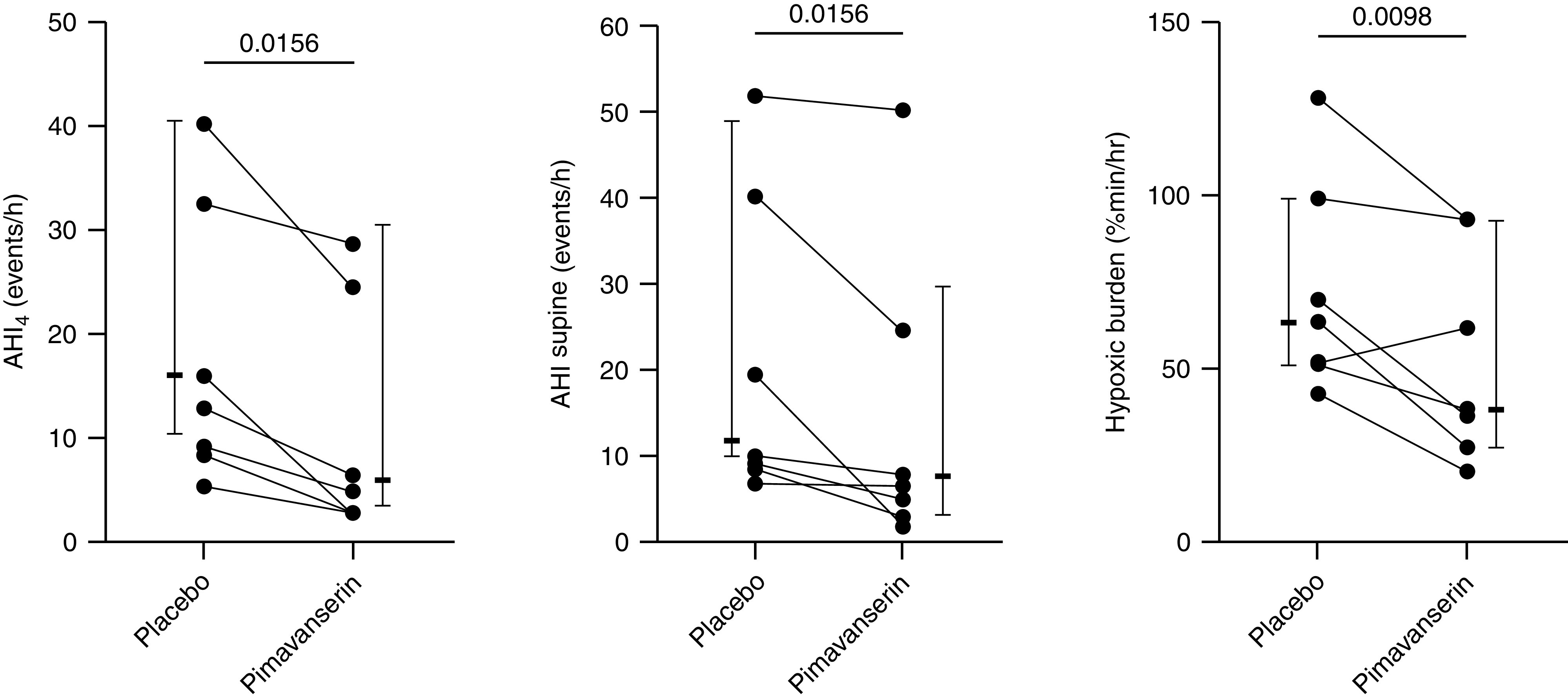

Subgroup Exploratory Analysis

Five patients had no change in arousal threshold on the treatment night versus placebo (percent change = −10 to 10), five showed reduced arousal threshold (percent change = ⩽−10), and seven had an increase in arousal threshold on pimavanserin = ⩾10%. In one patient, paired data for arousal threshold were not available. We conducted exploratory analyses to examine the effect of pimavanserin on primary measures of OSA severity in patients who had an increased arousal threshold on treatment. The reason for performing this post hoc analysis was to investigate the large, albeit nonsignificant, AHI and hypoxic burden drop on pimavanserin versus placebo (median AHI fell from 30.5 to 17.9 events/h and median hypoxic burden fell from 51.4 to 38.1 %min/h) (Table 3). We found that several people who had reduced AHI on pimavanserin also had an increase in arousal threshold, suggesting that there could be a link between these two parameters in some individuals. We found no relationship between AHI and arousal threshold in the group as a whole and no difference in AHI between the study nights in the subgroup of patients who had an increase in arousal threshold on pimavanserin. However, we observed reductions in the following measures of OSA severity in the subgroup of patients with increased arousal threshold on pimavanserin (Figure 5): AHI4 (median reduction [CI], 5.6 [95%CI, 3.6–11.1] events/h), AHI supine (median reduction, 4.3 [1.6–12.0] events/h) and hypoxic burden (median reduction, 22.3 [6.6–32.3] %min/h). In responders, pimavanserin also promoted an increase in VMIN versus placebo (mean increase [CI], 21.9 [95%CI, 3.7–40.1] %VEUPNEA; P = 0.022). However, VACTIVE was still reduced on pimavanserin (mean reduction, −24.3 [−35.9 to −12.7] %VEUPNEA; P < 0.001). Interestingly, Visual Analog Scale scores for subjective sleep quality were not different between the nights in participants with a higher arousal threshold on pimavanserin. Of note, there was no change in the main parameters of OSA severity (e.g., NREM AHI, AHI4, AHI supine, hypoxic burden, and oxygen desaturation index) in patients who had a paradoxical drop in arousal threshold on pimavanserin.

Figure 5.

Individual data of pimavanserin responders (those who experienced an increase in arousal threshold of 10% or more of placebo). Indexes of obstructive sleep apnea severity were significantly reduced after exploratory comparisons. Values are medians (interquartile range). AHI = apnea-hypopnea index.

Discussion

With this study, we showed that a single dose of pimavanserin did not have an effect on either arousal threshold (primary outcome) or OSA severity (secondary outcome). It did, however, increase total sleep time in patients who had a greater arousal threshold while on treatment, and it slightly decreased indices of OSA severity, possibly through an increase in VMIN (exploratory). Pimavanserin was well tolerated, as patients had no complaints or side effects while on treatment, even though a reduction in subjective sleep quality on pimavanserin was observed. These findings suggest that pimavanserin could be a safe medication to test in combination with other drugs that have an active profile on pharyngeal muscles but also have wake-promoting properties (e.g., atomoxetine and reboxetine) (10, 22).

Physiological Considerations

Despite our strong neurobiological rationale, pimavanserin did not meet the primary outcome of increasing the arousal threshold versus placebo. A potential explanation for this could be that pimavanserin did not reach a high enough blood concentration to exert its physiological effect. Because of its long half-life (57 h), steady-state plasma concentrations may take up to approximately 12 days to be reached (23). More prolonged administration is potentially required to see an effect of the drug on the arousal threshold. However, a number of patients who “responded” to pimavanserin, namely those who had an increased arousal threshold on the drug night (7/18), had a subsequent reduction in OSA severity indices in post hoc analyses (Figure 5). The percent increase in arousal threshold in these responders (27.7 [19.0], median [IQR]) was well above the threshold for a physiologically meaningful change in this endotype (19), and it was superior to the percent increase seen on zolpidem (15.8 [29.5] in one study, 24.0 [18.2] in another study) (8, 24), thus unlikely to be attributed to night-to-night variability. Also, a first-night effect does not seem to have a role in this finding, as only 4/7 responders received the drug on their second night. Rather, because pimavanserin is metabolized in the liver predominantly by cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4 and CYP3A5) (25), responders might be intermediate-to-poor metabolizers (26), in which a single dose of pimavanserin will still promote its supposed biological effect. Of note, although drug metabolism rate varies considerably because of cytochrome type and ethnicity, CYP3A5 allele mutations with decreased activity are rather prevalent in all populations (27). This is of critical importance, as a longer duration of pimavanserin administration might be able to increase the arousal threshold and reduce OSA severity.

Another contributor to improved upper airway patency, at least in “responders”, was the improved collapsibility, as demonstrated by the increase in VMIN. In responders, pimavanserin prevented the ventilatory drive from dropping (notably, VMIN was equal to VPASSIVE on the treatment nights) (Figure 2). Dips in drive are an important cause of upper airway obstruction in all sleep stages (16, 28). Thus, avoiding ventilation drops when drive falls is an important mechanism to improve pharyngeal physiology and OSA severity. Of note, parameters of OSA severity in responders were substantially improved despite a lower VACTIVE on the treatment night (reasons for this decrement are unclear but possibly related to serotonin being indirectly involved in improving pharyngeal muscle activity in experimental animal models [29]). The double effect of pimavanserin on VMIN and arousal threshold that could potentially promote improvement in OSA severity warrants further investigation in larger population samples and with a longer duration of drug administration.

Clinical Implications

Although we did not find an increase in arousal threshold with a single dose of pimavanserin in this study, pimavanserin did prolong total sleep time by a noteworthy amount in the group as a whole (~40 min), which makes it potentially a good candidate for the treatment of patients with OSA with comorbid insomnia (30). Indeed, roughly half of the increase in total sleep time was attributable to longer N3 sleep (patients on pimavanserin had, on average, 20 more minutes of N3 versus placebo, P = ns). This translated into a more stable sleep time on pimavanserin (mean increase, 41.4 ± 78.9 min) (Table 3). However, patients did not report improved subjective sleep quality on pimavanserin; rather, it was decreased (per next-morning Visual Analog Scale assessment). The reason for the discrepancy between prolonged sleep time and worsened subjective sleep quality is unclear.

As mentioned above, the characteristics of pimavanserin make it suitable also for combination with atomoxetine. Despite the absence of an effect on arousal threshold, pimavanserin still showed greater sedative properties than oxybutynin, which alone did not improve total sleep time (13). Pimavanserin may preserve sleep stability, whereas atomoxetine simultaneously increases pharyngeal muscle activity. In addition, if administered for a longer time, pimavanserin might also be able to systematically increase the arousal threshold and promote further upper airway muscle recruitment without a decrement in collapsibility, a drawback of common hypnotics (9). Testing the effect of atomoxetine plus pimavanserin on OSA severity is certainly warranted, especially over a longer administration time, although caution is recommended, as both drugs can potentially lengthen QTc.

Pimavanserin did not cause any side effects or complaints. This suggests that a single dose of pimavanserin is safe for acute administration in patients with OSA.

Methodological Considerations

This study has several limitations. First, the number of studied subjects was somewhat small. However, we highlight that these physiological studies are exploratory in nature; if an effect is observed, then larger studies that require more resources can be designed later. Second, as outlined throughout the discussion, the effect of pimavanserin on primary and secondary outcomes could be (partly) masked by the single night administration of pimavanserin. A study assessing the effect of a prolonged administration of pimavanserin alone and in combination with atomoxetine on OSA severity is needed. Third, we did not record EMG genioglossus activity, so the actual effect of pimavanserin on pharyngeal muscle responsiveness (another important OSA endotype) was not assessed. Fourth, subjective sleep quality was recorded only through one questionnaire and not corroborated by other measures of sleepiness and alertness (e.g., Karolinska Sleepiness Scale); therefore, the worsened subjective sleep quality after pimavanserin treatment remains challenging to interpret.

Conclusions

Administration of a single dose of pimavanserin did not have an effect on respiratory arousal threshold or OSA severity. However, in the seven individuals who exhibited a higher arousal threshold on the treatment night, pimavanserin slightly decreased AHI4, supine AHI, and hypoxic burden. This suggests that if the arousal threshold can be increased with this medication, possibly through a longer dosing schedule, pimavanserin might be a good candidate for OSA treatment, especially if combined with other drugs that activate pharyngeal muscles.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (P01 149630).

Author Contributions: Study design: L.M. and A.W. Data collection: L.M., L.G., and N.C. Data analysis: L.M. Interpretation of results: all authors. Initial draft: L.M. Review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. All authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

Data availability: All the individual participant and summary data collected during the trial will be shared on request after deidentification. In addition, the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, and informed consent will be made available. Data will be available immediately after publication.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Phillipson EA, Sullivan CE. Arousal: the forgotten response to respiratory stimuli. Am Rev Respir Dis . 1978;118:807–809. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.118.5.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Younes M. Role of arousals in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2004;169:623–633. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200307-1023OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wellman A, Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Edwards BA, Passaglia CL, Jackson AC, et al. A method for measuring and modeling the physiological traits causing obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). . 2011;110:1627–1637. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00972.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Edwards BA, Connolly JG, Campana LM, Sands SA, Trinder JA, White DP, et al. Acetazolamide attenuates the ventilatory response to arousal in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep (Basel) . 2013;36:281–285. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ratnavadivel R, Stadler D, Windler S, Bradley J, Paul D, McEvoy RD, et al. Upper airway function and arousability to ventilatory challenge in slow wave versus stage 2 sleep in obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax . 2010;65:107–112. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buchanan GF, Smith HR, MacAskill A, Richerson GB. 5-HT2A receptor activation is necessary for CO2-induced arousal. J Neurophysiol . 2015;114:233–243. doi: 10.1152/jn.00213.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith HR, Leibold NK, Rappoport DA, Ginapp CM, Purnell BS, Bode NM, et al. Dorsal raphe serotonin neurons mediate CO2-induced arousal from sleep. J Neurosci . 2018;38:1915–1925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2182-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Messineo L, Carter SG, Taranto-Montemurro L, Chiang A, Vakulin A, Adams RJ, et al. Addition of zolpidem to combination therapy with atomoxetine-oxybutynin increases sleep efficiency and the respiratory arousal threshold in obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomized trial. Respirology . 2021;26:878–886. doi: 10.1111/resp.14110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Griffin CE, III, Kaye AM, Bueno FR, Kaye AD. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system-mediated effects. Ochsner J . 2013;13:214–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, Sands SA, Azarbarzin A, Marques M, Edwards BA, et al. The combination of atomoxetine and oxybutynin greatly reduces obstructive sleep apnea severity. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;199:1267–1276. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201808-1493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan E, Steenland HW, Liu H, Horner RL. Endogenous excitatory drive modulating respiratory muscle activity across sleep-wake states. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2006;174:1264–1273. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-597OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grace KP, Hughes SW, Horner RL. Identification of the mechanism mediating genioglossus muscle suppression in REM sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2013;187:311–319. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1654OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, Azarbarzin A, Vena D, Hess LB, Calianese NA, et al. Effects of the combination of atomoxetine and oxybutynin on OSA endotypic traits. Chest . 2020;157:1626–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, Harding SM, Lloyd RM, Quan SF, et al. AASM scoring manual updates for 2017 (version 2.4) J Clin Sleep Med . 2017;13:665–666. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Azarbarzin A, Sands SA, Stone KL, Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, Terrill PI, et al. The hypoxic burden of sleep apnoea predicts cardiovascular disease-related mortality: the osteoporotic fractures in men study and the sleep heart health study. Eur Heart J . 2019;40:1149–1157. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gell LK, Vena D, Alex RM, Azarbarzin A, Calianese N, Hess LB, et al. Neural ventilatory drive decline as a predominant mechanism of obstructive sleep apnoea events. Thorax . 2022;77:707–716. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sands SA, Edwards BA, Terrill PI, Taranto-Montemurro L, Azarbarzin A, Marques M, et al. Phenotyping pharyngeal pathophysiology using polysomnography in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2018;197:1187–1197. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201707-1435OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Terrill PI, Edwards BA, Nemati S, Butler JP, Owens RL, Eckert DJ, et al. Quantifying the ventilatory control contribution to sleep apnoea using polysomnography. Eur Respir J . 2015;45:408–418. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00062914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Owens RL, Edwards BA, Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Sands SA, Malhotra A, et al. an integrative model of physiological traits can be used to predict obstructive sleep apnea and response to non positive airway pressure therapy. Sleep (Basel) . 2015;38:961–970. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edwards BA, Sands SA, Owens RL, Eckert DJ, Landry S, White DP, et al. The combination of supplemental oxygen and a hypnotic markedly improves obstructive sleep apnea in patients with a mild to moderate upper airway collapsibility. Sleep (Basel) . 2016;39:1973–1983. doi: 10.5665/sleep.6226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Edwards BA, Sands SA, Eckert DJ, White DP, Butler JP, Owens RL, et al. Acetazolamide improves loop gain but not the other physiological traits causing obstructive sleep apnoea. J Physiol . 2012;590:1199–1211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.223925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Perger E, Taranto Montemurro L, Rosa D, Vicini S, Marconi M, Zanotti L, et al. Reboxetine plus oxybutynin for OSA treatment: a 1-week, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover trial. Chest . 2022;161:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cruz MP. Pimavanserin (Nuplazid): a treatment for hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease. P&T . 2017;42:368–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Messineo L, Eckert DJ, Lim R, Chiang A, Azarbarzin A, Carter SG, et al. Zolpidem increases sleep efficiency and the respiratory arousal threshold without changing sleep apnoea severity and pharyngeal muscle activity. J Physiol . 2020;598:4681–4692. doi: 10.1113/JP280173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yunusa I, El Helou ML, Alsahali S. Pimavanserin: a novel antipsychotic with potentials to address an unmet need of older adults with dementia-related psychosis. Front Pharmacol . 2020;11:87. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mizutani T. PM frequencies of major CYPs in Asians and Caucasians. Drug Metab Rev . 2003;35:99–106. doi: 10.1081/dmr-120023681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou Y, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Lauschke VM. Worldwide distribution of cytochrome p450 alleles: a meta-analysis of population-scale sequencing projects. Clin Pharmacol Ther . 2017;102:688–700. doi: 10.1002/cpt.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Messineo L, Eckert DJ, Taranto-Montemurro L, Vena D, Azarbarzin A, Hess LB, et al. Ventilatory drive withdrawal rather than reduced genioglossus compensation as a mechanism of obstructive sleep apnea in REM sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2022;205:219–232. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202101-0237OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Veasey SC, Fenik P, Panckeri K, Pack AI, Hendricks JC. The effects of trazodone with L-tryptophan on sleep-disordered breathing in the English bulldog. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 1999;160:1659–1667. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9812007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zinchuk A, Yaggi HK. Phenotypic subtypes of OSA: a challenge and opportunity for precision medicine. Chest . 2020;157:403–420. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]