Abstract

Background

Women’s adherence is essential to physiotherapeutic treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction, but its related factors are not usually considered in the development of treatment approaches. This study aims to understand how women with pelvic floor dysfunction experience pelvic floor conservative non-pharmacological treatment options.

Methods

A systematic review of qualitative studies. The electronic search was performed in MEDLINE/PubMed, CINAHL, Lilacs, SCOPUS, and Web of Science databases. Primary articles on qualitative methods focused on the experience of women regarding pelvic floor conservative non-pharmacological interventions, i.e., pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), either associated or not with biofeedback, perineal massage, vaginal dilators, and others. A meta-aggregation was performed.

Results

It was included 22 manuscripts in this review. It was found seven studies about the use of vaginal devices, two about manual intervention and 14 studies on women’s experience with PFMT. The findings were synthesized as follows: I) women’s experience of manual interventions; II) women’s experience using vaginal devices changes according to health professional attitudes; III) women’s experiences using vaginal devices varied depending on their pelvic floor dysfunction; IV) reported side effects due to the use of vaginal devices; V) external factors influencing PFMT performance; VI) women’s perception of their own personal factors influencing PFMT performance; VII) PFMT characteristics influencing women’s adherence; VIII) strategies used by women to include PFMT in their routine.

Conclusion

Women’s experience with pelvic floor conservative non-pharmacological treatment options is a complex phenomenon that involves many more variables than simply personal aspects. This is a systematic review of qualitative studies registered in the PROSPERO (CRD42018080244).

Keywords: Physiotherapy, Pelvic floor, Women’s health, Women’s experience

Background

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) is a term used to describe any disturbance in the active (i.e., pelvic floor muscle) and/or passive (i.e., fascia and ligaments) components of the pelvic floor [1]. In the current literature, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) is known to be the gold standard treatment for PFD, specifically for urinary incontinence (UI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in women [2, 3]. Other conservative non-pharmacological treatment options for PFD include electrical nerve stimulation, perineal massage, vaginal dilators and pessaries [4, 5].

Women’s adherence is an essential component to be considered during conservative non-pharmacological treatments for PFD [6]. Adherence and its related factors are not usually considered in the development of different treatment approaches, nor as a primary outcome measure in randomized controlled trials (RCT), which is the appropriate study design to determine the effectiveness of any pelvic floor conservative non-pharmacological interventions [7–9].

A recognized limitation of RCTs is they do not allow an understanding of women’s experience with the intervention under investigation, nor aspects that may influence their adherence to treatment [9–11]. Thus, qualitative research aiming to understand the experience of women with conservative non-pharmacological treatments for PFD can fill this important gap [10]. To date, no specific systematic reviews about this important topic was found.

Thus, the aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of qualitative studies to answer the following question: how do women with PFD symptoms experience conservative non-pharmacological treatment options?

Methods

This is a systematic review of qualitative studies registered in the PROSPERO (CRD42018080244) which search was conducted in April 2020. The research was planned based on SPIDER: I) Sample—women with PFD symptoms; II) Phenomenon of Interest—conservative non-pharmacological treatment options (PFMT, vaginal dilators, biofeedback, perineal massage, pessary, and others); III) Design—qualitative research, thematic analysis, grounded theory, phenomenology; IV) Evaluation—women’s experience; V) Research type—qualitative studies.

The inclusion criterion was original qualitative research regarding women’s experience with pelvic floor non-pharmacological interventions. The exclusion criteria were: (1) not primary research; (2) quantitative or mixed methods studies; (3) studies about women’s experience with the treatment of their partners or children; (4) studies that included either only men or both men and women. Although systematic reviews, quantitative and mixed methods studies were not included in this review, their references were examined to identify any additional study that meet the inclusion criterion.

The electronic search was conducted by one researcher (ACNLF). No limit was set for year of publication. The last search was performed in April 2020. The primary research was conducted in MEDLINE/PubMed, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Lilacs and Web of Science databases, and is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Database | SPIDER | Strategy |

|---|---|---|

|

MEDLINE/PubMed CINAHL SCOPUS Web of Science |

Sample | (“pelvic floor dysfunctions” OR “lower urinary tract symptoms” OR “urinary incontinence” OR “anal incontinence” OR constipation OR “fecal incontinence” OR “pelvic organ prolapse” OR “sexual dysfunction” OR vaginismus OR dyspareunia OR “pelvic floor”) |

| Phenomenon of Interest | (physiotherap* OR “pelvic floor muscle training” OR “pelvic floor exercise” OR “Kegel exercise” OR “behavioral treatment” OR “behavioral therapy” OR “perineal massage” OR “vaginal dilators” OR “vaginal cones” OR biofeedback OR “electrical nerve stimulation” OR “electrical stimulation” OR pessaries OR “exercise therapy” OR treatment OR therap*) | |

| Design | (“qualitative research” OR “qualitative study” OR qualitative OR “thematic analysis” OR “grounded theory” OR phenomenology OR “focus group” OR “semi-structured interview”) | |

| Evaluation | – | |

| Research type | – | |

| Lilacs | Sample | (“lower urinary tract symptoms” OR incontinenc$ OR constipation OR constipação OR “pelvic organ prolapse” OR “prolapso dos órgãos pélvicos” OR “sexual dysfunction” OR "disfunção sexual" OR vaginism$ OR d?spareunia OR “pelvic floor” OR "assoalho pelvico") |

| Phenomenon of Interest | (physiotherap$ OR fisioterapia OR treinamento OR exercicio$ OR tratamento OR massagem OR dilatador$ OR cone$ OR “estimulação elétrica” OR “electrical stimulation” OR training OR exercise OR treatment$ OR massage OR dilators OR biofeedback OR pessari$) | |

| Design | – | |

| Evaluation | – | |

| Research type | qualitative |

The search result was imported to the EndNote online platform where duplicates were excluded. The remaining references were first selected according to the relevance of their title and abstract to the research question. The selection was conducted by two independent researchers (ACNLF and TBD) who carefully read the full texts. Any disagreement was solved by discussion with a third reviewer (DPC). A secondary search was conducted manually using the selected articles and the reviews and mixed-method studies found during manual searching.

One researcher (CCP) was responsible for extracting the following information: bibliographic details, population, setting, cultural information, aims of the study, specific qualitative methodology, sampling method and size, and main results. Data synthesis was conducted after data extraction and fragments of participant reports was used to support the finding of this review. A second researcher (ACNLF) checked the extracted information as well as the congruence between the findings and the text fragments used. Divergences on selected information were settled through discussion between researchers.

The quality of the selected studies was assessed based on the quality criteria for qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist. This 10-question checklist covers three broad issues, named: are the results of the study valid (Section A—questions 1 to 6)? What are the results (Section B—questions 7 to 9)? Will the results help locally (Section C—question 10)?

A meta-aggregation [12] was conducted as follows: (1) extraction of all findings (including narrative fragments and quotes); (2) developing categories; (3) developing synthesised findings. Findings and categories were grouped based on similarity of concept and no software was used.

Results

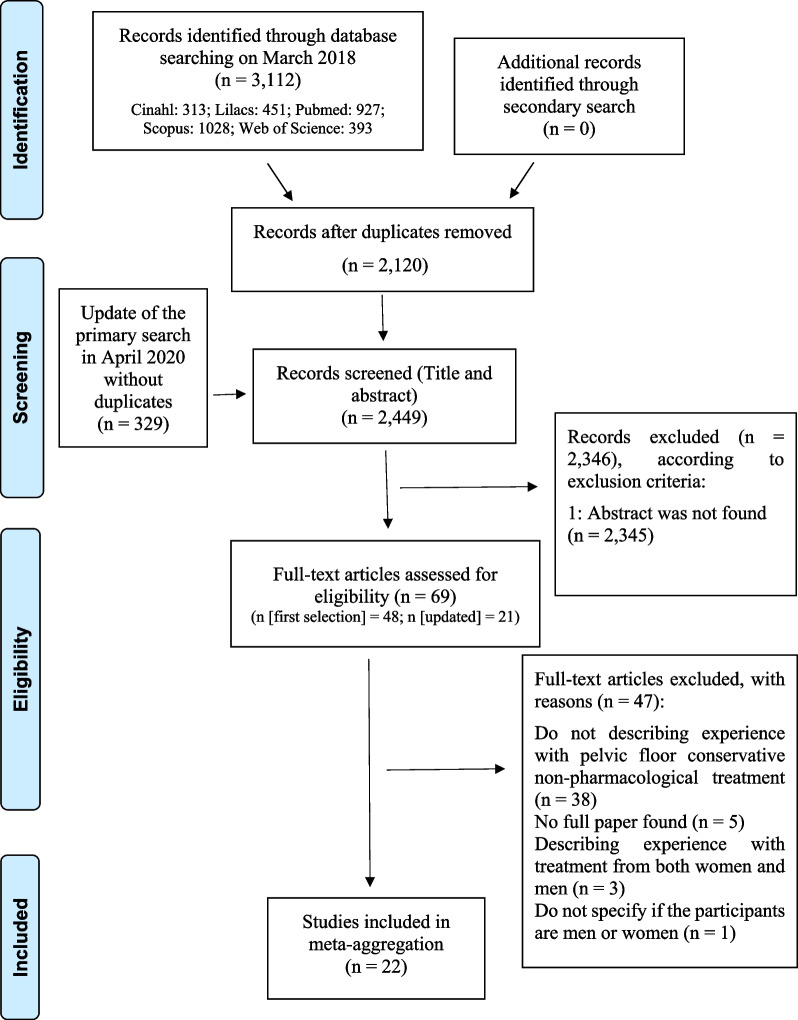

The flowchart of the study is presented in Fig. 1. It included 22 manuscripts published between 1993 and 2020, with a total of 304 participants.

Fig. 1.

Study selection flow diagram

Study characteristics

Table 4 in Appendix presents the characteristics of the included studies. The studies were conducted in different parts of the world: two (9.1%) studies were from South America [13, 14]; four (18.2%) from North America [15–18]; ten (45.4%) from Europe [19–28]; two (9.1%) from Asia [29, 30] and three (13.6%) from Oceania [31–33]. One study (4.5%) did not report where data collection was performed [34].

Table 4.

Characteristics of selected studies

| Identification | Qualitative design | Sampling strategies | Number/ participants | Intervention | Tools | Analysis | Quality criteria reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abhyankar et al. [19] | Qualitative study—symbolic interactionism | Purposive sampling | 22 women with POP receiving prolapse care | PFMT and/or pessaries | Semi-structured interviews and focus group | Thematic analysis | – |

| Ashworth et al. [34] | Phenomenological study | Unknown | 28 women with UI and aged between 25 to 55 years old | PFMT | Non-structured and structured face-to-face interview | Analysis was guided by phenomenological principles, adapting from Giorgi | – |

| Asklund et al. [20] | Qualitative study | Purposive sampling | 15 women with SUI and aged between 27 to 72 years old (mean age 47 years old) | PFMT | Semi-structured, telephone interview, guide with open-ended questions | Grounded theory | – |

| Bakker et al. [21] | Qualitative study | Purposive sampling | 30 women who treaded with brachytherapy (mean age was 49 years old, aged between 32 to 67 years old) | Vaginal dilator | Semi-structured face-to- face or by telephone interview | The transcriptions were analysed with QSR International's Nvivo 10 software using the Framework Approach | – |

| Bjork et al. 2014 | Qualitative study | Strategic selection | 21 women with SUI aged between 30 to 69 years old | PFMT | Semi-structured interview by telephone | Grounded theory | – |

| Bonner et al. [31] | Qualitative study | Purposive sampling | 15 women with an average age was 53 years old, aged between 31 to 68 years old | Vaginal dilators | Semi-structured face-to-face or by telephone interview | Thematic analysis | – |

| Cacchioni et al. [15] | Qualitative study | Unknown | 31 women were interviewed but only 18 of those interviewed were presented (average age of was 36 years old, aged between 24 to 62 years old) | Hands-on intervention | Semi-structured, in-depth interviews | All interview and fieldwork data were transcribed and manually coded by theme with names and identity-revealing information changed | – |

| Delamerlindo et al. [13] | Grounded theory study | Purposive sampling | 18 women aged between 41 to 81 years old | PFMT | Non-directive interview | Grounded theory | – |

| Delamerlindo et al. [14] | Qualitative study | Unknown | 18 women with UI aged between 41 to 81 years old | PFMT | Non-directive interview | Grounded theory | – |

| Firet et al. [27] | Qualitative study | Purposive sampling | 13 women with SUI aged between 40 to more than 80 years old | PFMT | Semi-structured, face-to-face interviews | Grounded theory and Atlas.ti software | The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| Grant et al. [23] | Qualitative exploratory study | Unknown | 31 postnatal women aged between 28 to 43 years old | PFMT | Online and face-to-face focus group | Thematic analysis | – |

| Hay-Smith et al. [32] | Unknown | Purposive sampling | 20 women with aged between 23 to 86 years old | PFMT | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Descriptive content analysis | – |

| Hyland et al. 2013 | Phenomenological study | Purposive sampling | 5 women with POP aged between 45 to 60 years old | PFMT | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | – |

| Kao et al. [29] | Qualitative descriptive study | Purposive sampling | 12 women aged between 44 to 66 years old | PFMT | Semi-structured face-to-face in-depth interviews | Thematic analysis | Lincoln and Guba's guidelines: Credibility, Dependability, Confirmability and Transferability |

| Lindgren et al. [24] | Qualitative descriptive study | Unknown | 13 women who survived gynaecological cancer, mean age of 66 years old (aged between 48 to 82 years old) | PFMT | Semi-structured interview | Content analysis | – |

| Macey et al. [25] | Qualitative study—phenomenological approach | Convenience sampling | 13 women were interviewed aged between 20 to 67 years old | Vaginal dilators | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Although the article did not present in writing the use of quality criteria, some could be identified during the reading |

| Mackenzie [26] | Phenomenological study | Phenomenological sampling | 5 women | Perineal massage | Semi-structured, in-depth interviews | Colaizzi's data analysis framework | Verbatim quotes are utilised in reports of the findings to further enhance credibility, subjects were only invited to participate if they had had no prior contact with the researcher |

| Maldonado et al. [18] | Qualitative study | Unknown | 29 Spanish-speaking women with symptoms of POP (aged between 40 to 79 years old, mean 50) | Pessaries | Semi-structured interview/in focus group | Grounded theory | – |

| Sevilla et al. [16] | Qualitative study | Unknown | 16 Spanish-speaking women with a mean age of 67.6 (aged between 47 to 85) years old | Pessary | Semi-structured interviews | Grounded theory | – |

| Siu et al. [30] | Qualitative descriptive study | Purposive sample | 35 women with SUI who aged between 39 to 74 years old with a mean age of 51.26 | PFMT | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Content analysis | The rigour in qualitative research followed the techniques suggested by Tuckett |

| Storey et al. [17] | Interpretative narrative inquiry | Purposive sampling | 11 women with UI and/or POP who were over 65 years old and retired and came from both rural and urban areas | Pessaries | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | Narrative analysis | Trustworthiness, an audit trail of researcher field notes and reflexive texts, documenting decision-making, biases and analytical choices |

| Terry et al. [28] | Ethnographic approach | Unknown | 15 pregnant women and 12 of these women postnatally | PFMT | Observations, interviews, field conversations, comprehensive field notes and semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis |

SUI Stress Urinary Incontinence; UI Urinary Incontinence; PFMT Pelvic Floor Muscle Training; US United States; POP Pelvic Organ Prolapse

From the 22 manuscripts included, 13 (59%) aimed to understand women’s experience with PFMT [13, 14, 20, 22–24, 27–30, 32–34], three (13.6%) with vaginal dilators [21, 25, 31], three (13.6%) with pessaries [16–18] and one (4.5%) with perineal massage [26]. One (4.5%) study aimed to understand women’s experience using hands-on physiotherapeutic interventions treating sexual dysfunction [15], and another one (4.5%) investigated women’s experience with pessaries and PFMT use [19].

Synthesis of the results

The synthesis of qualitative results is presented as follows: I) women’s experience of manual interventions; II) women’s experience using vaginal devices changes according to health professional attitudes; III) women’s experiences using vaginal devices varied depending on their pelvic floor dysfunction; IV) reported side effects due to the use of vaginal devices; V) external factors influencing PFMT performance; VI) women’s perception of their own personal factors influencing PFMT performance; VII) PFMT characteristics influencing women’s adherence; VIII) strategies used by women to include PFMT in their routine. Narrative fragments of the findings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Synthesised findings and narrative fragments regarding women’s experience with vaginal devices, manual interventions and PFMT

| Treatment category | Synthesised findings | Narrative fragments |

|---|---|---|

| Manual interventions | Women’s experience of manual interventions |

Q.1: “Um, obviously it did feel as though someone was right inside so, when they were pushing down on it, obviously, it hurt. But, after, like, I think it was her thumb or her finger that had been there for ages, it would release off and then you couldn’t feel anything.” [26] Q.2: “…It feels loads better now. I’ve only been, like, three, about three or four times, but it just feels loads different already.” [26] Q.3: “It was helpful because it was very educational how much your muscles will tense up as a result of painful sex or actual pain […] You could see the activity of the muscles, [what] the tone of your muscles was, so if they were tight, you could see that on the screen and then see when you’re relaxing them […] you see it happening and so as a result you’re in better control of it.” [15] |

| Vaginal devices | Women’s experience using vaginal devices changes according to health professionals’ attitudes |

Q.4: “Here they’ve given me information. How to put it on, how to take it off, and everything. I felt better.” [16] Q.5: "They sent me to see this lady to fit some sort of contraption, and she brought out this dice which was about two inches square…block on a string, and she spent 15 min writhing and tugging and trying to get it there, gave up and said, do it yourself. So I had a go, and I said, there’s no way that is going to fit in there. Well, she said, you’ve had two babies. I said, yes, I have, I said, but your bones soften and everything’s different, your physiology’s different when you’re having babies. I said, that’s not going to go in there, and if it does go in there, it ain’t going to come out, so I'm not using it.” [19] Q.6: “You lie down in a specific position that makes you feel quite vulnerable, and there is a doctor standing at the opposite end of you and she is trying to stick her finger in you [both laugh]. And then it doesn't go in and she is saying 'Relax. Relax. Relax.'” [25] |

| Women reported varied experiences using vaginal devices depending on their pelvic floor dysfunction |

Q.7: “I just looked at it as a furthering of the treatment basically.” [31] Q.8: “The idea repulsed me a little. Well maybe because, just after that operation and brachytherapy and such, the medical world frequently inserted all kinds of objects [vaginally], and that made you feel like: not now.” [21] Q.9: “I did feel a little scared of having this [pessary] inside of me…I thought I was going to feel more uncomfortable than I was already feeling. But no, I eventually got accustomed to it.” [16] Q.10: “What do I like about my pessary? Well, it gives me more confidence that I can go out and be active. You know, it’s bad always trying to be close to a washroom wherever I go. I’m very comfortable using it, it gives me some security that I can go out and enjoy myself, either to a party, or to our lunches or play darts or whatever.” [17] |

|

| Side effects while using vaginal devices |

Q.11: “But it was also kind of scary [referring to blood loss during dilator use] (…)”[21] Q.12: “The only thing that I’d change is that I had some bleeding when I first used the dilator. It would have been nice if someone had warned me about this.” [31] Q.13: “Well, I perform... Yes, it’s weird, but I perform dilator use while listening to music from Wagner. Because it is a music piece that lasts exactly 10 min.” [21] Q.14: “Those things [referring to dilators] aren’t enjoyable sex toys. [...] Then I think: then you also have to pay for them as well. [...] I also let them know that I found that very disturbing” [21] |

|

| PFMT | External factors influencing PFMT performance |

Q.15: “My family encourages me to do pelvic floor muscle exercise. Sometimes while I am sitting and watching television, my daughter will remind me to do it. She says, “You should work harder, otherwise it will not be so good”. They are very supportive.” [30] Q.16: “You showed me exactly what to do, and went through it, and made it easier- I thought well I’m not so [uncoordinated] as I thought.” [32] Q.17: “I was given a leaflet, ehm nobody really demonstrated or kind of showed you how to do the pelvic floor exercises." [23] |

| Women´s perception of their own personal factors influencing PFMT performance |

Q.18: “I think being in control it just sort of contributes to your well-being.” [33] Q.19: “Pelvic floor muscle exercises are pretty tough. […] It’s easy to pick the wrong muscles although you might be thinking you’re doing well. It would be nice to have an expert to check it; in the computer cannot do that.” [27] Q.20: "For me because I don’t have a lot of confidence in my own abilities I would probably want somebody else to check.” [28] Q.21: "I quite enjoy being quite competitive with myself and trying to achieve wee goals and being on my own with exercise." (about an app) [23] Q.22: “In the beginning, when you asked me to contract there (vaginal muscle), I associated with that thing (sex). When I twitched and contracted there (the vagina) I felt embarrassed.” [29] Q.23: “It’s a bit tough, I think, difficult. I don’t know if I’m doing it right.” [24] Q.24: “I never tried to squeeze underneath (the vagina) before. I remember when you taught me to contract there (vagina), my first thought was: Could they be contracted? I didn’t even know where they were. I couldn’t feel them, because they could not be touched and also, you are not touching them.” [29] Q.25: "No, it’s more that I’ve tested it out and feel that I’m becoming successively stronger and stronger, so I have gotten that confirmation, that this was something important. Of course, the support in the instructions, what I would experience, that I would feel it dropping, feel it relaxing, and that’s exactly what I felt." [20] |

|

| PFMT characteristics influence women’s adherence | Q.26: “It [PFMT] was different, because it wasn’t what you would call real exercise, I know that’s silly, ‘cause it was, just a different area, and not everybody can see you doing it. The silent, private exercise.” [32] | |

| Strategies used by women to include PFMT in their routine |

Q.27: “Yeah yeah so the last thing I’ve been thinking about (laughter) is my pelvic floor exercises.” [33] Q.28: “I have a habit of touching my ear lobe each morning to remind myself of the things that I have to do… each day when I touch my earlobe, I will remember to do the exercise. I absolutely will keep on with it.” [30] |

PFMT pelvic floor muscle training; Q quotes

Synthesised findings I: Women’s experience of manual interventions

Women undergoing physiotherapeutic treatment involving perineal massage to treat painful sexual complaints reported its deep impact on a physical, emotional and social level [15, 26]. They reported health professionals' attention as careful, and they felt that their complaints were taken seriously. The treatment makes them have a better perception of their body sensations, as well as the feeling of great relief while muscle spasms decreased (Table 2—Q.1, Q.3). All women reported feeling “better and better” after treatment.

Synthesised findings II: Women’s experience using vaginal devices changes according to health professional attitudes

The studies presented the experience of women who had undergone pelvic radiotherapy [21, 31], as well as women diagnosed with vaginismus [25], POP or UI [16–19]. Although there are differences in the studied sample, a common point needs to be highlighted: the communication between health professional and patient. The communication aspect of the treatment seems to have a negative influence on women’s experience using vaginal dilators, while it has a more positive impact during the use of pessaries (Table 2—Q.4).

Women seems to become insecure using vaginal dilators [21, 25, 31] due to conflicting information offered by health professionals with different levels of communication skills, however, some women described that health professional support was essential to providing a good experience during treatment [16–19]. Poor interaction between health professionals and patients was reported as a reason for discontinuation of treatment (Table 2—Q.5).

Synthesised findings III: Women’s experiences using vaginal devices varied depending on their pelvic floor dysfunction

For some women, using vaginal devices was simply an aspect of their treatment to reduce discomfort with their symptoms (Table 2—Q.7), while others perceived the use of a vaginal dilator as a constant confrontation of the reality of cancer (Table 2—Q.8). Only those using pessaries reported having an active role in the process of choosing or not choosing this treatment option. Reasoning for not choosing this treatment was based on other women’s experiences.

Despite some women with vaginismus reported a positive experience, most of them described it as “painful”, “humiliating” and even “traumatic”. The smallest vaginal dilator was considered too big, leading women to seek alternatives (e.g., vibrators and tampons). The transition between devices was difficult due to the jump in size. They stated that their journey would be easier if they cold count with partner, professional and peer support. In contrast, women using pessaries reported needing some time to learn how to use pessaries in an effective way, and once they learned how to manage it they perceived the treatment as a life-changing experience, using words such as “freedom”, “security” and “satisfaction” (Table 2—Q.9, Q.10).

Synthesised findings IV: Reported side effects due to the use of vaginal devices

Only studies on vaginal dilators presented reports of side effects, including blood loss, pain and vaginal discharge (Table 2—Q.11, Q.12). These negative experiences seem to result in anxiety, but also as a motivation to continue using dilators. Reported strategies to reduce negative feelings were increasing positivity and integrating the treatment into daily life, such as during a bath (Table 2—Q.13). The sexuality involved in the use of the vaginal dilator was a controversial experience (Table 2—Q.14).

Synthesised findings V: External factors influencing PFMT performance

The extrinsic factors appearing to influence PFMT performance are health care professional and family support (Table 2—Q.15). Health professionals were considered possible facilitators or barriers to PFMT performance (Table 2—Q.16). For some women their complaints were not properly accept by some health professionals, and they felt the need for further instructions to be able to perform PFMT. These women complained that when they received the information it was not in an appropriate manner (Table 2—Q.17). However, when the information and support were given properly, it helped them in adhering to PFMT.

Synthesised findings VI: Women’s perception of their own personal factors influencing PFMT performance

This theme has three subthemes:

Category I: Positive personal factors. A positive experience for women undergoing PFMT was reported as the feeling of control over their body (Table 2—Q.18). To avoid incorrect training, the ability to perceive and confirm their capacity to contract their PFM was considered important by women, in order to improve their commitment and confidence in their own ability to perform PFMT (Table 2—Q.19, Q.20) and to diminish their symptoms. A participant mentioned putting her own competitiveness in playing mobile apps games as a positive factor to perform PFMT (Table 2—Q.21).

Category II: Negative personal factors. Women mentioned the following negative factors: lack of motivation; previous negative experience with PFMT; uncertainties about the results or lack of good results; limited understanding about how PFMT works; embarrassments or conflicting feelings about erotization (Table 2—Q.22); difficulties in PFMT performance, including the “invisibility” of the muscle; uncertainty whether or not they were correctly contracting their PFM (Table 2—Q.23); emotional, mood and climactic factors; guilty for not performing PFMT; worsening of the symptoms; loneliness while performing PFMT; perception that PFMT is boring or a waste of time; and the naturalisation of PFD symptoms.

Category III: Perineal perception. While some women reported an inability to perceive a correct PFM contraction, some highlighted that they could progressively perceive it and notice whether or not they were performing it correctly (Table 2—Q.24, Q.25).

Synthesised findings VII: PFMT characteristics influence women’s adherence

Some women considered they have a better adherence to PFMT performed in groups, while others classified PFMT as a quiet, “private exercise” (Table 2—Q.26). While for some women PFMT could be done at any time of day without anyone else knowing, others emphasized their need to have a quiet place to focus on it. A positive point highlighted was the association of PFMT with other benefits, such as improving their self-confidence. The commitment involved in becoming a participant in clinical studies was perceived as one’s own obligation to adhere to treatment. It is worth noting that PFMT was not seen as a “real exercise” by some participants (Table 2—Q.26). This deconstruction of PFMT as physical exercise was justified by the anatomical region of the PFM, and by the possibility of performing contractions during penetrative vaginal sex.

Synthesised findings VIII: Strategies used by women to include PFMT in their routine

Some participants justified their lack of adherence to PFMT due to the lack of time to perform it. Other participants were able to include PFMT in their routine by associating it with daily life activities, such as performing the exercise while waiting for the bus or doing it every time they sit in their computer chair, among other situations (Table 2—Q.28).

Quality criteria assessment

Table 4 shows that only four studies reported the use of any form of quality criterion and only one manuscript reported the use of the Consolidate Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).

Table 3 presents the studies’ results of quality criteria analysis. Only six (26.1%) articles received the maximum score of section A, and 21 (91.3%) articles were considered to have clear (section B) or relevant results (section C). The quality of most included manuscripts was limited in aspects of methodology. There was a high number of manuscripts that did not present clear information about the recruitment strategies, nor regarding the relationship between the researchers and the participants.

Table 3.

Quality criteria

| Author | Clear statement of the aims of research | Appropriateness of qualitative design | Research design consistent to address the aims of research | Recruitment strategies appropriate to the aims | Data collection strategy appropriate | Relationship considered between research and participants | Ethical issues considered | Data analysis rigorous | Clear statement of the results | How valuable is the research? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashworth et al. [34] | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | – | |

| Bakker et al. [21] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Bjork et al. [22] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Bonner et al. [31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Cacchioni et al. [15] | X | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ | – | |

| Delarmelindo et al. [13] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Delarmelindo et al. [14] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Firet et al. [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Hay-Smith et al. [32] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Hayland et al. [33] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kao et al. [29] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Lindgren et al. [24] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Macey et al. [25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Mackenzie [26] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sevilla et al. [16] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Siu et al. [30] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Storey et al. [17] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Firet et al. [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Maldonado et al. [18] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Asklund et al. [20] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Grant et al. [23] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Abhyankar et al. [19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Terry et al. [28] | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Symbols indicate: X = No; – = Can't tell; ✓ = yes

Discussion

This study aimed to understand how women with PFD experienced pelvic floor conservative non-pharmacological treatment options. We included studies reporting women’s experience with different conservative non-pharmacological options to treat PFD.

The experience of women with PFMT seems to be related to several personal factors. The understanding by physiotherapists of factors modulating the quality of women’s experiences with this intervention seems to be essential to improve it. Although the large amount of scientific evidence showing PFMT as a treatment for some PFD symptoms is well-established in the literature, adherence remains the most challenging aspect of this treatment [2, 3, 9, 35]. PFMT adherence is a complex phenomenon that involves the active participation of patients. This study reinforces the need of women to receive further appropriate information to modify their behaviour, incorporating PFMT practice in their routine [9, 35]. This perception is aligned with the results of studies showing women’s general lack of knowledge related to PFM function, dysfunction and options of treatment, including PFMT [36]. Women with different background can acquire basic knowledge about PFMT after receiving information about the pelvic floor location/anatomy and PFM function [37]. Other studies have indicated that when women receive information about the pelvic floor they have a higher chance of adherence to PFD conservative interventions [6, 8]. Still, many women consider they don’t receive information based on their specific background and needs.

Another important aspect to be considered is women’s belief in their ability to perform PFMT, commonly known as self-efficacy. This belief is the core of social cognitive theory, one of the many theories and methods described in the literature that can be used as a guide while working with health behaviour [6]. The use of a more patient-centred approach may improve not only self-efficacy but other personal factors as technical abilities that deeply influence women’s experience with PFMT. Additionally, women referred to their ability to perceive or not perceive their PFM contraction, respectively, as a facilitator or barrier to PFMT. Self-perception as a modifier of PFMT adherence is an aspect which could be considered and worked on, as one study shows that women’s estimation of their PFM contraction intensity is poor, especially in women with a non-contracting or a weak PFM [38]. An increase in women’s perception of their PFM contraction seems to be another positive result of PFMT that could be further explored using a self-efficacy approach.

Similarly, to the strategies suggested to improve PFMT adherence, health behavioural theories have been used to identify and fill knowledge gaps related to continence promotion [39, 40]. The study conducted by Chiarelli and Cockburn [39] identified, through focus groups, gaps related to women’s knowledge after delivery and, using Health Belief Model as a theoretical guide, proposed an education program aiming to promote urinary continence (UI). To verify the program’s effectiveness, a RCT was conducted and concluded that the intervention group showed reduced prevalence of UI with adequate levels of PFMT adherence, compared to the standard care procedure group three months after childbirth [40]. It is important to highlight that these are the few studies in women’s health physiotherapy which used this approach and no studies were found specifically for the use of vaginal devices. Unfortunately, there is a small number of studies using this approach to improve women’s adherence to other interventions such as vaginal dilators.

This systematic review found reports of some negative experiences of women using vaginal dilators. However, women’s reports of intentionally associating the use of vaginal dilators with pleasant situations was identified as an important coping strategy that improved their experience.

The experiences reported after the use of pessaries were varied, but they underline the importance of women’s participation in the process of choosing the intervention, and the essential role of the health professional in either continuity or interruption of the treatment. In the only two studies investigating pelvic floor manual interventions, women stated having had a good experience while using it, especially due to the support given by the health professional.

We must state the limitation of this systematic review reflects the limitation of the included studies. Most of the included studies had methodological shortcomes and none of those articles were excluded from the review. Nevertheless, this review brings together the experiences of women with a variety of conservative interventions, highlighting important aspects that may contribute to better healthcare assistance related to PFD and to improve both treatment adherence and satisfaction.

The results showed relevant aspects that should be considered during treatment approach (e.g., adequate communication, adequate provision of information, and appropriate support from health professionals), to particularly improve women’s experience and adherence to the interventions.

This review also uncovered the need for more qualitative studies with a strong methodology to better understand women’s experience with pelvic floor conservative non-pharmacological interventions, especially those regarding manual interventions and vaginal devices.

Conclusion

Women’s experience with pelvic floor conservative non-pharmacological treatment options is a complex phenomenon that involves many more variables than just personal aspects. A more patient-centred approach should be considered to improve women’s experience with and adherence to conservative options.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Abbreviations

- PFMT

Pelvic floor muscle training

- PFD

Pelvic floor dysfunction

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- UI

Urinary incontinence

- POP

Pelvic organ prolapse

Appendix

See Table 4.

Author contributions

ACNLF: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management, Data analysis; DPC: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management, Data analysis CCP: Data collection or management, Data analysis; TBD: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management; AMPO: Data analysis; CHJF: Protocol/project development, Data collection or management, Data analysis. All authors wrote, edited, commented on, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors ACNLF, CCP and AMPO received scholarship from Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, et al. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the pelvic floor clinical assessment group of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24(4):374–380. doi: 10.1002/nau.20144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cacciari LP, Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith EJ. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women: a Cochrane systematic review abridged republication. Braz J Phys Ther. 2019;23:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C, Gong Y, Wang B. The efficacy of pelvic floor muscle training for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(7):981–992. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2846-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Abbadey M, Liossi C, Curran N, Schoth DE, Graham CA. Treatment of female sexual pain disorders: a systematic review. J Sex Marital Ther. 2016;42(2):99–142. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2015.1053023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Albuquerque Coelho SC, de Castro EB, Juliato CRT. Female pelvic organ prolapse using pessaries: systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(12):1797–1803. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-2991-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClurg D, Frawley H, Dean S, et al. Scoping review of adherence promotion theories in pelvic floor muscle training—2011 ICS state-of-the-science seminar research paper I of IV. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(7):606–614. doi: 10.1002/nau.22769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bø K, Herbert RD. When and how should new therapies become routine clinical practice? Physiother. 2009;95(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J, Frawley H, et al. 2014 consensus statement on improving pelvic floor muscle training adherence: International Continence Society 2011 State-of-the-Science Seminar. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(7):600–605. doi: 10.1002/nau.22796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumoulin C, Alewijnse D, Bo K, et al. Pelvic-floor-muscle training adherence: tools, measurements and strategies-2011 ICS state-of-the-science seminar research paper II of IV. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(7):615–621. doi: 10.1002/nau.22794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay-Smith J, Dean S, Burgio K, McClurg D, Frawley H, Dumoulin C. Pelvic-floor-muscle-training adherence “modifiers”: a review of primary qualitative studies—2011 ICS State-of-the-Science Seminar research paper III of IV. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(7):622–631. doi: 10.1002/nau.22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 1: Introduction. Eur J Gen Pract 2017;23(1): 271–273. 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179–187. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delarmelindo RDCA, Parada CMGDL, Rodrigues RAP, Bocchi SCM. Women's strategies for coping with urinary incontinence. Rev. esc. enferm. USP. 2013;47(2):296–303. 10.1590/S0080-62342013000200004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Delarmelindo RDCA, Parada CMGDL, Rodrigues RAP, Bocchi SCM. M. Between suffering and hope: rehabilitation from urinary incontinence as an intervening component. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2013;18:1981–1991. 10.1590/S1413-81232013000700013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Cacchioni T, Wolkowitz C. Treating women’s sexual difficulties: the body work of sexual therapy. Sociol Health Illn. 2011;33(2):266–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sevilla C, Wieslander CK, Alas A, et al. The pessary process: Spanish-speaking Latinas’ experience. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(6):939–946. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1946-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storey S, Aston M, Price S, Irving L, Hemmens E. Women’s experiences with vaginal pessary use. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(11):2350–2357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maldonado PA, Jackson E, Petty KM, Rondeau N, Montoya TI, Mallett VT. Qualitative analysis of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about pessary use among Spanish-speaking women on the US-Mexico Border. Female Pelvic Medic Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(1):e96–e100. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abhyankar P, Uny I, Semple K, et al. Women’s experiences of receiving care for pelvic organ prolapse: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0741-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asklund I, Samuelsson E, Hamberg K, Umefjord G, Sjöström M. User experience of an app-based treatment for stress urinary incontinence: qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e11296. doi: 10.2196/11296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakker RM, Vermeer WM, Creutzberg CL, Mens JWM, Nout RA, ter Kuile MM. Qualitative accounts of patients' determinants of vaginal dilator use after pelvic radiotherapy. J Sex Med. 2015;12(3):764–773. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Björk AB, Sjöström M, Johansson EE, Samuelsson E, Umefjord G. Women’s experiences of internet-based or postal treatment for stress urinary incontinence. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(4):484–493. doi: 10.1177/1049732314524486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant A, Currie S. Qualitative exploration of the acceptability of a postnatal pelvic floor muscle training intervention to prevent urinary incontinence. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0878-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindgren A, Dunberger G, Enblom A. Experiences of incontinence and pelvic floor muscle training after gynaecologic cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(1):157–166. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3394-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macey K, Gregory A, Nunns D, das Nair R. Women’s experiences of using vaginal trainers (dilators) to treat vaginal penetration difficulties diagnosed as vaginismus: a qualitative interview study. BMC women's health. 2015;15(1):49. 10.1186/s12905-015-0201-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Mackenzie N. A phenomenological study of women who presented to a physiotherapy-led continence service with dyspareunia and were treated with trigger point massage. J Assoc Chart Physiother Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;105:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Firet L, Teunissen D, Verhoeks C, Lagro-Janssen A. Expectations regarding eHealth among women with stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(11):1955–1963. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3849-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terry R, Jarvie R, Hay-Smith J, et al. “Are you doing your pelvic floor?” An ethnographic exploration of the interaction between women and midwives about pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFME) during pregnancy. Midwifery. 2020;83:102647. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao HT, Hayter M, Hinchliff S, Tsai CH, Hsu MT. Experience of pelvic floor muscle exercises among women in Taiwan: a qualitative study of improvement in urinary incontinence and sexuality. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(13–14):1985–1994. 10.1111/jocn.12783 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Siu LSK, Lopez V. Chinese women's experiences of stress incontinence: a descriptive qualitative study. Int J Urol Nurs. 2012;6(3):125–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-771X.2012.01155.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonner C, Nattress K, Anderson C, et al. Chore or priority? Barriers and facilitators affecting dilator use after pelvic radiotherapy for gynaecological cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(10):2305–2313. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1337-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hay-Smith EJC, Ryan K, Dean S. The silent, private exercise: experiences of pelvic floor muscle training in a sample of women with stress urinary incontinence. Physiotherapy. 2007;93(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2006.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyland G, Hay-Smith J, Treharne G. Women’s experiences of doing long-term pelvic floor muscle exercises for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse symptoms. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(2):265–271. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2202-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashworth PD, Hagan MT. Some social consequences of non-compliance with pelvic floor exercises. Physiotherapy. 1993;79(7):465–471. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9406(10)60223-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacomori C, Berghmans B, de Bie R, Mesters I, Cardoso FL. Predictors for adherence to a home-based pelvic floor muscle exercise program for treating female urinary incontinence in Brazil. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;36(1):186–195. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1482583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fante JF, Silva TD, Mateus-Vasconcelos ECL, Ferreira CHJ, Brito LGO. Do women have adequate knowledge about pelvic floor dysfunctions? A systematic review. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2019;41(8):508–519. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1695002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Andrade RL, Bø K, Antonio FI, Driusso P, Mateus-Vasconcelos ECL, Ramos S, Julio MP, Ferreira CHJ. An education program about pelvic floor muscles improved women's knowledge but not pelvic floor muscle function, urinary incontinence or sexual function: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2018;64(2):91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uechi N, Fernandes AC, Bø K, de Freitas LM, de la Ossa AM, Bueno SM, Ferreira CH. Do women have an accurate perception of their pelvic floor muscle contraction? A cross-sectional study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(1):361–366. doi: 10.1002/nau.24214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiarelli P, Cockburn J. The development of a physiotherapy continence promotion program using a customer focus. Aust J Physiother. 1999;45(2):111–119. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiarelli P, Cockburn J. Promoting urinary continence in women after delivery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;324(7348):1241. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7348.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.