Abstract

Wastewater is often discharged to natural water bodies through an open channel as well as used by marginal farmers to irrigate the agricultural fields, particularly in sub-urban areas of developing countries. In the present study, the samples of irrigation water, soil, vegetables (i.e., palak; Beta vulgaris L. var All green H1, radish; Raphanus sativus L., garlic; Allium sativum L., cabbage; Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata, brinjal; Solanum melongena L.) and crops (i.e., paddy; Oryza sativa L. and wheat; Triticum aestivum L.) were collected from the agricultural areas receiving untreated wastewater from a carpet industrial and residential areas since a decade. The contents of Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, and Zn in the filtrates of water, soil, and crops were determined using an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer AAnalyst 800, USA). Daily intake, hazardous quotient and heavy metal pollution index were computed to assess the health risk associated with consumption of heavy metal contaminated crops. The mean concentrations of Cd and Zn in B. vulgaris (5.35 µg g−1 dw and 58.41 µg g−1 dw, respectively) and Cr, Cu, and Ni in grains of T. aestivum (16.02 µg g−1 dw, 27.97 µg g−1 dw and 40.74 µg g−1 dw, respectively) were found highest and had exceeded the Indian safety limit. Daily intake of Cu, Ni, and Cr via consumption of tested cereal crops was found higher than the vegetables. The health quotient revealed that health of local residents is more linked to vegetables than cereal crops. The present findings may be helpful to the policymakers and regulatory authorities to modify the existing policy of wastewater uses in the agriculture and disposal to the natural water bodies. The regular monitoring of heavy metals in the wastewater should also be ensured by the regulatory authorities for their safe disposal to natural water bodies/agriculture in order to reduce the human health risk associated with the degree of heavy metal contaminated suburban food systems.

Keywords: Wastewater, Heavy metals, Suburban, Food systems, Health risk, Control measures

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Wastewater contains high concentrations of heavy metals resulting from local activities.

-

•

Wastewater use in agriculture significantly contributes heavy metals to food systems.

-

•

Heavy metal content in B. vulgaris and T. aestivum crops exceeds the safe limit.

-

•

Local residents are exposed to heavy metals via consumption of both vegetable and cereal crops.

-

•

Regulation of Cd, Ni and Cr mobility in suburban ecosystem is urgently needed.

1. Introduction

Water, a vital natural resource is an essential component of the environment for sustaining life on earth. It is investigated that 2.4 billion people in the world are unable to assess clean water, while 946 million people are left with limited alternative options due to SES (i.e., socioeconomic status) factors [63]. Population growth, urbanization, climate change, rising food demand, etc., are the significant factors that will widen the gap between the availability and demand of water worldwide.

The requirement for irrigation water rises as a result of rising the food demand, and wastewater is used to fulfill this need due to the scarcity of groundwater. Long-term wastewater irrigation of the agricultural fields causes the accumulation of heavy metals in soil and their transfer to food crops and thus rises over the safe level, resulting the area to be considered as a contaminated area. Treated and untreated wastewaters are used in agriculture to meet the rising demand for irrigation water [39], [51]. Around 11 % of the total cultivated area is irrigated by untreated wastewater globally reported by Thebo et al. [58]. Likewise, about 10 % of the global population consumes crops and vegetables irrigated with wastewater [27]. Wastewater is rich in organic matters and nutrients, therefore its use in the agriculture is recognized as one of the ways of wastewater management [15]. The occurrence of heavy metals in wastewater is low generally below the permissible limit but long-term irrigation with wastewater effluents has elevated heavy metals in soil [13], [51]. The transfer of heavy metals from soil to plants is primarily influenced by kinds of sources, seasons, loading rates, soil pH, redox potential, texture, organic matters, different types of available metal fractions and total metal concentrations, etc [74].

Heavy metals cause several health hazards in human beings (e.g., cancer, neurological damage, lower intelligence quotient, kidney damage, skeletal and bone disorder) [29]. In recent years, research on health risks associated with the consumption of food contaminated by pesticides, heavy metals, or other toxicants has been motivated due to growing food safety concerns [9]. International agencies such as World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), United States of Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) etc., have set the maximum allowable limits for the contents of heavy metals in water, crops, and soil to protect the public and environmental health resulting from the mobility of heavy metals in the environment and their bioaccumulation [54]. There is a high need to build accurate predictive models that can provide early information on the toxicity of heavy metals in growing crops in a contaminated region. The toxicity of heavy metals depends on characteristics of the growing medium, exposure types and paths, nutritional imbalance, intracellular homeostasis interruption and oxidative degradation of biological macromolecules (e.g., enzymes, DNA, lipids and proteins, etc) by free radicals generation.

The present study was carried out in a suburban area of a carpet city, Bhadohi, located in the eastern Gangetic plain of Uttar Pradesh, India. The Bhadohi region is the largest handmade carpet weaving cluster and accounts for about 85 % of Indian carpet exports. The four existing social labelling initiatives in the carpet industry (i.e. Rugmark, Kaleen, STEP and Care and Fair). Rugmark and Kaleen labels are affixed to individual carpets, while STEP and Care & Fair are company certification programmes. Number of registered small and large industrial unit is 3696 and estimated average number of daily worker employed in industries is 15810 [26]. Discharge of untreated effluents containing dyes such as cango red, trypan blue, victoria blue B, malachite green, auramine-O, direct Blue-199, navy N5RL1, etc. from carpet industries has the potential to harm aquatic ecosystem by reducing light penetration, which limits the photosynthetic activities of flora and leads to trophic imbalance [30], [55]. The metabolites of such dyes are poisonous, carcinogenic, and mutagenic in nature [69]. Due to the absence of a sewage treatment plant, raw industrial effluent and domestic effluents are directly used for irrigation of food crops. Therefore, it has become detrimental for the local peoples who rely on such foods. The mixed wastewater is discharged to Morwa River through an open channel which eventually falls into Varuna River, a minor tributary of Ganga River. The present study hypothesized that wastewater irrigation contributes heavy metals such as Cu, Zn, Cd, Cr, and Ni to soil-crop systems as well as poses a risk to human health. Therefore, the present research work was carried out with the aims of (1) characterize the extent and concentrations of heavy metals in wastewater, soils and edible crops, (2) assess the mobility of heavy metals in the soil-crop systems and their associated risk to human health via consumption of contaminated crops.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

The present study was carried out in the suburban areas of Sant Ravidas Nagar/Bhadohi (latitude 25º12′30″ N to 25º31'30" N and longitude 82º14′50″ E to 82º45′00″ E) located in the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh, India and lies in the doab of the river Ganga and Varuna. The district is known by the name ‘Carpet city’ as it is home to the largest hand-knotted carpet weaving industry hubs in South Asia. The use of different dyes in carpet industries as above mentioned, is a major source of heavy metal contamination in their effluents [21]. There are several small scales or micro-level industries also exist as cotton textile industries, wooden based furniture products, paper and paper products, rubber plastic and petro based industries, etc. Four sampling locations i.e., the agricultural area was identified in the study area along with a reference site, never irrigated with wastewater. The locations of different sampling points are shown in Fig. 1. The population of villagers who depend upon wastewater irrigated food crops is 8318.

Fig. 1.

Map of Bhadohi showing the relative positions of carpet industries and sampling sites.

2.2. Sample,collection and preparation

The samples of wastewater, soil and crops (palak; Beta vulgaris L. var. All green H1, radish; Raphanus sativus L., garlic; Allium sativum L., cabbage; Brassica oleracea L., var. capitata, brinjal; Solanum melongena L., paddy; Oryza sativa L. and wheat; Triticum aestivum L.) were collected in triplicates from the selected locations on a seasonal basis from March 2019 to Feb 2020.

The sampling bottles of 500 mL capacity were rinsed with acidic water (10 % HCl) followed by deionized water. Sampling bottles were air-dried and placed in an oven for 12 h at 40 ºC. Three acid-washed polyethylene bottles were submerged in an open drain one by one at an interval of 30 s to collect the water samples, and 1 mL of concentrated HNO3 was added to the bottle immediately to prevent the microbial utilization of heavy metals. A monolith of 10 cm × 10 cm × 15 cm size was dug out at the selected site after the removal of litter from the surface of the topsoil to collect the 100 g soil. The soils were air dried and crushed using a stainless-steel blender then sieved using a 2-mm mesh sized sieve and stored at room temperature for further analysis. Approximately 1 kg of each crop was collected in triplicates randomly from 5 m × 5 m size agricultural plot at each site. The crop samples were then kept in a pre-acid washed polybag and brought back to the laboratory. The crop samples were separated into edible and non-edible parts and then washed under running tap water to remove adhered soil and dust particles. The samples were then chopped into small pieces, wrapped in brown paper, and kept in a hot air oven at 80 ºC till a constant weight was achieved. Grains were segregated from the cereal crops and were also oven-dried at 80 ºC till constant weight. Dried crop samples were grinded using a stainless-steel blender and passed through a sieve of 2 mm-mesh sized sieve and the powder was stored at room temperature for further analysis.

2.3. Sample analysis

Soil pH was measured in the suspension of soil and water in the ratio of 1: 5 (w/v) with the help of a pH meter (Eutech Instruments, Singapore) using standards reference buffers (pH 4, 7 and 9.2). Electrical Conductivity (EC) was also measured in the same soil suspension using a conductivity meter (Labman Scientific Instruments, India) and KCl as the standard solution. The pH and electrical conductivity of water samples were also measured using the above-said methods. Total nitrogen and exchangeable bases (e.g., Na+, K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+) in soil were analyzed using Kjeldahl and ammonium acetate leaching methods, respectively [34]. The concentrations of exchangeable bases in the samples were determined using an atomic absorption Spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer AAnalyst 800, USA). Walkley and Black’s rapid titration method was used to determine the content of organic carbon and organic matters in the soil [5].

2.4. Determination of heavy metals in samples

The water sample (100 mL) was digested with 10 mL of concentrated HNO3 at 80 ºC till the solution became transparent [6]. The solution was then filtered through Whatman No. 42 filter paper and the filtrate was diluted to 25 mL using double distilled water and stored in the refrigerator at 4 °C till the determination of heavy metals. Air-dried soil (0.25 ± 0.02 g) and oven-dried plant sample (0.1 ± 0.01g) were placed into a 100 mL beaker separately and 10 mL of the di-acid mixture (70 % high purity HNO3 and 65 % HClO4 in 9:4 ratio) was added [22]. The mixture was then digested at 80 °C till the solution became transparent. The digested samples were then filtered through Whatman No. 42 filter paper and the final volume of the filtrate was maintained to 25 mL using double distilled water.

2.5. Sequential extraction of heavy metal from soil

Five fractions of heavy metals were extracted and percentage values were computed by using the method described by Sarkar et al. [49] and modified by Tessier et al. [57]. Different fractions (i.e. F1: exchangeable, F2: carbonate bound, F3: Fe–Mn oxide bound, F4: organic matter bound, and F5: residual fraction) were obtained after a series of chemical treatments with various acids and oxidizers, which resulted in loosening heavy metals in several fractions. Solution and solid phases after each extraction stage were separated by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min. The digested samples were then filtered using Whatman No. 42 filter paper, and heavy metals content were analysed using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer AAnalyst 800, USA).

2.6. Quality control and precision analysis

To evaluate data contamination and dependability, quality control measures were implemented. To calibrate the instrument, blank and drift standards (Sisco Research Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India) were run after five measurements. The coefficient of variation of replicate analysis was calculated for various determinations and for analysis reliability. Variations were reported to be below 10 %. Repeated evaluation of samples against National Institute of Standards and Technology standard reference material (SRM 1570) for all heavy metals ensured precision and accuracy of results.

2.7. Computation of health risk indices

2.7.1. Enrichment factor (EF)

The mobility of heavy metals in soil-plant systems under different irrigation regimes (ground water/wastewater) was investigated. The accumulation of heavy metals in crops produced under wastewater irrigation regime over ground water was assessed using the enrichment factor. Enrichment factor was computed using the formulae given by Buat-Menard and Chesselet [11].

Where, VW and Vg are concentrations of heavy metals in the edible part of crops irrigated with wastewater and ground water, respectively. SW and Sg are concentrations of heavy metals in wastewater and ground water irrigated soil, respectively.

2.7.2. Bio-concentration factor (BCF) and transfer factor (TF)

Bio-concentration factor is used to determine the mobility of heavy metals from soil to root of plants, whereas TF indicated the transferring capacity of heavy metals from soil to edible parts of plants [16], [24], [25].

Where, Croot and Csoil are the concentrations of heavy metal in the root of crops and the corresponding value in the soil, respectively.

Where, Ce and Cs are the concentrations of heavy metal in edible parts of the crops and corresponding value in soil, respectively.

2.7.3. Metal pollution index (MPI)

Metal pollution index estimated the levels of all the heavy metals in the samples. Metal Pollution Index is the geometric mean of the concentrations of all the heavy metals in the samples and was computed using the following equation [61].

| MPI = (C1 × C2 × C3 ×……×Cn)1/n |

Where, Cn is the concentration of n heavy metals in the sample.

2.7.4. Daily intake of metals (DIM) and hazard quotient (HQ) of edible crops

In order to estimate the potential health risk associated with the consumption of heavy metal contaminated crops produced under different irrigation regimes, daily intake of metal and hazard quotient of the tested heavy metals were calculated. For the analysis of DIM and HQ, a structured questionnaire-based study was conducted from door-to-door survey in the study area. In this survey, an appropriate number of native participants by random sampling method was selected. To calculate the quantity of edible crops consumed on monthly basis, volunteers were asked about their daily consumption of edible crops individually and as a whole for the family. The volunteers’ edible crop sources were also questioned, including whether they consumed the locally grown and sold in the markets or from neighboring areas.

Daily intake of heavy metals by the local residents of the study area via consumption of contaminated vegetables and cereal crops was determined by using the following formulae [7].

Where, M is the heavy metal concentration in vegetables/cereal crops (µg g−1), K is the conversion factor (0.085 and 1 for vegetable and cereal crops, respectively) i.e., used for conversion of fresh weight of samples to their dry weights [41]. I is the daily intake of vegetables and cereal crops by children and adult (0.232 kg/person/day and 0.345 kg/person/day, respectively), BW is the average body weights of children and adult (32.7 kg, and 55.9 kg, respectively) as reported in the literature [17], [62].

Hazard Quotient for the edible crops was computed using the following formulae [20], [60]. The reference oral dose for Cu, Zn, Cd, Ni and Cr were 0.04, 0.3, 0.001, 0.02 and 0.003 µgg−1, respectively [18], [56].

Where, EF is the exposure frequency (365 days year−1 and 45 days year−1 for cereal crops and vegetables, respectively), ED is the exposure duration (6 and 70 years for children and adult, respectively), AT is the mean exposure time for non-carcinogenic effects (ED × 365 days years−1 and ED × 45 days years−1 for cereal crops and vegetables, respectively).

2.8. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the generated data was performed using SPSS version 16.0 and results are expressed as mean and standard error of three replicates. The regression analyses were also performed to assess the correlation between the heavy metal concentrations in the soil and plants (data size i.e., n = 12).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Physico-chemical characteristics of irrigation water and soil samples

The chemical characteristics of irrigation water and soil samples collected from different sites of the study areas are given in Table 1, Table 2, respectively. The results of the present study showed that the pH of wastewater (industrial and domestic effluents) was which is slightly lower than ground water (Table 1). Lower pH of wastewater as compared to the ground water reported by Singh et al. [53]. The electrical conductivity of wastewater was found higher than the ground water. The frequent application of wastewater was probably affecting the physico-chemical properties of the soil which significantly regulate the fate of heavy metals in the soil as well as their transfer to plants [27], [50], [54]. However, the composition of wastewater and the types of soil may have both positive and negative impacts on the soil-plant systems with regard to heavy metals or nutrient transmission [36]. The long-term application of wastewater in agriculture has greatly modified the pH, electrical conductivity, and organic matter content in the soil. In the present study, pH of ground water irrigated soil i.e., 7.94 was slightly higher than wastewater irrigated soil i.e., 7.10. But electrical conductivity and organic matter content in wastewater irrigated soil (164.11µS/cm and 4.73 %, respectively) were found higher than ground water irrigated soil (108.9 µS/cm and 3.38 %, respectively) (Table 2). Decrease in pH of soil irrigated with olive mill wastewater as compared to those irrigated with ground water reported by Zema et al. [70]. Any alteration in soil pH due to long-term wastewater irrigation can significantly affect the adsorption, mobilization and bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil. The study of higher EC and organic matter content (1.51 ds/m and 46.8 g/kg, respectively) in soil due to continuous use of wastewater for irrigation as compared to ground water irrigated soil (0.194 ds/m and 41.9 g/kg, respectively) studied by Oubane et al. [39].

Table 1.

Chemical characteristics of wastewater frequently used in suburban agricultural areas of Bhadohi, India.

| Characteristics |

Study areas |

Safe limit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Wastewater irrigated sites |

|||||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | Mean (Range) | ||||

| pH | 7.92 ± 0.115 | 6.68 ± 0.118 | 7.02 ± 0.148 | 7.17 ± 0.153 | 7.24 ± 0.184 | 7.02 (6.68–7.24) |

6–8.5a | |

| EC | µs/cm | 887.45 ± 12.43 | 1478.3 ± 31.6 | 1385.6 ± 30.2 | 1311.8 ± 25.26 | 1277.0 ± 3.01 | 1363.17 (1277.0–1478.3) |

700–3000b |

| Heavy metals | ||||||||

| Cu | mg/l | 0.012 ± 0.001 | 0.039 ± 0.002 | 0.031 ± 0.002 | 0.025 ± 0.001 | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.029 (0.022–0.039) |

0.20c |

| Zn | mg/l | 0.072 ± 0.006 | 0.133 ± 0.002 | 0.118 ± 0.002 | 0.108 ± 0.001 | 0.097 ± 0.004 | 0.114 (0.097–0.133) |

2.00c |

| Cd | mg/l | nd | 10.014 ± 0.001 | 20.011 ± 0.001 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.0076 ± 0.00 | 0.01 (0.0076–0.014) |

0.010d |

| Ni | mg/l | 0.016 ± 0.005 | 0.047 ± 0.001 | 0.042 ± 0.002 | 0.037 ± 0.002 | 0.034 ± 0.001 | 0.04 (0.034–0.047) |

0.20b |

| Cr | mg/l | nd | 0.046 ± 0.004 | 0.031 ± 0.003 | 0.029 ± 0.005 | 0.022 ± 0.005 | 0.032 (0.022–0.046) |

0.10b |

Table 2.

Chemical properties of wastewater irrigated soil in suburban agricultural areas of Bhadohi, India.

| Chemical properties |

Study areas |

Safe limit |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Wastewater irrigated sites |

EUa | USEPAb | ISc | ||||||

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | Mean (Range) | ||||||

| pH | 7.94 ± 0.076 | 6.83 ± 0.032 | 7.11 ± 0.212 | 7.20 ± 0.118 | 7.32 ± 0.20 | 7.1 (6.8–7.3) | ||||

| EC | µs/cm | 108.92 ± 1.5 | 189.39 ± 1.88 | 171.73 ± 3.26 | 159.47 ± 4.28 | 135.88 ± 0.9 | 164.1 (135.9–189.4) | |||

| Org matter | % | 3.38 ± 0.136 | 4.97 ± 0.42 | 4.82 ± 0.35 | 4.65 ± 0.23 | 4.50 ± 0.26 | 4.7 (4.5–4.9) | |||

| Total P | µg g−1 | 99.29 ± 3.02 | 154.72 ± 12.05 | 140.61 ± 8.90 | 127.25 ± 6.26 | 112.26 ± 5.62 | 133.7 (112.2 – 154.7) | |||

| Total N | % | 0.113 ± 0.003 | 0.227 ± 0.007 | 0.206 ± 0.007 | 0.198 ± 0.007 | 0.167 ± 0.003 | 0.2 (0.17 – 0.23) | |||

| NH4-N | µg g−1 | 3.23 ± 0.09 | 5.31 ± 0.063 | 5.24 ± 0.018 | 4.83 ± 0.075 | 4.69 ± 0.13 | 5 (4.7–5.3) | |||

| NO3-N | µg g−1 | 11.14 ± 0.9 | 14.18 ± 0.44 | 13.93 ± 0.18 | 13.68 ± 0.10 | 12.50 ± 0.03 | 13.6(12.5 – 14.2) | |||

| Na | µg g−1 | 313.66 ± 6.5 | 957.88 ± 43.68 | 789.77 ± 33.39 | 702.66 ± 5 | 615.55 ± 3.38 | 766.5 (615.5 – 957.9) | |||

| K | µg g−1 | 309.66 ± 3.4 | 774.11 ± 23.88 | 645.44 ± 10.67 | 542.11 ± 7.31 | 487.89 ± 10 | 612.4 (487.9 – 774.1) | |||

| Ca | µg g−1 | 599.11 ± 22.1 | 1841 ± 27.40 | 1687.8 ± 33.90 | 1344.4 ± 21.1 | 1031.1 ± 31.9 | 1476 (1031.1 – 1841) | |||

| Mg | µg g−1 | 6780 ± 274.4 | 10927 ± 353.85 | 10012 ± 226.93 | 8291.1 ± 159.1 | 8072.2 ± 117.3 | 9325.6 (8072.2–10927) | |||

| Fe | µg g−1 | 26656 ± 202.4 | 37611 ± 764.1 | 33733 ± 620.33 | 32300 ± 183.5 | 31156 ± 262.6 | 33700 (31156–37611) | |||

| Heavy metals | ||||||||||

| Cu | µg g−1 | 12.06 ± 0.134 | 40.87 ± 3.98 | 38.50 ± 3.640 | 34.86 ± 3.160 | 31.63 ± 3.230 | 36.6 (31.6 – 40.8) | 100 | 140 | 135–270 |

| Zn | µg g−1 | 21.516 ± 0.44 | 73.13 ± 5.77 | 60.44 ± 5.68 | 53.64 ± 5.37 | 47.40 ± 3.82 | 58.6 (47.4 – 73.1) | 300 | NA | 300–600 |

| Cd | µg g−1 | 1.78 ± 0.19 | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 2.43 ± 0.25 | 2.097 ± 0.20 | 1.91 ± 0.19 | 1.93 (1.32 – 1.91) | 3 | 3 | 3–6 |

| Ni | µg g−1 | 12.36 ± 0.25 | 45.30 ± 4.16 | 41.45 ± 3.93 | 37.92 ± 3.14 | 35.73 ± 1.98 | 40.1 (35.7 – 45.3) | 50 | 75 | 75–100 |

| Cr | µg g−1 | 11.93 ± 0.45 | 37.82 ± 2.03 | 33.18 ± 1.31 | 28.95 ± 0.71 | 26.05 ± 0.22 | 31.5 (26.1 – 37.8) | 100 | 150 | NA |

Values are mean ± SE of three replicates

NA (Not available),

European Union Standards (European Union, 2006),

USEPA (2004),

Indian standards (Awashthi, 2000) [8]

3.2. Heavy metal content in water and soil samples

The results of heavy metal contents in irrigation water and irrigated soils of the study areas are presented in Table 1, Table 2, respectively. In the present study, the concentrations of Cu, Zn, Cd, Ni, and Cr in the wastewater (0.029 mg/L, 0.114 mg/L, 0.01 mg/L, 0.04 mg/L, and 0.032 mg/L, respectively) were found higher their concentration in the ground water (Table 1). The results further showed that the concentrations of all the heavy metals in the wastewater, except Cd were found below the safe limits of national and international standards (Table 1). The higher concentrations of heavy metals in the wastewater are ascribed to carpet industrial activities such as overuse of dyes and other chemicals for the coloring and processing of carpet materials. Higher concentrations of Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn in untreated wastewater (0.60 mg/L, 0.27 mg/L, 1.80 mg/L and 0.30 mg/L, respectively) than the tap water (0.005 mg/L, 0.02 mg/L, 0.40 mg/L and 0.12 mg/l, respectively) reported by Guadie et al. [19]. High heavy metals content in untreated wastewater debilitated the beneficial properties such as enhanced the organic matters and essential nutrients content in irrigated soil and also reduced the quality of produced crops. The results showed that heavy metals content in soil samples decreased with increasing distance from the carpet industries. The content of Cu, Zn, Cd, Ni and Cr in wastewater irrigated soil was found maximum at site S1, close to the source as 40.9 µg g−1 dw, 73.1 µg g−1 dw, 1.3 µg g−1 dw, 45.3 µg g−1 dw and 37.8 µg g−1 dw, respectively and minimum at S4, distant site were 31.6 µg g−1 dw, 47.4 µg g−1 dw, 1.9 µg g−1 dw, 35.7 µg g−1 dw and 26.1 µg g−1, respectively (Table 2). Concentrations Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn in farmland soil and wheat grain decreased with distance from the smelter industries studied by Li et al. [31].

Earlier studies showed that long-term wastewater irrigation of crops resulted from more accumulation of heavy metals in soil and consequently in crops as compared to the ground water irrigation [39], [51]. The spatial variations of all the heavy metals content in soil may be due to the variations in the extent of discharged wastewater containing heavy metals through many carpet industries effluents and domestic wastewater. Wastewater irrigated soil is characterized by significantly higher values of heavy metals than the ground water irrigated soil. In the present study, wastewater irrigated site S1 site soil had remarkably maximum concentrations of Zn, Ni, Cu, Cr, and Cd (73.1 µg g−1 dw, 45.3 µg g−1 dw, 40.8 µg g−1 dw, 37.8 µg g−1 dw and 2.4 µg g−1 dw, respectively) than the ground water irrigated soil (21.5 µg g−1 dw, 12.6 µg g−1 dw, 12.1 µg g−1 dw, 11.9 µg g−1 dw and 1.8 µg g−1 dw, respectively). An increment in the heavy metal content in the industrial effluent irrigated soil in Ethiopia than the ground water irrigated soil was reported by Gemeda et al. [18]. The results of the present study showed that Na, K, Ca, Mg and Fe content in wastewater soil were higher than those of ground water irrigated soils (Table 2). High content of Fe, Na, Ca, Mg and K in wastewater irrigated soil (1540.7 µg g−1 dw, 259.1 µg g−1 dw, 1387 µg g−1 dw, 703.1 µg g−1 dw and 598.2 µg g−1 dw, respectively) than ground water irrigated soil (1340.2 µg g−1 dw, 68.2 µg g−1 dw, 530.2 µg g−1 dw, 396.8 µg g−1 dw and 324.9 µg g−1, respectively) reported by Mahmood et al. [32]. The results further showed that the concentrations of all the heavy metals in soils were within the nationally and internationally defined standards [54]. The results of the present study indicated that major heavy metal accumulation in soil was associated with the discharge of untreated carpet industrial effluents and domestic wastewater.

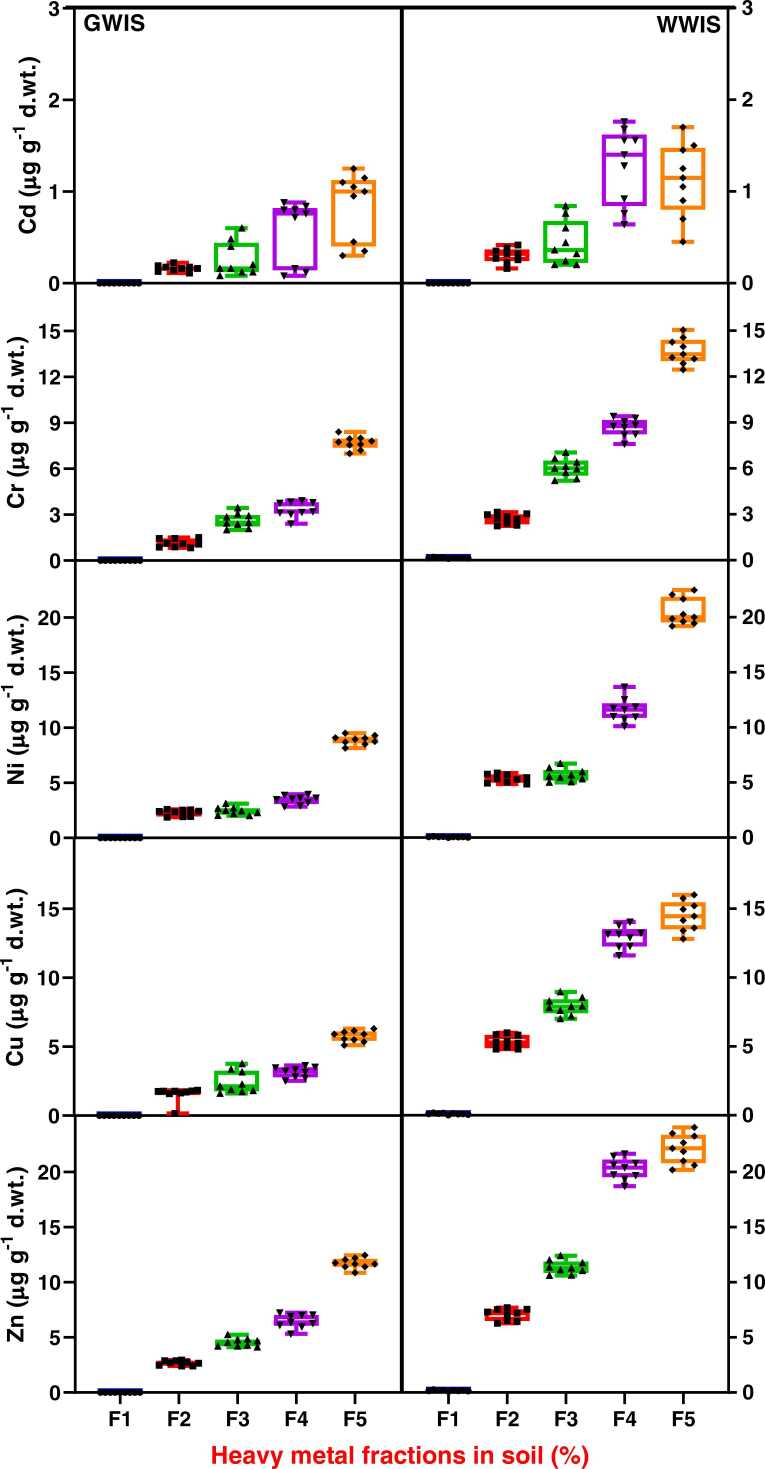

3.3. Risk of heavy metals contaminated soil

Total heavy metal concentrations in soil can indicate the degree of soil pollution, whereas different fractions of heavy metal can provide the environmental risk of heavy metals in the soil [73]. The relative distribution of different fractions of heavy metals in soil is shown in Fig. 2. In the present study, the concentration and percentage of bioavailable fractions of Cd, Cr, Ni, Cu, and Zn increased significantly in the wastewater irrigated soil as compared to reference soils. This result was consistent with our hypothesis that the mobility of heavy metals in wastewater irrigated soil was more than in the reference soil. The heavy metals in wastewater irrigated soils tended to be accumulated in the soil aggregate surface which makes it more bioaccessible whereas the original heavy metals were mainly accumulated in the core fractions. Hence, a criterion that considers the bioavailability of the newly accumulated heavy metals in wastewater irrigated soil would be fundamental to the appropriate assessment of risks from those areas [64].

Fig. 2.

Box and whisker plot for different fractions of heavy metals in soils irrigated with ground water (GWIS) and wastewater (WWIS) in the vicinity of carpet industrial areas of Bhadohi, Uttar Pradesh, India. F1, F2, F3, F4 and F5 on x-axis are the exchangeable, carbonate bound, Fe–Mn oxide bound, organic matter bound, and residual fraction of heavy metals, respectively.

The results of the present study showed that the bioavailable or active heavy metals, as represented by the acid soluble, reducible, and oxidizable fractions in the soil decrease with distance away from the source like carpet industries. However, heavy metal content in both the vegetables and cereals decreased with an increase in distance from the source. From the results, it can be inferred that an increase in the bioavailability of heavy metals in the soil near the sources enhances the accumulation of heavy metals accumulation in grown foodstuff [66]. Non-residual fractions of all the heavy metals were higher than the residual fraction in contaminated soil and reference soil except Ni. The non-residual forms of Cd, Cr, Ni, Cu, and Zn in contaminated soil (64 %, 56 %, 53 %, 65 % and 64 %, respectively) were found tohigher than their residual fractions (36 %, 44 %, 48 %, 36 %, and 37 %, respectively). The residual fraction reflects the native heavy metal concentration in the soil. Whereas high concentration of non-residual fractions of heavy metals showed their more soluble forms [23], [45]. The exchangeable fractions of Cr, Ni, Cu, Zn, and Cd (0.51 %, 0.12 %, 0.24 %, 0.28 %, and 0 %, respectively) accounted for a low percentage of total accumulation in contaminated soil. Distribution of Cd, Cr, Ni, Cu, and Zn was found highest as an oxidizable fraction of bioavailable forms (36 %, 27 %, 26 %, 31 %, and 33 %, respectively) in contaminated soil and (27 %, 22 %, 20 %, 24 %, and 25 %, respectively) in reference soil. Residual fraction of Ni and Cu was found in contaminated (48 % and 20 %, respectively) and reference soils (52 % and 20 %, respectively). The results indicated anthropogenic inputs via wastewater irrigation have significantly increased bioavailable forms of heavy metals in contaminated soil compared to reference soil. The occurrence of a higher proportion of residual fraction in reference than contaminated soil represents its natural or geogenic origin. The residual fraction of heavy metals is entrapped within the crystal structure of minerals and thus represents the least mobility as compared to the bioavailable fraction. Several plant factors, such as plant species and their growth period account for the uptake and translocation of heavy metals from soil to plant. Root exudates of the plants which contain organic acids, amino acids, sugars, and high molecular weight compounds, increase the solubility and bioavailability of metals in the rhizosphere [47].

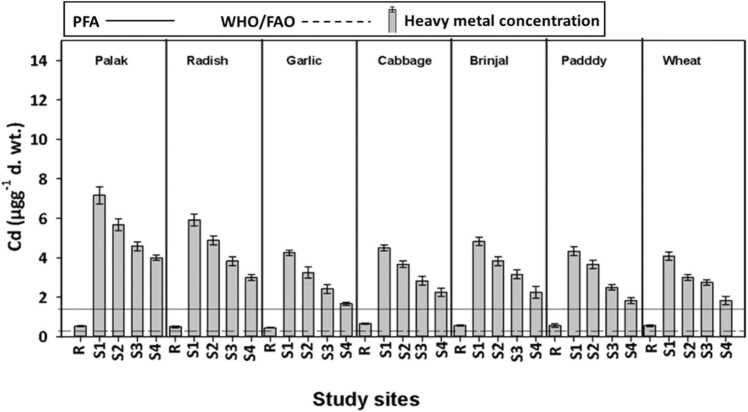

3.4. Heavy metals content in vegetables and cereal crops

The concentrations of heavy metals in vegetables and cereal crops produced under different irrigation regimes in the vicinity of a carpet industrial area are given in Fig. 3, Fig. 4. The average concentration of Cu (µg g−1 dw) in the edible part of B. vulgaris, R. sativus, A. sativum, B. oleracea, S. melongena, O. sativa, and T. aestivum were as 12.2, 13.83, 7.12, 13.8,11.24, 23.30 and 27.97, respectively in wastewater irrigated area which is found higher than ground water irrigated area (and 4.2, 2.6, 2.2, 3.6, 3.83, 6.1 and 5.5, respectively). In the present study, Cr concentration was found maximum in the grains of T. aestivum among all the tested crops irrigated with both wastewater and ground water (17.08 µg g−1 dw and 2.66 µg g−1 dw, respectively). The results also showed that Cr concentration below PFA guideline [8] (20 µg g−1 dw) in the edible parts of B. vulgaris, R. sativus, A. sativum, B. oleracea, S. melangena and O. sativa except T. aestivum. The concentration of Ni was found maximum in wastewater and ground water irrigated grains of T. aestivum (42.33 µg g−1 dw and 4.5 µg g−1 dw, respectively) and minimum in S. melongena (10.29 µg g−1 dw and 3.25 µg g−1 dw, respectively) among all the test crops.

Fig. 3.

Concentration of Cd in edible parts of tested vegetables and cereal crops collected from wastewater irrigated suburban ecosystems. Bars are mean ± SE of three replicates. Solid and dashed lines represent PFA and WHO/FAO safety limit of Cd, respectively [8], [14]. X-axis showed the study sites i.e., R (reference site; groundwater irrigated areas) and S1, S2, S3 and S4 (wastewater irrigated sites).

Fig. 4.

Concentration of Cu, Zn, Cr and Ni in edible parts of tested vegetables and cereal crops collected from wastewater irrigated suburban ecosystems. Bars are mean ± SE of three replicates. Solid and dashed line represents PFA and WHO/FAO safety limit of heavy metals, respectively [8], [14]. X-axis showed the study sites i.e. R (reference site; groundwater irrigated areas) and S1, S2, S3 and S4 (wastewater irrigated sites).

Copper concentration in edible parts of all the tested vegetable crops was found within the safe limits set by both the national and international agencies [53]. The application of wastewater has elevated the Cu concentration in T. aestivum and O. sativa crops above both the national and international safe limits [8], [14]. Irrigation of vegetables with municipal waste dominated stream had elevated the concentrations of Cd, Cr, Ni, and Zn as 0.02 µg g−1 dw, < 0.001 µg g−1 dw, < 0.001 µg g−1 dw and 0.08 µg g−1 dw, respectively in the edible part of B. oleracea and 0.014 µg g−1 dw, < 0.001 µg g−1 dw, < 0.01 µg g−1 dw, < 0.001 µg g−1 dw, respectively in R. sativus reported by Affum et al. [1]. The pH of wastewater irrigated soil plays an important role in the translocation of heavy metals from soil to plants by changing the solubility of heavy metals in the soil. Heavy metal solubility increases at lower or acidic pH and decreases at higher or basic pH. In the present study, wastewater irrigated soil had lower pH (acidic) than ground water irrigated soil. Thus, pH may provide more suitable conditions for the solubilization of heavy metals in the soil and facilitate their translocation to the foodstuffs easily [52]. The variations in the concentration of heavy metals in different tested crops are ascribed to the selective absorption capability of plants [67]. Heavy metal concentrations in wastewater irrigated crops were many folds higher than ground water irrigated crops.

Among the tested vegetables and cereal crops, B. vulgaris from wastewater irrigated areas had higher Zn and Cd concentration (58.4 µg g−1 dw, 5.35 µg g−1 dw, respectively) and lowest in A. sativum (37.37 µg g−1 and 2.89 µg g−1 dw, respectively). Concentrations of Cd, Zn, and Cr in B. vulgaris or spinach (0.049, 10.51, and 0.47 µg g−1, respectively) were found lower than in B. oleracea var. sabellica or kale (0.09, 15.33 and 0.84 µg g−1, respectively) but Cu was found higher concentration in spinach (7.45 µg g−1) than kale (1.93 µg g−1) grown in Machakos municipality in Kenya [59]. Chemical compositions of municipal wastewater were recorded as significantly different from those of ground water. The results of the present study showed that B. vulgaris have higher heavy metals accumulation potential than the L. sativa plants. Leafy vegetables have accumulated significantly higher concentrations of heavy metals than fruit vegetables due to higher rates of transpiration and translocation [28]. Plants with multiple thin roots i.e., adventitious roots have high accumulation potential of heavy metals than those with few thick roots i.e., tap roots due to an increase in the surface area reported by Chandran et al. [12].

The sustainability of soil health when urban wastewater or dilutes are used for growing crops is a tough environmental challenge in urban or suburban agriculture. Wastewater irrigated vegetable crops e.g., S. melongena, B. vulgaris, B. oleracea var. botrytis L. and L. sativa L. cultivated at six sites in the suburban area of Multan city, Pakistan for a two-year to evaluate the comparative vegetable transfer factors (VTFs) reported by Ahmad et al. [2]. VTF had demonstrated that B. vulgaris has the highest values for Zn, Cu, Cd, Cr and Ni (i.e., 20.2 µg g−1 dw, 12.3 µg g−1 dw, 6.1 µg g−1 dw, 7.6 µg g−1 dw, and 9.2 µg g−1 dw, respectively) and is an important and best phytoextractant followed by B. oleracea var. botrytis and S. melongena, while L. sativa had the lowest heavy metal level [2]. The buildup of heavy metals in Trigonella foenum-graecum L., B. vulgaris, S. melongena and Capsicum annum L. in different seasons and a major health threat to adult human was associated with the consumption of such vegetables cultivated in Jhansi [20]. A total of 28 composites of soils and vegetables collected from seven agricultural fields were analyzed for total amount of Zn, Ni, Cu, and Cd. The target hazard quotients of Cd for T. foenum-graecum (2.16) and B. vulgaris (3.7) indicated a considerable non-carcinogenic health concern if ingested regularly by humans.

3.5. Drivers of heavy metals in soils

In the present study, the pH of ground water irrigated soil i.e., 7.94 was found higher than the 4 sub-sites of wastewater irrigated soil i.e., 6.83, 7.11, 7.21, 7.32, respectively. The results revealed that wastewater is a source of acidic compounds and their long-term use can reduce the pH of soil. This may be ascribed to the synthesis of carbon dioxide (CO2) and organic acids by the soil microbial population. The nutrients and organic matter introduced into the soil by wastewater irrigation may boost the activity of soil microorganisms [40]. The acid content of the soil may be the major cause of the negative relationship between soil pH and heavy metal accumulation in different food stuffs as shown in Fig. 5. In an acidic environment, heavy metal bioavailability is increased, making heavy metals more available to plants [38]. Soil pH directly affected the accessibility of heavy metals in soil - wheat systems reported by Ahmad et al. [3]. The pH of groundwater and wastewater irrigated soil were 8.0 and 7.6, respectively. The concentrations of Cd, Cr, Ni, Cu and Zn in grains of wheat irrigated with groundwater and wastewater were1.25, 0.38, 0.63, 0.71 and 0.10 and 1.69, 0.57, 0.92, 1.46 and 0.90 µg g−1, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Heat map model of relationship between soil properties (pH and organic matter) and heavy metal in crops.

Organic matter content in soil at 4 sub sites irrigated with wastewater (4.97 %, 4.82 %, 4.65 %, 4.50 %, respectively) was found higher than ground water irrigated soil (3.38 %). The positive relationship between soil organic matter content and heavy metal concentrations in growing plant components could be addressed by the fact that a large amount of organic material in the soil led to increased heavy metal accessibility to the plants (Fig. 5). Heavy metals are more accessible in such soil and can exist in more exchangeable groups [71]. Organic compounds that act as chelates are also delivered into the soil by organic matters, enhancing heavy metal bioavailability [33]. A similar trend showed that higher levels of organic matter in soil were proven to enhance heavy metal uptake by wheat crops reported by Rupa et al. [46].

3.6. Health risk assessment

3.6.1. Enrichment factor

Higher values of enrichment factor suggested poor retention capacity of heavy metals in the soil and have more translocation capacity in the plants. The present study showed maximum EF values for Zn, Ni, Cu, Cd, and Cr were 3.9, 3.3, 1.6, 6.5, and 2.4, respectively for S. melongena, R. sativus, T. aestivum, B. vulgaris and T. aestivum (Table 3). The mean EF value was found maximum for Cd followed by Zn, Ni, Cr and least for Cu. The results further showed that vegetables had a comparatively higher EF value than the cereal crops which may be ascribed their higher transpiration rate to maintain the moisture content and growth rate [56]. Enrichment factor values of the heavy metals depend upon their bioavailable forms, uptake capacity, and plant growth rate, etc. The present EF values for Cd and Ni were found lower than EF values reported in B. oleracea (10.9) and in Amaranthus (20.69), respectively by Singh et al. [54].

Table 3.

Mean (range) values of Enrichment factor (EF) and Bioconcentration factor (BCF) of heavy metals for foodstuffs collected from the suburban agricultural areas of Bhadohi, India.

| Food crops | Heavy Metals |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn |

Ni |

Cu |

Cd |

Cr |

||||||

| EF | BCF | EF | BCF | EF | BCF | EF | BCF | EF | BCF | |

| B. vulgaris | 2.9 (2.7–3.0) |

0.7 (0.7–0.7) |

1.9 (1.8–2) |

0.3 (0.2–0.3) |

0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

0.2 (0.2–0.2) |

6.5 (5.8–7.4) |

1.6 (1.5–1.6) |

1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

0.09 (0.08–0.1) |

| R. sativus | 2.9 (2.1–3.4) |

0.5 (0.4–0.6) |

3.3 (2.8–3.6) |

0.4 (0.4–0.5) |

1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

0.2 (0.2–0.2) |

5.3 (4.2–6.2) |

1.5 (1.2–1.8) |

1.2 (0.3–1.4) |

0.1 (0.1–0.13) |

| A. sativum | 2.3 (1.7–2.6) |

0.4 (0.3–0.5) |

2.2 (1.8–2.5) |

0.3 (0.3–0.4) |

0.5 (0.5–0.6) |

0.1 (0.1–0.1) |

4.0 (3.0–5.0) |

0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

0.8 (0.5–1.1) |

0.08 (0.04–0.1) |

| B. oleracea | 2.4 (2.1–2.6) |

0.4 (0.4–0.5) |

2.3 (1.9–2.7) |

0.5 (0.4–0.6) |

1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

0.1 (0.1–0.2) |

3.2 (2.6–3.7) |

1.0 (0.7–1.3) |

0.6 (0.4–0.8) |

0.07 (0.03–0.1) |

| S. melongena | 3.9 (3.7–4.1) |

ND | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

ND | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

ND | 5.8 (4.7–6.5) |

ND | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

ND |

| O. sativa | 1.8 (1.7–1.8) |

1.0 (0.9–1.0) |

2.2 (1.7–2.7) |

1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

1.5 (1.3–1.7) |

1.7 (1.6–1.9) |

3.9 (2.7–4.7) |

2.4 (1.6–3.3) |

2.2 (1.7–2.6) |

0.5 (0.4–0.6) |

| T. aestivum | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) |

1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

3.0 (2.6–3.2) |

1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

1.6 (1.4–1.9) |

1.6 (1.5–1.7) |

3.0 (2.0–3.5) |

1.3 (0.8–1.6) |

2.4 (1.5–3.1) |

0.7 (0.5–0.8) |

| Mean (Min-Max) |

2.6 (1.8–3.9) |

0.6 (0.4–1) |

2.2 (0.9–3.3) |

0.5 (0.4–1.2) |

1.1 (0.5–1.6) |

0.55 (0.3–1.7) |

4.52 (3–6.5) |

1.24 (0.9–2.4) |

1.34 (0.6–2.4) |

0.2 (0.07–0.7) |

ND= Not detected

3.6.2. Bioconcentration factor

The results showed that the BCF value for the tested crops ranged from a minimum of 0.07 for Cr in B. oleracea to a maximum of 2.4 for Cd in O. sativa (Table 3). BCF values for Cu, Cd, Zn, Pb, and Ni in the roots of T. aestivum as 3.2, 2.6, 1.3, 1.1, and 0.99, respectively reported by Rezapour et al. [43]. However, the BCF values for the T. aestivum crop in the present study were found higher than the values reported by Rezapour et al. [43]. The higher BCF value may be due to the combination of several factors including total concentrations of heavy metals and their different chemical forms [44].

3.6.3. Transfer factor

In the present study, Cd showed the highest TF value followed by Ni, Zn, Cu and the least for Cr (2.43, 1.1, 0.87, 0.76 and 0.52, respectively) in B. vulgaris, T. aestivum, S. melongena, O. sativa and T. aestivum, respectively (Table 4). In all the vegetables and cereal crops, Cd had the highest value of TF which indicates its highest mobility potency. Highest TF value for the Cd in B. oleracea var. botrytis and B. oleracea var. capitata (0.61 and 2.96, respectively) was reported by Singh et al. [54]. Variability in the TF value of heavy metal for different vegetables may be ascribed to the degree of heavy metal contamination in soil and variations in uptake capability of the crops [72].

Table 4.

Transfer factor and metal pollution index of heavy metals and their load in growing foodstuffs in the suburban agricultural areas of Bhadohi, India.

| Foodstuffs | Transfer factor |

Metal pollution index |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn |

Ni |

Cu |

Cd |

Cr |

||||||||

| Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Min-Max | Mean | |

| B. vulgaris | 0.78–0.88 | 0.84 | 0.43–0.46 | 0.44 | 0.28–0.31 | 0.29 | 2.18–2.75 | 2.43 | 0.17–0.20 | 0.18 | 11.54–16.10 | 13.79 |

| R. sativus | 0.39–0.63 | 0.54 | 0.38–0.49 | 0.44 | 0.22–0.26 | 0.24 | 1.22-1.79 | 1.54 | 0.10–0.13 | 0.11 | 7.75–12.01 | 10.09 |

| A. sativum | 0.31–0.48 | 0.39 | 0.26–0.36 | 0.30 | 0.08–0.10 | 0.09 | 0.68-1.15 | 0.88 | 0.04–0.11 | 0.08 | 6.18–11.73 | 9.05 |

| B. oleracea var. capitata | 0.53–0.65 | 0.58 | 0.53–0.83 | 0.66 | 0.30–0.34 | 0.32 | 1.22-1.73 | 1.50 | 0.07–0.16 | 0.12 | 8.06–15.87 | 12.07 |

| S. melongena | 0.83–0.90 | 0.87 | 0.22–0.27 | 0.25 | 0.29–0.33 | 0.31 | 1.97-1.71 | 1.82 | 0.15–0.19 | 0.17 | 7.48–13.08 | 10.31 |

| O. sativa | 0.64–0.69 | 0.66 | 0.77-1.19 | 0.98 | 0.69–0.88 | 0.76 | 1.27–2.24 | 1.82 | 0.31–0.46 | 0.39 | 11.58–21.80 | 16.49 |

| T. aestivum | 0.72–0.79 | 0.74 | 0.92-1.18 | 1.1 | 0.63–0.89 | 0.72 | 0.87-1.47 | 1.21 | 0.34–0.69 | 0.52 | 12.75–24.38 | 18.34 |

| Average (Range) | 0.66 (0.39–0.87) | 0.59 (0.25-1.10) | 0.39 (0.09–0.76) | 1.60 (0.88–2.43) | 0.22 (0.08–0.52) | 12.87 (9.05–18.34) | ||||||

3.6.4. Metal pollution index

Metal pollution index approach is a precise and effective way for monitoring of the heavy metal pollution load in a contaminated soil. In the present study, the MPI was found highest in T. aestivum followed by O. sativa, B. vulgaris, B. oleracea, S. melongena, R. sativus and least in the O. sativa crops (18.3, 16.5, 13.8, 12.1, 10.3, 10.1 and 9.1, respectively) (Table 4). Cereal crops had higher concentrations of heavy metals as compared to the vegetables which caused higher MPI than the vegetables. Lower MPI for T. aestivum, O. sativa, R. sativus and B. oleracea (6.9, 7.3, 9.7, and 11.8, respectively) than the MPI for present crops were reported by Singh et al. [54]. This may be ascribed due to intensive industrialization of carpet industries and domestic wastewater discharges, etc., in the studied areas.

3.6.5. Daily intake of heavy metals

Daily intake of heavy metals represents the average daily intake of heavy metals through vegetables, cereal crops, etc., and is expressed as µg g−1/day. The average DIM of tested heavy metals by both the adult and children population living in the study areas is given in Table 5. The daily intake of Zn by the children or adult population via B. vulgaris was found maximum whereas the daily intake of Cd via O. sativa was found minimum (Table 5). The maximum daily intake of heavy metal by local residents was recorded for Ni (0.288 µg g−1/day by children) through T. aestivum consumption and minimum for Cr (0.001 µg g−1/day by an adult) via consumption of R. sativus and A. sativum. The exposure of local inhabitants to heavy metals was found higher through cereal crops as compared to the vegetable crops which may be ascribed to more consumption frequency of cereal crops. Daily intake of heavy metals for both the children and adults was found in decreasing order as Zn >Ni >Cu >Cr >Cd. The present results indicated that the daily consumption of Zn, Cd, Cr, Cu, and Ni may rise exponentially as the wastewater irrigation frequency increased. The use of wastewater for irrigation is a common practice in peri-urban areas of Faisalabad, Pakistan. Daily intake of heavy metals of Cr, Ni and Cd via consumption of T. aestivum produced under wastewater irrigation practices were found as 1.38, 1.10, 1.22 µg g−1/day respectively reported by Nawaz et al. [37].

Table 5.

Daily intake of heavy metals (DIM: µg g-1/day) and Health quotient produced of vegetables and cereal crops produced in Suburban agricultural areas of Bhadohi, India.

| Food crops | Heavy Metals |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu |

Ni |

Zn |

Cd |

Cr |

|||||||

| DIM | HQ | DIM | HQ | DIM | HQ | DIM | HQ | DIM | HQ | ||

| B. vulgaris | Children | 0.007 | 0.175 | 0.011 | 0.550 | 0.033 | 0.110 | 0.003 | 3.000 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Adult | 0.006 | 0.150 | 0.010 | 0.500 | 0.029 | 0.096 | 0.002 | 2.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | |

| R. sativus | Children | 0.005 | 0.125 | 0.012 | 0.600 | 0.021 | 0.070 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Adult | 0.005 | 0.125 | 0.010 | 0.500 | 0.018 | 0.060 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.0006 | |

| A. sativum | Children | 0.002 | 0.050 | 0.009 | 0.450 | 0.015 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.0006 |

| Adult | 0.002 | 0.050 | 0.007 | 0.350 | 0.013 | 0.043 | 0.0008 | 0.800 | 0.001 | 0.0006 | |

| B. oleracea | Children | 0.007 | 0.175 | 0.017 | 0.850 | 0.023 | 0.076 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Adult | 0.006 | 0.150 | 0.016 | 0.800 | 0.020 | 0.066 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | |

| S. melongena | Children | 0.006 | 0.150 | 0.006 | 0.300 | 0.030 | 0.100 | 0.002 | 2.000 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Adult | 0.005 | 0.125 | 0.005 | 0.250 | 0.028 | 0.100 | 0.002 | 2.000 | 0.003 | 0.002 | |

| O. sativa | Children | 0.164 | 4.1 | 0.263 | 13.15 | 0.255 | 0.85 | 0.021 | 21.00 | 0.090 | 0.06 |

| Adult | 0.143 | 3.6 | 0.228 | 11.4 | 0.222 | 0.74 | 0.018 | 18.00 | 0.078 | 0.05 | |

| T. aestivum | Children | 0.198 | 4.9 | 0.288 | 14.4 | 0.281 | 0.93 | 0.020 | 20.00 | 0.117 | 0.08 |

| Adult | 0.172 | 4.3 | 0.251 | 12.5 | 0.244 | 0.81 | 0.017 | 17.00 | 0.099 | 0.07 | |

3.6.6. Health quotient

The data generated in the present study for the HQ revealed that Cd, Ni and Cu contaminated cereal crops could pose a health risk to the local residents. If, the HQ value exceeds a unit for both children and adult, the heavy metals may pose a high health risk to the entire exposed population [4]. Health quotient value of Cu, Ni, and Cd was found over a unit for both children and adults consuming T. aestivum and O. sativa crops. Health quotient value of Zn and Cr were found below a unit for both adult and children population (Table 5). Health quotient value of Zn, Ni, Cr, and Cu showed no health risk in children and adult from the consumption of vegetables as the HQ value was < 1 (Table 5). The HQ of Cd was found above a unit for B. vulgaris, A. sativum, R. sativus, and B. oleracea (Table 5). The lowest HQ was found for Cr in A. sativum (0.0006 in both children and adult), whereas the highest HQ was found for Cd in O. sativa (21 and 18 for children and adult, respectively). As compared to adults, children are at higher risk due to ingestion of heavy metal contaminated edible crops produced under wastewater irrigation regimes. Leafy vegetables had higher Zn and Cu health risk levels than fruit and root vegetables. The cumulative health risk levels obtained in this study suggested that the values obtained for most of the metals in diverse food crops were greater for children than for adults studied by Rehman et al. [42]. As a result, it is claimed that children, as compared to adults, may be more vulnerable to metal exposure from vegetable diet.

3.7. Regression analysis of heavy metals contaminated soil and crops

Regression analyses were performed between the concentrations of heavy metals (Cd, Cr, Ni, Cu and Zn) in edible parts of vegetables and cereal crops, i.e. palak, radish, garlic, cabbage, brinjal, paddy and wheat versus total soil heavy metals at harvesting stage of plant growth and the results are shown in Fig. 6. The R2 value was analyzed to measure the relationship between heavy metals in the soil and heavy metals in plant edible portions. The maximum R2 value was found for Cr in soil- brinjal (0.96) followed by soil-palak (0.93), soil-radish (0.88), soil-garlic (0.92), soil-cabbage (0.95), soil-paddy (0.95), soil-wheat (0.92). Whereas the minimum R2 value was found for Zn in soil-radish (0.03), followed by soil-palak (0.80), soil-garlic (0.19), c soil-cabbage (0.64), soil-brinjal (0.76), soil-paddy (0.95) and soil-wheat (0.92). Similar results were also reported by Bose et al. [10] that regression analyses were performed with the concentrations of each of the eight heavy metals in the pea grain-soil system with minimum R2 value for Zn (0.16) and maximum for Cd (0.82).

Fig. 6.

Regression correlation between heavy metals concentration in soil and edible parts of vegetables and cereal crops. R2 is the correlation coefficient (percentage of variance accounted for by the regression model). Levels of significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and NS = Non-significant. X-axis showed the concentration of heavy metal in soil.

In the present study, the correlation between total heavy metals in soil with their concentration in tested crops were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Linear regression equation for Zn failed to be established in garlic and radish (p > 0.05). Heavy metal builds up in various vegetables and cereal crops are mostly determined by the total heavy metal concentration in the soil. Higher amount of Cd treatment (0.12–0.33 µg g−1) in soil increased the contamination level in paddy seeds [68]. The present study further suggests that more researches into mineral fertilization with micronutrients is required as long-term application of wastewater for irrigation may lead to increased accumulation of heavy metal in the soil and hence enhanced their availability to growing plants [35].

The present study revealed that analyzed carpet industry effluents were not safe for disposal to the natural water bodies as it is contaminated with heavy metals such as Cd, Ni, Cr, Cu and Zn, which may pose serious health risk to aquatic organisms. The heavy metal contents in the wastewater irrigated food crops were also higher than the groundwater irrigated food crops. In this study area, multiple and diverse food crops having low heavy metal accumulating potential are recommended for cultivation to reduce the health risk of heavy metal to the local population due to the dietary exposure. This study also estimates certain future perspectives based on the current scenario of wastewater utilisation, potential exposure of human to heavy metals, and associated health risks at local and global scale. The quality of natural water bodies receiving the contaminated effluents, associated risk to aquatic organisms and biomagnification of the heavy metals should be studied in future using a multidisciplinary approach.

4. Conclusion

In the present study, the concentrations of heavy metals in irrigation water, soil, and edible parts of vegetables and cereal crops produced in the vicinity of a carpet industrial area of northern India were quantified and associated health risk to the local population was assessed. Cd concentration in all the tested vegetables and cereal crops has exceeded both the national and International safety limits, whereas Ni exceeds only the national safe limit. Daily intake of Cu, Ni, Cd, Zn, and Cr by the local peoples via cereal crops was found more as compared to vegetables. Long-term intake of vegetables and cereal crops contaminated with higher levels of heavy metals can lead to a higher accumulation of heavy metals in the human body and may cause associated health disorders. Thus there is an urgent need to develop or modify the existing policies with respect to wastewater treatment and safe use, particularly in agriculture. Governments and industries may assume mutual responsibility for the treatment of contaminated wastewater before its disposal in natural water bodies and should educate the farmers for better wastewater-based farming practices. In this scenario, the results of the present study would be very helpful to policymakers and stakeholders to develop guidelines for reducing the heavy metals in the suburban food system in order to minimize the risk associated with human and environmental health as well as the safety of foods.

Funding

No financial supports were received for this particular work, however, funds from BHU Seed, UGC-Startup and IoE-BHU grants were used to execute this work.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Rajesh Kumar Sharma and Prince Kumar Singh designed the study. Prince Kumar Singh performs the experimental work. Prince Kumar Singh analyse the data and wrote the manuscript. Jayshankar Yadav, Indrajeet Kumar and Umesh Kumar help in experimental work, data analysis and formatting the manuscript. Rajesh Kumar Sharma supervised the research work and provide valuable suggestions for manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

Authors are highly thankful to the Head, of the Department and Coordinator of center of advanced study in Botany, Department of Botany, Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India for providing the necessary research facilities for the present work. PKS, IK, and UK are also thankful to UGC, New Delhi for providing the Junior and Senior Research Fellowship.

Handling Editor: L.H. Lash

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Affum A.O., Osae S.D., Kwaansa-Ansah E.E., Miyittah M.K. Quality assessment and potential health risk of heavy metals in leafy and non-leafy vegetables irrigated with groundwater and municipal-waste-dominated stream in the Western Region, Ghana. Heliyon. 2020;6(12) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmad I., Malik S.A., Saeed S., Rehman A.U., Munir T.M. Phytoextraction of heavy metals by various vegetable crops cultivated on different textured soils irrigated with City Wastewater. Soil Syst. 2021;5(2):35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad K., Wajid K., Khan Z.I., Ugulu I., Memoona H., Sana M., Nawaz K., Malik I.F., Bashir H., Sher M. Evaluation of potential toxic metals accumulation in wheat irrigated with wastewater. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019;102(6):822–828. doi: 10.1007/s00128-019-02605-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali Z., Kazi A., Quraishi U.M., Malik R.N. Deciphering adverse effects of heavy metals on diverse wheat germplasm on irrigation with urban wastewater of mixed municipal-industrial origin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25(19):18462–18475. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1996-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allison L.E. In: Methods of Soil Analysis, Part1. Klute A., editor. American Soc. Agron.; Madison, WI: 1986. Organic carbon; pp. 1367–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 6.APHA . American Public Health Association; Washington D.C, USA: 2005. American Public Health Association. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arora M., Kiran B., Rani S., Rani A., Kaur B., Mittal N. Heavy metal accumulation in vegetables irrigated with water from different sources. Food Chem. 2008;111(4):811–815. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.04.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awashthi S.K. Prevention of food Adulteration Act No. 37 of 1954. Central and state Rules as Amended for 1999. Third ed. Ashoka Law House; New Delhi: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhardwaj R., Yadav S.P., Singh R.K., Tripathi V.K. New Frontiers in Stress Management for Durable Agriculture:(169–183) Springer; 2020. Crop growth under heavy metals stress and its mitigation. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bose S., Chandrayan S., Rai V., Bhattacharyya A.K., Ramanathan A.L. Translocation of metals in pea plants grown on various amendment of electroplating industrial sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2008;99(10):4467–4475. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buat-Menard P., Chesselet R. Variable influence of the atmospheric flux on the trace metal chemistry of oceanic suspended matter. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1979;42:398–411. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(79)90049-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandran S., Niranjana V., Benny J. Accumulation of heavy metals in wastewater irrigated crops in Madurai. India J. Environ. Res.Dev. 2012;6(3):432–438. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaoua S., Boussaa S., El Gharmali A., Boumezzough A. Impact of irrigation with wastewater on accumulation of heavy metals in soil and crops in the region of Marrakech in Morocco. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018;18(4):429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jssas.2018.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Codex Alimentarious Commission . First ed. Codex Alimentarious; Geneva: 1984. Contaminants, Joint FAO/WHO Food standards Program. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compagni R.D., Gabrielli M., Polesel F., Turolla A., Trapp S., Vezzaro L., Antonelli M. Risk assessment of contaminants of emerging concern in the context of wastewater reuse for irrigation: An integrated modelling approach. Chemosphere. 2020;242 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui Y.J., Zhu Y.G., Zhai R.H., Chen D.Y., Huang Y.Z., Qiu Y., Liang J.Z. Transfer of metals from soil to vegetables in an area near a smelter in Nanning, China. Environ. Int. 2004;30(6):785–791. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge K.Y. Beijing People’s Hygiene Press; 1992. The status of nutrient and meal of Chinese in the 1990s; pp. 415–434. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gemeda F.T., Guta D.D., Wakjira F.S., Gebresenbet G. Occurrence of heavy metal in water, soil, and plants in fields irrigated with industrial wastewater in Sabata town, Ethiopia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28(10):12382–12396. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guadie A., Yesigat A., Gatew S., Worku A., Liu W., Ajibade F.O., Wang A. Evaluating the health risks of heavy metals from vegetables grown on soil irrigated with untreated and treated wastewater in Arba Minch, Ethiopia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;761 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta N., Yadav K.K., Kumar V., Krishnan S., Kumar S., Nejad Z.D., Khan M.M., Alam J. Evaluating heavy metals contamination in soil and vegetables in the region of North India: Levels, transfer and potential human health risk analysis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021;82 doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2020.103563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta S., Srivastava R.K. Health impacts of exposure to chemicals of dye industry waste. Int. J. Fiber Text. Res. 2017;7(1):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson M.L. Vol. 498. Pentice Hall of India Pvt. Ltd.; New Delhi, India: 1973. pp. 151–154. (Soil chemical analysis). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaasalainen M., Yli-Halla M. Use of sequential extraction to assess metal partitioning in soils. Environ. Pollut. 2003;126:225–233. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(03)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kabata-Pendias A., Mukherjee A.B. Springer- Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 2007. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalavrouziotis I.K., Rezapour S., Koukoulakis P.H. Wastewater status in Greece and Iran. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2013;22(1):11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karimi A. Contradiction and change in the carpet industry of Bhadohi. Indian J. 2016;6(2):171–179. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalid S., Shahid M., Natasha I.B., Sarwar T., Shah A.H., Niazi N.K. A review of environmental contamination and health risk assessment of wastewater use for crop irrigation with a focus on low and high-income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(5(895)):1–36. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar A., Seema Accumulation of heavy metals in soil and green leafy vegetables, irrigated with wastewater. J. Environ. Sci., Toxicol. Food Technol. 2016;10:08–19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar V., Thakur R.K., Kumar P. Predicting heavy metals uptake by spinach (Spinacia oleracea) grown in integrated industrial wastewater irrigated soils of Haridwar India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020;192(11):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10661-020-08673-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumari L., Tiwary D., Mishra P.K. Biodegradation of CI Acid Red 1 by indigenous bacteria Stenotrophomonas sp. BHUSSp X2 isolated from dye contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016;23(5):4054–4062. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L., Zhang Y., Ippolito J.A., Xing W., Qiu K., Yang H. Lead smelting effects heavy metal concentrations in soils, wheat, and potentially humans. Environ. Pollut. 2020;257 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahmood A., Mahmoud A.H., El-Abedein A.I.Z., Ashraf A., Almunqedhi B.M. A comparative study of metals concentration in agricultural soil and vegetables irrigated by wastewater and tube well water. J. King Saud. Univ. -Sci. 2020;32(3):1861–1864. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2020.01.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCauley A., Jones C., Jacobsen J. Soil pH and organic matter. Nutr. Manag. Modul. 2009;8(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melero Sánchez S., Madejón E., Herencia J.F., Ruiz‐Porras J.C. Long‐term study of properties of a xerofluvent of the Guadalquivir River Valley under organic fertilization. Agron. J. 2008;100(3):611–618. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nacke H., Gonçalves A.C., Schwantes D., Nava I.A., Strey L., Coelho G.F. Availability of heavy metals (Cd, Pb, and Cr) in agriculture from commercial fertilizers. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2013;64(4):537–544. doi: 10.1007/s00244-012-9867-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naorem A., Huirem B., Udayana S.K. Sustainable Management and Utilization of Sewage Sludge. Springer; Cham: 2022. Ecological and health risk assessment in sewage irrigated heavy metal contaminated soils; pp. 29–50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nawaz H., Anwar-ul-Haq M., Akhtar J., Arfan M. Cadmium, chromium, nickel and nitrate accumulation in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using wastewater irrigation and health risks assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;208 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novotná M., Mikeš O., Komprdová K. Development and comparison of regression models for the uptake of metals into various field crops. Environ. Pollut. 2015;207:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oubane M., Khadra A., Ezzariai A., Kouisni L., Hafidi M. Heavy metal accumulation and genotoxic effect of long-term wastewater irrigated peri-urban agricultural soils in semiarid climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasheed M.J.Z., Ahmad K., Khan Z.I., Mahpara S., Ahmad T. Assessment of trace metal contents of indigenous and improved pastures and their implications for livestock in terms of seasonal variations. Rev. De. Chim. 2020;71(7):347–364. doi: 10.37358/RC.20.7.8253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rattan R.K., Datta S.P., Chhonkar P.K., Suribabu K., Singh A.K. Longterm impact of irrigation with sewage effluents on heavy metal contents in soils, crops and ground water – a case study. Agric., Ecosyst. Environ. 2005;109:310–322. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rehman Z.U., Khan S., Shah M.T., Brusseau M.L., Khan S.A., Mainhagu J. Transfer of heavy metals from soils to vegetables and associated human health risks at selected sites in Pakistan. Pedosphere. 2018;28(4):666–679. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(17)60440-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rezapour S., Atashpaz B., Moghaddam S.S., Damalas C.A. Heavy metal bioavailability and accumulation in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) irrigated with treated wastewater in calcareous soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;656:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rezapour S., Moazzeni H. Assessment of the selected trace metals in relation to long-term agricultural practices and landscape properties. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;13:2939–2950. doi: 10.1007/s13762-016-1146-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rule J.H. In: Adsorption and its Applications industry and environmental protection, Vol. II: applications in environmental protection. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis. Dabrowski A., editor. Elsevier; 1998. Trace metal cation adsorption in soils: selective chemical extractions and biological availability; pp. 319–349. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rupa T.R., Rao C.S., Rao A.S., Singh M. Effects of farmyard manure and phosphorus on zinc transformations and phytoavailability in two alfisols of India. Bioresour. Technol. 2003;87(3):279–288. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(02)00235-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sager M., Park J.H., Chon H.T. The effect of soil bacteria and perlite on plant growth and soil properties in metal contaminated samples. Water, Air Soil Pollut. 2007;179:265–281. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sardar A., Shahid M., Khalid S., Anwar H., Tahir M., Shah G.M., Mubeen M. Risk assessment of heavy metal (loid) s via Spinacia oleracea ingestion after sewage water irrigation practices in Vehari District. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;27(32):39841–39851. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09917-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarkar S.R., Majumdar A., Barla A., Pradhan N., Singh S., Ojha N., et al. A conjugative study of Typha latifolia for expunge of phyto-available heavy metals in fly ash ameliorated soil. Geoderma. 2017;305:354–362. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma R.K., Agrawal M., Marshall F.M. Heavy metal (Cu, Zn, Cd and Pb) contamination of vegetables in urban India: a case study in Varanasi. Environ. Pollut. 2008;154:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma R.K., Agrawal M., Marshall F.M. Heavy metals contamination of soil and vegetables in suburban areas of Varanasi, India. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2007;66:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheoran V., Sheoran A.S., Poonia P. Factors affecting phytoextraction: a review. Pedosphere. 2016;26:148–166. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(15)60032-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh A., Sharma R.K., Agrawal M., Marshall F. Effects of wastewater irrigation on physicochemical properties of soil and availability of heavy metals in soil and vegetables. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2009;40(21–22):3469–3490. doi: 10.1080/00103620903327543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh A., Sharma R.K., Agrawal M., Marshall F.M. Risk assessment of heavy metal toxicity through contaminated vegetables from waste water irrigated area of Varanasi, India. Trop. Ecol. 2010;51(2):375–387. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh G., Upadhyay S.K., Singh M.P. Dye-decolorization by native bacterial isolates, isolated from sludge of carpet industries Bhadohi-India. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;2(6):81–85. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tani F.H., Barrington S. Zinc and copper uptake by plants under two transpiration ratios Part I. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Environ. Pollut. 2005;138:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tessier A., Campbell P.G., Bisson M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Anal. Chem. 1979;51(7):844–851. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thebo A.L., Drechsel P., Lambin E., Nelson K. A global, spatially-explicit assessment of irrigated croplands influenced by urban wastewater flows. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017;12(7) doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa75d1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomno R.M., Nzeve J.K., Mailu S.N., Shitanda D., Waswa F. Heavy metal contamination of water, soil and vegetables in urban streams in Machakos municipality, Kenya. Sci. Afr. 2020;9 doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.USEPA, 2004. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund Vol. I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part E, Supplemental Guidance for Dermal Risk Assessment).

- 61.Usero J., Gonzalez-Regalado E., Gracia I. Trace metals in the bivalve mollusks Ruditapes decussates and Ruditapes phillippinarum from the Atlantic Coast of Southern Spain. Environ. Int. 1997;23(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(97)00030-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang X., Sato T., Xing B., Tao S. Health risks of heavy metals to the general public in Tianjin, China via consumption of vegetables and fish. Sci. Total Environ. 2005;350:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.WHO/UNICEF , 2015. Joint monitoring programme for water supply and sanitation. Progress on drinking water and sanitation. (http:// www.wssinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/resources/JMP-2015- update-press-release English.pdf.

- 64.Wilcke W., Kaupenjohann M. Heavy metal distribution between soil aggregate core and surface fractions along gradients of deposition from the atmosphere. Geoderma. 1998;83:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Health Organization . vol. 2. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. Guidelines for the safe use of wastewater excreta and greywater. (Wastewater Use in Agriculture). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xiao L., Guan D., Peart M.R., Chen Y., Li Q. The respective effects of soil heavy metal fractions by sequential extraction procedure and soil properties on the accumulation of heavy metals in rice grains and brassicas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017;24(3):2558–2571. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-8028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yadav K.K., Gupta N., Kumar A., Reece L.M., Singh N., Rezania S., Khan S.A. Mechanistic understanding and holistic approach of phytoremediation: a review on application and future prospects. Ecol. Eng. 2018;120:274–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2018.05.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ye X., Li H., Ma Y., Wu L., Sun B. The bioaccumulation of Cd in rice grains in paddy soils as affected and predicted by soil properties. J. Soils Sediment. 2014;14(8):1407–1416. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yusuf M. Synthetic dyes: a threat to the environment and water ecosystem. Text. Cloth. 2019:11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zema D.A., Lucas-Borja M.E., Andiloro S., Tamburino V., Zimbone S.M. Short term effects of olive mill wastewater application on the hydrological and physico-chemical properties of a loamy soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2019;221:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2019.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeng F., Ali S., Zhang H., Ouyang Y., Qiu B., Wu F., Zhang G. The influence of pH and organic matter content in paddy soil on heavy metal availability and their uptake by rice plants. Environ. Pollut. 2011;159(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zheng N., Wang Q.C., Zheng D.M. Health risk of Hg, Pb, Cd, Zn and Cu to the inhabitants around Huludao zinc plant in China via consumption of vegetables. Sci. Total Environ. 2007;383:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou J., Liu H., Du B., Shang L., Yang J., Wang Y. Influence of soil mercury concentration and fraction on bioaccumulation process of inorganic mercury and methylmercury in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015;22:6144–6154. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3823-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zuo S., Dai S., Li Y., Tang J., Ren Y. Analysis of heavy metal sources in the soil of riverbanks across an urbanization gradient. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018;15(10):2175. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.