Abstract

Background

Prioritisation of clinical trials ensures that the research conducted meets the needs of stakeholders, makes the best use of resources and avoids duplication. The aim of this review was to identify and critically appraise approaches to research prioritisation applicable to clinical trials, to inform best practice guidelines for clinical trial networks and funders.

Methods

A scoping review of English-language published literature and research organisation websites (January 2000 to January 2020) was undertaken to identify primary studies, approaches and criteria for research prioritisation. Data were extracted and tabulated, and a narrative synthesis was employed.

Results

Seventy-eight primary studies and 18 websites were included. The majority of research prioritisation occurred in oncology and neurology disciplines. The main reasons for prioritisation were to address a knowledge gap (51 of 78 studies [65%]) and to define patient-important topics (28 studies, [35%]). In addition, research organisations prioritised in order to support their institution’s mission, invest strategically, and identify best return on investment. Fifty-seven of 78 (73%) studies used interpretative prioritisation approaches (including Delphi surveys, James Lind Alliance and consensus workshops); six studies used quantitative approaches (8%) such as prospective payback or value of information (VOI) analyses; and 14 studies used blended approaches (18%) such as nominal group technique and Child Health Nutritional Research Initiative. Main criteria for prioritisation included relevance, appropriateness, significance, feasibility and cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion

Current research prioritisation approaches for groups conducting and funding clinical trials are largely interpretative. There is an opportunity to improve the transparency of prioritisation through the inclusion of quantitative approaches.

Keywords: Cost-effectiveness, Clinical trial networks, Prioritisation, Review

Introduction

Clinical trials networks (CTNs) conduct investigator-initiated research and public good trials, largely funded by charities, universities and governments. Examples of CTNs in Australia include the Australian Kidney Trials Network (AKTN https://aktn.org.au/), the Australia and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists clinical trials network (ANZCA https://www.anzca.edu.au/research/anzca-clinical-trials-network) and the Cooperative Trials Group for Neuro-Oncology (COGNO https://www.cogno.org.au/default.aspx). Example CTNs in Europe include the European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care (ESAIC https://www.esaic.org/research/clinical-trial-network/) and in the USA include the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN https://www.hptn.org/). However, with limited available resources including trained research personnel, trial participants and funds, decisions need to be made about which trials are a priority. The desired result of successful prioritisation is funded trials that generate important information, help inform clinical and policy decision-making and improve health outcomes. In reality, research prioritisation is not easy, and many organisations wrestle with competing criteria and the multiple interests of stakeholder groups.

Three main approaches to prioritisation have emerged in health and medicine research, namely interpretive, quantitative and blended methods. Interpretive approaches utilise consensus views of informed participants and include James Lind Alliance (JLA) and Delphi surveys [1, 2]. These approaches can reflect emerging patterns in the future and engage consumers; however, they do not provide methodology for identifying participants, often lack criteria transparency and have the potential for investigators and facilitators to bias opinions. Quantitative approaches utilise epidemiological, clinical or economic data. Examples include burden of disease, prospective payback and value of information (VOI) analyses [3, 4]. These approaches provide an objective assessment of value for money; however, they do not consider other criteria such as equity and broad stakeholder’s involvement; furthermore, they can be technically demanding. Blended approaches utilise and combine both interpretive and quantitative assessments and include the Child Health Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI) and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA [5, 6].

The aim of this scoping review was to identify approaches for priority setting in health and medical research useful to clinical trial networks (CTNs) in Australia and internationally and research funders. Specifically to answer the following research questions: what models, approaches or methods are used by CTNs to prioritise clinical trials; how have these models, approaches or methods been developed and validated; and what is the best practice for prioritising clinical trials? The findings will then be used to develop best practice guidance for CTNs and research funders.

Methods

A scoping review of published literature and working documents, as well as websites from research funding organisations and CTNs, was undertaken to identify research prioritisation tools and criteria. Digital databases including Ovid MEDLINE, Embase and the WHO library database (WHOLIS) were searched for publications about guidelines for prioritising research questions relevant to CTNs. Search terms included ([prioritization OR prioritisation OR setting priorities OR priority setting OR research priority*] AND [clinical trials OR clinical trial networks OR clinical trial group]). The search was limited to studies in English published from year 2000 onwards. The search was updated on 30 January 2020.

Titles and abstracts were screened, and eligible studies were selected by a single reviewer (VBN) for the following inclusion criteria: original studies, systematic reviews, guidelines, recommendations, and tools for research prioritisation. Both qualitative and quantitative methods of prioritisation were accepted. Studies not relevant to CTNs, duplicate publications, guidelines written from the perspective of funders, opinion articles, letters to editors and abstracts only were excluded. A manual search of key references cited in the retrieved papers and reports was also undertaken to identify additional publications not encountered by the electronic searches. A second reviewer (RLM) was consulted when in doubt regarding study selection, and any discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer (MC).

A second search of key Australian and international CTNs/clinical disciplines/clinical specialties websites was then undertaken. Organisations were selected by the author team as likely to provide guidance on prioritisation and selection of clinical trials, and websites were searched by two authors (VBN, AB). Searched websites are listed in the Appendix. Searching included exploration of the website menu structure for relevant documents and searching within the sites using the terms “clinical trials”, “priorities”, “prioritisation” or “prioritization” (depending on the nationality of the website).

The following types of documents were selected for inclusion: guidance on prioritisation; case studies or examples of prioritisation exercises that reported the methods used; guidance on criteria for the assessment, selection or prioritization of clinical trials (e.g. for funding purposes). Documents that did not constitute current guidance or were superseded by later versions of current guidance (e.g. prioritisation processes to inform past priorities or strategic plans or discussion documents that appeared to be older than current guidance), were excluded. Documents with URLs that were no longer accessible in January 2020 were also excluded.

Data from studies and websites were extracted and tabulated into an Excel file according to a predefined codebook. Data extraction variables comprised author name, author group (e.g. CTN, funder), clinical discipline, country, year of publication, participants or stakeholders in the prioritisation process (e.g. health professionals, researchers, policy/decision makers, funders, patients, carers/consumers), intended audience (e.g. government/policymakers, clinicians, researchers, funders, the public), brief reason for prioritisation (e.g. knowledge gap, important to patients, return on investment, feasibility of methodology), type of research (e.g. trials), research prioritisation tools (e.g. Delphi, CHNRI, JLA, payback, MCDA, forced ranking, workshop/consensus meeting, other), prioritisation method (e.g. quantitative scoring, nominal group technique, weighted scores, monetary, other), research prioritisation criteria (e.g. relevance, appropriateness, significance, feasibility, cost-effectiveness [7]) and the URLs (for websites). Data from published articles and websites were summarised and tabulated separately. Critical appraisals of included studies, guidance documents or websites were not undertaken. Reporting of this scoping review was consistent with items in the PRISMA-ScR checklist [8].

Results

Literature search

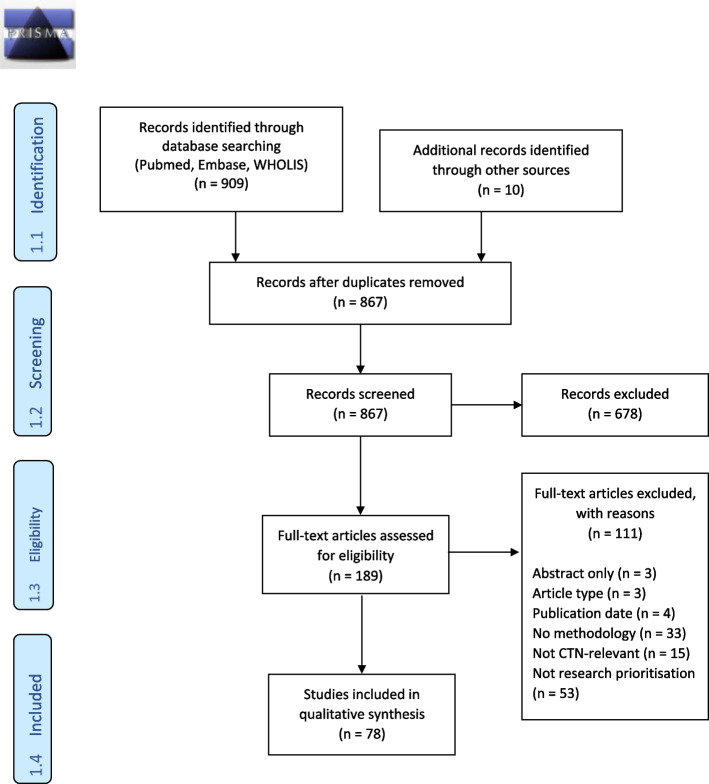

The results of the literature search and study selection process are depicted in Fig. 1. A table of the seventy-eight primary studies included in this review is presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 diagram

Table 1.

Included studies

| Citation | Author group (CTN, funder) | Clinical discipline | Participants/Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||

| Folayan, Haire [9] | Institute of Public Health, Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria | Infectious diseases (outbreaks) | Bioethicists, social scientists, ethics committee members, community members |

| Australia and New Zealand | |||

| Middleton, Piccenna [10] | National Trauma Research Institute and Australian and New Zealand Spinal Cord Injury Network (ANZSCIN) Funded by Victorian Transport Accident Commission and ANZSCIN | Spinal cord injury | Clinicians, researchers, advocacy organisations, health system managers, policy makers, funding agencies |

| Sangvatanakul, Hillege [11] | Research institutes, universities, Nursing and Midwifery Australia, National Centre for Clinical Outcomes Research (NaCCOR), National Stroke Foundation… | Stroke | Stroke survivors, carers |

| Sawford, Dhand [12] |

University of Western Sydney, contracted by Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Funded by National Hendra Virus Research Program (Commonwealth of Australia, State of New South Wales, State of Queensland) |

Infectious diseases/ Zoonosis |

Policy developers and implementers in key government agencies in all states and territories Known experts engaged in a range of Hendra virus-related activities Research leaders in charge of National Hendra Virus Research Program funded projects Members of the Intergovernmental Hendra Virus Taskforce Public health leaders in Hendra virus-affected states |

| Thom, Keijzers [13] |

Australian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) Clinical Trials Network |

Emergency medicine | ACEM fellows, trainees, senior national and international researchers |

| Tong, Crowe [14] | Funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), University of Sydney, Kidney Health Australia | Nephrology (chronic kidney disease (CKD)) | Patients with CKD (CKD stages 1- 5, 5D, or 5T), family caregivers, or health professionals with experience in CKD (nephrologists, surgeons, nurses, allied health professionals, and researchers) |

| Taylor and Green [15] | Australia & New Zealand Musculoskeletal Clinical Trials Network (ANZMUSC) | Rehabilitation | Health professionals from various disciplines, consumers of healthcare services, funders of research and healthcare services |

| North America – Canada | |||

| Barnieh, Jun [16] | University of Calgary | Nephrology (dialysis) | Patients, caregivers, clinicians |

| Hayes, Bassett-Spiers [17] | The Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation (ONF) International Expert Panel | Spinal cord injury (SCI)/Urology | Experts in physiatry, urology, nursing, microbiology, physiology; person with SCI; executive representatives of ONF |

| Lavigne, Birken [18] |

TARGet Kids! (The Applied Research Group for Kids) primary care research network |

Paediatric preventive care | Parents, clinicians |

| Manns, Hemmelgarn [19] | Kidney Foundation of Canada Funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (grant) | Nephrology (dialysis) | Patients, carers, clinicians |

| Ota, Cron [20] | Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) - investigator-initiated research network | Paediatric rheumatology | Paediatric rheumatology experts across Canada and the USA |

| Restall, Carnochan [21] | Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) | HIV/AIDS | People living with HIV, researchers, service providers, leaders in AIDS service or related organisations and policy makers |

| Schneider, Evaniew [22] | McMaster University Funded by the McMaster Surgical Associates Innovation Grant | Orthopaedic oncology |

Clinician-scientists (interested or participating in a trial, professional societies members), representatives from patient advocacy groups. Representation of geographical, stakeholder and career stage groups. |

| Sivananthan and Chambers [23] | Ontario Research Coalition of Institutes/Centres on Health and Aging (ORC) | Health and aging | Researchers, policy makers, caregivers |

| Wu, Bezjak [24] |

National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) Clinical Trials Group |

Oncology | Researchers, radiation oncologists Opinion leaders, researchers, methodologists |

| North America – USA | |||

| Al-Khatib, Gierisch [25] |

Duke University Evidence Synthesis Group Funded by the Patient- Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) |

Cardiovascular | Clinical experts, researchers, funding agencies, healthcare decision-makers, policymakers, consumer and patient advocacy groups |

| Ardoin, Daly [26] |

Lupus Foundation of America (LFA) Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) |

Paediatric rheumatology | Paediatric clinicians and investigators in rheumatology, nephrology and dermatology |

| Bennette, Veenstra [27] |

Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) – Clinical Trial Cooperative Group Funded by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) |

Oncology | Members of SWOG, including clinical trialists, clinicians, statisticians, and patient advocates and/or members who have a vested interest in the outcomes of this work |

| Bousvaros, Sylvester [28] | Challenges in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Study Groups | Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Investigators with expertise in paediatric IBD: paediatricians, internists, basic scientists, clinical investigators, and members of the administrative staff and board of the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America |

| Carlson, Kim [29] |

Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) Funded by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) |

Oncology | SWOG |

| Duong, Schempp [30] | United States Army/ TriService Nursing Research Program (TSNRP) | Military nursing | TSNRP director, TSNRP Advisory Council, military nursing researchers, clinical leaders |

| Esmail, Roth [31] | Center for Comparative Effectiveness Research in Cancer Genomics (CANCERGEN) | Cancer genomics | CANCERGEN External Stakeholder Advisory Group (ESAG): professional patient/consumer advocates, payers, clinicians, policymakers/regulators, the life sciences and diagnostic industry |

| Fochtman and Hinds [32] |

Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses |

Paediatric oncology | Nurse experts |

| Henkle, Aksamit [33] |

Oregon Health & Science University Supported by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) |

Infectious diseases | Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM) Research Consortium: clinical experts, researchers, patients, caregivers, patient advocates |

| Henkle, Aksamit [34] | Funded by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) | Pneumology | Clinical research experts, patient advisory panel, representatives from two key patient advocacy organisations |

| Higginbotham [35] | Society of Family Planning | Family planning | Family planning researchers and academics |

| Roach, Abreu [36] |

2015 Sturge-Weber Syndrome Research Workshop Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) |

Sturge-Weber Syndrome (Neurology, Ophthalmology, Dermatology) | Clinical and translational researchers |

| Safdar and Greenberg [37] |

Yale School of Medicine and USF Morsani College of Medicine Funded by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Supported by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) |

Emergency Medicine | Researchers, clinicians, health care providers, patients, representatives of federal agencies, policymakers |

| Saldanha, Dickersin [38] | Johns Hopkins Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Cochrane Eyes and Vision | Ophthalmology | International (21 countries) clinicians managing patients with Dry Eye |

| Thariani, Wong [39] | Center for Comparative Effectiveness Research in Cancer Genomics (CANCERGEN) | Oncology (cancer genomics) | Representatives from patient- advocacy groups, payers, test developers, regulators, policymakers, and community-based oncologists |

| Vickrey, Brott [40] | National Institutes of Health (NIH)/ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) | Stroke | Scientific experts, stroke advocates, stroke association representatives |

| Europe | |||

| Aliberti, Masefield [41] |

European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) European Respiratory Society (ERS) Clinical Research Collaboration Endorsed by ERS |

Pneumology | EMBARC Roadmap Study Group: clinicians, patients, and carers |

| Forsman, Wahlbeck [42] |

ROAdmap for Mental health Research in Europe (ROAMER) Consortium |

Mental health | Experts |

| van der Feltz- Cornelis, van Os [43] |

ROAdmap for MEnatal health Research and well-being in Europe (ROAMER) Funded by the European Commission's 7th Framework Programme |

Mental health | Experts in the field of clinical mental health research: psychiatrists, psychologists, general physicians, occupational physicians |

| Europe – The Netherlands | |||

| de Graaf, Postmus [44] | Department of Epidemiology, University of Groeningen | Diabetes |

Not applicable (theoretical exercise) Expert opinion for ordinal ranking of decision alternatives |

| Europe – United Kingdom | |||

| Aldiss, Fern [45] |

The Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) Funded by the Teenage Cancer Trust, CLIC Sargent, Children with Cancer UK |

Oncology | Young people with current or previous cancer diagnosis, their families, friends, partners, and professionals who work with this population |

| Andronis, Billingham [46] | National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) | Oncology | 2 case studies (research grant proposals for clinical trials) |

| Boney, Bell [47] | National Institute for Academic Anaesthesia (NIAA) Health Services Research Centre | Anaesthesia and perioperative care | Professionals, patients/carers |

| Cox, Arber [48] | UK Oncology Nursing Society | Oncology nursing | Nurses, patients |

| Deane, Flaherty [49] | University of East Anglia and University of Birmingham Funded by Parkinson's UK | Neurology (Parkinson's) | People with Parkinson’s (PwP); carers and former carers; family members and friends; healthcare and social care professionals who work, or have worked, with people living with the condition. Non- clinical researchers and employees of pharmaceutical or medical devices companies were excluded from the survey. |

| Fleurence [50] | York Trials Unit | Methodology (clinical trials)/ osteoporosis and wound care | Not applicable (theoretical exercise) |

| Gadsby, Snow [51] |

University of Warwick Partnership: Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, Insulin Dependent Diabetes Trust, Diabetes Research Network, Diabetes UK, Scottish Diabetes Research Network, UK Database of Uncertainties in the Effects of Treatments, the James Lind Alliance, and NHS Evidence—diabetes Funded by Insulin Dependent Diabetes Trust |

Diabetes | Patients, carers, health professionals |

| Hall, Mohamad [52] |

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), scientific and patient societies Funders: British Tinnitus Association, NIHR, Judi Meadows Memorial Fund |

Neurology - tinnitus | Clinicians, persons with tinnitus, researchers, James Lind Alliance representative, NICE representative Professional bodies, charities, advocators for people with tinnitus, support groups, hospital centres, commercial organizations |

| Hart, Lomer [53] | British Society of Gastroenterology, Funded by Crohn's and Colitis UK | Gastroenterology | Healthcare professionals (nurses, gastroenterologists, dietitians), patients, carers |

| Heazell, Whitworth [54] | Tommy's, Maternal and Fetal Health Research Centre University of Manchester | Obstetrics | Representatives of professional and parents' organisations (direct/indirect experience with stillbirth) |

| Howell, Pandit [55] | National Institute for Academic Anaesthesia (NIAA) Research Council | Anaesthesia and perioperative medicine | Fellows of the Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCA), members of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI), lay representatives (Patient Liaison Group of the RCA) |

| Ingram, Abbott [56] | Funded by the UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network | Dermatology | Patients, carers, clinicians |

| Kelly, Lafortune [57] | Alzheimer's Society | Neurology / dementia | People with dementia, carers, relatives, health and care professionals |

| Knight, Metcalfe [58] | Funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) | Nephrology (transplant) | Patients, carers, donors, clinicians, nurses, scientists |

| Macbeth, Tomlinson [59] | British Hair and Nail Society Funded by Alopecia UK | Dermatology | People with hair loss, carers, relatives, healthcare professionals, scientific societies' representatives |

| McKenna, Griffin [60] |

University of York Supported by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) |

Traumatology (brain injury) | Not applicable (case study) |

| Morris, Simkiss [61] | British Academy of Childhood Disability | Childhood neurodisability | Young people with disabilities, parent carers, clinicians, charity representatives |

| Owens, Ley [62] | Devon Partnership National Health Service (NHS) Trust | Mental health |

Mental health service users Informal carers Mental health practitioners Service managers |

| Perry, Wright [63] |

British Society for Children's Orthopaedic Surgery (BSCOS) |

Paediatric Orthopaedics |

Surgeons - members of BSCOS |

| Pollock, St George [64] |

Nursing Midwifery and Allied Health Professions (NMAHP) Research Unit Funded by the Scottish Government |

Stroke | Stroke survivors, caregivers, health professionals |

| Rangan, Upadhaya [65] |

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Funded by the British Elbow and Shoulder Society, British Orthopaedic Association |

Orthopaedics | Patients, carers, medical doctors, nurses, allied health professionals, general practitioners |

| Rowat, Pollock [66] | Scottish Stroke Nurses Forum (SSNF) | Stroke (nursing) | Stroke nurses (registered, unregistered, students) members of the SSNF |

| Rowe, Wormald [67] |

Fight for Sight, College of Optometrists, Royal College of Ophthalmologists Funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) |

Ophthalmology | Patients, relatives, carers, eye health professionals |

| Shepherd, Wood [68] | South East Wales Trials Unit, Centre for Trials Research, Cardiff University | Aged care | Care home staff (nursing and residential care) |

| Stephens, Whiting [69] | Institute of Clinical Trials & Methodology | Oncology (mesothelioma) | Patients, carers, health professionals, support organisations |

| van Middendorp, Allison [70] | Funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) – Oxford Biomedical Research Group | Spinal cord injury | Consumer organisations, healthcare professional societies and caregivers |

| Wan, Beverley-Stevenson [71] | University of Manchester Funded by NIHR | Oncology | Patients, carers, healthcare professionals |

| Willett, Gray [72] | Funded by AO UK Research Group | Orthopaedic trauma | AO UK faculty members: orthopaedic surgeons and operating room nurses |

| India | |||

| Arora, Mohapatra [73] |

Inclen Trust Intl Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) |

Maternal, newborn, child health and nutrition |

Researchers, professionals, public health functionaries, policy makers, communities and their leadership, civil society, donor agencies and industries Exclusively Indian nationals |

| Ravindran and Seshadri [74] | Institute for Medical Sciences & Technology, Trivandrum Part of Closing the Gap project Supported by International Development Research Centre, Canada | Health equity | Researchers (public health - health systems researchers, epidemiologists, social science, anthropology), practitioners: policymakers, programme managers, advocates, activists |

| International | |||

| Allotey, Matei [75] |

Queen Mary University of London Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization (WHO) |

Maternal and perinatal health |

Healthcare providers, academics, lay representatives, public health specialists, policy makers. Clinicians (80%, 127/159), made up of obstetricians (68%, 86/127); neonatologists (24%, 30/127); nurses/midwives (7%, 9/127) and general practitioners (2%, 2/127). Researchers, epidemiologists, consumers, policy makers and representatives of non- governmental organizations (NGOs) and funding bodies |

| Bahl, Martines [76] | Department of Child and Adolescent Health & Development, World Health Organization (WHO) | Newborn health | Investors, policymakers, technical experts, other stakeholders |

| Brown, Hess [77] | University of California Davis Funded by the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI) | Paediatric nutrition | Leading experts in zinc research |

| Brundin, Barkerb [78] | Linked Clinical Trials International Committee | Neurology - Parkinson's | International committee of experts Representatives of key funding bodies (as observers) |

| Foster, Dziedzic [79] |

Arthritis Research Campaign National Primary Care Centre, Keele University Clinical Trials Thinktank |

Musculoskeletal disorders |

Researchers, patient representatives Round 2 - researchers, practitioners, educators, managers |

| Prescott, Iwashyna [80] | International Sepsis Forum | Infectious diseases | Healthcare professionals, researchers, patient representatives |

| Robinson, Lorenc [81] | British Acupuncture Council | Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) | TCM acupuncturists |

| Rowbotham, Smith [82] | University of Nottingham | Pneumology (cystic fibrosis) | Patients and clinical community |

| Ruhl, Sadreameli [83] | The American Thoracic Society | Pneumology (sickle cell lung disease) | Multidisciplinary - paediatric and adult haematologists, pneumologists, emergency medicine physicians, patient advocate, librarian |

| Viergever, Olifson [84] | Bruyere Evidence-Based Guidelines Symposium | Clinical pharmacology (deprescribing) | Researchers, educators, clinicians, patient advocates, guideline developers, policy makers, other stakeholders |

| Viergever, Olifson [85] | World Health Organization (WHO) | Health research | Expert staff in WHO and selection of international research organisations experienced in health research priority setting |

| Yu, Li [86] |

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health |

Ophthalmology | Clinicians |

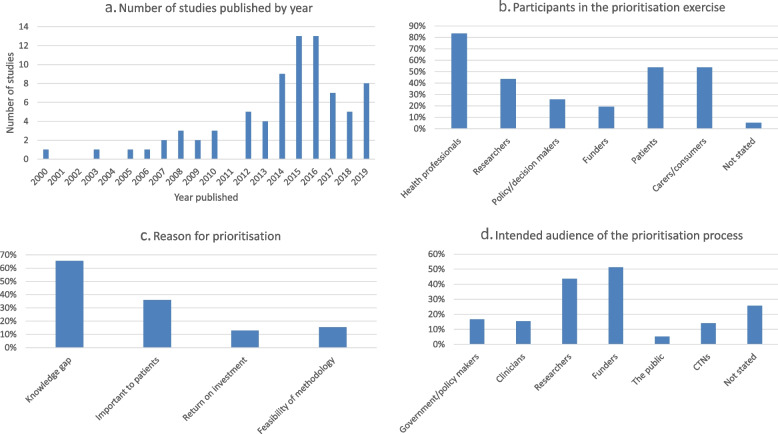

Most research prioritisation exercises were conducted either in Europe (n = 32; 41%) or North America (n = 25; 32%); six prioritisation studies (8%) originated in Australia and New Zealand. Two studies were conducted in South Asia (India; 3%), one in South-East Asia (1%), one in Africa (1%) and 11 studies were international (14%). Included studies were published between 2000 and 2019 (see Fig. 2a). Clinical specialties most frequently involved in research prioritisation were oncology (n = 11 studies; 14%), neurology (n = 11; 14%), paediatrics (n = 8; 10%), maternal and child health (n = 4; 5%), infectious diseases and HIV/AIDS (n = 5; 6%), nephrology (n = 4; 5%), respiratory medicine (n = 4; 5%), mental health (n = 3; 4%) and ophthalmology (n = 3; 4%).

Fig. 2.

Prioritisation study numbers, participants, reason and intended. a Number of studies published by year. b Participants in the prioritisation exercise. c Reason for prioritisation. d Intended audience of the prioritisation process

The stakeholders most frequently involved in the prioritisation process were health professionals (n = 65 studies; 83.3%), patients and carers/consumers (each n = 42 studies; 53.8%), researchers (n = 34 studies, 44%), policy or decision makers (n = 20 studies, 26%), and funders (n = 15 studies, 19%; see Fig. 2b). Stakeholders were not stated in four studies (5%).

The reasons for conducting the research prioritisation exercise included a knowledge gap in 51 studies (65%), ascertaining what was important to patients in 28 studies (36%), assessing the feasibility of a particular prioritisation methodology in 12 studies (15%) and estimating a return on investment in 10 studies (13%; see Fig. 2c; Table 2).

Table 2.

Prioritisation methodologies

| Citation | Type of research | Reason for prioritisation | Tool, model or approach used for prioritisation | Prioritisation method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge gap | Important to patients | Return on investment | Feasibility of methodology | ||||

| Quantitative Approach | |||||||

| Andronis 2016 [46] | Clinical trials | Y | Payback/VOI | Monetary | |||

| Bennette 2016 [27] | Clinical trials | Y | VOI | Monetary | |||

| Carlson 2018 [29] | Clinical trials | Y | VOI | Monetary | |||

| Fleurence 2007 [50] | Trials | Y | Payback/VOI | Monetary | |||

| McKenna 2016 [60] | Clinical trials | Y | VOI | Monetary | |||

| Robinson 2012 [81] | Clinical trials | Y | Other | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Interpretative Approach | |||||||

| Aldiss 2019 [45] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Not stated | |||

| Aliberti 2016 [41] |

Clinical trials Translational research Collaborative working |

Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Al-Khatib 2015 [25] | Systematic reviews, trials, observational studies (horizon scanning) | Y | Forced ranking | Forced ranking | |||

| Barnieh 2015 [16] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Nominal group technique | |||

| Boney 2015 [47] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Weighted scores | ||

| Bousvaros 2006 [28] | Not stated | Y | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Not stated | ||

| Brundin 2013 [78] | Clinical trials | Other | Not stated | ||||

| Comi 2016 [87] | Clinical trials | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Not stated | |||

| Cox 2017 [48] | Not stated | Y | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Deane 2014 [49] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Duong 2005 [30] | Not stated | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Not stated | |||

| Esmail 2013 [31] | Comparative effectiveness research | Y | Delphi | AHRQ criteria | |||

| Fochtman 2000 [32] | Not stated | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Folayan 2018 [9] | Clinical trials | Y | Delphi | Not stated | |||

| Forsman 2015 [42] | Not stated | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Foster 2009 [79] | Clinical trials | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring/Nominal group technique | |||

| Gadsby 2012 [51] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Hall 2013 [52] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Weighted scores | ||

| Hart 2017 [53] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Hayes 2007 [17] | Late-stage animal or early-stage human clinical trials | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Heazell 2015 [54] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Henkle 2016 [33] | Not stated | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Not stated | |||

| Henkle 2018 [34] | Clinical trials | Y | Y | Other | Not stated | ||

| Howell 2012 [55] | Not stated | Y | Other | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Ingram 2014 [56] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring/ Nominal group technique | ||

| Kelly 2015 [57] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring/ Nominal group technique | |||

| Knight 2016 [58] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring/ Nominal group technique | ||

| Lavigne 2017 [18] | Not stated | Y | Y | Other | Quantitative scoring/ Nominal group technique | ||

| Macbeth 2017 [59] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring/Nominal group technique | ||

| Manns 2014 [19] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | NGT | ||

| Middleton 2015 [10] | Trials | Y | Y | Other | Not stated | ||

| Morris 2015 [61] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring/Nominal group technique | |||

| Ota 2008 [20] | Clinical trials | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Owens 2008 [62] | Not stated | Y | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Perry 2018 [63] |

Clinical trials (clinical effectiveness) |

Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Pollock 2014 [64] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Prescott 2019 [80] | Clinical trials, cohorts | Y | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Rangan 2016 [65] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Red-amber-green light | |||

| Ravindran 2018 [74] | Not stated | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Not stated | |||

| Restall 2016 [21] | Not stated | Y | Other | Dotmocracy | |||

| Rowat 2016 [66] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring/ Nominal group technique | ||

| Rowbotham 2019 [82] | Clinical trials | Y | JLA | Not stated | |||

| Rowe 2014 [67] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring/ Nominal group technique | ||

| Ruhl 2019 [83] | Randomised controlled trials, Longitudinal studies | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Not stated | |||

| Saldanha 2017 [38] | Clinical research | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Sawford 2014 [12] | Longitudinal cohort study | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Shepherd 2017 [68] | Not stated | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Sivananthan 2013 [23] | Not stated | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Stephens 2015 [69] | Not stated | Y | JLA | Not stated | |||

| Thariani 2012 [39] | Comparative effectiveness research | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Thompson 2019 [84] | Clinical trials, cohorts | Y | Other | None | |||

| van der Feltz-Cornelis 2014 [43] | Clinical research | Y | Other | Quantitative scoring | |||

| van Middendorp 2016 [70] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Vickrey 2013 [40] | Not stated | Y | Delphi | Not stated | |||

| Wan 2016 [71] | Not stated | Y | Y | JLA | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Willett 2010 [72] | RCTs | Y | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Wu 2003 [24] | Clinical trials | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Not stated | |||

| Blended Approach | |||||||

| Allotey 2019 [75] | Clinical trials, IPDM | Y | Other | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Ardoin 2019 [26] | Clinical trials | Y | Other | Not stated | |||

| Arora 2017 [73] | Not stated | Y | Y | Y | CHNRI | Weighted scores | |

| Bahl 2009 [76] | Funding agencies and investigators | Y | Y | CHNRI | Weighted scores | ||

| Brown 2008 [77] | Not stated | Y | CHNRI | Quantitative scoring | |||

| de Graaf 2015 [44] |

Translational biomedical research |

Y | MCDA | Quantitative scoring | |||

|

Higginbotham 2015 [35] |

Not stated | Y | CHNRI | Weighted scores | |||

| Safdar 2014 [37] | Not stated | Y |

Workshop/consensus meeting |

Quantitative scoring | |||

|

Sangvatanakul 2010 [11] |

Not stated | Y | Y | Other/Delphi | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Schneider 2016 [22] | International clinical trials | Y | Y | Delphi | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Taylor 2019 [15] | Review topics | Y | MCDA | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Thom 2014 [13] | Clinical research | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Weighted scores | |||

| Tong 2015 [14] | Not stated | Y | Y | Workshop/consensus meeting | Quantitative scoring | ||

| Yu 2015 [86] |

Comparative effectiveness study Reviews RCTs |

Y | Other | Quantitative scoring | |||

| Other | |||||||

| Viergever 2010 [85] | Not stated | Y | Other | Not stated | |||

AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, CHNRI Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative, IPDM Individual patient data meta-analyses, JLA James Lind Alliance, MCDA Multicriteria decision analysis, RCT Randomised controlled trial

The intended audience for the outcomes of the prioritisation exercise were the funders in 40 studies (51%), researchers in 34 studies (44%), government or policymakers in 13 studies (17%), clinicians in 12 studies (15%), CTNs in 11 studies (14%), the general public in 4 studies (5.1%) and not stated in 20 studies (26%; see Fig. 2d).

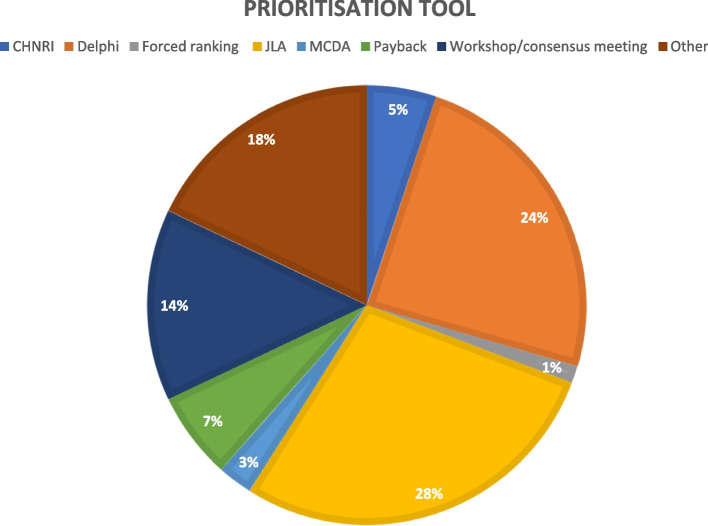

A table of the prioritisation approaches is presented in Table 2. Fifty-seven studies used interpretative prioritisation approaches (73%), 14 studies used blended approaches (18%) and six studies used quantitative approaches (8%). Twenty-two studies used the JLA prioritisation tool or a modification thereof (28%), 19 studies used the Delphi methodology (24%) and 11 studies used a workshop or consensus meeting to establish their priorities (18%; see Fig. 3; Table 2). The “Payback” category included quantitative methods such as prospective payback of research (PPoR), expected value of information (EVI), return on investment (ROI) and the “Other” category included methods such as online surveys/questionnaires, focus groups, World Café and mixed methods. Forty-five studies (58%) employed quantitative scoring as a prioritisation method, frequently in the form of nominal group technique (n = 11 studies; 14%). Six studies used weighted scores (8%) and five studies used monetary value (6%). One study each used Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) criteria, Dotmocracy, forced ranking, red-amber-green light and no prioritisation (1%).

Fig. 3.

Prioritisation tools used. CHNRI, Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative; JLA, James Lind Alliance; MCDA, Multiple-criteria Decision Analysis

Over two-thirds of the identified studies (n=53, 68%) did not describe any formal prioritisation criteria. In those that did describe prioritisation criteria, multiple criteria were mentioned. Relevance (i.e. why should we do it? including the burden of disease, equity, and knowledge gaps) was cited in 14 of the 78 included studies (18%). Seven studies (9%) cited criteria related to appropriateness (i.e. should we do it? including scientific rigour and suitability to answer the research question); 17 studies (22%) considered criteria related to significance of research outcomes (i.e. what will we get out of it? including impact, innovation, capacity building); 12 studies (15%) cited feasibility among their prioritisation criteria (i.e. can we do it? including team quality and research environment). Cost-effectiveness was considered by fifteen studies (19%). Five studies cited other prioritisation criteria (6%).

Organisational websites

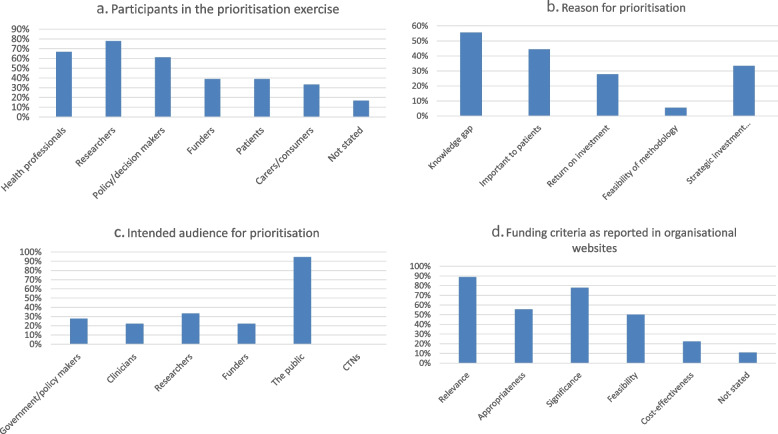

Thirty-nine websites of research funding organisations and CTNs were reviewed (Appendix), and 18 were found to contain research prioritisation information: one from Australia (6%), two from New Zealand (11%), one from Ireland (6%), eight from Canada (44%) and six from the USA (33%; see Table 3). A table of the clinical disciplines involved is depicted listed in Table 3. The stakeholders most frequently involved in priority setting were researchers (n = 14 websites; 78%) followed by health professionals (n = 12 websites; 67%) and policy/decision makers (n = 11 websites; 61%; see Fig. 4a). Funders and patients were mentioned in seven processes each (39%) and carers/consumers were mentioned six times (33%). Participants or stakeholders were not stated in three occasions (17%; see Fig. 4a).

Table 3.

Websites searched

| Citation | Country | Author group (CTN, funder) | Clinical discipline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Framework for Identification and Prioritisation of Targeted Calls for Research | Australia | NHMRC | Health and Medical Research |

| 2 | National Science Challenge description | New Zealand | MBIE | All |

| 3 | New Zealand Health Research Prioritisation Framework | New Zealand | HRC | All |

| 4 | Cross-department priorities | Ireland | Research Prioritisation Project Steering Group | All |

| 5 | SPOR Patient engagement framework | Canada | CIHR | All |

| 6 | Institute for Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis | Canada | IMHA | Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis |

| 7 | IMHA strategic plan 2014-2018 | Canada | IMHA | Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis |

| 8 | IMHA Priority setting - 2018-2020 National Listening tour | Canada | IMHA | Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis |

| 9 | IMHA fibromyalgia case study | Canada | IMHA | Fibromyalgia |

| 10 | Institute for Circulatory and Respiratory Health - ICRH strategic plan 2020 | Canada | ICRH | Circulatory and Respiratory Health |

| 11 | Institute for Population and Public Health – IPPH listening tour 2016 | Canada | IPPH | All |

| 12 | Institute for Population and Public Health – strategic plan 2009-2014 | Canada | IPPH | All |

| 13 | PCORI Methodology report | US | PCORI | All |

| 14 | PCORI-Generation and Prioritization of Topics for Funding Announcements | US | PCORI | All |

| 15 | NIH Strategic plan 2016-2020 | US | NIH | All |

| 16 | NIMH Strategic plan 2020 | US | NIMH | Mental Health |

| 17 | NCBI: Priorities in Health 2006 | US |

The World Bank, WHO, Fogarty International Center NIH |

All |

| 18 | NHLBI priority-setting process | US | NHLBI | All |

CIHR Canadian Institutes of Health Research, HRC Health Research Council of New Zealand, CTN Clinical trials network, ICRH Institute for Circulatory and Respiratory Health, IMHA Institute for Musculoskeletal Health and Arthritis, IPPH Institute for Population and Public Health, MBIE Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, NCBI National Center for Biotechnology Information, NHLBI National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NHMRC National Health and Medical Research Council, NIH National Institutes of Health, NIHR National Institute for Health Research, NIMH National Institute of Mental Health, PCORI Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, SPOR Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research, WHO World Health Organization

Fig. 4.

Research prioritisation participants, reasons, intended audience and funding criteria from websites of research funders and clinical trial networks. a Participants in the prioritisation exercise. b Reason for prioritisation. c Intended audience for prioritisation. d Funding criteria as reported in organisational websites

A “knowledge gap” was the reason for developing a prioritisation guideline among 10 websites (56%), followed by “wanting to know what was important to patients” (n = 8 websites; 44%). Six organisations mentioned the reason for the priority-setting exercise was to support their vision and mission or to invest strategically and in a balanced way (33%) and five organisations wanted to find the best return on investment (32%; see Fig. 4b). Feasibility of the methodologies used was mentioned once (6%).

The intended audience was in all but one case the general public (n = 17 websites; 94%), followed by the researchers (n = 6 websites; 33%), the government and policymakers (n = 5 websites; 28%) and clinicians or funders (n = 4 websites each; 22%; see Fig. 4c).

As for the prioritisation tools used, three organisations used workshop/consensus meeting (17%), one used the JLA tool, one used payback (VOI) and one used MCDA (6%). Five organisations used other tools (surveys, working groups; 28%) and seven did not describe the tool used (39%). In general, few details were provided in organisational websites to further describe the prioritisation approaches undertaken.

The prioritisation criteria included relevance on 16 occasions (89%), appropriateness on 10 occasions (56%), significance on 14 occasions (78%), feasibility on 9 occasions (50%) and cost-effectiveness on 4 occasions (22%). Two websites did not state any prioritisation criteria (11%; see Fig. 4d).

Discussion

This extensive scoping review summarises findings from international agencies about current methods and approaches to prioritisation of clinical trials undertaken by CTNs and research funders. The main reasons for prioritisation were to address a knowledge gap in clinical decision making, and to define patient-important topics. More than two thirds used an interpretive approach (e.g. James Lind Alliance); a small proportion used a quantitative approach (e.g. prospective payback); and one fifth used a blended approach combining qualitative and quantitative methods (e.g. CHNRI). The most common criteria for prioritisation were significance, relevance and cost-effectiveness.

The rationale for prioritisation of trials on the basis of generating new knowledge to improve clinical decision-making is not surprising, as efficacy and effectiveness trials are designed to answer important questions in patient management [27, 50, 88]. What was less clear, however, was how these trials all with “good” questions were then ranked in order of priority. Consensus-based methods that use an interpretative approach are appealing because of their broad stakeholder engagement; however, the trade-offs between criteria, such as significance versus feasibility, and the subsequent processes for overall ranking of trials are not transparent [89, 90]. This is where blended approaches that include a quantitative component that facilitates objective scoring of trial proposals can assist.

The infrequent use of pure quantitative approaches for prioritisation of trials including burden of disease or value for money is likely due to few standardised methods to view competing claims side by side, or knowing how to weight such criteria. It may also be related to low technical knowledge or expertise within the trials community to generate this information. For example, many clinical trial funders suggest the relevance of the problem to be stated, which is typically reported as burden of disease, incidence or prevalence. When different metrics are used across trial proposals they become difficult to compare, which may lead to grant reviewers considering whether the criterion is satisfied (i.e. is there a substantial burden, [yes/no]), rather than comparing those burdens. Sometimes, the burden is presented as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and sometimes, the disease burden is monetized to provide an overview of health system or societal costs. While this provides a common metric on which trial applications can be compared, these estimates are limited to quantifying the current situation; they do not provide insight into the value of the proposed trial in reducing that burden (i.e. the significance), otherwise known as the impact or net benefit.

Value of information (VOI) analysis has emerged as a new framework for quantifying the net benefit of proposed randomised trials. VOI uses a cost-effectiveness modelling approach and takes into account the cost of running the trial and the value of the new trial information to reduce uncertainty with the current clinical decision. The benefit of the health outcomes for the better decision (e.g. using drug A over drug B) is then multiplied across the population at risk using assumptions about post-trial implementation. A VOI analysis can be undertaken for most randomised trials enabling studies in a given portfolio to be ranked from most to least value. This requires capacity building in the health economics and statistics workforce. Efficient methods to calculate VOI are currently underway [91, 92].

An encouraging sign from this review was the emphasis placed on patient-important topics through consumer-generated questions and topic ranking, from both published literature and organisational websites. This ensures that not only are questions important and of interest to clinicians or trialists, but that they also address issues, problems or concerns that are bothering those with the disease and/or undergoing specific treatments. This is especially important for government and non-profit charity funders where the funding for research originates from the general public (i.e. tax-payers), or donors.

The strengths of this review include the dual searching of published and unpublished literature, including organisational websites of international clinical trial networks and trial funders. This approach was likely to identify prioritisation processes that were operational, yet had not been formally described in the peer-reviewed literature. It is a strength that we were able to locate and extract research prioritisation approaches and methods as well as the prioritisation criteria used, as this provides sufficient detail for clinical trials networks and funders to replicate. Our scoping review was limited to studies and websites published in English and therefore may omit relevant studies published in other languages. It was not a systematic review and therefore may not have identified all studies of research prioritisation in the published literature. In addition, we could only tabulate methods where they were clearly described.

Further research consulting consumers, researchers and policy-makers is now needed to develop specific criteria weights for clinical trials networks and coordinating centre members of the Australian Clinical Trials Alliance (ACTA), of international CTNs and funders of clinical trials. Development of tools to aid clinicians and researchers in using quantitative approaches is also needed. Following implementation of a formalised prioritisation process, clinical trials networks and funders will need to then evaluate the process and assess whether the “best” trials are subsequently funded and deliver on their expected benefits [93].

Conclusion

Research prioritisation approaches for groups conducting and funding clinical trials are predominantly interpretative. Given the strengths of a blended approach to prioritisation, there is an opportunity to improve the transparency of process through the inclusion of quantitative techniques.

Acknowledgements

We thank ACTA’s Research Prioritisation Reference Group.

Abbreviations

- ACTA

Australian Clinical Trials Alliance

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- AKTN

Australasian Kidney Trials Network

- ANZCA

Australian and New Zealand College for Anaesthetists

- ANZIC-RC

Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre

- ANZICS

Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society

- CHNRI

Child Health Nutrition Research Initiative

- CTN

Clinical Trial Network

- DALY

Disability-adjusted life years

- EVI

Expected Value of Information

- JLA

James Lind Alliance

- MCDA

Multi-criteria Decision Analysis

- NHMRC

National Health and Medical Research Council

- PPoR

Prospective Payback of Research

- ROI

Return on investment

- VOI

Value of information

- WHOLIS

World Health Organization Library Database

Appendix

Key Australian and international clinical trials networks (CTNs) /clinical disciplines/ clinical specialties and Funders’ websites

Clinical trials network websites

|

▪ Australia & New Zealand Musculoskeletal (ANZMUSC) Clinical Trials Network ▪ Australasian College for Emergency Medicine (ACEM) Clinical Trials Group ▪ Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG) ▪ Australasian Lung Cancer Trials Group (ALTG) ▪ Australasian Radiopharmaceutical Trials Network (ARTNET) ▪ Australasian Sarcoma Study Group (ASSG) ▪ Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases (ASID) Clinical Research Network ▪ Australasian Stroke Trials Network (ASTN) ▪ Australia & New Zealand Breast Cancer Trials Group (ANZBCTG) ▪ Australia & New Zealand Melanoma Trials Group (ANZMTG) ▪ Australia New Zealand Gynaecological Oncology Group (ANZGOG) ▪ Australian & New Zealand Children’s Haematology/Oncology Group (ANZCHOG) ▪ Australian & New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) Clinical Trials Network ▪ Australian & New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) Clinical Trials Group ▪ Australian & New Zealand Urogenital & Prostate (ANZUP) Cancer Trials Group ▪ Australian Epilepsy Clinical Trials Network (AECTN) ▪ Australian Paediatric Research Network (APRN) ▪ Australian Primary Care Research Network (APCReN) ▪ Cooperative Trials Group for Neuro-Oncology (COGNO) ▪ Multiple Sclerosis Research Australia Clinical Trials Network (MS Australia) ▪ NSW Better Treatments 4 Kids (BT4K) ▪ Paediatric Research in Emergency Departments International Collaborative (PREDICT) ▪ Paediatric Trials Network Australia (PTNA) ▪ Palliative Care Clinical Studies Collaborative (PaCCSC) ▪ Primary Care Collaborative Cancer Clinical Trial Group (PC4) ▪ Psycho-Oncology Co-operative Research Group (PoCoG) ▪ The Australasian Consortium of Centres for Clinical Cognitive Research (AC4R) ▪ The Australasian Kidney Trials Network (AKTN) ▪ The Australasian Sleep Trials Network (ASTN) ▪ The Spinal Cord Injury Network (SSCIS) ▪ The Australian Type 1 Diabetes Clinical Research Network (T1DCRN) ▪ The Interdisciplinary Maternal Perinatal Australasian Collaborative Trials Network (IMPACT) ▪ Therapeutic and Vaccine Research Program, Kirby Institute ▪ Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG) |

Funders’ websites

National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)—Australia

Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF)—Australia

Medical Research Council (MRC)—United Kingdom

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)—United Kingdom

Health Research Board (HRB)—Ireland

Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR)—Canada

National Science Challenges (NSCs)—New Zealand

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)—United States James Lind Alliance Evidence Gap Maps

Health Research Council of New Zealand—New Zealand

National Institutes of Health (NIH)—United States

Department of Business, Enterprise and Innovation—Ireland

Authors’ contributions

All authors conceived the idea. RM wrote the first draft. All authors gave intellectual input into the article and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project received grant funding from the Australian Government. Salary support for RLM was provided through an Australian NHMRC TRIP Fellowship #1150989 and University of Sydney Robinson Fellowship. HT was supported by an NHMRC ECR Fellowship #1121232.

Availability of data and materials

Data generated and analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cowan K, Oliver S. The James Lind Alliance guidebook. Southampton: National Institute for Health Research Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi method. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams A. Calculating the global burden of disease: time for a strategic reappraisal? Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies L, Drummond M, Papanikolaou P. Prioritizing investments in health technology assessment: can we assess potential value for money? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2000;16(1):73–91. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300016172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudan I, Gibson JL, Ameratunga S, Arifeen SE, Bhutta ZA, Black M, et al. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: guidelines for implementation of CHNRI method. Croatian Med J. 2008;49(6):720–733. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.49.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belton V, Stewart T. Multiple criteria decision analysis: an integrated approach. Springer Science & Business Media; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuffaha HWESN, Chambers SK, Scuffham PA. Directing research funds to the right research projects: a review of criteria used by research organisations in Australia in prioritising health research projects for funding. BMJ Open. 2018;8(12):e026207. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MD, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folayan MO, Haire B, Allman D, Yakubu A, Afolabi MO. Research priorities during infectious disease emergencies in West Africa. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3263-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middleton JW, Piccenna L, Lindsay Gruen R, Williams S, Creasey G, Dunlop S, et al. Developing a spinal cord injury research strategy using a structured process of evidence review and stakeholder dialogue. Part III: Outcomes. Spinal Cord. 2015;53(10):729–737. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sangvatanakul P, Hillege S, Lalor E, Levi C, Hill K, Middleton S. Setting stroke research priorities: The consumer perspective. J Vasc Nurs. 2010;28(4):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawford K, Dhand NK, Toribio JA, Taylor MR. The use of a modified Delphi approach to engage stakeholders in zoonotic disease research priority setting. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thom O, Keijzers G, Davies S, Mc DTD, Knott J, Middleton PM. Clinical research priorities in emergency medicine: results of a consensus meeting and development of a weighting method for assessment of clinical research priorities. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26(1):28–33. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong A, Crowe S, Chando S, Cass A, Chadban SJ, Chapman JR, et al. Research priorities in CKD: report of a national workshop conducted in Australia. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(2):212–222. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.02.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor WJ, Green SE. Use of multi-attribute decision-making to inform prioritization of Cochrane review topics relevant to rehabilitation. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2019;55(3):322–330. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.19.05787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnieh L, Jun M, Laupacis A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B. Determining research priorities through partnership with patients: an overview. Semin Dial. 2015;28(2):141–146. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes KC, Bassett-Spiers K, Das R, Ethans KD, Kagan C, Kramer JL, et al. Research priorities for urological care following spinal cord injury: recommendations of an expert panel. Can J Urol. 2007;14(1):3416–3423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavigne M, Birken CS, Maguire JL, Straus S, Laupacis A. Priority setting in paediatric preventive care research. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(8):748–753. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Lillie E, Dip SC, Cyr A, Gladish M, et al. Setting research priorities for patients on or nearing dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(10):1813–1821. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01610214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ota S, Cron RQ, Schanberg LE, O’Neil K, Mellins ED, Fuhlbrigge RC, et al. Research priorities in pediatric rheumatology: The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) consensus. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2008;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Restall GJ, Carnochan TN, Roger KS, Sullivan TM, Etcheverry EJ, Roddy P. Collaborative priority setting for human immunodeficiency virus rehabilitation research: a case report. Can J Occup Ther. 2016;83(1):7–13. doi: 10.1177/0008417415577423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider P, Evaniew N, Rendon JS, McKay P, Randall RL, Turcotte R, et al. Moving forward through consensus: protocol for a modified Delphi approach to determine the top research priorities in the field of orthopaedic oncology. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e011780. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivananthan SN, Chambers LW. A method for identifying research priorities for health systems research on health and aging. Healthc Manage Forum. 2013;26(1):33–6. 10.1016/j.hcmf.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Wu J, Bezjak A, Chow E, Cross P, Genest P, Grant N, et al. A consensus development approach to define national research priorities in bone metastases: proceedings from NCIC CTG workshop. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2003;15(8):496–499. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Khatib SM, Gierisch JM, Crowley MJ, Coeytaux RR, Myers ER, Kendrick A, et al. Future research prioritization: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in older patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1812–1820. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3411-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ardoin SP, Daly RP, Merzoug L, Tse K, Ardalan K, Arkin L, et al. Research priorities in childhood-onset lupus: results of a multidisciplinary prioritization exercise. Pediatr. 2019;17(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12969-019-0327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennette CS, Veenstra DL, Basu A, Baker LH, Ramsey SD, Carlson JJ. Development and evaluation of an approach to using value of information analyses for real-time prioritization decisions within SWOG, a large cancer clinical trials cooperative group. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(5):641–651. doi: 10.1177/0272989X16636847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bousvaros A, Sylvester F, Kugathasan S, Szigethy E, Fiocchi C, Colletti R, et al. Challenges in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(9):885–913. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000228358.25364.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson JJ, Kim DD, Guzauskas GF, Bennette CS, Veenstra DL, Basu A, et al. Integrating value of research into NCI Clinical Trials Cooperative Group research review and prioritization: a pilot study. Cancer Med. 2018;7(9):4251–4260. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duong DN, Schempp C, Barker E, Cupples S, Pierce P, Ryan-Wenger N, et al. Developing military nursing research priorities. Mil Med. 2005;170(5):362–365. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.5.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esmail LC, Roth J, Rangarao S, Carlson JJ, Thariani R, Ramsey SD, et al. Getting our priorities straight: a novel framework for stakeholder-informed prioritization of cancer genomics research. Genet Med. 2013;15(2):115–122. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fochtman D, Hinds PS. Identifying nursing research priorities in a pediatric clinical trials cooperative group: the Pediatric Oncology Group experience. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2000;17(2):83–87. doi: 10.1177/104345420001700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henkle E, Aksamit T, Barker A, Daley CL, Griffith D, Leitman P, et al. Patient-centered research priorities for pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection an NTM research consortium workshop report. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2016;13(9):S379–SS84. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201605-387WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henkle E, Aksamit TR, Daley CL, Griffith DE, O’Donnell AE, Quittner AL, et al. US Patient-Centered Research Priorities and Roadmap for Bronchiectasis. Chest. 2018;154(5):1016–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higginbotham SL. The SFP research priority setting process. Contraception. 2015;92(4):282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roach ES, Abreu N, Acosta M, Ball KL, Berrocal A, Bischoff J, et al. Leveraging a Sturge-Weber gene discovery: an agenda for future research. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;58:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Safdar B, Greenberg MR. Organization, execution and evaluation of the 2014 academic emergency medicine consensus conference on gender-specific research in emergency care - An executive summary. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(12):1307–1317. doi: 10.1111/acem.12530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saldanha IJ, Dickersin K, Hutfless ST, Akpek EK. Gaps in current knowledge and priorities for future research in dry eye. Cornea. 2017;36(12):1584–1591. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thariani R, Wong W, Carlson JJ, Garrison L, Ramsey S, Deverka PA, et al. Prioritization in comparative effectiveness research: the CANCERGEN Experience. Med Care. 2012;50(5):388–393. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182422a3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vickrey BG, Brott TG, Koroshetz WJ. Stroke Research Priorities Meeting Steering C, the National Advisory Neurological D, Stroke C, et al. Research priority setting: a summary of the 2012 NINDS Stroke Planning Meeting Report. Stroke. 2013;44(8):2338–2342. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aliberti S, Masefield S, Polverino E, De Soyza A, Loebinger MR, Menendez R, et al. Research priorities in bronchiectasis: a consensus statement from the EMBARC Clinical Research Collaboration. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):632–647. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01888-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forsman AK, Wahlbeck K, Aaro LE, Alonso J, Barry MM, Brunn M, et al. Research priorities for public mental health in Europe: recommendations of the ROAMER project. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(2):249–254. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Os J, Knappe S, Schumann G, Vieta E, Wittchen HU, et al. Towards Horizon 2020: Challenges and advances for clinical mental health research - Outcome of an expert survey. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treatment. 2014;10:1057–1068. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S59958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Graaf G, Postmus D, Buskens E. Using multicriteria decision analysis to support research priority setting in biomedical translational research projects. BioMed Research Int. 2015;2015:191809. doi: 10.1155/2015/191809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aldiss S, Fern LA, Phillips RS, Callaghan A, Dyker K, Gravestock H, et al. Research priorities for young people with cancer: a UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e028119. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andronis L, Billingham LJ, Bryan S, James ND, Barton PM. A practical application of value of information and prospective payback of research to prioritize evaluative research. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(3):321–334. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15594369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boney O, Bell M, Bell N, Conquest A, Cumbers M, Drake S, et al. Identifying research priorities in anaesthesia and perioperative care: final report of the joint National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia/James Lind Alliance Research Priority Setting Partnership. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e010006. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cox A, Arber A, Gallagher A, MacKenzie M, Ream E. Establishing priorities for oncology nursing research: nurse and patient collaboration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(2):192–203. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.192-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deane KH, Flaherty H, Daley DJ, Pascoe R, Penhale B, Clarke CE, et al. Priority setting partnership to identify the top 10 research priorities for the management of Parkinson’s disease. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006434. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fleurence RL. Setting priorities for research: a practical application of ‘payback’ and expected value of information. Health Econ. 2007;16(12):1345–1357. doi: 10.1002/hec.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gadsby R, Snow R, Daly AC, Crowe S, Matyka K, Hall B, et al. Setting research priorities for type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29(10):1321–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall DA, Mohamad N, Firkins L, Fenton M, Stockdale D. Identifying and prioritizing unmet research questions for people with tinnitus: The James Lind Alliance Tinnitus Priority Setting Partnership. Clin Investig. 2013;3(1):21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hart AL, Lomer M, Verjee A, Kemp K, Faiz O, Daly A, et al. What are the top 10 research questions in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease? A priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;11(2):204–211. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heazell AE, Whitworth MK, Whitcombe J, Glover SW, Bevan C, Brewin J, et al. Research priorities for stillbirth: process overview and results from UK Stillbirth Priority Setting Partnership. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(6):641–647. doi: 10.1002/uog.15738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Howell SJ, Pandit JJ, Rowbotham DJ. Research Council of the National Institute of Academic A. National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia research priority setting exercise. Br J Anaesthesia. 2012;108(1):42–52. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ingram JR, Abbott R, Ghazavi M, Alexandroff AB, McPhee M, Burton T, et al. The Hidradenitis Suppurativa Priority Setting Partnership. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(6):1422–1427. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelly S, Lafortune L, Hart N, Cowan K, Fenton M, Brayne C, et al. Dementia priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance: using patient and public involvement and the evidence base to inform the research agenda. Age & Ageing. 2015;44(6):985–993. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knight SR, Metcalfe L, O’Donoghue K, Ball ST, Beale A, Beale W, et al. Defining priorities for future research: results of the UK kidney transplant priority setting partnership. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0162136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Macbeth AE, Tomlinson J, Messenger AG, Moore-Millar K, Michaelides C, Shipman AR, et al. Establishing and prioritizing research questions for the treatment of alopecia areata: the Alopecia Areata Priority Setting Partnership. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(5):1316–1320. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McKenna C, Griffin S, Koffijberg H, Claxton K. Methods to place a value on additional evidence are illustrated using a case study of corticosteroids after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;70:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morris C, Simkiss D, Busk M, Morris M, Allard A, Denness J, et al. Setting research priorities to improve the health of children and young people with neurodisability: a British Academy of Childhood Disability-James Lind Alliance Research Priority Setting Partnership. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006233. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Owens C, Ley A, Aitken P. Do different stakeholder groups share mental health research priorities? A four-arm Delphi study. Health Expect. 2008;11(4):418–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perry DC, Wright JG, Cooke S, Roposch A, Gaston MS, Nicolaou N, et al. A consensus exercise identifying priorities for research into clinical effectiveness among children’s orthopaedic surgeons in the United Kingdom. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(5):680–684. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B6.BJJ-2018-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pollock A, St George B, Fenton M, Firkins L. Top 10 research priorities relating to life after stroke--consensus from stroke survivors, caregivers, and health professionals. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(3):313–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rangan A, Upadhaya S, Regan S, Toye F, Rees JL. Research priorities for shoulder surgery: results of the 2015 James Lind Alliance patient and clinician priority setting partnership. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010412. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rowat A, Pollock A, St George B, Cowey E, Booth J, Lawrence M, et al. Top 10 research priorities relating to stroke nursing: a rigorous approach to establish a national nurse-led research agenda. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(11):2831–2843. doi: 10.1111/jan.13048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rowe F, Wormald R, Cable R, Acton M, Bonstein K, Bowen M, et al. The Sight Loss and Vision Priority Setting Partnership (SLV-PSP): overview and results of the research prioritisation survey process. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7):e004905. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shepherd V, Wood F, Hood K. Establishing a set of research priorities in care homes for older people in the UK: a modified Delphi consensus study with care home staff. Age Ageing. 2017;46(2):284–90. 10.1093/ageing/afw204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Stephens RJ, Whiting C, Cowan K, James Lind Alliance Mesothelioma Priority Setting Partnership Steering C Research priorities in mesothelioma: A James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. Lung Cancer. 2015;89(2):175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Middendorp JJ, Allison HC, Ahuja S, Bracher D, Dyson C, Fairbank J, et al. Top ten research priorities for spinal cord injury: the methodology and results of a British priority setting partnership. Spinal Cord. 2016;54(5):341–346. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wan YL, Beverley-Stevenson R, Carlisle D, Clarke S, Edmondson RJ, Glover S, et al. Working together to shape the endometrial cancer research agenda: The top ten unanswered research questions. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(2):287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.08.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Willett KM, Gray B, Moran CG, Giannoudis PV, Pallister I. Orthopaedic trauma research priority-setting exercise and development of a research network. Injury. 2010;41(7):763–767. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Arora NK, Mohapatra A, Gopalan HS, Wazny K, Thavaraj V, Rasaily R, et al. Setting research priorities for maternal, newborn, child health and nutrition in India by engaging experts from 256 indigenous institutions contributing over 4000 research ideas: a CHNRI exercise by ICMR and INCLEN. J Global Health. 2017;7(1):011003. doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.011003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ravindran TKS, Seshadri T. A health equity research agenda for India: results of a consultative exercise. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(Suppl 1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Allotey J, Matei A, Husain S, Newton S, Dodds J, Armson AB, et al. Research prioritization of interventions for the primary prevention of preterm birth: an international survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;236:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bahl R, Martines J, Ali N, Bhan MK, Carlo W, Chan KY, et al. Research priorities to reduce global mortality from newborn infections by 2015. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(1 Suppl):S43–S48. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819588d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brown KH, Hess SY, Boy E, Gibson RS, Horton S, Osendarp SJ, et al. Setting priorities for zinc-related health research to reduce children’s disease burden worldwide: an application of the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative’s research priority-setting method. Public Health Nutrition. 2008;12(3):389–396. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brundin P, Barkerb RA, Connc PJ, Dawsond TM, Kieburtze K, Lees AJ, et al. Linked clinical trials-the development of new clinical learning studies in Parkinson’s disease using screening of multiple prospective new treatments. J Parkinson’s Dis. 2013;3(3):231–239. doi: 10.3233/JPD-139000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]