Abstract

Background

In February 2022, Massachusetts rescinded a statewide universal masking policy in public schools, and many Massachusetts school districts lifted masking requirements during the subsequent weeks. In the greater Boston area, only two school districts — the Boston and neighboring Chelsea districts — sustained masking requirements through June 2022. The staggered lifting of masking requirements provided an opportunity to examine the effect of universal masking policies on the incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) in schools.

Methods

We used a difference-in-differences analysis for staggered policy implementation to compare the incidence of Covid-19 among students and staff in school districts in the greater Boston area that lifted masking requirements with the incidence in districts that sustained masking requirements during the 2021–2022 school year. Characteristics of the school districts were also compared.

Results

Before the statewide masking policy was rescinded, trends in the incidence of Covid-19 were similar across school districts. During the 15 weeks after the statewide masking policy was rescinded, the lifting of masking requirements was associated with an additional 44.9 cases per 1000 students and staff (95% confidence interval, 32.6 to 57.1), which corresponded to an estimated 11,901 cases and to 29.4% of the cases in all districts during that time. Districts that chose to sustain masking requirements longer tended to have school buildings that were older and in worse condition and to have more students per classroom than districts that chose to lift masking requirements earlier. In addition, these districts had higher percentages of low-income students, students with disabilities, and students who were English-language learners, as well as higher percentages of Black and Latinx students and staff. Our results support universal masking as an important strategy for reducing Covid-19 incidence in schools and loss of in-person school days. As such, we believe that universal masking may be especially useful for mitigating effects of structural racism in schools, including potential deepening of educational inequities.

Conclusions

Among school districts in the greater Boston area, the lifting of masking requirements was associated with an additional 44.9 Covid-19 cases per 1000 students and staff during the 15 weeks after the statewide masking policy was rescinded.

The direct and indirect effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic on children, their families, and surrounding communities have been substantial. By the end of February 2022, children and adolescents in the United States had a higher prevalence of infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) than any other age group; children with Covid-19 are at risk for severe acute complications, death, and long-term sequelae (known as long Covid or post-Covid conditions).1-4 Furthermore, by the end of September 2022, more than 265,000 children and adolescents in the United States had had a parent or caregiver die from Covid-19,5,6 and the pandemic had caused substantial interruptions in school settings — including staffing shortages, closures, and missed school days — and had deepened educational inequities.7,8 These effects have been disproportionately borne by groups already made vulnerable by historical and contemporary systems of oppression, including structural racism and settler colonialism.9-11 Black, Latinx, and Indigenous children and adolescents are more likely to have had severe Covid-19, to have had a parent or caregiver die from Covid-19, and to be affected by worsening mental health and by educational disruptions than their White counterparts.6,8,12,13

During the Covid-19 pandemic, schools have become an important setting for implementing policies that minimize inequitable health, educational, social, and economic effects on children and their families. However, even before the pandemic, schools were not uniformly health-promoting environments. Chronic underinvestment in combination with structural racism codified in state-sanctioned historical and contemporary policies and practices (e.g., redlining, exclusionary zoning, disinvestment, and gentrification) eroded tax bases in some school districts and shaped the quality of public school infrastructure and associated environmental hazards.10,14-19 These processes left school districts differentially equipped to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic and concentrated high-risk conditions, such as crowded classrooms and poor indoor air quality due to outdated or absent ventilation or filtration systems, in low-income and Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities.14,18,19

Alongside other measures, universal masking with high-quality masks or respirators has been an important piece of a layered risk-mitigation strategy to reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in community and school settings below levels that have been observed with individual (optional) masking.20-31 Massachusetts was among the 18 states plus Washington, DC, that had a universal masking policy in public schools during the 2021–2022 school year.32 The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) rescinded the statewide masking policy on February 28, 2022, in accordance with updated guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and many Massachusetts school districts lifted masking requirements during the subsequent weeks. In the greater Boston area, only two school districts — the Boston and neighboring Chelsea districts — sustained masking requirements through June 2022.

The staggered lifting of masking requirements provided an opportunity to examine the potential effect of universal masking policies in schools. Specifically, this study aimed to assess trends in the observed weekly incidence of Covid-19 according to the length of time that school districts sustained masking requirements; to compare the incidence of Covid-19 among students and staff in districts that lifted masking requirements with the incidence in districts that sustained masking requirements in a given reporting week in order to estimate the effect of lifting masking requirements; and to compare school-district characteristics in districts that chose to sustain masking requirements longer with the characteristics in districts that chose to lift masking requirements earlier.

Methods

Study Population

This study considered the 79 public, noncharter school districts in the greater Boston area, defined according to the U.S. Census Bureau as the New England city and town area of Boston–Cambridge–Newton (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). Of these 79 school districts, 7 with unreliable or missing Covid-19 data were excluded (Table S1). The final sample included 72 school districts, which comprised 294,084 students and 46,530 staff during the study period. The study period was defined as the 40 calendar weeks of the 2021–2022 school year, which ended on June 15, 2022 (the end of the last full reporting week in all districts).

Intervention and Primary Outcome

The primary exposure variable was whether a school district lifted or sustained its masking requirement in each reporting week. For all school districts, masking requirements were in place from the start of the study period through February 28, 2022, when the statewide masking policy was rescinded. A school district was considered to have lifted its masking requirement in a given reporting week if the requirement had been lifted before the first day of the reporting week (reporting weeks start on Thursday). The primary outcome was the incidence of Covid-19 among students and staff, considered together and separately.

Data Sources

For each school district, data regarding weekly Covid-19 cases, student enrollment, and staffing during the 2021–2022 school year were publicly available from the Massachusetts DESE.33,34 Throughout the study period, DESE required standardized weekly reporting of all positive tests for Covid-19 among students and staff, regardless of symptoms, testing type or program (e.g., testing of symptomatic persons or pooled polymerase-chain-reaction testing), and testing location (community setting or school setting). Details regarding DESE reporting requirements are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. DESE strongly encouraged, and provided full funding for, school districts to opt in to standardized Covid-19 testing programs; 2311 Massachusetts schools (approximately 95%) participated in at least one such program. From 1 month before the statewide masking policy was rescinded through the end of the school year, statewide testing recommendations did not differ according to masking or vaccination status (Table S2).35

The dates during which masking requirements were in place for each school district were obtained from school-district websites or local news sources. For sensitivity analyses, data to be used for covariate adjustments, including data regarding Covid-19 indicators (i.e., measures of Covid-19 burden) according to city and town and Covid-19 vaccination coverage according to age, were publicly available from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. For descriptive analyses, data regarding the distribution of students and staff according to sociodemographic characteristics and the distribution of students in populations selected and defined by DESE (low-income students, students with disabilities, and English-language learner [ELL] students) during the 2021–2022 school year were obtained from DESE.34 In addition, data regarding building conditions and learning environment were obtained from the Massachusetts School Building Authority 2016–2017 school survey (most recent data).36

Contributions

The first, second, and last authors wrote the first draft of the manuscript and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and the fidelity of the study to the statistical analysis plan, available at NEJM.org. All the authors reviewed and edited the draft and made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. No external funding was received for this study.

Statistical Analysis

Trends in the observed incidence of Covid-19 (weekly Covid-19 cases per 1000 population) before the statewide masking policy was rescinded were compared with trends after the policy was rescinded according to the length of time that school districts sustained masking requirements. A difference-in-differences analysis for staggered policy implementation was used to compare the incidence of Covid-19 in school districts that lifted masking requirements with the incidence in districts that sustained masking requirements in a given reporting week (i.e., school districts that had not yet lifted masking requirements) in order to estimate the effect of lifting masking requirements.37,38

Difference-in-differences methods allow for the estimation of causal effects of policy changes enacted at the group level by comparing the change in the outcome over time in the intervention group with the change in the control group, under an assumption of parallel trends (i.e., in the absence of the intervention, outcomes in the intervention group and the control group would have remained parallel over time).37,39 Unlike some observational methods, difference-in-differences methods are not biased by unmeasured time-invariant confounders or time-varying confounders with consistent trends across the intervention and control groups; the absence of such bias strengthens causal inferences. In this analysis, the weekly and cumulative effects of lifting masking requirements during the 15 weeks after the statewide masking policy was rescinded were estimated with respect to the incidence of Covid-19 cases in school districts that lifted masking requirements (i.e., the average [mean] treatment effect among the treated). Details regarding the difference-in-differences analysis are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed: a formal test for parallel trends before masking requirements were lifted; adjustment for time-varying covariates, including Covid-19 indicators at the community level, vaccination coverage, and previous incidences of infection among students and staff; and an assessment of the potential effects of differences in testing definitions or programs across districts (Tables S3 and S4). In the main analysis, data for the weeks in which school districts did not report Covid-19 cases were corrected (these weeks were originally recorded as having zero cases), all school districts in the greater Boston area were included as comparison districts, and weighting according to school population size was performed to capture the effect of masking policies at the population level.

Finally, to provide insight into Covid-19 policy decisions in schools and their potential to exacerbate or mitigate inequities in Covid-19 incidence and educational outcomes, descriptive analyses were performed. The decision to sustain or lift masking requirements was assessed according to various school-district characteristics, including sociodemographic characteristics of the students and staff and physical characteristics of the learning environment.

Results

Primary Analysis

Of the 72 school districts in the greater Boston area that were included in the study, only Boston Public Schools and Chelsea Public Schools sustained masking requirements throughout the study period (Fig. S2A). Of the remaining school districts, 46 districts (64%) lifted masking requirements in the first reporting week after the statewide masking policy was rescinded, 17 (24%) lifted masking in the second reporting week, and 7 (10%) lifted masking in the third reporting week (Fig. S2B). Cumulatively, 46 districts lifted masking requirements and 26 districts sustained masking requirements by the first reporting week after the policy was rescinded, 63 lifted and 9 sustained masking by the second reporting week, and 70 lifted and 2 sustained masking thereafter.

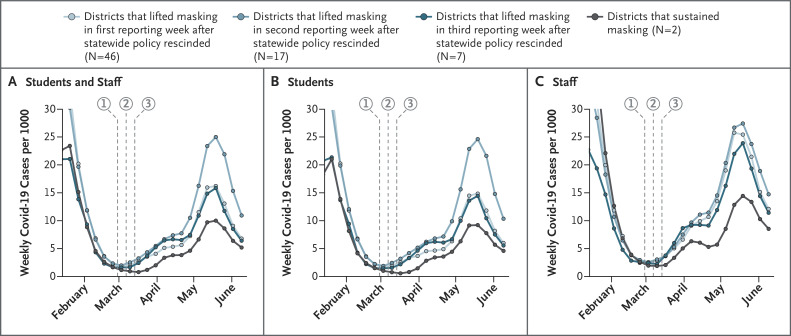

Before the statewide masking policy was rescinded, the trends in the incidence of Covid-19 observed in the Boston and Chelsea districts were similar to the trends in school districts that later lifted masking requirements. However, after the statewide masking policy was rescinded, the trends in the incidence of Covid-19 diverged, with a substantially higher incidence observed in school districts that lifted masking requirements than in school districts that sustained masking requirements. These trends were observed among students and staff overall (Figure 1A), as well as among students alone (Figure 1B) and among staff alone (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Incidence of Covid-19 in School Districts in the Greater Boston Area before and after the Statewide Masking Policy Was Rescinded.

The observed incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) (weekly Covid-19 cases per 1000 population) among students and staff overall (Panel A), among students alone (Panel B), and among staff alone (Panel C) is shown for the 72 school districts in the greater Boston area that were included in the study. The greater Boston area was defined according to the U.S. Census Bureau as the New England city and town area of Boston–Cambridge–Newton. The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education rescinded the statewide masking policy on February 28, 2022. The incidence is shown according to whether the school district lifted its masking requirement in the first, second, or third reporting week after the statewide masking policy was rescinded or the district sustained its masking requirement. A school district was considered to have lifted its masking requirement in a given reporting week if the requirement had been lifted before the first day of the reporting week (reporting weeks start on Thursday). The dashed lines indicate the first (1), second (2), and third (3) school weeks (school weeks start on Monday) during which school districts lifted masking requirements. A total of 46 school districts lifted masking requirements during the first school week (starting on February 28, 2022) and in the first reporting week (starting on March 3, 2022) after the statewide masking policy was rescinded; 17 districts lifted masking requirements during the second school week (starting on March 7, 2022) and in the second reporting week (starting on March 10, 2022); 7 districts lifted masking requirements during the third school week (starting on March 14, 2022) and in the third reporting week (starting on March 17, 2022); and 2 districts sustained masking requirements. Data points are shown on the first day of the reporting week and represent 3-week trailing rolling averages to reduce statistical noise. Dates on the x axis are restricted to the period immediately before and after the statewide masking policy was rescinded.

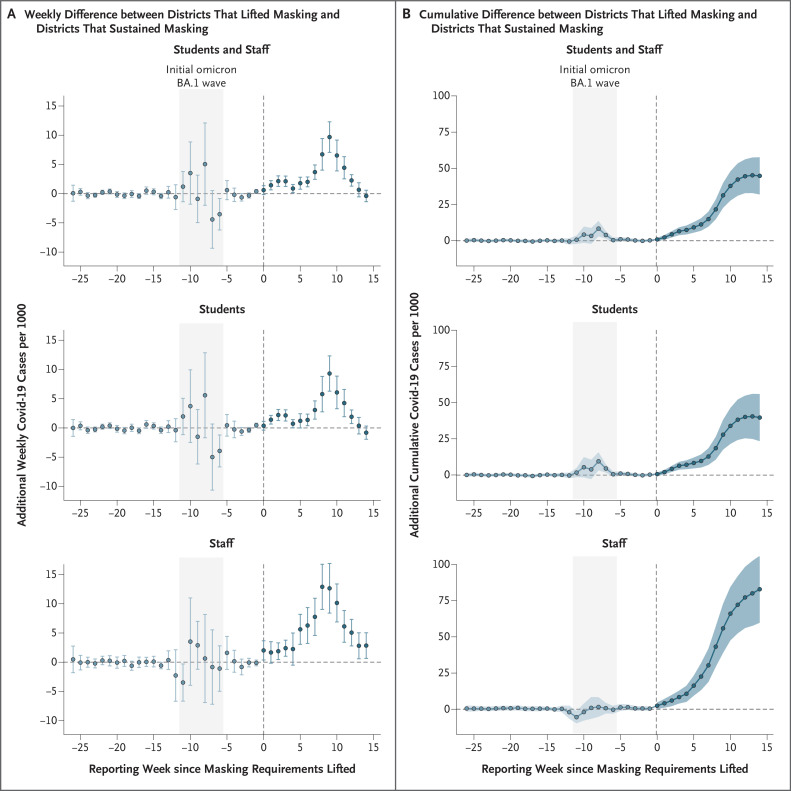

Figure 2 shows difference-in-differences estimates of additional weekly and cumulative Covid-19 cases associated with the lifting of masking requirements. Before masking requirements were lifted, difference-in-differences estimates were essentially zero, a finding that supports the assumption of parallel trends. After masking requirements were lifted, the lifting of masking requirements was consistently associated with additional Covid-19 cases. The effect was significant during 12 of the 15 weeks after masking requirements were lifted. Weekly estimates ranged from 1.4 additional cases per 1000 students and staff (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.6 to 2.3) in the first reporting week after masking requirements were lifted to 9.7 additional cases per 1000 students and staff (95% CI, 7.1 to 12.3) in the ninth reporting week.

Figure 2. Difference-in-Differences Estimates of Additional Weekly and Cumulative Covid-19 Cases Associated with the Lifting of Masking Requirements.

Difference-in-differences models were used to estimate the difference in the change in the incidence of Covid-19 between school districts that lifted masking requirements and school districts that sustained masking requirements in each reporting week among students and staff overall, among students alone, and among staff alone, with estimates calculated on a weekly basis (Panel A) and on a cumulative basis (Panel B). 𝙸 bars and blue shading indicate 95% confidence intervals for weekly and cumulative differences, respectively. Estimates are shown according to reporting weeks since masking requirements were lifted. Vertical dashed lines indicate the first reporting week in which masking requirements were lifted in each school district; because the reporting week in which masking requirements were lifted varied according to district, the vertical dashed lines represent different calendar weeks for different school districts, depending on when masking requirements were lifted. Values in light blue and dark blue show differences during the reporting weeks before and after masking requirements were lifted, respectively. Horizontal dashed lines correspond to no difference; values above the line show additional Covid-19 cases. Gray shading indicates the initial period of peak infection with the BA.1 subvariant of the B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant (December 2021 through January 2022). Details regarding the difference-in-differences analysis are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

The strength of the association between school masking policies and the incidence of Covid-19 in school districts varied according to the incidence of Covid-19 in surrounding communities; the strongest associations were observed during the weeks when the incidences in surrounding communities were highest (Figs. S3 and S4). The weekly effects that were observed among students and staff overall were similar to those observed among students alone and those observed among staff alone, with slightly greater effects observed among staff than among students. In addition, the weekly effects were consistent with the cumulative effects.

Overall, the lifting of masking requirements was associated with an additional 44.9 Covid-19 cases per 1000 students and staff (95% CI, 32.6 to 57.1) during the 15 weeks after the statewide masking policy was rescinded (Table 1). This estimate corresponded to an additional 11,901 Covid-19 cases (95% CI, 8651 to 15,151), which accounted for 33.4% of the cases (95% CI, 24.3 to 42.5) in school districts that lifted masking requirements and for 29.4% of the cases (95% CI, 21.4 to 37.5) in all school districts during that period. The effect was more pronounced among staff. The lifting of masking requirements was associated with an additional 81.7 Covid-19 cases per 1000 staff (95% CI, 59.3 to 104.1) during the 15-week period, with these cases accounting for 40.4% of the cases (95% CI, 29.4 to 51.5) among staff in school districts that lifted masking requirements. Because persons who had a positive test for Covid-19 were instructed to isolate for at least 5 days, the additional cases translated to a minimum of approximately 17,500 missed school days for students and 6500 missed school days for staff during the 15-week period (Table S5).

Table 1. Cumulative Incidence of Covid-19 and Estimated Effect of Lifting Masking Requirements during the 15 Weeks after the Statewide Masking Policy Was Rescinded.*.

| Population† | Cumulative Covid-19 Cases during the 15-Week Period | Difference-in-Differences Estimates of Covid-19 Cases Associated with the Lifting of Masking Requirements during the 15-Week Period | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Districts | Districts That Lifted Masking Requirements | Districts That Sustained Masking Requirements | No. of Additional Cases per 1000 (95% CI)‡ | No. of Additional Cases (95% CI)§ | Percentage of Cases in Districts That Lifted Masking Requirements (95% CI)¶ | Percentage of Cases in All Districts (95% CI)‖ | ||||

| no. of cases | no. of cases per 1000 | no. of cases | no. of cases per 1000 | no. of cases | no. of cases per 1000 | |||||

| Students and staff | 40,416 | 119.8 | 35,651 | 134.4 | 4,766 | 66.1 | 44.9 (32.6–57.1) | 11,901 (8651–15,151) | 33.4 (24.3–42.5) | 29.4 (21.4–37.5) |

| Students | 32,198 | 110.6 | 28,524 | 124.1 | 3,674 | 60.0 | 39.9 (24.3–55.4) | 9,168 (5594–12,743) | 32.1 (19.6–44.7) | 28.5 (17.4–39.6) |

| Staff | 8,218 | 178.4 | 7,127 | 202.1 | 1,091 | 101.0 | 81.7 (59.3–104.1) | 2,882 (2092–3673) | 40.4 (29.4–51.5) | 35.1 (25.5–44.7) |

The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education rescinded the statewide masking policy on February 28, 2022. Details regarding the difference-in-differences analysis are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. Covid-19 denotes coronavirus disease 2019.

The study included a total of 340,614 students and staff (294,084 students and 46,530 staff) across 72 school districts. The number of districts that lifted masking requirements and the number of districts that sustained masking requirements varied according to reporting week; the mean population per week during the 15-week period was 265,173 students and staff (229,899 students and 35,274 staff) in districts that lifted masking requirements and was 72,053 students and staff (61,250 students and 10,803 staff) in districts that sustained masking requirements. The sum of these mean populations per week does not equal the total study population because of the exclusion of less than 1% of person-weeks (see the Supplementary Appendix).

A difference-in-differences model was used to estimate the cumulative average treatment effect among the treated during the 15-week period. The number of additional Covid-19 cases per 1000 population that were associated with the lifting of masking requirements was estimated by calculating the difference between the observed number of Covid-19 cases per 1000 population in districts that lifted masking requirements and the expected number of Covid-19 cases per 1000 population if masking requirements had been sustained during the 15 weeks after the statewide masking policy was rescinded.

The number of additional Covid-19 cases that were associated with the lifting of masking requirements was estimated by multiplying the number of additional Covid-19 cases per 1000 population that were associated with the lifting of masking requirements (from the difference-in-differences model) by the mean population per 1000 in school districts that lifted masking requirements.

The percentage of Covid-19 cases in school districts that lifted masking requirements that were associated with the lifting of masking requirements was estimated by dividing the number of additional Covid-19 cases per 1000 population that were associated with the lifting of masking requirements (from the difference-in-differences model) by the observed number of Covid-19 cases per 1000 population in school districts that lifted masking requirements.

The percentage of Covid-19 cases in all school districts that were associated with the lifting of masking requirements was estimated by dividing the number of additional Covid-19 cases that were associated with the lifting of masking requirements by the observed number of Covid-19 cases in all school districts.

Sensitivity Analyses

The results were shown to be robust in a range of sensitivity analyses, including analyses that assessed potential differences in testing programs and analyses that adjusted for Covid-19 indicators at the community level and vaccination coverage according to age (Fig. S5). Results of sensitivity analyses are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

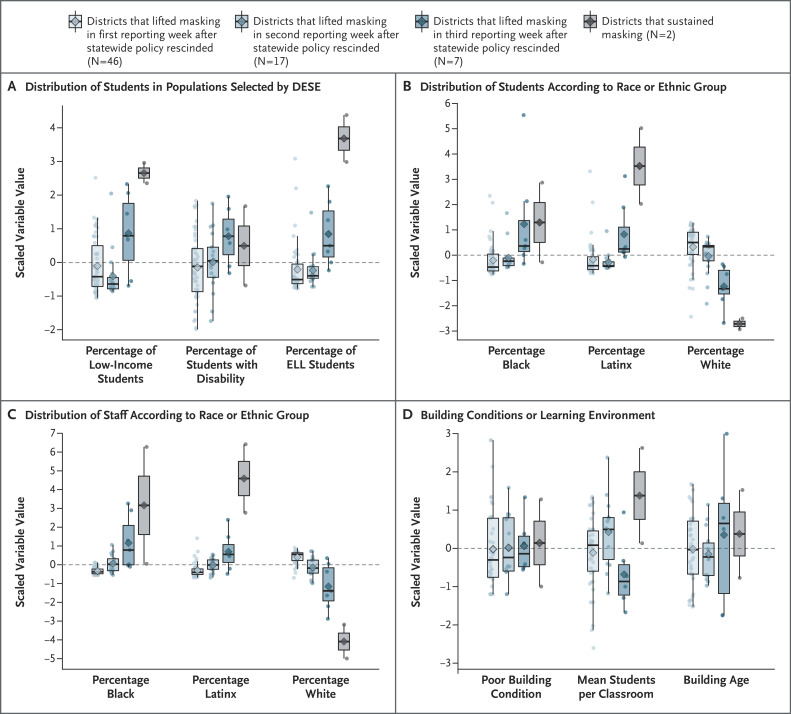

Descriptive Analyses

School districts that chose to sustain masking requirements longer had higher percentages of low-income students, students with disabilities, and ELL students (Figure 3A), as well as higher percentages of Black and Latinx students (Figure 3B) and Black and Latinx staff (Figure 3C), than school districts that chose to lift masking requirements earlier. In addition, school districts that chose to sustain masking requirements longer tended to have school buildings that were older and in worse physical condition (e.g., with outdated or absent ventilation or filtration systems) and to have more students per classroom (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Characteristics of the School Districts.

Data regarding the following school-district characteristics are shown: distribution of students in populations selected and defined by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), including low-income students, students with disabilities, and English-language learner (ELL) students (Panel A); distribution of students according to race or ethnic group (Panel B); distribution of staff according to race or ethnic group (Panel C); and scores for building conditions and learning environment (Panel D). The data are shown in scaled variable values so that all variables can be depicted on the same scale; the scaled variable value reflects the difference from the mean value in standard deviations. Dashed lines indicate the mean value across all school districts. Dots indicate values for individual school districts. In the box plots, horizontal bars indicate the median value, boxes the interquartile range, whiskers the value 1.5 times the interquartile range, and diamonds the mean value. Data are plotted according to whether the school district had chosen to lift its masking requirement in the first, second, or third reporting week after the statewide masking policy was rescinded or the district had chosen to sustain its masking requirement. The data shown in Panels A, B, and C are for the 2021–2022 school year and were obtained from DESE.34 The data shown in Panel D were obtained from the Massachusetts School Building Authority 2016–2017 school survey (most recent data).36

Discussion

Schools are an important yet politically contested space in the Covid-19 response, which makes analyses such as this one particularly relevant to decision makers. We estimated that the lifting of masking requirements in school districts in the greater Boston area during March 2022 contributed an additional 45 Covid-19 cases per 1000 students and staff during the following 15-week period. Overall, this estimate corresponded to nearly 12,000 additional Covid-19 cases among students and staff, which accounted for one third of the cases in school districts that lifted masking requirements during that time and most likely translated to substantial loss of in-person school days.

We observed that the effect of school masking policies was greatest during the weeks when the background incidences of Covid-19 in surrounding cities and towns were highest, a finding that suggests that universal masking policies may be most effective when they are implemented before and throughout periods of high SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Under the CDC guidance at that time, as well as the updated guidance issued in August 2022, universal masking would not have been recommended until the incidences of Covid-19 in schools and surrounding communities were already nearing their peak (May 2022); by this time, a substantial proportion of the effects of masking polices that we observed had already accrued. As such, relying on lagging metrics such as CDC Covid-19 Community Levels and Covid-19 hospitalizations to inform school masking policies is most likely insufficient to prevent Covid-19 cases and loss of in-person school days, and policymakers might instead consider measures of community transmission (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 wastewater concentration or Covid-19 incidence) to inform such policies.

Understanding Covid-19 policy decisions requires attention to power and existing historical and sociopolitical contexts.10,40 Structural racism and racial capitalism operate through multiple pathways, including higher levels of household crowding and employment in essential industries and lower levels of access to testing, vaccines, and treatment; these structural forces differentially concentrate the risk of both SARS-CoV-2 exposure and severe Covid-19 in low-income and Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities.9-11,18 In our study, school districts that chose to sustain masking requirements longer tended to have school buildings in worse physical condition and more students per classroom, and these districts had higher percentages of students and staff already made vulnerable by historical and contemporary systems of oppression (e.g., racism, capitalism, xenophobia, and ableism). In Boston and Chelsea, more than 80% of the students are Black, Latinx, or people of color, and these cities were among the Massachusetts cities and towns that were hit hardest by Covid-19. Students and families in these school districts have strongly advocated and organized for governmental action to increase Covid-19 protections in schools, emphasizing their role as essential workers, the risk to vulnerable family members, and the unequal consequences of missed work and school.41,42 The decision in some school districts to sustain school masking policies longer may therefore reflect an understanding among parents and elected officials that structural racism is embedded in public policies and that policy decisions have the potential to rectify or reproduce health inequities.10,14,16,40

A growing body of work suggests that knowledge of differential conditions and inequitable effects may decrease support for Covid-19 protections among systematically advantaged groups, whose relative position largely insulates them from Covid-19 harms, while simultaneously increasing support among groups that are directly affected by systems of oppression.43-45 For example, in a randomized trial in which White persons were assigned to receive information about structural causes of persistent Covid-19 inequities across racial or ethnic groups or to not receive such information, those who received the information were less likely to support Covid-19 prevention policies and were less likely to report individual concern about Covid-19 and empathy for the groups that were most affected.45 In several studies and polls, Black and Latinx parents were more likely than White parents to support school masking requirements and less likely to have confidence that schools could operate safely without additional protections.43,44,46 Failure to consider unequal baseline conditions and ongoing inequitable effects of Covid-19 policies risks further exacerbating inequities in Covid-19 incidence and educational outcomes.

Because universal masking policies in schools have been contentious, we anticipate several critiques. One such critique is that the benefits of universal masking in schools are outstripped by potential disruptions to teaching, learning, and social development. These effects warrant further rigorous evaluation; however, to date, there is no clear existing evidence that masking inhibits learning or harms development.47,48 In addition, such effects might be considered alongside the spectrum of benefits of universal masking, including fewer missed school days and staffing shortages, reduced risk of illness for students and their families, and reduced economic hardship for caregivers, who might miss work if their child is sick or if they become ill themselves. For example, in Lexington, MA, a comparison district approximately 10 miles from Boston, mean student and staff absences due to Covid-19 during weeks when masking was optional were 50% higher than absences during previous weeks, when masking was required (see the Supplementary Appendix).

In addition, severe Covid-19 and post-Covid conditions remain substantial risks among school-age children. Like much of the United States, the greater Boston area has low Covid-19 vaccination coverage among children (only 53% of children 5 to 11 years of age had been fully vaccinated in Boston and Chelsea through October 2022, as compared with 67% in comparison districts), with substantial inequities according to race or ethnic group and socioeconomic status. Furthermore, we observed greater benefits of sustaining masking among staff, a finding that emphasizes that universal masking is an important component of comprehensive workplace protections for staff, who may be at a higher risk for severe Covid-19 than students. In addition, staff absences may be especially consequential for students who need additional educational supports and services, including ELL students and students with disabilities.

A second common critique is that there are alternative approaches to reducing transmission and severe disease, such as improved ventilation and increased vaccination coverage. Our findings show that the better ventilation and higher vaccination coverage in school districts that lifted masking requirements than in districts that sustained masking requirements were insufficient to prevent all Covid-19 cases in these schools. Therefore, although we cannot weigh the full spectrum of individual and societal implications of masking policies, our study highlights the important role of interim universal school masking policies in mitigating the effects of Covid-19 while longer-term, more sustainable policies are developed to increase vaccination uptake and improve learning environments.

A key strength of this study is our use of difference-in-differences methods with staggered dates of the lifting of masking requirements. Although there are some factors related to SARS-CoV-2 exposure that differed across school districts, difference-in-differences methods yield robust analyses in the context of sources of confounding that do not change over time (e.g., sociodemographic characteristics or building conditions) or do not coincide with the policy change of interest. In sensitivity analyses, the benefits of masking requirements persisted after we controlled for Covid-19 indicators at the community level, vaccination coverage, and previous incidence of infection. Furthermore, we found that school districts that lifted masking requirements were districts that would have been expected to have lower incidences of Covid-19 (on average, they had buildings in better physical condition and had higher vaccination coverage), which suggests that any residual confounding by Covid-19 risk would have led to underestimation of the harms of lifting masking requirements overall.

A limitation of this study is that we did not have data regarding Covid-19 testing in individual school districts. However, DESE ended the practice of required testing of only unmasked close contacts in January 2022, and data from that “test-and-stay” program show that far too few schools continued with the program for it to explain our results. Under the most extreme assumptions, additional testing of unmasked close contacts could explain less than 7% of the estimated excess cases. Overall, our findings should be interpreted as the effect of universal masking policies and not as the effect of masking per se, since masks were still encouraged in most school settings. Despite this consideration, the effect of lifting masking requirements was substantial.

The winter wave of the B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant during the 2021–2022 school year will not be the final Covid-19 surge to affect students and staff, and ongoing efforts to address inequitable environmental risks and effects of Covid-19 in school settings are urgently needed. Our results support that universal masking with high-quality masks or respirators during periods of high community transmission is an important strategy for minimizing SARS-CoV-2 spread and loss of in-person school days. Our results also suggest that universal masking may be an important tool for mitigating the effects of structural racism in schools, including the differential risk of severe Covid-19, educational disruptions, and health and economic effects of secondary transmission to household members. School districts could use these findings to develop equitable mitigation plans in anticipation of a potential winter Covid-19 wave during the 2022–2023 school year, as well as clear decision thresholds for removing masks as the wave abates.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Boston Public Schools staff and leadership and the nurses and team within Boston Public Schools Health Services for their role in protecting our Boston children and families; and Dr. Brigette Davis and Dr. Jourdyn Lawrence for their critical review and feedback on earlier drafts of this work.

Statistical Analysis Plan

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This article was published on November 9, 2022, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Clarke KEN, Jones JM, Deng Y, et al. Seroprevalence of infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies — United States, September 2021–February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:606-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller AD, Yousaf AR, Bornstein E, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) during SARS-CoV-2 delta and omicron variant circulation — United States, July 2021–January 2022. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:Suppl 2:S303-S307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. September 1, 2022. (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html).

- 4.Kompaniyets L, Bull-Otterson L, Boehmer TK, et al. Post-COVID-19 symptoms and conditions among children and adolescents — United States, March 1, 2020–January 31, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:993-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imperial College London. COVID-19 orphanhood. 2022. (https://imperialcollegelondon.github.io/orphanhood_calculator/#/country/United%20States%20of%20America).

- 6.Hillis SD, Blenkinsop A, Villaveces A, et al. COVID-19-associated orphanhood and caregiver death in the United States. Pediatrics 2021. October 7 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parks SE, Zviedrite N, Budzyn SE, et al. COVID-19-related school closures and learning modality changes — United States, August 1–September 17, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1374-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunez-Smith M, COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force. Presidential COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force — final report and recommendations. Department of Health and Human Services, October 2021. (https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/HETF_Report_508_102821_9am_508Team%20WIP11.pdf).

- 9.Laster Pirtle WN. Racial capitalism: a fundamental cause of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic inequities in the United States. Health Educ Behav 2020;47:504-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey ZD, Moon JR. Racism and the political economy of COVID-19: will we continue to resurrect the past? J Health Polit Policy Law 2020;45:937-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emerson MA, Montoya T. Confronting legacies of structural racism and settler colonialism to understand COVID-19 impacts on the Navajo Nation. Am J Public Health 2021;111:1465-1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi DS, Whitaker M, Marks KJ, et al. Hospitalizations of children aged 5–11 years with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 2020–February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:574-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao Y, Yip PS-F, Pathak J, Mann JJ. Association of social determinants of health and vaccinations with child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Psychiatry 2022;79:610-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neal DE. Healthy schools: a major front in the fight for environmental justice. Environ Law 2008;38:473-493. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson S, Hutson M, Mujahid M. How planning and zoning contribute to inequitable development, neighborhood health, and environmental injustice. Environ Justice 2008;1:211-216. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017;389:1453-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bullard RD, Wright BH. Environmental justice for all: community perspectives on health and research needs. Toxicol Ind Health 1993;9:821-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitzmiller EM, Drake Rodriguez A. Addressing our nation’s toxic school infrastructure in the wake of COVID-19. Educ Res 2022;51:88-92. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastor M Jr, Sadd JL, Morello-Frosch R. Who’s minding the kids? Pollucion, public schools, and environmental justice in Los Angeles. Soc Sci Q 2002;83:263-280. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiens KE, Smith CP, Badillo-Goicoechea E, et al. In-person schooling and associated COVID-19 risk in the United States over spring semester 2021. Sci Adv 2022;8(16):eabm9128-eabm9128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lessler J, Grabowski MK, Grantz KH, et al. Household COVID-19 risk and in-person schooling. Science 2021;372:1092-1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gettings J, Czarnik M, Morris E, et al. Mask use and ventilation improvements to reduce COVID-19 incidence in elementary schools — Georgia, November 16–December 11, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:779-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falk A, Benda A, Falk P, Steffen S, Wallace Z, Høeg TB. COVID-19 cases and transmission in 17 K–12 schools — Wood County, Wisconsin, August 31–November 29, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:136-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boutzoukas AE, Zimmerman KO, Inkelas M, et al. School masking policies and secondary SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Pediatrics 2022;149(6):e2022056687-e2022056687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrejko KL, Pry J, Myers JF, et al. Predictors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection following high-risk exposure. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75(1):e276-e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrejko KL, Pry JM, Myers JF, et al. Effectiveness of face mask or respirator use in indoor public settings for prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection — California, February–December 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:212-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budzyn SE, Panaggio MJ, Parks SE, et al. Pediatric COVID-19 cases in counties with and without school mask requirements — United States, July 1–September 4, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1377-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jehn M, McCullough JM, Dale AP, et al. Association between K–12 school mask policies and school-associated COVID-19 outbreaks — Maricopa and Pima counties, Arizona, July–August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1372-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donovan CV, Rose C, Lewis KN, et al. SARS-CoV-2 incidence in K–12 school districts with mask-required versus mask-optional policies — Arkansas, August–October 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:384-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray TS, Malik AA, Shafiq M, et al. Association of child masking with COVID-19-related closures in US childcare programs. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(1):e2141227-e2141227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bagheri G, Thiede B, Hejazi B, Schlenczek O, Bodenschatz E. An upper bound on one-to-one exposure to infectious human respiratory particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118(49):e2110117118-e2110117118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Decker S. Which states banned mask mandates in schools, and which required masks? EducationWeek. July 8, 2022. (updated date) (https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/which-states-ban-mask-mandates-in-schools-and-which-require-masks/2021/08).

- 33.Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Positive COVID-19 cases in schools. State Library of Massachusetts, June 6, 2022. (https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/833423).

- 34.Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. School and district profiles — statewide reports (https://profiles.doe.mass.edu/state_report/).

- 35.Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Memorandum: DESE/DPH protocols for responding to COVID-19 scenarios — SY 2021–22. State Library of Massachusetts, January 5, 2022. (https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/852221).

- 36.Massachusetts School Building Authority. 2016 School survey report. 2017. (https://www.massschoolbuildings.org/sites/default/files/edit-contentfiles/Programs/School_Survey/2016/MSBA%202016%20Survey%20Report_102417-FINAL.pdf).

- 37.Callaway B, Sant’Anna PHC. Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. J Econom 2021;225:200-230. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth J, Sant’Anna PHC, Bilinski A, Poe J. What’s trending in difference-in-differences? A synthesis of the recent econometrics literature. January 13, 2022. (http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.01194). preprint.

- 39.Wing C, Simon K, Bello-Gomez RA. Designing difference in difference studies: best practices for public health policy research. Annu Rev Public Health 2018;39:453-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michener J. Race, power, and policy: understanding state anti-eviction policies during COVID-19. Policy Soc 2022;41:231-246. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartlett J. Mass. health leaders call for stepped-up COVID plans for fall and winter. Boston Globe.August 22, 2022. (https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/08/22/metro/mass-health-leaders-call-stepped-up-covid-plans-fall-winter/).

- 42.Daniel S. Students across city ‘walk-out’ to protest lack of Covid safety. Dorchester Reporter.January 20, 2022. (https://www.dotnews.com/2022/students-across-city-walk-out-protest-lack-covid-safety).

- 43.Cotto R Jr, Woulfin S. Choice with(out) equity? Family decisions of child return to urban schools in pandemic. JFDE 2021;4:42-63. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilbert LK, Strine TW, Szucs LE, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in parental attitudes and concerns about school reopening during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1848-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skinner-Dorkenoo AL, Sarmal A, Rogbeer KG, André CJ, Patel B, Cha L. Highlighting COVID-19 racial disparities can reduce support for safety precautions among White U.S. residents. Soc Sci Med 2022;301:114951-114951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parr R. New K–12 parent poll: student mental health, academics pose challenge to Massachusetts schools COVID recovery plans. MassINC Polling Group, May 2, 2022. (https://www.massincpolling.com/the-topline/new-k-12-parent-poll-student-mental-health-academics-pose-challenge-to-massachusetts-schools-covid-recovery-plans).

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science brief: community use of masks to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2. December 6, 2021. (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/masking-science-sars-cov2.html). [PubMed]

- 48.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Do masks delay speech and language development? Healthychildren.org, August 6, 2021. (https://web.archive.org/web/20220826213955/https://healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/COVID-19/Pages/Do-face-masks-interfere-with-language-development.aspx).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.