Abstract

Circadian rhythms are considered a masterstroke of natural selection, which gradually increase the adaptability of species to the Earth’s rotation. Importantly, the nervous system plays a key role in allowing organisms to maintain circadian rhythmicity. Circadian rhythms affect multiple aspects of cognitive functions (mainly via arousal), particularly those needed for effort-intensive cognitive tasks, which require considerable top-down executive control. These include inhibitory control, working memory, task switching, and psychomotor vigilance. This mini review highlights the recent advances in cognitive functioning in the optical and multimodal neuroimaging fields; it discusses the processing of brain cognitive functions during the circadian rhythm phase and the effects of the circadian rhythm on the cognitive component of the brain and the brain circuit supporting cognition.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available in the online version of this article at 10.1007/s12200-021-1090-y and is accessible for authorized users.

Keywords: circadian rhythm, cognition, optical neuroimaging, multimodal neuroimaging

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by MYRG2019-00082-FHS and MYRG2018-00081-FHS Grants from the University of Macau, as wellasFDCT025/2015/A1 and FDCT0011/2018/A1 Grants from the Macau Government.

Supporting Information

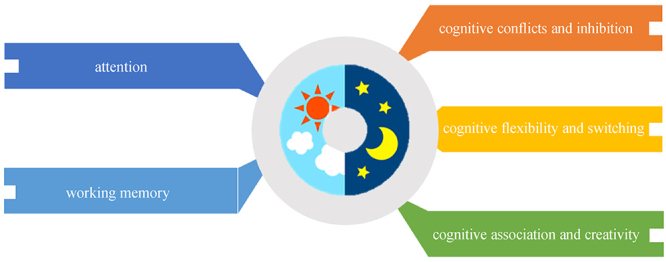

Relationship between circadian rhythm and brain cognitive functions

Footnotes

Shiyang Xu is a Ph.D. student at Faculty of Health Sciences, Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences, University of Macau, China. He received the Master’s degree in Developmental and Educational Psychology from Shaanxi Normal University, China. He concentrates on the neuroimaging (EEG/fNIRS) with disease and children development.

Miriam Akioma is a full-time Ph.D. research scholar at the Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, China. She holds Master’s degree in Applied Linguistics, and Specialization in Developmental Psychology. Her current research focuses on neuroimaging techniques for mapping the neural mechanisms and correlates related to language production, and comprehension in the bilingual brain. For that, she makes use of recent high-technologies such as fNIRS, EEG, fMRI, and eye-tracking.

Zhen Yuan is an associate professor with Faculty of Health Sciences (FHS) at University of Macau (UM), China. He also has the second appointment as the Interim Director of Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences at UM. His academic investigation is focused on cutting-edge research and development in laser, ultrasound and EEG/fMRI-related biomedical technologies as well as their clinical/pre-clinical applications in cognitive neuroscience and brain disorders. He has achieved national and international recognition through over 200 SCI publications in high ranked journals in his field. He is the editorial board member of Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery, editor of Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences, senior associate editor of BMC Medical Imaging, and associate editor of Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. He is a senior member of OSA and SPIE, and committee member of Chinese Biomedical Optical Society.

References

- 1.Refinetti R. Homeostasis and circadian rhythmicity in the control of body temperature. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;813(1):63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang R C. The discoveries of molecular mechanisms for the circadian rhythm: The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Biomedical Journal. 2018;41(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeMairan J. Histoire de l’Academie Royale des Sciences. Paris 1729

- 4.Reddy S, Reddy V, Sharma S. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Physiology, Circadian Rhythm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke T M, Scheer F A J L, Ronda J M, Czeisler C A, Wright K P., Jr. Sleep inertia, sleep homeostatic and circadian influences on higher-order cognitive functions. Journal of Sleep Research. 2015;24(4):364–371. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdez P. Circadian rhythms in attention. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2019;92(1):81–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker W H 2, Walton J C, DeVries A C, Nelson R J. Circadian rhythm disruption and mental health. Translational Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):28. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-0694-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett C L, Petros T V, Johnson M, Ferraro F R. Individual differences in the influence of time of day on executive functions. American Journal of Psychology. 2008;121(3):349–361. doi: 10.2307/20445471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qasrawi S O, Pandi-Perumal S R, BaHammam A S. The effect of intermittent fasting during Ramadan on sleep, sleepiness, cognitive function, and circadian rhythm. Sleep and Breathing. 2017;21(3):577–586. doi: 10.1007/s11325-017-1473-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owens J A. Sleep in children: cross-cultural perspectives. Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 2004;2(3):165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2004.00147.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preckel F, Lipnevich A, Schneider S, Roberts R D. Chronotype, cognitive abilities, and academic achievement: a meta-analytic investigation. Learning and Individual Differences. 2011;21(5):483–492. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ni Y, Wu L, Jiang J, Yang T, Wang Z, Ma L, Zheng L, Yang X, Wu Z, Fu Z. Late-night eating-induced physiological dysregulation and circadian misalignment are accompanied by microbial dysbiosis. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2019;63(24):e1900867. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wehrens S M T, Christou S, Isherwood C, Middleton B, Gibbs M A, Archer S N, Skene D J, Johnston J D. Meal timing regulates the human circadian system. Current Biology. 2017;27(12):1768–1775.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi L, Liu Y, Jiang T, Yan P, Cao F, Chen Y, Wei H, Liu J. Relationship between mental health, the CLOCK gene, and sleep quality in surgical nurses: a cross-sectional study. BioMed Research International, 2020, 4795763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kim H Y, Seo K, Jeon H J, Lee U, Lee H. Application of functional near-infrared spectroscopy to the study of brain function in humans and animal models. Molecules and Cells. 2017;40(8):523–532. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huettel S A, Song A W, McCarthy G. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boas D A, Brooks D H, Miller E L, DiMarzio C A, Kilmer M, Gaudette R J, Zhang Q. Imaging the body with diffuse optical tomography. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 2001;18(6):57–75. doi: 10.1109/79.962278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niedermeyer E, da Silva F H L. Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson J R. Cognitive Psychology and Its Implications. New York: Worth Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen R A, Sparling-Cohen Y A, O’Donnell B F. The Neuropsychology of Attention. New York: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graw P, Kräuchi K, Knoblauch V, Wirz-Justice A, Cajochen C. Circadian and wake-dependent modulation of fastest and slowest reaction times during the psychomotor vigilance task. Physiology & Behavior. 2004;80(5):695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim J, Dinges D F. Sleep deprivation and vigilant attention. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1129(1):305–322. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folkard S. Diurnal variation in logical reasoning. British Journal of Psychology. 1975;66(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1975.tb01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen R A. Neural mechanisms of attention. In: Cohen R A, Sparling-Cohen Y A, O’Donnell B F, editors. The Neuropsychology of Attention. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 211–264. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturm W, Willmes K. On the functional neuroanatomy of intrinsic and phasic alertness. NeuroImage. 2001;14(1Pt2):S76–S84. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gazzaley A, Rissman J, Cooney J, Rutman A, Seibert T, Clapp W, D’Esposito M. Functional interactions between prefrontal and visual association cortex contribute to top-down modulation of visual processing. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17(Suppl 1):i125–i135. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morecraft R J, Geula C, Mesulam M M. Architecture of connectivity within a cingulo-fronto-parietal neurocognitive network for directed attention. Archives of Neurology. 1993;50(3):279–284. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540030045013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soshi T, Kuriyama K, Aritake S, Enomoto M, Hida A, Tamura M, Kim Y, Mishima K. Sleep deprivation influences diurnal variation of human time perception with prefrontal activity change: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valdez P, Ramírez C, García A, Talamantes J, Armijo P, Borrani J. Circadian rhythms in components of attention. Biological Rhythm Research. 2005;36(1–2):57–65. doi: 10.1080/09291010400028633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riley M. Musical Listening in the German Enlightenment: Attention, Wonder and Astonishment. London: Taylor & Francis; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matchock R L, Mordkoff J T. Chronotype and time-of-day influences on the alerting, orienting, and executive components of attention. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;192(2):189–198. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicholls C, Bruno R, Matthews A. Chronic cannabis use and ERP correlates of visual selective attention during the performance of a flanker go/nogo task. Biological Psychology. 2015;110:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valdez P, Ramírez C, García A, Talamantes J, Cortez J. Circadian and homeostatic variation in sustained attention. Chronobiology International. 2010;27(2):393–416. doi: 10.3109/07420521003765861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson S W, North R A. Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12(2):483–488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrier J, Monk T H. Circadian rhythms of performance: new trends. Chronobiology International. 2000;17(6):719–732. doi: 10.1081/CBI-100102108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright K P, Jr., Hull J T, Czeisler C A. Relationship between alertness, performance, and body temperature in humans. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2002;283(6):R1370–R1377. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00205.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonnefond A, Rohmer O, Hoeft A, Muzet A, Tassi P. Interaction of age with time of day and mental load in different cognitive tasks. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2003;96(3Pt2):1223–1236. doi: 10.2466/pms.2003.96.3c.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babkoff H, Caspy T, Mikulincer M, Sing H C. Monotonic and rhythmic influences: a challenge for sleep deprivation research. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;109(3):411–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sagaspe P, Sanchez-Ortuno M, Charles A, Taillard J, Valtat C, Bioulac B, Philip P. Effects of sleep deprivation on Color-Word, Emotional, and Specific Stroop interference and on self-reported anxiety. Brain and Cognition. 2006;60(1):76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krishnan H C, Lyons L C. Synchrony and desynchrony in circadian clocks: impacts on learning and memory. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.) 2015;22(9):426–437. doi: 10.1101/lm.038877.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dinges D F, Pack F, Williams K, Gillen K A, Powell J W, Ott G E, Aptowicz C, Pack A I. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4–5 hours per night. Sleep. 1997;20(4):267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillberg M, Åkerstedt T. Sleep loss and performance: no “safe” duration of a monotonous task. Physiology & Behavior. 1998;64(5):599–604. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(98)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCarthy M E, Waters W F. Decreased attentional responsivity during sleep deprivation: orienting response latency, amplitude, and habituation. Sleep. 1997;20(2):115–123. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Gennaro L, Ferrara M, Curcio G, Bertini M. Visual search performance across 40 h of continuous wakefulness: Measures of speed and accuracy and relation with oculomotor performance. Physiology & Behavior. 2001;74(1–2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(01)00551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chee Y L, Crawford J C, Watson H G, Greaves M. Guidelines on the assessment of bleeding risk prior to surgery or invasive procedures. British Journal of Haematology. 2008;140(5):496–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drummond SPA, Brown G G. The effects of total sleep deprivation on cerebral responses to cognitive performance. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(5 Suppl 1):S68–S73. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomasi D, Wang R L, Telang F, Boronikolas V, Jayne M C, Wang G J, Fowler J S, Volkow N D. Impairment of attentional networks after 1 night of sleep deprivation. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(1):233–240. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chee M W L, Goh C S F, Namburi P, Parimal S, Seidl K N, Kastner S. Effects of sleep deprivation on cortical activation during directed attention in the absence and presence of visual stimuli. NeuroImage. 2011;58(2):595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Havas J A, Parimal S, Soon C S, Chee M W. Sleep deprivation reduces default mode network connectivity and anti-correlation during rest and task performance. NeuroImage. 2012;59(2):1745–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muto V, Jaspar M, Meyer C, Kussé C, Chellappa S L, Degueldre C, Balteau E, Shaffii-Le Bourdiec A, Luxen A, Middleton B, Archer S N, Phillips C, Collette F, Vandewalle G, Dijk D J, Maquet P. Local modulation of human brain responses by circadian rhythmicity and sleep debt. Science. 2016;353(6300):687–690. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyake A, Shah P. Models of Working Memory: Mechanisms of Active Maintenance and Executive Control. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. p. 506. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baddeley A. The fractionation of working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(24):13468–13472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Awh E, Jonides J, Smith E E, Buxton R B, Frank L R, Love T, Wong E C, Gmeindl L. Rehearsal in spatial working memory: evidence from neuroimaging. Psychological Science. 1999;10(5):433–437. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stern C E, Sherman S J, Kirchhoff B A, Hasselmo M E. Medial temporal and prefrontal contributions to working memory tasks with novel and familiar stimuli. Hippocampus. 2001;11(4):337–346. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McDowell S, Whyte J, D’Esposito M. Working memory impairments in traumatic brain injury: evidence from a dual-task paradigm. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35(10):1341–1353. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(97)00082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerstner J R, Yin J C P. Circadian rhythms and memory formation. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2010;11(8):577–588. doi: 10.1038/nrn2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Domagalik A, Oginska H, Beldzik E, Fafrowicz M, Pokrywka M, Chaniecki P, Marek T. Long-term reduction of short wavelength light affects sustained attention and visuospatial working memory. bioRxiv, 2019, 581314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Laird D A. Relative performance of college students as conditioned by time of day and day of week. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1925;8(1):50–63. doi: 10.1037/h0067673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vedhara K, Hyde J, Gilchrist I D, Tytherleigh M, Plummer S. Acute stress, memory, attention and cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(6):535–549. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Potter P, Wolf L, Boxerman S, Grayson D, Sledge J, Dunagan C, Evanoff B. Understanding the cognitive work of nursing in the acute care environment. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2005;35(7–8):327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blake M JF. Time of day effects on performance in a range of tasks. Psychonomic Science. 1967;9(6):349–350. doi: 10.3758/BF03327842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rowe G, Hasher L, Turcotte J. Age and synchrony effects in visuospatial working memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2009;62(10):1873–1880. doi: 10.1080/17470210902834852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Folkard S. Time of day and level of processing. Memory & Cognition. 1979;7(4):247–252. doi: 10.3758/BF03197596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewandowska K, Wachowicz B, Marek T, Oginska H, Fafrowicz M. Would you say “yes” in the evening? Time-of-day effect on response bias in four types of working memory recognition tasks. Chronobiology International. 2018;35(1):80–89. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1386666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chee M W L, Choo W C. Functional imaging of working memory after 24 hr of total sleep deprivation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(19):4560–4567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0007-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choo W C, Lee W W, Venkatraman V, Sheu F S, Chee M W. Dissociation of cortical regions modulated by both working memory load and sleep deprivation and by sleep deprivation alone. NeuroImage. 2005;25(2):579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mu Q, Mishory A, Johnson K A, Nahas Z, Kozel F A, Yamanaka K, Bohning D E, George M S. Decreased brain activation during a working memory task at rested baseline is associated with vulnerability to sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2005;28(4):433–448. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chee M W L, Chuah L Y M, Venkatraman V, Chan W Y, Philip P, Dinges D F. Functional imaging of working memory following normal sleep and after 24 and 35 h of sleep deprivation: Correlations of fronto-parietal activation with performance. NeuroImage. 2006;31(1):419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lim J, Choo W C, Chee M W L. Reproducibility of changes in behaviour and fMRI activation associated with sleep deprivation in a working memory task. Sleep (Basel) 2007;30(1):61–70. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Honma M, Soshi T, Kim Y, Kuriyama K. Right prefrontal activity reflects the ability to overcome sleepiness during working memory tasks: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McKenna B S, Eyler L T. Overlapping prefrontal systems involved in cognitive and emotional processing in euthymic bipolar disorder and following sleep deprivation: a review of functional neuroimaging studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(7):650–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas R J, Rosen B R, Stern C E, Weiss J W, Kwong K K. Functional imaging of working memory in obstructive sleep-disordered breathing. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;98(6):2226–2234. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01225.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McKenna B S, Sutherland A N, Legenkaya A P, Eyler L T. Abnormalities of brain response during encoding into verbal working memory among euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2014;16(3):289–299. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Drummond S P A, Walker M, Almklov E, Campos M, Anderson D E, Straus L D. Neural correlates of working memory performance in primary insomnia. Sleep (Basel) 2013;36(9):1307–1316. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stroop J R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General. 1992;121(1):15–23. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.121.1.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hartley L R, Shirley E. Color-name interference at different times of day. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1976;61(1):119–122. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.61.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manly T, Lewis G H, Robertson IH, Watson P C, Datta A. Coffee in the cornflakes: time-of-day as a modulator of executive response control. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(01)00086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harrison Y, Jones K, Waterhouse J. The influence of time awake and circadian rhythm upon performance on a frontal lobe task. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(8):1966–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bratzke D, Steinborn M B, Rolke B, Ulrich R. Effects of sleep loss and circadian rhythm on executive inhibitory control in the Stroop and Simon tasks. Chronobiology International. 2012;29(1):55–61. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.635235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schmidt C, Peigneux P, Leclercq Y, Sterpenich V, Vandewalle G, Phillips C, Berthomier P, Berthomier C, Tinguely G, Gais S, Schabus M, Desseilles M, Dang-Vu T, Salmon E, Degueldre C, Balteau E, Luxen A, Cajochen C, Maquet P, Collette F. Circadian preference modulates the neural substrate of conflict processing across the day. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miller E K, Cohen J D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24(1):167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dove A, Pollmann S, Schubert T, Wiggins C J, von Cramon D Y. Prefrontal cortex activation in task switching: an event-related fMRI study. Brain Research. Cognitive Brain Research. 2000;9(1):103–109. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6410(99)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Heuer H, Kleinsorge T, Klein W, Kohlisch O. Total sleep deprivation increases the costs of shifting between simple cognitive tasks. Acta Psychologica. 2004;117(1):29–64. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bratzke D, Rolke B, Steinborn M B, Ulrich R. The effect of 40 h constant wakefulness on task-switching efficiency. Journal of Sleep Research. 2009;18(2):167–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shinkai S, Watanabe S, Kurokawa Y, Torii J. Salivary cortisol for monitoring circadian rhythm variation in adrenal activity during shiftwork. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 1993;64(7):499–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00381098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ramírez C, García A, Valdez P. Identification of circadian rhythms in cognitive inhibition and flexibility using a Stroop task. Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 2012;10(2):136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2012.00540.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mednick S A. The associative basis of the creative process. Psychological Review. 1962;69(3):220–232. doi: 10.1037/h0048850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sherman S M, Mumford J A, Schnyer D M. Hippocampal activity mediates the relationship between circadian activity rhythms and memory in older adults. Neuropsychologia. 2015;75:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.May C P. Synchrony effects in cognition: the costs and a benefit. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1999;6(1):142–147. doi: 10.3758/BF03210822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wieth M B, Zacks R T. Time of day effects on problem solving: When the non-optimal is optimal. Thinking & Reasoning. 2011;17(4):387–401. doi: 10.1080/13546783.2011.625663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.West R, Murphy K J, Armilio M L, Craik F I, Stuss D T. Effects of time of day on age differences in working memory. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(1):3–10. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.P3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lu F M, Yuan Z. PET/SPECT molecular imaging in clinical neuroscience: recent advances in the investigation of CNS diseases. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery. 2015;5(3):433–447. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.03.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen B, Moreland J, Zhang J. Human brain functional MRI and DTI visualization with virtual reality. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery. 2011;1(1):11–16. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2011.11.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]