Abstract

In the present study, Tricholoma giganteum AGHP laccase was immobilized on amino-functionalized cadmium oxide nanoparticles (CdO NPs) which was carried out by glutaraldehyde. The synthesized CdO NPs were characterized by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDXA) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis which reflected the NPs had an average size of 35 nm with hexagonal and irregular shapes. Fourier transform infra-red (FTIR) study of laccase with amino-functionalized CdO (lac-CdO) NPs confirmed the crosslinking of laccase with CdO NPs. With immobilized laccase, a shift in pH (5.5) and temperature (35 ℃) optima was observed, when compared to free laccase (pH 4.5, 30 ℃). Lac-CdO NPs displayed 1.15 times higher stability (90 ± 0.47%) than free laccase (78 ± 0.69%) at optimum pH of 5.5. Immobilized laccase showed 1.19-fold improvement in thermal stability and 2.25-fold increment in half-life after 3 h of incubation at 50 ℃ as compared to free laccase. Recycling capability study demonstrated that lac-CdO NPs were able to retain 85 ± 0.68% of relative activity at the end of 20th 2,2-azinobis-3-ethylbenzthiozoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) oxidation cycle. In addition, lac-CdO NPs showed remarkable reusability in catalysing various organic synthesis reactions even after several cycle of catalysis. Furthermore, the interactions of organic synthesis reactions and interacted residues were observed by assessing the molecular docking poses of T. giganteum laccase with substrates. The obtained results would be advantageous to develop a biocatalyst over a chemical catalyst for effective synthesis of potent organics having industrial importance.

Keywords: Laccase, Fungi, Organic synthesis, CdO nanoparticles, Molecular docking

Introduction

Nowadays, the interest in utilization of laccase has grown significantly for vivid industrial applications including bioremediation, lignin valorisation, organic synthesis, biosensor development, etc. (Huang et al. 2022; Khatami et al. 2022; Vignali et al. 2022). This increased utilization of enzyme for industrial processes requires large amount of cost-effective production of enzyme (Mohammadi et al. 2022; Victorino da Silva Amatto et al. 2022). Moreover, industries demand enzyme with increased shelf-life, reusability and stability for commercialization of any bioprocess. In this context, the use of free enzymes is hindered by certain limitations, such as instability in presence of organic solvents, sensitivity to environmental changes and they also are difficult to recover from the end products (Zahirinejad et al. 2021). To eliminate these shortcomings, immobilization of biocatalyst is a widely adopted technique which provides significant improvement in its properties. Immobilization technology has been proved to be a favourable approach from industrial point of view, as it ensures efficient reusability of enzymes for batch processes (Gao et al. 2022). As a result of immobilization procedure, enzymes often get stable and thus prevent loss of activity under harsh environmental conditions (Sheldon 2016; Meena et al. 2021).

Enzyme immobilization can be achieved employing various techniques like physical adsorption, covalent bonding, or cross-linking (chemical immobilization) and entrapment of enzymes. Immobilization by physical adsorption is achieved by either electrostatic interaction or van der Waals force (Gao et al. 2022). This is considered as comparatively weak bonding consequently, leading to detachment of enzyme from solid support (Sassolas et al. 2012). Therefore, covalent bonding or cross-linking is a widely adopted method as it offers strong bonding thereby and enhances the operational stability of enzymes (Hou et al. 2014). The cross-linking or covalent bonding between enzyme and support usually occurs using bi/multifunctional reagents (glutaraldehyde, hexamethylene diisocyanate, etc.) (Gahlout et al. 2017). The covalent binding of enzymes with support occurs due to their side-chain amino acids and degree of reactivity based on functional group and can be achieved with different support materials like mesoporous silica, metallic NPs, metal-oxide NPs, etc. (Datta et al. 2013). In the field of enzyme immobilization, Sakai et al. (2010) reported cross-linking of enzymes to electrospun nanofibres has shown greater reusability and stability.

Micro- and Nano- sized support materials are being using for covalent binding of laccase; however, NPs are more efficient as they are having large surface to volume ratio. So, various metal oxide NPs were being chemically and biologically synthesized by various researchers to support the enzymes and to apply for various applications (Jain et al. 2010; Borhade et al. 2015; Olga et al. 2022). Examples of metal NPs include divalent metal cations such as Au+2, Ti+2, Cd+2, Cu+2, Zn+2, Ni+2, Co+2 or Mn+2. Moreover, the synthesis of metallic NPs has been advanced not only for their use as a support for immobilization of enzyme but also because of their direct utility in many biotechnological applications (Thovhogi et al. 2016; Olga et al. 2022).

Therefore, we employed CdO NPs for laccase immobilization as our previous work suggested that Tricholoma giganteum AGHP laccase was more stable in presence of 100 mM Cd as compared to other metal salts for longer time (> 100 h). Immobilized lac-CdO NPs was further characterized structurally, functionally and bio-chemically. Furthermore, synthesized lac-CdO NPs was employed as a biocatalyst for synthesis of various organic molecules such as 1,4-naphthoquinone, substituted amino naphthoquinones, resveratrol dimer, etc. These chemicals have anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities (Cichewicz and Kouzi 2002; Witayakran and Ragauskas 2007). Utilization of laccase-immobilized CdO NPs over chemical catalyst for organic synthesis was to synthesize all these industrially important chemicals using “green route” under mild conditions. In addition, detailed re-usability studies were carried out to check the effectiveness of biocatalyst. Molecular docking studies were also carried out to understand the interacted amino acid residues with organic molecules during synthesis.

Materials and methods

Laccases

Purification of laccase was carried out from Tricholoma giganteum AGHP (GeneBank: KT154749) using gel permeation and ion exchange chromatography. Large scale of the enzyme is produced using solid-state fermentation using wheat straw as a substrate (Patel and Gupte 2016). For bioinformatics studies, PDB structure of laccase was taken from Tricholoma giganteum AGDR1 (GeneBank: KT154007) as it resembles highest identity with Tricholoma giganteum AGHP (Rudakiya et al. 2020).

Chemicals

ABTS, guaiacol and 3-aminopropyl triethoxy-silane (APTES) were purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA. Glutaraldehyde and all the metal salts used were procured from Hi-Media Laboratories, Mumbai, India. All other chemicals used were of analytical grade and of highest purity available.

Synthesis of CdO NPs

CdO NPs were synthesized according to the method described by Kahane et al. (2013). For synthesis of CdO NPs, 0.4 g NaOH pellets were dissolved in 100 mL methanol then 1.0 mL ethylene glycol was added by stirring it for 1 h. Simultaneously, CdCl2 solution was prepared by dissolving 0.4 g of CdCl2 in 20 mL of methanol/water mixture (1:1 v/v). After 1 h of stirring, CdCl2 solution was added drop wise into NaOH solution under constant stirring for 3 h. Obtained precipitates were separated by centrifugation followed by washing with water and methanol. At the end of reaction, obtained white precipitates were calcinated at 300 °C for 5 h, resulting in the formation of brown colored CdO NPs. CdO NPs obtained was characterized by FTIR spectroscopy and TEM analysis.

Immobilization of CdO NPs with laccase

Laccase was amino-functionalized using glutaraldehyde using method described by Gahlout et al. (2017). To CdO NPs (100 mg), 4.0 mL of ethanol was added and incubated at 30° in static condition for 24 h. After incubation period, solution was centrifuged (8000 rpm, 10 min), CdO NPs were then modified by adding APTES (600 µL) and incubating with vigorous stirring at 30 °C for 20 h. Later, to the amino-functionalized pellet of NPs 600 µL of glutaraldehyde (25% v/v) was added and it was further incubated overnight at 30 °C under shaking condition (150 rpm). In subsequent step, centrifugation was done (8000 rpm, 10 min) and glutaraldehyde solution was then drained off followed by washing of pellet of NPs thrice with Na-acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5).

Furthermore, glutaraldehyde-activated CdO NPs (100 mg) were incubated with different concentration of purified laccase (20–500 µg/mL) at 4 °C for 12 h to optimize the concentration of laccase to be immobilized on NPs. The immobilized laccase CdO NPs were then washed thrice by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 10 min) with Na-acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5) and characterized through microscopic and spectroscopic techniques.

Immobilization yield

Immobilization yield of lac-CdO NPs was calculated for different concentration of laccase as described below (Huang et al. 2006):

where PB is Protein bound to NPs, and PU is Protein utilized for immobilization.

The amount of protein bound to NPs was calculated indirectly by estimating protein concentration presented in the washing solution (Lowry et al. 1951).

Laccase assay

Determination of laccase activity was carried out using the method developed by Niku-Paavola et al. (1990), wherein oxidation of ABTS was evaluated in presence of Na-acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 4.5/5.5) at 420 nm by performing time dependent enzyme assay for 3 min. One unit of laccase was defined as the amount of 1 µM of ABTS oxidized per minute under standard reaction condition.

Structural and functional characterization

The size and shape of CdO NPs was determined under TEM, Tecnai T20 (Philips). The presence of cadmium (Cd) and oxygen (O) in the synthesized NPs was confirmed by EDAX, Nano Nova SEM 450 (USA). Crystalline nature of CdO NPs was determined by XRD, Philips Xpert MPD (Holland) and furthermore, crystalline size of CdO NPs was calculated by Debye–Scherrer formula. The formation of CdO NPs and the interaction of laccase with amino-functionalized CdO (Lac-CdO NPs) were studied using FTIR, Spectrum GX, Perkin Elmer (USA) in mid-infrared light region of 400–4000 cm−1.

Biochemical characterization

pH and temperature optima and stability

Effect of different temperatures ranging from 20 ℃ to 70 ℃ and different pH ranging from 3.0 to 10.0 was carried out after 30 min, 24 h, and 48 h using ABTS substrate for free laccase and lac-CdO NPs to evaluate the stability of enzyme in free form and in immobilized form. Relative activity for individual time was calculated and represented in form of contour plot to understand the behavior of enzyme at different pH and temperature at same time (Rudakiya et al. 2020).

Reusability and storage stability

Reusability of lac-CdO NPs was determined by monitoring the oxidation of ABTS under standard assay conditions, according to the methodology described by Gahlout et al. (2017). Reusability was checked up to 20 cycles and after each cycle lac-CdO NPs was washed twice with Na-acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 5.5) and utilized for the subsequent cycles. The storage stability was checked by incubating free laccase and lac-CdO NPs at 4 ℃ for up to 6 weeks followed by periodic determination of residual laccase activity under standard assay conditions.

Kinetic studies

Kinetic constants of free laccase and lac-CdO NPs were determined using different concentration of ABTS (0.5–50 mM) by performing standard assay. Km and Vmax values were calculated using a Lineweaver–Burk plot (Palmer and Bonner 2007):

A straight line is produced from plotting against . Its slope, ordinate intercept and abscissa intercept are , , respectively.

Organic synthesis using free laccase and laccase immobilized CdO NPs

In this study, we mainly emphasized on the oxidative C–N, C–S, and C–C bond formation reactions using free laccase (pH 4.5, 30 ℃) and lac-CdO NPs (pH 5.5, 35 ℃) as a catalyst. Briefly, synthesis of individual products is described as follows:

1,4-naphthoquinone synthesis

In a 100-mL conical flask, 1-naphthol in acetone (0.1 g/mL) was mixed with TEMPO (0.1 g) and ethyl acetate (EtOAc) (1.0 mL). To this solution, laccase or lac-CdO NPs (500 U/mg) and Na-acetate buffer (7.0 mL, 10 mM) were added. The reaction mixture was incubated at optimum temperature with stirring at 180 rpm for 6 h. Product formation was monitored using GC–MS analysis.

Amino naphthoquinone synthesis

In a 100-mL conical flask, laccase or lac-CdO NPs (1000 U/mg) was added to a mixture of 1,4-naphthoquine (0.1 g), respective amine (0.63 mmol), EtOAc (1.5 mL) and Na-acetate buffer (7.5 mL, 10 mM). The reaction mixture was incubated at optimum temperature under continuous shaking at 180 rpm. After 12 h of reaction period more laccase or lac-CdO NPs (1000 U/mg) was added in all the reactions. Product formation was monitored using HR-LC/MS analysis.

2,5-bis(phenylsulfonyl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione synthesis

In a 100-mL conical flask, hydroquinone (0.1 g) and benzene sulfinic acid sodium salt (1.81 mmol) was dissolved in 2.0 mL of distilled water. To this laccase or lac-CdO NPs (1200 U/mg) and Na-acetate buffer (7.0 mL, 10 mM) was added and the reaction mixture was incubated at optimum temperature under continuous shaking at 180 rpm for 6 h. Product formation was monitored using LC–MS analysis.

Trans-resveratrol dimer synthesis

In 100 mL conical flask, laccase or lac-CdO NPs (1000 U/mg) was added to a biphasic solution of resveratrol (0.1 g) dissolved in 2.0 mL of EtOAc and sodium acetate buffer (6.5 mL, 10 mM). The biphasic system was further incubated at optimum temperature with continuous stirring at 120 rpm for 24 h. Product formation was monitored using LC–MS analysis.

Reusability of CdO NPs in synthesis of organic compounds

Lac-Cdo NPs has been used to catalyze synthesis of 1,4-naphthoquinone (500 U/mg), amino naphthoquinone (1000 U/mg), 2,5-bis(phenylsulfonyl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione (1200 U/mg) and trans-resveratrol dimer (1000 U/mg), under optimized pH (5.5) and temperature (35 °C) conditions, followed by determining the product yield after completion of reaction, as described in above section. For all the synthesis reactions, control reaction was carried out using only CdO NPs and results showed that no desired products were obtained in absence of laccase. Also, after each cycle lac-CdO NPs was washed twice with buffer and then utilized for another reaction cycle.

Molecular docking studies

3D structure of laccase from Tricholoma giganteum AGDR1 was used as protein structure because of similarity observed in Tricholoma giganteum AGDR1 and Tricholoma giganteum AGHP is 99.995% based on phylogeny. All substrates/chemicals used for organic synthesis were retrieved from the NCBI PubChem database. All ligands were downloaded in.sdf format which were optimized and converted in 3D structure using UCSF Chimera and AutoDockTools. Furthermore, docking studies were carried out using command prompt via AutoDock Vina software wherein binding energy and docked poses were obtained which was observed through Discovery Studio and Pymol tools (Rudakiya et al. 2019, 2020). All docking studies were carried out for three times to obtain binding energy and to confirm the same binding pose and enzyme–substrate binding site.

Results and discussion

Effect of laccase concentration on cross-linking with CdO NPs

The cross-linking reaction primarily involves addition of amino groups on the surface of CdO NPs during their reaction with APTES. Amino groups presented on CdO NPs then attach to laccase on one side and glutaraldehyde on the other side via amine group of its peripheral lysine residues. The IY for cross-linking of various concentrations of laccase with CdO NPs is as shown in Fig. 1. Results indicated that with increase in protein concentration, IY increased with maximum yield (90 ± 0.47%) obtained when 200 µg/mL of protein was cross-linked with 100 mg of CdO NPs.

Fig. 1.

Immobilization of various concentrations of laccase on CdO NPs functionally activated with glutaraldehyde which is reflected by immobilization yield (%) and optimal immobilization with respect to the optimal protein concentration and highest laccase activity (U/mL)

Maximum laccase activity was 6534 U/mL was detected when 200 µg/mL of protein was immobilized. At higher protein concentration, the formation of dense protein layer on the surface of NPs creates a stearic hindrance and diffusion barrier for the enzyme to bind to the immobilization carrier thereby, resulting in surface saturation and thus, low immobilization yield (Gahlout et al. 2017). Similar results have been reported by Patel et al. (2014) wherein maximum yield of 75.8% was attained at an optimal laccase concentration of 100 mg/g of SiO2 NPs and further increase in protein concentration led to decrease in yield. Hou et al. (2014) stated binding yield of 40% when 5.1 µg of laccase was immobilized per mg of APTES modified TiO2 NPs.

Structural and functional characterization

Synthesis of CdO and lac-CdO NPs was confirmed using microscopic, spectroscopic, and diffractometric techniques. TEM micrographs of CdO NPs displayed different size of it (18–50 nm) at 200 nm scale and are found to be hexagonal shape with smooth surface (Fig. 2a). Some large NPs are also found to be of irregular shape with smooth surface. EDAX spectrum showed only the presence of Cd (3.15 and 3.45 keV) and O (0.52 keV) peaks, thereby confirming the absence of other impurities among the prepared CdO NPs (Fig. 2b). Weight (%) of elements Cd and O was found to be 88.72 and 47.17%, respectively. XRD pattern exhibited the prominent peaks at 2ϴ values of 33.06, 38.35, 55.35, 66.01 and 69.32 (Fig. 2c). The size of CdO NPs calculated using Debye–Scherrer’s equation at different position is 29.85, 30.30, 32.32, 43.94 and 39.74 nm. Average crystalline size calculated of all relative intense peaks was found to be 35.23 nm.

Fig. 2.

TEM micrographs (a), EDAX spectrum (b), XRD pattern (c), FTIR spectrum (d) of CdO NPs and immobilization of laccase was confirmed by FTIR spectrum (d)

FTIR spectrum from the resulting CdO NPs after calcination at 300 ℃ was recorded in wavelength region of 400–4000 cm−1. As depicted in Fig. 2d, two relatively intense absorptions centered at 3441.59 and 1632.18 cm−1 are associated with standard O–H stretching of water molecules and H–O-H bending vibrations, respectively. These O–H and H–O–H modes could be related to surface adsorbed water or atmospheric water vapor. The peaks around 1000 cm−1 are useful in understanding the metal-oxide (M–O) bonding. The relatively broad peak at 1114.46 cm−1 and less intense peaks located at 524.64, 506.26 and 463.89 cm−1 represent the Cd–O stretching modes (Thema et al. 2015). FTIR spectrum of lac-CdO NPs showed change in absorption shift due to cross-linking of laccase with CdO NPs. The relatively intense peak at 2923.45 and 2852.85 cm−1 corresponds to the C-H asymmetric and C-H symmetric stretching vibrations, respectively, confirming cross-linking of laccase with CdO NPs by glutaraldehyde molecule (Gahlout et al. 2017). The peaks at 1636.89 and 1560.01 cm−1 are responsible for the C=O group, amide I group and amide II group stretching vibrations of laccase, respectively. The absorption, centered at 1464.65 cm−1, is related to C-H deformation of –CH2 or –CH3 in glutaraldehyde. Moreover, the peak at 1068.53 cm−1 showed the presence of C=O group present in glutaraldehyde (Mohajershojaei et al. 2015). However, the relatively broad peak in region of 800 to 400 cm−1 represents the Cd–O stretching modes.

Temperature and pH optima and stability

The temperature and pH dependent activity and stability of free laccase and lac-CdO NPs was studied in a temperature range of 20–70 ℃ & pH range of 3.0–10.0. Figure 3a, b reveals that temperature and pH directly influenced the oxidation of ABTS by free laccase and lac-CdO NPs. The activity of free laccase increased gradually with rise in temperature and optimal activity was obtained at 30 °C. However, lac-CdO NPs exhibited maximum enzyme activity at optimum temperature of 35 ℃. The shift in optimum temperature with increased enzyme activities towards higher value may be attributed to physical limitation of the microenvironment of nano-carriers as well as requirement of higher activation energy for the enzyme and substrate to reach the transition state (Kara et al. 2006; Bayramoğlu et al. 2010). Moreover, the higher extent of cross-linking between biocatalyst and amino-functionalized nano-carriers may also enhance the conformational rigidity of laccase which in turn prevented the enzyme from any damage at elevated temperature (Kim et al. 2010).

Fig. 3.

Effect of pH and temperature on relative activity (%) of purified laccase (a, c, e) and lac-CdO NPs (b, d, f) after 30 min (a, b), 24 h (c, d), and 48 h (e, f)

The pH optima for oxidation of ABTS using free laccase and lac-CdO NPs were found to be 4.5 and 5.5, respectively. This shift in optimum pH observed with lac-CdO NPs is attributed to the electrostatic interactions between nano-carriers and biocatalyst which affects the microenvironment of laccase (Bayramoğlu et al. 2010). Further increase in pH towards alkaline range leads to the reduction in laccase activity with a relative activity of 30 ± 0.91% (free laccase) and 58 ± 0.26% (lac-CdO NPs) at pH 9.0 and optimum temperature of 30 ℃ and 35 ℃, respectively after 30 min.

Results of temperature and pH stability profile revealed that, after 24 h, more than 70 ± 0.32% of laccase activity was retained in temperature range of 20–30 ℃ and pH range of 4.0–6.0 with free laccase. However, with lac-CdO NPs relative activity of more than 70 ± 0.58% was observed in temperature range of 20–45 ℃ and pH range of 3.5–7.0 (Fig. 3c, d). Moreover, as depicted in Fig. 3e, f after 48 h of incubation; more than 35 ± 0.49% of initial laccase activity was obtained in temperature and pH range of 20–35 ℃ and 3.5–6.5, respectively. Whereas lac-CdO NPs showed more than 35 ± 0.87% relative laccase activity in temperature range of 20–40 ℃ and pH 3.0–7.0. This improvement in pH stability is due to the cross-linking of laccase to CdO NPs which guards the enzyme from the pH induced conformational changes, thereby increasing resistance to the acidic and alkaline conditions (Jaiswal et al. 2016). Similarly, the laccase conjugated fumed silica NPs of Coriolopsis polyzona exhibited higher pH optima (pH 7.0) as compared to the free laccase that showed optimal activity at pH 5.0 (Hommes et al. 2012). Overall results indicated good temperature and pH stability of lac-CdO NPs as compared to free laccase which can be observed in Fig. 3, wherein lac-CdO NPs displayed more than 35% relative activity in temperature and pH range of 20–35 ℃ and 3.5–6.5, respectively, after 48 h. The possible explanation for this can be the favorable environment provided by the nano-carriers to maintain enzyme activity, which could be attributed to the covalent binding interaction between laccase and CdO NPs; protecting laccase from direct exposure to environmental instabilities (Zhu et al. 2007).

Reusability and storage stability of lac-CdO NPs

The reusability of immobilized biocatalyst is an important aspect for its industrial applications, as it reduces the operational cost of any bioprocess. Therefore, the recycling capability of lac-CdO NPs for oxidation of ABTS was determined up to 20 subsequent cycles at 35 ℃. The results attained demonstrated that 95 ± 0.70% of laccase activity was retained till 12th cycle. In subsequent cycles, the laccase activity slightly decreased and almost 90 ± 1.07% of enzyme activity was observed till 15th cycle. However, at the end of 20th ABTS oxidation cycle, lac-CdO NPs retained almost 85 ± 0.69% of its initial enzyme activity (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Reusability of lac-CdO nanoparticles (a) and storage stabilities of free laccase and lac-CdO nanoparticles at 4 ℃ (b)

Liu et al. (2012) reported in his study that only 50% of initial enzyme activity was recorded for laccase immobilized on CMCC after 10 cycles of ABTS oxidation. In contrast, after 8 successive ABTS oxidation cycles, agar–agar, polyacrylamide, and gelatin entrapped laccases displayed residual activities of 24.8, 28.3 and 22.8%, respectively (Asgher et al. 2017). Several other studies also reported on better reusability of immobilized laccase for oxidation of different substrates (Qiu et al. 2008; Makas et al. 2010; Pang et al. 2016). Thus, the overall results of the present study depicts that cross-linking of laccase with amino-functionalized CdO NPs imparted remarkable tolerance to the laccase even after 20 successive substrate-oxidation cycles, which is in line with the report of Gahlout et al. (2017).

Storage stabilities were determined by keeping free laccase and lac-CdO NPs at 4 °C for up to 6 weeks and the remaining laccase activity is as shown in Fig. 4b. The results showed that lac-CdO NPs retained 62 ± 0.65% of its initial enzyme activity after 6 weeks of incubation at 4 ℃. However, free laccase could retain only 33 ± 0.87% enzyme activity under similar incubation condition. The prolonged stability of enzyme indicated that immobilization procedure prevented laccase from complete inactivation, thereby demonstrating their utilization as an industrial biocatalyst. In confirmatory to our results, Gahlout et al. (2017) also reported that activity of free laccase decreased faster as compared to laccase cross-linked with nanosilica. Xu et al. (2015) also documented higher storage stability for laccase covalently immobilized on PVA/CS/MWNTs membrane retaining 80% enzyme activity in comparison to its free counterpart (30%) after 4 weeks of incubation at 4 ℃.

Determination of kinetics parameters

The apparent kinetic constants (Km and Vmax) of free laccase and lac-CdO NPs for oxidation of ABTS were calculated from Lineweaver–Burk plot using different ABTS concentrations. The apparent Km value for lac-CdO nanoparticles was 0.12 ± 0.009 mM which was 2.4 times higher than free laccase (0.05 ± 0.002 mM), demonstrating loss of affinity of enzyme for substrate. In comparison to binding affinity, Vmax of lac-CdO NPs drastically decreased by 6 times from 12,195 ± 104 to 2000 ± 291 µM/mL/min. This change in Km and Vmax exhibited by lac-CdO NPs is probably because of the mass-transfer and diffusion limitations of the substrate after immobilization, subsequently dropping the substrate accessibility to the part of active immobilized enzyme (Ardao et al. 2011). Results obtained are comparable with those described for laccase immobilized over multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) with higher Km and lower Vmax values for oxidation of ABTS than free laccase (Tavares et al. 2015). In contrast, Pang et al. (2016) in his study described higher affinity of immobilized laccase (Km = 0.217) for ABTS than free laccase (Km = 0.330), giving a possible explanation of structural changes that occurred in the laccase as a result of immobilization procedure.

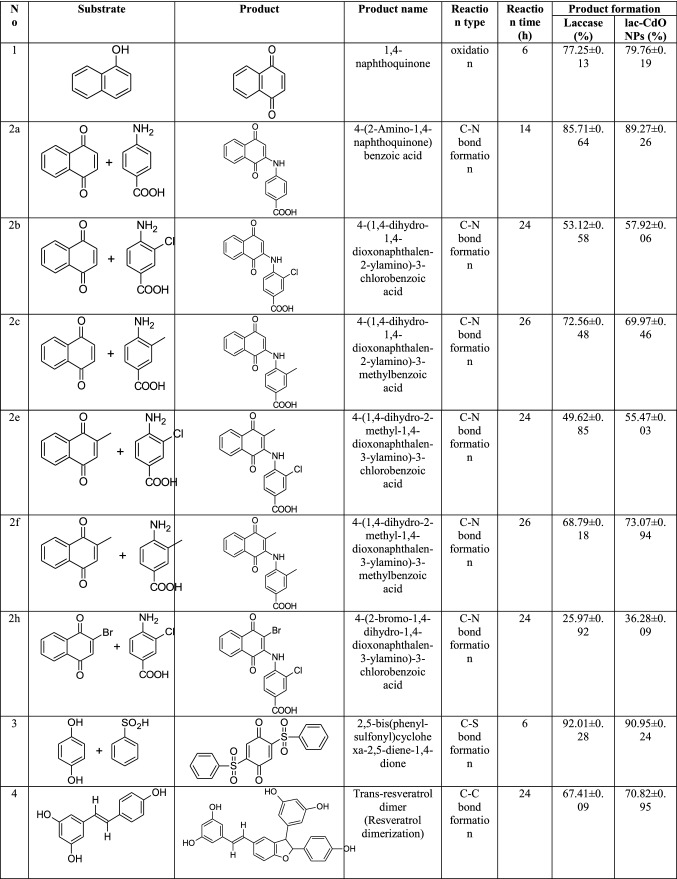

Organic synthesis by free laccase and lac-CdO NPs

The present study is mainly focused on the oxidative C–N, C–S and C–C bond formation catalyzed by laccase and lac-CdO NPs. Table 1 shows the detailed reactions of each compound which was carried out using free laccase and lac-CdO NPs, including substrates and products. It also includes the production yield obtained after reaction from the free laccase and lac-CdO NPs. To catalyze various organic synthesis reactions, optimized concentration of free laccase & lac-CdO NPs were used to attain the maximum yield of product.

Table 1.

Organic synthesis using free laccase and lac-CdO NPs carried out in this study

Reusability of lac-CdO NPs in synthesis of organic compounds

The reusability of laccase cross-linked CdO NPs was investigated by monitoring the yield of various organic compounds synthesized up to 20 consecutive reaction cycles. The % yield of synthesized product obtained during each reaction cycle is an indication of the biocatalytic efficiency of lac-CdO NPs.

1,4-naphthoquinone synthesis

In case of synthesis of 1,4-naphthoquinone (1), 79 ± 0.19% yield was attained after 1st catalytic cycle; thereafter, no significant decrease in yield of 1,4-naphthoquinone was observed till 7th cycle (70 ± 0.59%) (Fig. 5a). In subsequent cycles, the yield of 1,4-naphthoquine decreased and almost 61 ± 0.95% yield was obtained after 10th reaction cycle. However, at the end of 15th catalytic cycle yield decreased drastically to 26 ± 0.04%. Later, consistent decrease in yield of 1,4-naphthoquinone was observed and it reached to 8.5 ± 0.06% after 18th cycle.

Fig. 5.

Reusability of lac-CdO nanoparticles in synthesis of 1,4-naphthoquinone (a), and 4-(2-Amino-1,4-naphthoquinone) benzoic acid (2a) 4-(1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid (2b), 4-(1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-ylamino)-3-methylbenzoic acid (2c), 4-(1,4-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid (2e), 4-(1,4-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-methylbenzoic acid (2f), 4-(2-bromo-1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid (2 h) (b)

Amino naphthoquinone synthesis

The synthesis of amino naphthoquinones using lac-CdO nanoparticles was carried out at 35 ℃ under constant stirring at 180 rpm for desired reaction period. During synthesis of amino naphthoquinones (Fig. 5b), after 1st cycle of reaction the highest yield of 89 ± 0.26% was obtained for 2a (4-(2-Amino-1,4-naphthoquinone) benzoic acid) after 14 h of reaction period per cycle followed by 2c (4-(1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-ylamino)-3-methyl-benzoic acid) (69 ± 0.46%) and 2f (4-(1,4-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-methyl-benzoic acid) (73 ± 0.94%) after 26 h of incubation for each cycle. However, at the end of 1st cycle of reaction the yield obtained for 2b (4-(1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-ylamino)-3-chloro-benzoic acid) (57 ± 0.06%), 2e (4-(1,4-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-chloro-benzoic acid) (55 ± 0.03%) and 2 h (4-(2-bromo-1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-chloro-benzoic acid) (36 ± 0.09%) was comparatively low even after 24 h of reaction period per cycle. After 5 subsequent cycles the yield obtained for 2a, 2c and 2f was 87 ± 0.49%, 66 ± 0.22% and 70 ± 0.81%, respectively. In contrast, the yield obtained for 2b and 2e decreased to almost 50 ± 0.24% and 29 ± 0.64% for 2 h.

After 10 catalytic cycles, a significant decrease in yield of all the synthesized amino naphthoquinones was observed except for 2 h, as during the synthesis of 2 h lac-CdO nanoparticles were unable to catalyze the reaction after 9th cycle attributing to the loss of immobilized laccase activity in presence of halides. The yield attained was 80 ± 0.54, 25 ± 0.24, 50 ± 0.67, 15 ± 0.13 and 53 ± 0.87% for 2a, 2b, 2c, 2e and 2f, respectively. Moreover, the synthesis of 2b, 2e and 2f was stopped after 13, 11 and 14 catalytic cycles, respectively. Nevertheless, synthesis of 2a and 2c was stopped after 16 subsequent cycles with a yield of 38 ± 0.34% and 6 ± 0.05%, respectively, thereby indicating complete loss of immobilized laccase activity after certain reaction period.

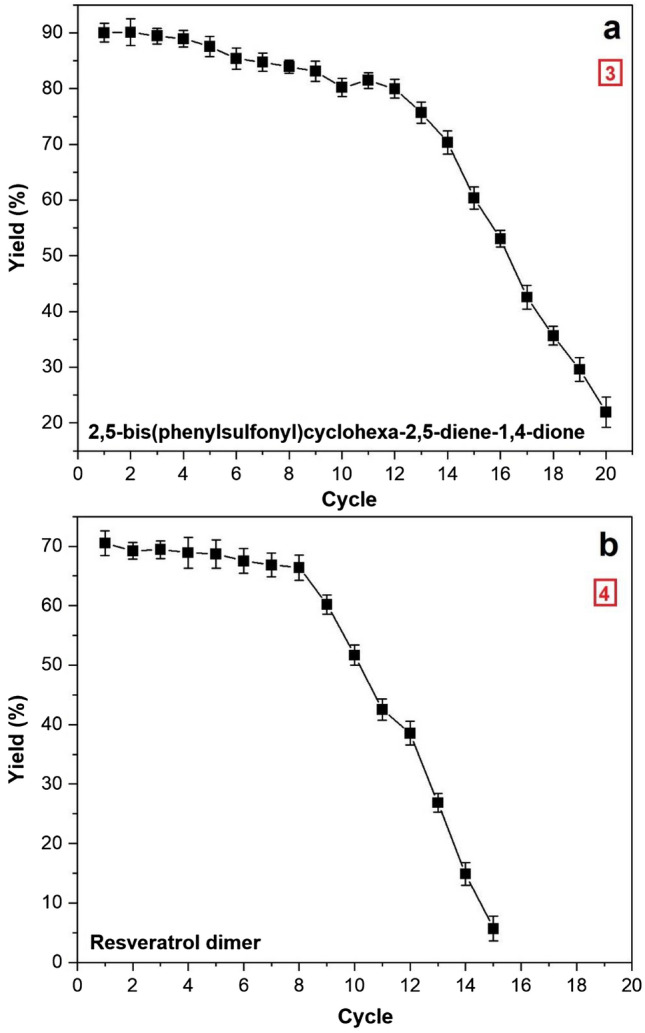

2,5-bis(phenylsulfonyl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione synthesis

Laccase cross-linked with CdO nanoparticles was also utilized for catalyzing the cross-coupling reaction between p-hydroquinone and benzene sulfinic acid for synthesis of C–S coupling product at 35 ℃ under continuous stirring at 180 rpm. After 1st catalytic cycle of 6 h, 90 ± 0.24% yield of 2,5-bis(phenylsulfonyl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione (3) was obtained. The product yield reduced marginally by 10% after 10 catalytic cycles (80 ± 0.68%). Furthermore, as reaction cycle increases the product yield decreased significantly with yield of 21 ± 0.96% at the end of 20 reaction cycles (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Reusability of lac-CdO nanoparticles in synthesis of 2,5-bis(phenyl-sulfonyl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione (a), and trans-resveratrol dimer (b)

Trans-resveratrol dimer synthesis

The reusability of lac-CdO nanoparticles for catalyzing the dimerization of trans-resveratrol was determined up to 15 cycles at 35 ℃ for desired reaction period. 70 ± 0.95% yield of dimer product (4) was attained after completion of 1st reaction cycle which reduced to 51 ± 0.78% after 10 subsequent cycles (Fig. 6b). Later, remarkable decrease in yield was observed giving only 5.69 ± 0.081% dimer product after completing 15 reaction cycles.

The role of laccase in catalyzing various organic synthesis reactions is that of an oxidant. In case of synthesis of 1,4-naphthoquinone, single-step oxidation of 1-naphthol was achieved using laccase to yield 1,4-naphthoquinone. Further, synthesis of various amino naphthoquinones achieved via laccase-catalyzed oxidation is advantageous over chemical catalysts. Lisboa and co-workers (2011) adapted a synthetic route for oxidative coupling of 1,4-naphthoquinones with amines. The typical reaction was catalyzed by cupric acetate in acetic acid at 60–70 ℃ to form aminonaphthoquinones. In another study of Chakraborty et al. (1998), nuclear amination of 1,4-benzohydroquinone with primary amines was achieved by primarily halogenating 1,4-benzohydroquinone and coupling it to primary amine using palladium catalyst and phosphine ligand under argon reflux in subsequent step. During this chemical catalysis process, chemical oxidants like silver (I) oxide, sodium iodate and cupric acetate were used. In the present investigation, we have thus eliminated the use of cupric acetate acid catalysis at elevated temperature in the previous approach, and the use of chemical oxidants, halogenated intermediates, palladium catalyst and triphenylphosphine ligand in the later one.

C–S bond formation via chemical route is likely to occur under stringent extreme reaction conditions. Yamamoto and Sekine (1984) report on condensation of thiols with alkyl halides in a copper-catalyzed dehydrogenation reaction occurring at 200 ℃ in presence of polar solvent hexamethylphosphoramide. Another investigation reports on requirement of 90 ℃ temperature for catalyzing C–S coupling of iodobenzene and thiophenol by a chemical catalyst graphene oxide supported Ni nanoparticles in presence of K2CO3 base and DMF solvent (Rana et al. 2022). Therefore, the use of laccase-catalyzed C–S bond formation reported in the current work holds an advantage of requiring milder reaction conditions and an aqueous environment. In the current study, laccase-catalyzed synthesis of trans-resveratrol dimer was successfully carried out under mild reaction conditions. However, in contrast to our study, literature reports on oxidative coupling of trans-resveratrol by subjecting trans-resveratrol to purple LED (410 nm) irradiation with mesoporous graphite carbon nitride (mpg-C3N4) as a catalyst and simultaneous bubbling of solvent (acetonitrile) with air (Song et al. 2014). In another study, resveratrol analogs were subjected to oligomerization in presence of one-electron metal oxidants (AgOAc, CuBr2, FeCl3·6H2O, FeCl3·6H2O/NaI, PbO2, VOF3) and solvents (toluene, xylene, diethyl ether, etc.) (Velu et al. 2008). The present investigation thus paves benefit over use of multiple chemical oxidants for synthesis of trans-resveratrol dimer, proving capability of laccase in catalyzing oxidative C–C bond formation.

Literature studies reports on the synthesis of organic compounds aiding diverse immobilized chemical catalysts (Verma et al. 2011; Hudson et al. 2012). Moreover, studies have also reported the utilization of laccase-immobilized different nano-carriers for the degradation of various environmental pollutants such as pesticides, dyes, and elimination of micro-pollutants such as endocrine-disrupting chemicals from wastewater (Corvini and Shahgaldian 2010; Ji et al. 2016). However, the utilization of laccase cross-linked CdO nanoparticles for organic synthesis reactions has seldom been reported in the literature. Therefore, the reusability of lac-CdO nanoparticles used as a catalyst in organic synthesis reactions was compared with the results of reusability of chemical catalysts used for the same.

Kantam et al. (2013) utilized nanocrystalline magnesium oxide-stabilized palladium catalysts to carry out heck reaction of various heteroaryl bromides. The author reports on consistent yield of product using this catalyst for up to 4 cycles. The fresh yield obtained for three different products was between 84and 87% which decreased marginally, and yield attained was between 80 and 83% after 4 cycles. Mou et al. (2017) in his study synthesized Betti (Mannich) bases via C–C bond-forming reaction in aqueous medium by reacting 2-naphthol, substituted aldehydes and anilines using reverse ZnO nanomicelles as catalyst. Reverse ZnO nanomicelles efficiently synthesized Betti base derivatives with a yield of 95% after 1st reaction cycle which reduced to 94% after 6 reaction cycles. Thus, overall results of the present study indicated that the recycling capability exhibited by lac-CdO NPs for synthesis of various organic compounds is comparable with chemical catalysts.

Molecular docking studies

Molecular docking studies of substrates and products with enzyme revealed the binding site, binding energy, involved residues, distance between ligand and residue and type of interaction between enzyme-ligand for catalysis (Table 2). In addition, negative binding energy (KJ/mol) between substrates/products and enzyme revealed the reaction was spontaneous (Rudakiya et al. 2019). Two major binding sites of Tricholoma giganteum AGDR1 laccase were found wherein first binding site was near to the catalytic site and second site was near to helix structure observed in substrate binding site (Fig. 7). Residues observed near catalytic site were H83, H85, H199, H318, H320 and H372 which could transfer electron from substrate and involved in bond formation (Rudakiya et al. 2020).

Table 2.

Molecular docking of Tricholoma giganteum AGDR1 and products obtained from organic synthesis (Table 1) with their docking energy and interacted amino acid residues

| No | Product name | Binding energy (KJ/mol) ‡ | Binding residues (distance#; interaction type*) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,4-naphthoquinone | − 7.0 ± 0.1 | Y126 (3.45; B), R131 (3.11; A), L140 (4.89; D), S192 (2.84; A), I373 (5.16; C) |

| 2a | 4-(2-Amino-1,4-naphthoquinone) benzoic acid | − 9.1 ± 0.2 | W117 (3.82; E), Y126 (4.80; F), R131 (3.15; E), R131 (5.21; G), L140 (4.80; D), L251 (2.53; A), L251 (4.88; D), P316 (4.79; D), H372 (2.66; A), I373 (3.70; H) |

| 2b | 4-(1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid | − 9.3 ± 0.1 | W117 (3.76; E), Y126 (4.76; A), R131 (3.32; G), Q133 (3.31; A), L140 (4.92; D), D141 (4.99; I), L251 (4.85; D), P316 (5.22; D), H372 (2.43; A), I373 (3.49; H) |

| 2c | 4-(1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-ylamino)-3-methylbenzoic acid | − 9.8 ± 0.1 | W117 (5.18; D), Y126 (2.77; A), Q133 (3.24; A), L140 (4.92; D), D141 (4.84; I), L251 (4.98; D), P316 (5.23; D), H372 (2.44; A), I373 (5.23; H) |

| 2e | 4-(1,4-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid | − 9.5 ± 0.2 | W117 (3.98; E), Y126 (4.58; A), R131 (3.27; G), L140 (4.50; D), D141 (4.15; I), L251 (4.04; D), P316 (5.05; D), H372 (2.58; A), I373 (3.21; H) |

| 2f | 4-(1,4-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-methylbenzoic acid | − 9.6 ± 0.2 | W117 (3.65; E), Y126 (4.36; A), R131 (3.25; G), L140 (4.59; D), D141 (4.31; I), L251 (4.57; D), P316 (5.57; D), H372 (2.67; A), I373 (3.79; H) |

| 2 h | 4-(2-bromo-1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid | − 9.1 ± 0.3 | W117 (3.38 E), Y126 (4.23; A), R131 (3.06; G), L140 (4.70; D), D141 (4.64; I), P316 (5.25; D), H372 (2.32; A), I373 (3.56; H) |

| 3 | 2,5-bis(phenyl-sulfonyl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione | − 8.6 ± 0.1 | Y126 (3.60; B), L140 (4.80; D), S192 (2.99; A), P314 (4.34; D), P316 (4.74; D), Q345 (3.21; A), H372 (3.15; A) |

| 4 | trans-resveratrol dimer | − 9.4 ± 0.3 | T121 (2.66; A), P266 (4.88; D), F368 (3.75; C) |

#Distance is shown for each residue in parenthesis, and it is expressed in Å

*Type of interactions between ligand and enzyme: A: Conventional H-bond, B: π-donor H-bond; C: π-π T shaped, D: π-alkyl, E: attractive charge, F: C–H bond, G: π-anion, H: π-Sigma, I: Salt bridge

‡Molecular docking study of individual compounds is performed in triplicates and displayed values of binding energy is mean of triplicates with SD shown

Fig. 7.

Structural depiction of Tricholoma giganteum AGDR1 laccase and its substrate/product binding site and its catalytic site

In this work, highest binding energy with enzyme was 2c (− 9.8 kJ/mol) followed by 2f (− 9.6 kJ/mol), 2e (− 9.5 kJ/mol), trans-resveratrol dimer (− 9.4 kJ/mol), 2b (− 9.3 kJ/mol), 2a & 2 h (− 9.1 kJ/mol) and 1,4-naphthoquinone (− 7.0 kJ/mol). These results were higher as compared to the previous study conducted using different pesticides which had binding energy of − 6.3 to − 6.7 kJ/mol. Structural complexity of ligands and strong H-bond with protein show higher negative binding energy (Rudakiya et al. 2020). Figure 8 shows 2-dimensional interaction between individual ligand and enzyme with interacted residues and interaction type which is generated from Schrodinger Maestro. During organic synthesis, W117, T121, Y126, R131, L140, D141, S192, L251, P266, P316, F368, H372 and I373 were the involved residues of substrate binding site which were participated during the catalysis. In addition, Conventional H-bond, π-donor H-bond, π-alkyl, C–H bond, π-anion, π-Sigma and salt bridge were the main interactions which were involved during the catalysis. Because of R, T, Y, L, S, H and I residues, ligands formed “semi-envelop” hydrophobic region which is also confirmed by Hongyan et al. (2019).

Fig. 8.

Molecular docking analysis of laccase from Tricholoma giganteum AGDR1 and potential organic compounds which is generated in Schrodinger Maestro of 1,4-naphthoquinone (a), 4-(2-Amino-1,4-naphthoquinone) benzoic acid (b) 4-(1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid (c), 4-(1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-2-ylamino)-3-methylbenzoic acid (d), 4-(1,4-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid (e), 4-(1,4-dihydro-2-methyl-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-methylbenzoic acid (f), 4-(2-bromo-1,4-dihydro-1,4-dioxonaphthalen-3-ylamino)-3-chlorobenzoic acid (g), 2,5-bis(phenyl-sulfonyl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione (h), and trans-resveratrol dimer (i)

Overall, molecular docking study confirmed the binding of various organic compounds with laccase and found the potential amino acid residues involved during catalysis. During the catalysis, Tyr, Trp, Arg, Lys, Ser, Pro, Thr, Cys and His are mostly involved residues presented at substrate binding site and catalytic site. Most of the ligand interactions are less than 5 Å which shows strong interaction with ligands.

Conclusion

The current study reports covalent immobilization of purified T. giganteum AGHP laccase on amino-functionalized CdO NPs. Biochemical characterization of lac-CdO NPs revealed a better relative and residual activity profiles in acidic and basic pH and high-temperature ranges, with improved storage stability as compared to free form. Lac-CdO NPs has potential to synthesize 1,4-naphthoquinone, various amino-naphthoquinones, 2,5-bis(phenyl-sulfonyl)cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione, and trans-resveratrol dimer. Furthermore, it exhibited noticeable reusability for the synthesis of these organics even after 10 successive batches, which is remarkable for a biocatalyst. In addition, molecular docking study revealed the involved amino acid residues and type of interactions observed during organic synthesis which provided the structural insight of enzyme-ligand. To the best of our knowledge, still very few reports exist that highlight the role of laccase-immobilized CdO NPs for organic synthesis reactions. Thus, lac-CdO NPs would provide a sustainable alternate over chemical catalyst, proving its imperative role as a green catalyst for organic synthesis and can be efficiently utilized for other potential biotechnological and environmental applications.

Acknowledgements

The authors also wish to acknowledge SICART, V.V. Nagar, Gujarat, for providing the necessary instrumentation facilities.

Abbreviations

- ABTS

2,2-Azinobis-3-ethylbenzthiozoline-6-sulfonic acid

- CdO NPs

Cadmium oxide nanoparticles

- lac-CdO NPs

Laccase amino-functionalized CdO NPs

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- EDXA

Energy dispersive x-ray analysis

- FTIR

Fourier-transform infra-red spectroscopy

- XRD

X-ray diffraction

Author contributions

Conceptualization: HP, AG. Formal analysis and investigation: HP, DR. Writing-Original draft preparation: HP, DR. Supervision: AG.

Funding

The authors are thankful to the Department of Biotechnology (DBT sanction no. BT/PR5859/PID/6/696/2012) and Ministry of Science and Technology, New Delhi, for their financial support.

Availability of data and material

Data and required material will be provided on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Helina Patel, Email: hpatel712@gmail.com.

Darshan M. Rudakiya, Email: darshan.rudakiya@hotmail.com

Akshaya Gupte, Email: Akshaya_gupte@hotmail.com.

References

- Ardao I, Alvaro G, Benaiges MD. Reversible immobilization of rhamnulose-1-phosphate aldolase for biocatalysis: enzyme loading optimization and aldol addition kinetic modeling. Biochem Eng J. 2011;56(3):190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2011.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asgher M, Noreen S, Bilal M. Enhancement of catalytic, reusability, and long-term stability features of Trametes versicolor IBL-04 laccase immobilized on different polymers. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;95:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayramoğlu G, Yilmaz M, Arica MY. Reversible immobilization of laccase to poly (4-vinylpyridine) grafted and Cu (II) chelated magnetic beads: biodegradation of reactive dyes. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101(17):6615–6621. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borhade AV, Uphade BK, Gadhave AG. Efficient, solvent-free synthesis of acridinediones catalyzed by CdO nanoparticles. Res Chem Intermediat. 2015;41(3):1447–1458. doi: 10.1007/s11164-013-1284-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty M, McConville D, Niu Y, Tessier C, Youngs W. Reactions of primary and secondary amines with substituted hydroquinones: nuclear amination, side-chain amination, and indolequinone formation. J Org Chem. 1998;63:7563. doi: 10.1021/jo980541v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichewicz RH, Kouzi SA. Resveratrol oligomers: structure, chemistry, and biological activity. Stud Nat Prod Chem. 2002;26:507–579. doi: 10.1016/S1572-5995(02)80014-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corvini PF, Shahgaldian P. LANCE: Laccase-nanoparticle conjugates for the elimination of micropollutants (endocrine disrupting chemicals) from wastewater in bioreactors. Rev Environ Sci Bio. 2010;9(1):23–27. doi: 10.1007/s11157-009-9182-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva V, Amatto I, Gonsales da Rosa-Garzon N, de Oliveira A, Simoes F, Santiago F, da Silva P, Leite N, Raspante Martins J, Cabral H. Enzyme engineering and its industrial applications. Biotechnol Appl Bioc. 2022;69(2):389–409. doi: 10.1002/bab.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Christena LR, Rajaram YRS. Enzyme immobilization: an overview on techniques and support materials. 3 Biotech. 2013;3(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13205-012-0071-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahlout M, Rudakiya DM, Gupte S, Gupte A. Laccase-conjugated amino-functionalized nanosilica for efficient degradation of Reactive Violet 1 dye. Int Nano Lett. 2017;7(3):195–208. doi: 10.1007/s40089-017-0215-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Shah K, Kwok I, Wang M, Rome LH, Mahendra S. Immobilized fungal enzymes: innovations and potential applications in biodegradation and biosynthesis. Biotechnol Adv. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.107936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommes G, Gasser CA, Howald CB, Goers R, Schlosser D, Shahgaldian P, Corvini PF-X. Production of a robust nanobiocatalyst for municipal wastewater treatment. Bioresource Technol. 2012;115:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongyan L, Zexiong Z, Shiwei X, He X, Yinian Z, Haiyun L, Zhongsheng Y. Study on transformation and degradation of bisphenol A by Trametes versicolor laccase and simulation of molecular docking. Chemosphere. 2019;224:743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J, Dong G, Ye Y, Chen V. Laccase immobilization on titania nanoparticles and titania-functionalized membranes. J Membrane Sci. 2014;452:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2013.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Xiao H, Li B, Wang J, Jiang D. Immobilization of Pycnoporus sanguineus laccase on copper tetra-aminophthalocyanine–Fe3O4 nanoparticle composite. Biotechnology Appl Bioc. 2006;44(2):93–100. doi: 10.1042/BA20050213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Zhang W, Gan Y, Yang J, Zhang S. Laccase immobilization with metal-organic frameworks: current status, remaining challenges and future perspectives. Crit Rev Env Sci Tech. 2022;52(8):1282–1324. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2020.1854565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R, Li C-J, Moores A. Magnetic copper–iron nanoparticles as simple heterogeneous catalysts for the azide–alkyne click reaction in water. Green Chem. 2012;14(3):622–624. doi: 10.1039/C2GC16421C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain D, Kachhwaha S, Jain R, Srivastava G, Kothari SL. Novel microbial route to synthesize silver nanoparticles using spore crystal mixture of Bacillus thuringiensis. Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48(11):1152–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal N, Pandey VP, Dwivedi UN. Immobilization of papaya laccase in chitosan led to improved multipronged stability and dye discoloration. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;86:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Hou J, Chen V. Cross-linked carbon nanotubes-based biocatalytic membranes for micro-pollutants degradation: performance, stability, and regeneration. J Membrane Sci. 2016;520:869–880. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.08.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahane SV, Sasikala R, Vishwanadh B, Sudarsan V, Mahamuni S. CdO–CdS nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic activity for hydrogen generation from water. Int J Hydrogen Energ. 2013;38(35):15012–15018. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.09.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kantam ML, Redddy PV, Srinivas P, Venugopal A, Bhargava S, Nishina Y. Nanocrystalline magnesium oxide-stabilized palladium (0): the Heck reaction of heteroaryl bromides in the absence of additional ligands and base. Cat Sci Tec. 2013;3(10):2550–2554. doi: 10.1039/C3CY00404J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kara F, Demirel G, Tümtürk H. Immobilization of urease by using chitosan–alginate and poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid)/κ-carrageenan supports. Bioproc Biosyst Eng. 2006;29(3):207–211. doi: 10.1007/s00449-006-0073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatami SH, Vakili O, Movahedpour A, Ghesmati Z, Ghasemi H, Taheri-Anganeh M. Laccase: various types and applications. Biotechnol Appl Bioc. 2022 doi: 10.1002/bab.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Park JM, Um HJ, Lee DH, Lee KH, Kobayashi F, Iwasaka Y, Hong CS, Min J, Kim YH. Immobilization of cross-linked lipase aggregates onto magnetic beads for enzymatic degradation of polycaprolactone. J Basic Microb. 2010;50(3):218–226. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200900099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa CS, Santos VG, Vaz BG, Lucas NC, et al. C-H functionalization of 1,4-naphthoquinone by oxidative coupling with anilines in the presence of a catalytic quantity of copper (II) acetate. J Org Chem. 2011;76:5264–5273. doi: 10.1021/jo200354u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zeng Z, Zeng G, Tang L, Pang Y, Li Z, Liu C, Lei X, Wu M, Ren P. Immobilization of laccase on magnetic bimodal mesoporous carbon and the application in the removal of phenolic compounds. Bioresource Technol. 2012;115:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall R. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makas YG, Kalkan NA, Aksoy S, Altinok H, Hasirci N. Immobilization of laccase in κ-carrageenan based semi-interpenetrating polymer networks. J Biotechnol. 2010;148(4):216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meena J, Gupta A, Ahuja R, Singh M, Panda AK. Recent advances in nano-engineered approaches used for enzyme immobilization with enhanced activity. J Mol Liq. 2021;338:116602. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohajershojaei K, Mahmoodi NM, Khosravi A. Immobilization of laccase enzyme onto titania nanoparticle and decolorization of dyes from single and binary systems. Biotechnol Bioproc E. 2015;20(1):109–116. doi: 10.1007/s12257-014-0196-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi ZB, Zhang F, Kharazmi MS, Jafari SM. Nano-biocatalysts for food applications; immobilized enzymes within different nanostructures. Crit Rev Food Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2092719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou J, Gao G, Chen C, Liu J, Gao J, Liu Y, Pei D. Highly efficient one-pot three-component Betti reaction in water using reverse zinc oxide micelles as a recoverable and reusable catalyst. RSC Adv. 2017;7(23):13868–13875. doi: 10.1039/C6RA28599F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niku-Paavola M-L, Karhunen E, Kantelinen A, Viikari L, Lundell T, Hatakka A. The effect of culture conditions on the production of lignin modifying enzymes by the white-rot fungus Phlebia radiata. J Biotechnol. 1990;13(2–3):211–221. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(90)90106-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olga M, Jana M, Anna M, Irena K, Jan M, Alena Č. Antimicrobial properties and applications of metal nanoparticles biosynthesized by green methods. Biotechnol Adv. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.107905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer T, Bonner PL. Enzymes: biochemistry, biotechnology, clinical chemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pang S, Wu Y, Zhang X, Li B, Ouyang J, Ding M. Immobilization of laccase via adsorption onto bimodal mesoporous Zr-MOF. Process Biochem. 2016;51(2):229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2015.11.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel H, Gupte A. Optimization of different culture conditions for enhanced laccase production and its purification from Tricholoma giganteum AGHP. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2016;3(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40643-016-0088-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SK, Kalia VC, Choi JH, Haw JR, Kim IW, Lee JK. Immobilization of laccase on SiO2 nanocarriers improves its stability and reusability. J Microbiol Biotechn. 2014;24(5):639–647. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1401.01025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Xu C, Huang X, Ding Y, Qu Y, Gao P. Adsorption of laccase on the surface of nanoporous gold and the direct electron transfer between them. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112(38):14781–14785. doi: 10.1021/jp805600k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rana S, Velázquez JJ, Jonnalagadda SB. Highly active reduced graphene oxide supported Ni nanoparticles for C-S coupling reactions. Nanoscale Adv. 2022;4(15):3131–3135. doi: 10.1039/D2NA00316C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudakiya DM, Patel SH, Narra M. Structural insight into the fungal β-glucosidases and their interactions with organics. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;138:1019–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudakiya DM, Patel DH, Gupte A. Exploiting the potential of metal and solvent tolerant laccase from Tricholoma giganteum AGDR1 for the removal of pesticides. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;144:586–595. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S, Liu Y, Yamaguchi T, Watanabe R, Kawabe M, Kawakami K. Immobilization of Pseudomonas cepacia lipase onto electrospun polyacrylonitrile fibers through physical adsorption and application to transesterification in nonaqueous solvent. Biotechnol Lett. 2010;32(8):1059–1062. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassolas A, Blum LJ, Leca-Bouvier BD. Immobilization strategies to develop enzymatic biosensors. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30(3):489–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA. Engineering a more sustainable world through catalysis and green chemistry. J Roy Soc Interface. 2016;13(116):20160087. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2016.0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song T, Zhou B, Peng GW, Zhang QB, Wu LZ, Liu Q, Wang Y. Aerobic oxidative coupling of resveratrol and its analogues by visible light using mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (mpg-C3N4) as a bioinspired catalyst. Chem Eur J. 2014;20(3):678–682. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares AP, Silva CG, Dražić G, Silva AM, Loureiro JM, Faria JL. Laccase immobilization over multi-walled carbon nanotubes: kinetic, thermodynamic and stability studies. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2015;454:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thema F, Beukes P, Gurib-Fakim A, Maaza M. Green synthesis of Monteponite CdO nanoparticles by Agathosma betulina natural extract. J Alloy Compd. 2015;646:1043–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.05.279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thovhogi N, Park E, Manikandan E, Maaza M, Gurib-Fakim A. Physical properties of CdO nanoparticles synthesized by green chemistry via Hibiscus Sabdariffa flower extract. J Alloy Compd. 2016;655:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.09.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velu SS, Buniyamin I, Ching LK, Feroz F, Noorbatcha I, Gee LC, et al. Regio-and stereoselective biomimetic synthesis of oligostilbenoid dimers from resveratrol analogues: influence of the solvent, oxidant, and substitution. Chem Eur J. 2008;14(36):11376–11384. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Mungse HP, Kumar N, Choudhary S, Jain SL, Sain B, Khatri OP. Graphene oxide: an efficient and reusable carbocatalyst for aza-Michael addition of amines to activated alkenes. Chem Commun. 2011;47(47):12673–12675. doi: 10.1039/C1CC15230K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignali E, Gigli M, Cailotto S, Pollegioni L, Rosini E, Crestini C. The laccase lig multienzymatic multistep system in lignin valorization. Chemsuschem. 2022 doi: 10.1002/cssc.202201147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witayakran S, Ragauskas AJ. One-pot synthesis of 1,4-naphthoquinones and related structures with laccase. Green Chem. 2007;9:475–480. doi: 10.1039/B606686K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, Tang R, Zhou Q, Li F, Zhang B. Enhancement of catalytic activity of immobilized laccase for diclofenac biodegradation by carbon nanotubes. Chem Eng J. 2015;262:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.09.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Sekine Y. Condensation of thiophenols with aryl halides using metallic copper as a reactant. Intermediation of cuprous thiophenolates. Can J Chem. 1984;62(8):1544–1547. doi: 10.1139/v84-263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zahirinejad S, Hemmati R, Homaei A, Dinari A, Hosseinkhani S, Mohammadi S, Vianello F. Nano-organic supports for enzyme immobilization: scopes and perspectives. Colloid Surf B. 2021;204:111774. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Kaskel S, Shi J, Wage T, van Pée K-H. Immobilization of Trametes versicolor laccase on magnetically separable mesoporous silica spheres. Chem Mater. 2007;19(26):6408–6413. doi: 10.1021/cm071265g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and required material will be provided on request.