Summary

Background:

Exposure to food advertisements is associated with poor diet among youth, and food and beverage companies are increasingly advertising on social media sites that are popular among youth.

Objective:

To identify the prevalence of social media advertising among fast food, beverage, and snack companies and examine advertising techniques they use on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and Vine.

Methods:

We quantified the increase in the creation of social media accounts from 2007 to 2016 among 200 fast food, beverage, and snack brands from the United States. We conducted content analyses to examine the marketing themes and healthfulness of products featured in 2000 posts from a subset of 20 brands and used multilevel regression to assess associations between marketing themes (eg, adolescents socializing) and interactive tools (eg, hashtags).

Results:

Two hundred brands collectively managed 568 accounts in 2016. Content analyses revealed that unique social media features (eg, geo-tags) appeared in 74.5% (n = 1489) of posts, and 31.5% (n = 630) were interactive. Posts featuring adolescents were more likely to be interactive than posts featuring adults (P < 0.001). Two-thirds (67.9%; n = 362) of foods shown were unhealthy, and 61.2% (n = 435) of beverages were sugar sweetened.

Conclusions:

Social media food advertising is pervasive and uses interactive tools to engage with users.

Keywords: adolescents, nutrition, social media, social media marketing

1 |. INTRODUCTION

In 2006, the National Academy of Medicine identified exposure to food advertisements as a major contributor to poor dietary habits Among youth.1 Companies spend $1.8 billion annually promoting mostly unhealthy products to youth,2 and children and adolescents see several thousand food commercials on television each year.2 During lab studies, children who view food advertisements consume more calories than those who view non-food advertisements.1 In response to concerns about the influence of food advertisements on dietary behaviours, the food industry created the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI), a voluntary pledge that aims to limit children’s exposure to unhealthy food advertisements.3 The pledge is limited, however, in that it does not focus on adolescents (ages 12 y and older) or social media advertising, even though children and adolescents are spending more time on social media.

As young people substantially increase the time they spend online4–7 and have greater access to smartphones,8 companies rely more heavily on digital outlets for advertising (eg, banner ads on websites, pop-up ads, and sponsored ads on social media). Online food advertising expenditures increased by 50.0% between 2006 and 2009 and continue to grow,9 whereas the amount of television food and beverage ads promoted to children and adolescents has remained relatively constant.10 In 2017, global social media advertising expenditures were estimated to reach $35.98 billion,11 and Coca-Cola now allocates 20.0% of their $4 billion annual ad budget to social media–based advertising.12 Social media platforms (eg, Facebook) can promote ads in two ways. First, companies can pay for ads to appear on a user’s home page. These ads include a disclaimer (eg, “sponsored”) that they are promotional. Second, companies can create a free official account that enables users to “follow” them. Adolescents represent a valuable target for social media advertising because 89.0% of adolescents ages 13 to 17 years in the United States have a social media account.13 Their potential for lifelong brand loyalty and $80 billion in annual spending power makes them a critical consumer group.14,15

Social media advertising may be uniquely effective among adolescents for several reasons. First, Social Norms Theory16 suggests social media “likes” may function as social norms indicators that capitalize on adolescents’ exquisite sensitivity to peer behaviour.17 Indeed, studies show adolescents would rather “like” posts with many rather than few “likes.”17 Further, social media is uniquely reinforcing for adolescents. A neuroimaging study showed heightened activity in the nucleus accumbens—a reward hub of the brain—among adolescents who viewed their own posts with many “likes” vs few “likes.”18 The nucleus accumbens is more sensitive to reward among adolescents compared with adults and children, and social media may function as a potent reward among adolescents.19 Finally, social media ads can be created more quickly and inexpensively than television ads, making them nimble enough to capitalize on current popular culture trends that appeal to adolescents.20 For example, Gatorade’s hashtag on Twitter during the 2013 Olympics allowed adolescent athletes and followers to share their inspirations and facilitated 11 million social media views.21,22 This type of interaction is not possible through other forms of media, making this new marketing territory worthy of further investigation.

Food companies’ use of social media accounts is newly emerging and relatively unexplored. A few studies have shown that Facebook pages that are managed by food companies promote unhealthy products23–26 and increase brand recognition among youth.27,28 But no studies have examined the landscape of social media food, beverage, and snack ads across multiple social media platforms over an extended period of time. Without such studies, it is difficult to determine the prevalence of social media–based food, beverage, and snack marketing, its growth over time, and its ability to reach youth. This study addresses those gaps by (a) quantifying the frequency of the food, beverage, and snack brands’ use of Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, and Vine over 9 years; (b) conducting a qualitative evaluation of marketing themes used on social media accounts; (c) examining the nutritional quality of products promoted on social media; and (d) determining the association between brands’ use of interactive tools and the presence of adolescents or food products in the posts.

2 |. METHODS

In 2016, we selected Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tumblr, and Vine as the social media platforms to examine in this study because they represented the top five most popular social media platforms among adolescents in 2014 to 201529 that also had official food, beverage, and snack brand accounts from the United States. We selected these three brand categories because they have the more adolescent-targeted marketing than other categories (eg, cereals).2 The following methods are outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart describing the methods for identifying brands and posts that were used in the analyses. Brands were identified by searching from the social media platform homepage for brand names, choosing an account attributed to the brand, and confirming the account as the official account by identifying the blue checkmark next to the account name given to celebrities, brands, and public figures to verify their identity

2.1 |. Descriptive characteristics of food, beverage, and snack brands on social media

We identified a sample of 200 fast food, beverage, and snack brands with the highest advertising expenditures in the United States based on rankings listed in the most comprehensive food advertising reports to date.30–32 Next, we trained 15 research assistants to use four steps to identify the official social media accounts associated with those 200 brands. First, they went online and used www.google.com to find the home page for the social media site. Then, they entered the brand name (eg, Sprite) into the search field that is available on each social media site. Next, they read the search results and looked for an account associated with the brand (eg, @Sprite). After finding an account that appeared to be associated with the brand, research assistants confirmed the account was officially associated with the brand. On Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Vine, they did so by identifying the verification badge (eg, blue or grey checkmark logo and Vine logo) next to the account name. Social media platforms provide these verification badges to celebrities, brands, or public figures after they complete an application to verify their identity. Tumblr did not have a system for validating official brand accounts, so research assistants were instructed to search for text stating “Official account of [brand]” and look for one or more other signs that it was the brand’s official Tumblr account (eg, the account included a link to the brand’s official website; all of the posts appeared to be official advertisements; there were no other accounts that appeared to be official brand accounts on that platform; other research assistants agreed it appeared to be the official account). Finally, because some brands maintain accounts that target consumers in specific countries (eg, @CocaCocaMX is official account for Coca-Cola in Mexico), the assistants checked the account name and description to ensure it was main account for the United States. At the time of data collection in January 2016, research assistants recorded the (a) social media platform name (eg, “Twitter”), (b) number of followers, (c) number of posts associated with each account, and (d) date of their first social media post. After recording these characteristics for the 200 brands, we summed each characteristic (eg, number of followers) across the five social media platforms to create social media profiles for each brand (Table 1). Finally, we plotted the increase in the creation of Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and Vine accounts between 2007 and 2016 to chart the change in social media–based food, beverage, and snack advertising over time.

TABLE 1.

Number of social media followers, posts, and accounts maintained by food, beverage, and snack brands as of January 2016, ranked by number of followers

| Brand Name | Social Media Users Who Follow the Brand on at Least One of the Five Sites |

Posts Generated by the Brand Since Joining Social Media |

Social Media Accounts Maintained by the Brand |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | |

| Coca-Cola | 101 000 000 | 12.3 | 206 457 | 1.7 | 5 |

| McDonald’s | 66 888 791 | 8.1 | 114 390 | 0.9 | 5 |

| Starbucks | 55 400 000 | 6.7 | 60 716 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Red Bull | 51 483 543 | 6.3 | 69 509 | 0.6 | 5 |

| KFC | 41 826 523 | 5.1 | 22 635 | 0.2 | 4 |

| Pepsi | 38 200 000 | 4.7 | 29 884 | 0.2 | 5 |

| Monster | 29 908 174 | 3.6 | 9 315 836 | 75.0 | 5 |

| Subway | 28 380 988 | 3.5 | 45 650 | 0.4 | 5 |

| Sprite | 21 200 000 | 2.6 | 9391 | 0.1 | 4 |

| Fanta | 17 800 000 | 2.2 | 5542 | 0.0 | 5 |

| Dr Pepper | 15 603 874 | 1.9 | 36 456 | 0.3 | 4 |

| Taco Bell | 12 955 889 | 1.6 | 570 752 | 4.6 | 5 |

| Dairy Queen | 10 761 479 | 1.3 | 21 103 | 0.2 | 5 |

| Mountain Dew | 9 270 668 | 1.1 | 27 210 | 0.2 | 4 |

| Burger King | 8 997 249 | 1.1 | 15 244 | 0.1 | 5 |

| Wendy’s | 8 900 578 | 1.1 | 67 464 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Chick-fil-A | 8 596 103 | 1.0 | 9159 | 0.1 | 5 |

| Coke Zero | 7 204 764 | 0.9 | 13 444 | 0.1 | 4 |

| Diet Coke | 2 899 831 | 0.4 | 11 677 | 0.1 | 4 |

| Coke Life | 873 851 | 0.1 | 643 | 0.0 | 3 |

| Subtotal of 20 brands abovea | 530 947 541 | 65.6 | 10 653 162 | 85.9 | 90 |

| Subtotal of 180 other brands | 282 570 033 | 34.4 | 1 757 559 | 14.1 | 477 |

| Grand total (N = 200) | 821 250 802 | 100 | 12 422 046 | 100 | 568 |

This subset of 20 brands included the following: (a) 16 brands with the highest number of followers on all social media sites were selected for in-depth analyses, and (b) in the case of The Coca-Cola Co., 4 of its brands were selected to examine the behaviors of the most marketed brand in the United States.

To identify brands for qualitative analyses, we first selected the 16 brands in our sample with the most social media followers. Then, because the Coca-Cola Company has the most highly marketed portfolio of non-alcoholic beverages in the United States,32 we added four more of their hallmark beverages: Diet Coke, Coke Life, Coke Zero, and Sprite. A separate study (in preparation) examined the differences in marketing themes used by Coca-Cola’s brands on social media. But for the present study, this subset of 20 brands made up the final sample for our qualitative analyses.

2.2 |. Qualitative analysis of marketing themes used in social media posts

After selecting 20 brands for qualitative analyses, we compiled a random sample of 2000 posts by using a random number generator to select 20 posts from each of the five social media platforms (ie, 100 screenshots of posts per brand across the five platforms). If brands had fewer than five accounts, we collected an equal number of posts from available platforms.

To evaluate the 2000 posts, we developed a codebook based on the guidelines described by Lombard and colleagues.33 Codebook items included (a) main theme (eg, holidays), (b) presence of branded product (eg, Sprite can), (c) mention of cross-promotions (eg, Super Bowl), (d) presence of interactive tools (eg, geotags), (e) attempts to interact with users (eg, “re-tweet us!”), (f) type of post (eg, video), and (g) the perceived sex of person in the post. Research assistants completed pilot coding for 10.0% of the screenshots to establish interrater reliability. Reliable raters reached a Krippendorf alpha value of at least 0.70% or 90.0% agreement33 and coded the remaining 90.0% of posts. The variable assessing the sex of the person in the post was excluded from further analyses because of low interrater reliability.

2.3 |. Associations between ad themes and the presence of interactive tools or adolescents in ads

To answer the remaining research questions, we used multilevel regression to account for brand level variability (ie, included a random intercept of brand in each model) and assessed the associations between the use of advertising themes (eg, visual portrayal of holiday imagery or adolescents socializing) and the presence of interactive tools (ie, hashtags and requests to comment) or adolescents in the posts. We estimated the age of persons in the post by asking the research assistants to code whether the main person in the post appeared to be between the ages of 12 and 17 years, 18 and older, or a child younger than age 12 years. The post was also coded as child-targeted if the words “child” or “kid” appeared in the post or if non-human characters in the post seemed to target children (eg, Tony the Tiger and other cartoons). Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4.

2.4 |. Nutritional quality of food, beverage, and snack products featured in social media post

Research assistants collected and analysed the nutritional information for all foods, beverages, and snacks shown in the 2000 posts selected for content analysis. First, they recorded the names of branded or unbranded (ie, food/beverage/snack products not sold by the brand) foods, beverages, snacks, and meals that occupied the most space in posts. Next, they collected nutrition information for branded products from the brand’s official website. They compiled nutritional information for unbranded food and snack products from the US Department of Agriculture’s National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Research assistants then entered the information for foods into the Nutrient Profile Model (NPM) to generate a score. The NPM reflects nutritionists’ evaluations of the healthfulness of foods34 and was used in similar food marketing studies.30,35 The assistants converted NPM scores to an easy-to-understand Nutrient Profile Index (NPI) ranging from 1 to 100.30 A score greater than or equal to 64 is considered healthy. Because the NPM codes many sugary beverages similarly, we did not calculate NPM scores for those products. Instead, we sorted beverages into categories outlined in the Rudd Center’s Sugary Drink FACTS Report.31

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Descriptive characteristics of food, beverage, and snack brands on social media

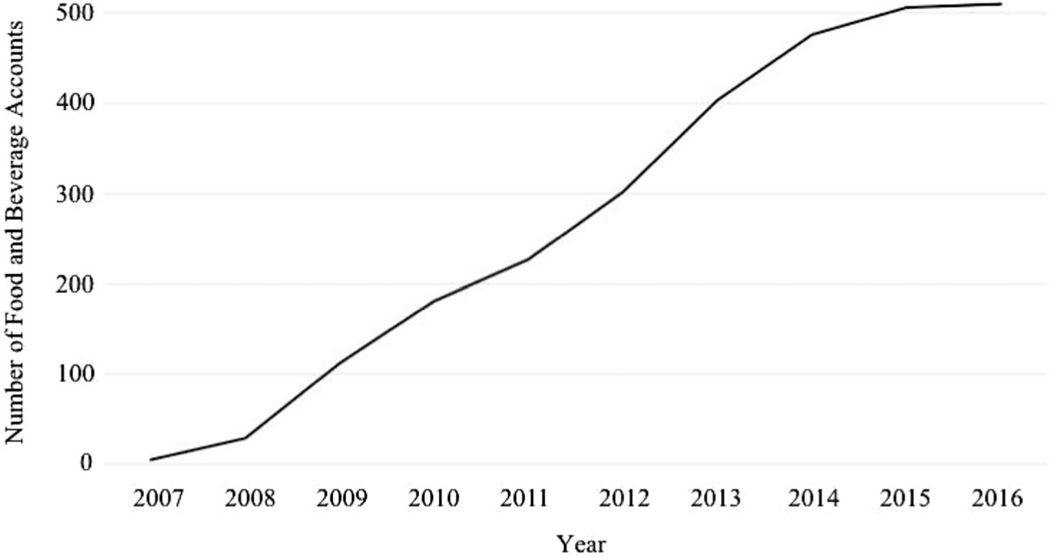

As shown in Figure 2, the data gathered by research assistants demonstrated an increase in food, beverage, and snack brands’ creation of social media accounts on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and Vine over time. They identified one social media account that was active in 2007 and 568 social media accounts that were active in 2016. During this period, the brands in our sample collectively generated 12.4 million posts across the five platforms and accumulated nearly 1 billion followers (N = 821 250 802) (Table 1). In 2016, Coca-Cola had the most followers (n = 101 000 000), and Monster Energy generated the most posts (n = 9 315 836) in the sample.

FIGURE 2.

Trend in the growth of social media account creation by food, beverage, and snack brands over time. The number of food, beverage, and snack brand accounts on five social media platforms has increased by 567% from 2007 to 2016

3.2 |. Nutritional quality of food, beverage, and snack products featured in social media posts

Nine percent (n = 533) of social media posts featured food and snack products. Some beverage brand posts did not show food, and four posts had food products where the type of food could not be identified based on the caption or the appearance of the food. The average NPI score for food and snack products featured in social media posts was 54.1 (Table 2). Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) featured unhealthy products in posts more frequently than other brands (69.4%; n = 59; average NPI = 45.5), and 99.8% of all KFC food posts featured unhealthy products. Most of the food and snack products featured in Subway’s posts were healthy (69.8%; n = 37; average NPI = 66.9). Twenty-nine percent (n = 598) of posts in the sample showed a beverage, and 61.2% of those posts featured a sugary beverage.

TABLE 2.

Nutritional quality of food, beverage, and snack products shown in the sample of 2000 social media posts from food, beverage, and snack brands

| Brand | Types of Beverages Shown in this Brand’s Posts | Number of Posts that Showed a Beverage | Percent of Beverage Posts that Showed Sugary Beverages | Average NPI Score of Food Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coke Zero | Regular soda/full calorie Diet drink (soda) |

79 | 6.0 | 74 |

| Coke Life | Reduced sugar (soda) | 66 | 0.0 | 61.7 |

| Sprite | Regular soda/full calorie | 45 | 100 | 57.6 |

| Coca Cola | Regular soda/full calorie | 81 | 100 | 45 |

| Diet Coke | Diet drink (soda) | 73 | 0 | - |

| Pepsi | Regular soda/full calorie Diet Drink (soda) |

35 | 88.0 | 36 |

| Fanta | Regular soda/full calorie | 18 | 100 | 72 |

| Dr Pepper | Regular soda/full calorie Diet drink (soda) Reduced sugar (soda) |

73 | 89.0 | 58.2 |

| Mountain Dew | Regular soda/full calorie Diet drink (soda) Fruit drink/full calorie |

75 | 99.0 | 43.5 |

| Red Bull | Energy drink/full calorie | 8 | 100 | - |

| Monster | Energy drink/full calorie | 3 | 100 | - |

| Total for beverage brands | 556 | 78.1 | 56.00 | |

| Subway | Iced tea/full-calorie Diet drink (soda) |

2 | 50.0 | 66.9 |

| McDonald’s | Full-calorie mixed drink 1% low-fat milk Coffee/full calorie |

8 | 38.0 | 52 |

| KFC | Regular soda/full calorie | 5 | 100 | 45.5 |

| Taco Bell | Slushy/full calorie Regular soda/full calorie Coffee/full calorie |

13 | 100 | 61.6 |

| Starbucks | Coffee/full calorie Tea/no calorie Coffee/full calorie |

61 | 48.0 | 45.4 |

| Dairy Queen | Regular soda/full calorie Fruit drink, full calorie Diet drink (soda) |

15 | 99.3 | 38.7 |

| Wendy’s | Regular soda/full calorie Fruit drink/full calorie Low-fat milk |

15 | 86.7 | 53.6 |

| Burger King | Full calorie/mixed drink Coffee/no calorie Regular soda/full calorie |

18 | 94.1 | 52.6 |

| Chick-fil-A Fruit drink/full calorie Full calorie/mixed drink 100% Juice/full calorie Iced tea/full calorie |

20 | 85.0 | 54.8 | |

| Total for food and snack brands | 156 | 21.9 | 52.34 | |

| Grand total for food, beverage, and snack brands | 712 | 62.4 | 54.07 | |

Abbreviation: NPI, Nutrient Profile Index.

3.3 |. Qualitative analysis of marketing themes used in social media posts

Among the 20 brands selected for in-depth qualitative analyses, we identified 90 social media accounts across the five platforms and gathered 2000 posts from those accounts. Nearly three-quarters (74.5%; n = 1489) of those posts included features that are unique to social media (eg, geotags) and 31.5% (n = 630) of posts featured attempts by food, beverage, and snack brands to interact with followers (Table 3). Nineteen percent (20.4%; n = 407) of posts featured a celebrity or cross-promotional theme (eg, Olympics). A total of 982 posts appeared to target specific age groups by portraying actors in specific age groups or cartoons that appeal to children. Research assistants perceived 6.2% (n = 61 posts) of persons pictured to be adolescents (ages 12–17 y) and 88.9% (n = 873 posts) of persons pictured to be 18 years or older.

TABLE 3.

Qualitative marketing themes identified for the sample of 2000 social media posts from food, beverage, and snack brands

| Brand Name | Social Media Features (eg, geotags) |

Interactive Tools |

Celebrity/Cross-Promotion Theme |

Holiday Theme |

Health and Fitness Theme |

Food and/or Beverages Shown |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Coke Zero | 96 | 96.0 | 37 | 37.0 | 53 | 53.0 | 11 | 11.0 | 14 | 14.0 | 13 | 13.0 |

| Coca-Cola | 93 | 93.0 | 29 | 29.0 | 16 | 16.0 | 29 | 29.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 34 | 34.0 |

| Monster | 90 | 90.0 | 37 | 37.0 | 80 | 80.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 15.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Coke Life | 90 | 90.0 | 19 | 19.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 17 | 17.0 | 9 | 9.0 | 35 | 35.0 |

| Pepsi | 88 | 87.0 | 38 | 38.0 | 57 | 57.0 | 7 | 7.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 12 | 12.0 |

| Starbucks | 87 | 87.0 | 34 | 34.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 22 | 22.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 44 | 44.0 |

| Diet Coke | 85 | 85.0 | 44 | 44.0 | 9 | 9.0 | 8 | 8.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 7 | 7.0 |

| Fanta | 80 | 80.0 | 45 | 45.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 21 | 21.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 7.0 |

| Chick-fil-A | 80 | 80.0 | 28 | 28.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 10 | 10.0 | 14 | 14.0 | 43 | 43.0 |

| Dr Pepper | 77 | 77.0 | 9 | 9.0 | 30 | 30.0 | 19 | 19.0 | 9 | 9.0 | 26 | 26.0 |

| Red Bull | 77 | 77.0 | 23 | 23.0 | 30 | 30.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 47 | 47.0 | 6 | 6.0 |

| Mountain Dew | 75 | 75.0 | 41 | 41.0 | 25 | 25.0 | 6 | 6.0 | 5 | 5.0 | 38 | 38.0 |

| Dairy Queen | 71 | 71.0 | 32 | 32.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 17 | 17.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 67 | 67.0 |

| Sprite | 69 | 69.0 | 26 | 26.0 | 34 | 34.0 | 5 | 5.0 | 6 | 6.0 | 14 | 14.0 |

| Subway | 62 | 62.0 | 25 | 25.0 | 13 | 13.0 | 10 | 10.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 47 | 47.0 |

| Taco Bell | 61 | 61.0 | 41 | 41.0 | 18 | 18.0 | 8 | 8.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 40 | 40.0 |

| McDonald’s | 60 | 60.0 | 25 | 25.0 | 14 | 14.0 | 12 | 12.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 35 | 35.0 |

| KFC | 59 | 59.0 | 24 | 24.0 | 11 | 11.0 | 20 | 20.0 | 5 | 5.0 | 38 | 38.0 |

| Burger King | 51 | 51.0 | 17 | 17.0 | 8 | 8.0 | 5 | 5.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 75 | 75.0 |

| Wendy’s | 37 | 37.0 | 56 | 56.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 70 | 70.0 |

| Total (N = 2000 posts) | 1489 | 74.5 | 630 | 31.5 | 407 | 20.4 | 230 | 11.5 | 148 | 7.4 | 182 | 9.1 |

Note. All n values in this table represent the number of posts, while percentages represent the percent of the sample.

3.4 |. Associations between the use of interactive tools and advertising themes

We examined correlations between the posts’ use of interactive tools and advertising themes that target adolescents or promote food. In our sample of 2000 posts, 31.5% (n = 630) had interactive features, but just 61 (3.1%) posts featured adolescents. Using this subset of posts featuring adolescents, we conducted analyses to determine the percentage of posts that also included interactive features. Fifty-one percent (n = 31) of the social media posts that featured adolescents (n = 61) also contained interactive tools. Posts featuring adolescents were more likely to have interactive tools than posts that featured adults (OR: 2.38, 95% CI, 1.30–4.37, P < .001; P = 0.01).

Posts that did not show any food, beverage, or snack products (n = 442) were more likely to use interactive tools (OR: 1.98, 95% CI, 1.52–2.57, P < .0001) than posts showing food, beverage, or snack products (n = 1558). Almost one-third (28.9%; n = 630) of interactive posts did not showcase food, beverage, and snack products.

4 |. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive content analysis of social media–based food, beverage, and snack advertising practices to date. We found that food, beverage, and snack companies are increasingly promoting their brands on multiple social media platforms that are popular among adolescents and young adults. These companies utilize novel social media tools in advertisements (Figures S1-S5)36,37 and feature unhealthy products in their posts. In 2016, our sample of 200 brands generated a 567% increase in their creation of Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and Vine accounts in 9 years. This striking increase in account creation, however, may simply reflect the increase in the number and popularity of social media platforms over time. For example, one report showed that use of at least one social media platform grew from 60% to 86% among adults (ie, 18–29 years) between 2007 and 2016.

Our findings reinforce previous research on social media food advertising. Most products promoted on these social media accounts were unhealthy, which is similar to findings from other food marketing studies.38,39 And the types of interactive tools (eg, contests) that were used by companies in our sample were similar to the tools identified in other social media food advertising studies.24 Finally, our data also support other studies that showed companies are skilled at generating millions of followers who “opt in” to advertising exposure by affiliating themselves with brands on social media.24,31,40,41

This study contributes to the literature on food, beverage, and snack marketing in several ways. Other social media research studies have included a smaller subset of brands,23,26,36 fewer social media platforms,26,36 or provided a narrative review of evidence or broad commentaries on public health concerns related to social media advertising.23,25,27,28 Our findings are the first to evaluate growth of brands’ social media accounts over a 9-year period and capture the variety of advertising practices companies used on five platforms over a 1-year period of time. Our data, therefore, present the most comprehensive snapshot of social media food advertising to date and can provide a roadmap for future studies aiming to examine the effects of novel promotional techniques that are unique to social media food advertising (eg, using interactive features in posts that depict adolescents).

Our content analysis contributes to the literature by revealing that these brands produce highly interactive posts, particularly in posts that feature adolescents. Although other social media studies have catalogued the interactive nature of social media food ads24,28,36our findings showed that social media–specific (eg, hashtags) and interactive tools (eg, “tag a friend”) were significantly more likely to be used in posts that featured adolescents compared to posts that featured adults. Use of these subtle advertising features demonstrates how brands mimic users’ digital behaviour in ways that enable them to blend in with the social media environment. And although we cannot determine whether companies intentionally crafted interactive tools for posts that depict adolescents, the use of these interactive techniques is a public health concern because food marketing research on Facebook shows that adolescents and young adults respond favourably to interactive content.24

Companies’ limited portrayals of food and beverage products in posts was a surprising finding with several potential implications. In contrast to other non-social media food advertising studies where products are shown in the majority of ads,43,44 71.6% (n = 1432) of posts in our sample did not show a product. The comparatively low frequency of posts that featured branded food, beverage, or snack products may be unintentional. Alternatively, companies may purposefully use more subtle and entertaining tools to engage consumers and promote their brand, which may reduce consumers’ conscious awareness of the promotional nature of posts. There are a variety of ways consumers may be affected by companies’ infrequent portrayal of food and beverages in social media posts. One possibility is that there is no difference in consumers’ responses to posts that feature food versus posts that do not feature food. But it is also possible that by excluding the products from posts, consumers may not perceive the posts as advertisements and instead interact with company posts in the same way they would with friends or other entertaining content on social media. Another potential consequence of emphasizing non-food themes may be that consumers form stronger emotional connections with the brand (ie, the content may appear more entertaining than promotional).45

Future experimental studies should examine the extent to which the subtle and uniquely interactive nature of social media food, beverage, and snack ads makes them more potent than television food ads in their ability to influence food, beverage, and snack intake and purchases among youth. One digital advertising agency, for example, surveyed 500 social media users and found that 71% reporting using hashtags on social media. Among those who use hashtags, 34% reported clicking on hashtags in posts in order to find brands, people, or posts that may be of interest to the user. A research study focused on vaping used machine learning and human coding to identify the number of posts related to the e-cigarette brand JUUL during a 3-month period and found nearly 15 000 posts generated by more than 5000 unique social media users.46 Fifty-five percent of those JUUL posts contained content related to youth (eg, “#teen”).47 The heavy use of interactive content in social media food advertising is a concern because reports show frequent social media use among youth as young as ages 8 to 12 years,4 and this age group is vulnerable to persuasive messages in food advertisements.48

This study has several limitations. Our content analysis included a limited sample of posts, meaning we could have missed some advertising themes. Our random selection of posts, however, should provide a representative overview of marketing themes utilized by each brand. Further, we were unable to discern how many of the nearly 1 billion followers that were publicly listed on the accounts might be bots (ie, non-human accounts purchased to inflate numbers of followers).49 Although posts featuring adolescents were more likely to include interactive tools than posts featuring adults, our sample contained a small number (n = 61) of posts featuring adolescents. Future studies should examine the extent to which interactive tools amplify adolescents’ interest in youth-targeted posts. Finally, when designing the study, we could not identify healthy comparison brands that could function as a control group because the vast majority of fast food and snack brands do not have healthy NPI scores for the majority of their products. Our study’s aims, however, were to examine the most heavily advertised brands, meaning we are reflecting the most popular brands.

The marked growth in social media–based marketing may greatly increase overall exposure to food, beverage, and snack ads, particularly among youth. Although no studies have comprehensively examined youth exposure to food and beverage advertising on social media, researchers in one cross-sectional study estimated ad exposure by asking 101 children and adolescents ages 7 to 16 years to screen record their activity on their favourite social media app for a 5-minute period.50 They found that 72% of participants were exposed to ads on social media during the data collection period, with the majority of ads promoting unhealthy foods and beverages. They estimated exposure to food advertisements to be between 30 and 189 instances per week, with adolescents being more likely to see food marketing compared with younger children.

In sum, our data revealed that the food, beverage, and snack industry collectively created hundreds of social media accounts between 2007 and 2016 and used interactive and novel marketing themes in their social media posts. Their massive social media presence capitalizes on everchanging popular trends. It is critical that future research examines how one-on-one interactions between users and brands influence exposure to ads, food, beverage, and snack intake and purchasing behaviours among youth. These interactive tools facilitate immediate feedback on ads from consumers, making social media a nimble advertising tool that may increase exposure to unhealthy food, beverage, and snack ads that can contribute to poor diet among adolescents and young adults.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported, in part, by an NIH Early Independence Award (DP5OD021373–01; PI: Dr. Marie Bragg) from the NIH Office of the Director. This funding source had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication. We would also like to thank the following NYU SeedProgram Research Assistants and staff who have no conflicts of interest to report: Samina Lutfeali for conducting some of the analyses, and Carola Zurob, Anne Dumadag, Alex Harvey, Alex Bragg, Erin Rhodes, Natasha Pandit, Carolyn Fan, Margaret Eby, Alexia Akbay, Eleni Papaiacovou-Lane, Lindsey Gibson, DiAnna Brice, Maimuna Marenah, Colleen Tenan, Tenay Greene, Jessica Klein, Sana Husain, Nasira Spells, Stefanie Bendik. Dana McIntyre, Ruchi Desai, Andrea Sharkey, Jessica Osterman, Robert Suss, Zad Chow, Robert Suss, Ingrid Wells, Nasira Spells, Erica Finfer, Rachael Biscoho, and Ana Camargo for assisting with data collection and coding.

Funding information

NIH Office of the Director, Grant/Award Number: DP5OD021373-01

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

The authors have indicated that they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The study sponsor had no involvement in study design, data collection, interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations:

- CFBAI

Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative

- KFC

Kentucky Fried Chicken

- NPI

Nutrient Profile Index

- NPM

Nutrient Profile Model

Footnotes

DATA ACCESSIBILITY

Data will be available upon request.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have indicated that they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cairns G, Angus K, Hastings G, Caraher M. Systematic reviews of the evidence on the nature, extent and effects of food marketing to children: a retrospective summary. Appetite. 2013;62:209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Food and Nutrition Board, Committee on Food Marketing and the Diets of Children and Youth. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity?. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Council of Better Business Bureaus. Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI). http://www.bbb.org/council/the-national-partner-program/national-advertising-review-services/childrens-food-and-beverage-advertising-initiative/about-the-initiative/. Accessed March 2016.

- 4.Rideout V. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Tweens and Teens. Common Sense Media; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ofcom Children and Parents: Media Use and Attitudes Report 2018. Ofcom; 2019. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/134907/Children-and-Parents-Media-Use-and-Attitudes-2018.pdf.

- 6.Yu M, Baxter J. Growing up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2015. Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2016. https://growingupinaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/lsac-asr-2015-book.pdf.

- 7.Steeves V. Young Canadians in a Wired World, Phase III: Trends and Recommendations. Media Smarts; 2014. https://mediasmarts.ca/sites/mediasmarts/files/publication-report/full/ycwwiii_trends_recommendations_fullreport.pdf.

- 8.Lenhart A, Page D. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015: smartphones facilitate shifts in communication landscape for teens. http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/04/PI_TeensandTech_Update2015_0409151.pdf. Published April 9, 2015. Accessed September 27, 2017.

- 9.Federal Trade Commission. A review of food marketing to children and adolescents: follow-up report. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/review-food-marketing-children-and-adolescents-follow-report/121221foodmarketingreport.pdf. Published December 2012. Accessed October 9, 2017.

- 10.Whalen R, Harrold J, Child S, Halford J, Boyland E. Children’s exposure to food advertising: the impact of statutory restrictions. Health Promot Int. 2019;34(2):227–235. October 2017. 10.1093/heapro/dax044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen D. STUDY: Global Social Media Ad Spend to Reach $36B in 2017. AdWeek. http://www.adweek.com/digital/emarketer-global-social-media-ad-spend/. Published April 20, 2015. Accessed October 9, 2017.

- 12.Ignatius A. Shaking Things up at Coca-Cola. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2011/10/shaking-things-up-at-coca-cola. Published October 2011.

- 13.Taking stock with teens: a collaborative consumer insights project. http://www.politico.com/f/?id=00000157-c525-d9f3-a3d7-f565d9d20000. Published October 14, 2016. Accessed September 5, 2017.

- 14.McNeal JU. Children as Consumers: A Review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 1979;7(3):346–359. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore ES, Wilkie WL, Lutz RJ. Passing the torch: intergenerational influences as a source of brand equity. J Mark. 2002;66(2):17–37. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapinski MK, Rimal RN. An explication of social norms. Commun Theory. 2005;15(2):127–147. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherman LE, Payton AA, Hernandez LM, Greenfield PM, Dapretto M. The power of the like in adolescence: effects of peer influence on neural and behavioral responses to social media. Psychol Sci. 2016;27 (7):1027–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherman LE, Greenfield PM, Hernandez LM, Dapretto M. Peer influence via instagram: effects on brain and behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Child Dev. 2018;89(1):37–47. June 2017. 10.1111/cdev.12838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:111–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett S. Marketing 101—social media vs traditional media [INFOGRAPHIC]. AdWeek. http://www.adweek.com/digital/social-vs-traditional-media-marketing/. Published July 13, 2012. Accessed October 18, 2017.

- 21.Common Sense Media. Common sense media—advertising to children and teens: current practices. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/file/csm-advertisingresearchbrief-20141pdf/download. Published 2014. Accessed October 9, 2017.

- 22.OMMA Awards. MediaPost https://www.mediapost.com/ommaawards/winners/?event=2013. Accessed April 25, 2018.

- 23.Montgomery K, Chester J. Digital Food Marketing to Children and Adolescents: Problematic Practices and Policy Interventions. National Policy & Legal Analysis Network to Prevent Childhood Obesity; 2011. https://www.foodpolitics.com/wp-content/uploads/DigitalMarketingReport_FINAL_web_20111017.pdf.

- 24.Freeman B, Kelly B, Baur L, et al. Digital junk: food and beverage marketing on Facebook. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):e56–e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunlop S, Freeman B, Jones SC. Marketing to youth in the digital age: the promotion of unhealthy products and health promoting behaviours on social media. Media and Communication. 2016;4(3):35–49. http://search.proquest.com/openview/88a3dcdfa231ad6bace8742ab48496f9/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2034126. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laestadius LI, Wahl MM. Mobilizing social media users to become advertisers: corporate hashtag campaigns as a public health concern. DIGITAL HEALTH. 2017;3:2055207617710802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman B, Kelly B, Vandevijvere S, Baur L. Young adults: beloved by food and drink marketers and forgotten by public health? Health Promot Int. 2016;31(4):954–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montgomery KC, Chester J. Interactive food and beverage marketing: targeting adolescents in the digital age. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3 Suppl):S18–S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson M, Jiang J. Teens, social media & technology 2018. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; Retrieved June 2018;3: 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Evaluating fast food nutrition and marketing to youth. New Haven, CT: Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. 2010. http://fastfoodmarketing.org/media/FastFoodFACTS_Report_Summary_2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Shehan C, et al. Snack FACTS 2015: Evaluating snack food nutrition and marketing to youth. Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD, Javadizadeh J, Weinberg M, et al. Evaluating sugary drink nutrition and marketing to youth. New Haven, CT: Yale Rudd Center For Food Policy and Obesity. 2011. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4c0c/fc3aaea547fed24315181d9a4b5318547b56.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lombard M, Snyder-Duch J, Bracken CC. Content analysis in mass communication: assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Hum Commun Res. 2002;28(4):587–604. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rayner M, Scarborough P, Boxer A. Nutrient profiles: development of final model. www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/nutprofr.pdf. Published December 2005. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- 35.Scarborough P, Boxer A, Rayner M. Testing nutrient profile models using data from a survey of nutrition professionals. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(4):337–345. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/testing-nutrient-profile-models-using-data-from-a-survey-of-nutrition-professionals/5BDF8ABE7F1A48A352FBEEE079F11A88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boelsen-Robinson T, Backholer K, Peeters A. Digital marketing of unhealthy foods to Australian children and adolescents. Health Promot Int. 2016;31(3):523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandevijvere S, Sagar K, Kelly B, Swinburn B. Unhealthy food marketing to New Zealand children and adolescents through the internet. N Z Med J. 2017;130(1450):32–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar G, Onufrak S, Zytnick D, Kingsley B, Park S. Self-reported advertising exposure to sugar-sweetened beverages among US youth. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(7):1173–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scully M, Wakefield M, Niven P, et al. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents’ food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite. 2012;58(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. Sugary Drinks F.A.C.T.S (Food Advertising to Children and Teens Score). http://www.sugarydrinkfacts.org/resources/sugarydrinkfacts_report.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- 41.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Munsell CR, et al. Fast food FACTS 2013: measuring progress in nutrition and marketing to children and teens. New Haven, CT: Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. 2013. http://www.fastfoodmarketing.org/media/fastfoodfacts_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baldwin HJ, Freeman B, Kelly B. Like and share: associations between social media engagement and dietary choices in children. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(17):3210–3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henry AE, Story M. Food and beverage brands that market to children and adolescents on the internet: a content analysis of branded web sites. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(5):353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weber K, Story M, Harnack L. Internet food marketing strategies aimed at children and adolescents: a content analysis of food and beverage brand web sites. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(9):14631466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montgomery KC, Chester J, Grier SA, Dorfman L. The new threat of digital marketing. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59(3):659–675, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.John Koetsier S. Are #hashtags geeky? 71% of social media users say no. VentureBeat. https://venturebeat.com/2013/03/27/are-hashtags-geeky-71-of-social-media-users-say-no/. Published March 27, 2013. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- 47.Czaplicki L, Kostygina G, Kim Y, et al. Characterising JUUL-related posts on Instagram. Tob Control. July 2019. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054824 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.TV Dinners: What’s being served up the advertisers? Sustain: The alliance for better food and farming. https://www.sustainweb.org/secure/cfb_tvdinners.pdf. Published 2001. Accessed October 18, 2017.

- 49.Stringhini G, Wang G, Egele M, et al. Follow the green: growth and dynamics in Twitter follower markets. In: Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Internet Measurement Conference. IMC ‘13. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2013:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Potvin Kent M, Pauzé E, Roy E-A, de Billy N, Czoli C. Children and adolescents’ exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14(6):e12508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.