Abstract

Background

Intra-continentally, vaginal microbiome signatures are reported to be significantly different between Black and Caucasian women, with women of African ancestry having the less well defined heterogenous bacterial community state type (CST) deficient of Lactobacillus species (CST IV). The objective of this study was to characterize the vaginal microbiomes across a more diverse intercontinental group of women (N = 151) of different ethnicities (African American, African Kenyan, Afro-Caribbean, Asian Indonesian and Caucasian German) using 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis to determine their structures and offer a comprehensive description of the non-Lactobacillus dominant CSTs and subtypes.

Results

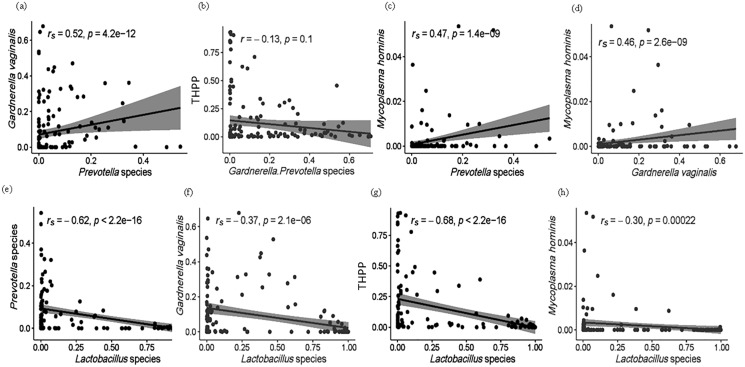

In this study, the bacterial composition of the vaginal microbiomes differed significantly among the ethnic groups. Lactobacillus spp. (L. crispatus and L. iners) dominated the vaginal microbiomes in African American women (91.8%) compared to European (German, 42.4%), Asian (Indonesian, 45.0%), African (Kenyan, 34.4%) and Afro-Caribbean (26.1%) women. Expanding on CST classification, three subtypes of CST IV (CST IV-A, IV-B and IV-C) (N = 56, 37.1%) and four additional CSTs were described: CST VI Gardnerella vaginalis—dominant (N = 6, 21.8%); CST VII (Prevotella—dominant, N = 1, 0.66%); CST VIII (N = 9, 5.96%), resembling aerobic vaginitis, was differentiated by a high proportion of taxa such as Enterococcus, Streptococcus and Staphylococcus (relative abundance [RA] > 50%) and CST IX (N = 7, 4.64%) dominated by genera other than Lactobacillus, Gardnerella or Prevotella (e.g., Bifidobacterium breve and Anaerococcus vaginalis). Within the vaginal microbiomes, 32 “taxa with high pathogenic potential” (THPP) were identified. Collectively, THPP (mean RA ~5.24%) negatively correlated (rs = −0.68, p < 2.2e−16) with Lactobacillus species but not significantly with Gardnerella/Prevotella spp. combined (r = −0.13, p = 0.1). However, at the individual level, Mycoplasma hominis exhibited moderate positive correlations with Gardnerella (r = 0.46, p = 2.6e−09) and Prevotella spp. (r = 0.47, p = 1.4e−09).

Conclusions

These findings while supporting the idea that vaginal microbiomes vary with ethnicity, also suggest that CSTs are more wide-ranging and not exclusive to any particular ethnic group. This study offers additional insight into the structure of the vaginal microbiome and contributes to the description and subcategorization of non-Lactobacillus-dominated CSTs.

Keywords: Vaginal microbiome, Community state types, CST subtypes, Ethnicity, Ancestries, Lactobacillus, Pathobionts, Mycoplasma, Prevotella, Gardnerella

Introduction

The vaginal microbiome is thought to be influenced by host genetics, environmental and cultural factors (Gupta, Paul & Dutta, 2017). Whereas the microbial composition of the vaginal microbiome is individual-specific and similar across non-Caucasian groups including Asian, Black and Hispanic women (Feehily et al., 2020; Si et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2010), the structure of the vaginal microbial communities of women of African American descent has been reported to be distinct from that of Caucasian women (Borgdorff et al., 2017; Gupta, Paul & Dutta, 2017; Ravel et al., 2011) However, a recent study by Beamer et al. (2017) found no significant difference in the vaginal microbiomes of these two ethnic groups that were free of bacterial vaginosis (BV), Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Trichomonas vaginalis infections. The microbial composition of the vaginal microbiome has been clustered into five structures, referred to as community state types (CSTs) I, II, III, IV and V, based on the relative abundance (RA) of four microaerophilic Lactobacillus species (L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners and L. jensenii) and a heterogenous group of microbes. CST I is dominated by L. crispatus, and CST II, III and V by L. gasseri, L. iners and L. jensenii, respectively. CST IV, considered a dysbiotic state, is Lactobacillus deficient and consists of a polymicrobial group of strict obligate and facultative anaerobes (such as Prevotella, Gardnerella, Atopobium, Aerococcus, Anaerococcus, Dialister, Finegoldia, Peptoniphilus, Parvimonas, Megasphaera, Sneathia, Eggerthella, Veillonella, Gemella, Peptostreptococcus, Bifidobacterium, and Corynebacterium along with rarer taxa) (Fettweis et al., 2014; Ravel et al., 2011). Recognised among this polymicrobial group are bacteria such as Campylobacter, Enterococcus, Escherichia, Haemophilus, Mycoplasma, Shigella, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus which have previously been referred to as “pathobionts”, symbionts implicated in host pathology due to chronic uncontrolled inflammation (Chow, Tang & Mazmanian, 2011; van de Wijgert et al., 2020). However, since there is no evidence of causality and all human symbionts are potentially pathogenic (Jochum & Stecher, 2020), within the context of the vaginal microbiome we shall refer to these organisms as “taxa with high pathogenic potential” (THPP). Several THPP and other anaerobes reside in Prevotella–enhanced G. vaginalis biofilms (dynamic, highly organized adherent bacterial communities self-encased in an extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) that forms a matrix) (Patterson et al., 2007). The vaginal biofilm allows G. vaginalis to thrive in the presence of high concentrations of lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide, bactericidins and antibiotics produced by lactobacilli and other competing micro-organisms (Machado & Cerca, 2015; Castro, Machado & Cerca, 2019). Like Prevotella spp. and G. vaginalis., some Lactobacillus species (such as L. jensenii) have been shown to form vaginal biofilms in vivo (Ventolini, 2015). Disruption of microbiota biofilms can lead to the release of THPP and other associated bacteria into the local milieu (Buret et al., 2019).

With widespread high-throughput metagenomic sequencing and characterization of vaginal microbiomes across global hemispheres, CSTs dominated by genera other than Lactobacillus have been reported (e.g., Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella, Bifidobacterium and THPP, such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus) (Anukam et al., 2019; Borgdorff et al., 2017). In addition, the findings of recent studies involving healthy black African women (Nigerian, Kenyan, Rwandan and South African) who were found to have Lactobacillus-dominant vaginal microbiomes (Anukam et al., 2019; Jespers et al., 2017), are at variance with the results of scientific research emanating from the U. S. A and the Netherlands where the vaginal microbiomes of women of African ancestry (African American, African Surinamese and African Ghanaian) were predominantly of CST IV (Borgdorff et al., 2017; Fettweis et al., 2014; Ravel et al., 2011). In this study, we sought to examine microbial vaginal composition and structure across varied ethnicities by characterizing and analysing the vaginal microbiome of Afro-Caribbean, African American, African Kenyan, Asian Indonesian and Caucasian German women. Additionally, the theoretical relationships between variation in relative abundance of THPP (singly and combined), facultative (Lactobacillus) and obligate anaerobes (Gardnerella and Prevotella) were also assessed.

Materials and Methods

Genomic DNA extraction and 16S rDNA V4 sequencing by MiSeq illumina

Cervicovaginal sampling from 18 Afro-Caribbean female participants, gDNA extraction using InstaGene™ Matrix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and amplification of the V4 region of 16S rRNA gene [using custom adaptor ligated primers 515F 5′- GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′ and 806R 5′- GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′ (Caporaso et al., 2011; Moustafa et al., 2018)] were conducted as previously described (Roachford et al., 2021). Illumina sequencing was performed at J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI), La Jolla, California, USA. This research was approved (IRB# 170710-B) by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) and Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados.

Vaginal microbiome 16S rRNA V4 datasets

Overall, this study involved the analysis of vaginal microbiome 16S rRNA V4 datasets from a total of 151 women (regardless of health status) of five different ethnicities. Of the 151 DNA datasets, 133 were from published data and 18 from the experimental DNA, representing women of five different ethnicities. Datasets were sub-sampled and downloaded from the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA): African American (AA) (PRJNA422447, N = 28), African Kenyan (AK) (PRJNA516684, N = 31), Asian Indonesian (AI) (PRJEB34323, N = 36) and Caucasian German (CG) (PRJEB17077, N = 38). With respect to the CG dataset, the V4 region was trimmed from the V3–V4 hypervariable sequence using Trimmomatic v0.39 (Bolger, Lohse & Usadel, 2014). DNA datasets from the 151 women were grouped and concatenated based on ethnicity, for downstream analyses. The cervicovaginal microbiome of the Afro-Caribbean (AC) women (N = 18) were characterized and analyzed along with those of AA, AK, AI and CG women.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis of 16S rRNA V4 data

Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME 2, version 2019.10) was used to analyze the 16S rRNA V4 hypervariable region of the datasets following importation into a QIIME 2 artifact. DADA2 plugin was utilized to generate an amplicon sequence variant (ASV) feature table after quality control (sequence correction, de-replication, low-quality filtering and chimeric sequence removal). Taxonomic assignment to ASVs at 97% sequence similarity was achieved using a Naive-Bayes classifier trained on the V4 region of SILVA_138_SSURef_NR99 database. The feature table was rarefied to a sampling depth of 80,000 with q2-diversity core-metrics-phylogenetic plugin. Alpha and Beta diversities were determined using Shannon’s diversity index and unweighted UniFrac distance metric, respectively. Taxonomic barplots, boxplots and three-dimensional principal coordinates analysis (3D-PCoA) plots were generated in QIIME 2 (Caporaso et al., 2010) using taxa barplot, diversity alpha-group-significance and emperor plot plugins, respectively. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) and Kruskal–Wallis tests also implemented in QIIME 2 were used to assess whether there were significant microbial composition differences among ethnic groups. To identify the bacterial taxa that accounted for meaningful variance in the microbial composition among the various ethnicities, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) in a python 2.7 conda environment was utilized. In the analysis, a non-parametric factorial Kruskal–Wallis sum-rank test within LEfSe identified the differentially abundant taxa and LDA quantified their effect on microbial composition variance (Segata et al., 2011). A LEfSe barplot was produced where horizontal bars represented the effect size for the differentiating feature (bacterial taxa). An LDA effect size >2 and a p-value < 0.05 were used as cutoffs. Community state types (CSTs) for vaginal samples were generated by hierarchical clustering using the complete linkage method and visualized as a heatmap using the hclust function and ComplexHeatmap package in R version 4.0.3 (R Core Team, 2020). The relationships between strict anaerobes (Prevotella and Gardnerella), Lactobacillus species, THPP and specifically M. hominis were explored using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (when linear covariation) and Spearman’s rank correlation (where data not normally distributed) tests. Distribution of the variables was checked and visualized using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test and ggqqplot function in ggpubr R package. Correlation coefficients and plots for associations between bacterial taxa were generated with the cor.test and ggscatter functions (ggpubr R package), respectively.

Results

Amplicon sequence characteristics

Samples from the five ethnic groups yielded a total of 8,527,099 amplicon sequences. Filtration of low quality reads and chimeras generated 4,368,987 sequences: Afro-Caribbean (355,080), African American (91,809), African Kenyan (994,995), Asian Indonesian (1,080,047) and Caucasian German (1,847,056) (Table S1). The Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) feature table produced 2,521 features with sequence lengths of 250 bp across all five ethnic groups. A total of 663 taxa were identified after sequences were matched against SILVA database using feature-classifier, classify-sklearn, in QIIME 2 (Table S2).

Cervicovaginal microbiome composition across ethnic groups

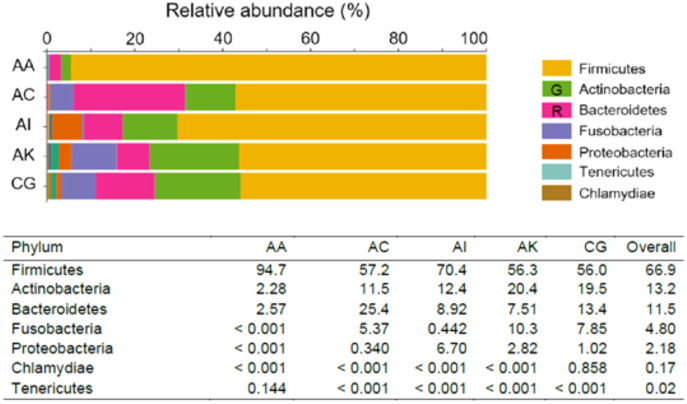

The most abundant phyla (RA > 0.10%) recognized across the five ethnic groups were Firmicutes (lead by AA, with an RA of 94.7%), followed by Actinobacteria (lead by AK, RA = 20.4%) and Bacteroidetes (predominant in AC, RA = 25.4%). Fusobacteria was of greater abundance in AK (10.3%), whereas Proteobacteria predominated in AI (6.70%). Two other phyla, Tenericutes and Chlamydiae, with RA between 0.10–1.00% were only found in AA (0.144%) and CG (0.858%), respectively (Fig. 1). At the genus level, Lactobacillus was the most dominant amongst the five ethnic groups, RA ranged from 26.1% to 91.8% in AC and AA, respectively. Overall, the RA of Lactobacillus species was 47.9%. The Lactobacillus species identified were L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, L. equi, L. mucosae, L. murinus and L. salivarius. The next most abundant genus was Prevotella (which consisted of P. denticola, P. amnii, P. bivia, P. buccalis, P. disiens and P. ihumnii ) accounted for 8.92% of all taxa among the five ethnic groups. It was most abundant among AC women (21.0%) and least among AA women (2.11%). Genera/species identified among the ethnic groups, with RA > 1.00% were Gardnerella which consisted G. vaginalis (8.40%), Sneathia (S. amnii, S. sanguinegens; 4.57%), “Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae” (formerly Shuttleworthia and BVBA1 (Holm et al., 2020), 3.41%), Anaerococcus (A. lactolyticus, A. prevotii, A. provenciensis, A. vaginalis; 2.57%), Megasphaera (M. indica; 2.30%), Atopobium (A. deltae, A. minutum; 12%), Corynebacterium (C. aurimucosum, C. genitalium, C. jeikeium, C. kroppenstedtii, C. durum, C. Pyruviciproducens; 1.16%), Escherichia–Shigella (1.14%) and Enterococcus (1.14%). Other significant taxa identified within the vaginal microbiomes but with relative abundance <0.10% were Staphylococcus, Veillonella, Fastidiosipila, Bifidobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Peptoniphilus, Dialister, Porphyromonas, Gemella, Finegoldia, Mobiluncus, Parvimonas, Ureaplasma parvum, Mycoplasma hominis and Moryella indoligenes. Chlamydia trachomatis which was notable among Caucasian German women (0.857%), was absent or less than 0.001% among women of other ethnicities (Tables 1 and S3).

Figure 1. Taxonomic pattern and percentage relative abundance of the top seven phyla within the vaginal microbiomes of the five ethnic groups (AA, African American; AC, Afro-Caribbean; AI, Asian Indonesian; AK, African Kenyan and CG, Caucasian German). G = Green; R = Red.

Table 1. Relative abundance of top 30 taxa at genus level across five ethnic groups.

| Relative abundance (%) in ethnic groups | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxa (genus level) | AA | AC | AI | AK | CG | Overall (%) | Species identified |

| Lactobacillus | 91.8 | 26.1 | 45.0 | 34.4 | 42.4 | 47.9 | L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, L. equi, L. mucosae, L. murinus, L. salivarius |

| Gardnerella | 0.884 | 9.91 | 6.24 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 8.40 | G. vaginalis |

| Prevotella | 2.11 | 21.0 | 5.05 | 4.52 | 12.0 | 8.92 | P. denticola, P. amnii, P. bivia, P. buccalis, P. disiens, P. ihumnii |

| Sneathia | 0.00 | 5.26 | 0.001 | 9.77 | 7.81 | 4.57 | S. amnii, S. sanguinegens |

| Megasphaera | 0.001 | 3.51 | 0.307 | 2.45 | 5.25 | 2.30 | M. indica |

| Atopobium | 1.36 | 0.909 | 0.667 | 3.34 | 4.34 | 2.12 | A. deltae, A. minutum |

| Anaerococcus | 0.094 | 6.95 | 2.84 | 2.79 | 0.206 | 2.57 | A. lactolyticus, A. prevotii, A. provenciensis, A. vaginalis |

| Shuttleworthia (BVBA1) | 0.00 | 15.3 | 0.00 | 1.06 | 0.711 | 3.41 | – |

| Corynebacterium | 0.00 | 0.185 | 2.14 | 3.50 | 0.00 | 1.16 | C. aurimucosum, C. genitalium, C. jeikeium, C. kroppenstedtii, C. durum, C. Pyruviciproducens |

| Veillonella | 0.00 | 0.511 | 0.069 | 0.902 | 1.98 | 0.692 | V. montpellierensis, V. seminalis |

| Fastidiosipila | 0.00 | 0.620 | 0.705 | 1.86 | 0.758 | 0.788 | Unidenitfied |

| Bifidobacterium | 0.00 | 0.001 | 0.519 | 0.151 | 1.73 | 0.479 | B. breve, B. avesanii, B. dentium, B. longum |

| Peptoniphilus | 0.148 | 0.285 | 2.29 | 0.704 | 0.001 | 0.686 | P. lacrimalis, L. obesi, L. phoceensis |

| Dialister | 0.394 | 1.58 | 0.207 | 1.10 | 0.775 | 0.811 | D. pneumosintes |

| Porphyromonas | 0.272 | 2.08 | 0.450 | 0.856 | 0.480 | 0.827 | P. asaccharolytica |

| Gemella | 0.00 | 0.602 | 0.247 | 0.173 | 1.17 | 0.439 | G. asaccharolytica, G. haemolysans |

| Prevotella 6 | 0.001 | 1.83 | 1.06 | 0.360 | 0.342 | 0.718 | – |

| Finegoldia | 0.315 | 0.001 | 1.94 | 0.478 | 0.001 | 0.547 | F. magna |

| Mobiluncus | 0.000 | 0.001 | 1.53 | 0.835 | 0.001 | 0.474 | M. curtisii |

| Parvimonas | 0.000 | 0.088 | 0.550 | 0.471 | 0.560 | 0.334 | Unidenitfied |

| Moryella | 0.00 | 0.043 | 0.572 | 1.17 | 0.001 | 0.357 | M. indoligenes |

| Chlamydia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.857 | 0.171 | C. trachomatis |

| Streptococcus | 0.001 | 0.001 | 2.02 | 4.98 | 0.597 | 1.52 | S. agalactiae, S. anginosus, S. salivarius |

| Escherichia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.59 | 1.08 | 0.000 | 1.14 | Unidenitfied |

| Enterococcus | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.02 | 0.512 | 0.573 | 1.02 | Unidenitfied |

| Peptostreptococcus | 1.64 | 0.001 | 2.72 | 0.184 | 0.293 | 0.967 | Unidenitfied |

| Staphylococcus | 0.001 | 0.001 | 2.68 | 2.05 | 0.038 | 0.954 | Unidenitfied |

| Ureaplasma | 0.144 | 0.001 | 0.084 | 1.43 | 0.251 | 0.383 | U. parvum |

| Mycoplasma | 0.00 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.310 | 0.805 | 0.223 | M. hominis |

| Unassigned bacteria | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.730 | 0.797 | 0.00 | 0.305 | – |

Note:

AA, African American; AC, Afro-Caribbean; AI, Asian Indonesian; AK, African Kenyan; CG, Caucasian German. Shuttleworthia (BVAB1) has been renamed as Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae (Holm et al., 2020).

Alpha and beta diversity

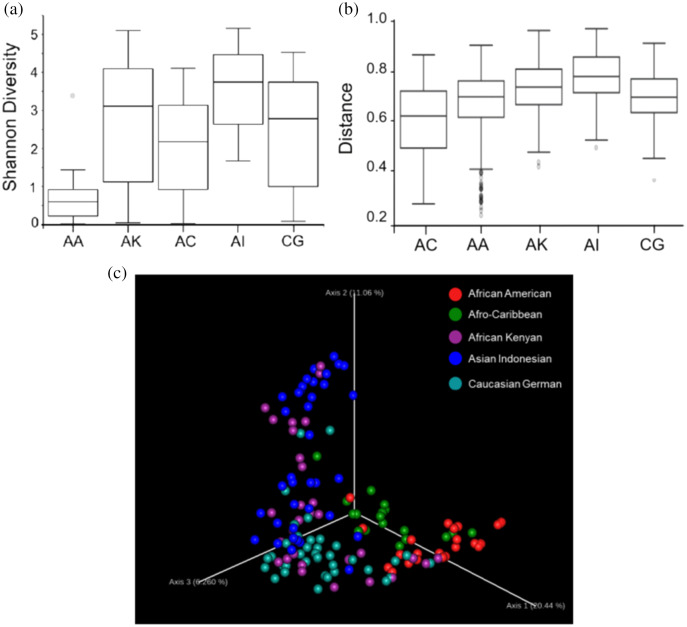

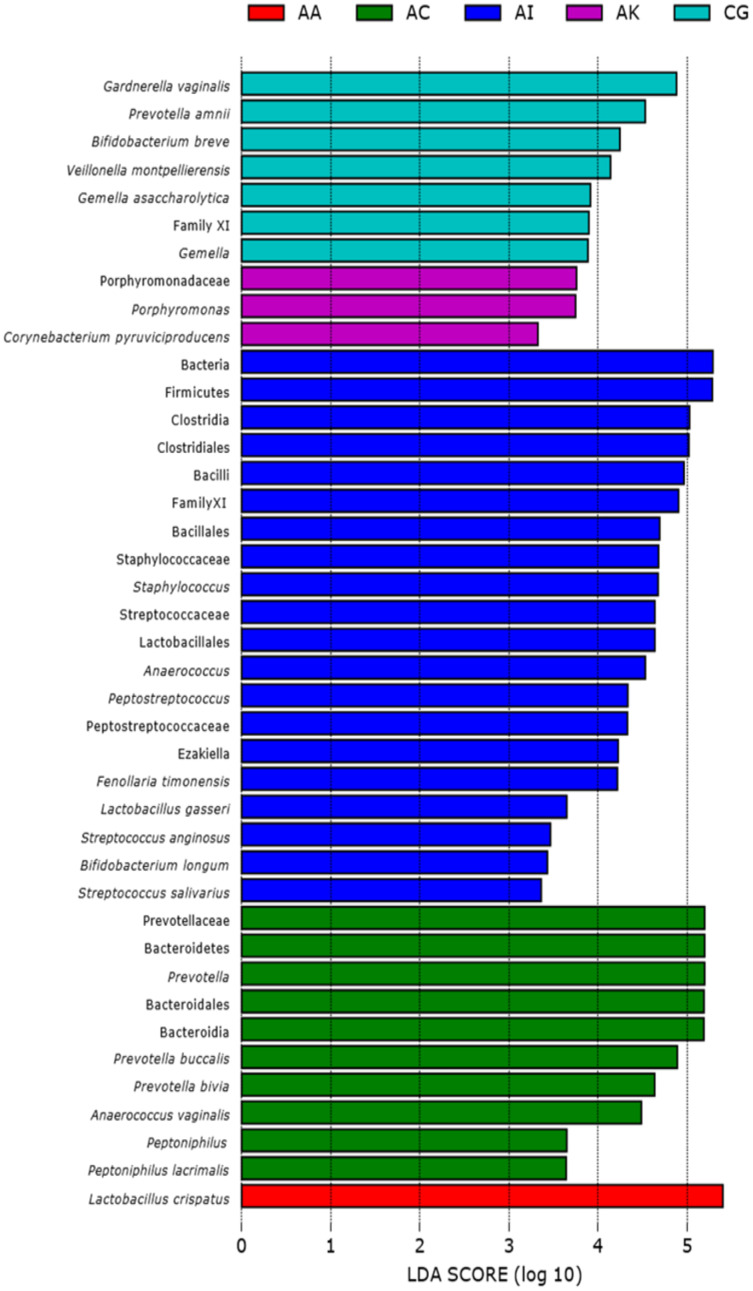

Based on the Shannon alpha diversity index which assesses bacterial community diversity (amplicon sequence variants) and evenness, there was a statistically significant difference (Kruskal–Wallis (pairwise), p-value > 3.59e−11) in species richness within samples across the five ethnic groups. Species richness within the samples from AC women was significantly different to that of AA (p-value > 6.50e−04) and AI (p-value = 0.0003) women but not significantly different to that of samples from AK and CG women (p-value = 0.120 and 0.262, respectively) (Fig. 2A and Table S1). Statistically, species diversity (Beta diversity) as determined by Unweighted UniFrac matrix, was significantly different (PERMANOVA, p-value = 0.001) among the five ethnic groups as shown in boxplots (Fig. 2B and Table S1), where a diversity distance of 0 represents identical bacterial composition of the vaginal microbiome and a distance of 1 indicates total dissimilarity. The 151 vaginal samples clustered into five groups as visualized by 3D-PCoA (Unweighted–UniFrac diversity matrix), representing the (Beta) diversity of the vaginal microbiomes of the five ethnic groups (Fig. 2C). To explain the beta diversity among the ethnic groups, linear discriminant analysis (LEfSe with abs LDA score > 2.0) was performed. The LEfSe plot (Fig. 3) shows the discriminant taxa observed within the vaginal microbiomes of the five ethnic groups. L. crispatus was differentially of higher abundance in African Americans. Additionally, the variance in species diversity among AC, AI, AK and CG women could be explained by the differential abundance of Prevotella spp., THPP, Corynebacterium, Porphyromonas spp., Gemella spp. and G. vaginalis, respectively.

Figure 2. Plots showing species richness and diversity among the five ethnic groups (AA, African American; AC, Afro-Caribbean; AI, Asian Indonesian; AK, African Kenyan and CG, Caucasian German).

(A) Boxplot shows distribution of species richness and evenness within the vaginal microbiomes of the ethnic groups using Shannon diversity matrix. (B) Boxplot showing the distribution of unweighted unifrac distances among the five ethnicities. (C) Three-dimensional principal coordinates analysis (3D-PCoA) visualization of pairwise Bray-Curtis distance matrices indicating vaginal bacterial species diversity among the five ethnicities.

Figure 3. Linear discriminant analysis (LEfSe with abs LDA score >2.0) plot showing differentiating bacterial taxa of the vaginal microbiomes of the five ethnic groups (AA, African American; AC, Afro-Caribbean; AI, Asian Indonesian; AK, African Kenyan and CG, Caucasian German).

Each horizontal bar represents effect size for the differentiating feature (bacterial taxa).

Hierarchical clustering analysis of the vaginal samples for all ethnic groups

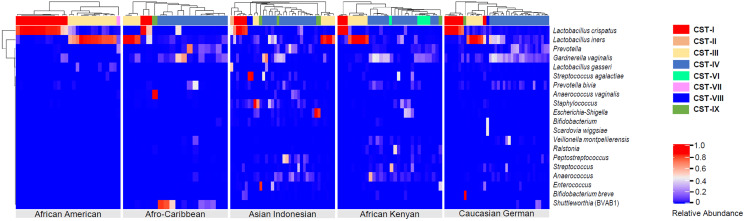

Hierarchical clustering analysis of the vaginal samples, using the complete linkage method, was performed to find similar clusters within the samples. Eight clusters, representing CSTs, were found and visualized as a heatmap (Fig. 4). An organism was considered to be dominant within each CST where its percentage RA was equal or greater than 50%. Overall, CSTs (Table 2) were predominated by Lactobacilli species: L. iners—dominant clusters (CST III, N = 38, 25.2%) and L. crispatus—dominant clusters (CST I, N = 33, 21.8%). There was only one L. gasseri dominant cluster (CST II) and no L. jensenii—dominant clusters. CST IV, a polymicrobial community state, was the most common CST (N = 56, 37.1%) among all women. Three subtypes of CST IV (CST IV-A, IV-B and IV-C) were identified: CST IV-A consisted of heterogeneous bacteria with G. vaginalis in high proportions (but RA < 50%), CST IV-B consisted of heterogeneous bacteria and Prevotella (RA ≤ 45%) and CST IV-C which comprised of heterogeneous bacteria along with any predominant microbe other than Gardnerella or Prevotella (RA < 50%). Predominant bacteria identified within CST IV-C were Bifidobacterium, Corynebacterium, Clostridiales bacterium, L. iners, Peptostreptococcus, Streptococcus and Ureaplasma parvum. Other clusters identified were: G. vaginalis—dominant clusters [(CST VI) (N = 6, 21.8% of women), present in AC, AI and AK women only], a Prevotella—dominant cluster [(CST VII) (N = 1, 0.66% of women) found in an AC woman], THPP—dominant clusters [(CST VIII) (N = 9, 5.96%), present only in AI and AK women] and CST IX (N = 7, 4.64%) which represented a group of clusters dominated by bacteria other than Lactobacilli, G. vaginalis, Prevotella and THPP. Clusters within this CST (IX) mainly occurred as singletons (i.e., occurring in only one sample) in all ethnic groups except African Americans. Six bacteria dominated in this cluster: Bifidobacterium breve (RA = 98%), Finegoldia (RA = 71%), Anaerococcus vaginalis (RA = 93%), Anaerococcus (RA = 62% ), Ralstonia (RA = 51%) and Lachnocurva vaginae which was dominant in two samples (RA ≥ 80%).

Figure 4. Heatmap displaying the relative abundance of the top 20 bacterial taxa within the vaginal microbiomes of five ethnic groups (African American, Afro-Caribbean, Asian Indonesian, African Kenyan and Caucasian German).

Hierarchical clustering of the 151 vaginal samples resulted in eight clusters designated as community state types: CST I–IV and VI–IX.

Table 2. Cervicovaginal microbiome structures and community state types across five ethnic groups.

| Cervicovaginal microbiome structure | Cluster description, relative abundances of taxa (%) | Assigned CST | AA | AC | AI | AK | CG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. crispatus predominant, RA > 50% | L. crispatus—dominant > 98.9% | I | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| L. crispatus—dominant > 97%, Prevotella bivia > 0.5% | I | 2 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 97%, G. vaginalis > 2.0% | I | 1 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 92%, L. iners > 0.5% | I | 5 | 2 | 1 | |||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 66%, L. iners > 30% | I | 1 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant ≥ 55%, L. iners 40%, heterogenous bacteria | I | 1 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 90%, L. iners > 4%, Corynebacterium 1 > 1.0% | I | 1 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 57%, Atopobium >20%, G. vaginalis >14% | I | 2 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 86%, G. vaginalis > 5.0%, Streptococcus agalactiae > 2.5%, Staphylococcus > 1.6% | I | 1 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 86%, L. iners > 3.0%, heterogenous bacteria | I | 1 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 80%, Bifidobacterium breve > 6.3%, Enterococcus > 5.2% | I | 1 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant > 80%, Bifidobacterium breve > 6.3%, Streptococcus > 3.1% | I | 1 | |||||

| L. crispatus—dominant ≥ 80%, G. vaginalis > 8.0%, heterogenous bacteria | I | 1 | |||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST-I | 14 (50%) | 2 (11%) | 7 (19%) | 3 (9.7%) | 7 (18%) | ||

| L. gasseri predominant, RA > 50% | |||||||

| L. gasseri—dominant 52%, L. iners 43% | II | 1 | |||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- II | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.8%) | 0 | 0 | ||

|

L. iners

predominant, RA > 50% |

|||||||

| L. iners—dominant ≥ 98% | III | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |

| L. iners—dominant > 90%, L. crispatus > 1.5% | III | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| L. iners—dominant 60–75%, L. crispatus > 24% | III | 2 | |||||

| L. iners—dominant > 80%, L. gasseri 2.8–17% | III | 4 | |||||

| L. iners—dominant ≥ 80%, heterogenous bacteria | III | 3 | 1 | ||||

| L. iners—dominant 72%, unassigned bacteria 25%, heterogenous bacteria | III | 1 | |||||

| L. iners—dominant > 80%, G. vaginalis 4.0%— ≥ 10% | III | 1 | 4 | ||||

| L. iners—dominant >55G. vaginalis > 25% Atopobium | III | 2 | 1 | ||||

| L. iners > 50% THPP = Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus | III | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- III | 13 (46%) | 3 (17%) | 5 (14%) | 8 (26%) | 9 (24%) | ||

| Polymicrobial microbiome with G. vaginalis most dominant but with a RA < 50% | |||||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, G. vaginalis 44%, Atopobium 32%, Veillonella montpellierensis 11% | IV-A | 1 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, G. vaginalis 28–32% and Prevotella bivia 11–15% | IV-A | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, G. vaginalis 34% Prevotella amnii 6.4% | IV-A | 1 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, G. vaginalis 36% Prevotella amnii 25–34%, Atopobium 17–23% | IV-A | 2 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, G. vaginalis 25–45% L. iners 37–44% | IV-A | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Heterogenous bacteria, G. vaginalis > Prevotella, Atopobium, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Anaerococcus | IV-A | 4 | 2 | ||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, G. vaginalis > Prevotella, Shuttleworthia, Megasphaera, Sneathia, L. iners | IV-A | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- IV-A | 0 | 0 | 4 (11%) | 10 (32%) | 10 (26%) | ||

| Polymicrobial microbiome with Prevotella species most dominant but with a RA < 50% | |||||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Prevotella 18%, low abundance Lactobacilli | IV-B | 3 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Prevotella > 36%, No Gardnerella | IV-B | 2 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Prevotella 16–46% | IV-B | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Prevotella > G. vaginalis, Shuttleworthia, Megasphaera, Sneathia amnii, L. iners | IV-B | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Prevotella > G. vaginalis, Gemella, Megasphaera, Sneathia amnii, L. iners, M. hominis | IV-B | 2 | 4 | ||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- IV-B | 0 | 7 (39%) | 5 (14%) | 0 | 10 (26%) | ||

| Polymicrobial microbiome with genera other than Gardnerella or Prevotella most dominant but with a RA < 50% | |||||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, L. iners 25–45% | 3 | ||||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Corynebacterium 1 27% | IV-C | 1 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Bifidobacterium 47%, Scardovia wiggsiae 49% | IV-C | 1 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Streptococcus agalactiae -dominant 46%, L. iners 13%, Sneathia spp. 10% | IV-C | 2 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Ureaplasma parvum 36%, Escherichia 33%, Staphylococcus 16% | IV-C | 1 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Clostridiales bacterium 34%, Shuttleworthia 16%, Veillonella 6.6% | IV-C | 1 | |||||

| Heterogenous bacteria, Peptostreptococcus 28%, Prevotella 25%, L. iners 13% | IV-C | 1 | |||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- IV-C | 1 (4.0%) | 0 | 6 (17%) | 2 (6.4%) | 1 (2.6%) | ||

| L. jensenii predominant, RA > 50% | |||||||

| L. jensenii—dominant > 50% | V | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Number/percentage of samples CST- V | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| G. vaginalis predominant, RA > 50% | |||||||

| G. vaginalis—dominant > 53%, L. iners 47% | VI | 1 | 1 | ||||

| G. vaginalis—dominant >60%, Sneathia spp., Shuttleworthia, Megasphaera, Atopobium, Aerococcus | VI | 1 | 1 | ||||

| G. vaginalis—dominant 54%, Streptococcus agalactiae 45% | VI | 1 | |||||

| G. vaginalis—dominant 68%, L. gasseri 22% | VI | 1 | |||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- VI | 0 | 2 (11%) | 2 (5.6%) | 2 (6.4%) | 0 | ||

| Prevotella species dominant, RA > 50% | |||||||

| Prevotella sp.—dominant > 70%, heterogenous bacteria | VII | 1 | |||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- VII | 0 | 1 (5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| THPP predominant, RA > 50% | |||||||

| Streptococcus—dominant 60%, Sneathia sanguinegens 23%, G. vaginalis 9.0%, heterogenous bacteria | VIII | 1 | |||||

| Streptococcus agalactiae-dominant > 85%, heterogenous bacteria | VIII | 2 | |||||

| Peptostreptococcus 54%, heterogenous bacteria | VIII | 1 | |||||

| Enterococcus—dominant >80%, Bacilli 15% | VIII | 1 | |||||

| Staphylococcus—dominant 65–86%, low abundance L. iners, Escherichia | VIII | 2 | |||||

| Escherichia-Shigella—dominant 88%, low abundance L. iners 5%, Anaerococcus | VIII | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- VIII | 0 | 0 | 5 (14%) | 4 (13%) | 0 | ||

| Genera other than Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, Prevotella and THPP that are predominant, RA > 50% | Finegoldia—dominant 71%, heterogenous bacteria | IX | 1 | ||||

| Anaerococcus vaginalis -dominant 93%, Howardella 5% | IX | 1 | |||||

| Anaerococcus—dominant 62%, G. vaginalis 26%, Veillonella montpellierensis 4.7%, Prevotella bivia 2.0% | IX | 1 | |||||

| Shuttleworthia—dominant ≥80%, G. vaginalis 2–6.2%, heterogenous bacteria | IX | 2 | |||||

| Ralstonia—dominant > 51%, Corynebacterium 1 9.0%, some THPP | IX | 1 | |||||

| Bifidobacterium breve—dominant > 98% | IX | 1 | |||||

| Number/percentage of samples CST- IX | 0 | 3 (17%) | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (2.6%) | ||

| Number of samples in ethnic group (Total No. of samples 151) | 28 | 18 | 36 | 31 | 38 |

Note:

AA, African American; AC, Afro-Caribbean; AI, Asian Indonesian; AK, African Kenyan; CG, Caucasian German; CST = Community State Type. Heterogenous bacteria = low abundance (<7.0%) of various bacteria such as Sneathia amnii, Sneathia sanguinegens, Megasphaera, Atopobium, Clostridiales bacterium, Dialister, Parvimonas, M. hominis, U. parvum, Finegoldia, Peptoniphilus, Mobiluncus, Corynebacterium, Howardella, Porphyromonas, Acinetobacter, Fusobacterium among other rare taxa. THPP = Campylobacter, Enterococcus, Haemophilus, Escherichia, Mycoplasma, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Ureaplasma; RA = Relative abundance; Shuttleworthia = BVAB1 = Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae (Holm et al., 2020). Numbers and percentages shown in bold represent the total number and percentage of an identified CST in a given ethnic group.

THPP within the vaginal microbiome

Within all 151 samples, 32 THPP taxa at the genus and species taxonomic level were identified (Table S3). Only seven of the 32 THPP taxa identified were among the top 30 bacterial taxa: Streptococcus (1.52%), Escherichia-Shigella (1.14%), Enterococcus (1.02%), Staphylococcus (0.954%), Peptostreptococcus (0.967%), U. parvum (0.383%) and M. hominis (0.223%) (Table 1). Species assigned the genus Streptococcus were S. agalactiae, S. anginosus and S. salivarius. Two intracellular species, Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae which are normally sexually transmitted were identified among the women. C. trachomatis was identified in all ethnic groups but with highest RA in CG women. N. gonorrhoeae, on the other hand, was only identified in vaginal samples from women of AK and CG ethnicity. Enterococcus, Escherichia–Shigella, Peptostreptococcus and Staphylococcus were dominant in the vaginal microbiomes of AI (14%) and AK (13%) women (Table 2). The relationship of THPP (relative abundance levels) with facultative and obligate anaerobes was examined, as well as the association between obligate and facultative anaerobes (Figs. 5 and S1). The relative abundance of THPP showed a strong negative correlation with Lactobacillus species (r = −0.68, p < 2.2e−16). Generally, there was no significant relationship (r = −0.13, p = 0.1) between THPP and the most commonly abundant obligate anaerobes (Gardnerella/Prevotella relative abundances combined), except for M. hominis, which correlated positively with Gardnerella and Prevotella (rs = 0.46, p = 2.6e−09 and rs = 0.47, p = 1.4e−09, respectively). In contrast, there was a negative correlation (rs = −0.3, p = 2.2e−04) between M. hominis and Lactobacillus species (Fig. S1).

Figure 5. (A–H) Spearman (rs) and Pearson (r) correlation plots showing the general theoretical relationship between facultative anaerobes (Lactobacillus species), obligate anaerobes (Gardnerella and Prevotella spp.) and THPP in the vaginal microbiome of the ethnic groups.

The strength and direction of the correlation is related to the magnitude and sign of the coefficient value (r): strong correlations, r between ±0.50 and ±1; moderate correlations, r = ±0.30 to ±0.49; weak correlations, r below +0.29. Statistically significant relationships, p < 0.05.

Discussion

Composition and diversity of the vaginal microbiome among the ethnic groups

In this study, the phylum Firmicutes (which includes the genus Lactobacillus) was the most dominant. A Lactobacillus-dominant vaginal ecosystem is most common among reproductive age women and is the mainstay of vaginal eubiosis (Ravel et al., 2011). The Actinobacteria phylum was mostly represented by the genera Gardnerella, Atopobium and to a lesser extent Bifidobacterium, while Bacteroidetes was mostly represented by Prevotella (Fig. 1 and Table S2). Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria are the dominant gut microbial phyla (Rinninella et al., 2019) and indeed the most likely origin of the vaginal microbiome (El Aila et al., 2011; Okoli et al., 2019). Lactobacillus occurred more than two-fold in AA women (91.8%) compared to women of European (German, 42.4%) and Asian (Indonesian, 45.0%) ancestries. It was also more prevalent in AA women than in other Black women (AC and AK, 26.1% and 34.4%, respectively). This contrasts with other research studies where AA women are expected to have a more diverse microbial composition than Caucasian women (Borgdorff et al., 2017; Fettweis et al., 2014; Ravel et al., 2011). However, the high relative abundance of lactobacilli in the AA cohort is in accordance with studies involving Nigerian and South African women (Anukam et al., 2019; Pendharkar et al., 2013). The observed deviation in microbial composition for AK women might be due to the occurrence of BV (Nugent scores > 7) in this group.

Of the Lactobacillus species, L. crispatus (21.9%) and L. iners (25.2%) were the two most dominant and were present in all ethnic groups. Other prevalent bacterial taxa with mean relative abundance >1% among the ethnic groups were: Prevotella (8.92%), Gardnerella (8.40%), Sneathia (4.57%), Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae (Shuttleworthia) (3.41%), Anaerococcus (2.57%) Megasphaera (2.30%) and Atopobium (2.12%). Prevotella abundance was highest among AC women (21.0%) compared to other ethnic groups where the mean relative abundance ranged from 2.11% (AA) to 12.0% (CG). Gardnerella was of low abundance in AA women (0.884%) compared to the other ethnic groups where the level ranged from 6.24% (AI) to 12.0% (CG). The high proportions of Prevotella and Gardnerella in all ethnic groups except for the AA women is indicative of a vaginal dysbiotic state and may further explain why lactobacilli was of lower relative abundance in these ethnic groups. Prevotella has been reported to enhance Gardnerella biofilm formation in BV which incorporates a number of facultative anaerobes (Castro, Machado & Cerca, 2019; Castro et al., 2021; Machado & Cerca, 2015; Patterson et al., 2010). Additionally, the sexually transmitted bacteria C. trachomatis identified at a more significant level in CG women could also have played a role in shifting the bacterial composition in this European group away from the expected Lactobacillus-dominated vaginal microbiome (Ziklo et al., 2018).

Overall, vaginal microbial community richness and evenness varied significantly across ethnicities (Kruskal–Wallis, p = 3.6e−11), giving the following rank: AI > AK > CG > AC > AA (Fig. 2A and Table S4). Similarly, beta (species) diversity was statistically significant (PERMANOVA, p = 0.001) among the ethnic groups (Fig. 2B and Table S4). Beta diversity could be explained by a number of differentiating bacterial taxa as determined by linear discriminant analysis: AA women by the higher abundance of L. crispatus, AC women by the predominant Prevotella spp., AI women mainly by THPP (such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus and Peptostreptococcus), AK women by Porphyromonas and Corynebacterium, and CG women by Bifidobacterium, Veillonella and Gamella (Fig. 3). At the individual level, the vaginal bacterial composition for each woman in this study represented a snapshot of a unique transient microbial signature. Microbial signatures vary temporally with changes in intrinsic (e.g., menstrual cycle) and extrinsic factors (e.g., sexual activity and antibiotic therapy) (Gajer et al., 2012). There was no definable core microbiome or singular vaginal microbiome signature identified at the species level among all women. This is perhaps a consequence of the involvement of a plethora of confounding variables (such as menstrual cycle phase and hormonal levels, age, parity, marital status, coitus, body mass index [BMI], diet, culture, etc.). The microbial composition of the vaginal microbiome is also reportedly influenced in part by factors such as geography, diet, culture and host genetics (Gupta, Paul & Dutta, 2017; Si et al., 2017) which are all distinctive components of ethnicity. Classification of the vaginal bacterial composition into a number of well-defined structures (Ravel et al., 2011) and subtypes, especially with respect to non-Lactobacillus CSTs, can serve as an alternative to a core microbiome in understanding the relationship between vaginal microbiome and vaginal health.

Structure of the vaginal microbiome in various ethnic groups

Vaginal bacterial communities among the ethnic groups clustered into eight CSTs (Table 2). Of the original community state types (CST I–V) (Ravel et al., 2011), CST V (L. jensenii) was not identified and CST II (L. gasseri) was only present in 0.66% of the women. The rarity of CST II and V in the vaginal microbiome of women in this study is in keeping with other studies (Chee, Chew & Than, 2020; Doyle et al., 2018). CST I (L. crispatus) and CST III (L. iners) were the most prevalent Lactobacillus—dominant CSTs, 21.9% and 25.2%, respectively. CST I tends to be associated with vaginal microbiota eubiosis (healthy vaginal state) while CST III (and CST IV) with dysbiosis, as for example, in BV (Lehtoranta et al., 2020; Ravel et al., 2011). In this study, CST IV clustered into three subtypes (CST IV–A, IV–B and IV–C) where CST IV–A represented a polymicrobial vaginal microbiome with G. vaginalis being most dominant but having a relative abundance less than 50%. CST IV–B was also polymicrobial with high proportions of Prevotella spp. (RA < 50%). CST IV–C also represented a polymicrobial state with genera other than Gardnerella or Prevotella being more dominant (RA < 50%). This subtype (CST IV–C) resembled subtypes CST–IVA and IV–B defined in earlier studies by Gajer et al. (2012) and Romero et al. (2014), where CST IV–A was differentiated based on higher abundance of Peptoniphilus spp., Anaerococcus spp., Corynebacterium spp., and Finegoldia spp., with respect to Lactobacillus species, while CST IV–B was defined by higher abundance of Atopobium spp., in addition to Parvimonas spp., Sneathia spp., Prevotella and Gardnerella. A Gardnerella—dominant CST, classified here as CST VI, has also been identified in African Malawian, African Ghanaian and African Surinamese women (Borgdorff et al., 2017; Doyle et al., 2018) as well as in a group of Caucasian Italian women (De Seta et al., 2019). We also identified a Prevotella—dominant vaginal microbiome which was classified as CST VII. CST VIII was differentiated by a high relative abundance (>50%) of a THPP (Enterococcus, Escherichia-Shigella, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Peptostreptococcus species). CST VIII in this study resembles aerobic vaginitis (AV) described as an inflammatory vaginal microbial dysbiotic state predominated by enteric commensals (e.g., Enterococcus and Escherichia–Shigella) or pathogens (Donders, Bellen & Rezeberga, 2011). Finally, CST IX was described here as a CST dominated by any microbe other than Lactobacillus, Gardnerella or Prevotella species with a relative abundance less than 50%. CST IX included a Bifidobacterium breve—dominant (RA > 98%) vaginal microbiome in one of the CG women. This distinct CST has also been identified in Italian, Turkish and Moroccan women (Borgdorff et al., 2017; De Seta et al., 2019). Bifidobacteria (inclusive of B. breve and B. longum) isolated from vaginal samples have been shown to inhibit pathogens (such as Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli) in vitro (Korshunov et al., 1999). Bifidobacterium spp. are lactic acid–producing bacteria and as such it is likely, theoretically, that this CST emerged in the presence of a Lactobacillus—deficient vaginal environment to guard against the proliferation of pathogenic anaerobes. This concept is supported, in part, by a study involving Thai women where researchers found vaginal Bifidobacterium spp. (B. bifidum, B. longum, B. breve and B. dentium) to be significantly higher in women with BV (Amsel’s criteria) (33.3%) compared to healthy women (11.7%) (Utto et al., 2017). In a limited Iranian study, high concentrations of Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp., as determined by qPCR assay, were found among healthy women (Bakhshi et al., 2019) suggesting a potential positive role of Bifidobacterium in vaginal health. In our study, decreasing proportions (% RA) of B. breve and B. longum, were not associated with a significant decrease in the mean RA of Lactobacillus spp. (r = −0.76, p = 0.35; 95% confidence interval (CI) [−0.23 to 0.084] and r = −0.13, p = 0.10; 95% CI [−0.29 to 0.056], respectively) indicating that the RA of Bifidobacterium is independent of Lactobacillus species and is probably influenced by other changes in the local environment. Vaginal microbiome structures (i.e., CSTs) exhibit different levels of stability and can shift temporally from one structure to a next depending on the presence of local or extragenital stressors (Ahrens et al., 2020; Gajer et al., 2012).

Correlations between THPP, Lactobacillus spp., G. vaginalis and Prevotella

The total relative abundance of THPP (with RA > 0.90%) among the five ethnic groups was 5.24%. These were Streptococcus (1.52%), Escherichia–Shigella (1.14%), Enterococcus (1.02%), Staphylococcus (0.954%), Peptostreptococcus (0.967%), U. parvum (0.383%) and M. hominis (0.223%). When dominant, their relative abundance ranged from 54% to 88%. All THPP, except the Mollicutes (Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma), were predominant in 14% of Asian Indonesian women and 13% of African Kenyan women. THPP are of medical importance because they are associated with chronic inflammation (Chow, Tang & Mazmanian, 2011; Jochum & Stecher, 2020) and autoimmune disorders, especially Mycoplasma (Roachford, Nelson & Mohapatra, 2017, 2019; Sherbet, 2009). As is known, Lactobacillus spp. inhibit the growth of THPP, pathogens and other competitive obligate anaerobes in healthy vaginal ecosystems. It is likely that THPP survive and persist within the vagina due to their integration into protective biofilms formed by G. vaginalis and Prevotella (Patterson et al., 2007). Correlations between THPP and the most common facultative and obligate anaerobes (Lactobacillus spp., G. vaginalis and Prevotella) were examined (Figs. 5 and S1). In this study, the relative abundance of both Gardnerella and Prevotella decreased as the relative proportions of Lactobacillus spp. increased (rs = −0.7, p = 2.1e−06 and rs = −0.62, p < 2.2e−16, respectively) in accordance with a longitudinal study by Gajer et al. (2012) where CST III was shown to shift to CST IV–B, and more recently in a data meta-analysis by van de Wijgert et al. (2020) in which the relative abundance of lactobacilli and BV—anaerobes showed a strong negative correlation. As anticipated, we found a significantly moderate positive correlation (rs = 0.52, p = 4.2e−12) between the obligate anaerobes Prevotella and Gardnerella. P. bivia, when incorporated into G. vaginalis biofilms, upregulates the expression of a G. vaginalis biofilm maintenance gene (HMPREF0424_0821) (Castro et al., 2021), in turn G. vaginalis enhances biofilm formation by P. bivia (Machado, Jefferson & Cerca, 2013). There were moderate positive correlations between M. hominis and Gardnerella (r = 0.46, p = 2.6e−09) and Prevotella (r = 0.47, p = 1.4e−09). Prevotella-enhanced Gardnerella biofilms are known to harbour THPP such as Mycoplasma.

Limitations of study

In this study with a small sampling size (N = 151), the potential effects of confounders (such as age disparities, sociodemographic characteristics, menstrual status, sexual activity etc.) on microbial composition were not analysed due to unavailability of data for subsamples from the various ethnic groups. Further, different sampling techniques were utilized and not all women were screened for STIs and BV (via Amsel’s or Nugent’s criteria) in some groups by the associated researchers. These factors negatively impact any meaningful interpretation of inter-ethnic comparative analyses of the various vaginal microbiomes. In addition, parametric (e.g., ANOVA) and correlation (e.g., Spearman’s rank correlation) statistical analyses between two or more features within the vaginal microbiome must be interpreted with caution as these tests are not optimised for microbiome datasets which are high-dimensional (consisting of the co-occurrence of thousands of microbes that influence each other) (Knight et al., 2018). Nonetheless, the strength of this study lies in the use of a more diverse group of women of different ethnicities spanning the Western to Eastern global hemispheres to give a more comprehensive and descriptive assessment of the polymicrobial community state type and subtypes.

Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrated that the microbial composition and structure of vaginal microbiomes differed among various ethnicities. However, the high proportion of Lactobacillus-dominated vaginal microbiomes in the African American ethnic group seemed to suggest that CST IV might not be the norm in black women as has been posited in some studies. We also found that vaginal microbial structures were not limited to the Lactobacillus species (L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners and L. jensenii) initially used to classify community state types. In addition, non-Lactobacillus-dominated vaginal microbiomes were prevalent and clustered into several CSTs and subtypes resembling bacterial vaginosis and aerobic vaginosis. THPP negatively correlated with Lactobacillus species but not with the obligate anaerobes (Prevotella/Gardnerella), possibly as a consequence of their differential integration into Prevotella-enhanced Gardnerella biofilms. Larger scale metagenomic studies across diverse ethnicities involving quantitative measurements of bacterial concentrations and visualization of THPP in vaginal biofilms are required to better understand the relationship between CSTs and ethnicity, as well as the association of THPP with other anaerobes within the vaginal microbiome.

Supplemental Information

Correlation plots. Spearman (rs) and Pearson (r) correlation plots show the theoretical relationship between facultative anaerobes (Lactobacillus species), obligate anaerobes (Gardnerella and Prevotella spp.) and pathobionts in the vaginal microbiome of the ethnic groups.

Acknowledgments

Sequencing of vaginal samples from Afro-Caribbean women was performed at J. Craig Venter Institute (La Jolla, CA, USA). We are grateful for facilities afforded by the Head, Department of Biological and Chemical Sciences, University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus. The authors thank all volunteers who participated in this research.

Funding Statement

The authors received no funding for this work.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Orville St. E. Roachford conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analysed the data, prepared figures and tables, and approved the final draft.

Angela T. Alleyne performed database search, reviewed drafts of the article and approved the final draft.

Karen E. Nelson performed database search, reviewed drafts of the article and approved the final draft.

Human Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

Research within this study was approved (IRB# 170710-B) by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) and Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The nucleotide sequence data for 16S rRNA V4 are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA), PRJEB34744; MGnify at EMBL-EBI, MGYS00005125; and MG-RAST, mgp89180.

References

- Ahrens et al. (2020).Ahrens P, Andersen LOB, Lilje L, Johannesen TB, Dahl EG, Baig S, Jensen Jørgen S, Falk L, Dean D. Changes in the vaginal microbiota following antibiotic treatment for Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis and bacterial vaginosis. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(7):e0236036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anukam et al. (2019).Anukam KC, Agbakoba NR, Okoli AC, Oguejiofor CB. Vaginal bacteriome of Nigerian women in health and disease: a study with 16S rRNA metagenomics. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2019;36(1):96–104. doi: 10.4103/TJOG.TJOG_67_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshi et al. (2019).Bakhshi A, Delouyi ZS, Taheri S, Alivandi A, Mohammadzadeh N, Dabiri H. Comparative study of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in vaginal tract of individual with bacterial vaginosis and healthy control by quantitative PCR. Reviews in Medical Microbiology. 2019;30(3):148–154. doi: 10.1097/MRM.0000000000000186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer et al. (2017).Beamer MA, Austin MN, Avolia HA, Meyn LA, Bunge KE, Hillier SL. Bacterial species colonizing the vagina of healthy women are not associated with race. Anaerobe. 2017;45(1):40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, Lohse & Usadel (2014).Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgdorff et al. (2017).Borgdorff H, Van Der Veer C, Van Houdt R, Alberts CJ, De Vries HJ, Bruisten SM, Snijder MB, Prins M, Geerlings SE, Van Der Loeff MFS, Van De Wijgert JHHM. The association between ethnicity and vaginal microbiota composition in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buret et al. (2019).Buret AG, Motta JP, Allain T, Ferraz J, Wallace JL. Pathobiont release from dysbiotic gut microbiota biofilms in intestinal inflammatory diseases: a role for iron? Journal of Biomedical Science. 2019;26(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso et al. (2010).Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Peña AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods. 2010;7(5):335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso et al. (2011).Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, Fierer N, Knight R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(supplement_1):4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, Machado & Cerca (2019).Castro J, Machado D, Cerca N. Unveiling the role of Gardnerella vaginalis in polymicrobial Bacterial Vaginosis biofilms: the impact of other vaginal pathogens living as neighbors. The ISME Journal. 2019;13(5):1306–1317. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0337-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro et al. (2021).Castro J, Rosca AS, Muzny CA, Cerca N. Atopobium vaginae and prevotella bivia are able to incorporate and influence gene expression in a pre-formed gardnerella vaginalis biofilm. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):1–16. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee, Chew & Than (2020).Chee WJY, Chew SY, Than LTL. Vaginal microbiota and the potential of Lactobacillus derivatives in maintaining vaginal health. Microbial Cell Factories. 2020;19(1):1–24. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow, Tang & Mazmanian (2011).Chow J, Tang H, Mazmanian SK. Pathobionts of the gastrointestinal microbiota and inflammatory disease. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2011;23(4):473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Seta et al. (2019).De Seta F, Campisciano G, Zanotta N, Ricci G, Comar M. The vaginal community state types microbiome-immune network as key factor for bacterial vaginosis and aerobic vaginitis. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2019;10:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donders, Bellen & Rezeberga (2011).Donders GGG, Bellen G, Rezeberga D. Aerobic vaginitis in pregnancy. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2011;118(10):1163–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle et al. (2018).Doyle R, Gondwe A, Fan Y, Maleta K, Ashorn P, Klein N. A Lactobacillus -deficient vaginal microbiota dominates. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2018;84(6):e02150-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02150-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Aila et al. (2011).El Aila NA, Tency I, Saerens B, De Backer E, Cools P, dos Santos Santiago GL, Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, Temmerman M, Vaneechoutte M. Strong correspondence in bacterial loads between the vagina and rectum of pregnant women. Research in Microbiology. 2011;162(5):506–513. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feehily et al. (2020).Feehily C, Crosby D, Walsh CJ, Lawton EM, Higgins S, McAuliffe FM, Cotter PD. Shotgun sequencing of the vaginal microbiome reveals both a species and functional potential signature of preterm birth. NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes. 2020;6(1):50. doi: 10.1038/s41522-020-00162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fettweis et al. (2014).Fettweis JM, Paul Brooks J, Serrano MG, Sheth NU, Girerd PH, Edwards DJ, Strauss JF, Jefferson KK, Buck GA. Differences in vaginal microbiome in African American women versus women of European ancestry. Microbiology (United Kingdom) 2014;160(10):2272–2282. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.081034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajer et al. (2012).Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, Sakamoto J, Schütte UME, Zhong X, Koenig SSK, Fu L, Ma ZS, Zhou X, Abdo Z, Forney LJ, Ravel J. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(132):132ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Paul & Dutta (2017).Gupta VK, Paul S, Dutta C. Geography, ethnicity or subsistence-specific variations in human microbiome composition and diversity. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2017;8:229. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm et al. (2020).Holm JB, France MT, Ma B, McComb E, Robinson CK, Mehta A, Tallon LJ, Brotman RM, Ravel J. Comparative metagenome-assembled genome analysis of candidatus lachnocurva vaginae, formerly known as Bacterial Vaginosis-Associated Bacterium−1 (BVAB1) Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2020;10:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespers et al. (2017).Jespers V, Kyongo J, Joseph S, Hardy L, Cools P, Crucitti T, Mwaura M, Ndayisaba G, Delany-Moretlwe S, Buyze J, Vanham G, Van De Wijgert JHHM. A longitudinal analysis of the vaginal microbiota and vaginal immune mediators in women from sub-Saharan Africa. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12198-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochum & Stecher (2020).Jochum L, Stecher B. Label or concept – what is a pathobiont? Trends in Microbiology. 2020;28(10):789–792. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight et al. (2018).Knight R, Vrbanac A, Taylor BC, Aksenov A, Callewaert C, Debelius J, Gonzalez A, Kosciolek T, McCall L-I, McDonald D, Melnik AV, Morton JT, Navas J, Quinn RA, Sanders JG, Swafford AD, Thompson LR, Tripathi A, Xu ZZ, Zaneveld JR, Zhu Q, Caporaso JG, Dorrestein PC. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2018;16(7):410–422. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korshunov et al. (1999).Korshunov VM, Gudieva ZA, Efimov BA, Pikina AP, Smeianov VV, Reid G, Korshunova OV, Tiutiunnik VL, Stepin II. The vaginal Bifidobacterium flora in women of reproductive age. Zhurnal Mikrobiologii, Epidemiologii i Immunobiologii. 1999:74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtoranta et al. (2020).Lehtoranta L, Hibberd AA, Reimari J, Junnila J, Yeung N, Maukonen J, Crawford G, Ouwehand AC. Recovery of vaginal microbiota after standard treatment for bacterial vaginosis infection: an observational study. Microorganisms. 2020;8(6):875. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8060875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado & Cerca (2015).Machado A, Cerca N. Influence of biofilm formation by gardnerella vaginalis and other anaerobes on bacterial vaginosis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2015;212(12):1856–1861. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado, Jefferson & Cerca (2013).Machado A, Jefferson K, Cerca N. Interactions between Lactobacillus crispatus and bacterial vaginosis (BV)-associated bacterial species in initial attachment and biofilm formation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14(6):12004–12012. doi: 10.3390/ijms140612004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa et al. (2018).Moustafa A, Li W, Singh H, Moncera KJ, Torralba MG, Yu Y, Manuel O, Biggs W, Venter JC, Nelson KE, Pieper R, Telenti A. Microbial metagenome of urinary tract infection. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):4333. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoli et al. (2019).Okoli AC, Agbakoba NR, Ezeanya CC, Oguejiofor CB, Anukam KC. Comparative abundance and functional biomarkers of the vaginal and gut microbiome of Nigerian women with bacterial vaginosis: a study with 16S rRNA metagenomics. Journal of Medical Laboratory Science. 2019;29:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson et al. (2007).Patterson JL, Girerd PH, Karjane NW, Jefferson KK. Effect of biofilm phenotype on resistance of Gardnerella vaginalis to hydrogen peroxide and lactic acid. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;197(2):170.e1–170.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson et al. (2010).Patterson JL, Stull-Lane A, Girerd PH, Jefferson KK. Analysis of adherence, biofilm formation and cytotoxicity suggests a greater virulence potential of Gardnerella vaginalis relative to other bacterial-vaginosis-associated anaerobes. Microbiology. 2010;156(2):392–399. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034280-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendharkar et al. (2013).Pendharkar S, Magopane T, Larsson PG, de Bruyn G, Gray GE, Hammarström L, Marcotte H. Identification and characterisation of vaginal lactobacilli from South African women. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2013;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2020).R Core Team . Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- Ravel et al. (2011).Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SSK, McCulle SL, Karlebach S, Gorle R, Russell J, Tacket CO, Brotman RM, Davis CC, Ault K, Peralta L, Forney LJ. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(supplement_1):4680–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinninella et al. (2019).Rinninella E, Raoul P, Cintoni M, Franceschi F, Miggiano GAD, Gasbarrini A, Mele MC. What is the healthy gut microbiota composition? A changing ecosystem across age, environment, diet, and diseases. Microorganisms. 2019;7(1):14. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roachford et al. (2021).Roachford OSE, Alleyne AT, Kuelbs C, Torralba MG, Nelson KE. The cervicovaginal microbiome and its resistome in a random selection of Afro-Caribbean women. Human Microbiome Journal. 2021;20(8):100079. doi: 10.1016/j.humic.2021.100079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roachford, Nelson & Mohapatra (2017).Roachford OSE, Nelson KE, Mohapatra BR. Comparative genomics of four Mycoplasma species of the human urogenital tract: analysis of their core genomes and virulence genes. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2017;307(8):508–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roachford, Nelson & Mohapatra (2019).Roachford O, Nelson KE, Mohapatra BR. Virulence and molecular adaptation of human urogenital mycoplasmas: a review. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 2019;33(1):689–698. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2019.1607556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero et al. (2014).Romero R, Hassan SS, Gajer P, Tarca AL, Fadrosh DW, Nikita L, Galuppi M, Lamont RF, Chaemsaithong P, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, Ravel J. Correction to: the composition and stability of the vaginal microbiota of normal pregnant women is different from that of non-pregnant women. Microbiome. 2014;2:1–19. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segata et al. (2011).Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biology. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbet (2009).Sherbet G. Bacterial infections and the pathogenesis of autoimmune conditions. British Journal of Medical Practitioners. 2009;2:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Si et al. (2017).Si J, You HJ, Yu J, Sung J, Ko GP. Prevotella as a hub for vaginal microbiota under the influence of host genetics and their association with obesity. Cell Host & Microbe. 2017;21(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utto et al. (2017).Utto P, Teanpaisan R, Piwat S, Chandeying V. Assessment of prevalence, adhesion and surface charges of bifidobacterium spp. Isolated from Thai women with bacterial vaginosis and healthy women. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2017;100:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wijgert et al. (2020).van de Wijgert JHHM, Verwijs MC, Gill AC, Borgdorff H, van der Veer C, Mayaud P. Pathobionts in the vaginal microbiota: individual participant data meta-analysis of three sequencing studies. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2020;10:1136. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventolini (2015).Ventolini G. Vaginal lactobacillus: biofilm formation in vivo–clinical implications. International Journal of Women’s Health. 2015;7:243–247. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S77956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. (2010).Zhou X, Hansmann MA, Davis CC, Suzuki H, Brown CJ, Schütte U, Pierson JD, Forney LJ. The vaginal bacterial communities of Japanese women resemble those of women in other racial groups. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology. 2010;58(2):169–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziklo et al. (2018).Ziklo N, Vidgen ME, Taing K, Huston WM, Timms P. Dysbiosis of the vaginal microbiota and higher vaginal kynurenine/tryptophan ratio reveals an association with Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2018;8:1. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Correlation plots. Spearman (rs) and Pearson (r) correlation plots show the theoretical relationship between facultative anaerobes (Lactobacillus species), obligate anaerobes (Gardnerella and Prevotella spp.) and pathobionts in the vaginal microbiome of the ethnic groups.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The nucleotide sequence data for 16S rRNA V4 are available in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA), PRJEB34744; MGnify at EMBL-EBI, MGYS00005125; and MG-RAST, mgp89180.