Abstract

Background:

In February 2018, Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommended tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during pregnancy to protect newborns against pertussis infection. We sought to describe pre- and postrecommendation trends in Tdap vaccination coverage among pregnant Ontario residents.

Methods:

Using linked health administrative databases, we conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study of all pregnant individuals who gave birth in Ontario hospitals between April 2012 and March 2020. We described Tdap vaccination patterns in pregnancy for the entire study period and before and after the NACI recommendation. We used log-binomial regression to identify characteristics associated with Tdap vaccination during pregnancy.

Results:

Among the 991 850 deliveries included, 7.0% of pregnant individuals received the Tdap vaccination during pregnancy. Vaccine coverage increased from 0.4% in 2011/12 to 29.2% in 2019/20. Coverage was highest among individuals who were older, had no previous live births, had adequate prenatal care and received maternity care primarily from a family physician. After adjustment, characteristics associated with lower coverage included younger maternal age, having a multiple birth, residing in a rural location and higher area material deprivation. In 2019/20, 71.0% of vaccinated individuals received the Tdap vaccination during the recommended gestational window (27–32 wk). Stratified analyses of the pre- and postrecommendation cohorts yielded similar findings to the main analyses with a few gradient differences after adjustment.

Interpretation:

During pregnancy, Tdap vaccination coverage increased substantially in Ontario between 2011/12 and 2019/20, most notably after recommendations for universal Tdap vaccination during pregnancy began in Canada. To further improve vaccine coverage in the obstetric setting, public health strategies should consider tailoring their programs to reach subpopulations with lower vaccine coverage.

Pertussis, a highly infectious vaccine-preventable disease, remains a notable cause of infant morbidity and death.1,2 From 2005 to 2011, the average incidence of pertussis among Canadian infants (< 1 yr) was 72.2 per 100 000 and in 2012, a notable pertussis surge increased this rate to 120.8 per 100 000.3 Despite high levels of childhood coverage with pertussis-containing vaccines, about 1 to 4 pertussis-related deaths occur in Canada each year, predominantly among the youngest infants who have not completed their primary vaccine series.4 Pertussis vaccination during pregnancy, using an acellular pertussis-containing vaccine (tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis [Tdap] vaccine), confers passive protection to infants through the transfer of maternal vaccine-derived antibodies before birth.5 To reduce the burden of pertussis among young infants, the United States6 and the United Kingdom7 issued recommendations in 2011/2012 advising all pregnant individuals to receive the Tdap vaccination during every pregnancy. Postimplementation evaluations of these maternal Tdap vaccination strategies showed reassuring evidence on both safety8,9 and effectiveness.10–14 For this reason, Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) released recommendations in February 2018 advising routine Tdap vaccination between 27 and 32 weeks’ gestation, 15 followed by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, which recommended Tdap vaccination between 21 and 32 weeks.16 During this time, influenza and Tdap were the only 2 vaccines routinely recommended during pregnancy in Canada.

Monitoring pertussis vaccination during pregnancy is essential for assessing adoption of these recommendations and can help identify groups with low coverage. Internationally, several epidemiologic studies have evaluated maternal pertussis vaccine policies by reporting trends and determinants of coverage.17–21 In Canada, a nationally representative cross-sectional survey estimated maternal pertussis vaccination coverage, by province and territory, among 4607 pregnant individuals who delivered between September 2018 and March 2019;22 43% of respondents nationally, and 40% in Ontario, reported having received Tdap vaccination during pregnancy. We aimed to examine trends and factors associated with Tdap vaccination among all pregnant individuals in Ontario over time, from 2012 to 2020.

Methods

We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study using Ontario health administrative data sets housed at ICES (https://www.ices.on.ca). We identified pregnant individuals aged 12 to 50 years who delivered in Ontario hospitals between Apr. 1, 2012, and Mar. 31, 2020, encompassing 6 years before the NACI Tdap recommendation and 2 years after the recommendation.

In the years preceding the 2018 recommendation for Tdap vaccination, some Canadian maternity care providers were already vaccinating pregnant individuals against pertussis, likely owing to reported outbreaks in other countries, success of programs in the US6 and the UK7 and advancing research on safety.8,9 In 2008, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada released a clinical practice guideline advising that the decision to administer Tdap vaccinations be made on a case-by-case basis, considering the overall risk of infection during pregnancy.23 Individuals who were at low risk of pertussis infection and were due for their 10-year booster were advised to receive Tdap vaccination during the postpartum period.23 In a 2014 statement, NACI similarly recommended to offer Tdap vaccination to pregnant individuals only in special circumstances (e.g., regional outbreaks, not previously vaccinated in adulthood).3 Until April 2022,22,24 Ontario was among the few provinces lacking a publicly funded program for routine Tdap vaccination during pregnancy; thus, participants captured in our study were limited to 1 publicly funded adult Tdap dose. As administering Tdap vaccinations during pregnancy is outside the scope of practice for midwives and pharmacists in Ontario,25–27 pregnant patients predominately receive Tdap vaccination from either family physicians or obstetricians.

Data sources

We used the ICES MOMBABY database, which contains linked maternal–newborn hospital records, to identify individuals with a live birth and obtain gestational age, maternal age and parity. The Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database, which captures all hospital admissions, was used to identify individuals with a stillbirth and obtain medical diagnoses and procedures. The Registered Persons Database provided information on neighbourhood income, region of residence and health care eligibility. The Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) physician billing claims database was used to identify Tdap vaccinations and prenatal care visits. The Ontario Marginalization Index was used for census data to quantify the level of marginalization in Ontario. Lastly, the ICES Physician Database was used to identify prenatal care provider specialties. Appendix 1, eTable 1 (www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/4/E1017/suppl/DC1) contains details on each data source. Data sets were deterministically linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. Diagnostic and procedural codes were from the Canadian implementation of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision and the Canadian Classification of Health Interventions, respectively. Records were excluded for the following reasons: administrative (invalid identifier, duplicate record and linkage warning), pregnant individual not an Ontario resident, an individual without continuous OHIP enrolment throughout pregnancy, pregnant individual younger than 12 years or older than 50 years and biologically implausible birthweight or gestational age combination (according to a Canadian reference standard).28

Exposure and outcome measurement

The Tdap vaccination, ascertained using billing code G847 in the OHIP database, was classified as occurring during pregnancy if administered 14 days after the estimated date of the last menstrual period (calculated by subtracting gestational age from date of birth) to 1 day before delivery. We described Tdap vaccination by maternal characteristics (age, parity, preexisting chronic conditions, neighbourhood income quintile, marginalization indices and region of residence), pregnancy characteristics (multiple gestation, prenatal care adequacy index29 [Appendix 1, eAppendix 1]), fiscal year of conception and practice specialty of prenatal care provider. Appendix 1, eTable 2 contains definitions and codes for these variables. Regional variation was assessed using groupings of Ontario’s health regions (Local Health Integration Networks).30

Marginalization was based on the 4 area-based indices within the Ontario Marginalization Index:31 residential instability (housing instability), material deprivation (poverty and socioeconomic status), dependency (high percentage of residents without employment income) and ethnic concentration (high concentration of recent immigrants or visible minorities). For care provider characteristics, we identified visits to family physicians and obstetricians (defined by specialty variable in the ICES Physician Database) with an OHIP fee code related to prenatal care (Appendix 1, eTable 3). Pregnant individuals were categorized by type of physician (family physician or obstetrician) who provided the majority (≥ 75%) of prenatal care. If neither type provided 75% or more of prenatal care, the category “mix of providers” was assigned. We stratified the study population into periods before and after the NACI recommendation for Tdap vaccination to assess whether there were any differences in maternal characteristics associated with Tdap vaccination coverage across these 2 periods. Because the NACI recommendation (published Feb. 1, 2018) was for Tdap vaccination between 27 and 32 weeks’ gestation, we categorized records as postrecommendation if individuals were pregnant for less than 27 weeks’ gestation on Feb. 1, 2018, or conceived after this date. Completed pregnancies, or those that were already 27 weeks’ gestation or more on Feb. 1, 2018, were considered prerecommendation (Appendix 1, eTable 2).

Statistical analysis

Records missing covariate information (< 1%) were excluded. We calculated Tdap vaccination coverage with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), estimated using the Wald method, in the overall study population and across each characteristic. Log-binomial regression was used to calculate rate ratios and 95% CIs adjusting for the following potential confounders: maternal age, parity, fiscal year of conception, maternal medical conditions, multiple birth, neighbourhood income quintile, marginalization indices, adequacy of prenatal care, specialty of prenatal care provider, rural residence and health region (Local Health Integration Networks). Individuals could contribute more than 1 pregnancy during the study period; however, we did not account for this in our analysis as the cluster sizes were small and adjustment for clustering did not affect our findings. We stratified the study population into pre- and postrecommendation subgroups to investigate whether factors associated with coverage were different in these 2 periods. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

Ethics approval

Research ethics board approval was acquired from the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Ethics Board (protocol no. 18/10PE), the Ottawa Hospital Science Network Research Ethics Board (protocol no. 20180432-01H) and the ICES Privacy Office (protocol no. 2018 0901 166 000).

Results

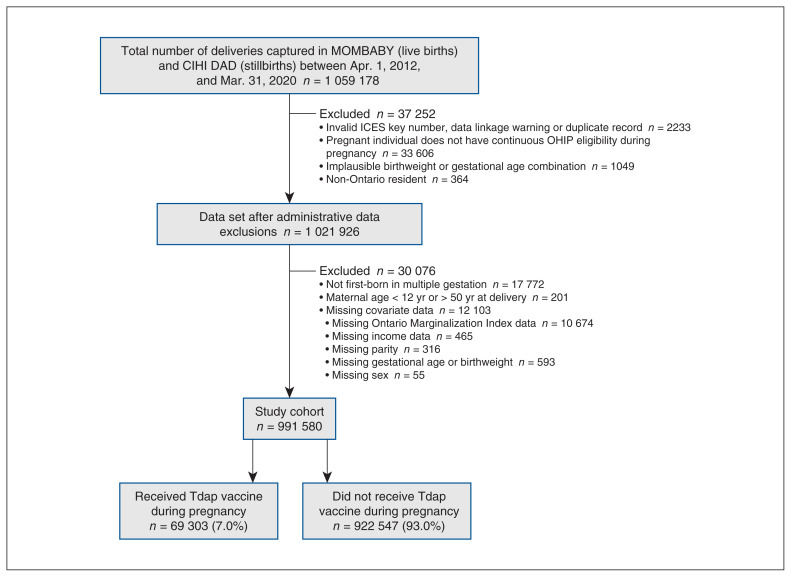

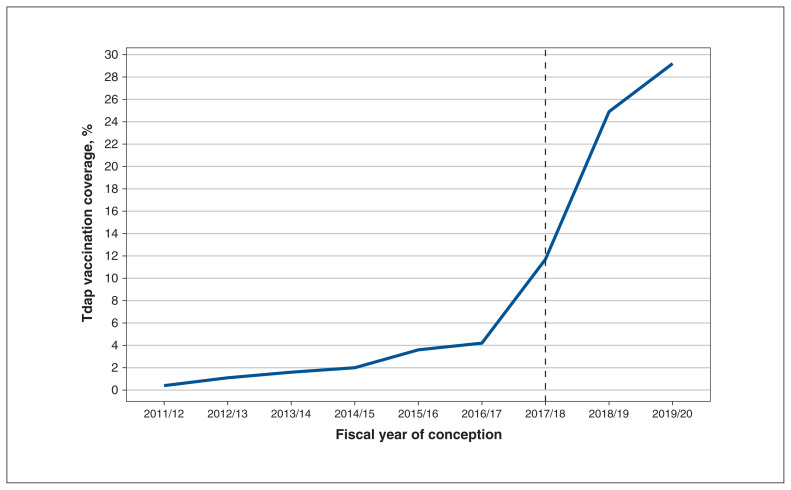

From April 2012 to March 2020, there were 1 059 178 Ontario deliveries of a live birth or stillbirth; among the 991 850 remaining after exclusions, 69 303 (7.0%) had received the Tdap vaccine during pregnancy (Figure 1). Among pregnant Ontario residents, Tdap vaccination rose from 0.4% among pregnancies conceived in 2011/2012 to 29.2% in 2019/2020 (Table 1); the increase was sharpest between 2017/2018 and 2018/2019 (11.7% and 24.9%, respectively; a 13.2% increase) after NACI’s recommendation (Figure 2). Vaccination was highest among older (> 30 yr) and nulliparous individuals. Those with pre-existing conditions (asthma, hypertension, diabetes and thyroid disease) had slightly higher coverage than did those without such conditions (8.0% v. 7.0%). Vaccine coverage ranged from 6% in the lowest neighbourhood household income quintile to 8% in the highest neighbourhood household income quintile. By region, coverage was highest among residents of the Greater Toronto Area (8.6%) and lowest among residents of Northern Ontario (3.6%). There was a gradient by material deprivation, with coverage lowest among the most marginalized areas measured by this dimension. Similarly, higher area dependency corresponded to lower coverage. By contrast, residential instability and ethnic concentration did not show clear gradients. The number of prenatal care visits was associated with Tdap vaccination coverage, with the highest rates among those who received adequate (8.2%) or intensive (7.9%) prenatal care. Type of provider was also influential, with coverage highest among individuals who received prenatal care primarily from a family physician (11.0%).

Figure 1:

Study flow diagram. Note: CIHI = Canadian Institute for Health Information, DAD = Discharge Abstract Database, OHIP = Ontario Health Insurance Plan, Tdap = tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis.

Table 1:

Tdap vaccination during pregnancy, by sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics

| Characteristic | All births, no. (%)* | No. vaccinated | Vaccine coverage, % (95% CI) | Unadjusted rate ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 991 850 (100.0) | 69 303 | 7.0 (6.9–7.0) | – | – |

| Maternal age, yr | |||||

| < 20 | 19 628 (2.0) | 622 | 3.2 (2.9–3.4) | 0.41 (0.38–0.44) | 0.58 (0.53–0.62) |

| 20–24 | 99 218 (10.0) | 4298 | 4.3 (4.2–4.5) | 0.56 (0.54–0.58) | 0.69 (0.67–0.71) |

| 25–29 | 262 061 (26.4) | 17 283 | 6.6 (6.5–6.7) | 0.86 (0.84–0.87) | 0.91 (0.90–0.93) |

| 30–34 | 369 744 (37.3) | 28 518 | 7.7 (7.6–7.8) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| ≥ 35 | 241 199 (24.3) | 18 582 | 7.7 (7.6–7.8) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) |

| Fiscal year of conception‡ | |||||

| 2011/12 | 95 494 (9.6) | 385 | 0.4 (0.4–0.4) | 0.097 (0.088–0.11) | 0.099 (0.089–0.11) |

| 2012/13 | 124 712 (12.6) | 1323 | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.26 (0.24–0.27) | 0.26 (0.34–0.27) |

| 2013/14 | 124 978 (12.6) | 2043 | 1.6 (1.6–1.7) | 0.39 (0.37–0.41) | 0.39 (0.37–0.41) |

| 2014/15 | 124 155 (12.5) | 2426 | 2.0 (1.9–2.0) | 0.47 (0.45–0.49) | 0.47 (0.44–0.49) |

| 2015/16 | 124 215 (12.5) | 4478 | 3.6 (3.5–3.7) | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) |

| 2016/17 | 123 417 (12.4) | 5122 | 4.2 (4.0–4.3) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 2017/18 | 122 830 (12.4) | 14 431 | 11.7 (11.6–11.9) | 2.83 (2.74–2.92) | 1.41 (1.34–1.48) |

| 2018/19 | 122 322 (12.3) | 30 400 | 24.9 (24.6–25.1) | 5.99 (5.82–6.16) | 2.37 (2.25–2.49) |

| 2019/20 | 29 727 (3.0) | 8695 | 29.2 (28.7–29.8) | 7.05 (6.83–7.28) | 2.74 (2.60–2.89) |

| Parity | |||||

| 0 (nulliparous) | 433 315 (43.7) | 35 637 | 8.2 (8.1–8.3) | 1.36 (1.34–1.38) | 1.38 (1.36–1.40) |

| ≥ 1 (multiparous) | 558 535 (56.3) | 33 666 | 6.0 (6.0–6.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Multiple birth | |||||

| No | 973 589 (98.2) | 68 364 | 7.0 (7.0–7.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 18 261 (1.8) | 939 | 5.1 (4.8–5.5) | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) | 0.77 (0.73–0.82) |

| Pre-existing maternal medical condition§ | |||||

| Asthma | 2138 (0.2) | 127 | 5.9 (5.0–7.0) | 0.85 (0.72–1.01) | – |

| Chronic hypertension | 3947 (0.4) | 283 | 7.2 (6.4–8.0) | 1.03 (0.92–1.15) | – |

| Diabetes | 8702 (0.9) | 417 | 4.8 (4.4–5.3) | 0.68 (0.62–0.75) | – |

| Heart disease | 4806 (0.5) | 294 | 6.1 (5.5–6.8) | 0.87 (0.78–0.98) | – |

| Thyroid disease | 13 389 (1.3) | 1466 | 10.9 (10.4–11.5) | 1.58 (1.50–1.66) | – |

| Any pre-existing maternal medical condition† | |||||

| No | 960 721(96.9) | 66 825 | 7.0 (6.9–7.0) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 31 129 (3.1) | 2478 | 8.0 (7.7–8.3) | 1.14 (1.10–1.19) | 0.96 (0.93–1.00) |

| Neighbourhood median family income quintile | |||||

| 1 (lowest) | 210 933 (21.3) | 12 713 | 6.0 (5.9–6.1) | 0.76 (0.74–0.77) | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) |

| 2 | 199 725 (20.1) | 13 890 | 7.0 (6.8–7.1) | 0.87 (0.85–0.89) | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) |

| 3 | 207 562 (20.9) | 14 430 | 7.0 (6.8–7.1) | 0.87 (0.85–0.89) | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) |

| 4 | 208 050 (21.0) | 15 080 | 7.2 (7.1–7.4) | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) |

| 5 (highest) | 165 580 (16.7) | 13 190 | 8.0 (7.8–8.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Rural residence | |||||

| No | 899 428 (90.7) | 63 968 | 7.1 (7.1–7.2) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Yes | 92 422 (9.3) | 5335 | 5.8 (5.6–5.9) | 0.81 (0.79–0.83) | 0.91 (0.88–0.93) |

| LHIN group¶ | |||||

| Central | 329 495 (33.2) | 23 010 | 7.0 (6.9–7.1) | 0.81 (0.79–0.83) | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) |

| East | 239 495 (24.2) | 19 784 | 8.3 (8.2–8.4) | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) |

| North | 50 815 (5.1) | 1853 | 3.6 (3.5–3.8) | 0.42 (0.40–0.44) | 0.58 (0.55–0.61) |

| Toronto | 92 261 (9.3) | 7964 | 8.6 (8.5–8.8) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| West | 279 784 (28.2) | 16 692 | 6.0 (5.9–6.1) | 0.69 (0.67–0.71) | 0.84 (0.82–0.86) |

| Marginalization indices** | |||||

| Residential instability quintile | |||||

| 1 (least marginalized) | 216 203 (21.8) | 14 721 | 6.8 (6.7–6.9) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 2 | 184 203 (18.6) | 13 131 | 7.1 (7.0–7.2) | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) |

| 3 | 180 923 (18.2) | 12 764 | 7.1 (6.9–7.2) | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) |

| 4 | 186 076 (18.8) | 12 270 | 6.6 (6.5–6.7) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) |

| 5 (most marginalized) | 224 445 (22.6) | 16 417 | 7.3 (7.2–7.4) | 1.07 (1.05–1.10) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) |

| Material deprivation quintile | |||||

| 1 (least marginalized) | 201 373 (20.3) | 18 272 | 9.1 (8.9–9.2) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 2 | 196 248 (19.8) | 14 869 | 7.6 (7.5–7.7) | 0.84 (0.82–0.85) | 0.93 (0.91–0.94) |

| 3 | 187 025 (18.9) | 12 578 | 6.7 (6.6–6.8) | 0.74 (0.73–0.76) | 0.85 (0.83–0.87) |

| 4 | 186 870 (18.8) | 11,977 | 6.4 (6.3–6.5) | 0.71 (0.69–0.72) | 0.80 (0.78–0.83) |

| 5 (most marginalized) | 220 334 (22.2) | 11,607 | 5.3 (5.2–5.4) | 0.58 (0.57–0.59) | 0.69 (0.67–0.71) |

| Dependency quintile | |||||

| 1 (least marginalized) | 335 957 (33.9) | 24 105 | 7.2 (7.1–7.3) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 2 | 209 933 (21.2) | 14 932 | 7.1 (7.0–7.2) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 1.06 (1.04–1.07) |

| 3 | 167 423 (16.9) | 11 454 | 6.8 (6.7–7.0) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) |

| 4 | 149 441 (15.1) | 10 371 | 6.9 (6.8–7.1) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 1.08 (1.06–1.11) |

| 5 (most marginalized) | 129 096 (13.0) | 8441 | 6.5 (6.4–6.7) | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) |

| Ethnic concentration quintile | |||||

| 1 (least marginalized) | 131 891 (13.3) | 7761 | 5.9 (5.8–6.0) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| 2 | 150 188 (15.1) | 10 103 | 6.7 (6.6–6.9) | 1.14 (1.11–1.18) | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) |

| 3 | 169 086 (17.0) | 12 385 | 7.3 (7.2–7.4) | 1.24 (1.21–1.28) | 1.10 (1.07–1.13) |

| 4 | 210 064 (21.2) | 15 860 | 7.6 (7.4–7.7) | 1.28 (1.25–1.32) | 1.13 (1.10–1.17) |

| 5 (most marginalized) | 330 621 (33.3) | 23 194 | 7.0 (6.9–7.1) | 1.19 (1.16–1.22) | 1.16 (1.13–1.20) |

| Prenatal care†† | |||||

| Intensive | 54 690 (5.5) | 4302 | 7.9 (7.6–8.1) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) |

| Adequate | 409 609 (41.3) | 33 468 | 8.2 (8.1–8.3) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Intermediate | 337 279 (34.0) | 21 379 | 6.3 (6.3–6.4) | 0.78 (0.76–0.79) | 0.88 (0.87–0.90) |

| Inadequate | 134 621 (13.6) | 7875 | 5.8 (5.7–6.0) | 0.72 (0.70–0.73) | 0.56 (0.55–0.57)§§ |

| No care or missing†,‡,§,¶,**,††,‡‡ | 55 651 (5.6) | 2279 | 4.1 (3.9–4.3) | 0.50 (0.48–0.52) | – |

| Composition of prenatal care visits | |||||

| No visits | 55 649 (5.6) | 2279 | 4.1 (3.9–4.3) | 0.68 (0.65–0.71) | 1.12 (1.07–1.17) |

| ≥ 75% with GP or FP | 141 591 (14.3) | 15 610 | 11.0 (10.9–11.2) | 1.82 (1.79–1.86) | 1.97 (1.94–2.01) |

| ≥ 75% with OBGYN | 606 758 (61.2) | 36 701 | 6.0 (6.0–6.1) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 1.00 (Ref.) |

| Mix of providers | 187 852 (18.9) | 14 713 | 7.8 (7.7–8.0) | 1.29 (1.27–1.32) | 1.31 (1.28–1.33) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, GP = general practitioner, FP = family physician, LHIN = Local Health Integration Network, OBGYN = obstetrician–gynecologist, REF = reference category, Tdap = tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis.

Column percentages.

The multivariable model included in all of the independent variables listed in this table, except a dichotomous variable for pre-existing medical conditions, was added instead of the individual conditions in this variable, and the category for inadequate prenatal care was combined with no care or missing prenatal care to allow for model convergence.

A fiscal year begins on Apr. 1 and ends on Mar. 31. As the cohort was created using the delivery date on the maternal record (Apr. 1, 2012, to Mar. 31, 2020), fiscal years 2011/12 and 2019/20 are incomplete, which explains the lower number of births shown in these 2 fiscal years.

Sum of each individual condition does not equal number of pregnant people with any condition, as categories were not mutually exclusive.

Local Health Integration Network groups were assigned according to the Ontario Ministry of Health (Appendix 1, eTable 2).

Scores corresponding to each of these 4 dimensions were previously divided into quintiles, where quintile 1 represents the least marginalized areas, and quintile 5, the most marginalized areas. Please see Appendix 1, eTable 2 for complete descriptions of what is captured in each of these 4 dimensions.

Adequacy of prenatal care characterized using the Revised-Graduated Prenatal Care Utilization Index.

Mother did not have any prenatal visits within our definition.

Estimate is for inadequate and no care or missing prenatal care combined.

Figure 2:

Tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination coverage by fiscal year of conception. The dotted line indicates the fiscal year in which Canadian recommendations for routine Tdap vaccination during pregnancy were released (February 2018).

Across the study period, nulliparity, high area residential instability and ethnic concentration, later year of conception and receiving prenatal care primarily from a family physician were associated with Tdap vaccination during pregnancy, whereas younger maternal age, multiple birth, presence of a pre-existing health condition, rural residence, high area material deprivation and receiving intermediate or inadequate prenatal care were associated with a reduced likelihood of vaccination (Table 1). No clear gradient in Tdap vaccination was observed across neighbourhood income quintiles; however, some geographic variation in vaccination was noted as residents of Northern Ontario had the lowest likelihood of Tdap vaccination receipt, even after adjustment for potential confounders (adjusted rate ratio 0.58, 95% CI 0.55–0.61).

After the NACI recommendation, Tdap vaccination coverage rose from 2.4% to 27.7% (Appendix 1, eTables 4 and 5). Residents of Eastern Ontario had the highest likelihood of vaccination in the prerecommendation period, whereas residents of the Greater Toronto Area were more likely to receive Tdap vaccination in the postrecommendation period. Higher area dependency corresponded with higher likelihood of vaccination in the prerecommendation period, but not in the postrecommendation period (Appendix 1, eTable 5). Receiving prenatal care primarily from a family physician was associated with higher coverage in both periods, but the association was stronger in the prerecommendation period compared with the postrecommendation period (adjusted rate ratio 3.51, 95% CI 3.39–3.63 and adjusted rate ratio 1.72, 95% CI 1.68–1.75, respectively). Similarly, inadequate prenatal care was associated with a lower likelihood of vaccination in both periods, but it was more pronounced in the prerecommendation period compared with the postrecommendation period (adjusted rate ratio 0.30, 95% CI 0.29–0.32 and adjusted rate ratio 0.64, 95% CI 0.62–0.65, respectively).

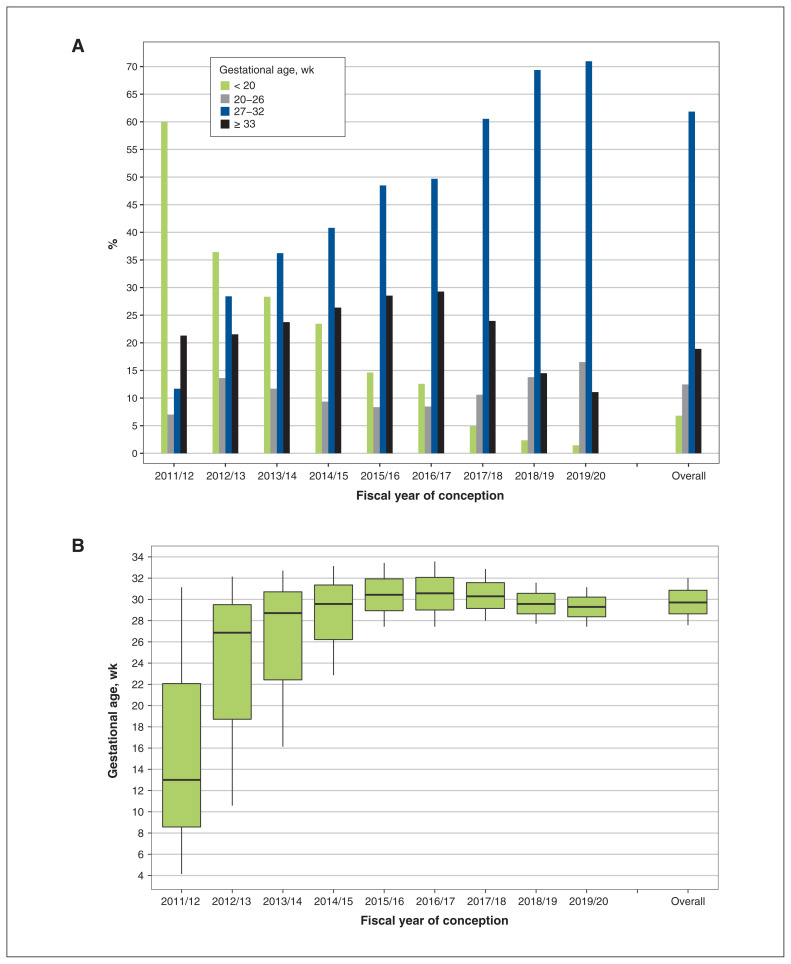

Gestational timing of Tdap vaccination overall and by year of conception is illustrated in Figure 3. Overall, 61.8% (42 861/69 303) of vaccinated pregnant individuals received Tdap vaccination within the recommended gestational age range (27–32 wk), but this percentage increased from 11.7% in 2011/12 to 71.0% in 2019/20 (Figure 3A). Among vaccinated individuals who conceived in 2011/12, 60.0% were vaccinated before 20 weeks’ gestation. Median gestational age at vaccination rose from 13 weeks in 2011/12 to almost 30 weeks in 2019/20 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3:

Gestational timing of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination overall and by fiscal year of conception. (A) Bar graph presenting the distribution of gestational age at which Tdap vaccination was received during pregnancy. (B) Box plot presenting the median gestational age at which Tdap vaccination was received during pregnancy (horizontal line within each box plot) and the interquartile range (vertical lines extending above and below each box).

Interpretation

Across an 8-year period in Ontario (April 2012 to March 2020), 6 of which preceded the NACI recommendation for routine Tdap vaccination during pregnancy, we identified 69 303 (7.0%) Ontario residents who were vaccinated with Tdap while pregnant. Coverage increased ninefold from 2.4% (prerecommendation) to 27.7% (postrecommendation), with the greatest increase occurring after the release of the NACI recommendation for routine Tdap vaccination during pregnancy. Our results show variations in Tdap vaccination coverage according to numerous characteristics including age, parity, location of residence, adequacy of prenatal care and practice specialty of prenatal care provider. Gestational timing of Tdap vaccination during pregnancy shifted in response to the NACI recommendation, as more than 70% of vaccinated individuals who conceived in 2019/20 received the Tdap vaccination during the recommended window of 27–32 weeks.

Lower vaccination rates among pregnant individuals who were younger, had less than adequate prenatal care, had greater area material deprivation or lived in lower-income neighbourhoods have been reported in studies of pertussis and influenza vaccination among pregnant populations.9,21,32–36 Our finding that the number of prenatal care visits was associated with higher vaccine coverage has been shown in other studies32–34,37,38 and can be attributed to more frequent contact with health care providers, creating more opportunities for vaccination.

Although vaccine recommendations are important, providing public funding for vaccination programs is also needed to increase vaccine access and coverage.39 Until April 2022, Ontario was among the few provinces without a publicly funded program for routine Tdap vaccination during pregnancy.22,24 In a qualitative study consisting of interviews with Canadian perinatal care providers (n = 44), several providers expressed concerns that lack of public funding for Tdap vaccination in Ontario and British Columbia has contributed to inequitable vaccine access;26 however, a recent national survey of Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy reported that fewer than 1% of pregnant individuals who were unvaccinated mentioned cost as the main reason.22

We found that individuals whose prenatal care was provided primarily by a family physician, rather than an obstetrician, had a greater likelihood of Tdap vaccination. A similar disparity was reported in a study of influenza vaccine coverage during pregnancy during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic in Ontario,34 and may reflect differences in practice and vaccine recommendation patterns. In a recent Canadian study,22 reasons for not receiving Tdap vaccination during pregnancy included not knowing that the vaccine was recommended during pregnancy (60%), not wanting to be vaccinated (16%) and the health care provider not offering the vaccine (11%). A US study noted that Tdap vaccination during pregnancy was impeded by factors such as insurance reimbursement, on-site storage issues and financial concerns.40 Limited on-site vaccine availability may hinder the administration of the Tdap vaccine by obstetricians. A recent multicentre observational study of 4 vaccine delivery models in Quebec found that coverage was higher when Tdap was offered to pregnant individuals in a family physician’s office or an obstetrics clinic, compared with a local community service centre, highlighting the importance of integrating vaccination into prenatal care.41 Health care provider recommendations and suitable storage and access have an effect on vaccine coverage during pregnancy.42–46 In a recent qualitative study, some Canadian maternity care providers expressed concerns that national recommendations for Tdap vaccination during pregnancy were prematurely released, before adequate infrastructure to support vaccine administration was established.26 The study also underscored the variability in midwives’ perceived role in vaccination, owing to the fact that vaccination is not traditionally within the scope of practice for midwives in many provinces.26 Training and implementation support should be available to encourage vaccination by all maternity care providers.

We found a shift in the gestational timing of vaccination across the study period. Most vaccinated individuals who conceived in 2011/12 received Tdap vaccination in the first trimester, suggesting vaccination during these earlier years may have been coincidental to pregnancy. An increase in vaccination during the recommended time frame was also observed, with more than 70% of vaccinated individuals receiving vaccination between 27 and 32 weeks’ gestation in 2019/20, compared with about 12% in 2011/12. A US study similarly found that Tdap vaccination during the recommended gestational age range rose from 52.5% to 91.8% after release of the 2012 Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices guidelines. 38 Our results suggest early adherence to Canada’s current recommendations, as most individuals who conceived in the postrecommendation period received Tdap vaccination within the gestational window conferring the greatest level of infant protection.

Strengths of this study include the use of multiple linked health administrative data sets, which allowed us to assemble a large population of pregnant individuals who were vaccinated with Tdap during pregnancy and assess coverage at a population level. The data sets provided information on maternal, pregnancy and care provider characteristics potentially related to vaccination practices and trends before, and slightly after, the NACI recommendation. Having the exact vaccination date enabled assessment of gestational timing — information that is relevant to policy evaluation.

Limitations

Our analyses depended on accurate fee coding; if Tdap vaccination did not generate a billing claim in the databases, we would have underestimated the true coverage. Whereas the sensitivity of the Tdap vaccination billing code is unknown in our study population, previous Ontario validation studies of OHIP billing claims for adult influenza and infant vaccination status (general and vaccine-specific codes) have shown high specificity (81%–96%) and positive predictive values (88%– 99%).47,48 Assuming specificity for the Tdap vaccination code is high, any nondifferential misclassification owing to reductions in sensitivity would have a minimal effect on our estimates. 49 We lacked information on whether unvaccinated individuals had been offered but refused vaccination, and their reasons for declining; therefore, we could not assess barriers to Tdap vaccination during pregnancy. Provider specialties captured in the physician database do not include midwives or other health care professionals who might have provided prenatal care, outside of family physicians and obstetricians. Further, OHIP billing for Tdap vaccination may differ by provider type, which could have potentially biased the observed association between maternity care provider and Tdap vaccination coverage. We restricted our cohort to individuals with uninterrupted OHIP insurance throughout pregnancy to ensure that we could identify Tdap vaccinations administered during pregnancy in the health administrative databases. It is possible that the characteristics of pregnant individuals with discontinuous or no provincial health insurance might be different. Although our results are based on a large populationbased sample, these results may not be generalizable to other obstetric populations. Lastly, several area-based measures were used in our analysis (e.g., income quintiles, marginalization indices) and may not accurately reflect relations with these characteristics at the individual level.

Conclusion

Our findings show an overall increase in Ontario’s Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy, particularly after the release of national recommendations for Tdap vaccination by NACI. We identified several factors associated with lower rates of Tdap vaccination; this information can inform initiatives to ultimately improve Tdap vaccination coverage among the pregnant population. Considering our study data extended until March 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, additional studies are needed to assess whether Tdap vaccination coverage during pregnancy continues to increase in Ontario, particularly with the recent expansion of public funding (effective April 2022),24 or whether these early gains have been affected by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative research on individual- and health system–level barriers affecting Tdap vaccination during pregnancy should also be a priority.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Toronto Community Health Profiles Partnership for providing access to the Ontario Marginalization Index.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Scott Halperin has received research grants or contracts from and has served on ad hoc advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, Merck, Janssen, Medicago, Entos IMV, CanSino, VBI, Moderna, Precision Nanosystems, AstraZeneca, Seqirus, Novavax and Dynavax (all unrelated to this study). Manish Sadarangani has been an investigator on projects funded by Pfizer, Merck, Moderna, Sanofi Pasteur, Seqirus, Symvivo, VBI Vaccines and GlaxoSmithKline (all unrelated to this study). All funds have been paid to his institute, and he has not received any personal payments. He is chair/deputy chair of 2 data safety monitoring boards for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trials, involving different vaccines. Kumanan Wilson is the CEO of CANImmunize Inc. and served as a member of the independent data monitoring committee for the Medicago SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trial (all unrelated to this study).

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Deshayne Fell, Natasha Crowcroft and Shelly Bolotin conceived the study and designed the initial study protocol and analytic approach. Romina Fakhraei, Jeff Kwong, Stephen Fung and William Petrcich made further contributions to the study design and analytic approach. Romina Fakhraei and William Petrcich linked the administrative data sources to create the study cohort and performed the statistical analyses, which were supervised by Deshayne Fell. Romina Fakhraei and Stephen Fung drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was supported by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT-159519 and MY7-161351) and by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the MOH and MLTC and the Canadian Institute for Health Information. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. Manish Sadarangani is supported by way of salary awards from the BC Children’s Hospital Foundation, the Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Data sharing: The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. Even though data-sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access can be granted to those meeting prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at https://www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors on request, with the understanding that the computer programs may rely on coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and, therefore, are inaccessible or may need modification.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/4/E1017/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Smith T, Rotondo J, Desai S, et al. Pertussis surveillance in Canada: trends to 2012. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2014;40:21–30. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v40i03a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson DW, Rohani P. Perplexities of pertussis: recent global epidemiological trends and their potential causes. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:672–84. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812003093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Advisory Committee. An Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): update on pertussis vaccination in pregnancy. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014. [accessed 2022 June 27]. Cat no HP40-93/2014E-PDF. Available: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/update-pertussis-vaccination-pregnancy-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pertussis (whooping cough): for health professionals. Ottawa: National Advisory Committee on Immunization; [accessed 2022 June 27]. modified 2020 Jan. 7. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/vaccine-preventable-diseases/pertussis-whooping-cough/health-professionals.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu Raya B, Edwards KM, Scheifele DW, et al. Pertussis and influenza immunisation during pregnancy: a landscape review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:e209–22. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CD) Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:131–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UK Health Security Agency. Vaccination against pertussis (whooping cough) for pregnant women. Information for healthcare professionals. London (UK): Public Health England; 2014. [accessed 2020 Nov. 17]. updated 2021 Sept. 6. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaccination-against-pertussis-whooping-cough-for-pregnant-women. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMillan M, Clarke M, Parrella A, et al. Safety of tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccination during pregnancy: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560–73. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gkentzi D, Katsakiori P, Marangos M, et al. Maternal vaccination against pertussis: a systematic review of the recent literature. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102:F456–63. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H, et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet. 2014;384:1521–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60686-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dabrera G, Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, et al. A case-control study to estimate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in protecting newborn infants in England and Wales, 2012–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:333–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amirthalingam G, Campbell H, Ribeiro S, et al. Sustained effectiveness of the maternal pertussis immunization program in England 3 years following introduction. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(Suppl 4):S236–43. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxter R, Bartlett J, Fireman B, et al. Effectiveness of vaccination during pregnancy to prevent infant pertussis. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20164091. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winter K, Cherry JD, Harriman K. Effectiveness of prenatal tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination on pertussis severity in infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:9–14. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Advisory Committee. An Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): update on immunization in pregnancy with tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and reduced acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. [accessed 2022 June 27]. Cat no HP40-207/2018d-PDF. modified 2019 Oct 9. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/update-immunization-prenancy-tdap-vaccine.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castillo E, Poliquin V. No. 357: immunization in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40:478–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin JB, Yu L, Watson D, et al. Pertussis Immunisation in Pregnancy Safety (PIPS) study: a retrospective cohort study of safety outcomes in pregnant women vaccinated with Tdap vaccine. Vaccine. 2018;36:5173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind HS, et al. Maternal Tdap vaccination: coverage and acute safety outcomes in the vaccine safety datalink, 2007–2013. Vaccine. 2016;34:968–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan JL, Baggari SR, McIntire DD, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after antepartum tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccination. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1433–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shakib JH, Korgenski K, Sheng X, et al. Tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis vaccine during pregnancy: pregnancy and infant health outcomes. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1422–6e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker JL, Rentsch CT, McDonald HI, et al. Social determinants of pertussis and influenza vaccine uptake in pregnancy: a national cohort study in England using electronic health records. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046545. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert NL, Guay M, Kokaua J, et al. Pertussis vaccination in Canadian pregnant women, 2018–2019. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2022;44:762–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2022.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruslin A, Steben M, Halperin S, et al. Infectious Diseases Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Immunization in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31:1085–101. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis) Vaccine Program. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health; Apr 1, 2022. [accessed 2022 June 27]. Available: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/immunization/docs/tdap_fs_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pertussis immunization in pregnancy in Ontario: scientific and technical considerations. Toronto: Public Health Ontario; 2018. [accessed 2022 June 27]. Available: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/Documents/P/2018/pertussis-immunization-pregnancy.pdf?sc_lang=en. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mijovic H, Greyson D, Gemmell E, et al. Perinatal health care providers’ approaches to recommending and providing pertussis vaccination in pregnancy: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open. 2020;8:E377–82. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20190215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaccinations in pregnancy. Toronto: Association of Ontario Midwives; [accessed 2022 June 27]. Available: https://www.ontariomidwives.ca/vaccinations-pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. Fetal/Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E35. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Quantifying the adequacy of prenatal care: a comparison of indices. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:408–18. discussion 419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connected care update [news] Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; [accessed 2022 Jan. 16]. modified 2019 Nov 14. Availble: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/news/connectedcare/2019/CC_20191113.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Ingen T, Matheson FI. The 2011 and 2016 iterations of the Ontario Marginalization Index: updates, consistency and a cross-sectional study of health outcome associations. Can J Public Health. 2022;113:260–71. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koepke R, Schauer SL, Davis JP. Measuring maternal Tdap and influenza vaccination rates: comparison of two population-based methods. Vaccine. 2017;35:2298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koepke R, Kahn D, Petit AB, et al. Pertussis and influenza vaccination among insured pregnant women: Wisconsin, 2013–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:746–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu N, Sprague AE, Yasseen AS, III, et al. Vaccination patterns in pregnant women during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2012;103:e353–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03404440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bödeker B, Walter D, Reiter S, et al. Cross-sectional study on factors associated with influenza vaccine uptake and pertussis vaccination status among pregnant women in Germany. Vaccine. 2014;32:4131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Healy CM, Ng N, Taylor RS, et al. Tetanus and diphtheria toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine uptake during pregnancy in a metropolitan tertiary care center. Vaccine. 2015;33:4983–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind H, et al. Receipt of pertussis vaccine during pregnancy across 7 Vaccine Safety Datalink sites. Prev Med. 2014;67:316–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DiTosto JD, Weiss RE, Yee LM, et al. Association of Tdap vaccine guidelines with vaccine uptake during pregnancy. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0254863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheifele DW, Ward BJ, Halperin SA, et al. Approved but non-funded vaccines: accessing individual protection. Vaccine. 2014;32:766–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehrotra A, Fisher AK, Mullen J, et al. Provider insight on surmounting specialty practice challenges to improve Tdap immunization rates among pregnant women. Heliyon. 2018;4:e00636. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Brousseau N, Guay M, et al. Coverage for pertussis vaccination during pregnancy with 4 models of vaccine delivery: a quasiexperimental, multicentre observational study. CMAJ Open. 2022;10:E56–63. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20210011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myers KL. Predictors of maternal vaccination in the United States: an integrative review of the literature. Vaccine. 2016;34:3942–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mak DB, Regan AK, Joyce S, et al. Antenatal care provider’s advice is the key determinant of influenza vaccination uptake in pregnant women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55:131–7. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Healy CM, Rench MA, Montesinos DP, et al. Knowledge and attitiudes of pregnant women and their providers towards recommendations for immunization during pregnancy. Vaccine. 2015;33:5445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kowal SP, Jardine CG, Bubela TM. “If they tell me to get it, I’ll get it. If they don’t …”: Immunization decision-making processes of immigrant mothers. Can J Public Health. 2015;106:e230–5. doi: 10.17269/cjph.106.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chamberlain AT, Seib K, Ault KA, et al. Factors associated with intention to receive influenza and tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccines during pregnancy: a focus on vaccine hesitancy and perceptions of disease severity and vaccine safety. PLoS Curr. 2015;7 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.d37b61bceebae5a7a06d40a301cfa819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwartz KL, Tu K, Wing L, et al. Validation of infant immunization billing codes in administrative data. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:1840–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1043499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz KL, Jembere N, Campitelli MA, et al. Using physician billing claims from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan to determine individual influenza vaccination status: an updated validation study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4:E463–70. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Understanding lack of validity: bias. In: Nieto Szklo M., editor. Epidemiology: Beyond the Basics. 2nd ed. Burlington (MA): Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2007. pp. 109–50. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.