Abstract

Background

Uptake of family planning (FP) services could prevent many unwanted pregnancies, and unsafe abortions and avert maternal deaths. However, women, especially from ethnic and religious minorities, have a low practice of contraceptives in Nepal. This study examined the knowledge and practices of modern contraceptive methods among Muslim women in Nepal.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 400 Muslim women in the Khajura Rural Municipality of Banke district. Data were collected using face to face structured interviews. Two outcome variables included i) knowledge of and ii) practices of contraceptives. Knowledge and practice scores were estimated using the list of questions. Using median as a cut-off point, scores were categorised into two categories for each outcome variable (e.g., good knowledge and poor knowledge). Independent variables were several sociodemographic factors. The study employed logistic regression analysis, and odds ratios (OR) were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) at a significance level of p<0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Almost two-thirds (69.2%) of respondents had good knowledge of modern contraceptive methods, but only 47.3% practised these methods. Women of nuclear family (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.38,0.95), and who work in agricultural sector (aOR = 0.38; 95% CI: 0.22, 0.64) were less likely to have good knowledge on modern contraceptives. Women with primary (aOR = 2.59; 95% CI: 1.43, 4.72), secondary and above education (aOR = 4.41; 95% CI:2.02,9.63), women with good knowledge of modern contraceptives (aOR = 2.73; 95% CI: 1.66, 4.51), who ever visited a health facility for FP counselling (aOR = 4.40; 95% CI: 2.58, 7.50) had higher odds of modern contraceptives practices.

Conclusion

Muslim women had low use of modern contraceptive methods despite having satisfactory knowledge about them. There is a need for more equitable and focused high-quality FP practices. Targeted interventions are needed to increase the knowledge and practices of contraceptives in the Muslim community. The study highlights the need to target FP interventions among socially disadvantaged women, those living in a nuclear family, and those with poor knowledge of modern contraceptives.

Introduction

Family planning (FP) is one of the high-impact interventions that prevent unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, reduce high-risk births, avert maternal and neonatal deaths, and protect women’s and children’s health [1–4]. Despite multiple benefits, many women needing FP methods cannot access the FP services. This unmet need for FP results in approximately 539,000 annual unintended pregnancies in Nepal [5, 6]. These unintended pregnancies can pose serious health risks to mothers and their newborns, including deaths [7]. Maternal morbidity and mortality risks are also high among poor, rural women facing many barriers to accessing FP services in Nepal [5, 8, 9]. One in 200 women dies from pregnancy-or delivery-related causes in their lifetime in Nepal [10].

Nepal made considerable progress in health services access and improved maternal and child health services coverage over the last three decades [11, 12]. However, the FP program has poor performance and has low and stagnant progress in the contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) [13]. The Nepal Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) 2016 [12] revealed that CPR for modern contraceptive methods in Nepal was 43%, with 24% unmet needs. In addition, women from the poorest households, living in remote areas, disadvantaged ethnicities, religious minorities, and those without education had poor knowledge and the lowest practice of contraceptive methods [14].

Nepali Muslims are recognised as one of the most marginalised and disadvantaged communities [15], consisting of 4.4% of the total population [16]. Most of them live in the Terai districts. Muslims are economically, socially, educationally, and politically backward and deprived of various facilities, including health services [15]. In 2011, the poverty incidence for the Muslim population was 20.2%, and the adult literacy rate was 43.5%, compared with 25.2% and 40.43% for the general population, respectively [16]. Muslims ranked at the bottom of the Human Development Index (HDI) (HDI score: 0.41) [17]. In Nepal, Muslims have low access to and practice of family planning with a high unmet need for FP services, including other health services [16, 18]. Muslim women have low CPR (25.4%), high unmet need (37%) for modern contraceptive methods, high fertility and large family size in Nepal [16, 19]. In Nepal, the total fertility rate has increased from 4.6 (2006) to 4.9 (2011) in Muslim populations [16]. Muslim groups had high unintended pregnancies leading to the highest maternal mortality ratio (318 per 100000 live births) in Nepal [20], which suggests the need for quality FP services delivery and utilisation among Muslims. Better use of family planning could reduce many of these mistimed and unplanned pregnancies. At the same time, it could reduce the number of unsafe abortions and the mortality related to childbirth [21].

Several factors have contributed to poor progress in practices of contraceptive methods, including poor access to contraceptive methods, lack of contraceptive methods in health facilities [22], poor uptake due to perceived side effects, poor knowledge of contraceptive methods, opposition from family members, psychological factors, lack of proper counselling services on contraceptive methods and religious and cultural beliefs and value system [18, 23]. In addition, behavioural norms prevailing in Muslim society may affect Muslim women’s access to and utilisation of family planning services [24]. For example, a common concern in Muslim communities is that FP is deemed a Western ideology and a conspiracy to reduce the Muslim population [19]. Previous studies reported that some Muslims believe that using family planning services will result in divine retribution or that the number of children they should have is ‘God’s business,’ and that parents should not try to change God’s will [16, 25].

Evidence showed that knowledge and attitude contributed to modern contraceptive methods [26]. In addition, other socioeconomic and demographic factors were also identified as determinants of contraceptive methods, such as women’s age, education, number and sex of children, occupation, and access to a health facility [3, 18]. However, limited evidence is available on the status of knowledge and practices of modern contraceptive methods and their associated determinants among Muslim women in Nepal.

Therefore, we aimed to assess the existing family planning knowledge and practice among Muslim women and identify the factors influencing access to and uptake of modern family planning services in Mid-western Nepal. The findings of this study could inform policymakers and program managers to design contextual policies and programmatic strategies for universal coverage of contraceptive methods among the Muslim population.

Policy and services delivery context of family planning program in Nepal

The FP program is Nepal’s oldest public health program [19], and services are available at the community level through Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs). Nepal’s health policy 2019 and strategies also emphasised the family planning program and ensuring quality family planning services. Current periodic strategies and plans, such as Nepal Health Sector Strategy (NHSS) 2015–2020 [27], and the Population Perspective Plan (2010–2031) [28], have highlighted family planning as the major component of the Safe Motherhood Initiative in Nepal [29]. The family planning Costed Implementation Plan 2015–2021 has also highlighted the cost and implementation strategies [30]. However, these policies and program approaches are implemented one-size-fits-all [19]. There have not been focused and context-specific implementation strategies to recognise religious and cultural considerations for addressing FP needs of marginalised populations.

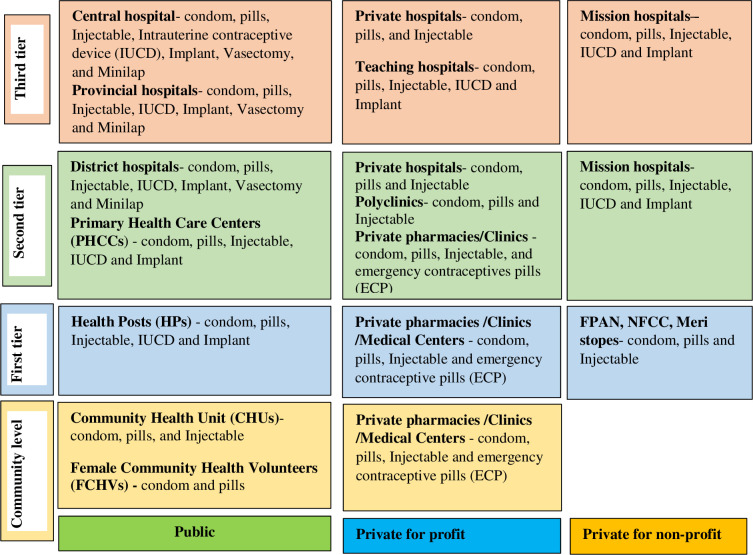

In Nepal, modern contraceptive services provided from different outlets ranging from community to tertiary level (Fig 1). Services outlets include community clinics, health posts, static health clinics, and mobile health camps from public, private, and private non-profit sector health institutions. In addition, several short-term modern contraceptives are available at peripheral facilities. In contrast, long-term modern contraceptives are being provided in health posts (HP), primary health care centers (PHCC) and hospitals [31].

Fig 1. Types and delivery outlets of modern contraceptives in Nepal.

Source: Developed by authors based on information obtained from Nepal’s annual health report 2019 [31].

Methods

Study design and setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was carried out between June and September 2019 in Khajura Rural Municipality of Banke district. The study population was married Muslim women with reproductive ages of 15 to 49 years. We selected Khajura Rural Municipality purposively. More than one in four (26.7%) people in this municipality belong to Muslim backgrounds [32]. Khajura Rural Municipality has 50,961 residents from 10,288 households (Female: 27,457 and 19,397 aged 15 to 49 years) [32]. Four wards (of eight wards) of the municipality were selected randomly for the household survey. A Ward is the lowest administrative unit in Nepal. An estimated 1,750 Muslim married women of reproductive age (MWRA) were living in those selected wards [33].

Sampling and participants selection

This study’s sampling frame was married Muslim women aged 15–49 years. The sampling frame of Muslim MWRA was obtained from the selected ward office. Sample size was calculated using formula N = Z2pq/d2 where [Z = 1.96, p = 0.44 q = 0.56, d = 0.05] and 44% prevalence rate [34]. We determined 379 as the minimal sample size. Considering a non-response rate of 5% [35], a sample of 400 Muslim women were interviewed among 1,750 Muslim MWRA. We selected participants through a systematic random sampling method. The first women were selected randomly, and then every fourth (having a gap of three) women were selected for the interview. If there was more than one MWRA in the family, the youngest women were included in the study. Likewise, the adjoining households were recruited if the participants were unavailable in the selected households.

Study variables

Based on previous studies in Nepal and elsewhere [19, 36, 37], explanatory variables were basic socioeconomic and demographic variables. Demographic variables were respondent’s age (≤18 years,19–29 years and ≥30 years), parity (0 to 2 and ≥3), respondent’s family type (nuclear and joint family) [38]. Socioeconomic variables were respondent’s education (illiterate, primary education, and secondary and above) [39], respondent’s occupation (agriculture, daily wage workers and housewives). Similarly, family monthly income (≤20000 NRs and >20000 NRs (130 Nepalese Rupees = 1 USD, 2022)). Additionally, access to family planning service variable included: ever visited a health facility for family planning counselling (yes/no). Knowledge of modern contraceptive methods was also included as the independent variable for practices of modern contraceptive methods.

Outcome variables

Two outcome variables were included: knowledge on modern contraceptive methods (good and poor knowledge), and practices of modern contraceptive methods (yes or no). Knowledge of modern contraceptive methods was created using ten questions about modern contraceptives. Each question’s response was coded as “1” for “yes” and “0” for “no”. The possible knowledge score ranges between a minimum 0 and maximum 10. Next, the median score of the knowledge was calculated. Using the median as a cut-off-point, we categorised knowledge level into “Good” (> = median score) and “Poor” (<median score) [7, 40].

Women were asked if they had used modern contraceptive methods in the last six months before this survey and coded their responses as ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to assess the practice of modern contraceptive methods.

Data collection tools and techniques

A questionnaire on knowledge and practice of modern contraceptive methods was adopted from the previous studies [19, 34, 41] and a survey [12]. The structured questionnaire was first developed in English, and then translated into Nepali and the local language (Awadhi). The second author YKCS translated the English version of the tool into Nepali and the local language (Awadhi) with the support of a professional translator. It was pretested among 20 women aged 15–49 years in an adjoining ward to refine it. Necessary adjustments were made, including in the flow of question patterns and language style. The local language was used in data collection. A face-to-face interview was conducted in the participant’s households. The interview was carried out in a separate area of the participants’ households to ensure confidentiality. Participation was voluntary, and none approached respondents who refused to be interviewed. Data were collected by local enumerators consisting of three females. The enumerators were the local Muslim community. They were recruited based on their educational background, local language knowledge, and prior data collection experience. The two days of training were provided to the enumerators about the study purpose, methodologies, tools, and techniques before preceding the actual data collection. All the data collection-related field activities were closely supervised and monitored by the second author (YKCS).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The collected data were entered, coded, and cross-checked to ensure consistency. Descriptive analyses were employed and reported as frequencies and proportions. The Chi-square test was conducted to assess the association between independent and outcome variables. Binomial logistic regression was examined to identify the determinants of knowledge and practices of modern contraceptive methods. Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (CIs) were reported. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from this study’s ethical review board of Nepal Health Research Council and the educational and administrative ethical committee, faculty of Nursing and Medical College of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China. Before collecting data, written permission was obtained from the local administrative authority Khajura Rural Municipality of Banke district. Before the interview, enumerators and the second author (YKCS) met Muslim religious leaders, shared the study’s objective, and obtained permission to meet and collect data from their community. Verbal informed consent was obtained from participants before conducting the interview. The respondent’s participation was voluntary, and the respondents had the right to refuse the interview process.

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of respondents accordingly to sociodemographic characteristics, the prevalence of knowledge and the use of modern contraceptive methods. Nearly half (46%) of the respondents were between 19 and 29 years. The mean age of respondents was 29 (±8.74 SD) years. Over three-quarters of respondents (78.5%) had up to 2 living children, and almost half (48%) of respondents had primary level education. Approximately half (49.5%) of respondents were housewives, while 37% of respondent’s husbands were involved in agriculture. Over 6 in 10 respondents had >20000 NRs family monthly income. Almost two-thirds (69.2%) of respondents had good knowledge of modern contraceptive methods, and 47.3% used modern contraceptive methods. Overall, the mean knowledge score of FP was 6.9 (±1.18), with minimum knowledge scores of 3 and maximum scores of 10, and the median knowledge score was 7. Injectable (43.4%) was the most used modern contraceptive, and an implant (3.7%) was the least used. Additionally, over 7 in 10 (71%) visited a health facility for family planning counselling (Table 1).

Table 1. Background characteristics and modern contraceptive methods, knowledge, and practices of Muslim women (N = 400) in Nepal.

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of women | ≤18 Years | 34 | 8.5 |

| 19–29 Years | 184 | 46.0 | |

| ≥30 Years | 182 | 45.5 | |

| Parity | 0 to 2 | 314 | 78.5 |

| 3 or above | 86 | 21.5 | |

| Family types | Nuclear | 145 | 36.3 |

| Joint | 255 | 63.7 | |

| Women’s education | Illiterate | 108 | 27.0 |

| Primary | 192 | 48.0 | |

| Secondary & above | 100 | 25.0 | |

| Women’s occupation | Agriculture | 158 | 39.5 |

| Daily wages worker | 44 | 11.0 | |

| Housewives | 198 | 49.5 | |

| Husband’s occupation | Agriculture | 148 | 37.0 |

| Business and service | 50 | 12.5 | |

| Daily wages worker | 82 | 20.5 | |

| Foreign migrant worker | 120 | 30.0 | |

| Family income (NRs) | ≤20000 | 158 | 39.5 |

| >20000 | 242 | 60.5 | |

| Knowledge of modern contraceptive methods | Poor knowledge | 123 | 30.8 |

| Good knowledge | 277 | 69.2 | |

| Practices of modern contraceptive methods | Yes | 189 | 47.3 |

| No | 211 | 52.7 | |

| Contraceptive practices (n = 189) | Condom | 33 | 17.5 |

| Oral contraceptive | 49 | 25.9 | |

| Injectable | 82 | 43.4 | |

| Implant | 7 | 3.7 | |

| Intrauterine contraceptive Device (IUCD) | 10 | 5.3 | |

| Female sterilisation | 8 | 4.2 | |

| Ever visited a HF for FP counselling | Yes | 284 | 71.0 |

| No | 116 | 29.0 |

Table 2 shows the descriptive findings of knowledge regarding modern contraceptive methods. The majority of respondents (89%) heard about family planning. However, almost half (47.3%) of respondents didn’t know that using both a condom and oral contraceptives is effective. Over 7 in 10 (71%) respondents knew that women who use injectables must get an injection every three months. Almost seven in ten (69%) women knew that using contraceptives prevents unwanted pregnancies. However, over four in ten (44%) women didn’t know about contraceptive pills’ common side effects, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive findings of knowledge related to modern contraceptives among Muslim Women, Banke, Nepal, 2019 (N = 400).

| Variables | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| 1. Have you ever heard about FP? | 356 (89%) | 44 (11.0%) |

| 2. Does female sterilisation avoid pregnancy? | 288 (72%) | 112 (28.0%) |

| 3. Do oral contraceptive pills guarantee 100% protection? | 269 (67.2%) | 131(32.8%) |

| 4. Are women using the birth control injectables to get an injection every three months? | 284 (71.0%) | 116 (29.0%) |

| 5. Do the use of both a condom and oral contraceptives considered to be very effective contraceptives? | 211(52.8%) | 189 (47.2%) |

| 6. Does use of contraceptives prevent unwanted pregnancies? | 276 (69.0%) | 124 (31.0%) |

| 7. Are contraceptive methods appropriate to space childbirth? | 268 (67.0%) | 132 (33.0%) |

| 8. Does condom provide dual protection (Prevents STI/HIV and unplanned pregnancies) | 286 (71.5%) | 114 (28.5%) |

| 9. Do common side effects of contraceptive pills include mood swings and weight gain? | 224 (56%) | 174 (44%) |

| 10. Does health education important for women who want to use contraceptives? | 266 (66.5%) | 134 (33.5%) |

Table 3 depicts the different sociodemographic variables, knowledge, and practice of modern contraceptive methods. Nearly three fourth (72.5%) of respondents from a joint family had good knowledge of modern contraceptive methods. Over half (56.6%) of respondents belonging to the nuclear family practised modern contraceptive methods. Respondents with secondary and above education reported greater (56.0%) use of modern contraceptive methods. More than half (51.6%) of women who had good knowledge of modern contraceptive methods used modern contraceptives. Six in ten (60.3%) respondents who visited a health facility for FP counselling have used modern contraceptive methods (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors associated with knowledge and practices of modern contraceptive methods among Muslim women (N = 400) in Nepal.

| Variables | Frequency (%) | Knowledge modern contraceptive | P value | Practice modern contraceptive | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor (<median) (%) | Good (> = median) (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | ||||

| Women’s age | |||||||

| ≤18 years | 34 (8.5) | 12 (35.3) | 22 (64.7) | 0.805 | 15 (44.1) | 19 (55.9) | 0.580 |

| 19–29 years | 184 (46.0) | 57 (31.0) | 127 (69.0) | 99 (53.8) | 85 (46.2) | ||

| ≥30 years | 182 (45.5) | 54 (29.7) | 128 (70.3) | 96 (52.7) | 86 (47.3) | ||

| Family type | |||||||

| Joint | 255 (63.8) | 70 (27.5) | 185 (72.5) | 0.058 | 147(57.6) | 108(42.4) | 0.006 |

| Nuclear | 145 (36.3) | 53 (36.6) | 92 (63.4) | 63(43.4) | 82(56.6) | ||

| Parity | |||||||

| 0–2 | 314 (78.5) | 97 (30.9) | 217 (69.1) | 0.907 | 164(52.2) | 150(47.8) | 0.836 |

| ≥3 | 86 (21.5) | 26 (30.2) | 60 (69.8) | 46(53.5) | 40(46.5) | ||

| Women’s education | |||||||

| Illiterate | 108 (27.0) | 35 (32.4) | 73 (67.6) | 0.772 | 68(63.0) | 40(37.0) | 0.020 |

| Primary | 192 (48.0) | 60 (31.3) | 132 (68.8) | 98(51.0) | 94(49.0) | ||

| Secondary and above | 100 (25.0) | 28 (28.0) | 72 (72.0) | 44(44.0) | 56(56.0) | ||

| Women’s occupation | |||||||

| Housewives | 198 (49.5) | 48 (24.2) | 150 (75.8) | <0.001 | 103(52.0) | 95(48.0) | 0.444 |

| Agriculture | 158 (39.5) | 68 (43.0) | 90 (57.0) | 80(50.6) | 78(49.4) | ||

| Daily wages worker | 44 (11.0) | 7 (15.9) | 37 (84.1) | 27(61.4) | 17(38.6) | ||

| Husband’s occupation | |||||||

| Agriculture | 148 (37.0) | 53 (35.8) | 95 (64.2) | 0.078 | 79(53.4) | 69(46.6) | 0.123 |

| Business and service | 82 (20.5) | 16 (19.5) | 66 (80.5) | 20(40.0) | 30(60.0) | ||

| Daily wages workers | 50 (12.5) | 15 (30.0) | 35 (70.0) | 40(48.8) | 42(51.2) | ||

| Foreign migrant worker | 120 (30.0) | 39 (32.5) | 81 (67.5) | 71(59.2) | 49(40.8) | ||

| Income (monthly) NRs | |||||||

| ≤20000 | 158 (39.5) | 53 (33.5) | 105 (66.5) | 0.328 | 78(49.4) | 80(50.6) | 0.311 |

| >20000 | 242 (60.5) | 70 (28.9) | 172 (71.1) | 132(54.5) | 110(45.5) | ||

| Knowledge of modern contraceptive methods | |||||||

| Poor knowledge | 76(61.8) | 47(38.2) | 0.013 | ||||

| Good knowledge | 134(48.4) | 143(51.6) | |||||

| Ever visited a HF for FP counselling | |||||||

| No | 85 (73.3) | 31(26.7) | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 125(39.7) | 190(60.3) | |||||

Table 4 illustrates the determinants of knowledge on contraceptive methods. Women who belonged to the nuclear family (aOR = 0.598; 95% CI: 0.38,0.95) had lower odds of knowing modern contraceptive methods than those in the joint family. Women who involve in agricultural sector (aOR = 0.379; 95% CI: 0.22, 0.64) were less likely to be aware of modern contraceptive methods than housewives (Table 4).

Table 4. Determinants of good knowledge on modern contraceptive methods among Nepali Muslim women (N = 400).

| Variables | Knowledge on modern contraceptive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR 95% CI | p | AOR 95% CI | p | |

| Women’s age | ||||

| ≥30 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≤18 years | 0.77 (0.36,1.67) | 0.514 | 0.61 (0.25,1.48) | 0.276 |

| 19–29 years | 0.94 (0.60,1.47) | 0.786 | 0.84 (0.49,1.44) | 0.533 |

| Family type | ||||

| Joint | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Nuclear | 0.66 (0.42, 1.02) | 0.059 | 0.60 (0.38,0.95) | 0.030 |

| Parity | ||||

| 0–2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥3 | 1.03 (0.61,1.73) | 0.907 | 1.11(0.61,2.01) | 0.728 |

| Women’s education | ||||

| Illiterate | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Primary | 1.05 (0.64, 1.75) | 0.836 | 0.86 (0.49,1.54) | 0.620 |

| Secondary and above | 1.23 (0.68,2.23) | 0.490 | 0.77 (0.36, 1.64) | 0.495 |

| Women’s occupation | ||||

| Housewives | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Agriculture | 0.42 (0.27,0.67) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.22, 0.64) | <0.001 |

| Daily wages worker | 1.69 (0.71,4.04) | 0.237 | 1.61 (0.62,4.19) | 0.327 |

| Husband’s occupation | ||||

| Agriculture | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Business and service | 2.30 (1.21,4.37) | 0.011 | 1.56 (0.68,3.59) | 0.295 |

| Daily wages workers | 1.30 (0.652,2.60) | 0.455 | 0.91 (0.42,1.94) | 0.802 |

| Foreign migrant worker | 1.16(0.70,1.93) | 0.570 | 0.81 (0.40,1.62) | 0.554 |

| Income (monthly) in NRs | ||||

| ≤20000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| >20000 | 1.24 (0.81,1.91) | 0.328 | 1.02 (0.56, 1.83) | 0.958 |

Bold Significant at p< 0.05.

Table 5 demonstrates the determinants of practice of modern contraceptive methods. Women with primary (aOR = 2.59; 95% CI: 1.43, 4.72), secondary and above education (aOR = 4.41; 95% CI:2.02,9.63) had significantly higher odds of practices of modern contraceptive methods compared to illiterate women. Women living in a nuclear family (aOR = 2.24; 95% CI:1.40,3.59) had more than two-fold higher odds of modern contraceptive practices than their counterparts. Additionally, the practices of modern contraceptives were significantly higher among women in the business and service sector (aOR = 2.55; 95% CI:1.17,5.56) compared to agriculture. Women having good knowledge of modern contraceptive methods (aOR = 2.73; 95% CI: 1.66, 4.51) and women who ever visited a health facility for FP counselling (aOR = 4.40; 95% CI: 2.58, 7.50) were more likely to practice modern contraceptive methods compared to those who had poor knowledge and those who have not visited a health facility for FP counselling respectively (Table 5).

Table 5. Determinants of good practices of modern contraceptive methods among Nepali Muslim women (N = 400).

| Variables | Practice of modern contraceptive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR 95% CI | p | AOR 95% CI | p | |

| Women’s age | ||||

| ≥30 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≤18 years | 1.41 (0.68, 2.95) | 0.357 | 1.22 (0.50,3.01) | 0.664 |

| 19–29 years | 0.96 (0.64,1.45) | 0.839 | 0.99 (0.58,1.69) | 0.968 |

| Family type | ||||

| Joint | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Nuclear | 1.77 (1.17, 2.67) | 0.006 | 2.24 (1.40,3.59) | 0.001 |

| Parity | ||||

| 0–2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥3 | 0.95 (0.59,1.53) | 0.836 | 1.22 (0.67,2.24) | 0.511 |

| Women’s education | ||||

| Illiterate | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Primary | 1.63 (1.01, 2.64) | 0.047 | 2.59 (1.43, 4.72) | 0.002 |

| Secondary and above | 2.16 (1.24, 3.77) | 0.006 | 4.41(2.02,9.63) | <0.001 |

| Women’s occupation | ||||

| Housewives | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Agriculture | 1.06 (0.70,1.61) | 0.795 | 1.46 (0.84,2.52) | 0.179 |

| Daily wages worker | 0.68 (0.35,1.33) | 0.263 | 0.57 (0.25,1.29) | 0.175 |

| Husband’s occupation | ||||

| Agriculture | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Business and service | 1.72 (0.90, 3.30) | 0.104 | 2.55 (1.17,5.56) | 0.019 |

| Daily wages workers | 1.20(0.70,2.06) | 0.504 | 1.29 (0.58,2.85) | 0.532 |

| Foreign migrant worker | 0.79 (0.49,1.29) | 0.343 | 1.00 (0.49,2.02) | 0.989 |

| Income (monthly) in NRs | ||||

| ≤20000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| >20000 | 0.81 (0.54,1.21) | 0.311 | 0.67(0.36,1.21) | 0.177 |

| Knowledge of modern contraceptive methods | ||||

| Poor knowledge | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Good knowledge | 1.73 (1.12, 2.66) | 0.014 | 2.73 (1.66, 4.51) | <0.001 |

| Ever visited a HF for FP counselling | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 3.49(2.17,5.60) | <0.001 | 4.40 (2.58,7.50) | <0.001 |

Bold Significant at p< 0.05.

Discussion

The current study assessed the knowledge and practice of modern contraceptives among Muslim women. Most Muslim women had relatively good knowledge and poor practice of modern contraceptives. Knowledge of modern contraceptive methods was low among the women working in agriculture and living in nuclear families. The practice of modern contraceptives was poor among women with no education, husbands working in the agriculture sector, women having poor knowledge on modern contraceptive methods, and who have not visited a health facility for family planning counselling.

This study revealed that 69% of women had good knowledge of modern contraceptive methods. Past studies reported mixed results on knowledge of modern contraceptive methods in Nepal. For example, a previous study (2016) reported low (44%) knowledge on modern contraceptive methods among Muslim women in Nepal [34]. Another study showed relatively higher (94.5%) knowledge on modern contraceptive methods in Nepal [35]. About 87% of women knew contraceptive methods in India [42]. Exposure to FP information through mass media message dissemination, community HWs and Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs) in the study area might have helped acquire good knowledge of modern contraceptive methods.

Despite a high proportion of good knowledge on modern contraceptive methods, Muslim women have low practices of modern contraceptive methods in Nepal. Religious beliefs, societal pressure and fear of going against religious values could be a potential driving force of lower practices of modern contraceptive methods [43]. Our study’s finding is consistent with past studies conducted in Bangladesh [44], and India [45]. Injectable was the most practised modern contraceptive method, followed by oral contraceptive pills. Similar to our findings, previous research conducted in the eastern district of Nepal also reported injectables as the most used contraceptives (53.1%), followed by oral contraceptives (24%) [34]. Likewise, another study conducted in the Kapilvastu district in Nepal reported that injectable (51.3%) was the most commonly used contraceptive method, followed by oral contraceptives (25.6%) [19]. Injectables are the most preferred modern contraceptive methods among Muslim women in Nepal. Their popularity could be due to their simplicity, effectiveness for three months and accessibility even in private pharmacies at a low cost [46].

The knowledge of modern contraceptive methods was influenced by several socioeconomic factors such as family type and occupation of women. The current study revealed that women who lived in the nuclear family and were involved in agriculture had poor knowledge of modern contraceptive methods. The women belonging to a nuclear family may have limited exposure to other family members, resulting in less opportunity to obtain information about contraceptive methods. In addition, women involved in agriculture might lack access to information on contraception. The finding of this study is consistent with the study conducted in India [47]. However, previous studies in Nepal have reported no association between the type of family and knowledge of modern contraceptive methods [34, 35].

Several determinants such as education, nuclear family, good knowledge of contraceptive methods and access to counselling services were positively associated with the practices of modern contraceptive methods. Studies from Nepal [18, 34] and other Asian countries [48] have reported increased practices of modern contraceptive methods with increased education [18, 48]. The findings of the current study are consistent with the previous studies conducted in Nepal [34], Bangladesh [44], and India [45]. Illiterate women may have limited access to contraceptives, leading to a lack of awareness about the benefits of contraceptive use. Furthermore, those women may not openly discuss contraceptives with their spouses due to lower autonomy in marital relationships [26, 49]. Previous evidence showed that illiterate Muslim women became unaware of their reproductive rights and were reluctant to visit health facilities for FP services [16].

Similarly, this study identified women living in the nuclear family have good practices of modern contraceptive methods despite having poor knowledge. The women in the nuclear family may be less likely to be influenced by in-laws and other family members for FP decision-making and more freedom to uptake FP services. Likewise, In the nuclear family, a supportive environment for women may have encouraged them to use family planning services despite their lack of knowledge. Future research can explore the contributing factors of low knowledge but good practices among Muslim women from the nuclear family in Nepal.

Past evidence documented that having good knowledge of contraceptive methods may increase the practice of these contraceptives [26]. Our study also showed that women’s knowledge of modern contraceptive methods was related to their practice. Women with good knowledge were more likely to practice modern contraceptive methods than those with poor knowledge. This might be because women with good knowledge may know better about the benefits of contraceptive use. Therefore, it would increase the women’s decision making power for the practice of contraceptives [50].

Moreover, access to FP counselling was another factor affecting contraceptive practices in our study. Women who had ever visited a health facility for FP counselling were more likely to practice modern contraceptive methods than those who had not visited. Women who have ever visited a health facility for FP counselling might be aware of the benefits of contraceptive use. Therefore, they have favourable behaviour toward the practices of contraceptive methods. A similar study conducted from abroad reported consistent findings [51].

Programmatic implications

This study has highlighted some implications for policy and programs. First, the current study revealed a satisfactory level of good knowledge and poor practices of modern contraceptive methods. These women groups require accessible quality contraceptive choices. Some targeted interventions can be adopted and implemented to improve the knowledge and practice of modern contraceptives. Such interventions include Social Behaviour Change Communication (SBCC) initiatives to raise contraceptive awareness, embedding the Muslim values and culture and mobilising health workers (HWs) from their community.

Similarly, raising awareness and developing educational materials in Urdu for Muslim women and working to extend support for smaller family norms, providing counselling and advice about the contraceptive practice from the community and religious leaders. Moreover, this study suggests that the Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) should design targeted program strategies for Muslim women based on a deeper understanding of needs, including religious and cultural recognition.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has some strengths. We have used pretested and well-designed questions and trained interviewers from the local community. The study has also explored the factors influencing the practice of modern contraceptive methods among most unreached groups. However, this study has some limitations: First, it was a survey design that did not provide us with inferences regarding causality. Second, some important covariates, such as distance to a health facility where FP service is available and cost that previous studies found important predictors of contraceptive practices, were not included in this study [52, 53]. Third, this study cannot be generalised to all populations as this study was conducted among Muslim women. Finally, though this study provided a cross-sectional analysis of knowledge and practices, a qualitative study can explore the underlying drivers of gaps in high knowledge and low practices of modern contraceptive methods among Muslim communities in Nepal.

Conclusions

The practice of modern contraceptive methods is relatively low despite having satisfactory knowledge among Muslim women. The poor knowledge and practice of modern contraceptive methods are seen especially among socially disadvantaged groups. Therefore, improving FP practices among Nepali Muslims needs integrated and focused health interventions. Such program interventions include health education and information dissemination, SBCC interventions, and mobilisation of health workers from the Muslim community. In addition, Focusing on SBCC interventions among socially disadvantaged groups and improving access to modern contraceptive methods could improve the practices of FP services among Muslims in Nepal. Moreover, the study suggests that future studies should look into the contributing factors of low knowledge but good practices of modern contraceptive methods among Muslim women from the nuclear family in Nepal.

Supporting information

(SAV)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Khajura Rural Municipality and all the participants who participated in this study.

Disclaimer: Views presented in this article are solely those of the authors, and do not represent views, interest, or funded work of the organisations where authors affiliated.

Abbreviations

- FP

Family Planning

- FPAN

Family Planning Association of Nepal

- NFCC

Nepal Fertility Care Center

- IUCD

Intrauterine Contraceptive Device

- SBCC

Social Behavior Change Communication

- HW

Health Workers

- FCHV

Female Community Health Volunteer

- NHSS

Nepal Health Sector Strategy

- MOHP

Ministry of Health and Population

- PHCC

Primary Health Care Center

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Ganatra B, Faundes A. Role of birth spacing, family planning services, safe abortion services and post-abortion care in reducing maternal mortality. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36: 145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chola L, McGee S, Tugendhaft A, Buchmann E, Hofman K. Scaling up family planning to reduce maternal and child mortality: The potential costs and benefits of modern contraceptive use in South Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10: 1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdi B, Okal J, Serour G, Temmerman M. “children are a blessing from God”- A qualitative study exploring the socio-cultural factors influencing contraceptive use in two Muslim communities in Kenya. Reprod Health. 2020;17: 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-0898-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mustafa G, Azmat SK, Hameed W, Ali S, Ishaque M, Hussain W, et al. Family Planning Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Among Married Men and Women in Rural Areas of Pakistan. Internatoinal J Reprod Med. 2015;2015: 8. doi: 10.1155/2015/190520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundaram A, Hussain R, Sathar Z, Hussain S, Pliskin E, Weissman E. Adding It Up: Costs and Benefits of Meeting the Contraceptive and Maternal And Newborn Health Needs of Women in Pakistan. Guttmacher Inst. 2019. Available: 10.1363/2019.30703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adhikari R, Soonthorndhada K, Prasartkul P. Correlates of unintended pregnancy among currently pregnant married women in Nepal. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9: 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekele D, Surur F, Nigatu B, Teklu A, Getinet T, Kassa M, et al. Knowledge and attitude towards family planning among women of reproductive age in emerging regions of ethiopia. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13: 1463–1474. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S277896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pradhan Ajit, Bal Krishna Suvedi Sarah Banett, Sharad Kumar Sharma Mahesh Puri, Paudel Pradeep, et al. 2010. Nepal Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study 2008/2009, Family Health Division Department of Health Services Ministry of Health and Population Government of Nepal Kathmandu, Nepal. 2010. Available: http://nnfsp.gov.np/PublicationFiles/aaef7977-9196-44d5-b173-14bb1cce4683.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandari A, Gordon M, Shakya G. Reducing maternal mortality in Nepal. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;118: 26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Governement of Nepal. Family Planning in Nepal: Saving Lives and Improving Health. Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu. 2015. Available: https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/826_FamilyPlanningFINAL.pdf

- 11.Khatri RB, Durham J, Assefa Y. Utilisation of quality antenatal, delivery and postnatal care services in Nepal: An analysis of Service Provision Assessment. Global Health. 2021;17: 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00752-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) [Nepal] New ERA and ICF International Inc. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016, Kathmandu Nepal:Ministry of Health and Population, New ERA, and ICF International, Calverton, Maryland: 2017.

- 13.Mehata S, Paudel YR, Dhungel A, Paudel M, Thapa J, Karki DK. Spousal Separation and Use of and Unmet Need for Contraception in Nepal: Results Based on a 2016 Survey. Sci World J. 2020;2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/8978041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehata S, Paudel YR, Mehta R, Dariang M, Poudel P, Barnett S. Unmet need for family planning in nepal during the first two years postpartum. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/649567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhusal CK, Bhattarai S. Factors Affecting Unmet Need of Family Planning Among Married Tharu Women of Dang District, Nepal. Int J Reprod Med. 2018;2018: 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2018/9312687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arjyal A, Joshi D, Maharjan U, Regmi S, Baral SC, Marston C, et al. Access to family planning services by Muslim communities in Nepal–barriers and evidence gaps. 2016. Available: https://www.herdint.com/publications/9 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhungel S. Provincial Comparison of Development Status in Nepal: An Analysis of Human Development Trend for 1996 to 2026. J Manag Dev Stud. 2018;28: 53–68. doi: 10.3126/jmds.v28i0.24958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehata S, Paudel YR, Dotel BR, Singh DR, Poudel P, Barnett S. Inequalities in the use of family planning in rural Nepal. Biomed Res Int. 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/636439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sapkota D, Adhikari SR, Bajracharya T, Sapkota VP. Designing Evidence-Based Family Planning Programs for the Marginalized Community: An Example of Muslim Community in Nepal. Front Public Heal. 2016;4: 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suvedi B, Krishna A, Pradhan S, Barnett M, Puri SR, Chitrakar P, et al. Nepal Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study, 2008/09. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tilahun T, Coene G, Luchters S, Kassahun W, Leye E, Temmerman M, et al. Family Planning Knowledge, Attitude and Practice among Married Couples in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2013;8: 1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jabeen S, Rathor A, Riaz M, Zakar R, Fischer F. Demand- and supply-side factors associated with the use of contraceptive methods in Pakistan: a comparative study of demographic and health surveys, 1990–2018. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20: 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-01112-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alomair N, Alageel S, Davies N, Bailey J V. Factors influencing sexual and reproductive health of Muslim women: A systematic review. Reprod Health. 2020;17: 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-0888-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamid S, Stephenson R. Provider and health facility influences on contraceptive adoption in urban Pakistan. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32: 71–78. doi: 10.1363/3207106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishtar NA, Sami N, Alim S, Pradhan N, Hasnain FU. Determinants of contraceptives use amongst youth: an exploratory study with family planning service providers in Karachi Pakistan. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5: 1–8. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n3p1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semachew Kasa A, Tarekegn M, Embiale N. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards family planning among reproductive age women in a resource limited settings of Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3689-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Governement of Nepal. Nepal Health Sector Strategy.Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu. 2015. Available: https://nepal.unfpa.org/en/publications/nepal-health-sector-strategy-2015-2020

- 28.Ministry of Health and Population. Population Perspective Plan 2010–2031. 2010. Available: https://nepalindata.com/resource/population-perspective-plan-2010-2031-/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrestha DR, Shrestha A, Ghimire J. Emerging challenges in family planning programme in Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2012;10: 108–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Governement of Nepal, Ministry of Helath and Population, Department of Health Services FHD. National Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan 2012–2015. 2015. Available: https://nepal.unfpa.org/en/publications/national-family-planning-costed-implementation-plan-2015-2020

- 31.Annual Report 2075/76 (2019/20): Departement of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Population. 2019. Available: https://dohs.gov.np/

- 32.CBS. National Population and Housing Census 2011; National Planning Commission Secretariates, Central Bureau of Statistics. 2012. Available: http://cbs.gov.np/?p=2017 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Governement of Nepal. Health Management Information System (HMIS), Ministry of Health and Population. 2020. Available: http://hmis.gov.np/hmis/dhis-web-reporting/displayViewDocumentForm.action

- 34.Sigdel A, Alam M, Bista A, Sapkota H, Ghimire BS. Knowledge and utilization of family planning measures in a Muslim community of Sunsari district, Nepal. Imp J Interdiscip Res. 2016;2: 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhakal U, Shrestha RB, Bohara SK, Neupane S. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Family Planning among Married Muslim Women of Reproductive Age. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2020;18: 238–242. doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v18i2.2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhatta DN, Haque A. Health problems, complex life, and consanguinity among ethnic minority Muslim women in Nepal. Ethn Heal. 2015;20: 633–649. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.980779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma D, Pokharel HP, Budhathoki SS, Yadav BK, Pokharel RK. Antenatal Health Care Service Utilization in Slum Areas of Pokhara Sub-Metropolitan City, Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2016;14: 39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madjdian DS, Bras HAJ. Family, Gender, and Women’s Nutritional Status: A Comparison Between Two Himalayan Communities in Nepal. Econ Hist Dev Reg. 2016;31: 198–223. doi: 10.1080/20780389.2015.1114416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thakuri DS, Thapa RK, Singh S, Khanal GN, Khatri RB. A harmful religio-cultural practice (Chhaupadi) during menstruation among adolescent girls in Nepal: Prevalence and policies for eradication. PLoS One. 2021;16: 1–22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kassahun CW, Mekonen AG. Knowledge, attitude, practices and their associated factors towards diabetes mellitus among non diabetes community members of Bale Zone administrative towns, South East Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12: 1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lincoln J, Mohammadnezhad M, Khan S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Family Planning Among Women of Reproductive Age in Suva, Fiji in 2017. J Women’s Heal Care. 2018;07: 3–8. doi: 10.4172/2167-0420.1000431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shumayla S, Kapoor S. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of family planning among Muslim women of North India. Int J Med Sci Public Heal. 2017;6: 1. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2017.1266308122016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boonstra H. Islam, women and family planning: A primer. Guttmacher Rep. 2001;December: 4–7. Available: https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2001/12/islam-women-and-family-planning-primer [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamal SMM. Socioeconomic factors associated with contraceptive use and method choice in urban slums of Bangladesh. Asia-Pacific J Public Heal. 2015;27: NP2661–NP2676. doi: 10.1177/1010539511421194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma Suresh. Are Muslim women behind in their knowledge and use of contraception in India? J Public Heal Epidemiol. 2011;3: 632–641. doi: 10.5897/jphe11.153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karkee R, Adhikary S. A Cross-Sectional Survey of Contraceptive Use and Birth Spacing Among Multiparous Women in Eastern. Asia-Pacific J Public Heal. 2020. doi: 10.1177/1010539520912117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sindhu BM, Angadi MM. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice about Family Planning Methods among Reproductive Age Group Women in a Tertiary Care Institute. Int J Sci Study. 2016;4: 133–136. doi: 10.17354/ijss/2016/269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Najafi-Sharjabad F, Zainiyah Syed Yahya S, Abdul Rahman H, Hanafiah Juni M, Abdul Manaf R. Barriers of modern contraceptive practices among Asian women: a mini literature review. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5: 181–192. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n5p181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senarath U, Nalika Sepali Gunawardena. Women’s autonomy in decision making for health care in South Asia. Asia-Pacific J Public Heal. 2009;21: 137–143. doi: 10.1177/1010539509331590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dadi D, Bogale D, Minda Z, Megersa S. Decision-Making Power of Married Women on Family Planning Use and Associated Factors in Dinsho Woreda, South East Ethiopia. Open Access J Contracept. 2020;Volume 11: 15–23. doi: 10.2147/OAJC.S225331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korra A 2002. Planning and Reasons for Nonuse among Women with Unmet Need for Family Planning in Ethiopia. Calverton, Maryl USA: ORC Macro. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FA40/ETFA40.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonie A, Wudneh A, Nigatu D, Dendir Z. Determinants of family planning use among married women in bale eco-region, Southeast Ethiopia: A community based study. BMC Womens Health. 2018. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0539-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eliason S, Awoonor-Williams JK, Eliason C, Novignon J, Nonvignon J, Aikins M. Determinants of modern family planning use among women of reproductive age in the Nkwanta district of Ghana: A case-control study. Reprod Health. 2014;11: 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]