Abstract

Interleukin-18 (IL-18) is a proinflammatory cytokine that plays an important role in natural killer cell activation and the T helper 1 (Th1) cell response, particularly in collaboration with IL-12. Since Th1 cells play a pivotal role in the host defense against infection with intracellular microbes, such as Leishmania major, we investigated whether IL-18 is critically involved in protection against L. major infection by activation of Th1 cells. We administered IL-12 and/or IL-18 daily to L. major-susceptible BALB/c mice. Neither IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) nor IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) induced wound healing, while daily injection of IL-12 and IL-18 during the first week after infection strongly protected the mice from footpad swelling by induction and activation of Th1 cells. Furthermore, these mice acquired protective immunity. We also investigated a protective role of endogenous IL-18 by using anti-IL-18 antibody-treated C3H/HeN mice (an L. major-resistant strain) or IL-18 deficient (IL-18−/−) mice with a resistant background (C57BL/6). We found that in the absence of endogenous IL-18, these mice showed prolonged footpad swelling as well as diminished nitric oxide production. However, daily injection of IL-18 into IL-18−/− mice corrected their deficiencies, suggesting that these mice have Th1 cells that produce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in response to IL-18. Indeed, these mice had normal levels of Th1 cells. Thus, IL-18 is not responsible for inducing Th1 cells but participates in host resistance by its action in stimulating Th1 cells to produce IFN-γ. Our results also indicate the high potentiality of IL-18 as a useful reagent for treatment as well as prevention against reinfection.

The resistance and susceptibility of inbred strains of mice to infection with Leishmania major are intimately associated with their capacity to produce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4), respectively (2, 3, 14, 15, 26, 36, 38, 39, 41). Healing of lesions caused by L. major infection requires induction and expansion of T helper 1 (Th1) cells, which produce IFN-γ, a crucial activator of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (5, 20, 23, 53). In contrast, IL-4, produced by T helper 2 (Th2) cells, promotes disease, because IL-4 inhibits the expression of iNOS (25). The importance of the nitric oxide (NO)-dependent killing of intracellular parasites was demonstrated (7, 9, 23, 24, 44) and was further substantiated by the result showing that iNOS-deficient mice with a resistant background developed nonhealing cutaneous lesions (7, 55).

IL-12 is a major determinant of transformation of naive T cells into IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells in vitro (19, 32, 40, 48). The essential role of IL-12 in Th1 cell development in vivo has been well established by using mice infected with L. major (17, 35, 52). IL-12-deficient mice with a resistant background lack the Th1 responses (27) and suffer from progressive disease (29). In complementary studies, injection of high doses (e.g., 200 ng) of IL-12 into nonhealing mice such as BALB/c mice could induce Th1 cells that produce IFN-γ and allow the resolution of lesions (16, 45), indicating that IL-12 is a powerful factor that modulates host immunity.

We and others have been interested in the elucidation of the mechanism by which IFN-γ production is synergistically induced by the action of IL-12 and IL-18 in vitro and in vivo (22, 28, 33, 37, 56–59). IL-18, a product of activated macrophages and Kupffer cells, is a potent pleiotropic cytokine (8, 10, 34). IL-18 induces IFN-γ production by lymphocytes, such as T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, particularly in a synergistic manner with IL-12 (22, 28, 33, 51, 57–60). IL-18 augments NK cell activity through the activation of constitutively expressed IL-18 receptor (IL-18R) on NK cells (21). In addition, IL-18 up-regulates Fas ligand-mediated cytotoxic activity of cloned Th1 cells and NK cells (6, 49). IL-18R, composed of IL-1R-related protein (IL-18Rα) (47) and accessory protein-like IL-18Rβ (4), belongs to the IL-1R family (8). IL-18Rα is the ligand-binding subunit of IL-18R (47), and IL-18Rβ is a signaling molecule (4).

Recently, we and others reported that stimulation of naive T cells with IL-12 and antigen can induce Th1 cells that express IL-18R (56, 59). Furthermore, we and other investigators reported that IL-18R is not expressed on Th2 cells, and thus IL-18 stimulates only Th1 cells to produce IFN-γ (22, 37, 56, 59). Since Th1 cells play a critical role in protection against L. major infection, we regarded it important to determine whether IL-18 plays an important role in host defense by activation of Th1 cells in vivo. Thus, we first tested the healing-inducing activity of daily injection of IL-18 with or without IL-12 in L. major-susceptible BALB/c mice. We then investigated involvement of endogenous IL-18 in the host defense of L. major-resistant strains, such as C3H/HeN and C57BL/6 mice, by using anti-IL-18 antibody (Ab) treatment or IL-18-deficient (IL-18−/−) C57BL/6 mice. Here we suggest that administration of IL-12 and IL-18 may be useful for the treatment of L. major-infected BALB/c mice and for prevention of reinfection. We also suggest a beneficial role of endogenous IL-18 in the host defense.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Virus-free BALB/c, C57BL/6, and C3H/HeN mice, 8 to 12 week of age, were obtained from Shizuoka Laboratory Animal Center (Shizuoka, Japan). The IL-18−/− mice were established in our laboratory and maintained in the animal facilities at Hyogo College of Medicine (46). IL-18−/− mice (129SvJ × C57BL/6) were backcrossed for eight generations onto C57BL/6 mice. Homozygous BALB/c background IFN-γ-deficient (IFN-γ−/−) mice were established and maintained at the Laboratory Animal Research Center, Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo.

Cytokines and antibodies.

Recombinant mouse IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-18 were kindly provided by Hayashibara Biochemical Laboratories Inc. (Okayama, Japan). Recombinant mouse IL-4 was obtained and purified from products of a recombinant baculovirus (Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus IL-4) prepared in our laboratory. Rabbit neutralizing anti-IL-18 immunoglobulin G Ab and control IgG Ab were partially purified using a protein G-Sepharose column in our laboratory. This anti-IL-18 Ab could completely neutralize 50 ng of IL-18 per ml at a concentration of 100 μg/ml in vitro. The administration of 200 μg of anti-IL-18 Ab just before lipopolysaccharide challenge completely inhibited lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in mice (50).

L. major infection.

L. major (WHO strain MHOM/SU/73-5-ASKH) was maintained in vivo and grown in vitro. Briefly, the parasites were propagated in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 20% fetal calf serum. Promastigotes were harvested from stationary-phase cultures by centrifugation and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Parasites were passaged at intervals in BALB/c mice to ensure that virulence was maintained. For infection, mice were inoculated by subcutaneous injection of 5 × 106 stationary-phase promastigotes into the hind footpad. The footpad lesions were measured weekly with a dial gauge caliper and compared to the thickness of uninfected footpad. Parasite burdens in the popliteal lymph node draining the site of infection were determined as described previously (43).

In vivo treatment of mice with cytokine or antibody.

BALB/c wild-type (IFN-γ+/+) or BALB/c background IFN-γ−/− mice infected with promastigotes were daily injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with PBS, IL-12 (10 ng/mouse), and/or IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) for the first 7 days after infection. C57BL/6 wild-type (IL-18+/+) or C57BL/6 background IL-18−/− mice infected with promastigotes were daily injected i.p. with PBS or IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) for the first 14 days after infection. C3H/HeN mice infected with promastigotes were intravenously administered control IgG or anti-IL-18 Ab (200 μg/mouse) twice a week for 5 weeks after infection.

Generation and measurement of lymphokines from lymph node culture.

Popliteal lymph nodes cells from mice infected with L. major were cultured with soluble leishmania antigen (SLA) obtained from freeze-thawed promastigotes (equivalent to 4 × 106 promastigotes/ml) or concanavalin A (ConA) (5 μg/ml) in 96-well plates for 48 h at 2 × 105/0.2 ml/well in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2-mercaptoethanol (50 μM), l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Their supernatants were measured for IFN-γ or IL-4 contents by use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or CT.4S, an IL-4-dependent cell line, respectively.

Measurement of NO2−-NO3−.

Levels of nitrite and nitrate (NO2−-NO3−) in the sera were measured with an NO2/NO3 Assay Kit-F (Fluometric) (DOJIN Chemical Laboratory Institute, Kumamoto, Japan). Serum samples were centrifuged (7,500 rpm, 4°C, 1 h) with a Centricon 10 instrument (Amicon Division, W.R. Grace & Co., Beverly, Mass.) to deplete hemoglobin before assay.

In vivo induction of IL-18Rα, IFN-γ, and NO2−-NO3−.

BALB/c mice were daily injected i.p. with IL-12 (10 to 1,000 ng/mouse) for 4 days. Spleen cells were prepared at 5 days after injection, and splenic CD4+ T cells purified with MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Glandbach, Germany) were used for the preparation of mRNAs. These mRNAs were then examined for expression of IL-18Rα mRNA by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). For induction of IFN-γ and NO2−-NO3− in the sera, BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) and various amounts of IL-18 (0 to 5,000 ng/mouse) for 4 days. Sera were taken 6 h after the final injection and analyzed for the production of IFN-γ and NO2−-NO3−.

Analysis of expression of IL-18Rα mRNA.

Cytoplasmic RNA was prepared using the guanidinium method. IL-18Rα mRNA expression was detected by RT-PCR. Primer sequences were as follows: IL-18Rα, CGTGACAAGCAGAGATGTTG (sense) and ATGTTGTCGTCTCCTTCCTG (antisense); β-actin, GATGACGATATCGCTGCGCTG (sense) and GTACGACCAGAGGCATACAGG (antisense). cDNAs were amplified for 35 cycles, each consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s (IL-18Rα) or of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min (β-actin) and then further extension at 72°C for 7 min. At the end of 35 cycles, samples were stored at 4°C until they were analyzed. After amplification, PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in 1.4% agarose gels and visualized by UV light illumination.

RESULTS

Administration of the combination of IL-12 and IL-18 protects BALB/c mice from leishmaniasis.

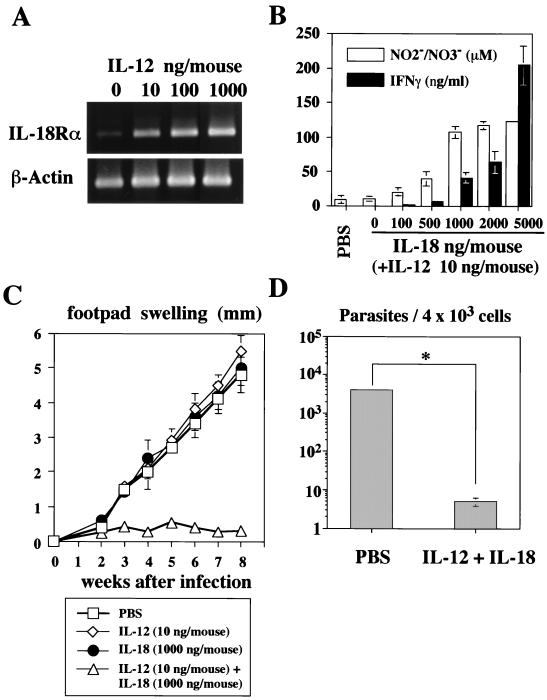

We first examined the capacity of IL-12 to induce IL-18Rα expression in vivo. For this purpose, we daily injected BALB/c mice i.p. with IL-12 (10 to 1,000 ng/mouse) for 4 days. As shown in Fig. 1A, even a low dose of IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) could induce IL-18Rα mRNA in CD4+ T cells. Although neither IL-12 (10 to 1,000 ng/mouse) nor IL-18 (100 to 5,000 ng/mouse) induced increases in serum IFN-γ and NO2−-NO3− levels, their combination caused striking increases in levels of IFN-γ and NO2−-NO3− in serum in a dose-dependent manner (data not shown). Since 10 ng of IL-12 induced a substantial increase in IL-18Rα mRNA in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1A), we used this dose for coinjection. As shown in Fig. 1B, IL-18 dose-dependently induced increases in serum IFN-γ and NO2−-NO3− levels. The maximal serum NO2−-NO3− level was seen in the mice administered 10 ng of IL-12 and 1,000 ng of IL-18. Therefore, we used 10 ng of IL-12 and 1,000 ng of IL-18 in the following experiments.

FIG. 1.

Effect of IL-12 and/or IL-18 administration on L. major-infected BALB/c mice. (A) BALB/c mice (five per group) were daily injected i.p. with PBS or IL-12 (10 to 1,000 ng/mouse) for 4 days. CD4+ T cells purified from these mice at the first day after the last injection were examined for their expression of IL-18Rα mRNA by RT-PCR. (B) BALB/c mice (five per group) were daily injected i.p. with PBS, IL-12 (10 ng/mouse), or a combination of IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) and various amounts of IL-18 (100 to 5,000 ng/mouse) for 4 days. Sera were taken 6 h after the final injection and analyzed for their IFN-γ and NO2−-NO3− contents by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results are means ± standard deviations. (C) BALB/c mice were subcutaneously inoculated with stationary-phase promastigotes. Mice (five per group) were daily injected i.p. with PBS or IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) and/or IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) during the first 7 days after infection. Weekly footpad measurements represent the average foot pad swelling ± one standard deviation. (D) At 8 weeks after infection, parasite burdens in 4 × 103 cells of the popliteal lymph node draining the site of infection were determined. ∗, P < 0.001 compared with infected mice treated with PBS.

We next examined whether administration of IL-12 and IL-18 into BALB/c mice induces wound healing in an IFN-γ-dependent manner. BALB/c mice infected with L. major developed progressive disease, as assessed by footpad swelling (Fig. 1C). Administration of 10 ng of IL-12 or 1,000 ng of IL-18 for the first week of infection did not inhibit this footpad swelling. However, administration of a mixture of IL-12 and IL-18 strongly protected the mice from footpad swelling (Fig. 1C). We also examined the parasite burden at 8 weeks after infection. Consistent with a previous report (14), the level of footpad swelling paralleled well the degree of parasite burden (Fig. 1C and D). Thus, IL-12 and IL-18 inhibited footpad swelling by significant killing (P < 0.001) of parasites in the macrophages.

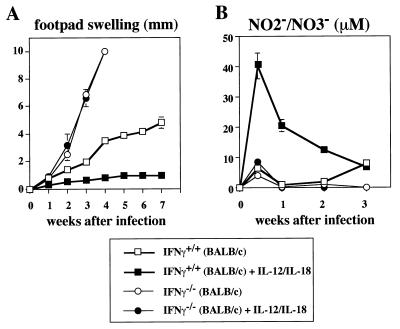

Administration of the combination of IL-12 and IL-18 does not protect IFN-γ−/− BALB/c mice from leishmaniasis.

To examine whether IL-12 and IL-18 cure BALB/c mice by induction of IFN-γ that kills L. major in an NO-dependent manner, we daily administered a mixture of IL-12 and IL-18 to IFN-γ+/+ and IFN-γ−/− BALB/c mice during the first week after L. major infection. Infected IFN-γ+/+ mice manifested footpad swelling (Fig. 2A). Again, although neither IL-12 nor IL-18 inhibited this footpad swelling (data not shown), its combination strongly did (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, this treatment induced a marked increase in the serum NO2−-NO3− level in IFN-γ+/+ mice (Fig. 2B), while treatment with IL-12 or IL-18 alone failed to do so (data not shown). We simultaneously treated L. major-infected IFN-γ−/− mice with IL-12 and IL-18. Infected IFN-γ−/− mice showed striking footpad swelling (Fig. 2A). Injection of IL-12 and IL-18 did not affect this footpad swelling (Fig. 2A), suggesting that IL-12 and IL-18 killed intracellular parasites via the action of IFN-γ. Moreover, this treatment failed to induce NO production in IFN-γ−/− mice (Fig. 2B). These results taken together indicate that IL-12 and IL-18 induced wound healing by induction and activation of Th1 cells that produce IFN-γ, leading to NO-dependent elimination of parasites.

FIG. 2.

Effect of IL-12 and IL-18 administration on L. major-infected IFN-γ−/− BALB/c mice. IFN-γ+/+ (BALB/c) and IFN-γ−/− (BALB/c) mice were subcutaneously inoculated with stationary-phase promastigotes. Mice (five per group) were then daily injected i.p. with PBS or with IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) and IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) for the first 7 days after infection. (A) Weekly footpad measurements represent the average foot pad swelling ± one standard deviation. (B) Sera were taken at days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 21 after infection and analyzed for concentrations of NO2−-NO3−. Results are means ± standard deviations.

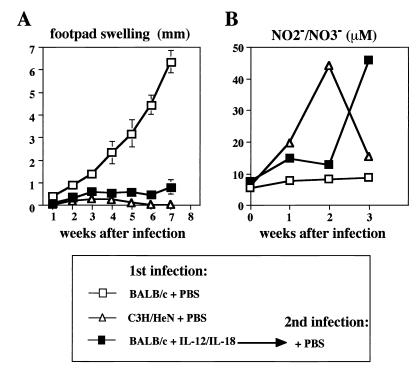

BALB/c mice that recover from L. major infection due to treatment with IL-12 and IL-18 acquire protective immunity.

Next, we examined whether treatment of L. major-infected mice with IL-12 and IL-18 can immunize them against reinfection. Thus, BALB/c mice that recovered from L. major infection after treatment with IL-12 and IL-18 were reinfected with 5 × 106 stationary-phase promastigotes at 14 weeks after the first infection. We simultaneously compared the capacities of immunized BALB/c mice and L. major-resistant C3H/HeN mice to produce NO in response to infection. As shown in Fig. 3A, PBS-treated BALB/c mice manifested footpad swelling after infection with L. major, while immunized BALB/c mice were highly resistant. Importantly, these mice, like L. major-resistant C3H/HeN mice, had increased serum NO2−-NO3− levels after reinfection (Fig. 3B). These results taken together strongly indicate that treatment with IL-12 and IL-18 not only cured primary infection but also provided protective immunity against reinfection.

FIG. 3.

Effect of IL-12 and IL-18 on disease course after secondary L. major infection in BALB/c mice. BALB/c mice (five per group) and C3H/HeN mice (five per group) were subcutaneously inoculated with stationary-phase promastigotes. BALB/c mice (five per group), which had received subcutaneous injections into their left hind footpads followed by daily treatment with IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) and IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) (n = 5) for 7 days, were inoculated with promastigotes into their right hind footpads at 14 weeks after the first infection. (A) Weekly footpad measurements represent the average foot pad swelling ± one standard deviation. (B) Sera were taken at days 0, 7, 14, and 21 after infection and analyzed for their NO2−-NO3− concentrations. Results are means ± standard deviations.

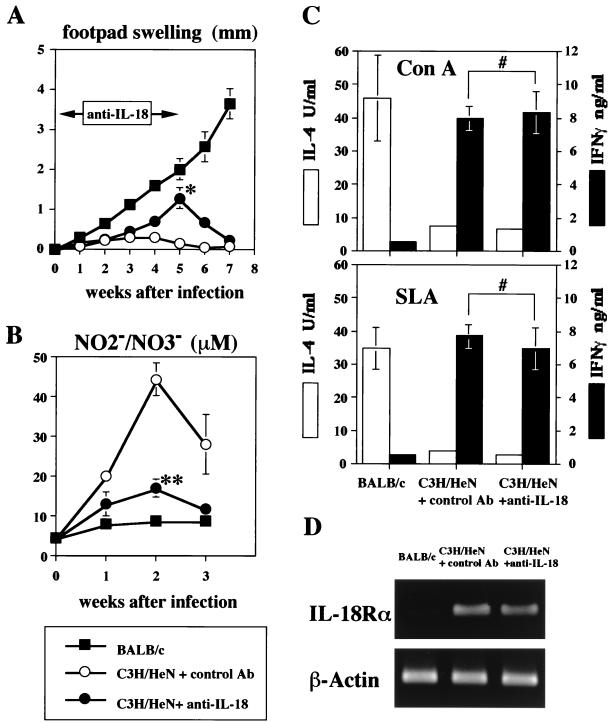

Anti-IL-18 Ab exacerbates L. major infection in C3H/HeN mice.

Next, to address the role of endogenous IL-18 in the host defense of C3H/HeN mice, we injected anti-IL-18 Ab (200 μg/mouse) twice a week immediately after infection with L. major. As shown in Fig. 4A, anti-IL-18 Ab treatment significantly reduced the host resistance to L. major infection (5 weeks after infection; P < 0.01). However, this effect was not persistent, and once the Ab treatment was stopped, these mice recovered from L. major infection.

FIG. 4.

Effect of endogenous IL-18 on protective immunity against L. major. C3H/HeN mice (n = 16) and BALB/c mice (n = 8) were subcutaneously inoculated with stationary-phase promastigotes. C3H/HeN mice were divided in two groups; one (n = 8) was administered with anti-IL-18 (0.2 mg/mouse) intravenously twice a week either for the first 3 weeks (n = 4; for preparation of lymph node cells) or for the first 5 weeks (n = 4; for the measurement of footpad swelling and NO2−-NO3− concentration) after infection, and the other (n = 8) was administered with control antibody (0.2 mg/mouse) for the first 3 weeks (n = 4) or 5 weeks (n = 4). (A) Weekly footpad measurements represent the average foot pad swelling ± one standard deviation. (B) Sera were taken at days 0, 7, 14, and 21 after infection and analyzed for their concentrations of NO2−-NO3−. (C) Draining popliteal lymph nodes from each group of mice (four per group) were harvested at 3 weeks after infection. Cell suspensions (2 × 105/0.2 ml/well) were cultured with ConA (5 μg/ml) or SLA (equivalent to 4 × 106 promastigotes/ml) for 48 h. Culture supernatants were harvested and tested for production of IL-4 and IFN-γ. Results are means ± standard deviations. (D) Draining popliteal lymph nodes (four per group) were harvested at 3 weeks after infection, and mRNAs were extracted. Expression of IL-18Rα and β-actin mRNAs was examined by RT-PCR. ∗, P < 0.01 compared with L. major-infected C3H/HeN mice administered control antibody; ∗∗, P < 0.001 compared with L. major-infected C3H/HeN mice administered control antibody; #, not significant compared with L. major-infected C3H/HeN mice administered control antibody.

To show that this prolonged footpad swelling seen with C3H/HeN mice treated with anti-IL-18 Ab was associated with a decrease in NO production, we simultaneously measured the serum NO2−-NO3− level. As expected, the serum NO2−-NO3− level in C3H/HeN treated with anti-IL-18 Ab was 2.6-fold lower than that in control C3H/HeN mice (Fig. 4B). This effect was significant (2 weeks after infection; P < 0.01). We also measured the capacity of popliteal lymph node cells to produce IFN-γ upon stimulation with SLA or ConA in vitro. As shown in Fig. 4C, lymphocytes from L. major-infected C3H/HeN mice with or without anti-IL-18 Ab treatment showed the capacity to strongly produce IFN-γ upon stimulation, while those from BALB/c mice produced little IFN-γ (Fig. 4C). Thus, anti-IL-18 Ab treatment did not inhibit generation of Th1 cells in L. major-infected C3H/HeN mice. Furthermore, lymphocytes from the L. major-infected C3H/HeN mice with or without anti-IL-18 Ab treatment expressed IL-18Rα mRNA equally, while those from BALB/c mice did not (Fig. 4D), further substantiating previous reports that IL-18Rα is preferentially expressed on Th1 cells (56, 59).

Increased footpad swelling in IL-18−/− mice.

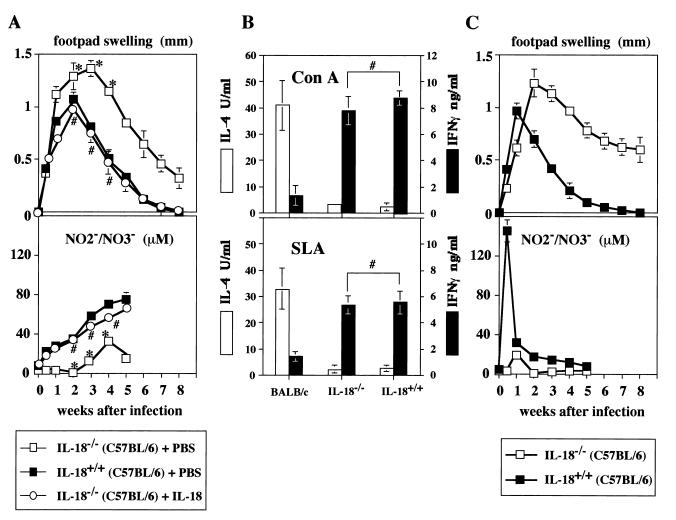

To further understand the protective role of endogenous IL-18, we examined IL-18−/− mice (46) with a resistant background. Compared to IL-18+/+ C57BL/6 mice, IL-18−/− C57BL/6 mice had sustained footpad swelling (Fig. 5A, upper panel). They required 15 weeks to achieve complete lesion resolution (data not shown). Consistent with this long-lasting footpad swelling, the serum NO2−-NO3− level in IL-18−/− mice was significantly lower (P < 0.01) than that in IL-18+/+ mice (Fig. 5A, lower panel). These results suggested that endogenous IL-18 may be required for shortening the duration of wound healing by increasing NO production. Indeed, administration of IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) to IL-18−/− mice not only shortened this duration but also increased NO production (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Disease course after primary and secondary L. major infection in IL-18−/− mice. BALB/c mice (n = 4), IL-18+/+ (C57BL/6) mice (n = 8), and IL-18−/− (C57BL/6) mice (n = 12) were subcutaneously inoculated with stationary-phase promastigotes into their left hind footpads. IL-18−/− (C57BL/6) mice were divided in two groups and then daily injected i.p. with PBS (n = 8) or IL-18 (n = 4; 1,000 ng/mouse) for the first 2 weeks after infection (A). IL-18+/+ (C57BL/6) mice (n = 4) or IL-18−/− (C57BL/6) mice (n = 4) mice that received subcutaneous inoculation into their left hind footpads 18 weeks before and showed no footpad swelling at the time of reinfection were reinoculated with promastigotes into their right hind footpads (C). (A) Weekly footpad measurements (four per group) represent the average foot pad swelling ± one standard deviation. Sera (four per group) were taken at days 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 after infection and analyzed for the production of NO2−-NO3−. (B) Draining popliteal lymph nodes from each group of mice (four per group) were harvested at 3 weeks after infection, and cell suspensions (2 × 105/0.2 ml/well) were cultured with ConA (5 μg/ml) or SLA (equivalent to 4 × 106 promastigotes/ml) for 48 h. Culture supernatants were harvested and tested for production of IL-4 and IFN-γ. Results are means ± standard deviations. (C) Weekly footpad measurements (four per group) represent the average foot pad swelling ± one standard deviation. Sera (four per group) were taken at days 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 35 after reinfection and analyzed for the production of NO2−-NO3−. ∗, P < 0.01 compared with IL-18+/+ mice; #, not significant compared with IL-18+/+ mice.

We simultaneously examined the involvement of IL-18 in generation of Th1 cells in L. major-infected mice (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the results in Fig. 4C, lymphocytes from popliteal lymph nodes of BALB/c mice produced little IFN-γ in response to ConA or SLA, although they strongly produced IL-4. In contrast, popliteal lymph node cells from both IL-18+/+ and IL-18−/− mice similarly and dominantly produced IFN-γ in response to ConA or SLA (Fig. 5B). Thus, IL-18 is not essential for induction of Th1 cells but is important for augmentation of Th1 cells to produce IFN-γ in vivo.

Finally, we investigated the role of endogenous IL-18 in induction and/or activation of memory T cells. We reinfected IL-18+/+ and IL-18−/− mice that were inoculated with 5 × 106 stationary-phase promastigotes 18 weeks before. As shown in Fig. 5C, these IL-18+/+ mice were shown to be immunized against L. major, because they responded to reinfection by prompt and augmented NO2−-NO3− production in serum (day 3; 145 μM). In contrast, IL-18−/− mice showed a very long-lasting footpad swelling and failed to produce NO2−-NO3− in their sera. These results may indicate that endogenous IL-18 is involved in induction and/or activation of memory cells against L. major infection.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shown that daily injection of IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) and IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) into L. major-susceptible BALB/c mice induces wound healing by induction and activation of Th1 cells, which also play a protective role in a subsequent infection with L. major. We also investigated a protective role of endogenous IL-18 by using anti-IL-18 Ab-treated C3H/HeN mice or IL-18−/− mice (C57BL/6 background). These mice showed prolonged footpad swelling and diminished NO production following L. major infection. Administration of IL-18 corrected these defects in IL-18−/− mice, but the absence of IL-18 did not affect development of Th1 cells, suggesting that IL-18 is not responsible for inducing Th1 cells. However, the memory response to L. major infection was severely suppressed in IL-18−/− mice, suggesting the importance of endogenous IL-18 for immunization and/or activation of memory cells.

Administration of IL-12 and IL-18 induces wound healing by induction and activation of Th1 cells.

The resistance and susceptibility of inbred strains of mice to L. major have been discussed in terms of the dichotomy of Th1 and Th2 responses (26, 36). Resistance to infection correlates well with the selective generation of an IFN-γ-producing Th1 cell response. It is well established that Th1 cells contribute host resistance by production of IFN-γ, which induces the activation of iNOS (5, 20, 23). The importance of iNOS-directed NO production is demonstrated by the failure of iNOS-deficient mice to heal infection (7, 55). Since IL-12 and IL-18 synergistically induce IFN-γ production from Th1 cells, we injected both IL-12 and IL-18 into L. major-susceptible BALB/c mice. Recently, we and others demonstrated that IL-12 renders T cells responsive to IL-18 by induction of IL-18Rα (56, 59). We and others also demonstrated that IL-18Rα is selectively expressed on Th1 cells but not on Th2 cells (56, 59). Thus, we first determined the minimal dose of IL-12 required for induction of IL-18Rα on T cells (Fig. 1A), because daily injection of high doses of IL-12 is toxic to the host (13). We found that daily injection of 10 ng of IL-12 (a nontoxic dose) into the mouse is sufficient for induction of IL-18Rα (Fig. 1A). Thus, we injected 10 ng of IL-12 and various doses of IL-18. In this report, we showed that administration of the combination of IL-12 (10 ng/mouse) and IL-18 (1,000 ng/mouse) to L. major-infected BALB/c mice strongly protected them from footpad swelling by killing parasites in macrophages (Fig. 1C and D). Since same treatment of IFN-γ−/− BALB/c mice failed to induce wound healing (Fig. 2A), this protection is entirely dependent on the action of IFN-γ. Importantly, BALB/c mice that recovered from L. major infection after treatment with IL-12 and IL-18 became highly resistant to reinfection (Fig. 3A), suggesting that these BALB/c mice were properly immunized against L. major infection. Indeed, similar to C3H/HeN mice, these BALB/c mice increased their serum NO2−-NO3− levels after reinfection (Fig. 3B).

This treatment with IL-18 has several advantages. First, we could decrease the dose of IL-12 to the minimum that is required for induction of IL-18R. Second, IL-12 and IL-18 synergistically induce IFN-γ production and subsequent NO production, providing the best stimulation for induction of production of NO, a lethal molecule for L. major. Third, injection of IL-18 without IL-12 could be used as an effective treatment of the hosts that have intact IL-12 production but lack IL-18 production. Fourth, treated mice become healthy and resistant to reinfection. We could assume that IL-18, combined with CD4+-T-cell depletion, IL-4 neutralization, and intralesion IL-12 (18), may provide us with a highly effective means for the treatment of advanced leishmaniasis.

It has been demonstrated that BALB/c mice vaccinated with either SLA or single parasite leishmania homolog of receptors for activated C kinase (LACK) protein in the presence of IL-12 are protected from subsequent challenge with L. major in a Th1-dependent manner (1, 30). Gurunathan et al. reported that vaccination with DNA encoding the immunodominant LACK parasite antigen can elicit prolonged protective immunity to L. major in an IL-12- and IFN-γ-dependent manner (11, 12). Recombinant leishmania protein (LeIF) has been shown to stimulate the Th1 response and protect BALB/c mice from L. major in an IL-12- and IL-18-dependent manner (42). From these results, LACK DNA may stimulate macrophages to produce IL-12 and IL-18. Thus, administration of IL-12 and IL-18 provides us with good means for the treatment of L. major infection. Furthermore, this combination of IL-12 and IL-18 with proper leishmanial antigens may allow us to rationally design L. major vaccination.

Role of endogenous IL-18 in host resistance to L. major infection.

Recently, IL-18−/− mice were shown to display reduced production of IFN-γ, impaired NK cell activity, and defective Th1 cell development in response to bacillus Calmette-Guérin (Mycobacterium bovis BCG) (46). Therefore, it is important to examine the involvement of endogenous IL-18 in the development of Th1 cells in L. major-resistant C3H/HeN mice or C57BL/6 mice after infection.

Administration of neutralizing anti-IL-18 Ab to C3H/HeN mice reduced their resistance by down-regulation of IFN-γ-mRNA expression in their lymph node cells (data not shown) and subsequent IFN-γ-dependent NO production (Fig. 4A and B), suggesting that endogenous IL-18 is critically involved in up-regulation of IFN-γ-mRNA expression. However, this effect was only transient. When injection of anti-IL-18 Ab was stopped, these anti-IL-18 Ab-treated C3H/HeN mice quickly recovered from infection (Fig. 4A). This Ab treatment did not inhibit development of Th1 cells, because lymphocytes from L. major-infected C3H/HeN mice with or without anti-IL-18 Ab treatment produced IFN-γ equally in response to SLA or ConA (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, they equally expressed IL-18Rα chain mRNA (Fig. 4D), a Th1 cell marker (56, 59), while lymphocytes from L. major-infected BALB/c mice did not express IL-18Rα mRNA. Thus, even in anti-IL-18 Ab-treated C3H/HeN mice, these Th1 cells can produce IFN-γ in response to antigens derived from L. major plus IL-12 in vivo, leading to induction of production of low levels of NO (Fig. 4B). However, in C3H/HeN mice not treated with anti-IL-18 Ab, endogenous IL-18 can stimulate Th1 cells to increase IFN-γ production, causing peak NO production at 2 weeks after infection (Fig. 4B).

To further substantiate the protective role of endogenous IL-18, we infected IL-18−/− mice with the highly resistant C57BL/6 background with L. major. Although they needed a longer period to achieve cutaneous-lesion resolution, they eventually healed, suggesting that endogenous IL-18 partially contributes to the host defense. In contrast, IL-12-deficient mice suffer from progressive disease (29). Thus, IL-12 is essential for host defense, while IL-18 is not essential but may contribute to host defense mechanisms by hastening the period required for wound healing through the action to augment IFN-γ production.

Lymphocytes from wild-type mice and IL-18-deficient mice during infection showed comparable potentialities to produce IFN-γ in response to SLA or ConA in vitro (Fig. 5B), further indicating that Th1 cell development occurs without IL-18 in vivo. These results also strongly indicate that Th1 cells can produce IFN-γ without help from IL-18 in response to ConA or SLA in vitro. Exogenous IL-18 can up-regulate NO production (Fig. 5A), possibly by augmentation of IFN-γ production in vivo. Moreover, IL-18 may also increase IFN-γ production by NK cells at early stages of infection or by antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, which are known to be involved in the resistance to reinfection (12). As IL-18 deficient mice responded very poorly to reinfection (Fig. 5C), it is very intriguing to speculate on involvement of IL-18-stimulated CD8+ T cells in the memory response.

Recently, Wei et al. have reported that IL-18−/− mice (129/Sv × C57BL/6) are highly susceptible to L. major infection. Their IL-18−/− mice showed more apparent footpad swelling and more progressively developing lesions that become ulcerous at 40 days after infection (54). They reported decreased levels of IFN-γ in their IL-18−/− mice infected with L. major substrain LV39 (MRHO/SU/59/P), suggesting involvement of IL-18 in stimulation of Th1 cells in vivo. These investigators showed an impaired Th1 response (54). However, the IL-18−/− mice that we used showed no such impairment (Fig. 4C). We have used IL-18−/− mice (C57BL/6) which were backcrossed for eight generations onto C57BL/6 mice. We also tested IL-18−/− mice (129/Sv × C57BL/6) (data not shown). Compared with IL-18+/+ mice, both types of IL-18−/− mice showed long-lasting footpad swelling (Fig. 5A, upper panel, and data not shown). Indeed, IL-18−/− mice had a higher level of parasite burden than wild-type mice at 5 weeks after infection (data not shown). However, both types of IL-18−/− mice achieved complete lesion resolution at 15 weeks after infection without ulceration. Thus, our results differ from those of Wei et al. in several respects. Although there are many possibilities that account for this discrepancy, this difference may be explained by the difference between L. major substrain LV39 (MRHO/SU/59/P), used by Wei et al. (54), and MHOM/SU/73-5-ASKH, used by us. We assume that the LV39 (MRHO/SU/59/P) strain may be more virulent than MHOM/SU/73-5-ASKH, which we used. Alternatively, the MHOM/SU/73-5-ASKH strain may be more susceptible to NO than LV39 (MRHO/SU/59/P). Differences in susceptibility to L. major substrains have also been observed in IL-4R-deficient mice (31).

Thus, the absence of IL-18 partially influenced the host defense against primary infection (Fig. 5A). We also tested the role of endogenous IL-18 in host resistance against secondary infection. We found that IL-18−/− mice failed to show an appropriate secondary immune response (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that endogenous IL-18 contributes to the induction and/or activation of memory cells against L. major infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Hayashibara Biochemical Laboratories Inc. for providing us with recombinant murine IL-12 and IL-18 and for very helpful discussion.

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research and a Hitech Research Center Grant from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afonso L C, Scharton T M, Vieira L Q, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Scott P. The adjuvant effect of interleukin-12 in a vaccine against Leishmania major. Science. 1994;263:235–237. doi: 10.1126/science.7904381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belosevic M, Finbloom D S, Van der Medide P H, Slayter M V, Nacy C A. Administration of monoclonal anti-IFNγ antibodies in vivo abrogates natural resistance of C3H/HeN mice to infection with Leishmania major. J Immunol. 1989;143:266–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boom W H, Liebster L, Abbas A K, Titus R G. Patterns of cytokine secretion in murine leishmaniasis: correlation with disease progression or resolution. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3863–3870. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3863-3870.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Born T L, Thomassen E, Bird T A, Sims J E. Cloning of a novel receptor subunit, AcPL, required for interleukin-18 signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29445–29450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalton D K, Pitts-Meek S, Keshav S, Figari I S, Bradley A, Stewart T A. Multiple defects of immune cell function in mice with disrupted interferon-γ genes. Science. 1993;259:1739–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.8456300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dao T, Ohashi K, Kayano T. Interferon-γ-inducing factor, a novel cytokine, enhances fas ligand mediated cytotoxicity of murine T helper 1 cells. Cell Immunol. 1996;173:230–235. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diefenbach A, Schindler H, Donhauser N, Lorenz E, Laskay T, MacMicking J, Rollinghoff M, Gresser I, Bogdan C. Type 1 interferon (IFNα/β) and type 2 nitric oxide synthase regulate the innate immune response to a protozoan parasite. Immunity. 1998;8:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinarello C A. IL-18: a TH1-inducing, proinflammatory cytokine and new member of the IL-1 family. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green S J, Crawford R M, Hockmeyer J T, Meltzer M S, Nacy C A. Leishmania major amastigotes initiate the l-arginine-dependent killing mechanism in IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages by induction of tumor necrosis factor-α. J Immunol. 1990;145:4290–4297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu Y, Kuida K, Tsutsui H, Ku G, Hsiao K, Fleming M A, Hayashi N, Higashino K, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Kurimoto M, Tanimoto T, Flavell R A, Sato V, Harding M W, Livingston D J, Su M S. Activation of interferon-γ inducing factor mediated by interleukin-1β converting enzyme. Science. 1997;275:206–209. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurunathan S, Sacks D L, Brown D R, Reiner S L, Charest H, Glaichenhaus N, Seder R A. Vaccination with DNA encoding the immunodominant LACK parasite antigen confers protective immunity to mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1137–1147. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.7.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurunathan S, Prussin C, Sacks D L, Seder R A. Vaccine requirements for sustained cellular immunity to an intracellular parasitic infection. Nat Med. 1998;4:1409–1415. doi: 10.1038/4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall S S. IL-12 at the crossroads. Science. 1995;268:1432–1434. doi: 10.1126/science.7770767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinzel F P, Sadick M D, Holaday B J, Coffman R L, Locksley R M. Reciprocal expression of interferon γ or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinzel F P, Sadick M D, Mutha S S, Locksley R M. Production of interferon γ, interleukin 2, interleukin 4, and interleukin 10 by CD4+ lymphocytes in vivo during healing and progressive murine leishmaniasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7011–7015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinzel F P, Schoenhaut D S, Rerko R M, Rosser L E, Gately M K. Recombinant interleukin 12 cures mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1505–1509. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinzel F P, Rerko R M, Ahmed F, Pearlman E. Endogenous IL-12 is required for control of Th2 cytokine responses capable of exacerbating leishmaniasis in normally resistant mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:730–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinzel F P, Rerko R M. Cure of progressive murine leishmaniasis: interleukin 4 dominance is abolished by transient CD4(+) T cell depletion and T helper cell type 1-selective cytokine therapy. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1895–1906. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.12.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh C S, Macatonia S E, Tripp C S, Wolf S F, O'Garra A, Murphy K M. Development of TH1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science. 1993;260:547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel R M, Aguet M. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-γ receptor. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyodo Y, Matsui K, Hayashi N, Tsutsui H, Kashiwamura S I, Yamauchi H, Hiroishi K, Takeda K, Tagawa Y I, Iwakura Y, Kayagaki N, Kurimoto M, Okamura H, Hada T, Yagita H, Akira S, Nakanishi K, Higashino K. IL-18 up-regulates perforin-mediated NK activity without increasing perforin messenger RNA expression by binding to constitutively expressed IL-18 receptor. J Immunol. 1999;162:1662–1668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohno K, Kataoka J, Ohtsuki T, Suemoto Y, Okamoto I, Usui M, Ikeda M, Kurimoto M. IFN-γ-inducing factor (IGIF) is a costimulatory factor on the activation of Th1 but not Th2 cells and exerts its effect independently of IL-12. J Immunol. 1997;158:1541–1550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liew F Y, Li Y, Millott S. Tumor necrosis factor-α synergizes with IFN-γ in mediating killing of Leishmania major through the induction of nitric oxide. J Immunol. 1990;145:4306–4310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liew F Y, Li Y, Moss D, Parkinson C, Rogers M V, Moncada S. Resistance to Leishmania major infection correlates with the induction of nitric oxide synthase in murine macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:3009–3014. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liew F Y, Li Y, Severn A, Millott S, Schmidt J, Salter M, Moncada S. A possible novel pathway of regulation by murine T helper type-2 (Th2) cells of a Th1 cell activity via the modulation of the induction of nitric oxide synthase on macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2489–2494. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louis J, Himmelrich H, Parra-Lopez C, Tacchini-Cottier F, Launois P. Regulation of protective immunity against Leishmania major in mice. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:459–464. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magram J, Connaughton S E, Warrier R R, Carvajal D M, Wu C Y, Ferrante J, Stewart C, Sarmiento U, Faherty D A, Gately M K. IL-12-deficient mice are defective in IFN-γ production and type 1 cytokine responses. Immunity. 1996;4:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui K, Yoshimoto T, Tsutsui H, Hyodo Y, Hayashi N, Hiroishi K, Kawada N, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Higashino K. Propionibacterium acnes treatment diminishes CD4+NK1.1+ T cells but induces type 1 T cells in the liver by induction of IL-12 and IL-18 production from Kupffer cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattner F, Magram J, Ferrante J, Launois P, Di P K, Behin R, Gately M K, Louis J A, Alber G. Genetically resistant mice lacking interleukin-12 are susceptible to infection with Leishmania major and mount a polarized Th2 cell response. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1553–1559. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mougneau E, Altare F, Wakil A E, Zheng S, Coppola T, Wang Z E, Waldmann R, Locksley R M, Glaichenhaus N. Expression cloning of a protective Leishmania antigen. Science. 1995;268:563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.7725103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noben-Trauth N, Paul W E, Sacks D L. IL-4- and IL-4 receptor-deficient BALB/c mice reveal differences in susceptibility to Leishmania major parasite substrains. J Immunol. 1999;162:6132–6140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Garra A. Cytokines induce the development of functionally heterogeneous T helper cell subsets. Immunity. 1998;8:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamura H, Tsutsi H, Komatsu T, Yutsudo M, Hakura A, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Okura T, Nukada Y, Hattori K, Akita K, Namba M, Tanabe F, Konishi K, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M. Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-γ production by T cells. Nature. 1995;378:88–91. doi: 10.1038/378088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okamura H, Tsutsui H, Kashiwamura S I, Yoshimoto T, Nakanishi K. Interleukin-18: a novel cytokine that augments both innate and acquired immunity. Adv Immunol. 1998;70:281–312. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiner S L, Zheng S, Wang Z E, Stowring L, Locksley R M. Leishmania promastigotes evade interleukin 12 (IL-12) induction by macrophages and stimulate a broad range of cytokines from CD4+ T cells during initiation of infection. J Exp Med. 1994;179:447–456. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiner S L, Locksley R M. The regulation of immunity to Leishmania major. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:151–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson D, Shibuya K, Mui A, Zonin F, Murphy E, Sana T, Hartley S B, Menon S, Kastelein R, Bazan F, O'Garra A. IGIF does not drive Th1 development but synergizes with IL-12 for interferon-γ production and activates IRAK and NF-κB. Immunity. 1997;7:571–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadick M D, Heinzel F P, Holaday B J, Pu R P, Dawkins R S, Locksley R M. Cure of murine leishmaniasis with anti-interleukin 4 monoclonal antibody. Evidence for a T cell-dependent, interferon γ-independent mechanism. J Exp Med. 1990;171:115–127. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott P, Natovitz P, Coffman R L, Pearce E, Sher A. Immunoregulation of cutaneous leishmaniasis. T cell lines that transfer protective immunity or exacerbation belong to different T helper subsets and respond to distinct parasite antigens. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1675–1684. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.5.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seder R A, Gazzinelli R, Sher A, Paul W E. Interleukin 12 acts directly on CD4+ T cells to enhance priming for interferon γ production and diminishes interleukin 4 inhibition of such priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10188–10192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sher A, Coffman R L. Regulation of immunity to parasites by T cells and T cell-derived cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:385–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skeiky Y A, Kennedy M, Kaufman D, Borges M M, Guderian J A, Scholler J K, Ovendale P J, Picha K S, Morrissey P J, Grabstein K H, Campos-Neto A, Reed S G. LeIF: a recombinant Leishmania protein that induces an IL-12-mediated Th1 cytokine profile. J Immunol. 1997;161:6171–6179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soong L, Xu J C, Grewal I S, Kima P, Sun J, Longley B J, Jr, Ruddle N H, McMahon-Pratt D, Flavell R A. Disruption of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions results in an enhanced susceptibility to leishmania amazonensis infection. Immunity. 1996;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stenger S, Donhauser N, Thuring H, Rollinghoff M, Bogdan C. Reactivation of latent leishmaniasis by inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1501–1514. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sypek J P, Chung C L, Mayor S E, Subramanyam J M, Goldman S J, Sieburth D S, Wolf S F, Schaub R G. Resolution of cutaneous leishmaniasis: interleukin 12 initiates a protective T helper type 1 immune response. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1797–1802. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeda K, Tsutsui H, Yoshimoto T, Adachi O, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Defective NK cell activity and Th1 response in IL-18-deficient mice. Immunity. 1998;8:383–390. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torigoe K, Ushio S, Okura T, Kobayashi S, Taniai M, Kunikata T, Murakami T, Sanou O, Kojima H, Fujii M, Ohta T, Ikeda M, Ikegami H, Kurimoto M. Purification and characterization of the human interleukin-18 receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25737–25742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsutsui H, Nakanishi K, Matsui K, Higashino K, Okamura H, Miyazawa Y, Kaneda K. Interferon-γ-inducing factor up-regulates Fas ligand-mediated cytotoxic activity of murine natural killer cell clones. J Immunol. 1996;157:3967–3973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsutsui H, Matsui K, Kawada N, Hyodo Y, Hayashi N, Okamura H, Higashino K, Nakanishi K. IL-18 accounts for both TNF-α- and FasL-mediated hepatotoxic pathways in endotoxin-induced liver injury. J Immunol. 1997;159:3961–3967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ushio S, Namba M, Okura T, Hattori K, Nukada Y, Akita K, Tanabe F, Konishi K, Micallef M, Fujii M, Torigoe K, Tanimoto T, Fukuda S, Ikeda M, Okamura H, Kurimoto M. Cloning of the cDNA for human IFN-γ-inducing factor, expression in Escherichia coli, and studies on the biologic activities of the protein. J Immunol. 1996;156:4274–4279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vieira L Q, Hondowicz B D, Afonso L C, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Scott P. Infection with Leishmania major induces interleukin-12 production in vivo. Immunol Lett. 1994;40:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z E, Reiner S L, Zheng S, Dalton D K, Locksley R M. CD4+ effector cells default to the Th2 pathway in interferon γ-deficient mice infected with Leishmania major. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1367–1371. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei X Q, Leung B P, Neidbala W, Piedrafita D, Feng G J, Sweet M, Dobbie L, Smith A J, Liew F Y. Altered immune responses and susceptibility to Leishmania major and Staphylococcus aureus infection in IL-18-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:2821–2828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei X Q, Charles I G, Smith A, Ure J, Feng G J, Huang F P, Xu D, Muller W, Moncada S, Liew F Y. Altered immune responses in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;375:408–411. doi: 10.1038/375408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu D, Chan W L, Leung B P, Hunter D, Schulz K, Carter R W, McInnes I B, Robinson J H, Liew F Y. Selective expression and functions of interleukin 18 receptor on T helper (Th) type 1 but not Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1485–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang J, Murphy T L, Ouyang W, Murphy K M. Induction of interferon-γ production in Th1 CD4+ T cells: evidence for two distinct pathways for promoter activation. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:548–555. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<548::AID-IMMU548>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshimoto T, Okamura H, Tagawa Y, Iwakura Y, Nakanishi K. Interleukin 18 together with interleukin 12 inhibits IgE production by induction of interferon-γ production from activated B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3948–3953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshimoto T, Takeda K, Tanaka T, Ohkusu K, Kashiwamura S I, Okamura H, Akira S, Nakanishi K. IL-12 up-regulates IL-18 receptor expression on T cells, Th1 cells, and B cells: synergism with IL-18 for IFN-γ production. J Immunol. 1998;161:3400–3407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshimoto T, Nagai N, Ohkusu K, Ueda H, Okamura H, Nakanishi K. LPS-stimulated SJL macrophages produce IL-12 and IL-18 that inhibit IgE production in vitro by induction of IFN-γ production from CD3intIL-2Rβ+ T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:1483–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]