Abstract

The aim of this systematic review was to identify randomized controlled trials that looked at the effects of Nigella sativa in any form on different skin diseases. Up to March 2022, the online databases of Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, and Cochrane trials were searched. This study included 14 records of people who had experienced different types of skin disease including atopic dermatitis, vulgaris, arsenical keratosis, psoriasis, vitiligo, acute cutaneous leishmaniasis, warts, eczema, and acne. The mean SD age of the patients was 28.86 (4.49); [range: 18.3–51.4], with females accounting for 69% (506 out of 732) of the total. The follow-up mean SD was 8.16 (1.3) (ranged: 4 days to 24 weeks). The odds ratio (OR) was found to be 4.59 in a meta-analysis (95% CI: 2.02, 10.39). Whereas the null hypothesis in this systematic review was that lotion had no impact, OR 4.59 indicated that lotion could be effective. The efficacy of N. sativa essential oil and extract has been demonstrated in most clinical studies. However, more research is needed to completely evaluate and validate the efficacy or inadequacy of therapy with N. sativa, although it appears that it can be used as an alternative treatment to help people cope with skin problems.

1. Introduction

The skin is the largest organ and functions as a barrier to protect the underlying tissues against the elements and pathogens, while also fulfilling many physiological roles and biochemical functions such as preventing excessive water loss [1]. Skin diseases have recently become a major concern among people of all ages due to their highly visible symptoms and persistent and difficult treatment that have a significant effect on quality of life [2].

Nigella sativa belongs to the Ranunculaceae family is an annual plant which distributed in southern Europe and some parts of Asia, including Syria, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and India. Different active pharmaceutical ingredients have been identified in the N. sativa seeds, including saponins, flavonoids, cardiac glycosides, thymoquinone, thymol, limonene, carvacrol, p-cymene, alpha-pinene, 4-terpineol, longifolene, t-anethole benzene, isoquinoline, and pyrazole alkaloids, as well as unsaturated fatty acid such as linoleic acid, oleic acid, and palmitic acid [3]. Food and therapeutic uses of N. sativa oil seeds have a long history in Persian traditional medicine. Avicenna, in his famous book, The Canon of Medicine, has reported several black cumin properties, such as fatigue improvement and energy recovery. It has been traditionally used for the treatment of asthma, bronchitis, and rheumatism.

Animal models have shown the therapeutic effects of N. sativa on acne vulgaris, burns, wounds, and injury [4–7], skin inflammation [8], and skin pigmentation [9].

Since traditional treatments have become widely popular in recent decades, it is imperative to provide patients with skin diseases enough evidence-based alternatives to help them manage their symptoms. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the overall effectiveness of N. sativa products for treating skin problems.

2. Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we preferred reporting items according (PRISMA) guideline (Supplementary file S1).

2.1. Data Sources

The electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Google Scholar (Supplementary file S2) were searched until March 2022. To find more relevant studies, the reference lists of all eligible studies and previous reviews were reviewed manually.

2.2. Search Strategy and Study Selection

The MESH and non-MESH search terms applied were (“Nigella sativa∗” OR “Kalonj∗” OR “Black Cumin∗”) AND (“Acne Vulgaris” OR Dandruff OR “Atopic Dermatitis” OR “Contact Dermatitis” OR “Exfoliative Dermatitis” OR “Perioral Dermatitis” OR “Seborrheic Dermatitis” OR Eczema OR Hirsutism OR Ichthyosis OR “Seborrheic Keratosis” OR “Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus” OR “Discoid Lupus Erythematosus” OR “Phototoxic Dermatitis” OR “Phototoxic Dermatitis” OR “Hyperpigmentation” OR “Hypopigmentation” OR “Pruritus Ani” OR “Pruritus Vulvae” OR “Acne Vulgaris” OR “Seborrheic Dermatitis” OR “Psoriasis”). In our search strategy, study designs, participants, publication time, and language were deliberately not limited in order to facilitate finding all the relevant studies. All searches were conducted by two researchers (NM and MI) independently. Duplicated studies were then eliminated. In general, these two authors had an agreement on selecting the studies, and possible variations were removed by discussion.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

If a study met the following criteria, it was considered for inclusion: (1) patients with mild to severe skin disorders were recruited, (2) using of any products of N. sativa in the forms of oral and topical (3) the type of skin disorders conditions experienced by the participants was not restricted, (4) utilized N. sativa in combination with other plants, phytochemicals, drugs, or supplements; (5) controlled clinical trials of either parallel or crossover design.

We excluded research that involved: (1) Publications without accessible English abstracts, as were reviews, case reports, comments, theses, book sections, and conference proceedings. (2) Employed animal models.

2.4. Data Collection

Two authors (NM and MI) independently extracted data, including first author, publication date, study type, location, total, sample size, age, sex, and dose, form (powder, oil, and extract), duration of treatment, main outcomes (mean and standard deviation), and adverse effects.

2.5. Quality assessment of the Evidence

The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal technique was used to assess the quality of the studies included. Joanna Briggs proposed 13 criteria for evaluating the quality of randomization clinical trial trials. The Joanna Briggs Institute critical evaluation was also used for case series and quasi-experimental investigations. Adjudication was utilized to resolve differences in the grade of risk of bias studies.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were presented using descriptive statistics (mean ± SD) for continuous variables; frequency and percentage for categorical variables. We applied random-effectsmeta-analysis to calculate risk ratio and 95% confidence interval in Stata version 14.2.

3. Results

3.1. Studies Characteristics

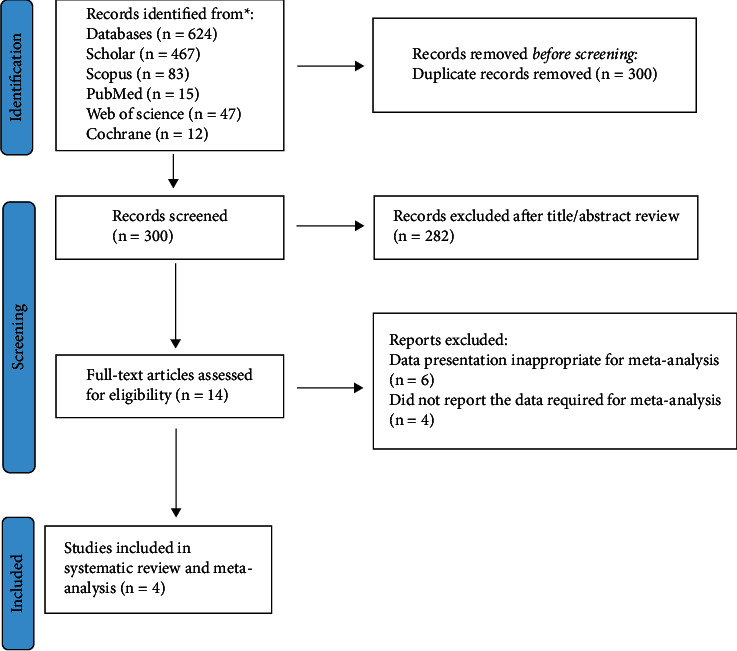

The list of included studies on skin disease therapeutic effects with N. sativa is shown in Table 1. In all, 14 records out of 300 unique articles were possibly eligible; ultimately, 4 papers were included in this meta-analysis [11, 12, 14, 15] (Figure 1). Of the 14 included studies, one was conducted in Germany [10], the Czech Republic [11], Tukey [22], India [13], and Bangladesh [17], two were conducted in Iraq [14, 18], and the other was carried out in Iran [12, 15, 16, 19–21, 23]. Studies were done on individuals who had experienced different types of skin disease, as listed in Table 1. In the clinical trials studied in this review, N. sativa oil was administered in 12 studies, and in two N. sativa studies crude extract was administered [12, 18].

Table 1.

The list of included studies on skin disease therapeutic effects with N. sativa.

| Authors/years | Study design | Type of skin disease | Age | Sample size | Forms of drug use | Dosage | Duration | Improvement frequency | Clinical score index before/after treatment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stern et al./2002 | Prospective | Atopic dermatitis | Nr | 20 | Topical (ointment) | 15% black seed oil other daily | 4 weeks | Nr | 1.71/1.01% | [10] |

| Kalus et al./2003 | Double-blinded RCT | Atopic eczema | 6–19 | 63 | Oral (500 mg capsule) | Seed oil (40 mg/kg) three times a day | 8 weeks | Invention group = 25/41, control = 9/22 | Nr | [11] |

| Rezaei et al./2005 | Double-blinded RCT | Wart | 12–18 | 291 | Topical (ointment) | 30 g crude extract twice daily | 6 weeks | Invention group = 42/43, control = 10/20 | Nr | [12] |

| Nawab et al./2008 | Before and after | Eczema | 10–70 | 30 | Topical (lotion) | 25 mg oil 4 times a day | 6 weeks | Nr | Eczema severity (itching) = 30/9 (papules) 19/4 | [13] |

| Al-Harchon/2010 | Single-blind RCT | Acne vulgaris | 13–23 | 93 | Topical (lotion) | 10% oil twice daily | 8 weeks | Invention group = 25/47, control = 3/38 | Nr | [14] |

| Nilforoushzadeh et al./2010 | Double-blinded RCT | Acute cutaneous leshmaniasis | 20/81 ± 12/26 | 150 | Topical (lotion) | 60% oil twice daily | 12 weeks | Invention group = 61/75, control = 48/75 | Nr | [15] |

| Yousefi et al./2013 | Double-blinded RCT | Eczema | 18–60 | 60 | Topical (lotion) | 1 g seed oil twice daily | 4 weeks | Nr | Nr | [16] |

| Bashar et al./2014 | Double-blind, RCT | Arsenical keratosis | 20–36 | 36 | Oral (500 mg) | Seed oil | 8 weeks | Nr | Palmar arsenical keratosis: 99.3 ± 21.5 and 62.3 ± 14.3 | [17] |

| Ahmed Jawad et al./2014 | RCT | Psoriasis | 50–70 | 60 | Topical (ointment), oral | Crude extract (10% (w/w) and 500 mg capsule) three times daily | 12 weeks | Nr | PASI (psoriasis area and severity index) score in group 1: 9.0 ± 3.7/4.3 ± 2.0, group 2: 9.9 ± 3.4/5.4 ± 2.7, Group 3: 10.9 ± 2.7/4.2 ± 1.7 | [18] |

| Ghorbanibirgani et al./2014 | Double blind, RCT | Vitiligo | 43.65 ± 3.21 | 52 | Topical (lotion) | 100 g seed oil | 24 weeks | Nr | Vitiligo area scoring index in control group: 4.98 ± 4.81/4.62 ± 4.36, in invention 4.98 ± 4.81/3.75 ± 3.91 | [19] |

| Rafati et al./2014 | RCT | Infant skin infections | 6–11 days | 60 | Topical (lotion) | 33% oil three times a day | 4 days | Nr | Nr | [20] |

| Rafati et al./2019 | Double-blinded, RCT | Acute radiation dermatitis | ≥18 years | 62 | Topical (gel lotion) | 50 g gel lotion 5% twice a day | 6 weeks | Nr | Nr | [21] |

| Sarac et al./2019 | Clinical trials with a pre- and a post-treatment | Vitiligo | 20–85 | 33 | Topical (cream) | Oil/twice a day | 24 weeks | Invention group = 23/33 | Nr | [22] |

| Soleymani et al./2020 | Double-blind RCT | Acne | 14–35 | 60 | Topical (gel lotion) | 1% oil/twice a day | 8 weeks | Nr | Comedone number invention = 8.07 ± 6.142/1.11 ± 1.812, in control + 8.87 ± 5.526/8.44 ± 5.437, papule number invention: 11.47 ± 6.426/1.89 ± 1.729, in control = 8.43 ± 4.116/7.31 ± 4.306 | [23] |

Nr: not reported.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of studies included in the systematic review the therapeutic effects of N. sativa on skin disease.

3.2. Adverse Effects

Out of the three studies that evaluated the adverse effects of treatment with N. sativa, Kalus et al. reported transient gastrointestinal problems [11]. One study reported that 62% of participants in the invention group had gastric irritation, including abdominal cramps, and indigestion [17], and the other 5 out of 75 patients in the N. sativa group (6.7%) reported topical side effects among patients [15].

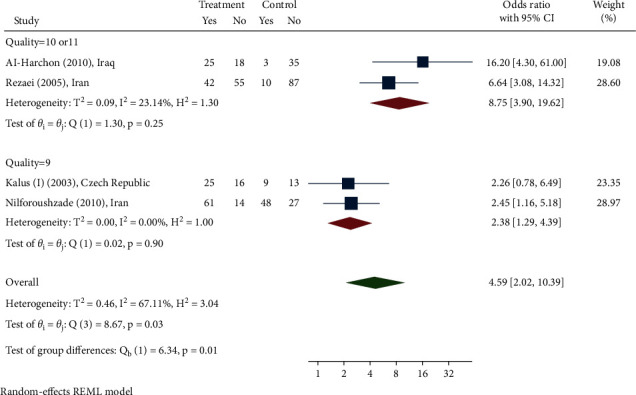

3.3. Findings from the Meta-Analysis

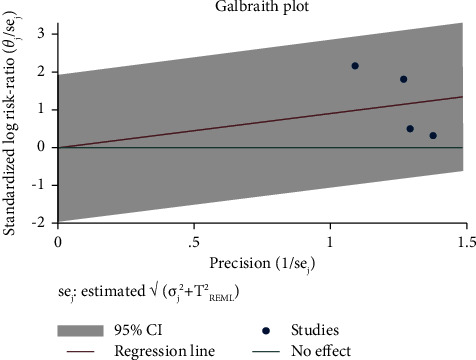

A total of 1159 patients were included in the systematic review. The mean SD age of the patients was 28.86 (4.49); [range: 18.3–51.4], with females accounting for 69% (506 out of 732) of the total. The follow-up mean SD was 8.16 (1.3) (ranged: 4 days to 24 weeks). The odds ratio (OR) was found to be 4.59 in a meta-analysis (95% CI: 2.02, 10.39). Whereas the null hypothesis in this systematic review was that lotion had no impact, OR 4.59 indicated that lotion could be effective. Based on the value of I2 = 67.11 (Figure 2) and Galbraith diagram (Figure 3), there was no significant heterogeneity between studies, but the value of T2 = 0.46 shows that there is significant heterogeneity within studies.

Figure 2.

Odds ratio for N. sativa's ability to treat skin diseases.

Figure 3.

Galbraith plot in study on N. sativa's impact on skin conditions.

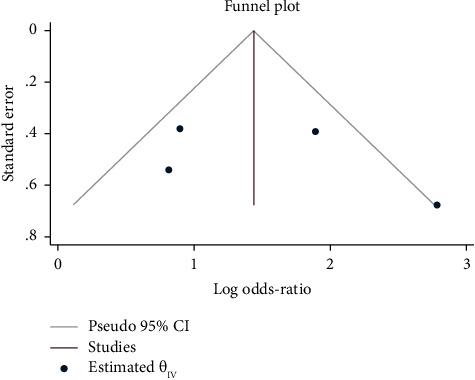

The results of the study do not appear to be impacted by publication bias, according to the funnel plot (Figure 4) and the Egger's test (B = 3.54, p value = 0.36), although the assessment of the publication bias is unreliable because there were only four papers included in the meta-analysis. Based on the findings of the sensitivity analysis, the results were influenced by one study [14]. When the recent study was taken out of the sensitivity analysis, the results were 3.45 less than the estimated value. As can be seen from the subgroup analysis, it appears that this study had an influence on the study's findings.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of publication bias for the effect of N. sativa's ability to treat skin diseases.

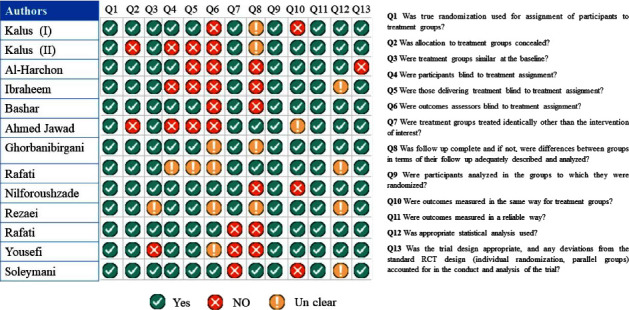

3.4. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

As a result, the quality of the included studies is assessed using the critical assessment tool for randomization clinical trials developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute. To evaluate the quality of case series and quasi-experimental research, please consult Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Quality assessment of study included in the systematic review the therapeutic effects of N. sativa on skin disease.

4. Discussion

The current meta-analysis revealed that supplementation with N. sativa can potentially be effective in the treatment of different skin problems including atopic dermatitis, eczema, warts, keratosis, psoriasis, vitiligo, infant skin infections, and acne. However, the findings should be declared with caution because of heterogenicity. The studies included in the meta-analysis were homogeneous, and the differences between the studies did not significantly affect the estimated index, according to the value of the I2 index. However, there was heterogeneity within studies through using Galbraith diagram. Heterogeneity is an important consideration in systematic reviews, as high heterogeneity (more than 75%) indicates that it is not suitable to perform meta-analysis. To the best of our knowledge, there is no systematic review that has examined the effects of N. sativa on the improvement of symptoms of skin diseases. The study of the various forms of N. sativa showed that the oil supplement in topical form is more commonly reported. The pharmacological properties of N. sativa are more clearly observable in this form than in extract form because thymoquinone is a solvent in oil. A minimum of 4 weeks and a maximum of 24 weeks are recommended for the treatment period. The dermatological treatments of N. sativa are attributed to its strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and immunomodulatory potential, which altogether make it a promising skincare candidate. Since thymoquinone is one of the principal compounds of N. sativa and the concentration of it may be varied greatly depending on the storage and preparation of plant products, it is expected that the prescribed herbal products will be standardized according to the active ingredient thymoquinone. However, there is no information regarding the quantification or standardization of bioactive compounds among the clinical trials reviewed here. Standardization of herbal formulations is necessary in order to evaluate the quality of drugs based on the concentration of their active constituents or phytochemicals [24]. Standardization of herbal medicines carries an assurance of quality, efficacy, safety, and reproducibility [25]. Thymoquinone exists in tautomeric forms including the enol, keto, and mixtures in the oil of the plant. The keto form is responsible for the pharmacological features of thymoquinone [26]. Several potential mechanisms can be proposed for the observed ameliorating influences of N. sativa on infectious and noninfectious skin conditions including different types of allergies, autoimmunity, skin inflammations and wounds, and vitiligo. The findings of Ali and Meitei showed that the extract of N. sativa, as well as its active constituent thymoquinone, mimics the action of acetylcholine in melanin dispersion leading to skin darkening via stimulation of cholinergic receptors of a muscarinic nature within the melanophores of wall lizard. This study opens new vistas for the use of N. sativa active ingredient, thymoquinone, as a novel melanogen for its clinical application in skin disorders such as hypopigmentation or vitiligo [9].

Generally, there is an agreement regarding the impressive effects of N. sativa on inflammatory, oxidative, reactive oxygen species, and immunologic parameters in animal models. Houghton et al. showed that the anti-inflammatory action of TQ resulted from the prevention of eicosanoids generation, such as thromboxane B2 and leukotriene (LT) B4, by inhibiting both cyclooxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase, and in part via nonenzymatic peroxidation of membrane lipids [27]. TQ induce a significant inhibition on LTC4 synthase activity [28]. Velagapudi et al. demonstrated that TQ treatment elevated the activation of the NrF2/ARE pathway leading to the suppression on NF-κB and following neuroinflammatory responses in microglia cells [29]. TQ was recently discovered to attenuate atopic dermatitis by reducing the levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, and IFN-gamma, and immunomodulatory cells in the blood. However, Liang et al. indicated that a high dose of TQ (higher than 16 μM) possibly showed cytotoxicity on keratinocytes [8]. So, in clinical trials must be consider the standardization of the plant. 12 studies out of 14 in this review have reported the efficacy of essential oils of black cumin in skin disease. In light of the relatively low amount of TQ in the N. sativa essential oil, it seems that the skin healing effects of N. sativa are related to terpenoid compounds in addition to TQ. Therefore, the determination of these active constituents is recommended to achieve the N. sativa oil optimal dose to improve its efficacy. The previous investigations have shown the essential oil immunostimulatory effects on T cells and meaningfully inhibited allergy-associated cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 [30]. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of some other constituents of N. sativa essential oil such as p-cymene, t-anethole, thymol, carvone, α-terpineol, longifolene, and β-caryophyllene have been demonstrated in various studies [30–36].

5. Limitations

There were some limitations on these clinical studies, including the lack of reporting of any herbal standardization, the lack of measurement of chemical constituents of the plant, and study quality. The findings of this review should be considered cautiously due to various limitations. The fact that this study looked at skin disorders in general, and the number of clinical studies included in the meta-analysis was small (n = 4), so in the main analysis, therefore, limiting the sample size decreases the study's confidence level and increases the margin of error. The protocol for this review was has not been preregistered with PROSPERO, so it is a limitation of this review.

6. Conclusions

The efficacy of N. sativa essential oil and extract has been demonstrated in most clinical studies. This is the first systematic review assessing the available literature on the effects of N. sativa on skin diseases in clinical studies. In this systematic review article, we tried to give persuasive clues on the efficacy of N. sativa in skin disorders management and its mechanisms of action. However, more research is needed to completely evaluate and validate the efficacy or inadequacy of therapy with N. sativa, although it appears that it can be used as an alternative treatment to help people cope with skin problems.

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in this article from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Neda Mohamadi designed the study and wrote the draft of the manuscript; Mozhde Ilaghi Nezhad, Fariba Sharififar, and Mahdieh Khazaneha did search and contributed to the data collections; Naser Nasiri and Mohammad Javad Najafzadeh contributed to meta-analysis.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file S2: critical appraisal for quasi-experimental studies included in the review.

References

- 1.Abbasi A. M., Khan M., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Jahan S., Sultana S. Ethnopharmacological application of medicinal plants to cure skin diseases and in folk cosmetics among the tribal communities of North-West Frontier Province, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2010;128(2):322–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afolayan A. J., Grierson D. S., Mbeng W. O. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in the management of skin disorders among the Xhosa communities of the Amathole District, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2014;153(1):220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kooti W., Hasanzadeh-Noohi Z., Sharafi-Ahvazi N., Asadi-Samani M., Ashtary-Larky D. Phytochemistry, pharmacology, and therapeutic uses of black seed (Nigella sativa) Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines . 2016;14(10):732–745. doi: 10.1016/s1875-5364(16)30088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yaman I., Durmus A., Ceribasi S., Yaman M. Effects of Nigella sativa and silver sulfadiazine on burn wound healing in rats. Veterinarni Medicina . 2010;55(12):619–624. doi: 10.17221/2948-vetmed. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu-Zinadah O. A. Using nigella sativa oil to treat and heal chemical induced wound of rabbit skin. Journal of King Abdulaziz University - Science . 2009;21(2):335–346. doi: 10.4197/sci.21-2.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nawarathne N. W., Wijesekera K., Gaya Bandara Wijayaratne W. M. D., Napagoda M. Development of novel topical cosmeceutical formulations from Nigella sativa L. with antimicrobial activity against acne-causing microorganisms. The Scientific World Journal . 2019;2019:7. doi: 10.1155/2019/5985207.5985207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirazi N., Nourbar E., Yari S., Rafieian-Kopaei M., Nasri H. Effect of hydroethanolic extract of Nigella sativa L. on skin wound healing process in diabetic male rats. International Journal of Preventive Medicine . 2019;10(1):p. 18. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.ijpvm_276_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang J., Lian L., Wang X., Li L. Thymoquinone, extract from Nigella sativa seeds, protects human skin keratinocytes against UVA-irradiated oxidative stress, inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction. Molecular Immunology . 2021;135:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali S. A., Meitei K. V. Nigella sativa seed extract and its bioactive compound thymoquinone: the new melanogens causing hyperpigmentation in the wall lizard melanophores. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology . 2011;63(5):741–746. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern T., Bayerl C. Schwarzkümmelöl-Salbe, eine neue Möglichkeit der topischen Behandlung des atopischen Ekzems? Aktuelle Dermatologie . 2002;28(3):74–79. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-25234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalus U., Pruss A., Bystron J., et al. Effect of Nigella sativa (black seed) on subjective feeling in patients with allergic diseases. Phytotherapy Research . 2003;17(10):1209–1214. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezaei K., Jebraeili R., Delfan B., Noorytajer M., Meshkat M. H., Maturianpour H. The effect of clove bud, Nigella and Salix alba on wart and comparison with conventional therapy. Editorial Advisory Board e . 2008;21(3):444–450. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nawab M., Mannan A., Siddiqui M. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of Unani formulation on eczema. Indian journal of indian journal . 2008;7(2):341–344. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Harchan N. A.-A. H. Treatment of acne vulgaris with nigella sativa oil lotion. Iraqi Academic Scientific Journals . 2010;9:2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilforoushzadeh M. A., Hejazi S. H., Zarkoob H., Shirani-Bidabadi L., Jaffary F. Efficacy of adding topical honey-based hydroalcoholic extract Nigella sativa 60% compared to honey alone in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis receiving intralesional glucantime. Journal of Skin and Leishmaniasis . 2009;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yousefi M., Barikbin B., Kamalinejad M., et al. Comparison of therapeutic effect of topical Nigella with Betamethasone and Eucerin in hand eczema. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology . 2013;27(12):1498–1504. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bashar T., Misbahuddin M., Hossain M. A. A double-blind, randomize, placebo-control trial to evaluate the effect of Nigella sativa on palmar arsenical keratosis patients. Bangladesh Journal of Pharmacology . 2014;9(1):15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed J. H., Ibraheem A. Y., Al-Hamdi K. I. Evaluation of efficacy, safety and antioxidant effect of Nigella sativa in patients with psoriasis: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Investigations . 2014;5:2. doi: 10.5799/ahinjs.01.2014.02.0387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghorbanibirgani A., Khalili A., Rokhafrooz D. Comparing Nigella sativa oil and fish oil in treatment of vitiligo. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal . 2014;16:e4515–e4516. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rafati S., Niakan M., Naseri M. Anti-microbial effect of Nigella sativa seed extract against staphylococcal skin Infection. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran . 2014;28:p. 42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rafati M., Ghasemi A., Saeedi M., et al. Nigella sativa L. for prevention of acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine . 2019;47 doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102205.102205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarac G., Kapicioglu Y., Sener S., et al. Effectiveness of topical Nigella sativa for vitiligo treatment. Dermatologic Therapy . 2019;32(4) doi: 10.1111/dth.12949.e12949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soleymani S., Zargaran A., Farzaei M. H., et al. The effect of a hydrogel made by Nigella sativa L. on acne vulgaris: a randomized double‐blind clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research . 2020;34(11):3052–3062. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer R. Quality criteria and standardization of phytopharmaceuticals: can acceptable drug standards be achieved? Drug Information Journal . 1998;32(1):101–110. doi: 10.1177/009286159803200114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sachan A. K., Vishnoi G., Kumar R. Need of standardization of herbal medicines in modern era. International Journal of Phytomedicine . 2016;8(3):300–307. doi: 10.5138/09750185.1847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darakhshan S., Bidmeshki Pour A., Hosseinzadeh Colagar A., Sisakhtnezhad S. Thymoquinone and its therapeutic potentials. Pharmacological Research . 2015;95-96:138–158. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houghton P. J., Zarka R., de las Heras B., Hoult J. Fixed oil of Nigella sativa and derived thymoquinone inhibit eicosanoid generation in leukocytes and membrane lipid peroxidation. Planta Medica . 1995;61(01):33–36. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansour M., Tornhamre S. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase and leukotriene C4 synthase in human blood cells by thymoquinone. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry . 2004;19(5):431–436. doi: 10.1080/14756360400002072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velagapudi R., Kumar A., Bhatia H. S., et al. Inhibition of neuroinflammation by thymoquinone requires activation of Nrf2/ARE signalling. International Immunopharmacology . 2017;48:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J., Choi W.-S., Kim K.-J., Eom C.-D., Park M.-J. Investigation of active anti-inflammatory constituents of essential oil from Pinus koraiensis (Sieb. et Zucc.) wood in LPS-stimulated RBL-2H3 cells. Biomolecules . 2021;11(6):p. 817. doi: 10.3390/biom11060817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Oliveira T. M., de Carvalho R. B. F., da Costa I. H. F., et al. Evaluation of p-cymene, a natural antioxidant. Pharmaceutical Biology . 2015;53(3):423–428. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.923003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Santana M. F., Guimarães A. G., Chaves D. O., et al. The anti-hyperalgesic and anti-inflammatory profiles of p-cymene: evidence for the involvement of opioid system and cytokines. Pharmaceutical Biology . 2015;53(11):1583–1590. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.993040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim K. Y., Lee H. S., Seol G. H. J. Anti-inflammatory effects of trans-anethole in a mouse model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2017;91:925–930. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braga P. C., Dal Sasso M., Culici M., Bianchi T., Bordoni L., Marabini L. Anti-inflammatory activity of thymol: inhibitory effect on the release of human neutrophil elastase. Pharmacology . 2006;77(3):130–136. doi: 10.1159/000093790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pombal S., Hernández Y., Diez D., et al. Antioxidant activity of carvone and derivatives against superoxide ion. Natural Product Communications . 2017;12(5) doi: 10.1177/1934578x1701200502.1934578X1701200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveira-Tintino C. D. d. M., Pessoa R. T., Fernandes M. N. M., et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-edematogenic action of the Croton campestris A. St.-Hil (Euphorbiaceae) essential oil and the compound β-caryophyllene in in vivo models. Phytomedicine . 2018;41:82–95. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file S2: critical appraisal for quasi-experimental studies included in the review.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in this article from the corresponding author upon request.