Abstract

Venomous snakes are important parts of the ecosystem, and their behavior and evolution have been shaped by their surrounding environments over the eons. This is reflected in their venoms, which are typically highly adapted for their biological niche, including their diet and defense mechanisms for deterring predators. Sub-Saharan Africa is rich in venomous snake species, of which many are dangerous to humans due to the high toxicity of their venoms and their ability to effectively deliver large amounts of venom into their victims via their bite. In this study, the venoms of 26 of sub-Saharan Africa's medically most relevant elapid and viper species were subjected to parallelized toxicovenomics analysis. The analysis included venom proteomics and in vitro functional characterization of whole venom toxicities, enabling a robust comparison of venom profiles between species. The data presented here corroborate previous studies and provide biochemical details for the clinical manifestations observed in envenomings by the 26 snake species. Moreover, two new venom proteomes (Naja anchietae and Echis leucogaster) are presented here for the first time. Combined, the presented data can help shine light on snake venom evolutionary trends and possibly be used to further improve or develop novel antivenoms.

Keywords: snakebite envenoming, sub-Saharan Africa, toxicovenomic, in vitro venom characterization, high-throughput assays, cytotoxicity, enzymatic activity of venoms

Introduction

In the deep jungles, on the open savanna, and across deserts, snakes are omnipresent in sub-Saharan Africa, where they play an integral role in the natural ecosystems to which they have adapted over the course of evolution [1]. Some of these snake species are highly venomous, being classified by the World Health Organization as category 1 or 2 snakes of the highest medical importance [2, 3]. Thus, understanding the composition and function of their venoms is not only important for elucidating basic biology and adaptation of species, but also of medical significance. Each year, venomous snakes inflict approximately 500,000 bites in Africa [4, 5], causing major disability and disablement for many rural workers and children [6]. This challenge remains a pressing health care issue, which is further exacerbated by the socioeconomic impact that disability causes for manual laborers [7].

The medically most important snakes of sub-Saharan Africa belong mainly to the Elapidae (e.g., cobras, mambas, and rinkhals) and Viperidae families, although a few species from the Colubridae family (e.g., boomslang, Dispholidus typus) are also known to cause severe envenomings. Victims envenomed by elapid snakes typically display local as well as systemic clinical manifestations. Local manifestation often includes swelling, blistering, and bruising at the anatomic site of the bite, which may evolve into irreversible tissue necrosis and gangrene [5, 8]. In comparison, systemic manifestations may include muscle twitching, spasms, weakness, fatigue, sleepiness, slurred speech, or difficulties in swallowing. These can progress to flaccid paralysis and, in severe cases, fatal respiratory failure, unless mechanical ventilation is provided [5, 9].

Similarly to elapids, envenomings caused by vipers may also result in both local and systemic manifestations. The victims often immediately feel a strong irradiating pain at the site of bite and typically show hot inflammatory erythema, blisters, bruises, and spontaneous bleeding [5]. Systemic clinical manifestations can include temporary loss of vision, fainting, and systemic hemorrhage, which in severe cases can lead to cardiovascular shock [5].

Different toxin families are responsible for the clinical manifestations observed for viper and elapid envenoming. As a first example, venoms from spitting cobras are rich in cytotoxins (CTxs) from the 3-finger toxin (3FTx) family and phospholipase A2s (PLA2s) [10], which interfere with and disrupt the integrity of cellular membranes, resulting in irreversible damage and cell death. In comparison, short- and long-chain α-neurotoxins, another type of 3FTx, found in venoms such as those of the black mamba and forest cobra, block neuromuscular signaling and prevent normal muscle contractions through binding to acetylcholine receptors in neuromuscular junctions [11]. Another example of a class of toxins that interfere with neuromuscular signaling are dendrotoxins. Dendrotoxins belong to the Kunitz-type inhibitors, are exclusively found in the venoms of mambas, and block ion transport through potassium channels, resulting in involuntary muscle contractions [12, 13]. Snake venoms from most viperid species possess a high fraction of PLA2s (e.g., Gaboon viper, Bitis gabonica), snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs) (e.g., carpet viper, Echis ocellatus), and snake venom serine proteinases (SVSPs) (e.g., horned viper, Cerastes cerastes), which all play important roles in the toxicity of these venoms. SVMPs hydrolyze components of the cell wall of capillaries, which first reduces the mechanical integrity and then disrupts the capillary walls, resulting in both local and systemic bleeding [14, 15]. Systemic bleeding can also be caused by SVSPs that interfere with the blood coagulation cascade by decreasing the level of platelets, fibrinogen, and clotting factors [5, 16].

So far, most venomic studies on African snakes have included only one or a small handful of species [17–21], and the inclusion of functional data has been somewhat sporadic or absent. These studies have undoubtedly been important for obtaining a first snapshot of venom compositions, which have already enabled further studies within venom evolution, snake biology, and development of (recombinant) antivenom. However, the fact that these studies have been performed in multiple different laboratories using different protocols results in a limited level of data harmonization. To this end, and to elucidate a few so far undescribed venom proteomes, we describe high-throughput methods for proteomics (i.e., venomics) and in vitro functional characterization of snake venoms (i.e., toxicovenomics) in a parallelized manner and characterize sub-Saharan Africa's 26 medically most important snakes, comprising 18 elapids and 8 vipers (Table 1).

Table 1:

List of the 26 venoms from the medically most relevant elapids and vipers from sub-Saharan Africa used in this study. Catalog number and origin are listed.

| Family | Genus (subgenus) | Snake | Catalog No. | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elapidae | Dendroaspis | D. angusticeps | L1307 | Tanzania |

| D. jamesoni | L1308 | Cameroon | ||

| D. polylepis | L1309 | Kenya, South Africa | ||

| D. viridis | L1310 | Ghana | ||

| Hemachatus | H. haemachatus | L1311 | South Africa | |

| Naja (Afronaja) | N. ashei | L1375 | Kenya | |

| N. katiensis | L1317 | Burkina Faso | ||

| N. mossambica | L1376 | South Africa, Tanzania | ||

| N. nigricincta | L1368 | South Africa | ||

| N. nigricollis | L1327 | Cameroon, Tanzania, West Africa | ||

| N. nubiae | L1342 | Egypt | ||

| N. pallida | L1321 | Kenya | ||

| Naja (Boulangerina) | N. melanoleuca | L1318 | Cameroon, Ghana, Uganda | |

| Naja (Uraeus) | N. anchietae | L1374 | Namibia | |

| N. annulifera | L1314 | Sub-Saharan Africa | ||

| N. haje | L1315 | Egypt, Mali | ||

| N. nivea | L1328 | South Africa | ||

| N. senegalensis | L1350 | Mali | ||

| Viperidae | Bitis | B. arietans | L1159 | Cameroon, Kenya, Mali, Saudi Arabia, West Africa, Tanzania |

| B. gabonica | L1104 | Burundi, Tanzania | ||

| B. nasicornis | L1106 | West Africa, Burundi | ||

| B. rhinoceros | L1105 | Ghana | ||

| Cerastes | C. cerastes | L1107 | Egypt, Tunisia | |

| Echis | E. leucogaster | L1109 | Mali | |

| E. ocellatus | L1114 | Cameroon, Mali, Ghana | ||

| E. pyramidum | L1110 | Egypt |

Material and Methods

Venoms and reagents

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise stated. High-purity venoms, from a pool of specimens for the 26 snakes in Table 1, were obtained from Latoxan (Portes lés Valence, France), stored at −20°C, and reconstituted in assay buffer just before use. PLA2 substrate 4-nitro-3-(octanoyloxy)benzoic acid (NOB) and SVMP substrate ES010 were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, New York, USA). SVSP substrate (p-tosyl-Gly-Pro-Arg)2-R110 and 96-well plates were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). All substrates for enzymatic assays were dissolved in DMSO to the stock concentration of 100 mM. CellTiter-Glo 3D Cell Viability Assay kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA).

Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

To record the chromatograms, the venoms were separated by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA) Infinity II as previously described [22]. Briefly, lyophilized venom (10 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of water containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA; solution A), centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes, and transferred to an HPLC vial. For each fractionation round, 100 µL of sample was injected into an RP-HPLC C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size) and eluted at 1 mL/min by applying a gradient toward acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA (solution B) (0–15% B for 10 minutes, 15–45% B for 60 minutes, 45–70% B for 10 minutes, and 70% B for 9 minutes).

Proteomic characterization of whole venom by mass spectrometry

In-solution tryptic digestion of the venom proteins

For each of the 26 snake venoms listed in Table 1, the lyophilized whole venom was dissolved in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then 5 µg was vacuum dried and resuspended in 20 µL of 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride containing 10 mM TCEP, 40 mM 2-chloroacetamide, and 50 mM HEPES (pH 8.5). After adding 40 µL of digestion buffer (10% acetonitrile, 50 mM HEPES pH 8.5), samples were digested with LysC endopeptidase (1:50; w/w) for 3 hours 30 minutes at 37°C. Samples were further diluted with 140 µL of digestion buffer and mixed with trypsin (1:100; w/w). Trypsinized samples were incubated overnight at 37°C, then diluted with 200 µL of 2% TFA to quench trypsin activity. Peptides were desalted on StageTip containing Empore C18 disks, eluted in 60 µL 40% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid (FA), dried in a vacuum centrifuge, and resuspended in 2% acetonitrile containing 1% TFA and iRT peptides (Biognosys, Schlieren, Switzerland).

Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry analysis

Mass spectrometry data were collected using a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Thermo EASY-nLC 1200 liquid chromatography (LC) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, 100 ng of peptides was loaded into a 2-cm C18 trap column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 164705) connected to a 15-cm reverse-phase analytical column (Thermo Fisher Scientific, ES900). Peptides were separated for 70 minutes with a gradient going from 10% to 60% buffer B (80% acetonitrile, 0.1% FA) over 60 minutes, until spiking to 95% buffer B for the last 10 minutes to wash the column. Full mass spectrometry (MS) spectra were collected at a resolution of 70,000, with an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 3 × 106 or maximum injection time of 20 ms and a scan range of 300 to 1,750 m/z. The MS2 spectra were obtained at a resolution of 17,500, with an AGC target value of 1 × 106 or maximum injection time of 60 ms, a normalized collision energy of 25, and an intensity threshold of 1.7 × 104. Dynamic exclusion was set to 60 seconds, and ions with a charge state <2 or unassigned were excluded.

Using proteome Discoverer 2.4, peptide fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) were searched against a database consisting of all Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL protein sequences from the Serpentes suborder available in Uniprot (331,759 entries; downloaded May 2022). The search was performed using the built-in Sequest HT algorithm, which was configured to derive fully tryptic peptides using default settings. Cysteine carbamidomethyl was set as a static modification and oxidation (M), deamidation (N, Q), and acetyl on protein N-termini were set as dynamic modifications. Label-free quantitation was enabled in both processing and consensus steps, with quantitation being done using Minora Feature Detector. All results were filtered at 1% false discovery rate, and relative protein abundances were estimated by calculating the ratio of the individual protein abundances to the sum of abundances of all proteins detected within a sample.

In vitro functional characterization of the whole venoms

PLA2 enzymatic activity assay

The endpoint PLA2 activity assay was run as described previously [23]. The snake venoms were dissolved at a concentration of 10 mg/mL in assay buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM CaCl2), and a 2-fold serial dilution (10 steps) was prepared. Then, 100 µL/well of each dilution was added to a 96-well plate, together with 100 µL/well of NOB (final concentration 0.25 mM). The plates were shaken at 300 rpm for 2 minutes and then incubated at 37°C for 40 minutes. The plates were then centrifuged (3,000 × g, 4°C, 3 minutes) before the absorbance was recorded at 405 nm using a VICTOR Nivo plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at 25°C. All reactions were run in duplicates and the absorbance values were shown as averages after subtracting a blank control containing no venom. EC50 values (the venom concentration inducing half of the maximum absorbance at 405 nm proportional to product conversion) were determined using nonlinear fitting with sigmoidal dose–response equation of the venom dose curves analyzed by GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

SVSP and SVMP enzymatic activity assay

To measure SVSP and SVMP activities, enzymatic assays were performed. The hydrolysis reactions were performed in 96-well plates with a final volume of 100 µL per well. The snake venoms were dissolved in PBS for SVSP or assay buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2) for SVMP assays at a concentration of 10 mg/mL, and 10 dilution steps of a 2-fold serial dilution were prepared. To start the reaction, 50 µL of 2 µM SVSP substrate R110 or 10 µM SVMP substrate ES010 was mixed with 50 µL of each snake venom concentration of the serial dilution. Fluorescence data were recorded using a VICTOR Nivo plate reader at 25°C. For the SVSP assay, an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm with 11 kinetic cycles and an interval of 90 seconds were used. For the SVMP assay, an excitation wavelength of 320 nm and an emission wavelength of 405 nm with 16 kinetic cycles and an interval of 90 seconds were used. The reactions were run in duplicate and a blank containing no venom was included.

The rate of relative fluorescence units per second (RFU/s) recorded for each venom concentration was the slope calculated from the linear fitting on its time–response curve. The rate values were then plotted against the venom concentration and a nonlinear fitting with a sigmoidal dose–response equation was used to determine the EC50 values (the venom concentration at which half of the maximum RFU/s rate proportional to product conversion rate was observed) using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Cell viability assay

The N/TERT keratinocyte [24] cell line was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM:F12, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 1% (v/v) penicillin-streptomycin, and 1× RMplus supplement [25] under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2, and 85% humidity). For the cell viability assay, cells were seeded at 4,000 cells/well in 100 µL medium and incubated overnight under standard conditions. Snake venoms were dissolved at a concentration of 10 mg/mL and then 2-fold diluted in 8 dilution steps in sterile PBS. The venom dilutions were then further diluted 1:6 in medium to the maximum concentration of 1 mg/mL and added to each well followed by a 24-hour incubation. Thereafter, the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay [26] was used to analyze the cytotoxicity of the 26 snake venoms. The assay was performed in triplicates, with no venom as negative control (maximum viability of the cells). IC50 values (the venom concentration inducing 50% loss of cell viability) were determined using nonlinear fitting with the dose–response inhibition equation on the venom dose curves analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Thromboelastography assay

Thromboelastography (TEG) was run for all viperid venoms (Bitis arietans, Bitis gabonica, Bitis nasicornis, Bitis rhinoceros, Cerastes cerastes, Echis leucogaster, Echis ocellatus, and Echis pyramidum) according to a protocol adapted from Seneci et al. [27] using a TEG 5000 thromboelastogram (Haemonetics, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). Solutions of 72 µL 25 mM CaCl2, 72 µL 0.25 mM phospholipids (Rossix, Mölndal, Sweden, catalog no. #PL052), 20 µL Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM Tris + 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), and 7 µL crude venom at 1 or 0.1 mg/mL in PBS (final concentration of ∼20 µg/mL and ∼2 µg/mL, respectively) were mixed in TEG disposable cups (Haemonetics). Last, 189 µL of citrated human plasma was added, and the samples were immediately run for at least 30 minutes. Negative controls were run by replacing venom with 7 µL PBS. TEG traces (3 replicates per venom concentration per species) were exported as TIFF files and processed in Adobe Photoshop 2022 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA).

Results and Discussion

Venom composition

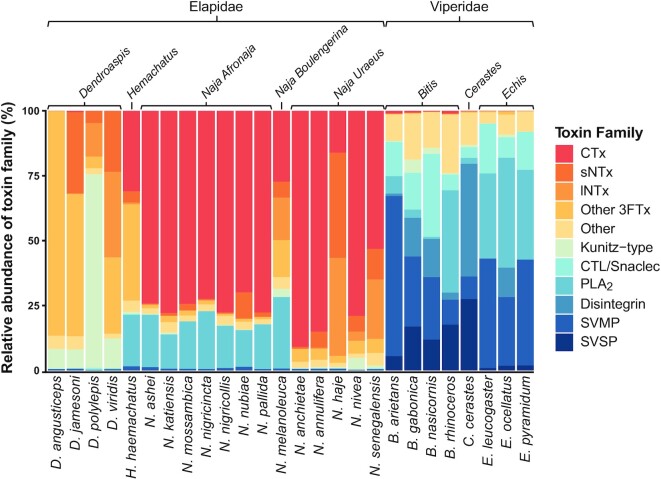

The venom proteomes of the 26 medically most important elapids and vipers from sub-Saharan Africa (Table 2) were determined using a bottom-up proteomics approach, involving the enzymatic digestion of whole venoms, separation and analysis by LC-MS/MS, assignment of the identified proteins to their respective protein families, and calculation of protein family abundances as a percentage of total identified proteins (mol/mol) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). In addition, the RP-HPLC chromatograms of the venoms are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

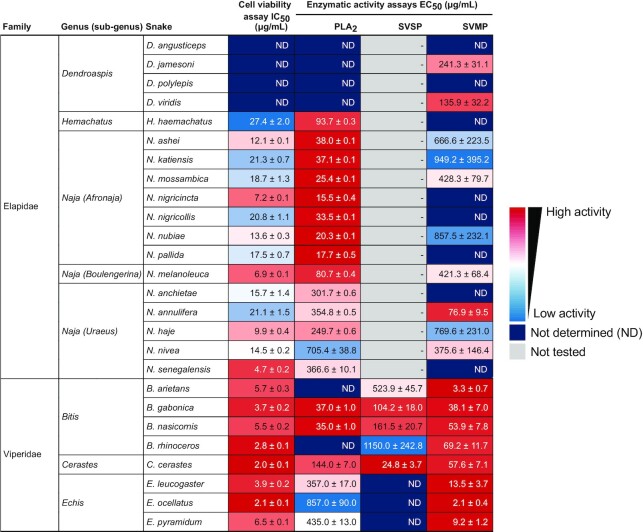

Table 2:

Functional in vitro activities of whole venoms from the 26 medically most relevant elapids and vipers in sub-Saharan Africa. Color scales indicate the IC50 and EC50 values. ND, not determined (response curves did not reach saturation); -, not tested.

|

Figure 1:

Composition of the whole venoms of the 26 medically most important elapids and vipers from sub-Saharan Africa. Toxins are grouped according to protein families and expressed as a percentage of total identified proteins (mol/mol). SVMP disintegrins have been classed as SVMPs, while non-SVMP disintegrins have been classed as disintegrins (as per UniProt definitions). CTL, C-type lectin; CTx, cytotoxin; lNTx, long neurotoxin; PLA2, phospholipase A2; sNTx, short neurotoxin; SVMP, snake venom metalloproteinase; SVSP, snake venom serine proteinase; 3FTx, 3-finger toxin.

Elapidae

The elapids included in this study belong to the genera Naja,Hemachatus, or Dendroaspis (Table 2). Of these, the true cobra lineage (Naja sp.) is by far the most widespread and diverse group throughout the African continent. To reflect their evolutionary and ecological diversity, African true cobras can be further divided into the 3 subgenera Afronaja, Boulengerina, and Uraeus [28].

The subgenus Afronaja includes all African spitting cobras (Naja ashei, Naja katiensis, Naja mossambica, Naja nigricincta, Naja nigricollis, Naja nubiae, and Naja pallida), with representative species found from Egypt (N. nubiae) to South Africa (N. mossambica and N. nigricincta) [29]. Despite the widespread distribution and different habitat preferences of Afronaja species, their toxin arsenal is remarkably conserved both inter- and intraspecifically [29]. In terms of protein abundance, the proteomic analysis shows that the bulk of their venom consists of 3FTxs (∼79%; of which 75% are CTxs) and PLA2s (∼17%), which is in accordance with previous studies [29, 30]. Notably, N. nubiae diverges from the general Afronaja venom profile and contains a considerable amount of short neurotoxins (sNTxs, ∼10%). Envenomings by N. nubiae therefore often result in both cytotoxic and neurotoxic clinical manifestations [30] compared to the mostly cytotoxic manifestations seen in envenomings caused by the rest of Afronaja species.

The only member of the subgenus Boulengerina included in this study was the forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca) [31], native to the forests and savannahs of central Africa, where it feeds on reptiles, amphibians, birds, small mammals, and even fish [32, 33]. Its venom was shown to have a high content of 3FTxs (∼64%), of which most were CTxs (∼27%), and also a considerable amount of PLA2s (∼28%), which is in agreement with a previous study [19]. Additionally, the venom contained a substantial proportion of long neurotoxins (lNTxs; ∼16%), the fourth highest among all snakes in this study, which could explain the neurotoxic manifestations reported after envenoming [34]. One toxin family in which the abundance differed from an earlier study was the SVMPs, where Lauridsen et al. [19] reported an abundance of 9.7%, whereas we only found 0.7%. Plausible explanations for this discrepancy could be a combination of variation between venom batches as a consequence of intraspecific venom variability, differences in the units used to quantify relative protein abundance (mol/mol in this study vs. wt% in Lauridsen et al. [19]), and/or the use of different proteomic methods (no decomplexing step prior to mass spectrometry in this study). Notably, the venom profile of N. melanoleuca differed from the other 2 Naja subgenera, containing less CTxs than Afronaja and more PLA2s than Uraeus.

The Uraeus subgenus (Naja anchietae, Naja annulifera, Naja haje, Naja nivea, and Naja senegalensis) consists of species with predominantly neurotoxic effects [34]. Like Afronaja, this lineage is widespread across the continent from Morocco (N. haje) to South Africa (N. anchietae, N. annulifera, and N. nivea) and has a highly diverse diet, which includes amphibians, reptiles, birds, and other snakes [35]. The venoms in this subgenus were predominantly composed of 3FTx (∼95%), most of which were CTxs as in the Afronaja subgenus, despite the mainly neurotoxic characteristics of Uraeus envenomings. This was not the case for N. haje, which contained mainly sNTxs (40%), lNTxs (38%), and CTxs (16%), although a previous study has reported a higher abundance of CTxs [36]. N. senegalensis also contained significant amounts of sNTxs (12%) and lNTxs (23%). Moreover, all Uraeus species except N. anchietae contained some neurotoxins (at least ∼6%), in line with the neurotoxic clinical manifestations associated with envenomings caused by these snakes. For snakes where proteomics data were available, our data corroborate the previously reported findings for N. senegalensis [37] and N. nivea [38]. For N. annulifera [39], a previous study reported an abundance 11.18% SVMPs, while our data showed only 0.6%, which, as mentioned previously, could be due to intraspecific venom variability and/or different methods for proteomics and quantification. In contrast to the other Naja species, Uraeus cobras all showed very low levels of PLA2s (∼0.15%), which were up until recently thought to be almost ubiquitous in snake venoms [40]. Of note, the proteomic venom composition for N. anchietae is presented here for the first time, strengthening a previous theory that low levels of PLA2s are a feature of all snakes within the Uraeus subgenus [37].

The rinkhals (Hemachatus haemachatus) is a spitting elapid classified in their own monotypic genus despite greatly resembling true cobras in morphology and general biology. This species is native to southeastern Africa, where it can be found in several ecosystems (e.g., savannah, woodland, and shrubland) and is known to prey mainly, although not exclusively, on amphibians [35]. According to our proteomic data, its venom composition is similar to those of the Afronaja, spitting cobras, which convergently evolved the ability to spit venom. In fact, H. haemachatus venom was shown to have a high content of 3FTxs (∼73%) and PLA2s (∼20%). Of the 3FTxs identified, the most abundant were CTxs or CTx homologs, with a small amount of sNTxs. This correlates with the cytotoxic and neurotoxic clinical manifestations of H. haemachatus envenomings [41]. The predominance of 3FTxs and PLA2s in this species is in line with a previous study by Sánchez et al. [8]. However, there are some minor discrepancies, as this previous study detected a larger amount of SVMPs (7% vs. 1.4%).

All 4 members of the Dendroaspis genus (mambas) were included in this study, namely, Dendroaspis angusticeps, Dendroaspis polylepis, Dendroaspis jamesoni, and Dendroaspis viridis. Widespread throughout the African continent, these species constitute one of the few predominately arboreal elapid lineages worldwide, cruising through the canopy of rainforest and woodland regions [42, 43]. As an exception, D. polylepis is often (but not always) more ground-dwelling than its congeners, being commonly found in open savannas and rocky hills [44, 45]. Overall, mambas mainly prey on birds and small mammals such as rodents and bats [42, 46], although their diet and ecology are poorly known.

Signature components of mamba venoms are the presynaptic neurotoxins called dendrotoxins, which belong to the Kunitz-type protease inhibitor family [12, 13]. Dendrotoxins are especially abundant in D. polylepis venom, where Kunitz-type protease inhibitors account for 75% of the venom proteins, as shown in this and previous studies [18, 47]. Conversely, D. angusticeps venom mainly consists of 3FTxs (87%; mainly short-chain aminergic and orphan group toxins), which is once again in accordance with previous findings [42]. The venoms of D. jamesoni and D. viridis are very similar when comparing the abundance of Kunitz-type protease inhibitors, sNTx, and other 3FTxs (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1), but different in terms of lNTx abundance (0.2% and 33%, respectively). Notably, our results are also in agreement with a recent study on venom gland transcriptomics for all 4 Dendroaspis species [17], indicating a general pattern of matching abundance profiles between venom transcriptome and proteome in mambas.

Viperidae

The Viperidae family is represented by the genera Bitis, Cerastes, and Echis in this study. Of these, Bitis is the most geographically widespread and taxonomically diverse viperid genus in Africa, with 18 currently recognized species (commonly referred to as African adders) found from Morocco to South Africa [43]. More specifically, B. rhinoceros is found in western Africa from Guinea to Togo, while B. gabonica and B. nasicornis occur from Nigeria to central, eastern, and southern Africa [2]. Last, B. arietans occurs across open woodland, grassland, and semiarid habitats throughout sub-Saharan Africa, southern Arabia, and Morocco [48]. Large-sized African adders like those included in this study are mostly generalist predators feeding on small mammals, birds, lizards, and occasionally toads [49, 50].

The venom compositions of B. gabonica and B. nasicornis are rather similar and show a high abundance of SVMPs (27% and 24%), SVSPs (17% and 12%), disintegrins (15%), and C-type lectins (CTLs)/snaclecs (14% and 32%). SVMPs dominate the venom of B. arietans (62%), whereas B. rhinoceros venom is particularly rich in PLA2s (39%) and SVSPs (18%). All these 4 species have been analyzed previously by Calvete et al. [51], and overall, our data correlate relatively well with this previous study with some variations observed regarding PLA2s (B. gabonica, B. nasicornis, and B. rhinoceros), disintegrins (B. arietans, B. gabonica, and B. nasicornis), SVMPs (B. rhinoceros), and CTLs (B. nasicornis) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). This discrepancy can be due to several reasons, such as using different methods to generate and analyze the data, as well as intraspecific variation in venom composition [52]. Furthermore, the complexity of some snake venom components (e.g., SVMPs exist in a size range from 20 to 100 kDa [53]) may lead to inconsistencies between studies. This emphasizes the importance of using the same proteomic approach for cataloguing venom composition of different snakes to enable comparison. Large amounts of rhinocerase 2, a SVSP homolog that contains a H57R mutation [54], was found in the venom of B. rhinoceros. Interestingly, this H57R mutation was also found in peptides from B. gabonica and B. nasicornis, yet in smaller amounts. Such SVSP homologs have previously been detected in B. gabonica [55], but this is the first time they have been found in B. nasicornis.

The only member of the Cerastes genus included in this study is the Saharan horned viper (Cerastes cerastes). This species is distributed throughout North Africa and further eastward as far as southwestern Israel and southwestern Saudi Arabia [56]. Like many other viper lineages, C. cerastes is an ambush predator, relying on camouflage to lunge at small rodents and lizards by surprise [57]. Our proteomics analysis of C. cerastes venom shows a high abundance of SVSPs (27%) as opposed to a relatively low abundance of CTLs (4%), which is in agreement with other studies [58–60] (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). On the other hand, the largest discrepancy compared to previous reports is observed for SVMPs, which were found to only constitute 8.6% of venom proteins in this study compared to 30–60% reported in literature, and disintegrins, which were found to constitute 43% of venom proteins in this study compared to approximately 10% previously reported in literature [58–60]. It is important to note that some SVMPs contain disintegrin (P-II class) or disintegrin-like (P-III class) domains [53], and therefore, mismapping of the peptides is possible but unlikely in this particular case since all such peptides mapped exactly to known C. cerastes disintegrins in the UniProt database.

The final Viperidae genus included in this study is Echis. The family members included are E. ocellatus, E. pyramidum, and E. leucogaster, of which no proteomic data have been reported previously for the latter. E. ocellatus and E. pyramidum are distributed throughout northern Africa, while E. leucogaster occurs in West Africa, isolated areas of the western Sahara, and throughout Algeria [61]. The diet of Echis snakes is widely varied, including invertebrates, such as scorpions and centipedes, small mammals, birds, lizards, and amphibians [62]. Our proteomics data show that the venom of E. pyramidum and E. leucogaster mainly consists of SVMPs with abundances of ∼41% and ∼42%, respectively. In contrast, E. ocellatus mainly consists of PLA2s with an abundance of ∼42%, followed by ∼26% SVMPs (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). This differs from previous studies, where SVMPs were also reported as the major component of E. ocellatus venom with abundances of ∼70% [63, 64]. Again, different methods used to analyze the venom composition and the origin of the snakes milked to obtain the venoms may be underlying reasons for the observed differences. SVSPs of Echis venom comprise less than 2% of the whole venom (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1), which is in accordance with previous reports [63, 64]. In agreement with a previous study showing that the genetic variability between E. pyramidum and E. leucogaster is very low [65], our proteomics data show that the venom composition of E. leucogaster is quite similar to that of E. pyramidum. Strikingly, the amount of disintegrins was found to be 11% for E. ocellatus and less than 0.01% for E. pyramidum and E. leucogaster (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). Extensive, likely diet-driven, interspecific venom variation has been documented in Echis representatives at the transcriptome and proteome levels [63] and in functional toxicity studies [66–68]. It is plausible that this interspecific variation can explain the differences between our results and previous analyses of E. pyramidum and E. ocellatus venoms.

In vitro functional characterization of whole venoms

To evaluate and compare functional activities of sub-Saharan Africa's 26 medically most relevant elapid and viper venoms, we determined the concentrations of snake venom resulting in 50% product conversion at a fixed substrate concentration (EC50 values) in PLA2, SVSP, and SVMP enzymatic activity assays, as well as the concentrations of snake venom reducing the cell viability by 50% (IC50 values) in a cell viability assay. Lower EC50 or IC50 values indicate more potent activity of the analyzed toxins in the whole venom.

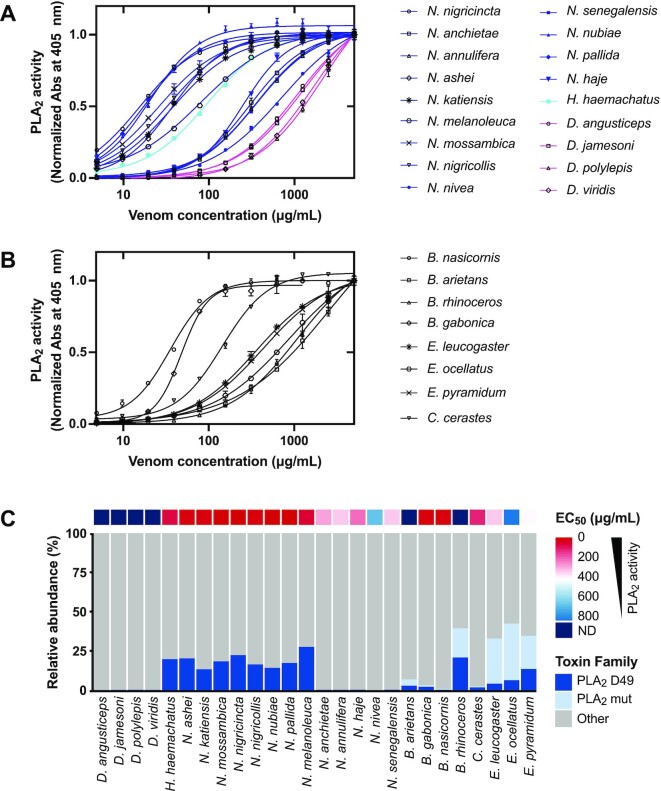

PLA2 enzymatic activity

Secreted PLA2s are one of the major components of many animal venoms. These 13- to 15-kDa enzymes need Ca2+ ions to catalyze the hydrolysis of phospholipids [69]. However, it is noteworthy that some PLA2s have lost their enzymatic activity during evolution [70]. In the noncatalytic PLA2s, the catalytic residue D49 is mutated to another amino acid (e.g., lysine, serine, asparagine, glutamine, or arginine), resulting in a conformational change of the Ca2+ binding loop that prevents the reaction by hindering Ca2+ coordination, which is essential for catalysis [71, 72]. Despite sharing a 40–99% amino acid sequence identity and highly conserved 3-dimensional structures, snake venom PLA2s display a wide variety of pharmacologic activities, including neurotoxic, myotoxic, cytotoxic, anticoagulant, and hemolytic effects [73].

Among the 18 snake species of the Elapidae family included in this study, the subgenus Afronaja shows the highest PLA2 activity with EC50 values of 15–38 µg/mL (Fig. 2A, Table 2). The subgenus Boulengerina and genus Hemachatus have moderate PLA2 activity, with EC50 values of 80–90 µg/mL, while the subgenus Uraeus exhibits low PLA2 activity with EC50 values above 200 µg/mL. Finally, Dendroaspis venoms display the weakest PLA2 activity (EC50 values over 1 mg/mL), which is in agreement with previous findings [18, 74]. The PLA2 activity of elapid snake venoms can therefore be ranked in the following order: Afronaja > Boulengerina > Hemachatus > Uraeus > Dendroaspis. This is in agreement with a previous publication on PLA2 activity of the 3 Naja subgenera [40] and correlates to the relative abundance of PLA2s in our proteomics data, except for N. melanoleuca, which exhibits the highest PLA2 abundance among the elapids but slightly lower activity than the 7 snakes from the Afronaja subgenus (Fig. 2A, Table 2).

Figure 2:

PLA2 enzymatic activity of whole venoms of elapids (A) and vipers (B) at different venom concentrations. Absorbances at 405 nm were normalized by subtracting values of the negative control (absence of venom). Error bars: SD from 2 independent measurements. (C) Relative abundance of enzymatically active PLA2s (D49) and enzymatically inactive PLA2s (mut) in 26 sub-Saharan snake venoms. A heatmap displaying EC50 values for each snake venom is plotted above the corresponding abundance.

Within the 8 snakes from the Viperidae family, B. gabonica and B. nasicornis show the lowest EC50 values for PLA2 activity (∼40 µg/mL; Fig. 2B, Table 2), which is comparable to that of the subgenus Afronaja from the Elapidae family. The high PLA2 activity of B. gabonica and B. nasicornis venom is in agreement with a previous publication [51] but differs from our proteomics data, which show a low PLA2 abundance (Fig. 2C). Notably, 2 other species from the Bitis genus, B. arietans and B. rhinoceros, show weak PLA2 activity, likely due to high abundances of mutated PLA2s in their venoms (Fig. 2C). Similarly, the 3 species from the Echis genus exhibit high relative abundances of PLA2 but weak enzymatic activity, which can be explained by high amounts of noncatalytic PLA2s found in Echis venoms (Fig. 2C). This result is consistent with a previous study reporting high myotoxic activity, but low enzymatic activity, of S49 PLA2s in E. ocellatus and E. pyramidum venoms [75]. The Cerastes genus displays the second highest PLA2 activity, with an EC50 value of 144 µg/mL. In general, our data demonstrate that there is a high correlation between PLA2 activity and PLA2 relative abundance for most of the viperid snake venoms.

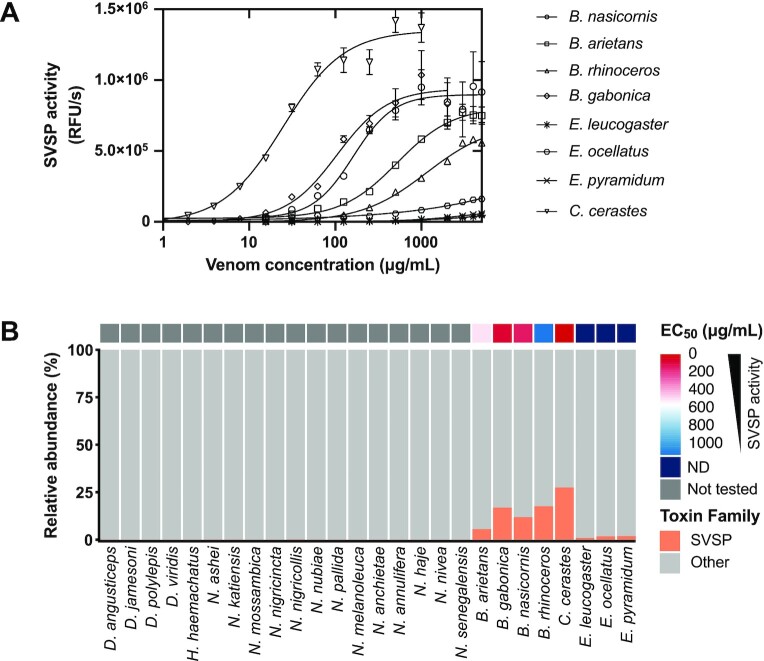

SVSP enzymatic activity

SVSPs are members of the S1 peptidase family, which catalyze the cleavage of covalent peptide bonds of proteins via the conserved catalytic triad H57–D102–S195, in which serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the active site [76]. These 26- to 67-kDa enzymes affect the coagulation cascade, as well as the fibrinolytic and kallikrein–kinin systems, and cause hemostatic imbalances in victims [77]. In this relation, SVSPs can be classified as procoagulant, anticoagulant, platelet aggregating, or activator of fibrinolysis [78].

Our proteomic data show negligible amounts of SVSPs in the elapid venoms (Fig. 3B), and therefore, EC50 values of SVSPs were determined only for viperid venoms (Fig. 3A, Table 2). C. cerastes shows the lowest EC50 value (25 µg/mL), which correlates with the high SVSP abundance in its venom (27.5%, Fig. 3B). Within the genus Bitis, the SVSP activity of B. gabonica and B. nasicornis is moderate, with EC50 values of ∼100 µg/mL, whereas B. arietans and B. rhinoceros demonstrate weak SVSP activity with EC50 values between 500 and 1,000 µg/mL (Fig. 3A, Table 2). Although B. rhinoceros exhibits the second highest SVSP abundance among the 8 vipers included in this study, its EC50 value is in the high range. This could be because, as mentioned before, an SVSP homolog with a catalytic site mutation [ 54] was found in our proteomic analysis. Finally, the genus Echis shows the weakest SVSP activity, with EC50 values above 1 mg/mL, which agrees with their low SVSP abundance (below 2%, Fig. 3B).

Figure 3:

(A) SVSP enzymatic activity of viper whole venoms at different venom concentrations. RFU, relative fluorescence unit. Error bars: SD from 2 independent measurements. (B) Relative abundance of SVSPs in 26 sub-Saharan snake venoms. A heatmap displaying EC50 values for each snake venom is plotted above the corresponding abundance.

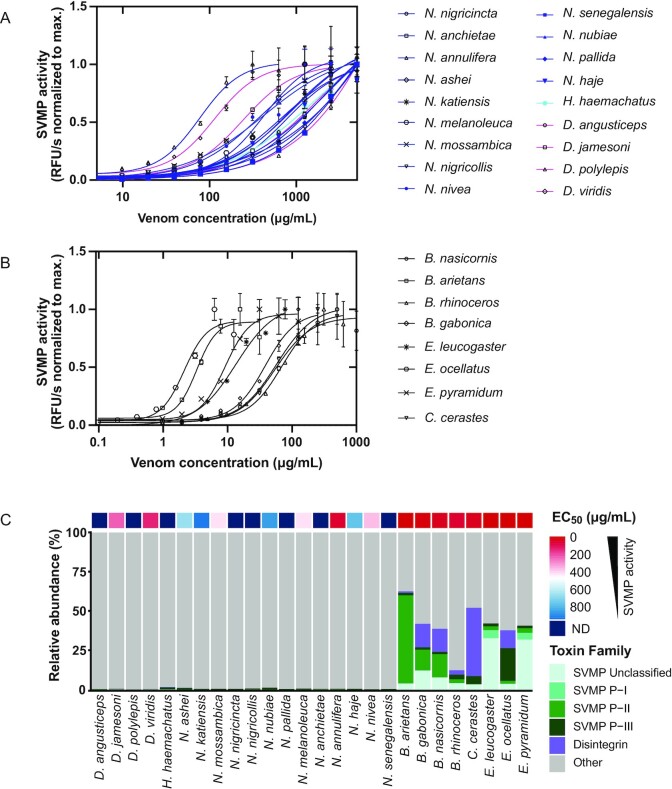

SVMP enzymatic activity

The Zn2+-dependent SVMPs are one of the most abundant toxins in viperid venoms [5] mainly responsible for inducing systemic hemorrhage after envenomings with these snakes. There are 3 major classes of SVMPs: P-I contains only a metalloproteinase (M) domain, P-II contains an M domain and a disintegrin (D) domain, and the most complex P-III class is composed of an M domain, a D domain, and a cysteine-rich (C) domain.

All elapids show high EC50 values of at least 100 µg/mL, except N. annulifera, with a value of 80 µg/mL. This is in agreement with previously published data showing that SVMP is the second most abundant protein family in N. annulifera venom after 3FTxs [39]. SVMPs in the Dendroaspis species have a low abundance but a high activity in D. jamesoni and D. viridis (EC50 values of 241 and 136 µg/mL, respectively). This is in agreement with an earlier study in which SVMP-dependent anticoagulant activity was observed in Dendroaspis species despite the low SVMP abundance [79]. Among the 8 viperids included in this study, B. arietans show the lowest EC50 value (3.3 µg/mL), while the 3 venoms from the Echis subgenus show high amounts of SVMPs (Fig. 4C), with EC50 values between ∼2 and 14 µg/mL (Fig. 4B, Table 2). B. arietans has an EC50 value in the same range as the Echis venom, whereas all other Bitis species have EC50 values around 40–50 µg/mL.

Figure 4:

SVMP enzymatic activity of the whole venoms of elapids (A) and vipers (B) at different venom concentrations. RFU, relative fluorescence unit. Error bars: SD from 2 independent measurements. (C) Relative abundance of SVMP subfamilies in 26 sub-Saharan snake venoms. SVMP disintegrins are included in the SVMP category. A heatmap displaying EC50 values for each snake venom is plotted above the corresponding abundance.

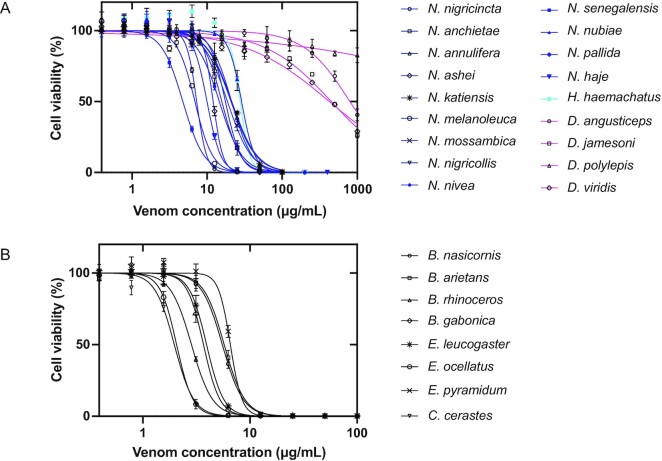

Cell viability

CTxs and PLA2s are known to, either individually or synergistically, interfere with and disrupt the integrity of cellular membranes, leading to irreversible damage and cell death [25, 80]. In snake venoms, cytotoxins are mainly found in the genera Naja and Hemachatus of the Elapidae family [8], while PLA2s are found in all venomous snake families, including Elapidae and Viperidae [81]. Therefore, the cytotoxicity of all elapid and viperid venoms included in this study was evaluated using an immortalized human keratinocyte cell line, which has been reported to be sensitive to snake venom cytotoxins and PLA2s [25].

Treatment of the cells with venoms resulted in a concentration-dependent inhibition of cell viability (Fig. 5). As expected, the viper venoms were more potent (IC50 2.0–6.5 µg/mL) than venoms from the elapids (IC50 4.7 to >100 µg/mL). Among the Elapidae, 4 species from the Naja genus (i.e., N. senegalensis, N. melanoleuca, N. nigricincta, and N. haje) show IC50 values close to those of the Viperidae (below 10 µg/mL), while the Dendroaspis genus demonstrates IC50 values above 100 µg/mL. These results are in alignment with a high abundance of cytotoxins in the Naja genus and PLA2s in the Viperidae family, as well as a very low abundance of these 2 toxin families in the Dendroaspis genus.

Figure 5:

Cell viability of the N/TERT keratinocyte cell line after addition of different concentrations of whole venoms of elapids (A) and vipers (B). The negative control value (without venom) was set to 100%. Error bars: SD from 2 independent measurements.

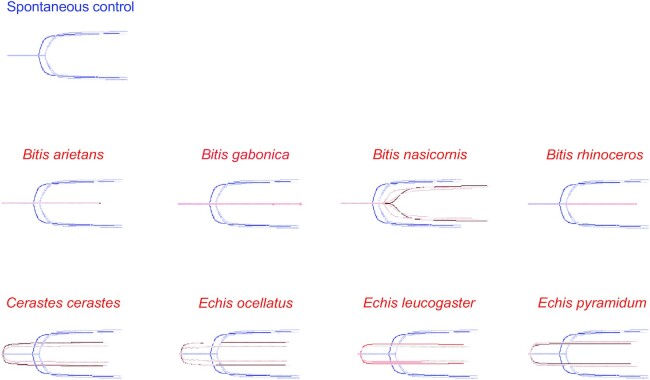

Thromboelastography

The blood coagulation cascade is a primary target for many snake venom toxins due to its pivotal role in maintaining homeostasis, and most major venomous snake families possess toxins in their venoms that can interfere with this system. This is particularly evident in (although not exclusive to) vipers, whose venoms are generally dominated by proteins that cause coagulopathies (e.g., SVMPs, SVSPs, and disintegrins) [82, 83]. Thus, we assessed the coagulotoxic effects of the venoms of all viper species included in this study via TEG by incubating whole venom with human plasma and physiologic cofactors of coagulation (i.e., calcium and phospholipids).

All venoms were tested and presented similar activity, at ∼2 µg/mL and ∼20 µg/mL, except B. arietans, which showed inconclusive results at ∼2 µg/mL. Both anti- and procoagulant effects were observed on a broadly genus-specific basis. More specifically, venoms from all Bitis species, except B. nasicornis, displayed an overall strong anticoagulant activity, with no visible clot formation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6:

Overlaid thromboelastography traces showing the ability of the different venoms (2 µg/mL for all species except B. arietans, 20 µg/mL) to clot plasma relative to a spontaneous control in 1 hour. Time is plotted horizontally and amplitude (clotting strength) is plotted vertically. Eight representatives of the Viperidae family, which possess procoagulant (C. cerastes, E. leucogaster, E. ocellatus, and E. pyramidum) and anticoagulant (B. arietans, B. gabonica,B. nasicornis, and B. rhinoceros) venom, are depicted. Blue traces represent spontaneous clot controls and red traces represent samples (n = 3).

Unlike Bitis, C. cerastes venom produced a detectable, stable clot almost immediately after assay initiation (Fig. 6). Interestingly, other researchers have reported that the venom of this species exerts both pro- and anticoagulant effects in a concentration-dependent manner, whereby low venom concentrations (≤200 µg/mL), as used in our study, enhanced blood clotting, in agreement with our observations, while higher amounts disrupted coagulation [84].

Last, an even stronger procoagulant activity than seen for C. cerastes was observed for the 3 Echis representatives included in this study (Fig. 6). This is not surprising, as a signature trait of most Echis species is the presence of exceptionally potent prothrombin activators (all part of the SVMP family) in their venoms, which results in uncontrolled formation of fibrin clots due to excessive production of thrombin [85–88]. This agrees with our proteomic data, in which Echis venoms show high amounts of SVMPs for all 3 species.

Conclusion

In this study, we systematically analyzed and compared the proteomics and in vitro functional activity of multiple snake venoms and provide toxicovenomic profiles of 26 of sub-Saharan Africa's medically most important elapids and vipers. To the best of our knowledge, the venom composition of N. anchietae and E. leucogaster is presented here for the first time. Overall, our data show that the elapid venoms contained large amounts of neurotoxic and cytotoxic 3FTxs and PLA2s, whereas the viper venoms were dominated by hemotoxic and/or cytotoxic PLA2s, SVMPs, and SVSPs, as expected based on clinical manifestations observed for elapid and viperid envenoming [5].

The high-throughput, label-free, quantitative proteomics approach presented here comes with some limitations. During mass spectrometry, proteins are identified through mapping of the peptide sequence to a database. It is important to keep in mind that peptides from highly similar isoforms may be difficult to map back to their parent proteins, resulting in false positives (e.g., detection of a disintegrin instead of an SVMP). Additionally, the lack of a comprehensive database may thus result in false negatives; if the sequence of a protein is not present in the database, it cannot be detected. In the UniProt reference database used here, there was a noticeable lack of SVMPs from the 26 snakes, apart from B. gabonica,E. ocellatus, and E. pyramidum leakeyi (a subspecies of E. pyramidum), where transcriptomic data were available. The NCBI protein database, a possible alternative database, had the same issue. Importantly, by including not only manually reviewed Swiss-Prot proteins in the UniProt database, we increased the number of SVMPs being identified. Interestingly, low amounts of SVMPs have been observed in previous studies using similar workflows [20]. Together, this indicates a clear need for further work to characterize SVMPs from medically relevant sub-Saharan African snake species.

With respect to functional activity, the subgenus Afronaja, together with B. gabonica and B. nasicornis, showed the highest enzymatic PLA2 activity, which highlights the importance of catalytic PLA2s in relation to the clinical manifestations observed after envenoming with these snakes, such as hemolytic and anticoagulant effects [89, 90]. When comparing the enzymatic SVSP activity among the vipers, the abundance of active SVSPs in the venoms showed a good correlation with activity; for the outlier B. rhinoceros, the high abundance but low activity of SVSPs can be explained by the high proportion of catalytically inactive SVSP homologs in its venom. All viper venoms were shown to possess high SVMP activity with low EC50 values, 10–100 times higher activity than most of the elapid venoms, where only N. annulifera venom showed activity in the same range as the vipers. Given that N. annulifera has been shown in a previous study to possess a substantial amount of SVMP in its venom [39], higher than many other cobra species, this is not too surprising.

The coagulotoxic effect of the viper venoms included in this study was assessed by TEG, showing a procoagulant effect for venoms from C. cerastes and the genus Echis. In contrast, all Bitis species showed strong anticoagulant activity except B. nasicornis, which also showed an anticoagulant activity but to a lesser extent. Finally, cell viability of a keratinocyte cell line was inhibited by addition of snake venoms from all snake species, except the ones from the genus of Dendroaspis. This is not surprising, given that Dendroaspis venoms are known to be highly neurotoxic, cause very little tissue damage, and display very low enzymatic activities [18, 74].

Some inconsistencies were observed between the relative abundance of certain toxin families and whole venom activity in their respective in vitro functional assays. For example, our data show that the venoms of N. annulifera, D. viridis, and D. jamesoni had high SVMP activity despite low abundance of such proteins. When it comes to in vitro assays for characterizing toxin functions, a limitation of the present study is the lack of assays to assess the activity of neurotoxins, as several species included herein (e.g., mambas and most Uraeus cobras) possess predominately neurotoxic venoms [18, 34, 74].

Overall, this study provides a foundation for further studies on snake biology and evolution, for which we recommend an integrated approach combining genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to provide information on gene expression and other molecular mechanisms linked to phenotypic diversity [1]. Moreover, the toxicovenomic profiles elucidated in this study may aid in the development of effective antivenoms through better understanding of the behavior of snake venoms and their roles as drug targets.

Additional Files

Supplementary Fig. S1. RP-HPLC chromatograms of the whole venoms of 26 sub-Saharan snakes.

Supplementary Table S1. Composition of the whole venoms of 26 sub-Saharan snakes.

Michael Hogan -- 8/30/2022 Reviewed

Michael Hogan -- 10/13/2022 Reviewed

Benjamin-Florian Hempel -- 9/13/2022 Reviewed

Data Accessibility

The data sets supporting the results of this article, including results from the in vitro functional activity assays, are available in the GigaScience GigaDB repository [92]. Results from the proteomics characterizations have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [91] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD036161.

Abbreviations

CTLs: C-type lectins; CTxs: cytotoxins; FA: formic acid; LC: liquid chromatography; lNTxs: long neurotoxins; MS: mass spectrometry; NOB: 4-nitro-3-(octanoyloxy)benzoic acid; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline; PLA2s: phospholipase A2s; RFU/s: relative fluorescence units per second; RP-HPLC: reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography; sNTxs: short neurotoxins; SVMPs: snake venom metalloproteinases; SVSPs: snake venom serine proteinases; 3FTxs: 3-finger toxins; TEG: thromboelastography; TFA: trifluoroacetic acid.

Competing Interests

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from Wellcome (221702/z/20/z).

Authors’ Contributions

G.T.T.N., C.O.B., A.H.L., and A.L. conceived the study. G.T.T.N., C.O.B., Y.W., L.S., A.G.C., and I.C.P. performed laboratory experiments and analyzed the data. A.H.L. and A.L. supervised the study. G.T.T.N., C.O.B., Y.W., L.S., A.G.C., S.A., A.H.L., and A.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Lars Winther and Peter Ådal Nielsen (Tissue-Link) for granting us use of the TEG 5000 thromboelastogram and supplying us with reagents. We also thank Dr. Christina N. Zdenek (School of Biological Sciences, the University of Queensland, Australia) for valuable advice in devising the TEG protocol. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed at the DTU Proteomics Core, Technical University of Denmark.

Contributor Information

Giang Thi Tuyet Nguyen, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

Carol O'Brien, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

Yessica Wouters, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

Lorenzo Seneci, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

Alex Gallissà-Calzado, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

Isabel Campos-Pinto, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

Shirin Ahmadi, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

Andreas H Laustsen, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

Anne Ljungars, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby, Denmark.

References

- 1. Rao W, Kalogeropoulos K, Allentoft ME, et al. The rise of genomics in snake venom research: recent advances and future perspectives. GigaScience. 2022;11:giac024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spawls S, Branch B. The dangerous snakes of Africa. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Shea M. Venomous snakes of the world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR, de Silva N, et al. The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008;5(11):e218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gutiérrez JM, Calvete JJ, Habib AG, et al. Snakebite envenoming. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Babo Martins S, Bolon I, Alcoba G, et al. Assessment of the effect of snakebite on health and socioeconomic factors using a One Health perspective in the Terai region of Nepal: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Global Health. 2022;10(3):e409–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harrison RA, Hargreaves A, Wagstaff SC, et al. Snake envenoming: a disease of poverty. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(12):e569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sánchez A, Segura Á, Pla D, et al. Comparative venomics and preclinical efficacy evaluation of a monospecific Hemachatus antivenom towards sub-Saharan Africa cobra venoms. J Proteomics. 2021;240:104196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adukauskienė D, Varanauskienė E, Adukauskaitė A. Venomous snakebites. Medicina (Mex). 2011;47(8):461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Méndez I, Gutiérrez JM, Angulo Y, et al. Comparative study of the cytolytic activity of snake venoms from African spitting cobras (Naja spp., Elapidae) and its neutralization by a polyspecific antivenom. Toxicon. 2011;58(6–7):558–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nirthanan S, Gwee MCE. Three-finger α-neurotoxins and the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, forty years on. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;94(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harvey AL. Twenty years of dendrotoxins. Toxicon. 2001;39(1):15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harvey AL, Anderson AJ. Dendrotoxins: snake toxins that block potassium channels and facilitate neurotransmitter release. Pharmacol Ther. 1985; 31(1–2):33–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gutiérrez J, Escalante T, Rucavado A, et al. A comprehensive view of the structural and functional alterations of extracellular matrix by snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs): novel perspectives on the pathophysiology of envenoming. Toxins. 2016;8(10):304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gutiérrez J. Snake venom metalloproteinases: their role in the pathogenesis of local tissue damage. Biochimie. 2000;82(9–10):841–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Serrano SMT. The long road of research on snake venom serine proteinases. Toxicon. 2013;62:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ainsworth S, Petras D, Engmark M, et al. The medical threat of mamba envenoming in sub-Saharan Africa revealed by genus-wide analysis of venom composition, toxicity and antivenomics profiling of available antivenoms. J Proteomics. 2018;172:173–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laustsen AH, Lomonte B, Lohse B, et al. Unveiling the nature of black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) venom through venomics and antivenom immunoprofiling: Identification of key toxin targets for antivenom development. J Proteomics. 2015;119:126–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lauridsen LP, Laustsen AH, Lomonte B, et al. Exploring the venom of the forest cobra snake: toxicovenomics and antivenom profiling of Naja melanoleuca. J Proteomics. 2017;150:98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Damm M, Hempel B-F, Süssmuth RD. Old World vipers—a review about snake venom proteomics of Viperinae and their variations. Toxins. 2021;13(6):427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wagstaff SC, Sanz L, Juárez P, et al. Combined snake venomics and venom gland transcriptomic analysis of the ocellated carpet viper, Echis ocellatus. J Proteomics. 2009;71(6):609–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calvete JJ. Proteomic tools against the neglected pathology of snake bite envenoming. Exp Rev Proteomics. 2011;8(6):739–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holzer M, Mackessy SP. An aqueous endpoint assay of snake venom phospholipase A2. Toxicon. 1996;34(10):1149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dickson MA, Hahn WC, Ino Y, et al. Human keratinocytes that express hTERT and also bypass a p16 INK4a -enforced mechanism that limits life span become immortal yet retain normal growth and differentiation characteristics. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(4):1436–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pucca MB, Ahmadi S, Cerni FA, et al. Unity makes strength: exploring intraspecies and interspecies toxin synergism between phospholipases A2 and cytotoxins. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Riss TL, Moravec RA, Niles AL. Cytotoxicity testing: measuring viable cells, dead cells, and detecting mechanism of cell death. In: Stoddart MJ, editor. Mammalian cell viability. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seneci L, Zdenek CN, Chowdhury A, et al. A clot twist: extreme variation in coagulotoxicity mechanisms in Mexican neotropical rattlesnake venoms. Front Immunol. 2021;12:612846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wallach V, Wüster W, Broadley DG. In praise of subgenera: taxonomic status of cobras of the genus Naja Laurenti (Serpentes: Elapidae). Zootaxa. 2009;2236(1):26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hus K, Buczkowicz J, Petrilla V. et al. First look at the venom of Naja ashei. Molecules. 2018;23(3):609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Petras D, Sanz L, Segura Á, et al. Snake venomics of African spitting cobras: toxin composition and assessment of congeneric cross-reactivity of the pan-African EchiTAb-Plus-ICP antivenom by antivenomics and neutralization approaches. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(3):1266–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wüster W, Chirio L, Trape J-F, et al. Integration of nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences and morphology reveals unexpected diversity in the forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca) species complex in Central and West Africa (Serpentes: Elapidae). Zootaxa. 2018;4455(1):68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luiselli L, Angelici FM, Akani GC. Comparative feeding strategies and dietary plasticity of the sympatric cobras Naja melanoleuca and Naja nigricollis in three diverging Afrotropical habitats. Canadian Journal of Zoology;80:92002. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luiselli L, Akani GC, Corti C, et al. Is sexual size dimorphism in relative head size correlated with intersexual dietary divergence in West African forest cobras, Naja melanoleuca?. CTOZ. 2002;71(4):141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization . Guidelines for the prevention and clinical management of snakebite in Africa. Brazzaville, Congo: World Health Organization; 2010, ISBN:9789290231684. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shine R, Branch WR, Webb JK, et al. Ecology of cobras from southern Africa. J Zool. 2007;272(2):183–93. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Malih I, Ahmad rusmili MR, Tee TY, et al. Proteomic analysis of Moroccan cobra Naja haje legionis venom using tandem mass spectrometry. J Proteomics. 2014;96:240–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wong KY, Tan KY, Tan NH, et al. A neurotoxic snake venom without phospholipase A2: proteomics and cross-neutralization of the venom from Senegalese Cobra, Naja senegalensis (Subgenus: Uraeus). Toxins. 2021;13(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kazandjian TD, Petras D, Robinson SD, et al. Convergent evolution of pain-inducing defensive venom components in spitting cobras. Science. 2021;371(6527):386–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tan KY, Wong KY, Tan NH, et al. Quantitative proteomics of Naja annulifera(sub-Saharan snouted cobra) venom and neutralization activities of two antivenoms in Africa. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;158:605–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tan C, Wong K, Tan N, et al. Distinctive distribution of secretory phospholipases A2 in the venoms of Afro-Asian cobras (subgenus: Naja, Afronaja, Boulengerina and Uraeus). Toxins. 2019;11(2):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blaylock R. The identification and syndromic management of snakebite in South Africa. South African Family Practice. 2005;47(9):48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Luiselli L, Angelici FM, Akani GC. Large elapids and arboreality: the ecology of Jameson's green mamba (Dendroaspis jamesoni) in an Afrotropical forested region. CTOZ. 2000;69(3):147–55. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shine R, Spawls S. An ecological analysis of snakes captured by C.J.P. Ionides in eastern Africa in the mid-1900s. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hakansson T, Madsen T. On the distribution of the black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) in West Africa. J Herpetol. 1983;17(2):186. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marais J. A complete guide to the snakes of southern Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maritz B, Barends JM, Mohamed R, et al. Repeated dietary shifts in elapid snakes (Squamata: Elapidae) revealed by ancestral state reconstruction. Biol J Linn Soc. 2021;134(4):975–86. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Petras D, Heiss P, Harrison RA, et al. Top-down venomics of the East African green mamba, Dendroaspis angusticeps, and the black mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis, highlight the complexity of their toxin arsenals. J Proteomics. 2016;146:148–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Barlow A, Wüster W, Kelly CMR, et al. Ancient habitat shifts and organismal diversification are decoupled in the African viper genus Bitis (Serpentes: Viperidae). J Biogeogr. 2019;46(6):1234–48. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Luiselli L, Akani GC. Diet of sympatric gaboon vipers (Bitis gabonica) and nose-horned vipers (Bitis nasicornis) in southern Nigeria. African J Herpetol. 2003;52(2):101–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Glaudas X, Kearney TC, Alexander GJ. Museum specimens bias measures of snake diet: a case study using the ambush-foraging puff adder (Bitis arietans). Herpetologica. 2017;73(2):121–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Calvete JJ, Escolano J, Sanz L. Snake venomics of Bitis species reveals large intragenus venom toxin composition variation: application to taxonomy of congeneric taxa. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(7):2732–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chippaux J-P, Williams V, White J. Snake venom variability: methods of study, results and interpretation. Toxicon. 1991;29(11):1279–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Olaoba OT, Karina dos Santos P, Selistre-de-Araujo HS, et al. Snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs): a structure-function update. Toxicon X. 2020;7:100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vaiyapuri S, Wagstaff SC, Harrison RA, et al. Evolutionary analysis of novel serine proteases in the venom gland transcriptome of Bitis gabonica rhinoceros. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Francischetti IMB, My-Pham V, Harrison J, et al. Bitis gabonica (Gaboon viper) snake venom gland: toward a catalog for the full-length transcripts (cDNA) and proteins. Gene. 2004;337:55–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schneemann M, Cathomas R, Laidlaw ST, et al. Life-threatening envenoming by the Saharan horned viper (Cerastes cerastes) causing micro-angiopathic haemolysis, coagulopathy and acute renal failure: clinical cases and review. QJM. 2004;97(11):717–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Young BA, Morain M. The use of ground-borne vibrations for prey localization in the Saharan sand vipers (Cerastes), Journal of Experimental Biology. 2002;205(5):661–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bazaa A, Marrakchi N, El Ayeb M, et al. Snake venomics: comparative analysis of the venom proteomes of the Tunisian snakes Cerastes cerastes, Cerastes vipera and Macrovipera lebetina. Proteomics. 2005;5(16):4223–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fahmi L, Makran B, Pla D, et al. Venomics and antivenomics profiles of North African Cerastes cerastes and C. vipera populations reveals a potentially important therapeutic weakness. J Proteomics. 2012;75(8):2442–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ozverel CS, Damm M, Hempel B-F, et al. Investigating the cytotoxic effects of the venom proteome of two species of the Viperidae family (Cerastes cerastes and Cryptelytrops purpureomaculatus) from various habitats. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2019;220:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wüster W, Golay P, Warrell DA. Synopsis of recent developments in venomous snake systematics. Toxicon. 1997;35(3):319–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Spawls S, Branch B. The dangerous snakes of Africa: natural history, species directory, venoms, and snakebite. Sanibel Island, FL: Ralph Curtis-Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wagstaff SC, Sanz L, Juárez P, et al. Combined snake venomics and venom gland transcriptomic analysis of the ocellated carpet viper, Echis ocellatus. J Proteomics. 2009;71(6):609–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Casewell NR, Harrison RA, Wüster W, et al. Comparative venom gland transcriptome surveys of the saw-scaled vipers (Viperidae: Echis) reveal substantial intra-family gene diversity and novel venom transcripts. BMC Genomics. 2009;10(1):564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Arnold N, Robinson M, Carranza S. A preliminary analysis of phylogenetic relationships and biogeography of the dangerously venomous carpet vipers, Echis (Squamata, Serpentes, Viperidae) based on mitochondrial DNA sequences. Amphib Reptilia. 2009;30(2):273–82. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Casewell NR, Wagstaff SC, Wüster W, et al. Medically important differences in snake venom composition are dictated by distinct postgenomic mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(25):9205–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Barlow A, Pook CE, Harrison RA, et al. Coevolution of diet and prey-specific venom activity supports the role of selection in snake venom evolution. Proc R Soc B. 2009;276(1666):2443–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Richards DP, Barlow A, Wüster W. Venom lethality and diet: differential responses of natural prey and model organisms to the venom of the saw-scaled vipers (Echis). Toxicon. 2012;59(1):110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Scott DL, White SP, Otwinowski Z et al. Interfacial catalysis: the mechanism of phospholipase A2. Science. 1990;250(4987):1541–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rouault M, Rash LD, Escoubas P et al. Neurotoxicity and other pharmacological activities of the snake venom phospholipase A2 OS2: the N-terminal region is more important than enzymatic activity. Biochemistry. 2006;45(18):5800–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Maraganore JM, Heinrikson RL. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(11):4797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wei J-F, Wei X, Chen Q-Y, et al. N49 phospholipase A2, a unique subgroup of snake venom group II phospholipase A2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760(3):462–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Manjunatha Kini R. Excitement ahead: structure, function and mechanism of snake venom phospholipase A2 enzymes. Toxicon. 2003;42(8):827–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lauridsen LP, Laustsen AH, Lomonte B, et al. Toxicovenomics and antivenom profiling of the eastern green mamba snake (Dendroaspis angusticeps). J Proteomics. 2016;136:248–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Conlon JM, Attoub S, Arafat H, et al. Cytotoxic activities of [Ser49]phospholipase A2 from the venom of the saw-scaled vipers Echis ocellatus, Echis pyramidum leakeyi, Echis carinatus sochureki, and Echis coloratus. Toxicon. 2013;71:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kang TS, Georgieva D, Genov N, et al. Enzymatic toxins from snake venom: structural characterization and mechanism of catalysis: Enzymatic toxins from snake venom. FEBS J. 2011;278(23):4544–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lee C-Y. Snake venoms. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Marsh N, Williams V. Practical applications of snake venom toxins in haemostasis. Toxicon. 2005;45(8):1171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nielsen VG, Wagner MT, Frank N. Mechanisms responsible for the anticoagulant properties of neurotoxic Dendroaspis venoms: a viscoelastic analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Gasanov SE. Snake venom cytotoxins, phospholipase A2s, and Zn2+-dependent metalloproteinases: mechanisms of action and pharmacological relevance. J Clinic Toxicol. 2014;4(1):1000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Xiao H, Pan H, Liao K, et al. Snake venom PLA2, a promising target for broad-spectrum antivenom drug development. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kini RM, Rao VS, Joseph JS. Procoagulant proteins from snake venoms. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2001;31(3–6):218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kini RM. Anticoagulant proteins from snake venoms: structure, function and mechanism. Biochem J. 2006;397(3):377–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Labib RS, Azab MH, Farag NW. Effects of Cerastes cerastes(Egyptian sand viper) and Cerastes vipera (Sahara sand viper) snake venoms on blood coagulation: Separation of coagulant and anticoagulant factors and their correlation with arginine esterase and protease activities. Toxicon. 1981;19(1):85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Rogalski A, Soerensen C, op den Brouw B, et al. Differential procoagulant effects of saw-scaled viper (Serpentes: Viperidae: Echis) snake venoms on human plasma and the narrow taxonomic ranges of antivenom efficacies. Toxicol Lett. 2017;280:159–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kornalik F, Blombäck B. Prothrombin activation induced by ecarin—a prothrombin converting enzyme from Echis carinatus venom. Thromb Res. 1975;6(1):53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yamada D, Sekiya F, Morita T. Isolation and characterization of carinactivase, a novel prothrombin activator in Echis carinatus venom with a unique catalytic mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(9):5200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yamada D, Morita T. Purification and characterization of a Ca2+-dependent prothrombin activator, multactivase, from the venom of Echis multisquamatus. J Biochem. 1997;122(5):991–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kini RM. Structure–function relationships and mechanism of anticoagulant phospholipase A2 enzymes from snake venoms. Toxicon. 2005;45(8):1147–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Youngman NJ, Walker A, Naude A, et al. Varespladib (LY315920) neutralises phospholipase A2 mediated prothrombinase-inhibition induced by Bitis snake venoms. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020; 236:108818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Perez-Riverol Y, Bai J, Bandla C, et al. The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D543–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nguyen GTT, O'Brien C, Wouters Y, et al. Supporting data for “High-throughput proteomics and in vitro functional characterization of the 26 medically most important elapids and vipers from sub-Saharan Africa” GigaScience Database. 2022. 10.5524/102333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Nguyen GTT, O'Brien C, Wouters Y, et al. Supporting data for “High-throughput proteomics and in vitro functional characterization of the 26 medically most important elapids and vipers from sub-Saharan Africa” GigaScience Database. 2022. 10.5524/102333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Michael Hogan -- 8/30/2022 Reviewed

Michael Hogan -- 10/13/2022 Reviewed

Benjamin-Florian Hempel -- 9/13/2022 Reviewed

Data Availability Statement

The data sets supporting the results of this article, including results from the in vitro functional activity assays, are available in the GigaScience GigaDB repository [92]. Results from the proteomics characterizations have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [91] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD036161.