Keywords: interlimb coordination, lateral hemisection, spinal cord, split-belt locomotion

Abstract

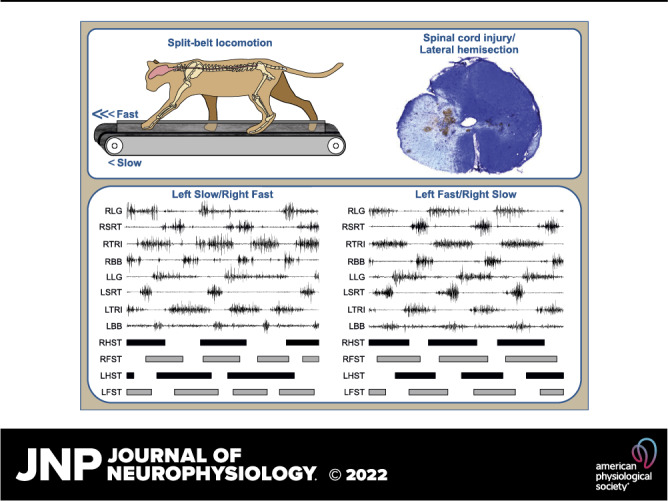

Most previous studies investigated the recovery of locomotion in animals and people with incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI) during relatively simple tasks (e.g., walking in a straight line on a horizontal surface or a treadmill). We know less about the recovery of locomotion after incomplete SCI in left-right asymmetric conditions, such as turning or stepping along circular trajectories. To investigate this, we collected kinematic and electromyography data during split-belt locomotion at different left-right speed differences before and after a right thoracic lateral spinal cord hemisection in nine adult cats. After hemisection, although cats still performed split-belt locomotion, we observed several changes in the gait pattern compared with the intact state at early (1–2 wk) and late (7–8 wk) time points. Cats with larger lesions showed new coordination patterns between the fore- and hindlimbs, with the forelimbs taking more steps. Despite this change in fore-hind coordination, cats maintained consistent phasing between the fore- and hindlimbs. Adjustments in cycle and phase (stance and swing) durations between the slow and fast sides allowed animals to maintain 1:1 left-right coordination. Periods of triple support involving the right (ipsilesional) hindlimb decreased in favor of quad support and triple support involving the other limbs. Step and stride lengths decreased with concurrent changes in the right fore- and hindlimbs, possibly to avoid interference. The above adjustments in the gait pattern allowed cats to retain the ability to locomote in asymmetric conditions after incomplete SCI. We discuss potential plastic neuromechanical mechanisms involved in locomotor recovery in these conditions.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Everyday locomotion often involves left-right asymmetries, when turning, walking along circular paths, stepping on uneven terrains, etc. To show how incomplete spinal cord injury affects locomotor control in asymmetric conditions, we collected data before and after a thoracic lateral spinal hemisection on a split-belt treadmill with one side stepping faster than the other. We show that adjustments in kinematics and muscle activity allowed cats to retain the ability to perform asymmetric locomotion after hemisection.

INTRODUCTION

Spinal cord injury (SCI) impairs the ability to walk and stand and, depending on its severity, can lead to motor paralysis and/or a complete loss of sensation below the lesion. Several previous studies investigated the recovery of locomotion in various animal models and people with SCI (1–7). However, this recovery has primarily been studied during walking on a horizontal surface in a straight line or on a treadmill at a single or self-selected speed. We know less about the recovery of locomotion after incomplete SCI in conditions where the gait pattern is asymmetric between the left and right limbs, such as during turning or stepping along a circular trajectory. One way to generate a left-right gait asymmetry is by using a split-belt treadmill where the left and right limbs step at different speeds.

In cats and humans, split-belt locomotion requires adjustments in leg kinematics and muscle activity to maintain left-right coordination (8–13). These adjustments include a longer stance phase on the slow side and a longer swing phase on the fast side, as shown in both intact and spinal cats (8, 9, 13, 14), as well as in human adults and infants (10, 15–20). The double support period for the fast side (i.e., from contact of the fast limb to liftoff of the slow limb) is also longer compared with the double support period of the slow side in cats (21) and humans (20). Spatial adjustments include a longer stride length (distance traveled by a limb during a cycle) for the fast limb compared with the slow limb (20, 22, 23). Step length, the horizontal distance between the leading and trailing limbs at the contact of the leading limb, is longer on the slow side (slow limb leading) compared with the fast side (fast limb leading) during split-belt locomotion in cats (21) and humans (20, 22, 23). With increasing speed differences between the slow and fast belts, both cats (24, 25) and humans (26) progressively shift the lateral position of their body’s center of mass toward the slow-moving side.

Split-belt locomotion also reveals asymmetric adjustments of the activity (EMG; electromyography) of muscles controlling the limbs stepping on the slow and fast belts in cats and humans. For example, flexor and extensor burst durations of fore- and hindlimb/leg muscles follow changes in swing and stance durations, respectively (8, 9, 11, 12, 27). When compared with matched speeds during tied-belt locomotion, the mean EMG amplitude of extensor muscles increases on the slow side with increasing slow-fast speed differences during split-belt locomotion while it decreases on the fast side, consistent with a shift in weight support to the slow side (12, 24, 27). Kinematic and EMG changes occur similarly in the forelimbs and hindlimbs of intact cats and in the hindlimbs of spinal cats (i.e., cats with a spinal transection). These changes are consistent with adjustments mediated mainly by interactions between spinal locomotor networks and sensory feedback from the limbs (8, 11, 28).

With prolonged split-belt locomotion, some interlimb (but not intralimb) characteristics, such as double support periods and step lengths display a return toward symmetry in human adults, referred to as motor adaptation (20, 23). This motor adaptation is weak or absent in human children (22) and absent in intact and spinal cats (21). Thus, in cats, because of the lack of motor adaptation, split-belt locomotion allows studying the pattern in a left-right asymmetric condition from the first to the last step of an episode.

An interesting experimental model of incomplete SCI that can be used for investigation of the recovery of locomotion in the context of left-right asymmetries is a lateral hemisection of the spinal cord. A lateral hemisection is similar to the Brown-Séquard syndrome in humans and it generates left-right asymmetries in the gait pattern between the lesioned and nonlesioned sides [in rodents (29–31); cats (32–38) and humans (39, 40)]. Thus, combined with split-belt locomotion, the lateral hemisection model offers an intriguing substrate to investigate the recovery of locomotion in left-right asymmetric conditions. To better understand the recovery and modulation of the gait pattern following a unilateral SCI, we recorded kinematic and EMG data before and after a lateral hemisection at mid-thoracic levels during split-belt locomotion in adult cats. These recordings were made with both the lesioned (right) and nonlesioned (left) sides stepping on the slow and fast belts.

In the present study, we addressed the following questions. 1) Can cats maintain the ability to perform split-belt locomotion with the ipsilesional and contralesional sides stepping on the slow and fast belts? If so, what temporal adjustments in kinematics and muscle activity accompany the recovery of locomotion in these conditions? 2) Is a 1:1 left-right coordination (equal cycle duration) maintained after hemisection in both split-belt conditions and how is this achieved or lost? 3) How are periods of support (when limbs are in contact with the surface) affected by hemisection and modulated by split-belt locomotion? 4) Does interlimb coordination remain consistent after hemisection and how is it affected by split-belt locomotion? 5) What are the spatial adjustments after hemisection and how are these affected by split-belt locomotion? 6) What are the changes in EMG in the fore- and hindlimbs after hemisection and how are these modulated by split-belt locomotion?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Ethical Information

The Animal Care Committee of the Université de Sherbrooke approved all procedures in accordance with the policies and directives of the Canadian Council on Animal Care (Protocol 442-18). In the present study, we used nine adult cats (>1 yr of age at the time of experimentation), four females and five males, with mass between 3.4 kg and 5.6 kg. We followed the ARRIVE guidelines for animal studies (41). To reduce the number of animals used in research, cats participated in other studies to answer different scientific questions (14, 42–44). Before and for 8 wk after hemisection, all cats participated in other studies, such as tied-belt (equal left-right speeds) locomotion from 0.4 to 1.0 m/s. We also evoked cutaneous reflexes in three cats (cats GR, KA, and KI) by stimulating the superficial radial and superficial peroneal nerves during tied-belt and split-belt locomotion at 0.4 m/s and 0.8 m/s. Four cats (cats GR, KA, KI, and MB) also performed overground locomotion on a custom-built walkway and negotiated obstacles of different heights. At week 5 posthemisection, cutaneous nerves were stimulated with longer trains to induce stumbling corrective reactions in the fore- and hindlimbs during treadmill locomotion at 0.4 m/s and 0.8 m/s in three cats (cats GR, KA, and KI). Many of these manuscripts are in preparation.

Surgical Procedures and Electrode Implantation

We performed surgeries under aseptic conditions with sterilized instruments in an operating room. Prior to surgery, the cat was sedated with an intramuscular injection of butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg), acepromazine (0.1 mg/kg), and glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg) and inducted with another intramuscular injection of ketamine and diazepam (0.05 mL/kg) in a 1:1 ratio. The fur overlying the back, stomach, forelimbs, and hindlimbs was shaved and the skin was cleaned with chlorhexidine soap. The cat was then anesthetized with isoflurane (1.5%–3%) and O2 using a mask for a minimum of 5 min and then intubated with a flexible endotracheal tube. Isoflurane concentration was confirmed and adjusted throughout the surgery by monitoring cardiac and respiratory rates, applying pressure to the paw to detect limb withdrawal, and assessing muscle tone. A rectal thermometer monitored body temperature and we used a water-filled heating pad placed under the animal and an infrared lamp positioned ∼50 cm above to keep it within the physiological range (37 ± 0.5°C). Cats received a continuous infusion of lactated Ringer’s solution (3 mL/kg/h).

We directed pairs of Teflon-insulated multistrain fine wires (AS633; Cooner Wire, Chatsworth, CA) subcutaneously from two head-mounted 34-pin connectors (Omnetics Connector Corporation, Minneapolis, MN) and sewn them into the belly of selected forelimb and hindlimb muscles for bipolar recordings, with 1–2 mm of insulation stripped from each wire. The head connector was secured to the skull using dental acrylic and four to six screws. We verified electrode placement by electrically stimulating each muscle through the appropriate head connector channel.

At the end of the surgery, we injected an antibiotic (Cefovecin, 0.1 mL/kg) subcutaneously and taped a transdermal fentanyl patch (25 µg/h) to the back of the animal 2–3 cm rostral to the base of the tail. We injected buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg), a fast-acting analgesic, subcutaneously during surgery and ∼7 h after. Following surgery, we placed the cats in an incubator until they regained consciousness. At the conclusion of the experiments, cats received a lethal dose of pentobarbital (120 mg/kg) through the left or right cephalic vein.

Spinal Hemisection

We performed the spinal hemisection surgery after collecting data in the intact state. A small laminectomy was performed between the fifth and sixth thoracic vertebrae. After exposing the spinal cord, lidocaine (Xylocaine, 2%) was applied topically and injected intraspinally on the right side of the cord, which was then hemisected with surgical scissors. Hemostatic material (Spongostan) was inserted within the gap and muscles and skin were sewn back to close the opening in anatomic layers. The same pre- and postoperative treatments were administered as for the implantation surgery. In the days following the hemisection, cats were carefully monitored for voluntary bodily functions.

Experimental Protocol

Cats were trained with food and affection as reward to step on an animal treadmill with two independently controlled running surfaces 120 cm long and 30 cm wide (Bertec Corporation, Colombus, OH). A Plexiglas separator (120 cm long, 3 cm high, and 0.5 cm wide) was placed between the left and right belts to ensure that the limbs on the left and right sides stepped on separate belts. To prevent the cat from moving laterally on the treadmill, two Plexiglas separators (120 cm long, 50 cm high) were placed 30 cm apart from one another. The Plexiglas separators were held in place ∼0.5 cm above the treadmill belts by a metal frame. The treadmill setup is schematically shown in Fig. 1A. After a few days of training, cats could easily step with the left and right sides on their respective belts without contacting the centrally or laterally placed Plexiglas separators. Experiments began after a minimum of 2 wk of familiarization where cats performed tied-belt locomotion at multiple speeds and split-belt locomotion at various left-right (L-R) speed differences, or speed Δs, five times a week, with sessions lasting 20–30 min. As stated earlier, we also performed reflex testing and data collection in a walkway.

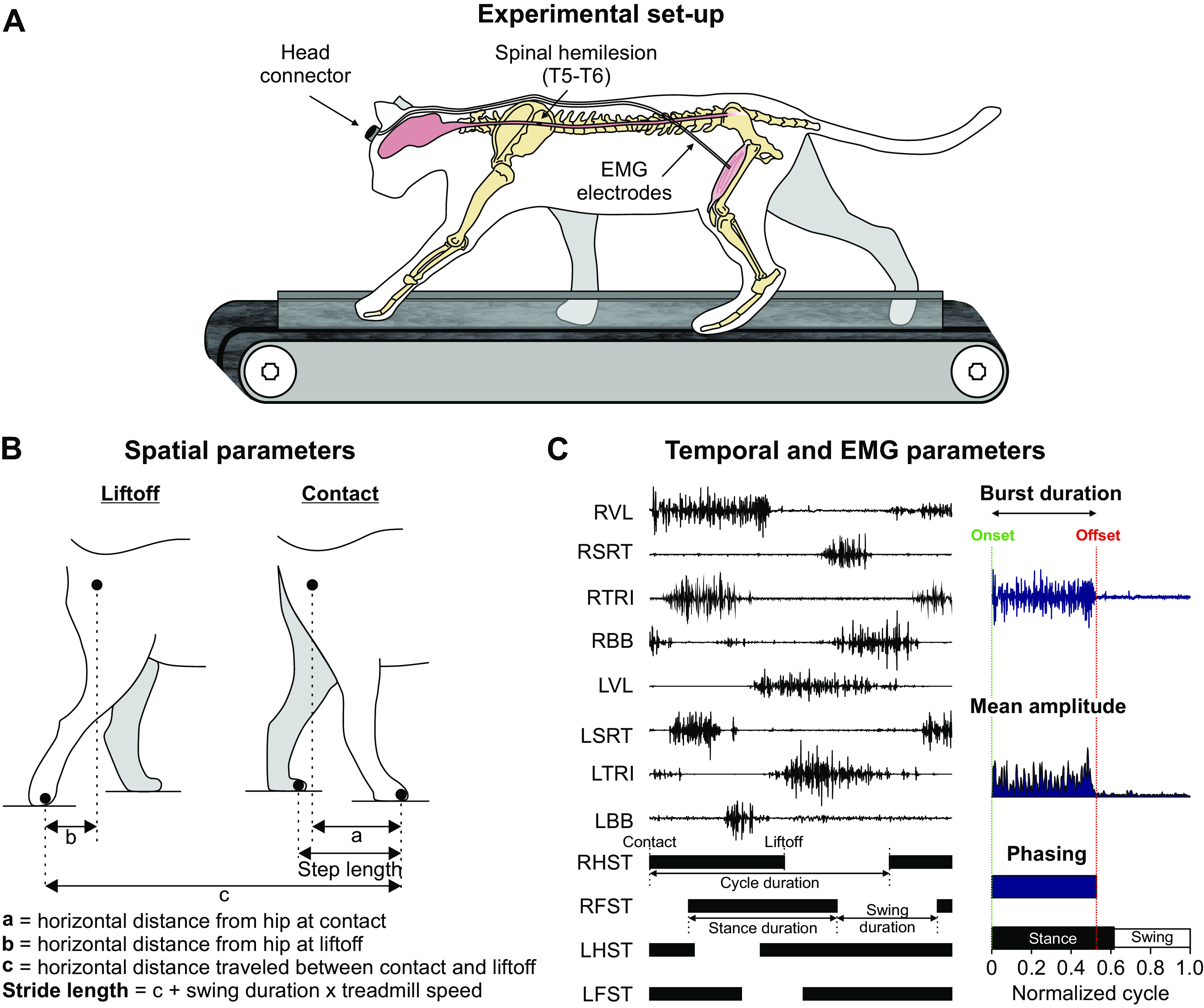

Figure 1.

Experimental setup and measured spatiotemporal parameters. A: experimental design showing electromyography (EMG) electrodes directed subcutaneously to muscles from a head connector and the site of spinal lesion. B: measured spatial parameters, including step length, stride length, and the horizontal distance of the paw at contact and liftoff relative to the hip. C: measured temporal and electromyography (EMG) variables. EMG activity is shown for two muscles of the left (L) hindlimb and two muscles of the right (R) hindlimb, vastus lateralis (VL); anterior sartorius (SRT); and for two muscles of the left forelimb and two muscles of the right forelimb, triceps brachii (TRI); biceps brachii (BB). Thick horizontal lines represent right hindlimb (RHST), right forelimb (RFST), left hindlimb (LHST), and left forelimb (LFST) stances phases. We measured EMG burst duration from onset to offset and mean EMG amplitude by integrating the full-wave rectified EMG burst from onset to offset divided by burst duration. We measured phasing as the onset and offset normalized to cycle duration.

Each cat performed one session that consisted of several locomotor episodes with the left and right belts operating at different speeds (split-belt locomotion). In these conditions, one side stepped at a treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s, referred to as the slow side, while the other side stepped at treadmill speeds from 0.5 to 1.0 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments, referred to as the fast side. The left and right sides were both used as the slow and fast sides. The different split-belt conditions were presented randomly and ∼30 s of rest and a food reward were given between episodes. The objective was to obtain ∼15 cycles per episode and a session took 20–25 min to get enough cycles in each of the split-belt conditions. In the intact state, all cats could step up to a speed on the fast side of 1.0 m/s. However, after spinal hemisection, only one cat could accomplish this speed and only four at 8 wk postlesion. Thus, to compare the intact and hemisected states, we used episodes with the fast side up to 0.8 m/s for analysis.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

We collected kinematic and EMG data before, 1–2 wk (H1-2) and 7–8 wk (H7-8) after the spinal hemisection. We refer to these three timepoints as states: intact, H1-2, and H7-8. Two cameras (Basler AcA640-100g) captured videos of the left and right sides at 60 frames/s with a spatial resolution of 640 × 480 pixels. A custom-made program (LabView) acquired the images and synchronized acquisition with EMG data. We analyzed each video offline using a deep-learning approach, DeepLabCut (45, 46), as recently described in the cat (47).

We determined the contact and liftoff of each limb by visual inspection. We defined contact as the first frame where the paw made visible contact with the treadmill surface while liftoff corresponded to the frame with the most caudal displacement of the toe. Cycle duration was measured from successive paw contacts of the same limb, while stance duration corresponded to the interval of time from paw contact to liftoff. Swing duration was measured as cycle duration minus stance duration. Durations for each limb were averaged for an episode. Based on contacts and liftoffs for each limb, we measured individual periods of support (double, triple, and quad) and expressed them as a percentage of cycle duration (42). During a normalized cycle, here defined from successive right hindlimb contacts, we identified nine periods of limb support (42, 48–50). We also evaluated temporal interlimb coordination by measuring phase intervals between pairs of limbs, defined as the absolute amount of time between contacts of two limbs divided by the cycle duration of the reference limbs (42–44, 51, 52). These values were then multiplied by 360 and expressed in degrees to illustrate their continuous nature and possible distributions (52).

We measured step lengths as the distance between the leading and trailing limbs for the shoulder (left and right forelimbs) and pelvic (left and right hindlimbs) girdles at stance onset of the leading limb (53). We measured stride length, defined as the distance between contact and liftoff of the limb added to the distance traveled by the treadmill during the swing phase. It was calculated by multiplying swing duration by treadmill speed (43, 54, 55). We also measured the horizontal distance between the hindpaw and hip and between the forepaw and shoulder at contact and liftoff (Fig. 1B).

EMG signals were preamplified (10×, custom-made system), bandpass filtered (30–1,000 Hz), and amplified (100–5,000×) using a 16-channel amplifier (AM Systems Model 3500, Sequim, WA). As we implanted more than 16 muscles per cat, we obtained data in each locomotor condition twice, one for each connector, as our data acquisition system does not currently allow us to record more than 16 channels simultaneously. EMG data were digitized (2,000 Hz) with a National Instruments card (NI 6032E), acquired with a custom-made acquisition software and stored on a computer. Although several muscles were implanted, we focused our analysis on eight muscles of left (L) and right (R) limbs: the long head of triceps brachii (LTRI, elbow extensor, n = 6; RTRI, n = 7), the flexor carpi ulnaris (LFCU, wrist plantar flexor, n = 4; RFCU, n = 5), the biceps brachii (LBB, elbow flexor, n = 8; RBB, n = 8), the vastus lateralis (LVL, knee extensor, n = 7; RVL, n = 7), the biceps femoris anterior (LBFA, hip extensor, n = 4; RBFA, n = 4), the lateral gastrocnemius (LLG, ankle extensor/knee flexor, n = 5; RLG, n = 4), the anterior sartorius (LSRT, hip flexor/knee extensor, n = 8; RSRT, n = 7), and the semitendinosus (LST, hip extensor/knee flexor, n = 5; RST, n = 7). The same experimenter (Lecomte) determined burst onsets and offsets visually from the raw EMG waveforms using a custom-made program. Burst duration was determined from onset to offset while mean EMG amplitude was measured by integrating the full-wave rectified EMG burst from onset to offset and dividing it by its burst duration (Fig. 1C). Cats performed split-belt locomotion with both the left and right sides as the slow and fast sides so that every muscle, which was implanted bilaterally, was recorded while its limb was stepping on the slow and the fast belts.

Histology

To confirm the extent of the spinal lesion, we performed histology. Following euthanasia, we dissected a 2-cm long segment of the spinal cord centered around the injury site and placed it in 25 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde solution (PFA in 0.1 M PBS, 4°C). After five days, the spinal cord was cryoprotected in PB 0.2 M containing 30% sucrose for 72 h at 4°C. We then sliced the spinal cord into 50-µm coronal sections using a cryostat (Leica CM1860, Leica Biosystems Inc., Concord, ON, Canada). Sections were mounted on gelatinized slides, dried overnight, and stained with 1% cresyl violet for 12 min. The slides were then washed once in water for 3 min before being dehydrated in successive baths of ethanol 50%, 70%, and 100%, 5 min each. After a final 5 min bath in xylene, slides were mounted with dibutylphthalate polystyrene xylene (Sigma-Aldrich Canada) and dried before being scanned using a Nanozoomer (Hamamastu Corporation, Bridgewater Township, NJ). We then performed qualitative and quantitative evaluations of the lesioned area.

Statistical Analysis

We performed statistical tests with IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). To compare between states and assess changes over time, we performed a two-factor (state × speed Δ) repeated-measures ANOVA with the cat as the experimental unit to determine the main effects and possible interactions for the following dependent variables: cycle and phase durations, support periods, distance from hip and shoulder, step and stride lengths, joint excursions, joint angles at contact and liftoff, EMG burst durations, amplitudes, and phasing. The interaction in the two-way repeated-measures ANOVA is to understand if there is an interaction between the two factors on the dependent variable. We only report the interaction when the main effects for state and speed Δ were both significant. Although we did not correct for multiple comparisons to avoid Type II errors (for a discussion, see Refs. 56 and 57), we used a confidence interval of 99% or a P ≤ 0.01 to determine significance. This increases the probability that significant differences correspond to robust and physiological/functional changes in the gait pattern. The normality of each variable was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. For phase intervals, we performed Rayleigh’s test to determine whether data points were randomly distributed (43, 44, 58, 59). The r value was calculated to measure the dispersion of values around the mean, with a value of 1 indicating a perfect concentration in one direction and a value of 0 indicating uniform distribution. Rayleigh’s z test was then performed to test the significance of the directional mean with the equation z = nr2 where n is the sample size (number of steps). To determine if there was a significant concentration around the mean with a P < 0.05, the z value was compared with a critical z value on Rayleigh’s table.

RESULTS

Patterns of Forelimb-Hindlimb Coordination after Lateral Hemisection and Their Changes during Split-Belt Locomotion

In the first few days after hemisection, the right hindlimb (ipsilesional) was flaccid (60). We only attempted treadmill locomotion one week after hemisection. We first started with tied-belt locomotion and at this time, all cats could perform the two split-belt conditions with full weight bearing and without external assistance from the experimenter (33, 34, 61, 62). To answer our first research question, cats performed the two split-belt conditions (left slow/right fast and right slow/left fast), with both the right (lesioned) and left (nonlesioned) sides stepping on the slow and fast belts at 1–2 wk (H1-2) and 7–8 wk (H7-8) after hemisection. All cats maintained a 1:1 left-right coordination at the shoulder and hip girdles.

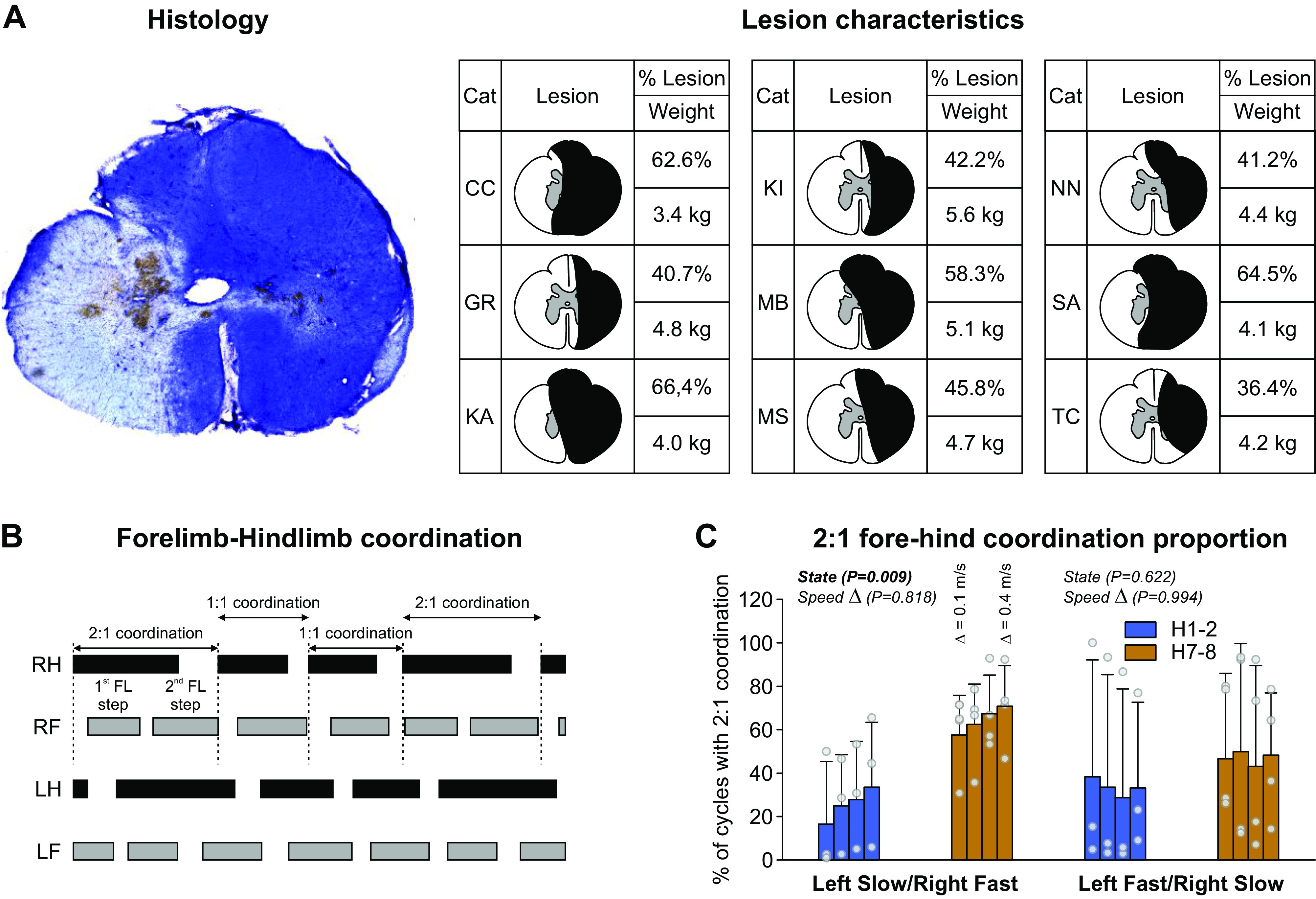

Figure 2A shows the histology of the spinal lesion with cresyl violet staining and a schematic drawing for all animals based on the staining. The extent of the spinal lesion had a mean of 50.9 ± 11.9% for the group, ranging from 36.4% to 66.4%, with greater damage on the right side compared with the left in all animals. For cats GR, KI, MS, NN, and TC, the lesion was less than 50%, sparing part of the ipsilateral dorsal columns and medioventral quadrant, except for NN where the entire right dorsal column was lesioned. For the four other cats (CC, KA, MB, and SA), the lesion extent exceeded 50%. For CC and SA, the left dorsal columns and medioventral quadrant were lesioned. In KA and MB, the left dorsal column was lesioned, but the left medioventral quadrant was spared.

Figure 2.

Lesion characteristics and forelimb-hindlimb coordination. A: lateral hemisection with the cresyl violet staining. The darker area is the lesioned area. Histology is from cat SA. The right panel shows lesion extent for all cats. B: when an unequal number of steps between the forelimbs (FL) and hindlimbs (HL) occurred, 1-1 and 2-1 FL-HL coordination could be observed within an episode. C: percentage of 2-1 FL-HL cycles during split-belt locomotion after a spinal hemisection (n = 4; 3 females and 1 male). Data are presented as means ± SD and individual points. P values comparing states (State) and speed Δ (main effects of repeated-measures ANOVA) are indicated. H1-2, 1–2 wk; H7-8, 7–8 wk.

In the intact state, all cats performed 1:1 coordination in the number of steps taken by the fore- and hindlimbs (fore-hind coordination) in 100% of trials. However, at H1-2 and H7-8, some cats showed some episodes with 2:1 fore-hind coordination, with the forelimbs performing two steps within a hindlimb cycle. Such coordination has been reported previously following various types of incomplete thoracic spinal lesions in rats and cats (44, 63–71). When this occurred, cycles with 1:1 and 2:1 fore-hind coordination were intermingled within the same locomotor episode (Fig. 2B). Four cats showed 2:1 fore-hind coordination at both H1-2 and H7-8 (cats CC, KA, MB, and SA) whereas the other five cats maintained 1:1 fore-hind coordination at both time points. At H1-2, cats MB and SA showed 2:1 fore-hind coordination in both split-belt conditions whereas cats KA and CC showed 2:1 fore-hind coordination in left slow/right fast and left fast/right slow conditions only, respectively. At H7-8, all four cats showed 2:1 fore-hind coordination in both split-belt conditions. In the four cats that displayed 2:1 fore-hind coordination, speed Δ did not modulate the proportion in left slow/right fast and left fast/right slow. We observed a significantly greater proportion of 2:1 fore-hind coordination at H7-8 compared with H1-2 (+150.98%) in left slow/right fast but not in left fast/right slow (Fig. 2C).

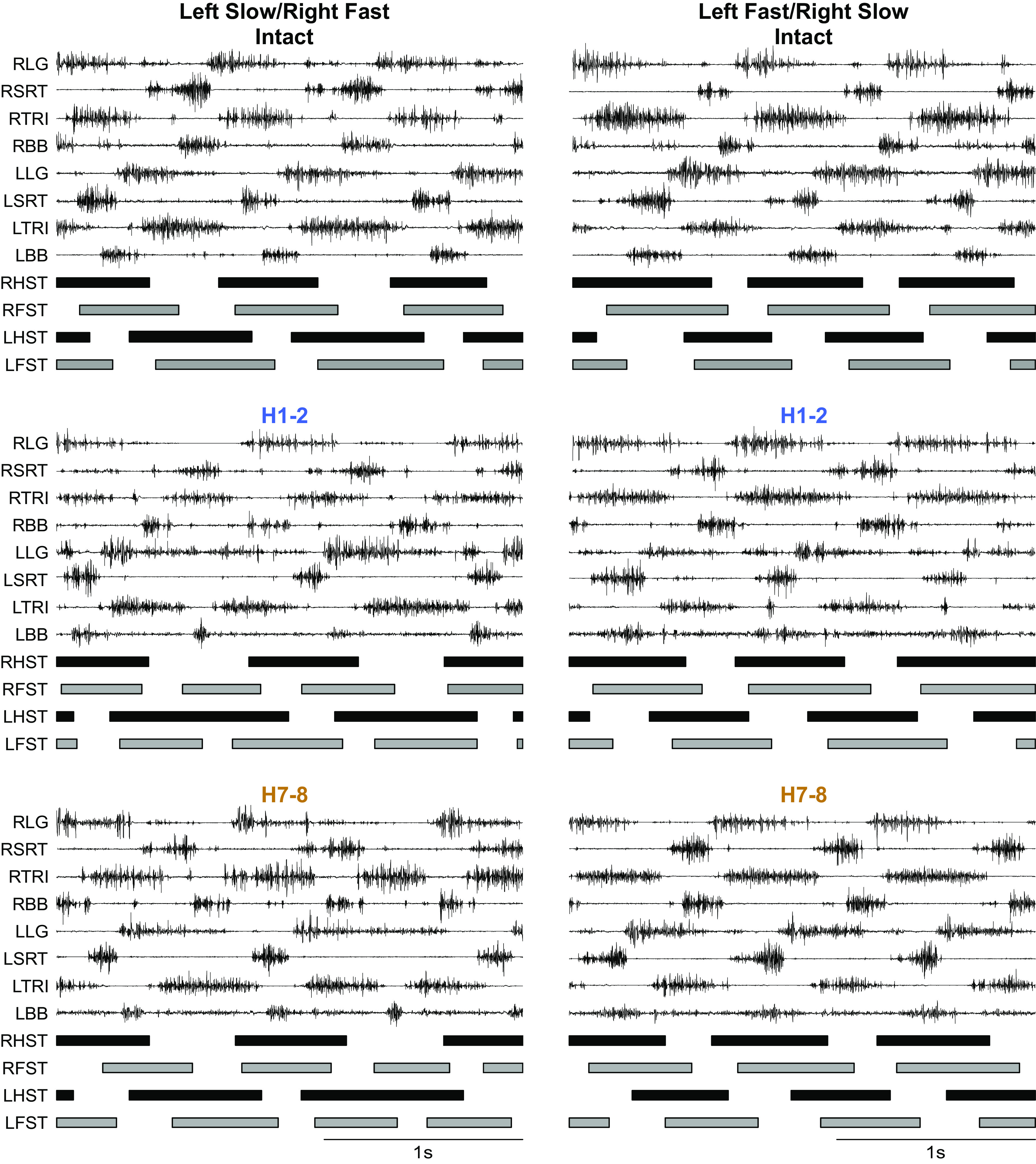

Figure 3 shows raw EMG waveforms of four muscles bilaterally with the stance phases of the four limbs in one cat in the intact state and at H1-2 and H7-8 in the two split-belt conditions for cat KA. The slow and fast belts operated at 0.4 m/s and 0.7 m/s, respectively (speed Δ 0.3 m/s). We can observe several changes in the pattern. In the intact state, the fore- and hindlimbs performed an equal number of steps, which corresponded to 1:1 fore-hind coordination. In both split-belt conditions in the intact state (Fig. 3, top), stance phase and TRI/LG burst durations were longer when stepping on the slow belt in the fore- and hindlimbs. Swing and BB/SRT burst durations were longer in the forelimbs and hindlimbs stepping on the fast belt. At H1-2 (Fig. 3, middle), the pattern changed with the appearance of 2:1 fore-hind coordination in left slow/right fast but not in left fast/right slow. In the forelimbs, stance phase and TRI burst durations remained longer when stepping on the slow belt while swing and BB burst durations remained longer when stepping on the fast belt. In the hindlimbs, we observed a noticeable difference between the split-belt conditions. In left slow/right fast, left-right differences were maintained, with longer stance and LG burst durations in the left/slow hindlimb, and longer swing and SRT burst durations in the fast/right hindlimb. In left fast/right slow, left-right differences between the slow and fast hindlimbs were not evident, with approximately equal stance and swing durations and LG and SRT burst durations. At H7-8 (Fig. 3, bottom), the modulation of forelimb phase and burst durations by split-belt locomotion remained largely the same as in the intact state and at H1-2. In the hindlimbs, left-right differences in phase and burst durations were maintained in left slow/right fast and in left fast/right slow conditions compared with H1-2. Thus, the hemisection affected the modulation of phase and burst durations by split-belt locomotion.

Figure 3.

Modulation of the locomotor pattern during split-belt locomotion in the intact state, 1–2 wk (H1-2) and 7–8 wk (H7-8). Each panel shows the electromyography (EMG) of forelimb and hindlimb muscles recorded bilaterally (L, left; R, right) along with the stance phases of the four limbs during split-belt locomotion at speed Δ = 0.3 m/s in left slow/right fast (left) and left fast/right slow (right) conditions. Vertical scale is optimized for readability. Data shown are from cat female KA. BB, biceps brachii; LFST, left forelimb stance; LG, lateral gastrocnemius; LHST, left hindlimb stance; RFST, right forelimb stance; RHST, right hindlimb stance; SRT, anterior sartorius; TRI, triceps brachii.

Split-Belt Locomotion Modulates Cycle and Phase Durations after Lateral Hemisection

Our second research question was to determine if a 1:1 left-right coordination (equal cycle duration) was maintained after hemisection in both split-belt conditions and how this coordination was achieved or lost. At both time points after hemisection, cats maintained a 1:1 left-right coordination at the shoulder and hip girdles. To determine how the hemisection and split-belt locomotion modulates temporal gait variables to maintain 1:1 left-right coordination, we measured cycle and phase durations in all four limbs in the two split-belt conditions (Fig. 4). For these analyses, we only considered cycles with 1:1 fore-hind coordination, as some cats did not display 2:1 fore-hind coordination after hemisection.

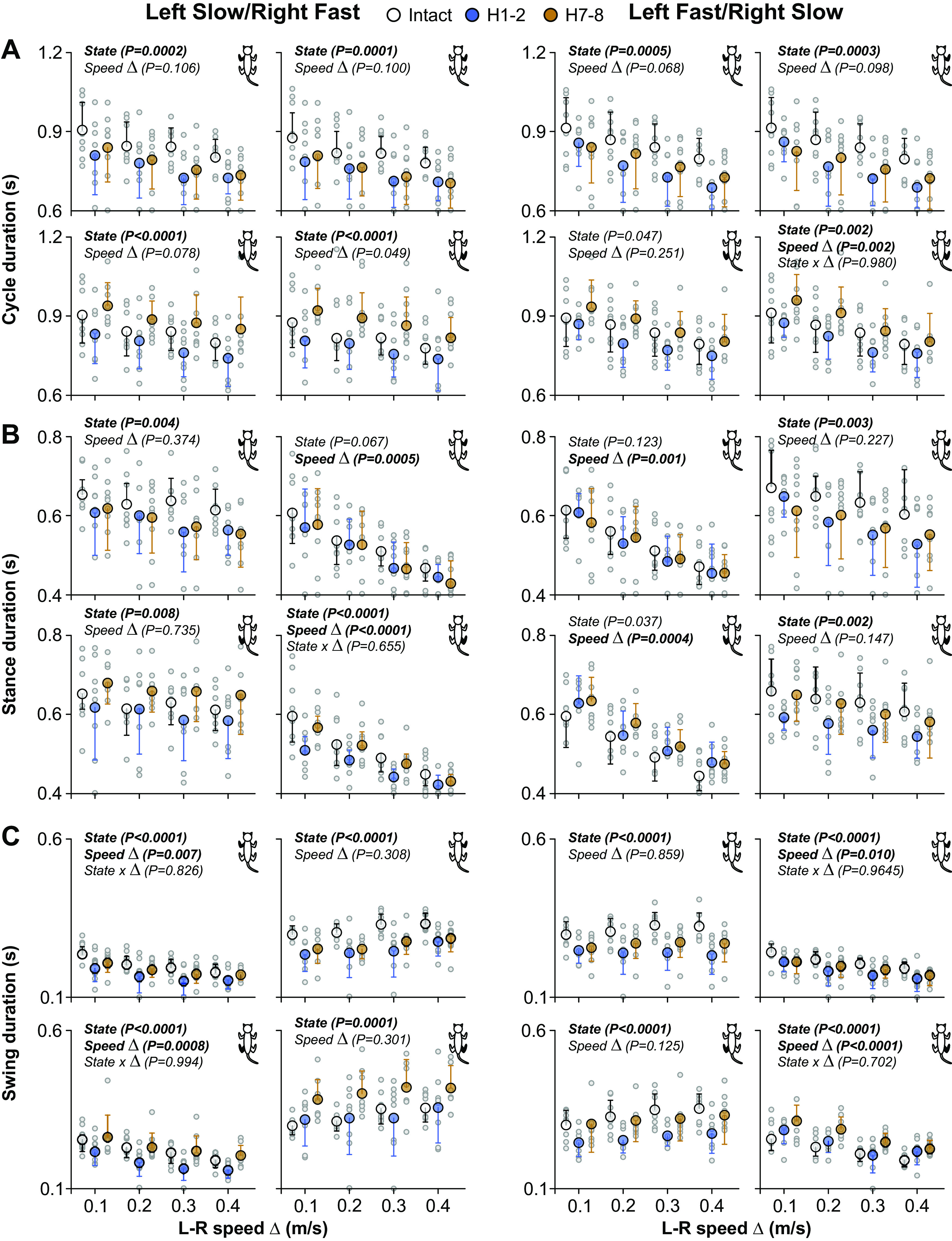

Figure 4.

Modulation of temporal parameters during quadrupedal split-belt locomotion in intact cats and after spinal hemisection across speeds. Left and right panels show cycle (A), stance (B), and swing (C) duration as a function of the speed Δ between the left and right sides (L-R speed Δ). In left panels, the left side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s whereas the right side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. In right panels, the right side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the left side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. Each panel shows cycle, stance, or swing duration for 1 of the 4 limbs. The limb shown in each panel is filled in black in the cat diagram at top right. Data are presented as means ± SD and individual points. For each speed Δ, we averaged 9–15 cycles per cat (n = 9 cats; 4 females and 5 males). P values comparing states (State), speed Δ, and interaction between states and speed (State × Δ) are indicated (main effects of repeated-measures ANOVA).

Cycle duration.

We found a significant effect of state on the cycle duration of all limbs in both split-belt conditions, with the exception of LH in the left fast/right slow condition (Fig. 4A). Table 1 summarizes the results of pairwise comparisons and significant % differences between intact, H1-2, and H7-8. LF and RF cycle durations were significantly greater in the intact state compared with H1-2 and H7-8 in both split-belt conditions. LH cycle duration was significantly greater at H7-8 compared with H1-2 in the left slow/right fast condition whereas RH cycle durations were significantly greater at H7-8 compared with H1-2 in both split-belt conditions. Surprisingly, speed Δ did not significantly affect cycle duration, except in RH in the left fast/right slow condition, with no significant interaction between state and speed Δ.

Table 1.

Cycle and phase durations before and after a lateral hemisection during split-belt locomotion

| Left Slow/Right Fast |

Left Fast/Right Slow |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF | RF | LH | RH | LF | RF | LH | RH | |

| Cycle duration | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0189 | 0.0756 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.1013 | |

| −10.49% | −10.62% | −11.00% | −11.08% | |||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0004 | <0.0001 | 0.0571 | 0.0144 | 0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.1447 | |

| −8.05% | −9.35% | −7.89% | −9.11% | |||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.482 | 0.8161 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.4805 | 0.7891 | 0.0007 | |

| +13.08% | +13.93% | +9.25% | ||||||

| Stance duration | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0015 | 0.4428 | <0.0001 | 0.0047 | 0.0054 | |||

| −8.01% | −11.58% | −9.51% | −10.28% | |||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0016 | 0.0751 | 0.1850 | 0.0028 | 0.8798 | |||

| −7.63% | −8.65% | |||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.9758 | 0.0037 | 0.0014 | 0.9985 | 0.0193 | |||

| +10.17% | +9.27% | |||||||

| Swing duration | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.9955 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.269 |

| −19.38% | −21.19% | −18.83% | −23.50% | −15.76% | −21.87% | |||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0013 | <0.0001 | 0.7044 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.9515 | <0.0001 |

| −9.31% | −15.51% | +22.83% | −14.74% | −10.50% | +20.83% | |||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.0015 | 0.0458 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0158 | 0.0471 | <0.0001 | 0.0012 |

| +12.49% | +27.06% | +22.70% | +11.44% | +22.50% | +11.90% | |||

The table shows the results of pairwise comparisons when a significant main effect was found and significant % differences between intact, 1–2 wk (H1-2), and 7–8 wk (H7-8). LF, left forelimb; LH, left hindlimb; RF, right forelimb; RH, right hindlimb.

Stance duration.

We found a significant effect of state on the stance duration of the left limbs (LF and LH) and RH in left slow/right fast and the right limbs (RF and RH) in left fast/right slow (Fig. 4B). Table 1 summarizes the results of pairwise comparisons and significant % differences between intact, H1-2, and H7-8. LF stance duration was significantly greater in the intact state compared with H1-2 and H7-8 in the left slow/right fast condition only. RF stance duration was significantly greater in the intact state compared with H1-2 and H7-8 in the left fast/right slow condition only. Thus, forelimb stance duration decreased after hemisection when stepping on the slow belt. We observed a significant main effect of state for LH stance duration in left slow/right fast but pairwise comparisons revealed no significant differences between time points. LH stance duration did not change after hemisection in left fast/right slow. On the other hand, RH stance duration significantly decreased at H1-2 in both split-belt conditions and returned to intact levels at H7-8. Stance duration significantly decreased with increasing speed Δ when the fore- and hindlimbs were stepping on the fast belt: RF and RH in left slow/right fast; LF and LH in left fast/right slow. We found no significant interaction between state and speed Δ, indicating that state does not affect the modulation of stance duration with speed Δ.

Swing duration.

We found a significant effect of state on the swing duration of all limbs in both split-belt conditions (Fig. 4C). Table 1 summarizes the results of pairwise comparisons and significant percentage differences between intact, H1-2, and H7-8. LF, and RF swing durations significantly decreased after hemisection compared with the intact state in both split-belt conditions, but LF swing duration showed some recovery at H7-8. LH swing duration significantly decreased at H1-2 compared with the intact state in both split-belt conditions but returned to intact levels at H7-8. On the other hand, RH swing duration significantly increased after hemisection in both split-belt conditions at H7-8. Swing duration significantly decreased with increasing speed Δ when the fore- and hindlimbs were stepping on the slow belt: LF and LH in left slow/right fast; RF and RH in left fast/right slow. We found no significant interaction between state and speed Δ, indicating that state does not affect the modulation of swing duration with speed Δ.

These results show that adjustments in phase durations of the left and right fore- and hindlimbs help maintain 1:1 left-right coordination between the slow and fast sides during split-belt locomotion after hemisection.

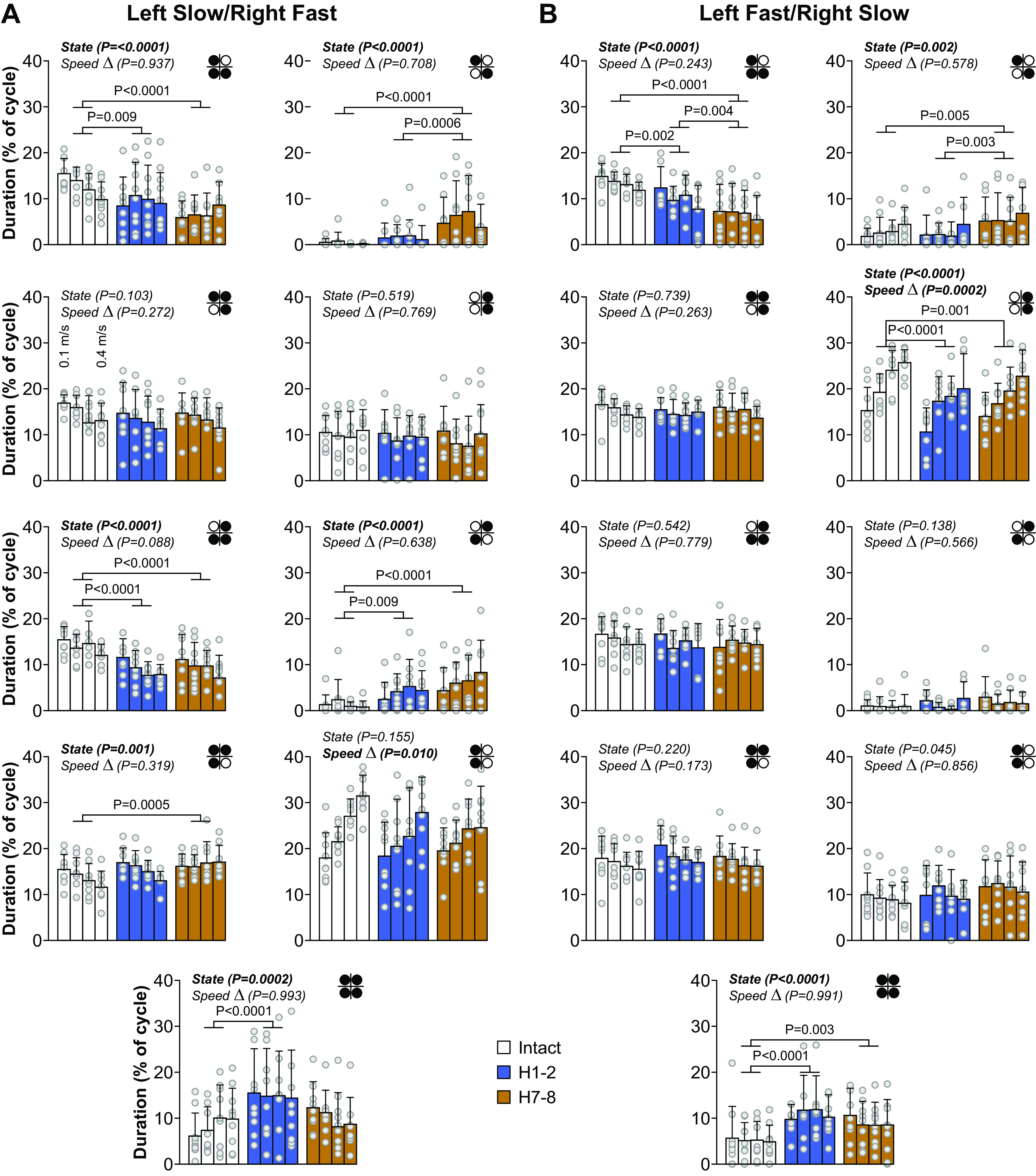

Periods of Support Are Altered after Hemisection and Modulated by Split-Belt Locomotion

Our third research question was to determine how hemisection affects periods of support (when limbs are in contact with the surface) and their modulation by split-belt locomotion. We generally find eight individual support periods during quadrupedal locomotion in a normalized cycle (14, 42, 72). In intact cats, split-belt locomotion modulates support periods, with an increase in homolateral double support periods and a reduction in periods of triple support as speed Δ increases (14). Note that a period of double support can become a period of quad support in some cycles, thus we can find nine different support periods. Here, we investigated changes in support periods after a right lateral hemisection and their modulation by split-belt locomotion. Figure 5 shows the relative duration (i.e., as a % of cycle duration) of nine support periods for the group in left slow/right fast (Fig. 5A) and left fast/right slow (Fig. 5B). Some support periods increased after hemisection compared with the intact state while others decreased. In left slow/right fast, both diagonal support periods (LF-RH and RF-LH) increased at H1-2 and H7-8, the triple support period involving LF-RF-LH at H7-8, and the quadrupedal support period at H1-2. In contrast, the two triple support periods involving the two hindlimbs (LF-LH-RH and RF-LH-RH) decreased after hemisection at H1-2 and H7-8. In the left fast/right slow condition, the diagonal support period involving LF-RH and the quadrupedal support period increased after hemisection whereas the triple support period LF-LH-RH and the right homolateral support period (RF-RH) decreased. Table 2 summarizes the significant changes in support periods with state and % differences. Interestingly, speed Δ significantly affected homolateral support periods when the limbs stepped on the slow belt, with an increase in homolateral support with increasing speed Δ. We found no significant interactions between state and speed Δ for homolateral support periods, indicating that state does not affect the modulation by speed Δ. Taken together, changes in support periods after hemisection indicate redistribution of the animal’s weight away from the ipsilesional right hindlimb.

Figure 5.

Modulation of support periods during quadrupedal split-belt locomotion in intact cats and after a spinal hemisection across speeds. Left (A) and right (B) panels show proportion of each support period for each speed Δ and each state. The limbs contacting the surface are shown in black in the footfall diagram in each panel. Top left, top right, bottom left, and bottom right circles represent left forelimb, right forelimb, left hindlimb, and right hindlimb, respectively. Data are presented as means ± SD and individual points. For each speed Δ, we averaged 9–15 cycles per cat (n = 9 cats; 4 females and 5 males). In A, the left side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the right side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. In B, the right side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the left side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. P values comparing states (State) and speed Δ (main effects of repeated measures ANOVA) and pairwise comparisons are indicated.

Table 2.

Support periods before and after a lateral hemisection during split-belt locomotion

| Left Slow/Right Fast |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | Period 7 | Period 8 | Period 9 | |

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0089 | 0.3044 | <0.0001 | 0.0086 | 0.0381 | <0.0001 | |||

| −25.70% | −34.54% | +195.84% | +78.32% | ||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.1593 | |||

| −46.57% | +1,274.0% | −32.31% | +357.74% | +21.24% | |||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.0382 | 0.0006 | 0.9413 | 0.1027 | 0.3221 | 0.0201 | |||

| +238.91% | |||||||||

| Left Fast/Right Slow |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | Period 7 | Period 8 | Period 9 | |

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0014 | 0.8973 | <0.0001 | 0.3501 | <0.0001 | ||||

| −24.30% | −21.29% | +107.70% | |||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | 0.0043 | 0.0012 | 0.0338 | 0.0025 | ||||

| −50.00% | +90.59% | −13.32% | +72.44% | ||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.0037 | 0.0028 | 0.3261 | 0.5718 | 0.1192 | ||||

| −33.95% | +109.22% | ||||||||

The table shows the results of pairwise comparisons when a significant main effect was found and significant % differences between intact, 1–2 wk (H1-2), and 7–8 wk (H7-8).

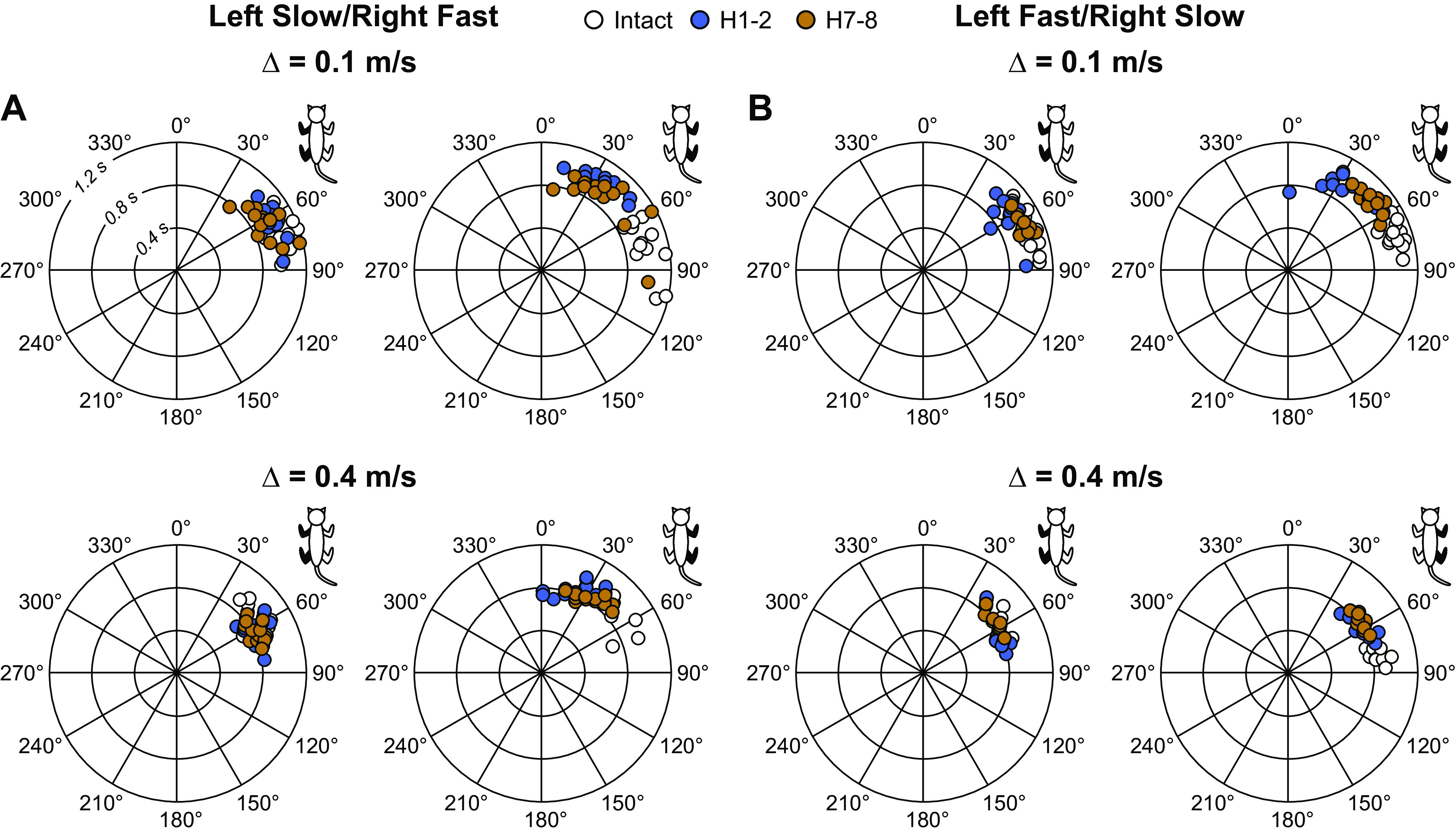

Temporal Interlimb Coordination Is Altered after Lateral Hemisection during Split-Belt Locomotion but Remains Consistent

Our fourth research question was to determine if interlimb coordination remained consistent after hemisection and how it was affected by split-belt locomotion. To determine if interlimb coordination was lost or maintained after hemisection and its modulation by split-belt locomotion, we measured phase intervals between paw contacts of six limb pairs in both split-belt conditions before and after hemisection. Figure 6 shows phase intervals for homolateral limbs in cat KI at 0.1 m/s and 0.4 m/s in left slow/right fast (Fig. 6A) and left fast/right slow (Fig. 6B). This cat maintained a 1:1 fore-hind coordination. Although there were some shifts in phase intervals after hemisection, we can see that values remained clustered at the three timepoints. Rayleigh’s test for individual cats and all limb pairs confirmed that phase intervals were not distributed randomly, with r values ranging from 0.80 to 1.00 (Table 3). In the presence of 2:1 fore-hind coordination, even when we separated cycles for the first and second forelimb steps, we still found r values ranging from 0.82 to 1.00. For all phase intervals, z values for Rayleigh’s z test were superior to the z critical value, indicating that interlimb coordination remained consistent, even between the fore- and hindlimbs with 1:1 and 2:1 fore-hind coordination.

Figure 6.

Step-by-step homolateral phasing between limbs during quadrupedal split-belt locomotion before and after a spinal hemisection. Phase interval values were measured by calculating the interval of time between limb contacts. These values were then normalized to cycle duration of the right hindlimb and multiplied by 360. In the circular plots, phase intervals are expressed in degrees around the circumference, whereas cycle durations are plotted in radii. Each data point represents a locomotor cycle from one session in a single male cat, KI. The limbs pairs in each panel are filled in black in the cat diagram at the top right. In A, the left side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the right side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5 m/s (top) or 0.8 m/s (bottom). In B, the right side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the left side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5 m/s (top) or 0.8 m/s (bottom).

Table 3.

Circular statistics on phase intervals before and after lateral hemisection during split-belt locomotion

| Δ = 0.1 m/s |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Slow/Right Fast |

Left Fast/Right Slow |

|||||||||||

| Intact |

H1-2 |

H7-8 |

Intact |

H1-2 |

H7-8 |

|||||||

| LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | |

| CC | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| GR | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.66 |

| KA | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| KI | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| MB | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.84 |

| MS | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 |

| NN | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| SA | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| TC | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| H1-2 |

H7-8 |

H1-2 |

H7-8 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF-LH |

RF-RH |

LF-LH |

RF-RH |

LF-LH |

RF-RH |

LF-LH |

RF-RH |

|||||||||

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | |

| CC | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.89 | ||||

| KA | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.88 | ||||||||||||

| MB | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.91 | ||||||||

| ST | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.87 |

| Δ = 0.4 m/s |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Slow/Right Fast |

Left Fast/Right Slow |

|||||||||||

| Intact |

H1-2 |

H7-8 |

Intact |

H1-2 |

H7-8 |

|||||||

| LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | LF-LH | RF-RH | |

| CC | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| GR | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| KA | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.82 |

| KI | 0.99 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| MB | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.90 |

| MS | 0.99 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| NN | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| SA | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

| TC | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.98 |

| H1-2 |

H7-8 |

H1-2 |

H7-8 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF-LH |

RF-RH |

LF-LH |

RF-RH |

LF-LH |

RF-RH |

LF-LH |

RF-RH |

|||||||||

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 2 | |

| CC | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.91 | ||||

| KA | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.99 | ||||

| MB | 0.95 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.98 | ||||||||

| ST | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.87 | ||||

The table shows r values of Rayleigh’s test for homolateral pairings for phase intervals in each cat at Δ = 0.1 m/s and Δ = 0.4 m/s. The left column indicates cat names. All 9 cats showed 1:1 fore-hind coordination and r values are indicated at the three timepoints. After hemisection, 4 cats (CC, KA, MB, and ST) showed 2:1 fore-hind coordination at 1–2 wk (H1-2) and/or 7–8 wk (H7-8). We indicate the r values for the first (step 1) and second (step 2) forelimb steps. For each speed Δ and state, we averaged 9–15 cycles per cat (n = 9 cats, 4 females and 5 males). LF, left forelimb; LH, left hindlimb; RF, right forelimb; RH, right hindlimb.

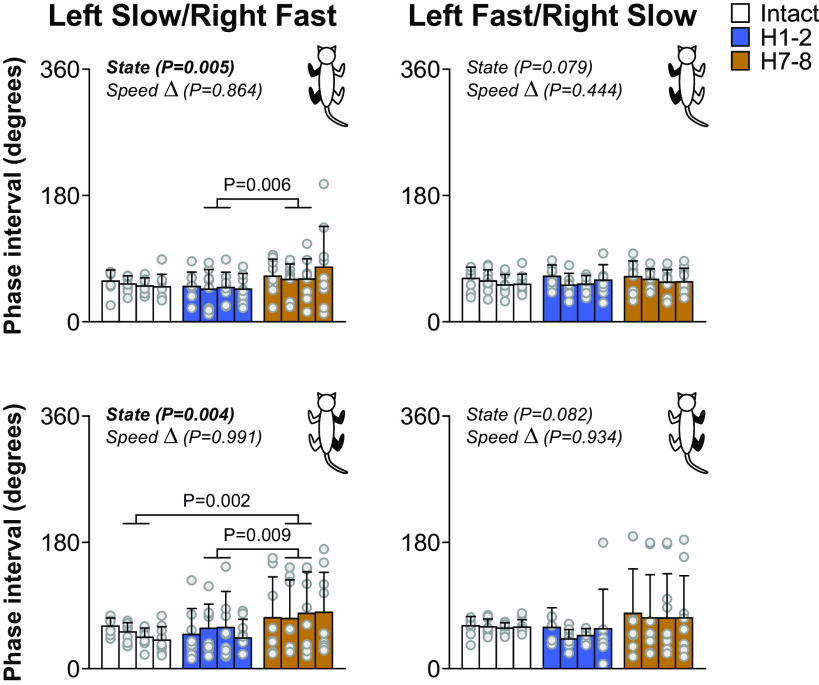

Figure 7 shows phase intervals for left and right homolateral limbs in all cats in both split-belt conditions. In left slow/right fast (left), the phase interval of the left homolateral limbs increased (+37.04%) at H7-8 compared with H1-2. It also increased for right homolateral limbs at H7-8 compared with Intact (+52.30%) and H1-2 (+45.24%). This increase in phase interval indicates a greater delay in forelimb contact compared with the hindlimb. In contrast, in left fast/right slow (right), left and right homolateral phase intervals did not change after hemisection.

Figure 7.

Homolateral phasing between limbs during quadrupedal split-belt locomotion before and after a spinal hemisection. Left and right: homolateral phasing for each speed Δ and each state for left limbs and right limbs. The limb pair shown in each panel is filled in black in the cat diagram. Data are presented as means ± SD and individual points. For each speed Δ, we averaged 9–15 cycles per cat (n = 9 cats; 4 females and 5 males). On the left, the left side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the right side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. On the right, the right side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the left side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. P values comparing states (State) and speed Δ (main effects of repeated-measures ANOVA) are indicated.

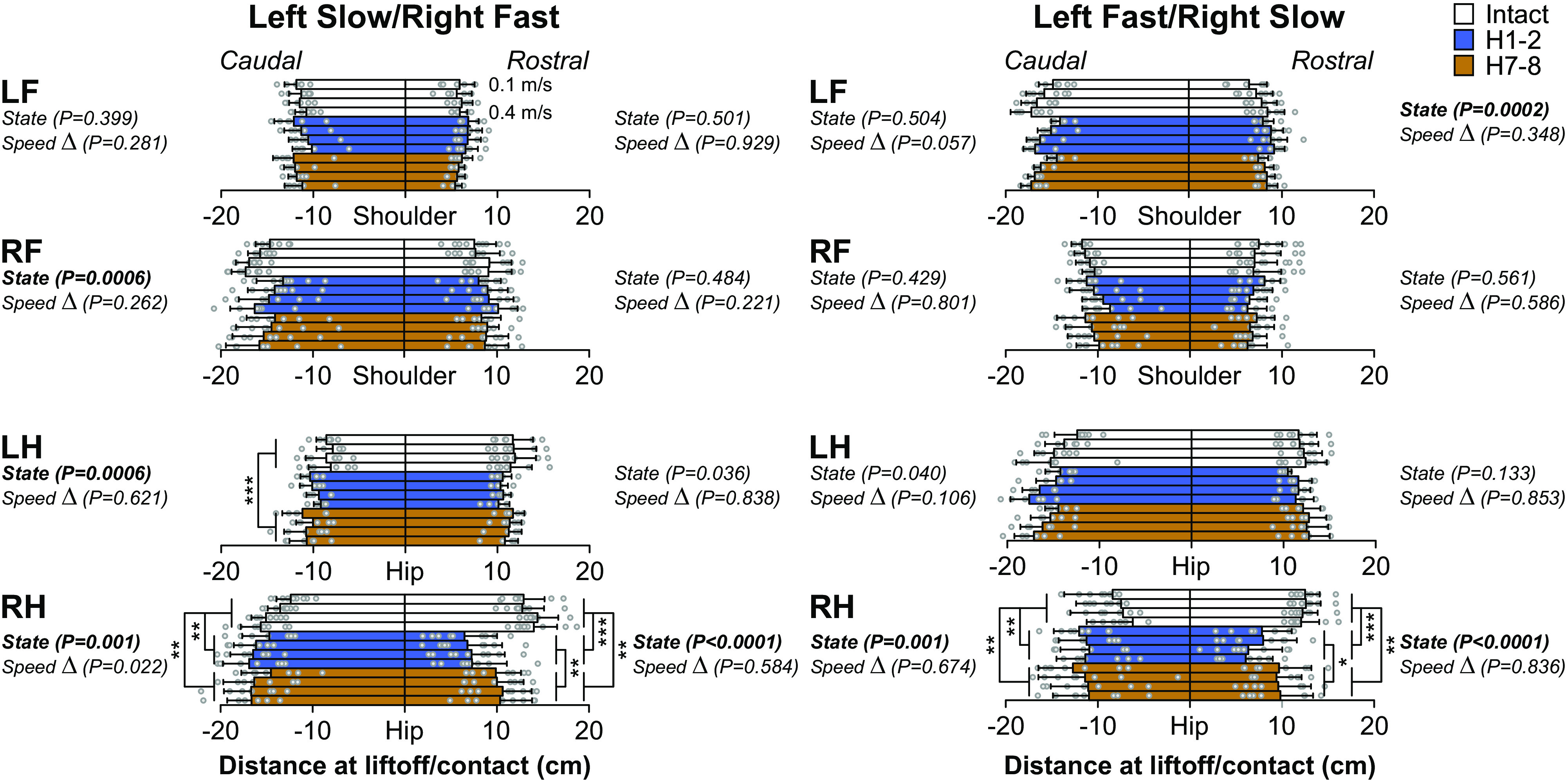

Spatial Adjustments after Lateral Hemisection during Split-Belt Locomotion

Our fifth research question was to determine the spatial adjustments occurring after hemisection and their modulation by split-belt locomotion. We first measured the horizontal distance of the fore- and hindpaws at contact and liftoff. Proper positioning of the paws at phase transitions is important for propulsion and dynamic balance. Split-belt locomotion induces left-right differences in the distance from the shoulder or hip at liftoff, with the limb stepping on the fast belt transitioning to swing more caudally than the limb on the slow belt, as shown in intact and spinal cats (9, 13) and in Fig. 8. The hemisection did not significantly alter the position of the left and right forepaws at contact or liftoff in both split-belt conditions (Fig. 8, top two panels). Although we observed a main effect of state for LF at contact in left fast/right slow and RF at liftoff in left slow/right fast, pairwise comparisons revealed no significant differences between time points. On the other hand, the hemisection significantly altered the position of RH at contact and liftoff. After hemisection, RH position was significantly less rostral (closer to the hip) at contact in left slow/right fast (P < 0.0001, −48.45% at H1-2 and P = 0.0001, −24.43% at H7-8) and left fast/right slow (P < 0.0001, −42.91% at H1-2 and P = 0.0006, −22.07% at H7-8). The placement at contact recovered at H7-8 but remained less rostral than in the intact state. The position of RH at liftoff was significantly more caudal after hemisection in left slow/right fast (P = 0.005, +13.41% at H1-2 and P = 0.004, +13.37% at H7-8) and left fast/right slow (P = 0.0005, +54.99% at H1-2 and P = 0.0002, +56.79% at H7-8). RH position did not recover with time after hemisection. In left slow/right fast, the position of LH at liftoff was significantly more caudal at H7-8 (P < 0.0001, +28.67% at H7-8) with no change in left fast/right slow.

Figure 8.

Modulation of distance at shoulder and hip during quadrupedal split-belt locomotion in intact cats and after a spinal hemisection across speeds. Left and right: the distance at shoulder for forelimbs and at hip for hindlimbs, at liftoff/contact for each speed Δ and each state. Data are presented as means ± SD and individual points. For each speed Δ, we averaged 9–15 cycles per cat (n = 9 cats; 4 females and 5 males). On the left, the left side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the right side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. On the right, the right side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the left side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. P values comparing states (State) and speed Δ (main effects of repeated-measures ANOVA) are indicated. Asterisks indicate significant difference between state (pairwise comparison): *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001. LF, left forelimb; LH, left hindlimb; RF, right forelimb; RH, right hindlimb.

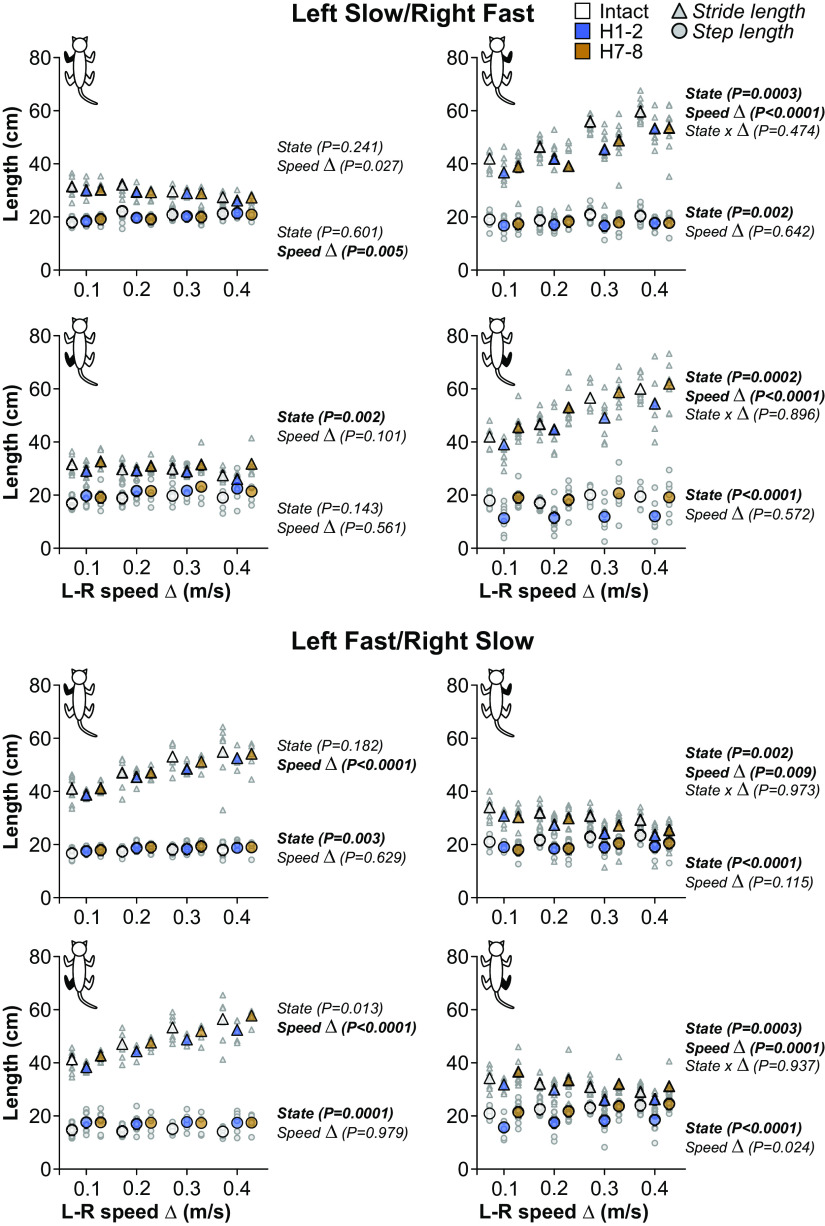

Stride length.

We measured stride length to determine the distance traveled by each limb before and after hemisection (Fig. 9). Table 4 summarizes the results of pairwise comparisons and significant % differences between intact, H1-2, and H7-8. The hemisection mainly affected stride length in the right limbs (RF and RH) in both split-belt conditions. LH stride length showed a state-dependent effect in the left slow/right fast condition, but only H7-8 was significantly greater than H1-2. RF stride length decreased after hemisection at H1-2 and H7-8 compared with the intact state in left slow/right fast. In the same condition, RH stride length decreased at H1-2 compared with the intact state but recovered at H7-8. In left fast/right slow, RF and RH stride lengths decreased at H1-2 compared with the intact state but recovered at H7-8 only in the RH. In the right limbs (RF and RH), stride lengths significantly increased (left slow/right fast) or decreased (left fast/right slow) with increasing speed Δ. In the left limbs (LF and LH), stride length significantly increased with speed Δ but only when they stepped on the fast belt (left fast/right slow). We found no significant interactions between state and speed Δ, indicating that the hemisection did not affect the modulation with speed Δ when present.

Figure 9.

Modulation of step and stride lengths during quadrupedal split-belt locomotion in intact cats and after a spinal hemisection across speeds. Top and bottom: step length and stride length for each speed Δ and each state. Data are presented as mean and individual points. For each speed Δ, we averaged 9–15 cycles per cat (n = 9 cats; 4 females and 5 males). The limb shown in each panel is filled in black in the cat diagram at top left. In the top, the left side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the right side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. In the bottom, the right side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the left side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. P values comparing states (State), speed Δ, and interaction between states and speed (State × Δ), (main effects of repeated measures ANOVA) are indicated.

Table 4.

Step and stride lengths before and after a lateral hemisection during split-belt locomotion

| Left Slow/Right Fast |

Left Fast/Right Slow |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF | RF | LH | RH | LF | RF | LH | RH | |

| Step length | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0009 | <0.0001 | 0.1329 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| −13.62% | −37.42% | −14.94% | +19.99% | −22.60% | ||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0202 | 0.8330 | 0.0027 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.9696 | ||

| +7.07% | −12.71% | +20.11% | ||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.5257 | <0.0001 | 0.3427 | 0.7278 | 0.9748 | <0.0001 | ||

| +65.61% | +30.37% | |||||||

| Stride length | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0005 | 0.2749 | 0.0147 | 0.0003 | 0.0037 | |||

| −13.06% | −15.86% | −9.65% | ||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0058 | 0.0191 | 0.0696 | 0.0144 | 0.1066 | |||

| −12.91% | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.6974 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | 0.3276 | <0.0001 | |||

| +13.05% | +17.08% | +17.02% | ||||||

The table shows results of pairwise comparisons when a significant main effect was found and significant % differences between intact, 1–2 weeks (H1-2) and 7–8 weeks (H7-8). LF, left forelimb; LH, left hindlimb; RF, right forelimb; RH, right hindlimb.

Step length.

We measured step length to assess the distance between homologous limbs in both split-belt conditions before and after hemisection (Fig. 9). Table 4 summarizes the results of pairwise comparisons and significant % differences between intact, H1-2, and H7-8. The hemisection significantly affected step length in the right limbs (RF and RH) in both split-belt conditions and for the left limbs (LF and LH) when they were stepping on the fast belt (left fast/right slow). In left slow/right fast, RF step length decreased at H1-2 compared with the intact state but recovered at H7-8. In left fast/right slow, RF step length decreased at H1-2 and remained decreased at H7-8 compared with the intact state. RH step length decreased at H1-2 in left slow/right fast and left fast/right slow compared with the intact state but recovered at H7-8. In left fast/right slow, LH step length significantly increased at H1-2 and remained increased at H7-8 compared with the intact state. In the same condition, LF step length significantly increased at H7-8.

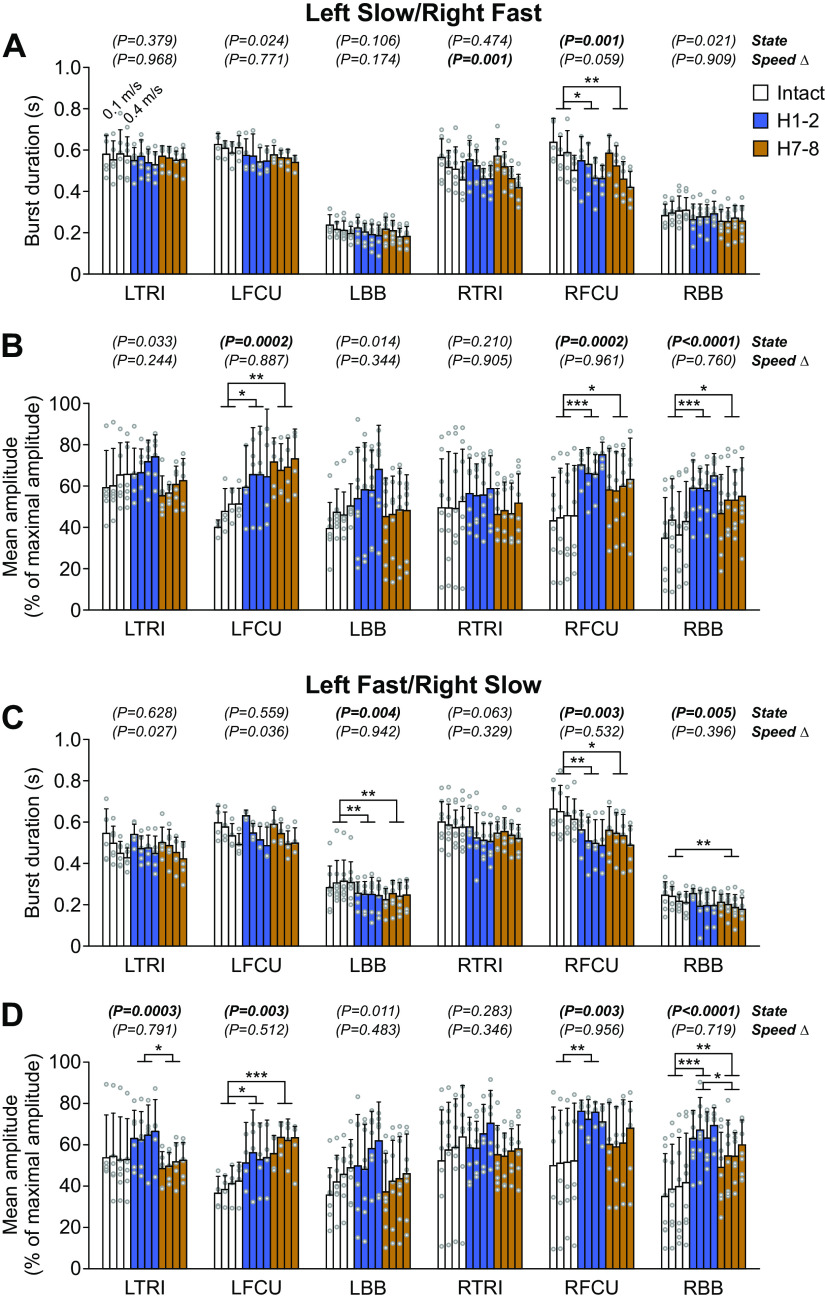

Adjustments in Muscle Activity after Lateral Hemisection during Split-Belt Locomotion

Our last research question was to determine changes in muscle activity after hemisection and their modulation by split-belt locomotion. We measured burst duration from onset to offset and mean EMG amplitude in fore- and hindlimb muscles before and after hemisection in both split-belt conditions.

Forelimbs.

Table 5 summarizes the results of pairwise comparisons and significant % differences between intact, H1-2, and H7-8. For the forelimbs (Fig. 10), burst duration significantly decreased after hemisection compared with the intact state for RFCU in both split-belt conditions at H1-2 and at H7-8 in left slow/right fast and in left fast/right slow) and for LBB at H1-2 and at H7-8 and RBB only at H7-8 in left fast/right slow.

Table 5.

Burst duration and amplitude of forelimb muscles before and after a lateral hemisection during split-belt locomotion

| Left Slow/Right Fast |

Left Fast/Right Slow |

Left Slow/Right Fast |

Left Fast/Right Slow |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Amplitude | Duration | Amplitude | Duration | Amplitude | Duration | Amplitude | ||

| LTRI | RTRI | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | H1-2 vs. Intact | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | H7-8 vs. Intact | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | H7-8 vs. H1-2 | ||||||||

| LFCU | RFCU | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0098 | 0.0071 | H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0036 | <0.0001 | 0.0009 | 0.0008 | ||

| +33.38% | +34,85% | −13.85% | +54.59% | −19.59% | +45.30% | ||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0002 | 0.0044 | 0.0010 | 0.2552 | ||

| +47.83% | +54.27% | −13.72% | +33.27% | −16.97% | |||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.4673 | 0.3107 | H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.7872 | 0.0982 | 0.8794 | 0.0346 | ||

| LBB | RBB | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0042 | H1-2 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | 0.0658 | <0.0001 | ||||

| −17.34% | +52.77% | +69.30% | |||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0019 | H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0016 | 0.0009 | 0.0006 | ||||

| −19.99% | +31.92% | −14.62% | +40.55% | ||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.0534 | 0.4322 | 0.0045 | |||||

| −16.98% | |||||||||

The table shows the results of pairwise comparisons when a significant main effect was found and significant % differences between intact, 1–2 wk (H1-2) and 7–8 wk (H7-8) for left (L) and right (R) forelimbs muscles. BB, biceps brachii; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; TRI, triceps brachii.

Figure 10.

Modulation of forelimb electromyography (EMG) burst durations and amplitudes during quadrupedal split-belt locomotion in intact cats and after a spinal hemisection across speeds. The figure shows burst durations (A and C) and amplitudes (B and D) for left (L) and right (R) muscles of forelimb for each speed Δ and each state. Data are presented as means ± SD and individual points. For each speed Δ, we averaged 9–15 cycles per cat (n = 9 cats; 4 females and 5 males). In A and B, the left side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the right side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. In C and D, the right side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the left side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. P values comparing states (State) and speed Δ (main effects of repeated-measures ANOVA) are indicated. Asterisks indicate significant difference between state (pairwise comparison): *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001. BB, biceps brachii; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; TRI, triceps brachii.

Mean EMG amplitude increased after hemisection compared with the intact state in both split-belt conditions for LFCU at H1-2 and at H7-8, in left slow/right fast at H1-2 and H7-8 for RFCU but only at H1-2 in left fast/right slow. It also increased in both split-belt conditions at H1-2 and H7-8 for RBB.

Hindlimbs.

Table 6 summarizes the results of pairwise comparisons and significant % differences between intact, H1-2, and H7-8. For the hindlimbs (Fig. 11), burst duration significantly increased compared with the intact state in both split-belt conditions at H7-8 for LBFA but only in left fast/right slow at H1-2 and in both split-belt conditions at H1-2 and H7-8 for RST. For LVL it increased at H7-8 in left slow/right fast while for LST it increased at H1-2 and H7-8 in left fast/right slow. In contrast, burst duration significantly decreased after hemisection compared with the intact state for RSRT in left slow/right fast at H1-2 and H7-8.

Table 6.

Burst duration and amplitude of hindlimbs muscles before and after a lateral hemisection during split-belt locomotion

| Left Slow/Right Fast |

Left Fast/Right Slow |

Left Slow/Right Fast |

Left Fast/Right Slow |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Amplitude | Duration | Amplitude | Duration | Amplitude | Duration | Amplitude | ||

| LBFA | RBFA | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0169 | 0.0070 | H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0060 | 0.0150 | <0.0001 | |||

| +9.53% | −42.85% | −47.17% | |||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0004 | 0.0006 | H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.7176 | 0.9303 | 0.0205 | |||

| +21.43% | +11.49% | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.1286 | 0.9290 | H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.1628 | 0.0079 | 0.0079 | |||

| +18.11% | +54.14% | ||||||||

| LVL | RVL | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.1471 | H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0029 | 0.1526 | <0.0001 | ||||

| +38.82% | +48,64% | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0008 | H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0018 | 0.0514 | 0.0966 | ||||

| +13.07 % | +42.18% | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.0928 | H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.9753 | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | ||||

| +18.62% | −20.96% | ||||||||

| LLG | RLG | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0996 | H1-2 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | 0.0015 | |||||

| +32.93% | +28.73% | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0067 | H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0011 | 0.0959 | |||||

| −41.01% | +29.84% | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.6636 | H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.0225 | 0.0746 | |||||

| LSRT | RSRT | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | H1-2 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| −26.60% | −34.91% | ||||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | H7-8 vs. Intact | 0.0011 | 0.0821 | ||||||

| −15.54% | |||||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.0292 | 0.0031 | ||||||

| +32.71% | |||||||||

| LST | RST | ||||||||

| H1-2 vs. Intact | 0.0006 | H1-2 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | 0.0033 | |||||

| +47,02% | +105.79% | +50.24% | |||||||

| H7-8 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | H7-8 vs. Intact | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| +52.68% | +89.74% | +61.07% | |||||||

| H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.7545 | H7-8 vs. H1-2 | 0.6217 | 0.7029 | |||||

The table shows the results of pairwise comparisons when a significant main effect was found and significant % differences between intact, 1–2 wk (H1-2) and 7–8 wk (H7-8) for left (L) and right (R) hindlimb muscles. BFA, biceps femoris anterior; LG, lateral gastrocnemius; SRT, anterior sartorius; ST, semitendinosus; VL, vastus lateralis.

Figure 11.

Modulation of hindlimb electromyography (EMG) burst durations and amplitudes during quadrupedal split-belt locomotion in intact cats and after a spinal hemisection across speeds. The figure shows burst durations (A and C) and amplitudes (B and D) for left (L) and right (R) muscles of hindlimb for each speed Δ and each state. Data are presented as means ± SD and individual points. For each speed Δ, we averaged 9–15 cycles per cat (n = 9 cats; 4 females and 5 males). In A and B, the left side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the right side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. In C and D, the right side was stepping at a constant treadmill speed of 0.4 m/s while the left side stepped at treadmill speeds of 0.5–0.8 m/s in 0.1 m/s increments. P values comparing states (State), speed Δ, and interaction between states and speed (State × Δ), (main effects of repeated measures ANOVA) are indicated. Asterisks indicate significant difference between state (pairwise comparison): *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001. BFA, biceps femoris anterior; LG, lateral gastrocnemius; SRT, anterior sartorius; ST, semitendinosus; VL, vastus lateralis.

Mean EMG amplitude significantly increased after hemisection compared with the intact state in both split-belt conditions for RVL and RLG at H1-2 while it increased at H7-8 only in left slow/right fast. Mean EMG amplitude significantly decreased after hemisection at H1-2 compared with the intact state for RSRT in left slow/right fast and in both split-belt conditions for RBFA. Thus, in hindlimb muscles that showed a decrease at H1-2, mean EMG amplitude recovered at H7-8, with values not significantly different from the intact state.

DISCUSSION

Changes in the Gait Pattern after Hemisection and Their Modulation by Split-Belt Locomotion

A lateral hemisection disrupts ascending and descending spinal pathways on one side. This includes descending supraspinal motor pathways going to lumbar levels, ascending sensory pathways going to the brain/cervical cord, and propriospinal pathways that communicate between cervical and lumbar levels. However, performing a perfect hemisection is technically challenging and lesion extent varies between animals. The most noticeable change in the gait pattern after hemisection is the appearance of 2:1 fore-hind coordination in four cats (cats CC, KA, MB, SA), all with greater than 50% of the spinal cord lesioned (Fig. 2). In these cats, the lesion extended to the left half of the spinal cord, disrupting part of the left dorsal columns as well as the left medioventral quadrant for two cats (CC and SA). Thus, the right reticulo- and vestibulospinal pathways were completely destroyed, as well as part of the left ones.

The appearance of 2:1 fore-hind coordination appears to depend on lesion extent and not damage to any particular pathway (73). Indeed, it has been shown in rats and cats following various thoracic lesions, such as lateral hemisections (44, 69, 71), bilateral ventral spinal lesions (63, 64, 66, 68, 70), and bilateral lesions to the dorsal columns (64, 65, 67, 74, 75). It is possible that the appearance of 2:1 fore-hind coordination requires damage extending to the contralesional (left) side. However, we can easily induce 2:1 fore-hind coordination in intact cats on a transverse split-belt treadmill by having the forelimbs step at a faster speed than the hindlimbs (76). Thibaudier et al. (44) proposed that the appearance of 2:1 coordination is a strategy to maximize the polygon of support during locomotion and reduce interference between homolateral fore- and hindlimbs.

Interestingly, we showed that the proportion of 2:1 coordination increased from early (H1-2) to late (H7-8) time points after hemisection in the left slow/right fast condition. This increase might be due to changes in neural pathways that communicate between spinal locomotor central pattern generators (CPGs) controlling the fore- and hindlimbs over time after the hemisection. Górska et al. (65) suggested that this compensatory strategy results from reduced inhibition of the forelimb CPG by the hindlimb CPG. Ascending inhibitory pathways from lumbar to cervical levels have been shown in rats and cats (77, 78). Sławińska et al. (79) recently showed that 2:1 fore-hind coordination appeared after blocking 5-HT7 receptors, but not 5-HT2A receptors, in intact rats. Thus, modulating serotonergic spinal pathways appears to play a role in the appearance of 2:1 coordination. A lateral hemisection certainly disrupts serotonergic projections and further investigations are required to assess the role of other pathways/neurotransmitter systems.

Despite the appearance of 2:1 fore-hind coordination, the locomotor movements at the shoulder and hip girdles remained coordinated. Indeed, phase intervals, even with 2:1 fore-hind coordination, remained clustered around specific values before and after hemisection in both split-belt conditions, as shown previously in cats with a lateral hemisection stepping overground (32) or during transverse split-belt locomotion (44), confirmed by Rayleigh’s test for circular statistics (Fig. 6 and Table 3). In spinal cats, we recently observed large variations of homolateral phase intervals during quadrupedal locomotion (80). Impaired fore-hind coordination in spinal cats is undoubtedly because of the absence of communication between networks controlling the forelimbs and hindlimbs (73). Thibaudier et al. (44) also showed that the step-by-step consistency of 2:1 fore-hind coordination increased by having the forelimbs step faster than the hindlimbs on transverse split-belt locomotion. Increased forelimb speed undoubtedly alters somatosensory feedback and its interactions with descending pathways and the forelimb CPG, which in turn can strengthen neural communication with the lumbar CPG. We did observe a shift in phase interval for left and right homolateral limbs in the left slow/right fast condition at H7-8 compared with intact and/or H1-2 time points (Fig. 7). This greater interval of time between contact of the forelimb relative to the hindlimb when the contralesional side is stepping on the slow belt can explain the decrease in triple support periods involving the two hindlimbs (Fig. 5). Despite some significant phase shift in the left slow/right fast condition, phase intervals remained clustered around the mean with r values of Rayleigh’s test above 0.80 (Table 3).

Both the lateral hemisection and split-belt locomotion induce asymmetries in the gait pattern. In the present study, we used slow-fast speeds during split-belt locomotion whereby homologous limbs maintained a 1:1 left-right coordination in intact and spinal cats (12–14). This 1:1 left-right coordination was maintained after hemisection in both split-belt conditions. To maintain 1:1 left-right coordination after hemisection, the slow and fast limbs adjusted their swing and stance durations bilaterally similarly to what was observed in the intact state. With larger left-right speed differences, intact and spinal cats can perform 1:2+ coordination patterns between the slow and fast sides (8, 9, 13, 21) where the hindlimb on the fast belt takes two or more steps for every step of the slow side. Human infants also spontaneously perform 1:2+ coordination patterns with sufficiently high slow-fast speed differences while adults maintain a 1:1 coordination (10, 19, 20). We did not test higher slow-fast speed ratios after hemisection in the present study.

Forelimb cycle duration decreased after hemisection in both split-belt conditions due to a reduction in stance and swing durations (Fig. 4, Table 1). Hindlimb cycle duration did not change significantly after hemisection but RH stance duration decreased 1–2 wk after hemisection before recovering at 7–8 wk. The decrease in RH stance duration paired with an increase in RH swing duration and a decrease in LH swing duration. These temporal adjustments helped maintain 1:1 coordination between the left and right sides, with hemisection the likely factor as they occurred in both split-belt conditions. Several studies have reported a reduction in the stance duration of the ipsilesional hindlimb coupled with an increase in its swing duration in cats following a thoracic lateral hemisection (33, 34, 69, 81, 82). These temporal adjustments likely serve to favor the contralesional hindlimb for support.

The hemisection also affected the horizontal distance of the foot at liftoff and contact in the ipsilesional hindlimb in both split-belt conditions (Fig. 8). At liftoff, the right hindlimb traveled further back relative to the hip before swing onset and made contact less rostral (closer to the hip). This less rostral placement, also reported by others after lateral hemisection in cats (36, 81, 83, 84) contributed to reduced step and stride lengths in the right hindlimb in both split-belt conditions (Fig. 9). These changes are consistent with impaired or altered activation of flexor muscles. Indeed, burst duration and amplitude of the right SRT (a main hip flexor) were reduced after hemisection in left slow/right fast (Fig. 11). Horizontal distance at contact, step and stride lengths returned toward intact values 7–8 wk after hemisection. Interestingly, right forelimb step and stride lengths also decreased after hemisection in both split-belt conditions with some recovery 7–8 wk later (Fig. 9) without affecting the horizontal distance at liftoff and contact. These adjustments in the right forelimb likely serve to maintain coordination between the right fore- and hindlimb. After thoracic hemisection on the right side, there is undoubtedly a loss of proprioception from the right hindlimb to the right forelimb and to the brain. Smaller forelimb steps might be a voluntary strategy to avoid interference between the right fore- and hindlimbs, as cats have reduced ability to perceive the position of the right hindlimb.

Modulations with Increasing Slow-Fast Speed Differences Are Maintained after Hemisection

In the present study, we used slow-fast speed differences from 0.1 m/s to 0.4 m/s. Several spatiotemporal and EMG variables were significantly modulated by speed Δ. For example, stance durations decreased with increasing speed Δ for the fore- and hindlimbs stepping on the fast belt, whereas stance durations of the limbs stepping on the slow belt did not change (Fig. 4). Swing durations showed an opposite pattern, decreasing with increasing speed Δ for the limbs stepping on the slow belt. Swing durations did not change with increasing speed Δ for the limbs stepping on the fast belt. Stride length also increased with increasing speed Δ for the fore- and hindlimbs when stepping on the fast belt (Fig. 9).

One notable difference between split-belt conditions is that stride length significantly decreased with increasing speed Δ for the right fore- and hindlimbs when stepping on the slow belt. On the other hand, step length did not change with increasing speed Δ for the four limbs in the two split-belt conditions. Shorter step lengths have been associated with greater stability and reduced risk of falling in older adults (85). Thus, maintaining step length after hemisection could be one strategy to reduce the risk of falling.

Most spatiotemporal adjustments to split-belt locomotion were maintained after hemisection, and we did not find any significant interactions between state and speed Δ. Intact and spinal cats show similar spatiotemporal adjustments during split-belt locomotion (11, 13, 21), consistent with a predominant role of sensory feedback from the limbs interacting with spinal networks (reviewed in Ref. 72).

Support Periods Change after Hemisection and Are Modulated by Split-Belt Locomotion

Support periods vary throughout the cycle to optimize balance and propulsion, with two, three, or four legs contacting the surface at any one time. The present study showed modifications in support periods after lateral hemisection, with some changes depending on the split-belt condition (Fig. 5). In both split-belt conditions, the triple support period that included the hindlimbs and the left forelimb decreased after hemisection, which was accompanied by an increase in quad support and the diagonal periods with one hindlimb and one forelimb stepping on the slow and fast belts, respectively (LH-RF in left slow/right fast and RH-LF in left fast/right slow). The triple support with both hindlimbs and the right forelimb also decreased after hemisection in left slow/fast, as did the right homolateral support period in left fast/right slow. What is the benefit of these changes to the gait pattern after hemisection and why were they affected by split-belt locomotion? The increase in quad support, as reported by others following incomplete thoracic SCI in cats (64, 69, 86) maximizes balance by increasing the area, or polygon, of support (87). The increase in diagonal support periods after hemisection is less intuitive, as these are the least stable support periods when stepping in the forward direction (88). This increase in diagonal support occurred when one forelimb stepped on the fast belt and one hindlimb on the slow belt and may be related to a change in posture of the animal. Lowering the hip girdle was shown to correlate with a greater proportion of diagonal support in cats (89). With the ipsilesional hindlimb stepping on the fast belt (left slow/right fast), we also observed a decrease in the triple support period with the two hindlimbs and the right forelimb and an increase in the triple support period with the two forelimbs and the left hindlimb. This reduces the contact time of the right hindlimb, maximizing support time of the other limbs.

Mechanisms Involved in the Recovery or Maintenance of Locomotion after Hemisection