Abstract

Among the various comorbidities potentially worsening the clinical outcome in patients hospitalized for the acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), hypertension is one of the most prevalent. However, the basic mechanisms underlying the development of severe forms of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among hypertensive patients remain undefined and the direct association of hypertension with outcome in COVID-19 is still a field of debate.

Experimental and clinical data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection promotes a rise in blood pressure (BP) during the acute phase of infection. Acute increase in BP and high in-hospital BP variability may be tied with acute organ damage and a worse outcome in patients hospitalized for COVID-19. In this context, the failure of the counter-regulatory renin-angiotensin-system (RAS) axis is a potentially relevant mechanism involved in the raise in BP. It is well recognized that the efficient binding of the Spike (S) protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors mediates the virus entry into cells. Internalization of ACE2, downregulation and malfunction predominantly due to viral occupation, dysregulates the protective RAS axis with increased generation and activity of angiotensin (Ang) II and reduced formation of Ang1,7. Thus, the imbalance between Ang II and Ang1–7 can directly contribute to excessively rise BP in the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection. A similar mechanism has been postulated to explain the raise in BP following COVID-19 vaccination (“Spike Effect” similar to that observed during the infection of SARS-CoV-2). S proteins produced upon vaccination have the native-like mimicry of SARS-CoV-2 S protein's receptor binding functionality and prefusion structure and free-floating S proteins released by the destroyed cells previously targeted by vaccines may interact with ACE2 of other cells, thereby promoting ACE2 internalization and degradation, and loss of ACE2 activities.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Blood pressure, Hypertension, Vaccines, COVID-19 vaccination, ACE2, Renin-angiotensin system, Spike protein

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Data accrued over the last 2 years reported that specific comorbidities are associated with increased risk of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and worse outcomes with development of increased severity of lung injury and mortality [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

The most frequent comorbidity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is hypertension [1], [2], [3]. Despite some reports seem to support the notion that hypertension represents a risk factor for susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, a more severe course of COVID-19, and increased COVID-19-related deaths [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], the exact mechanisms explaining the development of severe forms of COVID-19 among hypertensive patients remain undefined.

Recent investigations demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection may promote a significant rise in blood pressure (BP) during the acute phase of infection [14], [15], [16], [17] and that in-hospital acute increase of BP and the development of high BP variability might be associated with acute organ failure and unfavorable outcome in patients with COVID-19 [16].

More recently, reports on safety of COVID-19 vaccines included a significant rise in BP following vaccination as potential adverse reaction [18], [19], [20]. In this context, some investigations argued a specific effect of COVID-19 vaccines on the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) as mediated by the interaction between free floating Spike (S) proteins produced upon vaccination and angiotensin (Ang) converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors (the “Spike effect) [18,20,21].

The main aim of our narrative review was to summarize available evidences on the effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccines on BP. For this purpose, we identified clinical and experimental studies according to established methods [22,23]. Literature searches were conducted using Google Scholar, Scopus, PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases. We searched for eligible studies using research Methodology Filters [22,23]. The following research terms were used: “COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, blood pressure, hypertension, high blood pressure, vaccines, and vaccination”.

2. SARS-CoV-2 infection and blood pressure

Several comorbidities may worsen the clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized for SARS-CoV-2 [6,7,9,10]. Among risk factors that have been linked with COVID-19 [24], hypertension is one of the most common [6], [7], [8], [9], [10] and its direct association with outcome in COVID-19 is a field of debate [3,25,26]. A systematic overview and meta-analysis of 7 clinical studies analyzing data of 1576 COVID-19 patients demonstrated that the most prevalent comorbidity was hypertension (21.1%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 13.0–27.2%) [27]. Furthermore, hypertension was associated with an increased risk of severe COVID-19 (odds ratio [OR]: 2.49; 95% CI: 1.98–3.12) and death (OR: 2.42; 95% CI: 1.51–3.90) [28].

On the other hand, in-hospital acute rise in BP and increased BP variability are frequently observed during hospitalization for COVID-19 and they seem to be significant independent predictors of bad outcome in COVID-19 patients [14,15]. More specifically, an observational clinical study in COVID-19 showed that an exaggerated cardiovascular response due to persistently elevated and unstable BP occurring during hospitalization are independently associated with in-hospital death, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and worsening heart failure [14]. In this retrospective cohort study involving 803 hypertensive patients, 8.3% were admitted to ICU, 3.7% had respiratory failure, 3.2% had heart failure, and 4.8% died. After adjustment for several confounders, average systolic BP (hazard ratio [HR] per 10 mmHg: 1.89; 95% CI: 1.15-3.13) and pulse pressure (HR per 10 mmHg: 2.71; 95% CI: 1.39-5.29) were independent predictors of heart failure. Moreover, the standard deviations of systolic and diastolic BP were independently associated with mortality and ICU admission.

To investigate the effect of COVID-19 on BP during short term follow-up, Akpek and co-workers [29] analyzed data of 153 consecutive COVID-19 patients. Mean age of study population was 47 ± 13 years and the main study outcome was the development of new onset hypertension according to current Guidelines [29]. Both systolic (121 ± 7 mmHg vs 127 ± 15 mmHg, p<0.001) and diastolic BP (79 ± 4 vs 82 ± 7 mmHg, p <0.001) were significantly higher in the post COVID-19 period than on admission. Notably, a new diagnosis of hypertension was observed in 18 patients at the end of the observation [29].

Similarly, the clinical data of 366 hospitalized COVID-19-confirmed patients without prior hypertension showed an incidence of rise in BP during hospitalization equal to 8.42%, with a significantly increased level of troponin, procalcitonin, and Ang II [30].

More recently, a prospective case-control study from our group analyzed BP changes among hospitalized patients with confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

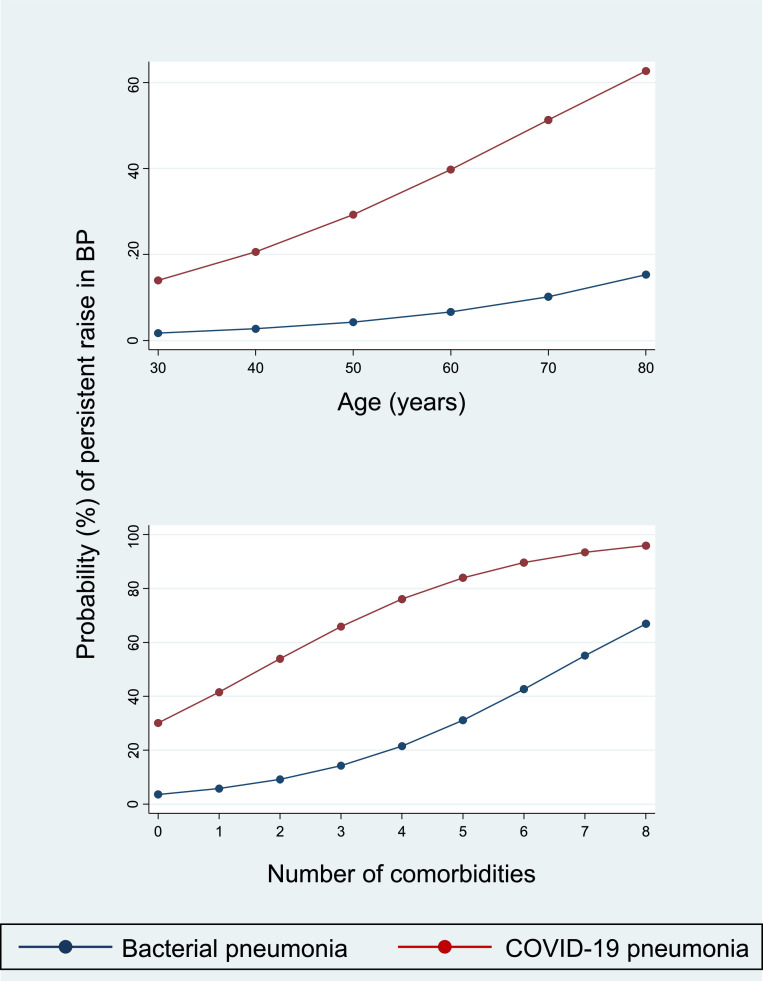

The infection was established by RNA reverse-transcriptase-polimerase-chain-reaction (PCR) assays from nasopharyngeal swab specimens. All patients had imaging features for COVID-19 pneumonia. The clinical outcome was the development of a persistent increase in BP (as defined by BP values ≥ 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic for at least two consecutive days) requiring a new or intensified anti-hypertensive treatment during hospitalization [17]. A control group of patients with bacterial pneumonia (diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection were negative along the entire hospitalization period) was also enrolled and used to analyze the differences in BP with COVID-19 pneumonia. Notably, age, BP at admission, main clinical features and in-hospital management, demographic data, and prevalence of risk factors and comorbidities were similar between cases with COVID-19 pneumonia and controls with bacterial pneumonia. Systolic (126 vs 118 mmHg, p = 0.016) and diastolic (79 vs 70 mmHg, p<0.0001) BP values recorded during the acute phase were significantly different between the two groups. Overall, a persistent increase in BP was detected in 28 patients. Specifically, 25 and 3 patients met the primary endpoint among COVID-19 and bacterial pneumonia, respectively (p = 0.001). Estimating the effects of covariates with multivariable regression models, COVID-19 pneumonia was associated with a 7-fold higher risk of uncontrolled hypertension when compared with bacterial pneumonia (OR: 6.99; 95% CI: 1.89 to 25.80; p = 0.004), even after adjustment for confounders (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Probability of persistent raise in BP during hospitalization for COVID-19 according to type of pneumonia, age, and number of comorbidities (see text for details). Legend: BP=blood pressure.

Results of the aforementioned clinical studies support the notion that a significant increase in BP may be used to identify patients at increased risk of adverse outcome when recorded in the early phase of hospitalization. Indeed, the development of severe forms of COVID-19 may be linked to hypotension, as recorded during acute heart failure, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmias. Other clinical conditions (including fever, dehydration, acute kidney injury, in-hospital over-infections, weight loss, physical inactivity, and acute respiratory failure) may affect BP values [9,13,31].

3. Raise in blood pressure following COVID-19 vaccination

After the first report by Meylan and co-workers who described a case series of 9 patients (8 were symptomatic) with stage III hypertension following COVID-19 vaccination [32], a number of studies evaluated the rate of increased BP as potential adverse reaction to vaccination.

Sanidas and co-workers [33] evaluated the effects of COVID-19 vaccination on BP in patients with history of controlled hypertension (defined as systolic/diastolic BP <140/90 mmHg) and healthy controls. Overall, 100 patients were enrolled [33]. All patients had BP measurements (both home and ambulatory) between the 5th and the 20th day after fully COVID-19 vaccination [33]. Patients with history of controlled hypertension showed a mean home and 24-h ambulatory BP equal to 175/97 mmHg and 177/98 mmHg, respectively [24]. Moreover, healthy controls showed a home BP of 158/96 mmHg and a 24-h ambulatory BP equal to 157/95 mmHg [33].

Ch'ng and coworkers [34] evaluated 4906 healthcare workers, recording BP when the staff members arrived at the vaccination site, immediately after vaccination, and 15–30 min later. Mean pre-vaccination systolic/diastolic BP was 130.1/80.2 mmHg and the mean changes after vaccination were +2.3/+2.4 mmHg for systolic/diastolic BP [34].

Pharmacovigilance databases were also used to evaluate this phenomenon, showing proportions of abnormal or increased BP after vaccination ranging from 1% to 3% [35], [36], [37]. Among these, a retrospective analysis involving 21,909 subjects, exhibited the largest proportion of this phenomenon [38]. Specifically, Bouhanick and co-workers investigated the BP profile of vaccinated patients and healthcare workers after the first and the second dose of COVID-19 vaccine [38]. Overall, 8121 subjects (37%) exhibited systolic and/or diastolic BP above 140 and/or 90 mmHg after the first dose. Interestingly, the majority (64%) of subjects with abnormal BP after the first injection showed a persistent abnormal BP after the second one [38].

Surveys specifically designed to evaluate BP changes following vaccination showed an incidence of raise in BP after COVID-19 vaccination ranging from 1% to 5% (5% in the analysis by Tran and co-workers [39] and Zappa and co-workers [40], and about 1% among subjects enrolled in the study by Syrigos and co-workers [41]). Just recently, Simonini and co-workers evaluated data from a large cohort of 1866 vaccinated healthcare workers [42]. They documented a BP increase in 153 subjects (8%) [42]. BP alterations presented with greater frequency at the 2nd or booster dose [42]. Furthermore, in 39 subjects (2%) a diagnosis of hypertension was done after vaccination, and among subjects already on antihypertensive therapy, 11% had to increase therapy [42]. The same Authors also recorded a significant proportion (4%) of subjects reporting a decrease in BP [42]. Nonetheless, the lack of definition and magnitude of BP decrease does not permit to evaluate the influence of conditions such as masked hypertension [42].

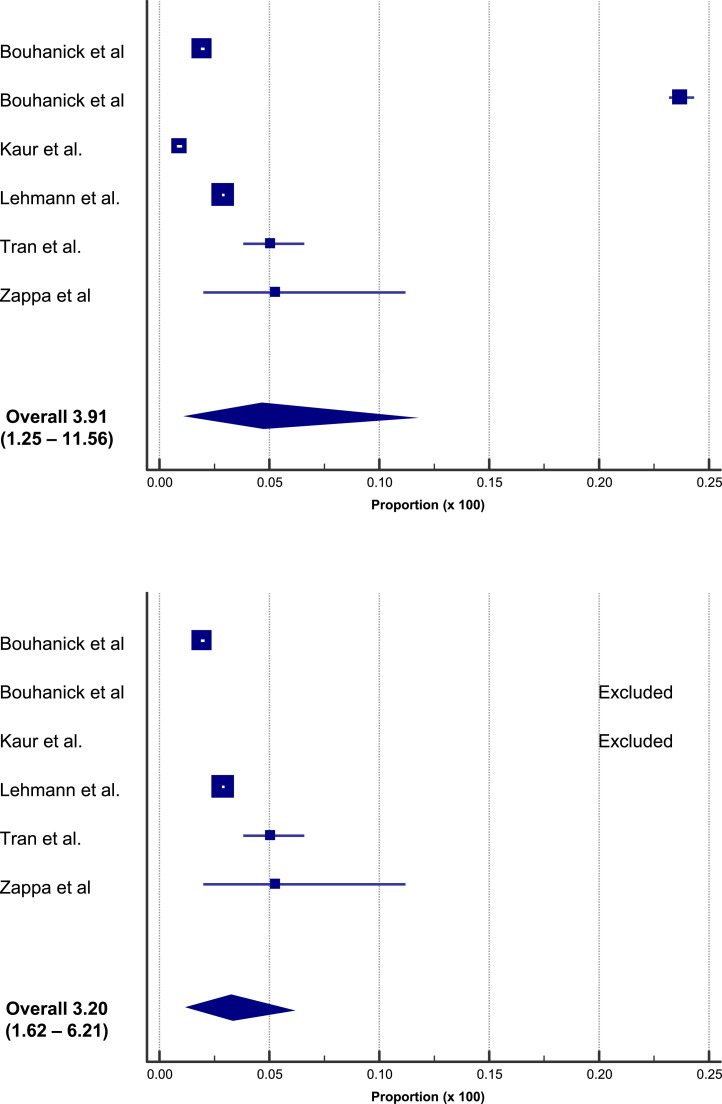

A systematic overview and meta-analysis including 6 studies (for a total of 357,387 subjects and 13,444 events) showed a pooled estimated proportion of abnormal/increased BP after vaccination equal to 3.91% (95% CI: 1.25 – 11.56, Fig. 2 – upper panel). A similar pooled proportion (3.20%; 95% CI: 1.62 – 6.21) was computed after the exclusion of 2 studies identified as statistical outliers (Fig. 2, lower panel) [21]. Notably, the proportion of cases of clinically significant increase in BP (stage III hypertension, hypertensive urgencies, and hypertensive emergencies) was 0.6% [21].

Fig. 2.

Proportions of increased BP after vaccination in a meta-analysis of 6 studies, for a total of 357,387 subjects and 13,444 adverse events [21].

4. Mechanisms

4.1. The role of ACE2

Although hypertension seems to be linked to the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and acute elevations in BP during the acute phase of infection seem to be related with SARS-CoV-2 replication [14], the exact mechanism is still debated.

The failure of the counter-regulatory RAS axis, characterized by the decrease of generation of the protective Angiotensin1,7 (Ang1,7) and ACE2 receptors expression [43], [44], [45], appears to be the most relevant causative mechanism implicated in the raise of BP and worse outcome of COVID-19 [46], [47], [48], [49], [50]. Indeed, recent investigations demonstrated the development of an “Angiotensin II storm” [51] or “Angiotensin II intoxication” [52] during the acute phase of SARs-CoV-2 infection [10,16,46,47,53,54].

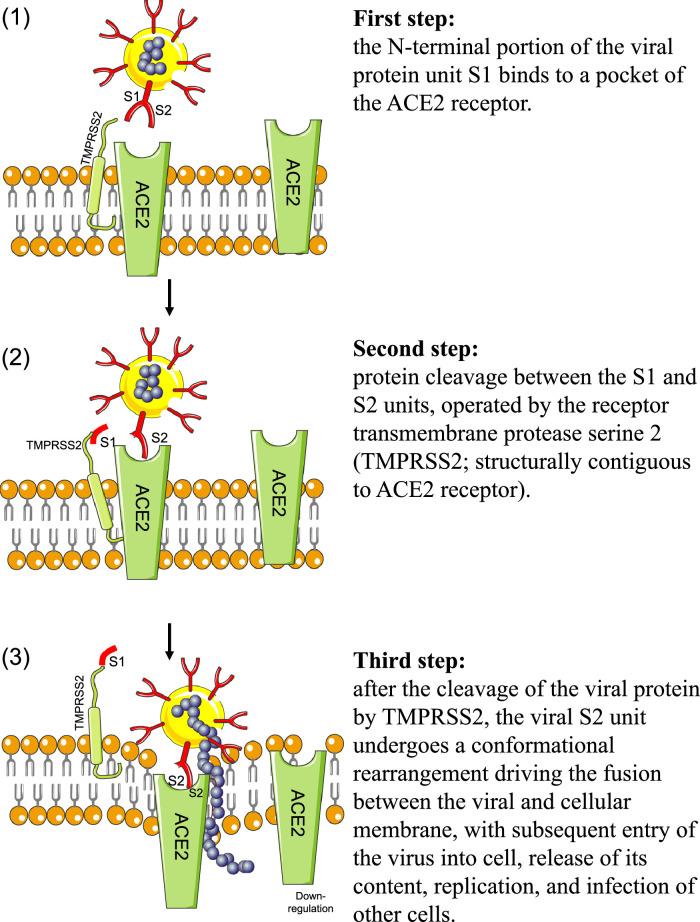

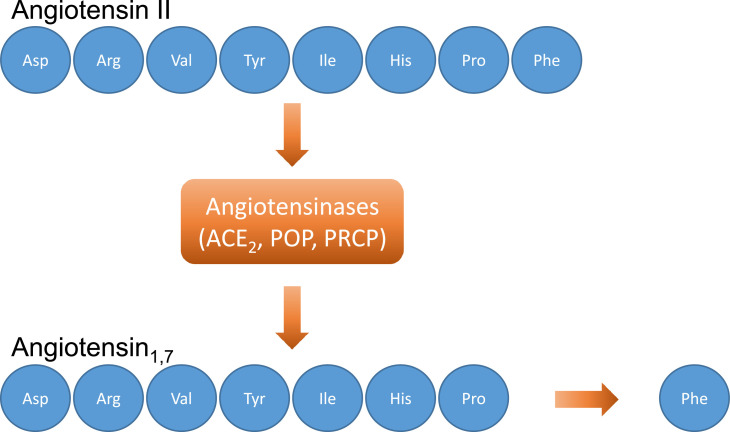

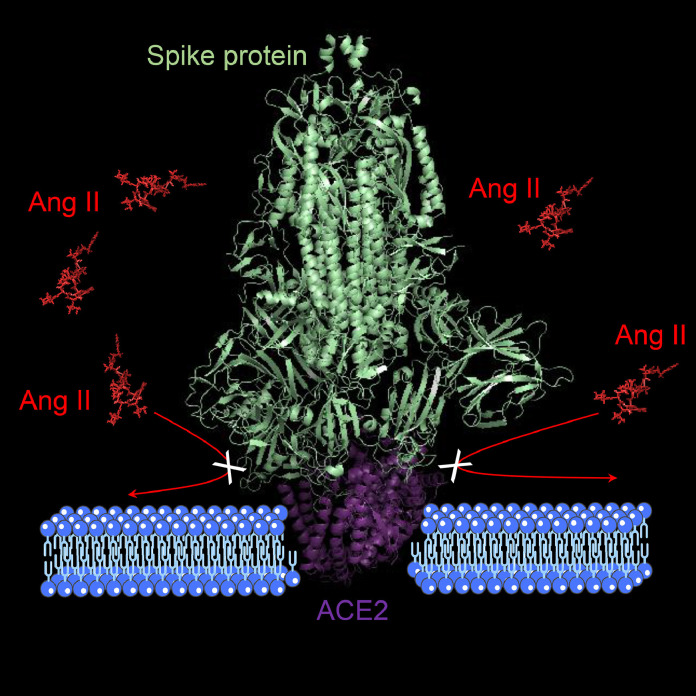

It is well recognized that the virus entry into cells is mediated by the efficient binding of the Spike (S) protein (which comprises S1 and S2 subunits) to ACE2 receptors (Fig. 3 ) [49,55]. ACE2 receptors are ubiquitary expressed in human tissues [56] and they are composed by 805 amino acids. ACE2 are responsible for the cleavage (using a single extracellular catalytic domain) of an amino acid from Ang I to form Ang1,9 and to remove an amino acid from Ang II to form Ang1–7 (Fig. 4 ) [57].

Fig. 3.

Steps of SARS-CoV-2 entry process. The main step after the invasion of SARS-CoV-2 is binding to membranal ACE2 receptor; see text for details. Legend: ACE2=angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor.

Fig. 4.

Angiotensin1,7 formation. Angiotensin1,7 is formed by the action of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (and other angiotensinases, including POP and PRCP) by the cleavage of an amino acid from Angiotensin II. Legend: ACE2=angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor; POP=prolyl oligopeptidase; PRCP=prolyl carboxypeptidases.

ACE2 downregulation/internalization, and malfunction predominantly due to viral occupation (as mediated by the binding between S proteins and ACE2), dysregulates the protective RAS axis with reduced formation of Ang1,7 and increased generation and activity of Ang II (Fig. 5 ) [46], [47], [48].

Fig. 5.

The effect of binding of the Spike protein to ACE2 on the dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin system with increased generation and activity of Ang II (loss of ACE2 activity). Legend: ACE2=angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor; Ang=angiotensin.

Notably, Ang II is directly involved in BP regulation and inflammatory pathways (which are both disturbed in COVID-19 [58], [59], [60]), and the imbalance between Ang II and Ang1–7 can directly contribute to development of high BP in the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection [19].

In this context, Wu and co-workers demonstrated a significant raise in Ang II levels among COVID-19 patients [61]. More specifically, they evaluated whether the plasmatic activity of Ang II is dysregulated in COVID-19 patients. They demonstrated increased Ang II levels in the majority (90%) of COVID-19 patients, and a direct association between plasma Ang II levels and COVID-19 severity [61].

Similar results were obtained in the aforementioned study by Chen and co-workers [30].

Furthermore a clinical study investigating disease severity in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, found that plasmatic Ang II levels were significantly increased and linearly associated with lung damage and viral load [62].

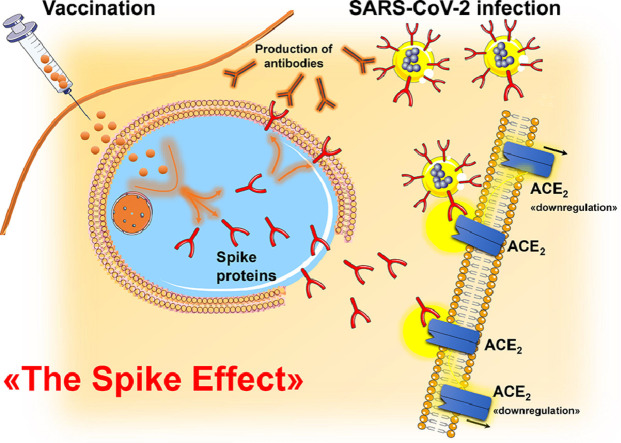

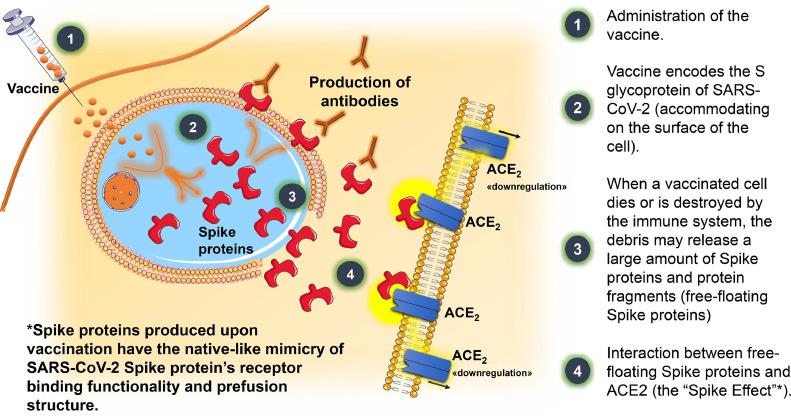

The picture is further complicated analyzing the phenomenon of raised BP following COVID-19 vaccination. However, a “Spike Effect” similar to that observed during the infection of SARS-CoV-2 may be postulated.

Recent observations demonstrated that S proteins produced upon vaccination have the native-like mimicry of SARS-CoV-2 S protein's receptor binding functionality and prefusion structure [20,63]. Free-floating S proteins released by the destroyed cells previously targeted by COVID-19 vaccines may interact with ACE2 receptors of other cells, thereby promoting degradation, internalization, and loss of catalytic activities of ACE2 receptors [20,64]. These mechanisms may enhance the imbalance between Ang II overactivity and Ang1–7 deficiency, contributing to an increase in BP (Fig. 6 ) [40,65].

Fig. 6.

Schematic mechanism of action of COVID-19 vaccines and their potential cardiovascular effects throughout the interaction between free-floating Spike proteins and ACE2 receptors. Legend: ACE2=angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor; SARS-CoV-2= severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2.

The role of RAS in the biology of COVID-19 support the hypothesis that its pharmacological modulation may favorably impact organ dysfunction and illness severity. After the concern at the beginning of the pandemic on the susceptibility to infection and disease severity enhanced by ACE-inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin type-1 receptor blockers (ARBs) [66], some reports provided data on the potential benefit of angiotensin receptor modulators in COVID-19 [67], [68], [69]. Just recently, a prospective study specifically tested the prognostic value of exposure to RAS modifiers among 566 hypertensive patients with COVID-19 [54]. During hospitalization 66 patients died and exposure to RAS modifiers was associated with a significant reduction (−46%, p = 0.019) in the risk of in-hospital mortality when compared to other BP-lowering strategies [54]. Exposure to ACE-Is was not significantly associated with a reduced risk of in-hospital mortality when compared with patients not treated with RAS modifiers; conversely, ARBs users showed a 59% lower risk of death (p = 0.016) even after allowance for several prognostic markers [54]. Furthermore, the discontinuation of RAS modifiers during hospitalization did not exert a significant effect (p = 0.515) [54].

Nonetheless, recent randomized trials consistently show neither benefit nor harm from inhibition of RAS [70], [71], [72]. Of note, these trials were conducted in patients with early, mild, or moderate disease and the role of RAS modulation in critically ill COVID-19 remains to be evaluated [70], [71], [72].

4.2. The role of other angiotensinases

In the last few years, other Ang1,7 forming enzymes have been identified [59]. To date, the Ang II-Ang1,7 axis of the RAS includes three carboxypeptidases forming by cleavage Ang1,7 from Ang II: ACE2, prolyl oligopeptidase (POP), and prolyl carboxypeptidases (PRCP) [59]. Specifically, POP cuts at the C-side of an internal proline and cleaves Ang I to form Ang1,7, and Ang II to form Ang1,7 [59,[73], [74], [75]]; similarly, PRCP cleaves the C-terminal amino acid of Ang II [76]. Notably, ACE2 is the main enzyme responsible for Ang II formation in the kidney; Ang1,7 formation in the lungs and circulation is mainly POP-dependent [59]; conversely, PRCP is ubiquitously expressed [77,78], regulating inflammation, oxidative stress, thrombosis, and vascular homeostasis [79], [80], [81] by stimulating the release of nitric oxide and prostaglandin [80,82,83].

Several experimental and clinical studies supported the detrimental role of POP and PRCP deficiency on BP. The genetic absence of POP directly affects BP response (due to the diminished Ang II degradation and Ang1,7 formation) [59,84] and the PRCP gene variant promotes disease progression in hypertensive patients [85]. Finally, PRCP depletion contributes to vascular dysfunction with hypertension and arterial thrombosis [86].

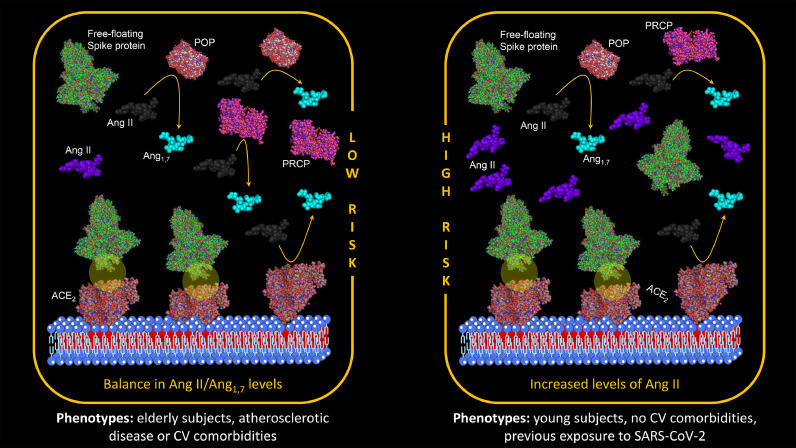

As aforementioned, phenotypes of ACE2 deficiency [43], [44], [45] (including older age, hypertension, diabetes, and previous vascular events) are associated with an increased risk of worse outcome in COVID-19 [1,9,12,[87], [88], [89], [90], [91]]. Conversely, accrued data on the RAS show that aging, inflammation, atherosclerosis, and the development of atherosclerotic risk factors and cardiovascular events are associated with an increased plasmatic activity of POP and PRCP [92,93]. Experimental and clinical studies demonstrated a significant positive association between POP/PRCP and several metabolic and cardiovascular parameters (including blood glucose, body mass index, body weight, and amount of total, visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue) [94,95]. Furthermore, intraplaque PRCP levels are upregulated in unstable atherosclerotic plaques compared with stable plaques [96].

In other words, in the cardiovascular disease continuum (from atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk factors to the development of cardiovascular events) specific changes of angiotensinanes levels exists [97]: in the disease continuum ACE2 activities decrease, whereas PRCP and POP levels increase from the health status to advanced deterioration of the cardiovascular system.

4.2.1. SARS-CoV-2 infection

In the specific area of BP regulation, POP and PRCP may play a specific role in COVID-19 [58], [59], [60]. Indeed, the activities of POP and PRCP remain substantially unchanged during the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, therefore failing to limit the accumulation of Ang II by ACE2 downregulation and malfunction. A clinical study by Bracke and co-workers investigated the plasma activities of PRCP and POP among patients at the time of hospital admission or during their hospital stay for COVID-19 [98]. The Authors documented that PRCP activity remained stable during hospitalization and did not differ from PRCP activity recorded in healthy controls. Finally, they also supported the recent hypothesis [99] that the elevated POP levels observed in plasma of patients COVID-19 originates from cell damage due to acute lung injury or organ failure [98].

4.2.2. COVID-19 vaccination

Loss of the catalytic activities of ACE2 due to the interaction between these receptors and free-floating S proteins is documented across all the strata of the cardiovascular disease continuum [19,20]. On the other hand, an increased catalytic activity of POP and PRCP is not observed in the young, but more typically pronounced in elderly subjects with comorbidities or previous cardiovascular events.

Thus, the potential adverse reactions to COVID-19 vaccination associated with Ang II accumulation (including increase in BP, enhanced inflammation, and thrombosis) are reasonably expected to be more common in younger and healthy subjects (Fig. 7 , right panel) [19,20]. Conversely, older age, presence of comorbidities and previous cardiovascular events identify phenotypes at lower risk of adverse events (Fig. 7, left panel).

Fig. 7.

Adverse reactions to COVID-19 vaccination associated with Ang II accumulation. Older age, presence of comorbidities and previous cardiovascular events identify phenotypes at lower risk of adverse events (left panel).Younger and healthy subjects are phenotypes at increased risk of adverse events (right panel). Legend: ACE2=angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor; Ang=angiotensin; CV=cardiovascular; POP=prolyl oligopeptidase; PRCP=prolyl carboxypeptidases; SARS-CoV-2= severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2.

This potential mechanism is supported by recent clinical and epidemiological studies evaluating the development of adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination.

In a prospective survey of 113 healthcare workers who received COVID-19 vaccine [40], 6 subjects (5.3%) developed an increase in systolic or diastolic BP at home ≥ 10 mmHg during the first five days after the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine when compared with the five days before the vaccine. Of note, age of patients with uncontrolled hypertension following COVID-19 vaccination ranged from 35 to 52 years [40].

Similarly, Tran and co-workers [39] demonstrated that age of vaccinated subjects was a significant predictor of increased BP after COVID-19 vaccination, as the increase of age was associated with the decrease of this adverse event [39].

In a study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Simone and co-workers evaluated the incidence of acute myocarditis and clinical outcomes among adults following mRNA vaccination in an integrated health care system in the US (Kaiser Permanente Southern California members) [100]. Among subjects who received COVID-19 mRNA, 54% were women and median age was 49 years [100]. The Authors identified 15 cases of post-vaccination myocarditis (2 after the first dose and 13 after the second) [100]. Of note, all cases occurred in men with a median age of 25 years [100].

Among 530 cases of myocarditis reported after COVID-19 vaccination to Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, approximately 65% of subjects were aged 12–24 years [101].

Schultz and co-workers reported findings in five patients in a population of more than 130,000 vaccinated persons who presented with venous thrombosis and thrombocytopenia after receiving the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 adenoviral vector vaccine) [102]. The patients were health care workers who were 32 to 54 years of age [102].

Similarly, other reports found that subjects with vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) were younger [103,104].

Finally, in a report from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, rates of VITT were similar between males and females in most age brackets, with the exception of females ages 30 to 49 years, in whom rates were higher [105].

5. Conclusions

Recent clinical and experimental advances in the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection support the notion that the interaction of the virus (mediated by S proteins) with ACE2 receptors exerts a pivotal role in the development of severe disease [47,53,106,107].

Recent findings further expanded our knowledge on the deleterious effect of Ang II accumulation. Downregulation and internalization of ACE2 receptors (due to viral occupation), and malfunction of other angiotensinases, dysregulates the protective RAS axis with increased generation and activity of Ang II and reduced formation of Ang1,7 [46], [47], [48].

Of note, Ang II plays key roles in BP homeostasis, including the heart, kidney, blood vessels, adrenal glands, and cardiovascular control centres in the brain [108]. Thus, the negative effect of SARS-CoV-2 on BP during and after the acute phase of infection is not entirely unexpected [17].

In this context, the association between increased levels of Ang II and increased BP during hospitalization for COVID-19 support this mechanism. Uncontrolled hypertension during the course of the disease can acutely worsen hypertension-mediated organ damage and adverse outcomes [16]

A similar mechanism has been recently proposed to explain the raise in BP following COVID-19 vaccination [19,20,109]. In other words, the resulting features of COVID-19 vaccination resemble those of active COVID-19 disease.

When vaccinated cells die or are destroyed by the human immune system, the debris may release a large amount of free-floating S proteins [20]. Having the native-like mimicry of SARS-CoV-2 S protein's receptor binding functionality and prefusion structure, S proteins produced upon vaccination may interact with ACE2 receptors, causing internalization, degradation [19,20], and loss of ACE2 activities.

These mechanisms may lead to less Ang II inactivation and Ang1,7 generation, with consequent Ang II overactivity which may trigger a variable raise in BP [46], [47], [48].

Stress response (white-coat effect) and the role of some excipients might explain the high prevalence of increased BP values recorded immediately after vaccination [21,32]. However, data from surveys and pharmacovigilance databases which expanded the observation some days after vaccination demonstrated that a persistent raise in BP after COVID-19 vaccination is not unusual [21,40]. Further research taking into account the potential effects of confounders and long-term clinical data are urgently needed in this area.

Footnotes

None of the authors of this study has financial or other reasons that could lead to a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S., et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 180:934–43. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiffrin E.L., Flack J.M., Ito S., Muntner P., Webb R.C. Hypertension and COVID-19. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:373–374. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitero A., Bungau S.G., Tit D.M., Endres L., Khan S.A., Bungau A.F. et al. Comorbidities, associated diseases, and risk assessment in COVID-19-A Systematic Review. Int J Clin Pract. 2022, 2022:1571826. 10.1155/2022/1571826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Justino D.C.P., Silva D.F.O., Costa K., de Morais T.N.B., de Andrade F.B. Prevalence of comorbidities in deceased patients with COVID-19: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022;101:e30246. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000030246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A., et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region. Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M., Crawford J.M., McGinn T., Davidson K.W., et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angeli F., Spanevello A., De Ponti R., Visca D., Marazzato J., Palmiotto G., et al. Electrocardiographic features of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;78:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angeli F., Verdecchia P., Reboldi G. RAAS Inhibitors and Risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1990–1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2030446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallo G., Calvez V., Savoia C. Hypertension and COVID-19: current Evidence and Perspectives. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2022;29:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s40292-022-00506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angeli F., Masnaghetti S., Visca D., Rossoni A., Taddeo S., Biagini F., et al. Severity of COVID-19: the importance of being hypertensive. Monaldi archives for chest disease = Archivio Monaldi per le malattie del torace. 2020;90 doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2020.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angeli F., Reboldi G., Spanevello A., De Ponti R., Visca D., Marazzato J., et al. Electrocardiographic features of patients with COVID-19: one year of unexpected manifestations. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;95:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ran J., Song Y., Zhuang Z., Han L., Zhao S., Cao P., et al. Blood pressure control and adverse outcomes of COVID-19 infection in patients with concomitant hypertension in Wuhan, China. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:1267–1276. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-00541-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saeed S., Tadic M., Larsen T.H., Grassi G., Mancia G. Coronavirus disease 2019 and cardiovascular complications: focused clinical review. J Hypertens. 2021;39:1282–1292. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angeli F., Verdecchia P., Reboldi G. Pharmacotherapy for hypertensive urgency and emergency in COVID-19 patients. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2022;23:235–242. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2021.1990264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angeli F., Zappa M., Oliva F.M., Spanevello A., Verdecchia P. Blood pressure increase during hospitalization for COVID-19. Eur J Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angeli F., Reboldi G., Trapasso M., Verdecchia P. [Hypertension after COVID-19 vaccination] G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2022;23:10–14. doi: 10.1714/3715.37055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angeli F., Reboldi G., Trapasso M., Zappa M., Spanevello A., Verdecchia P. COVID-19, vaccines and deficiency of ACE2 and other angiotensinases. Eur J Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.06.015. Closing the loop on the "Spike effect". [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angeli F., Spanevello A., Reboldi G., Visca D., Verdecchia P. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: lights and shadows. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angeli F., Reboldi G., Trapasso M., Santilli G., Zappa M., Verdecchia P. Blood Pressure Increase following COVID-19 Vaccination: a Systematic Overview and Meta-Analysis. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022;9 doi: 10.3390/jcdd9050150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes R.B., Kastner M., Wilczynski N.L., Hedges T. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound and relevant causation studies in EMBASE. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAuley L., Pham B., Tugwell P., Moher D. Does the inclusion of grey literature influence estimates of intervention effectiveness reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 2000;356:1228–1231. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02786-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Science Brief: evidence used to update the list of underlying medical conditions that increase a person's risk of severe illness from COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/underlying-evidence-table.html (Accessed on September 15, 2021). [PubMed]

- 25.Di Castelnuovo A., Bonaccio M., Costanzo S., Gialluisi A., Antinori A., Berselli N., et al. Common cardiovascular risk factors and in-hospital mortality in 3,894 patients with COVID-19: survival analysis and machine learning-based findings from the multicentre Italian CORIST Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30:1899–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swamy S., Koch C.A., Hannah-Shmouni F., Schiffrin E.L., Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J., Gubbi S. Hypertension and COVID-19: updates from the era of vaccines and variants. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2022;27 doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q., et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lippi G., Wong J., Henry B.M. Hypertension in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pooled analysis. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020;130:304–309. doi: 10.20452/pamw.15272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akpek M. Does COVID-19 Cause Hypertension? Angiology. 2022;73:682–687. doi: 10.1177/00033197211053903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen G., Li X., Gong Z., Xia H., Wang Y., Wang X., et al. Hypertension as a sequela in patients of SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS ONE. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vicenzi M., Di Cosola R., Ruscica M., Ratti A., Rota I., Rota F., et al. The liaison between respiratory failure and high blood pressure: evidence from COVID-19 patients. Eur Respir J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01157-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meylan S., Livio F., Foerster M., Genoud P.J., Marguet F., Wuerzner G., et al. Stage III Hypertension in Patients After mRNA-Based SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Hypertension. 2021;77:e56–ee7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanidas E., Anastasiou T., Papadopoulos D., Velliou M., Mantzourani M. Short term blood pressure alterations in recently COVID-19 vaccinated patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;96:115–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ch'ng C.C., Ong L.M., Wong K.M. Changes in Blood Pressure After Pfizer/Biontech Sars-Cov-2 Vaccination. ResearchSquare, 10.21203/rs3rs-1018154/v1. 2022. [DOI]

- 35.Bouhanick B., Montastruc F., Tessier S., Brusq C., Bongard V., Senard J.M., et al. Hypertension and Covid-19 vaccines: are there any differences between the different vaccines? A safety signal. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77:1937–1938. doi: 10.1007/s00228-021-03197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaur R.J., Dutta S., Charan J., Bhardwaj P., RTandon A., Yadav D., et al. Cardiovascular Adverse Events Reported from COVID-19 Vaccines: a Study Based on WHO Database. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:3909–3927. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S324349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehmann K. Suspected Cardiovascular Side Effects of two Covid-19 Vaccines. Journal of Biology and Today's World. 2021 doi: 10.31219/osf.io/gh9u2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouhanick B., Brusq C., Bongard V., Tessier S., Montastruc J.L., Senard J.M., et al. Blood pressure measurements after mRNA-SARS-CoV-2 tozinameran vaccination: a retrospective analysis in a university hospital in France. J Hum Hypertens. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41371-021-00634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tran V.N., Nguyen H.A., Le T.T.A., Truong T.T., Nguyen P.T., Nguyen T.T.H. Factors influencing adverse events following immunization with AZD1222 in Vietnamese adults during first half of 2021. Vaccine. 2021;39:6485–6491. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zappa M., Verdecchia P., Spanevello A., Visca D., Angeli F. Blood pressure increase after Pfizer/BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;90:111–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Syrigos N., Kollias A., Grapsa D., Fyta E., Kyriakoulis K.G., Vathiotis I., et al. Significant Increase in Blood Pressure Following BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: a Rare Event. Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simonini M., Scarale M.G., Tunesi F., Moro M., Serio C.D., Manunta P., et al. COVID-19 vaccines effect on blood pressure. Eur J Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abassi Z., Assady S., Khoury E.E., Heyman S.N. Letter to the Editor: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: an ally or a Trojan horse? Implications to SARS-CoV-2-related cardiovascular complications. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;318:H1080–H10H3. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00215.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gheblawi M., Wang K., Viveiros A., Nguyen Q., Zhong J.C., Turner A.J., et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2: sARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System: celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Discovery of ACE2. Circ Res. 2020;126:1456–1474. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang K., Gheblawi M., Oudit G.Y. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2: a Double-Edged Sword. Circulation. 2020;142:426–428. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.047049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Angeli F., Reboldi G., Verdecchia P. SARS-CoV-2 infection and ACE2 inhibition. J Hypertens. 2021;39:1555–1558. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verdecchia P., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verdecchia P., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., Angeli F. COVID-19: aCE2centric Infective Disease? Hypertension. 2020;76:294–299. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verdecchia P., Reboldi G., Cavallini C., Mazzotta G., Angeli F. ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by coronavirus. G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2020;21:321–327. doi: 10.1714/3343.33127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verdecchia P., Angeli F., Reboldi G. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers and coronavirus. J Hypertens. 2020;38:1190–1191. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramos S.G., Rattis B., Ottaviani G., Celes M.R.N., Dias E.P. ACE2 Down-Regulation May Act as a Transient Molecular Disease Causing RAAS Dysregulation and Tissue Damage in the Microcirculatory Environment Among COVID-19 Patients. Am J Pathol. 2021;191:1154–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sfera A., Osorio C., Jafri N., Diaz E.L., Campo Maldonado J.E. Intoxication With Endogenous Angiotensin II: a COVID-19 Hypothesis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1472. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Angeli F., Zappa M., Reboldi G., Trapasso M., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., et al. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection: one year later. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;93:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Angeli F., Verdecchia P., Balestrino A., Bruschi C., Ceriana P., Chiovato L., et al. Renin Angiotensin System Blockers and Risk of Mortality in Hypertensive Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19: an Italian Registry. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022;9 doi: 10.3390/jcdd9010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang H., Penninger J.M., Li Y., Zhong N., Slutsky A.S. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:586–590. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuba K., Imai Y., Penninger J.M. Multiple functions of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its relevance in cardiovascular diseases. Circ J. 2013;77:301–308. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vickers C., Hales P., Kaushik V., Dick L., Gavin J., Tang J., et al. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14838–14843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waumans Y., Baerts L., Kehoe K., Lambeir A.M., De Meester I. The Dipeptidyl Peptidase Family, Prolyl Oligopeptidase, and Prolyl Carboxypeptidase in the Immune System and Inflammatory Disease, Including Atherosclerosis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:387. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Serfozo P., Wysocki J., Gulua G., Schulze A., Ye M., Liu P., et al. Ang II (Angiotensin II) Conversion to Angiotensin-(1-7) in the Circulation Is POP (Prolyloligopeptidase)-Dependent and ACE2 (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2)-Independent. Hypertension. 2020;75:173–182. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Hert E., Bracke A., Lambeir A.M. Van der Veken P, De Meester I. The C-terminal cleavage of angiotensin II and III is mediated by prolyl carboxypeptidase in human umbilical vein and aortic endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;192 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu Z., Hu R., Zhang C., Ren W., Yu A., Zhou X. Elevation of plasma angiotensin II level is a potential pathogenesis for the critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020;24:290. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03015-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang C., Huang F., Wang F., Yuan J., et al. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Watanabe Y., Mendonca L., Allen E.R., Howe A., Lee M., Allen J.D., et al. Native-like SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein expressed by ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/AZD1222 vaccine. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.15.426463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deshotels M.R., Xia H., Sriramula S., Lazartigues E., Filipeanu C.M. Angiotensin II mediates angiotensin converting enzyme type 2 internalization and degradation through an angiotensin II type I receptor-dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 2014;64:1368–1375. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang S., Liu Y., Wang X., Yang L., Li H., Wang Y., et al. SARS-CoV-2 binds platelet ACE2 to enhance thrombosis in COVID-19. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:120. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00954-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Esler M., Esler D. Can angiotensin receptor-blocking drugs perhaps be harmful in the COVID-19 pandemic? J Hypertens. 2020;38:781–782. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen L., Hao G. The role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in coronaviruses/influenza viruses and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1932–1936. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duarte M., Pelorosso F., Nicolosi L.N., Salgado M.V., Vetulli H., Aquieri A., et al. Telmisartan for treatment of Covid-19 patients: an open multicenter randomized clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;37 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nunez-Gil I.J., Olier I., Feltes G., Viana-Llamas M.C., Maroun-Eid C., Romero R., et al. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors effect before and during hospitalization in COVID-19 outcomes: final analysis of the international HOPE COVID-19 (Health Outcome Predictive Evaluation for COVID-19) registry. Am Heart J. 2021;237:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cohen J.B., Hanff T.C., William P., Sweitzer N., Rosado-Santander N.R., Medina C., et al. Continuation versus discontinuation of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a prospective, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:275–284. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Puskarich M.A., Cummins N.W., Ingraham N.E., Wacker D.A., Reilkoff R.A., Driver B.E., et al. A multi-center phase II randomized clinical trial of losartan on symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;37 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Puskarich M.A., Ingraham N.E., Merck L.H., Driver B.E., Wacker D.A., Black L.P., et al. Efficacy of Losartan in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19-Induced Lung Injury: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Velez J.C., Ierardi J.L., Bland A.M., Morinelli T.A., Arthur J.M., Raymond J.R., et al. Enzymatic processing of angiotensin peptides by human glomerular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F1583–F1594. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00087.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greene L.J., Spadaro A.C., Martins A.R., Perussi De Jesus W.D., Camargo A.C. Brain endo-oligopeptidase B: a post-proline cleaving enzyme that inactivates angiotensin I and II. Hypertension. 1982;4:178–184. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Welches W.R., Brosnihan K.B., Ferrario C.M. A comparison of the properties and enzymatic activities of three angiotensin processing enzymes: angiotensin converting enzyme, prolyl endopeptidase and neutral endopeptidase 24.11. Life Sci. 1993;52:1461–1480. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90108-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Odya C.E., Marinkovic D.V., Hammon K.J., Stewart T.A., Erdos E.G. Purification and properties of prolylcarboxypeptidase (angiotensinase C) from human kidney. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:5927–5931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jeong J.K., Diano S. Prolyl carboxypeptidase mRNA expression in the mouse brain. Brain Res. 2014;1542:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tan N.D., Qiu Y., Xing X.B., Ghosh S., Chen M.H., Mao R. Associations Between Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker Use, Gastrointestinal Symptoms, and Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1170–1172. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.034. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Adams G.N., Stavrou E.X., Fang C., Merkulova A., Alaiti M.A., Nakajima K., et al. Prolylcarboxypeptidase promotes angiogenesis and vascular repair. Blood. 2013;122:1522–1531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-460360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chajkowski S.M., Mallela J., Watson D.E., Wang J., McCurdy C.R., Rimoldi J.M., et al. Highly selective hydrolysis of kinins by recombinant prolylcarboxypeptidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;405:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maier C., Schadock I., Haber P.K., Wysocki J., Ye M., Kanwar Y., et al. Prolylcarboxypeptidase deficiency is associated with increased blood pressure, glomerular lesions, and cardiac dysfunction independent of altered circulating and cardiac angiotensin II. J Mol Med (Berl) 2017;95:473–486. doi: 10.1007/s00109-017-1513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mallela J., Yang J., Shariat-Madar Z. Prolylcarboxypeptidase: a cardioprotective enzyme. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sharma J.N. Hypertension and the bradykinin system. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2009;11:178–181. doi: 10.1007/s11906-009-0032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wysocki J., Ye M., Rodriguez E., Gonzalez-Pacheco F.R., Barrios C., Evora K., et al. Targeting the degradation of angiotensin II with recombinant angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: prevention of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:90–98. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang L., Feng Y., Zhang Y., Zhou H., Jiang S., Niu T., et al. Prolylcarboxypeptidase gene, chronic hypertension, and risk of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adams G.N., LaRusch G.A., Stavrou E., Zhou Y., Nieman M.T., Jacobs G.H., et al. Murine prolylcarboxypeptidase depletion induces vascular dysfunction with hypertension and faster arterial thrombosis. Blood. 2011;117:3929–3937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-318527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jin J.M., Bai P., He W., Wu F., Liu X.F., Han D.M., et al. Gender Differences in Patients With COVID-19: focus on Severity and Mortality. Front Public Health. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kopel J., Perisetti A., Roghani A., Aziz M., Gajendran M., Goyal H. Racial and Gender-Based Differences in COVID-19. Front Public Health. 2020;8:418. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Angeli F., Marazzato J., Verdecchia P., Balestrino A., Bruschi C., Ceriana P., et al. Joint effect of heart failure and coronary artery disease on the risk of death during hospitalization for COVID-19. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;89:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gao Y.D., Ding M., Dong X., Zhang J.J., Kursat Azkur A., Azkur D., et al. Risk factors for severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients: a review. Allergy. 2021;76:428–455. doi: 10.1111/all.14657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guo L., Shi Z., Zhang Y., Wang C., Do Vale Moreira N.C., Zuo H., et al. Comorbid diabetes and the risk of disease severity or death among 8807 COVID-19 patients in China: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;166 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tabrizian T., Hataway F., Murray D., Shariat-Madar Z. Prolylcarboxypeptidase gene expression in the heart and kidney: effects of obesity and diabetes. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2015;13:113–123. doi: 10.2174/1871525713666150911112916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Agirregoitia N., Gil J., Ruiz F., Irazusta J., Casis L. Effect of aging on rat tissue peptidase activities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:B792–B797. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.9.b792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xu S., Lind L., Zhao L., Lindahl B., Venge P. Plasma prolylcarboxypeptidase (angiotensinase C) is increased in obesity and diabetes mellitus and related to cardiovascular dysfunction. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1110–1115. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.179291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kehoe K., Noels H., Theelen W., De Hert E., Xu S., Verrijken A., et al. Prolyl carboxypeptidase activity in the circulation and its correlation with body weight and adipose tissue in lean and obese subjects. PLoS ONE. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rinne P., Lyytikainen L.P., Raitoharju E., Kadiri J.J., Kholova I., Kahonen M., et al. Pro-opiomelanocortin and its Processing Enzymes Associate with Plaque Stability in Human Atherosclerosis - Tampere Vascular Study. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15078. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33523-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chrysant S.G., Chrysant G.S., Chrysant C., Shiraz M. The treatment of cardiovascular disease continuum: focus on prevention and RAS blockade. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2010;5:89–95. doi: 10.2174/157488410791110742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bracke A., De Hert E., De Bruyn M., Claesen K., Vliegen G., Vujkovic A., et al. Proline-specific peptidase activities (DPP4, PRCP, FAP and PREP) in plasma of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2022;531:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Triposkiadis F., Starling R.C., Xanthopoulos A., Butler J., Boudoulas H. The Counter Regulatory Axis of the Lung Renin-Angiotensin System in Severe COVID-19: pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Heart Lung Circ. 2021;30:786–794. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Simone A., Herald J., Chen A., Gulati N., Shen A.Y., Lewin B., et al. Acute Myocarditis Following COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination in Adults Aged 18 Years or Older. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1668–1670. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wallace M., Oliver S. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in adolescents and young adults: benefit-risk discussion. Corporate Authors(s): United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (US ACIP) COVID-19 Vaccines Work Group Conference Author(s): US ACIP Meeting, Atlanta, GA, May 12, 2021 Published June 23, 2021 https://stackscdcgov/view/cdc/108331. 2021.

- 102.Schultz N.H., Sorvoll I.H., Michelsen A.E., Munthe L.A., Lund-Johansen F., Ahlen M.T., et al. Thrombosis and Thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2124–2130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bourguignon A., Arnold D.M., Warkentin T.E., Smith J.W., Pannu T., Shrum J.M., et al. Adjunct Immune Globulin for Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:720–728. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pavord S., Scully M., Hunt B.J., Lester W., Bagot C., Craven B., et al. Clinical Features of Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1680–1689. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2021-12-16/02-COVID-See-508.pdf (Accessed on September 15, 2022).

- 106.Zappa M., Verdecchia P., Angeli F. Knowing the new Omicron BA.2.75 variant ('Centaurus'): a simulation study. Eur J Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zappa M., Verdecchia P., Spanevello A., Angeli F. Structural evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: implications for adhesivity to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors and vaccines. Eur J Intern Med. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2022.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Crowley S.D., Gurley S.B., Herrera M.J., Ruiz P., Griffiths R., Kumar A.P., et al. Angiotensin II causes hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through its receptors in the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17985–17990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605545103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Trougakos I.P., Terpos E., Alexopoulos H., Politou M., Paraskevis D., Scorilas A., et al. Adverse effects of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: the spike hypothesis. Trends Mol Med. 2022;28:542–554. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2022.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]