Abstract

Racism continues to reveal disastrous effects on the Black community. There exists no behavior-analytic literature with a specific focus on ending Black psychological suffering due to continual acts of violence perpetrated against the community. I present a behavioral model to promote Black psychological liberation, infusing preestablished frameworks of Black psychology and cultural healing practices with acceptance and commitment therapy. The model addresses behaviors observed within systemic and internalized racism.

Keywords: Black liberation, Acceptance and commitment therapy, Relational frame theory, Racial trauma, Internalized racism, Anti-Blackness

We want our bodies back. We want them returned to mothers; without blood, without brains exposed. Without humiliation, without bruises, without glass, without fire. We want our bodies back. We want our cities back. We want our culture back. We want our land back. We want our streets back. We want our freedom. We want our justice.

—Jessica Care Moore, poet

Black psychology is defined as the study of Black behavioral patterns (Smith, 1974). The study of Black behavioral patterns dates back to the work of Francis C. Sumner, also regarded as the father of Black psychology. The blueprint continued with pioneers like Inez Prosser, Herman Canady, Mamie Clark, Kenneth Clark, Martin B. Jenkins, Alberta Banner Turner, and Maxie Clarence Maultsby Jr., who were vital in promoting Black psychology and moving away from the standard Western European model of pathology and exploitation unfairly bestowed upon them by white leaders who perpetuated racism in academic and clinical spaces (APA, n.d.; Jamison, 2018). To date, Black psychologists have created theories and frameworks tailored to the Black community using relative and culturally specific teachings that improve their own lives (Baldwin, 1979; Chimezie, 1975; Clark et al., 1975; Turner & Jones, 1982).

There existed, and continues to exist, a need for the Black community to have contextually relevant frameworks and interventions directly from professionals who are similar to them (Abrams et al., 2020; Awad et al., 2020; Cabral & Smith, 2011; Chimezie, 1975; Delgado & Stefanic, 2001). In particular, Black Americans have a unique shared learning history that extends to this country’s founding. The long-running history of violence, genocide, eugenics, and other oppressive practices that the Black community endured, and in some areas continues to endure, will require an approach that seeks to remediate the damage, both tangible and psychological. Critical race theory (Delgado et al., 2012) tells us that taking a color-blind approach to human behavior reveals a failure to include an individual’s learning history and personal cultural context that may impact their worldview and actions. Although the damage from racism can never be repaired, there needs to exist a model for Black liberation that can be objectively measured and defined for the individual and the community. I aim to offer a framework and suggestions for quantifying and targeting behaviors to encourage Black psychological liberation in the service of actualizing freedom.

Defining the Problem

Although this article will outline a model of liberation, it is essential to frame the environmental contingencies that exist as a threat to the Black community to both achieving emancipation that would include freedom from incarceration; access to equitable housing, education, wealth, and health care; and engaging in discrete behaviors that would help to produce such an impact. The biggest threat to Black liberation is structural racism; in fact, it can be considered the antithesis of it. The etiology of structural racism in America begins in the 15th century and expands in the 17th century with the first documented heinous acts inflicted upon Indigenous and Black persons, which include, but are not limited to, colonization, indoctrination, rape, and murder (Solly, 2020). Structural racism refers to the norming of hegemonic whiteness and hierarchical classifications as part of a relational network that benefits those who are phenotypically white and/or white identifying. Structural racism describes the embodiment of inequitable practices within institutions or systems and includes policies that disproportionately impact individuals who fall outside of the social categorization of whiteness (Lawrence & Kelcher, 2004).

It would be non-behavior analytic to fail to note that while a system of oppression (hereafter referred to as “the system”) exists, it does not run or exist without the permission and action of living individuals. The system was created through language and defined by a verbal community that shaped and reinforced concrete discriminatory practices and behaviors. Therefore it is the verbal community that maintains systemic oppression, and it remains each individual’s responsibility to assess their own behaviors that help to keep the system working as designed.

Also necessary to frame is anti-Black racism. Anti-Black racism captures structural, systemic, and individual racism; however, it directly targets individuals who are socially categorized as Black. The impact of structural racism and anti-Blackness is well researched (Greer, 2011; Helms, 2006; Jones et al., 2013; Maxwell et al., 2014; Utsey, 1999). Examples of the impacts of racism and race-related stress include health disparities and injustices, environmental racism, higher incarceration rates, heightened homelessness, negative emotional responses, internalized racism or self-stigma, anxiety, depression, and lower life satisfaction (Graham et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2007; Utsey et al., 2008). Racism is clearly a socially significant issue for everyone, including behavior analysts.

Defining Black Liberation

The idea of freedom is inspiring. But what does it mean? If you are free in a political sense but have no food, what’s that? The freedom to starve?

—Angela Davis, activist https://www.alternativeradio.org/products/dava013

This section’s title evokes the question “Can Black liberation be defined?” The short answer is yes. Black liberation, as a defined practice, has roots in both psychology and theology. According to Black liberation theology founder James Hal Cone, Black liberation is “the affirmation of Black humanity that emancipates Black people from racism and confronts issues that are part of the reality of Black oppression" (Lincoln, 1974, as cited in Azibo, 1994, p. 336). Black liberation psychology, to Azibo (1994), proposes a new way of living free from white supremacy by honoring African and Indigenous cultural practices.

Liberation also has roots in the behavior-analytic literature and has previously been defined. Skinner (1953) discussed freedom, in relation to government, as the absence of aversive controls. He regarded the temporal nature of aversive consequences as either immediate or deferred. This means a person may experience an aversive stimulus in their current environment or may experience it in their environment at a later time. Goldiamond (1976) expanded this work, referring to freedom in the context of the availability of choice. The availability and number of genuine choices constitute the degree of freedom the individual actually holds. In his work, the greater the degree of freedom, the lower the degree of coercion or aversive consequences that are present (p. 36). Though Black people are technically free in our global society, the degree to which this is true must be considered.

For this article, I consider Black liberation as a concept, value, and outcome that can be actualized for the group and individual. The Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist organization named after Harriet Tubman’s raid that freed 750 enslaved people, imagined liberation as the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy. Baum (2017) referred to freedom as the reduction of imprisonment and enslavement. As a concept, Black liberation may initially seem abstract and nonbehavioral; however, it can be conceptualized behaviorally as both a tact and a mand. Black liberation as a concept is helpful to describe behaviors that are important to the group. For instance, tacting or defining Black liberation may be the freedom to go for a run without being murdered (and also a mand). For this to be true, others—and in this specific example, white people—must provide consequences that reinforce freedom in this context.

Black liberation as a value is similar to the concept; however, it can further verify the individual’s connection to the term. Values are defined as “rules that function as verbal motivating operations that increase or decrease the effectiveness of stimuli as reinforcers or punishers, thereby supporting overt behaviors that produce those stimuli” (Tarbox et al., 2020, p. 3). If someone has self-identified Black liberation as a value, it will likely promote behaviors in the service of freedom of oneself or the community. Behavior in the service of freedom of one’s self is regarded as self-liberation. It involves reclaiming autonomy and rejecting oppressive systems that, to some degree, have controlled their behaviors in the past. As a value, self-liberation may entail an individual intentionally setting conditions to evoke their own behavior that, as a result of rule-governed behavior and aversive contingencies, may have previously been punished (Duttry, 2014)—for example, calling out racism in real time, dressing and speaking in ways that are authentic to one’s culture, and self-advocacy, despite being met with an aversive consequence from others. Black liberation in service of the freedom of one’s community is referred to as collective liberation. Collective liberation includes efforts that positively enhance the shared experience of the group. For example, a person who values collective Black liberation may be more likely to support Black-led community organizations and voices financially or through volunteerism (Ramone, 2014).

As an outcome, Black liberation speaks to dismantling all barriers that specifically and disproportionately impact the community. Though the enslavement and forced labor of Black people technically ended in 1865, the results are still residual (DeGruy, 2005; Wilkins et al., 2012), and the tenets of racism and oppression are still present in today’s society. Michelle Alexander (2010) discussed the function of new laws and practices, such as mass incarceration, as equivalent to the function of slavery. Other residual effects include residential segregation, workforce discrimination such as steering Black people into limited-mobility career positions, and electoral oppression such as voter suppression and racial gerrymandering (Bonilla-Silva, 2013). All the aforementioned examples reinforce the maintenance of white supremacy and privilege and, in turn, further oppress Black people, similarly to chattel slavery. Some critical outcomes of Black liberation efforts include Black Americans receiving reparations, closing the wealth gap, closing the health care gap, and ending mass incarceration.

Black liberation regarded as a concept, value, and outcome is intentional in this text, and these should remain interconnected. Should Black liberation be considered a concept alone, one may fail to engage in the values-directed actions of advocating for and demanding external change in organizations at local, state, and federal levels. I argue that Black liberation is both attainable and accessible. I further contend that behavior analysts can attend to and behave in favor of Black liberation. Behavior analysts have an ethical obligation to address socially significant problems (Wolf, 1978), and therefore we have an ethical obligation to address our American legacy of 400 years of oppression.

Role of Black Behavior Analysts in Black Liberation

In 1979, Joseph Baldwin called for Black psychologists to concede their role in maintaining oppressive systems and take up their place as coconspirators for Black liberation. His essay later served as marching orders for other Black professionals to develop culturally relevant interventions for the community’s advancement. We as Black behavior analysts also have a duty to our community to ensure we are not complicit in systemic oppression. Whether we are Black academics, Black clinicians, Black researchers, or Black professors, we must ensure we are vocal and working toward a collective solution for Black freedom. The Black community’s needs cannot be better tacted by anyone else other than members of the Black community. It is a necessary burden that we remain on the front lines of defining and ensuring our emancipation. Although it is not a burden that is ours to bear alone, we must be steadfast in crafting solutions that embody the needs and the cultural contingencies unique to our people. In addition to other racial groups, we will need to engage in the work necessary to consider how we have personally been impacted by racism and how racism reveals itself in the way we work and show up in the world. We will need to address the desire to rely on white European ideals and standards to “save” our community and ourselves. We will also need to confront how we choose models for our behavior. This work will not be without its challenges, so it will be necessary to offer a personal commitment to Black liberation. While we stand firmly against racism, we must stand firmly for liberation.

Internalized Racism and Anti-Blackness

Internalized racism is defined as the resignation to “attitudes, beliefs, ideologies, and stereotypes created by the dominant white society as being true about one’s racial group” (Molina & James, 2016, p.2). Internalized racism is not separate from structural racism; it is part of it and a by-product of it. Examples of internalized racism and anti-Blackness may include, but are not limited to, beliefs that Black people are inferior to other racial groups, naturally less attractive, less intelligent, or more violent. It may also include non-Black people as inherently delicate, smart, beautiful, well spoken, positive, and upbeat. Internalized racism may even sound like an individual saying Black people should dress a certain way to be deemed respectable to other people. In this regard, it maintains that other racial group characteristics are the norm, and Blackness, and its many presentations, is not. The belief of Blackness only existing in comparison to another racial group or culture, more specifically whiteness, may also speak to the internalization of racism. This is taught through verbal behavior—that the individual is not free to define themselves on their own and must rate and organize their behavior to emulate that of others. Existing as a comparative marker to other groups denies the uniqueness and autonomy of the Black community.

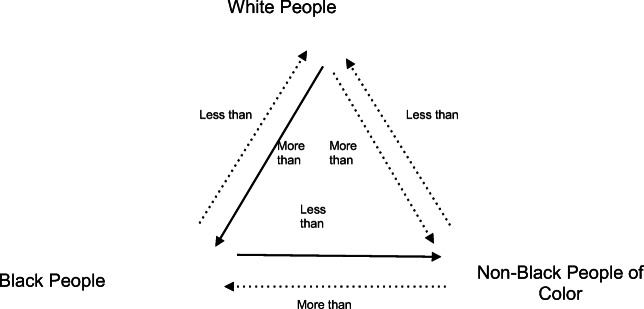

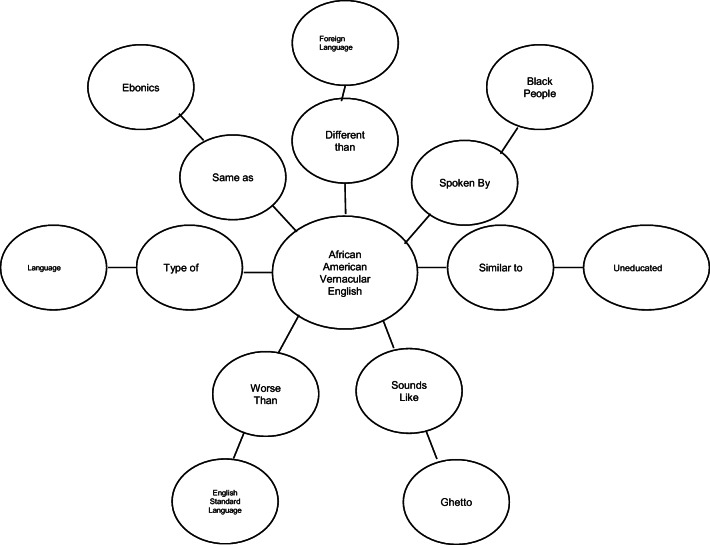

Internalized racism can be conceptualized using multiple behavior-analytic processes. For example, rule-governed behavior applies to this concept, even when the rules related to whiteness as normative are arbitrary and false (e.g., “If a person is light skinned, they are good looking”). It also can be understood using relational frame theory (Fig. 1; Dixon et al., 2003). Racism is equivalent to a social caste system, which is embedded in hierarchical framing. Internalized oppression then speaks to learning comparative frames regarding others and oneself (e.g., “White people are better looking than Black people”). Given the behavioral literature on derived relational networks, Black people will not merely “unlearn” what we were taught about ourselves, one another, and our cultural behaviors in relation to other races. Figure 2 depicts a relational network including African American Vernacular English (AAVE) that is likely common among Black Americans. Relational networks, however, can be expanded, which may evoke variability in responding, but previous learning will not be erased. Therefore, Black liberation is not about getting rid of relational frames but more about changing our relationship to the content by adding to our networks and shifting behavioral patterns as a result.

Fig. 1.

Behavioral sample of internalized racism using comparative relational framing. Note. An individual may have been taught white people are more (any adjective can be filled in) than Black and other people of color. Also, non-Black people are more (adjective) than Black people. With this teaching, one derives that Black people are less (adjective) than both non-Black people of color and white people. The solid lines in this figure represent relations that have been directly trained, whereas the dotted lines represent derived relations (not directly trained)

Fig. 2.

Example of a network of relational framing behavior surrounding African American Vernacular English

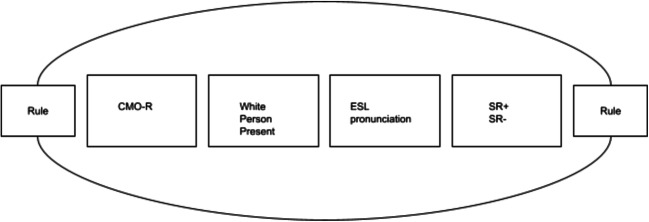

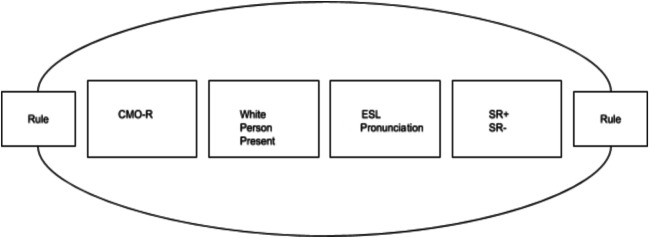

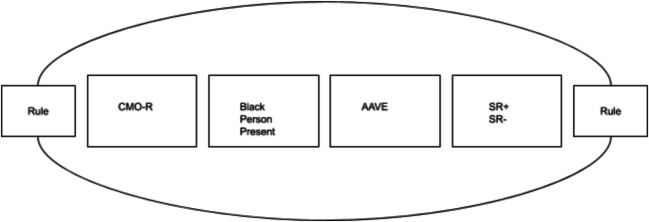

Additionally, a four-term contingency model can be useful for behaviorally analyzing internalized racism and anti-Black behaviors. Figures 3, 4 and 5 depict four-term contingencies, including conditional discriminations, which bring specific contingencies under contextual control (Cooper et al., 2019). In each, one may view a conditional sample as skin color (i.e., being in the presence of a white or Black person). In Fig. 3, in the presence of a white person, the Black speaker selects an "incorrect" response (i.e., speaks in AAVE), resulting in punishment or error correction. In Fig. 4, in the presence of a white person, the Black speaker selects the “correct response” (i.e., speaks in English Standard Language) and receives reinforcement. In Fig. 5, in the presence of a Black person, the Black speaker speaks in AAVE and contacts reinforcement. In each of these examples, the conditional sample (i.e., the skin color of the person present) then serves as a reflexive conditioned motivating operation for the Black speaker in the future. In addition, each of these examples serves as a context for the Black speaker to derive a rule about how they “should” or “shouldn’t” talk, based on who is present.

Fig. 3.

Direct and Indirect Teaching of Culturally Acceptable Behaviors Example of a potential four-term contingency wherein the individual experiences direct aversive consequences for speaking in African American Vernacular English (AAVE). VB is an acronym for verbal behavior. Verbal behavior is defined as behavior strengthened or weakened through consequences provided by other persons (Skinner, 1957). SP+ is an acronym for positive punishment. SP+ is a stimulus added to the environment that decreases the likelihood of behavior occurring in the future. SP- is an acronym for negative punishment. SP- is a stimulus removed from the environment that decreases the likelihood of behavior occuring in the future.Note. The likelihood of using this modality of speaking in the future decreases, and the individual may derive a new rule

Fig. 4.

Rule derivation that may be assessed as part of the standard contingency model. CMO-R, which stands for reflexive conditioned motivation operation, "alters the value of its own removal (or continued presence) as a type of reinforcement (or punishment) and alters the probability of behaviors occurring that have previously been associated with these consequences." (Langthorne and McGill, 2009, pg. 26). ESL is an acronym for English Standard Language. Sr+ is an acronym for positive reinforcement. Sr+ is a stimulus added to the environment that increases the likelihood of behavior occurring in the future. Sr- is an acronym for negative reinforcement. Sr- is a stimulus removed from the environment that increases the likelihood of behavior occuring in the future.Note. Rule governance involves verbal antecedents and behavior that is not directly trained. Additionally, rule governance can be strengthened following the consequences of certain behaviors. In this case, the rule that one must speak in English Standard Language when white people are present, followed by positive or negative reinforcement, an individual may emit confirmatory verbal behavior of the rule in the future, as well as deriving additional new race-related rules

Fig. 5.

Example of a four-term contingency surrounding the behavior of speaking in African American Vernacular English (AAVE) around black individuals. CMO-R, which stands for reflexive conditioned motivation operation, "alters the value of its own removal (or continued presence) as a type of reinforcement (or punishment) and alters the probability of behaviors occurring that have previously been associated with these consequences." (Langthorne and McGill, 2009, pg. 26).ESL is an acronym for English Standard Language.Sr+ is an acronym for positive reinforcement. Sr+ is a stimulus added to the environment that increases the likelihood of behavior occurring in the future.Sr- is an acronym for negative reinforcement. Sr- is a stimulus removed from the environment that increases the likelihood of behavior occuring in the future.Note. Similar to the functional relations depicted in Fig. 4, this four-term contingency both establishes race-related behavior and serves as a context to derive rules surrounding such behavior

It is important to note that these behaviors can be evoked without direct training. Through verbal behavior processes of arbitrarily applicable derived relational responding (e.g., being told about the contingencies outlined in the previous example), an individual’s behavior may fall under the same control. Should an individual experience this contingency directly, it will likely strengthen (or create) the rule of shifting linguistic behavioral patterns in the presence of certain stimuli. Therefore, understanding rule generation and other complex verbal processes can be helpful in understanding overt behaviors as an outcome of internalized racism.

Once an individual has acquired relational networks that include frames of reference to their own identity, they may, in turn, enact behaviors that are the same as or similar to those of the dominant group against others in their own racial group as a response to an established “rule.” This may lead to delivering consequences or enacting behaviors that may be aversive to their own group and simultaneously reinforce structural and systemic racism. Black people who are victims of racism can also become perpetrators of it through this process. To much dismay, a person who exhibits behaviors representative of those who fall outside of their racial category may experience a more positive sense of self, as engaging in these behaviors creates a context for the individual to relate themselves as “different from” (i.e., relational framing in terms of distinction) other members in their racial classification. Members of the group who display behaviors in alignment with their own oppression may also receive positive reinforcement from those of dominant identity groups (or other racial minority groups) in the form of social praise or other conditioned reinforcers. For example, a Black person who verbally chastises other Black people in a public, predominately white forum may be praised as being “one of the good ones.” With the signaling of reinforcement for Black individuals who perpetuate anti-Blackness, this may be a strong competing reinforcer for Black liberation. Although it may serve as immediate reinforcement, and to the individual could potentially be tacted as self-liberation, it hinders progress on behalf of the collective and impacts the individual’s psychological liberation.

Last, as a necessary reminder, achieving freedom does not solely rest on the oppressed. Although this model includes a collaborative effort for Black people to advance collective and individual freedom, the responsibility of ensuring freedom still rests on a collective of white individuals with social and political power, who created the system as a means for advantage and cultural preservation. Even if found to be of utility to the Black community, a psychological model could never replace the necessity to dismantle structural racism and white supremacy to produce the outcomes of Black liberation. Non-Black people of color also have a responsibility to dismantle anti-Black oppression (Li, 2020). Though this topic is beyond this article’s scope, behavior analysts may pull from previous behavior-analytic literature for a model of recognizing power dynamics (Mattaini, 2017).

Behavior-Analytic Considerations for Internalized Racism and Anti-Black Behaviors

As with working with any individual, behaviors to consider would be based on and chosen by that person. Self-selection of behaviors and autonomy are vital components to consider when addressing individuals with a history of aversive socially mediated consequences. Self-selection refers to the presence of motivating operations that produce an evocative effect for the selection of certain behavior. Behavior analysts may also pull from the literature on self-management to assist individuals who have self-selected behaviors for change (Cooper et al., 2019, p. 683). Self-management is “the personal application of behavior change tactics that produce a desired improvement in behavior” (Cooper et al., 2019). Black individuals may monitor their own behavior in relation to internalized racism, both public and private, and take action to change the manipulable stimuli in their environment so their behavior changes in values-consistent ways. An example may be an individual who self-monitors a shift of linguistic behaviors in the presence of non-Black individuals, who then may provide a prompt and reshift back to their natural tongue.

An individual who has internalized racism or displays anti-Black behaviors (which is likely every person who has been part of a racist environment at some point in their learning history) may first need to label rules or objectively define behaviors they engage in that have been taught and reinforced by non-Black people (and potentially other Black people). This will require flexibility and honesty. Approaching internalized racism is likely to prove challenging, as a person may display what psychologists call cognitive dissonance, which refers to changing an evaluation in a direction congruent with a preexisting frame of reference (Festinger, 1957; Osgood & Tannenbaum, 1955). Therefore, internalized racism or anti-Black behaviors may not be easily tacted, or they may be denied even when new evidence is presented. Behavior analysts may assist by working to define examples of internalized racism and anti-Black actions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Internalized racism and rule-governed behavior scale

| Statement | Example | Scoring criteria | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| I believe some stereotypes about Black people are true. | Black people are loud. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| If Black people are well dressed and groomed, they have a better chance to gain the respect of other races. | Black people should pull up their pants and not expose their private parts. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| I am suspicious of a large group of Black people in certain areas. | If I see a large group of Black people while in an inner city, I move away. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| I emit protective behaviors when I see a group of Black people approaching, depending on where I am. | I start walking slower or faster to my car/destination. |

0: I do not do this. 1: Sometimes I do this. 2: Generally I do this. |

|

| I generally ascribe attractiveness to light-skinned Black people. | If I see a group of multitoned Black women, I visually attend to the lighter skinned woman. |

0: I do not do this. 1: Sometimes I do this. 2: Generally I do this. |

|

| At work, the approval of my work from white colleagues and supervisors is important. | I look for feedback from white peers/colleagues to indicate that I am doing a good job. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| I struggle to trust Black people in leadership positions. | I think Black people in leadership positions have a hidden agenda. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| In public, I feel ashamed when Black people talk loud or yell. | I look at other non-Black people to observe their reactions and shake my head to show disagreement with the actions of the loud Black people. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| When choosing a professional service provider, I am more likely to select someone who is non-Black. | I will hire a non-Black accountant even when I have found a Black accountant with equal skills and abilities. |

0: I do not do this. 1: Sometimes I do this. 2: Generally I do this. |

|

| I prefer to live in a mixed neighborhood or non-Black neighborhood. | When looking for a new home, I will choose a mixed or non-Black neighborhood instead of one that is predominantly Black. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Natural hair is not professional or upscale. | Black people should wear their hair straight. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people must code-switch to get ahead in life. | Black people must use English Standard Language to succeed. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people need to fix their own issues before demanding it of other races. | Black people need to regulate gun violence before demanding the end of police violence. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people are their own worst enemy. | Black people are the reason for their own demise. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people are less professional than other races. | Black people are late and rude and do not render adequate services. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people are like crabs in a barrel. | Black people do not want to see one another succeed and will sabotage someone who is excelling. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people who cannot/do not code-switch are ghetto or uneducated. | When Black people speak with incorrect English Standard Language, I judge their intelligence or correct them. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| If a group of Black men pass me on the street, I feel nervous. | My heart rate increases when a group of Black men are walking past me. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black women have attitude problems. | Black women complain for no reason. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people are not safe when they leave the house. | Black people risk being assaulted, jailed, or murdered when they leave their homes. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people should avoid speaking about topics and using colloquialism that reinforces Black stereotypes. | Black people should not speak about topics that reinforce Black stereotypes. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

|

| Black people will never receive liberation. | Black people will always suffer from racism. |

0: I do not believe this. 1: Sometimes I believe this. 2: Generally I believe this. |

Note. This is an example of using outlining behaviors that may reflect internalized racism and anti-Blackness. Behavior analysts may develop behavioral scales that can help an individual determine which anti-Black behaviors to change

Collective and Racial Trauma

Racism has been found to cause psychological stress and trauma for Black Americans (Pieterse et al., 2012). Trauma, as it relates to racial tension, is referred to in the literature as racial trauma. Racial trauma is defined as reactions to dangerous events related to real or perceived experiences of racial discrimination (Comas-Díaz et al., 2019). Comas-Díaz and Neville further outlined events such as threats of harm or injury, slavery, humiliation and shaming, witnessing or hearing about events, systemic oppression, community and police violence. The impact of racial trauma may be observed as anger, headaches, depression, chest pains, back pains, hypervigilance/arousal, sleep disturbance, and ulcers (Truong & Museus, 2012).

Collective trauma is defined as a shared learning history of, or psychological reaction to, a traumatic event that affects an entire society (Hirschberger, 2018). Events included in collective trauma are genocide, mass shootings, wars, terrorism, forced migration, natural disasters, and slavery. The impact of collective trauma for individuals may include sleep disturbance, hypervigilance, isolation/withdrawal, irritability, anger, guilt, self-doubt, avoidance, negative emotions and mood, flashbacks, and excessive activity levels (APA, 2013b). The impact of collective trauma also may include passing down culturally derived teachings and traditions about threats that promote group preservation, amplifying existential concerns, and increasing motivation to remember the trauma as a symbolic system of meaning (Comas-Díaz et al., 2019). During periods of collective trauma, community members may feel a more profound sense of connection to other community members.

For Black people, understanding the impacts of both racial and collective trauma may serve as a useful tool to identify when responding to environmental stimuli that may be acting as race-related stressors. Racial trauma may be present even when we may not be aware of it. Often, we do not realize daily stressors that may affect our psychological or physiological health (APA, 2013a). Collective trauma may reveal itself when stories or videos emerge of state-sanctioned violence initiated by police officers. Research confirms that there is a prolonged mental impact after viewing police killings of unarmed Black men, even 1 or 2 months after the initial exposure. This is not the case for white respondents (Bor et al., 2018).

An Integrative Behavioral Model for Black Psychological Liberation

Utilizing existing models of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), storytelling, and a functionally appropriate trauma-focused lens allows clinicians to use tools readily at our disposal that honor the ancestral spirit of the Black community which can potentially promote Black liberatory behaviors. Although a term such as “ancestral spirit” may sound unconventional to behavior analysts, it should be noted that it may hold significance for the target population (A. Clark, 2013). To translate, the ancestral spirit speaks to social and cultural validity (Solano-Flores & Nelson-Barber, 2001). The following sections of this article will provide an overview of modalities that may be combined to actualize Black liberation.

ACT

ACT is a functional-contextual framework that bolsters values-driven action and fosters psychological flexibility through six core processes: acceptance, cognitive defusion, flexible attention to the present, self-transcendence, values, and committed action (French et al., 2017; Hayes, 2019). The contextualist framework promotes explicit naming of our values and the goals necessary to work toward those values—in this case, Black liberation (Biglan & Embry, 2013). Functional contextualism, both radical and conceptually systematic, claims that measuring outcomes that improve all people’s well-being, including being free from disease, attack from others, and lack of food and shelter, is possible. This stance provides the foundation for using ACT and functional contextualism to promote Black liberation.

ACT, although popularized in modern mainstream psychology, reveals components native to Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latinx communities prior to its founding that are often left out of contemporary discourse. The purpose of presenting this model is not to deny the long-standing solutions developed by the Black community prior to ACT’s founding, but to bring attention to the parallels that may be further explored in the behavior-analytic sphere. The methodology uses ancient Eastern practices, as it embeds flexible attention to the present moment, defusion, and acceptance practices, which are traditionally referred to as mindfulness, into the model. It would be disingenuous not to mention that although ACT shows promise, there is no specific evidence base that uses ACT to address internalized racism. Although ACT has not been proven to be effective yet with the Black community in this specific context, the incorporation of mindfulness speaks to its potential as mindfulness-based practices have been shown efficacious (Spears et al., 2017; Woods-Giscombé & Gaylord, 2014). The model’s focus on self-as-context may make room for a compassionate and strengths-based approach, instead of relying on deficits of the individual, which is reminiscent of preexisting racist ideas and rules. A strengths-based approach may also allow for a release of guilt or shame that may be present when an individual internalizes racist conditioning. In addition to mindfulness, the model’s heavy use of metaphors may be culturally relevant, given their presence in Black linguistic and cultural expressions (Woodson, 2017). I do not contend that ACT, as it is already formed, will be enough to shape Black liberation, but rather that its basic tenets with a culturally adapted lens may show utility.

The following provides an example of methods to use ACT in the service of Black liberation.

Values

- As a reminder, values are defined as “rules that function as verbal motivating operations that increase or decrease the effectiveness of stimuli as reinforcers or punishers, thereby supporting overt behaviors that produce those stimuli (Tarbox et al., 2020, p.3). This is a crucial component of ACT. Values that are self-constructed can be used for Black liberation in a variety of ways. It may serve to ground the individual and center how they interact with themselves and others.

- Examples of Black liberatory values-guiding questions include the following: Consider what about your Blackness is essential. How do you want to show up for your community? How would you live if there were no conditions placed on you related to your Blackness?

- “Blackness in Future” is an example values activity:

- Imagine it is the year 5060. A group of Black youths have just found a time capsule. Inside it is information about you and the life you lived to help your community. What is inside this box? What story does it tell? What did you give to sow into the lives of these young people

Acceptance

- Acceptance is active, not passive; it does not mean you need to resign, but rather engage. It refers to a willingness to accept an immediate experience and the emotional reactions that accompany it, and allows for an individual to be present with stimuli without attempting to shift psychological or private events. An example may be someone trying to change feelings of sadness when a racist event occurs by engaging in behaviors such as the active denial of racism. This process of active denial speaks to the process of experiential avoidance and negative reinforcement. Acceptance as a comparison would mean sitting with the emotions, and the private verbal behavior that arises, as opposed to denying the activating event. It is with acceptance that one may empower themselves to evoke behaviors as a means to shift aversive oppressive contingencies.

- Examples of acceptance-guiding tenets include the following: Accept racism exists as opposed to experientially avoiding the emotional reactions that accompany its tangible impacts. Accept learned anti-Black rules and behaviors instead of denying susceptibility to them. Accept resistance to habituating to a racist environment. Accept Black joy as noncontingent reinforcement. Accept Black diversity of thought and patterns of behavior.

- “Black Suffering Inventory” is an example of an acceptance exercise adapted from “Your Suffering Inventory” (Hayes and Smith, 2005):

- Take a sheet of paper and draw a vertical line down the middle. On the left side of the line, write down a list of all the psychologically difficult issues for you as a result of or in connection to racism. These items include both external/situational events and your reactions to them. Some may be specific situations you have experienced, and others may not be. An example of a problematic issue that also reflects your response may be “feeling unsafe when I entered an all-white neighborhood.” A nonexample may be “white neighborhoods.” You may include thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, habits, or urges that distress you. There is no right or wrong answer; just write what you react to. You can include the things that you believe bring you pain.

- Once complete, on the right side column, write how long each item has been a problem or thought for you.

- Once this is complete, rank the items based on the impact they have on your life (from most impactful to least impactful).

- Last, draw arrows between the items on the list that are connected. For example, suppose that one of your items is being told that there is no place for your culture in a specific industry, and another is being tokenized. If you feel the two are related (i.e., because there is no place for your culture, you can only be a token at work), draw an arrow between them. You may find many connections in your list (or not). There is no set amount of links you must draw. It is useful information for yourself, no matter the number of relations formed. If you find items highly ranked on your list and connected to many other things, it may show their importance.

- When you are finished, review your list. This is your racism-suffering inventory. It may change over time, but for now, it shocws you how you feel racism has impacted and is impacting you.

Present Moment Awarenes

- This process is otherwise known as “mindfulness.” It means to maintain attention toward stimuli currently present in the environment. It also means noticing one’s own attending behavior (Tarbox et al., 2020).

- Examples of present-moment awareness tenets for Black liberation include the following: Notice and get curious about how racism impacts your life, on both the smaller and larger scale. Notice bodily sensations when microaggressions are enacted against you. Note when you code-switch. Notice the desire to shift your wardrobe depending on whether non-Black people will be present. Notice when you expect other Black people to conform to the rules regulated by whiteness.

- “Noticing Anti-Blackness” is an example of a present-moment awareness exercise:

-

Read the following paragraph. Actively attempt to place yourself in this scenario. As you are reading, notice your gut reactions. Notice your bodily sensations. Notice your thoughts. Anytime you find yourself attempting to shift or shut down your thoughts, instead of arguing with it, just notice it:“Imagine you are getting ready for a job interview. You work at a Fortune 500 company in a managerial position. You worked hard to get where you are, and being one of two Black people in your office is a tough role. Into your office walks a young Black woman who is applying for your open corporate, client-interfacing position. You orient initially to her face and then notice her hair. It is braided, multicolored with a handful of blue and purple streaks. You glance at her wardrobe. She is dressed in business-appropriate clothing, slacks, a button-up top, and hoop earrings. She takes her seat, and you begin asking her standard interview questions. You segue to a question about efficiency and completing projects in a timely manner: ‘In this position, you may be given many tasks at one time. How do you best manage your time to meet all of your deadlines?’ She responds, ‘Nobody got time to waste, so I make a to-do list immediately, ya know? And once I got everything organized, I check everything off as I go along. I didn’t always do that, but I quickly learned, ya know?’ She proceeds to continue her outline of rendering the most efficient outcomes in her work. It is time to decide if this candidate will make it to the next part of the interview. The answer can only be yes or no. You decide ______.”

- Take a moment to sit with this scenario. What came up for you? How did this scenario end? It is important to note that this exercise is not designed to help you change your thoughts or feelings surrounding internalized racism, but rather to notice them and notice your own likely overt behaviors. This kind of flexible, self-directed attention can then create a context to choose specific overt behaviors that you feel move you toward what you value: perhaps in this case, supporting Black liberation—perhaps, accepting her responses as sufficient and moving toward hiring her

-

Defusion

- Defusion means observing private behavior, such as thinking, without being governed by it (Moran & Ming, 2020). In other words, defusion de-literalizes or weakens the functional dominance of certain thoughts as discriminative stimuli or rules. This can involve addressing rigid rule following and resignation to previous stories that an individual has been taught. With defusion, one may be able to dispel self-blame and create distance between the rules and one’s own behaviors.

- Examples of defusion tenets for Black liberation include the following: Consider a rule you have been taught. For example, “Black people cannot jog in their own neighborhoods.” Perhaps “Black people must present themselves respectably to the world to gain respect from others.” Or “Avoid Black women; they have attitudes or are angry.” “All Black people do is complain.” “Black people can’t have justice until they fix their own issues.” “Black people are like crabs in a barrel, pulling each other down as a means to block their success.” “Black people who speak with AAVE are ghetto and unintelligent.” Look at the rule—observe it. Now that the rule is in front of you, how may you respond?

- “The Freedom Train” is an example of a defusion exercise (adapted from Stoddard & Afari, 2014):

- Imagine you are standing in a field of tall grass. Right in front of you is a fence. Beyond the metal barrier, you see train tracks. In the near distance, a train is approaching. This train is a symbolic representation of your mind. As the train starts to pass, you notice writing on the first train car. Each car is a stereotype or rule created about Black people. Imagine what this stereotype/rule is. It could say something like “Being Black is exhausting,” “Black people are uneducated,” “Black people have to work twice as hard,” or “Black people are like second-class citizens.” Maybe what is written on the cars are stereotypes/rules that evoke emotions from you. Perhaps they are ones that you work tirelessly to prove false to others. Continue looking at the train. If you begin pulling your attention away from the car, attempting to focus somewhere else, or arguing with the content, stay there for a moment. Notice what thought hooked you. Notice the speed of the train car. It has slowed down. And then, when you are ready, allow the train car to keep moving, picking up speed, and take notice of the next car. What does this stereotype say? Notice your response to it. Notice your desire to act or argue or become hooked. Notice as it too drives past you and disappears into the distance.

Self-as-Context

- Self-as-context refers to flexible self-perspective taking. It allows the individual to analyze their behavior in relation to current environmental stimuli instead of rigidly resorting to previously encountered stimuli or thoughts. For example, someone may say, “I am Black; therefore, I must work twice as hard and forgo rest and wellness care.” This would reflect being fused to rules. An individual may consider times in which they “deserved” to rest and consider questions like “Is it possible for me to be a powerful advocate for my community and also be a person who takes care of themselves? What might that look like?”

- Examples of self-as-context guiding tenets include the following: Whom were you told that you are? Were you taught this through the media? Consider the stereotypes to which you have held firm. Consider the ones you have worked hard to dispel.

- “A Heavy Load” is an example of a self-as-context exercise:

- Take a moment to think back to some of the negative messaging you learned about yourself and Black people. If it is helpful, maybe you can write them down. Think of as many as you can. As you think of one/read one message, pretend the message is a long-sleeved shirt. Put it on. Now think of the next and put it on, on top of the last layer. As you are putting on the layers, notice what happens to the shirts. Does it become harder to wear them over time? Does it feel heavy? Imagine how it may be to wear these shirts around every day. What might wearing this number of shirts around help you accomplish? What might wearing the shirts prevent you from doing? Now, think about taking off each shirt. Think about how it feels to get rid of each one until you reach your bare skin. A person’s self-directed verbal behaviors (i.e., thoughts about self) are a result of our conditioning, and they cannot be eliminated, made “correct,” controlled, or “taken off,” but what we can do is develop flexible and values-directed ways to respond to the many thoughts we have about ourselves, particularly those of internalized racism.

Committed Action

- This is another essential tenet of ACT and speaks to tangible outcomes to be observed as a result of the model. To engage in committed action describes discrete behaviors enacted in connection to one’s values. For example, someone who may tact Black liberation as a value may enact behaviors such as voting for or advocating for a bill that would grant economic reparations to the Black community.

- Examples of tenets that guide committed action include the following: Think back to your value of Black liberation. How can you move toward it—today?

- “The Committed Action Liberation Plan” is an example of a committed action exercise:

- If Black liberation is my value, my goal is ______.

- The actions I will take to achieve my goal are ______.

- The discomfort (thoughts, emotions, and negative consequences) I am willing to experience to achieve this goal is ______.

Storytelling/Self-Narration

Language as culture is the collective memory bank of a people’s experience in history. - Ngugi Wa Thiong'o

Storytelling is an African tradition that extends back further than the time when Black ancestors were being sold and stolen from their lands. African people are rooted in oral tradition and folklore. There is kinship and familiarity in the way Black people communicate with one another. Typically, in Africa, storytelling took place in the evening after returning from work (Tuwe, 2016). During that time, children and elders sat around and told their own stories. Children were also asked to retell the elders’ accounts as if it were a test to ensure the story was appropriately recalled (Gikandi, 2009).

It is vital to frame the storytelling of African American ancestors because of the core role it played in our oppression and the potential it has to contribute to Black liberation. During slavery, it was illegal to read and write. Verbal behavior—in this case, storytelling—functioned as a way to preserve the experiences of enslaved people in some fashion (Tuwe, 2016). This behavior’s function was to transmit information beyond the immediate environment and relay knowledge to forthcoming generations. According to Ngugi wa Thiong’o (1986), language brings about culture. And culture brings, with verbal behavior and written works, values of how we perceive ourselves and our place in the larger world.

Narrative therapy, sometimes called race narrative therapy (Mbilishaka, 2018), is a treatment modality that addresses private events and verbal behavior emitted in the context of social oppression. The central premise rests on the notion that an individual is the expert on their own life. A narrative can be a useful tool to promote psychological healing, as it places the ownership of stories back into the hands of the oppressed. Narrative, or ownership of narrative, allows for the replacement of previous anti-Black verbal behavior with new verbal behavior dictated by the individual, thus establishing new relations (Taliaferro et al., 2013). Given the long-standing history of racism, there have been fictitious and harmful stories told about Black people for centuries. Nobles (2013) underscored the importance of remembering the fractured identities of African people as a result of the Maafa (great disaster of enslavement/oppression) and colonization.

Using narratives and storytelling is a method for Black people to reclaim agency and tell our own stories that may be new or in alignment with elders’ stories before colonization. It also allows a space to process the narratives told by others that are fallacies and encourages the externalization of the narrative so that the person can dispel the notion that the stories related to racism are their own (Mbilishaka, 2018). Additionally, it may include the use of archiving their own stories. For Black Americans who have had their history erased, there is power in the real-time documentation of events. This also allows space for the individual to narrate their own happiness and joy. The benefits of narrative therapy may include increased self-compassion and reduced guilt and shame (Mbilishaka, 2018).

Behavior analysts may incorporate narrative into the ACT modality when considering self-as-context and defusion processes. The individual may consider the rules they have been taught about themselves and their community. Using defusion may promote Black liberation by getting individuals untangled from the narrative established by white individuals in history. An example includes the narrative that Black people are prone to committing crimes (Griffith, 1915). A Black person who is entangled with the rule that Black people commit crimes, otherwise stated, has internalized anti-Blackness, may also be likely to question their safety in a Black neighborhood, may consider waiting before leaving their vehicle so that a group passes, or has other private events related to the motivation of a group of Black people congregating on a city street. Using narratives not only may create distance from these thoughts but also will enable the individual to reconstruct stereotypes in addition to creating a context in which to choose different overt behaviors that may help them be more actively supportive of Black liberation.

Trauma-Informed Intervention

The role of trauma in the Black community is too prominent not to include in this effort. There can be no Black liberation without considering racial trauma. Considering racial trauma should not be an afterthought but a setting event acknowledged in every context. Racial trauma for Black people is conceptualized and approached by community groups and psychologists (Anderson & Stevenson, 2019; Grills et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2018). Behavior analysts can approach Black liberation and relevant interventions with a trauma-sensitive and functional-analytic lens (Kolu, 2020; Lincoln et al., 2017). This requires the behavior analyst to consider the history of racial events in context with the behavior of the individual. As previously outlined in this article, an individual is not required to experience direct contingencies in order to shape their behaviors. Through verbal behavior, an individual may still experience trauma and therefore evoke behaviors within this context. The assessment or consideration of past trauma, extending 400 years, will allow a behavior analyst to initially withhold contraindicated behavioral procedures (Kolu, 2020) that may harm the individual. A contraindicated procedure for a group of individuals who have undergone physical and emotional abuse would be using error-correction procedures that may be considered aversive to the individual. From behavior-analytic literature, individuals who are placed in aversive conditions, such as the presentation of shaming, may select countercontrol behaviors (Skinner, 1953). Shame and the evocation of countercontrol behaviors are not the aims of the model, but rather self-selection of personal values and associated behaviors. This means we cannot shame Black people into liberating themselves from anti-Black racism; however, we can make use of culturally appropriate behavioral processes to aid this outcome.

When preparing intervention, behavior analysts who recognize racial trauma may focus on a transparent consent process, provide clear instructions, and create a safe environment that does not perpetuate past racial abuses. Following an assessment incorporating shared and individual learning history, the behavior analyst can consider targets for programming (i.e., decreasing behaviors that impact the individual’s own racial liberation) and the methods for behavior change. The behavior analyst can then take data and teach the individual how to take their own data. Last, a behavior analyst can program antecedent strategies that would assist the individual in emitting behaviors further in alignment with Black liberation. With the intervention, the behavior analyst should assess current aversive race-based contingencies that may further harm the individual. For example, an individual may determine that speaking up against workplace racism (when being terminated is a potential consequence) may not be the best behavior to target if the person is also undergoing food or housing insecurity. Recognizing and discriminating competing contingencies that impede an individual from evoking behavior in certain environments is necessary to shield the individual from experiencing further harm. A behavior analyst may then work with the individual to create an intervention that is both in alignment with their values and less self-injurious.

Conclusion

This article aims to serve as a starting point for Black behavior analysts and non-Black and culturally attuned behavior analysts to conceptualize Black liberation and consider its place in the literature. Black psychological liberation is a socially valid topic; therefore, considering a framework such as this one may help the larger world. This framework may also be useful when working with clients who struggle to accept their physical features (skin color, hair, etc.) or generally display rule-governed behavior related to their racial categorization. The use of preestablished frameworks may allow behavior analysts to use existing training to tailor individual interventions. Black liberation will not be actualized through an “unlearning process” but will require specific targeted actions toward that value.

It should also be noted that although this model discusses Blackness in the context of social oppression, Blackness is not restricted to this experience. Blackness can exist without and outside of the context of hegemonic whiteness. However, it would be disingenuous not to address a component that has revealed harmful effects on the community: internalized racism and anti-Blackness. Just as Azibo’s (2015) nosology outlines the social and political implications of psychological distress, the impacts of private events that have been weaponized by white supremacy should be addressed as well. It is past due for the field of behavior analysis to produce models intentionally designed to center the liberation of historically marginalized groups. I believe Black behavior analysts and non-Black colleagues can use the tools described in this article—Black psychology, trauma-informed care, ACT, and narrative therapy—to ignite the next phase of evolution in the culture of applied behavior analysis and beyond that leads to positive, measurable outcomes for the Black community.

Author Note

Denisha Gingles https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5595-0562 I (she/her) am a Black American/descendant of enslaved ancestors and a cisgender woman. It is through the lens of collective and cultural healing that this article was prepared. This article uplifts Black researchers who have paved the way for this discourse and encourages room for expansion beyond colonialism and anti-Black racism. I would like to thank my ancestors and community of fierce social justice organizers who have encouraged this article. Thank you for your invaluable contribution to building a better world and liberated community. Additionally, I would like to thank Jovonnie L. Esquierdo-Leal and each reviewer for their time reading and preparing the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not applicable, as there were no human subjects.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abrams JA, Belgrave FZ, Williams CD, Maxwell ML. African American adolescent girls’ beliefs about skin tone and colorism. Journal of Black Psychology. 2020;46(2–3):169–194. doi: 10.1177/0095798420928194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New Press.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Francis Sumner, PhD, and Inez Beverly Prosser, PhD: Featured psychologists . https://www.apa.org/pi/oema/resources/ethnicity-health/psychologists/sumner-prosser

- American Psychological Association. (2013a). Physiological and psychological impact of racism and discrimination for African-Americans. https://www.apa.org/pi/oema/resources/ethnicity-health/racism-stress

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013b). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053

- Anderson RE, Stevenson HC. RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. American Psychologist. 2019;74(1):63–75. doi: 10.1037/amp0000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad GH, Kashubeck-West S, Bledman RA, Coker AD, Stinson RD, Mintz LB. The role of enculturation, racial identity, and body mass index in the prediction of body dissatisfaction in African American women. Journal of Black Psychology. 2020;46(1):3–28. doi: 10.1177/0095798420904273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azibo DA. The kindred fields of Black liberation theology and liberation psychology: A critical essay on their conceptual base and destiny. Journal of Black Psychology. 1994;20(3):334–356. doi: 10.1177/00957984940203007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azibo, D. A. (2015). Moving forward with the legitimation of the Azibo nosology II. Journal of African American Studies, 19(3), 298–318. 10.1007/s12111-015-9307-z.

- Baldwin JA. Theory and research concerning the notion of Black self-hatred: A review and reinterpretation. Journal of Black Psychology. 1979;5(2):51–77. doi: 10.1177/009579847900500201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, W. M. (2017). Understanding behaviorism. John Wiley & Sons.

- Biglan A, Embry DD. A framework for intentional cultural change. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2013;2(3–4):95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva, E. (2013). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (4th ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of Black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet. 2018;392(10144):302–310. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31130-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral RR, Smith TB. Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(4):537–554. doi: 10.1037/a0025266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimezie A. Colonized mentality and Afro-centric peoples. Journal of Black Psychology. 1975;2(1):61–70. doi: 10.1177/009579847500200108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. Honoring the ancestors. Journal of Black Studies. 2013;44(4):376–394. doi: 10.1177/0021934713487925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CX, Mcgee DP, Nobles W, Weems LX. Voodoo or IQ: An introduction to African psychology. Journal of Black Psychology. 1975;1(2):9–29. doi: 10.1177/009579847500100202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L, Hall GN, Neville HA. Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist. 2019;74(1):1–5. doi: 10.1037/amp0000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2019). Applied Behavior Analysis (3rd Edition). Hoboken, NJ: Pearson Education

- Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical race theory: An introduction. New York: New York University Press.

- Delgado, R., Stefancic, J., & Harris, A. (2012). Critical race theory: An introduction (2nd ed.). NYU Press http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg9h2.

- Dixon M, Dymond S, Rehfeldt RA, Roche B, Zlomke K. Terrorism and relational frame theory. Behavior and Social Issues. 2003;12:129–147. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v12i2.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duttry, C. R. R. (2014). Em(body)ing autonomy: Black women’s bodies and self-liberation in the novels of Zora Neale Hurston and Alice Walker [Honors thesis, University of New Hampshire]. University of New Hampshire Scholars Repository. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/198

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- French K, Golijani-Moghaddam N, Schröder T. What is the evidence for the efficacy of self-help acceptance and commitment therapy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2017;6:360–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gikandi S. Fifty years of Things fall apart (1958) Wasafiri. 2009;24(3):4–7. doi: 10.1080/02690050903019772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldiamond I. Protection of human subjects and patients: A social contingency analysis of distinctions between research and practice, and its implications. Behaviorism. 1976;4(1):1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Calloway A, Roemer L. The buffering effects of emotion regulation in the relationship between experiences of racism and anxiety in a Black American sample. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2015;39:553–563. doi: 10.1007/s10608-015-9682-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greer TM. Coping strategies as moderators of the relationship between race-and gender-based discrimination and psychological symptoms for African American women. Journal of Black Psychology. 2011;37(1):42–54. doi: 10.1177/0095798410380202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D. W. (Director). (1915). Birth of a nation [Film]. Triangle Film Corp.

- Grills C, Aird E, Rowe D. Breathe, baby, breathe: Clearing the way for the emotional emancipation of Black people. Cultural Studies Critical Methodologies. 2016;16(3):333–343. doi: 10.1177/1532708616634839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Towards a unified model of behavior change. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:226–227. doi: 10.1002/wps.20626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S. C., & Smith, S. (2005). Get out of your mind and into your life: The new acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger.

- Helms JE. Fairness is not validity or cultural bias in racial-group assessment: A quantitative perspective. American Psychologist. 2006;61(8):845–859. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberger G. Collective trauma and the social construction of meaning. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:Article 1441. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison DF. Key concepts, theories, and issues in African/Black psychology: A view from the bridge. Journal of Black Psychology. 2018;44(8):722–746. doi: 10.1177/0095798418810596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HL, Cross WE, Defour DC. Race-related stress, racial identity attitudes, and mental health among Black women. Journal of Black Psychology. 2007;33(2):208–231. doi: 10.1177/0095798407299517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, Lee DB, Gaskin AL, Neblett EW. Emotional response profiles to racial discrimination. Journal of Black Psychology. 2013;40(4):334–358. doi: 10.1177/0095798413488628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolu, C. (2020). Cusp emergence. https://cuspemergence.com/

- Langthorne, P., & McGill, P. (2009). A tutorial on the concept of the motivating operation and its importance to application. Behavior analysis in practice, 2(2), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, K., & Keleher, T. (2004). Structural racism. YWCA of Greater Baltimore https://www.ywcagreaterbaltimore.org/images/structural%20racism.pdf.

- Leary-DeGruy, J. (2005). Post traumatic slave syndrome: America’s legacy of enduring injury and healing. Uptone Press.

- Li A. (2020). Solidarity: The Role of Non-Black People of Color in Promoting Racial Equity. Behavior analysis in practice, 14(2), 1–5. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s40617-020-00498-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lincoln T, Marin N, Jaya E. Childhood trauma and psychotic experiences in a general population sample: A prospective study on the mediating role of emotion regulation. European Psychiatry. 2017;42:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattaini M, Holtschneider C. Collective leadership and circles: Not invented here. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2017;37(2):126–141. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2017.1309334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell M, Brevard J, Abrams J, Belgrave F. What’s color got to do with it? Skin color, skin color satisfaction, racial identity, and internalized racism among African American college students. Journal of Black Psychology. 2014;41(5):438–461. doi: 10.1177/0095798414542299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mbilishaka A. PsychoHairapy: Using hair as an entry point into Black women’s spiritual and mental health. Meridians. 2018;16(2):382–392. doi: 10.2979/meridians.16.2.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molina KM, James D. Discrimination, internalized racism, and depression: A comparative study of African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the US. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 2016;19(4):439–461. doi: 10.1177/1368430216641304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J. C. (2020). We want our bodies back: Poems. Amistad.

- Moran, D.J., Ming, S. The Mindful Action Plan: Using the MAP to Apply Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to Productivity and Self-Compassion for Behavior Analysts. Behav Analysis Practice (2020). 10.1007/s40617-020-00441-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ngũgĩ, . T. (1986). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. London: J. Currey.

- Nobles WW. Fundamental task and challenge of Black psychology. Journal of Black Psychology. 2013;39(3):292–299. doi: 10.1177/0095798413478072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, C. E., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1955). The principle of congruity in the prediction of attitude change. Bobbs-Merrill. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pieterse AL, Todd NR, Neville HA, Carter RT. Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59(1):1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0026208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramone J. Towards collective liberation. Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization. 2014;14(4):1049–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts. 10.1037/11256-000

- Smith WD. Editorial. Journal of Black Psychology. 1974;1(1):5–6. doi: 10.1177/009579847400100101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solano-Flores G, Nelson-Barber S. On the cultural validity of science assessments. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 2001;38(5):553–573. doi: 10.1002/tea.1018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solly, M. (2020, June 4). 158 resources for understanding systemic racism in America. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/158-resources-understanding-systemic-racism-america-180975029/

- Spears CA, Houchins SC, Bamatter WP, Barrueco S, Hoover DS, Perskaudas R. Perceptions of mindfulness in a low-income, primarily African American treatment-seeking sample. Mindfulness. 2017;8(6):1532–1543. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0720-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard, J. A., & Afari, N. (2014). The big book of ACT metaphors: A practitioner’s guide to experiential exercises and metaphors in acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

- Taliaferro, J. D., Casstevens, W. J., & Gunby, J. T. D. (2013). Working with African American clients using narrative therapy: An operational citizenship and critical race theory framework. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work, 1, 34–45. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/working-with-african-american-clients-using/docview/1495405324/se-2?accountid=166077

- Tarbox, J., Szabo, T. G., & Aclan, M. (2020). Acceptance and commitment training within the scope of practice of applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice.10.1007/s40617-020-00466-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K. (2017). How we get free: Black feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Haymarket Books.

- The Meaning of Freedom. (n.d.). Alternative Radio. Retrieved from https://www.alternativeradio.org/products/dava013/

- Thiong’o, N. (1986). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. J. Currey; Heinemann.

- Truong KA, Museus SD. Responding to racism and racial trauma in doctoral study: An inventory for coping and mediating relationships. Harvard Educational Review. 2012;82(2):226–254. doi: 10.17763/haer.82.2.u54154j787323302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S. M. & Jones, R. T (1982). Behavior modification and Black populations. In S.M. Turner & R. T. Jones (Eds.),Behavior modification in Black populations(pp. 1–19). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-11544684-4100-0_1.

- Tuwe, K. (2016). The African oral tradition paradigm of storytelling as a methodological framework: Employment experiences for African communities in New Zealand. ECALD https://www.ecald.com/resources/publications/?filter=true.

- Utsey SO. Development and validation of a short form of the Index of Race-Related Stress (IRRS)–Brief Version. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 1999;32(3):149–167. doi: 10.1080/07481756.1999.12068981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Giesbrecht N, Hook J, Stanard PM. Cultural, sociofamilial, and psychological resources that inhibit psychological distress in African Americans exposed to stressful life events and race-related stress. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(1):49–62. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins EJ, Whiting JB, Watson MF, Russon JM, Moncrief AM. Residual effects of slavery: What clinicians need to know. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2012;35(1):14–28. doi: 10.1007/s10591-012-9219-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Printz PD, DeLapp R. Assessing racial trauma with the Trauma Symptoms of Discrimination Scale. Psychology of Violence. 2018;8(6):735–747. doi: 10.1037/vio0000212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MM. Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11(2):203–214. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL, Gaylord SA. The cultural relevance of mindfulness meditation as a health intervention for African Americans. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2014;32(3):147–160. doi: 10.1177/0898010113519010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson A. “Being Black is like being a soldier in Iraq”: Metaphorical expressions of Blackness in an urban community. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 2017;30(2):161–174. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2016.1243269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]