Abstract

The ecological validity of interventions can be enhanced when we first consider the environment in which our students participate. Antecedent interventions such as environmental manipulations can be easily and effectively implemented to enhance student engagement and decrease challenging behaviors in classrooms. The current study explored the use of a measurement system developed for widespread use within a school for students with autism spectrum disorder that helped to inform a classroom-wide environmental manipulation in the form of classroom arrangements. Baseline data across three classrooms suggested high, variable rates of challenging behavior and low rates of engagement with staff and materials. After the introduction of the antecedent intervention, engagement increased and challenging behavior decreased. Helping practitioners develop environmental and systems changes may help to complement individual behavior intervention plans.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, seating arrangement, engagement, environmental manipulation, antecedent intervention

Implementing behavioral interventions in large agencies and school settings can have great impacts on client and student outcomes (e.g., Perry et al., 2008; Tingstrom, Sterling-Turner, & Wilczynski, 2006). However, classroom staff and behavior interventionists can encounter barriers to effectively implementing complex interventions for multiple individuals. An ecological approach to intervention includes first considering the setting in which the students participate to ensure the presence of relevant environmental stimuli that set the occasion for appropriate behaviors. That is, is the environment ready to support the intervention, the teacher, and the student? If the environment is not arranged in such a manner that desired responses can readily be supported for all, then any consequence-based interventions (e.g., reinforcement, punishment) for individual students may be at risk for procedural integrity failures resulting in poor student outcomes.

In contrast to consequence-based strategies, antecedent control procedures involve the manipulation of antecedent stimuli to evoke desirable behaviors (that can later be differentially reinforced) and to decrease challenging behaviors. Setting events are a specific type of contextual stimuli (e.g., complex antecedent condition, event, or stimulus-response interaction) that exert control over other stimulus-response interactions by altering the function of current discriminative stimuli (through a history of differential reinforcement; Sulzer-Azaroff & Mayer, 1991).

When positive behavior change can be achieved through simple manipulations of contextual environmental variables (e.g., staff positioning, seating arrangements, schedule changes), barriers to implementing other behavioral interventions can be decreased or avoided altogether. In their empirical review of literature on environmental manipulations as setting events, Davis and Fox (1999) outlined four types of contextual factors that could serve as setting events: (a) social events (e.g., interactions with peers, teachers); (b) programmatic events (e.g., sequencing of activities and work, choice of task, group vs. individual instruction); (c) biological events (e.g., sleep schedule [see Kennedy & Itkonen, 1993], food deprivation, medications, seizures); and, of particular value to the current study, (d) physical events (e.g., size of classroom, arrangement of furniture [see Bicard, Ervin, Bicard, & Baylot-Casey, 2012; Rosenfield, Lambert, & Black, 1985; Wannarka & Ruhl, 2008], temperature, lighting, materials available [see Doke & Risley, 1972]).

Simple, physical environmental manipulations appear at times to result in increases of appropriate behaviors and help facilitate decreases in recurrent challenging behaviors, as these manipulations of physical materials may serve as setting events because they alter the way in which a student interacts with the environment by either influencing how the stimuli (a) serve an eliciting or discriminative function (antecedent) or (b) serve a reinforcing or punishing function (consequence). To prevent neglect and abuse of day-care children by staff, Twardosz, Cataldo, and Risley (1974) examined the impact of an open environment day-care setting that increased visibility of children and staff. Results of the environmental arrangement suggested that supervision of children was enhanced and sleep patterns and preacademic activities of children were not adversely affected. Furniture rearrangements can be simple interventions that have robust outcomes, as Melin and Götestam (1981) demonstrated enhanced social interaction among older residents in a hospital for individuals with dementia and schizophrenia by simply arranging the furniture in a small coffee room instead of along the wall of the ward corridor. Other studies have examined the effects of student-selected versus teacher-selected seating arrangements for various student populations resulting in mixed outcomes related to student achievement, on-task behavior, and preference (e.g., Bicard et al., 2012; Rosenfield et al., 1985; Schmidt, Stewart, & McLaughlin, 1987; Wannarka & Ruhl, 2008).

The focus of the current study was to extend previous research on the manipulation of physical setting events by examining the effect on classroom engagement and challenging behavior of individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and other disabilities.

Method

Participants and Setting

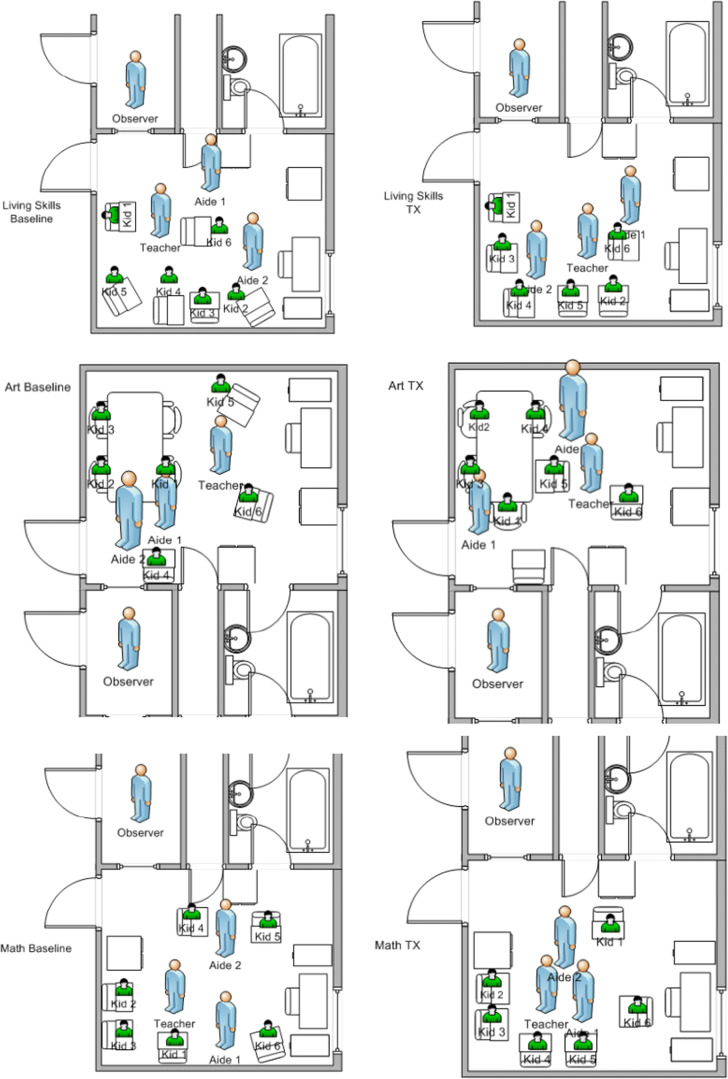

Participants in the current study were elementary students aged 6 years to 10 years (M = 8) attending the school program of an agency serving individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and other disabilities. Each student’s homeroom included six students and one to two teacher aides. Each homeroom transitioned every 30 min to each of eight classrooms for different academic subjects taught by a certified special education teacher. Experimenters observed one homeroom in a sample of three classrooms including art, living skills, and mathematics. This homeroom was chosen based on concerns reported by multiple teachers and the assigned teacher aides with regard to challenging behavior displayed by multiple students. All observations were conducted via a one-way mirror in observation booths (4 ft × 6 ft) that were located between two classrooms (14 ft × 16 ft each; see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Seating charts developed using Microsoft® Visio for each classroom, displaying seating arrangements during baseline (left panel) and treatment (right panel)

Dependent Variables and Data Collection

Engagement with items was defined as the student coming in direct, functional contact with materials or items provided by the teacher. This included educational items such as worksheets, writing utensils, or art supplies, as well as toys and edibles identified as “reinforcing items” that were provided contingent upon completing work assignments. Inappropriate contact with educational or reinforcing items was not included in the definition (e.g., breaking educational materials, mouthing puzzle pieces).

Engagement with staff was defined as the student interacting with the teacher in any of the following ways: (a) appropriate eye contact initiated by staff or the student or (b) any functional verbalization from staff or the student in the form of instruction, question, or praise. Additionally, to meet criteria for engagement with staff, the distance between staff and the student could not exceed 8 ft. Staff talking to other staff and staff engaged in crisis prevention or intervention were excluded from this definition.

Out of seat was defined as any instance, unless otherwise specified by staff, in which the student was not in physical contact with the prescribed seating area.

Experimenters used a handheld computer with customized data collection software designed by the first author. The Engagement Tracker software included a partial-interval recording system that was used to collect data on each homeroom student’s target behaviors in each of the three classrooms. Data were aggregated for all six students for each separate classroom by summing the number of intervals in which each student engaged in a target behavior (e.g., 10 intervals for Student 1 plus 11 intervals for Student 2), then dividing by the total number of possible intervals (i.e., number of 20-s intervals during the session duration multiplied by the number of students). On average, each observation session lasted for 10.25 min (range 5–18 min).

Experimental Design and Procedures

A multiple-baseline across-classrooms design was implemented to assess the effects of the environmental manipulation on the target behaviors for each of three classrooms across baseline and intervention.

Baseline

Experimenters observed each homeroom student in each of the three classrooms and collected data on each target behavior. Experimenters informed staff that they would be observing the students across multiple class periods; however, the experimenters provided no feedback to staff regarding seating arrangements, strategies to increase engagement, or strategies to decrease out-of-seat behavior. Additionally, experimenters documented pretreatment seating arrangements and staff positioning. Once stability was obtained in one classroom, treatment began in that classroom while baseline continued in the other two classrooms.

Intervention

Using Microsoft® Visio Professional software, experimenters created a seating chart based on each student’s needs as identified by baseline data analysis (see Fig. 1). Students who were consistently out of seat during baseline were placed farthest from the door with staff members assigned to positions that would facilitate the prevention of elopement from the room. Students who typically did not initiate interactions with staff or items were seated in closer proximity to staff members and to other clients who showed higher rates of engagement. Experimenters provided the homeroom aide with a copy of the seating chart and explained how the desks and tables should be arranged, where each student should sit, and where staff should stand to maximize the learning environment. Seating charts were different for each classroom due to differences in both seating options and observed target behavior rates across classrooms. Experimenters provided praise to staff at classroom transitions for using the seating chart, but at no point throughout the intervention were any of the specific dependent variables discussed with staff. No additional feedback or seating charts were provided for other classrooms until stability was achieved.

Results and Discussion

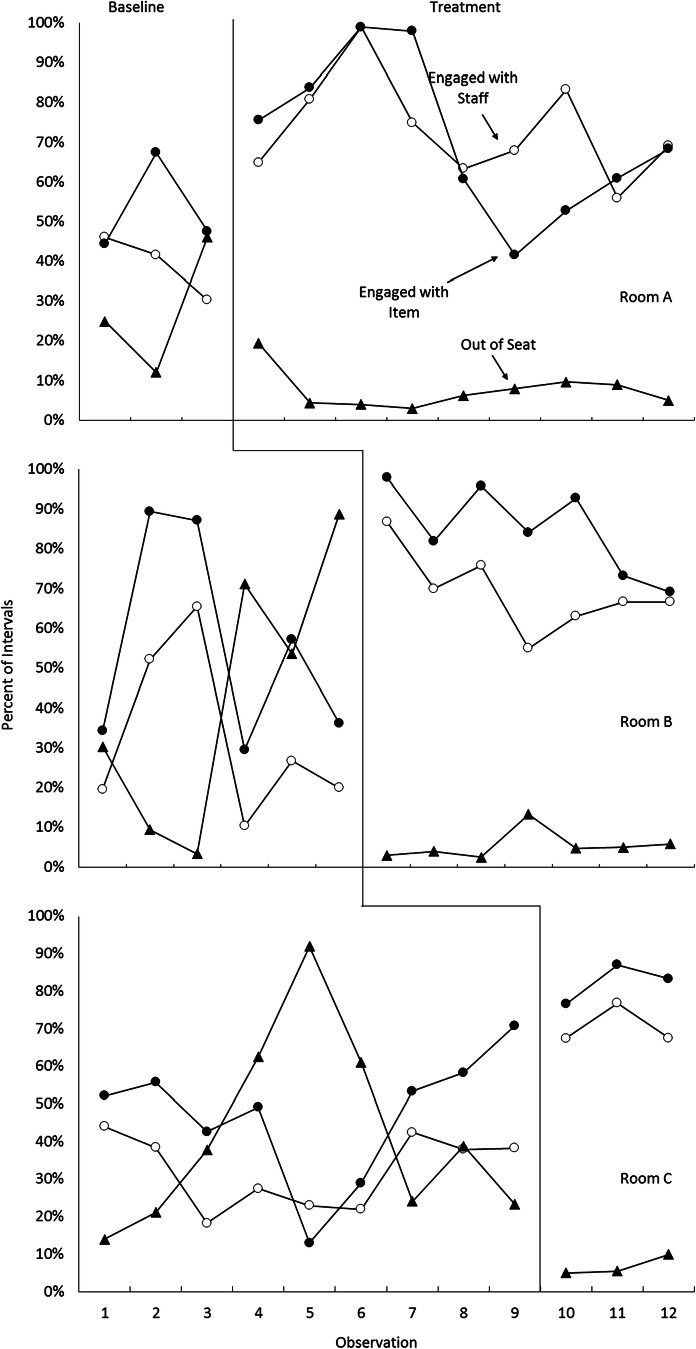

Baseline data indicate that students exhibited low and variable engagement with staff (M = 33.6% of intervals; range 18.3%–65.6% of intervals) and engagement with items (M = 51% of intervals; range 13%–89.4% of intervals) across all three classrooms (see Table 1). Out-of-seat behavior was also variable with countertherapeutic trends for Classrooms B and C (M = 39.7% of intervals; range 3.3%–88.8% of intervals; see Table 1 and Fig. 2). As Fig. 2 displays, when the seating chart intervention was introduced, all three target behaviors improved across all three classrooms. Engagement with staff and engagement with items increased across all three classrooms to an average of 71.4% of intervals (range 55%–99% of intervals) and 78.1% of intervals (range 41.6%–99% of intervals), respectively. Out-of-seat behavior decreased to an average of 6.7% of intervals (range 2.5%–19.4% of intervals) with decreased variability across classrooms.

Table 1.

Average Percentage of Intervals for Target Behaviors During Baseline and Treatment Phases Across All Three Locations

| Room A Averages | Room B Averages | Room C Averages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treatment | Baseline | Treatment | Baseline | Treatment | |

| Eng Staff | 39.4% | 72.7% | 32.4% | 69.2% | 32.5% | 70.6% |

| Eng Item | 53.2% | 70.6% | 55.7% | 85.1% | 47.1% | 82.3% |

| OOS | 27.8% | 8.3% | 42.8% | 5.5% | 41.6% | 6.9% |

Fig. 2.

Aggregate data for all six students during each observation across three classrooms in baseline and treatment phases

Results of the current study suggest positive implications for classrooms due to simple manipulations of environmental variables such as seating arrangements and staff positioning. Manipulating environmental variables in a classroom for students diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and other disabilities may increase engagement and decrease challenging behaviors such as out-of-seat behavior. By setting the stage, and the occasion, for such appropriate behaviors, the saved time could potentially be spent on the individually tailored interventions that may still be required within a clinical or school setting.

Although results demonstrate the effectiveness of a simple yet robust intervention, the current study is not without limitations. First, the two independent data collectors participated in competency-based data collection training involving behavioral skills training to a criterion of at least 90% interobserver agreement across classrooms. However, due to the limited availability of two independent data collectors, there was no formal interobserver agreement data collected for the data presented in the current study. Second, although verbal report from the data collectors indicated that the staff adhered to the seating arrangement, the integrity of the independent variable was not formally assessed on a seating arrangement map or data sheet. Future researchers will want to more formally assess interobserver agreement and procedural integrity of simple environmental manipulations. Third, the aggregate nature of the data analysis presented in the current study may mask the within-subject variability for each student. Although the purpose of the current study was to demonstrate the utility of a systems-level behavior change plan, the individual student data were available to each student’s intervention team and could be reviewed to inform individual behavioral intervention plans. That said, from the aggregate data, we cannot state whether each student’s behavior changed to an equal degree. Fourth, the process for determining and designing the seating arrangements for the current study was not highly formalized. The overall logic employed when positioning staff and students in the current intervention was rooted in setting the occasion and decreasing the response effort for appropriate behaviors while preventing challenging behaviors. This lack of formalization may hinder replication of the methods described in this study. Finally, it is possible that if the present intervention were supplemented with individualized behavioral treatments for each child, then even greater reductions in problem behavior may have occurred. However, not implementing such treatments allowed us to examine the power of the setting event in isolation.

Future researchers may also plan to collect additional data on antecedent and consequent events to help identify a potential functional relationship among (a) eliciting or discriminative stimuli, (b) behavior(s), and (c) reinforcing or punishing stimuli to help determine if the intervention (i.e., seating arrangement) functions as a setting event. In conclusion, although traditional behavioral interventions should always be implemented when necessary to suppress challenging behaviors and improve target positive alternative behaviors, ecological validity of interventions may hold utility as a first-step approach to behavior change. When such setting events increase the probability of challenging behaviors, altering these events alone can have the potential for resulting behavior changes in the absence of any contingency-driven intervention on individual participant behavior. As a result, these data suggest that there is considerable power in a behavioral analysis that expands beyond the three-termed contingency to adopt the contribution of a setting event into the conceptualization of factors that may be sustaining or occasioning challenging behavior.

Author Note

James W. Jackson is now at Kinark Child and Family Services, Ontario, Canada; Sarah M. Dunkel-Jackson is now at Seneca College, Ontario, Canada;

The authors would like to thank Jacquelyn MacDonald for her assistance with data collection.

Funding

No external funding was utilized for completion of this research.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study that involved human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained for participation in this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bicard DF, Ervin A, Bicard SC, Baylot-Casey L. Differential effects of seating arrangements on disruptive behavior of fifth grade students during independent seatwork. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45:407–412. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C. A., & Fox, J. (1999). Evaluating environmental arrangement as setting events: Review and implications for measurement. Journal of Behavioral Education, 9(2), 77–96.

- Doke, L. A., & Risley, T. R. (1972). The Organization of day-care environments: Required vs. optimal activities, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5(4), 405–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kennedy CH, Itkonen T. Effects of setting events on the problem behavior of students with disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:321–327. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin L, Gotestam KG. The effects of rearranging ward routines on communication and eating behaviors of psychogeriatric patients. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14(1):47–51. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A, Cummings A, Dunn Geier J, Freeman N, Hughes S, LaRose L, et al. Effectiveness of intensive behavioral intervention in a large, community-based program. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2008;2:621–642. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2008.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield P, Lambert NM, Black A. Desk arrangement effects on pupil classroom behavior. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1985;77:101–108. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.77.1.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RE. Effects of two classroom seating arrangements on classroom participation and academic responding with Native American junior high school students. Techniques. 1987;3(3):172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer-Azaroff B, Mayer GR. Behavior analysis for lasting change. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tingstrom DH, Sterling-Turner HE, Wilczynski SM. The good behavior game: 1969–2002. Behavior Modification. 2006;30:225–253. doi: 10.1177/0145445503261165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twardosz S, Cataldo MF, Risley TR. Open environment design for infant and toddler day care. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1974;7(4):529–546. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1974.7-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannarka R, Ruhl K. Seating arrangements that promote positive academic and behavioural outcomes: A review of empirical research. Support for Learning. 2008;23:89–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9604.2008.00375.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]