Abstract

The intersectional experiences of Black autistic women and girls (BAWG) are missing from medical and educational research on autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Understanding the intersectional experiences of BAWG is important due to the rising prevalence of autism in Black children and girls (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020) and the concurrent lack of availability of culturally relevant autism-related interventions (Maenner et al., 2020; West et al., 2016). Intersectionality is the study of the overlapping discrimination produced by systems of oppression (Collins, 2019; Crenshaw, 1989, 1991) and allows the researcher to simultaneously address race and disability in special education (Artiles, 2013). In this scoping review, the authors used the PRISMA-ScR checklist (Tricco et al., 2018) and Arskey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework to investigate the degree to which autism-related research (ARR) has included the intersectional experiences of BAWG. Utilizing narrative synthesis, strengths and gaps across the current body of literature are identified in order to set new directions for intersectional ARR. Overall, the authors found that across a 77-year period, three studies foregrounded BAWG and none addressed intersectionality as measured through criteria advanced by García and Ortiz (2013). These results reveal the scholarly neglect BAWG face in ARR, discourse, policy, and practice. A future agenda including research, practice, and policy priorities is identified and discussed.

Keywords: Autism, Intersectionality, Scoping review, Gender, Race, Black, Girl, Woman

Introduction

For the last 77 years, the white male identity has propagated and saturated what is known about autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Matthews, 2019). The exclusion of non-white, nonmale-identified autistic1 individuals in autism-related research (ARR) hinders the ability of the behavior analytic field to meet the needs of the entire autistic population. Since the mid-2000s, examining the role of race and its correlation with autism has dramatically increased. Investigations on disproportionate prevalence (Tincani et al., 2009; Travers et al., 2011), parental perspectives (Barrio et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2020), participation in research (Robertson et al., 2017; Shaia et al., 2020), and intervention success (Davenport et al., 2018) have opened rich conversations on the experiences of racially diverse autistic individuals; however, they have occurred outside of the field of behavior analysis and pale in comparison to the volume of nonintersectional ARR, funding and practice (Pellicano et al., 2018). Autism is clearly a national priority as evidenced by the FY2020 federal spending package of nearly $3 billion in ARR and over $14 billion on autism and IDEA related services (Autism Speaks, 2019). Despite this, Black autistic women and girls (BAWG) remain invisible. There is a need for critical work that utilizes intersectionality to deeply understand the relationships between disability and other marginalized social identities (Artiles, 2013; García & Ortiz, 2013).

Intersectional analysis requires several elements, and chief among them is usable epidemiological evidence (Jaehn et al., 2020). There must be a deeper exploration of how race, ethnicity, and SES affect estimations of ASD diagnoses (Lyall et al., 2017) and an acknowledgement that the current prevalence estimation methods prevent an accurate count of BAWG. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) state that measuring ASD prevalence by gender and race/ethnicity will indicate where identification is incomplete and how policy can “support identification of ASD among subgroups, particularly female and nonwhite children who have historically had lower identified prevalence . . .” (Christensen et al., 2016, pp. 9–10), but research highlighted at the federal level runs contradictory to those goals. The Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee’s 2019 Summary of Advances in Autism Spectrum Disorder Research highlight 20 articles, none of which directly reflect the experiences of BAWG (Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC), 2020). Three articles mention the need for a greater emphasis on disparities in ARR, but none address the specific needs of marginalized autistic individuals. This past and present erasure results in a dangerous triangulation of key elements (e.g., lack of counting, lack of funding, lack of relevant interventions) that have produced a pernicious history for BAWG. This begs the overarching question that governs this scoping review: How does the absence of BAWG in policy and practice affect the representation of BAWG in research?

Exploring Representation

The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is estimated at 1 in 54 children (Maenner et al., 2020). It is classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as “persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across contexts, not accounted for by general developmental delays” that are manifested as deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, and the ability to develop and maintain relationships (DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 50). Recent epidemiological evidence by race indicates nearly identical prevalence estimates in Black2 and white 8-year-old children (Baio et al., 2018), but state-level estimates show persistent gaps in identification (Travers & Krezmien, 2018). For every girl, 4.3 boys are diagnosed with ASD (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020), yet bias (e.g., male-based symptomatology) is presumed to affect this ratio (Halladay et al., 2015). These disparate prevalence numbers have led to compounded barriers for BAWG (e.g., lack of early evaluation, access to ABA therapy and other services; Lovelace et al., 2018; Maenner et al., 2020).

Several systematic reviews document the needs of autistic individuals who are women and/or members of a minority group. They face barriers in accessing services (Smith et al., 2020), increased exposure to environmental factors (Ng et al., 2017), surging health disparities (Bishop-Fitzpatrick & Kind, 2017), expanded structural barriers (Singh & Bunyak, 2018), decreased transition services (Eilenberg et al., 2019), and inadequate gender and nonbinary identity focused services (Glidden et al., 2016; Loomes & Mandy, 2017; Margari et al., 2014; Øien et al., 2018; Van Wijngaarden-Cremers et al., 2014). Despite this convergence of research, the experiences of Black autistic women and girls are absent. The United Nations has explicitly called for intersectionality through its disability inclusion policy (United Nations, n.d.), yet the current research base is unable to support intersectional analysis. Pierce et al. (2014) report that in three preeminent ASD-related journals, 72% of articles had no race or ethnicity descriptors and 54% of articles did not consider ethnicity or race in determining research outcomes or findings. Even more concerning is when race, ethnicity, or nationality (REN) are recorded, white participation dominates reporting. West et al. (2016) found that when REN was reported, 63.5% of those participants were identified as white in comparison to 6.8% who were identified as Black. This deletion of BAWG continues in gender-based autistic-related research. In a 2017 special issue of Autism focused on gender, none of the 18 publications included race as a variable of analysis or a recommended element for future research and only 1 reported the race of participants, who were white. The implicit elimination of BAWG cannot fulfill the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC)(2017) commitment to a “paradigm shift in how we approach autism” (p. vi) that will have a more immediate and direct impact on the daily lives of autistic people. In order to determine the true absence of BAWG from ASD discourse, this scoping review asked the following questions of the literature:

In the past 7 decades, what research features BAWG and what have we learned that directly supports them?

How has ARR allowed us to better understand the experiences of BAWG that are qualitatively different from other autistic individuals?

Reframing Autism: Moving from White Male Normativity to Intersectionality

Pellicano et al. (2018) state that “it is not right that one group holds all of the influence and power” when it comes to autism-related research (ARR; p. 82). There is a certain orthodoxy that is upheld that allows the white male identity in the autism experience to permeate and subsume that of Black autistic women, relegating them as “absent presences of raced and disabled bodies” (Artiles, 2013, p. 331). Racialized, gendered, and ableist conceptualizations foreground a white-normed understanding of autism (Brown, 2017) and elucidate a standardized set of experiences for autistic people. Although the call for intersectionality in special education and disability studies exists (Artiles, 2013; Ben-Moshe & Magaña, 2014; Conner et al., 2016; García & Ortiz, 2013; Gillborn, 2015), few autism-focused researchers (AFR) have responded. Prior to examining the research that centers Black autistic women and girls, it is critical to define intersectionality and frame this review appropriately.

Intersectionality and DisCrit

Intersectionality examines how distinct social structures (i.e., gender or race), “mutually construct each other” (Bowleg, 2008, p. 313) and how disability, race, and gender are interdependent (Annamma et al., 2016; Collins, 2019). Defined as “a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experiences” (Collins & Bilge, 2016, p. 2), intersectionality troubles the notion that identities are discrete or additive (e.g., Black + autistic + woman) and addresses how systems of oppression simultaneously interlock to create new measures of discrimination (Bowleg, 2008; Taylor, 2017). In order to study Black autistic women and girls effectively, intersectionality demands the construction of a new analytical tool that addresses the interdependent, enmeshed nature of this new racialized, gendered, and abled identity. Epistemologies must shift to accurately reflect the experiences of BAWG.

Black women and girls live as racialized beings (Annamma, 2017; Blake et al., 2016; Joseph et al., 2017). Their bodies are policed (Annamma et al., 2019; Epstein et al., 2017; Morris, 2016), their knowledge subjugated (Evans-Winters & Esposito, 2010), and their health ignored (Bishop-Fitzpatrick & Kind, 2017; Townsend et al., 2010). The narratives that pathologize Black women and girls are rooted in a larger set of historical processes that have the predictive power to determine special education eligibility and postsecondary outcomes (Ferri & Conner, 2010). These narratives must be counteracted with critical epistemologies of what disability, Blackness, and gender are and how they are represented through BAWG.

As a theoretical framing for this review, dis/ability3 critical race studies (DisCrit) allows for the dual analysis of race and ability (Annamma et al., 2016). Rooted in critical race theory (CRT) and disability studies (DS), DisCrit provides an interpretive lens to examine practices that are raced, gendered, and ableist (Annamma et al., 2016). With intersectionality at its core, DisCrit affords crucial insights into how the individual-system binary may affect BAWG (Adams & Erevelles, 2016; Annamma et al., 2016). In this review, using DisCrit as our foundation, we systematically scoped the current autism-related evidence base to address the intersectional inclusion of Black autistic women and girls.

Objectives

This scoping review explores peer-reviewed literature that features the experiences of BAWG. The use of systematic reviews in education has grown in response to the demand for a “syntheses of the range, extent, and nature of primary research on particular topics” (Walsh et al., 2019, p. 20). Colquohon et al. (2014) define scoping reviews as a “form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts . . . and gaps in research” (p. 1294). Scoping reviews examine emerging evidence in a particular area and guide future investigations on a topic (Lockwood et al., 2019). Moreover, they are helpful when a topic is complex, diverse, and has not previously been comprehensively reviewed (Sucharew & Macaluso, 2019). We conducted a scoping review to systematically map the intersectional research available on BAWG since classic autism was identified in 1943. Through this review, we identify key concepts, critical social theories, and definitions that should guide future research on BAWG.

Narrative Synthesis

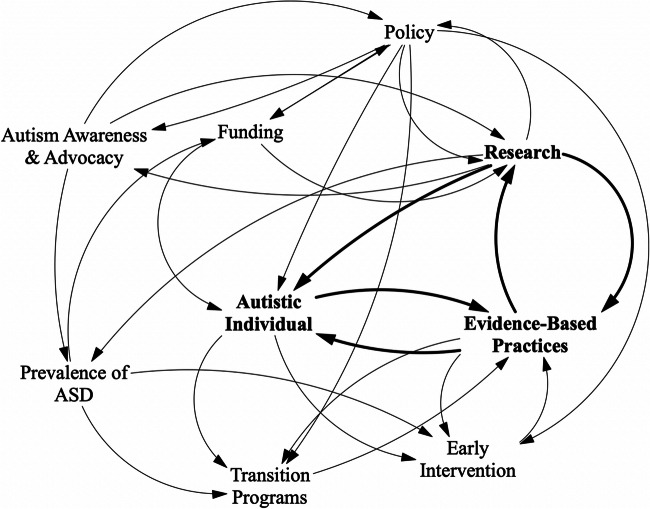

This review interrogates 77 years of autism-related research (ARR) through narrative synthesis. Narrative synthesis has been successful in past scoping reviews of ARR (Dawson-Squabb et al., 2020; Franz et al., 2017) and is helpful when there may be a lack of homogeneity across extracted study designs (Popay et al., 2006). This process guides researchers to: (1) develop a theoretical model of how the interventions work, why and for whom; (2) develop a preliminary synthesis, (3) explore relationships in the data; and (4) assess the robustness of the synthesis product (Popay et al., 2006). We created a nonhierarchical theoretical model (e.g., causal loop diagram) to guide the aims, terms and definitions, and relevant data to be included in this review (Lorenc et al., 2014). Causal loop diagrams, a tool of system dynamics, show the impact of variable changes and disruptions across a system and represent how power mutually constructs social and political structures within a system (Meadows, 2008). System dynamics, a part of systems theory, allows investigators to explore the behavior patterns of a system over time and simultaneously interrogate the interdependent elements of a system to affect change (Hovmand, 2014; Meadows, 2008). Our adapted causal loop diagram in Fig. 1 highlights the three endogenous variables (i.e., autistic individuals, research, and evidence-based practices) that are the focus of this review. This scoping review considered qualitative and quantitative peer-reviewed literature focused on the experiences of BAWG.

Fig. 1.

Adapted causal loop diagram for BAWG theoretical model

Method

Framework for Scoping Review

We conducted this review consistent with two guiding frameworks, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al., 2018) and Arskey and O’Malley’s (2005)five-stage framework for scoping reviews. The Arskey and O’Malley (2005) framework has the following stages: (1) identify the research question; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) chart the data; and (5) collate, summarize, and report the results. The PRIMSA-ScR checklist has 20 essential and 2 optional items.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was an iterative process to ensure that a comprehensive and systematic review was conducted (Walsh et al., 2019). Table 1 includes the search terms and definitions we selected a priori to guide this review.

Table 1.

Terms and definitions used in the scoping review

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Black | Racial classification that includes multigenerational individuals that: identify as Black or African American, are from sub-Saharan African countries, or identify as a part of the modern African diaspora. |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | As defined in the DSM-5, DSM-IV (pervasive developmental disorders [e.g., autistic disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, PDD-NOS), DSM-III(pervasive developmental disorder), and DSM-II (childhood schizophrenia) |

| Woman | As identified due to biological categorization (i.e., sex) or gender identity. |

| Girl | As identified due to biological categorization (i.e., sex) or gender identity. |

The final set of search strings were determined based upon several preliminary searches. Seven disciplinary and interdisciplinary databases (APA PsychARTICLES, APA PsychINFO, ERIC, PubMed, Teacher Reference Center, Academic Search Elite, and Scopus) were searched using the dates January 1, 1943, to February 1, 2020. The search dates corresponded with the seminal articles on autism published by Kanner (1943) and Asperger (1944). Filters were applied for language and publication type. The final search string for Black autistic girls was Black AND Girl* AND Autis* NOT (adhd or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and African American AND Girl* AND Autis* NOT (adhd or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). The one for Black autistic women was nearly identical.

Eligibility criteria

The authors defined the eligibility criteria based upon the keyword search. Publications were considered that: (1) included participants that identified as being Black or African American; (2) included participants that self-identified as a girl or woman; (3) included autistic participants; and (4) available in English. Publications were excluded that: (1) were published before 1943, (2) did not foreground BAWG as participants, (3) did not distill findings specific to the experiences of BAWG, and (4) focused on developmental disabilities in general, not ASD in particular.

Interrater Reliability and Data Extraction

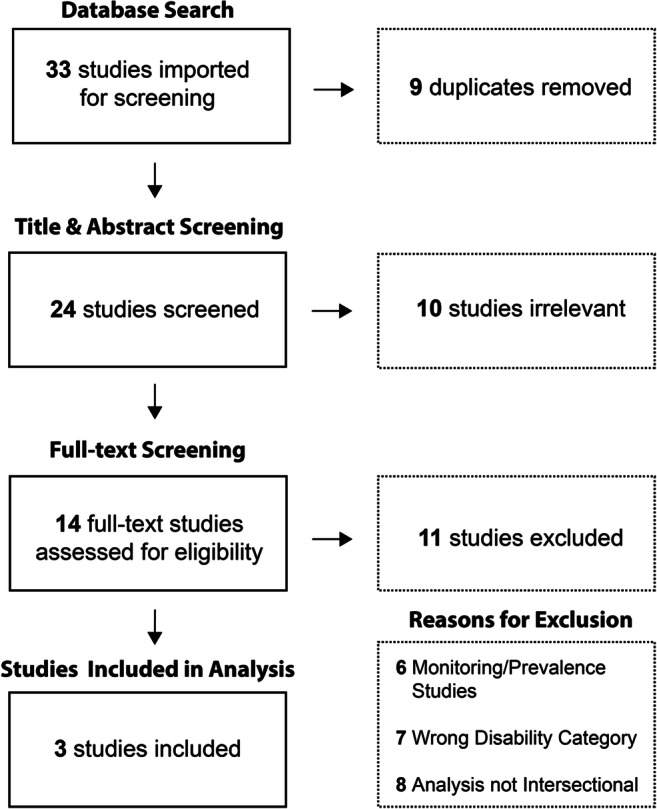

The authors utilized Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, n.d.) for this review. The first two authors were the primary reviewers at each stage and the third author resolved discrepancies. The initial search yielded 37 publications for review. Prior to proceeding with Covidence, 20% of articles (n = 6) retrieved from the initial search were coded by all four authors to establish reliability for study selection. The final search string was revised to exclude “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” and “ADHD” due to number of articles that only focused on ADHD. The updated search yielded 33 publications. After removing duplicates (n = 9) the first two authors proceeded with the review using Covidence. For title and abstract screening, the first and second authors agreed on 13 publications, with 11 disagreements resolved through consensus. After reconciling, 14 publications were forwarded for full text review. Excluded publications at this level consisted of six monitoring reports, a publication describing developmental disabilities broadly, and four publications with single-axis analyses (e.g., race or gender). Three publications were extracted for synthesis. The PRISMA flow diagram for this scoping review is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flow chart

Following screening, three publications were extracted into NVivo for narrative synthesis. All authors conducted a preliminary evaluation to determine the factors to include during extraction and synthesis. Due to the low number of extracted publications, the authors used each publication to create the data fields for extraction. Interextractor reliability, a measure of similar data extracted across reviewers, was 100%.

Intersectional Analysis of Extracted Studies

The first and third authors utilized elements from García and Ortiz’s (2013) guidance for intersectional research as the schema for synthesis. Using the following main anchors of their framework, (1) a deep understanding of the intersections among multicultural/multilingual students, communities and schools and (2) research reflexivity, we chose the following indicators for our synthesis: (1) inclusion of a theoretical framework consistent with intersectionality (e.g., critically rooted theories), (2) descriptions of intervention goals beyond a disability-specific orientation, and (3) evidence of reflexivity that indicates the researcher acknowledges the impact of the broader power structure or system within which the participant is situated.

Limitations of the Current Review

We acknowledge several limitations in this review. First, we did not search grey literature (e.g., dissertations, reports, newsletters), which can be a component of scoping reviews (Paez, 2017) and represent nearly half of the literature in databases (Mahood et al., 2014). Two of the extracted publications (Reinblatt et al., 2006; Wolfberg, 1993) are published conference proceedings and could be argued to represent grey literature. Mahood et al. (2014) suggest that peer-reviewed conference proceedings that appear in commercial publications can be considered peer-reviewed literature. In addition, the Wolfberg (1993) publication references more broad work (e.g., a dissertation, a journal article, and a book) and represents seminal research on integrated play groups, which is a foundational evidence-based practice. Next, our eligibility criteria may have limited the inclusion of research relevant to the broader conversation on gender, race, and disability, which is still worthy of significant investigation. Further, we acknowledge that subjectivity could have affected this review. We did take measures against this with the use of Covidence, the use of three independent reviewers, and employing interrater reliability testing and consensus meetings throughout the process.

There are several limitations due to our search process that may have affected the inclusion of articles in our review. First, we acknowledge the growing number of autistic individuals who have disclosed an ADHD diagnosis and recognize that this co-occurrence should be a priority in future investigations. In this study, we excluded the term “ADHD” in our search string due to the considerable number of articles included in our test searches that featured participants with ADHD and not autism. In addition, the term “female” was not a named term in the search string to foreground self-identified gender and not biological classifications of sex. This may have resulted in the exclusion of viable studies. Even though many titles, abstracts, and keywords do not include specific information regarding study participants’ demographic and diagnostic information, we know that these limitations may have inadvertently overlooked important literature that features the experiences of BAWG.

Results

The results are detailed below for the following areas: (1) descriptive characteristics of the publications and (2) relationships across publications.

Descriptive Characteristics

Descriptive information included in our scope can be found in Table 2. Three publications represent the current research that foreground BAWG. One publication is a peer-reviewed journal article and two are conference proceedings, one of which was published as a journal article. Each of the publications were case studies. One study was conducted in South Africa, one study was conducted in the United States, and the third location is presumed to be the United States due to information included in the study. These publications were published within a 13-year time span (1993–2006)

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics for publications featuring black autistic women and girls

| Authors (publication year) | Number and Name of Participant in Publication | Age at Diagnosis | Diagnosis | Criteria Used for Diagnosis | Age at Intervention | Objectives of intervention | Intervention type | Location of study | Type of publication | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moodley (1992) | 1; None Given [Nandi used as a pseudonym in our reporting] | 2 years and 9 months | Rett Syndrome | Trevathan & Naidu’s (1988) criteria for Rett syndrome | 2 years and 9 months | n/a | n/a; publication describes the diagnosis procedure | South Africa | Journal article | Qualitative (Case Study) |

| Wolfberg (1993) | 1; Teresa | Early years of life* | Autistic disorder* | Rutter’s (1978) criteria for autism | 9–11 years of age (study conducted over two years) | Reciprocal social relations and symbolic representation | Peer play through integrated play groups | United States, California* | Conference proceedings (paper presentation) | Qualitative (Case Study) |

| Reinblatt et al. 2006 | 1; A | 3 years | Autistic disorder | DSM (edition not specified) | 10 years old | Aggression and self-injurious behavior | Loxapine | Not reported | Journal article | Qualitative (Case Study) |

Note. In Wolfberg (1993) the location of the study and specific diagnostic was not included in the publication selected for review. The authors hand searched additional publications focused on the participant to complete the descriptive information for each article. Information found from secondary sources is marked with an asterisk (*).

Relationships across Publications

Each of the publications were case studies that provided information about participants, their diagnostic history, and interventions implemented. A (10 years old), Nandi4 (2 years, 9 months old), and Teresa (9 years old) are the three participants across each of the studies. Two of the three publications reported detailed information about the parents of the girls, including birth information and development prior to diagnosis. Nandi lived with both of her parents, Teresa lived with her grandmother, and A lived with her mother during their participation. Nandi, Teresa, and A’s mothers each reported uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries. Two of the publications reported age at diagnosis, the average just under 3 years of age. Each of the girls were diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorders: Nandi with Rett syndrome and Teresa and A with autistic disorder. A, Nandi, and Teresa were described to have vocal ability, with Nandi and Teresa having limited verbal language that was most prominent from 1 to 2 years old. Nandi and Teresa were receiving school-based special education services at the time of their research participation.

There were no direct relationships found across the interventions implemented in these studies. Moodley (1992) outlined Nandi’s diagnostic process for Rett syndrome and Reinblatt et al. (2006) and Wolfberg (1993), featuring A and Teresa, respectively, focused on interventions. A received Loxapine to reduce her reported aggressive and self-injurious behaviors during a 9-month hospitalization in a psychiatric unit. Teresa participated in an integrative play group, which focused on peer-mediated play to increase imaginative play through reciprocal social interactions and symbolic representation. Teresa participated in this ethnographic interpretive case study for 10 years, however, a 2-year period from ages 9 to 11, were the focus of the Wolfberg (1993) publication.

Evidence of Intersectionality

We assessed intersectionality across three domains: (1) evidence of an intersectional theoretical framework, (2) evidence of person-centered, identity-first participant descriptions and intervention goals, and (3) evidence of research reflexivity (García & Ortiz, 2013). There was no evidence of intersectionality in any of the publications. None of the publications included a theoretical framework to guide their research. Each of the publications included in-depth case information on A, Nandi, and Teresa’s background and previous experiences, with A and Nandi described from a disability-specific, deficit-based orientation. Information about Teresa in the Wolfberg (1993) publication was brief, however, person-centered descriptions were found in related publications suggested by P. J. Wolfberg (personal communication, June 2, 2020). Evidence of research reflexivity was found in related publications (Wolfberg, 1994, 2009), but not in the 1993 publication. There was no evidence of research reflexivity in the Moodley (1992) or Reinblatt et al. (2006) publications. In large measure, the three publications included in this review failed to effectively address intersectionality and reflect the need for intersectional BAWG representation in ARR.

Discussion

The results of this scoping review highlight the scholarly neglect of BAWG in special education research. Organized by the aims of the review, the experiences of A, Nandi, and Teresa highlight how the field has failed BAWG, how we must address the unique experiences of BAWG, and set the occasion for us to introduce the new tenets of a broad intersectional research and practice agenda for BAWG.

The publications that feature A, Nandi, and Teresa included diverse publication types. In order to represent A and Teresa’s experiences in this review, we included publications that could be considered grey literature. As case studies, these publications did not have the same components as experimental research, but they provide insight into a set of phenomena in a bounded context (Miles et al., 2014). Case studies can serve as counterstories to resist deficit-based, white normative narratives (Berry & Cook, 2019) and are a useful intersectional tool, especially when coupled with experimental research (West et al., 2016). For caregivers and behavior analysts, case studies can provide crucial information that can be used in intervention selection. A, Nandi, and Teresa give us crucial information through their experiences and simultaneously signal the need for increased attention to serve BAWG better.

The Complexity of an Absent Narrative

A, Nandi, and Teresa were diagnosed under the retired diagnostic criteria (Young & Rodi, 2014) associated with pervasive developmental disorders (e.g., autistic disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, Rett syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified [PDD-NOS]). A and Nandi received their diagnoses at approximately 3 years of age and Teresa in early childhood. This is comparable to that of Black autistic boys (Lovelace et al., 2018). In addressing their shared characteristics, each publication reported diminishing vocal language and for Nandi, this regression is what prompted the evaluation for Rett syndrome. In addition, A and Nandi engaged in stereotypic behavior, which are repetitive, uncontrolled movements that are often maintained by automatic reinforcement (Quest et al., 2014). These shared characteristics are helpful to note as behavior analysts in order to differentiate and catalog initial indicators of this spectrum-based disability for Black autistic girls. Intervention information is also important to classify. A and Teresa’s interventions targeted social behavior, a common focus for autistic individuals. In Wong et al.'s (2014) comprehensive review of 27 evidence-based practices widely used for autistic individuals, 6 of the 27 practices are associated with mediating social behavior, including integrated play. Wolfberg (1993) reports that Teresa had an increase in her social relations with others and engaged in less isolated and more sustained interactions with peers. A’s outcomes were also reported as positive, with concerning caveats. Although A's prosocial behavior, academic skills, and therapeutic skills increased, her treatment experience is reminiscent of the troubled legacy of Black people and medical institutions (Gill & Erevelles, 2017). Reported as her first hospitalization, Reinblatt et al. (2006) admit that there were several challenges in finding an effective treatment for A. Absent a complete evaluation, A was exposed to a series of antipsychotics to reduce her aggression and self-injurious behavior. Although antipsychotics have been used with increasing frequency for autistic children and adults (Hellings et al., 2017), no medication has been proven to be effective in treating the core symptoms of ASD (Goel et al., 2018). A’s experiences serve as the proverbial canary in the coal mine concerning Black children and pharmacotherapy. Logan et al. (2014) suggest pharmacotherapy for use with Medicaid-eligible autistic children who outnumber the state’s capacity to provide behavioral intervention. This is troubling, for they base this on prior studies seeking improved medication adherence with minoritized children (Bussing et al., 2003; Chavira et al., 2003; Fontanella et al., 2011; Patel et al., 2005) omitting a crucial discussion on the systemic factors related to the lack of treatment adoption. As autism-focused researchers, the dichotomy between A and Teresa’s experiences highlight a desultory BAWG narrative. With nearly a decade between their experiences, A and Teresa, at nearly the same age, with similar family, diagnostic, and educational backgrounds, stimulate several ontological questions as to the true progress that has been achieved in ARR for BAWG that must guide our way forward.

A Clarion Call for Intersectional ARR

The experiences of A, Nandi, and Teresa should shake the foundation of ARR, amplifying the epistemological and ethical conflicts the current system is creating for BAWG. By exploring the gaps in ARR that our intersectional analysis reveal, A, Nandi, and Teresa can help us to set a new agenda for research and practice. García and Ortiz’s (2013) guidance suggests that incorporating theory, using identity-focused comprehensive participant descriptions, and including research reflexivity will better address the needs of BAWG. For intervention research, theoretical frameworks provide an understanding of the intervention study aims as well as support the translation of findings (Moore et al., 2019; Moore & Evans, 2017; Wolcott et al., 2019). Theory ties together a body of knowledge that “organizes, describes, predicts, and explains a phenomenon” (Fleury & Sidani, 2012, p. 11). It expands the knowledge base for clinical practice, fosters the systematic development of an intervention, and grounds the intervention in a larger justice structure (Fleury & Sidani, 2012; Moore et al., 2019). Although not widely used in intervention research (Fleury & Sidani, 2012), theoretical frameworks ground the research aims (Creswell & Poth, 2018) and provide context to findings (Miles et al., 2014). That context allows us to choose culturally relevant, identity affirming behavior analytic interventions. However, in these three studies, the lack of a theoretical frame prevented a deeper analysis into the role of race and gender in intervention choice and success; keeping intervention as an action separate from each girls’ identity. Moore and Evans (2017) challenge intervention researchers to “move away from viewing interventions as discrete packages of components which can be described in isolation from their contexts, [but as a way to] understand the systems into which change is being introduced” (p. 132). Using intersectionality in ARR would provide fresh insights into the dynamics and mechanisms shaping Black lives, acting as an analytic tool to shift ARR from being passive to active and allowing practitioners to understand and analyze the complexity in autistic people and in their experiences (Collins & Bilge, 2016).

This complexity, the second indicator, includes addressing the cultural, linguistic, and sociopolitical referents of the participants (García & Ortiz, 2013). Race, gender, and disability, along with comprehensive background information were named for A and Nandi, however, they reflected a medical model approach. What did we glean from these articles that was materially different than if they were white autistic boys? As Collins (2019) suggests, naming a social identity does not occasion intersectionality. Without proper analysis, readers are left to assume how A, Nandi, and Teresa’s race, gender, and disability coalesce as a mediating variable in the intervention.

Erasing the social identities of A and Nandi also occasion what García and Ortiz (2013) call blame[ing] the victim. Abled descriptions of A during intake set a disturbing narrative for BAWG. A is described as, “aloof,” “uncooperative,” “irritable, or “difficult,” and her autism was considered an illness (Reinblatt et al., 2006, p. 640). When describing the available interventions for A, nonpharmacologic interventions were dismissed as a potential treatment due to “extremely limited cognitive and verbal skills and comprehension difficulties” (Reinblatt et al., 2006, p. 642). Language use is critical when describing Black girls, especially when referencing behavior. In Girlhood Interrupted, Epstein et al. (2017) caution that adults use “stereotypical images of Black females . . . to interpret Black girls’ behaviors and respond more harshly to Black girls who display behaviors that do not align with traditional standards. . .” (p. 5). This bias can enter into clinical judgment, diagnosis, assessment, and hypothesis setting and confirmation (Garb, 1997; Neighbors et al., 2003), and for Black girls, leads to adultification (Epstein et al., 2017). For Black girls with multiple marginalized identities, like A, Nandi, and Teresa, this bias creates perceptions of threat, noncompliance, and harm (Annamma et al., 2019), and set the stage for the tropes of disability and race to converge and crystalize as the predominant narrative of their experience.

Research reflexivity encourages autism-focused researchers and behavior analysts to consider the implications of how we design, implement, and describe our research and intervention plans. Using axiology, ontology, and epistemology as a foundation, reflexivity encourages an examination of the repertoires and ideologies that create the normative frames that guide ARR (García & Ortiz, 2013). Defined as positionality, this allows for the interrogation of power in relationship to our social identities and those of BAWG and how the proposed research or practice furthers or prohibits future marginalization (Milner, 2007). A lack of research reflexivity can induce controlling images, which are “designed to make racism [and] sexism . . . appear to be natural, normal, and inevitable parts of everyday life” (Collins, 2000, p. 69). A’s behavioral descriptions could serve as controlling images for Black autistic girls and become a natural, normal, and inevitable depiction.

Moving Forward in Advancing Knowledge about Black Autistic Women and Girls

Our 77-year scope shows that there is still more work to do; thus, we recommend several broad research, practice, and policy priorities to push BAWG inclusion forward. Undergirding these priorities is a full framework for intersectional autism-related research and practice. Building upon García and Ortiz’s (2013) recommendations, ARR must: (1) use a critically based theoretical framework; (2) use identity-first, comprehensive participant descriptions and intervention goals; (3) include research(er) reflexivity; (4) foreground the sociocultural identities of participants; (5) contain an intersectional analysis of research findings; and (6) contextualize research affect in the broader dynamic system that surrounds autistic individuals.

Research Priorities

Future autism-focused research (AFR) must prioritize BAWG. To accomplish this, an accurate identification of Black autistic girls, an accurate understanding of their core ASD characteristics, and a commitment to identity affirming evidence-based interventions are required. Autism-focused researchers must generate these culturally relevant interventions through mixed methods research to better capture the lived experiences of BAWG. Understanding the impact of race on diagnostic criteria, intervention compatibility, and the larger structural inequities for BAWG is critical to providing comprehensive support across their lifespan.

Practice Priorities

The most salient practice priority for BAWG is the removal of practices that have been deemed harmful by autistic individuals (Lewis, 2020). This includes those that have been identified in behavior analysis. In addition, more relevant ASD diagnostic criteria and procedures are needed. This will arm behavior analysts with the tools they need for culturally relevant practice and caregivers with tools they need to support their children. In addition, practitioners must interrogate if their practices support BAWG, by including caregivers as experts in treatment design and utilizing practices that center their cultural beliefs (Čolić et al., 2021; Mandell & Novak, 2005). Deficit models envelop how we approach autism intervention (Dinishak, 2016) for BAWG and we must shift to expand our understanding of their experiences, especially if they have co-occurring diagnoses. Through this we can dismantle the norms and structures that oppress BAWG and restrict culturally relevant practice.

Policy Priorities

The structural changes needed to support BAWG must also address policy. The CDC noting disparities (Christensen et al., 2016) and the UN (United Nations, n.d.) naming intersectionality as critical to practice start this discussion. We suggest, as policy priorities for BAWG, that the federal government name intersectionality as a needed component for all federally funded ARR. In addition, federally authorized research funding to address the needs of Black autistic women and girls is crucial. The significance of these priorities will allow for the public shaping of autism research and practice for BAWG and will reprioritize them as vanguards of a new intersectional movement for autistic individuals who currently sit at the unique, mutually established spaces of pride, identity, and liberation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nicole M. Joseph (Vanderbilt University) for her contribution in the critical reading of this manuscript.

Funding

No external funding was received for the research reported in this article.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Footnotes

The authors are utilizing the preference of many autistic individuals to not use person-first language, but to use identity-first language as described by a Chinese, East Asian Autistic person (Brown, 2011a, 2011b) and a Black autistic woman (K. Smith, personal communication, March 20, 2020).

Within the African diaspora, self-identification as Black, African American, Afro-Latinx, and other identity markers are often a personal matter (Cross, 1991). For the purposes of this review, we use Black as an inclusive term to represent all members of the African diaspora.

“Dis/ability” written with the forward slash is employed by Annamma in order to “analyze the entire context in which a person functions” (Annamma et al., 2016, p. 1) and to acknowledge that “dis/ability is not a thing to find and fix, but a process” (Annamma, 2017, p. 7). Moreover, Annamma (2017) states that disability without the forward slash centers ability as the normative experience (dis = not, ability = able).

Nandi is a pseudonym we are using to hold space in acknowledgement for this participant’s contribution to this emerging research area. She is unnamed in the original publication.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams DL, Erevelles N. Shadow play: DisCrit, dis/respectability, and carceral logics. In: Connor DJ, Ferri BA, Annamma SA, editors. DisCrit: Disability studies and critical race theory in education. Teachers College Press; 2016. pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Annamma SA. The pedagogy of pathologization: Dis/abled girls of color in the school-prison nexus. Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Annamma SA, Connor DJ, Ferri BA. Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. In: Connor DJ, Ferri BA, Annamma SA, editors. DisCrit: Disability studies and critical race theory in education. Teachers College Press; 2016. pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Annamma SA, Anyon Y, Joseph NM, Farrar J, Greer E, Downing B, Simmons J. Black girls and school discipline: The complexities of being overrepresented and understudied. Urban Education. 2019;54(2):211–242. doi: 10.1177/0042085916646610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arskey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Artiles AJ. Untangling the racialization of disabilities: An intersectionality critique across disability models. DuBois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2013;10(2):329–347. doi: 10.1017/s1742058x13000271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asperger H. Die “Autistischen Psychopathen” im kindesalter. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankenheiten. 1944;117:76–136. doi: 10.1007/bf01837709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Autism Speaks. (2019, December 27). FY20 Federal budget strengthens support for autism [Press Release]. https://www.autismspeaks.org/advocacy-news/fy20-federal-budget-strengthens-support-autism. Accessed 14 May 2020

- Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Daniels, J. Warren, Z., Kurzius-Spencer, M., Zahorodny, W., Rosenberg, C. R., White, T., Durkin, M. S., Imm, P., Nikolaou, L., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Lee, L., Harrington, R., Lopez, M., Fitzgerald, R. T., Hewitt, A. . . . Dowling, N. F. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1–23. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Barrio BL, Hsiao Y, Prisker N, Terry C. The impact of culture on parental perceptions about autism spectrum disorder: Striving for culturally competent practices. Multicultural Teaching & Learning. 2018;14(1):1–9. doi: 10.1515/mlt-2016-0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Moshe L, Magaña S. An introduction to race, gender, disability studies, and families of color. Women, Gender, & Families of Color. 2014;2(2):105–112. doi: 10.5406/womgenfamcol.2.2.0105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry TR, Cook EJB. Critical race perspectives on narrative research in education: Centering intersectionality. In: DeCuir-Gunby JT, Chapman TK, Schutz PA, editors. Understanding critical race research methods and methodologies. Routledge; 2019. pp. 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Kind AJH. A scoping review of health disparities in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2017;47(11):3380–3391. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake JJ, Zhou Q, Kwok O, Benz MR. Predictors of bullying behavior, victimization, and bully-victim risk among high school students with disabilities. Remedial & Special Education. 2016;37(5):285–295. doi: 10.1177/0741932516638860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–325. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. X. Z. (2011a, August 4). The significance of semantics: Person-first language: Why it matters?. Autistichoya.com, https://www.autistichoya.com/2011/08/significance-of-semantics-person-first.html. Accessed 16 May 2020

- Brown, L. X. Z. (2011b, November 28). Identity and hypocrisy: A second argument against person-first language. Autistichoya.com, https://www.autistichoya.com/2011/11/identity-and-hypocrisy-second-argument.html. Accessed 16 May 2020

- Brown LXZ. I, too, am racialized. In: Brown LXZ, Ashkenazy E, Onaiwu MG, editors. All the weight of our dreams: On living with racialized autism. Dragon Bee; 2017. pp. 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Gary FA, Mills TL, Garvan CW. Parental explanatory models of ADHD: Gender and cultural variation. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38(10):563–575. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0674-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC). (2020, May 18). Autism Data Visualization Tool.https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data/index.html

- Chavira D, Stein MB, Bailey K, Stein MT. Parental opinions regarding treatment for social anxiety disorder in youth. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2003;24(5):315–322. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DL, Baio J, Braun KVN, Bilder D, Charles J, Constantino JN, Daniels J, Durkin MA, Fitzgerald RT, Kurzius-Spencer M, Lee L, Pettygrove S, Robinson C, Schulz E, Wells C, Wingate MS, Zahorodny W, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2016;65(13):1–23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Čolić, M., Araiba, S., Lovelace, T. S., & Dababnah, S. (2021). Black caregivers’ perspectives on racism in ASD services: Towards culturally responsive ABA practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 10.1007/s40617-021-00577-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH. Intersectionality as critical social theory. Duke University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH, Bilge S. Intersectionality. Polity; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Colquohon HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, Kastner M, Moher D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67:1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner DJ, Ferri BA, Annamma SA, editors. DisCrit: Disability studies and critical race theory in education. Teachers College Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersections of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;1:139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review. 1991;43(6):1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, W. E., Jr. (1991). Shades of black: Diversity in African-American identity. Temple University Press

- Davenport M, Mazurek M, Brown A, McCollum E. A systematic review of cultural considerations and adaptation of social skills interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2018;52:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Squabb J, Davids EL, Harrison AJ, Molony MA, DeVries PJ. Parent education and training for autism spectrum disorders: Scoping the evidence. Autism. 2020;24(1):7–25. doi: 10.1177/1362361319841739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinishak, J. (2016). The deficit view and its critics. Disability Studies Quarterly, 36(4). 10.18061/dsq.v36i4.5236

- Eilenberg JS, Paff M, Harrison A, Long KA. Disparities based on race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status over the transition to adulthood among adolescents and young adults on the autism spectrum: A systematic review. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2019;21:32–48. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, R., Blake, J. J., & González, T. (2017). Girlhood interrupted: The erasure of Black girls’ childhood. Georgetown Law Center on Poverty & Inequality. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/poverty-inequality-center/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2017/08/girlhood-interrupted.pdf

- Evans-Winters VE, Esposito J. Other people’s daughters: Critical race feminism and black girls’ education. Educational Foundation. 2010;24(1–2):11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri B, Conner DJ. ‘I was the special ed. girl’: Urban working-class young women of colour. Gender & Education. 2010;22:105–121. doi: 10.1080/09540250802612688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleury, J., & Sidani, S. (2012). Using theory to guide intervention research. In B. M. Melnyk & D. Morrison-Beedy (Eds.), Intervention research: Designing, conducting, analyzing, and funding. Springer Publishing Company (pp. 11–36). 10.1891/9780826109583.0002

- Fontanella CA, Bridge JA, Marcus SC, Campo JV. Factors associated with antidepressant adherence for Medicaid-eligible enrolled children and adolescents. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2011;45:898–909. doi: 10.1345/aph.1q020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz L, Chambers N, von Isenberg M, de Vries PJ. Autism spectrum disorder in sub-Saharan Africa: A comprehensive scoping review. Autism Research. 2017;10(5):723–749. doi: 10.1002/aur.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garb HN. Race bias, social class bias, and gender bias in clinical judgment. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 1997;4(2):99–120. doi: 10.1111/j.14682850.1997.tb00104.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García SB, Ortiz AA. Intersectionality as a framework for transformative research in education. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners. 2013;13(2):32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gill M, Erevelles N. The absent presence of Elsie Lacks: Hauntings at the intersection of race, class, gender, and disability. African American Review. 2017;50(2):123–137. doi: 10.1353/afa.2017.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillborn D. Intersectionality, critical race theory, and the primacy of racism: Race, class, gender, and disability in education. Qualitative Inquiry. 2015;21(3):277–287. doi: 10.1177/1077800414557827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glidden D, Bouman WP, Jones BA, Arcelus J. Gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Sexual Medicine Reviews. 2016;4(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel R, Hong JS, Findling RL, Ji NY. An update on pharmacotherapy of autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. International Review of Psychiatry. 2018;1:78–95. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1458706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halladay AK, Bishop S, Constantino JN, Daniels AM, Koenig K, Palmner K, Messinger D, Pelphrey K, Sanders SJ, Singer AT, Taylor JL, Szatmari P. Sex and gender differences in autism spectrum disorder: Summarizing evidence gaps and identifying emerging areas of priority. Molecular Autism. 2015;6(36):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0019-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellings JA, Arnold LE, Han JC. Dopamine antagonists for treatment resistance in autism spectrum disorders: Review and focus on BDNF stimulators loxapine and amitriptyline. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2017;6:581–588. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2017.1308483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovmand PS. Community based system dynamics. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC). (2017). 2016-2017 Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee strategic plan for autism spectrum disorder. https://iacc.hhs.gov/publications/strategic-plan/2017/

- Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC). (2020). 2019 IACC Summary of advances in autism spectrum disorder research. https://iacc.hhs.gov/publications/summary-of-advances/2019/

- Jaehn, P., Rehling, J., Klawunn, R., Merz, S., & Holmberg, C. (2020). Practice of reporting social characteristics when describing representativeness of epidemiological cohort studies: A rationale for an intersectional perspective. SSM—Population Health, 11, 1–9. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Joseph NM, Hailu M, Boston D. Black women’s and girls’ persistence in the P-20 mathematics pipeline: Two decades of children, youth, and adult education research. Review of Research in Education. 2017;41:203–227. doi: 10.3102/0091732x16689045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Dababnah S, Lee J. The influence of race and ethnicity on the relationship between family resilience and parenting stress in caregivers of children with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2020;50:650–658. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K. R. (2020, July 1). Autism is an identity, not a disease: Inside the neurodiversity movement. https://elemental.medium.com/autism-is-an-identity-not-a-disease-inside-the-neurodiversity-movement-998ecc0584cd. Accessed 8 July 2020

- Lockwood C, dos Santos KB, Pap R. Practical guidance for knowledge synthesis: Scoping review methods. Asian Nursing Research. 2019;13(5):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan SL, Carpenter L, Leslie RS, Hunt KS, Garrett-Mayer E, Charles J, Nicholas JS. Rates and predictors of adherence to psychotropic medications in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2014;44:2931–2948. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomes R, Mandy WPL. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc, T., Petticrew, M., Whitehead, M., Neary, D., Clayton, S., Wright, K., Thomson, H., Cummins, S., Sowden, A., & Renton, A. (2014). Crime, fear of crime and mental health: Synthesis of theory and systematic reviews of interventions and qualitative evidence. Public Health Research, 2(2), 1–400. 10.3310/phr02020 [PubMed]

- Lovelace TS, Robertson RE, Tamayo S. Experiences of African American mothers of sons with autism spectrum disorder: Lessons for improving service delivery. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities. 2018;53(1):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lyall K, Croen L, Daniels J, Fallin MD, Ladd-Acosta C, Lee BK, Park BY, Snyder NW, Schendel D, Volk H, Windham GC, Newschaffer C. The changing epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annual Review of Public Health. 2017;38:81–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner, M. J., Shaw, K.A., Baio, J., Washington, A., Patrick, M., DiRienzo, M., Christensen, D.L, Wiggins, L.D., Pettygrove, S., Andrews, J.G., Lopez, M. Hudson, A., Baroud, T., Schwenk, Y., White, T., Rosenberg, C.R., Lee, L., Harrington, R.A., Huston, M. . . . Dietz, P.M. (2020). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. Surveillance Summaries, 69(4), 1–12. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mahood Q, Van Eerd D, Irvin E. Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: Challenges and benefits. Research Synthesis Methods. 2014;5:221–234. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Novak M. The role of culture in families’ treatment decisions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Mental Retardation & Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2005;11:110–115. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margari L, Lamanna AL, Craig F, Simone M, Gentile M. Autism spectrum disorders in XYY syndrome: Two new cases and systematic review of the literature. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;173:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews M. Why Sheldon Cooper can’t be Black: The visual rhetoric of autism and ethnicity. Journal of Literacy & Cultural Disability Studies. 2019;13(1):57–72. doi: 10.3828/jlcds.2019.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows DH. Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Juberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis. Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Milner HR., IV Race, culture, and researcher positionality: Working through dangers seen, unseen, and unforeseen. Educational Researcher. 2007;36(7):388–400. doi: 10.3102/0013189x07309471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moodley M. Rett syndrome in South Africa. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics. 1992;1(4):409–415. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1992.11747607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GF, Evans RE. What theory, for whom and in which context? Reflections on the application of theory in the development and evaluation of complex population health interventions. SSM—Population Health. 2017;3:132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore G, Cambon L, Michie S, Arwidson P, Ninot G, Ferron C, Potvin L, Kellou N, Charlesworth J, Alla F. Population health intervention research: The place of theories. Trials. 2019;20(285):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3383-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MW. Pushout: The criminalization of Black girls in schools. New Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Trierweiler SJ, Ford BC, Muroff JR. Racial differences in DSM diagnosis using a semi-structured instrument: The importance of clinical judgment in the diagnosis of African Americans. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2003;44(3):237–256. doi: 10.2307/1519777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, de Montigny JG, Ofner M, Docé MT. Environmental factors associated with autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review for the years 2003–2013. Health Promotion & Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada. 2017;37(1):1–23. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.37.1.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Øien RA, Cicchetti D, Anders N. Gender dysphoria, sexuality, and autism spectrum disorders: A systematic map review. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(12):4028–4037. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez A. Gray literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence Based Medicine. 2017;10(3):233–240. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NC, DelBello MP, Keck PE, Jr, Strakowski SM. Ethnic differences in maintenance antipsychotic prescription among adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2005;16(6):938–946. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicano L, Mandy W, Böelte S, Stahmer A, Taylor JL, Mandell DS. A new era for autism research. Autism. 2018;22(2):82–83. doi: 10.1177/1362361317748556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce NP, O’Reilly MF, Sorrells AM, Fragale CL, White PJ, Aguilar JM, Cole HA. Ethnicity reporting practices for empirical research in three autism related journals. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2014;44:1507–1519. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006, December 22). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic review. A product from the ESRC Methods Programme (Unpublished report). Lancaster, UK: Lancaster University.

- Quest KM, Byiers BJ, Payen A, Symons FJ. Rett syndrome: A preliminary analysis of stereotypy, stress, and negative affect. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35(5):1191–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinblatt SP, Abanilla PK, Jummani R, Coffey B. Loxapine Treatment in an autistic child with aggressive behavior: Therapeutic challenges. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2006;16(5):639–643. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RE, Sobeck EE, Wynkoop K, Schwartz R. Participant diversity in special education research: Parent-implemented behavior interventions for children with autism. Remedial & Special Education. 2017;38(5):259–271. doi: 10.1177/0741932516685407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. (1978). Diagnosis and definitions of childhood autism. Journal of Autism & Childhood Schizophrenia, 8(2), 139–161. 10.1007/BF01537863 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shaia WE, Nichols HM, Dababnah S, Campion K, Garbarino N. Brief report: Participation of Black and African-American families in autism research. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2020;50:1841–1846. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JS, Bunyak G. A systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2018;29(6):796–808. doi: 10.1177/1049732318808245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KA, Gehricke J, Iadarola S, Wolfe A, Kuhlthau KA. Disparities in service use among children with autism: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):35–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1895g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucharew H, Macaluso M. Methods for research evidence synthesis: The scoping review approach. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2019;14(7):416–418. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KY. How we get free: Black feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Haymarket Books; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tincani M, Travers J, Boutot A. Race, culture, and autism spectrum disorder: Understanding the role of diversity in successful educational interventions. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2009;24(3–4):81–90. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.34.3-4.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend TG, Neilands TB, Thomas AJ, Jackson TR. I’m no Jezebel, I am young, gifted, and black: Identity, sexuality, and Black girls. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2010;34:273–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01574.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JC, Krezmien MP. Racial disparities in autism identification in the United States during 2014. Exceptional Children. 2018;84(4):403–419. doi: 10.1177/0014402918771337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JC, Tincani M, Krezmien MP. A multiyear national profile of racial disparity in autism identification. Journal of Special Education. 2011;47(1):41–49. doi: 10.1177/0022466911416247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trevathan, E. & Naidu, S. (1998). The clinical recognition and differential diagnosis of Rett Syndrome. Journal of Child Neurology, 3(1), S6-S16. 10.1177/0883073888003001S03 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C., Lillie, E., Wasifa, Z., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D. Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E.A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Macdonald, M. T., Langlois, E. V. . . . Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/m18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed]

- United Nations. (n.d.). Disability inclusion strategy. https://www.un.org/en/content/disabilitystrategy/assets/documentation/UN_Disability_Inclusion_Strategy_english.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2020

- Van Wijngaarden-Cremers PJM, van Eeten E, Groen WB, Van Deurzen PA, Oosterling IJ, Van der Gaag RJ. Gender and age differences in the core triad of impairments in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2014;44:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1913-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. (n.d.). Covidence systematic review software.https://www.covidence.org/

- Walsh K, Howard S, Hand K, Ey L, Fenton A, Whiteford C. What is known about initial teacher education for child protection? A protocol for a systematic scoping review. International Journal of Educational Methodology. 2019;5(1):19–33. doi: 10.12973/ijem.5.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West EA, Travers JC, Kemper TD, Liberty LM, Cote DL, McCollow MM, Brusnahan LLS. Racial and ethnic diversity of participants in research supporting evidence-based practices for learners with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Special Education. 2016;50(3):151–163. doi: 10.1177/0022466916632495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott MD, Lobczowski NG, Lyons K, McLaughlin JE. Design-based research: Connecting theory and practice in pharmacy educational intervention research. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching & Learning. 2019;11:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfberg, P. J. (1993, March 25–28). A case illustration of the impact of peer play on symbolic activity in autism. [Paper presentation]. Annual meeting of the society for research in child development, New Orleans, LA, United States.

- Wolfberg, P. J. (1994). Case illustrations of emerging social relations and symbolic activity in children with autism through supported peer play (Publication No. 9505068) [Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, with San Francisco State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Wolfberg PJ. Play & imagination in children with autism. 2. Teachers College Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K., Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., Brock, M. E., Plavnick, J. B., Fleury, V. P, & Schultz, T. R. (2014). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham, Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group [DOI] [PubMed]

- Young RL, Rodi ML. Redefining autism spectrum disorder using DSM-5: The implications of the proposed DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2014;44:758–765. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1927-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]