Abstract

Sociological researchers have made immense strides in understanding systemic racism, privilege, and bias against Black people. Relational frame theory provides a contemporary account of human language and cognition that intersects within complex external contingency systems that may provide a provisionally adequate model of racial bias and racism. We propose a reticulated model that includes nested relational frames and external contingency systems that operate at the level of the individual (implicit), communities (white privilege), and system policies (systemic racism). This approach is organized from within the framework of critical race theory as an area of sociological scholarship that captures racial disadvantages at multiple levels of organization. We extend this model by describing avenues for future research to inform anti-racism strategies to dismantle this complex and pervasive sociobehavioral phenomenon. At all levels, police violence against the Black community is provided as a case example of negative social impact of racism in our society.

Keywords: Critical race theory, Relational frame theory, Racism, Anti-racism

Critical race theory (CRT) is a body of scholarship and movement that discusses the intersection of race, power, and institutional racism on the experiences of Black people (Bell, 1980; Delgado & Stefancic, 2001; Ladson-Billings, 1998). CRT emerged out of critical legal studies as a way to include discussion of racism with the critiques of oppressive structures in society (Ladson-Billings, 1998). Delgado and Stefancic (2001) note that CRT “questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law” (p. 3). Though CRT began as a movement in law and legal studies, CRT’s scholarship has become interdisciplinary stretching from education to sociology and has been used to critique structural inequities in school discipline practices and social status.

CRT rests on five central tenets: (1) racism is “ordinary, not aberrational” (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001 p. 7); (2) interest convergence (or material determinism) denotes white1 people as the primary beneficiaries of racist structures and have little incentive to eradicate it; (3) race is a social construction; (4) race is intersectional and anti-essential with various identities influencing their overall experiences; and (5) all voices are unique and have a story to tell (i.e., counter-storytelling). Critical race theorists note that racism is embedded in the very fabric of American society, informing social institutions and structures and how Black people navigate their daily lives (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001; Ladson-Billings, 1998). Further, notions of interest convergence shed light on how civil rights laws changed only when the interests of white people “converge” with the interests of Black people (Bell, 1980; Delgado & Stefancic, 2001). In an oft-cited discussion surrounding interest convergence, Derrick Bell, a notable critical race theorist, argued that Brown v. Board of Education served the interests of both Black and white citizens, providing Black citizens with the “opportunity” to receive a decent education, while assisting in economic and political advances worldwide. Bell states:

I contend that the decision in Brown to break with the Court’s long-held position on these issues cannot be understood without some consideration of the decision’s value to whites, not simply those concerned about the immorality of racial inequality, but also those whites in policymaking positions able to see the economic and political advances at home and abroad that would follow abandonment of segregation. (Bell, 1980, p. 524)

CRT further discuss the social construction of race, noting that race is the product of “social thought and relations” (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001, p. 9). Though the social construction of race has been noted and scientific/genetic realities debunked, American society continuously attaches “pseudo-permanent characteristics” to racial categories (Delgado & Stefancic, 2001, p. 9). Critical race theorists note that those with common heritage and ancestry will have similarities in areas such as hair, skin color, and physique; however, these similarities only account for small between group differences, and does not account for individual or within group differences. Further, critical race theorists have discussed how popular images and stereotypes have changed over time and is based in the current economic, social, and political climate. This challenges essentialist views of race, noting the role of intersectionality in one’s experience. Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), intersectionality describes how various identities such as race, class, and gender intersect to inform one’s experience. Though Black men and women may share the common identity of race, their experiences are not monolithic and are informed by the intersection of multiple sociocultural identities. Finally, critical race theory notes the importance of the experiential knowledge of Black communities. Majoritarian narratives reflect stories of race, gender, and class privilege. Solórzano and Yosso (2002) note that “a majoritarian story is one that privileges whites, men, the middle and/or upper class, and heterosexuals by naming these social locations as natural or normative points of reference” (p. 28). These stories often leave out or distort the experiences of Black communities. Therefore, Black communities utilize counter-storytelling as a means to dismantle the oppressiveness of majoritarian narratives and allow these communities to discuss their own narratives and experiences. CRT points to an immense sociocultural challenge that is harmful to the Black community, resulting in discrimination at multiple levels, including brutality and murder at the hands of police. Behavior analysts have a role to play in understanding how such discrimination emerges in order to develop systems to begin to dismantle the contingencies that maintain the suffering of people—in this case, Black people.

In synthesizing CRT, relational frame theory, and research on metacontingencies as a model of group selection, we may arrive at a nested model of racism against the Black community. The purpose in developing such a model is twofold: (1) the model allows for units that can be isolated within basic and translational research and (2) the provisional model, as it exists at any moment in time, may inform intervention research (i.e., anti-racism research). This approach is analogous to that described by Belisle and Dixon (2020) when discussing the complex interplay of neurological and contextual factors that may lead to addictive behavior in children. Whereas their model of addictive behavior necessitated borrowing from lower level neurological discoveries, a model of racism against the Black community likely necessitates borrowing from higher level sociological theories such as CRT. A potential reticulating nested model is shown in Figure 1, that includes the layers of implicit bias, white privilege, and systemic racism. Implicit bias research has garnered considerable attention both within behavior analytic journals (e.g., Barnes-Holmes et al., 2010) and more broadly within the field of psychology and sociology (e.g., Newheiser & Olson, 2012; Payne et al., 2019). This describes biased associations or behavior towards people based on race when other stimulus events are held constant. Within existing behavioral models, the outer layers of white privilege and systemic racism are less often incorporated; however, we contend that a model excluding these layers is inadequate in addressing this complex social challenge. White privilege describes the differential probability of obtaining reinforcement or punishment for similar or identical behaviors based solely on one’s race, in which the outcomes favor white people. Systemic racism describes the development of laws or policies, either explicit or derived, that differentially confer advantage or power based on one’s race. Behavior scientists (B, in the figure) may be likely to take a bottom-up inductive approach, starting at the level of the behavior of the individual and working upward to understand the behavior of groups and systems (Ivancic & Belisle, 2019; Dixon et al., 2018). Sociological scientists (S, in the figure) may be likely to take a top–down deductive approach, starting at the level of systems and policies, and evaluating how systems and policies affect individuals. In this model, we propose a reticulating inductive approach (R, in the figure), that relies on the on-going interaction of events at all levels. Throughout each section below, we define work conducted outside of behavior analysis followed by a description of behavioral events within the nested model. Finally, we conclude this article by discussing avenues for future research related to anti-racism intervention at multiple levels.

Fig. 1.

Nested Model of Racism Organized from within the Framework of Critical Race Theory. Note. (S) represents a traditional sociological top–down model of theory development; (B) represents a traditional bottom–up model of theory development; (R) represents a reticulated approach to theory development that accounts for the interaction of all levels in the nested model

Systemic Racism and the Criminalization of Black Bodies

Critical race theorists have detailed the influence of the history of systemic racism on the lives and experiences of Black people within the United States today. Faegin (2006) notes that “beginning in the seventeenth century, the Europeans and European Americans who controlled the development of the country that later became the United States positioned the oppression of Africans and African Americans at the center of the new society” (p. 2). During this time, Black people were relegated as noncitizens and forced into slavery to build and maintain the economic prosperity of the country. During this time, the creation of racial hierarchies and inequities prevailed, and fueled the development of racism and racist beliefs and ideologies surrounding blackness and Black people. Further, slave patrols emerged as some of the first publicly funded police forces, particularly in the South and were used to control and prevent slaves from revolting and running away to freedom (Durr, 2015). Smiley and Fakunle (2016) note that early racist images of Black people as docile and submissive plagued societal images, with books such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the popularization of minstrel shows and blackface dominating the culture. Following the abolishment of slavery, the reconstruction era ushered in new possibilities for Black people, as they began to find spaces in public office, create successful Black communities such as Black Wall Street in Tulsa, and explore higher education possibilities with the institution of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). These authors also note that

this growth in power challenged White supremacy and created White fear of Black mobility. Particularly, wealthy Whites were fearful of political power newly freed Black people could acquire via voting, whereas poor Whites saw Blacks as competition in the labor force. (Smiley & Fakunle, 2016, p. 5)

When Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 (Golub, 2005) ushered in the Jim Crow era, images of Black people as superhuman, brutes, and violent beings swept across the United States to further push the narrative of Black people as dangerous and deserving of their second-class, marginalized status. Though slave patrols were disbanded following the Civil War, police departments that enforced Black codes and Jim Crow laws were created (Reichel, 2008). Violent lynchings of Black people, men in particular, were prominent as Black bodies were criminalized and viewed as a threat. Black men were often viewed as a threat to white women and were often accused of assaulting, threatening, and raping them. This resulted in violent lynch mobs, who were often aided by the police, and public lynchings emerging as an informal enforcer of criminal justice (Bell, 2017). Further, images of Black men as savages in film such as Birth of a Nation and other racist propaganda fueled the ideology of Black bodies and inherently violent and continually informed laws, policies, and policing practices.

Stereotyping, Bias, and Police Brutality: The Consistent Policing of Black Bodies

Though slavery and Jim Crow era laws and codes have long been disbanded, the racial hierarchies and ideologies surrounding Black bodies remain and continually inform the experiences of Black Americans in the United States. Specifically related to policing, predominately Black areas continue to be heavily and disproportionally policed when compared to white suburban and affluent areas (Alexander, 2011). Further, Black people are more likely to be criminalized for petty criminal offences than their white counterparts. In addition, Black people are more likely to be sentenced for these crimes and receive longer sentencing than their white counterparts.

Though the physical, overt representations of racial inequities have seemingly been erased, systemic and subtle inequities and biases remain. Images of Black people as violent, threatening, and superhuman continue to permeate media images and inform implicit associations. With respect to policing, racial biases have been shown to influence police behavior and racial profiling. The war on drugs, extensive stop-and-frisk policies, and the use of excessive force by police officers on Black citizens all illuminate the role of stereotyping, implicit biases, racist images, and racial profiling on the over policing of Black bodies in the United States. For example, there is overwhelming evidence that New York’s stop-and-frisk policy disproportionally targeted communities of color, particularly Black men. According to the New York Police Department’s annual reports via the New York Civil Liberties Union, in 2019, 13,459 stops were reported with approximately 59% of those stops being Black people. Further, the Pew Research center notes that Black people are five times more likely to report being unfairly stopped by police. In addition to stop and frisk policies, there is overwhelming evidence of racial disparities in police brutality and killing. According to Mapping Police Violence, Black people are 3 times as likely to be killed by police than white people and are 1.3 times as likely to be unarmed compared to white people. Further, police are less likely to be held accountable through charges or conviction with 98.3% of killings by police from 2013 to 2020 resulting in no chargers or convictions.

These statistics demonstrate the presence of racial disparities in police–civilian interactions but does not illuminate the underlying biases that affect the disparities in these interactions. In 2014, Michael Brown, Jr., an 18-year-old Black man was fatally shot by a 27-year-old white Ferguson police officer named Darren Wilson. In his recollection of the event, Wilson noted several instances of being “afraid” of Michael Brown. According to a Time article (Sanburn, 2014), Wilson described Brown as being “intimidating” and “overpowering.” In the article, Wilson is quoted in saying “when I grabbed him, the only way I can describe it is I felt like a five-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan” (Sanburn, 2014). Wilson is also quoted in saying “he looked up at me and had the most intense aggressive face. The only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked” (Sanburn, 2014). Descriptions such as these reflect the biases built from slavery and Jim Crow that have been repackaged to inform the images and associations of Black people to non-Black individuals. Biases such as implicit associations and superhumanization continually dehumanizes Black people and creates associations of blackness as violent or having superhuman qualities. Lawson (2015) notes that “the distortion of the Black male body as a superhuman vessel is a form of dehumanization that may encourage police to use excessive force when dealing with Black suspects” (p. 357). In the description above, Wilson’s description of Brown as “aggressive” “demon” and “angry” in addition to him being “Hulk Hogan” compared to Wilson being a “5-year-old” demonstrates the work of implicit superhumanization biases in the use of excessive force by police.

Implicit Bias and Derived Relational Responding

Definition and Prior Research

Implicit bias is a multidimensional, multisystem phenomenon that involves unconscious beliefs and attitudes about various social groups. The term “implicit bias” emerged out of the broader theoretical framework of implicit social cognition, which refers to the influence of past experiences on current performance—without the recollection of those experiences (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). In other words, implicit cognition refers to the “automatic/implicit/unconscious processes underlying judgments and social behavior” (Payne & Gawronski, 2010, p. 1). A plethora of early research on implicit social cognition noted the role of automaticity and unconsciousness in the development and maintenance of these cognitive states. However, as research in this area continued, social scientists challenged these very notions. Blair (2002), in a review on the malleability of implicit social cognition, notes that automatic stereotypes and prejudices can be influenced by “perceivers motives, goals, and aspects of the situation” (p. 243). Evidence from approximately 50 research studies illuminate that

. . . automatic stereotypes and prejudice can be moderated by a wide variety of events, including, (a) perceivers’ motivation to maintain a positive self-image or have positive relationships with others, (b) perceivers’ strategic efforts to reduce stereotypes or promote counterstereotypes, (c) perceivers’ focus of attention, and (d) contextual cues.” (Blair, 2002, p. 255)

In early research related to implicit cognition, Jacoby and colleagues discussed the role of implicit and unconscious memories on deliberate judgment (see Jacoby & Witherspoon, 1982; Jacoby & Kelly, 1992). The pioneering implicit memories research prompted additional investigation into other implicit measures such as implicit attitudes and implicit stereotyping—both of which are relevant to bias and discrimination (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995; Greenwald & Krieger, 2006).

Attitudes can be defined as “favorable or unfavorable dispositions toward social objects, such as people, places, and policies (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995, p. 7). Similar to implicit memories, implicit attitudes involve the role of “introspectively unidentified (or inaccurately identified) traces of past experience that mediate favorable or unfavorable feeling, thought, or action toward social objects” (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995, p. 8). Key to this definition of implicit attitudes is the role of past experiences that are largely forgotten. Previous research has noted the role of evaluative priming, emotional responses to stimuli, and association in the development of implicit attitudes (Greenwald & Krieger, 2006). These early studies note the role of automaticity in the activation of one’s attitude toward social objects. One of the most widely used and studied evaluations of implicit attitudes is the implicit association test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 1998; Greenwald & Krieger, 2006). Similar to cognitive priming procedure, the IAT seeks to measure implicit attitudes through a series of sorting pairs of word/phrases/concepts (Greenwald et al., 1998). The premise behind the IAT is that response time to concepts that are highly associated for the individual will be faster than concepts that are not highly associated. One of the most popular and widely used IAT is the race-IAT, which evaluates racial implicit biases through pairings of white–Black faces and positive–negative words (Greenwald & Krieger, 2006). Research has extensively shown that in the United States, white Americans are often quicker to respond to white-positive associations than Black-positive associations demonstrating implicit preferences for white people relative to Black people (for review see, Greenwald & Krieger, 2006; Nosek et al., 2002).

Following implicit attitudes, implicit stereotypes are defined as “the introspectively unidentified (or inaccurately identified) traces of past experience that mediate attributions of qualities to members of a social category” (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995, p. 15). The term “stereotype” refers to “mental association between a social group or category or trait” (Greenwald & Krieger, 2006, p. 949). Research involving implicit stereotyping has suggested that stereotypes are expressed implicitly in one’s behavior and go against what one’s expressed beliefs or principles (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995; Greenwald & Krieger, 2006). Building from the research on implicit attitudes and stereotypes, Greenwald and Krieger (2006) define implicit biases as “discriminatory biases based on implicit attitudes or implicit stereotypes” (p. 951). Implicit biases go beyond attitudes and stereotypes to include the automatic and uncontrolled favorable or unfavorable evaluations of social groups. The role of implicit biases has consistently been noted and explored through in various interdisciplinary sources of scholarship. CRT has consistently noted the permanence of racism and anti-blackness in the fabric of American culture and social structures—so much so that it supports the formation of the “automatic and uncontrolled” attitudes, stereotypes, and biases. The role of implicit biases has been continuously studied across various social groups and has more recently been publicized in the news in response to racial bias and the killing of unarmed Black people. Conversations in this area have explored how implicit biases can affect who or what social groups are deemed criminal and what behaviors are considered to be dangerous. Research has consistently demonstrated that Black people are generally viewed as being more dangerous and criminal, leading to disparities in arrests and jail sentences as well as poorer mental health outcomes (Assari et al., 2018; Park, 2017). Further, research has noted that these biases can also manifest in the evaluation of children, because the behaviors of Black children are often viewed as “violent and negative,” which leads to disparities in school disciplinary practices, exclusionary punishments, and even matriculation into the juvenile justice system (i.e., school to prison pipeline; Nance, 2015).

An Initial Behavioral Model

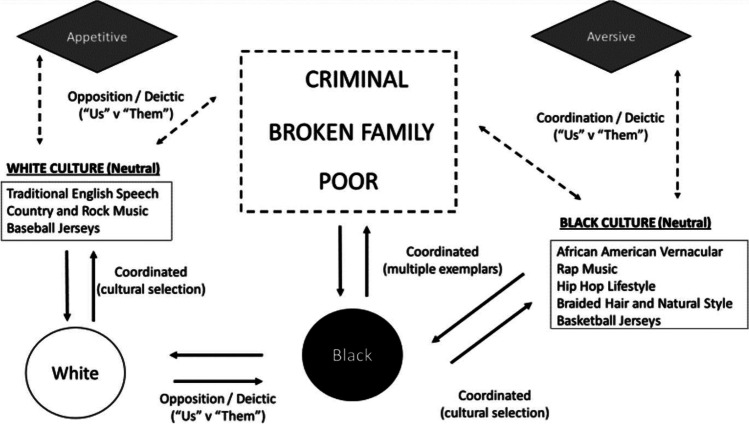

Behavioral models of implicit bias have often stemmed from a relational frame theory approach (Barnes-Holmes et al., 2010). Considerable research from this account has shown that implicit bias can be measured using the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) or IAT with consistent findings demonstrating strong, negative biases against members of the Black community (see above). The IRAP and IAT are tools that are designed to detect implicit biases as differences in response strength, or speed, when presented related or associated stimuli and requiring a matching response. Translational intervention studies have also shown that momentary implicit bias against minority populations, such as Middle Eastern people as terrorists (Dixon & Lemke, 2007; Dixon et al., 2009), can be reduced by targeting specific relational frames (see Dixon et al., 2018, for a discussion of this topic and potential implications). This model is shown in figures 1 and 2, which emphasize the transfer and transformation of aversive and appetitive functions through relational networks. Aversive functions can elicit or evoke avoidance or aggressive behavior whereas appetitive functions can elicit or evoke approach or cooperative behavior. For example, for some people, the word “dog” carries appetitive functions, such that people are more likely to approach a location that “contains dogs.” For other people, the same word “dog” carries aversive functions, such that people are more likely to avoid a location that “contains dogs.” The word “dog” is arbitrarily related to the abstracted physical properties of dogs (e.g., four legs, barking sounds, long snout, wagging tail), and the functions carried by these abstracted physical properties are the result of a person’s history with dogs (e.g., playful dog results in appetitive function; dog bite results in aversive function). Implicit bias is less concerned with explicit racism, such as the belief that “white people are superior to Black people” as a directly reinforced frame of comparison. Although this explicit relation is undoubtedly present within our society, explicit racism against the Black community may have become less prevalent over time. Implicit biases, however, pervades and may result from derived relations as shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 2.

Model of Derived Implicit Bias against Members of the Black Community (i.e., derived comparative frames). Note. Solid arrows show explicitly taught relations; dashed arrows show relations that are most likely derived in most cases (although, not all cases, because they may occur in explicit racist contexts); coordinated race contingent relations may not be taught explicitly, but emerge from multiple exemplar stimulus pairing

In the figure, a common comparison frame is presented that is likely explicitly taught within most communities. A “lawyer” is better than a “criminal” and a “criminal” is worse than a “lawyer.” For example, if an adult asks a child, “what do you want to be when you grow up?” and the child replies “lawyer,” this response is likely to be reinforced with verbal praise and attention. If instead the child replies “criminal,” this response is more likely to be reprimanded or punished. Therefore, this relation is likely directly trained through reinforcement, supporting a differential hierarchy of virtue professions. A similar pattern occurs for “nuclear families” are better than “broken families” and it is better to be “rich” than “poor.” In general, if members of any community were given the option to be a rich lawyer from a nuclear family or a poor criminal from a broken family, we may assume that most members of the community would select the first option. Therefore, “lawyer,” “nuclear family,” and “rich” all carry appetitive functions, whereas “criminal,” “broken family,” and “poor” all carry aversive functions, and these functions are generalizable within the larger society.

Unfortunately, due to differential exposure through media and news outlets among other sources, white people are more likely to be paired with appetitive social categories and Black people are more likely to be paired with aversive social categories (Adams-Bass et al., 2014). Although it may be common for these relations to be stated explicitly (e.g., “Black people are all criminals”), these relations likely develop through multiple exemplar exposure and stimulus pairing, establishing the coordinated relations shown in the figure. Whereas the color of a person’s skin may serve as a neutral stimulus within a race-neutral society, the appetitive and aversive functions can transfer to the visual stimulus of a person’s skin based on these coordinated relations. Through derived relational responding, we may also anticipate the emergence of the derived “white” is better than “Black” and “Black” is worse than “white.” It is likely these derived relations, through the transformation of stimulus function, result in implicit biases observed in tests such as the IRAP and the IAT that are designed to detect biases that are not explicit (i.e., derived). “White” and “Black” also exist in a frame of opposition, therefore, additional derived relations such as “white” is the opposite of “criminal” and “Black” is the opposite of “lawyer” may also emerge as a function of this shared sociocultural conditioning.

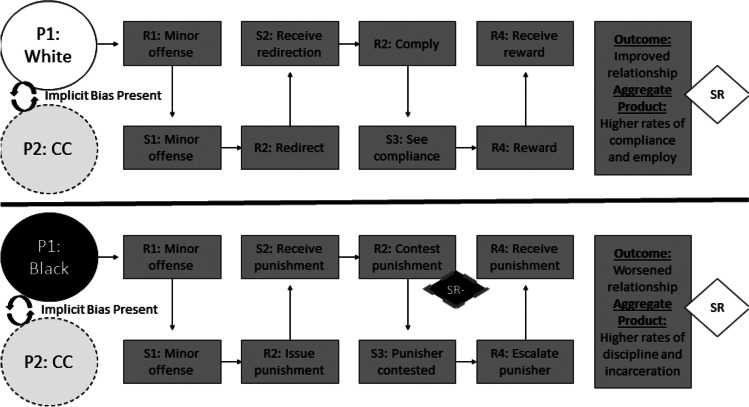

Figure 3 extends this basic model by detailing potentially even greater complexity that may exist within relational frames related to one’s race. Cultural behaviors and choices can emerge along racial or ethnic lines (Fong et al., 2017), corresponding to a multitude of situational and locational historic factors shared by groups of people that are physically similar. Cultural behaviors in a race-neutral society, like the color of one’s skin, exist as neutral stimuli (i.e., they do not carry a function intrinsically). For example, the music that a person listens to, the hairstyle a person selects, the clothing a person wears, and the vernacular a person speaks are unlikely to differentially and directly help or harm members of the community, which would establish a direct appetitive or aversive function. However, we do not live in a race neutral society. In the figure, common associations with Black culture are presented as within a frame of coordination with Black people. This coordinated frame too likely emerges through multiple exemplars and is the result of cultural selection, and these frames are justified. That is, Black people are more likely to identify with Black culture. We may also assume a frame of coordination between white culture (e.g., traditional English vernacular, country and rock music, baseball fanaticism) and white people. This is, of course, a statement of probability, as not all members of the Black or white community adopt these cultural norms. However, “Black” is not race-neutral and carries the aversive functions of the existing coordinated relations. Again, through derived relational responding, we may predict a derived relation between aspects of Black culture and the aversive social categories.

Fig. 3.

Expanded Model of Derived Implicit Bias against Members of the Black Community. Note. Through cultural selection, cultural norms are differentially present in white and Black communities as identifiable parts of each culture. Black also exists in an opposition frame to white, negating the transfer of stimulus function with deictic frames of “Us” versus “Them “within group categorization. The derived relation transfers the aversive function of the previously entailed aversive class to neutral cultural events associated with the Black community

In addition, we may expect aspects of white culture to be viewed more positively as a result of transformations of stimulus function due to opposition relations between “white” and “Black.” Traditional English vernacular, country music, and watching baseball are neutral in a race-neutral society; however, these choices are likely to exist in a derived opposition relation with “criminal,” “broken family,” and “poor,” and exist in a derived coordinated relation with “lawyer,” “nuclear family,” and “rich.” Potentially even greater complexity is established given deictic relations, or perspective taking, that establishes “us” versus “them” frames through social categorization based on race (Fong et al., 2016), where people are viewed as existing “in-group” or “out-group” based on shared physical features. Whereas social categorization could be established based solely on profession, family make-up, or wealth, independent of one’s skin color, this is unlikely to occur. Unfortunately, implicit bias can have very real negative implications for members of the Black community beyond differentiated responding on tests of implicit bias. In the section that follows, we discuss some of these potential implications in the context of interlocking behavioral contingencies and white privilege. In particular, implicit bias can result in differential access to reinforcement and punishment due solely to one’s skin color that can have significant implications for behavior within complex social systems.

White Privilege and Interlocking Behavior Contingencies

Definition and Prior Research

As mentioned throughout this article, CRT notes that racism is a permanent fixture within American society with white people being the primary beneficiaries of its social structures (Bonilla-Silva, 2015; Crenshaw et al., 1995). Disparities in policing, arrests, housing, education, and health, and policies and laws that target Black populations such as “zero tolerance” policies in schools and mass incarceration all serve as evidence to this notion. The term “white privilege” has been dubbed to discuss the benefits that white people receive based on race that nonwhite racial groups may not receive based on their race. Delgado and Stefancic (2001) note that “‘White privilege’ refers to the myriad of social advantages, benefits, and courtesies that come with being a member of the dominant race” (p. 89). In other words, white privilege refers to unearned benefits and advantages that are associated with whiteness. Peggy McIntosh (1988) defines white privilege as:

an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was "meant" to remain oblivious. White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, assurances, tools, maps, guides, codebooks, passports, visas, clothes, compass, emergency gear, and blank checks. (p. 30)

McIntosh goes further in noting 46 privileges that white people may have solely based on their race. These privileges range from seeing whiteness represented in multiple forms (i.e., books, television) to not being questioned about financial stability.

In the United States, whiteness-as-norm has been engrained in the country’s way of life—from policies to media. Streaming from slavery and Jim Crow era laws and regulations, Black people were deemed abnormal and aberrational, whereas whiteness was constructed as the norm. Black bodies were deemed savage, brutish, and dangerous, whereas white bodies were considered worthy. Although some people may believe that those slavery and Jim Crow era ideologies are in the past and the United States has made strides in racial progress, CRT scholars note that racism and the ideologies have not changed, they have just been masked. Alexander (2011) notes “we have not ended racial caste in America, we have merely redesigned it” (p. 2). Payne et al. (2019) showed that implicit bias against Black people and the prevalence of slavery in 1860 are positively related, supporting the continued negative impact from this period. Anti-blackness, negative stereotyping, and biases continue to inform the United States social structures as Black people remain overrepresented in the prison system, yet only make up approximately 13% of the U.S. population. Further, Black people are underrepresented in leadership positions and in positions of power.

An Initial Behavioral Model

Implicit bias alone, if there was no transformation of stimulus function, may not lead to consistent disadvantages for the Black community and consistent advantages for the white community. Unfortunately, several studies described above suggest that advantages, or reinforcers, are more likely to be presented to members of the white community and punishers are more likely to be presented to members of the Black community, based solely on the color of their skin (i.e., when other factors are held constant). Figure 4 details this relationship from the locus of a contingency controller. The contingency controller represents the authority figure within a context that has the opportunity to reinforce, ignore, or punish the behavior of another person. In a school setting, the contingency controller is the schoolteacher or principal. In the broader society, police officers exist as contingency controllers, because they are given authority by the government to deliver punishers such as fines or detainment contingent upon observing illegal behaviors occurring within the society. In a race-neutral system, the actions of the contingency controller to administer reinforcement or punishment would exist solely as a function of the behavior observed. If the contingency controller sought to decrease a behavior, they may administer a punisher, such as a ticket or fine. If the contingency controller sought to increase a behavior, they may administer a reinforcer, such as a bonus or incentive. However, through relational framing, implicit biases are present that may affect the probability that the contingency controller uses reinforcement or punishment to alter the behavior of the other. In one example, Pierson et al. (2020) showed that Black people are more likely to be pulled over than white people in the same neighborhoods (i.e., holding socioeconomic status and overall area crime rates constant). However, this difference appears to diminish at night when police are less able to see the color of the person operating the vehicle, isolating skin color as the contextual variable controlling the decision of administer a punisher (i.e., pulling a person over). Furthermore, whereas Black motorists are 30% more likely to be pulled over, Black motorists also comprise approximately 76% of arrests following a routine traffic stop, despite approximately identical “hit rates” associated with both groups based on an internal study of police oversight in Austen, Texas. Finally, even when controlling for a greater probability of an arrest following a traffic stop, Edwards et al. (2019) showed that between 2013 and 2018 showed Black men were 2.5 times as likely to be killed in a police encounter as white men. Black and Latina women are also 1.4 times as likely to be killed in a police encounter as white women.

Fig. 4.

Consequential Functions that Support and Maintain White Privilege within the Nested Model. Note. The traditional model ignores the relational contextual variables of race that affect the probability of reinforcing, ignoring, or punishing the same observed behavior. Outcomes represent behavior change consistent with reinforcement and punishment behavior-change strategies

Race as a relational contextual variable can have a significant impact on differential outcomes and aggregate products of white and Black communities through interlocking behavior contingencies (IBC; see dos Reis Soares, 2018, for an analysis of IBCs and cultural behavior). An IBC exists when two or more people engage in topographically different behavior that leads to a shared outcome, where the outcome reinforces the shared interlocking behavior. In Figure 5, we show a potential IBC that exists between a contingency controller (CC, in the figure) and a white (top panel) or Black (bottom panel) person. The two panels show how a differentiated outcome and aggregate products may be likely depending on the color of the person’s skin, even when the same initial behavior (Person) and stimulus (CC) is observed. First, in concordance with the reticulating model, we assume that both the person (white or Black) and the contingency controller (most likely white) enter the interlocking contingency with implicit biases against Black people (i.e., “Black” carries existing aversive functions). In both panels, the person engages in a minor offense such as speeding while driving (R1). The CC (police officer) observes the minor offense (i.e., sees a person speeding). As noted above, if the person is white, the police officer is more likely to either ignore the offense (i.e., do nothing) or respond with a redirect (e.g., a warning); on the other hand, if the person is Black, the police officer is more likely to respond by issuing a punisher, such as a ticket or choosing to search the vehicle (i.e., temporary detainment). Given the redirection in the top panel, one may predict that the person complies with the redirection and may apologize for the offense, resulting in a reward from the police officer (e.g., “have a nice day” or “be safe out there”), that results in an improvement in the relationship between the person and the police officer, and an aggregate outcome of higher rates of general compliance with authorities and employability (i.e., obtaining employment with a criminal record confers a greater response cost). Given the punisher in the bottom panel, the person would be justified in contesting the punishment (e.g., “that’s not fair!” or “no, you cannot search my vehicle, am I being detained?”), given the potential that the punisher was not race-neutral. The (SR-) in the figure shows the potential for negative reinforcement for both P2 and the CC if the punisher is withdrawn by the CC, that may maintain the counter control exerted by the person being punished. This negative reinforcement is probabilistic, however, because the police officer may choose to escalate the punisher, such as by issuing an arrest for failure to comply earlier in the interlocking contingency. Regardless, the anticipated outcome may be a worsened relationship between Black people and police as contingency controllers, as well as higher rates of discipline, incarceration, and lower employability.

Fig. 5.

Interlocking Behavior Contingency (IBC) including Person 1 Who is White (top) or Black (bottom) and Person 2 as the Contingency Controller (CC). Note. Dashed outline recognizes an increased probability that the CC is white; R represents a responses and S represents a stimulus; implicit biases present for person 1 and person 2 predict different responses to the same minor offenses with different outcomes and aggregate products of the contingency; (SR-) in bottom panel represents probabilistic negative reinforcement for P1 (Black) contesting unfair/differentiated punishment; SR represents reinforcement, both positive and negative, available to the CC contingent upon the aggregate product of the interaction

An IBC must be maintained by reinforcement at the conclusion of the interlocking behavior resultant from the outcomes of the shared interaction. Because the interlocking contingency contains a contingency controller, reinforcement conferred to the CC within the interlocking contingency is sufficient to maintain the interaction. In the top panel, the CC may experience positive reinforcement because of the successful social interaction that lead to an improved relationship between P2 and the CC. The CC may also experience negative reinforcement by avoiding the social and legal ramification of detaining or arresting a member of the privileged culture, such as avoiding threats of the involvement of lawyers after detaining or arresting an affluent white suburbanite. Also consider an increased probability that P2 in the top panel has familial connection to another member of the police force that could serve to reinforce ignoring or redirecting the offense or punish the CC’s behavior if viewed as excessive. On the other hand, in the bottom panel, the CC may experience positive reinforcement following a ticket or arrest of P2 by members of the police force for “being tough on crime” or “protecting and serving the community.” Because of systemic differences (discussed in the next section) the CC is less likely to contact punishment through social or legal ramifications if P2 is Black, because the person is less likely able to afford a lawyer to contest detainment or arrest, and preexisting social relationships with police officers is significantly less likely. Therefore, reticulation between IBCs that result in white privilege and systemic racism (discussed in the next section) may be immediately apparent.

Equally problematic is the reticulation that exists between IBCs that lead to white privilege and implicit biases that participate in the formation of IBCs. For example, one aggregate outcome of differential IBCs based on race is that Black people are more likely to be convicted of crimes, even when controlling for relative rates of committing crimes (Sommers & Ellsworth, 2001; Kang et al., 2011; Cantone et al., 2019). The coordinated relationship between “criminal” and “Black” likely emerges through multiple exemplars of seeing Black people being arrested—an outcome that is more likely due to the IBCs that exist within an inherently racist system. More Black people are likely to be labelled as “criminals,” contributing to the coordinated relation. Further, obtaining employment is more difficult given record of an offense, even if the offense is minor. If, however, a person is never arrested and charged for the offense, the offense is not recorded with no negative effects on employability. Because Black people are more likely to be arrested and charged for identical minor offenses, the aggregate product is lower employability, resulting in lower Black representation in high paying professions (e.g., lawyer, consistent with the prior example). The dynamics of a capitalist system therefore present only a choice between jobs that pay below living wage or engaging in criminal activity such as theft or selling illegal material, resulting in higher rates of criminal behavior within Black communities, again further strengthening the coordinated relationship between “criminal” and “Black.” The above is only one example of an IBC, where members of the Black community experience a sum of several IBCs that biased against the Black community, and it is the sum of these interactions that contribute to systemic disadvantages the even further racial disadvantage. Below, we detail avenues for future research that are forthcoming at the level of white privilege.

Systemic Racism and Relational Metacontingencies

Definition and Prior Research

Critical race theorists noted that racism is not only an individual phenomenon, it is also a permanent fixture in American society, affecting the very systems and institutions that govern society (Bonilla-Silva, 2015; Nunn, 2011). Systemic racism refers to the institutions, laws, policies, and systems of oppression that continue to influence how Black people navigate throughout daily lives. Laws and policies centering the needs and interests of white citizens have governed the landscape of American culture and governing bodies, whereas the needs and interests of Black people have been minimalized. Inequities in wealth, employment, housing, policing, incarceration, and health care all encompass the broad umbrella of systemic racism. Though Black people in the United States only comprise approximately 13% of the country’s population, they account for 34% of the country’s prison population. Further, according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), “African American children represent 32% of children who are arrested, 42% of children who are detained, and 52% of children whose cases are judicially waived to criminal court. African American children represent 14% of the population.” In addition, according to the NAACP, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Desilver et al. (2020), research has shown that a majority of Black people have reported been treated less than fairly by police officers with approximately 70% of Black people reporting unfair treatment, and approximately 65% reporting feeling targeting because of their race. An account of CRT from a behavioral perspective would be incomplete without analyzing how these desperate outcomes emerge from within a legal and social system that consistently harms members of the Black community.

An Initial Behavioral Model

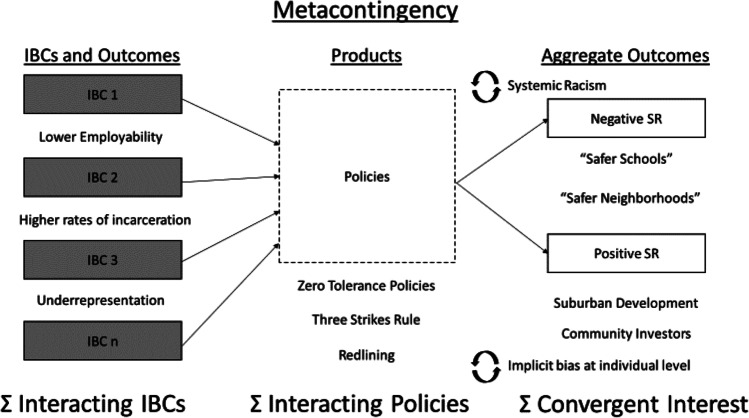

Metacontingencies describe the development of products through the summed interaction of multiple IBCs, where the product produces aggregate outcomes that reinforce the lower level IBCs. Like in the prior two models, metacontingencies are not likely race neutral. Although IBCs involve CCs who are Black or white and P2s who are Black or white, the most likely arrangement is a CC who is white, and the outcome of the IBC differs markedly depending on if P2 is Black (negative outcome) or white (positive or neutral outcome). Therefore, outcomes that reinforce the behavior of the CC, regardless of the outcome for P2, may be sufficient to maintain the IBC. Figure 6 shows how multiple IBCs may interact to produce systematic disadvantages for the Black community and systematic advantages for the white community, supporting white privilege at the lower level. We observe lower rates of employment and pay in the Black community (see above), higher rates of incarceration in the Black community (see above), underrepresentation in privileged positions such as in school boards and in political contexts in the Black community (see above), among other outcomes that may emerge from culturally biased IBCs. The sum of these multiple interactions is problematic on the surface, and due to intersectionality, may be worse when multiple sources of systemic disadvantage are present. For example, being female may serve as a disadvantage in many contexts, where the effects are even further exacerbated for Black females through intersectionality (Mirza, 2014). Members of the LGBTQ+ community also experience numerous forms of systemic discrimination, where the effects are again further exacerbated for Black members of the LGBTQ+ community (Moreau et al., 2019). For example, experiences of Black gay men captured by Bowleg (2013) describe additional challenges emerging from within the Black community through increased microaggressions and the need to act in accordance with masculine gender norms to appear heterosexual within the community. Therefore, although we are addressing systemic racism against the Black community, this same model may be viable when addressing other minority populations and the intersectionality of privilege at lower levels must be considered in the model.

Fig. 6.

Metacontingency System Contributing to and Maintaining Systemic Racism against the Black community. Note. Multiple IBCs lead to the production of aggregate products, such as policies, regulations, or laws, to control IBC outcomes; dashed outline recognizes increased probability that policy creators are often members of the white community; aggregate outcomes of the policies provide negative and positive reinforcement functions for the policy makers and constituents. Because policy makers and majority constituents are white, the policies are most likely to positively affect the white community and may also positively affect the Black community if convergent interests are present. Many policies are neutral or harm the Black community

Interacting IBCs can lead to the development of laws or policies intended to address the negative outcomes at lower levels. For example, zero tolerance policies were developed to address challenging behavior, drug use, and violence occurring in schools, where these policies are exceedingly pervasive within schools housed in Black communities (Berlowitz et al., 2017). Zero tolerance policies address challenging behavior through discipline, suspension, or expulsion, and likely contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline where these policies are adopted. Three-strikes laws in the United States were adopted as a “tough on crime” initiative wherein persistent offenders were sentenced to life in prison for committing potentially minor offenses. Three strikes laws affected the Black community more significantly than other communities (see Green et al., 2006) and undoubtedly participates with lower-level IBCs in that members of the Black community are more likely to be stopped, searched, and arrested for the same minor offenses compared to members of the white community (Gaston, 2019; Aseltine, 2019). Redlining is another policy that was developed to ensure representation of community members and to ensure taxation benefited the surrounding community. Unfortunately, regional lines occur along racial lines (Krieger et al., 2020). Over and over, emergent policies are developed that are disadvantageous to the Black community, but it is important to note that due to underrepresentation of Black people within decision-making positions (e.g., in government), policies are predominantly developed by members of the white community. Therefore, the aggregate outcomes are likely to maintain the policy when—and only when—the policies confer advantage to the white community. For example, zero tolerance policies, three strikes laws, and redlining may confer negative reinforcement for members of the white community by contributing to the perception of safer schools and safer communities. There is no doubt that communities are safer if fewer people are committing offenses, especially egregious offenses such as battery, sexual assault, or murder. Reticulation, however, is observed when implicit biases are present, such as relating “batterer, rapist, or murderer” selectively with members of the Black community. These relations are propagated historically through media, such as in the film Birth of a Nation, where the emergence of Black rights results in the sexual assault of suburban white women. Or, in presential discourse such Donald Trump’s assertion that the “housewives of America” must be protected by retaining discriminatory housing rules in white suburban communities (MSNBC, 2020). Policies may also confer advantages to white communities by promoting suburban development and community investment that can increase access to valued commodities and increases in property value, making available additional sources of reinforcement.

The sum of the interacting aggregate outcomes for the Black community is referred to as interest convergence. On occasion, policies are developed that confer advantage to the Black community, such as the desegregation of schools as a result of the ruling of Brown v. Board of Education. As discussed by Bell (1980), desegregation was touted as a unique victory for civil rights; however, desegregating schools also conferred several advantages to the white community. First, desegregation provided a foil to the communist policies that Americans were fighting during the civil rights movement. Second, desegregation opened up rural areas to development in sunbelt states that conferred immediate economic advantages to white rural communities (i.e., white landowners). As noted by Lopez (2003), interest convergence centralizes on the theory that “Whites will tolerate and advance the interests of people of color only when the promote the self-interests of whites” (p. 84). From a metacontingency model, this assumption is likely valid, because promoting self-interest confers reinforcement that promotes the development of policies in the first place. On the surface, interest convergence may appear as a solution (i.e., impetus to locate convergent interests); however, due to underrepresentation in a majority white culture, policies are also likely to be developed that confer little or no advantage to the Black community or directly harm the Black community, such as the policies described above. The result is an even greater differentiation of resources and privilege across both communities, and the proliferation of relational frames that lead to implicit bias against members of the Black community. Again, the implicit biases participate in the formation of IBCs that contribute to the development of these policies that participate within systemic discrimination.

Power dynamics may additionally contribute to maintaining systemic discrimination. According to Goltz (2003, as cited in Goltz, 2020), power describes the potential for influence that occurs when one individual or group controls access to reinforcement or punishment (i.e., exists as the contingency controller). Differences in power are evident at all three layers of the reticulating model described here. Implicit biases against Black people are evident within both the white and Black community; however, members of the white community are more likely to serve as contingency controllers, such as in the role of a teacher, principle, or police officer, establishing an immediate power differential. Even if the contingency controller is a member of the Black community, the same implicit biases that participate in the development of white privilege are still present. Exacerbating this power dynamic within IBCs are policies makers that are largely white, resulting in policies that confer even greater advantage, or power, to the white community. Goltz (2020) proposes that maintaining power can also serve as a reinforcer, above and beyond the immediate negative and positive reinforcers described above. For example, if a police officer does not escalate punishment in Figure 5, they risk losing credibility with other potential offenders and within the police force, signaling a reduction in power (i.e., control over contingencies). Therefore, although the police officer may contact negative reinforcement by choosing not to escalate a punisher when P2 contests the punishment, obtaining the negative reinforcers occurs concurrently with a loss of power. Likewise, although white policy makers could develop policies that exclusively benefit the Black community and potentially harm the white community, doing so would confer a loss of power within the white community, and in consequence a loss of power for the policy maker. “In-migration,” or the movement of members of “out-group” populations to “in-group” contexts, provides one example (Huang et al., 2017). Upward social movement of the Black community can be seen as “in-migration” within traditionally white social contexts (i.e., social contexts that maintain power within the current social structure). Because “in-migrations” put the social power of the white community at risk, attempts to dissuade upward movement of the Black community can occur, such as imposing systemic blocks on the community, or through racist remarks or aggression, including macro- and micro-aggressions described above. All of these interacting elements may combine to maintaining systemic racism against the Black community.

Immediate Avenues for Future Research

The model of racism we have described, though largely theoretical and certainly incomplete, provides clear avenues for basic and applied behavior analytic researchers to develop an understanding of racism from a behavioral perspective consistent with CRT as well as to develop anti-racist interventions for individuals and groups. Although scholarly work regarding racism and anti-racism is more established in other fields, we speculate that the nature of behavior analytic research methodology and applied technology targeting the prediction and influence of human behavior is critical to creating substantive change. As stated by Kendi (2019), “The only way to undo racism is to consistently identify and describe it—and then dismantle it” (p. 9).

As previously noted, behavioral research regarding implicit biases is robust, yet studies intended to directly understand and change race-related biases and suffering are needed. We will highlight two potential lines of research that may contribute to both robust models of implicit racial bias and effective interventions for the reduction of such biases. One area for research serves primarily to enhance models of racism by examining variables that may predict or influence biased responding. As we have discussed, the relationships among relational responding, biases, and environmental contingencies are important to approach a more complete model of racism. Biases may be more pronounced when couched within a system that is biased; therefore, investigations that analyze the relationship between “context” and individual implicit bias are needed. Within this area of contextual control of implicit bias, we suggest three opportunities for immediate exploration. First, researchers may compare observed implicit biases in the presence of stimuli common to racist events (such as crime-related stimuli) and neutral or arbitrary stimuli with no known history of racism. Second, investigations regarding the relationship between implicit biases and rule-governed or verbally mediated behavior may be useful in enhancing these behavioral models and developing or changing information encountered by individuals in the form of verbal stimuli. For example, investigators may explore the presence of rule statements in the form of statistics resultant from racist systems (for example, statistics regarding relative rates of arrest) on the implicit bias exhibited by individuals. Analyses of the effect of these verbal stimuli on biased responding, like contextual variables, can support the development of robust models of racism as well as elucidate avenues for exploring anti-racist interventions at the level of implicit bias. Third, as we have previously noted, the model presented in this article suggests a pivotal role of transformation of stimulus function in the development and strengthening of implicit biases as well as white privilege; therefore, empirical examinations of transformation are needed in controlled, analogue, and natural environments. Data from studies in this area could serve to increase the complexity of sociobehavioral models of racism as well as the analysis of related concepts such as “stereotype threat,” a term used to describe when “when members of a stigmatized group find themselves in a situation where negative stereotypes provide a possible framework for interpreting their behavior, the risk of being judged in light of those stereotypes can elicit a disruptive state that undermines performance and aspirations in that domain” (Spencer et al., 2016, p. 415).

A second area of potential research related to implicit racial biases serves to explore techniques and interventions that eliminate the racial biases that support racist systems. An anti-racist approach to studying implicit bias includes both the reduction of “negative” biases toward Black or Brown individuals and the reduction of “positive” biases toward white individuals, because both biases support the discrimination and privilege described throughout this article. Both empathy and awareness training have received some, but limited, empirical attention in the area of racial bias, but more studies are needed to establish the degree of efficacy demonstrated by these interventions. As described by Pederson et al. (2005), existing research suggests a significant inverse relationship between measures of prejudice and empathy as well as the reduction of racism resultant from increased empathy; however, literature describing effective technologies for increasing empathy is more limited. Behavior analysts have explored the development of empathy skills in other areas (e.g. Sivaraman, 2017; Schrandt et al., 2009), and may develop and evaluate interventions using existing behavioral technologies such as behavioral skills training, relational training of deictic relations, and acceptance and commitment training, among others, as an avenue for eliminating racial biases. Training to increase awareness and accurate report of one’s implicit biases and the discrepancies with one’s stated attitudes and beliefs additional warrants further investigation. Attentional interventions such as mindfulness may have utility in changing racial biases (e.g., Lueke & Gibson, 2015); research regarding mindfulness is increasing in behaviorally oriented academic journals (e.g. Kasson & Wilson, 2017; Singh et al., 2019) and behavior analysts may seek to explore the application of mindfulness in this area, such as evaluating the effect of a brief mindfulness exercise on police officer’s momentary implicit bias. Although investigations of specific interventions to eliminate racial implicit biases are needed in and of themselves, behavior analysts may also be able to contribute to the development of interventions designed to address the biases observed within institutions. Although “front-end” training regarding racism, anti-racism, biases, and other related topics are useful in the elimination of discrimination in groups, behaviorally oriented professionals can seek to develop interventions that correct such biases when they are observed in settings such as law enforcement agencies.

Behavior analysts may also contribute to the literature regarding white privilege by exploring various basic, translational, and applied research lines; to our knowledge, such research in behavioral academic journals is absent, and needed. Research in this area can be thought of in two categories: refining a model of white privilege and interventions that eliminate such privilege. A unique contribution of behavioral researchers in this area may be in the development of methods to measure white privilege for research and practical purposes; behavior analysts could develop direct and indirect assessment of behaviors that maintain privilege and outcomes of this privilege. Basic research demonstrations of proposed models of white privilege and individuals’ differential responding consistent with those models are needed. For example, given a history of bias training, is the “choice making” of the contingency controller predictable? Quantitative models such as the matching law and behavioral economics could predict the effects of reducing bias and changing systems on the behavior of the contingency controller, measuring white privilege as an outcome. Given a conceptually consistent, empirically valid model of privilege, researchers can explore methodologies that undermine racist systems. For example, researchers may explore the efficacy of using behavioral skills training to teach white people to utilize their privilege (e.g., opportunities, leadership roles, platform) to implement and amplify anti-racist actions, policies, or system changes (for a discussion of the importance of increasing anti-racist action and accountability among white individuals, see Boykin et al., 2020). Research in the field of management has indicated that organizations should utilize analyses of needs regarding workplace culture to create data-based anti-racist change initiatives (e.g. Roberson et al., 2003). Behavior analysts who specialize in organizational behavior management may develop and evaluate such organization-level assessment and intervention protocols, for example, using performance diagnostic checklists in law enforcement agencies like those used to address issues in business (e.g., Pampino et al., 2004), human services (e.g., Wilder et al., 2020), and workplace safety (e.g., Martinez-Onstott et al., 2016). These are just a small number of potential behavioral interventions that can be utilized to support the dismantling of white privilege at both individual and organizational level.

The level of systemic racism presents the greatest challenge in terms of behavior analytic research. Again, research in this area may be conceptualized in two components: basic models of the relational metacontingencies that produce racist systems and interventions or system changes that can eliminate racism at a cultural or societal level. As noted by Zilio (2019), both basic and applied research regarding metacontingencies is limited. Because of this, both general models of metacontingency and those specific to the issue of racism require empirical attention. In terms of applied, change-focused research to address systemic racism, behavior scientists may have the most impact in the context of interdisciplinary research with experts from other fields, such as sociology or political science. As noted by Gellar (1989) in his discussion of collaboration in order to address environmental issues, interdisciplinary networks of practitioners, academics, and leaders in corporate and governing institutions who share a common target behavior for change (in that case, pro-environment behavior, and in this case, anti-racist behavior), and dissemination of accessible empirical reports to policymakers and grassroots organizations are important elements to enact change at a cultural level. For example, in communities that enact policy changes related to policing, such as defunding police agencies and/or increasing funding for community services, behavior analysts may support other professionals by utilizing quasi-experimental small-group or single-case research designs to evaluate changes in community behavior, and analyzing functional relationships between policy change and behavior. Research methods consistent with applied behavior analysis (i.e., “the seven dimensions” described by Baer et al., 1968) may solve problems faced by researchers in other disciplines in terms of operationally defined target behaviors, high internal validity, and reproducibility of results, potentially accelerating the work already being done to address racism domestically and internationally.

Behavior analysts seeking to contribute to research regarding behavioral conceptualizations of racism and the application of behavioral technologies to aid in the reduction and elimination of implicit racial biases, white privilege, and systemic racism might find more immediate avenues for action in research with individuals and single agencies. However, given the reticulating nature of racism in our culture as posited by the authors of this article, equally important to empirical action is the development of interdisciplinary networks and more effective dissemination to expand the reach of behavior analysis in this critically important social issue.

Summary

Racial bias against the Black community is pervasive and occurs at multiple levels. Although explicit racism may be decreasing in prevalence, implicit bias, white privilege, and systemic racism remain pervasive. As described within CRT, race is a social abstraction with real implications for Black people. The present sociobehavioral model provides a complex and reticulating mechanism to explain the interaction of behavior processes at each level. In particular, we emphasized the on-going interaction between relational frames and metacontingencies that produce this bias in the United States. By isolating these mechanisms, research may begin to develop anti-racism strategies that are designed to reduce or eliminate racial beliefs and structures. Police brutality is one example, wherein biases not only result in direct harm or death for Black people, but also contribute to on-going systems-level disadvantages across all levels (e.g., zero tolerance policies, law-and-order initiatives). Intervention research cannot occur only within a single level because events within each level likely influence events at higher and lower levels. To contribute to solving this immensely complex social challenge, behavior analysts must engage in interdisciplinary research at all levels. We must also make contact with other disciplines to ensure our models are consistent with the considerable research that has already emerged to address racism in our shared society.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional human subjects committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards

Footnotes

This article centers on the discussion of the role of systemic racism and white supremacy through a critical race theory lens. Therefore, when discussing the experiences of the Black community and their experiences of racism, in particular police-civilian interactions and police brutality, Black will use upper-case letters and white will use lower-case letters. Davis (2019) notes, “the term ‘white’ has been used as a signifier of social domination” (p. 154). In doing so, we hope to center the experiences of the Black community and the destructive nature of racism and white supremacy.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams-Bass VN, Stevenson HC, Kotzin DS. Measuring the meaning of black media stereotypes and their relationship to the racial identity, black history knowledge, and racial socialization of African American youth. Journal of Black Studies. 2014;45:367–395. doi: 10.1177/0021934714530396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. (2011). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New Press.

- Aseltine, E. (2019). Perpetual suspects: A critical race theory of black and mixed-race experiences of policing. Journal of Critical Justice Education,623–625,. 10.1080/10511253.2019.1632365.

- Assari S, Miller RJ, Taylor RJ, Mouzon D, Keith V, Chatters LM. Discrimination fully mediates the effects of incarceration history on depressive symptoms and psychological distress among African American men. Journal of Racial & Ethnic Health Disparities. 2018;5:243–252. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0364-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:91. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Murphy A, Barnes-Holmes Y, Stewart I. The implicit relational assessment procedure: Exploring the impact of private versus public contexts and the response latency criterion on pro-white and anti-black stereotyping among white Irish individuals. The Psychological Record. 2010;60:57–79. doi: 10.1007/BF03395694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belisle J, Dixon MR. Behavior and substance addictions in children: A behavioral model and potential solutions. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2020;67:589–602. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2020.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DA., Jr Brown v. Board of Education and the interest-convergence dilemma. Harvard Law Review. 1980;93(3):518–533. doi: 10.2307/1340546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M. (2017). Criminalization of Blackness: Systemic racism and the reproduction of racial inequality in the US criminal justice system. In R. Thompson-Miller & K. Ducey (Eds.), Systemic racism (pp. 163–183). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Berlowitz MJ, Frye R, Jette KM. Bullying and zero-tolerance policies: The school to prison pipeline. Multicultural Learning & Teaching. 2017;12:7–25. doi: 10.1515/mlt-2014-0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair IV. The malleability of automatic stereotypes and prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:242–261. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0603_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. More than prejudice: Restatement, reflections, and new directions in critical race theory. Sociology of Race & Ethnicity. 2015;1:73–87. doi: 10.1177/2332649214557042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. “Once you’ve blended the cake, you can’t take the parts back to the main ingredients”: Black gay and bisexual men’s descriptions and experiences of intersectionality. Sex Roles. 2013;68:754–767. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0152-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boykin, C. M., Brown, N. D., Carter, J. T., Dukes, K., Green, D. J., Harrison, T., ... & Williams, A. D. (2020). Anti-racist actions and accountability: Not more empty promises. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal,39(7), 775–786. 10.1108/EDI-06-2020-0158

- Cantone JA, Martinez LN, Willis-Esqueda C, Miller T. Sounding guilty: How accent bias affects juror judgments of culpability. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice. 2019;17:228–253. doi: 10.1080/15377938.2019.1623963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;1989(1):139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K, Gotanda N, Peller G, Thomas K. Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. New Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Davis SM. When sistahs support sistahs: A process of supportive communication about racial microaggressions among Black women. Communication Monographs. 2019;86(2):133–157. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2018.1548769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado R, Stefancic J. An introduction to critical race theory. New York University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Desilver, D., Lipka, M., & Fahmy, D. (2020). 10 things we know about race and policing in the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/03/10-things-we-know-about-race-and-policing-in-the-u-s/

- Dixon MR, Belisle J, Rehfeldt RA, Root WB. Why we are still not acting to save the world: The upward challenge of a post-Skinnerian behavior science. Perspectives on Behavior Science. 2018;41:241–267. doi: 10.1007/s40614-018-0162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Branon A, Nastally BL, Mui N. Examining prejudice towards middle eastern persons via a transformation of stimulus functions. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2009;10:295–318. doi: 10.1037/h0100672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Lemke M. Reducing prejudice towards middle eastern persons as terrorists. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2007;8:5–12. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2007.11434269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- dos Reis Soares PF, Rocha APMC, Guimarães TMM, Leite FL, Andery MAPA, Tourinho EZ. Effects of verbal and non-verbal cultural consequences on culturants. Behavior & Social Issues. 2018;27:31–46. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v27i0.8252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durr, M. (2015). What is the difference between slave patrols and modern day policing? Institutional violence in a community of color. Critical Sociology, 41(6), 873–879. 10.1177/0896920515594766

- Edwards F, Lee H, Esposito M. Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116:16793–16798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821204116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faegin, J. R. (2006). Systemic racism: A theory of oppression. Routledge.

- Fong EH, Catagnus RM, Brodhead MT, Quigley S, Field S. Developing the cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:84–94. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Ficklin S, Lee HY. Increasing cultural understanding and diversity in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice. 2017;17:103–113. doi: 10.1037/bar0000076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston S. Enforcing race: A neighborhood-level explanation of black–white differences in drug arrests. Crime & Delinquency. 2019;65:499–526. doi: 10.1177/0011128718798566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geller ES. Applied behavior analysis and social marketing: An integration to preserve the environment. Journal of Social Issues. 1989;45:17–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1989.tb01531.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goltz SM. Considering political behavior in organizations. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2003;4(3):354–366. doi: 10.1037/h0100024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goltz SM. On power and freedom: Extending the definition of coercion. Perspectives on Behavior Science. 2020;43:137–156. doi: 10.1007/s40614-019-00240-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]