Abstract

Purpose

BK Polyomavirus (BKPyV) infection manifests as renal inflammation and can cause kidney damage. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is increased in renal inflammation and injury. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of TNF-α blockade on BKPyV infection.

Methods

Urine specimens from 22 patients with BKPyV-associated nephropathy (BKPyVN) and 35 non-BKPyVN kidney transplant recipients were analyzed.

Results

We demonstrated increased urinary levels of TNF-α and its receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2, in BKPyVN patients. Treating BKPyV-infected human proximal tubular cells (HRPTECs) with TNF-α stimulated the expression of large T antigen and viral capsid protein-1 mRNA and proteins and BKPyV promoter activity. Knockdown of TNFR1 or TNFR2 expression caused a reduction in TNF-α-stimulated viral replication. NF-κB activation induced by overexpression of constitutively active IKK2 significantly increased viral replication and the activity of the BKPyV promoter containing an NF-κB binding site. The addition of a NF-κB inhibitor on BKPyV-infected cells suppressed viral replication. Blockade of TNF-α functionality by etanercept reduced BKPyV-stimulated expression of TNF-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6 and IL-8 and suppressed TNF-α-stimulated viral replication. In cultured HRPTECs and THP-1 cells, BKPyV infection led to increased expression of TNF-α, interleukin-1 β (IL-1β), IL-6 and TNFR1 and TNFR2 but the stimulated magnitude was far less than that induced by poly(I:C). This may suggest that BKPyV-mediated autocrine effect is not a major source of TNFα.

Conclusion

TNF-α stimulates BKPyV replication and inhibition of its signal cascade or functionality attenuates its stimulatory effect. Our study provides a therapeutic anti-BKPyV target.

Keywords: BK polyomavirus, BKPyV-associated nephropathy, Tumor necrosis factor-α, Large T antigen, Nuclear factor-κB

Introduction

BK Polyomavirus (BKPyV) reactivation and virus-induced inflammation are the main causes of kidney allograft damage in BKPyV-associated nephropathy (BKPyVN) [1]. Several risk factors including acute rejection, ischemia/reperfusion and surgical trauma precipitate renal inflammation and subsequent BKPyV reactivation [2, 3]. Once reactivated, BKPyV rapidly replicates, leading to viruria, viremia and even BKPyVN. Recently, BKPyV has even been considered as an oncogenic virus [4, 5]. Because effective anti-BKPyV therapy is not yet available, immunosuppressant reduction is the mainstay of treatment but increases the risk of rejection of the graft. Therefore, finding a specific therapeutic target against BKPyV infection is a crucial issue.

The BKPyV genome consists of a noncoding control region (NCCR) and regions of early gene encoding large T antigen (TAg) and small t antigen, and late gene encoding agnoprotein and viral capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3). NCCR is important in the regulation of viral latency and reactivation and contains many transcription factor-binding sites, including sites that bind nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1. Similar to many viruses, BKPyV infection activates various kinds of antiviral responses in host cells and results in tissue inflammation accompanied by increased production of cytokines and chemokines, which not only affect viral survival but also cause tissue damage. In patients with BKPyVN, increased expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was found in their biopsy specimens [6]. Proinflammatory cytokines are responsible for the necrosis of virus-infected cells and attract inflammatory cells for virus killing; however, some viruses have evolved to make use of these cytokines to facilitate their replication. For example, TNF-α activates cytomegalovirus (CMV) and human simplex virus type 1 replication, which further exacerbates inflammation and damage to the host [7, 8].

TNF-α production can be triggered by kidney injury such as ischemia/reperfusion injury, acute rejection and infectious diseases [8–10]. For instance, TNF-α level was increased 2–3 days prior to clinical evidence of acute rejection [8]. TNF-α and its receptors, TNF-α receptor 1 (TNFR1) and receptor 2 (TNFR2), are not normally present in the kidneys but are abundantly expressed in the context of renal inflammation. After activation by TNF-α, the intracellular domain of TNFR1 is bound by the adaptor protein TNF receptor-associated death domain (TRADD), which recruits other adaptor proteins to activate the inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK) complex [11]. The IKK complex subsequently phosphorylates and degrades IκBα to free NF-κB to activate its targeted genes.

Sadeghi et al. showed an increase in urinary TNF-α levels in kidney transplant recipients with BKPyV DNAuria [6]. In contrast, Ribeiro et al. demonstrated that BKPyV infection caused a downregulation of TNF-α mRNA expression in human collecting duct epithelial cells [12]. However, the mechanism is not fully understood and whether TNF-α blockade suppresses BKPyV replication is unknown. In this study, we investigated whether TNF-α stimulated BKPyV replication and its blockade could inhibit viral replication in human renal proximal tubular cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and materials

Recombinant TNF-α was purchased from R&D Systems (MN, USA). Etanercept was purchased from Vetter Pharma-Fertigung GmbH & Co KG (Ravensburg, Germany). N4-[2-(4-phenoxyphenyl)ethyl]-4,6-quinazolinediamine (QNZ) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The constitutively active IKK2-expressing vector was purchased from Addgene (USA). TNFR1 and TNFR2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) were purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). Urinary levels of TNF-α, TNFR1 and TNFR2 were measured using Quantakine ELISA kits (R&D Systems).

The human renal proximal tubular cell line (HRPTEC) and human monocytic cell line (THP-1) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 1:1 (Gibco™, NY, USA) supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum under 5% CO2. THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Gibco, NY, USA) containing 10% FBS under 5% CO2.

For transient transfection, cells were incubated with 1 µg plasmid and 3 µL of Fugen 6 (Fugene 6TM Roche Diagnostics Ltd, Mannhein, Germany) in 1 mL of culture medium for 4 h and then washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) prior to further experiments according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

qPCR was performed as described previously [13]. Primers used to assay BKPyV TAg and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcript levels (BKPyV TAg: 5-CTGTCCCTAAAACCCTGCAA-3 and 5-GCCTTTCCTTCCATTCAACA-3; BKPyV VP1: GAPDH: 5-TTCCAGGAGCGAGATCCCT-3 and 3-CACCCATGACGAACATGGG-5) were constructed to be compatible with a single reverse transcription-PCR thermal profile (95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s and 60 °C for 1 min). Experimental results are presented as the transcript levels of the analyzed genes relative to the GAPDH transcript level.

Quantitative measurement of BKPyV load

BKPyV load in the urine samples, culture medium or cell lysate was determined by qPCR as described previously [14]. DNA was extracted from the specimens using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To determine viral copies, qPCR was performed as described above. The BKPyV DNA was normalized by analyzing samples in parallel by qPCR for cellular glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase DNA (a housekeeping gene). The limit of detection was 10 copies/mL of BKPyV DNA.

Construction of the BKPyV NCCR-luciferase reporter vectors and luciferase assay

The full-length BKPyV NCCR-luciferase reporter vector was constructed as previously described [15]. To clone the gene between the start codon of TAg and the origin of replication (TAg-Ori) into the luciferase reporter, the BKPyV genome was used as a template, and primers mapping to TAg-Ori (forward primer 5-GCCGGTACCACCGAAAGCCTTTACACAAATGCAAC-3 and reverse primer 5-GCCGGATCCACCGGAAGGAAAGGCTGGATTCT-3) were used. The TAg-Ori fragment in early or late orientation was amplified by PCR and cloned into a pGL4 luciferase reporter vector (Promega, Madison, WI).

A luciferase assay was conducted using the luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase activity (relative light units) was measured in duplicate samples using a luminometer (MLX microtiter plate luminometer, Dynex Ltd, Chantilly, VA). Data are presented as firefly luciferase activity normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was conducted as previously described [16]. Anti-SV40 TAg antibody was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Anti-VP1 antibody was obtained from Abnova (Taipei, Taiwan). Anti-TNFR1 and anti-TNFR2 antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). IκBα, p-IκBα and anti-tubulin antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Urine sample was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to remove the cellular debris, and the cleaned urine samples were used for further measurement. Urinary levels of TNF-α, TNFR1 and TNFR2 were measured using Quantakine ELISA kits (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Patients

A total of 57 kidney transplant recipients at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital from June 2000 to May 2021 were included in this study. Ethics approval (201801596B0) was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Among these 57 recipients, twenty-two subjects had biopsy-proven BKPyVN based on histological findings according to the criteria of the 2018 Banff Working Group classification.

Statistical analysis

All the data are presented as the means ± standard error. Student’s t test was applied to compare the means of two datasets. The correlation analysis used Spearman’s correlation coefficient. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

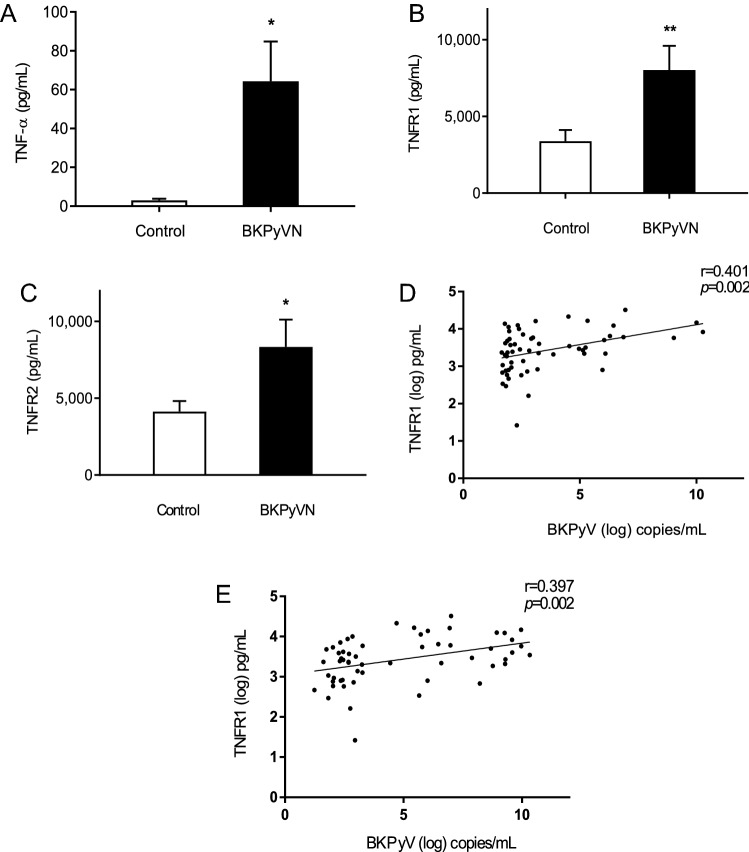

Increased urinary levels of TNF-α, TNFR1 and TNFR2 in patients with BKPyVN

Among 57 kidney transplant recipients, urine samples were obtained from 35 patients without BKPyVN and 22 patients with BKPyVN. As expected, the urinary BKPyV loads in the BKPyVN group were significantly higher than those in the non-BKPyVN group (1.37 ± 0.95 × 109 vs. 1.42 ± 0.94 × 103 copies/mL, p < 0.05). When compared with the non-BKPyVN group, the urinary TNF-α level was significantly higher in the BKPyVN group (Fig. 1a). Similarly, the urinary levels of TNFR1 and TNFR2 were also higher in the BKPyVN group than in the non-BKPyVN group (Fig. 1b, c). The correlation analysis also demonstrated positive correlations between urinary TNFR1 levels and urinary BKPyV loads (Fig. 1d) and between urinary TNFR2 levels and BKPyV loads (Fig. 1e). These results suggest that there is an association between BKPyV infection and the activation of TNF-α receptors.

Fig. 1.

Urinary TNF-α, TNFR1 and TNFR2 levels in kidney transplant recipients with and without BKPyVN treatment. a–c Urine specimens from 57 kidney transplant recipients with BKPyVN (n = 22) and without BKPyVN (n = 35) were collected for measurements of TNF-α (a), TNFR1 (b) and TNFR2 (c) concentrations by ELISA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. d Correlations between urinary TNFR1 level (log10) and BKPyV load (log10). e Correlation between urinary TNFR2 level (log10) and BKPyV load (log10)

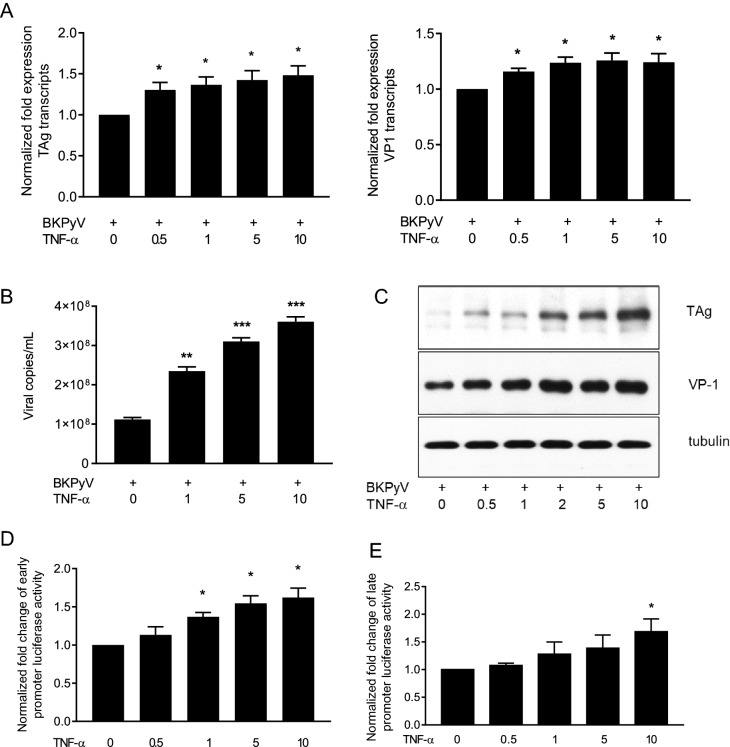

TNF-α enhanced BKPyV replication and promoter activity

To determine the effect of TNF-α on BKPyV replication, HRPTECs were infected with BKPyV and then stimulated with TNF-α. Addition of TNF-α to BKPyV-infected cells stimulated a significant increase of TAg and VP1 transcripts in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). Because a BKPyV life cycle needs 72 h, HRPTECs were infected with BKPyV and stimulated with TNF-α for an additional 72 h. Figure 2b shows a significant increase of viral titers in culture medium. Western blot analysis also showed a proportional increase in expressions of TAg and VP1 proteins in response to the increased doses of TNF-α (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Stimulatory effect of TNF-α on BKPyV replication. a HRPTECs were seeded to 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) and grown to confluence. Cells were then infected with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) for 2 h and subsequently incubated in the presence or absence of TNF-α (0.5–10 ng/mL) for 24 h. TAg and VP1 mRNA expression levels were determined by qPCR (n = 3). b–d HRPTECs were seeded to 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) for 1 day, followed by infection with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) for 2 h and subsequent incubation in the presence or absence of TNF-α as indicated in the figure for 72 h. The viral load in the culture medium (b) was determined as described in the “Materials and methods” (n = 4). TAg and VP1 protein expression levels were assessed by immunoblotting analysis and one of three replicates was shown (c). d, e Cells were transfected with the full-length NCCR-luciferase reporter in early orientation (d) and late orientation (e) overnight followed by the addition of TNF-α (0.5–10 ng/mL) for an additional 24 h. The activity of the BKPyV NCCR reporter was measured by the luciferase assay (n = 4). The fold change of viral transcripts (a) and luciferase activity (d, e) was normalized to the control (no addition of TNF-α) in each experiment. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

The NCCR is the main regulatory region on BKPyV genome to initiate viral replication. To determine whether TNF-α could enhance the BKPyV NCCR-reporter activity, cells were transfected with the full-length NCCR-luciferase reporter followed by stimulation with different doses of TNF-α. The luciferase assay showed that TNF-α significantly stimulated an increase in the activity of the BKPyV NCCR reporter in both early orientation (Fig. 2d) and late orientation (Fig. 2e). This result verifies the finding that TNF-α stimulates both TAg and VP1 transcription.

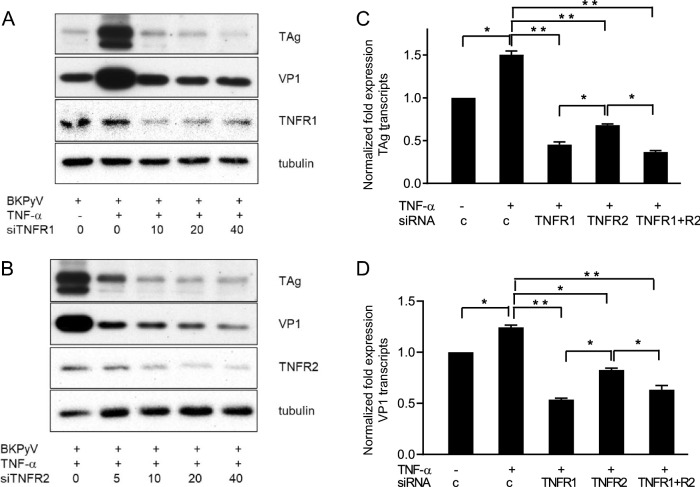

TNF-α stimulated BKPyV replication through TNF-α receptors and its downstream mediator, NF-kB

To determine the role of TNF receptors in BKPyV replication, expressions of TNFR1 and TNFR2 were knocked down by siRNA prior to addition of TNF-α. Upon TNF-α stimulation, productions of TAg and VP1 proteins were increased, while suppression of either TNFR1 or TNFR2 expression by siRNA significantly blocked the TNF-α-stimulated TAg expression (Fig. 3a) and VP1 expression (Fig. 3b). Knockdown of either TNFR1 or TNFR2 abrogated TNF-α-stimulated increase in TAg and VP1 mRNA expressions detected by qPCR (Fig. 3c, d). Compared to TNFR2 knockdown, TNFR1 knockdown or combination of TNFR1 and TNFR2 knockdown caused more substantial reduction in TAg and VP1 expression. These results suggested that both TNF-α receptors were indispensable for TNF-α-regulated BKPyV replication.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of TNF-α-stimulated BKPyV replication by knockdown of TNFR1 and TNFR2 expression. a, b HRPTECs were seeded to 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) overnight. Cells were then transfected with TNFR1 (a) or TNFR2 (b) siRNA (10–40 nM/mL) for 24 h followed by infection with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) for 2 h and further incubated in serum-free medium containing TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 72 h. TAg and VP1 protein expression levels were assessed by Western blot analysis and one of three replicates was shown. C&D. Cells were transfected with TNFR1 (20 nM/mL), TNFR2 (20 nM/mL) or a combination of TNFR1 (20 nM/mL) and TNFR2 (20 nM/mL) for 24 h followed by infection with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) for 2 h and stimulation with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for an additional 24 h. TAg (c) and VP1 (d) mRNA expression levels were analyzed by qPCR (n = 3). The fold change of viral transcripts (c, d) was normalized to the control (no addition of TNF-α) in each experiment. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

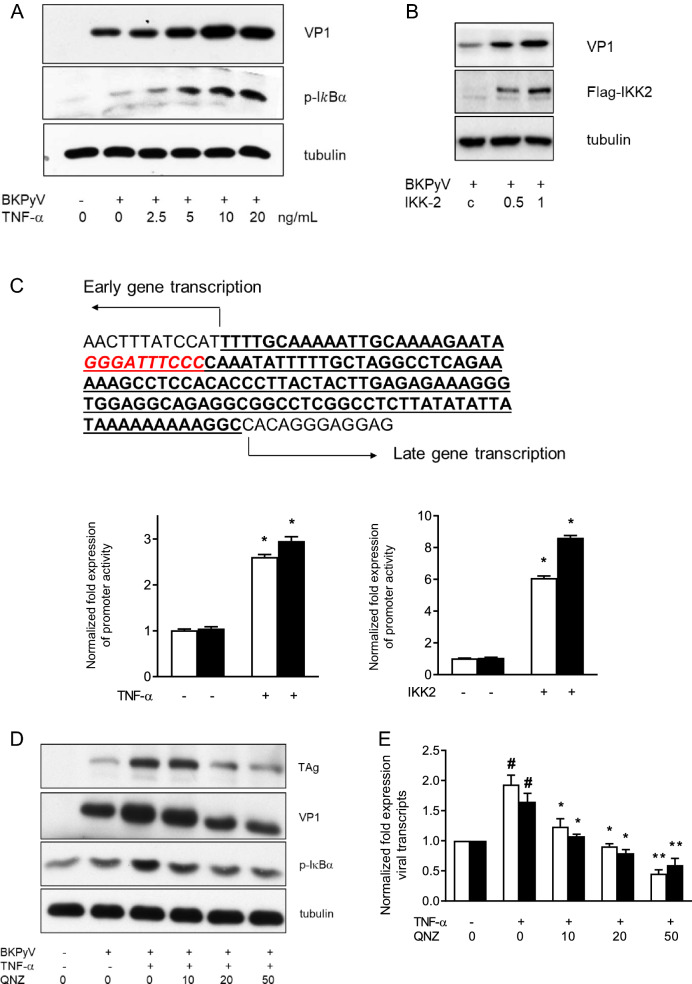

NF-κB is a crucial downstream mediator of the TNF-α-associated cascade, and IκBα phosphorylation, which prevents NF-kB degradation, is considered an indicator of NF-κB activation [17]. BKPyV infection led to a slight increase in the expression of phospho-IκBα (IκBα) (Fig. 4a). The addition of TNF-α to BKPyV-infected cells further enhanced the expression of p-IκBα and VP1. To clarify the importance of NF-κB in BKPyV replication, cells were transfected with a constitutively active IKK2-expressing vector, which can activate p-IκBα [17], followed by infection with BKPyV for an additional 72 h. Compared to transfection with the control vector, transfection with the IKK2-expressing vector significantly increased BKPyV VP1 protein expression (Fig. 4b). A previous study revealed an NF-κB binding site located between the origin of replication and the start codon for the early coding region, which is the consensus region in different BKPyV strains (Fig. 4c). To test the effect of NF-κB overexpression on BKPyV promoter activity, the gene between the start codon of TAg and the origin of replication (TAg-Ori) in early or late orientation was cloned into a luciferase reporter. In line with the finding that used the full-length NCCR-luciferase reporter, TNF-α also stimulated TAg-Ori reporter activity in both orientations (Fig. 4c left panel). Cotransfection of the IKK2-expressing vector and the TAg-Ori reporter caused prominent increases in the reporter activity in both orientations (Fig. 4c right panel). These results further confirm the importance of TNF-α and its main downstream mediator, NF-κB, in BKPyV replication.

Fig. 4.

Suppression of BKPyV replication by NF-κB inhibition. a HRPTECs were seeded to 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) overnight and infected with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL), followed by incubation in the presence or absence of TNF-α (2.5–20 ng/mL) for 72 h. VP1 and p-IκB expression levels were determined by Western blot analysis and one of three replicates was shown. b Confluent cells were transfected with a constitutively active IKK2-expressing vector (0.5, 1 μg/mL) or a control vector (1 μg/mL) overnight followed by infection with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) and incubated for an additional 72 h. VP1 and flag-tagged IKK2 expression levels were assessed by Western blot analysis and one of three replicates was shown (b). c The picture depicts the gene between the start codon of TAg and the origin of replication (Tag-Ori), and the NF-kb binding site is displayed in red color and italicized font. HRPTECs were seeded to 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) overnight and then cotransfected with the TAg-Ori luciferase reporter vectors (white bar: early orientation; black bar: late orientation) or the control luciferase reporter vector and the Renilla luciferase reporter vector overnight followed by stimulation with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for additional 24 h. The reporter activity was normalized by the Renilla luciferase activity (n = 4). d, e Cells seeded on 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) overnight were pretreated with QNZ (10–50 ng/mL) for 2 h followed by infection with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) and further incubated in the presence or absence of TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 72 h (d) or 24 h (e). The expression levels of TAg and VP1 proteins were assessed by Western blot analysis and one of three replicates was shown (d). The mRNA expression levels of TAg (white bar) and VP1 (black bar) were assessed by qPCR (n = 4) (e). The fold change of viral transcripts (e) was normalized to the control (no addition of TNF-α and QNA) in each experiment. # indicates TNF-α vs. control p < 0.05. *QNZ vs. TNF-α alone p < 0.05; **QNZ vs. TNF-α alone p < 0.01

To further verify the role of NF-κB in TNF-α-stimulated BKPyV replication, cells were treated with a potent NF-κB inhibitor, QNZ, prior to administration of TNF-α. The TNF-α-stimulated p-IκB expression was abrogated in the presence of QNZ, verifying its inhibitory effect on NF-κB activation (Fig. 4d). The addition of QNZ significantly reduced the TNF-α-promoted protein expression of TAg and VP1 (Fig. 4d), and mRNA expression (Fig. 4e). These findings confirm the importance of NF-κB activation in TNF-α-promoted BKPyV replication.

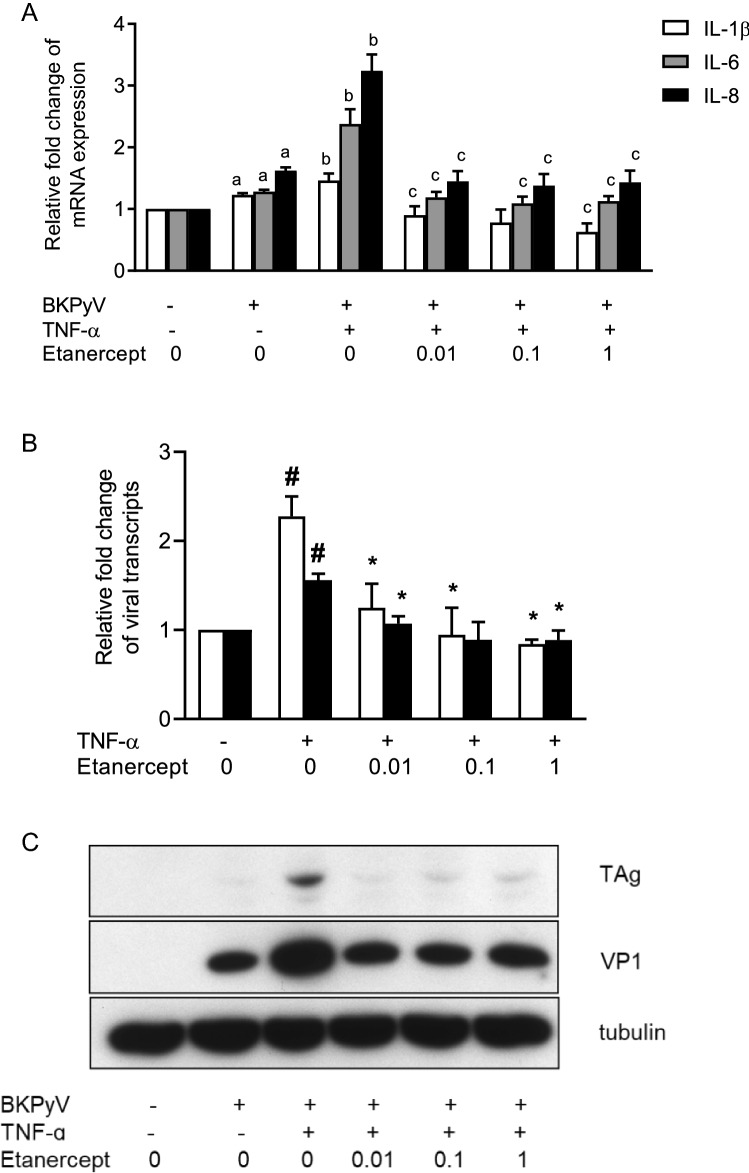

Etanercept suppressed TNF-α-stimulated BKPyV replication

To further examine whether TNF-α blockade could attenuate viral replication, etanercept, a fusion protein of TNFR2 with a constant portion of IgG1 antibody efficiently binding to functional epitopes of TNF-α, was used to inhibit TNF-α functionality. The qPCR results showed that BKPyV infection stimulated the mRNA expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 (Fig. 5a), and upon stimulation with TNF-α, the expression of these cytokines was further augmented. In the presence of etanercept, the BKPyV-stimulated increase in TNF-α expression was significantly reduced. In addition, the TNF-α-enhanced expression of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 was markedly suppressed, and the expression of IL-1β was even lower than that of the unstimulated control. Furthermore, in the presence of etanercept, the TNF-α-mediated increase in TAg and VP1 transcripts was nearly abolished when compared with the unstimulated control (Fig. 5b). The inhibitory effect of etanercept on the TNF-α-stimulated BKPyV replication was further verified by the finding that etanercept inhibited TNF-α-augmented TAg and VP1 protein expression (Fig. 5c). Similarly, administration of etanercept to BKPyV-infected cells for 24 h followed by stimulation with TNF-α for an additional 24 h also suppressed the TNF-α-enhanced increases in TAg and VP1 transcript levels and protein expression (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of TNF-α-stimulated inflammatory cytokines and viral replication by TNF-α blockade. HRPTECs were seeded to 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) and grown to confluence. Cells were infected with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) followed by incubation in the presence or absence of TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 24 h, and then, etanercept at doses ranging from 0.01–1 μg/mL was added for an additional 24 h. The mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 (a) and of TAg (white bar) and VP1 (black bar) (b) were assessed by qPCR (n = 3). TAg and VP1 protein expression levels were determined by Western blot analysis and one of three replicates was shown (c). The fold change of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA expressions (a) and viral transcripts (b) was normalized to the control (no addition of TNF-α and etanercept) in each experiment. aBKPyV vs. the non-BKPyV control p < 0.05; bBKPyV vs. BKPyV + TNF-α p < 0.05; cTNF-α + etanercept vs. TNF-α alone p < 0.05, #TNF-α vs. control p < 0.05, and *TNF-α + etanercept vs. TNF-α alone p < 0.05

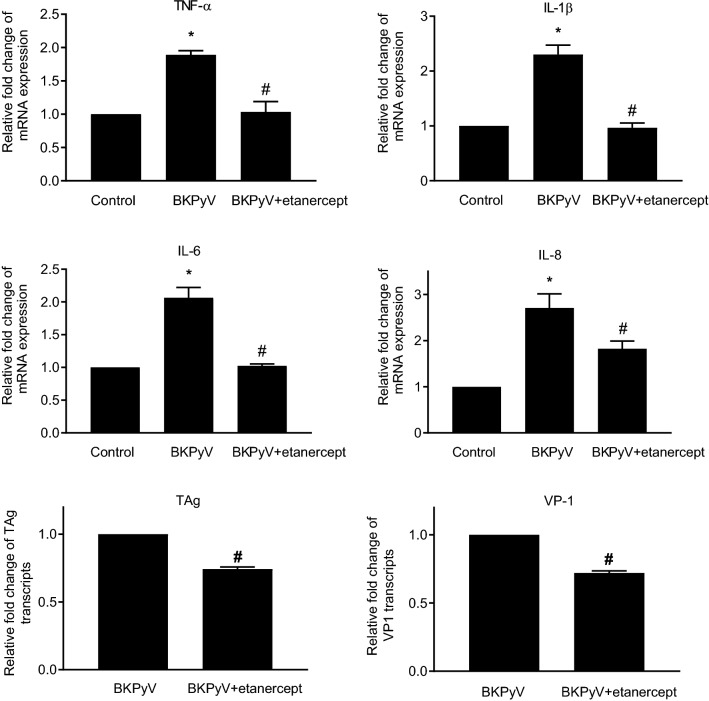

As BKPyV infection stimulated inflammatory cytokines, we examined whether etanercept inhibited BKPyV infection stimulated cytokines. Administration of etanercept to BKPyV-infected cells caused decreased production of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 and concurrently reduced TAg and VP1 transcript levels (Fig. 6). These results suggest that neutralization of endogenous TNF-α by etanercept attenuated BKPyV replication. Together, etanercept suppresses exogenous or endogenous TNF-α-stimulatory BKPyV replication.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of BKPyV-stimulated inflammatory cytokines and viral replication by TNF-α blockade. HRPTECs were seeded to 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) and grown to confluence. Cells were then infected with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) for 2 h and cultured in the presence or absence of etanercept (0.1 μg/mL) for an additional 24 h. The mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TAg and VP1 were determined by qPCR (n = 3). The fold change of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA expressions was normalized to the control (no addition of etanercept and no BKPyV infection) in each experiment. The fold change of viral transcripts was normalized to the control (BKPyV infection only). *TNF-α vs. control p < 0.05; #TNF-α + etanercept vs. TNF-α alone p < 0.05

Monocytes/macrophages and renal proximal tubular cells produced TNF-α following stimulation

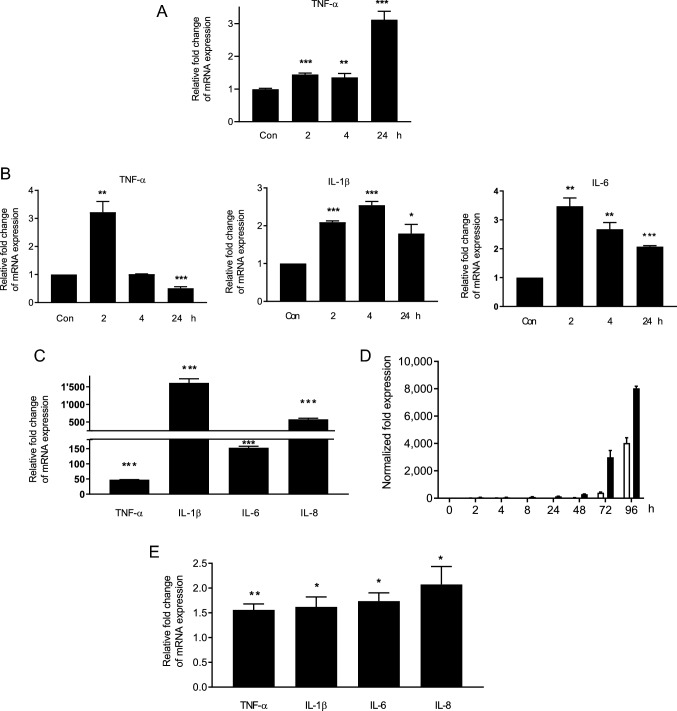

Monocytic cells activated by multiple stimuli, including ischemic/reperfusion injury, rejection and viral infection, play important roles in renal inflammation and TNF-α production [18–20]. We first determined whether monocytic THP-1 cells in responding to inflammatory stimulation could release TNF-α. THP-1 cells activated by PMA were stimulated with polyinosinic acid-polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)). Results of qPCR demonstrated that following stimulation with poly(I:C) for 24 h, expressions of TNF-α were significantly increased (Fig. 7a). To assess whether BKPyV also stimulated TNF-α expression, PMA-stimulated THP-1 cells were infected with BKPyV for 24 h. Results of qPCR demonstrated that TNF-α expression was elevated at 2 h post-infection (h.p.i.) but returned to the baseline level at 4 h.p.i. (Fig. 7b). IL-6 and IL-1β RNA expression was also elevated following BKPyV infection. These results suggest that upon stimulation with poly(I:C) or BKPyV infection, the expression of TNF-α is increased in activated THP-1 cells.

Fig. 7.

Proinflammatory cytokines induced by poly(I:C) or BKPyV infection in THP-1 cells and HRPTECs. a THP-1 cells were seeded to 6-well plates (2 × 105 cells/per well) and grown for 1 day. Cells were then activated by PMA (100 nM) for 24 h and stimulated with 10 μg/mL of poly(I:C) for an additional 24 h. TNF-α mRNA expression was determined by qPCR (n = 3). b Similarly, PMA-activated THP-1 cells were infected with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) in serum-free medium for 24 h. The control in A&B was PMA-stimulated TPH-1 cells without poly(I:C) stimulation or BKPyV infection in serum-free medium for 24 h (con). The mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were assessed by qPCR (n = 3). The fold change of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA expressions was normalized to the control [no stimulation with poly(I:C) (a) or no BKPyV infection (b)] in each experiment. c–e HRPTECs were seeded to 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/per well) for 1 day and were then stimulated with 10 μg/mL of poly(I:C) for 24 h (c) or infected with BKPyV (1 × 106 copies/mL) for 96 h (d, e). TAg (white bar) and VP1 (black bar) mRNA expression levels were analyzed by qPCR (n = 3) (d). The folds of mRNA expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 were normalized to the unstimulated control at 24 h (c, e). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001 or less

To determine whether HRPTECs were also responsible for TNF-α production, cells were stimulated with poly(I:C) for 24 h or infected with BKPyV. Upon addition of poly(I:C), a marked increase of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 expression was observed (Fig. 7c). Following BKPyV infection for 96 h, TAg and VP1 transcripts increased with time, indicating active BKPyV replication (Fig. 7d). At 24 h, mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 were significantly increased although the levels of these cytokines were not markedly elevated as those upon poly(I:C) stimulation (Fig. 7e). These results suggest that monocyte/macrophages and renal proximal tubular cells are one of the cells responsible for TNF-α production.

Discussion

TNF-α is one of the most abundant cytokines in inflamed kidneys, and the plasma and urine levels of TNF-α are increased in different inflammatory kidney diseases, such as acute rejection and glomerulonephritis [8, 21, 22]. In addition, increased urine TNFR levels reflect their shedding from the cell membranes of activated TNF-α-expressing renal cells and are considered a marker of renal inflammation [23, 24]. Our study demonstrated that the levels of TNF-α, TNFR1 and TNFR2 in urine were all significantly increased in BKPyVN patients. Sadeghi et al. reported that the levels of urinary proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-3, soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R), IL-6 and sIL-1R antagonist, were higher in patients with BKPyV DNAuria than those without DNAuria, suggesting a role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of BKPyVN [6]. However, in their study, the difference of the urinary TNF-α levels in these two groups did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, our study demonstrated that in patients with more severe BKPyV infection, biopsy-proven BKPyVN, TNF-α, TNFR1 and TNFR2 levels were all significantly increased, verifying the importance of TNF-α stimulation in BKPyV infection. In addition, urinary levels of TNFR1 and TNFR2 were significantly correlated with urinary BKPyV loads. This study demonstrates a concurrent increase in TNF-α and its receptors, suggesting an amplified effect of TNF-α on renal inflammation in BKPyVN.

TNF-α stimulates or suppresses viral replication depending on viral species. TNF-α promotes the replication of different viruses, including JC virus (JCV), HIV, cytomegalovirus and hepatitis C virus, while TNF-α can also exert a protective effect on herpesvirus family infection [25–29]. In this study, upon TNF-α stimulation, the transcripts and proteins of BKPyV TAg and VP1 and viral load were increased, and its promoter activity was also enhanced, suggesting that TNF-α stimulates transcription and translation. We observed the differences in expressions of viral transcripts, proteins and viral load upon TNF-α stimulation. We speculate that TNF-α may have different effects on transcription, translation of viral components, the packing of viruses and the release of virions from the host cells. Nevertheless, our results indicate a stimulatory effect of TNF-α on BKPyV replication and may reflect our finding of increased urinary TNF-α level in BKPyVN patients.

The present study shows evidence that targeting TNF-α blockade would be beneficial for attenuation of BKPyVN replication. Our study showed that knockdown of either TNFR1 or TNFR2 was sufficient to abrogate TNF-α-stimulated BKPyV replication, suggesting that both TNFR1 and TNFR2 were indispensable for TNF-α-regulated BKPyV replication. NF-κB, an essential TNF-α-associated signaling mediator, is crucial for the replication of several viruses, such as influenza A virus, HIV and CMV [30–32]. Our finding showed that overexpression of the constitutively activated IKK2 stimulated viral protein production, indicating that activated NF-κB is also crucial for BKPyV replication.

The NF-κB binding site on BKPyV NCCR has been verified to be located near the early gene initial codon, and overexpression of the p65 subunit of NF-κB activates BKPyV promoter activity [33]. One study demonstrated that NF-κB and nuclear factor of activated T cell 4 (NFAT4 or NFATc3) interacted cooperatively to enhance the promoter activity and replication of JCV, another human polyomavirus [34]. Our study demonstrated that the BKPyV Tag-Ori promoter containing an NF-κB binding site was triggered by TNF-α and constitutively activated IKK2 expression, confirming an important role of NF-κB in BKPyV reactivation. This finding was further verified, as QNZ blocked the TNF-α-mediated increases in BKPyV TAg and VP1 expression and its promoter activity. Targeting NF-κB inhibition may provide a therapeutic approach against BKPyV infection.

The present study demonstrated a marked inhibitory effect of etanercept on TNF-α-stimulatory BKPyV replication and a BKPyV-induced increase in proinflammatory cytokines. Regardless pre- or post-TNF-α stimulation in BKPyV-infected cells, etanercept significantly suppressed BKPyV replication. Although anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibodies increase the infectious risk of mycobacteria or the reactivation of the herpesvirus family and hepatitis B virus (more in the use of infliximab and adalimumab; less in the use of etanercept), etanercept can be used as an antiviral adjuvant therapy against HCV and HIV [35, 36]. Recently, etanercept was even evaluated as a potential treatment for SARS-CoV-2 infection [37]. The use of anti-TNF-α therapy needs to be cautious in kidney transplant recipients as it might increase malignancy and viral infection [38]. Our study shows a nearly complete suppression of BKPyV replication and may indicate a possibly clinical application of a low-dose etanercept or other TNF-α inhibitors to inhibit BKPyV replication.

Monocytes/macrophages are an important source of TNF-α production in autoimmune and infectious diseases, and allograft rejection [39, 40]. Our study demonstrated a prominent increase of TNF-α and inflammatory cytokines following poly(I:C) stimulation in PMA-activated THP-1 cells, suggesting that monocytes/macrophages play an essential role in inflammatory cytokine production. Another important resource of TNF-α is renal proximal tubular cells. Our study also showed a significant increase of TNF-α upon poly(I:C) stimulation in HRPTECs. Similar to other viruses, our results showed that BKPyV infection stimulated HRPTECs and THP-1 cells to produce inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α [39]. However, the increased TNF-α magnitude by BKPyV infection was far less than that induced by poly(I:C) or other stimulants such as rejection and ischemia/reperfusion injury, suggesting that the BKPyV-mediated autocrine effect is not a major source of TNF-α. Acute rejection characterized by abundant inflammatory cytokine production frequently precedes the development of BKPyVN or coincides with the occurrence of BKPyVN. We speculate that kidney injury promotes TNF-α production and triggers subsequent BKPyV replication.

Conclusion

Our study showed increases in the urinary levels of TNF-α, TNFR1 and TNFR2 in BKPyVN patients. TNF-α stimulation and NF-κB activation promoted BKPyV replication, and TNF-α blockade reduced viral replication, providing a therapeutic target. Our results suggest that TNF-α neutralization by etanercept may have clinical application as an anti-BKPyV treatment. It would be worthwhile to initiate clinical trials of anti-TNF-α therapy for the treatment of BKPyV infection.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Chun-Lin Yen (Kidney Research Center, Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital) for preparation of experiment materials.

Author contributions

Y-JL was involved in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis; J-WW helped in conceptualization, methodology; H-HW contributed to software, visualization; H-HW and Y-JC were involved in resources; H-YY helped in project administration; H-HH contributed to review and editing; C-WY was involved in conceptualization; Y-CT helped in conceptualization, roles/writing—original draft.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants (NRRPG3J6023) from the National Science Council of Taiwan and Grants (CMRPG3H0601 BKPyV, CMRPG3K0592 BKPyV infection) from the Chung Gang Medical Research Project to Dr. Ya-Chung Tian and Dr. Yi-Jung Li.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to privacy reasons. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest. No financial or non-financial interests are directly or indirectly related to the work.

References

- 1.Nickeleit V, Singh HK, Randhawa P, Drachenberg CB, Bhatnagar R, Bracamonte E, et al. The Banff Working Group classification of definitive polyomavirus nephropathy: morphologic definitions and clinical correlations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:680–693. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017050477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch HH, Vincenti F, Friman S, Tuncer M, Citterio F, Wiecek A, et al. Polyomavirus BK replication in de novo kidney transplant patients receiving tacrolimus or cyclosporine: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:136–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamarche C, Orio J, Collette S, Senecal L, Hebert MJ, Renoult E, et al. BK polyomavirus and the transplanted kidney: immunopathology and therapeutic approaches. Transplantation. 2016;100:2276–2287. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li YJ, Wu HH, Chen CH, Wang HH, Chiang YJ, Hsu HH, et al. High incidence and early onset of urinary tract cancers in patients with BK polyomavirus associated nephropathy. Viruses. 2021;13:476. doi: 10.3390/v13030476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenan DJ, Mieczkowski PA, Latulippe E, Cote I, Singh HK, Nickeleit V. BK polyomavirus genomic integration and large T antigen expression: evolving paradigms in human oncogenesis. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1674–1680. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadeghi M, Daniel V, Schnitzler P, Lahdou I, Naujokat C, Zeier M, et al. Urinary proinflammatory cytokine response in renal transplant recipients with polyomavirus BK viruria. Transplantation. 2009;88:1109–1116. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ba0e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walev I, Podlech J, Falke D. Enhancement by TNF-alpha of reactivation and replication of latent herpes simplex virus from trigeminal ganglia of mice. Adv Virol. 1995;140:987–992. doi: 10.1007/BF01315409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiggins MC, Bracher M, Mall A, Hickman R, Robson SC, Kahn D. Tumour necrosis factor levels during acute rejection and acute tubular necrosis in renal transplant recipients. Transpl Immunol. 2000;8:211–215. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(00)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnahoo KK, Meldrum DR, Shenkar R, Chung CS, Abraham E, Harken AH. Early renal ischemia, with or without reperfusion, activates NFkappaB and increases TNF-alpha bioactivity in the kidney. J Urol. 2000;163:1328–1332. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67772-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fietze E, Prosch S, Reinke P, Stein J, Docke WD, Staffa G, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. The role of tumor necrosis factor. Transplantation. 1994;58:675–680. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Lamki RS, Mayadas TN. TNF receptors: signaling pathways and contribution to renal dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2015;87:281–296. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribeiro A, Merkle M, Motamedi N, Nitschko H, Koppel S, Wornle M. BK virus infection activates the TNFalpha/TNF receptor system in polyomavirus-associated nephropathy. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;411:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li YJ, Wu HH, Liu SH, Tu KH, Lee CC, Hsu HH, et al. Polyomavirus BK, BKV microRNA, and urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin can be used as potential biomarkers of lupus nephritis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0210633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li YJ, Chen YC, Lai PC, Fang JT, Yang CW, Chiang YJ, et al. A direct association of polyomavirus BK viruria with deterioration of renal allograft function in renal transplant patients. Clin Transplant. 2009;23:505–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li YJ, Weng CH, Lai WC, Wu HH, Chen YC, Hung CC, et al. A suppressive effect of cyclosporine a on replication and noncoding control region activation of polyomavirus BK virus. Transplantation. 2010;89:299–306. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181c9b51c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li YJ, Wu HH, Weng CH, Chen YC, Hung CC, Yang CW, et al. Cyclophilin A and nuclear factor of activated T cells are essential in cyclosporine-mediated suppression of polyomavirus BK replication. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:2348–2362. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW, Shevchenko A, Bennett BL, Li J, et al. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IkappaB kinases essential for NF-kappaB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwan T, Wu H, Chadban SJ. Macrophages in renal transplantation: roles and therapeutic implications. Cell Immunol. 2014;291:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huen SC, Cantley LG. Macrophages in renal injury and repair. Annu Rev Physiol. 2017;79:449–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrade-Oliveira V, Foresto-Neto O, Watanabe IKM, Zatz R, Camara NOS. Inflammation in renal diseases: new and old players. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1192. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaughlin PJ, Aikawa A, Davies HM, Ward RG, Bakran A, Sells RA, et al. Evaluation of sequential plasma and urinary tumor necrosis factor alpha levels in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1991;51:1225–1229. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199106000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maury CP, Teppo AM. Raised serum levels of cachectin/tumor necrosis factor alpha in renal allograft rejection. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1132–1137. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.4.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Idasiak-Piechocka I, Oko A, Pawliczak E, Kaczmarek E, Czekalski S. Urinary excretion of soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 as a marker of increased risk of progressive kidney function deterioration in patients with primary chronic glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3948–3956. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann U, Bergler T, Rihm M, Pace C, Kruger B, Rummele P, et al. Upregulation of TNF receptor type 2 in human and experimental renal allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:675–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prosch S, Staak K, Stein J, Liebenthal C, Stamminger T, Volk HD, et al. Stimulation of the human cytomegalovirus IE enhancer/promoter in HL-60 cells by TNFalpha is mediated via induction of NF-kappaB. Virology. 1995;208:197–206. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kfutwah AK, Mary JY, Nicola MA, Blaise-Boisseau S, Barre-Sinoussi F, Ayouba A, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha stimulates HIV-1 replication in single-cycle infection of human term placental villi fragments in a time, viral dose and envelope dependent manner. Retrovirology. 2006;3:36. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nukuzuma S, Nakamichi K, Kameoka M, Sugiura S, Nukuzuma C, Tasaki T, et al. TNF-alpha stimulates efficient JC virus replication in neuroblastoma cells. J Med Virol. 2014;86:2026–2032. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arena A, Liberto MC, Capozza AB, Foca A. Productive HHV-6 infection in differentiated U937 cells: role of TNF alpha in regulation of HHV-6. New Microbiol. 1997;20:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laidlaw SM, Marukian S, Gilmore RH, Cashman SB, Nechyporuk-Zloy V, Rice CM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor inhibits spread of hepatitis C virus among liver cells, independent from interferons. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:566 e5–578 e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernasconi D, Amici C, La Frazia S, Ianaro A, Santoro MG. The IkappaB kinase is a key factor in triggering influenza A virus-induced inflammatory cytokine production in airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24127–24134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan JK, Greene WC. Dynamic roles for NF-kappaB in HTLV-I and HIV-1 retroviral pathogenesis. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:286–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forte E, Swaminathan S, Schroeder MW, Kim JY, Terhune SS, Hummel M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces reactivation of human cytomegalovirus independently of myeloid cell differentiation following posttranscriptional establishment of latency. MBio. 2018 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01560-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorrill TS, Khalili K. Cooperative interaction of p65 and C/EBPbeta modulates transcription of BKV early promoter. Virology. 2005;335:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wollebo HS, Melis S, Khalili K, Safak M, White MK. Cooperative roles of NF-kappaB and NFAT4 in polyomavirus JC regulation at the KB control element. Virology. 2012;432:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vigano M, Degasperi E, Aghemo A, Lampertico P, Colombo M. Anti-TNF drugs in patients with hepatitis B or C virus infection: safety and clinical management. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:193–207. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.646986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shale MJ, Seow CH, Coffin CS, Kaplan GG, Panaccione R, Ghosh S. Review article: chronic viral infection in the anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy era in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:20–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sozeri B, Ulu K, Kaya-Akca U, Haslak F, Pac-Kisaarslan A, Otar-Yener G, et al. The clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infection among children with rheumatic disease under biologic therapy: a retrospective and multicenter study. Rheumatol Int. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-05008-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn CS, Jorgenson MR, Descourouez JL, Muth BL, Astor BC, Mandelbrot DA. Management of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor therapy after renal transplantation: a comparative analysis and associated outcomes. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53:268–275. doi: 10.1177/1060028018802814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hober D, Shen L, Benyoucef S, De Groote D, Deubel V, Wattre P. Enhanced TNF alpha production by monocytic-like cells exposed to dengue virus antigens. Immunol Lett. 1996;53:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(96)02620-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paoletti A, Rohmer J, Ly B, Pascaud J, Riviere E, Seror R, et al. Monocyte/macrophage abnormalities specific to rheumatoid arthritis are linked to miR-155 and are differentially modulated by different TNF inhibitors. J Immunol. 2019;203:1766–1775. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to privacy reasons. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.