Abstract

A cancer diagnosis can upend work and family life, leading patients to reallocate resources away from essentials such as food. Estimates of the percentage of people navigating a cancer diagnosis and food insecurity range between 17% and 55% of the cancer patient population. The complexity of addressing food insecurity among those diagnosed with cancer during different phases of treatment is multifactorial and often requires an extensive network of support throughout each phase. This commentary explores the issue of food insecurity in the context of cancer care, explores current mitigation efforts, and offers a call to action to create a path for food insecurity mitigation in the context of cancer. Three programs that address food insecurity among those with cancer at various stages of care are highlighted, drawing attention to current impact and actionable recommendations to make programs like these scalable and sustainable. Recommendations are grounded in the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine social care framework through 5 essential domain areas: awareness, adjustment, assistance, alignment, and advocacy. This commentary seeks to highlight opportunities for the optimization of cancer care and reframe food access as an essential part of treatment and long-term care plans.

A cancer diagnosis can be a traumatic experience causing major disruptions to work and family life (1). Worry about securing enough food for oneself and family should not be at the forefront of a patient’s mind. Yet, food insecurity is common among patients with cancer in the United States (2). It is important to clarify that food insecurity, defined herein as lack of continuous access through socially acceptable means to nutritious and safe foods in the amounts needed for a healthy and active life (3), is a state and not a trait. Food insecurity can vary in terms and duration of when and how patients experience reduced ability to obtain nutritional foods or when access is limited (4). Individuals can experience chronic food insecurity, being unable to obtain nutritious and safe foods for an extended period, or may have episodic or transient food insecurity.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought images of miles-long lines at food banks and food pantries across the country, thrusting food insecurity to the forefront of national consciousness. However, food insecurity has been prevalent in the United States for many years, with more than 10% of households reporting food insecurity in 2020 (4). Among patients with cancer, estimates of food insecurity are much higher (17%-55%) (2). In the context of cancer, food insecurity is an important, yet underrecognized, health-related social risk factor. Among adults with cancer, being female, of Hispanic ethnicity, younger age, unemployed, and having lower household income are associated with food insecurity (5-8), disparities that are mirrored in the broader population.

Cancer care and treatment threatens the financial infrastructure of many families, with both direct (eg, medical fees) and indirect (eg, travel) costs potentially burdening patients (9). Expensive treatment, unpaid or paid caregiving requirements, and the loss of employment and/or insurance benefits can strain finances and pull resources away from household food budgets. Among people living with food insecurity, a cancer diagnosis can further strain finances and exacerbate budget shortfalls, tipping families into a potentially permanent state of financial duress (10). Even for those who are covered by insurance, navigating benefits programs can be a confusing and drawn out process, causing periods of acute financial strain (11). Beyond the direct impact on patients, a cancer diagnosis can have a rippling effect through the family as caregivers sacrifice time and resources to support their loved ones. This commentary explores the issue of food insecurity in the context of cancer care, explores current mitigation efforts, and offers a call to action to create a path for food insecurity mitigation in the context of cancer.

The Impact of Food Insecurity on Cancer-Related Outcomes

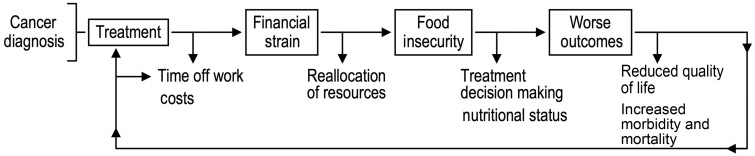

Food insecurity may be a result of cancer treatment and its impact on household financial structures, but food insecurity also portends worse clinical outcomes (12,13), potentially exacerbating health-care costs and delaying return to normal activities (Figure 1). Food insecurity in the general population is a topic of ongoing research, however, less is known about the relationship between household food insecurity and the health and well-being of patients with cancer and their families.

Figure 1.

Food insecurity in cancer. Scheme outlining food insecurity in cancer and up- and downstream factors. This general illustration of the process occurs in a broader socio-environmental context that includes psychosocial factors, access to health care, comorbidities, and other factors.

Maintaining adequate nutrition is critical to cancer therapy success (14). Food insecurity during and after cancer treatment may undermine therapy goals and treatment success and may also add a layer of difficulty to mitigating the side effects of many cancer treatments. Common therapies cause loss of appetite, changes in olfaction and taste, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and difficulty chewing and swallowing that greatly alter and may worsen eating habits, leading to unintended weight loss (15-18). Adapting to these changes in taste and symptoms requires flexibility in food purchasing and preparation, which is difficult while experiencing food insecurity.

Food insecurity has many negative behavioral and social consequences relevant to cancer care such as reduced adherence to therapy (19), compromised cognitive capacity for complex decision making and planning, and lower access to survivorship and self-care resources (20). Food insecurity is linked to mental health issues such as stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts (21), as well as adverse physical health outcomes that are common comorbidities of cancer including obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes (22). As many people affected by cancer are at increased risk for these and other disorders, programs to address food insecurity and help patients eat well throughout the cancer care continuum are essential.

Figure 1 offers a conceptual model of food insecurity in cancer care, which is aligned with other models exploring overall financial toxicity in the context of cancer (9,23). However, longitudinal research is needed to deepen our understanding of where in the cancer care continuum food insecurity is most likely to occur and how it interacts with patient outcomes. This information would allow us to develop detailed frameworks of the mechanisms leading to food insecurity among patients with cancer. Additionally, rigorous prospective study designs are needed to establish the longer-term impact of food insecurity mitigation efforts; this would support future program design and the development of best practices to address food insecurity.

Food Insecurity Mitigation Efforts

Efforts to mitigate food insecurity among people with cancer and their families are critical given the complexity of needs patients experience during treatment and into survivorship. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) 5 A’s social care framework identifies potential strategies for mitigating the adverse health effects of health-related social risk factors including food insecurity: increasing awareness (integrated workflows for identifying social barriers among a patient population), adjustment (alteration of care models to mitigate the influence of social barriers to health), assistance (direct or indirect provision of resources to address social barriers to health), alignment (connection and investment in community assets already in place to address social barriers), and advocacy (promotion of policies to change existing infrastructure that allows social barriers to impede health-care access) (24).

Promisingly, some comprehensive services to address food insecurity among patients with cancer that are consistent with the NASEM model have been developed through nonprofit, community, and hospital initiatives. Three exemplar efforts include the Food to Overcome Outcomes Disparities (FOOD) program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Feed1st at the University of Chicago, and the Center for Food Equity in Medicine, a community-based nonprofit organization. Below, we describe the motivation, programming, and initial outcomes of these initiatives.

Food to Overcome Outcome Disparities

The Immigrant Health and Cancer Disparities Service (IHCD), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, found that 56% to 70% of patients at New York City safety net institutions and 18% to 30% of patients at comprehensive cancer centers are food insecure (5,25). Emergency food resources in the community often do not meet the needs of these patients, because of restricted opening hours, documentation requirements that may exclude immigrants without immigration status, quantity of available food, and a lack of nutritious palatable food options (26). To address the need and these gaps, IHCD launched FOOD, a network of medically tailored food pantries, coupled with cancer nutrition education and food navigators, that are embedded in 15 safety net and comprehensive cancer center clinics throughout the Greater New York metropolitan area (27). Patients are screened for food insecurity and referred by clinicians and social workers; FOOD staff also approach patients in waiting areas to inform them of the program. The FOOD pantries provide a bag of medically tailored groceries with enough food for 5 lunches and 5 dinners for 1 person; the groceries are selected based on the patients’ food preferences (27). During program enrollment, FOOD patient navigators screen for other essential needs, such as financial, housing, transportation, medication payment assistance, and immigration and other legal needs. Navigators refer these patients to IHCD’s comprehensive multidisciplinary patient navigation program, the Integrated Cancer Care Access Network, which can link them with community-embedded and other resources to address essential needs (28).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the most frequent pandemic-related concern of Integrated Cancer Care Access Network patients was food access (59%), and the most frequently needed resource was food (70%). Enrollment in FOOD grew approximately 40%, and the program pivoted to provide food delivery to help patients avoid virus exposure. A randomized controlled trial comparing FOOD interventions (clinic pantry vs monthly food voucher plus pantry vs grocery delivery plus pantry interventions) found that food security scores (29) were statistically significantly improved in all 3 intervention arms at 6 months of study enrollment compared with baseline (30). Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s experience with FOOD demonstrates that a variety of approaches, tailored to the patient population and their nutritional needs during their cancer journey and delivered via the cancer clinic, can improve food security among vulnerable patients (30).

Feed1st

Feed1st at the University of Chicago Medical Center is a proven and enduring system of 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and 365 days a year self-serve, no-barriers food pantries operating in inpatient, emergency, and outpatient areas of a major urban academic medical center since 2010 (31). Most, if not all, emergency food assistance programs, especially those operating from health-care organizations, require evidence of need, a prescription, or other formal referral from a health-care professional. The Feed1st model was co-designed with the communities it serves to eliminate widely known access barriers, including stigma and burden resulting from having to show proof of need and inconvenient hours of operation. Feed1st optimizes both dignity and engagement of people who encounter the pantry system through an inclusive, asset-based approach that regards all individuals as having both gifts and needs (32). Feed1st pantries distribute shelf-stable foods (and, seasonally, produce grown in medical center gardens) in a variety of locations, including inpatient pediatric oncology and outpatient adult oncology units, the hospital cafeteria, a staff break room, waiting areas, emergency departments, and several family break rooms in the children’s hospital. Food is supplied via a partnership with the local food bank that delivers to the medical center loading dock where food is offloaded and stored by plant and facilities personnel. Volunteers, including the Feed1st Medical Student Organization, then distribute the food to the pantries and ensure shelves are regularly stocked. Signage invites people to take as much as they need for anyone who needs it, and a clipboard on the pantry shelves invites users to share the number of people served and their zip code. Usage is measured in pounds of food distributed per month and estimated at the individual and household levels using data obtained by voluntary sign-ins.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, in part because no staffing or face-to-face encounters were required for access, Feed1st was not only sustained but grew to several new locations at the medical center (eg, the cafeteria and staff lounge). Growth was achieved by leveraging long-standing community partnerships, both within the medical center and the broader community, and leveraging a food distribution network operated by medical students and other clinical personnel. The Feed1st model has been emulated and replicated at other medical centers, including during the pandemic, with technical assistance from the Chicago team and a publicly available tool kit (33). The main barrier to growth has been ensuring other institutions and food depositories are aligned with the fully self-serve philosophy that is foundational to the model. Feed1st has been sustained with funding and in-kind support from a variety of sources including the medical center’s community benefit program, research grant funding, philanthropy, and others.

The Center for Food Equity in Medicine

The Center for Food Equity in Medicine is a nonprofit organization that serves patients with cancer at the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center and broader Chicago community. Founded by a patient, the ethos of the Center for Food Equity in Medicine is the belief that no one fighting for his or her life should have to fight for food. The Center’s early initiatives included changes to what was offered on the snack cart that moved around the department and advocacy for meal vouchers or nutrient-dense snacks to be provided to individuals and their caregivers receiving services for 4 or more hours. In the fall of 2017, the Center partnered with Feed1st and the University of Chicago to open an open-access, no-barriers food pantry within the walls of the cancer center. Since opening, the pantry has served patients, caregivers, and staff members from across the hospital system with no questions asked. In 2019, the Center expanded its services and began providing nutritional support to cancer families not only within the hospital’s walls but also in the community. As of 2021, the majority of the Center’s activities are community facing including bimonthly groceries to families at greatest risk for food insecurity, community-based pop-up events to support cancer families with groceries and household items in the communities where they live throughout the year, holiday food, and gift bundles during the holidays. Since its inception, the Center has supported the nutritional needs of approximately 4000 families throughout the Chicago area. The number of families served has grown more than 30% annually since 2019. This work is done with the assistance of other community-based organizations and volunteers and supported by small donors and philanthropic foundation grants.

Challenges in Food Insecurity Mitigation Among Patients With Cancer

Although the work of these organizations is laudable and essential, without widespread policy initiatives and accompanying budgetary allocations, food insecurity interventions will likely struggle to reach the large number of patients in need. Community-based programs that fill the gaps to food access that health-care systems cannot address are predominantly funded by donations and short-term grants where reapplication is necessary. As a result, programs may be implemented for limited periods of time with the goal of demonstrating an immediate return on investment. Funding priorities episodically shift, consequently impacting the ability of organizations to sustain and scale up efforts. In this environment, health-care partners may be challenged to create and maintain referral workflows linking patients in need to food insecurity mitigation services in the community.

The lack of screening for food insecurity in oncology settings is a major barrier to building effective food insecurity mitigation efforts as patients with or at risk of food insecurity often go undetected (2). Universal screening can empower providers to begin addressing food insecurity in their practice by encouraging enrollment in federal benefits programs, providing information on local food depositories, and offering referrals to social workers. Universal screening should be done in a socially and culturally sensitive manner. Although most adult patients (including people with cancer) surveyed in primary care settings find it acceptable to screen for food insecurity and related social risk factors, food insecurity is known to be stigmatizing, and there is reasonable concern about negative unintended consequences (34,35).

Once screened, there may be limited infrastructure to connect or refer patients to the full range of services people with food insecurity and cancer requires. Cancer and cancer treatments frequently lead to metabolic disorders, diet-related symptoms (eg, changes in appetite, nausea), and malnutrition (14), highlighting the importance of diet quality and nutritional guidance during and after treatment. Additionally, after treatment completion, a higher diet quality is linked to improved cancer survival in breast, colorectal, and other cancers (36). Access to qualified dietitians is not universal (37), and expert advice is likely only marginally helpful (and could be potentially harmful) if patients do not have the financial means to access adequate food and put recommendations into practice.

Another issue limiting the adoption of food insecurity mitigation efforts in cancer centers may be hesitancy to embrace the “food is medicine” approach. Food is medicine recenters food insecurity from a purely social issue to a treatable facet of human health and recognizes healthy eating as an essential aspect of cancer treatment (38). Through this lens, clinicians address food access screening and treatment as part of a patient’s overall scope of care. This shift in perspective may require substantial research investment, staff training, and sustainable funding on behalf of health-care facilities. Yet, to ignore food insecurity and other social determinants of health undermines cancer treatment at an individual level and is incompatible with the overall mission of cancer centers to prevent, diagnose, and treat cancer. Although multicomponent strategies to mitigate food insecurity may not be feasible for all health-care systems treating cancer patients, larger centers have the potential to serve as exemplars for food insecurity assessment and mitigation efforts that can then be adapted and scaled to different settings.

A Call to Action

National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated programs have a special responsibility to set the highest possible standards of cancer care. We propose the NCI-designated programs create and implement practical multicomponent, community-oriented strategic plans to alleviate food insecurity in their diverse patient populations and the patients seen in partner hospitals and local clinics. For example, the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (39), a community-based national network for cancer clinical trials and cancer care delivery studies, can be expanded to include programs that address social determinants of health such as food insecurity. We encourage organizations to intentionally work to understand the full breadth of resources available to patients in their communities—not just those near the hospital system base of operation—and develop workflows to screen and link patients to services. Cancer centers have an opportunity to offer financial stability to community organizations already doing related services. We propose a symbiotic relationship wherein community organizations can blend their local connections and community relationships with cancer center expertise in patient medical needs and referrals. The overall goal is to create opportunity for the optimization of care and reframe food access as part of the cancer treatment plan. Guided by the NASEM framework 5 A’s for integrating social care into health-care delivery, we outlined 5 potential strategies to help cancer centers meaningfully address food insecurity in their patient populations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recommendations for addressing food insecurity in cancer centers based on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 5 A’s Framework

| Activity | Food insecurity in cancer care recommendations |

|---|---|

| Awareness | Implement empathic, standardized, nonstigmatizing food insecurity screening throughout the span of cancer care and ensure consistent documentation in health records |

| Adjustment | Implement clinical workflows to accommodate empathic food insecurity assessment and mitigation |

| Assistance | Provide people affected by cancer with useful guidance and resources, such as free or low-cost nutritious food offerings at the site of care; healthy food prescriptions, grocery vouchers, or direct food delivery; and enrollment in local and federal benefits (eg, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) for which they qualify by adding navigation to food and other health-related social needs resources as part of core clinical workflow) |

| Alignment | Invest in partnerships with local organizations that can mobilize food distribution to meet the needs of patients |

| Advocacy | Use data from awareness and adjustment efforts to advocate for policies to prevent food insecurity among patients with cancer and their families across the cancer care continuum |

Awareness

Little is known about the trajectory of food insecurity from diagnosis through survivorship. Understanding the food security status of individuals and population trends could facilitate more targeted referrals, interventions, and programs for cancer populations. By implementing standardized, universal food insecurity screening and electronic medical record documentation throughout the span of care, clinicians and researchers can track and intervene on food insecurity during cancer care and better understand how food insecurity influences patient outcomes and treatment decisions. The benefits of assessment should be balanced with the possibility of stigma. Especially in high-need settings, assistance may be offered to all patients, not only those who screen positive for food insecurity. Prior research shows that about half of all patients receiving information at a medical visit about food and other community-based resources share this information with others (40-42). Consistent documentation of food insecurity assessment can allow for automated referrals to programs and help health-care systems identify high-need patients. Examining the food insecurity assessment on the NCI’s All of Us Research Program would provide prospective, longitudinal data to understand food insecurity as a risk factor for cancer in a diverse, national cohort (43).

Adjustment

Most health-care systems will need to adjust their usual clinical workflows to accommodate patient-centered social barriers assessment and mitigation. Initial patient intake is typically done by a nurse or medical assistant, through registration forms online, or some combination of these. To maximize the likelihood of identifying and successfully intervening on food insecurity while minimizing patient stigma, clinical staff training should include awareness of food insecurity and valid, patient-centered approaches to intervention. Intervention may include making reliable, high-quality referrals to supports in the health system and in the patient’s community, including community health workers. Social workers play a critical role and are specially trained to facilitate enrollment in government-supported assistance programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and school breakfast and lunch programs to promote more long-term support.

Clinical staff including cancer navigators and community health workers, nurses, nutritionists, social workers, and child-life specialists, as well as medical staff including students and residents, should be trained in a biopsychosocial approach to patient care and, within their set of responsibilities, ensure patients’ basic nutritional needs are met. By familiarizing themselves with the NASEM concept of adjustment, providers can consider how medical recommendations may need to be adjusted in consideration of food insecurity. Additionally, those working with survivors of cancer should continue food insecurity screening and referrals for patients once treatment is complete. The cancer experience does not end once someone completes treatment; detailed survivorship guides with wellness guidelines and resources are essential to the recovery process and event-free survival (44).

Assistance

As demonstrated by the examples described above, there is ample opportunity for health-care systems to assist patients with food insecurity through partnerships with their communities. The work of these organizations offers a roadmap to address food insecurity with a food is medicine approach (45). Assistance to reduce food insecurity among patients with cancer may include food is medicine resources such as food prescription programs, medically tailored meals and/or groceries, or open-access food offerings at hospitals and clinics (33,38). Additionally, cancer centers could consider exploring and piloting community programs to assist patients in procuring adequate, healthy and culturally appropriate foods as part of therapy. Many existing food is medicine programs are based in primary care or focus on disease populations such as diabetes or obesity (46). By exploring interdisciplinary collaborations, existing programs may be used or adapted for cancer patient and survivor populations.

Alignment

There is potential for health-care system and community-based food security initiatives to coordinate the continuum of care. This coordination can be formed and sustained with cancer center investment in local organizations that mobilize food distribution to meet the specific needs of patients with cancer. Such investment not only serves to advance a more holistic approach to care that extends from the hospital to the home but also helps sustain vital community-led support organizations. Community health workers, as intermediaries between the health-care system, community organizations, and the people they serve, may be well placed to support these efforts with fair and stable funding for their role (47).

Advocacy

Food insecurity is not an inevitable outcome of the financial distress that accompanies cancer. As articulated in the NASEM social care framework (24), we encourage institutional leadership to advocate for policies to prevent food insecurity among patients and their families across the cancer care continuum. Health-care systems have an effective platform and resources to bring community organizations addressing food insecurity into the conversation, for example, by including representatives on community advisory or other stakeholder boards. Larger hospitals with government relations teams may also play an important role in advocating for federal and local food security initiatives.

Addressing food insecurity among patients with cancer will take a national effort that expands eligibility requirements for existing benefits programs and creates opportunities for food-based interventions to be billable to health plans. Most food access programs for people with cancer are currently sustained through philanthropic investments. Alternatively, or in addition to these investments, insurance or health system reimbursement for food access programs could be considered as a strategy to sustain health-care–based food security initiatives. For example, pathways could be created to enable food access organizations to bill Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance for locally and culturally relevant dietary counseling services and food distribution. Some Medicaid programs are piloting coverage of food and nutrition services for enrollees, including California’s Medi-Cal plan and Kentucky’s and New Jersey’s WellCare plan (48).

These 5 approaches—standardized and patient-centered screening, improved care coordination, direct food assistance, sustainable community partnership, and advocacy for food security initiatives—should be considered by cancer care organizations as viable approaches to help alleviate food insecurity among the people they serve. These approaches are proposed with the structure and resources of NCI-designated programs in mind, as these entities serve as role models and leaders for cancer care advancement in the country. NCI-designated cancer centers might increase their impact on food insecurity prevention and mitigation by deliberate outreach and collaboration with the NCI Community Oncology Research Program. Many people with cancer are not treated at large centers. These approaches are applicable to both large, academic and community cancer care settings and can serve as guideposts for creating locally relevant strategies.

Conclusion

In our current health-care system, cancer care often comes with exceptional upheaval in both physical functioning and financial stability. Many patients are stressed not only about their disease but also about having enough food to get through active therapy and survivorship. NCI-designated cancer centers, as national leaders in cancer prevention and control, have the platform and resources to address food insecurity among patients with cancer. Relying on government and nongovernment organizations to solve this issue is insufficient and deflects from the responsibility of health-care organizations and insurers to optimize their patient outcomes and offer well-integrated and equitable care (49).

Funding

The activities of the National Cancer Policy Forum are supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health, the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Radiology, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Association of American Cancer Institutes, the Association of Community Cancer Centers, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Cancer Support Community, the CEO Roundtable on Cancer, Flatiron Health, Merck, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Patient Advocate Foundation, Novartis Oncology, the Oncology Nursing Society, Pfizer, Inc, Sanofi, and the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer. This work was supported by the US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (USDA/ARS), and funded in part with federal funds from the USDA/ARS under Cooperative Agreement No. 58-3092-5-001. Stacy Tessler Lindau’s effort was supported in part by NIH/NIMHD R01 MD 012630, NIA R01 AG 064949.

Notes

Role of the funder: The sponsors did not play a role in the content of this commentary, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: STL discloses that she is founder and co-owner of NowPow, LLC, a company recently acquired by Unite Us, LLC, where she is a paid advisor and a stockholder. She is president of MAPSCorps, 501c3, a nonprofit organization and serves other nonprofit boards. Neither the University of Chicago nor the University of Chicago Medicine endorses or promotes any NowPow, Unite Us, or MAPSCorps product or service. STL holds debt in Glenbervie Health, LLC and healthcare-related investments managed by third parties. STL is a contributor to UpToDate, Inc. No other authors have relevant disclosures.

Author contributions: MR and AJ supported the conceptualization and administration of this commentary and wrote the original draft. KB, CB, SC, FG, CH, SL, RP, and HS brought their expertise to the conceptualization of this commentary and reviewed/edited all subsequent drafts.

Acknowledgements: We thank Jessica Burch, RDN, LDN, CLC; Gwen Darien, BA; Macy Mears, MS, RDN, LDN; Kristen Sullivan, MPH, MS; and Robert Winn, MD, for their contributions as speakers and planning group members for the National Cancer Policy Forum’s webinar on Food Insecurity among Patients with Cancer. We are grateful for the support of Robin Yabroff, PhD, and the National Cancer Policy Forum staff team: Rachel Austin, BA; Lori Benjamin Brenig, MPH; and Erin Balogh, MPH.

Disclaimers: The authors are responsible for the content of this article, which does not necessarily represent the views of the USDA or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Contributor Information

Margaret Raber, Department of Pediatrics, US Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA.

Ann Jackson, Center for Food Equity in Medicine, Flossmoor, IL, USA.

Karen Basen-Engquist, Department of Behavioral Science, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Cathy Bradley, Department of Health Systems, Management & Policy, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, CO, USA; University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center, Aurora, CO, USA.

Shonta Chambers, Patient Advocate Foundation, Hampton, VA, USA.

Francesca M Gany, Immigrant Health and Cancer Disparities Service, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Chanita Hughes Halbert, Department of Population and Public Health Sciences and Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Stacy Tessler Lindau, Departments of Ob/Gyn and Medicine-Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, USA.

Hilary Seligman, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA; Department of Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Data Availability

No new data were generated or analyzed for this commentary.

References

- 1. Zafar SY. Financial toxicity of cancer care: it’s time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5):djv370. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patel KG, Borno HT, Seligman HK.. Food insecurity screening: a missing piece in cancer management. Cancer. 2019;125(20):3494-3501. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J.. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; 2000. https://nhis.ipums.org/nhis/resources/FSGuide.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2022.

- 4. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A.. Household Food Security in the United States in 2020, ERR-298. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2021.

- 5. Gany F, Lee T, Ramirez J, et al. Do our patients have enough to eat?: food insecurity among urban low-income cancer patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(3):1153-1168. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gany F, Leng J, Ramirez J, et al. Health-related quality of life of food-insecure ethnic minority patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(5):396-402. doi: 10.1200/jop.2015.003962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berger MH, Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N.. A national evaluation of food insecurity in a head and neck cancer population. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):e1539-e1542. doi: 10.1002/lary.29188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zheng Z, Jemal A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. Worry about daily financial needs and food insecurity among cancer survivors in the United States. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2020;18(3):315-327. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abrams HR, Durbin S, Huang CX, et al. Financial toxicity in cancer care: origins, impact, and solutions. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(11):2043-2054. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibab091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS.. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(2):153-165. doi: 10.3322/caac.21443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381-390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Staren D. Social Determinants of Health: Food Insecurity in the United States. Altarum Healthcare Value Hub; 2020. https://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/application/files/5015/9173/3825/Altarum-Hub_RB_41_-_Food_Insecurity.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2022.

- 13. Gundersen C, Ziliak JP.. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(11):1830-1839. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muscaritoli M, Arends J, Bachmann P, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition in cancer. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(5):2898-2913. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nolden AA, Hwang LD, Boltong A, Reed DR.. Chemosensory changes from cancer treatment and their effects on patients’ food behavior: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2285.doi: 10.3390/nu11102285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. Nutrition in Cancer Care (PDQ®)-Health Professional Version. National Cancer Institute; 2022. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/appetite-loss/nutrition-hp-p. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- 17. Ziętarska M, Krawczyk-Lipiec J, Kraj L, Zaucha R, Małgorzewicz S.. Chemotherapy-related toxicity, nutritional status and quality of life in precachectic oncologic patients with, or without, high protein nutritional support. A prospective, randomized study. Nutrients. 2017;9(10):1108.doi: 10.3390/nu9101108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Demark-Wahnefried W, Campbell KL, Hayes SC.. Weight management and its role in breast cancer rehabilitation. Cancer. 2012;118(suppl 8):2277-2287. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McDougall JA, Anderson J, Adler Jaffe S, et al. Food insecurity and forgone medical care among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol Pract. 2020;16(9):e922-e932. doi: 10.1200/jop.19.00736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coughlin SS. Food insecurity among cancer patients: a systematic review. Int J Food Nutr Sci. 2021;8(1):41-45. doi: 10.15436/2377-0619.21.3821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pourmotabbed A, Moradi S, Babaei A, et al. Food insecurity and mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(10):1778-1790. doi: 10.1017/s136898001900435x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pérez-Escamilla R. Food security and the 2015-2030 sustainable development goals: from human to planetary health: perspectives and opinions. Curr Dev Nutr. 2017;1(7):e000513.doi: 10.3945/cdn.117.000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Santacroce SJ, Kneipp SM.. A conceptual model of financial toxicity in pediatric oncology. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2019;36(1):6-16. doi: 10.1177/1043454218810137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gany F, Melnic I, Ramirez J, et al. The association between housing and food insecurity among medically underserved cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(12):7765-7774. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06254-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gany F, Bari S, Crist M, Moran A, Rastogi N, Leng J.. Food insecurity: limitations of emergency food resources for our patients. J Urban Health. 2013;90(3):552-558. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9750-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gany FM, Pan S, Ramirez J, Paolantonio L.. Development of a medically tailored hospital-based food pantry system. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(2):595-602. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2020.0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gany F, Ramirez J, Nierodzick ML, McNish T, Lobach I, Leng J.. Cancer portal project: a multidisciplinary approach to cancer care among Hispanic patients. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):31-38. doi: 10.1200/jop.2010.000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: three-stage design, with screeners; 2012. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8271/hh2012.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2022.

- 30. Gany F, Melnic I, Wu M, et al. Food to overcome outcomes disparities: food insecurity interventions to improve cancer outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2022; doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Makelarski JA, Thorngren D, Lindau ST.. Feed first, ask questions later: alleviating and understanding caregiver food insecurity in an urban children’s hospital. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e98-e104. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Russell C. Rekindling Democracy: A Professional’s Guide to Working in Citizen Space. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lindau Laboratory at the University of Chicago. Feed1st Food Pantry Toolkit: How to Launch an Open Access Food Pantry in Your Organization. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago; 2019. https://d1xwl80c5c04ho.cloudfront.net/sites/obgyn/files/2019-09/Feed1st%20Toolkit_EDITION%201.0%2009132019.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Byhoff E, De Marchis EH, Hessler D, et al. Part II: a qualitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6 suppl 1):S38-S46. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. De Marchis EH, Hessler D, Fichtenberg C, et al. Part I: a quantitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6 suppl 1):S25-S37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Castro-Espin C, Agudo A.. The role of diet in prognosis among cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and diet interventions. Nutrients. 2022;14(2):348.doi: 10.3390/nu14020348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Trujillo EB, Claghorn K, Dixon SW, et al. Inadequate nutrition coverage in outpatient cancer centers: results of a national survey. J Oncol. 2019;2019:7462940.doi: 10.1155/2019/7462940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Downer S, Berkowitz SA, Harlan TS, Olstad DL, Mozaffarian D.. Food is medicine: actions to integrate food and nutrition into healthcare. BMJ. 2020;369:m2482.doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. National Cancer Institute. About NCORP. https://ncorp.cancer.gov/about/. Accessed February 21, 2022.

- 40. Lindau ST, Makelarski J, Abramsohn E, et al. CommunityRx: a population health improvement innovation that connects clinics to communities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2020-2029. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lindau ST, Makelarski JA, Abramsohn EM, et al. CommunityRx: a real-world controlled clinical trial of a scalable, low-intensity community resource referral intervention. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(4):600-606. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2018.304905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lindau ST, Makelarski JA, Abramsohn EM, et al. Sharing information about health‐related resources: observations from a community resource referral intervention trial in a predominantly African American/Black community. J Assoc Info Sci Technol. 2022;73(3):438-448. doi: 10.1002/asi.24560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Denny JC, Rutter JL, Goldstein DB, et al. ; for All of Us Research Program Investigators. The “All of Us” research program. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):668-676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tevaarwerk A, Denlinger CS, Sanft T, et al. Survivorship, version 1.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(6):676-685. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Downer S, Clippinger E, Kummer C, Hager K. Food is medicine research action plan. Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation of Harvard Law School; 2022. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/programs/food-and-society-program/food-is-medicine-project/. Accessed March 1, 2022.

- 46. Platkin C, Cather A, Butz L, Garcia I, Gallanter M, Leung MM.. Food As Medicine: Overview and Report: How Food and Diet Impact the Treatment of Disease and Disease Management. Center for Food As Medicine and Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center; 2022. https://www.nycfoodpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/foodasmedicine.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2022.

- 47. Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):e3-e28. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Garfield K, Koprak J, Haughton J.. Addressing nutrition and food access in Medicaid: opportunities and considerations. The Food Trust, Population Health Alliance, and the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation of Harvard Law School. 2021. http://thefoodtrust.org/uploads/media_items/report_addressing-nutrition-and-food-access-in-medicaid_2021.original.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2022.

- 49. Barnidge EK, Stenmark SH, DeBor M, Seligman HK.. The right to food: building upon “food is medicine”. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(4):611-614. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed for this commentary.