Abstract

Due to the increasing rates of substance use disorders (SUDs), accidental overdoses, and associated high mortality rates, there is an urgent need for well-trained physicians who can grasp these complex issues and help struggling patients. Preparing these physicians occurs through targeted education and clinical exposure in conjunction with medical school curricula in the field of addiction medicine. Medical students can often feel overwhelmed by the medical school curriculum and changes to the curriculum take time, money, and administrative commitment to ratify. Implementing a student organization dedicated to SUD education can be a solution to provide clinical exposure, education and student autonomy in their medical school experience. At Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit vs. Addiction (DvA) is a student-run organization that is filling the gap in SUD education for medical students whilst providing assistance to the community. DvA not only extends clinical education for physicians in training, but it also provides the medical school with an opportunity to allow students to create a blueprint for education initiatives that can be incorporated as a mainstay in the school’s technical trainings. Herein, we describe the evolution of this organization and its activities.

Keywords: Medical education, substance use disorders, harm reduction, medical school

Problem

There is a gap in undergraduate medical education (UME) on substance use disorders (SUDs). This gap fails to address (and may even potentiate) stigma against people with SUDs and leads to unprepared physicians (Berland et al., 2017). Long-standing discrimination and stigma within the medical community towards those with SUDs (Wakeman et al., 2018) inhibit access to treatment, and perpetuate the healthcare system’s abandonment and marginalization of persons who should be able to seek help and trust the healthcare system. There is a clear need for curricular renaissance beyond the textbook, including opportunities for students to experience the field of addiction medicine throughout training and to advocate for patients with SUDs (Miller et al., 2001). Curricular changes are challenging to initiate and sustain. Medical schools may be unwilling to invest if they see no obvious merit, immediate benefit, or support from faculty or students (Bland et al., 2000). Many medical institutions are working to expand education in SUDs and harm reduction; these changes might benefit from student involvement (Ratycz et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2020; Zerbo et al., 2020).

To ensure physicians are well-prepared to treat and advocate for patients with SUDs, student-led organizations with faculty facilitators dedicated to addressing these issues can bridge this gap. Student-led educational initiatives have proven effective in expanding UME (Cox et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2020; Adams et al., 2021; Tookes et al., 2021). Through education and exposure to patients who use drugs, medical students can be better equipped to serve this population. These initiatives also provide a platform for students to interact in a clinical setting with patients before these students become physicians entrusted with patients’ care. Student organization initiatives can address different evidence-based strategies to reduce stigma (e.g., education, advocacy, and events) that facilitate social interaction, thereby encouraging better treatment and long-term care of patients. These student-initiated changes may lead to a physician-led shift in the medical system.

Furthermore, an organization dedicated to SUDs may help to create a bridge between the institution and the community to address mutual distrust felt between patients and physicians (Buchman et al., 2016). These projects allow for improved connection with patients, provide community members with a link to support services, and demonstrate that students have a genuine desire to work within their community. Through different organizational initiatives and volunteering opportunities, patients may experience a new wave of medical education focused on recognizing and serving their needs.

In 2018, students at Wayne State University School of Medicine (WSUSOM) developed Detroit vs. Addiction (DvA). This paper outlines how, through different facets of this organization such as research, outreach, and education, students are given opportunities to mold their education to include more information on SUDs, harm reduction, and advocacy, and play an active role in curriculum development. Similar efforts have seen success. At University of Miami, students sought more inclusive education on harm reduction and developed initiatives that evolved into advocacy and support from schools across the state and local and state legislatures (Tookes et al., 2021). The accomplishments of DvA demonstrate how a student-run organization can initiate exposure and education that lead to permanent curricular changes. This may empower medical students with their training as administration works to develop these changes, using the student organization as a blueprint for interactive teaching and community engagement.

As rates of SUDs increase alongside the harms of substance use (e.g., overdoses, deaths) during the COVID-19 pandemic, medical education needs to include longitudinal exposure to addiction medicine (Carie, 2021). By demonstrating addiction medicine’s place across all specialties, we hope to increase physician engagement in SUD treatment (McCance-Katz et al., 2017). Medical education is constantly growing and changing; however, the process of altering curricula in UME can be slow and does not always include students, who are the main stakeholders in curriculum reform. Establishing student organizations dedicated to filling gaps in medical education is one step in facilitating curriculum change and can serve as the multifaceted foundation for physicians-in-training to serve a growing population in need of empathic healthcare (Ratycz et al., 2018). While some institutions, such as the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, have implemented opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) showing the desire by schools and students to have such education, we present a unique approach that can occur alongside current institutional efforts (Moore et al., 2021).

Approach

Engaging students in expanding the substance use-related curriculum

Student voices are key to creating an effective curriculum at any stage of the educational continuum (Sklar, 2018), especially in professional schools where individuals are training to become the future healthcare workforce. One way to gauge student interest and opinion is through surveys which can be reviewed and incorporated into curricular changes. Survey results can guide what students would like emphasized or believe is vital to their education. Whereas this method can generate diverse ideas to improve UME, implementing these projects often does not involve students. Therefore, we deemed it beneficial for the school administration to partner with student organizations to promote curriculum changes.

Developing the student organization

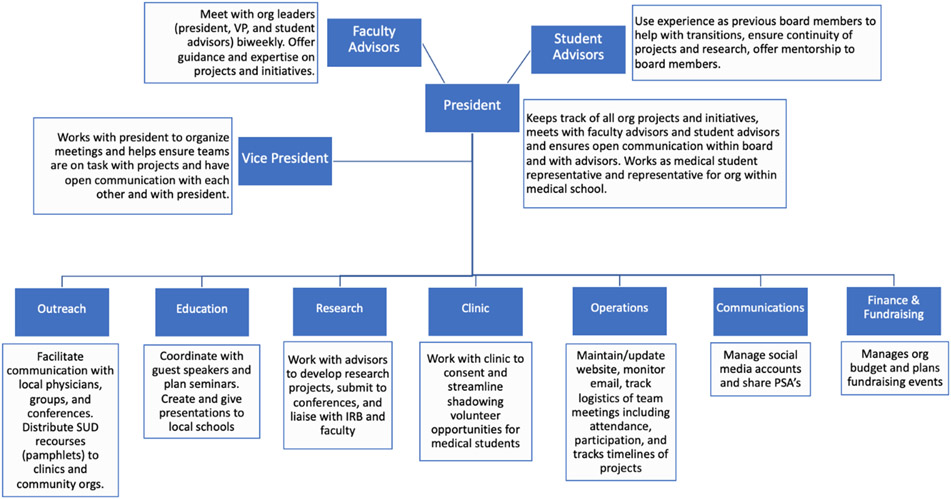

In early-2018, a group of passionate preclinical medical students at WSU-SOM created DvA to expand student experiences and education on SUDs. A team of medical students recognized this gap in substance-use education and how cultural and societal barriers make it difficult to obtain SUD treatment. These students identified initiatives that would improve the availability of relevant resources in the community, including creating pamphlets of local clinics offering Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) to be distributed in the community and advocating for naloxone to be available to patients at risk of overdose after hospitalization. Initial structure of the organization included two executive positions (president and vice president) and seven subcommittee leaders (Figure 1); however, several positions remained vacant. Over time, the organization’s focus expanded to include training a new generation of physicians who are knowledgeable and prepared to address our overdose crisis. Projects also focused on hosting schoolwide seminars with community partners and offering hands-on clinical opportunities. Interest of the entire medical school student body has been integral in expanding DvA from a small student club to an organization hosting events for more than 100 participating members. The process of being granted status as a formal student organization is unique to each school, so we do not believe it is prudent to detail our experiences of this endeavor; however, for reference our institution’s process can be found on the student senate website and we have included these steps in the appendix (see Appendix 2).

Figure 1: Detroit vs. Addiction Board Structure and Function.

Creating outreach and clinical opportunities

Development of outreach and clinical opportunities depended on recruiting community partners and leveraging existing personal networks. Students initially obtained a list of local treatment clinics from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) database to create a catered pamphlet for patients discharged from the Emergency Department. We aimed to verify insurance coverage for patients using Medicaid and asked about opportunities for medical students. One clinic wanted to partner with the medical school to improve delivery of MOUD and advance education on SUDs. Opportunities at the clinic included assisting physicians with initial and ongoing patient visits, learning medication dispensing protocols, and observing group therapy sessions. DvA leaders recognized the importance of reliably supplying student volunteers to the clinic and brainstorming ways to incentivize student participation. To ensure this continuity of volunteers, DvA students met with the school administrator for clinical and outreach opportunities. Under the administrator’s guidance, this new initiative was approved as part of the school’s Service Learning program involving community outreach, education, mentorship, and volunteering. Next, to make these opportunities more logistically feasible, DvA leaders selected clinic times that did not conflict with classes and coordinated transportation for volunteers.

Identifying and establishing relationships with key faculty mentors

DvA leaders recognized the importance of partnering with faculty mentors and community programs to successfully implement projects. Two faculty mentors serve as strong allies and advocates for curricular changes at WSUSOM, and as subject matter experts. One faculty member is an MD with medical education experience leading the psychiatry pre-clinical and clinical curricula, and the other is a PhD with nationally renowned SUD research experience and education experience in translational neuroscience. Under their guidance, initiatives have been piloted within the medical school and later integrated into the formal curriculum (Lien et al., 2020; Moses et al., 2021a).

Barriers to creating an addiction medicine-focused organization

While building the organization, there were uncertainties in levels of interest and sustainability of a specialty-focused student organization. However, addiction medicine is multifaceted and affects the whole student body in some capacity. It affects the practice of inpatient medicine, where treatment can be initiated. It affects the practice of outpatient medicine, where clinics need to follow patients longitudinally. It also affects our community, where members need harm reduction and treatment resources. We received support from community clinics, city departments, and our medical school. We hope our organization will encourage other medical students to advocate for improvements in resources available to patients with SUDs.

Outcomes

Assessing student needs and goals of substance use-related curriculum

After launching the organization, it was important to establish ways DvA could meet the needs of medical students and local communities. This assessment occurred through multiple mechanisms. DvA organized an initial interest meeting to which all students were invited. A voluntary, school-wide survey helped assess other students’ experiences with SUDs and desire for additional training. Results indicated that students had a significant desire and need for more training. More details on the data collected in this survey can be found in Moses et al., 2021a. Students answered open-ended questions on their current SUD training; responses included: “The required curriculum does not adequately train students on working with SUD / overdose patients” and “There is virtually no training… and it makes me very nervous to enter rotations not knowing how to help these patients.” Another consistent area of feedback was that students sought more SUD-related clinical experiences and more information on treatment and harm reduction to share with patients. Furthermore, we found that students at the end of their medical school training had significantly more negative attitudes towards patients with SUDs than those in the preclinical years (Ramos et al., 2020). Shortly after this initial survey, the incoming Class of 2023 completed a more comprehensive survey of their SUD experience and knowledge and their training goals (Moses et al., 2020). These evaluations provided guidance for specific curricular changes and allowed for longitudinal evaluation of how the curriculum impacts students’ knowledge and attitudes towards patients with SUDs.

Implementing new curricula

During the needs assessment survey, a subgroup of students was invited to attend Opioid Overdose Prevention and Response Training (OOPRT) and provide feedback on their experiences. Results were uniformly positive: Students enjoyed the training and believed others should receive it; objective measures demonstrated consistent knowledge improvements (Moses et al., 2021a). Based on student feedback, DvA collaborated with faculty to incorporate OOPRT in the curriculum (for OOPRT content, see Moses et al., 2021b). This training became a permanent part of the first-year medical student curriculum and continues to receive overwhelmingly positive feedback even after COVID-19 restrictions necessitated conversion to an online format (Moses et al., 2021c). Concurrently, DvA worked with clinical faculty to identify the best way to incorporate MOUD-related training during clinical years. Initially, students were given the opportunity to complete an 8-hour MOUD waiver training during their internal medicine clerkship. Feedback was so positive, that the next year it became a required part of the internal medicine clerkship (Lien et al., 2020) and is now required during the pre-clerkship orientation for all students as they begin third year. DvA students and faculty decided to place this training in the general clinical curriculum because they believed it was important that students recognize the training’s relevance for all specialties. DvA also worked with several preclinical course instructors to incorporate SUD awareness, resources, and harm reduction into mandatory courses and included practice patient interactions such as taking a patient history, physical exam skills, and motivational interviewing (MI). MI is an important interventional tool for SUDs (Smedslund et al., 2011) and MI training is incorporated into multiple courses; students are taught how to effectively start an open-ended discussion on substance use with patients and direct the conversation toward facilitating the patient’s needs and goals. Finally, DvA worked with faculty and physicians to develop optional seminars and training in topics related to SUDs and harm reduction. Topics included mechanisms of SUDs, adolescent substance use, and the intersection of individuals with SUDs and the criminal justice system.

Collaborating with local clinics and treatment facilities

Initial collaborations with local clinics facilitated multiple volunteer positions for students including shadowing, medication administration observation, and scribing for clinic physicians. These experiences provided students with insights into SUD treatment and specifically MOUD, which many students would not otherwise encounter during clinical rotations. DvA connected with more local clinics to provide additional opportunities for students, e.g., observing group therapy and other behavioral treatment sessions. At present, DvA is collecting data from formal surveys that examine how these opportunities impact student knowledge and attitudes towards patients and treatments; however, the consistent popularity of these clinical volunteer opportunities is promising. While developing these formal clinical volunteering opportunities, team members borrowed templates from other student-run clinical sites and created additional forms intended to ensure the safety of our volunteers and confidentiality of patients. DvA has continued to develop and expand educational materials and pamphlets to share with patients and the general population, thus providing resources for counseling and immediate treatment. Local stores, clinics, and hospitals in the metro-Detroit area have distributed thousands of DvA’s educational materials (Appendix 1).

Expanding the student organization and ongoing collaborations

When developing an organization that is engaged in multiple projects within and outside the medical school, it is vital to ensure the longevity of the organization and its projects. Collaborations with other student organizations and clinics can advance these efforts. Through collateral ties, we have trained student volunteers at other clinics in opioid overdose prevention and response, shared educational resources, and helped distribute naloxone in the community. The DvA board has expanded and currently consists of 14 officers (see Figure 1). In addition to board members, DvA uses expert student advisors who previously held board positions and are now in clinical training or completing additional degree programs. These students serve as board members and provide more consistent longitudinal involvement. Although it is common practice for second-year, pre-clinical medical students to serve as the sole board members of student organizations, some clinical organizations within our institution chose to include clinical year medical students on the leadership team. Although this type of structure requires more coordination and takes more time to be fully established, we chose this alternative model because it improves continuity and ensure longitudinal engagement in related activities.

Benefits of curricular changes and collaborations to medical students

The efforts of DvA to enhance SUD-related curriculum and training opportunities for medical students have had direct, tangible benefits. We provided evidence that OOPR and MOUD training have significantly improved student knowledge and attitudes related to patients with SUD and harm reduction (Lien et al., 2020; Moses et al., 2021a; Moses et al., 2021b). Volunteer and clinical opportunities have allowed students to interact with this patient population in ways that might not otherwise have been possible prior to graduation. After training, students have reported feeling more comfortable working with patients with SUDs during clinical rotations, and they have developed skills to discuss harm reduction and treatment options with patients with SUDs. These experiences enable students to feel more engaged with patient care, while increasing patients’ access to resources that can have a meaningful impact in improving their outcomes. The specific data related to these evaluations are not presented here because our focus is on the broader development of the organization and the multi-faceted impacts it can have. Nonetheless, statements regarding the efficacy of our efforts are supported by data published in the referenced sources; relevant data can be shared upon request.

Benefits of curricular changes and ongoing collaborations to the community

DvA’s impact is not isolated to medical students. The development of educational materials and increased student comfort working with patients with SUDs has resulted in improved referrals to harm reduction services and treatment for patients (Samuels et al., 2016). Improving the experiences of patients when they enter the hospital may have long-term positive effects. Outside the clinical setting, DvA has engaged in harm reduction efforts in the community, working with other organizations to distribute harm reduction tools and provide education and support to those who need it. Furthermore, DvA students are engaged in advocacy efforts at the institutional, local, and national levels. Students from the organization serve on relevant institutional task forces. DvA’s president serves as the medical student representative for the Opioid Task Force, a collaboration of representatives from several schools within WSU. Task force goals are to identify opportunities for harm reduction and opioid-related education across the institution and community, and to be a platform for interprofessional collaboration and communication. Nationally, DvA collaborates with other advocacy organizations such as the institution’s chapter of the American Medical Association, to help students learn how to advocate for relevant changes. Through these collaborations, DvA students have been integral in developing statewide policies related to naloxone distribution (e.g., implementation of community-based naloxone boxes), and national policies on harm reduction and SUD treatment.

Next Steps

Limitations and barriers to ongoing efforts

Although several student and community organizations sought to collaborate with DvA, there were obstacles. Logistics involving student consent and training increased the barrier to entry. Some community organizations were hesitant to allow too many medical students on their teams because they felt this would deter their community-oriented efforts and conflict with their patient populations’ historic mistrust of the medical community. An important aspect of student organizations working in the community (presented to DvA by an advocate in the SUD population) was to be aware of how students’ desire to help can be perceived. As the majority of Detroit’s population is African American, the importance of a diverse board in which the community is represented is invaluable. Reiterating how prevalent SUD is within the Detroit community and the medical field can aid in recruiting students who acknowledge the need for minority representation in this field of medicine. Student organizations should be extraordinarily mindful not to act as, or give the unintended impression of being, “saviors”. It is important to be aware of how medical students can be perceived in this community. By remaining alert to adverse historical actions and potential for medical students to contribute to these problems, DvA made strong connections with local treatment clinics and several student organizations. By offering opportunities for students to work with people who use drugs, DvA addresses one of its missions of trying to ensure students get exposure before entering their clinical years where they may be subjected to a deep-seated stigma that persists throughout our healthcare system.

Maintaining these important facets of the organization with board transitions each year can be challenging, despite our decision to adopt a leadership structure that is more conducive to knowledge retention. To prevent loss of these values, several measures were implemented to ensure an efficient transition. These include multiple training sessions between predecessors and successor, a detailed transition document, and multiple full board meetings to ensure all teams are aware of their peers’ goals and roles to optimize collaboration and communication within the board.

Future DvA educational initiatives

DvA will continue to facilitate SUD-related curricular changes, advocate for expanding community harm reduction initiatives, educate medical students, and provide opportunities for clinical exposure. We expect to collaborate with faculty and administration to implement a more inclusive clinical skills curriculum wherein students learn how to take a complete medical history for someone with lifetime or current substance use and to instill comfort while doing so. This can be done through simulation-based medical education (SBME) which enhances the teaching and learning experience. The data on how SBME can improve medical students’ understanding of how to properly navigate uncomfortable interactions are promising (Ratycz et al., 2018). Furthermore, this type of training and interaction is desired by students (Moses et al., 2021c).

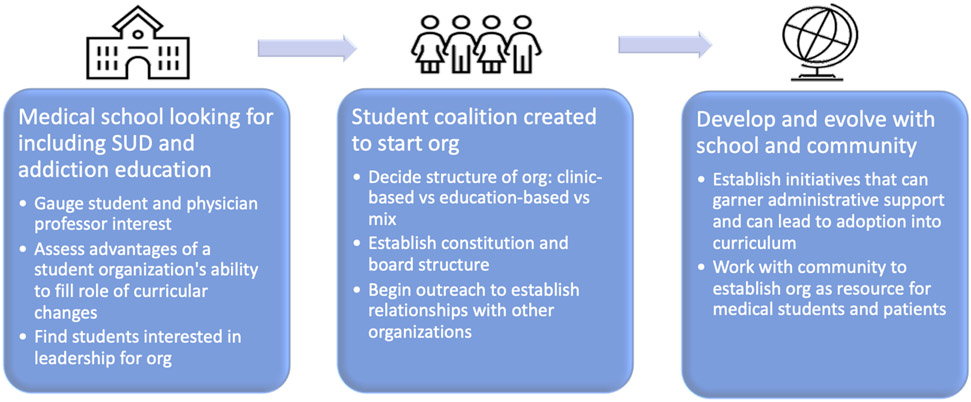

Harm reduction education should be taught to students to promote patient education; much like education regarding nutrition and exercise is important to patients with metabolic and cardiovascular disorders, harm reduction practices should be discussed with patients who use drugs. We hope students who participate in DvA’s programs emerge with greater awareness of their unconscious bias towards this patient population and learn how to better treat patients while addressing their own biases. DvA will collaborate more with student clinics and be a resource for these organizations when they encounter a patient interested in SUD resources or who would benefit from other harm reduction information. Overall, these goals of DvA serve as a blueprint for how student organizations can initiate change in a school’s curriculum and educate medical students to foster well-rounded, empathic physicians (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Detroit vs. Addiction Blueprint.

Future DvA board structure

While the past and current structure onboarded first-year medical students (M1) leadership late into the calendar year, the goal is to smooth this transition. By recruiting M1s a few months earlier, structuring monthly second-year medical students (M2) check-ins, and incorporating M1s into projects throughout the last couple months of the calendar year, the organization will be better prepared to continue once M2s leave for United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 exam preparation in January. This also reduces the burden of M2 leaders toward the end of their tenure. DvA also plans to adopt a more organized and structured role for past board members as student advisors; to create a place within the board for past board members who wish to continue their work or serve as mentors for underclassmen, even after they graduate. The goal is to keep members updated, engaged, and interested to expand clinical, research, and other collaborative opportunities. This can not only benefit current and future members but also the outreach component of the organization. These guidelines will ensure this is an advantageous relationship for both the organization and the students who can speak about their time on the board in a more longitudinal way showing commitment and continuity. Finally, DvA can evolve through interdisciplinary projects. DvA has already co-sponsored events with multiple student groups through educational seminars and resource distribution and there are ample opportunities to engage more of the student body, especially underrepresented minority student groups. Ensuring the students involved with DvA accurately represent our student body is a top priority.

Future clinic and outreach endeavors

As our clinic team creates partnerships and establishes volunteering opportunities for students, we must be sensitive to how we approach this population and people who work closely with them. DvA endeavors to communicate with and listen to individuals who run these organizations and other members of the community to ensure we appropriately engage with those we seek to serve. Our efforts to ensure longitudinal collaborations with consistent volunteering efforts will reduce the perception of students using these opportunities as a form of “medical tourism” and ensure continuity of clinic and client experiences. We also seek to develop more formal training on harm reduction and bias to be taken by all students before volunteering. We recognize these volunteer experiences and brief trainings will not remove deeply-entrenched structural stigma towards people with SUDs within medicine; yet, we believe these efforts help to change attitudes of the next generation of physicians, a major step forward. We also wish to offer more inclusive education on current policies related to illicit and previously-illicit substances such as medicinal uses of cannabis, MDMA, and psilocybin. Our website will share up-to-date information on the organization’s events and provide local and general resources for the community. We have multiple interactive maps for local harm reduction services and SUD treatment facilities (Appendix 1). Our goal is to include these tools on flyers and pamphlets we distribute within the community with a QR code or hyperlink so that anyone in need can easily access these resources. We will use our website’s platform and our organization’s social media presence to introduce ourselves as a group of physicians-in-training dedicated to serving the community and initiating a positive generational evolution in healthcare providers. Meanwhile, the website will engage other medical school students interested in our work, looking for how they can involve their community and school, and/or looking to create their own student organization.

Conclusions

Though DvA has evolved considerably since its creation, we hope our experience can serve as a blueprint for other students wishing to incorporate SUD education and training. A strong foundation of passionate students and supportive faculty advisors will help ensure longevity and establish change as it did with DvA. Much work remains to be done within UME, but with the efforts of students and administration, organizations like DvA can help to ensure future physicians are well-equipped and patients are well-served.

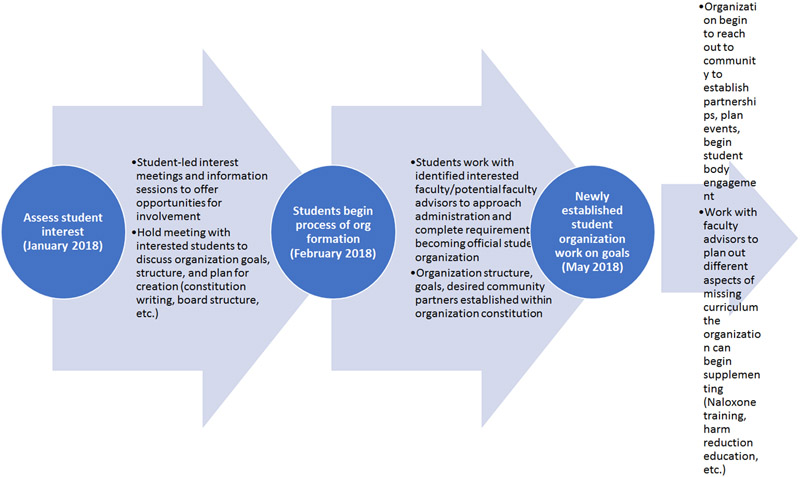

Figure 3: Organization timeline.

Timeline is subject to change and differs according to school administration policies.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to thank the staff and students at Wayne State University School of Medicine for supporting the development and distribution of this survey.

Role of Funding Source:

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Other disclosures:

Faculty effort was supported by the Gertrude Levin Endowed Chair in Addiction and Pain Biology (MKG), Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (Helene Lycaki/Joe Young, Sr. Funds), and Detroit Wayne Integrated Health Network. Trainee effort was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number F30 DA052118 (TEHM). All authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to the conduct or content of this work.

Appendix 1:

Interactive maps for local harm reduction services and SUD treatment facilities at our website: https://detroitvsaddiction.com/resources/

Appendix 2:

Link to WSUSOM Student Senate Constitution which outlines the requirements for accreditation from school senate: https://www.wsusomstudentsenate.com/constitution

Link to form submitted to student senate and outline of steps taken for accreditation:

https://www.wsusomstudentsenate.com/new-student-org-interest-group-proposal-form

“Section 2: Recognition by the Senate To be officially recognized by the Senate, and thus eligible for funding, a Student Organization or Interest Group must: 2.1 Specify a Faculty Advisor who is on WSU SOM faculty and/or is a member of the WSU Physician Group. A new Faculty Advisor Agreement Form must be signed annually and submitted to the Assistant Dean of Student Affairs and the Board of Student Organizations (BSO). 2.2 Gain approval from both the BSO as well as the Assistant Dean of Student Affairs. Once this is complete, the prospective Student Organization or Interest Group may contact the BSO to schedule an appointment to make a proposal before the General Senate. 2.3 Make a proposal to the Senate. Student Organizations must present both a mission statement and a constitution detailing their purpose, goals, activities, and prospective funding needs. Interest Groups need only present a mission statement. 2.4 Receive a 2/3 approval by secret ballot of the General Senate following the presentation and any discussion as deemed necessary by the BSO or General Senate."

Constitution. (n.d.). WSUSOM Senate. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://www.wsusomstudentsenate.com/constitution

Footnotes

Ethical approval: All study procedures were approved by the administration at the School of Medicine. Ethical approval has been waived for any studies discussed in this manuscript. For the pilot study the investigators received IRB exemption status (IRB#: 041919B3X, Protocol#: 1904002169) 04/0/2019. For the study of the Class of 2023, the investigators received IRB exemption status (IRB#: 082419B3X) 08/08/2019. For the study of the Class of 2024, the investigators received IRB exemption status (IRB#: 20062376) 07/14/2020.

Disclaimers: None

Conflict of interest statement: All authors declare no conflict of interest in the conduct of this study.

Data availability statement:

Raw data were generated at Wayne State University School of Medicine. Derived data supporting the findings of any mentioned studies are available from the corresponding author MKG on request.

References

- Adams ZM, Fitzsousa E, & Gaeta M (2021). “Abusers” and “addicts”: towards abolishing language of criminality in US medical licensing exam step 1 preparation materials. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(6), 1759–1760. 10.1007/s11606-021-06616-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold C (2020). The US covid pandemic has a sinister shadow-drug overdoses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 371, m4751. 10.1136/bmj.m4751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berland N, Fox A, Tofighi B, & Hanley K (2017). Opioid overdose prevention training with naloxone, an adjunct to basic life support training for first-year medical students. Substance Abuse, 38(2), 123–128. 10.1080/08897077.2016.1275925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland CJ, Starnaman S, Wersal L, Moorehead-Rosenberg L, Zonia S, & Henry R (2000). Curricular change in medical schools: how to succeed. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 75(6), 575–594. 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman DZ, Ho A, & Illes J (2016). You present like a drug addict: patient and clinician perspectives on trust and trustworthiness in chronic pain management. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.), 17(8), 1394–1406. 10.1093/pm/pnv083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BM, Cote TE, & Lucki I (2019). Addressing the opioid crisis: medical student instruction in opioid drug pharmacology, pain management, and substance use disorders. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 371(2), 500–506. 10.1124/jpet.119.257329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien IC, Seaton R, Szpytman A, Chou J, Webber V, Waineo E, & Levine D (2020). Eight-hour medication-assisted treatment waiver training for opioid use disorder: integration into medical school curriculum. Medical Education Online, 26(1), 1847755. 10.1080/10872981.2020.1847755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCance-Katz EF, George P, Scott NA, Dollase R, Tunkel AR, & McDonald J (2017). Access to treatment for opioid use disorders: medical student preparation. The American Journal on Addictions, 26(4), 316–318. 10.1111/ajad.12550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NS, Sheppard LM, Colenda CC, & Magen J (2001). Why physicians are unprepared to treat patients who have alcohol- and drug-related disorders. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 76(5), 410–418. 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PQ, Cheema N, Follman S, Celmins L, Scott G, Pho MT, Farnan J, Arora VM, & Carter K (2021). Medical Student Screening for Naloxone Eligibility in the Emergency Department: A Value-Added Role to Fight the Opioid Epidemic. MedEdPORTAL, 17, 11196. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses TE, Chammaa M, Ramos R, Waineo E, & Greenwald MK (2020). Incoming medical students’ knowledge of and attitudes toward people with substance use disorders: implications for curricular training. Substance Abuse, 1–7. 10.1080/08897077.2020.1843104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses TEH, Chou JS, Moreno JL, Lundahl LH, Waineo E, & Greenwald MK (2021a). Long-term effects of opioid overdose prevention and response training on medical student knowledge and attitudes toward opioid overdose: a pilot study. Addictive Behaviors, 107172. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses TE, Moreno JL, Greenwald MK, & Waineo E (2021b). Developing and validating an opioid overdose prevention and response curriculum for undergraduate medical education. Substance Abuse, 0(0), 1–10. 10.1080/08897077.2021.1941515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses TEH, Moreno JL, Greenwald MK, & Waineo E (2021c). Training medical students in opioid overdose prevention and response: comparison of in-person versus online formats. Medical Education Online, 26(1), 1994906. 10.1080/10872981.2021.1994906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, Board on Behavioral, C., and Sensory Sciences, & Committee on the Science of Changing Behavioral Health Social Norms. (2016). Ending Discrimination Against People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: The Evidence for Stigma Change. National Academies Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wayne/detail.action?docID=4648298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabelais E, & Rosales E (2020). Response to “How should academic medical centers administer students’ ‘domestic global health’ experiences?” Ethics and linguistics of “domestic global health” experience. AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(5), 458–461. 10.1001/amajethics.2020.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos R, Moses T, Garmo M, Waineo E, & Greenwald M (2020). Knowledge and attitude changes towards opioid use disorder and naloxone use among medical students. Wayne State University Medical Student Research Symposium. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/som_srs/20 [Google Scholar]

- Ratycz MC, Papadimos TJ, & Vanderbilt AA (2018). Addressing the growing opioid and heroin abuse epidemic: a call for medical school curricula. Medical Education Online, 23(1), 1466574. 10.1080/10872981.2018.1466574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels EA, Dwyer K, Mello MJ, Baird J, Kellogg AR, & Bernstein E (2016). Emergency department-based opioid harm reduction: moving physicians from willing to doing. Academic Emergency Medicine, 23(4), 455–465. 10.1111/acem.12910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar DP (2018). Implementing curriculum change: choosing strategies, overcoming resistance, and embracing values. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(10), 1417–1419. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedslund G, Berg RC, Hammerstrøm KT, Steiro A, Leiknes KA, Dahl HM, & Karlsen K (2011). Motivational interviewing for substance abuse. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD008063. 10.1002/14651858.CD008063.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Slat S, Woods G, Cross K, Macleod C, & Lagisetty P (2020). Assessing medical student interest in training about medications for opioid use disorder: a pilot intervention. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 7, 2382120520923994. 10.1177/2382120520923994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tookes H, Bartholomew TS, St Onge JE, & Ford H (2021). The University of Miami infectious disease elimination act syringe services program: a blueprint for student advocacy, education, and innovation. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 96(2), 213–217. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman SE, & Rich JD (2018). Barriers to medications for addiction treatment: how stigma kills. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(2), 330–333. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1363238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbo E, Traba C, Matthew P, Chen S, Holland BK, Levounis P, Nelson LS, & Lamba S (2020). DATA 2000 waiver training for medical students: lessons learned from a medical school experience. Substance Abuse, 41(4), 463–467. 10.1080/08897077.2019.1692323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at Wayne State University School of Medicine. Derived data supporting the findings of any mentioned studies are available from the corresponding author MKG on request.