For decades, the population of the US has experienced shorter life expectancy and higher disease rates than populations in other high-income countries. The gap in life expectancy between the US and 16 peer countries increased from 1.9 years in 2010 to 3.1 years in 2018 and 4.7 years in 2020.1 The US health disadvantage is even worse in certain states, with states such as Alabama and Mississippi having the same life expectancy as Latvia (75 years).2,3

Disparities in health across the 50 states are growing, a trend that began in the 1990s.4 For example, in 1990, life expectancy in New York was lower than in Oklahoma, but the trajectories separated sharply in the 1990s and, by 2016, New York ranked third in life expectancy, whereas Oklahoma ranked 45th.2 By 2019, mortality rates at ages 25 to 64 years differed by a factor of 216% between the states with the highest mortality rate (565.1 per 100 000) and the lowest rate (261.9 per 100 000), up from 188% in 1999. The widening gap cannot be explained by changes in the racial and ethnic composition of states, because the same trend occurred within racial and ethnic groups. For example, among non-Hispanic White individuals, mortality rates at ages 25 to 64 years differed by a factor of 228% between the states with the highest mortality rate (571.7 per 100 000) and the lowest rate (250.2 per 100 000), up from 166%in 1999.5

Although the divergence in state health trajectories might reflect changes in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, a more likely potential explanation is the growing polarization of public policies across states.

Although the divergence in state health trajectories might reflect changes in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, a more likely potential explanation is the growing polarization of public policies across states. States assumed increasing powers decades ago, when the Reagan administration in the 1980s and the US Congress in the 1990s promoted devolution, a policy aimed at shifting authorities and resources (eg, block grants) to the states.6

States with different political priorities and economic circumstances made diverse policy choices, widening the gap across the states in education, wages, taxes, social programs, corporate profits, wealth inequality, and infrastructure. Health outcomes changed as states took different approaches to Medicaid, workplace and product safety, the environment, tobacco control, food labeling, gun ownership, and needle exchange programs. These policies had predictable consequences. For example, states that raised cigarette taxes experienced fewer tobacco-related illnesses. Injury deaths increased in states that relaxed speed limits and motorcycle helmet laws.7

In the past decade, the growing polarization of “red” and “blue” states has further widened the divide on policies ranging from Medicaid expansion and abortion to education, immigration, redistricting, unions, and criminal justice. Conservative governors increasingly use preemption, the authority to override local governments, to block liberal health policies (eg, indoor smoking bans).6 States have preempted local regulations on nutrition (eg, menu labeling, food deserts) and, as of 2013, 45 states had enacted statutes to limit local firearm regulations.8

The COVID-19 pandemic removed any doubt that state policies can affect health outcomes. East Coast states (eg, New York, New Jersey) that responded to the first wave of the pandemic in the spring of 2020 with strict protective measures achieved relatively quick control of community spread within as much as 8 weeks,9 and they blunted subsequent surges by reinstating those policies. In contrast, states that had spent decades opposing public health provisions were among the most resistant to COVID-19 guidelines and took active measures to resist restrictions. Some elected officials made a political issue out of challenging scientific evidence, embracing dubious theories, and labelling public health safeguards as infringements on personal freedom. Conservative governors used preemption to reverse efforts by mayors and school districts to control local transmission rates.

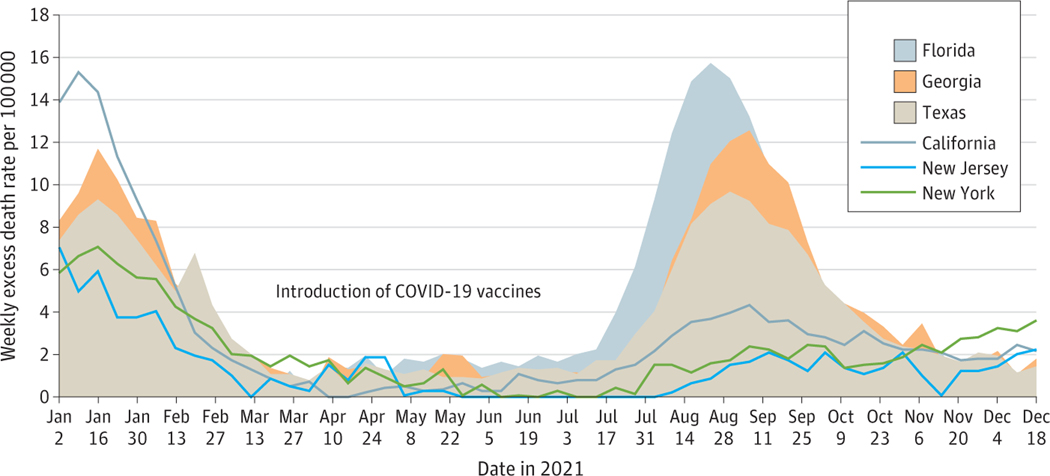

These policy choices may have been associated with increased COVID-19–related morbidity and mortality. States that rushed to curtail lockdowns in the spring of 2020 experienced more protracted surges in infections and disruptions to their economies.9 In 2021, excess deaths were disproportionately concentrated in states where resistance to COVID-19 vaccination was prevalent. For example, excess death rates in Florida and Georgia (more than 200 deaths per 100 000) were much higher than in states with largely vaccinated populations such as New York (112 per 100 000), New Jersey (73 deaths per 100 000), and Massachusetts (50 per 100 000). States that resisted public health protections experienced higher numbers of excess deaths during the Delta variant surge in the fall of 2021 (Figure). Between August and December 2021, Florida experienced more than triple the number of excess deaths (29 252) as New York (8786), despite both states having similar population counts (21.7 million and 19.3 million, respectively).10

Figure. Weekly Excess Death Rate (per 100 000) in Selected States, 2021.

Predicted (weighted) excess deaths from all causes, by week, as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the weeks ending January 2, 2021, through December 25, 2021.10 Population counts for calculating excess death rates were obtained from the CDC WONDER bridged-race population estimates for 2020 (https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/saved/D178/D278F621).

State control over health outcomes shows no signs of waning. Legislatures have passed and are considering numerous laws designed to transform elections, civil rights, school curricula, and climate policy. New laws and court decisions could affect health and health care and exacerbate inequities. The Texas abortion bill and other challenges to Roe v Wade, new state laws to nullify gun regulations, and other sweeping measures suggest that states will be wielding greater control over the health and safety of their populations. Increasingly, an individual’s life expectancy in the US will depend on the state in which they live.

The implications of these state-level actions require medical and public health professionals and the public to shift their focus from the political standoffs in Washington, DC, to the escalating activity in state capitols and to be vigilant about policies that threaten health and safety, deepen inequities, or target vulnerable groups. The nation should also reflect on federalism and decide whether it wants health policy to come in 50 varieties, considering that the Constitution and Tenth Amendment granted public health authority (ie, “police powers”) to the states.

States are laboratories for experimentation, but fragmented health policy has consequences. While other countries mounted a national response to COVID-19, the US was hobbled by 50 response plans and, to date, has lost more than 1 million lives. Although state governments have the right to set their own path and policies, the public should decide whether life expectancy should be part of the experiment.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr Woolf reported receiving partial funding from grant UL1TR002649 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Woolf SH, Masters RK, Aron LY. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 on life expectancy across populations in the USA and other high income countries: simulations of provisional mortality data. BMJ. 2021;373(1343):n1343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.University of California, Berkeley. United States Mortality DataBase. Accessed February 16, 2022. http://usa.mortality.org

- 3.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. OECD.Stat: health status: life expectancy. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=30114

- 4.Couillard BK, Foote CL, Gandhi K, Meara E, Skinner J. Rising geographic disparities in US mortality. J Econ Perspect. 2021;35(4):123–146. doi: 10.1257/jep.35.4.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About underlying cause of death, 1999–2020. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

- 6.Montez JK. Deregulation, devolution, and state preemption laws’ impact on US mortality trends. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(11):1749–1750. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. High and Rising Mortality Rates Among Working-Age Adults. National Academies Press; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briffault R. The challenge of the new preemption. Stanford Law Rev. 2018;70(6):1995–2027. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, Weinberger DM, Hill L, Taylor DDH. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March-July 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1562–1564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/excess_deaths.htm