Abstract

Paracoccidioidomycosis, a systemic mycosis restricted to Latin America and produced by the dimorphic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, is probably acquired by inhalation of conidia produced by the mycelial form. The macrophage (Mφ) represents the major cell defense against this pathogen; when activated with gamma interferon (IFN-γ), murine Mφs kill the fungus by an oxygen-independent mechanism. Our goal was to determine the role of nitric oxide in the fungicidal effect of Mφs on P. brasiliensis conidia. The results revealed that IFN-γ-activated murine Mφs inhibited the conidium-to-yeast transformation process in a dose-dependent manner; maximal inhibition was observed in Mφs activated with 50 U/ml and incubated for 96 h at 37°C. When Mφs were activated with 150 to 200 U of cytokine per ml, the number of CFU was 70% lower than in nonactivated controls, indicating that there was a fungicidal effect. The inhibitory effect was reversed by the addition of anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibodies. Activation by IFN-γ also enhanced Mφ nitric oxide production, as revealed by increasing NO2 values (8 ± 3 μM in nonactivated Mφs versus 43 ± 13 μM in activated Mφs). The neutralization of IFN-γ also reversed nitric oxide production at basal levels (8 ± 5 μM). Additionally, we found that there was a significant inverse correlation (r = −0.8975) between NO2− concentration and transformation of P. brasiliensis conidia. Additionally, treatment with any of the three different nitric oxide inhibitors used (arginase, NG-monomethyl-l-arginine, and aminoguanidine), reverted the inhibition of the transformation process with 40 to 70% of intracellular yeast and significantly reduced nitric oxide production. These results show that IFN-γ-activated murine Mφs kill P. brasiliensis conidia through the l-arginine–nitric oxide pathway.

The mononuclear phagocytic system constitutes an important effector mechanism in the natural and adaptative immune responses against several pathogens. Kashino et al. (25) suggested that macrophages (Mφs) play a fundamental role in resistance to the dimorphic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, the etiological agent of paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM), one of most common systemic mycoses in Latin America (17, 39).

Previous studies have demonstrated that murine peritoneal Mφs activated with the cytokine gamma interferon (IFN-γ) exert a fungicidal effect on both yeast and conidial forms of P. brasiliensis (5, 8, 9). These findings also suggested that cytokines, especially IFN-γ, play an important protective role in resistance to PCM, as demonstrated recently by Cano et al. (10) using IFN-γ depletion in intratracheally infected A/Sn and B/10.A mice. This depletion caused an exacerbation of pulmonary infection and earlier dissemination to the liver and spleen of both resistant (A/Sn) and susceptible (B/10.A) animals. Additionally, it was shown that killing was independent of the oxidative burst products (5).

Mφs activated by IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) produce two kind of reactive products characterized by their cytotoxic activity: reactive oxygen intermediates and reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI) (16, 36).

Nitric oxide (NO), one of the most important RNI, is generated by the oxidation of one of the nitrogens in the amino acid l-arginine (21, 22). The inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is responsible for NO production and is involved in inflammation and infection (30). There is no evidence that in Mφs iNOS can be expressed without previous intervention of cytokines (such as IFN-γ) and microbial products, such as LPS.

More direct evidence for the role of iNOS has been afforded by the identification of relatively selective, nontoxic compounds that inhibit this enzyme. Aminoguanidine a nucleophilic hydrazine compound whose methylation results in the loss of both potency and selectivity for iNOS (14), has been identified as an iNOS-selective inhibitor. NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate salt (LNMMA), another NO inhibitor, has been shown to antagonize the l-arginine-dependent cytotoxicity on activated Mφs (20). Additionally, arginase (ARG) acts directly on the specific substrate, l-arginine, blocking the reaction.

Experimental models have demonstrated that NO is responsible for the cytotoxic effect exerted on a variety of microorganisms, including certain parasites, such as Schistosoma mansoni (23), Leishmania major amastigotes (4, 19, 29, 31), Trypanosoma cruzi (34, 37), and Plasmodium falciparum and P. chaubaudii (12, 42) and several fungi, such as Cryptococcus neoformans (18), Histoplasma capsulatum (27, 35), the hyphal form of Candida albicans (1), and the yeast form of Penicillium marneffei (26). However, NO does not appear to be involved in the fungicidal activity of murine or human alveolar Mφs against other fungi such as Aspergillus fumigatus conidia (32, 41) and Pneumocystis carinii (40).

The purpose of this work was to determine if the cytotoxic effect exerted by recombinant IFN-γ (rIFN-γ)-activated murine peritoneal Mφs against intracellular P. brasiliensis conidia is mediated by an NO production mechanism. Additionally, we attempted to determine if NO produced by these activated Mφs was directly responsible for the cytotoxic effects observed previously (8, 9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male BALB/c mice, 8 to 12 weeks old, obtained from the breeding colony of the Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas, Medellín, Colombia, were used in all experiments. Mice were supplied with sterilized commercial food pellets, sterilized bedding, and fresh acidified water.

Reagents and media.

Tissue culture medium RPMI 1640, fetal bovine serum, sulfanilamide, naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride, phosphoric acid (H3PO4), aminoguanidine hemisulfate salt (AG), LNMMA, and ARG were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo. Complete tissue culture medium (CTCM) consisted of RPMI 1640 containing 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Mouse rIFN-γ and anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (MAb) (purified anti-mouse IFN-γ) were obtained from PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.

Fungus and production of conidia.

P. brasiliensis isolate ATCC 60855, previously found to sporulate freely on special media, was used (38). The techniques used to grow the mycelial form and collect and dislodge conidia have been reported previously (38). Briefly, the stock mycelial culture was grown in a liquid synthetic medium, modified McVeigh-Morton broth, at 18 ± 4°C with shaking. Growth was homogenized, and portions were used to inoculate agar plates; the latter were incubated at 18 ± 4°C for 2 months. After this time, sterile physiological saline containing 0.01% Tween 20, 100 U of penicillin, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml was used to flood the culture surface. Growth was removed with a bacteriological loop; the resulting suspension was pipetted into an Erlenmeyer flask containing glass beads and then shaken in a reciprocating shaker at 250 rpm for 30 min. The homogeneous suspension was filtered through a syringe packed with sterile glass wool (Pyrex fiber glass, 8-μm pore size; Corning Glass Works, Corning, N.Y.). The filtrate was collected in a polycarbonate centrifuge tube and centrifuged for 30 min at 1,300 × g; the pelleted conidia were washed and counted with a hemacytometer, and their viability was assessed by the ethidium bromide-fluorescein diacetate technique (6). For the experiments, only inocula with a conidial viability of >90% were used.

Peritoneal Mφs.

Peritoneal cells (PC) were collected from the abdominal cavity of each of 10 to 12 BALB/c mice by repeated lavage with 10 ml of fresh RPMI 1640 plus 100 U of penicillin and 100 μg of streptomycin. PC from all mice were pelleted by centrifugation at 200 × g for 10 min and then pooled. PC were washed once and resuspended at 106 cell per ml of CTCM. A 0.25-ml volume of PC was dispensed into each chamber of the eight-chambered Lab-Tek slides (Nunc, Inc., Naperville, Ill.). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2–95% air for 2 h; then the nonadherent cells were removed by aspiration, and the adherent monolayers were rinsed with RPMI 1640. The number of nonadherent cells was determined and subtracted from the number of incubated PC. Approximately 2 × 105 adherent cells per chamber formed a monolayer (8, 9).

Treatment of Mφ monolayers.

Mφ monolayers were kept overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2–95% air and treated with 0.25 ml of CTCM or CTCM containing different concentrations of rIFN-γ (10 to 200 U/ml). When anti-IFN-γ MAb and NO inhibitors were used, they were diluted in CTCM and then added to the monolayer at different concentrations (41.7 to 333.3 ng/ml for MAb; 1.0 to 10 U/ml for ARG; and 0.05 to 1.0 mM for LNMMA and AG).

Infection of Mφs.

Conidia were suspended in 2 ml of CTCM containing 30% (vol/vol) fresh mouse serum from the same normal BALB/c mice used to obtain Mφs. Conidial suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 20 min for opsonization to take place (7). Mφ monolayers were infected with 0.02 ml of the conidial suspension, which gave a conidium-to-Mφ ratio of 1:10 (8, 9).

Time course measurements.

The above cocultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2–95% air for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. After each incubation period, duplicate sets of culture supernatants were withdrawn and stored at −70°C for NO determination. The slides were fixed with absolute methanol, air dried, and stained by the silver methenamine (Gomori) or modified Wright (Sigma) technique.

Microscopic determination of intracellular transformation.

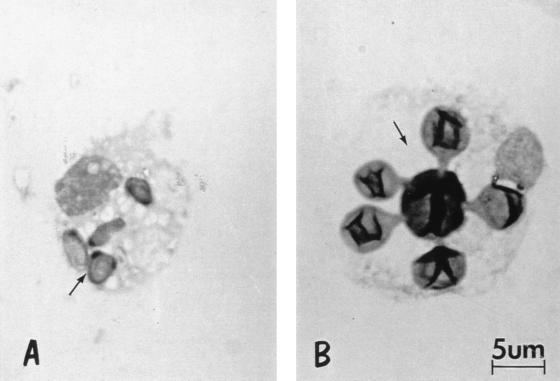

Over 200 intracellular P. brasiliensis fungal cells were examined per monolayer, and the morphology of the fungus, e.g., conidium, yeast cells, or multiple budding yeasts, was recorded (Fig. 1). Percent transformation was calculated as number of intracellular yeast cells/200 intracellular fungal cells × 100.

FIG. 1.

Morphology of intracellular P. brasiliensis. (A) Nontransformed conidium; (B) transformed multiple budding yeast cell. Magnification, ×1,000.

CFU determination.

After incubation of cocultures at 37°C in 5% CO2–95% air for 6, 7, and 8 days, cells were harvested by aspiration and washed with distilled water to lyse Mφs. Each coculture supernatant and the corresponding washings were mixed to a final volume of 1 ml. The total volume of each well was plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar, modified (Mycosel; BBL). Plates were incubated at 18°C, and colonies were counted daily until no increase in CFU was observed. Percent fungicidal activity was calculated as 100 − (experimental CFU × 100)/control [Mφ without rIFN-γ] CFU).

NO determination.

The concentration of NO2 in the culture supernatant was used as an indicator of NO generation and measured with the Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride, 2.5% H3PO4) (15). Briefly, 50 μl of the coculture supernatants was added to an equal volume of the Griess reagent in triplicate wells of a 96-well microplate (catalog no. 3075; Falcon, Lincoln Park, N.J.). After incubation at room temperature for 10 min, absorbance (540 nm) was determined in a Labsystems Multiskan MCC/340 microplate reader. NO2 was determined by using sodium nitrite as a standard (15).

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation for at least three duplicate experiments (n = 6). Comparisons between groups were analyzed by the Student t test using the Pearson product moment correlation (program STATISTICA for Windows, version 4.0), with the significance level assumed to be P < 0.05. Additionally, the correlation between NO production and transformation of P. brasiliensis conidia (as log value) was calculated; NO production was considered the independent variable (the x axis), and the log of transformation was considered the dependent variable (the y axis).

RESULTS

Intracellular transformation of P. brasiliensis conidia.

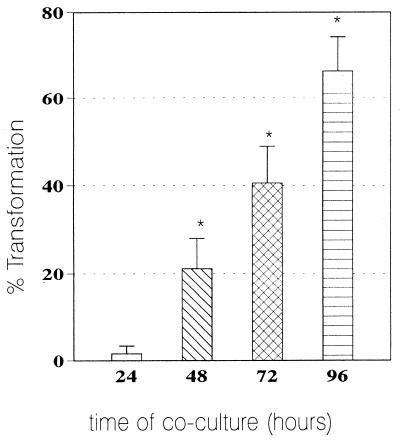

As shown in Fig. 2, in nonactivated monolayers (no IFN-γ), transformation of the conidia began as early as 48 h of coculture and reached maximal values (66% ± 8%) at 96 h. This period was chosen as the optimal time for the next experiments.

FIG. 2.

Intracellular transformation from conidium to yeast. Mean transformation values for intracellular P. brasiliensis conidia after 24, 48, 72, and 96 h (n = 6 experiments) are shown. Range bars represent standard deviation. ∗, significant (P < 0.05) increase after 48 to 96 h of coculture.

Effect of rIFN-γ activation of Mφs on the transformation of intracellular P. brasiliensis conidia.

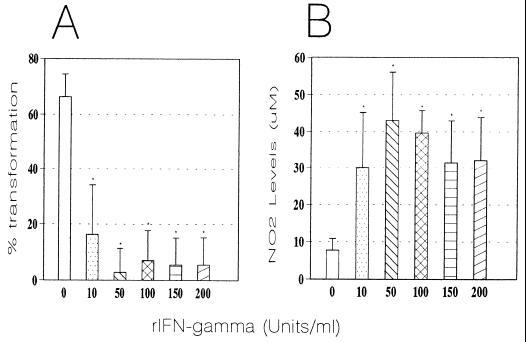

Compared with nonactivated Mφs, the addition of rIFN-γ resulted in significant (P < 0.0001) dose-dependent inhibition of the conidium-to-yeast transformation process (Fig. 3A). Maximal inhibition was observed in monolayers activated with 50 U of this cytokine per ml. To determine whether the inhibitory effect exerted by rIFN-γ-activated Mφs on intracellular conidia was mediated directly by this cytokine, we conducted experiments involving the addition of anti-IFN-γ MAb. Initially, we determined if the various concentrations of the MAb to be used were nontoxic for the cocultures after 96 h of incubation. Similar transformation values were observed in both MAb-treated and controls with no MAb. When MAb was added to the cytokine-activated monolayers, we observed a significant (P < 0.0001) increase in the conidium-to-yeast transformation (42%) in comparison with the cytokine-activated monolayers without MAb (3%). Values were similar to those of controls without rIFN-γ but with MAb. On the other hand, the addition of different concentrations (10 to 200 U/ml) of rIFN-γ to conidia alone did not affect their transformation.

FIG. 3.

Effect of rIFN-γ activation of Mφ on intracellular conidium-to-yeast transformation (A) and NO production by rIFN-γ-activated Mφs (B). (A) Mean transformation values of intracellular P. brasiliensis conidia after 96 h of coculture with murine Mφs activated with different concentrations of rIFN-γ (n = 6 experiments/concentration). Range bars represent standard deviation. ∗, significant decrease (P < 0.0001) compared to nonactivated Mφs (0 rIFN-γ). (B) Levels of NO2− production by murine Mφs activated with different concentrations of rIFN-γ and cocultured with P. brasiliensis conidia for 96 h (mean for six experiments). Range bars represent standard deviation. ∗, significant increase (P < 0.0001) in comparison to nonactivated-Mφs (0 rIFN-γ).

NO production by rIFN-γ-activated Mφs.

We examined NO production by rIFN-γ-activated Mφs which had been infected with P. brasiliensis conidia and cocultured for 96 h. As shown in Fig. 3B, nonactivated Mφs had only basal production of NO and low NO2− levels. However, when Mφs were activated with rIFN-γ, there was a significant (P < 0.0001) increase in NO production. The maximal NO2− levels observed corresponded to monolayers activated with 50 U of IFN-γ per ml with high values of 43 ± 13 μM. We also determined NO production in the supernatants of Mφs that had been activated with the cytokine in the absence of P. brasiliensis conidia; they also showed a significant increase in NO production (33 μM) in comparison with both nonactivated and noninfected Mφs (5 μM).

Since IFN-γ has been suggested to play a role in Mφ NO production, we attempted to determine if the latter was inhibited by anti-IFN-γ antibody (36). Anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody was used at different concentrations and added to the cultures simultaneously with the cytokine (50 U/ml). The levels of NO2− in the supernatants were assayed at 96 h. NO production was significantly reduced in the cytokine-activated cultures that had been treated with antibody (4 μM), in contrast to cocultures activated with the cytokine but not treated with MAb (50 μM).

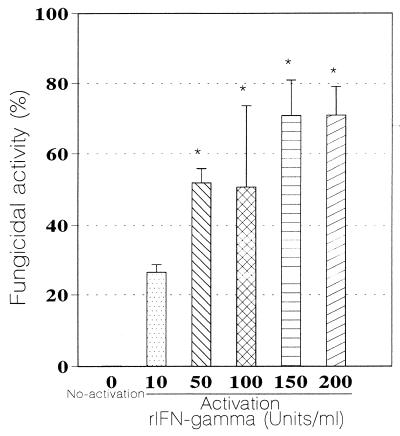

Fungicidal effect of rIFN-γ-activated Mφs against P. brasiliensis conidia.

Monolayers activated with rIFN-γ exerted a significant dose-dependent fungicidal activity compared with nonactivated Mφs (Fig. 4). Monolayers activated with different concentrations of rIFN-γ showed a significant fungicidal activity (P < 0.001). The maximal fungicidal activity, 71% ± 8%, was observed with monolayers activated with 200 U/ml (P < 0.001).

FIG. 4.

Fungicidal activity of rIFN-γ-activated Mφs against P. brasiliensis conidia after 8 days of coculture (n = 4 experiments). Range bars represent standard deviation. ∗, significant increase (P < 0.001) versus nonactivated Mφs (0 rIFN-γ).

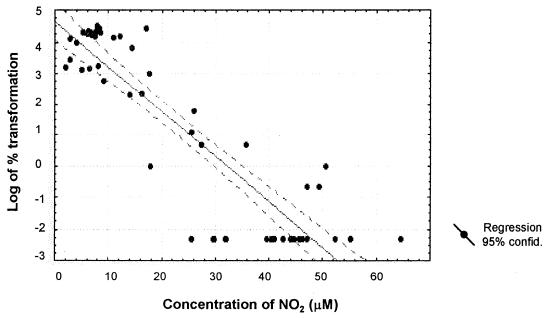

Correlation between NO production and transformation of P. brasiliensis conidia.

The amount of NO produced by Mφs showed an inverse but significant correlation with the percentage of conidia that had transformed into yeast in the monolayer (r = −0.8975) (Fig. 5). Data from cocultures showed that when the NO2− levels reached 20 to 70 μM, there was complete inhibition of transformation. On the other hand, monolayers that produced lower NO2− concentrations allowed transformation to take place (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Correlation between NO2− levels produced by rIFN-γ-activated Mφs and degree of conidium-to-yeast transformation. Data are from cocultures incubated for 96 h with or without IFN-γ (n = 55); r = −0.8975).

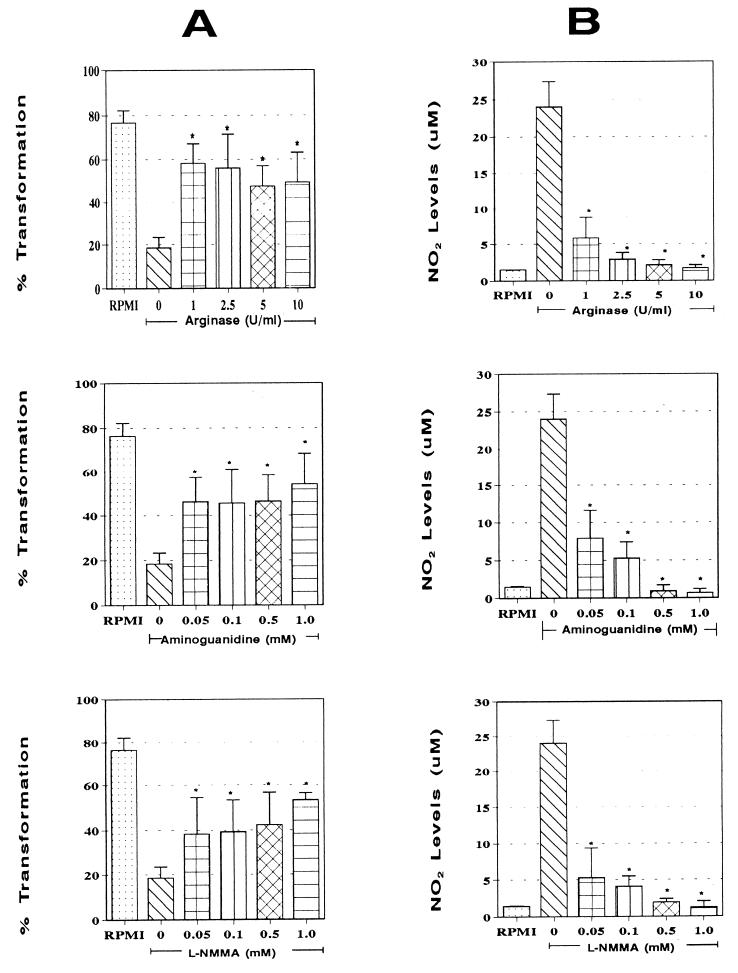

Effect on the intracellular transformation of P. brasiliensis conidia by the addition of NO inhibitors.

The proportions of P. brasiliensis conidia that transformed inside rIFN-γ (50 U/ml)-activated monolayers after treatment with different concentrations of the NO inhibitors ARG, AG, and LNMMA were determined. As shown in Fig. 6A, the addition of ARG, AG, or LNMMA resulted in significant (P < 0.0005) reversion of the inhibition process exerted by the cytokine compared to rIFN-γ-activated untreated monolayers. Values were similar to those observed with normal Mφs.

FIG. 6.

Effect of addition of NO inhibitors to rIFN-γ-activated Mφs on intracellular conidium-to-yeast transformation (A) and NO production by rIFN-γ-activated Mφ (B). (A) Mean transformation values of intracellular P. brasiliensis conidia after 96 h of coculture with Mφs activated with 50 U of rIFN-γ per ml in the presence of different concentrations of ARG, AG, or LNMMA (n = 6 experiments/concentration). Range bars represent standard deviation. ∗, significant increase (P < 0.0005) compared to rIFN-γ-activated untreated Mφs (0 inhibitor). First columns (RPMI) represent the maximum transformation value observed inside nonactivated Mφs. (B) Levels of NO2− production by Mφs activated with different concentrations of rIFN-γ and cocultured with P. brasiliensis conidia for 96 h (mean for six experiments). Range bars represent standard deviation. ∗, significant increase (P < 0.0001) in comparison to nonactivated-Mφs (0 rIFN-γ).

Blockage of NO production by addition of ARG, AG, and LNMMA.

NO production by rIFN-γ (50 U/ml)-activated Mφs was significantly inhibited when different concentrations of ARG, AG, and LNMMA were added (Fig. 6B). This inhibition was dose dependent, with total blockage being exerted by the maximal concentration of each of the three inhibitors used. Values obtained were similar to those for nonactivated Mφs. A significant (P < 0.0001) decrease in levels of NO production was recorded in comparison to cytokine-activated, non-inhibitor-treated Mφs.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates, for the first time, that IFN-γ-induced production of NO renders murine Mφs capable of restricting the intracellular growth of P. brasiliensis, indicating that this is an important mechanism displayed by effector cells. Support for this conclusion is provided by the following observations: (i) cytokine-induced production of NO by Mφs inhibited the conidium-to-yeast transformation process; (ii) addition of anti-IFN-γ MAb reverted this inhibitory effect and resulted in blockade of NO production; (iii) rIFN-γ-activated Mφs exerted an important fungicidal activity against P. brasiliensis, as shown by a significant CFU reduction in comparison with control, nonactivated Mφs; (iv) there was a significant inverse correlation between NO2− levels and fungal transformation; and (v) treatment with any of three different NO inhibitors blocked NO synthesis and reverted the inhibition of the conidium-to-yeast transformation.

The results presented here confirm the protective role of IFN-γ in PCM, as previously demonstrated by several groups (5, 10, 33). Thus, this cytokine appears to be a major mediator of resistance against P. brasiliensis infection in mice, as it promotes the antifungal activity of the Mφs through NO production.

In human and experimental PCM, several findings suggest that T-cell-activated Mφs play a fundamental role in host resistance to P. brasiliensis. When the fungus enters the host, it has to interact with various effector cells (Mφs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, monocytes), and for successful colonization, it should resist their microbiostatic and microbicidal mechanisms. Several groups have studied the interactions of murine and human effector cells, with both the infective conidia and the parasitic yeast forms of P. brasiliensis (5). Treatment with lymphokine-containing supernatants from mitogen (concanavalin A)-stimulated spleen cells (8) or rIFN-γ (5)-activated murine peritoneal Mφs resulted in potent fungicidal activity against P. brasiliensis. Furthermore, treatment of human monocytes with cytokines, derived from supernatant of ConA-stimulated mononuclear cells and cocultured with the fungus, significantly inhibited multiplication compared to control monocytes (33). However, killing by activated murine Mφs could not be abrogated by superoxide dismutase, catalase, or azide, suggesting that the fungicidal mechanism was independent of the oxidative burst products (5). Our results reveal that in vitro the inhibitory and/or killing mechanism used by activated murine Mφs against this pathogen involves NO production, confirming the results obtained in vivo by Bocca et al. (2) suggesting that NO is important in killing. However, during the course of the infection with P. brasiliensis, NO also induces immunosuppression, manifested by a decrease in Ia antigen expression and a depression of the immunoproliferative responses of spleen cells (2, 3). These NO-induced immunosuppressive effects have been reported previously; it has been shown that NO production influences activated mouse Mφ by restricting T-cell expansion (30).

It is important to determine if in vivo NO plays a protective role in PCM. Experiments are under way to confirm the expression of iNOS, production of cytokines related to IFN-γ or TNF-α, and the effect of treatment with AG on the survival time of BALB/c mice infected intranasally with P. brasiliensis conidia.

The inhibition of P. brasiliensis growth by NO and RNI, as demonstrated in the present study, is in agreement with results obtained for most of the pathogenic fungi that have been studied (reviewed in reference 11). The anti-H. capsulatum activity of rIFN-γ-activated macrophage of the RAW 264.7 cell line depends on the generation of NO from l-arginine and is completely inhibited by the NO inhibitor LNMMA (27, 35). On the other hand, the inhibition of C. neoformans growth by human cytokine-activated astrocytes was paralleled by production of nitrite and reversed by the inhibitors of the NO synthase, NG-methylmonoarginine and NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (28). Additionally, it has been demonstrated that interleukin-12 and interleukin-18 synergistically induced NO-dependent anticryptococcal activity of peritoneal cells by stimulating NK cells to produce IFN-γ (45). Blasi et al. (1) demonstrated that hyphae of Candida albicans, but not yeast cells, were susceptible to the mechanisms employed by murine Mφs, which likely involve stable nitrogen-containing compounds. In addition, Vázquez-Torres et al. (43) suggested that NO is candidastatic by itself and is associated (but not involved directly) with other Mφs candidacidal agents, such as peroxynitrite (44).

Other fungi such as P. marneffei (13, 26) and Rhizopus spp. (24) are also susceptible to the effect of nitrogen compounds. Cogliati et al. (13), working with a cell-free system and in a novel Mφ culture system, demonstrated that in the presence of NO donors or inhibitors, the l-arginine-dependent NO pathway plays an important role in the murine Mφ immune response against P. marneffei (13).

On the other hand, NO does not appear to be involved in the fungicidal activity of either murine or human alveolar Mφs against other fungi such as A. fumigatus conidia (32, 41) and P. carinii (40).

In our model, the results revealed that when peritoneal BALB/c mice Mφs were used, rIFN-γ was able to induce fungicidal activity against P. brasiliensis conidia. Additionally, the inhibition of NO synthesis provoked by the addition of LNMMA, ARG, or AG was accompanied by reversion of the inhibition of fungal transformation. It is suggested that this phenomenon is mediated by production of nitric oxide and is dependent on the l-arginine:NO pathway. Whether lack of conidium-to-yeast transformation observed in vitro reflects the intracellular death of the infective propagules remains to be confirmed. Further studies are required to correlate death with the inability of the conidia to convert to the tissue yeast cell form.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Instituto Colombiano para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Tecnología, Francisco José de Caldas, COLCIENCIAS, Santafe de Bogotá-Colombia grant 2213-04-194-95, and the Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas (CIB), Medellín, Colombia. We especially thank the COLCIENCIAS Young Research Program, which enabled training of A. González in the CIB laboratories.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blasi E, Pitzurra I, Puliti M, Chimienti A R, Mazzolla R, Barluzzi R, Bistoni F. Differential susceptibility of yeast and hyphal forms of Candida albicans to macrophage-derived nitrogen-containing compounds. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1806–1809. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1806-1809.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bocca A L, Hayashi E E, Pinheiro A G, Furianetto A B, Campanelli A P, Cunha F Q, Figueiredo F. Treatment of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis-infected mice with a nitric oxide inhibitor prevents the failure of cell-mediated immune response. J Immunol. 1998;161:3056–3063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bocca A L, Silva M F, Silva C L, Cunha F Q, Figueiredo F. Macrophage expression of class II major histocompatibility complex gene products in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis-infected mice. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:280–287. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogdan C, Stenger S, Rollinghof M, Solbach W. Cytokine interactions in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Interleukin-4 synergizes with interferon-γ to activate murine macrophages for killing of Leishmania major amastigotes. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:327–333. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brummer E. Interaction of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis with host defense cells. In: Franco M, Silva Lacaz C, Restrepo Moreno A, del Negro G, editors. Paracoccidioidomycosis—1994. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calich V L G, Purchio A, Paula C R. A new fluorescent viability test for fungi cells. Mycopathologia. 1978;66:175–177. doi: 10.1007/BF00683967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calich V L G, Kipnis T L, Mariano M, Fava Neto C, Dias W D. The activation of the complement system by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis “in vitro”: its opsonic effect and possible significance for an in vivo model of infection. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1979;12:20–30. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(79)90108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cano L E, Brummer E, Stevens D, Restrepo A. Fate of conidia from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis after ingestion by resident macrophages or cytokine-treated macrophages. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2096–2100. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2096-2100.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cano L E, Gómez B, Brummer E, Restrepo A, Stevens D A. Inhibitory effect of deferoxamine or macrophage activation on transformation of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis conidia ingested by macrophages: reversal by holotransferrin. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1494–1496. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1494-1496.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cano L E, Kashino S S, Arruda C, André D, Xidieh C F, Singer-Vermes L M, Vaz C A C, Burger E, Calich V L G. Protective role of gamma interferon in experimental pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:800–806. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.800-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cano L E, González A. Papel del óxido nítrico en las micosis. Médicas UIS. 1998;12:299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark J A, Rockett K A, Couden W B. Possible central role of nitric oxide in conditions similar to cerebral malaria. Lancet. 1992;340:894–896. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cogliati M, Roverselli A, Boelaert J R, Taramelli D, Lombardi L, Viviani M A. Development of an in vitro macrophage system to assess Penicillium marneffei: growth and susceptibility to nitric oxide. Infect Immun. 1997;65:279–284. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.279-284.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corbett J A, McDaniel M L. Selective inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase by aminoguanidine. Methods Enzymol. 1996;268:398–408. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)68042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding A H, Nathan C F, Stuehr D J. Release of reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates from mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1988;141:2407–2412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drapier J C, Wietzerbin J, Hibbs J B., Jr Interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor induce the l-arginine-dependent cytotoxic effector mechanism in murine macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1587–1592. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franco M. Host parasite relationship in paracoccidioidomycosis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1987;25:5–18. doi: 10.1080/02681218780000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granger D L, Hibbs J B, Jr, Perfect J R, Durack D T. Metabolic fate of l-arginine in relation to microbiostatic capability of macrophages. J Clin Investig. 1990;85:264–273. doi: 10.1172/JCI114422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green S J, Nacy C A. Antimicrobial and immunopathologic effects of cytokine-induced nitric oxide synthesis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1993;6:383–396. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffith O W, Kilbourn R G. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors: amino acids. Methods Enzymol. 1996;268:375–392. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)68040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibbs J B, Jr, Taintor R R, Vavrin Z, Rachlin E M. Nitric oxide: a cytotoxic activated macrophage effector molecule. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;157:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hibbs J B, Jr, Vavrin Z, Taintor R R. l-Arginine is required for expression of the activated macrophage effector mechanism causing selective metabolic inhibition in target cells. J Immunol. 1987;138:550–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James S L, Glaven J. Macrophage citotoxicity against schistosomula of Schistosoma mansoni involved arginine-dependent production of rective nitrogen intermediates. J Immunol. 1989;143:4208–4212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorens P G, Boelaert J R, Halloy V, Zamora R, Schneider Y J, Herman A G. Human and rat macrophages mediate fungistatic activity against Rhizopus species differently: in vitro and ex vivo studies. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4489–4494. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4489-4494.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashino S S, Fazioli R A, Moscardi-Bacchi M, Franco M, Singer-Vermes L M, Burger E, Calich V L G. Effect of macrophage blockade on the resistance of inbred mice to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection. Mycopathologia. 1995;130:131–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01103095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kudeken N, Kawakami K, Saito A. Different susceptibilities of yeast and conidia of Penicillium marneffei to nitric oxide (NO)-mediated fungicidal activity of murine macrophage. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:287–293. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane T E, Otero G C, Wa-Hsieh B, Howard D H. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase by stimulated macrophages correlates with their antihistoplasma activity. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1940–1945. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1478-1479.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S C, Dickson D W, Brosnan C F, Casadevall A. Human astrocytes inhibit Cryptococcus neoformans growth by a nitric oxide-mediated mechanism. J Exp Med. 1994;180:365–369. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liew F Y, Millott S, Parkinson C, Palmer R M J, Moncada S. Macrophage killing of Leishmania parasite “in vivo” is mediated by nitric oxide from l-arginine. J Immunol. 1990;144:4794–4797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacMicking J, Xie Q, Nathan C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mauël J, Ransijn A, Buchmüller-Rouiller Y. Killing of Leishmania parasites in activated murine macrophages is based on an l-arginine-dependent process that produces nitrogen derivates. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:73–82. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michaliszyn E, Sènèchal S, Martel P, Repentigny L. Lack of involvement of nitric oxide in killing of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by pulmonary alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2075–2078. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2075-2078.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moscardi-Bacchi M, Brummer E, Stevens D A. Support of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis multiplication by human monocytes or macrophages: inhibition by activated phagocytes. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:159–164. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-3-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz-Fernandez M A, Fernandez M A, Fresno M. Synergism between tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ on macrophage activation for the killing of Trypanosoma cruzi through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:301–307. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura L T, Wo-Hsieh B A, Howard D H. Recombinant murine gamma interferon stimulates macrophages of the RAW cell line to inhibit intracellular growth of Histoplasma capsulatum. Infect Immun. 1994;62:680–684. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.680-684.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nathan C F. Secretory products of macrophages. J Clin Investig. 1987;79:319–326. doi: 10.1172/JCI112815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norris K A, Schirimpf J E, Flynn J L, Morris S M., Jr Enhancement of macrophages microbicidal activity: supplemental arginine and citrulline augment nitric oxide production in murine peritoneal macrophages and promote intracellular killing of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2793–2796. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2793-2796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Restrepo A, Salazar M E, Cano L E, Patiño M M. A technique to collect and dislodge conidia produced by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis mycelial form. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.San Blas G. Paracoccidioidomycosis and its etiologic agent Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1993;31:99–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shellito J E, Kolls J K, Olariu R, Beck J M. Nitric oxide and host defense against Pneumocystis carinii infection in a mouse model. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:432–439. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taramelli D, Malabarba M G, Sala G, Basilico N, Coccuzza G. Production of cytokines by alveolar and peritoneal macrophages stimulated by Aspergillus fumigatus conidia or hyphae. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor-Robinson A W, Phillips R S, Severn A, Moncada S, Liew F Y. The role of TH1 and TH2 cells in a rodent malaria infection. Science. 1993;260:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.8100366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vázquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Balish E. Nitric oxide production does not directly increase macrophage candidacidal activity. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1142–1144. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1142-1144.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vázquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Balish E. Peroxynitrite contributes to the candidacidal activity of nitric oxide-producing macrophages. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3127–3133. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3127-3133.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang T, Kawakami K, Oureshi M H, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Saito A. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) and IL-18 synergistically induce the fungicidal activity of murine peritoneal exudate cells against Cryptococcus neoformans through production of gamma interferon by natural killer cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3594–3599. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3594-3599.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]