Abstract

Purpose

No single pharmacy in an urban zip code is consistently the least expensive across medications. If medication prices change differently across pharmacies, patients and clinicians will face challenges accessing affordable medications when refilling medications. This is especially pertinent to people with cancer with multiple fills of supportive care medications over time. We evaluated if the lowest-priced pharmacy for a formulation remains the lowest-priced over time.

Methods

We compiled generic medications used to manage nausea/vomiting (14 formulations) and anorexia/cachexia (12 formulations). We extracted discounted prices in October 2021 and again in March 2022 for a typical fill at 8 pharmacies in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA (zip code 55,414) using GoodRx.com. We examined how prices changed across formulations and pharmacies over time.

Results

Data were available for all 208 possible pharmacy-formulation combinations (8 pharmacies × 26 formulations). For 172 (83%) of the 208 pharmacy-formulation combinations, the March 2022 price was within 20% of the October 2021 price. Across pharmacy-formulation combinations, the price change over time ranged from − 76 to + 292%. For 12 (46%) of the 26 formulations, at least one pharmacy with the lowest price in October 2021 no longer was the least costly in March 2022. For one formulation (dronabinol tablets), the least expensive pharmacy became the most expensive, with an absolute and relative price increase of a fill of $22 and 85%.

Conclusion

For almost half of formulations studied, at least one pharmacy with the lowest price was no longer the least costly a few months later. The lowest price for a formulation (across pharmacies) could also change considerably. Thus, even if a patient accesses the least expensive pharmacy for a medication, they may need to re-check prices across all pharmacies with each subsequent fill to access the lowest prices. In addition to safety concerns, directing medications to and accessing medications at multiple pharmacies can add time and logistic toxicity to patients with cancer, their care partners, prescribers, and pharmacy teams.

Keywords: Cancer, Financial toxicity, Time toxicity, Logistic toxicity, Lowest cost pharmacy, Drug prices

Introduction

Facing high medication costs, people with cancer, their care partners, and the clinical team sometimes explore less costly sources of medications [1–4]. This is particularly true for supportive care medications; drugs used to prevent and treat symptoms of cancer or side effects of its treatment [5]. Supportive care medications are often available at multiple local pharmacies (within a zip code), with transparent out-of-pocket costs available through drug price comparison websites [1, 5].

We have previously demonstrated that no single pharmacy in an urban zip code consistently offered the lowest discounted price for 26 generic formulations of medications used to treat nausea/vomiting and anorexia/cachexia [1]. “Shopping around’’ for the least expensive source of each medication by visiting multiple pharmacies can save direct out-of-pocket costs in the moment, but can add time and logistic toxicity for patients and care partners [1, 2, 6–8]. Even in an urban area with a high density of pharmacies, a patient seeking the least expensive source of five common supportive care medications may have to visit five different pharmacies to get the lowest price on all medications [1]. In one example, just the driving time (without accounting for traffic or time spent parking, waiting in line, medication processing, and getting back to the car) was over an hour, with > 30 miles distance covered [1]. The potential cost savings in this example were approximately 20% (saving $20 on $100), but patients may face more difficult trade-offs between financial, time, and logistic toxicity when cost differences and time burdens are more significant.

Patients with cancer may require multiple fills of supportive care medications over months or years as they manage the disease. Even if patients or their care team members identify the least expensive source of a medication, and decide to pursue it for the first fill, a complicating factor is that medication prices are dynamic, changing with time and across pharmacies. This potentially creates additional complexity for patients and clinicians even if they identify the least expensive pharmacy for a medication at the outset. A key question is whether the lowest cost pharmacy for a medication formulation remains the lowest-cost over time.

Methods

We included 14 generic formulations for medications used to treat nausea/vomiting and 12 used to treat anorexia/cachexia. We selected these symptoms since they are common, clinically relevant, and several approved and off-label medications are available and used to treat them. Detailed methods are available in prior work [1, 2]. Briefly, we used the GoodRx website — a nationally available medication price comparison tool that provides real-time information on discounted cash-pay medication prices available to consumers at participating pharmacies in (or near) their zip code — to calculate prices for a typical fill for each product across the 8 unique pharmacies in the region [9]. These pharmacies included large and small chain pharmacies and independent pharmacies [1, 2]. In prior work, we had included 9 pharmacies, but more recently, there are no active Kroger pharmacy locations near the zip code under the study. Thus, we restricted analyses to 8 pharmacies (excluding Kroger). GoodRx reports an “average retail price”, and a discounted “lowest price with coupon” at individual pharmacies—a best-case scenario of out-of-pocket costs for a patient without or opting not to use prescription drug coverage. We extracted discount prices for each formulation at each pharmacy at two time points (in October 2021 and March 2022) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA (zip code 55414, population approximately 400,000). Minneapolis is an urban area with 19% of families living below the poverty rate [10]. We examined how prices changed across formulations and pharmacies over time.

Because we used publicly available data, and this was not human subjects research, in accordance with 45 CFR §46.102(f), we did not submit this study to an institutional review board or require informed consent procedures. We used Microsoft Excel v16.0 (Redmond, WA, USA) and GraphPad Prism v7.0 (San Diego, CA, USA) for analyses.

Results

Complete pricing data at both time points were available for all 208 pharmacy-formulation combinations (26 formulations × 8 pharmacies).

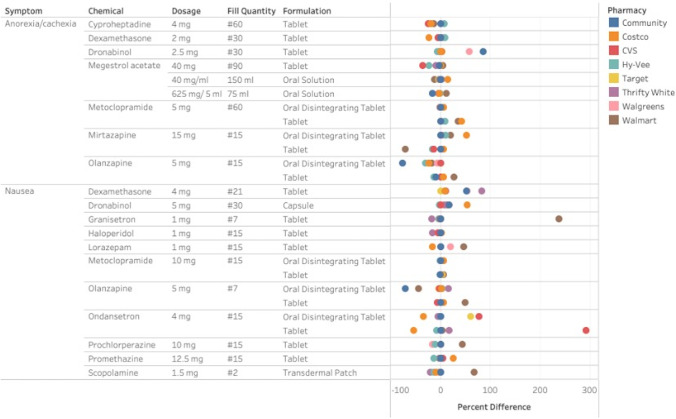

For 142 (68%) of the 208 pharmacy-formulation combinations, the price in March 2022 was within 10% of the price in October 2021 (Fig. 1). For 30 (14%) of the pharmacy-formulation combinations, the price in March 2022 was within 11–20% of the price in October 2021. Thus, 172 (83%) of pharmacy-formulation combinations had a price change of < 20%.

Fig. 1.

Percent change in GoodRx generic discount prices used to manage anorexia/cachexia and nausea/vomiting from October 2021 to March 2022 (Each dot represents a percent difference for a given formulation at a pharmacy, # denotes fill count)

The range of price changes for a pharmacy-formulation combination from October 2021 to March 2022 was − 76 to + 292%. For example, the price for a 7-count fill of 1 mg granisetron tablets increased by 238% (from $79 to $268) at one pharmacy, and the price for a 15-count fill of 4 mg ondansetron tablets increased by 292% (from $14 to $53) at another pharmacy. For 4 pharmacy-formulation combinations, the price decreased by more than 50%. For example, the price of a 15-count of 5 mg olanzapine oral disintegrating tablets decreased by 76% (from $63 to $15) at one pharmacy (Fig. 1).

For a given formulation, the least expensive pharmacy in October 2021 was no longer the least expensive pharmacy in March 2022 for 7 of the 26 studied formulations (27%) (Fig. 2). Additionally, for 5 of the remaining 19 formulations, multiple pharmacies shared the lowest cost in October 2021, but only one of these pharmacies retained the lowest price in March 2022. As an example, the lowest cost in October 2021 for a 30-count of 5 mg dronabinol capsules was $58, and this price was available at Costco, Hy-Vee, and Thrifty White. In March 2022, Hy-Vee still had the lowest price (now $57), but prices had increased to $89 and $63 at Costco and Thrifty White, respectively. Consequently, for 12 of the 26 studied formulations (46%) at least one pharmacy with the lowest cost in October 2021 no longer were the least expensive in March 2022. For one formulation (30-count fill of 2.5 mg dronabinol tablets), the least expensive pharmacy in October 2021 was the most expensive in March 2022, with an absolute and relative price increase of $22 and 85%, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Standardized discounted prices for drugs used to manage anorexia/cachexia and nausea/vomiting in March 2022 (Standardized March 2022 prices are equal to the March 2022 price divided by the October 2021 price across formulations and pharmacies. Color indicates whether the lowest March 2022 price is at the same pharmacy as the lowest October 2021 price. “Multiple” means that multiple pharmacies had the lowest price in October 2021 but they did not all retain the lowest price in March 2022).< 1.0 means March 2022 price is lower, and > 1.0 means March 2022 prices are higher than prices in October 2021

For a given formulation, the least expensive price (regardless of the pharmacy) in March 2022 was > 20% different (increased or decreased) than the October 2021 price for 5 (19%) formulations (Fig. 2). The difference in the least expensive price of the 26 formulations (irrespective of pharmacy) ranged from − 50 to + 35%. For example, the lowest costs for a 30-count of 2.5 mg dronabinol tablets and a 15-count of 15 mg mirtazapine oral disintegrating tablets were 25% and 35% higher in March 2022, compared to October 2021. For a 15-count of 4 mg ondansetron tablets, the least expensive price in March 2022 is 50% less than in October 2021. Changes in the least expensive price over time differed for formulations for the same medication. For example, both metoclopramide and olanzapine are available as tablet and oral disintegrating tablets; prices of oral disintegrating tablets increased by 0–4%, while prices of tablets increased by 28–36% over time.

We also assessed the financial impacts of remaining at the lowest cost pharmacy when it was no longer the lowest cost pharmacy (n = 12) (Table 1). For the majority of these pharmacy-formulations, the “added cost” of not switching to the new lowest cost pharmacy (difference between the October 2021 least expensive pharmacy’s price in March 2022 minus the lowest available price in March 2022) is relatively small: < $5, for 10 of the 12. In some instances, the “added cost” of not switching is higher. For example, Costco offered the lowest cost for a 30-count of 5 mg dronabinol capsules in October 2021, but a patient who still filled this prescription at Costco in March 2022 would pay $32 more than the lowest price in March 2022 ($89 versus $57).

Table 1.

Cost of remaining at the October 2021 least expensive pharmacy for formulations when the least expensive pharmacy changes in March 2022

| Symptom | Chemical | Dosage | Formulation | Fill Quantity | Name of least expensive pharmacy in October 2021 | Price at least expensive pharmacy in October 2021 (US Dollars) |

Price at the same pharmacy in March 2022 (US Dollars) |

Price at a different least expensive pharmacy in March 2022 (US Dollars) |

Cost of remaining at the original pharmacy (US Dollars) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anorexia/cachexia | Cyproheptadine | 4 mg | Tablet | #60 | Hy-Vee | 12.2 | 13.1 | 11.7 | 1.4 |

| Dexamethasone | 2 mg | Tablet | #30 | Walgreens | 12.0 | 12.8 | 12.0 | 0.8 | |

| Community | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | |||||

| Dronabinol | 2.5 mg | Tablet | #30 | Community | 25.5 | 47.1 | 31.8 | 15.3 | |

| Megestrol acetate | 40 mg/ml | Oral Solution | 150 ml | Costco | 17.4 | 19.8 | 17.5 | 2.3 | |

| Megestrol acetate | 40 mg | Tablet | #90 | Thrifty White | 22.8 | 20.6 | 19.6 | 1.0 | |

| Mirtazapine | 15 mg | Oral Disintegrating Tablet | #15 | Costco | 10.2 | 15.4 | 13.8 | 1.6 | |

| Mirtazapine | 15 mg | Tablet | #15 | Thrifty White | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 0.9 | |

| Olanzapine | 5 mg | Oral Disintegrating Tablet | #15 | Hy-Vee | 14.6 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 0.0 | |

| Thrifty White | 14.6 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 1.0 | |||||

| Nausea | Dexamethasone | 4 mg | Tablet | #21 | Costco | 6.9 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 0.0 |

| Hy-Vee | 6.9 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 0.0 | |||||

| Thrifty White | 6.9 | 12.5 | 7.5 | 5.0 | |||||

| Dronabinol | 5 mg | Capsule | #30 | Costco | 58.3 | 89.0 | 56.7 | 32.3 | |

| Hy-Vee | 58.3 | 56.7 | 56.7 | 0.0 | |||||

| Thrifty White | 58.3 | 62.6 | 56.7 | 5.9 | |||||

| Olanzapine | 5 mg | Oral Disintegrating Tablet | #7 | Hy-Vee | 8.4 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 0.0 | |

| Thrifty White | 8.4 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 1.0 | |||||

| Ondansetron | 4 mg | Tablet | #15 | Thrifty White | 6.9 | 8.1 | 3.5 | 4.6 |

Discussion

In this study of supportive care medication prices at different pharmacies within an urban zip code, we found that (1) for almost half the formulations, at least one pharmacy with the lowest price in October 2021 no longer was the least expensive in March 2022, and (2) the lowest possible price for a given formulation across pharmacies changed considerably over a few months.

In a prior work, we highlighted that no single pharmacy in an urban zip code consistently offers the lowest price for the full range of medications commonly used to treat two classes of cancer-related symptoms [1]. Seeking the least expensive source of medications across multiple pharmacies can be time-consuming, expensive, and frustrating. This work highlights that even if clinicians and patients identify and pursue the least expensive pharmacy for a medication at a particular point in time, re-filling the same medication at the same pharmacy may not remain the “best-deal”. Patients “planning” out-of-pocket costs for later fills of the same medication — especially people with fixed income — should be cautioned that it is unlikely that they will pay a similar amount as during the first fill, whether they fill at the same or at a different least expensive pharmacy.

This work has important implications for all stakeholders. To guarantee that the patient accesses the lowest price possible in subsequent fills, a person or process would have to re-check prices across pharmacies prior to each fill, transmit prescriptions to that pharmacy, and ensure that a patient could pick up the medication in a safe and timely manner. This entire process can add significant additional time and logistic toxicity for patients and care partners, and also prescribers and pharmacists [2, 6, 8, 11]. This is especially pertinent with record rates of clinician burnout [12–14], with a major contributor being administrative burdens of navigating supportive care medications [15]. Additional issues with using multiple pharmacies are decreased adherence [16], and safety concerns — prescription duplications and drug-drug interactions, especially if each individual pharmacy’s staff assumes that another pharmacy serves as the primary pharmacy for the patient, and is primarily responsible for checks. A 2019 survey of over 10,000 U.S. older adults revealed that nearly 1 in 5 reported trouble getting to places like the doctor’s office [17]. Traveling to multiple pharmacies may magnify these burdens, with the additional aspect of people (especially immunocompromised people with cancer and their care partners) trying to minimize exposures in the COVID era. Further, filling opioids — essential cancer supportive care medications — at multiple pharmacies can be flagged as a sign of misuse, rather than an attempt at affordability [9, 18]. For patients and care partners, coordinating pickup of medications across pharmacies can be extremely burdensome, particularly if these pharmacy locations are not located near one another. This could lead to additional patient-requested medication transfers from one pharmacy to the next, need for coordination with the prescriber’s office, or potential wait times if patient prescriptions are not transferred quickly. With pharmacies facing increasing workload and staffing shortages throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, patients may be exposed to delays up to or exceeding the 1–4 days pre-pandemic anticipated turn-around time [19, 20]. At a time when mitigation of financial toxicity is receiving much attention, this work highlights the complexity of designing and implementing meaningful pharmaceutical interventions, even when efforts to decrease out-of-pocket costs are well intentioned. Oncology clinicians have limited time, training, and resources to address out-of-pocket medication costs for patients, especially at the point of prescribing, since these costs can be opaque and unpredictable [21]. There is a critical need for systems-level changes to allow oncology clinicians to help patients access affordable medications. For example, electronic medical record tools can provide clinicians with the price of medications and their suitable alternatives at different pharmacies at the time of ordering (e.g., real-time benefit tools) [21, 22]. We have previously demonstrated how prices of supportive care medications can vary dramatically by the dose/formulation; for example, the cost of a 37.5 mcg/h transdermal fentanyl patch is much higher than the combined cost of 25 and 12 mcg/h patches, and is even higher than a 50 mcg/h patch [23]. Such information can help guide prescribing when clinically suitable. Of course, in an ideal world, drug prices would be more stable, logical, and affordable for patients. Implementing real-time benefit tools across pharmacies would require the cooperation of multiple stakeholders: electronic medical record vendors, payers, pharmacies etc. [21].

This work has limitations [1]. We only explored prices for formulations for two cancer-associated symptoms. We evaluated only discounted prices (not retail prices or average wholesale prices) in a single urban zip code. When availing discounted prices using coupons, patients cannot use prescription drug coverage (if any), but given high rates of underinsurance and uninsurance these data are widely applicable. Additionally, given that all of the studied formulations were generic, the cash pay (the discounted price) may be lesser than the cost-sharing requirement with insurance. Thus, these data may also apply to people with insurance who face deductibles or higher copayments or coinsurance for filling prescriptions under their health plans. For people with insurance opting to use their insurance, the complexity of pharmacy shopping may be increased, since exact cost-sharing responsibility is more opaque. However, insured people are often also locked in to only using a specific network of pharmacies, since plans typically have preferred pharmacy contracts. We did not inflation-adjust prices since the data points were just 5 months apart — data suggest cash prices of generic drugs may be rising despite decreased costs earlier in the supply chain and competition [24]. Generic drug products had a median list price increase of 1% in January 2022, with 82% of generic products experiencing any price increase [25]. Drug price changes might also relate to drug shortages, which can influence pricing/demand; however, none of the specific formulations included in this study (or similar symptom control drugs) had reported shortages during the study period. For reference, the FDA database reported a shortage of haloperidol tablets and scopolamine patches in 2018–2019 [26].

In conclusion, we demonstrate that even if a patient identifies the least expensive pharmacy for a medication, the pharmacy may not remain the least expensive option over time. Patients, care partners, prescribers, and pharmacists face significant time and logistic toxicity in playing “catch-up” with an imperfect system. Novel processes are needed to ensure that patients have access to the most affordable medications without exposing them and their care partners to time and logistic toxicity.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Andrew Etteldorf and Arjun Gupta. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Andrew Etteldorf and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Etteldorf A, Rotolo S, Sedhom R et al (2022) Finding the lowest-cost pharmacy for cancer supportive care medications: not so easy. JCO Oncol Pract 18(8):e1342–e1349. 10.1200/OP.22.00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Gupta A et al (2022) Time-related burdens of cancer care. JCO Oncol Pract 18(4):245–246. 10.1200/OP.21.00662 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Desai N, et al. Estimated out-of-pocket costs for cancer-directed and supportive care medications for older adults with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2022;13(5):754–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sedhom R, Chino F, Gupta A. Financial toxicity and cancer care #409. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(3):453–454. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta A et al (2022) Financial burden of drugs prescribed for cancer-associated symptoms. JCO Oncol Pract 18(2):140–147. 10.1200/OP.21.00466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Gupta AEA (2022) Eisenhauer, and C.M. Booth, The time toxicity of cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol 40(15):1611–1615. 10.1200/JCO.21.02810 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Gill LL (2018) Shop around for lower drug prices. Consumer Reports. https://www.consumerreports.org/drug-prices/shop-around-for-better-drug-prices/

- 8.Sedhom R, Samaan A, Gupta A. Caregiver Burden #419. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(8):1246–1247. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2021.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua KP, et al. Assessment of prescriber and pharmacy shopping among the family members of patients prescribed opioids. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193673. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Opportunity Atlas. Available at: https://www.opportunityatlas.org/. Accessed May 22, 2022.

- 11.Banerjee R, George M, Gupta A. Maximizing home time for persons with cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(9):513–516. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golbach AP et al (2022) Evaluation of burnout in a national sample of hematology-oncology pharmacists. JCO Oncol Pract 18(8):e1278–e1288. 10.1200/OP.21.00471 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Singh S, et al. Prevalence and workplace drivers of burnout in cancer care physicians in Ontario Canada. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(1):e60–e71. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tetzlaff ED, et al. Changes in burnout among oncology physician assistants between 2015 and 2019. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(1):e47–e59. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haque W, et al. Payer-imposed quantity limits for antiemetics: everybody hurts. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(5):313–317. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcum ZA, et al. Effect of multiple pharmacy use on medication adherence and drug-drug interactions in older adults with Medicare Part D. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(2):244–252. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganguli I et al (2022) Which Medicare beneficiaries have trouble getting places like the doctor's office, and how do they do it? J Gen Intern Med. 10.1007/s11606-022-07615-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.NCQA. Use of opioids from multiple providers (UOP). Available at:https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/use-of-opioids-from-multiple-providers/#:~:text=Evidence%20suggests%20that%20people%20who,for%20opioid%20overuse%20and%20misuse. Accessed May 22, 2022

- 19.How to transfer a prescription to another pharmacy. ScriptSaveWellRx. Publised July 31, 2019. Available at:https://www.wellrx.com/news/how-to-transfer-a-prescription-to-another-pharmacy/. Accessed June 10, 2022.

- 20.Bookwalter CM. Challenges in community pharmacy during COVID-19: the perfect storm for personnel burnout. US Pharxmacist. Published May 14, 2021. Available at:https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/challenges-in-community-pharmacy-during-covid19-the-perfect-storm-for-personnel-burnout. Accessed June 10, 2022

- 21.Giap F, Chino F, Gupta A. Systems-level changes to address financial toxicity in cancer care. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(4):310–311. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everson J, Frisse ME, Dusetzina SB. Real-time benefit tools for drug prices. JAMA. 2019;322(24):2383–2384. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussaini SMQ, et al. Intermediate strengths and inflated prices: the story of transdermal fentanyl patches. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(9):1335–1337. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2022.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teasdale B, et al. Trends and determinants of retail prescription drug costs. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(3):548–556. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schondelmeyer SW. Prescription drug price changes in January 2022. Published February 9, 2022. Available at:https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Prescription%20Drug%20Price%20Increases%20in%20January%202022%202022-02-24.pdf, Accessed June 10, 2022

- 26.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug shortages. Available at:https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/drug-shortages. Accessed September 9, 2022

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.