Abstract

Aptamers are single-stranded oligonucleotides (RNA or DNA) with a typical length between 25 and 100 nucleotides which fold into three-dimensional structures capable of binding to target molecules. Specific aptamers can be isolated against a large variety of targets through efficient and relatively cheap methods, and they demonstrate target-binding affinities that sometimes surpass those of antibodies. Consequently, interest in aptamers has surged over the past three decades, and their application has shown promise in advancing knowledge in target analysis, designing therapeutic interventions, and bioengineering. With emphasis on their therapeutic applications, aptamers are emerging as a new innovative class of therapeutic agents with promising biochemical and biological properties. Aptamers have the potential of providing a feasible alternative to antibody- and small-molecule-based therapeutics given their binding specificity, stability, low toxicity, and apparent non-immunogenicity. This Review examines the general properties of aptamers and aptamer–protein interactions that help to understand their binding characteristics and make them important therapeutic candidates.

Keywords: aptamer, aptamer−protein interaction, aptamer folding, kinase inhibitor, aptamer therapeutics, therapeutic modality

1. Introduction

“The RNA world” hypothesis in the early 1980s,1 and the earlier discovery of the catalytic activity of RNA, kindled an interest in nucleic acids and their previously underestimated potential. This opened up a new field of therapeutics centered on nucleic acids as opposed to proteins, paving the way to numerous types of nucleic acid-based drugs. A major class of this group of therapeutics comprises short (25–100 nucleotides) synthetic single-stranded oligonucleotide (RNA or DNA) ligands called aptamers, which have complex three-dimensional structures.2,3 The study of aptamers is an interdisciplinary subject at the interface of chemistry and biology. This field has matured considerably over the years, and now, hundreds of laboratories worldwide are engaged in aptamer research.4 A simple search for the phrase “aptamer or aptamers” using the MEDLINE database through PubMed returns 17 634 reports collectively from 1990 until July of 2022.

Therapeutic applications of aptamers stem from their ability to form specific contacts with target proteins involving functional groups on both molecules. An aptamer conceals a large portion of the target protein and, thereby, blocks the protein’s interaction with its substrate or with other molecules. In other words, it functions as an antagonist that eventually leads to inhibition of protein activity.5 Moreover, the specificity of aptamer–target recognition has allowed the use of aptamers in delivering therapeutic cargo to target disease cells in a selective manner, conceivably reducing off-target effects. In this Review, we discuss the general properties of aptamers and their interactions with proteins, we present a basis for therapeutic potential of aptamers, we give examples of aptamers targeting cell surface protein kinase receptors and intracellular protein kinases, and we finish with concluding remarks and the prospects for aptamer therapeutics.

2. The Origins of Aptamers

Tuerk and Gold, as well as Ellington and Szostak, two groups of researchers working almost simultaneously, first reported aptamers in 1990. They independently succeeded in developing the same general in vitro selection strategy for isolating RNA ligands with progressively improved affinity from a starting population of random RNA sequences.2,3 Craig Tuerk and Larry Gold published their results in Science, and they were the first to refer to this production procedure as “Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment”, abbreviated as SELEX.2

The high-affinity ligands resulting from SELEX were coined “aptamers” by Andrew Ellington and Jack Szostak, and first appeared in their Nature paper.3 The word aptamer is a chimeric term combining the Latin “aptus” (to fit) and the Greek “meros” (part or piece). As Larry Gold said: “Both words have stuck; one does SELEX and gets aptamers.” 6 Today, the development of these “anti-shape nucleic acid pharmaceuticals” is a thriving area of study that has been gaining momentum ever since its early days.7

3. Aptamer Selection (SELEX)

Aptamers are conventionally produced through an in vitro selection process coined SELEX that was first described over 25 years ago. The first studies on aptamer selection involved mostly RNAs, based on the assumption that RNA can form more diverse three-dimensional structures than DNA, which is believed to facilitate higher affinity to the target. However, RNA SELEX is more complex than DNA SELEX owing to the fact that additional in vitro transcription steps are needed before and after each PCR amplification step.8 Analysis of a great number of different aptamers actually showed that ssDNA aptamers do not differ by affinity and specificity from RNA ligands. One advantage of RNA aptamers, though, is that they can be expressed inside cells, which may be of great importance for in vivo use.9

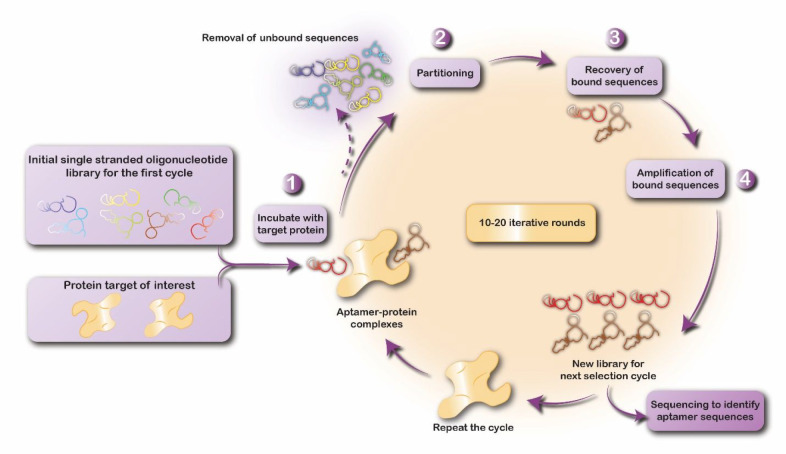

The basic outline of SELEX is depicted in Figure 1. The process starts with a collection of 1014–1015 different single-stranded nucleic acids (RNA, DNA, or modified RNA) referred to as the initial oligonucleotide pool (IOP). The conventional IOP consists of a central 30–50-nucleotide-long randomized region that provides conformational and structural diversity,10 flanked by fixed sequences necessary for PCR amplification and in vitro transcription.11 Modified short DNA and RNA libraries have been developed for primer-free and minimal primer selection.12−14

Figure 1.

An overview of the conventional protein-based SELEX process.

In order to isolate ligands that exhibit high binding affinity and specificity to a particular protein, the IOP is incubated with the target protein to drive this selective process. Oligonucleotides that are able to bind to the protein are separated from unbound or weakly bound sequences using different partitioning techniques. The bound nucleic acid sequences are then eluted from the protein and reverse-transcribed in the case of RNA-based oligonucleotides, and then amplified using PCR. The result at this point is a pool enriched in sequences that bind to the target protein and one that contains a more homogeneous mix of sequences relative to the IOP. Before the next cycle of selection can begin, the oligonucleotides in the pool are transcribed in vitro (if they are RNA-based oligonucleotides), or they are immediately denatured to separate their strands (in the case of DNA oligonucleotides).15 These steps are repeated over multiple rounds, typically 6–18 cycles, with alternating selection and amplification to achieve a final dominant population of target-binding sequences.16 The key to generate aptamers with high affinities to their targets lies in creating increasingly demanding conditions for binding in the latter rounds of SELEX. This includes strategies such as decreasing the concentration of the target protein, using effective competitors, or increasing washing times.17

Usually, the selection process results in a large number of sequences that are cloned, sequenced, and aligned to identify and group similar ones. Ideally, all the resulting sequences are evaluated to choose the most promising aptamers in terms of binding properties such as affinity, specificity, and cross-reactivity.11 However, this is considered to be the most expensive and time-consuming stage of the production process.8 Preselection (negative SELEX) and counter-SELEX (subtractive SELEX) can be applied between certain rounds of SELEX to respectively remove sequences that bind to the partitioning matrix used to immobilize the target molecules or those that bind to molecules similar to the actual target.18 Post-SELEX modifications can also be applied to improve affinity, specificity, stability, pharmacokinetics, or bioavailability of aptamers.18

Many important improvements on the original conventional SELEX procedure have been introduced to enhance the effectiveness of selection. These modifications have helped reduce the time and target concentration necessary for aptamer generation and, at the same time, support high-throughput isolation of aptamers of high affinity and specificity.19−21 Automatic aptamer selection has also been introduced, and it allows selection of aptamers in parallel to a large number of different targets.9 Other methods have been developed that enable the use of targets present in a more natural condition, such as molecules in human plasma or proteins on cell surfaces.17 Updates on SELEX technologies that target membrane proteins have been well reviewed by Takahashi.22 For instance, live cell-based SELEX (or cell-SELEX) employs whole living cells as the selection target with surface antigens presented in their natural form.23 Cell-internalization SELEX, pioneered by the Giangrande group, builds on cell-SELEX and aims to isolate aptamers that rapidly get internalized into target cells.24 Later alternative methods attempted to improve on this by treating the target cells with a cocktail of RNases or proteinase K to achieve the same end result.25,26

4. General Properties of Aptamers in Comparison to Antibodies

The complex tertiary structures of aptamers resemble the three-dimensional forms of globular proteins in many respects more closely than they resemble other nucleic acids.27 In fact, aptamers are considered nucleotide analogs of antibodies, and Craig Tuerk had described them as “nucleic acid antibodies” before the word “aptamer” became widely used.28

Thousands of aptamers have been developed over the years against various types of targets, including coagulation factors,29 growth factors,30 hormones,31 antibodies,32 neuropeptides,33 small metal ions,34 viruses,35 bacteria,36 whole living cells,37 toxins,38 proteins,39 and biomarkers, and even targets within live animals.40 In addition, aptamers can be selected toward toxic and poorly immunogenic targets, whereas antibodies produced in vivo cannot be generated to such targets.40 Indeed, a remarkable aspect of aptamers is that, in principle, they can be generated for selective binding to virtually any target.8

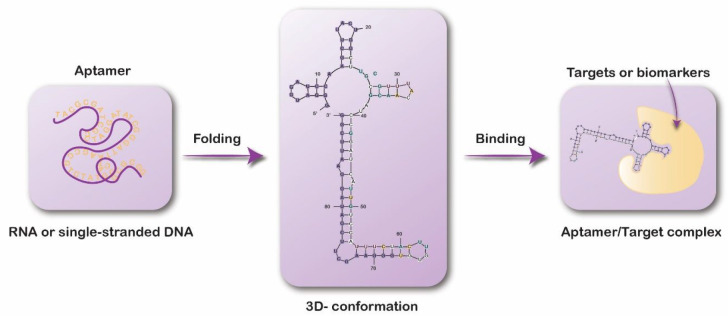

As shown in Figure 2, the complex tertiary structures of aptamers have extended surface areas for target recognition, allowing for the establishment of tight interactions.41 In fact, aptamer binding demonstrates kinetics comparable to that of antibodies, with dissociation constants (KD) generally in the range of several micro- to picomolar.42

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of an aptamer–target interaction.

Aptamers also bind to their targets with exceptional specificity, similar to antibodies.43 For example, aptamers were able to distinguish between highly similar conformational isoforms of protein kinase C,44 or even between proteins that differ by a single amino acid substitution.45 In addition, aptamers can be selected to bind and modulate a specific phosphorylated amino acid residue on a protein without affecting a neighboring phosphorylated residue on the same protein.46

Aptamers also have a number of advantages over antibodies that make them cheaper to manufacture commercially and have wider application. One such advantage is that they can be synthesized entirely in vitro without the need for cells, in contrast to antibodies that require an in vivo environment for production.47 In addition, aptamers are more amenable to targeted modification after production, and they can be prepared with high reproducibility, purity, and extremely low variability between batches.47,48 Being nucleic acids means that they are much more stable than proteins and they can be stored long-term at ambient temperature at a wide range of pH and ionic conditions without losing their functionality.49 Unlike antibodies, aptamer denaturation is reversible, and they can refold into their functional structure even after multiple freeze–thaw cycles.49

Moreover, antibodies are generally applicable only under physiological conditions because of their sensitivity to degradation, aggregation, modification, and denaturation. On the other hand, it is possible to develop aptamers that can function in non-physiological conditions. For example, a DNA aptamer selected against ochratoxin-A mycotoxin performed well in the presence of 20% methanol in an aqueous buffer.50

The size of aptamers usually ranges between 5 and 30 kDa, which is equivalent to approximately a tenth of the size of monoclonal antibodies. This smaller size means they are better able to penetrate biological compartments and tissues compared to antibodies and antibody fragments,51 giving them access to otherwise sterically inaccessible protein domains.52 Aptamers have also been found to cause low or no immunogenicity in standard assays in comparison to antibodies. Indeed, no specific humoral response against modified RNA aptamers has been successfully generated despite a resulting specific response to a variety of adjuvants used in combination with the same aptamers.15

In the context of aptamer use in clinical trials, the only recorded incidence of an immune response elicited following aptamer administration has probably been due to generation of antibodies against the conjugated polyethylene glycol (PEG), which can limit the therapeutic efficacy of PEGylated aptamer.53,54 Thus, the wide-ranging targets of aptamers combined with their small size, high stability, and low immunogenicity make them ideal candidates for diagnostic and therapeutic applications.10

5. Aptamer Binding Characteristics: Aptamer–Protein Interaction

5.1. Aptamer Folding and Structure

Lawrence et al. (2013) studied the folding kinetics of a 38-base DNA aptamer and revealed that it folds through a concerted, approximately two-state, millisecond-scale process lacking well-populated intermediates.55 The single-stranded nucleic acid sequence of aptamers typically can fold into various secondary structures such as stem, loop, bulge, pseudoknot, G-quadruplex, and kissing hairpin.56 These secondary structures in turn fold into three-dimensional compact structures, overcoming electrostatic repulsion through the employment of π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding between the nucleobases.57

RNA aptamers are believed to have greater diversity and complexity in terms of their three-dimensional structures and possible conformations compared to DNA aptamers.58,59 It may be natural to assume that RNA aptamer folding is determined by metal cations since the backbone of aptamer molecules is negatively charged. Metal cations do indeed play an important role in forming and stabilizing RNA structural motifs through occupying specific binding pockets.60 The aromatic bases and backbone of the aptamer constitute the main sites of interaction with metal cations. Physiological concentrations of monovalent ions (∼150 mM) may promote secondary structure formation, whereas divalent ions (Mg2+ ions) contribute to the stabilization of RNA tertiary structure.61

5.2. Aptamer–Protein Interaction

The final three-dimensional conformations of aptamers recognize their targets with high specificity via hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions, molecular shape complementarity, electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and aromatic stacking of the flat moieties, or a combination of these.56,62 Shape complementarity along with electrostatic potential are considered to be the major factors determining the specificity of the interaction. On the other hand, hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and stacking interactions play significant roles in stabilizing the RNA–protein interfaces.63

Like antibodies, aptamers that bind proteins recognize specific epitopes on the target surface.9 It is hypothesized that the interaction between an aptamer and its target protein begins with the formation of electrostatic interactions with a protruded protein surface, which establishes an initial contact with the RNA aptamer. Moreover, hydrogen bonds that form with unpaired nucleotides in a dented protein surface help determine binding specificity.64 Single-stranded structures such as stem-loops, bulges, and kinks appear to mediate most specific RNA recognition.65,60 On the other hand, β-sheets on proteins and loops connecting β-strands and α-helices are crucial to interact with single-stranded RNA.66

Many studies of RNA aptamer–protein interactions have shown that electrostatic interactions at the interface between the two are due to the negative charge of the phosphate groups in RNA and positively charged amino acids on the protein.67 This was demonstrated, for example, by the crystal structure of 2′-fluoropyrimidine-modified RNA aptamer (Toggle-25t) bound to the human thrombin (PDB ID: 3DD2).68 The interface between these two molecules occurs at the heparin-binding site on thrombin with the participation of five positively charged amino acid residues (five arginine and three lysine residues). This is not always the case, however: a high density of positive charges is not essential for binding to the target protein, and one illustrative example of this is the crystallographic structure of human IgG bound to its aptamer ligand (PDB ID: 3AGV). The binding of this aptamer to its target is mediated mainly by van der Waals interactions instead of electrostatic interactions.69

Shape complementarity is an important factor contributing to the high affinity and specificity that characterizes aptamer–protein binding.57,43 In fact, the shape complementarity index (SC) for aptamers is comparable to that of antibodies, where both exhibit a high degree of complementarity with their target protein surfaces. Specifically, the SC was measured for 16 aptamer and 34 antibody co-crystal structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), and the mean SC values were found to be 0.71 and 0.69, respectively.57 Additionally, the size of interaction surfaces engaged by aptamers in aptamer–protein complex was on average 976 ± 507 Å2,57 while that of antibody–protein complexes is 737 ± 272 Å2,70 thereby emphasizing high specificity and binding affinity toward their therapeutic target.

Presumably, aptamers bind their ligands by adaptive recognition involving conformational restructuring.71 Flexible unbound regions in the aptamer contribute to adaptability in protein recognition and binding. After the binding site on RNA recognizes complementary surfaces on the protein target, one or both might undergo conformational changes, referred to as “induced fit”.40 Recent research showed that while an aptamer is highly flexible and can adopt a variety of conformations to recognize its target, engagement with the target will select a specific conformation and fix it.72

Yet comparison of free protein and protein–aptamer structures indicates that target proteins do not usually undergo significant conformational changes upon binding to aptamers.69 Residues at the interface of RNA–protein interactions may sometimes adopt novel orientations to make room for the interactions.69 This can be seen from studying the structural features of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-bound A9g aptamer, where no fundamental conformational changes were observed in the overall fold of the enzyme, while limited changes were confined to the residues directly interacting with the aptamer at the binding interface.73 In addition, the crystal structure of C13.18-RNA aptamer in complex with G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) revealed that the kinase domain’s large lobe undergoes an 8° rotation relative to the small lobe.74 The NMR structures of both bound and unbound states for the NF-κB RNA aptamer reveal that the structures are almost the same in both states with moderate RNA reorganization upon protein binding, whereas the NMR structure for aptamer against the ribosomal protein S8 shows significant restructuring when bound to its target.75−77 The same is true with A9g aptamer, which undergoes enforced flipped-out conformation, and the distorted nucleobases represent the typical binding motif in the PSMA/A9g complex.73

As for the effect of metal ions on binding affinity, it depends on the type of interaction with the target. For instance, a recent study found that, under pH = 7.4 with salt (137 mM NaCl), as opposed to the condition without salt, the equilibrium dissociation constant of glycated hemoglobin and its aptamer is lowered. This outcome is most likely caused by the additional salt ions coating the protein, which reduces the effects of electrostatic repulsion and slows the rate at which the complex dissociates,78 thus indicating that salt ions increased the binding affinity of the protein–aptamer interactions.79 Indeed, the proper aptamer fold and, by extension, the presence of stabilizing ions are intrinsically linked to protein–aptamer binding.80 This is evident in the aptamer–hFc1 complex, where the Ca+ ion is critical for folding and stabilizing the adopted characteristic conformation of the aptamer required for the interaction with human IgG proteins with high specificity and affinity. As a result, the active structure of the aptamer is disrupted by the removal of Ca+ ions by a chelating agent, and the bound IgGs are quickly released with no structural change to the native conformation of hFc1 upon binding to the aptamer.81

6. Aptamers as Therapeutics

6.1. Basis for Therapeutic Potential of Aptamers

Basic research involving viruses such as HIV and adenoviruses in the 1980s uncovered structural RNA domains that could bind to viral or cellular proteins. This binding exhibited high affinity and specificity, and it was hypothesized to function in service of viral survival possibly through modulation of the activity of proteins required for viral replication or through inhibition of specific cellular proteins.82 These findings inspired the first study that attempted the use of an RNA aptamer for the purpose of inhibiting a pathogenic protein in 1990. In this study, the expression of decoy trans-activating response (TAR) element RNAs was induced in CD4+ T cells; this is an RNA stem-loop structure required for the activation of the viral trans-activator of transcription (Tat). The decoy molecules were able to bind Tat and inhibit its binding to viral TAR, which made the cells very resistant to HIV.83 From that point, the search was on for small, structured RNA molecules that could bind and modulate the activities of pathogenic proteins.84

Indeed, the specific binding of the three-dimensional structure of aptamers to their targets blocks parts of the protein that could be involved in substrate or other molecular interactions, resulting in inhibition of protein function.5 Thus, the potential therapeutic use of aptamers has many parallels with that of monoclonal antibodies, and naturally with other oligonucleotides. Yet aptamer-based therapeutics offers many advantages over these modalities. Notably, aptamers can be developed against intracellular, extracellular, or cell-surface targets, whereas ASOs or siRNAs can only target intracellular molecules.17

6.2. Factors Affecting Therapeutic Efficacy and Potency of Aptamers In Vivo

The in vivo efficacy of aptamers as therapeutics is determined by their physicochemical characteristics. These in turn dictate their pharmacokinetics in terms of metabolic stability, rate of renal filtration, tissue distribution, immune activation, and non-specific interactions due to their negative charges (polyanionic effect).62

6.2.1. Tissue Distribution

Generally, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNAs), and aptamers show similar tissue distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Aptamers have been introduced in vivo through intravenous (IV), subcutaneous (SC), or intravitreal (IVT) routes.85 After SC administration, the bioavailability of ASOs and aptamers is between 68 and 100%. The kidney, liver, and spleen exhibited the highest concentrations of ASOs, siRNAs, and aptamers. ASOs and aptamers also concentrate in lymph nodes and the bone marrow. Specifically, they are mostly found in cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system of these organs.85 A 2′-fluoro-modified RNA aptamer (A9g) which inhibits the PSMA was found to be well distributed in the body 5 min after injection in the mouse. Then, it was completely eliminated from circulation within 8 h and remained in PSMA+ tumors for up to 72 h.86

6.2.2. Metabolic Stability

The availability of aptamers for biological action is affected by in vivo stability and elimination from the body.15 ASOs, siRNAs, and aptamers are metabolized by nucleases and renally excreted as both metabolites and parent compounds.87 In this regard, rapid nuclease degradation, especially in the case of RNA aptamers, is a major hurdle facing aptamer therapeutics. In fact, the half-life of an RNA oligonucleotide in serum is on the order of a few seconds, and that of a DNA oligonucleotide ranges between 30 and 60 min,15,88 which in either case is too short for any useful application.

Many chemical modifications and conjugations have been tested in hopes of improving aptamer pharmacokinetic properties and making them more suitable for clinical development. Some of the most common sites for modifications of therapeutic aptamers include phosphodiester linkage, sugar ring, bases, and 3′- and 5′-terminals.89 Specifically, the 2′-position of RNA aptamer sugar ring constitutes the most widely modified location, where 2′-amino-pyrimidine nucleosides, 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine nucleosides, 2′-O-methyl purine, and 2′-O-methyl pyrimidine nucleosides are employed.10 It is noteworthy here that 2′-O-methyl and 2′-fluoro ribose modifications have been associated with aptamers that are on their way to the clinic or that have already made it to the clinic.88 On the other hand, the phosphodiester backbone is the most widely modified location in the case of DNA aptamers.90,91

SELEX has been used to select nuclease-resistant sugar-modified oligonucleotides. Utilization of spiegelmers—“mirror-image aptamers”—is another option to circumvent nuclease digestion, as these modified aptamers are highly stable and resistant to enzyme action.92 This is due to the fact that they have l-ribose (RNA spiegelmers) or l-deoxyribose (DNA spiegelmers) oligonucleotide backbones.10

Another class of modified aptamers are Slow Off-rate Modified Aptamers (SOMAmers), which are DNA-based with modified dUTPs at the 5-position.93 This variation resulted in better discovery success rate, target affinity, inhibition efficacy, and metabolic stability.94 Aromatic functional groups that resemble the side chains of phenylalanine and tryptophan or bicyclic aromatic groups such as naphthalene were the most effective.94 One distinguishing feature of SOMAmers is that they interact with their target proteins through hydrophobic interactions as opposed to hydrogen-bonding and polar–polar interactions as in the case of conventional aptamers.95 SOMAmers have found applications in proteomics, where they are used to quantify proteins in biological samples in both diagnostic and research contexts.6

6.2.3. Renal Filtration

In order to circumvent the fast renal clearance of aptamers, various conjugates have been employed for the purpose of increasing the apparent molecular weight above the glomerular filtration size threshold of 30–50 kDa. PEGylation, for instance, adds a 40 kDa polyethylene glycol (PEG) conjugate to the aptamer,27 which has been shown in animal models to lengthen their half-life in the circulation 2–10-fold, from 5–10 min to as long as a day.49 Cholesterol conjugation can also reduce renal filtration rates, although to an apparently lesser extent compared to PEG conjugation.17

6.2.4. Immune Activation

The lack of immunological stimulation, complement activation, or anticoagulation compared to other oligonucleotides is one of the appealing aspects of using aptamers as therapeutics. They were evaluated in accordance with the ICH’s (International Council for Harmonization) requirements for pharmaceuticals used by humans, and after sub-chronic administration for up to 13 weeks, no substantial pharmacological safety concerns or evidence of the tested aptamers’ genotoxic effects was found.85 Moreover, the safety of A9g aptamer mentioned earlier was extensively studied in vivo by Dassie et al. (2014). The systemic administration of this aptamer for 4 weeks in mice bearing metastatic prostate cancer did not affect the general health of the mice, or their major organs, or blood cell types; neither did it result in an increase in the expression of inflammatory cytokines, interferons, or viral RNA recognition genes in the spleen and liver.86

Internalization of RNAs in mammalian cells is known to stimulate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). For instance, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) 3, 7, 8, and 13, found primarily in endosomal compartments, recognize long dsRNA, AU- or GU-rich single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), and ssRNA containing a CGGAAAGACC sequence. This results in the activation of innate immune and inflammatory responses, which might entail undesirable side effects, dampening their therapeutic efficacy. For siRNAs, this immune stimulation was readily eliminated when uridine bases were replaced with either 2′-fluoro (2′-F)- or 2′-O-methyl (2′-OM)-modified counterparts.96 This may be attributed to the ribose sugar being a hallmark of RNA recognition.97 It is of note that 2′-OMe modification is not foreign to mammalian cells, since it can be found in ribosomal and transfer RNAs, but this does not apply to 2′-F modification.98 In fact, one study recommended studying the safety of in vitro transcribed RNA aptamers further, as it demonstrated that 5′-triphosphate (5′ppp) and 2′-F pyrimidine-modified RNA aptamers targeted for intracellular therapy could be detected by cytoplasmic PRRs and could trigger off-target and inflammatory side effects.98 Thus, immune stimulation and possible side effects of aptamers should be investigated more thoroughly, especially those of intracellular aptamers (intramers).49

6.2.5. Antidote Control

The presence of antidotes to aptamers, which have been confirmed in vivo to control the duration of their functionality, is one of their most unique features that make them attractive candidates for therapeutic applications.99 This is in contrast to antibodies and small-molecule drugs whose duration of action can be very difficult to control.10 Aptamer antidotes consist of complementary sequences able to hybridize specifically to their sequence, disrupting three-dimensional structure and target-binding ability.10 Universal antidotes also exist that are made up of polycationic biopolymers such as β-cyclodextrin-containing polycation (CDP) and polyphosphoramidate polymer (PPA-DPA), and they bind non-specifically and inhibit the activity of polyanionic oligonucleotides such as aptamers.43,100

6.3. Aptamers as Targeted Cancer Therapeutics

While “traditional” cytotoxic chemotherapies usually kill rapidly dividing cells in the body by interfering with cell division, targeted cancer therapies are designed to interfere with specific molecules necessary for tumor growth and progression. Given their greater selectivity and thus fewer side effects, targeted cancer therapies have become a major focus of cancer research. Broadly, targeted cancer therapeutics are classified as small chemicals, peptides, nucleic acids, and monoclonal antibodies.101 In this context, a wide range of molecules involved in key processes for tumor progression, such as proliferation, adhesion, migration, and immune response, have been successfully targeted by aptamers (Morita et al., 2018).42

Currently, there are two aptamers for cancer treatment that are being tested in clinical trials. AS1411/AGRO001 (Antisoma) aptamer was evaluated in a phase-I clinical trial for advanced solid tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00881244) and phase-II clinical trials for acute myeloid leukemia (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT01034410, NCT00512083, and NCT00740441) and metastatic renal cell carcinoma (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00740441).102 AS1411 is a quadruplex-forming guanine-rich (G-rich) 26-mer DNA aptamer that binds to nucleolin protein overexpressed in many cancer cells, blocking the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), therefore sensitizing the tumor cells to chemotherapy and improving their tumor-killing effects.103 In 2011, AS1411 was acquired by Advanced Cancer Therapeutics (ACT) and renamed ACT-GRO-777.104 Recent research has explored the use of AS1411 as a carrier for the delivery of various cancer drugs into cancer cells mediated specifically by nucleolin internalization. Indeed, AS1411 represents the first aptamer to enter clinical trials as a cancer therapeutic agent.101 Ironically, it was not generated by SELEX but was discovered serendipitously based on its ability to be taken up by cancer cells.105

NOX-A12 aptamer was also tested for multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, metastatic colorectal cancer, metastatic pancreatic cancer, and glioblastoma in phase-II clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT01521533 NCT01486797, NCT03168139, NCT04901741, and NCT04121455, respectively).49 NOX-A12 is a 45-nucleotide-long spiegelmer aptamer that was developed by a proprietary spiegelmer technology in Noxxon Pharma (Germany). It specifically neutralizes CXC chemokine ligand 12/stromal cell-derived factor-1 (CXCL12/SDF-1), a key regulatory chemokine for migration of leukemia stem cells to the bone marrow.104

In general, aptamers used in cancer therapy are classified into three categories: aptamers targeting immune-regulatory components, aptamers functioning as “escort” molecules for selective delivery of anti-tumor therapeutic agents, and aptamers against a variety of cancer-specific proteins and protein kinases.

Aptamers targeting immune-regulatory components can modulate the immune system which could be deactivated by tumor cells.49 The prime example is M9-9 RNA aptamer, introduced in 2003. M9-9 specifically binds with high affinity to the murine CTLA-4 receptors expressed on activated, but not resting, T cells. It is evident that CTLA-4 receptors deliver a negative signal, attenuating T-cell responses, and thus its inhibition can prevent immune system inactivation, which in turn promotes tumor elimination.106

The second category of aptamers used in cancer is aptamers that act as “escort” molecules for selective delivery of anti-tumor therapeutic agents.103 In this category, cell-type-specific aptamers serve as carriers for delivering other therapeutic agents to the target cells or tissue. In this respect, A9 and A10 aptamers against the extracellular domain of the PSMA have been extensively characterized for siRNA delivery by developing different approaches based on either covalent107 or non-covalent conjugation.108 These two aptamers were selected by the Coffey group at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Maryland, USA.109 As PSMA is constitutively internalized, the PSMA-specific aptamer can mediate the delivery of various anti-cancer agents into prostate cancer cells via endocytosis.110 In this approach, aptamers have been functionalized to make conjugation with different molecules including chemotherapy agents, small interfering ribonucleic acids (siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), peptides, or even another aptamer. Such hybrid molecules, also termed “aptamer-chimeras”, can specifically bind to target cells and deliver their cargo.111 For instance, AlShamaileh et al. used a chimeric structure composed of an epithelial cell adhesion molecules (EpCAM)-specific RNA aptamer as the binding moiety and a survivin siRNA sequence to target survivin expression in colorectal cancer stem cells. The efficacy of the chimera was tested both in vitro using EpCAM-positive colorectal cancer cell line (HT-29) and in vivo using HT-29 xenograft tumor-bearing mice. The reported data indicated that the aptamer–siRNA chimera is able to effectively down-regulate survivin in EpCAM-positive colorectal cancer cells without the aid of transfection agent or other delivery vehicles.112 Similarly, nanotechnology also enables researchers to couple different therapeutic payloads to aptamers, leading to the development of aptamer nanocomplexes.113 In this regard, Alshaer et al. used the anti-CD44 aptamer (named Apt1) as targeting ligand for active targeting of CD44-expressing triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells with gene-silencing siRNA.114 Subsequently, bispecific constructs have been developed to allow simultaneous recognition of multiple targets and thus enhance the specificity as well as the efficacy of the combined molecules. An example comes from Zheng et al. (2017), where the authors combined two aptamers targeting cancer-relevant epitopes CD44 and EpCAM through a double-strand adaptor containing an annealed portion of 23 bp and 2–3 unpaired bases. The resulting RNA molecules show an improved circulation half-life and significantly inhibited both CD44 and EpCAM activities, giving a more effective inhibition of cell growth in vitro. Furthermore, this bispecific CD44-EpCAM aptamer inhibits tumor growth in the intraperitoneal ovarian cancer xenograft model more effectively than using each single aptamer alone or in combination.115

The final category of aptamers comprises free aptamers targeted against a variety of cancer-specific proteins. In this category, an aptamer serves as an antagonist for blocking the interaction of disease-associated targets, such as proteins involved in cancer cell adhesion and invasion.103 For example, Lee and associates have reported DNA aptamers called PNDA-3 that bind to human periostin protein and block its interaction with its cell surface receptors. The results proved that PNDA-3 binding significantly decreases the activation of integrins αvβ3- and αvβ5-dependent signal transduction pathways and potently inhibits the adhesion, migration, and invasion of tested breast cancer cells both in vitro and in an in vivo mouse xenograft model.116 In a complementary fashion, an increasing number of aptamers has been generated to target specific cell-surface signaling receptors such as receptors with kinase activities in an attempt to block the subsequent downstream activation and signaling for tumor growth.

6.4. Aptamer-Based Kinase Inhibitors

About 2% of human genes encode protein kinases, which are pervasive enzymes with roles in key cell processes such as proliferation, survival, apoptosis, metabolism, transcription, and differentiation. Thus, abnormality in kinase activity is involved in many pathogenic conditions, especially those related to inflammatory or proliferative responses.117 Notably, mutations in certain kinase genes impart drug resistance to cancer cells, creating complicating challenges in cancer management.118 Some estimates actually indicate that protein kinases may comprise over a quarter of all pharmaceutical drug targets.119 Aberrant protein kinase activity has been targeted for therapy using various approaches. For instance, antibodies have been used to target protein kinases that possess extracellular domains with high specificity, and small molecules (<900 Da) have been used to inhibit transmembrane or intracellular protein kinases.120 Most of the available kinase inhibitors compete with ATP for the catalytic domain, but they are not very specific in their inhibitory action,121 mainly because kinases within the same subfamily show great sequence homology in their catalytic domains. This lack of specificity results in off-target effects and early drug resistance.122 Thus, there is a need for new inhibitors with the ability to home in on a specific protein kinase among all 518 human kinases. Such selectivity in inhibition would help circumvent the aforementioned problem of side effects and resistance.123 Research has been focused on finding new classes of inhibitors with new binding modalities that interact selectively with their targets and possibly bind outside the catalytic domain.124 Multiple aptamers have been selected to target either the extracellular or the intracellular domains of different protein kinases, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Aptamers to Protein Kinases and Their Applications.

| name of selected aptamer | chemistry | molecular target | type of SELEX | target | mechanism of action | applications | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamers to Cell Surface Kinase Receptors | |||||||

| sgc8 | DNA | protein tyrosine kinase-7 (PTK7) | cell-SELEX | T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (T-ALL) | binds with high specificity and affinity to PTK7 surface target on T-ALL cells and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) | • Sgc8 aptamer acts as cell-specific probe for selective diagnosis and imaging of cancer cells highly expressed PTK7 biomarker, cell-specific delivery of therapeutic agents, and molecular imaging | (126−135) |

| R13 | DNA | EGFR receptor | cell-SELEX | A549 NSCLC cells | binds to EGFR and able to internalize into the cells | • inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell apoptosis | (136−138) |

| • photodynamic therapy | |||||||

| • diagnosis of ovarian cancer cells and tumor imaging in vivo | |||||||

| U2 | DNA | EGFRvIII receptor | cell-SELEX | glioma U87MG cells overexpressed EGFRvIII | identifies EGFRvIII on the surface of target cells | • 188Re-radiolabeled U2 serves as a molecular probe for imaging and diagnosing EGFRvIII overexpressing glioblastoma xenografts in mice | (139−141) |

| • aptamer U2 acts as drug candidate for glioblastoma therapy as it inhibits the proliferation, migration, invasion, and downstream signaling of U87-EGFRvIII cells | |||||||

| • aptamer U2 increases the radiosensitivity of U87-EGFRvIII in vitro and improves the antitumor effect of 188Re-labeled U2 aptamer to GBM in vivo | |||||||

| • U2-AuNP gold nanoparticles inhibit the proliferation and invasion of U87-EGFRvIII cell lines and prolong the survival time of GBM-bearing mice | |||||||

| PDR3 | 2′-fluoropyrimidine RNA | PDGFRα receptor | protein-based SELEX | – | binds to PDGFRα expressed on human glioblastoma U251-MG cells and able to internalize into the cells | • targets the PDGFRα-STAT3 axis by inhibiting gene expression of STAT3 and upregulating the expression of JMJD3 and p53, thus inducing apoptosis and reducing cell viability | (142) |

| • targeted delivery of STAT3-siRNA into U251-MG cells | |||||||

| GL43.T | 2′-fluoropyrimidine RNA | EphB3 receptors | cell-SELEX | human glioma cell line U87MG | aptamer binds EphB2/EphB3 and antagonizes the ephrin/EphB interaction; aptamer co-localizes with the EphB3 receptor on target cells and internalizes in the cell | • inhibits cell viability and functionally interferes with ephrinB1-induced cell adhesion | (143) |

| Apt_46 | DNA | FGFR2b | protein-based SELEX | – | inhibits the aberrant activation and downstream signaling of FGFR 2b in cancer cells overexpressing FGFR2b by inhibiting the unliganded dimerization of FGFR2b | • Apt_46 acts as dimerization inhibitors that inhibits unliganded receptor dimerization of FGFR 2b in receptors in cancer | (144) |

| Kit-129 | DNA | murine c-KIT receptor | STACS cell-SELEX | BJAB lymphoblastoma cell line overexpressing the murine c-KIT cell surface receptor | binds to c-KIT expressed by a mast cell line or hematopoietic progenitor cells, and specifically blocks binding of the c-KIT ligand stem cell factor (SCF) | • separates a c-KIT-positive subpopulation in a complex mixture of bone marrow cells | (145, 146) |

| • miRNA-aptamer chimera for targeted aptamer-based delivery of miR-26a into in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and basal-like breast cancer cells in mouse models | |||||||

| aptamer #1 | DNA | c-KIT receptor | hybrid SELEX | human erythroleukemia cell line (HEL cells) | binds to c-KIT expressed on human erythroleukemia cells and able to internalize into the cells | • separation of a c-KIT-positive subpopulation in a complex mixture of bone marrow cells | (146−149) |

| • aptamer–methotrexate conjugate (Apt-MTX) efficiently and selectively inhibits the growth of primary AML cells derived from patient marrow specimens | |||||||

| • miRNA–aptamer chimera for targeted aptamer-based delivery of miR-26a mimic to basal-like breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) | |||||||

| • targeted labeling of primary human gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) both ex vivo and in vivo | |||||||

| • electrochemical aptasensor for the detection of soluble KIT present in the conditioned media of cancer cell lines | |||||||

| Aptamers to Intracellular Kinases | |||||||

| ODN1 | DNA | p210bcr-abl kinase | protein-based SELEX | – | inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of p210bcr-abl; inhibition is non-competitive relative to ATP | • reduces the total amount of protein phosphotyrosine in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) K562 cells and inhibits its cloning ability | (150, 151) |

| PKC6 and PKC10 | RNA | PKC βII | protein-based SELEX | – | inhibits the autophosphorylation and the kinase activity of PKC βII enzyme | – | (44) |

| aptamer families I and II | RNA | diphosphorylated form of the extracellular regulated kinase 2 (ppERK2) | protein-based SELEX | – | inhibits phosphotransferase activity of ppERK1/2 by competing with both substrate and ATP binding through steric exclusion | • development of MAPK inhibitors targeted the activation lip of ERK2 to control the cellular responses resulting from the activation of signaling pathways | (152) |

| C3 | RNA | unphosphorylated ERK2 | protein-based SELEX | – | binds the MAP kinase insert domain; inhibits Erk2 activation by its upstream kinase MKK1, but not Erk2 kinase activity | • studying the biological role of the respective kinase subdomain | (153) |

| • promising class of protein kinase inhibitors that can be applied to target individual subdomains and block domain specific functions without affecting kinase activity | |||||||

| E21 | RNA | ectodomain of EGFRvIII | protein-based SELEX | – | intracellularly binds newly produced unglycosylated EGFRvIII and blocks its glycosylation | • targeting cytoplasmic post-translational modifications | (154) |

| C13 | RNA | GRK2 | protein-based SELEX | – | inhibits the kinase activity of GRK2 by competing with ATP binding | – | (155) |

| H5/V36 and V15 | 2′-fluoropyrimidine RNA | c-KIT WT | protein-based SELEX | – | inhibits the kinase activity of wild-type and mutant types in different moded of action (competitive, purely non-competitive, and mixed-type mechanism of action with respect to ATP) and different potencies | – | (156) |

| c-KITm D516V | |||||||

| c-KITm D516H | |||||||

Aptamers targeting receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) have been comprehensively overviewed by Camorani et al. These aptamers have been selected against the extracellular domain of cell surface RTKs, which are EGFR, EGFRvIII, ErB2, ErB3, c-Met, PDGFRβ, and AXL, thus interfering with ligand-induced activation or receptor homo-/heterodimerization.125

For example, a T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line was used in cell-based SELEX, resulting in the selection of a DNA aptamer designated “sgc8”. It turned out that this aptamer specifically targets the transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase 7 (PTK7), also known as colon carcinoma kinase-4 (CCK-4). After binding to its target, the sgc8c aptamer is internalized into the cell via endocytosis.126,127 In order to utilize the specificity of sgc8c to its target, doxorubicin (Dox) was conjugated to this aptamer and delivered to cancer cells that express PTK7, avoiding toxicity that would otherwise result from its interaction with normal cells.128 An early phase-I clinical trial was conducted (NCT03385148) that aimed to assess the safety, biodistribution, and dosimetric properties of an imaging conjugate that contains Sgc8 in healthy and colorectal cancer participants. However, to date, no results have been posted in ClinicalTrials.gov for this study.

In 2018, Zhang et al. published the first application of 68Ga-labeled Sgc8 in colorectal cancer patients, and the results demonstrated that 68Ga-Sgc8 is safe and tolerable for clinical imaging and has the potential for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant colorectal cancer in three patients enrolled in this study.129 The ability of many aptamers to be internalized via endocytosis after specifically recognizing their cell surface receptor makes them valuable tools for targeted cancer therapy and for delivering various therapeutic agents inside cancer cells. Such agents include interfering RNA therapeutics114,157 and chemotherapeutic drugs,158 among others. This approach helps concentrate the effect of treatment in cancer cells in a selective manner that bypasses normal cells.

The first aptameric oligonucleotide specific for an intracellular oncogenic tyrosine kinase was called oligodeoxynucleotide 1 (ODN1), isolated in 1994 by Bergan and co-workers against p210bcr-abl enzyme.150 Incubation with ODN1 inhibited the tyrosine kinase activity of p210bcr-abl isolated from chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cell line K562. The inhibition was non-competitive relative to ATP and had an IC50 of 0.52 μM. Moreover, this inhibition applied only to auto-phosphorylation activity and did not affect substrate phosphorylation even at 50 μM ODN1.150 The next year, Bergan et al. used electroporation to introduce the ODN1 aptamer inside K562 cells, which resulted in a significant reduction in the total amount of protein phosphotyrosine in the cells and inhibited the cloning ability of K562 cells.151

The unmodified RNA aptamers PKC6 and PKC10 were generated using SELEX and found to bind protein kinase C isoenzyme βII (PKC βII) with nanomolar affinities. In addition, PKC βII recognition was highly specific, distinguishing it from the closely related splicing alternative PKC βI, and showed no effect on PKC α. Both aptamers were capable of inhibiting PKC βII autophosphorylation and target phosphorylation.44

Another intracellular kinase target for aptamers is the activated diphosphorylated form of the extracellular regulated kinase 2 (ppERK2). Seiwert et al. characterized two RNA aptamer families I and II that bind to ppERK2 with high specificity and affinity, where dissociation constants (KD) for family II aptamers were 4.7 nM for ppERK2 and 50 nM for ERK2. Both aptamers inhibited phosphotransferase activity in vitro, and Lineweaver–Burk enzyme kinetics analysis revealed that family II aptamer inhibits ppERK2 activity by competing with both substrate and ATP binding.152 The unphosphorylated ERK2 was also targeted by SELEX technology, resulting in an RNA aptamer C3 that was actually capable of binding both inactive ERK2 and active ppERK2 with KD values of 92 nM and 29 nM, respectively.153 ATP at concentrations up to 1 mM was not found to competitively affect C3 binding to ERK2. Moreover, C3 did not act on ERK2 phosphorylation of specific (Elk1) and non-specific (myelin basic protein (MBP)) substrates in vitro. Thus, C3 inhibition of ERK2 was ATP- and substrate-independent, representing a different mode of inhibition relative to other aptamers targeting ERK2. In addition, C3 was found to bind and block the function of the MAP kinase insert domain, which interacts with the activation loop, resulting in a conformational change required for activation of ERK2 by upstream activating kinase MKK1.153

Liu et al. produced an RNA aptamer called E21 that recognizes human epidermal growth factor receptor variant III EGFRvIII, which is highly expressed on glioblastoma cells.154 This aptamer recognizes the unglycosylated form of EGFRvIII because it was selected in SELEX against E. coli-expressed human EGFRvIII lacking glycosylation. Upon delivery of the aptamer inside the cells using a lipid system, E21 binds with high specificity and affinity to the newly produced unglycosylated EGFRvIII and blocks its glycosylation, resulting in a 90% reduction of cell surface expression and increased apoptosis compared to negative control.154

An RNA aptamer designated C13 was described by Mayer et al. that specifically binds the catalytic kinase domain of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) competing with ATP binding.155 C13 was able to inhibit the kinase activity of GRK2 in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 value of 4.1 nM ± 1.2 nM. Despite its apparent interaction close to the ATP binding pocket, the C13 aptamer was specific for GRK2 and did not bind to other members of the same GRK family or a panel of other kinases.155 Studying the crystallographic structures of truncated C13 aptamer bound to GRK2 revealed that it binds between the small and large lobes of the kinase domain, and that it stabilizes a unique inactive conformation of GRK2. Specifically, an adenine moiety from the aptamer projects deep into the ATP-binding pocket of GRK2, blocking its function.74

Recently, Shraim et al. selected modified RNA aptamers that could bind the intracellular kinase domain of wild-type and mutated D816H/ D816V c-KIT with affinities in the nanomolar range.156 Aptamers H5/V36 and V15 were able to inhibit the kinase activity of their targets in a non-competitive fashion, probably by interacting with less conserved parts of the kinase, which makes them potentially more selective in comparison to small molecules that inhibit ATP binding. Aptamer V15 inhibited the kinase activity of the mutated c-KIT to a greater extent in comparison to the wild type, which might mean it could be a promising lead compound for designing cancer-targeting drugs. On the other hand, H5/V36 was highly selective to the wild-type c-KIT kinase, which offers a tool for functional analysis of this kinase.156

6.5. Aptamers in the Clinic

Despite the increasing number of published studies demonstrating advances in the development of therapeutic aptamers, there is very slow progress in the utilization of this knowledge in clinical practice, particularly regarding the use of aptamers in clinical trials.47 The public clinical trials database (http://clinicaltrials.gov) lists around 52 clinical trials using aptamers for a wide range of therapeutic applications. Thus far, one aptamer has received the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s approval for clinical use. Pegaptanib was approved for therapeutic use by the FDA in December 2004 and is currently marketed by Pfizer and Eyetech as Macugen. It is an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A165 aptamer for the treatment of the neovascular form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD).17 Since its approval, Macugen aptamer reached peak sales of $185 million in its first full year of sales in the United States.159 However, it has been displaced by antibody-based anti-VEGF therapeutics such as Lucentis (ranibizumab), Avastin, and Eylea (aflibercept). In fact, the most likely explanation is that these anti-VEGF drugs inhibit all isoforms of VEGF, including VEGF-121 and VEGF-110, whereas Macugen is selective for VEGF-165.159 Here, it is noteworthy to recognize that Macugen represents the first historical success of aptamers as drug therapy, which indicates the high potential of aptamers to be used in the clinical application and, without any doubt, opens the door for further ongoing studies for many applications of aptamers in the future.

7. Delivery of Intracellular Aptamers

The stability of nucleic acid-based aptamers in the intracellular environment makes them more appropriate for use in therapeutic targeting of intracellular proteins, such as transcription factors and signal transduction proteins and enzymes, than antibodies which undergo denaturation and inactivation inside cells.99 However, intracellular delivery of aptamers for the inhibition of targets within the cell remains a challenging aspect of their therapeutic application.160 Yet, intracellularly applied aptamers (intramers) have been successfully employed in targeting a number of biomedically relevant intracellular proteins such as E2F transcription factor and β catenin protein.161 They have also been applied in functional genomics and proteomics, where they have helped in uncovering novel biological functions of protein and protein domains and targeting signal transduction cascades for modulation.162

Available approaches for intracellular delivery are often based on the in vitro and in vivo transfection methods of small interfering RNA (siRNA), using, for instance, cationic lipids or liposomes.163 Cationic lipids readily form unilamellar structures that can interact with anionic nucleic acids to form a “lipoplex” complex, which can then also interact with the negatively charged cell membrane, promoting endocytosis. A group of researchers used lipofectamine 2000 to transfect HEK293 cells and cultured rat cortical neurons with A2 aptamer, and they effectively inhibited AMPA receptor trafficking to the cell membrane in both cases.46 Surprisingly, an RNA aptamer termed K61 retained its inhibitory activity with high specificity and affinity and did not need to be protected from nuclease digestion upon cationic lipid transfection into HeLa cells, where it remained for at least 6 h.164 Zamay and collaborators, on the other hand, used the natural polysaccharide arabinogalactan (AG) to enhance the delivery of a DNA aptamer designated NAS-24 that targets vimentin filament protein inside Ehrlich ascites adenocarcinoma cells, and it was successful in driving apoptosis of these cells both in vitro and in vivo.160 Cellular delivery of aptamers using AG was not DNA-size dependent, but its success was limited to asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR)-positive cells.160 Electroporation is another cellular delivery method that has been applied with aptamers. For instance, one square waveform of 200 V for 20 ms was used to deliver Ras a1 ssDNA aptamer that targets Ras into vascular smooth muscle cells.165

Utilization of cell surface receptors as “Trojan horses” carrying aptamers into the cell is another potential methodology.99 Moreover, aptamers themselves can serve as carriers for other aptamers into the cell as “aptamer–aptamer” conjugates. The carrier aptamer could bring the therapeutic aptamer into its target cell through the recognition of a specific cell receptor. One such carrier aptamer is AS1411 that binds the multifunctional nucleolin protein, whose expression is enhanced on cancer cell membrane, but it also moves constantly back and forth between the nucleus and cytoplasm. AS1411 is taken up only by malignant cells166 and mainly through micropinocytosis, but it appears that clathrin- and caveolae-dependent and clathrin- and caveolae-independent pathways may also be involved.51 The shuttling of nucleolin between different compartments might be related to the mechanism which helps AS1411 avoid the macropinosomes/endosomes and enter the cytoplasm.52 Based on nucleolin’s potential in targeting cancer cells, Kotula et al. (2014) successfully used a nucleolin-targeting aptamer to carry the therapeutic β-arrestin 2 aptamers into cancer cells.167 Along the same lines, Magalhães et al. (2012) presented Otter and c1 aptamers, which are general purpose cell-penetrating RNA aptamers (CPRs) that enter the cell through clathrin-mediated endocytosis.168 The two aptamers apparently have what might be a general signal for RNA transport into the cell, represented by two common motifs composed of the sequence CUUUAUGAU and a pyrimidine-rich region.168

Another approach to cellular delivery is the expression of RNA aptamers using viral systems,99 leading to the accumulation of aptamers in the nucleus or the cytoplasm.10 In 1999, the Famulok group first expressed an intramer against the intracellular domain of the β2 integrin LFA-1 protein using the vaccinia virus-based T7-RNA expression system.169 One feature of this system is that it expresses RNA flanking structures that might help stabilize the aptamer’s functional three-dimensional structure. Similarly, an RNA aptamer against the NF-κB p50 protein (A-p50) was expressed intracellularly using an adenoviral vector carrying H1 RNA polymerase III promoter.170 This aptamer was expressed without flanking sequences, and the inhibition of NF-κB was successfully demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo. Despite this potential, viral systems may also present challenges for in vivo use since the expression of viral genes in the host cell results in a strong immune response.171 One alternative that has been used to deliver an RNA aptamer that modulates the function of nuclear β-catenin is functionalized gold nanoparticles. This approach was compared to liposome delivery and was found to be more efficient, carrying up to 200 RNA aptamer molecules per nanoparticle.171

8. Concluding Remarks and Prospects for Aptamer Therapeutics

Aptamers are unique biomolecules that combine the attractive features of both antibodies and small drug molecules. Specifically, they have target affinities and specificities comparable to those of antibodies, and their sizes range between those of small molecules and antibodies.17 Thus, similar to small molecules, they have access to parts of a protein that antibodies cannot reach, but they are not necessarily restricted to interaction with the active site of the protein as in the case of small molecule drugs, and so, they can potentially disrupt protein–protein interactions.172

Consequently, in order to reap the benefits of aptamer-based therapeutics, both researchers and manufacturers have devoted much effort to improve aptamer production technologies.62 Over the past two decades, the field of aptamers has emerged as a serious alternative modality in chemical biology and biomedicine.4 Many studies are continuously supporting and exploring the promise of aptamer technology in therapy and basic research.62 For instance, there have been great developments in exploring the modulation of protein function by aptamers and exploiting their target specificity in delivering other therapeutic agents to specific tissues. It is expected by scientists that aptamers are capable of transforming the field of nanomedicine.173 As Larry Gold said, “the future for applications of aptamers will be limited only by our imaginations, as is always the case.” 6

One of the most fascinating applications of aptamers is in competition assays called aptamer-displacement assays, in which small molecules can displace the aptamer from its interaction with a target molecule of interest. Such an assay allows the isolation of lead compounds in drug design capable of modulating target activity.164,174 These small molecules inherit the properties of the parent aptamer and can be easily applied to cell culture and animal models systems.155 Three distinct aptamer displacement reactions from the surface of living cells have recently been demonstrated using complement DNA, toehold-labeled cDNA, and single-stranded binding (SSB) protein for displacing a cancer cell-bound aptamer, Sgc8, from the living cells. Then, the SSB-mediated aptamer displacement approach was adopted to detect membrane protein post-translation and to improve selection efficiency of cell-SELEX.175

Notwithstanding the above, aptamers have not yet claimed their promised place in therapeutics. One reason is that selection of desirable aptamers using SELEX has a relatively low success rate, and the process itself is time-consuming. Another reason is that small molecules are still preferable because they are cheaper to manufacture and because of their smaller sizes.176 In addition, since most available aptamers today are synthesized in vitro, their safety and efficacy in vivo have yet to be confirmed.43 In spite of these challenges, many encouraging improvements in aptamer selection and constitution, and the history of other nucleic acid therapeutics, should propel academics to pursue the utilization of aptamers in therapeutic applications.62 With more emphasis on high-throughput synthesis of oligonucleotides, it is expected that the cost of aptamer production will drop, making aptamers more feasible alternatives to antibody therapies and some organic drugs.173 Finally, we should not be quick to judge aptamer therapeutics solely on the fact that only one aptamer-based drug has been approved by the FDA so far. This drug (Macugen) was approved in an impressively short time after its introduction in the 1990s,177 comparable to the timeline of approval of the first antibodies used in therapy. In addition, Macugen generated over U.S.$200 million in its first year on the market, which is a reminder of the potential of aptamers as drugs and an incentive to pursue such applications.10 At the end of the day, as Kaur and Roy put it: “Whether this is a race between the hare and the tortoise or if this is a unique case where history does not repeat itself, only time will tell.” 172

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; review and editing, M.A. and B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of the ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science virtual special issue “New Drug Modalities in Medicinal Chemistry, Pharmacology, and Translational Science”.

References

- Gilbert W. Origin of life: The RNA world. Nature 1986, 319, 618. 10.1038/319618a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk C.; Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249 (4968), 505–510. 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington A. D.; Szostak J. W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346 (6287), 818–822. 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famulok M.; Mayer G. Aptamers and SELEX in Chemistry & Biology. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21 (9), 1055–1058. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P.; Viles K. D.; Soule E. E.; Woodruff R. S. Application of Aptamers for Targeted Therapeutics. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz). 2013, 61 (4), 255–271. 10.1007/s00005-013-0227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold L. SELEX: How It Happened and Where It will Go. J. Mol. Evol. 2015, 81 (5–6), 140–143. 10.1007/s00239-015-9705-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington A. D.; Conrad R. Aptamers as potential nucleic acid pharmaceuticals. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev. 1995, 1, 185–214. 10.1016/S1387-2656(08)70052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeitner Z.; András J.; Gyurcsányi R. E.; Mészáros T. Is less more? Lessons from aptamer selection strategies. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 101, 58–65. 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulbachinskiy A. V. Methods for selection of aptamers to protein targets. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2007, 72 (13), 1505–1518. 10.1134/S000629790713007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhin A. V.; Tarantul V. Z.; Gening L. V. Aptamers: Problems, Solutions and Prospects. Acta Naturae 2013, 5 (4), 34–43. 10.32607/20758251-2013-5-4-34-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blind M.; Blank M. Aptamer Selection Technology and Recent Advances. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2015, 4, e223. 10.1038/mtna.2014.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W.; Xin P.; Clawson G. A. Minimal primer and primer-free SELEX protocols for selection of aptamers from random DNA libraries. Biotechniques 2008, 44 (3), 351–60. 10.2144/000112689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J. D.; Gray D. M. Selection of genomic sequences that bind tightly to Ff gene 5 protein: primer-free genomic SELEX. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32 (22), e182. 10.1093/nar/gnh179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosch F.; Buchner K.; Klussmann S. In vitro selection using a dual RNA library that allows primerless selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34 (12), e86. 10.1093/nar/gkl463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R. R.; Sullenger B. A.; Rusconi C. P. Developing aptamers into therapeutics. J. Clin. Invest. 2000, 106 (8), 929–934. 10.1172/JCI11325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske D.; Blank M.; Buhmann R.; Resch A. Aptamers-basic research, drug development, and clinical applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 69, 367–374. 10.1007/s00253-005-0193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe A. D.; Pai S.; Ellington A. Aptamers as therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 537–550. 10.1038/nrd3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi F. Aptamers Selected for Recognizing Amyloid β Protein-A Case for Cautious Optimism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19 (3), 668. 10.3390/ijms19030668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X.; Li H.; Zhao L.; Zhang Y.; Liu Z. Oligonucleotide aptamers: Recent advances in their screening, molecular conformation and therapeutic applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112232. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu C.; Khan I. M.; Wang Z. Capture-SELEX for aptamer selection: A short review. Talanta 2021, 229, 122274. 10.1016/j.talanta.2021.122274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan G.; Hosu O.; De Wael K.; Lobo-Castanon M. J.; Cristea C. Aptamers in biomedicine: Selection strategies and recent advances. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 376, 137994. 10.1016/j.electacta.2021.137994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M. Aptamers targeting cell surface proteins. Biochimie 2018, 145, 63–72. 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dua P.; Kim S.; Lee D. K. Nucleic acid aptamers targeting cell-surface proteins. Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 2011, 54 (2), 215–225. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel K. W.; Hernandez L. I.; Dassie J. P.; Thiel W. H.; Liu X.; Stockdale K. R.; Rothman A. M.; Hernandez F. J.; McNamara J. O.; Giangrande P. H. Delivery of chemo-sensitizing siRNAs to HER2 -breast cancer cells using RNA aptamers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40 (13), 6319–6337. 10.1093/nar/gks294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camorani S.; Esposito C. L; Rienzo A.; Catuogno S.; Iaboni M.; Condorelli G.; de Franciscis V.; Cerchia L. Inhibition of Receptor Signaling and of Glioblastoma-derived Tumor Growth by a Novel PDGFRβ Aptamer. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22 (4), 828–841. 10.1038/mt.2013.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaboni M.; Fontanella R.; Rienzo A.; Capuozzo M.; Nuzzo S.; Santamaria G.; Catuogno S.; Condorelli G.; de Franciscis V.; Esposito C. L. Targeting Insulin Receptor with a Novel Internalizing Aptamer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e365. 10.1038/mtna.2016.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy J. M.; Lewis S. D.; Kurz M.; Boomer R. M.; Thompson K. M.; Wilson C.; Mccauley T. G. Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution of Novel Aptamer Compositions. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21 (12), 2234–2246. 10.1007/s11095-004-7676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold L.; Janjic N.; Jarvis T.; Schneider D.; Walker J. J.; Wilcox S. K.; Zichi D. Aptamers and the RNA World, Past and Present. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4 (3), a003582. 10.1101/cshperspect.a003582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock L. C.; Griffin L. C.; Latham J. A.; Vermaas E. H.; Toole J. J. Selection of single-stranded DNA molecules that bind and inhibit human thrombin. Nature 1992, 355 (6360), 564–566. 10.1038/355564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckman J.; Green L. S.; Beeson J.; Waugh S.; Gillette W. L.; Henninger D. D.; Claesson-Welsh L.; Janjić N. 2′-Fluoropyrimidine RNA-based aptamers to the 165-amino acid form of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165). Inhibition of receptor binding and VEGF-induced vascular permeability through interactions requiring the exon 7-encoded domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273 (32), 20556–20567. 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlotzka B.; Leva S.; Eschgfäller B.; Burmeister J.; Kleinjung F.; Kaduk C.; Muhn P.; Hess-Stumpp H.; Klussmann S. In vivo properties of an anti-GnRH Spiegelmer: an example of an oligonucleotide-based therapeutic substance class. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99 (13), 8898–8902. 10.1073/pnas.132067399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang B; Han K; Lee S. W. Prevention of passively transferred experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis by an in vitro selected RNA aptamer. FEBS Lett. 2003, 548 (1–3), 85–9. 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00745-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proske D; Höfliger M; Söll R. M.; Beck-Sickinger A. G.; Famulok M. A Y2 receptor mimetic aptamer directed against neuropeptide Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277 (13), 11416–22. 10.1074/jbc.M109752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H.; Lakshmipriya T.; Gopinath S. C.; Anbu P. High-Affinity Detection of Metal-Mediated Nephrotoxicity by Aptamer Nanomaterial Complementation. Current Nanoscience 2019, 15, 549–556. 10.2174/1573413715666190115155917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M; Liu S; Wei X; Wan S; Huang M; Song T; Lu Y; Weng X; Lin Z; Chen H; Song Y; Yang C. Aptamer Blocking Strategy Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infection. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60 (18), 10266–10272. 10.1002/anie.202100225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afrasiabi S.; Pourhajibagher M.; Raoofian R.; Tabarzad M.; Bahador A. Therapeutic applications of nucleic acid aptamers in microbial infections. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27 (1), 6. 10.1186/s12929-019-0611-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quang N. N.; Miodek A.; Cibiel A.; Ducongé F. Selection of Aptamers Against Whole Living Cells: From Cell-SELEX to Identification of Biomarkers. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1575, 253–272. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6857-2_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K. L.; Sooter L. J. Single-Stranded DNA Aptamers against Pathogens and Toxins: Identification and Biosensing Applications. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 419318. 10.1155/2015/419318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.-P.; Yang G.; Zhang X.-M.; Qu F. Development of Aptamer Screening against Proteins and Its Applications. Chinese J. Anal. Chem. 2020, 48 (5), 560–572. 10.1016/S1872-2040(20)60012-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devi S.; Sharma N.; Ahmed T.; Huma Z. I.; Kour S.; Sahoo B.; Singh A. K.; Macesic N.; Lee S. J.; Gupta M. K. Aptamer-based diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in animals: Current potential and challenges. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28 (9), 5081–5093. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N.; Chen Z.; Liu D.; Jiang H.; Zhang Z.-K.; Lu A.; Zhang B.-T.; Yu Y.; Zhang G. Structural Biology for the Molecular Insight between Aptamers and Target Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4093. 10.3390/ijms22084093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y.; Leslie M.; Kameyama H.; Volk D.; Tanaka T. Aptamer Therapeutics in Cancer: Current and Future. Cancers 2018, 10 (3), E80. 10.3390/cancers10030080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bompiani K. M.; Woodruff R. S.; Becker R. C.; Nimjee S. M.; Sullenger B. A. Antidote Control of Aptamer Therapeutics: The Road to a Safer Class of Drug Agents. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2012, 13 (10), 1924–1934. 10.2174/138920112802273137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R.; Keranen L. M.; Ellington A. D.; Newton A. C. Isozyme-specific Inhibition of Protein Kinase C by RNA Aptamer. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269 (51), 32051–32054. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)31598-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Rashid F.; Shah A.; Awan H. M.; Wu M.; Liu A.; Wang J.; Zhu T.; Luo Z.; Shan G. The isolation of an RNA aptamer targeting to p53 protein with single amino acid mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112 (32), 10002–10007. 10.1073/pnas.1502159112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Sun Q.-A.; Chen Q.; Lee T. H.; Huang Y.; Wetsel W. C.; Michelotti G. A.; Sullenger B. A.; Zhang X. Targeting inhibition of GluR1 Ser845 phosphorylation with an RNA aptamer that blocks AMPA receptor trafficking. J. Neurochem. 2009, 108 (1), 147–157. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira R. L.; Nascimento I. C.; Santos A. P.; Ogusuku I. E.; Lameu C.; Mayer G.; Ulrich H. Aptamers: Novelty tools for cancer biology. Oncotarget 2018, 9 (42), 26934–26953. 10.18632/oncotarget.25260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H.; Bruno J. G.; Kumar A.; Sharma T. K. Aptamers in the Therapeutics and Diagnostics Pipelines. Theranostics 2018, 8 (15), 4016–4032. 10.7150/thno.25958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H.; Liu J.; Ali M. M.; Mahmood M. A.; Labanieh L.; Lu M.; Iqbal S. M.; Zhang Q.; Zhao W.; Wan Y. Nucleic acid aptamers in cancer research, diagnosis and therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44 (5), 1240–1256. 10.1039/C4CS00357H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruigrok V.; Levisson M.; Eppink M.; Smidt H.; Van Der Oost J. Alternative affinity tools: More attractive than antibodies?. Biochem. J. 2011, 436 (1), 1–13. 10.1042/BJ20101860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.; Rossi J. J. Aptamers: Uptake mechanisms and intracellular applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 134, 22–35. 10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawiah K.; Porciani D.; Burke D. Toward the Selection of Cell Targeting Aptamers with Extended Biological Functionalities to Facilitate Endosomal Escape of Cargoes. Biomedicines 2017, 5 (4), 51. 10.3390/biomedicines5030051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povsic T. J.; Lawrence M. G.; Lincoff A. M.; Mehran R.; Rusconi C. P.; Zelenkofske S. L.; Huang Z.; Sailstad J.; Armstrong P. W.; Steg P. G.; Bode C.; Becker R. C.; Alexander J. H.; Adkinson N. F.; Levinson A. I. Pre-existing anti-PEG antibodies are associated with severe immediate allergic reactions to pegnivacogin, a PEGylated aptamer. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138 (6), 1712–1715. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A.; Pitoc G. A.; Ganson N. J.; Layzer J. M.; Hershfield M. S.; Tarantal A. F.; Sullenger B. A. Anti-PEG Antibodies Inhibit the Anticoagulant Activity of PEGylated Aptamers. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26 (5), 634–644.e3. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]