Abstract

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most devastating subtype of lung cancer with no clinically available prognostic biomarkers. N 6‐methyladenosine (m6A) and noncoding RNAs play critical roles in cancer development and treatment response. However, little is known about m6A‐related long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in SCLC. We used 206 limited‐stage SCLC (LS‐SCLC) samples from two cohorts to undertake the first and most comprehensive exploration of the m6A‐related lncRNA profile in SCLC and constructed a relevant prognostic signature. In total, 289 m6A‐related lncRNAs were screened out. We then built a seven‐lncRNA‐based signature in the training cohort with 48 RNA sequencing data using univariate and multivariate Cox regression models. The signature was well validated in an independent cohort containing 158 cases with quantitative PCR data. In both cohorts, the signature divided patients into high‐ and low‐risk groups with significantly different survival rates (both p < 0.001). Our signature predicted chemotherapy survival benefit in patients with LS‐SCLC. Receiver operating characteristic and C‐index analyses indicated that the signature was better at predicting prognosis and chemotherapy benefit than other clinicopathologic features. Moreover, the signature was identified as an independent predictor of prognosis and chemotherapy response in different cohorts. Furthermore, functional analysis showed that multiple activated immune‐related pathways were enriched in the low‐risk group. Additionally, the signature was also closely related to various immune checkpoints and inflammatory responses. We generated the first clinically available m6A‐related lncRNA signature to predict prognosis and chemotherapy benefit in patients with LS‐SCLC. Our findings could help optimize the clinical management of patients with LS‐SCLC and inform future therapeutic targets for SCLC.

Keywords: immune response, individualized medicine, lncRNA, N 6‐methyladenosine, small cell lung cancer

We established a seven m6A‐related lncRNAs signature with capacity to stratify the adjuvant chemotherapy response and prognostic risk of patients with SCLC. This signature showed similar prognostic values in different clinical subgroups and in an independent cohort with qPCR data. The potential mechanism and immune landscapes of the signature were explored by using bioinformatics methods.

Abbreviations

- ACT

adjuvant chemotherapy

- AUC

area under ROC curve

- ES

enrichment score

- FFPE

formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GSEA

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- GSVA

Gene Set Variation Analysis

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- lncRNA

long noncoding RNA

- LS‐SCLC

limited stage SCLC

- m6A

N 6‐methyladenosine

- ncRNA

noncoding RNA

- NES

normalized enrichment score

- OS

overall survival

- PD‐1

programmed cell death‐1

- PD‐L1

PD‐1 ligand

- qRT‐PCR

quantitative real‐time PCR

- RFS

recurrence‐free survival

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SCLC

small cell lung cancer

1. INTRODUCTION

Small cell lung cancer is a highly invasive, malignant, high‐grade neuroendocrine carcinoma with unparalleled growth and early metastases. 1 Currently, SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancer cases and is the leading cause of cancer‐related deaths worldwide. 1 , 2 Due to its elusive pathophysiology, prognosis for patients with SCLC is generally bleak. 3 , 4 , 5 The US NCI considers SCLC to be a recalcitrant cancer. 1 Given the dismal prognosis of patients with SCLC, more effective therapeutic targets are urgently needed.

N 6‐methyladenosine modification is the most prevalent and significant type of epigenetic methylated modification in mRNA and ncRNA. This modification regulates RNA export, splicing, stability, and translation. 6 N 6‐methyladenosine modification is a reversible and dynamic process controlled by specialized regulators, including methyltransferases (writers), demethylases (erasers), and binding proteins (readers). 7 N 6‐methyladenosine regulators are involved in the genesis and progression of multiple cancers. 8 Long noncoding RNAs—a subgroup of ncRNAs more than 200 nt in length—actively participate in the biological process regulated by m6A methylation tumors. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 The m6A reader YTHDF3 inhibits oncogenesis and tumor progression by negatively regulating the link between lncRNA GAS5 and YAP signaling in colorectal cancer 12 ; the m6A eraser ALKBH5 can sustain the expression of the lncRNA FOXM1, resulting in tumorigenicity and proliferation of glioblastoma cells. 11 The m6A writer METTL3 also mediates lncRNA MALAT1 stability to enhance and promote the invasion and spread of lung cancer cells. 13 Both m6A regulators and some lncRNAs have therapeutic potential and could serve as prognostic biomarkers across various malignancies. 14 , 15 , 16 There is a close interaction between m6A regulators and lncRNAs; they cooperate to modulate essential biological processes in tumorigenesis and development.

Despite these observations, the relationship between m6A regulators and aberrant lncRNA expression in SCLC remains largely unclear. Few have explored the underlying mechanisms of lncRNA‐dependent biological processes modulated by m6A modification in SCLC. Thus, determining how m6A regulatory elements and lncRNAs are linked in SCLC could help us to identify biomarkers as therapeutic targets and aid prognostication. We first identified the m6A‐related lncRNAs with prognostic value in patients with LS‐SCLC. Then we constructed a seven‐m6A‐related‐lncRNA signature in LS‐SCLC using bioinformatic methods. This signature precisely stratified ACT benefit and prognosis in patients with LS‐SCLC and was well‐validated in multiple clinical subgroups and with an independent qRT‐PCR dataset. We also explored the relationship between the signature and immune landscape in SCLC samples. This signature is the first molecular model associated with m6A modification and lncRNAs in SCLC to demonstrate precise and robust prognostic and predictive ability in patients with LS‐SCLC. These findings could help optimize precision medicine approaches for patients with LS‐SCLC and elucidate promising therapeutic targets in SCLC.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Samples and m6A‐related regulators

For the training cohort, we collected 79 patients diagnosed with SCLC and the corresponding microarray data from GSE65002. We analyzed the m6A regulator expression profiles between normal lung and LS‐SCLC tissues from GSE40275. Clinicopathological data were also downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus datasets (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). The validation set consisted of 158 patients with SCLC. All independent cohort cases underwent surgery for SCLC at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Hospital, 2009–2018; their corresponding FFPE tissues were used in this research. All patients provided informed consent for tissues collection. We determined the OS from the day of surgery to death or the last follow‐up and the RFS from the day of surgery to relapse, metastasis, or last follow‐up. We identified an additional 30 m6A regulators from recently published reports, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 including 11 writers (METTL3, METTL14, METTL16, METTL5, WTAP, VIRMA, RBM15, RBM15B, ZC3H13, CBLL1, and ZCCHC4), 2 erasers (FTO and ALKBH5), and 17 readers (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC1, YTHDC2, HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPC, FMR1, EIF3A, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, ELAVL1, G3BP1, G3BP2, PRRC2A, and RBMX). Patients' clinical information is presented in Table 1. The Ethics Committee Board of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Hospital approved this research.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients from different cohorts

| Characteristic | Training cohort (N = 48) | Validation cohort (N = 158) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| <60 | 27 (56.25%) | 84 (53.16%) |

| ≥60 | 21 (43.75%) | 74 (46.84%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 43 (89.58%) | 124 (78.48%) |

| Female | 5 (10.42%) | 34 (21.52%) |

| Smoking history | ||

| Yes | 33 (68.75%) | 99 (62.66%) |

| No | 15 (31.25%) | 59 (37.34%) |

| SCLC staging | ||

| I | 8 (16.67%) | 51 (32.28%) |

| II | 8 (16.67%) | 52 (32.91%) |

| III | 31 (62.50%) | 55 (34.81%) |

| IV | 1 (2.08%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| OS state | ||

| Alive | 25 (52.08) | 70 (44.30) |

| Death | 23 (47.92) | 88 (55.70) |

Note: Data are shown as n (%).

Abbreviation: OS, overall survival.

2.2. Identification of m6A‐related lncRNAs

We identified the lncRNA profile based on previously published studies. 21 We used the log2 transformation method to normalize the raw GSE60052 microarray data. We mapped the annotation file (GPL11154) with gene code v36 IDs; this screened out 2942 lncRNA transcripts with corresponding probes. We only included high‐expression lncRNAs in the subsequent analysis. Then we undertook Pearson's correlation analysis to identify the m6A‐related lncRNAs in the training cohort (with |r| > 0.5 and p < 0.0001). We ultimately identified 289 m6A‐related lncRNAs.

2.3. RNA extraction and qRT‐PCR

We used the Ambion RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit for FFPE (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to isolate the total RNA from FFPE SCLC tissues based on the manufacturer's protocols. We applied the NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to evaluate the quality and quantity of extracted RNA. We used a 10‐μl system which included 1 μl of each PCR primer, 1 μl cDNA, 3 μl nuclease‐free water, and 5‐μl SYBR in the 7900HT Fast Real‐Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). All validation and independent cohort samples were subjected to qRT‐PCR analysis. The expression of target m6A‐related lncRNAs was evaluated using the method. The primer sequences applied to this research are displayed in Table S1.

2.4. Biological pathway enrichment analysis and immune cell infiltration estimation

The GO and KEGG analyses were implemented in DAVID 6.8 (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp). In addition, GSEA was carried out to explore the underlying and relevant molecular mechanisms (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp).

2.5. Signature establishment and statistical analysis

We used univariate and multivariate Cox regression models to determine the m6A‐related lncRNAs most closely linked to prognosis and established a seven‐m6A‐related lncRNA signature.

R software (version 3.5.1; https://www.r‐project.org) and SPSS Statistics 25.0 software were used for statistical analysis and figure generation. Student's t‐test was utilized to evaluate the signature or clinicopathologic information‐based subgroups and prognostic outcomes in various cohorts. Kaplan–Meier curves and log–rank tests were applied to compare prognosis between low‐ and high‐risk groups. Gene Set Variation Analysis was carried out using the GSVA package in R software (version 3.5.1). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were undertaken to identify the independent predictor value of the seven‐m6A‐related lncRNA signature regarding OS. The R RMS package was used for these analyses. The ROC curves (the timeROC package) and AUC curves were used to assess the prognostic prediction capacity of the nomogram and other variables (TNM stage and risk score) for 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐year OS. A significant difference was defined as p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Screening prognostic m6A‐related lncRNAs in LS‐SCLC

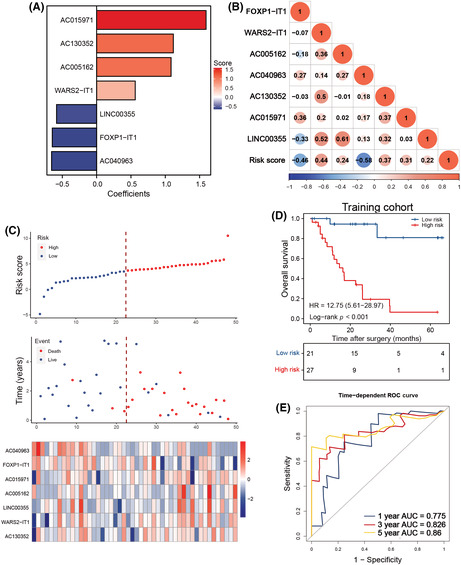

Considering the indispensable role of m6A regulators in tumorigenesis and progression, we investigated the m6A regulator expression profiles in normal lung and SCLC tissues. Based on the principal component analysis, we found that the expression patterns of these 30 regulators in normal lung and SCLC specimens were remarkably different (Figure 1A). The heatmap of different expression profiles between normal lung and SCLC cases is shown in Figure 1B; the corresponding expression pattern details are displayed in Figure S1. As m6A regulators actively participate in the development and progression of SCLC, we identified prognostic m6A‐related lncRNAs in LS‐SCLC.

FIGURE 1.

Filtering out the most prognostic N 6‐methyladenosine (m6A)‐related long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in small cell lung cancer (SCLC). (A) Principal component (PC) analysis of SCLC and normal lung tissues based on the expression profile of 30 m6A regulators in the GSE40275 cohort. (B) Heatmap of 30 m6A regulators' expression from GSE40275. (C) Forest plot of the association between m6A‐related lncRNAs and prognosis in SCLC from the training cohort. (D) Correlation between the selected m6A‐related lncRNAs and m6A regulators. * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, *** represents p < 0.001

The study flow is depicted in Figure S2. We reannotated 2942 lncRNAs from 79 patients with LS‐SCLC from the GSE60052 dataset after mapping the gene code v36 IDs to the annotation document. The GSE60052 with 79 samples was designated as the training cohort, and the corresponding clinical features are shown in Table 1. We also extracted 30 m6A regulator expression levels from 79 patients. To confirm the clinical significance of our analysis, we excluded lncRNAs with low expression levels (≥50% expression values were zero). Next, Pearson's correlation analysis was applied between the remaining 1202 lncRNAs and 30 m6A regulators in GSE65002. The lncRNA with Pearson |r| > 0.5 and p < 0.0001 was defined as the m6A‐related lncRNA. During this process, 289 m6A‐related lncRNAs were identified. To screen the prognostic m6A‐related lncRNAs, we implemented the univariate Cox regression analysis in 48 cases with survival information from GSE65002. Afterward, 19 m6A‐related lncRNAs were potentially associated with OS in patients with SCLC included from the GSE60052 dataset (Figure 1C, p < 0.2). Multivariate stepwise regression analysis was used to identify seven predictive m6A‐related lncRNAs in patients with LS‐SCLC. The m6A regulators associated with the seven m6A‐related lncRNAs are illustrated in Figure 1D.

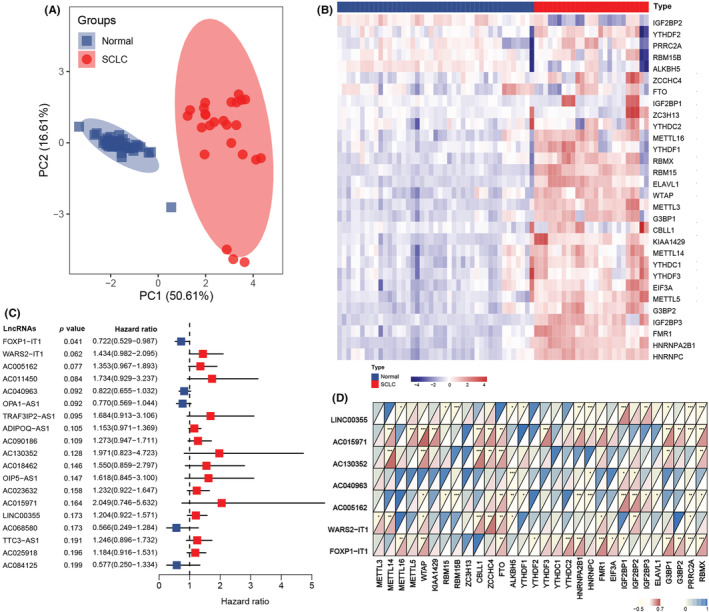

3.2. Establishment of m6A‐related lncRNAs in LS‐SCLC

We created an equation that consisted of the seven m6A‐related lncRNAs and their corresponding coefficients for risk stratification of patients with LS‐SCLC. Here, the risk score = (0.5622 × WARS2‐IT1 expression) + (1.0842 × AC005162 expression) + (1.1170 × AC130352 expression) + (1.5938 × AC015971 expression) − (0.6460 × FOXP1‐IT1 expression) − (0.0665 × AC040963 expression) − (0.5835 × LINC00355 expression) (Figure 2A). The relationship between 7 m6A‐related lncRNAs and the risk score is illustrated in Figure 2B. All patients in the training group were assigned a risk value and assigned to the high‐ or low‐risk groups based on the optimal cut‐off point (Figure 2C). Importantly, high‐risk patients had worse OS than low‐risk patients (Figure 2D). The ROC analysis produced AUC values of 0.775, 0.826, and 0.86 for forecasting OS in the GSE60052 cohort at 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐years, respectively (Figure 2E).

FIGURE 2.

Construction of the N 6‐methyladenosine (m6A)‐related long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) signature in the training cohort of patients with small cell lung cancer. (A) Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) coefficient profiles of the most useful prognostic m6A‐related lncRNAs. (B) Correlation between m6A‐related lncRNAs and risk score. (C) Risk score distribution with patient survival status in the training cohort; red indicates death, blue indicates survival. Expression distribution of the seven m6A‐related lncRNAs in the training cohort; red indicates higher expression, blue indicates lower expression. (D) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival in 48 patients of the training cohort based on risk score. (E) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of the m6A‐related lncRNA signature for prediction of survival at 1, 3, and 5 years in the training cohort. AUC, area under the ROC curve

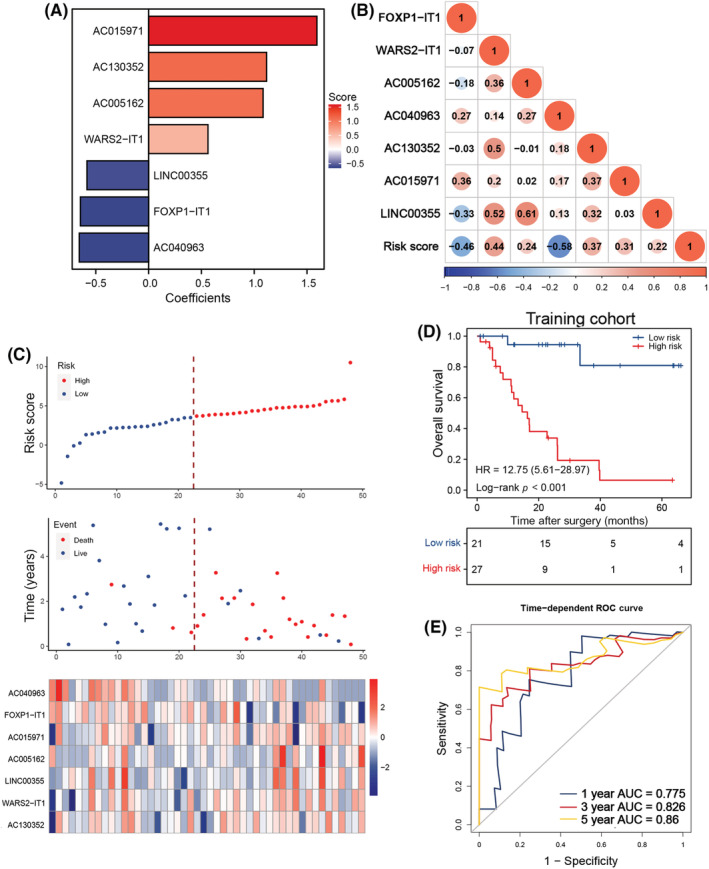

3.3. Validation of m6A‐related lncRNAs in LS‐SCLC

To further validate the prognostic performance of this signature, we included 158 FFPE samples from an independent validation set. We tested the expression levels of the seven m6A‐related lncRNAs in these 158 patients using a qRT‐PCR analysis. The cases were similarly assigned to low‐ or high‐risk groups based on individual risk scores. High‐risk patients showed a remarkably worse OS than low‐risk candidates (Figure 3A). The ROC curves analysis revealed that AUCs of this risk score in predicting 5‐year OS was 0.645 (Figure 3B). This m6A‐related lncRNAs signature could predict OS better than other critical clinical features (Figure 3C). Furthermore, we explored whether this m6A‐related lncRNA classifier effectively predicted the RFS of patients with LS‐SCLC. Intriguingly, high‐risk cases presented with significantly shorter RFS versus low‐risk patients (Figure 3D). We found the AUCs of this classifier predicting RFS at 5‐year was up to 0.666 (Figure 3E). This classifier also showed superior predictive performance in RFS than other clinical characteristics (Figure 3F).

FIGURE 3.

Validation and clinical application of the signature based on quantitative PCR data from an independent cohort of patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). (A) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) in 158 patients of the independent cohort based on risk score. (B) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of risk score and multiple clinical characteristics for OS in the independent cohort. (C) C‐index values of risk score and different clinical parameters for OS in patients of the independent cohort. (D) Kaplan–Meier curves of recurrence‐free survival (RFS) in 158 patients of the independent cohort based on risk score. (E) ROC analysis of risk score and multiple clinical characteristics for RFS in the independent cohort. (F) C‐index values of risk score and different clinical parameters for RFS in patients of the independent cohort. (G) Kaplan–Meier curves of OS in the adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) subgroup of the independent cohort based on risk score. (H) ROC analysis of risk score and multiple clinical characteristics for OS in the ACT subgroup of the independent cohort. (I) C‐index values of risk score and different clinical parameters for OS in the ACT subgroup of the independent cohort. (J) Kaplan–Meier curves of RFS in the ACT subgroup of the independent cohort based on risk score. (K) ROC analysis of risk score and multiple clinical characteristics for RFS in the ACT subgroup of the independent cohort. (L) C‐index values of risk score and different clinical parameters for RFS in the ACT subgroup of the independent cohort. AUC, area under the ROC curve; HR, hazard ratio

Considering the pivotal role of ACT in SCLC treatment, we tested the predictive ability of this m6A‐related lncRNA signature to ACT response in patients with LS‐SCLC. In the independent cohort, 138 of 154 cases received ACT, and the risk score categorized them into high‐ and low‐risk groups based on the optimal cut‐off point. Low‐risk cases benefited more from ACT treatment than their high‐risk counterparts, achieving longer OS and RFS (Figure 3G,J). The signature AUCs for predicting 1‐, 3‐, and 5‐year OS and RFS are displayed in Figure 3H,K. Importantly, the signature was a better predictor of 5‐year OS and RFS than other clinical features (Figure 3I,L). We also validated the predictive capacity of the risk score in clinical features (sex, age, smoking status, and disease stage) subgroups from the independent cohort. Once again, low‐risk patients achieved better OS and RFS within the clinical characteristic subgroups (Figures S3 and S4).

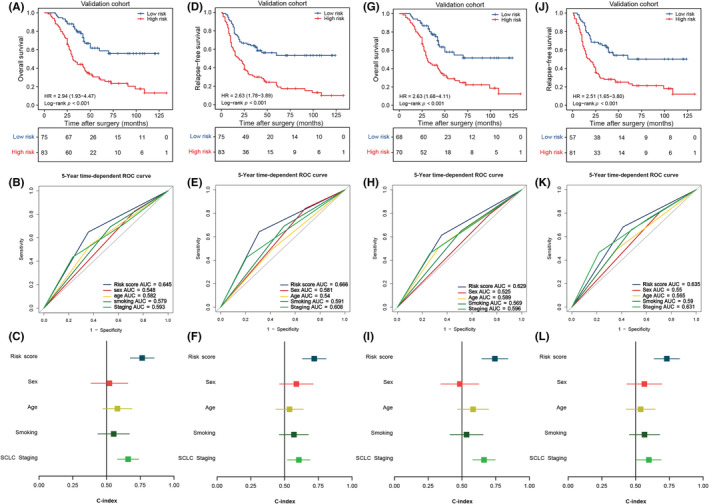

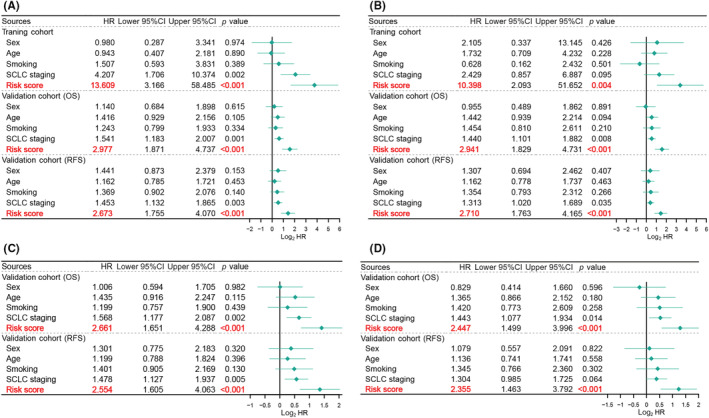

3.4. N 6‐methyladenosine‐related lncRNA signature is an independent prognostic factor for patients with LS‐SCLC

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to determine whether our m6A‐related lncRNA signature could independently predict prognosis in patients with SCLC. Our signature was superior to other clinical features (sex, age, smoking status, and SCLC staging) for predicting OS and RFS among patients with LS‐SCLC (Figure 4A). After including these clinical features, the multivariate Cox analysis confirmed the m6A‐related lncRNAs independently predicted OS and RFS in patients with LS‐SCLC in the training and independent cohorts (Figure 4B). Additionally, we sought to determine whether this classifier could serve as an independent predictor of ACT efficacy in LS‐SCLC. Consistent with the previous results, the model independently forecasted OS and RFS in patients receiving ACT from the independent cohort (Figure 4C,D). Our signature independently predicted ACT efficacy and prognosis among patients with LS‐SCLC; thus, we believe our signature could assist with clinical management of these patients.

FIGURE 4.

Risk score independently predicted the survival and chemotherapy benefit in both cohorts of patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). (A) Univariate Cox regression analyses of risk score and multiple clinical characteristics in the training and independent cohorts. (B) Multivariate Cox regression analyses of risk score and multiple clinical characteristics in the training and independent cohorts (C) Univariate Cox regression analyses of risk score and multiple clinical characteristics in the adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) subgroup of the independent cohort. (D) Multivariate Cox regression analyses of risk score and multiple clinical characteristics in the ACT subgroup of the independent cohort. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence‐free survival

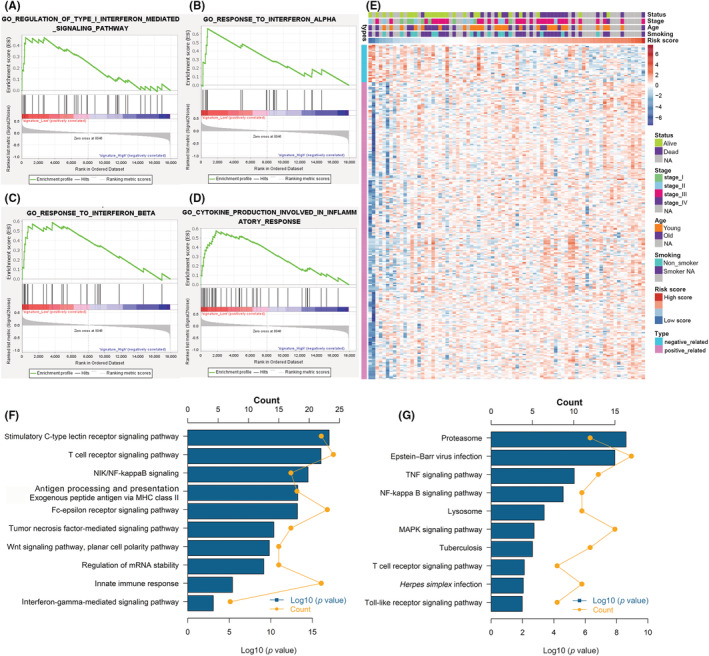

3.5. Functional analysis of m6A‐related lncRNA signature

The GSEA was carried out to discover the potential mechanisms of the signature. Several immune‐related pathways were enriched in the low‐risk group, including those involved in cytokine production for the inflammatory response (ES = 0.5748, NES = 1.6625, p =< 0.001), regulation of type I interferon‐mediated signaling pathway (ES = 0.4695, NES = 1.6175, p = 0.0205), and response to interferon β (ES = 0.5852, NES = 1.6699, p = 0.0212) and α (ES = 0.6612, NES = 1.7345, p < 0.001) (Figure 5A–D). Thus, the signature was correlated with tumor immunity. Therefore, we closely examined the relationship between this signature and immune genes. The immune genes with Pearson |r| > 0.3 were considered to be correlated with this signature, and finally 277 immune genes were identified. The resultant heatmap of these immune genes and various clinical features of cases from the GSE60052 dataset is presented as Figure 5E. The GO and KEGG analyses were used to identify the underlying biological functions. Our risk score was closely associated with various immune responses processes, such as the T‐cell receptor signaling pathway, antigen processing and presentation of exogenous peptide antigens through MHC class II, tumor necrosis factor‐mediated signaling pathway, the nuclear factor‐kappa B signaling pathway, and the Toll‐like receptor signaling pathway (Figure 5F,G). This m6A‐related lncRNA signature is linked to immune responses and biological processes and provides insights into tumor immunity in SCLC.

FIGURE 5.

Functional analysis of the risk score in the training cohort of patients with small cell lung cancer. (A–D) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis indicated a significantly immune phenotype in the low‐risk cases. (E) Details of risk score and the most relevant immune‐related genes. (F) Gene enrichment with Gene Ontology (GO) terms of the selected genes. (G) Gene enrichment with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes terms of the selected genes. NA, not available; NF‐kappa B, nuclear factor‐kappa B; TNF, tumor necrosis factor

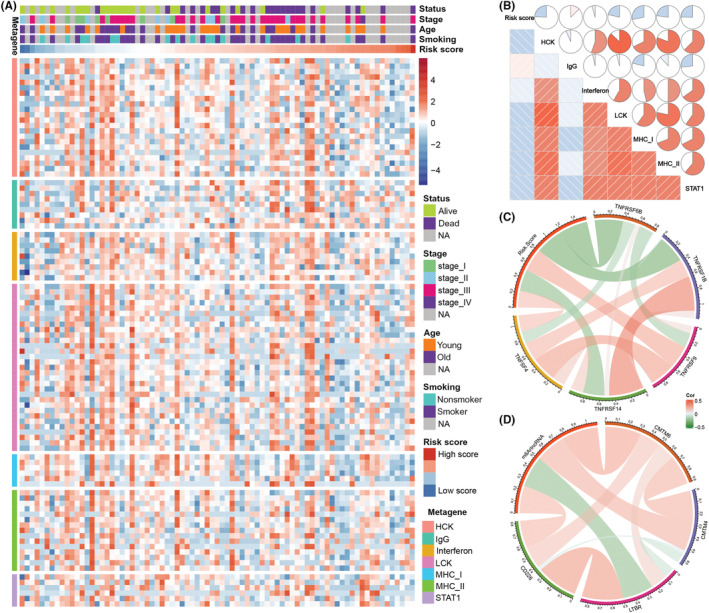

3.6. Immune landscape of m6A‐related lncRNA signature

We applied the seven clusters metagenes (HCK, interferon, LCK, MHC‐I, MHC‐II, IgG, and STATA) to further validate the relationship between this signature and tumor immunity relative to various inflammatory and immune responses (Figure 6A). The risk score was positively correlated with the IgG cluster, and negatively correlated with the HCK, LCK, MHC‐I, MHC‐II, and STAT1 clusters (Figure 6B). The GSVA results agreed with our prior findings. Low‐risk patients were more likely to be associated with T cell signaling transduction and macrophage activation.

FIGURE 6.

Relationships between the risk score, immune metagenes, and immune checkpoints in patients with small cell lung cancer. (A) Expression of metagenes and the risk score in the training cohort. (B) Corrgram of risk score and the cluster of seven metagenes in the training cohort. (C, D) Correlation between risk score and immune checkpoint expression. NA, not available

Immune checkpoints are an important component of the tumor immune microenvironment and directly influence the antitumor response. Thus, we also tested the relationship between risk score and the expressions of various immune checkpoints. The risk score was positively related to various immune checkpoint expression levels in the training cohort, including TNFRSF4, TNFRSF9, CMTM4, CMTM6, and CD226 (Figure 6C,D). Most of these immune checkpoints are promising therapeutic targets for immunotherapies. High‐risk patients could benefit from emerging therapies that target these immune checkpoints.

4. DISCUSSION

Past studies have indicated that m6A modification actively participates in tumor pathogenesis and progression. Several m6A regulators modulate the progression of multiple malignancies by affecting the degradation, stability, expression, and translation of different lncRNAs.

For example, the m6A writer METTL3 accelerates tumor invasion and metastasis in lung cancer by modifying the stability of the lncRNA MALAT1. Similarly, METTL14 restrains the development and progression of colon cancer by decreasing the lncRNA XIST. The m6A eraser ALKBH5 enhances the expression of the lncRNA FOXM1, maintaining the stemness of glioblastoma cells. N 6‐methyladenosine modification of lncRNAs can regulate various tumor‐related biological processes and affect tumor development; substantial lncRNAs might act as competing endogenous RNAs. Therefore, m6A regulators could emerge as targets for tumor elimination. While lncRNAs are the essential targets of (and closely associated with) m6A modification, few studies have examined m6A modification of lncRNAs in SCLC. The links between m6A regulators and lncRNAs in SCLC could help us identify potential prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

In this study, we aimed to explore the m6A‐related lncRNA expression profile and its clinical significance in LS‐SCLC. We also constructed a seven m6A‐related lncRNA signature that could precisely predict ACT efficacy and prognostic risk for patients with LS‐SCLC. Our signature also showed better predictive ability than other clinical characteristics. This m6A‐related lncRNA classifier was well validated in the various clinical subgroups and the independent cohort, and served as an independent prognostic predictor in LS‐SCLC. We believe that our findings could help optimize the clinical precision management for patients with SCLC and shed some light on the therapeutic targets in SCLC.

Interestingly, this m6A‐related lncRNA signature consisted of three protective factors (FOXP1‐IT1, AC040963, and LINC00355) and four risk‐enhancing factors (WARS2‐IT1, AC005162, AC130352, and AC015971). FOXP1‐IT1 is significantly downregulated in ovarian cancer and is associated with a better prognosis for colon adenocarcinoma. 22 , 23 LINC00355 is a pro‐oncogene factor and upregulated in various cancers. It promotes tumor proliferation, migration, and invasion by regulating multiple microRNA axes or epigenetic modification in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, lung cancer, and gastric cancer. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 Importantly, the exosomal LINC00355 enhances the resistance of bladder cancer cells to chemotherapy by its interaction with the microRNA axis. 28 WARS2‐IT1 promotes tumor growth and is associated with an unfavorable prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. 29 AC005162 could accelerate tumor growth and worsens prognosis for patients with breast cancer. 30 However, little is known about the roles of AC040963, AC130352, or AC015971; further studies are needed determine their function. The specific functions of the seven m6A‐related lncRNAs relative to SCLC development warrants further exploration.

The m6A‐related molecular model appears closely linked to various immune‐related pathways, including cytokine production involved in the inflammatory response, regulation of type I interferon‐mediated signaling pathway, and the responses to interferon β and α. Low‐risk patients showed different forms of immune phenotype activation than high‐risk patients. Some essential immune response processes were linked to this molecular model—including the T‐cell receptor signaling pathway, antigen processing and presentation of exogenous peptide antigen through MHC class II, the tumor necrosis factor‐mediated signaling pathway, the nuclear factor‐kappa B signaling pathway, and the Toll‐like receptor signaling pathway. Collectively, this signature appears to be actively involved in tumor immunity.

Notably, various immune checkpoints (TNFRSF4, TNFRSF9, CD226, CMTM4, and CMTM6) expression emerged as relevant to this risk score. TNFRSF4 and TNFRSF9, TNF receptor superfamily candidates, actively participate in co‐stimulatory and co‐inhibitory signaling of specific immunity. Harnessing TNFRSF members can increase tumor immunity, and relevant preclinical studies and clinical trials are being carried out. 31 , 32 CD226 is a critical activator of natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells to mediate the immune reactivity against cancer; additionally, CD226 can affect the efficacy of PD‐1/PD‐L1 blockade therapy. 33 CMTM4 and CMTM6 mediate PD‐L1 protein expression and function, enhancing tumor cells with high expression of PD‐L1 to weaken T cell‐dominated antitumor effects. 34 These results could guide future clinical application of immunotherapies for SCLC.

Investigations of prognostic biomarkers for SCLC have been impeded due to difficulties obtaining SCLC samples under standard care conditions. Our study was the first large‐cohort, lncRNA‐related research in LS‐SCLC. Before our study, several researchers constructed molecular models to predict the prognostic risk of patients with SCLC, which is mostly limited in mRNAs and microRNAs with small size of samples. 35 , 36 This was the first time the lncRNA expression profile for LS‐SCLC was identified; we constructed an m6A‐related lncRNA‐based signature to predict ACT responses and prognosis in patients with LS‐SCLC.

Our results should be considered within the context of several study limitations. First, the lncRNA expression profile was primarily decided by GPL11154; this might not include all lncRNAs identified to date. Second, despite our best efforts to collect validation samples, our model requires validation within a larger study cohort. Finally, our retrospective results should be confirmed within the context of future, prospective studies.

In summary, we determined the expression profile of m6A‐related lncRNAs in SCLC and established a seven‐m6A‐related lncRNA‐based molecular model to forecast chemotherapy response and prognostic risk for patients with SCLC. Our results could inform future clinical applications of chemotherapy and immunotherapy in patients with SCLC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

NS and JH supervised the project, designed, edited and led out the experiments of this study. YJL, ZHZ, and PW conducted the experiments and data analysis. YJL and ZHZ prepared all the figures and tables. YJL, ZHZ, and BZ drafted the manuscript. GCZ, LDW, QPZ, ZYY, LYX, HZ, FWT, QX, and SGG collected clinical samples and provided material support. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2017‐I2M‐1‐005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81802299, 81502514), Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities (3332018070), the National Key Basic Research Development Plan (2018YFC1312105), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7204291), and Beijing Hope Run Special Fund of Cancer Foundation of China (LC2019B18).

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1

Figure S2

Figure S3

Figure S4

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All authors would like to thank the specimen donors used in this study, and the research groups that provided data for this collection. All authors would also like to thank CapitalBio Technology for their kind help.

Luo Y, Zhang Z, Zheng B, et al. Comprehensive analyses of N 6‐methyladenosine‐related long noncoding RNA profiles with prognosis, chemotherapy response, and immune landscape in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2022;113:4289‐4299. doi: 10.1111/cas.15553

Yuejun Luo, Zhihui Zhang, and Bo Zheng equal contributors.

Contributor Information

Nan Sun, Email: sunnan@vip.126.com.

Jie He, Email: prof.jiehe@gmail.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Developing new, rational therapies for recalcitrant small cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(10):djw119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA, De Ruysscher DK. Small‐cell lung cancer. Lancet (London, England). 2011;378(9804):1741‐1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nicholson AG, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the clinical and pathologic staging of small cell lung cancer in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(3):300‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lara PN Jr, Natale R, Crowley J, et al. Phase III trial of irinotecan/cisplatin compared with etoposide/cisplatin in extensive‐stage small‐cell lung cancer: clinical and pharmacogenomic results from SWOG S0124. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2530‐2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rossi A, Di Maio M, Chiodini P, et al. Carboplatin‐ or cisplatin‐based chemotherapy in first‐line treatment of small‐cell lung cancer: the COCIS meta‐analysis of individual patient data. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1692‐1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pan T. N6‐methyl‐adenosine modification in messenger and long non‐coding RNA. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38(4):204‐209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dawson MA. The cancer epigenome: concepts, challenges, and therapeutic opportunities. Science. 2017;355(6330):1147‐1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen XY, Zhang J, Zhu JS. The role of m(6)A RNA methylation in human cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lan T, Li H, Zhang D, et al. KIAA1429 contributes to liver cancer progression through N6‐methyladenosine‐dependent post‐transcriptional modification of GATA3. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patil DP, Chen CK, Pickering BF, et al. m(6)A RNA methylation promotes XIST‐mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 2016;537(7620):369‐373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, et al. m(6)A demethylase ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem‐like cells by sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(4):591‐606.e596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ni W, Yao S, Zhou Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA GAS5 inhibits progression of colorectal cancer by interacting with and triggering YAP phosphorylation and degradation and is negatively regulated by the m(6)A reader YTHDF3. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jin D, Guo J, Wu Y, et al. m(6)A mRNA methylation initiated by METTL3 directly promotes YAP translation and increases YAP activity by regulating the MALAT1‐miR‐1914‐3p‐YAP axis to induce NSCLC drug resistance and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14. Tu Z, Wu L, Wang P, et al. N6‐methylandenosine‐related lncRNAs are potential biomarkers for predicting the overall survival of lower‐grade glioma patients. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang C, Zhang Z, Zhang G, et al. A three‐lncRNA signature of pretreatment biopsies predicts pathological response and outcome in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(4):e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Q, Chen C, Ding Q, et al. METTL3‐mediated m(6)A modification of HDGF mRNA promotes gastric cancer progression and has prognostic significance. Gut. 2020;69(7):1193‐1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li Y, Xiao J, Bai J, et al. Molecular characterization and clinical relevance of m(6)A regulators across 33 cancer types. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu J, Harada BT, He C. Regulation of gene expression by N(6)‐methyladenosine in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29(6):487‐499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang H, Weng H, Chen J. m(6)A modification in coding and non‐coding RNAs: roles and therapeutic implications in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(3):270‐288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nombela P, Miguel‐López B, Blanco S. The role of m(6)A, m(5)C and Ψ RNA modifications in cancer: novel therapeutic opportunities. Mol Cancer. 2021;20(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu X, Tian X, Yu C, et al. A long non‐coding RNA signature to improve prognosis prediction of gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2016;15(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruan L, Xie Y, Liu F, Chen X. Serum miR‐1181 and miR‐4314 associated with ovarian cancer: miRNA microarray data analysis for a pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;222:31‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jin L, Li C, Liu T, Wang L. A potential prognostic prediction model of colon adenocarcinoma with recurrence based on prognostic lncRNA signatures. Hum Genomics. 2020;14(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lu S, Sun Z, Tang L, Chen L. LINC00355 promotes tumor progression in HNSCC by hindering microRNA‐195‐mediated suppression of HOXA10 expression. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:61‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25. Zhou F, Lei Y, Xu X, et al. LINC00355:8 promotes cell proliferation and migration with invasion via the MiR‐6777‐3p/Wnt10b axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2020;11(19):5641‐5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liang Y, Rong X, Luo Y, et al. A novel long non‐coding RNA LINC00355 promotes proliferation of lung adenocarcinoma cells by down‐regulating miR‐195 and up‐regulating the expression of CCNE1. Cell Signal. 2020;66:109462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhao W, Jin Y, Wu P, et al. LINC00355 induces gastric cancer proliferation and invasion through promoting ubiquitination of P53. Cell Death Discov. 2020;6:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 28. Luo G, Zhang Y, Wu Z, Zhang L, Liang C, Chen X. Exosomal LINC00355 derived from cancer‐associated fibroblasts promotes bladder cancer cell resistance to cisplatin by regulating miR‐34b‐5p/ABCB1 axis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2021;53(5):558‐566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yue C, Ren Y, Ge H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of potential prognostic genes for the construction of a competing endogenous RNA regulatory network in hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:561‐576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao H, Liu X, Yu L, et al. Comprehensive landscape of epigenetic‐dysregulated lncRNAs reveals a profound role of enhancers in carcinogenesis in BC subtypes. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;23:667‐681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ma Y, Li J, Wang H, et al. Combination of PD‐1 inhibitor and OX40 agonist induces tumor rejection and immune memory in mouse models of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):306‐319.e312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buchan SL, Rogel A, Al‐Shamkhani A. The immunobiology of CD27 and OX40 and their potential as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Blood. 2018;131(1):39‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weulersse M, Asrir A, Pichler AC, et al. Eomes‐dependent loss of the co‐activating receptor CD226 restrains CD8(+) T cell anti‐tumor functions and limits the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Immunity. 2020;53(4):824‐839.e810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mezzadra R, Sun C, Jae LT, et al. Identification of CMTM6 and CMTM4 as PD‐L1 protein regulators. Nature. 2017;549(7670):106‐110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Song Y, Sun Y, Sun T, Tang R. Comprehensive bioinformatics analysis identifies tumor microenvironment and immune‐related genes in small cell lung cancer. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2020;23(5):381‐391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bi N, Cao J, Song Y, et al. A microRNA signature predicts survival in early stage small‐cell lung cancer treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Figure S2

Figure S3

Figure S4

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.