Abstract

While SalaC is a potent marine cytotoxin, Kashman demonstrated that congeners which had undergone Wasserman rearrangement exhibit little to no cytotoxicity. Given that thiazoles are known to undergo Wasserman rearrangement at a significantly reduced rate, we hypothesized that a thiazole-containing SalaC would exhibit greater stability without significantly altering the macrocyclic conformation. Herein, we describe the synthesis of a simplified, thiazole-containing macrocycle which demonstrates significantly improved stability under identical aerobic conditions.

Graphical Abstract

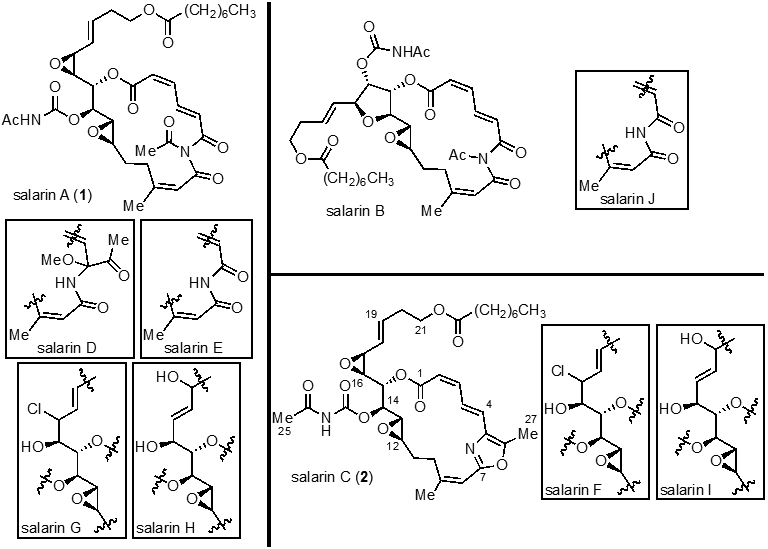

The salarins are a family of macrocyclic, marine natural products isolated in 2007 by Kashman and coworkers from the Fascaplysinopsis sp. sponge collected in Salary Bay, Madagascar.1-6 In addition, three other families of nitrogenous macrolides, tulearins5, taumycins3, and tausalarins, have also been isolated from this sponge.6 Bioactivity-guided purification of the CHCl3-MeOH extract using a brine shrimp assay led to the initial isolation of two salarins, A (SalaA) and B (SalaB).1 These natural products possess a highly unsaturated N-acetyl imide within a macrocycle and one or two epoxides, including an allylic epoxide in the case of SalaA, and an N-acetyl carbamate moiety. Another collection of this sponge revealed the presence of a related compound salarin C (SalaC),2 which showed very potent inhibition of cell proliferation. SalaC contains an oxazole ring in place of the N-acetyl imide found in SalaA (1). Finally, Kashman also isolated seven additional salarins (D-J) in 2010,4 which were related but distinct congeners of the previously isolated family members (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structures of salarins A-J (SalaA-J) with SalaD-J represented as partial structures. The relative stereochemistry of diols and chlorohydrins in SalaG, H, F, and I is unknown.

SalaC (2) exhibits the most potent cytotoxic activity of all salarins with an EC50 of 0.1 μM and 1 μM toward a chronic myelogenous leukemia (K562) and an acute myeloid leukemia (UT-7) cell line, respectively. SalaC induces cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and leads to induction of apoptosis.7 All other members of the salarin family devoid of either the allylic C16/17-epoxide, such as SalaB, F, I, or the oxazole-containing macrocycle, such as the rearranged N-acetylimide SalaA, D, E, exhibit greatly reduced or no cytotoxicity. Furthermore, Kashman also conducted a series of derivatization experiments of SalaC and found that all derivatives involving C16/17 epoxide cleavage led to loss of cytotoxicity.8 Taken together, this preliminary SAR data suggest that the presence of the allylic C16/17-epoxide and the overall conformation of the oxazole-containing macrocycle are essential for bioactivity.

SalaC exhibits a pronounced instability to ambient singlet oxygen (1O2) which leads to conversion of the SalaC oxazole to the N-acetyl imide found in SalaA (Scheme 1).9,10 Interestingly, the concentration of ambient 1O2 can be as high as 20 ppb during the daytime in the outdoors.11 While we briefly considered the possibility that SalaC could itself be a photosensitizer, we concluded that this was unlikely due to SalaC’s reported λmax (329 nm, MeOH)2 being much lower than most common photosensitizers (~560-660 nm, e.g. rose bengal and methylene blue).12 Kashman proposed that this occurs through a Wasserman rearrangement,2 a transformation enabling the use of oxazoles as latent activated carboxyl groups.10 Lindel synthesized a linear conjugated oxazole fragment structurally related to that found in the macrocycle of SalaC and determined that it was stable to aerobic conditions.13 However, upon exposure to photochemically-generated 1O2, the corresponding N-acetyl imide was obtained. Subsequently, Altmann reported synthetic studies towards SalaC and observed that synthetic intermediates became reactive toward 1O2 once the macrocycle is formed. However, they were able to synthesize dideoxy-SalaC devoid of the allylic C16/17-epoxide.14,15 Molecular modeling, cross-ring nOe’s observed by Kashman2 (H4→H10, H12→H16, H4→H16) and the expected planarity of the dienoate to maximize conjugation, all point to a strained macrocycle in SalaC. We propose that torsional strain induced by the rigid SalaC macrocycle leads to a higher energy HOMO for the conjugated oxazole and greater strain release16 resulting in a rate acceleration of the Wasserman rearrangement.

Scheme 1.

Aerobic instability of SalaC (2) toward 1O2 leading to SalaA (1) via a Wasserman rearrangement.

McNeill demonstrated that peptidic thiazoles are much less susceptible to the Wasserman rearrangement compared to their oxazole counterparts.17 The increased stability might be expected in part due to increased aromaticity of thiazoles compared to oxazoles, as evidenced by isotropic magnetic shielding distributions18 and chemical shift differences. We reasoned that a thiazole-containing SalaC macrocycle would be more stable toward 1O2. We thus set out to synthesize a simplified macrocycle bearing a thiazole and compare its stability to the corresponding simplified oxazole SalaC macrocycle. The C12/13-trans-epoxide would be replaced with an equivalent, conformationally-biasing trans-alkene. We also reasoned that removal of the SalaC side-chain and C14-oxygenation would have minimal effect on the conformation of the macrocycle. Indeed, computational studies demonstrated that the low energy conformations of the two macrocycles 3a, 3b are quite similar (Figure 2b) with negligible changes in planarity but expected changes in bond lengths and angles between these heterocycles (Figure 2c). This is a common heterocycle interchange performed in medicinal chemistry, thus we anticipated minimal effect on bioactivity of an eventual fully elaborated thia-SalaC variant.19 While our work was in progress, Lindel reported the synthesis of the identical simplified oxazole macrocycle 3b.20 However, they only studied its reactivity to 1O2 under photolytic conditions with rose bengal. Herein, we describe the synthesis of both a simplified, thiazole-containing SalaC macrocycle 3a and the analogous oxazole-containing macrocycle 3b for comparison. The intrinsic reactivity of these macrocycles toward ambient 1O2 was also studied under various conditions as a prelude to further synthetic and mechanism of action studies.

Figure 2.

(a) Structures of simplified thiazole- and oxazole-containing macrocycles 3a, b. (b) Overlay of minimized lowest energy conformations (B3LYP/6-31G) of the two macrocycles (oxazole 3b, green; thiazole 3a, gold) showing minimal change in lowest energy conformations. (c) Close-up views of the thiazole and oxazole overlays with two different perspectives.

Our proposed syntheses of the two, simplified macrocycles 3a, 3b employed similar disconnections for simplicity with an eye towards scalable routes that could potentially be modified to access derivatives of thia-SalaC (Scheme 2). Key steps in our synthesis ultimately included formation of the thiazole and oxazole through cyclodehydration and oxidation, a sp2-sp3 Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, successfully utilized by Altmann toward SalaC,11 a cationic Heck reaction to install the required Z,E-dienoate, and a final macrolactonization.

Scheme 2.

Simplification of SalaC and retrosynthesis of thiazole and oxazole-SalaC macrocycles 3a and 3b.

The synthesis of the simplified thiazole macrocycle 3a commenced with (Z)-vinyl iodide 9 (Scheme 3), available in one step with high selectivity (>19:1 Z/E) from commercially available 2-butynoic acid (Scheme 3).21 Carboxylic acid 9 was then coupled with threonine benzyl ester by in situ conversion to the acid chloride to deliver amide 10 in 87% yield (>19:1 Z/E). Subsequent treatment with Lawesson’s reagent gave the corresponding thioamide.22 Cyclodehydration to the thiazoline was accomplished by conditions first described by Williams employing Deoxo-Fluor®23 and later converted to flow format by Ley.24 Flow conditions were employed to access the intermediate thiazoline. Typical conditions to oxidize the thiazoline (BrCCl3, DBU)25 to the thiazole were unsuccessful due to the base sensitivity of the vinyl iodide, resulting in elimination of HI to reform the alkyne. We instead attempted a much milder radical oxidation developed by Meyers based on the Kharasch-Sosnovsky reaction26,27 which delivered the desired thiazole vinyl iodide 8a with minimal isomerization of the C8,9-alkene over the 3-step sequence integrity (13:1 Z/E). The known alkyl iodide 7, available in four steps from commercially available β-hydromuconic acid,28 was subjected to lithium-halogen exchange and subsequent borylation with 9-MeO-9-BBN enabling a one-pot Suzuki sp2-sp3 cross-coupling29 with vinyl iodide 8a.14,30 This coupling proceeded efficiently and without alkene isomerization but was most easily purified following subsequent reduction of the benzyl ester with DIBAl-H and oxidation to deliver aldehyde 12 in 49% overall yield (3 steps).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of a simplified thiazole-containing SalaC macrocycle 3a.

Wittig olefination and subsequent cationic Heck coupling with known Z-3-iodoacrylic methyl ester 631 delivered the (2Z, 4E)-dienoate 13 in 77% yield proceeding with high stereoselectivity (>19:1, 2Z).32 However, significant isomerization of the C8,C9 alkene was observed under Heck coupling conditions (8:1 Z/E). Careful control of stoichiometry was also essential to preventing additional Heck coupling to the C12, 13-alkene. This side-product could be completely avoided by syringe pump addition of the β-iodo acrylate 6 as a solution in degassed MeCN over 1 h. Following desilylation with TBAF, we serendipitously found that during attempts to saponify the methyl ester with TMSOK,33 the desired macrocycle could be detected by NMR and thus we set out to optimize this macrocyclization. Altmann also utilized TMSOK for hydrolysis of their seco ester but did not observe macrocyclization, perhaps because their substrate bore a pendant secondary rather than primary alcohol as in our seco ester.14 We anticipated that the (Z)-C8,9-alkene isomer might undergo macrocyclization at a faster rate than the undesired (E)- alkene. However, following optimization involving use of a large excess of TMSOK, high dilution, and shorter reaction times, two isomeric macrocycles (3a) were obtained in the same ratio of C8,C9-geometrical isomers as the seco ester substrates. Separation of the alkene isomers was accomplished by preparative HPLC for characterization and subsequent stability studies.

For comparative stability studies, we also synthesized a simplified, oxazole-containing SalaC macrocycle 3b (Scheme 4). The synthesis mirrored that of the thiazole variant with a few notable challenges including more facile C8, C9-alkene (SalaC numbering) isomerization. Substantial isomerization of the C8,9-alkene in vinyl iodide 8b was observed during the Karasch-Sosnovsky oxidation of the oxazoline to oxazole (from >10:1 to 2:1 Z/E). We thus studied a number of known oxidation methods for this transformation (MnO2;34 DDQ; NBS/hν;35 CuBr/peroxide26) which offered no improvement. Several studies were undertaken to minimize isomerization without success thus the inseparable mixture of C8,C9-alkene geometrical isomers (Z/E, 2:1) was taken through the remainder of the sequence with the expectation that separation would be possible upon macrocyclization as with the thiazole macrocycle (vide supra). One outcome of the optimization studies was development of a serviceable, albeit very slow, in situ hydroboration-Suzuki-Miyaura coupling sequence. which, following direct reduction, afforded alcohol 16 in 39% yield (2 steps). Alcohol 16 was oxidized to the corresponding aldehyde with Dess-Martin reagent37 rather than MnO2 since the latter oxidation conditions led to reduced yields and further C8,9-alkene isomerization. Wittig reaction and Heck coupling of the derived alkene 17 with (Z)-vinyl iodide 6 delivered ester 18 with high selectivity for the (Z)-C4,5-alkene (>19:1). Silyl group deprotection and treatment with TMSOK also led to serviceable yields of the macrocyclic oxazole 3b as a 3:1 mixture of C8,C9-isomeric alkenes. Enrichment of the Z- alkene isomer was achieved through preparative HPLC purification to provide macrocycle 3b (15:1 Z/E; C8,C9) which correlated well to the same macrocycle described by Lindel.20

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of a simplified oxazole-containing, SalaC macrocycle 3b as a comparator.

Toward understanding the stability of these macrocycles when collecting NMR data of synthetic intermediates following macrocyclization and diluting samples for biological studies, we measured half-lives of macrocycles 3a, 3b, and the linear oxazole seco ester 4b as a comparator, under various conditions in CDCl3 and DMSO-d6. We also studied the stability of macrocycles in CD3OD under one set of conditions to approximate water. The rate of degradation of macrocycles 3a,3b and seco ester 4b to both Wasserman rearrangement and isomerization was monitored by 1H NMR through integration of HC4 and HC15 in comparison to an internal standard (1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene). As expected, in an argon flushed (AF), 5 mm regular glass NMR tube (RGT), with storage between NMR analyses on the lab bench (LB), no reaction (NR) was observed for macrocycles 3a, 3b or seco ester 4b in DMSO-d6 after 21 days. (Table 1, Conditions #1). These conditions were thus not further explored in CDCl3 or CD3OD. Likewise, rearrangement was not observed with any compounds in 5 mm amber tubes (AT) in CDCl3, open to ambient air (OA), with storage between NMR analyses at the lab bench (LB) in DMSO-d6 (Conditions #2). Wasserman rearrangement, accompanied by alkene isomerization, was first observed when samples were kept in regular glass tubes (RGT), open to the air (OA), and stored at the lab bench (LB) (Conditions #3). In CDCl3, this occurred only with macrocycles 3a,b with t1/2 values of ~35 and~42 d, respectively, but not seco ester 4b. On the other hand, in DMSO-d6, t1/2 was almost the same for macrocycles 3a and 3b (~21 vs ~24 d, respectively). The difference observed with Kashman’s report of a ~3 day half-life for SalaC, may be due to absence of stirring as performed by Kashman,2 which may impact the rate of ambient 1O2 absorption however differences in structure cannot be excluded. Interestingly, initial use of 3 mm NMR tubes also prevented Wasserman rearrangement from occurring after 3 days likely due to reduced solvent surface area for absorption of ambient 1O2. In CD3OD, again no rection was observed with the seco ester 4b however the thiazole macrocycle 3a displayed a significantly increased half-life relative to the oxazole 3b (~3 vs ~1 d, respectively). We speculate that the increased life-time of 1O2 in deuterated methanol37 leads to increased rates of Wasserman rearrangement which occurs faster with the oxazole. Finally, storage in a regular glass tube, open to air, and on a window sill (not in direct sunlight) unsurprisingly led to the fastest rates of rearrangement/isomerization for the macrocycles 3a and 3b in DMSO-d6 (t1/2 ~6 vs ~1 h) and CDCl3 (t1/2 ~13 vs 7 h). However, in the case of seco ester 4b, the t1/2 was ~23 h in CDCl3 and ~8 h in DMSO-d6 supporting the notion that macrocyclic strain increases the rate of rearrangement.

Table 1.

Half-lives of a simplified SalaC thiazole-containing macrocyclic thiazole 3a in comparison to an analogous oxazole variant 3b and seco ester precursor 4ba

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent | t1/2 (days or hours)b | ||||

| Conds. #1 |

Conds. #2 |

Conds. #3 |

Conds. #4 |

||

| RGT, AF, LB |

AT, OA, LB |

RGT, OA, LB |

RGT, OA, WS |

||

| 3a | DMSO-d6 | NRc | NR | ~21 d | ~6 h |

| CDCl3 | NDd | ND | ~35 d | ~13 h | |

| CD3ODe | ND | ND | ~3 d | ND | |

| 3b | DMSO-d6 | NR | NR | ~24 d | ~1 h |

| CDCl3 | ND | ND | ~42 d | ~7 h | |

| CD3ODd | ND | ND | ~1 d | ND | |

| 4b | DMSO-d6 | NR | NR | NR | ~8 h |

| CDCl3 | ND | ND | NR | ~23 h | |

Samples of 3a, 3b, and 4b were stored at 22-24 °C between NMR analyses either in a regular (RGT) or amber NMR tube (AT) and either open to air (OA) or flushed with argon and capped (AF). The location of the NMR tube was either on the lab bench (LB) or the windowsill (WS). RGT = regular glass NMR tube; AF = argon flushed; WS = window sill (time on the windowsill during daylight hours); AT = amber tube; OA = open to air; LB = lab bench ~20 ft. from a window.

Half-lives were determined by comparative integration of two 1H NMR resonances (600 MHz, values provided for d6-DMSO), namely HC4 (δ 7.86) and HC15 (δ 4.37), relative to an internal standard (1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene, δ 6.09). NR = no change after 21 days. ND = not determined.

In CD3OD, other degradation pathways were observed in addition to Wasserman rearrangement and alkene isomerizations.

In conclusion, substitution of the oxazole for a thiazole in simplified SalaC macrocycles 3a,b leads to significantly reduced rate of Wasserman rearrangement with ambient 1O2 in both DMSO-d6 and CDCl3 (roughly 6 times and 2 times greater stability, respectively) when exposed to sunlight. Our results support the notion that replacement of the oxazole with a thiazole will decrease the rate of Wasserman rearrangement of SalaC derivatives in these solvents. Conformational studies (DFT) suggest that introduction of sulfur does not perturb the macrocyclic conformation nor planarity around the thiazole and thus should not dramatically impact bioactivity. Our results, along with those previously reported by Lindel, reveal some of the structural features required for the observed reactivity of SalaC toward 1O2 and support the proposal that the strained macrocycle and extended conformation of the oxazole likely promotes Wasserman rearrangement with ambient 1O2. Studies disclosed herein also suggest ideal ways to store both synthetic samples following macrocyclization and samples for biological assays. A thia-salarin C analog may provide greater aerobic stability facilitating mode of action studies which are currently underway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Support from NIH NIGMS (R35 GM052964) and the Welch Foundation (AA-1280) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Procedures for all synthetic transformations, characterization data for all new compounds including 1H and 13C NMR, IR, and HRMS, and details of stability studies (PDF).

There are no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Bishara A; Rudi A; Aknin M; Neumann D; Ben-Califa N; Kashman Y Salarins A and B and Tulearin A: New Cytotoxic Sponge-Derived Macrolides. Org. Lett 2008, 10, 153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bishara A; Rudi A; Aknin M; Neumann D; Ben-Califa N; Kashman Y Salarin C, a new cytotoxic sponge-derived nitrogenous macrolide. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 4355–4358. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Bishara A; Rudi A; Aknin M; Neumann D; Ben-Califa N; Kashman Y Taumycins A and B, Two Bioactive Lipodepsipeptides from the Madagascar Sponge Fascaplysinopsis sp. Org. Lett 2008, 10, 4307–4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Bishara A; Rudi A; Aknin M; Neumann D; Ben-Califa N; Kashman Y Salarins D–J, seven new nitrogenous macrolides from the madagascar sponge Fascaplysinopsis sp. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 4339–4345. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bishara A; Rudi A; Goldberg I; Aknin M; Kashman Y Tulearins A, B, and C; structures and absolute configurations. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 3820–3822. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Bishara A; Rudi A; Goldberg I; Aknin M; Neumann D; Ben-Califa N; Kashman Y Tausalarin C: A New Bioactive Marine Sponge-Derived Nitrogenous Bismacrolide. Org. Lett 2009, 11, 3538–3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Ben-Califa N; Bishara A; Kashman Y; Neumann D Salarin C, a member of the salarin superfamily of marine compounds, is a potent inducer of apoptosis. Invest. New Drugs 2010, 30, 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Del Poggetto E; Tanturli M; Ben-Califa N; Gozzini A; Tusa I; Cheloni G; Marzi I; Cipolleschi MG; Kashman Y; Neumann D; Rovida E; Dello Sbarba P Salarin C inhibits the maintenance of chronic myeloid leukemia progenitor cells. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 3146–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zur L; Bishara A; Aknin M; Neumann D; Ben-Califa N; Kashman Y Derivatives of Salarin A, Salarin C and Tulearin A—Fascaplysinopsis sp. Metabolites. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 4487–4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Wasserman HH; Vinick FJ; Chang YC Reaction of oxazoles with singlet oxygen. Mechanism of the rearrangement of triamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1972, 94, 7180–7182. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wasserman HH; McCarthy KE; Prowse KS Oxazoles in carboxylate protection and activation. Chem. Rev 1986, 86, 845–856. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ogawa S; Shimazaki R; Soejima A; Takamure E; Hanasaki Y; Fukui S Diurnal changes of singlet oxygen like oxidants concentration in polluted ambient air. Chemosphere 1996, 32, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fekrazad R; Nejat A; Kalhori KAM Chapter 10 - Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy With Nanoparticles Versus Conventional Photosensitizer in Oral Diseases. In Nanostructures for Antimicrobial Therapy, Ficai A, Grumezescu AM Eds.; Elsevier, 2017; pp 237–259. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Schäckermann JN; Lindel T Synthesis and Photooxidation of the Trisubstituted Oxazole Fragment of the Marine Natural Product Salarin C. Org. Lett 2017, 19, 2306–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Schrof R; Altmann K-H Studies toward the Total Synthesis of the Marine Macrolide Salarin C. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 7679–7683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Schrof R Total Synthesis of Dideoxy-salarin C and of a New Pyridomycin Analog. PhD Dissertation, ETH Zürich, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Shea KJ; Kim JS Influence of strain on chemical reactivity. Relative reactivity of torsionally distorted double bonds in MCPBA epoxidations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 3044–3051. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Manfrin A; Borduas-Dedekind N; Lau K; McNeill K Singlet Oxygen Photooxidation of Peptidic Oxazoles and Thiazoles. J. Org. Chem 2019, 84, 2439–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Horner KE; Karadakov PB Shielding in and around Oxazole, Imidazole, and Thiazole: How Does the Second Heteroatom Affect Aromaticity and Bonding? J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 7150–7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Moraski GC; Markley LD; Chang M; Cho S; Franzblau SG; Hwang CH; Boshoff H; Miller MJ Generation and exploration of new classes of antitubercular agents: The optimization of oxazolines, oxazoles, thiazolines, thiazoles to imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines and isomeric 5,6-fused scaffolds. Biorg. Med. Chem 2012, 20, 2214–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Schäckermann J-N; Lindel T Macrocyclic Core of Salarin C: Synthesis and Oxidation. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 6948–6951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).(a) Piers E; Wong T; Coish PD; Rogers C A convenient procedure for the efficient preparation of alkyl (Z)-3-iodo-2-alkenoates. Can. J. Chem 1994, 72, 1816–1819. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bair JS; Palchaudhuri R; Hergenrother PJ, Chemistry and Biology of Deoxynyboquinone, a Potent Inducer of Cancer Cell Death. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 5469–5478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Jesberger M; Davis TP; Barner L Applications of Lawesson's reagent in organic and organometallic syntheses. Synthesis 2003, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Phillips AJ; Uto Y; Wipf P; Reno MJ; Williams DR Synthesis of Functionalized Oxazolines and Oxazoles with DAST and Deoxo-Fluor. Org. Lett 2000, 2, 1165–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Glöckner S; Tran DN; Ingham RJ; Fenner S; Wilson ZE; Battilocchio C; Ley SV The rapid synthesis of oxazolines and their heterogeneous oxidation to oxazoles under flow conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem 2015, 13, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Williams DR; Lowder PD; Gu Y-G; Brooks DA Studies of mild dehydrogenations in heterocyclic systems. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 331–334. [Google Scholar]

- (26).(a) Meyers AI; Tavares F The oxidation of 2-oxazolines to 1,3-oxazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 2481–2484. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tavares F; Meyers AI Further studies on oxazoline and thiazoline oxidations. A reliable route to chiral oxazoles and thiazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 6803–6806. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Meyers AI; Tavares FX Oxidation of Oxazolines and Thiazolines to Oxazoles and Thiazoles. Application of the Kharasch–Sosnovsky Reaction. J. Org. Chem 1996, 61, 8207–8215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Baldwin JE; James DA; Lee V Preparation of 3-alkylpyridines. Formal total synthesis of Haliclamines A and B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 733–736. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Doucet H Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reactions of alkylboronic acid derivatives or alkyltrifluoroborates with aryl, alkenyl or alkyl halides and triflates. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2008, 2008, 2013–2030. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Xie X-G; Wu X-W; Lee H-K; Peng X-S; Wong HNC Total Synthesis of Plakortone B. Chem. Eur. J 2010, 16, 6933–6941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Spino C; Rezaei H; Dupont-Gaudet K; Bélanger F Inter- and Intramolecular [4 + 1]-Cycloadditions Between Electron-Poor Dienes and Electron-Rich Carbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 9926–9927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).(a) Lu X; Huang X; Ma S A convenient stereoselective synthesis of conjugated (2Z)-En-4-ynoic and (2Z,4Z)- and (2Z,4E)-dienoic acid derivatives from propiolic acid derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 2535–2538. [Google Scholar]; (b) Batsanov AS; Knowles JP; Whiting A Mechanistic Studies on the Heck–Mizoroki Cross-Coupling Reaction of a Hindered Vinylboronate Ester as a Key Approach to Developing a Highly Stereoselective Synthesis of a C1–C7 Z,Z,E-Triene Synthon for Viridenomycin. J. Org. Chem 2007, 72, 2525–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).(a) Laganis ED; Chenard BL Metal silanolates: organic soluble equivalents for O−2. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 5831–5834. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA; Starr JT A Cycloaddition Cascade Approach to the Total Synthesis of (−)-FR182877. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 13531–13540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Yu Y-B; Chen H-L; Wang L-Y; Chen X-Z; Fu B A Facile Synthesis of 2,4-Disubstituted Thiazoles Using MnO2. Molecules 2009, 14, 4858–4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Li X; Li S; Yin B; Li C; Liu P; Li J, Shi Z DDQ-Induced Dehydrogenation of Heterocycles for C-C Double Bond Formation: Synthesis of 2-Thiazoles and 2-Oxazoles. Chem. Asian J 2013, 8, 1408–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Dess DB; Martin JC Readily accessible 12-I-5 oxidant for the conversion of primary and secondary alcohols to aldehydes and ketones. J. Org. Chem 1983, 48, 4155–4156. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Bregnhøj M, W M., Jensen F and Ogilby PR. Solvent-dependent singlet oxygen lifetimes: temperature effects implicate tunneling and charge-transfer interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2016, 18, 22946–22961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.