The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends dualenergy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) screening for women 65 years or older and for younger women with an elevated risk for fracture.1 However, for women to benefit from this screening, physicians must initiate drug treatment based on the presence of clinically important DXA abnormalities and patient risk. We estimated the frequency of osteoporosis overtreatment in a regional health care system where DXA reports routinely include T scores for anatomic sites (eg, lateral lumbar spine) that the International Society for Clinical Densitometry2 does not recommend for osteoporosis diagnosis.

Methods |

We performed a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records (EHRs) and linked radiology records on women aged 40 to 85 years receiving initial DXA screening within the UC Davis health system from January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2011; data analysis was conducted from January 1 to July 31, 2015. The institutional review board at UC Davis approved the study. Data were not deidentified. The health system includes an academic medical center and a physician group offering primary care at 13 clinics across the Sacramento region. As previously described,3 EHR and radiology databases were searched back through 2002 (the initial year of system-wide EHR implementation) to identify treatment-naive women undergoing initial DXA screening and to classify women by the presence of 1 or more of 6 risk factors: body mass index greater than 20 (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), glucocorticoid use, possible secondary osteoporosis, previous high-risk fracture (eg, humeral or Colles fractures), rheumatoid arthritis, or alcohol abuse.

We used natural language processing to abstract T scores from EHR radiology reports. For each site, we classified T scores as normal (T > −1.0), osteopenia (−2.5 <T ≤ −1.0), and osteoporosis (T < −2.5). We defined the anterior-posterior spine and femoral neck as main sites because the International Society for Clinical Densitometry2 recommends these for osteoporosis diagnosis. We classified T scores from lateral lumbar, Ward triangle of the hip, forearm, and radius sites as non-main sites. Each DXA result was classified as (1) all sites normal, (2) non-main-site osteopenia (with normal main-site bone mineral density), (3) main-site osteopenia (without osteoporosis), (4) non-main-site osteoporosis (without main-site osteoporosis), and (5) main-site osteoporosis. Using EHR prescription data, we identified patients who received new prescriptions for osteoporosis medications during the year of DXA screening or the following year.

We computed the percentages of women in each DXA category, those who received new prescriptions, and new prescriptions in the population attributable to each category. Analysis using X2 tests was then performed to compare the percentages of women who received new drug therapy by the DXA result (no osteoporosis, non-main-site osteoporosis, and main-site osteoporosis), age, and risk factor status.

Results |

The sample included 6150 women who underwent initial DXA screening; 1912 of these women (31.1% [95% CI, 29.9%-32.3%]) received new osteoporosis drug treatment. A total of 1254 women (20.4%) had 1 or more osteoporosis risk factors. Overall, 871 women (14.2%) had main-site osteoporosis, 2016 women (32.8%) had non-main-site osteoporosis, and the remaining 3263 women (53.1%) had either isolated osteopenia or normal T scores (Table).

Table.

Unadjusted Percentage of Women Receiving New Osteoporosis Drug Therapy

| No. (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry Resulta |

||||||||

| Total |

No Osteoporosis |

Non-Main-Site Osteoporosis |

Main-Site Osteoporosis |

|||||

| Age | No. | New Treatmentb | No. | New Treatmentb | No. | New Treatmentb | No. | New Treatmentb |

| 40-64 y | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Low-risk | 3696 (60.1) | 913 (24.7) | 2246 (60.8) | 179 (8.0) | 1092 (29.6) | 469 (43.0) | 358 (9.7) | 265 (74.0) |

|

| ||||||||

| Elevated risk | 927 (15.1) | 289 (31.2) | 512 (55.2) | 52 (10.1) | 289 (31.2) | 147 (50.9) | 126 (13.6) | 90 (71.4) |

|

| ||||||||

| ≥65 y | 1527 (24.8) | 710 (46.5) | 505 (33.0) | 80 (15.8) | 635 (41.6) | 345 (54.3) | 387 (25.3) | 285 (73.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| Total | 6150 (100) | 1912 (31.1) | 3263 (53.1) | 311 (9.5) | 2016 (32.8) | 961 (47.7) | 871 (14.2) | 640 (73.5) |

No osteoporosis indicates all sites normal or osteopenia without osteoporosis; non-main-site osteoporosis indicates lateral lumbar or other site osteoporosis.

P < .001 for χ2 test assessing overall difference in percentages of women who received new treatment with drugs by age-risk category.

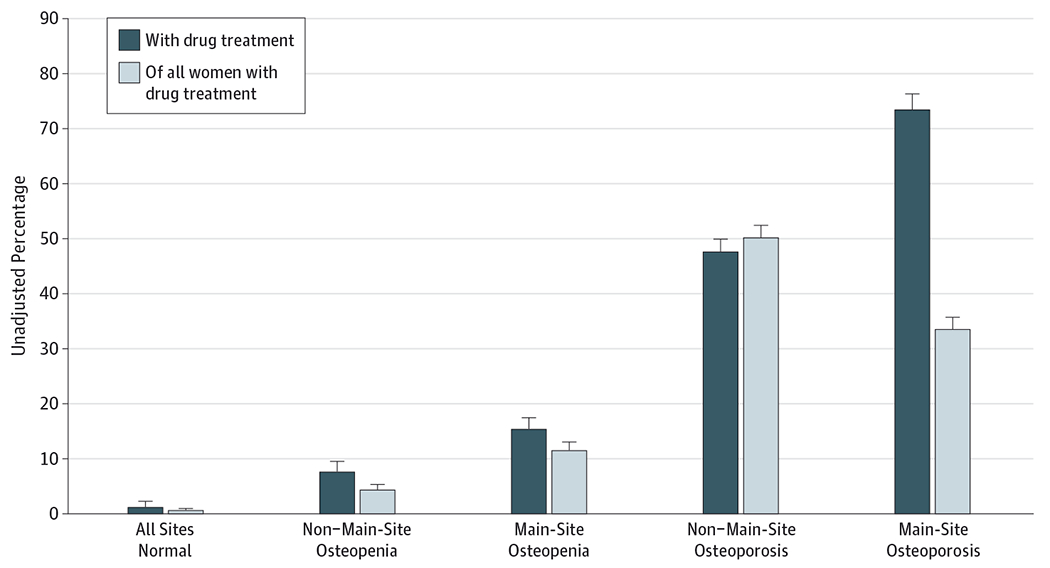

Most women with main-site osteoporosis (73.5% [95% CI, 70.4%-76.4%]) received new drug therapy, as did nearly half of those with non-main-site osteoporosis (47.7% [95% CI, 45.5%-49.9%]) (Figure). Nevertheless, because non-main-site osteoporosis or isolated osteopenia occurred commonly, women with non-main-site osteoporosis accounted for 50.3% of new drug prescriptions (95% CI, 48.0%-52.5%), and those with osteopenia accounted for 15.8% (95% CI, 14.2%-17.5%).

Figure. Unadjusted Percentage of Women Receiving New Drug Prescriptoins and Percentage of All Women Treated by Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry Screening.

Main sites include the anterior-posterior spine and femoral neck; non–main sites include the lateral lumbar spine,Ward triangle of the hip, and the radius. Error bars indicate 95% CI.

Of the 6150 initial DXAs, 3696 (60.1%) were performed on women aged 40 to 64 years without osteoporosis risk factors who may not have been recommended for screening according to the US Preventive Services Task Force (Table). Of the 1912 women who initiated new drug treatment, 1272 (66.4%) had DXAs either without osteoporosis or non-main-site osteoporosis. Of those 1272 women, 648 (50.9%) were aged 40 to 64 years and had no risk factors. Results were essentially unchanged when analyses were repeated, first, excluding women younger than 50 years or those with previous high-risk fractures, and second, only with DXAs completed from January 1, 2009, through December 31, 2011.

Discussion |

Within a regional health care system, two-thirds of new osteoporosis drug prescriptions were potentially inappropriate because the osteoporosis diagnosis was based on DXA abnormalities considered nondiagnostic by international guidelines. Of these potentially inappropriate prescriptions, half were provided to younger women without osteoporosis risk factors who may not have merited screening.

In our population, nearly one-third of the women had non-main-site osteoporosis, which was disproportionately attributable to lateral lumbar spine osteoporosis. These results suggest that either physicians are unaware of International Society for Clinical Densitometry guidelines2 that lateral lumbar spine bone mineral density should not be used for osteoporosis diagnosis or they assume that osteoporosis observed at any site warrants treatment.

Although two-thirds of new prescriptions in the population were potentially inappropriate, some higher-risk patients with non-main-site osteoporosis or osteopenia may elect to begin drug treatment.4 We also acknowledge the limitation of potential inaccuracy of EHR-derived variables. However, these issues are unlikely to account for the observed extent of overtreatment.

Our findings are from one regional health care system and may not generalize to others that do not report T scores at non-diagnostic sites. Our system recently ceased reporting lateral lumbar spine and the Ward triangle T scores determined on DXA screenings. To avert osteoporosis overtreatment, health care systems should either ensure that radiologists report T scores only for sites consistent with International Society for Clinical Densitometry diagnostic guidelines or provide high-quality decision support so that physicians do not make osteoporosis diagnoses based on nondiagnostic sites.

Funding/Support:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant UL1TR000002 from the Clinical and Translational Science Center (CTSC) at UC Davis (Dr Fenton), and grant T32HS022236 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Dr Amarnath).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

References

- 1.Nelson HD, Haney EM, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Chou R Screening for osteoporosis: an update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(2):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schousboe JT, Shepherd JA, Bilezikian JP, Baim S Executive summary of the 2013 International Society for Clinical Densitometry Position Development Conference on bone densitometry. J Clin Densitom. 2013;16(4):455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amarnath AL, Franks P, Robbins JA, Xing G, Fenton JJ. Underuse and overuse of osteoporosis screening in a regional health system: a retrospective cohort study [published online May 19, 2015]. J Gen Intern Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]